Historic New England Summer 2009

-

Upload

historic-new-england -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Historic New England Summer 2009

HistoricNEW ENGLAND

“A FEW DESIRABLEBOARDERS SOLICITED”SUMMER 2009SUMMER 2009

F R O M T H E P R E S I D E N T

In times of uncertainty, we turn to history.Whether to understand the economy, legalprecedents, or international crises, whenconfronting the issues of the day we auto-matically look to the past for perspective.Where do we find the information neededto guide our decisions today? In documents,artifacts, images, and recorded evidencethat is preserved in museums and archivessuch as those at Historic New England. Inthis issue we recognize how constant historyis as an influence in our lives. From summertourists traveling to Wiscasset to modernhouses being erected in Lincoln, the distantpast and recent past are present to us.History is as near as our own kitchens,which have evolved from the early hearthkitchens used in New England three hundredyears ago.

In times of uncertainty, the consistentpresence of the past is a reminder of chal-lenges faced before, and of the ingenuity andflexibility of New Englanders. We recognizehow important it is to preserve our heritageand ensure that the traditions, practices,challenges, and accomplishments on whichour society is based are available as historicresources for us and future generations.

In difficult times, we turn to history.Our thanks go to all mem-bers and friends of His-toric New England fortheir dedication to pre-serving New England her-itage through support ofour mission and programs.

—Carl R. Nold

SPOTLIGHT 1A Festive Evening

PRESERVATION 8Preservation Pendulum

MAKING FUN OF HISTORY 10Postcards

KITCHEN STORIES 13Preserving the Harvest

LANDSCAPE 18Garden Planning for a Country Estate

OPEN HOUSE 22Old House Myths

ACQUISITIONS 2628 Flavors

“A Few Desirable Boarders Solicited” 2

Modern Neighbors 14

Except where noted, all historic photographs and ephemera are from Historic New England’s Library and Archives.

The award-winning Historic New England magazine is a benefit of membership.To join, please visit

www.HistoricNewEngland.org

HistoricNEW ENGLAND

Summer 2009Vol. 9, No.1

Historic New England141 Cambridge StreetBoston MA 02114-2702(617) 227-3956

HISTORIC NEW ENGLAND magazine is a benefit of membership.To join Historic New England, please visit our website, HistoricNewEngland.org or call (617) 227-3956. Comments? Please call NancyCurtis, editor. Historic New England is presented by the Society for thePreservation of New England Antiquities. It is funded in part by theMassachusetts Cultural Council.

Executive Editor Editor DesignDiane Viera Nancy Curtis DeFrancis Carbone

COVER The upper level of the piazza at Castle Tucker, Wiscasset, Maine,overlooks the Sheepscot River. Photo by Aaron Usher.

Dav

id C

arm

ack

1Summer 2009 Historic New England

S P O T L I G H T

Pho

togr

aphs

by

Mic

hael

Dw

yerearly three hundred guests gathered at the Four Seasons Hotel

in Boston on January 9 for the fourth Historic New EnglandGala, which raised $201,000 to support our education and public outreach programs.

TOP Chairman of the Board, William C.S. Hicks. MIDDLE, LEFT

Guest auctioneer Karen Keane of Skinner, Inc., responds to

lively bidding on Red Sox box seats. MIDDLE RIGHT Susan Sloan,

Kem Widmer, Betsy Garrett Widmer, and Julie Cox. BELOW

LEFT Lead Corporate Sponsor William Vareika with Gala Co-

A Festive Evening

N

Chairs Kristin Servison and Anne Kilguss, and President and

CEO Carl R.Nold. BELOW CENTER Honorary Chairs Leigh Keno,

and Emily and Leslie Keno. BELOW RIGHT Honorary Chairs

Peter and Carolyn Lynch.

2 Historic New England Summer 2009

A Few Desirable

Boarders Solicited

Aar

on

Ush

er

“Several summers ago we were sitting at an open window, looking out upon one of

the pleasant parks of New York, vainly endeavoring to detect some perceptible

motion among the tall maples whose leaves had hung ever since morning as immov-

able as foliage cut in cold stone…we fell into a serious discussion of the merits of

ocean and shore, and resolved to get out of the suffocating city without delay. But

where should we go?… And so…Maine was talked of.” —B. F. DeCosta, Rambles

in Mount Desert: With Sketches of Travel on the New-England Coast, from the Isles

of Shoals to the Grand Menan, 1871

3Summer 2009 Historic New England

and experiments with steam-propelled watercraft. In 1885,Tucker wrote to his oldest daughter, Mame, “Times are hardwith me, everything going out and nothing coming in. I havelost a good deal the past year and my expenses have beenheavy. I have no care for my future for myself but I shouldfeel happy if I knew my family were self sustaining.” Threeyears later, he reassured her not to worry about family affairsand that “we are not going to open a Boarding House.” Hiswife, Mollie, however, recognized that the house itself hadthe potential to bring in money. In February 1890, she wroteto Mame, “I have already written to Foster about Artistboarders for the Summer & shall follow it up with adver-tisements in the papers to the same end & purpose. I shall try

The allure of coastal Maine

for summers at the Castle

seeking respite amid the cool ocean breezes of coastal NewEngland. Vacationers had several options when selecting ahome away from home. Many chose to stay at the growingnumber of inns, hotels, and resorts that dotted the coast.Travelers with smaller budgets or those who sought out“authentic” rural experiences with access to fresh food oftenboarded with farm families who opened their homes totourists. Taking in summer boarders was seen as a respectableway for families, particularly women, to earn extra money.

The need for additional income motivated the Tuckers ofWiscasset, Maine, to open their home, Castle Tucker, to sum-mer boarders. By the mid-1880s, the family finances werestrained, partly because of the region’s sluggish economy andpartly because of Captain Tucker’s unprofitable investments

n the days before air conditioning,

those who could afford to fled the cities

during the summer, many of themI

FACING PAGE The east façade of Castle Tucker, Wiscasset, Maine.

Captain Tucker added the dramatic two-story piazza to the 1807

house after he bought the property in 1858. ABOVE LEFT Mollie

Tucker, with Patty, Will, and Mame. ABOVE RIGHT The Italianate

entry with exuberant console brackets (also added by Captain

Tucker) opens out to greet the visitor.

Aar

on

Ush

er

4 Historic New England Summer 2009

to fill the house, & work every moment myself to tide over another year, taxes are due, also, things are in a messindeed, & yet there is property enough to keep us in pru-dence without hard work if well managed.” During the nextten years, she and two of the adult children, Jane and Will,endeavored to wrest a living from their “old-fashioned coun-try mansion.”

The Tuckers believed that Castle Tucker with its dra-matic piazza would appeal to vacationers. Will thought,“The rooms and other surroundings are far better than anordinary place we all know.” The Tuckers sought boardersby placing advertisements in Boston, New York, and NewHaven newspapers. Jane and Will worked hard to drum upbusiness and interviewed prospective boarders. Room pricesranged from $7 to $30 per week. The most desirable andexpensive rooms were the two large chambers above the bil-liard room and the parlor. It is unclear where the familystayed in the summer, since they appear to have been willingto rent any and every room they could. Mollie wrote toMame that they were “getting things up into the attic whereJane proposes to sleep in a hammock this Summer if thingsare so favorable for us as to insure a full house. I shall sleepin the Bath room on an Iron bedstead taking out the stove

there, it will make a very comfortable room for me I think.”Once the family decided to open the house to tourists,

they worked in earnest to prepare. Family letters suggest aflurry of activity as Mollie, Will, and Jane cleaned out closetsand bureaus, moved furniture, and spruced up rooms withpaint and paper. Mollie described the preparations to Mamein June 1890: “We have been painting the Billiard room floor& that of the Dining Room & up in the 3rd story & Jane didit all her own self…now we have been papering the Studio &the Dirty-clothes Closet has all the shelves out of it & makesa cute little room for a single bed room, nicely papered &painted they will make good rooms enough, ways & meansare keeping us so busy that we bear our suspense quite well.”Captain Tucker cleaned up his pilot boat in hopes of rentingit to visitors.

The Tuckers sought boarders of a “better” class, buttheir guests also had to be open to more rustic conditionsthan they may have been used to. Mollie received the fol-lowing inquiry from a prospective boarder in 1894: “Haveyou piazza or grounds, bath room, with hot & cold water, &water closet? Is the plumbing modern & good?” AlthoughMollie’s response is lost, it clearly did not meet her daughterJane’s approval: “Next time any one writes about the place

ABOVE LEFT The house did not have running water, but each cham-

ber had a handsome toilet service and a washstand. ABOVE RIGHT A

piazza was high on the list of amenities desired by city dwellers

seeking a summer refuge. Castle Tucker’s piazza has two levels

(formerly shaded by a large elm tree) with windows to admit

cool breezes. The lower level was a welcoming room, filled with

Aar

on

Ush

er

5Summer 2009 Historic New England

don’t do such a fool thing as to tell them you have no plumb-ing, you lead them to think there is no decent water closetand that they must probably go out doors for a miserableplace such as you generally find in the country. Just tell themyou have no bath room when they have to know about it butthe least said on that subject the better.” Family correspon-dence refers to a water closet, and they likely were able topump water from the cistern for use in the kitchen and laun-dry, but bathroom facilities were limited in size and sophisti-cation. While farms and other rural homes that would betheir competition likely had no better amenities, by the1890s, the city dwellers that were the Tuckers’ preferredclientele were used to higher levels of comfort. Most boardersanticipated some sacrifices, as suggested by an 1893 article inHarper’s Bazaar, “Many a woman, looking at her comfort-able city home, with its high ceilings, pleasant situation, andample facilities for bathing, sighs at the thought of living ina trunk in tiny cramped chambers, with scant appliances forthe toilet and greatly restricted conveniences, during theheated term.”

Despite their less-than-modern facilities, the Tuckersbelieved their home had other advantages, as Jane remindedher mother in the rest of her letter, “as for a piazza you

should have told her this was better than any piazza she eversaw for it could be all thrown open like a piazza on pleasantdays and when it was stormy made the most delightful sittingroom imaginable. Don’t tell them too plain facts, dress themup or you will never get any one down there. What they dohave about the house more than makes up for the lack of themodern conveniences that they would not find.” Indeed, theTuckers’ hospitality may have made up for rustic amenities.Photographs from the era capture a game of lawn tennis andgroups of people relaxing in the piazza. One family lettermentions an entertainment that ended in a dance.

Running a boarding house required a tremendousamount of work for the Tuckers and any help they were ableto hire. Mollie appears to have shouldered the majority of theburden, but Jane worked during most of the boarding housesummers. Even before making the decision to take in board-ers, Mollie was aware that domestic help would be requiredand wrote to Mame in December 1889, “I keep Maggiewhich is an extravagance I admit all around but if I takeboarders or lodgers next summer she is the best girl possiblefor me & to keep her for this purpose I must make this sac-rifice not only of her wages, which I can ill afford, but thefirewood & kerosene is a big item with the food also.”

couches, rocking chairs, and other comfortable seating, where the

Tuckers and their guests could gather and relax. ABOVE The spa-

cious north chamber includes a seating area. An adjoining smaller

bedroom made it suitable as a suite for a family. Some guests pre-

ferred rooms on the south side of the house because they offered

views of the water.

Aar

on

Ush

er

Aar

on

Ush

er

6 Historic New England Summer 2009

ABOVE LEFT Photographs taken in 1894 show guests with Captain

Tucker in the lower piazza and a game of billiards.

ABOVE RIGHT Parlor games and music likely provided entertainment

during rainy days and evenings. The lower piazza may be glimpsed

through the doorway.

Maggie stayed until just before the start of the first boardingseason and was followed by a series of girls and women whoworked behind the scenes to cook, feed, serve, and clean upafter a houseful of guests. Running a summer boarding housecreated a delicate social situation for the lady of the house.As a woman whose social standing, regardless of any dimin-ished economic position, made her mistress of servants, shenow found herself playing the blurred role of a hostess whowas obliged to cater to the boarders’ demands.

Like most families who opened their homes to summerpeople, the Tuckers encountered a range of personalities,some of whom they enjoyed and who returned for multiplesummers, and others whom they considered quite difficult.The Tuckers initially wished to attract artists, but it is unclearexactly who ultimately took advantage of their home andhospitality. Two other Tucker children, Richard and Patty,advised against taking friends and relations because theyoften demanded more but expected to pay less. Mollie tookthem in anyway, most likely to fill the house.

Boarders could also be particular about meals and othercreature comforts. Mr. Woodman, of Portland, Maine, whospent two summers at Castle Tucker, described his family’spreferences, “As to diet, our tastes are extremely simple, pas-

try and cake Mrs. Woodman does not care for herself anddoes not permit the children to eat. Good bread (withoutshortening of any kind) milk, butter, oat meal, cracked wheat,etc. are the important things, and the main staples of the chil-dren’s diet for all three meals, though at dinner time they eata small amount of such meat as may be served and vegetables.”

The Tuckers’ experiences with boarders seem fairly typical.The summer boarding situation served as a popular topic forhumor in the 1890s. Stereotypical boarders such as the elderlylady traveling with her unmarried daughter, the bachelor whobelieves that “‘All children ought to be kept in barrels until they are twelve years old,’” and the “boss of the boardinghouse,” who functions as the conduit for complaints to thelandlady, were described in the popular press. Mollie describedher feelings about her summer residents to Mame in August1890: “You ask if I like or dislike boarders… I assure you, Imuch prefer strangers to acquaintances but the Babsons havebeen very nice boarders. Mrs. Grant is still here, her oldest sonThomas came yesterday for a week’s stay, & Mrs. Babson &daughter left us yesterday. Last Sunday the house was full.Today we have only four people.”

Although family correspondence suggests that theTuckers managed to draw a number of guests to room and

Aar

on

Ush

er

7Summer 2009 Historic New England

board in their home, they were not able to earn a significantprofit. In July 1891, Will wrote to Mollie that “you are over-crowded and rooming people outside. Well that looks like agood season I should think.” However, when all was said anddone, success did not translate into financial stability. InNovember of the same year, Will wrote to his mother, “Doyou really come out so little ahead as you say? Jane said shethought you would be at least $250 or $300 ahead and I feltyou had done well anyway.”

The family continued to let rooms to boarders throughthe 1890s, although as the decade wore on, the ventureseemed to run its course. Ultimately, running Castle Tucker asa boarding house was too much work for too little income.After Captain Tucker’s death in 1895, Richard served asexecutor of his father’s estate. In 1898, he expressed frustra-tion with the boarding scheme and forbade family membersfrom taking in boarders without his consent. Although thereis evidence that a few lodgers stayed at the house in the yearsimmediately following, by 1900 it appears that “spaciousrooms” were no longer let in this particular country mansion.

The end of the boarding house era did not end CastleTucker’s relationship with Maine’s tourist industry. Between1924 and 1950, Jane Tucker opened the home to vacationers

once again, this time as a lodging house, where visitors couldget a room for the night but no meals. An advertisement fora local tea room printed in the State of Maine Cook Book,edited by Jane Tucker for the state’s Democratic Party, rec-ommended to patrons, “After a Delicious Dinner AtMontsweag Farm Tea Room, ride on for about 10 minutes,to—castle tucker For a cool, comfortable lodging in thisquaint old house.” Starting in the 1970s, her niece, JaneStanden Tucker, also welcomed visitors to her family home,not for an overnight stay but for an hour’s guided tour and aglimpse of a world gone by. For the better part of a century,welcoming guests to Castle Tucker allowed the Tucker familyand later, Historic New England, to preserve a building andmemories of a lifestyle.

—Jennifer PustzMuseum Historian

ABOVE LEFT Castle Tucker’s grounds and location near the water

allowed summer boarders to partake in the healthy outdoor activ-

ities that were an important part of summer vacationing.

ABOVE RIGHT The Tuckers advertised the billiard room as one of the

amusements available to guests.

Dav

id B

ohl

Castle Tucker is open Wednesday through Sunday from June 3 throughOctober 15, 11 am to 5 pm, tours on the hour, last tour at 4 pm.

8 Historic New England Summer 2009

ver since its founding in 1910,Historic New England’s workhas been guided by a philoso-phy of preservation. Our goal

has always been to keep for future gen-erations the significant features at anysite. Yet, defining what is significant issubjective. One person may think thata window installed in the 1870s is sig-nificant, while someone else mightvalue more the window that precededit. Looking back over the years, we cansee that our approach has fluctuatedwith the prevailing wisdom of the time,swinging like a pendulum betweenrestoration and strict conservation.

The preservation pendulum’s posi-tion begins to the right of center withour founder, William Sumner Apple-ton, during the early decades of the

twentieth century. The common pres-ervation methodology of his day wasto restore historic houses—to takethem back to their “original” appear-ance by removing features added afterthe house was first constructed.Appleton’s approach, more conserva-tive than that of his peers in the field,tried to respect later alterations.Indeed, he was criticized for his conser-vative philosophy. Regarding his deci-sion to preserve later additions to the1664 Jackson House in Portsmouth,New Hampshire, he responded, “evenwere this new wall built of old stock, itwould still remain mine, and I muchprefer the interesting old alterationsmade by some long dead generation ofJacksons.” On occasion, however,Appleton did remove later modifica-

P R E S E R V A T I O N

Etions to restore older features if he feltthe evidence was sufficiently com-pelling. The evidence for the originalseventeenth-century window at theJackson House was so clear that hedecided to replicate it in order torestore the principal façade.

After Appleton’s death, the preser-vation pendulum in the 1940s and1950s swung dramatically towardrestoration. This was inspired in partby the popularity of Colonial Williams-burg’s reconstructed Colonial capitolas well as by a widespread preference

Preservation Pendulum

ABOVE In the mid-nineteenth century, the

Caseys added a Greek Revival veranda as a

place to relax. In this c.1875 view, the original

columns have been replaced by rustic peeled-

log posts. INSET The farmhouse today.

the 1796 Otis House, was refurbishedto reflect the appearance of a mansionbelonging to a prominent family dur-ing the Federal era. Thirty years later,as a result of changing visitor interests,we reinstalled two rooms to allow us torepresent the lives of a female physi-cian and a middle-class boarder wholived there in the 1830s and 1850s.

Preservation and reversibility arethe keys to Historic New England’sphilosophy today. It is likely that ourapproach will always remain faithfulto the available historical evidence—conservative in protecting historic features and flexible in interpretinghouses to the public. As Appleton said,“What is left today can be changedtomorrow whereas what is removedtoday can perhaps never be put back.”

—Ben HaavikTeam Leader, Property Care

9Summer 2009 Historic New England

for eighteenth-century architecture anddesign. Thus, in keeping with currentpractices, Historic New Englandundertook to restore the house at thec.1750 Casey Farm in Saunderstown,Rhode Island, removing the nine-teenth-century dormer windows andporch so as to return the building to itsoriginal appearance. Today, HistoricNew England staff look back at thisrestoration with some regret over theloss of details that show alterationsover time as the Casey family modifiedthe house to suit their changing needsand taste.

In the 1960s, the pendulum atHistoric New England swung back,past Appleton, to a very conservativephilosophy, influenced by the latestthinking at the National Park Service,which advocated leaving propertiesexactly as they were when acquired.The only way to prevent the loss offabric, such as had occurred at CaseyFarm, was to preserve, not restore.When Historic New England acquiredthe c.1740 Codman Estate in Lincoln,Massachusetts, in 1969, conservativephilosophy dictated that the architec-tural details be preserved exactly as

they came to us. For example, the ele-vator that the family had installed atthe back of the house in the 1950s wasleft in place despite the fact that it com-promised the exterior and darkenedthe hall. Our guiding philosophy dic-tates that regardless of how we inter-pret the house to the public, we mustleave all the evidence intact. At present,the tour narrative focuses on the earlytwentieth century, when the last twogenerations of the family were usingthe estate as a country house, but if infuture staff chooses to portray life atthe house in the 1960s, the evidence ofthat era survives.

While Historic New England’spreservation philosophy toward archi-tectural fabric is conservative, it is flex-ible toward the interior, so long as anychanges are reversible. A committee ofcuratorial, research, interpretative, andpreservation staff analyzes preserva-tion and presentation issues and care-fully considers the best approach. Wewould never remove a later mantel-piece from a room, but might changethe wall treatment, carpet, and furnish-ings to suit the interpretive concept. Inthe early 1970s, our flagship museum,

Dav

id B

ohl

Dav

id C

arm

ack

BOTTOM LEFT The ell chamber during the

1970s at the Otis House, furnished to reflect

the Federal era. BOTTOM The same room

today reinterpreted as a boarding house bed-

room in the 1850s.

10 Historic New England Summer 2009

Postcards can depict all sorts of subjects, fromlandmarks to famous people to comic pictures.

Some postcards show recent events. Can youidentify the events pictured here, each of whichhad a major impact on life in New England?

M A K I N G F U N O F H I S T O R Y

�

1860s Postcards first pro-duced in Europe.

1873 First blank postcardsdistributed by theU.S. Postal Service.

1893 First picture postcards inAmerica distributed at theWorld’s ColumbianExposition in Chicago.

Late nineteenth century Queen Victoria has herown postcard collection.

Can you guess what this is?

Postcards

do you know �

Let’s have fun with postcards.

Let’s look at examplesfrom Historic NewEngland’s large collectionof postcards. Collectingpostcards used to be a

popular hobby for bothchildren and adults. Do you like to collect

things? What can these postcards tell us about lifenearly a century ago?

�

1

2

Answers appear on the facing page.

11Summer 2009 Historic New England

1. This postcard shows American soldiers training forcombat in World War I. In 1918, a soldier stationed inBaltimore sent this card to Mrs. E.L. Sharpe onTremont Street in Boston. On the back he wrote,“This is the same drill we get [every] day for 2 hours.Best regards to all from Wm. Ford.”

2. This postcard shows the devastation caused by theGreat Hurricane of 1938. On September 21, this vio-lent storm took New England by surprise, killing sev-eral hundred people and causing extensive damagethroughout the region. Flood waters rose to thirteenfeet in downtown Providence, and wind destroyedcountless homes in Connecticut, Rhode Island, andMassachusetts.

1902Kodak introduces a camerawith which you can makeyour ownpostcards.

1905 More than one millionpostcards pass through theBaltimore Post Office dur-ing the Christmas season.

1909 The Post Card Union ofAmerica, one of severalpopular collectors’ clubs,has 10,000 members.

��puzzle

1920sThe telephone begins tocompete with postcards asa means of communication.

Here are some postcards from the early twentiethcentury. Unscramble the words below, then matchthem to the subjects of the postcards.

Answers can befound on page 17.

1. R DA L E S E

2. E N W N V T N I I N O E

3. TA E G O C T

4. O N K G N I S O M

5. RY R F U D R I E F N

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

E

C

B

A

D

12 Historic New England Summer 2009

M A K I N G F U N O F H I S T O R Y

Design your ownpostcards

MaterialsSeveral sheets of 81/2" x 11" heavy cardstockRulerPencilScissors Scrap paperFelt-tipped markers, crayons, or colored pencils

Instructions1. Using a pencil and ruler, divide the cardstock sheets inhalf and then in quarters so that each section measures5 1/4” x 4 1/4”. Cut along the lines to make your postcards.2. Make a list of your favorite places in your com-munity. These could include buildings like yourhouse, school, town hall, church, or post office. Youcan also include landscapes like parks, beaches, athleticfields, even your own yard or garden. Make practice sketchesof these places on scrap paper.3. When you are satisfied with your sketch, draw it on thepostcard and color it. Write the title of your subject on theface of the card, just like a real postcard. Color the picturewith markers, crayons, or colored pencils. 4. You can display your postcard collection on a shelf, or inan album, as people often did one hundred years ago. To senda postcard in the mail, turn it over and draw a vertical linedown the center. Write a message on the left-hand side and the mailing address on the right. Put a postcard stamp on theupper right-hand corner before mailing it.

—Amy Peters Clark, Education Program Manager

Casey the Clock would love to receive one of your post-cards! Send it to Casey the Clock, c/o Historic New England,141 Cambridge Street, Boston, MA 02114. Be sure to putyour name and return address on the card so we can enteryour card into a drawing to receive your own Historic NewEngland coloring book.

Famous landmarks andbeautiful landscapes,whether vacation des-

tinations or hometowns,have always been popular subjects forpostcards. Create a set of postcards ofyour own favorite places, and send themto your friends or keep them in an album.

13Summer 2009 Historic New England

K I T C H E N S T O R I E S

Preservingthe Harvest

oday, most Americanscannot imagine life beforethe widespread availabilityof well-stocked grocery

shelves, plentiful canned and frozenfoods, and home refrigerators andfreezers. Before the advent of theseconveniences, women not only cookeddaily meals but also had the responsi-bility for preserving fresh food for lateruse. At harvest time, women devotedlong hours to canning and pickling;they stored foods like carrots and pota-toes in cool root cellars, and sold thosethings that would not keep.

Many of the cellars and attics atHistoric New England’s house muse-ums are filled with canning jars andoversized kettles. At the CodmanEstate in Lincoln, Massachusetts, jarsof tomatoes and pears preserved bythe family’s cook are still stored in thebasement. At the Spencer-Peirce-LittleFarm in Newbury, Massachusetts,Amelia Little, a trained home econo-mist, took a class at Simmons College

in 1913 on “Properly Prepared Food,”and learned the chemistry of foodpreservation. Her copy of CannedFruit, Preserves, and Jellies: HouseholdMethods of Preparation, a Farmer’sBulletin written by Maria Parloa forthe U.S. Department of Agriculture in1904, was clearly well used. She knewhow important it was to follow canningprocedures precisely to prevent spoilageor the growth of dangerous bacteria.

In the late 1890s, Jane Tucker andher mother, Mollie, at Castle Tucker inWiscasset, Maine (see pages 2–7),planned to sell their preserves. Theapple market was flooded, but theyhoped for success with preserved applepie filling. In early 1897, Mollie andJane had finished forty-two dozenquarts of “canned apple pie” with twodozen more on the way. “If we onlysucceed…we shall have a business forthe winters to come and a chance live,”Mollie wrote to another daughter. Ayear later Mollie reported, “I have notsold a jar of apples in Wiscasset…

T

Year of the Kitchen programsThe exhibition America’s Kitchens is on viewat the New Hampshire Historical Society,Concord, New Hampshire, from June 11through January 17, 2010.

Three workshops on canning techniques willbe offered at Cogswell’s Grant in Essex,Massachusetts, by Caroline Craig, whocooked for the owners, Mr. and Mrs. BertramK. Little, for more than thirty years.

For information on these and other Year ofthe Kitchen programs and to order the bookAmerica’s Kitchens, a profusely illustratedsurvey of kitchens across the country, visitwww.AmericasKitchens.org.

Everybody is hard up like ourselves.”Jane sold a few bottles in Boston, butgave more away than she could sell. As Mollie observed, it takes time andexperience to work the market.

—Nancy CarlisleCurator

Dav

id B

ohl

RIGHT Canned goods stored in the

basement of the Codman Estate,

Lincoln, Massachusetts.

Historic New England Summer 200914

Y E S T E R D A Y

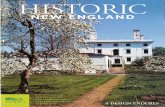

n the spring of 1938, celebrated German architect WalterGropius began construction on his family home over-looking the apple orchard belonging to wealthy philan-thropist Helen Storrow. Gropius had recently been

brought over from Europe to reinvigorate Harvard’sGraduate School of Design and was living in a small rentedhouse in Lincoln, Massachusetts, around the corner from theStorrow mansion. At the suggestion of Boston architectHenry Shepley, a mutual acquaintance, Mrs. Storrow offeredGropius an opportunity to build a house of his own designon a piece of her land. According to Gropius’s wife, Ise,“Mrs. Storrow agreed because one of her principles was thata newly arrived immigrant should always be given a chance toshow what he could do best. If it was good it would take root,if it wasn’t it would disappear. But it had to be tried out.”

Mrs. Storrow allowed Gropius to carve out a site on herestate and build a house that he would rent from her annu-ally at ten percent of the building cost, with an option to buyat a later date. Gropius was grateful for the offer, fearing thatit would be nearly impossible to get a bank loan for the flat-

roofed house he wanted to build. After reviewing theirfinances, the Gropiuses decided to spend no more than$20,000 on their new home.

Before the Gropiuses’ house was even completed, Mrs.Storrow permitted three other forward-thinking Harvardprofessors to build houses on her property with the samearrangement. In January of 1939, Woods End Road was laidout on paper, and soon after, construction began on the threeadditional houses, all of which were of modern design. Allfour families were firm believers in the principles of moderndesign and saw their houses as a means of demonstrating thestrengths of a modern approach to architecture. Yet, as eachfamily had its own ideas about the best way to go about this,each house had a personality of its own.

I

ABOVE A gathering at the Breuer House in 1940. Ise Gropius is

seated in front of the fireplace, with Walter Gropius at lower left.

“Your type of architecture is somewhat startling but I shall

look forward with great interest to having you build a

house on this place…”

—Helen Storrow, writing to

Walter Gropius, 1937

ModernNeighbors

Dav

id C

arm

ack

15Summer 2009 Historic New England

Gropius House�“When I built my first house in the U.S.A.—which was my own—I made it a point to absorbinto my own conception those features of theNew England architectural tradition that I foundstill alive and adequate. —Walter Gropius, Scopeof Total Architecture, 1955

In designing his home, Gropius studied the Colonialhouses of the region and borrowed features like thewhite wood exterior, fieldstone foundation, andpassive solar orientation. To these traditional NewEngland features he introduced “new” materialslike steel, glass block, and chrome, which up untilthat point had been used mostly in industrial appli-cations. Gropius hoped this house would serve as acalling card for his private architectural practice,showing how the New England house could adaptto the exciting technology that the twentieth centuryhad to offer. The house was completed just beforethe Great Hurricane of 1938, after which many inLincoln were surprised to see Gropius’s “startling”house still standing.

�Breuer house“Many try to explain the new architecture as aresult of new techniques, new materials. I believethey are wrong. Stone and wood are as stimulat-ing to the new architectural vision as concrete andglass.” —Marcel Breuer in House and Garden,April 1940

The architect Marcel Breuer arrived in Boston afew months after Gropius in 1937. He had beenGropius’s student and, later, a colleague at theBauhaus, the design school in Germany foundedand led by Gropius. After accepting an academicappointment at Harvard, he designed for himselfa bachelor’s home on Woods End Road. WhereGropius used industrial materials, Breuer celebratedthe colors and textures of materials found innature. The two-story living room is dominatedby a fieldstone fireplace wall, which has a gentlecurve that softens the room’s interior. Originally,the rear wall and staircase were of naturalunpainted wood in a warm honey color.

ABOVE Gropius House in 1939. Its shape recalls the rectangular New

England farmhouse, but its orientation, like all the modern houses on

Woods End Road, was away from the road to take advantage of sweeping

views to the south and west. BELOW Breuer designed a house for himself of

just over one thousand square feet with one bedroom and a small maid’s

quarters. It was enlarged substantially by later owners.

Historic New England Summer 200916

�Ford house“The new residential architecture…bases its plansupon the organic life of the family to behoused…Thus human needs come first, which letsthe house grow from the inside outwardly toexpress the life within.” —James and KatherineFord, The Modern House in America, 1940

James Ford, a Harvard sociologist, had beenengaged in the field of housing for years. He andhis wife, Katherine, had written books recom-mending modern house design for its quality, econ-

Bogner house�“I considered it essential to demonstrate that modernarchitecture is not a luxury, but a means of givingmore to the owner for the same amount than wouldhave been expended on the traditional house.”—Walter Bogner, in House Beautiful, April 1941

Walter Bogner, a professor of architecture atHarvard, was determined to build his family home atthe lowest cost possible. All rooms were designed forstandard-sized lumber and used only wallboard,eliminating the expense of plaster walls. Bognerwanted to prove that it was possible to build a cus-tom home that served the needs of a modern familyat a modest price. The total construction cost for theBogner house was under $10,000, less than half ofwhat the Gropiuses spent.

Mrs. Bogner was a vocal supporter of her hus-band’s experimental house. “Housework in a mod-ern or old fashioned house?” she wrote in a 1941article in a local newspaper. “I’ve lived in both andthere is no comparison. The truly modern one isplanned with the minimizing of fatigue as the primeconsideration—both physical and mental fatigue.”

LEFT The Fords set their house on a small hill overlook-

ing a spring-fed pond. A sun screen made of redwood

boards on specially designed brackets runs the entire

length of the second story.

RIGHT Bogner felt that the modern house should pro-

vide uninterrupted views of the gardens and allow

ample light for growing plants indoors. The partially

enclosed upstairs “terrace garden” provided another

space to grow plants and was used for sunbathing.

FACING PAGE, BOTTOM Bogner entrance façade.

17Summer 2009 Historic New England

�Loud houseJohn Loud and his family hadno interest in modern architec-ture. Nonetheless, they ap-proached Mrs. Storrow, whoallowed them to build anotherhouse on Woods End Road withthe same terms she had given tothe Harvard professors. TheLouds engaged a local architectto design their home based on

an eighteenth-century house on Cape Cod. As the Louds’ sonlater recalled, “Such a home made one feel rightly situated…Theprivacy of solid walls was such a fundamental, nay, unquestionedgood, that to confuse the outdoors with the indoors through pic-ture windows as in modern houses was at the very least bewil-dering and, if we stopped to think about it, wrongheaded.”Gropius’s daughter recalled that the occupants of the other houseswere somewhat displeased by the appearance of the Louds’house, pointing out that its design was better suited to someoneliving a century and a half earlier who didn’t have the benefit ofmodern technology like central heating and large panes of glass.

The Louds, on the other hand, saw themselves asbeing “beset by chicken coops” and never appre-ciated what their modern neighbors wereattempting to create.

When Helen Storrow died in 1944, theWoods End Road residents purchased their houses from her estate. Although only the Bognerhouse is still owned by descendants of the origi-nal family, each of the current modern neighborstakes the role of steward quite seriously, preserv-ing their own home’s important features and theremarkable neighborhood that was built seventyyears ago as a way to revolutionize New Englanddomestic architecture.

—Peter GittlemanTeam Leader, Visitor Experience

Answers to puzzle on page 11.A./2. new invention B./1. leaders C./3. cottageD./5. furry friend E./4. no smoking

ABOVE Loud house

Dav

id C

arm

ack

omy, and efficiency, stating that it brought a “sociologicalconcern to the field of architecture.” Their house, which wasdesigned by Gropius and Breuer, conformed to the Fords’ideas about how a modern house, through precise planning,should accommodate the family’s personal needs and indi-vidual modes of living. Built around the specific requirementsand living patterns of the Fords and their twelve-year-olddaughter, the house included an isolated upstairs study withthree walls of bookshelves, a large living room with a fire-place for large-scale entertaining, and a floor plan designedto provide direct sunlight to every room.

Priv

ate

Co

llect

ion

Historic New England Summer 200918

L A N D S C A P E

oston businessman Alexander Cochrane and his family emigratedfrom Barr Head, Scotland, in 1849 when he was eight years old.At a youthful age he inherited the presidency of the chemical com-pany A. Cochrane & Son (which became Cochrane Chemical

Company), a position he retained until two years before his death. It was,however, his early business association with Alexander Graham Bell that ulti-mately made him one of the wealthiest men in New England, his stock shareseventually affording him a seat as a director of American Telephone andTelegraph. He married Mary Lynde Sullivan in 1869, and between 1870 and1882 they produced eight children, five of them daughters, “red-haired beau-ties” well-known on the Boston social scene.

Cochrane was a prominent Boston figure, serving on corporate boards aswell as those of charitable organizations. He was also a significant collector offine arts, making annual visits to the British Isles and the Continent thatincluded shipping back paintings and decorative arts to embellish the homesthe Cochranes created. At his death, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, whereCochrane served as a trustee between 1913 and 1919, received from his col-

BGarden Planning for a Country Estate

19Summer 2009 Historic New England

lection a Corot landscape, Grand Canal, Venice, (the muse-um’s first work by Renoir), and two Monet paintings, LesNymphias and Paysage d’eau.

First among their residences was a townhouse at 257Commonwealth Avenue, commissioned from the New Yorkfirm, McKim, Mead and White, and completed in 1887.Three years earlier, local architect William Ralph Emersonhad designed a large, handsome, shingle-style summer homefor them at Pride’s Crossing on the Massachusetts NorthShore, where they spent their summer months overlookingthe sea. This they alternated with spending summers abroad,including in Scotland, twice leasing a castle outside ofAberdeen, where they entertained family and friends.

It was not until 1905 that Cochrane purchased theMarla-Whipple house and fourteen acres in Hamilton,Massachusetts, called by the Cochranes The Farm, or TheHague. It does not appear that the family ever took up residence there for any significant period of time. Cochrane’s

granddaughter, Mary Margaret (Loring) Cushing,remembered that its greenhouse supplied figs and grapes for the Commonwealth Avenuehousehold.

Cochrane owned the property for eightyears before he called in Boston landscape archi-tect Arthur Asahel Shurtleff (known today asShurcliff, after he changed his last name in1930). Shurcliff trained as a mechanical engineer

FACING PAGE, TOP

Proposed rose garden

for Alexander Cochrane,

Hamilton, Massachusetts.

THIS PAGE, RIGHT Arthur

Shurcliff, c.1926.

FACING PAGE, BOTOM Alexander Cochrane.

THIS PAGE, LEFT The Cochranes’ Boston home.

ABOVE The Cochrane family.

Co

urte

sy M

assa

chus

etts

His

tori

cal

Soci

ety

Priv

ate

Co

llect

ion

Historic New England Summer 200920

side of the main structure, terminating in a turnaround infront of the stables. Irregular groupings of beech and oak treesloop about the greenhouse. Shurcliff proposed enclosing thearea inside the trees in a rectangular surround of wall andspruce hedge, with a perennial garden rimming its interior. Apergola was to serve as entrance to the greenhouse area. Healso suggested a second, square, walled perennial garden atthe far end of the house, with a garden shelter incorporatedinto one of the walls, and a circular water basin at its center,the entire design reflecting the Arts and Crafts elements hefavored at that time for small estates. Near the stables appearsa cutting garden, designated for roses.

The focal point for the newly created landscape, how-ever, was to be the Rose Garden, on the southwest side of the residence, located directly on Main Street. An undatedwatercolor presents a luxuriant bird’s-eye view of the pro-posed garden, the work of P.O. Palmstrom, not a delineatoremployed by Shurcliff on a regular basis, although Shurclifffrequently used elaborate aerial views to aid his clients inconceptualizing plans. The garden would be enclosed on thenorthwest and southeast by masonry walls and on the south-west and northeast by a wooden picket fence.

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After two moreyears at Harvard University, he went on to apprentice andthen work at the Olmsted firm in nearby Brookline, the pre-miere landscape design office in America at the time, beforesetting up his own practice in 1904. During that time hehelped Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., establish the first four-year program in landscape architecture in America atHarvard, where he served on the faculty until the demands ofhis own practice forced him to resign.

An early town planner, Shurcliff also worked for theBoston Parks Department and the Metropolitan DistrictCommission for decades. In the 1920s, he was hired as ChiefLandscape Architect for the Colonial Williamsburg restoration,a position he retained until he retired in 1941 at the age of sev-enty-one. Throughout his professional life he threaded work onprivate estates through his burgeoning practice. By the timeCochrane engaged him, Shurcliff possessed a thorough ground-ing and sophistication in residential landscape design, and hisreputation in the Boston area was well established.

Historic New England’s archives contain several Shurcliffplans for proposed work on the property, the earliest datedSeptember 1913. In it the house, stables, and greenhouse aredepicted as pre-existing, as well as the curving drive along the

21Summer 2009 Historic New England

By January of 1915, the design had progressed to thestage of a planting plan that included a broad selection of old-fashioned and hybrid rose varieties and “climbing roses to betrained” inside and outside the walls, with clematis and hon-eysuckle cascading over the terminating wooden fences. Theshrubbery interspersed in the garden provided spring-flower-ing lilacs, and early summer-blooming azaleas and rhododen-drons. The planting plan indicates that it was not to be simply a display garden for the height of summer, for eachvariety of rose was carefully under-planted with spring-blooming narcissi, crocuses, violets, and tulips; with iris,anemones, lilies, larkspur, hollyhocks, English daisies, andcandytuft for midsummer bloom; and phlox, gladioli,chrysanthemums, asters, and fall-blooming crocuses provid-ing autumn color. Low, clipped dwarf boxwood hedges delin-eated beds, with Japanese yews and dwarf pines anchoring thesteps to the house. Four potted standard bay trees were posi-tioned evenly across the veranda leading to the house.

While the Palmstrom painting is clearly impressionisticin nature, the basic layout corresponds closely enough to the1915 planting plan that it seems likely that it was made at thevery least in response to the Shurcliff design. Although theplans in the Historic New England collection dated between

FACING PAGE Detail of the plan of the Cochrane estate in Hamilton,

Massachusetts, showing the rose garden at left. 1913. THIS PAGE

Shurcliff ’s planting plan for the rose garden. 1915.

1913 and 1915 were delineated in significant detail—a factthat suggests Cochrane maintained interest in pursuingimprovements to his Hamilton property—in fact, it is impos-sible to ascertain whether or not the designs were ever com-pleted on the ground. Although subsequent drawings mayhave been lost, it is just as likely that the timing of the com-mission decided its fate. Despite the fact that the UnitedStates did not enter World War I until 1917, by 1915 thecountry was feeling its effects; most households were curtail-ing unnecessary expenditures, and the Hamilton house wasthe third and least inhabited among Cochrane’s residentialholdings. Completed or not, however, Palmstrom’s lushpainting remains an elegant reminder of Cochrane andShurcliff’s garden scheme.

—Elizabeth Hope Cushing

Ms. Cushing is a landscape historian writing her disserta-tion on Arthur A. Shurcliff.

Dav

id C

arm

ack

22 Historic New England Summer 2009

O P E N H O U S E

vocative of long-vanishedways of living, old houses canfire our imaginations withvisions of lost ways of life.

But it’s easy to misconstrue what wesee in the architectural evidence of anold house, and sometimes we confuse,conflate, or embellish what we know.We create “old house myths,” perva-sive stories that seem to emerge overand over in newspaper articles on localhistory, amateur house tours, and realestate ads. Some contain a kernel oftruth, others seem pure fabrication,and a few we may never fully compre-hend. Preserving an old house withintegrity requires us to look beyond the myth to a more realistic under-standing of history.

Romanticized names for architec-tural elements in the house abound. Six-panel doors are renamed “Christian” or“Bible-and-Cross” doors, since the two

short lower panels are thought toresemble an open book (Bible) with acruciform connection of stiles (up-rights) and rails (horizontals) in thelong upper panels. There is no religioussymbolism to a pattern that is simply areflection of late eighteenth-centurytaste and functional operation. Doorswere made by joiners—the craftsmenresponsible for interior finish carpen-try, and in particular, for the small-scale work of uniting two or morepieces of wood in frames and panelsfor doors, shutters, paneling, and sashwindows. The broad center rail of thesix-panel form provided structure forthe hand-height latch or knob, whilethe hierarchy of panels, governed byaesthetics and classical proportion,moved from large, broad panels at thebottom to small, narrow panels at thetop. The whole had to be mortised andtenoned to allow the panels free move-

Old House MythsE

Preserving an old house with integrity requires

us to look beyond the myths to a more realistic

understanding of history.

ABOVE Six-panel doors in an 1804 house

in Duxbury, Massachusetts. RIGHT

Black-and-white painted chimneys at

the c. 1718 Sayward-Wheeler House,

York Harbor, Maine.

23Summer 2009 Historic New England

Dav

id B

ohl

Dav

id B

ohl

Historic New England Summer 200924

period was so far from accurate thatonce begun, it generally resulted inburning down the whole town.

Some old house legends carry anelement of verifiable fact whose signifi-cance has been amplified over time.Very wide floorboards or panels, forexample, are frequently noted as“King’s wood,” felled surreptitiouslydespite having been marked by thethree broad arrows with which theRoyal Navy blazed white pines overtwenty-four inches in diameter for useas ship’s masts. “Broad arrow” lawsdid exist as early as 1654, as there wereno European trees to match the dimen-

occupied the end or outside walls, werepainted to match, with light or whitebases and black caps. Furthermore,paint added a measure of protectionfrom moisture for the tall, narrowchimneys of late eighteenth- and earlynineteenth-century houses. And, Garvinnotes, naval bombardment in the

ment to expand and contract and yetbe sturdy and plumb.

“Widow’s walk” evokes sorrowand loss; roof balustrade does not.“Borning-room,” a phrase never foundin period usage, conveys a primitiveself-reliance lacking in period termssuch as “little chamber” or “kitchenchamber.” The term “Indian” shutter isanother misnomer that shows up fre-quently; interior shutters in eighteenth-century houses actually secured ahouse against burglars, sealed outdrafts, and provided privacy.

Other old house lore imbues archi-tectural features with false meaning.Architectural historian James Garvinhas debunked a popular myth aboutNew England’s painted white chim-neys, which held that white chimneyswith black caps were a signal, duringthe War of 1812, to the Royal Navy tospare the houses of supporters of theFederalist party (opponents of the war)from coastal bombardment. Again, thetruth lies with style, taste, and func-tion, not romance and intrigue. As theFederal style took hold, houses beganto be painted in white or light, delicateshades of gray, tan, or ochre with con-trasting black window sashes and exte-rior blinds. Chimneys, which frequently

THIS PAGE, TOP Paneled shutters at the

Sayward-Wheeler House slide into the walls.

BOTTOM Edgartown Harbor from the Fisher-

Bliss House, 1832, on Martha’s Vineyard,

Massachusetts, with the roof balustrade in

the foreground. FACING PAGE TOP Wide-board

floors at the 1785 Rocky Hill Meeting House,

Amesbury, Massachusetts. BOTTOM Conceal-

ment shoes, first half of the nineteenth

century.

Pho

to C

redi

t

25Summer 2009 Historic New England

sions of the colonies’ majestically talland straight white pines. But these lawswere not enforced, and the use of the finest available lumber, regardlessof the task to which it was to be put,was standard in American lumberingthrough the end of the nineteenth century. A memoir of 1800, quoted in William Cronon’s prize-winningChanges in the Land, noted that “therichest and straightest trees werereserved for the frames of the newhouses; shingles were rived from theclearest pine; all the rest of the timbercleared was piled and burned on thespot … All the pine went first. Nothingelse was fit for building purposes inthose days.”

The accuracy and context of otherold house lore might be verified or bet-ter understood with further research.The ivory “mortgage button,” forexample, is said to be “a long-standingNew England tradition” and may haveoriginated early in the nineteenth cen-tury on Nantucket. The placement of abutton of polished ivory or whaleboneatop the newel post of the stairs at theentry, by Nantucket tradition, connotedthe paying off of the mortgage on thehouse. At a time when mortgages werefar less common, of much shorterduration, and structured with largelump sum payments of principal at theend of the mortgage term, marking thedischarge of a mortgage with an orna-ment prominently placed in a publicpart of the house might have been apowerful display of status. Withoutperiod documentation tying the but-tons to the payment of the debt,though, it is hard to know if the ivoryornament was a proud announcementof freedom from debt or simply a dec-oration.

Newel posts, however, seem to bea common locus of mortgage-relatedold house stories. As newels balloonedinto the imposing walnut andmahogany features of late nineteenth-century stairhalls, they sometimesincorporated upright gas- or electric-

light fixtures, the necessary plumbingand wiring easily housed in the wood-en base. When outmoded lighting waslater removed, an intriguing hidingspace was left behind in the hollownewel. Tales include stories of mort-gages or deeds hidden or stored innewel posts, supposedly for quickretrieval in the event of fire, and of theburnt ashes of discharged mortgagesbeing poured into the newel post in cel-ebration.

And finally, old houses can containsome secrets about which we maynever know the full history. One of themost mysterious was the practice ofconcealing shoes or other clothingwithin the structure of the house. Themeaning behind the intentional place-ment of these items, often a single,well-worn child’s shoe in an inac-cessible location such as insidea wall or chimney, is un-known, but the practicewas common in Eng-land for centuries.“Concealment shoes”are regularly found inColonial houses in theU.S. as well. Thought tohave been placed as an invo-cation or protection against male-

volent spirits, concealment shoes areeerily evocative of their wearer, bearingall the patterns of individual wear butthe meaning of the placement remainsunknown.

Historians remind us that the pastwas different and that we should avoidimposing our own assumptions on yes-terday’s realities. A few good referencebooks, some careful study, and ahealthy dose of common sense canshed light on what seems mysterious orperplexing about our old houses.Clearing away the myths allows us tosee our old houses for what they are,tangible artifacts of the past and a pre-cious resource to be preserved.

—Sally ZimmermanPreservation Specialist

Dav

id B

ohl

141 Cambridge StreetBoston MA 02114-2702

Non-Profit OrganizationU.S. Postage

PAIDBoston, Massachusetts

Permit No. 58621

ABOVE Howard Johnson’s, best known

for its colorful highway landmarks, also

operated in urban locations. The busi-

ness grew from a drugstore soda foun-

tain to a nationwide franchise offering

twenty-eight flavors of ice cream.

Purchased at auction, this drawingof an iconic twentieth-century icecream shop now joins Historic NewEngland’s collection of more than35,000 architectural drawings depict-ing regional building types includinghouses, three-deckers, schools, cityhalls, factories, and even an elevatedrailway station.

—Lorna Condon Curator of Library and Archives

n the late 1940s, HowardJohnson’s, the highly successfulrestaurant chain known especiallyfor its ice cream, proposed a new

facility at the corner of Tremont andStuart streets in Boston, as shown inthe drawing at right. Founded inQuincy, Massachusetts, in 1925, thebusiness was undergoing a rapid postWorld War II expansion, of which thisproposal, by architect Joseph A. Cicco,was probably a part.

The use of color in this renderingemphasizes the up-to-date stylish designof the eatery, which was to be incorpo-rated into an existing building.Howard Johnson’s famous logo basedon the nursery rhyme “Simple SimonMet a Pie Man” is visible. CharlesGoodale, the delineator, provided con-text by portraying a city where late-model luxury automobiles cruise thestreets, stylish women walk their dogs,and theatrical productions like themusical revue Lend an Ear, abound. Itis likely, however, that the company didnot build the restaurant at this site butconstructed one of a similar design afew blocks away on Tremont Street.

I

A C Q U I S I T I O N S

28 Flavors