Tschumi, Bernard -Architecture and Limits

-

Upload

nidhi-subramanyam -

Category

Documents

-

view

313 -

download

2

Transcript of Tschumi, Bernard -Architecture and Limits

-

8/2/2019 Tschumi, Bernard -Architecture and Limits

1/10

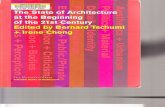

Bernard Tschurnl, Advertisements for Architecture, 1978.

To really appreciate architecture,you may even need to commita murder.~~I I " f i 9 t

A rc hi te ct ur e i s d ef in ed by t he a ct io ns i t w i tn es se sas much as b y t he e nc lo su re o f i ts wit lis . M urd eri n t he S tr ee t d if fe rs f ro m M u rd er in th e Cathedralin the sam e w ay as lov e in (he street differs fromthe S tr ee t o f L ov e. Radically.

Architecture and Limits

I.

In the work of remarkable writers, art ists, or composers onesometimes finds disconcerting elements located at the edgeof their product ion, at i ts limit. These elements, disturbingand out of character, are misfits within the art ist 's activi ty.Yet often such works reveal hidden codes and excesses hint"ing at other definitions, other interpretations.

-

8/2/2019 Tschumi, Bernard -Architecture and Limits

2/10

Program

The same can be said for whole fields of en-deavor: there are product ions at the limit ofl iterature, at thelimit ofmusic, at the limit of theater. Such extreme posi tionsinform llS about the state ofart, i ts paradoxes and its contra-dictions. These works, however, remain exceptions, for theyseem dispensable-a luxury in the field of knowledge.

In architecture, such productions of the limitare not only historically frequent but indispensable: archi-tecture simply does not exist without them. For example,architecture does not exist without drawing, in the same waythat architecture does not exist without texts. Buildings havebeen erected without drawings, but archi tecture i tself goesbeyond the mere process of building. The complex cultural,social, and philosophical demands developed slowly overcenturies have made architecture a form of know ledge in andof itself. Just as al l forms of knowledge use different modesof discourse, so there are key archi tectural statements that,though not necessarily built, nevertheless inform us aboutthe state of architecture-its concerns and its polemics-more precisely than the actual buildings of their time. Pira-nesi's engravings ofprisons, Boullee's washes ofmonuments,have drastical ly influenced archi tectural thought and its re-lated practice. The same could be said about particular ar-chitectural texts and theoretical positions. This does notexclude the built realm, for small construct ions of an exper-imental nature have occasionally played a similar role.

Alternately celebrated and ignored) theseworks ofthe limit often provide isolated episodes amidst themainstream ofcommercial production, for commerce cannot

102

-be ignored in a craft whose very scale involves cautiousclients and careful ly invested capital. Like the hidden cluein a detective story, these works are essential. In fact, theconcept of limits is directly related to the very definition ofarchi tecture. What is meant by to define-liTo determine theboundary or limits of," as well as "to set forth the essentialnature of.:"

Yet the current popularity of archi tecturalpolemics and the dissemination of its drawings in other do-mains have often masked these limits, restrict ing attentionto the most obvious of architecture 's aspects, curtail ing i t toa Fountainhead view of decorative heroics. By doing so, itreduces architectural concerns to a dictionnaite des ideesrecues, dismissing less accessible works of an essent ial na-ture or , worse, distorting them through association with themere necessities of a publicity market.

The present phenomenon is hardly new.The twentieth century contains numerous reductive policiesaimed at mass media dissemination, to the extent that wenow have two different versions of twentieth-century archi-tecture. One, a maximalist version, aims at overall social,cultural, poli tical , programmatic concerns while the other,minimalist, concentrates on sectors called style, technique,and so forth. But is it a question of choosing one over theother? Should one exclude the most rebellious and audaciousprojects, those of Melnikov or Poelzig for example, in theinterest of preserving the stylistic coherence of the modernmovement? Such exclusions, after all, are common architec-tural tactics. The modern movement had already started its

Architecture and Limits

-

8/2/2019 Tschumi, Bernard -Architecture and Limits

3/10

Program

attack on the beaux arts in the 1920s by a tact ically belitt linginterpretation of nineteenth-century architecture. In thesame way, the advocates of the International Style reducedthe modern movement's radical concerns to homogenizediconographic mannerisms. Today, the most vocal representa-tives ofarchitectural postmodernism use the same approach,but in reverse. Byfocusing their attack on the Internat ionalStyle, they make entertaining polemics and pungent jour-nalism but offer little new to a cultural context that has longincluded the same historical allusions, ambiguous signs, andsensuousness they discover today.

Architectural thought is not a simple matterof opposing Zeitgeist to Genius Loci, conceptual concerns toal legorical ones, historical allusions to purist research. Un-fortunately, architectural criticism remains an underdevel-oped field. Despite its current popularity in the media, itgenerally belongs to the traditional genre, with "personality"profi les and "practical ity" appraisals . Serious thematic cri-tique is absent, except in the most specialized publicat ions.Worse, critics there are partial to current reductive interpre-tations and often pretend that plurality of styles makes forcomplexity of thought. Thus it is not surprising that a solidcritique of the current frivolity of archi tecture and architec-tural reporting hardly exists. "The bounds beyond whichsomething ceases to be possible or allowable"? have beentightened to such an extent that we now witness a set ofreductions highly damaging to the scope of the discipline.The narrowing of architecture as a form of knowledge intoarchitecture as mere knowledge of form is matched only by

104 \105

-the scaling down of generous research strategies into opera-tional power broker tactics.

The current confusion becomes clear if onedistinguishes, amidst current Venice or Paris Biennales,mass-market publications, and other public celebrations ofarchi tectural polemics, a worldwide bat tle between this nar-row view ofarchitectural history and research into the natureand definition of the discipline. The conflict is no meredialectic but a real conflict corresponding, on a theoreticallevel, to practical battles that occur in everyday life withinnew commercial markets of architectural trivia, oldercorporate establishments, and ambitious universityintelligen tsia.

Modernism already contained such tacticalbattles and often hid them behind reductionist ideologiesIformalism, functionalism, rationalism). The coherencethese ideologies implied has revealed itself full of contradic-tions. Yet this is no reason to strip architecture again of itssocial , spatial, conceptual concerns and restr ict i ts limits toa terri tory of "wit and irony," "conscious schizophrenia,"1.1 dHal coding, /I and "twice-broken sph t-pedimen ts. /I

Such reduction occurs in other, less obviousways. The art world's fascination with architectural matters,evident in the obsessive number of "architectural reference"and "archi tectural sculpture" exhibit ions, is well matchedby the recent vogue among architects for advertising inreputable galleries. These works are useful only insofar asthey inform us about the changing nature of the art. To envyarchi tecture' s usefulness or, reciprocall y,to envy artists' free-

Architecture and Limits

-

8/2/2019 Tschumi, Bernard -Architecture and Limits

4/10

Program

dam shows in both cases naivete and misunderstanding ofthe work. Building may be abou tusefulness, architecture notnecessarily so. To call architectural those sculptures thatsuperficially borrow from a vocabulary ofgables and stairs isas naive as to call paintings some architects' tepid water-colors or the P.R. renderings of commercial fi rms.

Such reciprocal envy is based on the narrow-est limits of outmoded interpretations, as if each discipl inewere inexorably drawn toward the other's most conservativetexts. Yet the avant-garde of both fields sometimes enjoys acommon sensibility, even if their terms of reference inevi-tably differ. It should be noted that architectural drawings,at their best, are a mode of working, of thinking about ar-chitecture. By their very nature, they usually refer to some-thing outside themselves (as opposed to those art drawingsthat refer only to themselves, to their own materiality anddevices.)

But back to history. The pseudo-continuityof archi tectural history, with its neatly determined act ion-reaction episodes, is based on a poor understanding ofhistoryin general and architectural history in particular. After all ,this history is not l inear , and certain key product ions are farfrom enslaved to artificial continuities. While mainstreamhistorians have dismissed numerous works by qualifyingthem as "concep tual archi tecture," 1 cardboard archi tee-ture," "narrative" or "poetic" spaces, the time has come tosystematically question their reductive strategies. Question-ing them is not purely a matter of celebrating what theyreject. On the contrary, it means understanding what bor-

106

derline activit ies hide and cover. This history, cr itique, andanalysis remains to be done. Not as a fringe phenomenon[poets, visionaries or , worse, intel lectuals) but as central tothe nature of architecture.

II.

The limits of architecture are variable: each decade has itsown ideal themes, its own confused fashions. Yet each ofthese periodical shifts and digressions raises the same ques-tion: are there recurrent themes, constants that are specif i-cally architectural and yet always under scrutiny-anarchitecture of limits!

As opposed to other disciplines, architecturerarely presents a coherent set ofconcepts-a definition-thatdisplays both the continuity of its concerns and the moresensi tive boundaries of its activi ty . .However, a few aphor-isms and dictums that have been transmitted through cen-turies of architectural literature do exist. Such notions asscale, proportion, symmetry, and composition have specificarchitectural connotations. The relation between the ab-straction ofthought and the substance ofspace-the Platonicdistinction between theoretical and practical-is constantlyrecalled: to perceive the architectural space of a building isto perceive something-that-has-been-conceived. The oppo-sition between form and function, between ideal types andprogrammatic organization, is similar ly recurrent , even ifboth terms are viewed, increasingly, as independent.

Architecture a n d Limits

-

8/2/2019 Tschumi, Bernard -Architecture and Limits

5/10

Program

One of the more enduring equations is theVitruvian tril ogy- venustas, firmi tas, utilitas-" attracti veappearance," "structural stabil ity," "appropriate spatial ac-commodation." It is obsessively repeated throughout cen-turies of architectural precepts, though not necessarily inthat order. Are these possible architectural constants, theinherent limits without which architecture does not exist?Or is their permanence a bad mental habit, an intellectuallaziness 0bserved throughout his tory? Does persis tence gran tvalidity? If not, does architecture fail to realize the displace-ment of limits it has held for so long?

The twentieth-century has disrupted the Vitruvian trilogy,for archi tecture could not remain insensitive to industriali-zation and the radical questioning of institutions (whetherfamily, state, or church) at the turn of the century. The firstterm-attractive appearance (beauty)-slowly disappearedfrom the vocabulary, while structural l inguistics took holdof the archi tect's formal discourse. Yet early architecturalsemiotics merely borrowed codes from literary texts, appliedthem to urban or architectural spaces, and inevitably reomained descriptive. Inversely, attempts to construct newcodes meant reducing a building to a "message" and its useto a "reading." Much of the current vogue for quotations ofpast architectural symbols proceeds from such simplisticinterpreta hans.

Inrecen t years, however, serious research basapplied linguistic theory to architecture, adding an arsenalof select ion and combination, subst itution and contextual-

108

-i ty, metaphor and metonymy, similarity and contigui ty, fol-lowing the terms of [akobson, Chomsky, and Benveniste.Although exclusively formalist manipulation often exhaustsitself if new cri ter ia are not injected to allow for innovation,its very excesses can often shed new light on the elusiveboundaries of the "prison-house" of architectural language.At the limit, this research introduces preoccupations withthe notion of subject and with the role of subjectivity inlanguage, differentiating language as a system of signs fromlanguage as an act accomplished by an individual .

The concern for the next term-structural stabil ity-seemsto have disappeared during the 1960s without anyone real-izing or discussing i t. The consensus was that anything couldbe built, provided you could pay for it. And concern withstructure vanished from conference rosters and dwindled inarchitectural courses and magazines. Who, after all, wantsto stress that the Doric pilasters of current histori-cism are made of painted plywood or that applique moldingsare there to give metaphorical substance to hollow walls?

In the 1980s, interest in engineering issuesreturned but was often marked by a particular condit ion: theprogressive reduct ion of building mass over a period of cen-turies meant that architects could arbi trarily compose, de-compose, and recompose volumes according to formal ratherthan structural laws. Modernism's concern for surface effectfurther deprived volumes of material substance. Today, mat-ter hardly enters the substance of walls that have been re-duced to sheetrock orglass partitions that barely difieren tiate

Architecture and Limits

-

8/2/2019 Tschumi, Bernard -Architecture and Limits

6/10110

Program

inside from outside. The phenomenon is not likely to bereversed, and those who advocate a return to "honesty ofmaterials" or massive poche walls are often motivated byideological rather than practical reasons. It should bestressed, however, that any concern over material substancehas implicat ions beyond mere structural stability. The ma-teriality of architecture, after all, is in its solids and voids,its spatial sequences, its articulations, its collisions. (Oneremark in passing: some will say concern for energy conser-vation replaced the concern for construction, Maybe. Re-search in passi ve and acti veenergy conserva tion, solar power,and water recycling certainly enjoys a distinct popularity yetdoes not greatly affect the general vocabulary of houses orcities. I

The sole judge of the last term of the trilogy, "appropriatespatial accommodation" is, of course, the body, your body,my body-the starting point and point of arrival of architec-ture. The Cartesian body-as-object has been opposed to thephenomenological body-as-subject, and the materiality andlogic of the body has been opposed to the materiality andlogic of spaces. From the space of the body to the body-in-space-the passage is intricate. And that shift, that gap inthe obscuri ty of the unconscious, somewhere between bodyand Ego, between Ego and Othe .... Architecture still hasnot begun to analyze the Viennese discoveries at the turn ofthe century, even if architecture might one day inform psy-choanalysis more than psychoanalysis has informedarchitecture,

111

-The pervasive smells of rubber, concrete,

flesh; the taste ofdust; the discomforting rubbing ofan elbowon an abrasive surface; the pleasure of fur-lined walls andthe pain of a corner hit upon in the dark; the echo of aha11-space is not simply the three-dimensional projection of a .mental representation, but it is something that is heard, andis acted upon. And it is the eye that frames-the window,the door, the vanishing ri tual ofpassage .. .. Spaces ofmove-ment-corridors, staircases, ramps, passages, thresholds;here begins the art iculation between the space of the sensesand the space of society, the dances and gestures that com-bine the representation of space and the space of represen-tation. Bodies not only move in but generate spaces producedby and through their movements. Movements-of dance,sport, war-are the intrusion of events into architecturalspaces. At the limit, these events become scenarios or pro-grams, void ofmoral orfunctional implications, independentbut inseparable from the spaces that enclose them.

So a new formulation of the old trilogyap-pears. It overlaps the three original terms in certain wayswhile enlarging them in other ways ..D istinctions can bemade between mental, physical, and social space or, alter-nat ively, between language, matter , and body. Admit tedly,these distinctions are schematic. Although they correspondto real and convenient categories of analysis (Jlconceived,""perceived," "experienced"), they lead to different ap-proaches and to different modes of architectural notation.

A change is evident in architecture 's status,in its relationship to i ts language, its composing materials ,

Architecture and Limits

-

8/2/2019 Tschumi, Bernard -Architecture and Limits

7/10

formance as a whole .... '

An archi tectural program is a l is t of required util it ies; it indicates

Program

and its individuals or societies. The question is how thesethree terms are arti cula ted and how they rela te to each otherwithin the field of contemporary pract ice. It is also evidentthat since architecture 's mode of production has reached anadvanced stage of development, i t no longer needs to adherestrictly to linguistic, material, or functional norms but candistort them at will. And, finally, it is evident from the roleof isolated incidents-often pushed aside in the past-thatarchitecture's nature is not always found within building.Events, drawings, texts expand the boundaries of sociallyjustifiable constructions.

The recent changes are deep and lit tle under-stood. Architects-at-large find them. diff icult to accept, in-tuitively aware as they are that their craft is being drasticallyaltered. Current architectural historicism is both a part ofand a consequence of this phenomenon-both a sign of fearand a sign ofescape. To wha t extent do such explosions, suchchanges in the conditions of the production of architecturedisplace the limits ofarchitectural act ivities in order to cor-respond to their mutations?

their relations, but. suggests nei ther their combination nor theirproportion."

of performance; hence the i tems themselves col lect ively, the per-

To address the notion of the program today is to enter aforbidden field, a field architectural ideologies have con-sciously banished for decades. Programmatic concerns havebeen dismissed both asremnants ofhumanism and as morbidattempts to resurrect now-obsolete functionalist doctrines.These attacks are revealing in that they imply an embeddedbelief in one particular aspect of modernism-the preemi-nence of formal manipulation to the exclusion of social orutilitarian considerations, a preeminence that even currentpostmodernist architecture has refused to challenge.

But let us briefly recall some historical factsthat govern the notion of the program, Although the eigh-teenth century's development of scientific techniques basedon spatial and structural analysis had already led archirec-tural theorists to consider use and construction as separatedisciplines, and hence to stress pure formal manipulat ion,the program long remained an important part of the archi-tectural process. Implicitly or explicit ly related to the needsof the period or the state, the program's apparently object iverequirements by and large reflected particular cultures andvalues. This was true of the beaux arts' "Stables for a Sov-ereign Prince" of 1739 and the "public Festival for the Mar"riage of a Prince" of 1769. Growing industrialization and

I I I _

Program: a descriptive notice, issued beforehand, of any formalseries of proceedings, as a fest ive celebration, a course ofs tudy etc.(... ),alist of the items or "numbers" of a concert etc., in the order

112 Architecture a n d Limits

-

8/2/2019 Tschumi, Bernard -Architecture and Limits

8/10

Program

urbanization soon generated their own programs. Depart-ment stores, railway stations, and arcades were nineteenth-century programs born of commerce and industry. Usuallycomplex, they did not readily result in precise forms, andmediating factors like ideal buildings types were often re-quired, risking a complete disjunction between "form" and"content." The modern movement's early attacks 011 theempty formulas of academicism condemned these disjunc-tions, along with the decadent content of most beaux artsprograms, which were regarded as pretexts for repetitivecomposi tional reci pes. The concept of the program itseli wasnot attacked, but, rather, the way it reflected an obsoletesociety. Instead, closer l inks between new social contents,technologies, and pure geometries announced a new func-tionalist ethic. At the first level, this ethic emphasized prob-lem solving rather than problem formulating: goodarchitecture was to grow from the objective problem peculiarto building, site, and client, in an organic or mechanicalmanner. On a second and more heroic level, the revolut ion-ary urges of the futurist and constructivist avant-gardesjoined those of early nineteenth-century utopian socialthinkers to create new programs. "Social condensers," com-munal kitchens, workers' clubs, theaters, factories, or evenunites d'hobitation accompanied a new vision of social andfamily structure. In a frequently naive manner, architecturewas meant to both reflect and mold the society to come.

Yet by the early 1930s in the United Statesand Europe, a changing social context favored new forms and

11.4

technologies at the expense of programma tic concerns. Bythe 1950s modern archi tecture had been emptied of its earlyideological basis, partially due to the virtual failure of itsutopian aims. Architecture also found a new base in thetheories of modernism developed in l iterature, art, and mu-sic. "Form follows form" replaced "form follows function, /Iand SOOl1 at tacks on funct ionalism were voiced by neo-mod-ernists for ideological reasons, and by postmodernists foresthetic ones.

In any case, enough programs managed tofunction in buildings conceived for entirely different pur-poses to prove the simple point that there was no necessarycausal relationship between funct ion and subsequent form,or between a given building type and a given use. Amongconfirmed modernists , the more conventional the program,the better; conventional programs, with their easy solutions,left room for experimentation in style and language, muchas Karl Heinz Stockhausen used national anthems as thematerial for syntactical transformations.

The academization ofconstructivism, the in-fluence ofl iterary formalism, and the example of modernistpainting and sculpture all contributed to architecture's re-duction to simple linguistic components. When applied toarchitecture, Clement GreenbeJg's dictum that content be"dissolved so completely into form that the work of art orliterature cannot be reduced inwhole or in part to anythingbut itself ... subject matter or content becomes somethingto be avoided like a plague" further removed considerationsof use. Ultimately, in the 1970s, mainstream modernist crit -

Architc~t"rl' and Limits

-

8/2/2019 Tschumi, Bernard -Architecture and Limits

9/10

Much of the theory ofarchitectural modern-ism [which, notably, emerged in the 1950s rather than in the1920sl was similar to all modernism in its search for thespecif ici ty ofarchitecture, for that which is characteristic ofarchitecture alone. But how was such specificity defined?Did it include or exclude use? It is significant that architec-tum! postmodernism's challenge to the l inguist ic choices ofmodernism has never assaulted its value system. To discuss"the crisis of architecture" in wholly stylistic terms was afalse polemic, a clever feint aimed at masking the absence o.fconcerns about use.

While it is not irrelevant to distinguish be-tween an autonomous, self-referential architecture that tran-scends history and culture and an architecture that echoeshistorical or cultural precedents and regional contexts, itshould be noted that both address the same definition ofarchitecture as formal or styl ist ic manipulation. Form stillfollows form; only the meaning and the frame of reference

differ. Beyond their diverging esthetic means, both conceiveof archi tecture as an object of contemplation, easi ly acces-sible to critical attention, as opposed to the interaction ofspace and events, which is usually unremarked upon. Thuswalls and gestures, columns and figures are rarely seen aspart of a single signifying system. Theories ofreading, whenapplied to architecture, are largely fruitless in that they re-duce it to an art of communication or to a visual art [the so-cal led single-coding of modernism, or the double-coding ofpostrnodemism], dismissing the "intertextuality" thatmakes architecture a highly complex human activity. Themultiplicity of heterogeneous discourses, the constant inter-action between movement, sensual experience, and concep-tual acrobatics refute the paral lel with the visual ar ts .

If we are to observe, today, an epistemologi-cal break with what is generally called modernism, then itmust also question i ts own formal contingency. By no meansdoes this imply a return to notions of function versus form,to cause-and-effect relationships between program and type,to utopian visions, or to the varied positivist or mechanisticideologies of the past. On the contrary, it means going beyondreductive interpretations of archi tecture. The usual exclu-sion of the body and its experience from all discourse on thelogic of form in a case inpoint.

The mise-en-scenes of Peter Behrens, whoorganized ceremonies amidst the spaces of Iosef MariaOlbrich's Iviathildenhoene, Hans Poelzig 's sets for The Go-lem, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy's stage designs, which combinedcinema, music, sets, and act ions, freezing simultanei ties; El

Program

icism, by focusing on the intrinsic quali ties of autonomousobjects, formed an alliance with semiotic theory to makearchitecture an easy object of poetics.

But wasn't architecture different from paint-ing or l iterature? Could use or program be part ofform ratherthan a subject or content? Didn't Russian formalism differfrom Greenbergian modernism in that, rather than banishingconsiderations of content, it s imply no longer opposed formto content but began to conceive of it as the totality of thework's various components? Content could be equallyformal.

116Architecture and Limits

-

8/2/2019 Tschumi, Bernard -Architecture and Limits

10/10

Program

Lissitzky's displays of electromechanical acrobatics, OskarSchlemmer 's gestural dances, and Konstantin Meinikov's"Montage of Attract ions," which turned into real architec-tural constructions-all exploded the restr ict ive orthodoxyof architectural modernism. There were, of course, prece-dents-Renaissance pageants, Jacques Louis David's revo-lutionary fetes, and, later and more sinister , Albert Speer'sCathedral ofIce and the Nuremberg Rally.

More recently, departures from formal dis-courses and renewed concerns for archi tectural events havetaken an imaginary programmatic mode.! Alternatively, ty-pological studies have begun to discuss the critical "affect"ofideal building types that were historically born offunctionbut were later displaced into new programs alien to theiroriginal purpose. These concerns for events, ceremonies, andprograms suggest a possible distance vis-a-vis both modernistorthodoxy and historicist revival.

118

![[Bernard Tschumi] the Manhattan Transcripts(BookZZ.org)](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/563dbbc3550346aa9ab014b6/bernard-tschumi-the-manhattan-transcriptsbookzzorg.jpg)