Bronchial Asthma in Pediatric

-

Upload

abdalla-mutwakil -

Category

Health & Medicine

-

view

201 -

download

4

description

Transcript of Bronchial Asthma in Pediatric

Bronchial Asthma In Pediatric

Abdullah Mutwakil Gamal - Pediatric Department

Sebha Medical Center

16 – 12 - 2013

Definition

Chronic airway inflammation leading to increase airway responsiveness that leads to recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and coughing particularly at night or early morning.

Epidemiology

- Worldwide about 235 million person have asthma

- Approximately 250,000 people die per year from the disease

- Boys : Girls = 2:1

- Adult Women : Adult men = 2:1

Etiology

- Genetic

- Environmental

Genetics :

The inheritance pattern of asthma demonstrates that it is a complex genetic disorder with environmental influences as with hypertension, atherosclerosis, arthritis, and diabetes mellitus. One of the greatest challenges faced by investigators in this area is the marked heterogeneity of the asthmatic phenotype. Although wheezing, coughing, and shortness of breath are common clinical endpoints for the

asthmatic disease process, any individual with asthma will respond differently to triggering factors (eg, allergens, viruses, cold air, tobacco smoke, exercise). The variability in the patterns and severity of the disease, its close clinical association with various atopic diseases, and the manner in which the symptoms change in relationship to age or in response to therapeutic intervention have made finding a single genetic “marker†elusive. Because asthma is frequently associated with atopy and is characterized by marked increases in airway responsiveness and inflammation, it should come as no surprise that various gene candidates

related to smooth muscle contractile mechanisms and to the immune system have been sought. Thus, linkage to 11q13 (the high-affinity IgE receptor), 5q (the cytokine gene cluster), 12q (IFN- 14,(³خ q (T-cell antigen receptor), as well as others have been considered as possible candidate loci. Polymorphisms in genes such as the خ± subunit of the IL-4 receptor, the ²2خ-adrenergic receptor, and the major cell surface receptor for endotoxin (CD14) may further influence disease expression and the response to therapy

ENVIRONMENTAL ALLERGENS AND IRRITANTS :

Respiratory allergies are a major factor in the pathogenesis of asthma in children. Furthermore, limiting exposure to relevant indoor allergens may lead to reductions in asthma symptoms, bronchial hyperresponsiveness, and use of asthma medications. Relevant indoor allergens include dust mite, cockroach, and cat and dog dander. One seemingly easily avoided irritant is environmental tobacco smoke. However, despite increased public awareness of the detrimental effect of smoking, it is often difficult to avoid second-hand smoke.

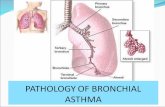

Pathophysiology

BRONCHIAL SMOOTH MUSCLE SPASM :

Bronchial smooth muscle spasm contributes significantly to airway obstruction. Evidence suggests that either the quantity or the function of bronchial smooth muscle in asthma is abnormal. Autopsy specimens obtained from asthmatic patients dying of their disease have demonstrated hypertrophy of the smooth muscle lining the airways. Some investigators have demonstrated a greater maximal

response to contractile agonists and an impaired relaxation to ²خ- agonists and theophylline in vitro. The airway contains a number of resident cells (mast cells, alveolar macrophages, airway epithelium, and endothelium) as well as immigrating inflammatory cells (eosinophils, lymphocytes, neutrophils, basophils, and platelets) that are capable of generating a wide variety of mediators and signaling molecules that can induce bronchospasm. These include histamine, platelet-activating factor, and

a number of derivatives of arachidonic acid including prostaglandin D2 and the cysteinyl leukotrienes (LTC4, LTD4, LTE4). Thus, it is likely that infiltration of inflammatory cells into the airway walls contributes to bronchial smooth muscle tone through the local effects of these various mediators.

EDEMA OF AIRWAY MUCOSA :

Edema of the airway mucosa results from increased capillary permeability with leakage of serum proteins into interstitial areas. A number of cell-derived mediators are capable of inducing edema formation, including histamine, prostaglandin E, LTC4, LTD4, LTE4, platelet-activating factor, and bradykinin. Resulting edema and cellular inflammation cause increased airway wall thickness in patients, which contributes to the mechanics of airway narrowing.

MUCOUS IMPACTION OF BRONCHI :

Mucous impaction of bronchi is another characteristic pathologic feature seen in untreated or undertreated asthma. Mucus production results from hyperplasia and metaplasia of goblet cells lining the airway. Impacted mucus leads to hyperinflation, focal atelectasis, and a productive cough.

Airway inflammation in asthma is a result of mast cell activation. An immediate immunoglobulin (Ig) E response to environmental triggers occurs within 15 to 30 minutes and includes vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, smooth-muscle constriction, and mucus secretion. Common triggers include dust mites, animal dander, cigarette smoke, pollution, weather changes, upper respiratory infections, certain drugs (ie, β-adrenergic antagonists, and some nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents),

and exercise (particularly when performed in a cold environment). Two to four hours after this acute response, a late-phase reaction (LPR) begins. The LPR is characterized by infiltration of inflammatory cells into the airway parenchyma; it is responsible for the chronic inflammation seen in asthma. Airway hyperresponsiveness may persist for weeks after the LPR.

History

• Determine whether there is a reversible airway obstruction by history. Are the wheezing and breathlessness reversible?

• Tightness in the chest.

• Recurrent cough.

• Exacerbation of the cough or wheeze at night or after exercise.

• Improvement of the cough or wheeze with bronchodilator therapy.

• History of atopy (eczema, hay fever).

• History of rhinitis, nasal polyps.

Examination

Signs in acute exacerbation

• Respiratory Distress : – Tachypnea, Working Alae

nasai

– Retractions

– Grunting

– Cyanosis, Drowziness, Coma.

• Ausculation : – Decreased air entry

– Prolonged expiration

– Wheeze, rhonchi

Signs of chronic illness

• Hyperinflated chest (Barrel-shaped chest)

• Harrison’s sulci

Managment

• Management of Acute Attack – Assessing & Classifying.

– Managing According to severity

• Management of Chronic Asthma – Assessing & Classifying.

– Managing According to Severity

Management of Acute Attack

• Classifying the patient :

– Group A : 1st attack of wheeze with no respiratory distress

– Group B :

• 1t attack of wheeze with respiratory distress

• Or recurrent wheeze

- Group C : Severe life-threatening asthma

- Drowzy of unconcious child, cyanosis, decreases oxygen saturation, child unable to speak or drink

Group A : 1st attack of wheeze with no respiratory distress

Can usually be managed at home with supportive care. A bronchodilator is not necessary.

Group B : 1t attack of wheeze with respiratory distress Or recurrent

wheeze

• give salbutamol by metered-dose inhaler and spacer device or, if not available, by nebulizer (see below for details). If salbutamol is not available, give subcutaneous adrenaline.

• Reassess the child after 15 min to determine subsequent treatment:

– If respiratory distress has resolved, and the child does not have fast breathing, advise the mother on home care with inhaled salbutamol from a metered dose inhaler and spacer

– device (which can be made locally from plastic bottles).

– If respiratory distress persists, admit to hospital and treat with oxygen, rapid-acting bronchodilators and other drugs.

Group C : Severe life-threatening asthma

• If the child has life-threatening acute asthma, is in severe respiratory distress with central cyanosis or reduced oxygen saturation ≤ 90%, has poor air entry (silent chest), is unable to drink or speak or is exhausted and confused, admit to hospital and treat with oxygen, rapid-acting bronchodilators and other drugs.

• In children admitted to hospital, promptly give oxygen, a rapid-acting bronchodilator and a first dose of steroids.

Oxygen :

Give oxygen to keep oxygen saturation > 95% in all children with asthma who are cyanosed (oxygen saturation ≤ 90%) or whose difficulty in breathing interferes with talking, eating or breastfeeding.

Rapid-acting bronchodilators :

Give the child a rapid-acting bronchodilator, such as nebulized salbutamol or salbutamol by metered-dose inhaler with a spacer device. If salbutamol is not available, give subcutaneous adrenaline, as described below.

Nebulized salbutamol The driving source for the nebulizer must deliver at

least 6–9 litres/min. Recommended methods are an air compressor, ultrasonic nebulizer or oxygen

In severe or life-threatening asthma, when a child cannot speak, is hypoxic or tiring with lowered consciousness, give continuous back-to-back nebulizers until the child improves, while setting up an IV cannula. As asthma improves, a nebulizer can be given every 4 h and then every 6–8 h.

cylinder, but in severe or life-threatening asthma oxygen must be used. If these are not available, use an inhaler and spacer. An easy-to-operate foot pump may be used but is less effective.

Put the dose of the bronchodilator solution in the nebulizer compartment, add 2–4 ml of sterile saline and nebulize the child until the liquid is almost all used up. The dose of salbutamol is 2.5 mg (i.e. 0.5 ml of the 5 mg/ml nebulizer solution).

If the response to treatment is poor, give salbutamol more frequently.

Giving salbutamol by metered-dose inhaler with a spacer device :

Spacer devices with a volume of 750 ml are commercially available.

Introduce two puffs (200 μg) into the spacer chamber. Then, place the child’s mouth over the opening in the spacer and allow normal breathing for three to five breaths. This can be repeated in rapid succession until six puffs of the drug have

been given to a child < 5 years, 12 puffs for > 5 years of age. After 6 or 12 puffs, depending on age, assess the response and repeat regularly until the child’s condition improves. In severe cases, 6 or 12 puffs can be given several times an hour for a short period.

Some infants and young children cooperate better when a face mask is attached to the spacer instead of the mouthpiece.

If commercial devices are not available, a spacer device can be made from a plastic cup or a 1- litre plastic bottle. These deliver three to four puffs of salbutamol, and the child should breathe from the device for up to 30s.

• Subcutaneous adrenaline

• If the above two methods of delivering salbutamol are not available, give a subcutaneous injection of adrenaline at 0.01 ml/kg of 1:1000 solution (up to a maximum of 0.3 ml), measured accurately with a 1-ml syringe. If there is no improvement after 15 min, repeat the dose once.

Steroids :

• If a child has a severe or life-threatening acute attack of wheezing (asthma), give oral prednisolone, 1 mg/kg, for 3–5 days (maximum, 60 mg) or 20 mg for children aged 2–5 years. If the child remains very sick, continue the treatment until improvement is seen.

• Repeat the dose of prednisolone for children who vomit, and consider IV steroids if the child is unable to retain orally ingested medication. Treatment for up to 3 days is usually sufficient, but the duration should be tailored to bring about

recovery. Tapering of short courses (7–14 days) of steroids is not necessary. IV hydrocortisone (4 mg/kg repeated every 4 h) provides no benefit and should be considered only for children who are unable to retain oral medication

Magnesium sulfate :

• Intravenous magnesium sulfate may provide additional benefi t in children with severe asthma treated with bronchodilators and corticosteroids. Magnesium sulfate has a better safety profi le in the management of acute severe asthma than aminophylline. As it is more widely available, it can be used in children who are not responsive to the medications described above.

• Give 50% magnesium sulfate as a bolus of 0.1 ml/kg (50 mg/kg) IV over 20 min.

Aminophylline :

• Aminophylline is not recommended in children with mild-to-moderate acute asthma. It is reserved for children who do not improve after several doses of a rapid-acting bronchodilator given at short intervals plus oral prednisolone. If indicated in these circumstances:

• Admit the child ideally to a high-care or intensive-care unit, if available, for continuous monitoring.

• Weigh the child carefully and then give IV aminophylline at an initial loading dose of 5–6 mg/kg (up to a maximum of 300 mg) over at least 20 min but preferably over 1 h, followed by a maintenance dose of 5 mg/kg every 6 h.

• IV aminophylline can be dangerous at an overdose or when given too rapidly.

• Omit the initial dose if the child has already received any form of aminophylline or caffeine in the previous 24 h.

• Stop giving it immediately if the child starts to vomit, has a pulse rate > 180/ min, develops a headache or has a convulsion.

Oral bronchodilators :

• Use of oral salbutamol (in syrup or tablets) is not recommended in the treatment of severe or persistent wheeze. It should be used only when inhaled salbutamol is not available for a child who has improved sufficiently to be discharged home.

• Dosage:

– Age 1 month to 2 years: 100 μg/kg (maximum, 2 mg) up to four times daily

– Age 2–6 years: 1–2 mg up to four times daily

Antibiotics :

• Antibiotics should not be given routinely for asthma or to a child with asthma who has fast breathing without fever. Antimicrobial treatment is indicated, however, when there is persistent fever and other signs of pneumonia

Supportive care :

• Ensure that the child receives daily maintenance fluids appropriate for his or her age. Encourage breastfeeding and oral fl uids. Encourage adequate complementary feeding for the young child, as soon as food can be taken.

Monitoring :

• A hospitalized child should be assessed by a nurse every 3 h or every 6 h as the child shows improvement (i.e. slower breathing rate, less lower chest wall indrawing and less respiratory distress) and by a doctor at least once a day. Record the respiratory rate, and watch especially for signs of respiratory failure – increasing hypoxia and respiratory distress leading to exhaustion.

Complications :

If the child fails to respond to the above therapy, or the child’s condition worsens suddenly, obtain a chest X-ray to look for evidence of pneumothorax.

Be very careful in making this diagnosis as the hyperinflation in asthma can mimic a pneumothorax on a chest X-ray.

Follow-up care :

Asthma is a chronic and recurrent condition.

˃ Once the child has improved sufficiently to be discharged home, inhaled salbutamol through a metered dose inhaler should be prescribed with a suitable (not necessarily commercial) spacer and the mother instructed on how to use it.

˃ A long-term treatment plan should be made on the basis of the frequency and severity of symptoms. This may include intermittent or regular treatment with bronchodilators, regular treatment with inhaled steroids or intermittent courses of oral steroids. Up-to-date international or specialized national guidelines should be consulted for more information

Management of Chronic Asthma

Peristent Asthma

Episodic Asthma

FrequentInfrequent

3 episodes/wk, with cough at

night/morning.

Episodes every 2–4 weeks

<4 episodes per year

Characteristics

Regular treatment is needed

- Use prophylactic inhaled steroids. - Long-acting B2-

bronchodilator may be helpful.

- Oral steroids may be needed.

- Oral leukotriene inhibitors may help

reduce steroids

Regular treatment is

needed

- Use B2-

bronchodilator as required.

- Use regular, low-dose

inhaled steroid.

No regular treatment needed.

- Treat acute

episodes with B2-Agonists

- Use nebulized bronchodilators and short-course prednisolone in

more severe episodes

Management Strategy

• Escalating therapy :

Having reviewed the history and categorized your patient in terms of clinical pattern and severity, use a logical, stepwise approach to escalating therapy

Before altering a treatment, ensure that treatment is being taken in an effective manner

The stepwise approach to drugs

Short-acting B2-bronchodilator for relief of symptoms Step 1 : occasional use of relief bronchodilators

Short-acting B2-bronchodilator as required + low-dose inhaled steroid (200–400micrograms/day)

Step 2 : regular inhaled preventer therapy

• Short-acting B2-bronchodilator as required + high-dose inhaled steroid or • Low-dose inhaled steroid +/– long-acting bronchodilator

Step 3 : add-on therapy

• Short-acting B2-bronchodilator as required + high-dose inhaled steroid (up to 800micrograms/day) + long-acting bronchodilator or • Theophyllines or ipratropium +/– alternate day steroid

Step 4 : persistent poor control

• Use daily steroid tablet in lowest dose • Maintain high-dose inhaled steroid at 800micrograms/day • Refer to respiratory specialist

Step 5 : continuous or frequent use of oral steroid

Doses : 0–2yrs

In this age group, a spacer device with an appropriate face mask is used, e.g. a small volume Aerochamber® or Ablespacer® which can take any inhaler; or a large volume Volumatic® or Nebuhaler®, which only fi t certain inhalers. Prophylactic therapy with inhaled steroids is more effective than cromoglicate.

Doses : 0–2yrs - cont

• Salbutamol via Volumatic®: <2400micrograms/day (in 6 doses). • Terbutaline via Nebuhaler®: <6000micrograms/day (in 6 doses). • Ipratropium via Volumatic®: <480micrograms/day (in 4 doses).

Acute treatment

• Budesonide via Nebuhaler®: 100–400micrograms/day. • Beclometasone via Volumatic®: 100–400micrograms/day.

Prophylactic treatment

Doses : 3–5yrs

• Salbutamol via Volumatic®: <3600micrograms/day (in 6 doses). • Terbutaline via Nebuhaler®: <6000micrograms/day (in 6 doses).

Acute treatment

• Budesonide via Nebuhaler®: 100–800micrograms/day. • Beclomethasone via Volumatic®: 100–800micrograms/day. • Fluticasone via Volumatic®: (>4yrs) 100–200micrograms/day.. • Salmeterol via Volumatic®: (>4yrs) 50micrograms/day. Must never be given alone and only when the child is also taking an inhaled steroid. • Combination inhaler: Seretide® (contains fi xed doses of fl uticasone and salmeterol).

Prophylactic treatment

Doses : 5–12yrs

• Salbutamol Accuhaler®: <7200micrograms/day (in 6 doses). • Salbutamol inhaler: (>12 years) <7200micrograms/day (in 6 doses). • Terbutaline inhaler: (>12 years) <7200micrograms/day (in 6 doses).

Acute treatment

• Budesonide Turbohaler®: 100–800micrograms/day. • Beclometasone via Accuhaler®: 100–800micrograms/day. • Fluticasone via Volumatic®: 100–400micrograms/day. • Combination inhaler – Seretide® (contains fi xed doses of fluticasoneand salmeterol); or Symbicort turbohaler® (fi xed doses of budesonide and formoterol).

Prophylactic treatment

General Advices

• Removal of feather or woollen bedding • Wrapping of mattress in plastic • Cleaning of carpets and furniture • No pets in the house if the child is allergic to them

Allergen avoidance

• No smoking in the house or car. • Parents/carers must be strongly encouraged to stop smoking completely.

Passive smoking

Oxygen therapy

Indications :

• Oxygen therapy should be guided by pulse oximetry . Give oxygen to children with an oxygen saturation < 90%. When a pulse oximeter is not available, the necessity for oxygen therapy should be guided by clinical signs, although they are less reliable. Oxygen should be given to children with very severe pneumonia, bronchiolitis or asthma who have:

■ central cyanosis

■ inability to drink (when this is due to respiratory distress)

■ severe lower chest wall indrawing

■ respiratory rate ≥ 70/min

■ grunting with every breath (in young infants)

■ depressed mental status.

Sources

• Oxygen should be available at all times. The two main sources of oxygen are cylinders and oxygen concentrators. It is important that all equipment is checked for compatibility

Oxygen delivery :

Nasal prongs are the preferred method of delivery in most circumstances, as they are safe, non-invasive, reliable and do not obstruct the nasal airway. Nasal or nasopharyngeal catheters may be used as an alternative only when nasal prongs are not available. The use of headboxes is not recommended. Face masks with a reservoir attached to deliver 100% oxygen may be used for resuscitation.

Nasal prongs :

These are short tubes inserted into the nostrils. Place them just inside the nostrils, and secure with a piece of tape on the cheeks near the nose. Care should be taken to keep the nostrils clear of mucus, which could block the flow of oxygen.

˃ Set a flow rate of 1–2 litres/min (0.5 litre/min for young infants) to deliver an inspired oxygen concentration of up to 40%. Humidification is not required with nasal prongs

Nasal catheter :

a 6 or 8 French gauge catheter that is passed to the back of he nasal cavity. Insert the catheter at a distance equal to that from the side of the nostril to the inner margin of the eyebrow.

˃ Set a fl ow rate of 1–2 litres/min. Humidification is not required

Nasopharyngeal catheter :

A 6 or 8 French gauge catheter is passed to the pharynx just below the level of the uvula. Insert the catheter at a distance equal to that from the side of the nostril to the front of the ear (see figure). If it is placed too far down, gagging and vomiting and, rarely, gastric distension can occur

˃ Set a flow rate of 1–2 litres/min to avoid gastric distension. Humidification is required.

Monitoring :

Train nurses to place and secure the nasal prongs correctly. Check regularly that the equipment is working properly, and remove and clean the prongs at least twice a day.

Monitor the child at least every 3 h to identify and correct any problems, including:

• oxygen saturation, by pulse oximeter

• position of nasal prongs

• leaks in the oxygen delivery system

• correct oxygen flow rate

• airway obstructed by mucus (clear the nose with a moist wick or by gentle suction)

Differential diagnosis of asthma

• Asthma

• Bronchiolitis

• Foreign body

• Pneumonia

Thank you for your time and attention