Historic New England Summer 2006

-

Upload

historic-new-england -

Category

Documents

-

view

223 -

download

3

description

Transcript of Historic New England Summer 2006

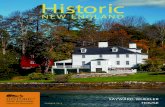

HistoricNEW ENGLAND

AT HOME WITHTHE BOWENS

PRESENTED BY

THE SOCIETY FOR

THE PRESERVATION OF

NEW ENGLAND ANTIQUITIES

SUMMER 2006

PRESENTED BY

THE SOCIETY FOR

THE PRESERVATION OF

NEW ENGLAND ANTIQUITIES

SUMMER 2006

AT HOME WITHTHE BOWENS

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:47 PM Page FC

F R O M T H E P R E S I D E N T

We are fulfilling our vision of being a morepublic organization by engaging more peoplewith the extraordinary historic resources inour care. From education programs servingthousands of school children, to our stronginternet presence, to our partnership withother organizations, Historic New England isnow more accessible to the public.

At the core of our efforts are our mem-bers. During June we celebrate Members’Month as staff experts welcome you to prop-erties not often open and lead behind-the-scenes tours of the collections and facilitiesyour membership helps support. Members’Month launches a new initiative to dramat-ically increase our membership levels. Withthe aid of a Community Action Partners teamof Harvard Business School alumni, we aresending the message that membership notonly brings individual benefits but alsomakes a lasting contribution to the preser-vation of New England heritage.

We’re proud to preserve and present ourthirty-five historic sites and our vast collec-tions. We believe that this outstanding workmerits support by those who care about pre-serving the region’s historic past. Membershipis the best way to express that support.During Members’ Monthand the year ahead, pleasehelp us bring new membersto the organization by giv-ing gift memberships orsimply suggesting to othersthat they join. Thank you.

PARTNERSHIP 1Animals at the Farm

PRESERVATION 8Repairing Loose and Broken Window Glass

MAKING FUN OF HISTORY 10Photography Through the Centuries

MUSEUM SHOP 13Members’ Special

COLLECTIONS 14Little Women

SPOTLIGHT 20The Glorious Fourth

LANDSCAPE 22Sarah Orne Jewett and the White Rose

NEWS: NEW ENGLAND & BEYOND 24

ACQUISITIONS 26Boston from Dorchester Heights

Except where noted, all historic photographs and ephemera are from Historic New England’s Library and Archives.

At Home with the Bowens 2

William Morris in New England 16

V I S I T U S O N L I N E AT w w w. H i s t o r i c N e w E n g l a n d . o r g

HistoricNEW ENGLAND

Summer 2006Vol. 7, No.1

—Carl R. Nold

Historic New England141 Cambridge StreetBoston MA 02114-2702(617) 227-3956

HISTORIC NEW ENGLAND magazine is a benefit of membership.To join Historic New England, please visit our website, HistoricNewEngland.org or call (617) 227-3957, ext.273. Comments? Please callNancy Curtis, editor at (617) 227-3957, ext.235. Historic NewEngland is funded in part by the Institute of Museum and LibraryServices and the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

Executive Editor Editor DesignDiane Viera Nancy Curtis DeFrancis Carbone

COVER Dining room, Roseland Cottage,Woodstock, Connecticut.Photograph by Aaron Usher.

Dav

id C

arm

ack

Aar

on

Ush

er

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:48 PM Page IFC

1Summer 2006 Historic New England

P A R T N E R S H I P

or nearly three centuries, animals were a vital part of the landscape atSpencer-Peirce-Little Farm in Newbury, Massachusetts. The Little familyran a thriving business importing and selling Iowa draft horses in thenineteenth century, and there were sheep, cows, and poultry, not to men-

tion family pets, as well. Until recently, Historic New England imported farm ani-mals for the day during special events like the Draft Horse Plow Match and theHarvest Festival. Now the organization partners with the Massachusetts Societyfor the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (MSPCA), ensuring the presence of ani-mals at the farm year round.

The partnership developed out of mutual needs—the MSPCA’s Nevins Farmshelter in Methuen, Massachusetts, had more animals than it could house, whileHistoric New England wanted animals not only for its special events but also fornew family-friendly programs in development at the farm. Last spring, HistoricNew England built historically accurate fencing and timber-frame shelters at thefarm, and at the end of April, just in time for the Draft Horse Plow Match, the firstfoster animals arrived: two Nubian goats named Sun and Shine and Tonya, thegame hen. The goats were soon joined by two lambs, two ducks, two additionalhens, a pair of elderly sheep, and Molly Brown, a retired thoroughbred horse.

The response from the community is overwhelming. Dozens of people come everyday to say hello to their favorite farm friend. Twice each week, a group of toddlersattends a morning program focused on one of the animals. Caroline the sheep makesgood will visits to neighbors, and several animals visit local schools.

The MSPCA is a wonderful partner in this endeavor, providing help with plan-ning, transportation, and animal husbandry education. In exchange, Historic NewEngland offers flexible, adaptable space and a loving and secure home for the ani-mals saved by the MSPCA’s good work, while relieving the strain on Nevins Farm’sresources. The presence of animals at Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm enriches the expe-rience for every visitor and keeps the farm’s historic tradition alive.

—Bethany GroffRegional Site Manager

F

ABOVE RIGHT Admiring farm animals

is a favorite activity for family

visitors. ABOVE TOP Two sheep, Erma

and Earl, arrive at the farm. ABOVE

Two of the Little sisters with one

of the family’s cows, c. 1900.

Pho

togr

aphs

by

Dav

id C

arm

ack

Visit the farmthis season,

Thursdays throughSundays, from 11 am to

5 pm, through October 15.

Animalsat the Farm

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:48 PM Page 1

At Home with

the Bowens

Aar

on

Ush

er

At Home with

the Bowens

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:48 PM Page 2

3Summer 2006 Historic New England

at Historic New England’s Roseland Cottage, “After break-fast, sisters & myself read French for an hour & then in theafternoon, read History or something of that nature…. Theremainder of the day is spent in riding, eating, sleeping,sewing & thinking.” The quiet country life attracted Lucyand her husband, Henry Chandler Bowen, a successful mer-chant, publisher, insurance company founder, and entrepre-neur, because of its sharp contrast with the bustling New YorkCity world where the family lived for the rest of the year.

In 1846, the Bowens had built a Gothic Revival country“cottage” in the peaceful village of Woodstock, Connecticut,Henry’s hometown. For three generations, the town, andRoseland, would become the symbolic center of Bowen fam-ily life, a place where children and adults alike could relax in

“We are all settled

for the summerand how rapidly it will pass….”

the healthy country air and devote themselves to self-improvement and outdoor activities.

Henry Chandler Bowen, a self-made man, used the pow-ers of the purse and press to achieve importance for himselfand his family. The son of a storekeeper, he left Woodstockat the age of twenty to work as a clerk in the New York Citydry goods store of Arthur and Lewis Tappan, successful silkmerchants from New England known for their strong workethic, sharp business acuity, religious fervor, and anti-slaverysentiments. In 1838, Henry, along with another formerTappan clerk, left to set up his own dry goods emporium spe-cializing in silks. Bowen was a shrewd businessman; as onelater commentator remarked, “driving a bargain narrowly

Aar

on

Ush

er

FACING PAGE The Bowens’ newly refurbished bedchamber displays

the original Gothic Revival furniture, including a mahogany crib

recently donated by Henry E. Bowen’s descendants. ABOVE LEFT

Roseland Cottage,designed by Joseph C.Wells,was built in 1846 for

the rapidly expanding Bowen family. ABOVE RIGHT Lucy and Henry

Bowen with their first child, Henry E. Bowen, 1845.

Aar

on

Ush

er

riting to a friend one June

day, Lucy Bowen recounted

her routine for the summerW

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:48 PM Page 3

Co

urte

sy o

f M

useu

m o

f th

e C

ity

of

New

Yo

rk

Historic New England Summer 20064

and sticking to it afterwards. No matter what a ventureseems to promise in other hands, it is almost always a mineof wealth when Henry Bowen works it.” By the 1850s, hiselegant marble store on Broadway did more business thanany other silk wholesaler.

In 1844, Henry, aged thirty, married Lewis Tappan’snineteen-year-old daughter, Lucy Maria Tappan; theyhad both taught Sunday school at their Brooklynchurch. Two years later, the couple builtRoseland Cottage. During Lucy’s lifetime,Roseland was a quiet retreat for Lucy,Henry, their children, and close familyfriends and relations. Universally revered asa “naturally amiable and affectionate” woman,Lucy devoted her life to domestic concerns, herfamily, her church, and especially her children. Between1845 and 1863, she gave birth to seven sons and threedaughters, and spent most of her time, as her father recalled,“making all around her happy by her genial disposition.”

In the 1850s, the profits from Bowen’s store fluctuatedwildly along with the economy of a country fractured by sec-tionalism. Henry was opposed to the extension of slaveryand the Fugitive Slave Law, but he saw himself as a “con-

science Whig” rather than an abolitionist. Ever the business-man, Bowen had strong trade relations with southerners andhoped to keep his business and his politics separate, but thestore eventually closed when southern customers repudiatedtheir debts to northern merchants on the eve of the Civil War. Fortunately, Henry had initiated another highly lucrative endeavor in 1853, when he gathered a group

of investors to establish the Continental InsuranceCompany, which would provide a steady source of

income for generations of Bowens.In 1848, Henry founded and became the

publisher of a weekly newspaper, the Inde-pendent, designed to spread New England

Congregationalist values. He hired a series ofdistinguished editors, and the paper published

the writings of many of the leading literary figuresof the day along with sermons and other religious tracts.

The Independent avoided partisan politics until 1856, whenBowen became an early supporter of the Republican party.After Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, Bowen, and hisnewspaper, became important players in regional and evennational politics. In 1862, he was rewarded with a profitablepatronage position—Tax Collector for the Third District of

ABOVE LEFT The front parlor, as well as the dining room (cover) and

hall (page 7), reflect both Roseland’s original Gothic Revival style in

architectural details and furniture and Henry and Ellen Bowens’

taste for elaborate 1880s-style decoration. ABOVE RIGHT Joseph C.

Wells also designed Bowen’s “marble store,” built on Broadway in

New York City in 1850. BELOW Bowen used this box after Abraham

Lincoln appointed him Tax Collector for his Brooklyn district.A

aro

n U

sher

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:48 PM Page 4

yy

5Summer 2006 Historic New England

the State of New York. Bowen worked hard for Republicancandidates throughout his life, and he, and the Independent,gained influence in the party in return for his loyalty.

In 1863, Lucy died at the age of thirty-eight, leavingHenry Bowen with ten children between the ages of onemonth and eighteen. Soon after her death,the bereaved and undoubtedly belea-guered widower sent four of his olderchildren away to school, and twoyears later, he married his secondcousin, Ellen Holt. They would haveone son together.

Henry and Ellen’s marriagewas a turning point for the familyand for Roseland, which became asite of entertainment and displayrather than a quiet country retreat. Ellen, the thirty-one-year-old daughter of aConnecticut doctor, embraced the political and social ambi-tions of her well-established, middle-aged husband. For thenext thirty years she would be an eager hostess, consumer, andpartner in his schemes for promoting Woodstock, his family,and himself.

After the Civil War, Henry determined to make Wood-stock a showplace for New England values as well as anadvertisement for his newspaper and its politics, and he andEllen began to host hundreds of visitors at their “cottage.”Reviving an early nineteenth-century tradition of Indepen-

dence Day celebrations, he made Wood-stock the site of an ever-escalating series

of yearly patriotic commemorationsattended by thousands. Three presi-dents, Ulysses S. Grant, BenjaminHarrison, and Rutherford B.Hayes, and a long list of senators,congressmen, governors, and otherpolitical, literary, and social lumi-

naries trekked to Woodstock to par-ticipate in these July Fourth events.

Like other self-made nineteenth-century men, Bowen pursued wealth and

fame repeatedly, even when exposure to the public eye mighthurt his reputation. A complex man whose moralistic self-image contrasted with his pugnacious style, Bowen was partyto a number of lawsuits and a central figure in the infamousBeecher-Tilton scandal of the 1870s. In 1870 Theodore

ABOVE LEFT Three of Lucy and Henry Bowens’ younger sons, John,

Herbert, and Franklin, photographed after Henry married Ellen

Holt in 1865. ABOVE RIGHT Grace Bowen named her doll Lena

Rivers after the heroine of a popular 1856 novel. Like Grace,

Aar

on

Ush

er

Lena had a large and fashionable wardrobe; they are depicted

in matching outfits on page 14. BELOW Henry and Ellen Bowen,

photographed during the heyday of Woodstock’s July Fourth cele-

brations (see illustrations on page 21).

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:48 PM Page 5

Historic New England Summer 20066

Tilton, an editor at the Independent, had accused fellow edi-tor Henry Ward Beecher, who was both Bowen’s minister anda national celebrity, of seducing his wife. During a widelypublicized trial, it became clear that Bowen, despite his beliefin Beecher’s guilt, had brokered a cover-up to protect hisfinancial interests. With the tumult of the Brooklyn scandal,Roseland Cottage became even more important to Bowen asa representation of his personal success and the values—edu-cation, hard work, thrift, clean living, and moral principles—he saw as key to the prosperity and fortunes of the nation.

Henry Bowen had a deep impact on his children. Whilethey idolized the “mamma” who had lavished affection onthem and died so young, they also internalized their father’s

need for acceptance and recogni-tion. Henry was a proud,generous, and loyal father,and he, like Lucy, encour-aged his children to study,become proficient at writ-ing of all kinds (familyoccasions were marked byoriginal poems and oratory),

play musical instruments, and engage in healthy physicalactivities. But Henry could also be stern and moralistic, andthe children found his prohibitions against drinking, smoking,card-playing, and theatre attendance old-fashioned and inap-propriate for young people of their class.

Like their father, the two older boys began as clerks, buttheir training prepared them to become brokers in the high-powered world of investing and banking. The five youngerbrothers followed a different path, attending elite colleges; all but one went to Yale. By 1869, when Clarence matricu-lated, a college education had come to represent class statusas much as learning. College men learned appropriate classbehaviors, made the contacts that would serve them through-out life, and achieved masculinity through competitive activ-ities in and out of the classroom, including debate and sports.

Henry may have been reluctant to send his sons to Yale,and he insisted that Clarence sign a pledge to “refrain” frombehaviors he disliked. In fact, he may have allowed Clarenceto go only because he had expressed interest in the ministry,a profession that required a college degree. Clarence brokehis pledge to his father, guiltily noting in his journal in 1872that “We had a little ‘Rum’…last evening;…We have theseinnocent ‘recreations’ once in two or three weeks but they arevery quiet and orderly.” But he also taught Sunday schooland otherwise behaved himself, and in the end his brothers,none of whom had religious aspirations, followed him toYale. Most of the Bowen sons were ambitious; they engagedin various literary, journalistic, historical, and diplomaticendeavors that reflected the family criteria of self-improve-ment, self-advancement, and public service.

The Bowen sons expended much of their considerableenergy on sports, especially in Woodstock. All the Bowenchildren grew up bowling in Henry’s ten-pin alley as well asriding, playing croquet, and swimming, but as they matured,the sons increasingly exhibited their masculinity, sophisti-cation, and class status through sports like polo, hunting,and, eventually, golf. One Saturday in 1879, for example,Clarence and his brother Frank went fishing in Woodstock at5 am; afterwards “from 9 to 11 we played archery. Then anumber of us went down to the Park…took a boat and withour guns and a lunch started down the lake…I shot with mynew gun for practice several red winged black birds on thefly… Frank shot a huge heron. From 3 to 4 p.m. I attendedthe Prefaratory Lecture at the Church and from 4 to sixplayed a most exciting game of Polo on the Common. ThenI took tea at Ned’s home and in the evening saw fireworks atRoseland Cottage and also looked through a new telescopeat the stars. I tell you, I slept soundly that night.”

While the Bowen daughters engaged in lady-like sportslike swimming, boating, bowling, badminton and croquet,they, like other genteel nineteenth-century women, spent mostof their time reading, sewing, and helping to run the house-hold. Like their mother, Mary and Alice married young;devoted to their families, they chose to bask in the reflectedglory of their husbands’ and children’s many accomplish-ments. Grace, who remained single until she was forty-eight,helped her sisters with their children and her stepmother withhousehold duties and social responsibilities, planning dinnerparties and other entertainments, paying social calls, and cre-ating beautiful fancy work for family Christmas gifts.

In 1874, Mary noted that “George [her husband] and I are busy with the literature of the Elizabethan age. Our lifeis a very happy one. We live quietly and simply. Have ourfriends here to see us, see all the good plays there are to be seen and try to find what pleasure there is to be found.”Written during the trying period of the Beecher-Tilton scan-dal, when the family was embarrassed by all the negativepublicity involving Henry, this remark poignantly reveals the deep impact of the scandal on the second generation of Bowens. The older Bowen children traveled frequently to Europe in the 1870s, perhaps in part to remove themselvesfrom the American public eye. Like many wealthy Americansin this period, they became inveterate travelers. They fre-quented the theater and the opera in New York and Europe,and they continued to drink and smoke, despite their father’sdisapproval. In what may have been a wry commentary ontheir upbringing, Grace sent her brother Harry a check for“cigars—or whiskey” for his seventieth birthday.

Henry Bowen died in 1896, but his presence and influencecontinued to be felt in the family, and Woodstock, for manyyears. By the early twentieth century several second and thirdgeneration Bowens had purchased summer and retirement

Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:48 PM Page 6

7Summer 2006 Historic New England

ABOVE LEFT The Bowen’s sons, like other late nineteenth-century

men of their class, spent much of their leisure time engaged in

sporting activities like hunting,polo,and, later,golf.Hunters enjoyed

presenting their catch to appreciative young ladies, who would

cook the food and save bird wings, feathers, and animal fur for their

decorative value. ABOVE RIGHT The rich colors of the recently refur-

bished Lincrusta-Walton wallcovering and the reproduction carpet

bring new life to the entrance hall.

Aar

on

Ush

er

homes in the town. Mary, Ned, and Frank had inheritedRoseland, and, in the evenings, the family converged on the“cottage” for cousin parties and other entertainments wherestories were told and family bonds reforged. In 1940, Mary’schildren, Constance and Sylvia, became the family hostesses,carefully preserving the house, its contents, and the tales thatthey had heard and repeated.

Many of these legends continue to be passed on toRoseland Cottage visitors today. Henry Chandler Bowen wasa significant, fascinating, and fully human man of his time—a self-made businessman, activist, political organizer, and promoter of quintessentially American nineteenth-centurycultural values, including loyalty to family and country.Roseland Cottage stands as a symbol of the principles heespoused—community, morality, self-sufficiency, thrift—aswell as those he represented—upward mobility, individualism,ambition, and consumption—and tells a key American storyof success.

—Susan L. PorterHistorian

Roseland Cottage, one of only a handful of surviving GothicRevival cottages in New England, is an outstanding exampleof the style, preserved with original furnishings, parterre gar-den, and full complement of outbuildings, along with thearchitect’s drawings, historic photographs, and ledgersrecording purchases from trees to pigs to croquet sets. As aresult of recent refurbishing, based on extensive scholarlyresearch, the summer house now sparkles like a jewel inHistoric New England’s crown.

Historic New England considers Roseland Cottage to beone of its most important properties and remains committedto an ongoing process of conservation and capital improve-ments. Future projects include conserving the Lincrusta-Walton wallcovering and reproducing the Wilton carpet andborder in the double parlor. Because the property has noendowment, having been purchased with assistance from theConnecticut Historical Commission in 1970, RoselandCottage remains a priority for fundraising efforts.

We urge you to visit the cottage this season during its newextended hours, Wednesday through Sunday, 11 am – 4 pm,through October 15. Come see the exciting renewal processfor yourself and support the preservation effort with a contribution.

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:48 PM Page 7

Historic New England Summer 20068

indows are one ofthe most architec-turally importantvisual aspects of a

building, be it a private residence, store-front, apartment building, or factory.The very character of a structure isreflected not only in the windows’design but in their materials; conse-quently it is important whenever possi-ble to repair rather than replace sashthat suffer from failed putty, or glazing,loose panes, and cracked or brokenglass. Repairing damaged sash is not acomplicated process as long as youhave the proper tools, a love of adven-ture, and plenty of time. If you have theconfidence and skill to remove the sashfrom the window opening, you canlikely manage these glass repairs your-self.

Begin by breaking the paint bondbetween the window trim and the inte-rior window stop with a sharp utilityknife. Gently pry off the stop with a

stiff putty knife or thin, wide pryingtool and lift the lower sash out of theopening, removing any sash cords fromthe frame and tying knots in the endsso they don’t fall into the weight pock-ets. Upper sash, held in place by eitherparting beads or window stops, may bepried off in the same manner.

Place the sash on a level work sur-face, out of doors or in an area withgood ventilation. Number the paneswith a marking pen so that they can bereplaced in their original openings.Your first step will be to remove theglazing holding in the glass. If you’relucky and the glazing is already loose,draw a utility knife along the muntinsto remove the remaining glazing andthe glazing points. If the glazing ishard, you’ll have to resort to a moreextreme measure—a heat gun. Heatguns can be dangerous—they pose thedanger of fire and are also associatedwith health risks from fumes in lead-based paint. If your home was built

P R E S E R V A T I O N

1

Wbefore 1975, you most likely have leadpaint to contend with, which is whygood ventilation in your work area isessential.

RepairingLoose and Broken Window Glass

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:48 PM Page 8

9Summer 2006 Historic New England

2 3

1. When using a heat gun to softenhardened glazing, take care to protectthe adjacent glass from the heat to keepit from breaking. A bent piece of tinwith a straight edge that fits tightagainst the glazing will shield the glassfrom the heat. Once the glazing hassoftened, use a utility knife to loosenthe glazing from the muntin and aputty knife or chisel to remove theglazing from the glass. Carefully pryout the glazing points.

2. When you are sure that all thepoints have been removed, place onehand beneath the glass and gently pushit up and away from the sash. If anyglazing still clings to the glass, soak thepane overnight in linseed oil to makeremoval easier.

3. Manually remove any glazingremaining in the rabbet (the area wherethe glass sits) and sand it down to barewood. Now is the time to remove any

4

5

failing paint, sand rough or weatheredsurfaces, and prime all exposed sur-faces, including the rabbet, with an oil-based exterior primer. Let dry.

4. Before reinstalling the glass, lay abead of softened glazing, called bedglazing, around the rabbet to cushionand seal the glass. Kneading the glazingprior to use and keeping some in yourhand will help keep it pliable and easyto use.

5. Next, gently press the pane ofglass into the bed glazing. Press evenlyall the way around to seal the pane tothe glazing.

6. With a putty knife, install glazingpoints into the wood around the pane,taking care to push sideways and notdown on the glass.

7. The final step in the glazingprocess is to apply a beveled bead of

6 7

glazing. Use a glazing knife to push theglazing against the muntin and the glass.Pull the knife while at the same time feed-ing a rope of glazing as you go. It will takesome practice, but in no time you’ll get thehang of it. The sash can be finish paintedafter the glazing has “skinned” over, usu-ally in two or three days. Ensure a goodseal by lapping the edge of the paint slight-ly over onto the glass. Once the paint hasdried adequately, the sash are ready toreinstall, and you can then sit back onthose cold winter nights knowing thatmost of your heat is staying indoors whereit belongs.

—Bruce BlanchardCarpentry Foreman

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:49 PM Page 9

M A K I N G F U N O F H I S T O R Y

1727Johann Schulze accidentally createsfirst photo-sensitivecompound

1826Nicéphore Niépcemakes the first successful perma-nent photograph

1834William Talbotintroduces thepaper photo-graphic process

1837Louis Daguerre captures images on silver-platedcopper

1860sCartes de visites,stereo views, and tintypes are popular

1889First camerato use a rollof film isinvented

They are flashcubes. Before cameras had built-in electronic flashes,photographers had to add flash by hand when they wanted to shootindoors or at night. Originally, they used a single bulb that had to

be replaced after each shot. The flashcube changed that. Containingfour individual bulbs, each with its own reflector, the flashcube quicklysnapped onto the top of a camera. After taking a picture, the photog-rapher had only to turn the cube to be ready for another snapshot.Unfortunately, after the flashcube was used four times it, too, had to bethrown away.

Can you guess what these are?

�The flashcube helped home photographers take the great shots

do youknow

that used to get away while they were busy changing bulbs.

Did you know that photography

has been around formore than 150 years?

Historic New England Summer 200610

Photography through the centuries

Let's look at how it has changed sincethe 1800s and see what photographscan tell us about the lives of people wholived a long time ago.

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:49 PM Page 10

11Summer 2006 Historic New England

Unscramble each of the clue words. Copy the letters inthe numbered boxes to the boxes with the same number below to find the secret phrase.

Jumble puzzle

picture this

1900Kodak’s Browniecamera ushers inthe snapshot

1947Edwin Land of Polaroiddemonstrates his instantimage camera

1963Kodak introducesthe easy-to-loadInstamatic camera

1994First digital camera for home computersis marketed

!Challenge

2001Digital camerasoutsell filmcameras

CMEARA

GINTEAVE

CAFBUELHS

TARPOYHOHGP

PASTOSHN

What is happen-ing in this photo?If you can’t tell,try cutting it upand rearrangingthe pieces.

Although most photographs today are printed on paper, in the1850s, photographic images were most often made on copper,tin, or glass.These early pictures were unique—they were not printedfrom a negative, but instead the image was formed on the surfaceof the metal or glass plate. People posing for these early pho-tographs had to hold still for a long time. Sometimes the photog-raphers used special supports to keep people from moving whiletheir picture was being taken.

Answers can befound on page 13.

A picture is worth a thousand words.A dramatic photograph can immediately trans-port us to an entirely different time and place.Visit www.HistoricNewEngland.org/kids/PhotoExhibit for an online exhibition of his-toric photographs, which was created by kidsespecially for kids.

7 2

6

8 5 4 9

3

1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:49 PM Page 11

12

M A K I N G F U N O F H I S T O R Y

When the inventors of photography first came up with a light

sensitive compound that could permanently capture an image,

they combined it with an optical device that had been known to

scientists and artists for centuries—the camera obscura (which

means “dark room” in Latin). As small as a box or as large as

a room, the camera obscura is a darkened space

with a pinhole in one of its walls. When the

pinhole is placed facing a brightly lit scene, a

reversed image of the scene will be reflected on

the camera obscura’s opposite wall.

Using simple household materials, you can make your owncamera obscura. A translucent back “wall” of the camera will allowyou to see the image reflected inside.

Assembly Instructions:1. Roll the construction paper into a cone and tape it together.Trim the wide end so that it is just big enough to fit snugly insidethe opening of the cup. Make sure that the narrow end of thecone is large enough to look through comfortably with one eye.

2. Cut a piece of wax or tissue paper that is slightly largerthan the wide opening of the paper cone. Pull the wax or tissue paper taut over the opening of the cone and tape it all the way round.

3. Line the inside of the cup with black construction paperso that no light can shine through.

4. Carefully insert the wide end of the cone into the cup.With duct tape or black electrical tape, completely seal thejoint where the cone and cup meet. Check to make sure thatno light can get inside your camera obscura.

5. Use a thumb tack to make a small hole in the center of thebottom of the cup.

Materials:• heavy black construction paper• a sturdy paper cup• wax paper or white tissue paper• duct tape or black electrical tape• scissors • thumb tack

Historic New England Summer 2006

CameraObscura

Operating Instructions:1. Take your camera obscura outside on a sunny day. Pointit at something you would like to see reflected inside. Holdthe end of the cone up to your eye, and use your hand to sealout any light. Close the other eye.

2. Allow a moment for your eye to adjust. You should see animage of the scene in front of you, reflected upside down onthe translucent wax or tissue paper inside your camera obscura.

Troubleshooting Tips:• Pick a distinctive object to focus on, such as an unusuallyshaped tree or brightly colored building. Remember—the imagewill be upside down.• Make sure that the pinhole is the right size. A very smallhole will not let in enough light, while too large a hole willblur the image.• The camera obscura works best in bright sunshine.

—Amy PetersSchool and Youth Program Coordinator

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:49 PM Page 12

13Summer 2006 Historic New England

M U S E U M S H O P

Members’Special

t’s a great time at Historic NewEngland. We hope you’re takingadvantage of your improved mem-ber benefits, including an expanded

slate of June Members’ Month activi-ties, advance member registration toour most popular programs, additionalmembers-only lectures, improved dis-counts on program fees, and our firstmembers’ weekend trip to BoothbayHarbor, Maine, in August.

But there’s more! We’re delightedto make this special summer offer.Now through August 31, you may pur-chase Windows on the Past: FourCenturies of New England Homes atthe special member price of $25, a44% discount, while supplies last. This

beautiful book, featuring hundreds ofcolor photographs, historic images,and lively text by Jane C. Nylander andDiane Viera, surveys four centuries ofdaily life in the region through theengaging stories of the people wholived at Historic New England’s housemuseums.

Use the book as a guide to plan-ning your summer excursions and also as a reference to New England’srich social and architectural history.Windows on the Past belongs in thelibrary of everyone who cares aboutthe region’s cultural history. Considerpurchasing a copy for a friend or familymember as well. Combined with a gift

membership, it makes a unique wed-ding or birthday gift.

Celebrate your Historic NewEngland with others who share thepassion for preserving New England’srich cultural heritage.

ITo order, please call (617) 227-3957, ext.237, or order from the Museum Bookstoreat www.HistoricNewEngland.org. Tax andshipping charges apply.

Answers to questions on page 11.CAMERA, NEGATIVE, FLASHCUBE,PHOTOGRAPHY, SNAPSHOTSecret phrase—SAY CHEESE

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:49 PM Page 13

Historic New England Summer 200614

n about 1862 Grace Bowen and herdoll, both dressed in the height offashion, traveled to the studio of aBrooklyn, New York, photographer

to have their portraits made (see relatedstory on page 5). Grace’s experienceand the resulting carte de visite portraitwere not at all out of the ordinary.From the beginning of the medium,photographers recognized the lucra-tiveness of children’s portraiture andactively marketed their services to parents. Boston daguerreotypist S. H.Lloyd made special mention of chil-dren on a trade card from about 1860,“Particular attention given to thesecuring of likenesses of children, whoare taken in a very few seconds….”The parents reacted positively to thepermanent capture of their offspring’schildhood innocence and at the sametime to the conveyance of a sense oftheir own well-being and comfort.Children often were depicted withtheir toys, which for the most partwere gender-specific—boys with hoopsand girls with dolls.

Historic New England holds manysuch examples of children’s portraits.The images on these pages span almost

I

C O L L E C T I O N S

one hundred years—froma mid-nineteenth-centurydaguerreotype to a printfrom the 1940s. The dolls,too, provide a variety,from lady dolls to babyand child dolls. Whetherthe dolls in these imageswere beloved companionsor just showpieces to betaken out on special occa-sions, we cannot know. We do knowthat two of the dolls were cared forlovingly and later donated to HistoricNew England either by the originalowners or by descendants. All but oneof the images were made in studios.We could not resist including the onesnapshot because it provides a wonder-ful contrast to the formal portraits.

—Lorna CondonCurator of Library and Archives

LittleWomen

Gift

of W

eld

Co

xe

ABOVE Grace Bowen and her doll were similarly

attired when they had their portraits made about

1862. The doll was probably French in origin.

Photograph by E. M. Douglass.

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:49 PM Page 14

Gift

of

the

Mis

ses

Cum

min

gs

15Summer 2006 Historic New England

FACING PAGE, BELOW Too big to hold, the elaborate bride doll

sits next to her same-sized owner.The doll is as much a sub-

ject of the image as the child. Both child and doll have tinted

cheeks, and in fact, they even resemble one another. This

carte de visite dates to c.1865. LEFT Ten-year-old Edith A.

Moffat proudly displays her well-dressed baby doll and her seal

muff. The back of this cabinet card imparts the sad informa-

tion that Edith died on May, 11, 1887, aged twelve years and

five months. Photograph by Walter E. Chickering Company.

CENTER A mid-ninteenth-century daguerre-

otype depicts an unidentified young girl

with a china doll. ABOVE RIGHT Sisters Harriet

Alma and Emma Gertrude Cummings

wore matching dresses, and so did their

china dolls, when they posed for the pho-

tographer about 1864. The sisters must

have treasured their dolls, for in the 1930s,

then in their eighties, they donated one of

them to Historic New England.Anonymous

photograph. FAR LEFT Sometimes even be-

loved dolls cannot provide much needed

solace, as is evident in this circa 1920 snap-

shot of a baby. LEFT Historic New England

staff member Nancy Curtis posed with a

baby doll about 1945.Contrary to what one

might assume from the photograph, Nancy

did not particularly care for the doll. It was

her parents’ wish to include it to enhance

the composition.Photograph by Ann Curtis.Gift

of

Nan

cy C

urti

s

Gift

of W

eld

Co

xeG

ift o

f R

.T.M

off

att

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:50 PM Page 15

William Morrisin New England

Historic New England Summer 200616

1861, he became a partner in Morris, Marshall, Faulkner &Company, whose aim was to improve the quality of decora-tive arts. Thirteen years later the partnership was reorganizedas Morris & Company, with Morris in charge. Some Morriswallpapers and textiles were available in Boston as early as1873; the 1883 foreign fair that young Codman visited wasthe first time the firm’s entire range of products was viewedby a large number of people in the city.

Codman was enamored with what he saw, and when hisfamily returned to their home in Lincoln, Massachusetts, thenext year, he appears to have persuaded his mother, who heldthe purse strings, to purchase fabric to use in at least tworooms. For curtains and upholstery in his own room,Codman chose the Brother Rabbit pattern, combining it withnew wallpaper and carpet in Morris-inspired patterns.

At about the same time, the Codmans added a largewing to the rear of the house with a new kitchen and ser-vants’ rooms. The former servant’s room over the old kitchenwas transformed into “the new spare room,” in whichantique furniture was combined with hygienic modern ironbeds. Fabric in the Rose and Thistle pattern, printed in ochre

n November of 1883, in his weekly letter from Boston tohis mother in France, twenty-year-old Ogden Codman,Jr., wrote, “I went to the Foreign Exhibition & saw somevery pretty rugs from Morris in London. He makes such

pretty chintzes and wallpapers.” Morris & Company had setup six rooms at the American Exhibition of the Products,Arts and Manufactures of Foreign Nations held inMechanics Hall in Boston’s Back Bay to display carpets,wallpapers, cut velvets, dress silks, printed cottons, tapes-

tries, embroideries and stained glass. William Morris (1834–1896) is the best

known of a group of English artistsand designers who sought toreform design and manufacturebeginning in the mid nineteenthcentury. Morris was a sort ofRenaissance man who becametotally absorbed in his manyinterests, which ranged from

pattern designing to poetry andfrom dye technology to socialism. In

I

“Have nothing in your

houses that you do not

know to be useful or

believe to be beautiful.”

—William Morris, 1882

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:50 PM Page 16

17

FACING PAGE,TOP Ogden Codman’s bed-

room,c.1885.The Brother Rabbit fabric

(see contents page), designed in 1882,

was used for curtains and on a newly

purchased “Morris chair” (below left).

The same design in red covered the

box to the right of the fireplace and a

chair cushion.

THIS PAGE, LEFT The Codmans’ “new

spare room” with curtains in the

Rose and Thistle pattern of 1881.

BELOW Architect H.H. Richardson

hung several woven woolen fab-

rics by Morris as portieres in

Brookline, Massachusetts. Tulip

and Rose (1876) is seen in the

rear center.

BACKGROUND An unused length

of the Rose and Thistle fabric left over

from the “spare room” curtains.

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:51 PM Page 17

Historic New England Summer 200618

ABOVE (LEFT TO RIGHT) Wallpapers retailed by A.H.Davenport includ-

ed Trellis, Morris’s first wallpaper design registered in 1864,

Sunflower (1879), and Triple Net (1891). BELOW Marigold (1875) was

chosen for the Colonial Revival parlor of a house designed by

William Ralph Emerson in Cohasset, Massachussetts.

Lesser Arts of Life,” he made one of his better known pro-nouncements, “whatever you have in your rooms think firstof the walls; for they are that which makes your house andhome.” His emphasis on wall treatments, however, does notnecessarily mean that he favored wallpaper over any of theother elements he designed for interiors. He took a holistic

approach to interior decoration, in whicheach element contributed to the overalleffect and nothing was superfluous. Heoften combined many different patternsin a room while allowing none of them todominate.

Morris’s aesthetic, his respect forhandcrafts, and his products all had anenormous effect on the Arts and Craftsmovement in America and were particu-larly embraced in Boston. While Morris

had no interest in visiting the United States, several influen-tial individuals from New England, including H. H. Richard-son, arranged to meet him when they were in England.Richardson was impressed with Morris’s “straight forwardmanner” and the two found a common interest in pre-indus-trial, especially medieval design. Richardson incorporated

Pho

togr

aphs

by

Dav

id C

arm

ack

on a white ground, was made up into floor-length curtainsand must have looked stunning against the deep red paintedwalls.

On his way to becoming an interior designer and archi-tect, Codman worked briefly at A. H. Davenport, Boston’smajor distributor of Morris fabrics and wallpapers. AlbertH. Davenport began business in 1880with showrooms occupying a five-storybuilding on Washington Street. The firmcatered to the upper end of the marketand even had a branch in New York City.Davenport himself used several Morriswallpapers in the house he built for hisfamily in his native Malden, Mass-achusetts, in 1891. The company mergedwith Irving and Casson in 1916 and con-tinued to provide Morris papers to NewEngland homes until about 1934, when it relocated its show-room and apparently sold the wallpaper inventory. Most ofthe Morris wallpapers in Historic New England’s collectioncome from this remaining stock.

William Morris frequently lectured on interior decora-tion. In 1882, discussing wallpaper in a talk entitled “The

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:51 PM Page 18

19Summer 2006 Historic New England

ABOVE Fragments of carpets Wreath (c. 1880), at top, and Lily

(c. 1875), below, from Jewett House retain their original coloring.

RIGHT Arthur Little stands in the morning room of his Boston

Morris & Company’s products in many of his commissions,notably the Glessner House in Chicago, and featured some inhis own studio and library in Brookline, Massachusetts,where they could be promoted to his clients and discussed byhis apprentices.

In New England, many Morris designs found their wayinto houses designed in the style we call Colonial Revivaltoday. Architect Arthur Little was an early proponent of thisrevival. In the preface to his 1878 volume of sketches, EarlyNew England Interiors, he urged that “we on our side of thewater should revive our Colonial style,” much in the mannerthe English were reviving their classical style. In the house hebuilt for himself in 1892, Little created eclectic interiors com-bining Georgian- and Federal-style woodwork, French andAmerican antiques, French silks, and Morris printed cottons.Rather than use wallpaper in his morning room, Littlestretched Morris & Company’s second most expensive printedcotton, Wandle, on the walls. Morris frequently suggestedusing fabric on walls, and did so in his own rooms, but herecommended it be tacked in folds, not stretched taut asLittle did.

In addition to designing printed and woven furnishingfabrics, the indefatigable Morris created designs for carpets.

His hand-knotted carpets are best known, but he alsodesigned less expensive, commercially woven patterns, whichwere produced in several different weaves. The two shownhere were used at different times in the stairhall of HistoricNew England’s Sarah Orne Jewett House in South Berwick,Maine. Never exposed to light or dirt, having been cut offduring installation and stored in a trunk, these remnants pre-serve their original intense, jewel-like colors. The Jewett sis-ters traveled in a circle of friends who appreciated Morris’sartistic philosophy and no doubt felt that these patterns suitedthe colonial architecture of their family house.

William Morris’s goal was to bring beauty into thehome. It is testimony to his genius that his designs haveendured for more than a century. While many of his patternshave been revived over the years, some have never gone outof production.

—Richard C. NylanderSenior Curator

house, which features two Morris fabrics. Honeysuckle (1876) is

draped across the sofa, on which Little’s friend, Miss Palfry, reclines,

while Wandle (1884) is stretched on the walls.

Historic New England reproductions of the Codman Rose andThistle and the Jewett Wreath carpet are available through J.R.Burrows & Co.; visit www.burrows.com for information.

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:51 PM Page 19

Historic New England Summer 200620

arades, music, speeches, andfireworks all are part of thefestivities marking Indepen-dence Day. Over the years, the

holiday has evolved and adapted to changing politics and social move-ments, yet commemorating the democ-ratic traditions that this nation standsfor has remained a constant theme.

Even as the Revolutionary Warwas being fought, some cities set off fireworks to celebrate the firstanniversary of the signing of theDeclaration of Independence, and in 1781, the Massachusetts legislaturepassed the first official designation of Independence Day. After the hostili-ties ended in 1783, the Fourth of Julywas observed throughout the youngcountry, though more frequently in thepopulous North than in the South.Independence Day celebrations helped

cement the union and foster growingnationalism.

The early celebrations tended tofollow the pattern of familiar holidaysduring the colonial era, such as theannual observation of the King’s birth-day, with its proclamations, dinners,and toasts. The events of the dayfell into two categories: whathistorian Len Travis hascalled “ceremonial rit-uals,” like the readingof the Declarationof Independence andthe parading of themilitia, and “celebra-tions,” meaning bon-fires and a great deal ofdrinking. Typically, can-non fire and ringing churchbells ushered in the day. Events includedmilitary processions and exercises, ora-tions or sermons, and dinners and

P

S P O T L I G H T

toasts—thirteen was a favorite numberof the latter, but they could easily beexpanded on. Readings of the Declar-ation of Independence were wide-spread, as were orations by prominentcitizens, such as Harrison Gray Otis in1788 and Josiah Quincy in 1798.

Fireworks displays appearedwith increasing frequency

as the nineteenth centuryprogressed.

The day’s tradi-tion of oratory meantthat the Fourth ofJuly could easily bemanipulated for po-

litical ends. In the lateeighteenth century, Fed-

eralists and anti-Feder-alists used the occasion to rally

their followers at separate staged events,which were sometimes contentious and,in the early 1800s, even erupted into vio-

THIS PAGE Flags and costumes are re-

current themes in July Fourth celebra-

tions: at left, in Danville, Vermont, in

1952, shot by Verner Reed; and below,

in an unidentified image, c. 1890.

FACING PAGE, CLOCKWISE Invitation to Henry

Bowen’s festivities, 1877 (see p. 5).

Postcard, after 1907, illustrates variety

of fireworks available to children.

Newspaper reports of children injured

by fireworks spurred reform efforts to

restrict their use to public displays.

House in Dorchester, Massachusetts,

1892. Flags, lanterns, and yards of

bunting were used to decorate Henry

Bowen’s Roseland Cottage.

The Glorious Fourth

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:51 PM Page 20

21Summer 2006 Historic New England

by the far the largest and most elab-orate. Nonetheless, the importance ofthe day as a holiday continued todecline as did the patriotic characterof the celebrations themselves.Harper’s Weekly and local news-papers bemoaned the decline ofthe holiday, as formal events gaveway to more boisterous forms of celebration. By the 1870s,Christmas, a family-centeredevent, was becoming firmlyestablished as the most pop-ular holiday of the year. TheLynn [Massachusetts] Semi-Weekly Reporter opined “even theGlorious Fourth has taken a back seatwhen compared with the 25th ofDecember.”

Towards the turn of the twentiethcentury and the beginning of theProgressive Era, reformers sought toreintroduce the patriotic values of theearly Independence Day commemora-tions, motivated in part by a desire toinstill American values in a growingimmigrant population. Many townsand cities successfully sought to includeimmigrant groups as participants informal exercises and festivities.

In the later twentieth century, theholiday evolved to what we knowtoday, a combination of public and pri-

lence. Often, the speeches expressed theviews of political parties—temperancein the 1830s and 1840s, or abolitionfrom the 1830s on. In 1854, AndrewLeete Stone’s oration in Boston con-demned the Fugitive Slave Law, and in1857, the clergyman William Rounse-ville Alger, spoke on his anti-slaveryviews. One of the most famous ora-tions on this topic was delivered byFrederick Douglass in 1852, “What tothe Slave is the Fourth of July?,” aspeech sponsored by the RochesterLadies’ Anti-Slavery Society at Roches-ter Hall, Rochester, New York.

With the coming of the Civil Warand the division of the union, the holi-day declined as a public celebration.Festivities in the North tended to besubdued, and in the Confederacy theday was hardly acknowledged. Theend of the war in 1865 occasionedlarge celebrations in the North, andfinally, in 1870, the United StatesCongress established the Fourth of Julyas a federal holiday.

The nation’s Centennial in 1876inspired a renewed interest in thefounding of the country and its demo-cratic ideals and helped foster massiveobservations throughout the nationthat year. Celebrations in Philadelphia,host to the Centennial Exhibition, were

vate events, parades,and fireworks. His-

torian Diana Karter Appelbaum hascalled the day a “backyard holiday”—a gathering of friends and family cen-tered on a barbecue. The Fourth ofJuly today still celebrates the country’sbirth and democratic ideals and willcontinue to adapt to reflect currentevents and our collective nostalgia. So,strike up the band, light the barbecue,and watch the fireworks!

—Ken TurinoExhibitions Manager

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:52 PM Page 21

Historic New England Summer 200622

L A N D S C A P E

white rose grows on thequiet northeast side of theSarah Orne Jewett Housein South Berwick, Maine.

The family compound was the life-longhome of Jewett, the eminent nineteenth-century author. The rose, one of ruggedstock, could easily have been there sincethe eighteenth century, when the housewas built.

The flowering shrub is seven feettall and four feet wide. Its canes bowgracefully, especially in late June andearly July as clusters of three-inch whiteroses unfold, the kind that draw theoccasional passerby with their fra-grance. The buds and nascent blossomshave a faint blush. Then the full flow-ers—a double form with many petals—take on a creamy warmth, as if thegolden stamens at the center were radi-ating their hue.

This is a subtle progression of tone,but the rose truly is white, both inappearance and by classification. It isRosa alba ‘Maxima.’ The alba (white inLatin) family of roses blooms in a deli-cate range of whites and pinks, a veri-table bridal bouquet. Even after bloom,Jewett’s white rose is an elegant archingplant with gray-green leaves of mattefinish and orange oval fruit in the fall.

It makes the most of a few hoursof sun each day and requires littlecare.

Sarah Orne Jewett (1849–1909) grew up with old roses andkept them in her gardens and herwriting. The sympathies of theheirloom flower enthusiast are evi-dent in Jewett’s intention as a writer: “Ihave always meant to do what I couldabout keeping some of the old Berwickflowers in bloom, and some of thenames and places alive in memory, forwith many changes in the old town theymight be soon forgotten.”

Old roses like ‘Maxima’ were outof style, routed in favor of the latesthybrids, when Jewett published alament for lost gardens, “From AMournful Villager” in 1881. She evokedthe presence of roses in her childhood,“the taller rose-bushes were taller thanwe were, and we could not look overtheir heads as we do now.” GrandmotherJewett had a tangle of them in the cor-ner of the front yard at mid-century,including “blush roses, and whiteroses, and cinnamon roses.” Likely theblush and white were albas. Alice MorseEarle, Jewett’s kindred colleague, wrotein Old Time Gardens, 1901, that “TheBlush Rose (Rosa alba), known also as

Maiden’s blush, was much esteemedfor its exquisite color… .”

Jewett’s autobiographical writingreveals private moments in the nightgarden, among the roses. In “TheConfession of a House-Breaker,” 1893,Jewett stole out of the house when “thewhite flowers looked whiter still in thepale light” and the great clusters ofroses were heavy with dew and per-fume.

“The White Rose Road,” 1889, isJewett’s tribute to Rosa alba, the truestory of a buggy ride into the country-side in June of that year. She went call-ing in a neighborhood of strugglingfarms and found “every one of the oldfarmhouses has at least one tall bush ofwhite roses by the door,” swaying inthe breeze “with a grace of youth andan inexpressible charm of beauty.”Jewett witnessed the hardships ofagrarian decline on a glorious midsum-mer day. The white rose was to her an

A

Sarah Orne Jewettand theWhite Rose

Gar

y W

etze

l

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:52 PM Page 22

23Summer 2006 Historic New England

gardens Jewett loved, with their rose,honeysuckle, and lilac shrubs and acomplement of daffodil, peony, lark-spur, London pride (Maltese cross),hollyhock, tiger lily, phlox, and asterfor full-season display.

Along the white rose road, Rosaalba ‘Maxima’ had never fallen fromfavor. Perhaps the ‘Maxima’ seentoday at the Sarah Orne Jewett Housewas not planted in the eighteenth century. Perhaps Jewett was given ashoot that day in June 1889 and planted the white rose herself, for all its rich associations.

—Nancy Mayer WetzelLandscape Gardener

ABOVE Woodcut from The Herball or General

Historie of Plantes by John Gerard, 1633

edition. LEFT Rosa alba ‘Maxima’ flourishes at

South Berwick farmhouses. The shrub pro-

duces cascades of flowers in full-sun locations

but is noted for blooming—albeit less pro-

fusely—in part shade.

emblem of renewal—and, indeed,‘Maxima’ thrives at an old farm on theroad today.

The enduring alba is one of theoldest families of garden roses; its ori-gins are unknown. Rosa alba ‘Maxima’probably appeared well before the fifteenth century, and it is certainly thetranslucent, double white rose inRenaissance paintings. ‘Maxima’ wassurely among the first roses brought toAmerica. It was not seed that thecolonists sowed, for garden roses don’tproduce identical plants from seed, butrather “new shoots from the root weregiven one neighbor to another,” just as Jewett explained in “The White Rose Road.” That means every‘Maxima’—from shoots, cuttings orgrafts—is literally the same stuff, aremarkable historic continuum.

Few roses have so many names asthe venerable ‘Maxima.’ Did Jewettknow that her rose is one of thosecalled the White Rose of York? In thefifteenth-century Wars of the Roses,English factions wore rose badges.York’s rose was white, and Lancaster’swas the red Rosa gallica ‘Officinalis.’Jewett, however wittingly, paired themagain when she said the white farm-house rose reminded her of a red colo-nial rose in nearby Kittery. Possibly itwas ‘Officinalis,’ which persists in theold burial ground at Kittery Point. Did

Visit the Sarah Orne Jewett House,Fridays through Sundays, 11 am–4 pm,through October 15.

Jewett, who recorded Berwick’s Scott-ish ancestry in “The Old Town ofBerwick,” 1894, know her rose isBonnie Prince Charlie’s Rose, theJacobite Rose? ‘Maxima’ was the sym-bol of the 1745 Jacobite Rising, whenCharles Stuart led Scottish clansmen—wearing white rosettes—in a failed bidfor the English throne.

Jewett’s farmhouse rose is alsoknown as the Great Double White ofEnglish cottages. Gertrude Jekyll,British garden designer and author ofWood and Garden, 1899, describedsettings not unlike those of “The WhiteRose Road”: “How seldom one seesthese [alba] Roses except in cottagegardens; …what Rose is so perfectly athome upon the modest little waysideporch?” Jewett had a first edition ofJekyll’s book in her library.

The old-fashioned roses were res-cued from obscurity in the last century,and now they are preferred by some fortheir fine scent and profuse bloom,charming flowers and pastel colors.They are healthy and hardy. Jewettcalled ‘Maxima’ a “rose-tree”—treelong being a term for alba’s upright-ness. ‘Maxima’ can be used as an infor-mal hedge at the back of a border.Mixed shrub groupings, especially withevergreens, benefit from ‘Maxima’s’loose form. It will climb, if supported.‘Maxima’ is perfect for the exuberant

Sand

y A

graf

ioti

s

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:52 PM Page 23

Historic New England Summer 200624

News New England & Beyond

Friends, fun, and fundraisingat winter galaThanks to the many friendswho turned out for the JanuaryBenefit Auction Gala and thelively performance of auction-eers extraordinaire Leigh Kenoand Leslie Keno, Historic NewEngland’s winter fundraisingevent was a huge success. Morethan 150 guests joined commit-tee co-chairs Maureen FennessyBousa and Victoria TowersDiStefano at the Ritz Carlton,Boston, for a festive dinner atwhich the Keno brothers auc-tioned items as diverse asworks of art, a weekend at theRitz Hotel in London, a privateyachting party, and a week’sstay at a Cape Cod vacationhome. Funds raised by the galawill be dedicated to supporteducational programs and out-reach.

LEFT Committee co-chairs Victoria

Towers DiStefano and Maureen Fenn-

essy Bousa.

CENTER Historic New England board

members Janina A. Longtine, M.D.,

Anthony Pell, and Mary Ford Kingsley.

RIGHT Historic New England President

Carl R. Nold.

ABOVE Mrs. I.W. Colburn, Susan Paine, and Edward C. Johnson 3d with event auc-

tioneers Leigh and Leslie Keno.

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:52 PM Page 24

25Summer 2006 Historic New England

Edgartown landmark to be protectedThe Fisher-Bliss House on North Water Street in Edgartown, Martha’sVineyard, Massachusetts, will soon beprotected through the StewardshipProgram at Historic New England. Theformer home of Captain Jared Fisher,built in 1832 by master builderThomas M. Coffin, the building is anexample of the transition from Federalstyle to the emerging nineteenth-centu-ry style of Greek Revival and also illus-trates the popularity of the ColonialRevival style.

The house was built for CaptainGeorge Lawrence, who sold it toCaptain Fisher prior to completion. Itremained in the Fisher family until

1964. In 1966, Eleanor B. Radley gave the property to the Society for the Preservation of New EnglandAntiquities (now Historic New Eng-land). The property never operated as apublic museum, but has been main-tained by the organization and used forsummer rentals. After a thorough eval-uation, Historic New England hasdetermined that the best way to pre-serve the house is through private ownership and protection throughStewardship Program preservationrestrictions.

The Stewardship Program is theadministrator of preservation and con-servation restrictions held by HistoricNew England on privately owned his-toric properties across New England.The program creates partnershipsbetween homeowners and HistoricNew England using deed restrictions toprotect a property’s historic character.Through preservation restrictions,Historic New England retains responsi-bility for working with present andfuture owners to protect specific fea-tures of a house from alteration orneglect. Buildings benefit from on-going care by preservation-mindedowners, are returned to the tax rolls,and continue in active use under thewatchful eyes of qualified preservation

staff. Established in 1981, the programis an outgrowth of the organization’sPreservation Management Program, aninitiative undertaken in 1966 to deter-mine the most effective way to preservehistoric houses that were given to theorganization but did not meet themany requirements for operation as amuseum.

At Fisher-Bliss House, the preser-vation restrictions will add an addition-al layer of protection to that alreadyafforded by the local historic district.Features such as the prominent wid-ow’s walk will be protected, ensuringthat the sweeping views of the townand harbor will always visually connectthe house to its role in Edgartown’smaritime history. Also to be protectedis the barn, a significantly intact bal-loon-framed building with exterior ver-tical board siding and a cupola.Interior protection will include scenicwallpaper, several built-in cupboards,staircases, and fireplaces. The Fisher-Bliss House will be the seventy-fourthNew England property protected byHistoric New England’s StewardshipProgram, and the fifty-third inMassachusetts.

Robert Pemberton joins Board of TrusteesHistoric New England is pleased to welcome Robert A. Pemberton to theBoard of Trustees. Bob Pemberton has been involved in the computer soft-ware business since the late 1960s, specializing in easy-to-use solutions forcomplex enterprises. He has provided solutions to groups as diverse as thecasino industry and the Royal Mail. He founded Infinium Software, an enter-prise software firm which he took public in 1995 and sold in 2002. His cur-rent business focus centers on non-profit work and growing start-up firms.Pemberton's extensive background in the computer industry will helpHistoric New England as it prepares to update computerized collections andlibrary management systems. He is also a trustee of Regis College in Weston,Massachusetts, and a life trustee of Cape Cod Academy in Osterville,Massachusetts. Pemberton serves as chairman of the Bank of Cape Cod, anew commercial bank scheduled to open in Hyannis, Massachusetts, in 2006.

Verner ReedFreelance photographerand generous donorVerner Reed died onFebruary 28 at his homein Falmouth, Maine. In2002, Mr. Reed gavemore than 26,000 pho-tographic negatives to

the Library and Archives collection. Aselection of Reed’s work tours theregion in the exhibition A ChangingWorld: New England in the Photo-graphs of Verner Reed, 1950–1972. A display of his photographs of John F. Kennedy was on view at the OtisHouse Museum during the summer of 2004.

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:52 PM Page IBC

A C Q U I S I T I O N S

141 Cambridge StreetBoston MA 02114-2702

Presented by theSociety for the Preservationof New England Antiquities

Non-Profit OrganizationU.S. Postage

PAIDBoston, Massachusetts

Permit No. 58621

and women ele-gantly dressed inthe latest Parisstyles explore thefortifications whereGeorge Washing-ton and HenryKnox had stagedthe siege of Bostonin March of 1776.Near the center, agentleman pointsto the ship housesat the CharlestownNavy Yard andwhat appears to bethe Bunker Hill Monument in the dis-tance. Bartlett must have seen the pub-lished images of the proposed monu-ment—the structure was not completeduntil 1842, six years after his sketchingtrip to Boston—and included it toensure that his depiction would be upto date.

—Richard C. NylanderSenior Curator

ABOVE Boston from Dorchester Heights, oil

on canvas, attributed to Victor de Grailly,

c.1845.The painting is a gift of Mrs. Eleanor

Norris in memory of her mother, Madeleine

Tinkham Miller, an early member of

Historic New England and herself a donor

to the collection.

his colorful painting depictsthe Boston skyline as itappeared in the 1830s.Familiar landmarks include

the Bulfinch State House and thesteeples of the Park Street Church andthe Old South Meeting House nearby.

The painting is attributed to Victorde Grailly (1804–1889), a French artistwhose views of the American land-scape include Niagara Falls, scenes on the Hudson River and in the White Mountains, and Washington’shome and tomb at Mount Vernon.Interestingly, De Grailly apparentlynever visited the United States but usedprints as his source material. Thispainting copies an engraved illustra-tion in Nathaniel Willis’s two-volumework American Scenery, published inLondon in 1840, whose images werebased on sketches by the English artistWilliam H. Bartlett.

As he did in many of his paintings,De Grailly added more people andbrightly colored flowers to enliven the scene he was copying. Here, men

T

Boston fromDorchester Heights

12062.LA 5/10/06 4:52 PM Page BC