Historic New England Summer 2014

-

Upload

historic-new-england -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Historic New England Summer 2014

ELIZA SUSAN’S WORLDSUMMER 2014

ELIZA SUSAN’S WORLDSUMMER 2014

HistoricNEW ENGLAND

F R O M T H E C H A I R

This issue offers you a wonderful sampling of Historic New England. Preview the recent improvements at Quincy House in Quincy, Massachusetts, that are part of a three-year interior restoration project. Learn about the painstaking re-creation of the original roof at Roseland Cottage in Woodstock, Connecticut, made possible through our Preservation Maintenance Fund. Discover the stories of African Americans who worked two hundred years ago at Casey Farm in Saunderstown, Rhode Island. Study the collection of architectural drawings and a photograph that documents a fashion-able Victorian house, and view some of the many cultural landscapes in private ownership that are protected from devel-opment through Historic New England’s Stewardship Easement Program.

More people than ever are visiting our historic properties, participating in our programs and events, and accessing resources and collections through our web-site. Membership is at its highest level in our 104-year history.

Much of what we offer to the pub-lic engages families and young audiences, including school and youth programs across the region that serve more than 45,500 chil-dren each year. Our lively and creative pro-grams are capturing the imaginations of the young and educating the preser-vationists of the future. Thank you for your mem-bership and your support of Historic New England.

—Roger T. Servison, Chair

HistoricNEW ENGLAND

Summer 2014Vol. 15, No. 1

Historic New England141 Cambridge StreetBoston MA 02114-2702617-227-3956

© 2014 Historic New England. Except where noted, all historic photographs and ephemera are from Historic New England’s Library and Archives.

HISTORIC NEW ENGLAND magazine is a benefit of membership. To become a member, visit our website, HistoricNewEngland.org, or call 617-994-5910. Comments? Please call Kris Bierfelt, editor. Historic New England is funded in part by the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

Executive Editor: Diane Viera Editor: Kris Bierfelt Editorial Review Team: Nancy Carlisle, Senior Curator of Collections; Lorna Condon, Senior Curator of Library and Archives; Jennifer Pustz, Museum Historian; Sally Zimmerman, Senior Preservation Services Manager Design: DeFrancis Carbone

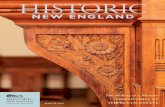

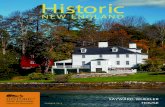

COVER View of the newly re-created entry hall at Quincy House.

EVERYONE’S HISTORY 1Hooray for the Quincy Cats!

LANDSCAPES 2Preserving Historic Landscapes

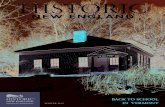

KIDS MATTER 4Sunshine, Fun, and Learning

MAKING LEARNING FUN 13Understanding Change

FROM THE ARCHIVES 18Rediscovering a House on Montana Street

YOUR SUPPORT AT WORK 21Better Care, More Space, and More Accessibility

PRESERVATION MAINTENANCE 22Details Matter

PROGRAM HIGHLIGHT 24Medicinal Herbs

HOUSE STORY 26

What’s in a Name?

SPOTLIGHT 28The Fanlight: Delicacy and Light

YESTERDAY’S HISTORY 30Orchard Walls, “Lost Days,” and Elections

ACQUISITIONS 34A New Haven Back Yard

Eliza Susan’s World 8

Family Values 14

1Summer 2014 Historic New England© 2014 Historic New England. Except where noted, all historic photographs and ephemera are from Historic New England’s Library and Archives.

E V E R Y O N E ’ S H I S T O R Y

Founded in 1874, the Quincy Yacht Club, in Quincy, Massachusetts, emerged as a dominant force in the Massachusetts Bay regatta season, thanks in part to

the club’s Challenge Cup, proposed in 1898. Calling for boats no longer than twenty-one feet,

which might require only a three-man crew, the Challenge’s smaller speci-fications brought the luxury sport of yacht racing within reach of people who were not extremely rich. By contrast, yachts built for the America’s Cup races were often one hundred feet long with crews of seventy, mak-ing that prize something only the world’s wealthiest men could pursue.

In 1916, Quincy Yacht Club member Carl Snow created the first one-design racing class yacht, a fifteen-foot catboat—a type of sailing vessel with

one mast set far forward, typically with a gaff-rigged sail. The design was so innovative that it caught the attention of the Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels. Before Snow could deliver the first order of these compact and agile “Quincy cats,” Daniels cabled the yacht club, “You will appreciate that these small crafts would be very efficient in case of difficulties with any foreign powers in the destruction of undersea boats that might threaten our coast.” The government commandeered the fleet and held it at the ready to patrol Boston Harbor for enemy submarines. Fortunately, the catboats were never needed in that capacity and returned to race from 1917 to 1940.

With their masts down, the Quincy catboats looked a little bit like bathtubs. When the fleet took part in regattas, competing yachtsmen would tease good naturedly, “Rub a dub dub, three men in a tub—hooray for the Quincy cats!” By the 1930s, many Quincy cats had been handed down to members’ children in favor of newer designs. As powerboats increasingly came into favor, the Quincy cat fleet eventually disappeared. Today, the club no longer hosts regattas but remains active in the Quincy Bay Race Week Association, while several other local clubs continue to compete for the prestigious Quincy Yacht Club Challenge Cup. —Kris BierfeltEditor and Publications Manager

ABOVE The catboat Dorothy (shown

here with a Bermuda rig) sails

in Quincy Bay in the mid-1930s.

Tickets admitted Quincy Yacht

Club members and their families

to community events.

Hooray for the Quincy Cats!

To learn more about the Quincy Yacht Club and to view an online exhibition, visit HistoricNewEngland.org/EveryonesHistory.

Photo courtesy Trustees of the Boston Public Library/Leslie Jones Collection. Ephemera courtesy Quincy Historical Society.

2 Historic New England Summer 2014

L A N D S C A P E S

The preservation restrictions that protect properties in Historic New England’s Stewardship Easement Program frequently identify landscape features that must be maintained. For example, an easement can protect a property’s fields, garden beds, pathways, trees, stone walls, and fences

from insensitive alteration and can also prevent subdivision. Here are just a few highlights from the ninety-two properties in the Stewardship

Easement Program. In each case, the easement allows the landscape to continue as the setting for the property owner’s daily life, while ensuring that the history of the site remains intact for future generations.

Whether part of a large farm or an urban lot, cultural landscapes pro-vide settings for daily life and often reflect changes in available resources, tastes, and lifestyles over time. Many of New England’s landscapes have historic significance and are worthy of preservation, but they are highly vulnerable to neglect or redevelopment.

Preserving Historic Landscapes

3Summer 2014 Historic New England

Muster Field (facing page)

Muster Field Farm in North Sutton, New Hampshire, is named for the annual militia gathering and social event known as Muster Day, which took place in the farm’s large flat field at the turn of the nineteenth century. An allée of mature sugar maples frames the entry to the c. 1784 farmhouse. This formal landscape alludes to the house’s history as a tavern from 1784 to 1859, a period when taverns were important political and social institu-tions in New England.

Now operated as the Muster Field Farm Museum, the site continues to pro-duce hay, vegetables, herbs, and flowers and hosts several annual community events. Continuing farm operations at the site help preserve broad viewsheds in all directions, including the view to Mount Kearsarge in the east.

Keith House (below left)

The Town of Bridgewater, Massachu-setts, joined with the Massachusetts Department of Fish & Game and Historic New England’s Stewardship Easement Program to preserve the c. 1783 Keith House and fourteen acres of open space. Adjacent to Lake Nippenicket, this large expanse of sce-nic land is permanently protected from subdivision and development, and the historic relationship of the house with its surroundings remains intact.

David Webb, Jr., House (above)

The c. 1786 David Webb, Jr., House, in New Canaan, Connecticut, operated as a subsistence farm until the early twentieth century, when it became a country retreat. The Colonial Revival landscape features a terraced garden with perennial beds, trees, and shrubs as well as evidence of one of the oldest roads in New Canaan, at right, which survives as a manicured lawn resem-bling a bowling green.

Flansburgh House (below right)

The Modernist landscape at the Flans- burgh House, in Lincoln, Massachu-setts, designed by architect Earl R. Flansburgh in 1963, features asym-metrical pathways, low-maintenance plantings, and sculptures throughout

the garden. The design emphasizes horizontality and views of the land-scape from indoors. Low stone walls delineate planting beds and evoke the character of New England’s distinctive historic stone walls. Patios, all without view-obscuring railings, extend the liv-ing space into the landscape. Floor-to-ceiling windows and an interior court-yard emphasize the natural setting.

—Carissa DemorePreservation Services Manager

Learn more about our Stewardship Easement Program at HistoricNewEngland.org/stewardship.

4 Historic New England Summer 2014

K I D S M A T T E R

Adecade ago, Historic New England began offer-ing summer day camps to the communities surrounding two of its working farms, Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm in Newbury, Massachusetts,

and Casey Farm in Saunderstown, Rhode Island. As they enjoy activity-filled days, the children absorb the special atmosphere of these historic sites and come to appreciate the importance of preserving them.

From Little Farmers to Farm AdventuresSpencer-Peirce-Little Farm welcomes families year-round with special programs, like the Draft Horse Plow Match and Vintage Base Ball, and as open land to explore. During the school year, there are morning programs for toddlers and

“It makes me happy to see my child jump out of the car, wanting to start his day on the farm.”

preschoolers and after-school programs for older children. And in the summer, children come to camp.

Little Farmers is a one-week morning camp, offered in two sessions with a limit of twenty-five participants, for children aged five to eight. The camp is so popular that in 2013 we added Farm Adventures for older children.

The campers spend their days immersed in the life of the farm. Each morning they start by feeding the ani-mals, who are fostered on the farm in partnership with the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. The kids wash their hands in the old well-pump and eat their lunch on the lawn behind the manor house and attached tenant farmhouse. In the nearby 1775 barn, with antique farm implements on display, they make crafts.

Sunshine, Fun, and Learning

Pho

togr

aphy

by

Bet

h O

ram

5Summer 2014 Historic New England

FACING PAGE Campers enjoy lunch on the lawn at Spencer-Peirce-

Little Farm. ABOVE At the Plum Island Airport, the kids loved

getting to explore different aircraft up close. BELOW Farm chores

keep campers active and invested.

Throughout their camp experience, they absorb the magic of being at this historic site and gain hands-on knowledge about the proper treatment of animals.

Every day, the older children go on an excursion to a neighboring resource, including the Plum Island Airport, which is on the farm property; Joppa Flats, a Mass Audubon site across the street; and the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge, a federal site adjacent to the farm. These adventures, developed collaboratively with our neighbors, broaden the children’s perspective. Last summer at the airfield, campers were especially impressed with what the airfield staff referred to not as a seaplane, but rather, a “flying boat.”

Summer programs at Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm would not be possible without the large group of teenage volunteers who serve as mentors to the campers. Last summer, twelve teenagers worked at the camp as part of the community service hours required by their local high schools. They not only helped with crafts and games, but each also prepared and led an activity for the campers, a responsibility they took very seriously. The children loved seeing their slightly older role models assume leadership roles and participated in these activities with enthusiasm, whether a game of concentration using photographs of the farm animals or teen volunteer Sam’s version of Simon Says, “Because Sam Says So!”

For children new to the community, a week at camp can make them feel right at home. Amy Schmidt, whose children participate in Farm Adventures, told us, “This was an amaz-ing experience for our two children, who recently moved here from an urban environment. They loved working on a farm and now count Rodger the donkey and Appleton the goat among their friends.”

“

”

“We are so blessed to live near such a wonderful farm. Our son, Alex, has been going there since he was eigh-teen months old. He has grown up at Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm. One thing Alex especially loved about Farm Adventures was getting to know other organizations close by. Having something new every day made it very excit-ing for him. We have a special place for the farm in our hearts and hope Alex will continue to participate until one day he will be one of the counselors helping Miss Arleen [Arleen Shea, Newbury Education Program Coordinator].” —Krista Yablin, mother of two Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm campers

6 Historic New England Summer 2014

Fun for every age at Casey FarmCasey Farm is always a whirlwind of activity in the summer because it operates a CSA, or Com-munity Supported Agriculture program, and raises food for more than 160 participating members and their families. Children in the summer camps are exposed on a daily basis to the work of tend-ing and harvesting the crops that feed hundreds of people.

Casey Farm offers four different camps, serv-ing children aged four to eleven. For the young-est campers, there is Little Ducklings, with three mornings in each one-week session providing a chance for the little ones to get to know the farm without committing to a full day. The camps for older children each run five days a week from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m.

As the children get older and move through the different camps, they make more and more use of the farm’s three hundred acres. While the five- and six-year-olds in Farm Friends are feed-ing the chickens, petting the rabbits, and picking snacks from the fields, the nine-, ten-, and eleven-year-olds in Farm Explorers are hiking through

LEFT Campers at Casey Farm take their responsibili

-ties very seriously. BELOW At lunchtime, kids carefully

sort their garbage and food scraps. Leftovers are fed

to the pigs.

7Summer 2014 Historic New England

the fields and forest and learning how to build a fire. All campers participate in swim day at the Pettaquamscutt River, but while the smaller ones ride the hay wagon, the older kids walk there. Everyone gets a ride back.

Respect for the environment and the humane treatment of animals is a strong theme throughout all the camps. From the very first day, children learn how to sort their trash at lunchtime, with one barrel for garbage, one for recyclables, one for food scraps, and one for compost. They learn to keep any meats out of the food scrap bucket, because one camp group will feed its contents to the pigs. Pigs will eat anything, but meat can make them aggressive. Another group is in charge of bringing the compost to the compost pile, where they dump it, then turn the pile. It becomes a goal of the campers to keep the trash barrel as empty as possible.

In addition to feeding the animals and turning the compost, campers participate in many other farm chores. One favorite is egg duty. The campers gather eggs from the chicken coops and carefully transport them to the wash-ing and grading station. They learn how to handle the eggs gently as they wash them, grade them on a special scale, and then pack them into egg boxes. These fresh eggs are then offered for sale to CSA members and at the weekly Coastal Growers’ Market. For the campers, it becomes impossible to look at a package of eggs in a supermarket the same way ever again.

If we do our job right, at the end of each day, all of our campers, whether from Casey Farm or Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm, are happy and tired, with crafts to show off and stories

to tell. They understand where their food (both vegetable and animal) comes from and how much work it takes to raise that food in a sustainable, humane way. They realize that these farms are special places worth cherishing. Most of all, they wake up the next morning eager and excited to get back to camp.

—Carolin CollinsEducation Program Manager

ABOVE Dominiques are one of two heritage breeds of chickens

raised at Casey Farm. Campers feed them and collect their eggs

daily. BELOW Campers show their enthusiasm during a rousing

game of “Guess the Artifact.”

“

”

“My kids absolutely love their experi-ence there. They have so much fun with all the farm tasks, and especially being able to spend time and interact with the animals, and all the counselors have been fabulous. I love that they get so much exercise and spend all day outside, and that they are not only having fun and making great friends, but learning so much, too. I can’t wait until my youngest son is old enough to join them!” —Michelle San Antonio, mother of two Casey Farm campers

8 Historic New England Summer 2014

In the late 1870s, eighty-year-old Eliza Susan Quincy looked back on her life with some satisfaction and realized that much of her history and that of her family was reflected in the house in which she and her elderly sisters were living. She decided to begin documenting that history through a descriptive inventory and series of photographs. More than 130 years later, Historic New England has undertaken a major project to refurnish Quincy House to reflect that moment in time when the family historian linked her family’s story to the building that four generations of Quincys had called home.

This c. 1870 view of

Quincy House shows

the final length of

the “broad and leafy

avenue” leading to the

house. Toward the

end of his life, former

president John Adams,

determined to visit his

longtime friends, came

down the drive regu-

larly but was too frail to

leave his carriage.

9Summer 2014 Historic New England

Eliza Susan’s World:Historic New England Re-creates

the 1870s and ’80s at Quincy House

10 Historic New England Summer 2014

shaped the modern world—John and Abigail Adams, John Quincy Adams, and the Marquis de Lafayette, among others, as well as some no longer as well known, such as Prince Carl Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, whose military leader-ship contributed to the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo. Literary figures and artists who visited the Quincys included John Trumbull, Washington Allston, Washington Irving, and Gilbert Stuart.

Eliza Susan was keenly aware of the historical impor-tance of the people with whom she spent time. One summer day in 1818, she accompanied the famous orator Daniel Webster to the home of John and Abigail Adams. During the carriage ride she asked Webster what he thought of John

Built by Colonel Josiah Quincy (1710–1784) in 1770, Quincy House, located in Quincy, Massachusetts, was the family’s summer home, the place to which they retreated after a busy social season in Boston or Cambridge. In the nineteenth century the Quincys lived in a succession of at least seven houses in the winter, but always returned for sol-ace and renewal to this house by the sea. A visitor in 1875 described its attraction:

[The mansion] is placed on the gentle swell of ground at the extremity of the noblest private estate in New England. Its five hundred broad acres of meadow and woodland give the idea that you have suddenly dropped into an English park come down since the Conquest by entail. A broad and leafy avenue a quarter of a mile long leads from the high-road to the mansion. There are delicious glimpses of the sea, of Boston Harbor and its islands, and of the countless white sails continually winging their way into port.

Eliza Susan came to her interest in history inevitably. She slept in the room that Benjamin Franklin used when he visited her great-grandfather. She grew up surrounded by notable historical figures. The participants in dinner conversations at Quincy House included players who influenced events that

ABOVE When the Quincy family donated the house to Historic New

England in 1937, many of the original furnishings had already been

dispersed or sold. To re-create the look of the 1880s photographs

(inset), Historic New England augmented Quincy family pieces

with other objects from its collections. A reproduction was used

for the Copley portrait of Colonel Josiah Quincy.

11Summer 2014 Historic New England

Quincy Adams’s chance of becoming the next president. As Webster contemplated what a second Adams presidency might mean for him, Eliza Susan watched closely:

His eye brow darkened, and I watched with intense interest the manifestations of a mighty intelligence. The moments I thus sat beside him were never to be forgotten. It was Mr. Webster looking forward on his brilliant,—but alas,—not unclouded career.

The men of the Quincy family were patriots, mayors of Boston (there were three), historians, leading abolition-ists, and authors. The women were equally interesting. Eliza Susan Morton Quincy, mother of Eliza Susan and her siblings, grew up in New York, the daughter of a German mother and Scots Irish father. She could recall watching from a nearby rooftop while George Washington stood on the bal-cony of Federal Hall and took the oath of office.

She was extraordinarily well read and fluent in several languages. Among her books is an early edition of Cervantes’s Don Quixote in the original Spanish. She supported female authors through establishing subscriptions and urging her friends to take part. (Many eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century authors acquired the funds to publish their work through advance subscriptions by wealthy patrons.)

Mrs. Quincy oversaw the education of her children, and her success is evident in the quality of their writing. She and

BELOW This detail of a photograph of the exterior of Quincy House

taken around 1870 may be the only known image of Eliza Susan

Quincy, who is likely the woman seated on the right. The other

woman is her younger sister, Margaret Quincy Greene. The man

is probably the sisters’ nephew, Josiah Phillips Quincy.

About Eliza SusanEliza Susan Quincy (1798–1884) was the eldest of seven

children, five daughters and two sons, of Josiah Quincy III

(1772–1864) and Eliza Susan Morton Quincy (1773–1850).

Her family had deep ties to the region’s and nation’s history.

Her great-grandfather and both grandfathers were active

patriots. Her father served in Congress, as mayor of Boston,

and as president of Harvard University. Her mother came

from a family of successful New York merchants. Because

of her family’s connections, Eliza Susan moved in the highest

political and intellectual circles and maintained a profound

interest in the world around her. Encouraged by both par-

ents, Eliza Susan became an accomplished watercolorist

and author. She edited the diaries of her grandfather Josiah

Quincy, Jr., (1744–1775) first published under her father’s

name in 1825, and revised under her name in 1874. She

made substantial contributions to her father’s History of

Harvard College and Municipal History of Boston. After her

death, members of the Massachusetts Historical Society con-

ceded that, but for their by-laws prohibiting the nomination

of women, she would have been an esteemed member.

all but one of her seven children were diarists. Their journals describe, for instance, traveling on the newly built Middlesex Canal, attending the theater night after night when the renowned actress Fanny Kemble was in town, and participat-ing in the celebrations that took place when word reached Boston of the end of the war in 1815. Together these journals provide a remarkable record of the cultural and domestic his-tory of the Boston area for much of the nineteenth century.

Eliza Susan appears from her journals to have been the most serious of the sisters, the one more inclined to describe historic events than to record gossip or comment on fashion. Perhaps she would have liked the autonomy marriage might have afforded, but it never happened. She may have been too bookish, too prim, too wrapped up in her family’s legacy. John Adams’s grandson Charles Francis Adams waspishly complained that all five of the Quincy daughters were annoy-ingly condescending, and Eliza Susan, “dictatorial,” and self-important. Instead of marrying, she became her father’s assistant and her mother’s companion. Two younger sisters also never married, and the three lived with their parents,

12 Historic New England Summer 2014

spending winters in Boston or Cambridge and summers at Quincy House. Their mother died in 1850. Their father lived to the age of ninety-three and upon his death in 1864, left Quincy House to his grandson, but gave life rights to his three unmarried daughters.

Eliza Susan’s 1879 “Memorandum Relative to Pictures, China, & Furniture &c, &c, &c” in Quincy House begins with a description of the entrance hall:

The cane furniture in the Hall was brought from China 1790, by Capt. James Magee, the tenant of the house of Mr. Merchant, in Pearl Street Boston when it was bought by William Phillips for his daughter Mrs. Abigail Quincy in 1792….This furni-ture [was] removed to this house in Quincy in 1805, when the house in Pearl St. was let to Christopher Gore….

In many ways this is a typical entry, describing the furnishings’ origins and documenting how and when items came to the house. Like many of the descriptions, this one is tantalizing for historians, offering links to the earliest years of the China trade in America, and suggesting something of the real estate transactions that occurred in Boston in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Visit Quincy House to see the refurnished first-floor rooms. Return again in 2015 when the upstairs will be completed. This year Quincy House is open for tours from 1 to 4 p.m. on the first Saturday of the month, June through October.

While Eliza Susan focused principally on pictures in the hall in her memorandum, she described more of the fur-nishings in the west parlor. For instance, the carved chairs were noted as gifts to her grandmother Abigail Phillips (1745–1798) from her father on the occasion of her wedding to Josiah Quincy II in 1769. The settee came into the family in 1748, when Colonel Josiah brought it back from Europe. It and a nearby mirror, the memorandum notes, were saved from two house fires. The ornamental cut-paper memento on the settee is described as a valentine given in 1752 to her grandmother Morton, a German immigrant who was liv-ing at the time in New Brunswick, New Jersey. As detailed as the memorandum is, it is curious that some of the items that appear in the 1880s photographs were not described. For instance, the sword (left) that belonged to the “patriot” Josiah Quincy, Jr., which is prominently displayed for the photograph (page 10, inset), does not appear anywhere in the memorandum.

During the past two years, with the help of funding from the City of Quincy’s Community Preservation Committee and from an anonymous donor, Historic New England has used the 1880s photographs and Eliza Susan’s memorandum, as well as historic paint analyses, to refurnish the first-floor rooms as they were around 1880. For the entrance hall, conservator and decorative painter Marylou Davis repro-duced an appropriate floor covering and Daniel Recoder of Waterhouse Wallhangings reproduced the wallpaper. Historic textile specialist Nancy Barnard found appropriate fabrics and created accurate window hangings for the two parlors and dining room. Historic New England’s conserva-tors treated hundreds of objects, and collection services team members cleaned, fluffed, recorded, and arranged.

The Quincy family home was at the center of Eliza Susan’s life and played a critical role in establishing her sense of herself. She died there in 1884. Were she to return today, no doubt she would recognize much of what she saw, but it seems likely, given what we know of her character, that she would also step in to correct the inevitable gaffes made in the intervening years.

—Nancy CarlisleSenior Curator of Collections

ABOVE The sash plate on the sword Eliza Susan displayed in the

west parlor is engraved “Josiah Quincy, Jr. 1775,” the year the

patriot died on his return journey from England.

13Summer 2014 Historic New England

M A K I N G L E A R N I N G F U N

I liked this project. I learned a lot more about history I had no clue about. Before, if people wanted to destroy the Hamilton House I wouldn’t have cared, but now I would most defi-nitely say no because it’s an important part of our history. I would want to preserve it, not take it down or get rid of it.

Understanding Change

I liked the field trips and seeing the archaeology sites and the digs. We learned that when the archaeologists find a piece of pottery, they can tell where it came from based on what they know about our history. That was really cool and so was knowing how slow and careful you have to be when you are doing a dig.

We talked about the successes and mistakes of the past and how we could not only learn from them but we could also build on them. Like for the mills, we could still have them but make them so they are not polluting the air and the river and the birds.

We also learned how hard it was to live back then and how really lucky we are to live in a much easier time. Back then the kids had to help sew, they had to help cook, they had to help farm, they had to learn how to build houses and hunt. Now we think about those things as fun things to do and we are not forced to do them. So I just think that if you learn about how hard it was, we can appreciate how lucky we are not to have to do all the things they had to do back then.

—Noah CaramihalisYork Middle School

The sixth grade at York Middle School in South Berwick, Maine, recently spent a semester studying history in a pro-gram called Understanding Change in the South Berwick Area of the Piscataqua Region. The curriculum was developed by their teachers in cooperation with Historic New England, the Old Berwick Historical Society, and archaeologist Neill DiPaoli. Here’s what one eleven-year-old student had to say about the project.

Noah Caramihalis (second

from left) and classmates

show off their presenta-

tion contrasting Native

Americans and early

English settlers’ use of

natural resources

in the Piscataqua region.

Family Values

39–40 Beacon

Street, Boston,

Massachusetts,

about 1865.

Photograph by

Josiah Johnson

Hawes.

14 Historic New England Summer 2014

No one creates alone. For some, home is where creativity is nurtured. Such was the Boston home of Nathan and Maria Appleton, designed and built for them and their children by archi-

tect Alexander Parris in 1819. I first became interested in the Appleton family story when I admired the ambitious writing and drawings of the Appletons’ youngest surviving child, Frances (Fanny) Appleton Longfellow (1817–1861). Later, I studied the letters of William Sumner Appleton, Jr. (1874–1947), Nathan’s grandson by his second wife, Harriot. A third member of the family then came to the foreground—Alice Longfellow (1850–1928), eldest daughter of Fanny and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. These three descendants of Nathan Appleton turned out to have more in common than

blood: they all dedicated themselves to caring for and inter-preting New England’s historic houses, each of them in his or her own distinct way.

Nathan Appleton (1779–1861) was a prodigious entre-preneur, industrialist, and cultural leader. His children grew up in the elegant home at 39 Beacon Street overlooking Boston Common, learning to tread carefully on fine pat-terned carpets and sit gently on silk-upholstered furniture. They saw Gilbert Stuart’s portraits of Nathan and Maria hanging beside European paintings of landscapes, animals, and church interiors. In the summer, Maria sometimes took the children to visit her parents in their eighteenth-century home, Elm Knoll, in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, which was also handsomely furnished.

15Summer 2014 Historic New England

In 1835, Nathan took the young Appletons off to Europe for a two-year Grand Tour. Everywhere they stud-ied styles in architecture, furniture, paintings, sculpture, silver, and porcelain. Fanny filled her sketchbooks, and in Switzerland encountered another New England traveler, the poet Henry Longfellow.

In 1841, after yet another trip to London, Fanny con-cluded, “No more England.” Two years later, she married Longfellow, who was to become his era’s preeminent literary figure. As a wedding gift for the couple, Nathan bought the 1759 mansion in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that General George Washington had used as his headquarters. Fanny reported their joy in this “noble

inheritance” and in exploring the neighborhood’s revo-lutionary landmarks. Living in their historic house, the Longfellows acquired Washington and Revolutionary War memorabilia and used it to enhance the house’s hallowed association with the country’s first president.

Fanny and Henry’s eldest daughter, Alice, is the next family member in the New England preservation story. She grew up in “George Washington’s headquarters” and

often visited her grandfather at 39 Beacon Street. She did not marry but stayed on in the Cambridge house with her widowed father and lived there for the rest of her life. Gradually, she transformed the old house into a shrine to her celebrated father.

Courtesy National Park Service, Longfellow House–Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site.

Frances Elizabeth

(Fanny) Appleton

Longfellow. Albumen

photograph of the Long-

fellow House, Brattle

Street, Cambridge,

Massachusetts.

16 Historic New England Summer 2014

Courtesy National Park Service, Longfellow House–Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site.

Alice’s efforts fused the story of George Washington with the memory of her father, whose popular writings like The Song of Hiawatha, Evangeline, and “Paul Revere’s Ride” helped define American identity from the mid-nine-teenth century well into the twentieth.

Alice was two decades older than her cousin, William Sumner Appleton, Jr. Like Fanny, Sumner was raised in the Appleton family’s treasure-filled home on Beacon Hill. After graduating from Harvard, he worked in real estate, acquiring skills that prepared him for his yet unknown mission. That crystallized during his trip to Europe, where he saw carefully preserved historic places. His passion took shape in 1910 he when founded the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (now Historic New England). In his first Bulletin to members, rallying support-ers to the cause, he wrote, “Our New England antiquities are fast disappear-ing because no society has made their preservation its exclusive object.” His new organization, with his cousin Alice Longfellow serving as officer from the outset, would do exactly that.

As the organization grew and began acquiring properties, people everywhere appealed to Sumner for help. In 1925, Lucy D. Thompson of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, wrote to warn him that the town intended to demolish two eighteenth-century Georgian mansions in order to build a new central high school. Sumner responded, “My feelings are wholly in favor of the Gold-Plunkett and Kellogg properties,” both of which had “sufficient interest from an educational, his-torical, artistic and even commercial point of view.” If the houses could not be kept in place, Pittsfield should “provide sufficient ground so the architect of the new high school will

make his plans to combine these two beautiful houses in an attractive scheme with his new school building. The two old houses should be moved only just enough to allow place for the high school.”

Sumner wrote, “What makes a city desirable as a place of business or residence is the sum total of its attractive fea-tures. It is not any one schoolhouse, or library or museum or church. It is the sum total of all these.” He cited two eastern Massachusetts precedents. The City of Boston had granted use of the Old State House to the Bostonian Society, “on the condition that it maintain there a museum, open free to the public.” The Town of Reading, Massachusetts, had pro-posed purchasing the 1694 Parker Tavern and a few acres of ground for a park. Though no park was realized, Reading did acquire the old house for its Antiquarian Society “on the condition that the society should repair and restore the house and use it as an historical and patriotic memorial, a museum of antiquities open free to the public.”

Sumner did not mention to his Pittsfield correspondent that the mansion he called “the Gold-Plunkett” house was Elm Knoll, the birthplace of his grandfather Nathan’s first wife, Maria. Rather than allude to his family connection, he added the Longfellow name to the property. Pragmatically, he wrote, “Pittsfield’s leading citizens should be able to raise money from all over the state...based on the estab-lished position that Longfellow has acquired with the public in general.” A Western Massachusetts Longfellow House was “in every way worthy as the other three already exist-

ing: Portland, [Maine’s] Wadsworth Longfellow House, Sudbury, [Massachusetts’s] The

Wayside Inn, and Craigie-Longfellow in Cambridge.”

Sumner justified using the Long-fellow name because Elm Knoll’s tall clock had inspired the poet’s popular poem “The Old Clock on the Stairs.” Inaccurately, he claimed that the Longfellows “frequently came here to the home of [Fanny’s]

maternal grandparents” and that “Mrs. Longfellow’s mother and father

were frequently at many gatherings at which Longfellow was present and which

must have been held under this roof.” Actually, by the time Fanny first brought Henry here in 1843, en route to Catskill Mountain House on their honeymoon, neither her mother nor her maternal grandparents were alive.

I see in Sumner’s use of the Longfellow name for Elm Knoll his pride in being related by marriage to the celebrated poet. To him, Henry and Fanny were the preservers of Washington’s house and were his American models for his-toric preservation. Alice Longfellow had also become a men-

17Summer 2014 Historic New England

tor to Sumner. He assisted her in inventorying the contents of the old Brattle Street house. Clearly, he applauded Alice’s preservation efforts. No wonder that he cited her parents’ Cambridge house in his attempt to save Elm Knoll.

Meanwhile, fearing that Elm Knoll might be demolished, Sumner, using his own personal funds, hired photographer A. F. Shurrocks to document it. Though the high school occupies the site today, Elm Knoll can still be studied in Shurrocks’s photographs. Sumner also managed to gather a few of its architectural remnants for a future Longfellow Room he proposed for Historic New England in Boston.

These three descendants of Nathan Appleton deserve our admiration as a family of preservationists. Henry and Fanny’s Cambridge mansion is now the Longfellow House—Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site, and the narrative of the Revolutionary War reverberates in house tours there today. So, too, does Alice Longfellow’s work to interpret the house as a memorial to her renowned poet father.

William Sumner Appleton’s vision of preservation encompassed many of the twentieth century’s practical con-cerns. For him, house preservation needed an economic base; one way to accomplish this was to make a historic property into a cultural destination. He noted how “thousands of tourists in motor cars were looking for places to go. As things stand now there is precious little to lead the summer

FACING PAGE, TOP Portrait of Alice Mary Longfellow, c. 1880.

FACING PAGE, BOTTOM William Sumner Appleton, c. 1917. ABOVE

Elm Knoll, Pittsfield, Massachusetts. INSET Postcard of Elm Knoll

with Victorian update and new name: Longfellow House, c. 1913.

motoring thousands to Pittsfield to spend a few hours and several dollars there, and yet it is self evident that if the number of motor visitors could be raised annually…picture postal cards or photographs, hotel accommodations, meals etc. all will be in demand and all will repay the city for its added expenditure it will incur in preserving these two houses.” We owe thanks to this vigilant, creative family for their legacy to preserve.

—Diana KorzenikProfessor Emerita, Massachusetts College of ArtDr. Korzenik is currently writing a book on Fanny Appleton and has authored two prize-winning books, Drawn to Art and Objects of American Art Education.

Longfellow House–Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site is open seasonally for tours. Visit www.nps.gov/long for more information.

18 Historic New England Summer 2014

F R O M T H E A R C H I V E S

Rediscovering a House on Montana Street

The Albert M. Gardner

house, Roxbury,

Massachusetts, 1896.

19Summer 2014 Historic New England

Recently, a box arrived in the Library and Archives that when opened revealed the long-lost story (or at least part of it) of a house in Roxbury, Mass-achusetts. Inside were three mounted albumen pho-

tographs of an impressive dwelling designed in a style that could be described as Stick transitioning to Queen Anne, a set of sev-enteen architectural drawings, and eleven handwritten pages detailing the specifications for the construction of the building.

From the specifications, we learned that the house was “for Mr. Albert M. Gardner, on his land on Montana Street, Ward 21, Boston. Said building was to be erected according to plans by J. H. Besarick, Architect, and under the superintendence of and to the entire satisfaction of said Architect.”

Albert Gardner was in his late thirties when he built this substantial house in about 1881. He was born in Vassalboro, Maine, in 1844, but by 1868, he was living in Boston, where he married fellow Mainer Annie Weymouth the following year. Gardner had a long career in the retail hardware business, first in partnership with M. A. Chandler and then on his own. For most of this time, his business was located on Washington Street in Boston. He was active in the New England Hardware Dealer’s Association and in the Revere [Massachusetts] Lodge of the Masons.

Architect John H. Besarick, also born in 1844, emi-grated from Canada at a young age. By 1869, he had his own practice in Boston. Although not well known today, he was a sought-after and prolific architect, designing numerous buildings in Boston and elsewhere. His work includes many houses in Boston’s Back Bay, St. John’s Seminary in the Brighton section of Boston, several churches, commercial buildings, hotels in Boston and Maine, and a summer estate on Long Island in Lake Winnipesaukee, New Hampshire. At the time he designed the Gardner house, Besarick’s office was at 32 Pemberton Square in Boston, and his residence on Virginia Street in Dorchester was just a short distance from Montana Street. He, too, was a Mason, affiliated with the Joseph Warren Lodge. How these two men became acquainted is unknown.

The survival of a group of documents such as this one is quite rare. Together the photographs, drawings, and specifications provide fascinating and important information about both the architect and the house. The drawings are done in India ink and watercolor on tracing cloth. They are heavily annotated and emended

TOP An architectural drawing of the front elevation of the

Gardner house, which closely corresponds to the completed

structure. BOTTOM First page of the detailed specifications for

constructing the house.

20 Historic New England Summer 2014

in graphite, indicating that they were used by the carpenters as working drawings to construct the dwell-ing. Comparing the four exterior elevations with the photographs, it is clear that the completed house closely matched Besarick’s original designs.

The five plans —cellar, first and second floors, attic, and roof—indicate the layout of the rooms and their sizes and finishes. The first floor included living, sitting, and dining rooms, library, kitchen, pantry, china closet, and water closet. Five chambers or bedrooms made up the second floor; three more bedrooms were in the attic, plus storage space. Information about the heating and plumbing systems is also provided. Eight drawings show how the building was framed.

The specifications for the mason’s and carpenters’ work are detailed and call for materials to be of the highest quality: the foundations and cellar walls were to be built “of the best Roxbury stone,” and the chimneys needed to be “of the best quality hard burned brick.” The carpenters were instructed to “Frame and raise the building in a good and workman-like manner and, use for same best spruce framing stock….” The roof was to be covered with “the best quality Eastern slate from the Abbott or Merrill quarries.” All windows were to be glazed “throughout with first quality double thick German glass.” The carpenters were directed to “Allow and pay the sum of seventy-five cents per foot for the stained glass in the front doors.”

Of course, it stands to reason that when it came to the hardware, the specifications indicate that “The owner will provide all the door and window trimmings throughout.” Given Gardner’s occupation, he must have been well aware of and had access to the finest materials and latest innovations and took pleasure in securing them for his home.

Today Albert Gardner’s carefully planned and well-designed house still stands on the corner of Cheney and Montana streets in Roxbury. Drastically altered except for a few remaining architectural details, it is virtually unrecognizable.

—Lorna CondonSenior Curator of Library and Archives

LEFT Framing plan for the side elevation done in

India and red ink on tracing cloth. The graphite

annotations and wear to the drawing indicate that

it was probably used at the building site. BELOW

The first-floor plan was emended to include a con-

servatory, which is visible in the lower left corner.

21Summer 2014 Historic New England

Y O U R S U P P O R T A T W O R K

Better Care, More Space, and More Accessibility

Historic New England’s collection of regional dec-orative arts is the largest in the country, compris-

ing more than 110,000 artifacts that articulate the most complete story of New England life over four centuries. Ranging from the opulent to the every-day, the objects illuminate an unparal-leled record of how New Englanders have lived. While about forty percent of these items are on view in our prop-erties, the rest are preserved at our facility in Haverhill, Massachusetts.

We are currently undertaking a major project to improve conditions for the collections storage at Haverhill. This involves housing artifacts in com-pact storage units inside a “pod” that has its own specialized HVAC system

and upgraded environmental controls. Not only will the collections be in a stable environment, but also the compact storage units will provide more space for later additions to the collections. Significant improvements to the building itself are also planned —repairs to the façade and new histori-cally appropriate windows along the railroad and alley sides.

The Collections Care Project will take two and a half years to complete. More than twenty thousand objects must be moved and rehoused, and three temporary staff will be hired to help. As each object is moved, it will be checked against the existing database, which will be updated as needed. New digital photography and conservation to stabilize fragile items will be done.

Once the existing storage space is cleared, the pod will be installed, and then the objects, now fully and accu-rately recorded, will be placed in their new home. The project is a huge effort, but the gains in protecting the collec-tions and making them readily acces-sible to the public, both on our website and for hands-on study and research, will be enormous.

This phase of the project will cost $1.6 million. We have already secured a donation of compact storage equip-ment worth $200,000, as well as a grant of $300,000 from the National Endowment for the Humanities. We need $700,000 in additional funds over the next three years to com-plete the project and required match-ing funds. We are turning to you, our members and friends, to raise the necessary funds for this comprehensive Collections Care Project.

—Kimberlea TraceyVice President for Advancement

Nicole Chalfant, collections manager, pre-

pares a pink lusterware tea set, some of

the approximately 20,000 objects that

will be inventoried, cleaned, photographed,

and rehoused as part of the Collections

Care Project.

Read about recent and upcoming conservation projects and support

the Collections Care Project today at HistoricNewEngland.org/CCF.

22 Historic New England Summer 2014

P R E S E R V A T I O N M A I N T E N A N C E

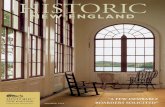

In 1845 prosperous New York merchant Henry Chandler Bowen commissioned builder Samuel Underwood to construct Bowen’s

summer home in his native town of Woodstock, Connecticut. English-born New York architect Joseph C. Wells gave the builder detailed specifications for the construction, including, “The roof of the main building to be covered with the best quality…cedar shingles…brought to an even width on each side of the house and the corners taken off thus….” At this point in the document, a small sketch (shown above) illus-trates what he meant.

Wells, a highly respected archi-tect, has been credited with some of the earliest Gothic Revival cottages in the United States; his design for Roseland Cottage recalls the theories of the influential landscape architect and writer Andrew Jackson Downing. In his book Cottage Residences, first published in 1842, Downing wrote, “A very pleasing mode of covering roofs of this kind…by procuring the shingles of equal size, and cutting the lower ends before laying them on, in a semi-hexagon or semi-octagon shape, so that when laid upon the roof, these figures will be regularly produced.”

Historic New England recently undertook major roof work at Roseland Cottage, a project that included replac-ing the wood shingle roof dating from 1980, which had begun to fail. Thanks to generous support from Connecticut’s Historic Restoration Fund and the 1772 Foundation, Historic New England was able to recreate Wells’s original concept for the shingles, fol-lowing details visible in a photograph dating from c. 1865.

Typically, Historic New England’s preservation philosophy emphasizes preserving a property with all its vari-ous accretions. In the case of Roseland

Details Matter

ABOVE This detail from a

c. 1865 stereo view of

Roseland Cottage shows

Wells’s clipped shingles.

LEFT The new roof re-

creates the design. FAR

LEFT Wells’s simple sketch

became the shape of more

than thirteen thouand

individually cut cedar

shingles.

23Summer 2014 Historic New England

Cottage, that would have meant repli-cating the existing wood shingle roof installed in 1980. But, occasionally, when historic images provide enough information, the decision is made to restore a detail that has been missing for over a hundred years. In order to create the same effect in 2013, approximately thirteen thousand western red cedar shingles were shaped on site to create shingles of a consistent six-inch width with forty-five-degree bevels at the cor-ners. The net result is the return of the distinctive pattern from Bowen’s time.

The roof restoration project also included repairing and replacing the distinctive pinnacles and pendants that adorn each of the house’s nine gables. Wells’s instructions to the builder made no reference to the design and fabrica-tion of these elements, but they are clearly visible in his elevations for the house and a watercolor rendering, both of which survive in Historic New England’s collection.

Each pendant follows the same turned design, with the principal pen-dant being about two inches greater in diameter. The pinnacles atop each gable come in two forms: six are turned and three feature an elongated pyramid rising from a turned base. At the outset of the project, three of the turned pin-nacles were missing and a fourth had toppled during a winter storm. Some of these elements could be repaired while others had to be re-created.

It is still not clear exactly how old the surviving roof elements are. The fact that there are only two or three layers of paint on each one suggests an age of twenty to thirty years, but given their hard-to-reach location, they may not have been painted as frequently as the body of the house. It is also pos-sible that some were replicated during roof work in 1980.

The Gothic Revival style was pop-ular in this country for a brief period before the Civil War, but few examples survive today. Roseland Cottage, with its nearly complete complex of land-scape and outbuildings, as well as

original furnishings, is one of the best preserved properties in the style any-where. Re-creating the original orna-mental roof pattern specified by Wells increases the dramatic impact made by this splendid and imposing country house.

—Colleen ChapinPreservation Manager

ABOVE, LEFT An ink and watercolor design for Bowen’s cottage, attributed to Wells,

c. 1846. ABOVE, RIGHT The finished roof with restored pendants and pinnacles.

BELOW Roofers strip the existing wood shingles in preparation for new work.

P R O G R A M H I G H L I G H T

The 1796 Watson Farm in Jamestown, Rhode Island, is a work-

ing farm that welcomes visitors with a self-guided tour and two miles of

trails through pastures and hayfields and along the shore of Narragansett

Bay. Herbalist Kristin Minto leads popular walking tours and workshops

about the use of medicinal herbs grown on the farm. Here, she shares some

of her experience with these traditional methods.

24 Historic New England Summer 2014

Pho

togr

aphy

by

Dav

e H

anse

n/N

ewpo

rt (

R.I.

) D

aily

New

s

Medicinal HERBS

25Summer 2014 Historic New England

Herbal medicine is one of the old-est forms of therapy practiced by mankind. On every conti-nent there is documentation

that indigenous people practiced some form of healing with plants. Healers experimented with plant materials and observed their effects. Remedies that worked were passed down orally from generation to generation; those that did not were forgotten. Each region developed a working knowledge of medicinal plants, trees, and shrubs in the area. This oral tradition is what we know today as folk medicine.

In modern times, pharmaceutical medi-cines dominate the healing profession, and people have lost touch with natural remedies. Nonetheless, using tonic herbs in our everyday lives can enhance a sense of well-being and even assist healing. Taking a lavender bath or drinking herbal tea will help relax us after a long day. Adding garlic or astragulus to a win-ter soup will help fight colds and flu. Medicinal herbs can boost the natural functions of our bodies by adding nutrients, vitamins, and heal-ing constituents to our diet.

Herbal medicine is not meant to replace the need for pharmaceuticals and physicians, but it can bring a sense of empowerment to managing health and reconnecting us to the natural world. Many herbs can be used daily as tonics; others are powerful and may interact with prescription drugs. It is important to use caution and to check with a physician before adding an unfamiliar remedy to your diet.

Drinking herbal tea is a safe and easy way to bring herbal healing into your life. Making tea to share with a friend or to sit and enjoy a relaxing moment is itself healing. What most people call teas are actually herbal infusions, different from the Camellia sinensis cultivated for centuries in Asia. Herbal teas are made from a variety of plants, using leaves, flowers, or fruit, either dried or fresh. The most com-mon kind of herbal tea is made from a table-spoon of plant matter steeped briefly in a cup or two of hot water. Drinks made from harder materials like roots and barks, called decoc-tions, need to simmer longer. Herbs in tea bags

as well as loose herbs in bulk can be found at local grocery stores. Some of my favorite infusions are ginger, which soothes digestive problems, chamomile when I cannot fall asleep, and raspberry leaf, which is used to balance hormones.

Tinctures, made with alcohol, glycerin, or vinegar, are stronger than herbal teas. Plant matter is first pickled in one of these liquids for three to six weeks, then strained out, leaving the liquid for medicinal use. Alcohol is most commonly used because it easily extracts healing components, resins, and volatile oils. Glycerin is a sweet liquid ideal for administering medicinal herbs to children and for gentler herbs like rose pet-als and lavender. Vinegar is great for those who wish to avoid alcohol. Herbs ingested through tincture are easily absorbed into the bloodstream via a few drops under the tongue. I use a dandelion tincture to detox-ify my liver, and one made with echinacea when I feel a cold coming on.

Another way to use plants is through herbal oils, made by steeping the plant matter in oil for four weeks. Oils may be used externally on abrasions, sore muscles, bruises, or skin irritations. The most com-mon media used are olive, sunflower, jojoba, almond, and sesame. (Mineral and other petroleum-based oils should be avoided.) Herbal oils can easily be made into salves by the addition of melted beeswax. Salves are a great way to combine herbs into easy-to-use medicines. A favorite of mine is a wound-healing salve made from comfrey, calendula, plantain, and St. John’s wort oils.

Discovering the wisdom of the plant world can be fascinating. Herbs are inex-pensive and readily available; you can buy them, grow them, and collect them in the wild. Each day, I find that taking a tincture or drinking herbal tea makes me happy and more present. Sometimes the simplest plea-sures are the most satisfying.

—Kristin MintoHerbalist

FACING PAGE Kristin Minto at work in the garden at Watson Farm. THIS PAGE, TOP

TO BOTTOM Nettles have been used to treat arthritis. Chamomile benefits the

nervous and digestive systems. Red clover relaxes the respiratory system.

To find out more about walking tours and other programs at Watson Farm, visit HistoricNewEngland.org.

Medicinal HERBS

26 Historic New England Summer 2014

H O U S E S T O R Y

The land on which Arnold House in Lincoln, Rhode Island, stands has gone by many names over the past

three hundred years. The Narragansett Indians referred to the general area as Quinsnicket, which means “place of stone houses” or “at my stone house.” The tribe established a path-way through Quinsnicket; English colonists expanded the way farther in 1683 and named it Great Road, the first highway in the future state of Rhode Island. During this period, the place was considered to be in the outer reaches of the town of Providence and hence was known as World’s End.

In 1685, Thomas Arnold, a settler who had emigrated from England in 1635, deeded fifty acres of land along

the Great Road to his son Eleazer. On that land in 1693, Eleazer and his wife, Eleanor, built an imposing two-and-a-half-story stone-ender with a pilastered chimney and settled in with at least nine of their ten children. All ten children survived to adulthood and produced many children of their own. Because so many Arnolds settled near their ancestral home, the area soon acquired the nickname Arnoldia.

Eleazer, being a landholder of considerable property, enjoyed wide-spread influence within the community. He served on the Providence Town Council between 1684 and 1686, was a deputy of the General Assembly eight times between 1686 and 1715, and Justice of the Peace from 1705 to 1709. His farm eventually grew

to 140 acres. In 1703, he permitted the Society of Friends, also known as Quakers, to build a meetinghouse on his land; five years later he formally deeded the land to them.

The Great Road was the only traveled road between Providence and the growing villages between the Moshassuck and much larger Blackstone rivers. Arnold House, strategically situated beside the road, offered a logical site for a tavern. In 1710, Eleazer applied for and was granted license for a “publick house,” and the property continued to be oper-ated as a tavern through 1725.

What’s in a Name?

ABOVE Built as a stone-ender in 1693, Eleazer

Arnold’s “Splendid Mansion” has been a

Historic New England property since 1918.

27Summer 2014 Historic New England

In 1731, the area around Arnold House had become sufficiently popu-lated to be incorporated as the town of Smithfield. The region’s farmland and rivers continued to attract settlers during the colonial era, and, with the advent of the Blackstone Canal, a rail-road, and textile mills from the early nineteenth century on, the population boomed.

The W. F. and F. C. Sayles Bleach-ery, founded in 1847 and later known as Sayles Finishing Plants, was one of the many factories serving the textile industry. It grew from bleaching one ton of cloth per day in 1848 to bleach-ing fifty tons per day in the 1880s, thus becoming the largest bleachery in the world. At its height, the mill complex contained thirty acres of floor space and employed three thousand workers. The mill village section of Smithfield became known as Saylesville. Along with laying out street after street with workers’ housing, the Sayles family was also deeply involved with the cul-tural life of the village and the nearby town of Pawtucket, building a church, a library, and a hospital for the com-

munity. They sponsored factory-wide outings every year and encouraged their workers to form clubs and interde-partmental sports teams. Men’s and women’s bowling leagues, lunchtime ice polo, a Boy Scout troop, a band, dances, and tennis tournaments were also sponsored by the company. The Sayles family attempted to maintain operations into the 1960s, but business diminished, and the factory eventu-ally closed along with so much of New England’s textile industry.

Even the town’s name changed to reflect its population and era. In 1871, the area around Arnold House separ-ated from Smithfield to incorporate as an independent township and, like many other newly incorporated towns across the country, took the name of Lincoln to honor the memory of the fallen president.

At Arnold House today, we cele-brate President Lincoln’s birthday with a party and open house. All year round, Arnold House welcomes the public to tours and programs. Events include the World’s End Walking Tour, which focuses on the history of the Saylesville

area, History and Herb Hikes, and Tales and Ales: Rhode Island. Every year, Arnold House and a half dozen other local historic sites collaborate on the Great Road Open House. Local groups who partner with us range from the Saylesville Meeting House to the Union Station Brewery in Providence. Lectures and talks cover topics like regional history and works by local authors. We also serve more than seven hundred schoolchildren who come to the property to participate in lively educational programs presented by our museum teachers. Thanks to engag-ing activities and widespread support, the stone house built by Eleazer and Eleanor Arnold more than three hun-dred years ago remains a vital presence in the community.

—Dan SantosRegional Site Manager

Learn more about this year’s events at Arnold House by visiting HistoricNewEngland.org or by calling 401-728-9696.

LEFT Saylesville Meeting House was built on Arnold’s

land in 1703. This building is still used by the Providence-

area Quaker congregation, making it one of the lon-

gest continually used houses of worship in the country.

ABOVE A postcard of the Sayles Bleachery, the largest

in the world in the 1880s.

28 Historic New England Summer 2014

S P O T L I G H T

Fanlights take center stage at the entrances to buildings, enjoying star status in the cast of architectural characters that attract our attention on the porch or portico of a Federal-style house. In wood, lead, and iron, either in semicircular or semi-elliptical form, fan-

lights carry the frills and flounces of neoclassical architecture but their origins and makers are not well documented.

One of the earliest examples was installed in 1724 at Marble Hill House, a Palladian villa outside London. In the densely urbanized cities of Dublin and London, where fanlights began to appear over the entrance doors of Georgian row houses by the 1730s, they functioned to light the houses’ narrow hallways.

The earliest examples were made of wood, with a spoke-like arrangement of glazing bars radiating from a central hub. Fanlights appear to have evolved as a variant of the wooden sash window, which came into widespread use in the early 1700s. In that scenario, the top row of panes in a window sash was separated into a smaller, separate sash with a radius or arched top. This wooden form remained the most common type of fanlight, either as a fixed

The Fanlight: Delicacy and Light

LEFT Semicircular fanlights, such as that at the

Asher Benjamin–designed Coleman-Hollister

House (1797) in Greenfield, Massachusetts, were

rare and needed a very tall first floor.

ABOVE Cast-lead ornaments of steins, hops,

wheat sheaves, and beer kegs were uncov-

ered under layers of paint on the fanlight of

a Connecticut tavern.

29Summer 2014 Historic New England

sash over a door or as an operable window, hinged at the bottom for ventilation.

The spokes of early wooden fanlights soon evolved into fanciful batwing, spiderweb, teardrop, heart, and Gothic-arched shapes, but it was by using more malleable, stronger, and lighter metal materials that craftsmen achieved the greatest virtuosity. Metal variants first appeared in the 1760s, when the opulent nature of ancient Roman classical architecture was pop-ularized in England by taste arbiter and royal architect, Robert Adam. Lead, tin, and iron, the only materials capable of carrying the most delicate lines of the ornate Adam or Federal style afforded a flexibility that wood could not match.

The most complex fanlights required the use of an iron armature within the wooden sash frame, onto which grooved rods of cast lead, or cames, could be soldered to support the glazing. An even more spectacularly delicate fanlight was made possible by using a cast-iron or wrought-iron armature, which allowed additional furbelows to be cast in place and pro-

vided smaller sectional openings. Cast-brass or cast-lead ornaments in the shape of sunbursts, stars, eagles, and floral motifs could be added to cover the solder joints.

By the 1780s, specialist manufac-turers were creating lead-iron, cast-iron, and composition fanlights for global export. At least four large suppliers of fanlights were operating in London, including Underwood, Bottomley and Hamble, the Eldorado Metal and Wrought Iron Sash Company, and George Kerr, “metal fan-light maker.”

This global market suggests that at least some of the elaborately detailed leaded fanlights that are the hallmark of the Federal style in the United States were probably imported. The strong manufacturing base in London and the ease with which fanlights could be packed for shipping likely discouraged local production. An 1815 advertise-ment in the Boston Gazette, for Josiah Vinton, Jr.’s store of “American Goods” included “Boston and Chelmsford Window Glass of all sizes, […] Coach Glasses and Fan Lights,” but this may refer to the glass only. The maker of the stein-decorated tavern fanlight (fac-ing page and at bottom right) is known to have worked in Connecticut; how many specialist fanlight makers might have practiced their craft there is not well understood.

Among the earliest American metal sash makers located in online searches was the firm of J. and R. Lamb of New York City, not estab-lished until the 1850s. In this country, where most houses were freestanding, the fanlight served not so much as the only way to get light into a narrow city entrance hall, but as the main attrac-tion on a grand façade, with full-length leaded sidelights completing the splen-did ensemble.

Elliptical fanlights better suited the lower interior ceiling heights of most houses, as a semicircular fanlight large enough to bridge the added width of sidelights at the entry would have

LEFT Fanlit entrances like this one with full

sidelights and a deep surround of rusticated

quoins, could only be accommodated in the

largest houses. ABOVE, TOP Cast-iron frames

enabled fanlights of great delicacy, such

as this example in a 1797 drawing of an

“Ionick Front” by Asher Benjamin. ABOVE,

BOTTOM Tavern-related details on a Con-

necticut fanlight.

necessitated higher ceilings inside. The majority of early fanlights in America date from the 1780s to the 1830s. Leaded fanlights would see a resur-gence in the Colonial Revival period starting in the late 1870s, with a strong market for both new and salvaged eighteenth-century examples.

—Sally ZimmermanSenior Preservation Services Manager

Y E S T E R D A Y ’ S H I S T O R Y

30 Historic New England Summer 2014

Orchard Walls, “Lost Days,” and Elections:

African American Stories at Casey Farm

31Summer 2014 Historic New England

At the turn of the nineteenth century, the legal status of men and women of African descent was com-

plicated. Emancipation of black New Englanders occurred gradually in the aftermath of the American Revolution. When the first Federal Census was taken in 1790, enslaved African Americans lived in the same communi-ties as free blacks. The percentage of black residents was small throughout the region but higher in coastal and agricultural communities where the demand for labor on farms and in the maritime trades was substantial. Boston, southern Rhode Island, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire, all had significant African American popula-tions, so it is reasonable to expect that there would have been an African American presence at Historic New England’s properties in these locations.

The c. 1750 Casey Farm, in Saunderstown, Rhode Island, is a large working farm in South County, which boasts a long agricultural heritage. The farm remained in one family until Historic New England acquired it in 1955, along with its rich collection of family papers. The Casey family’s account books provide insight into the lives of the farm’s black residents in the late eighteenth and early nine-teenth centuries, opening a window onto aspects of work and community activity among members of the free black population in the Narragansett Bay area.

Silas Casey (1734–1814) was one of the few members of the Casey fam-ily who lived and worked at the farm during his period of ownership. (Later generations used the farm as a sum-mer retreat and rented land to tenant

farmers.) Casey had been, among other things, a successful merchant and a member of the Rhode Island General Assembly while residing in Warwick, Rhode Island. According to bills of sale in the Casey family papers, Casey purchased at least three enslaved men, Wat, Ezekiel, and Moses, in the mid-1760s before moving to the farm two decades later.

During his subsequent years at the farm, Silas kept detailed books in which he recorded the names of the many men he employed to work the farm. Among them are a number whom Casey identified as “negroes” and one he called an “Indian.” By 1793, the first year in which he kept detailed accounts of activity at the farm, Rhode Island had approved a plan of gradual emancipation. The 1790 census for the state indicates there were a small number of enslaved people residing in Rhode Island, but the men associ-ated with Casey Farm are identified as “other free persons” with their own households. The fates of Wat, Ezekiel, and Moses are not known; by the time

Silas Casey started his farm accounts, he was paying wages to the black laborers on his farm.

Thanks to Casey’s account books, we are able to uncover a few details about some of the free African Americans at his farm that allow us to see deeper into their lives beyond the work they did. Cuff Gardner was among the most regularly employed at Casey Farm, appearing in the account books for fifteen years. Most of the men who worked for Silas Casey would work for a few months of the year, some a few weeks, and others a few days, but there were also names that appear regularly. Gardner worked a few days here and there, but also for at least two periods spanning six or seven months. He performed a variety of tasks, including killing and butchering hogs, carting wood, setting apple trees and trimming the orchard, and building the orchard wall. He was paid in cash as well as with salt, corn, and potatoes. Casey recorded the absences of some of his laborers, most likely those whom he had hired for a period longer than a few days or weeks. In 1804, he noted Gardner’s “lost days,” which included attending Negro Election and Negro Town Meeting, and a half day lost to being unwell.

Casey made numerous refer-ences to days lost by his men to “Negro Election,” a significant tradi-tion for African Americans in New England. Election Day was among the few holidays observed by the Puritans, although the tradition came to be observed throughout the region for several generations. On this day, white voters elected local officials (in Massachusetts, for example, vot-ers selected members of the General Court) or installed and celebrated them with orations and feasts. Black New Englanders responded with their own holiday, in which they elected their own leaders and held their own cel-ebrations. Black governors served as community leaders and had judicial

FACING PAGE This page of Silas Casey’s 1793–1813 account book

records a contract with Henry Carr and the activities of Cuff Gardner,

including his attendance at Negro Town Meeting and Negro Election.

BELOW Silas Casey (1734–1814).

32 Historic New England Summer 2014

autonomy at the farm by residing in a separate house, clearly Casey kept close watch not just on him but on all the men working on the farm.

The economic development of New England in the early years of the United States depended, in part, on the labor of people of color who worked as farm hands, as domestic servants, in the maritime trades, and many other types of work. Yet, despite their con-tributions, their stories, and those of others of lower economic status, have remained largely hidden because of the lack of documentary evidence. Financial records like Casey’s are important resources that can be mined for information beyond their original intent as records of production and consumption. By reading deeper, we see glimpses of the personal time and social lives of people who have been long overlooked. These documents provide some of the best evidence of how black New Englanders built their own communities and preserved their traditions despite the obstacles.

—Jennifer PustzMuseum Historian

ABOVE Casey Farm boasts a large network of stone walls to corral livestock

and keep out predators. The walls have likely been rebuilt over the years, but

were probably originally built by the African American men Silas Casey employed.

BELOW Detail of the orchard wall at Casey Farm.

African traditions. Casey’s account books also indicate that in addition to time off, he sometimes gave his men money to spend during the festivities.

In addition to documenting the participation of his workers in local African American celebrations, Silas Casey’s account book reveals that he also entered into agreements with two men of color who worked as tenant farmers: Henry Niles (whom Casey

identifies as an Indian) and Henry Carr (a free African American). The men lived in a small house on the farm rent-free in return for working for Casey a specific number of days per week. As he did with other men work-ing on the farm, Casey tracked the days Carr “lost” in order to take care of his own business: going to town meeting, training, attending to Widow Smith’s burial, and taking his pig to Newport. So while Carr had a certain amount of