Miller-Apostates and Bandits

Transcript of Miller-Apostates and Bandits

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

1/25

Maisonneuve & Larose

Apostates and Bandits: Religious and Secular Interaction in the Administration of LateOttoman Criminal LawAuthor(s): Ruth A. MillerSource: Studia Islamica, No. 97 (2003), pp. 155-178Published by: Maisonneuve & LaroseStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4150605

Accessed: 28/11/2009 00:48

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mal.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Maisonneuve & Larose is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Studia Islamica.

http://www.jstor.org

http://www.jstor.org/stable/4150605?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=malhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=malhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/4150605?origin=JSTOR-pdf -

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

2/25

StudiaIslamica, 003

Apostatesand Bandits:Religiousand SecularInteractionin the Administrationof Late Ottoman CriminalLaw

In 1887, the professional alim, Omer Hilmi Efendi, replaced theequally professional alim, Ahmet Hilmi Efendi, as Ottoman central cas-sation court president - one of the highest offices within the OttomanEmpire's secularizing' nizam'2 criminal court system. 3 In the process,very little comment about the affiliations of these members of theulema corps was made. Indeed, the document noting this transfer ofadministrative duties appears to take the integration of these membersof the religious establishment into the nizami court system purely as amatter of course - much like the hundreds of similar documentsappointing lower level ulema to other nizaml administrative positions.Such being the case, one begins to wonder where exactly the classicaland paradigmatic nineteenth century battle between a conservative, tra-ditional religious establishment and a reformist, modernizing secular

1. The word "secular"s a problematic nd loadedone. It hasa numberof mea-ningsandnuancesdependinguponwho is using t andfor whatpurposes.Formypurposes, am calling"secular"anythingwith ties to the politicalhierarchy ea-ded up bythe Sultannot in hiscapacity sCaliph.I amalsocalling"secular"ny-thing that is not tied to the religioushierarchyheadedup by the Seyhiilislam.Finally, am calling"secular"nylegalcase thatwasnot triedaccording o basicIslamic awprinciples.2. Relating o the "secular"ourthierarchyetup in the OttomanEmpire o sup-portthe government'seformefforts.3. iradeler,Dahiliye,85244 18 L 1305.

155

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

3/25

RuthA. MILLER

establishment played out.4 Upon first glance, it seems clear that thisbattle, if it did indeed occur, was certainly not engaged in the arena ofcriminal law reform. The purpose of this article will be to examine thisimmediate conclusion in more depth - to consider the interaction,rather than competition, between the religious and secular legal esta-blishments in the context of late Ottoman reform. By focusing uponone smaller aspect of the Ottoman criminal law system - court proce-dure and administration - it will attempt to demonstrate that as timepassed, the Ottoman religious and secular legal systems became integralparts of one another. Moreover, as this integration occurred, theOttoman legal system became increasingly both more modern andmore authoritarian.

Before continuing with the details of the argument, however, a briefbit of historical background will help to put it into context. Throughoutthe 19th century, the Ottoman government promulgated three codes of

4. Almost withoutexception,scholars n the pasthaveseen Ottomanreform ngeneral,and Ottomanlegalreform n particular, s a processof separation f thereligiousand the secular,with the secular ventually"overcoming"he religious.See for exampleEhud R. Toledano,"The LegislativeProcess n the OttomanEmpire n the EarlyTanzimatPeriod," nternationalournalof Turkish tudies1,no. 2(1980): 99-106. p. 99. T. Miras,"Le tanzimatet son systemelegislatif,"Annalesde la Facultede Droit d'Istanbul AFDI) 17, no. 26, 27, 28 (1967). pp.26-28. K6ksalBayraktar,Influence u droitfrangaiseur les tentativesdu modejuridique urcpours'occidentaliser,"nnalesde la FacultideDroitd'Istanbul2(1979). pp. 321-2. And manyothers.For a more classicalnterpretation f thisthesis,see MaxWeber,EconomyndSociety.New York:BedminsterPress,1968.vol. 2, p. 822. "Weactually ind in all the greatIslamicempiresof the presenttime a dualismof religiousand secularadministration f justice:the temporalofficial tandsbeside hekhadi,and the secularawbeside heshari'ah... hissecu-lar aw(qanun)began o expand romtheverybeginning..,andto assumencrea-sing importancen relation o the sacred aw,the more the latterbecamestereo-typed."B.A.Robertson,"TheEmergence f the ModernJudiciaryn the MiddleEast," n Chibli Mallat,ed. Islam and PublicLaw: Classical nd ContemporaryStudies,London:GrahamandTrotman,1993, likewiseadheres o thisthesis.Healso, however,makesan importantpoint that "theoveralleffectof this develop-ment was... enhancing heability o manipulate nd usereligion or thepurposesof the state."p. 110. Manyhavelikewiseseen OttomanandTurkishreformatleastto some extent asa processof liberalization. ee, forexample,B. Lewis,TheEmergencefModernTurkey. ondon:OxfordUniversityPress,1968.

156

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

4/25

ApostatesndBandits

criminal law. The first appeared in 1840, directly following the 1839Edict of Gulhane, which kicked off the Tanzimat5 reform period. Thereis some debate as to whether or not this particular code was a "real"code, 6 but suffice it to say for now that whatever its merits, it was anattempt at the very least to regularize the administration of criminal lawand also to introduce certain quasi-liberal ideas into the newly forminglegal system.7 A decade later, in 1851, a second code of criminal lawappeared - quite similar to the first, but inclusive of the rulings of thepast eleven years.8Like the first code, the second also represented a clearattempt to place criminal law squarely into the new Tanzimat frame-work. Indeed, it is organized rhetorically in exactly the same way as the1839 Giilhane Edict - with an introduction, and then sections on res-pectively "crimes against life," "crimes against honor," and "crimesagainst property."'9Finally, in 1859, the Ottoman government promul-gated a last code of law inspired o by the 1810 Napoleonic CriminalCode. It might also be mentioned that in 1876 the first OttomanConstitution appeared, " inspired by the Belgian law. Each of thesecodes and legislations represented a new phase in the development ofOttoman legal ideology. Moreover, as the cases tried in this period will

5. "Tanzimat"iterallymeans "regulations."n brief it refersto the Ottomangovernment's ttemptbetweenthe years1839 and 1876 to introducequasi-libe-ral deasandpractices therightto life, honor,andproperty f all Ottomansub-ject/citizens into the statestructureand, more importantly,o centralizeand"organize"he systemof governance.6. See for example G. Bozkurt,"Tanzimatand Law," Tanzimat'in 50. YdDoiniimii UluslararasiSempozyumu.Ankara:TUrkTarih Kurumu Yayinlari, 1994.pp. 279-286. B. Lewis, p. 161. and others.7. See the explicit references to the Edict of Giilhane in the 1840 Code as pre-sented in AhmedLutfi,Mir'at-zAdalet,yahudTarihfe-iAdliye-yiDevlet-iAliyye.Istanbul: Kitapli Ohannes, 1304/1888. p. 128.8. Ibid p. 150. Bozkurt, p. 282.9. Ahmed Litfi, p. 150.10. Once again, there is debate about the extent to which the 1859 OttomanCode was a "translation"of, versus an homage to, the Napoleonic Code. SeeBozkurt, p. 282, N. Sensoy, "Reception of Foreign Codes of Criminal Law andCriminal Procedure in Turkey," AFDI 5, no. 6(1956): 182-185. p. 183. K.Bayraktar,p. 321. D. Ergil, "Secularization of Islamic Law and Institutions inTurkey,"Studies in Islam 15(1978): 71-142. p. 97. T. Miras, p. 36.11. R. Okandan, Amme Hukukumuzun Ana Hatlart. Istanbul: FakiiltelerMatbaast, 1957. p. 73.

157

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

5/25

Ruth .MILLERdemonstrate,achlegislation lsopushed he Ottomancriminal awsystemnamore nteractivelyeligiousndsecular nda moreauthori-tarian irection.

CASES1840-1850Theyears1840to 1850mark hebeginningf a Tanzimatnfluenceonthedirection fOttomanriminalaw,and t isintheseyearshat hefirstnizamiriminalodewaspromulgated.hecases riednthisperiodconsequentlyeflecthe firstattemptstpassingentencesnd egitimi-zing hese entencesymeans f aphilosophyther han,orinadditionto,?eriatorthewillof theSultan.Nizami onceptst thistimewere elfconsciouslyndquiteextensivelyntegratednto theoverallegal rame-work.Theywereso greatly mphasized,n fact,that the nextperiodwould be a time of readjustmentoward philosophymoreorientedtowarder 'principles.2At thesame ime,the procedureorbringingasesandcoming oconclusionsbout hem emainedimilaro,althoughotexactlyhesameas,thatofthepre-Tanzimateriod.ngeneral,3theprincipalsf a caseorthepolicewouldbringhatcase o theattention f eitherhe ocal ouncilor thegovernor,tentativeecision ouldbe taken nd, fnecessary,er'writs legitimizinghedecisionomposed.hewrits nda reportwouldthenbesent o thecentralouncilMeclis-i d1d),heoriginal rits,f rele-vant,wouldbeconfirmedythe officeof the?eyhiilislam,5thereports

wouldbeconfirmedythecentralouncil,nd inallyverythingouldbesentbacko the localcouncil rgovernoror mplementation.hesitua-tion nplace,herefore,asone nwhich tthe ocalevel he emporalnddivineegalystemsverlappedoalargextent. hegovernornd he ocalcouncil awboth?er iandnizamiases. heyalsoworkedn concert iththe localreligiousuthorityhoulda?er iwritbenecessary.t a higherlevel,however,hings emainedelativelyeparate.heoffice f theSeyhii-12. See below for an elaboration.13.Seebeloworadiscussionfspecificases.14.Literallylam-z r . Theconfirmationfa legal ecisionomingromheoffice of the Seyhiilislam r a local religiousauthorityand attached o manyofthese ase iles.15. Head of the Ottomanreligioushierarchy.158

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

6/25

Apostatesnd Bandits

lislam saw the ?er 'iwrits and confirmed them, the central council lookedat the reports and confirmed them, neither consulted the other, and thenthe confirmation was sent back to the local authorities.As time passed, amarked change occurred in the process described above.On a more concrete level, we can look at the numerical distributionof Jer 'iv. nizamnconcepts as they relate to, variously,the legitimization oflegal decisions, the proof used in coming to these decisions, and the sen-tences carried out after confirming the decisions:

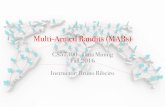

Period/Type6 Seriat/Yes Nizami/No BothlSiyasit7 Neither$er 'iWrit Ser 'iWrit Sentence1840-1850

Writ:yes/no 59% 41%Legitimization 24% 30% 35% 12%Proof 58% 16% 16% 11%Sentence 39% 45% 16%1851-1858Writ: yes/no 62% 39%Legitimization 35% 12% 41% 12%ProofSentence 57% 21% 21%1859-1876Writ:yes/no 47% 53%Legitimization 16% 19% 62% 4%Proof 29% 29% 41%Sentence 20% 76% 4%

16. This tablewascomposedof information ound in the followingdocuments.iradeler:MV323, 515, 53, 19, 210, 137, 59, 129, 237, 398, 417, 355, 555, 519,540, 343, 905, 939, 817, 924, 808, 560, 330, 493, 328, 310, 299, 188, 294, 534,36, 96, 63, 1863, 498, 3025, 901, 83, 69, 104, 411, 364, 306, 758, 1006, 900,205, 10580, 11154, 11568, 17927, 16180, 7547, 7996, 11495, 15203, 8540,18500, 25820, 23337, 20156, 21908, 21943, 23306, 15105; DAA 296, 577,825, 834; SD 957; MM 2028; AM 1311-M-2/29, 1310-S-9/3, 1317-Z-14/6,1314-Za-15/7, 1313-Z-14/6, 1327-Za-8/8, 1319-M-18/8, 1328-S-14/19, 1328-C-8/7; Dah. 617, 765, 3095, 20911, 39448, 31370, 68969, 87271, 95210,16465, 69484. Meclis-iViikela:35/17, 93/28, 36/7, 109/8, 101/32, 106/72,110/72, 110/87, 118/28, 121/32, 232/121, 231/199.17. "Referringo the politicalauthority."

159

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

7/25

RuthA. MILLER

As the table above demonstrates, out of a sample of twenty-five docu-ments and thirty-five serious '8 cases spanning the years 1840-1850,59% " contain ?er 'iwrits and 41% 20 do not. When it comes to the legi-timization of decisions - that is, a decision that is taken by "the require-ments of ?eriat,"21 a decision taken by "the requirements of the imperiallegal code," or a decision that rests upon a combination of the two -24% 22 were decided by the requirements of ?eriat, 30% 23 were decidedby the requirements of the code, 35% 24 were decided by a combinationof both, and 12%25 referenced neither. As for the proof forwardedduringthe trials,26 58% 27 were proved by ,er't rules, 16% 28 were proved accor-ding to the rules set out in the code, 16% 29 were proved using a combi-nation of the two, and 11%30referenced neither. Finally,of the sentencesimposed, 39% 3 were ver'f entences, 45% 32 were sentences taken fromthe code, and 16% 33 were siyasi (discretionary political/administrative)sentences - that is, for example, banishment or execution legitimizedsolely by the will of the padigahor the political authority.We can tentatively conclude based upon these numbers that in theperiod between 1840 and 1850 - overseen by the first Tanzimat criminalcode - there was to some extent an incorporation of ?er 'Iprinciples intothe nizami system. The legitimization of cases, for example, was undoub-

18. Tryingsuch crimes as murder, heft, rebellion,corruption,and brigandage(witha heavyemphasison murder).19. Sixteenout of twenty-seven.20. Elevenout of twenty-seven.21. Almostalwaysa ktsaslex talionis)case,sometimesa diyet bloodmoney)case,but alsoon occasion,a jailsentenceor hard abor.22. Eightout of thirty-four.23. Tenout of thirty-four.24. Twelveout of thirty-four.25. Fourout of thirty-four.26. Manyreportswillnotethat the casewas"tespit"r"riiyet"er'iyyan,""kanu-nen,"or both. If the defendantconfessed, hatparticular asewill be left out ofthe sample.27. Elevenout of nineteen.28. Threeout of nineteen.29. Threeout of nineteen.30. Twoout of nineteen.31. Twelveout of thirty-one.32. Fourteenout of thirty-one.33. Fiveout of thirty-one.

160

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

8/25

Apostatesnd Bandits

tedly weighted toward a combination of seriat and the code. To a largeextent, however, religious and secularprinciples also remained more sepa-rate than they would in lateryears. er 'iideas dominated in the more abs-tract, philosophical areas of the law - such as proof and procedure - whe-reas the tenets contained in the more secular code dominated in morepractical areas, such as sentencing.The anecdotal evidence contained in a number of these cases bearsout the above conclusions. In a murder/treason (katl/fesad) case from1839-40, for example, a defendant on trial for both crimes is sentenced"by the requirements of ?eriat"34 to a harsh secular penalty (hard labor).The logical conclusion of such a decision is, first of all, that the defendantcannot be pardoned, as he could have been if sentenced only according tonizaml principles. Second, if any heirs appear and demand lex talionis(kisas),he can be immediately executed. Should the heirs forgive the mur-dereror demand blood money (diyet),contrarily,the government can stillkeep this particularthreat under wraps, since the sentence is a secularone.The state, in other words, has used ?er 'i ideology as a means of ensu-ring an execution - and the continuing execution - of the sentence, andnizami ideology as a means of retaining some jurisdiction over a treasoncase. We see here, in other words, a situation in which the secular and thereligious authorities work together to undercut the individual rights ofboth the accused and the heirs to the murder victim. There is no fightover jurisdiction here, instead there is the beginning of a totalization ofthe legal system. Indeed, this use of both philosophies does not in anyway mean that seriat was grossly misused. In a similar case just a fewmonths later, for example, in which an individual's sentence is under dis-pute, a point is made to keep the Seyhiilislam informed and effectivewithin the case. The religious establishment is therefore always on handto administer those partsof a case "related o murder and to common lawin the context of ?eriat." 5 Again, the two hierarchiesinteract above all toprotect their mutual interests.

34. iradeler MV 188, 8 L 1256. "bermiikteza-yl eriat..."35. iradeler MV 299, 11 S 1257. MV 299, 11 S 1257. "Meclis-iVila'yacelbile bi'l-istintak fadat-i vakialarizabt olunarakmadde-i katl ve hukuka dairmevaddber-nehc-i er'i riiyetolunmakizere huzur-ifetvapenahidemiimaileyhYahyaAga ile merkumOsmanve eghas-imerkumebi-t-terafumiimaileyhYahyaAga ikame-ibeyyineile isbat-imiiddeayamuktedirolamamasiylamuarazadanmen' ilamiverilmigve merkumlarin aklarinda ahibirgfina hiikm-i ?er'i ahikolamamlioldugundanmerkumlarin in-iistintakta aki'olanifadelerizerine ica-

161

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

9/25

Ruth A. MILLER

Two apostasy cases from 1841 and 1843 can also be analyzed as excel-lent anecdotal examples of an early merging of secular and religious prin-ciples during this period. The first appears among a number of murder,theft, brigandage, and treason cases tried in the Filibe area. 36 It notes that

bat-i kanuniye ve nizamiyenin icrasi hususuna dair Meclis-i Ahkam-i Adliye'denkaleme alinan bir kit'a mazbata mah-i Safer'iil hayr'in sekizinci garganbagiinuMeclis-i Umumi'de led'il-kira'amerkum muytabl Halil ber-mucib-i irade-i seniyebe? sene muddet igin kiirege vaz' olunmugoldugundan merkumun mUddet-i mez-kure tekmiline kadar kiirekde ibka[si]." "[They were] summoned to the Meclis-iValawhere they were interrogated and their statements were recorded. Then thecase [was moved to the offices of the] Seyhiilislam, who was present at the trial tosee those parts of it which related to murder and common law in the context ofseriat.The aforementioned YahyaAga and Osman, and the other people men-tioned above appealed mutually to the judge. YahyaAga could not exhibit proofto verify his claim. Thus a verdict of interdiction of dispute was pronounced anda report was prepared by the Council of Judicial Ordinances, which discussed thelegal measures to be applied in this case after taking into consideration the testi-monies of the aforementioned people. This report was read in the general coun-cil on Wednesday, the eighth day of the month of Safer. [In conclusion], it wasdecided that since the hair rope maker Halil had been sentenced to hard laborwith exile for a period of five years, he should continue serving this sentence untilthe end of the aforementioned period."36. iradeler - MV 294, 7 S 1257. "Ve bir kit'asinda dahi Bazarcik Kazasi ahali-sinden Yovan nam zimmi mukaddema haydudluk t6hmetiyle tutuldukta kabul-iislam etmig ise de bu defa miirted olmugve mersum dahi Dersaadet'e g6nderilmigoldugu beyanlyla iktizasini istizan ve canib-i fetvahaneden dahi merkumun uiibhe-si var ise ke?f olunarak iizerine islam arzolundukta kabulden imtina ile irtidadinaisrarederse?er'ankatli lazim gelecegi zahr-i ilama tahrirve beyan olunmu? olmak-la bu surette merkumun huzur-i hazret-i fetvapenahide istintaklyla utibhe ar isekeef ii hall olunarak ber-mikteza-yl ?er'-i ?erif merkuma islam arz olunup onuniizerine ne merkezde bulunur ise iktiza-yl?er'isini ilam eylemek iizere bu hususunba-buyuruldu-i sami istanbul Kadisi Faziletlu Efendi Hazretleri'ne havalesiicabindan oldugu." Another document states that a non-Muslim named Yovanfrom the district of Bazarcikhad converted to Islam upon being arrested on thecharge of banditry. He then, however, apostatized and was sent to Istanbul. Thedocument requests that the necessarymeasures be taken and states that if the offi-ce of the Seyhiilislam has doubts about this person, the necessary investigationshould be conducted and he should be interrogated. A marginal note is writtenon the back of the judicial decree stating that if he refuses to acknowledge that hewas a Muslim and insists upon his apostasy,he should be executed. Thus the afo-rementioned person should be interrogated at the office of the Seyhiilislam andall doubts should be removed. During this process, he should be asked if he is a

162

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

10/25

Apostatesand Bandits

a defendant, upon being arrested for banditry, converted to Islam, laterapostatized, and therefore, according to the requirements of ~eriat, oughtto be examined and interrogated by the office of the Seyhiilislam. If hepersists in his apostasy,the document continues, he ought to be executed.In any case, it concludes, both the Grand Vezir'sOffice and the Seyhiilis-lam must see the response before it is forwarded to the Istanbul Kadi, sothat both might have a say. Clearly, apostasy trumps banditry when itcomes to jurisdiction. At the same time, however, both temporal and divi-ne legal functionaries remain involved in the case, given that both theGrand Vezir's Office and the Seyhiilislam are to be kept informed.More interesting, and perhaps more to the point, a case from 1843"7concerns a defendant accused of blaspheming and acting against teriat, 8who, after having done so, is summoned to the Manastir council andasked to retract his statements. He does not, and is thereforeput into pri-son awaiting a response from Istanbul. The office of the Seyhiilislam sub-sequently issues a declaration stating that death siyaseten s legitimate -Muslim, as requiredby ?eriat, and his responseshould be forwarded o HisHonor,the Kadiof Istanbul,by the GrandVezir'sOffice fora judicialdecree.37. Iradeler MV 915, 7 S 1259. "Prlepe azasi akinlerinden eyzullah ampahsel-iyazubillahta'ali-ikiifriimii'eddibirtakimkelimat efevviihiine e hilaf-i er'-i ?erifrafiziyne harekatabtidaretmekteoldu_undankendisiManastir'a elbileher ne kadarkegf-i iibheedecekve itminan-ikalbhasilolacaksuretlenesayih-ilazima craolunmu?sede itikad-ibatilindanbirvechilerUicu'tmemekle uhur-u irade-iseniyeyekadarmerkummahbese lka.""AcertainFeyzullah, n inhabi-tant of the sub-province f Prlepedared,Heavens orefend, o utter some blas-phemouswords and hereticalactionsagainstPeriat.He was, therefore, ummo-ned to Manastir ndgiventhe necessary dvice o provide ranquility f heartandto removedoubts. Buthe did not retract t all his superstitious eliefsand there-fore he was put into prisonuntil the issuanceof an imperialdecree."siyasetenkatlimegrudfitiu anib-ifetvahanedenahr-1lamatahrir e inbaklllnml?...""Itis writtenand communicated n the judicialdecree ssuedby the fetvahane hathis punishment by death (siyasetenkath) is legitimate...""Meclis-iUmumi'dekira'atolunan bir kit'amazbatadastizanve i?'arvermeyipmazbataiktiza-yl?er'isinincrasimeclis-iumumidedahi bittezekkiirmenzur-u libuyurulmak

irin...""Amemorandum hat has been readat the generalcouncildoesnot requestan authorization nd makeanycommunication or the applica-tion of thenecessaryer i-measures.This memorandum as been discussed t thegrandcouncil in order o submit it to the Sultan."38. It is not absolutely lear n whatwaythe defendantblasphemed, ut the factthat his crimeis referredo as rafiziyanempliesthat he maybe a memberof theBektati dervish order.

163

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

11/25

RuthA.MILLER

drawing upon the temporal power of the Sultan (the siyas1authority) tosupport its case. The general council chooses not to request an authoriza-tion for the execution, but at the same time explicitly makes no commentabout the requirements of yeriat. The eventual fate of the defendant isnever made clear.The fact that the Seyhiilislam would even consider dra-wing the secular political authority into a case that ought to have beenpurely a religious one, however, is striking. Both of these cases indeedoffer clearevidence of the changes occurring in the Ottoman legal system- changes in which the jurisdictions of the temporal and the divine sys-tems are beginning to overlap. In the second, the Seyhiilislam calls for anexecution siyaseten or a blasphemer,whereas in the first, a bandit who hasapostatized is executed according to the requirements of ?eriat. Apostasyis no longer a crime simply against divine law, but an important elementin both systems. Banditry falls into multiple categories as well. Onceagain, what we see here, therefore, is a totalization of the legal system, inwhich the most important and most imminent threat is that to thestate/religious hierarchy and authority criminal threats to individuals areof little or no importance.

1851-1858Following the promulgation of the 1840 criminal code, and ten yearsof its application, a reinterpretationand expansion of this law was under-taken in 1851. Although this new code was undoubtedly an evolution inTanzimat era thinking and in the creation of a nizaml legal philosophy, italso incorporated far more ?er 'iconcepts into the body of its text than its1840 predecessorhad.3 When looking at the practical application of the

code, especially as evidenced by the cases tried, the same pattern holds.The procedure for bringing cases, it is true, remained more or less thesame in this period. The one exception of note was the spread of the localcouncil phenomenon and the circumscribing of the role of the governorsomewhat. As for the numerical distribution of legitimization, proof, andsentencing, however, there is an undeniable shift toward a predominanceof ?er ' influence.

Referringback to the table, out of a total of fifteen documents, inclu-ding twenty cases involving murder, wounding, and corruption, 62% 40

39. AhmedLiitfi,the 1840 and 1851 Codesbeginningon pp. 128 and 150 res-pectively.40. Eightout of thirteen.

164

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

12/25

Apostatesnd Bandits

contain ?er 'iwrits, and 39% 41do not. Further,35% 42arelegitimized uponSeriat, 12%43upon the code, 41% 4"upon both, and 12%45upon neither.As for the method of proof, it is difficult to establish a meaningful numberin this subsection, as only four of the casesmake specific referenceto proofof any kind. For the sake of uniformity, however, of these four, two refe-rence ?eriat and two the code. Finally,when looking at the sentences pas-sed, 57% 46 arereligious, 21%47aresecular,and 21%48are siyasi.It can be noted right away that, with respect to legitimization, ?er 'and nizami concepts continued to interact. Over the first chronologicalperiod, 35% of the cases referencedboth, and over the second period, thisnumber rose to 41%. At the same time, however, whereas before, theremaining cases looked to nizami concepts slightly more often than to?er'-concepts (30% nizami to 24% ?er 'i), in the later period, the oppo-site occurred (12% nizami and 35% yer i). The higher number of ?er 'twrits issued in support of these cases (62% of the cases in 1851-1858 rela-tive to 59% before) also indicates that ?eriat played a bit more of a rolein criminal law over this period than it had earlier. Finally, in the years1840-1850, secular sentences predominated among the three possibilities- 45% v. 39% ?er' v. 16% siyasi- whereas in the years 1851-1859, reli-gious sentences predominated - 57% v. 21% secular and 21% siyasi.The anecdotal evidence once again bears up these conclusions. Inthree corruption cases from 1852, 1853, and 1857, involving both naibs(religious judges) and local miidiirs (functionaries),4' for example, thelegal process proceeds as follows: the functionaries arefirst brought to thelocal council on corruption chargesas outlined in the 1851 criminal code.Reports are then sent to Istanbul, and reviewed by the central council.Following this initial review, the situation of the naibsis also examined bythe office of the Seyhiilislam. Finally,the central council decides upon thepunishment (banishment) for the miidiirs, in keeping with the criminalcode. Simultaneously, the office of the Seyhiilislam decides upon punish-

41. Fiveout of thirteen.42. Sixout of seventeen.43. Two out of seventeen.44. Sevenout of seventeen.45. Twoout of seventeen.46. Eightout of fourteen.47. Threeout of fourteen.48. Threeout of fourteen.49. Iradeler MV 16982,9 1274;MV 11568, 18S 1270;MV 11154,24 Za 1269.

165

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

13/25

RuthA. MILLER

ment (less severe banishment or dismissal) for the naibs, in keeping withthe spirit of the criminal code. What is therefore occurring in this laterdecade is again a blending of nizami and ?er i jurisdiction. The servantsof ?eriat are, especially upon first instance, subordinate to nizami admi-nistrative structures, but they are also still tied quite tightly to the tradi-tional institutional framework.The nizami law is by no means insignifi-cant in the realm of ?eriat, but neither does it in any way trump ?er 'Iauthority.The two instead work together, mutually supporting an expan-ding central authority.Two murder cases from this period that provoked the issue of generalstatements on the part of the legal authorities are evidence of a similarpattern. In a case from 1856, for instance, the question of jurisdiction andthe place of fer i and nizami courts became a pressing one, and so a decreeclarifying the issue at least for the province of Igkodrawas issued. In gene-ral, it stipulated that for all blood cases - murder and wounding - theheirs or the police would first appearin a court of arbitration (sulhcourt),so that it could be established without question that ?er 'ijurisdiction didnot override nizami jurisdiction. If it did, then the question of diyet (forwounding there was no other option) or kisas would be decided in thearbitration court. 50If it did not, only then would the case proceed tonizami jurisdiction. The self-conscious state interest in facilitating a niza-mi lawI/eriat integration goes almost without saying.In a similar manner, a case from 1851 5' describes a situation in whicha governor is investigated for issuing lashes to people convicted of various50. Iradeler MV 16180, GurreR 1273. "igkodraancagidahilindekatlve cerhmaddesindendolaylbilenlerindekan davasiolanlarumumenbaritlrilacaktireher bir katl igin katil tarafindanmaktulunvarsina ikibingurugdiyetverilecekmisilliicerhigindahimecriihiin erhineg6retensipolunacakbermebligmecru-he ita olunarakhuzur-uger'ide braolunacaklardire o babdabir kita cihet-i?er'iyyedahi tanzimve tahrirkilinacaktir. azalardahilindemevciid olan bumisilliikandavasibiladamuharrer lan vechilebarntlrilmak zerearafeynberat]evvel gkodra'yaelb ile icrayi cab-i hal itibarolunacaktir.gbumaslaha-yl mu-miyedensonravukubulacak afi-i katl ve cenabat-isaireyye er'anve kanunenriiyetolunduktan onratertipedecekceza her neysehiikumet-imarifetiylecraolunacagi ihetlehudbe hudolmaksiraslyla ususunu61diirmeyee cerhetmeyecerair denlerkatilve carihnazaretiyle akilacaktir.51. Iradeler MV 8340, 27 B 1268. "Rumelikit'asinin ksermahallerindeshab-Itohmetindarb le miicazatolunduklari eOskiipvalisidevletluTosunPagahaz-retleridahi?unubunudarbetmekteoldugu fadesiyleSilistreValisidevletlupagahazretleri arafindan aridolan tahriratMeclis-iVal 'nin mazbatasiyla eraber

166

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

14/25

ApostatesndBandits

crimes committed under his authority.The document goes on to say thatthis sort of punishment is "contrary o the Tanzimat,"and that "fromnowon, accused individuals - aside from those to be punished by the applica-tion of ?er ' punishment - should not be beaten, but sentenced to hardlabor and imprisonment according to the legal code."52In other words, ifanyone's jurisdiction is being curtailed over this period it is that of thelocal authority. Nizami punishments are fine, yer 'ipunishments are fine,combinations thereof encouraged, but arbitrarypunishment on the partof the local governor is absolutely not fine, and must be curtailed. As theincorporation of fer 'iprocedure occurred, it seems, a simultaneous appli-cation of centralizing measures was also being undertaken. It might alsobe noted here that as the religious and secular legal systems worked toge-ther to support the new system, this system was in no way becoming lessviolent or more liberal- all that was occurring was a strengthening of thecentral authority and the co-opting of traditional institutions as its pillars.

1859-1876The period 1859-1876 begins with the promulgation of a code inspi-red by the Napoleonic French criminal law. With this code, a movementaway from the ?eriat predominance represented by the 1851 code andtoward a more completely interactive nizamil/er ' legal philosophy occur-red. As one might expect, a selection of cases from the 1859-1876 periodconsequently reveals an interest on the part of Ottoman legal functiona-ries in putting into practice this newly formulated philosophy. Thereexists in these cases, for example, many more self-conscious references tospecific articles of the new code, as well as to Tanzimat philosophies suchas the preservation of "irz and namus"(honor - of two kinds). Of greatermanzur-ialibuyurulmakqiintakdimkilindi.Mealindenmiisteban lduguvechi-le badezinhad-i?er'i azimgeleneshab-it6hmettenma'ada6yledarbettirilmeyipber-mucib-ikanun-icezaprangave habs ile miicazatolunmalari...""Adispatchsent by His Excellency he governorof Silistrastating that in many partsofRumeliaaccused ndividuals avebeenpunishedby beatings,andthat the gover-norof (Iskiip,His ExcellencyTosunPapa,hasbeenbeatingvarious ndividualsssubmittedalongwith a Meclis-iVaIl memorandum on thissubject].Given thecontentsof this memorandum, rom now on, accused ndividuals asidefromthose to be punishedbythe application f er ipunishment should not be bea-ten, butsentenced o hard aborandimprisonment ccording o the legalcode."52. "Tanzimat-ihayriyeninmugayiri," hadd-i eriat azimgeleneshab-it6hmet-ten ma'adasinin yle darbettirilmeyipbermucib-ikanun-icezaprangave habisile miicazatolunmalari..."

167

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

15/25

Ruth .MILLER

interest,however,we alsoseea hugeleapin the numberof cases hatrelyupon the combinedsupportof both Tanzimat deasand the moretradi-tional1er?'philosophy.Granted, he procedure or decidingthesecasesgets virtuallyno attentionin the text of these documents, 5but whencomparing he numericaldistributionof legitimization,proof,and sen-tencingto the distribution een in the earlierperiods,the patternthatdevelops s quitestriking.Referringnceagain o theabove able,withinasampleof fifteendocu-ments,containing wenty-five asesof murder, heft,and corruption,orinstance, ne findsthat47% 4containSeriwritsand53%5do not.As forlegitimization, 6% 6arebytherequirementsf seriatlone,19%57 rebythe requirementsf thecodealone,62%58arelegitimized ponboth,and4%59are legitimizedupon neither.Moreover,when one looks at themethod of proof,29% 0 aretriedby the rulesof seriat,29%6' aretriedaccordingo the precepts f thecode,and41% 2 followa combination fthe two. Finally,as for the sentencespassed,20%63 areSer sentences,76%6 aresentencesromthecode,and4% 6aresiyasi entences.In otherwords,yes,we cansee herea definitedrop n the useof seriatalonein determining ndlegitimizing ases.But, in theareasof legitimi-zationandproof,this dropdoesnot necessarilyoincidewith a simulta-neousrisein the use of nizami egitimization nd proof.In fact,a com-parisonof the 1859-1876 datawith the 1840-1850 data in particularyieldsa quite differentpicture.Whereas n the earlierperiod,the codealonewasusedto legitimizecases30%of the time, in the laterperiod twasusedonly 19%of the time.In addition,although he useof the codeon itsown in provingcasesrosefrom16%to 29%overthe sameperiod,the useof?eriatalonein provingcasesalsooccurred xactly29%of the53.Asitdidearliernwhen henizamiystemwas irstbeingnstitutionalized.54.Seven utof fifteen.55.Eight utof fifteen.56.Four ut of twenty-six.57.Fiveoutof twenty-six.58. Sixteen utof twenty-six.59.Oneout of twenty-six.60. Fiveoutofseventeen.61. Fiveoutof seventeen.62. Seven utofseventeen.63. Fiveoutof twenty-five.64.Nineteen ut of twenty-five.65. Oneout of twenty-five.168

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

16/25

Apostatesnd Bandits

time. The area, therefore, in which the greatest numerical rise regardingthe legitimization and proof of cases occurred is the "combined" subsec-tion. Over time, the use of eriat and the code together to legitimize casesrose from 35% to 41% to 62%, indicating a cleartendency toward a mer-ging of practice in this area. A similar rise in the "combined"method ofproof also occurred - from 16% to 41%. The one area, in fact, where thenizami elements of the code alone began to hold sway was in the senten-cing of cases. With a change over time from 45% to 21% to 76%, we candefinitely conclude that following the ten year long readjustment towardseriatin the years 1851-1858, the nizami system did in fact gain predo-minance over the ?er 'isystem in criminal sentencing. 66Given the fact thatthese sentences were so completely reliant upon the merged yer'/Inizamisystem for legitimization, proof, and procedure, however, it is difficult toargue that these numbers alone can account for some sort of overalltriumph of nizami practice.The anecdotal evidence in this final period bears up the above fin-dings. A document from the year 1873, 67for example, describes a situa-66. Although t oughtto be noted that the Perisentencingdid not actuallydropto anyhuge degreebetween1840 and 1876:from39%to 20%.67. iradeler MM 2028, 19 R 1290. "Prlepe ilayetiahalisinin kserihu_unetvecehaletleri ktizasincamin-el-kadimbirbirinikatl ve cerh etmekve hetk-i irzvenamus eylemek gibi cinayatl i'tiyat ederek ve bu fi'illerin ilca'at ve icbaratlylayekdigerlerindenhz-iintikam &inkandavasina iigerek uda'iye-ivahiyemiya-nelerinde miiteselsil ve miitevaris ve enva' vuku'at-i feci'ayabais olmakta oldugunave egerqi gbu allerdenmiinb'aisdavalar ralarca anbarintlrmaksmiyle ttihazolunanbir kaide-isulhiyedairesindeesviyeedilmekte se de bu kaidezatengayr-1megru' e silver-i craiyesibir takimsebiikmagzan esaninara-ylhodseranesinemevdu' olmaslyla onun devami efal-i cinaiye miitecasirlerinin ahkam-i adile-iger'iyeve kanuniyeden istisnasini mijeddi ve tekerriir-i vuku'at-i muzirraya badiolaraksinuf-i teba'aarasindamuhasematve mukatelatinhudus ve temadisi semin-kiill'il-viicuhtecviz olunamaycaglnamebni buna bir nihayet verilmesivilayet-i mezbure valisi devletlu paga hazretlerineyazilmli idi. 01 babdakitegebbiisattanahislemebhus-ianha olanve mahallinceLek?Dukagjininamlylausul-i mahsusa hiikmiinde tutulan kaide-i sulhiye ba'dezin kiilliyen men' ve ilgaolunarak katl ve cerh davalarininhiikm-i er' ve kanuna tatbikan riiyeti hakkinda?edid'iil-miifad irklut'aerman-1mehabet-nizansdarve tesyarivali-imiigarileyhtarafindang'ar dilmig." Fromdaysof old, themajority f the inhabitants f theprovinceof Prlepehavebeenaccustomed o committingsuchcrimesas theviola-tion of honor and rape,becauseof their roughnessand ignorance.These actscompel and oblige individuals to undertake blood feuds with one another for thesake of revenge, and this silly motive has been causing all sorts of successive and

169

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

17/25

RuthA. MILLER

tion in which the Albanian population of Prlepe is persisting in its adhe-rence to a local form of judgment and sentencing. The document notesthat this sort of local jurisdiction is contrary to both yeriat and the code,and that the local authorities must stop it. In the end, an imperial decreeis requested - a decree which will explicitly carry the force of law andunderline the overriding jurisdiction of both the divine and the temporal[central] legal systems in this unstable area. Once more, therefore, we seea situation in which ?eriat and secularlaw are of equal rhetoricaland poli-tical importance - each of them supports the other, and each is also sup-ported by and supports the central authority.It is likewise in this last period that the Ottoman government beginsa systematization of the law on a largerscale. By the 1870s, for example,generic forms to record the testimony of witnesses in both ?er '" nd niza-mi cases came into use, and cross examinations in trials had to follow aspecific, authorized procedure. By producing these forms, however, itcannot be argued that the government was attempting to marginalize?er 'authority and encourage the growth of nizami authority in its place.Quite the contrary: by including ver'icases within this systematization ofthe law, the place of fer 'iprinciples within the new modernizing legal fra-mework was if anything reassured. Finally, although it is not hugelyimportant, it is somewhat significant that with cases in this period onealso begins to see the emergence of a new formula "by a nizami investi-gation and by a er ' trial,"6 appearing at the end of most serious murdercases, further evidence of the merging of the two practices.ongoing tragic ncidentsamongthesepeople.Such caseshave been settledaccor-ding to a customarypeace-making ule therecalled blood reconciliation.Thisrule,however,s essentially nlawful,anditsexecution s left in the handsof a fewobstinateandsillypeople.Inaddition, he continuationof thispracticewill allowthose who venture o commit criminalactsto escape romthe application f thejustjudgmentsof the?eriatand law. Since thedevelopment ndcontinuationofmutual hostilitiesbetweensubjectsand the killingscannot be permitted,a dis-patchhas been sent to the paga,the governorof the aforementioned rovince,requestinghathe putanend to thispractice.The aforementioned agahas com-municateda messagedetailinghis effortstoward his end and has requested heissuanceof an awe-inspiringmperialdecreewith strong languageand carryingweightas law,which mightpermanently bolishand annul this practice, ocallyknown as [kanuni ] Lek?Dukagjini,and placemurderand assaultcaseshence-forthunderthejurisdiction f seriatandlaw."68. "Tahkikat/tedkikat-iizamiyye e miirafa'a-yler'iyye. ."cf forexample, ra-deler- DAA 577, and DAA296.

170

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

18/25

Apostatesnd Bandits

1877-1908No new criminal code was promulgated in 1876-77, but a newConstitution was, and with it, certain changes occurred in Ottoman cri-minal law as well. By 1877, for instance, the nizami court system hadbeen established and set up as effectively as it was going to be throughoutthe Empire. As a result, the general procedure for coming to a conclusionin a case was set in place. Startingwith the cases in 1877, therefore,atten-tion begins to be paid once more to the sequence of courts and councilsin which a case would be heard. In this later period, first of all, the prin-

cipals of a case or the police would bring their issue either to a civil courtof first instance or to a ger I'court. If the case was sent to a first instancecourt and turned out to be within ser i jurisdiction, it was then sent tothe local ser i court. If not, it could be appealed to an appeals court ordecided and sent to the central Council. From the Council, a case couldeither be confirmed and sent to the Justice Ministry, confirmed, sent tothe office of the Seyhiilislam for a ?er 'Iconfirmation, and then sent to theJustice Ministry, or not confirmed and sent for appeal once again to thecassation court. If the case went originally to a local ?er 'i court, a reportwas sent straight to the office of the Seyhiilislam, confirmed by theCouncil, and then sent to the Justice Ministry.6'The above sequence of events diverges quite radically from thesequence we noted above, common between 1840 and the 1850s. In theearlier period, although there was a great deal of ?er 'inizami interactionon the local level, with the councils and governors hearing both types ofcases, at the higher level, things remained to a largeextent separate.In thislater period, the nizami and yer 'I urisdictions at the local level appear tohave become slightly more separate than before. 70 At the higher level,however, different authorities interacted with far more frequency. Theoffice of the Seyhiilislam, the Council, and the Justice Ministry, forexample, had overlapping jurisdiction over many cases, and if the proce-dure described in the documents is any indication, they all worked toge-69. See docs. AM: 1319-M-18/8; 1319-C-4/5; 1320-Ca-18/9; 1305-Ra-25;1310-S-9/3;DAA:834, 825. And alsoBayraktar,. 320: "suivantl'article remierdu dit code [de 1858] ceux qui sont condemn&s arles tribunauxde Nizamiyedoiventetrejugesensuitepar es tribunaux e ?er'iye." followinghe firstarticleof the abovementioned[1858] code, those who were condemnedby the nizamitribunalshaveto bejudgedafterward y the?er'i ribunals."70. Althoughnot to a hugeextent,giventhat theyertcourt andthe first nstan-ce courtwere often one and the sameentity.

171

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

19/25

RuthA. MILLER

ther in seeing to it that the outcome of each serious case brought to theirattention conformed to all three of their respective theoretical underpin-nings - be they yer 'I,nizami, or both.

Unfortunately, from the year 1878 onward, the presence of specificcourt cases listed in the irade archival catalogues dwindles quite rapidly.In the end, it appearsthat only the most major cases, or major exceptionsto the norm were included among the other documents. Although it ispossible, therefore, to describe in an impressionistic manner the sequen-ce in which a case was heard, conducting a numerical analysis upon sucha small pool would be unlikely to furnish meaningful results. The tableearlier in this section consequently ends with the period 1859-1876 anddoes not attempt to examine later sets of cases.

APPOINTMENTSPerhapshemost elling rean which heincorporationf?er ipre-cepts nto the nizami dministrationecomes pparents thetrendsnappointmentso criminal ourtsand to legalreform ommittees.heindividuals ho madeupthesecourts ndcouncils,heways n whichthese unctionariesere ransferredrappointedo them,and n parti-cularhereasons ehind hetransfersndappointments,lldemonstratethatas timepassed,headministrationf the Ottomanegal ystemwasbecomingmoreandmore compositef nizaml nd?er"omponentsnsupport of a largerauthoritariansystem.Firstof all,prior o its division nto legislative ndjudicial ections n1868,the centraludicial ouncil, heMeclis-iVdld-yzhkam-i dliye,wascomposedtitshighestevelnotonlyof nizami ndcivil unctiona-ries,but of both?er'udges ndcivil unctionaries.Thisdivision orlack hereof shows learlyhe extent o whicha separationf thetwo

systems was not in any way the goal behind Ottoman legal reform.

71. SavvasPasha,Le tribunalmusulman.Paris:Mechal et Billard,1902. p. 76,"Unecour,nommeConseilSupremede justice(meclis-ivalai-iadliye[sic])com-poses:10de personnages rrives uxplushautesgradesde la hidrarchie esjugeset jurisconsultes e l'ordresacrd20 de dignitaires ivilsdu plus haut rang..." "acourt, called the SupremeCouncil of Justiceconsistedof: 1) people from thehighest evelsof the hierarchy f judgesandjurisconsultantsf the sacredorder,2) of civildignitaries f the highestrank..."

172

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

20/25

Apostatesnd Bandits

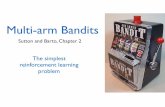

Moreover, we ought to note that at their earliest stages, the first proto-nizami courts were provincial councils instituted by the 1864 (1281) lawof vilayets - courts which were composed of a ser i judge president andonly then of a council of Muslim and non-Muslim functionaries and offi-cials.72By so noting, we can conclude that separation as such, even at thebeginning, had never been considered. But once again, by far the mostimportant information on this issue comes from an analysis of the admi-nistrative appointments themselves.A basic examination of the proportion of ulema corps members tocivil bureaucratic functionaries appointed to criminal court positionsreveals a distinct lack of discrimination against the former. Indeed, thepreference seems to have been for ulema to fill these positions. Given asample of approximately 265 appointments and transfers containedwithin 100 documents covering the years 1861-1908, for example, wefind that over the entire period, on average, 62% of the appointments tonizami criminal court positions went to ulema, 30% went to civil func-tionaries not attached to the ulema corps, and 8% went to non-Muslimjudges. In general, as the table73 below indicates, these averagesdo notchange all that drasticallyover time:9080. /0

508 27 87 Efend8

40- __, / ---,------ Bey '.40. --? Minony

0 . ---- ---1861-2 1872 1875.6 1880 1882 1886 8 1894 6 19058

72. A. Heidborn,Manuel de droitpublic et administratif e l'empire ttoman.Vienna:C.W.Stern,1908. p. 223. "...composesdejugedu ch'riat (naib)commepresident t d'assesseursparmoitidmusulmans t non-musulmans."73. This graph s composedof information ound in the followingdocuments.Dahiliye: 1402, 1836, 32168, 39013, 41072, 43291, 40072, 40040, 40067,40870, 40840, 45005, 45893, 45932, 45448, 45587, 46008, 46152, 46253,46700, 47122, 46945, 47443, 4991, 47366, 48866, 50612, 50508, 60705,63291, 64263, 64444, 64161, 63583, 63712, 64080, 64631, 64690, 64700,66797, 66449, 66568, 65875, 65163, 65164, 67692, 67997, 67832, 68860,69323, 68783, 68124, 68459, 68006, 69394, 69718, 71287, 71404, 69857,69573, 69442, 72036, 81477, 85244, 84119, 82674, 83461, 84989, 86560,

173

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

21/25

RuthA. MILLER

The above table does not follow a uniform timeline on the x-axis, butwe can nonetheless see that aside from two dates - 1876 and 1882 - thepercentage of ulema appointments to nizami criminal courts remainedconsistently higher over the forty-seven year period than the percentageof civil servant appointments. Indeed, aside from the six-year period bet-ween 1876 and 1882, the pattern of all three remained relatively calm,with a complete drop in non-Muslim appointments after 1898. Clearly,it seems, ulema appointments to nizami criminal courts were never fazedout, even at the very end of the Ottoman period.After dividing the 265 appointments into chronological sections -1859-1876, 1877-1890, and 1891-1909 - and analyzing the immediatebackgrounds of the individuals appointed during these periods, an equal-ly intriguing pattern emerges. In the earliest years, those appointed fromcompletely outside of the legal system - that is, for example, from gover-norships, 74 rom the Finance Ministry," or from the office of telegraphsand post, 76- made up a relativelylarge proportion of the total number ofappointments: 38%. By the years 1877-1890, this number had droppedto 4%, and by the final period, 1891-1909, appointments from outsideof the system constituted only 2% of the total. We can consequently spe-culate that during the earlier period, when the nizami system was firstbeing articulated, an attempt was in fact made to create a legal hierarchyseparatefrom what already existed, philosophically attached, perhaps, tothe more temporal civil bureaucracy.As occurred earlierwith the evolu-tion of cases, however, it seems that with the evolution of administrativeappointments as well, an overall tendency subsequently developed in thelater years favoring an integrated legal system. This legal system, as onemight expect, involved the use of internally trained functionaries, and wasnot to any large degree reliant upon the civil bureaucracyfor its adminis-trative foundation.

To bear out such a hypothesis, over the same time period the percen-tage of appointments from criminal law positions to other criminal law

98813, 99860, 100466, 100367, 95480, 95149, 99204; MV: 16306, 7948,9397, 25790; MM: 1557, 1817, 1819, 1943;AM: 1312-C-11/310, 1313-S-5/5,1313-M-18/10, 1313-C-23/2, 1314-$-12/8, 1314-?-12/11, 1316-N-29/7,1316-R-20/11, 1316-Za-9/8, 1323-S-24/4, 1325-R-5/17, 1325-B-1321.74. For example n iradeler,Dahiliye45932, 20 C 1289 or iradeler,Meclis-iMahsus1819, 2 S 1872.75. Forexample n iradeler,Dahiliye40840 26 ? 1285.76. Forexample n Iradeler,Dahiliye46008 9 Za 1289.

174

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

22/25

ApostatesndBandits

positions77went from 38% to 62% to 81% of the total. At the same time,the percentage of appointments from civil or commercial law positions tocriminal law positions underwent a less steady change, from 24% to 33%to 17% of the total. As the specialization described above was occurring,therefore, it seems that a similar move toward specialization within thelaw was simultaneously undertaken. By the final period, someone alreadyversed in criminal law was far more likely to be appointed to a criminallaw position than someone whose experience was grounded primarily inthe civil or commercial branches of the system. At the same time, bearingin mind that on average 62% of the criminal law appointments weremembers of the ulema corps, this tendency does not preclude the repea-ted appointment of ?er 'Ispecialists to these positions.The reasoning advanced in the documents to justify appointments ortransfers also appears to point to an interest in a balanced nizamilyer 'isystem with a specialized focus. With each appointment, one of a varie-ty of justifications is given for the placement and transfer of the indivi-dual to a certain position. These justifications include, for example, thecreation of a new opening or the resignation, death, dismissal, or trans-fer of the previous office holder. Given the variety of reasons advancedfor the appointments, a control can be used to test the validity of anumerical analysis of the information contained in the documents. Wewould not expect a drastic change to occur over time in the proportionof deaths or even perhaps resignations to the other openings. Indeed, ifthe numbers were to change dramatically over the three periods, theywould cast doubt on the validity of all of the other information available.As it is, however, the number of deaths relative to the total number ofopenings remains at a constant 7%, 6%, and 6% over the three periods,and the number of resignations remains equally constant at 2%, 4%, and4%. We can be relatively certain, therefore, that the other numbers andthe patterns to which they point are to some extent meaningful.The most interesting change over time occurs in the relationship bet-ween those appointments which would take over positions vacated bysimple transfers and those appointments which would take over positionsvacated by dismissals - the latter often accompanied by a prosecution ofthe former official. During the earliest period, 1859-1876, 56% of theappointments occurred after simple transfers,whereas 5% occurred as aresult of the previous functionary's dismissal. By the years 1877-1890,77. Thatis, criminal awappointmentswhichhad no backgroundn the civilandcommercial spectsof the nizamisystem.

175

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

23/25

RuthA. MILLER

this proportion had shifted to 44% as a result of simple transferand 26%because of dismissal. By the third period, the numbers were equal, and37% of new functionaries filled positions vacated by transfers,and ano-ther 37% filled positions vacated after a dismissal and/or prosecution.What does this gradual rise in dismissals mean? As has been the case upuntil now, it would seem that as the ?er 'isystem became more and moreintegrated into the nizami system, there was a simultaneous exertion of astricter state guidance over the administration of the whole. In otherwords, the legal system which was developing was one in which the statemaintained complete control over the administration and the activities ofthe functionaries, but in which these functionaries and the philosophiesto which they adhered operated in much the same way as they had befo-re. Indeed, it is probably not an accident that of the eighteen positionsopened up by dismissals in the final period, all but two were taken overby members of the ulema corps.

Anecdotally, we can see the same patterns occurring. A documentfrom 1868, for example, attempts explicitly to fill clericalpositions withinthe Council of Judicial Ordinances with an equal number of ulema func-tionaries and secretaries rom the civil bureaucracy. 8A year later,in 1869,the composition of the central nizami courts in the provinces of Selanikand Sivasis discussed "for reasons of reform."In the end it is decided that,among other changes, the High Court and the Council of Cassation willbe attached to one another, and that the former will include a presidentappointed by the state as well as locally appointed members who knowthe nizami laws and regulations. In addition, this high court "will hearmurder cases that took place in the central sancakof a province as a firstinstance court and, along with the justice councils and er 'Icourts, it willsee, as an appeals court, upon request, [criminal cases] that took place inthe capital of the province and in the districts attached to it."79The above

78. Iradeler,Dahiliye40040 12 M 1285. "Divan-iAhkam-iAdliye'ninmazbata-larinisuret-imatlubedekalemealmakigiintarik-i lmiyyeve kalemiyyeden n ikinefermiisevvid ntihapve tayinolunmak...""inorderto pen the reportsof theDivan-iAhkam-zAdliyen the desiredmanner,12 secretariesrom the ulemaandclerical taffwill be chosenandappointed..."79. "Mahkeme-i ebire-imerkeziyyeninegkilicihetledivan-i emyiz-ivilayetbit-tabi ona mUlhak e munzamolacaktir" nd"makeme-i ebire-imerkeziyyemer-kez-ivilayetolan sancakdahilindevuku'agelen cinayetdavalarini idayetenvegerekmiilhakkazalarmecalis-ideavisinde e deavi-i er'iyedenbagka larakkabil-i istinaf olmakiizerehiikm olunan davalaristidaiizerine stinafenriiyeteder."

176

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

24/25

Apostatesnd Bandits

decision would not be of great interest to this argument were it not forthe fact that the central High Court is seen as only one of three entities -and the only one without a direct tie to the office of the Seyhiilislam -having jurisdiction over criminal cases. Moreover, the presidencies of thecentral provincial cassation councils, especially as of 1873, were all heldby ?er ' naibs, 80 thus intermingling the two systems even further. Toconfirm that this particulardocument was not an exception to the rule, asecond document from 1873 reinforces the need for members of theulema corps to fill these cassation council positions, noting that as longas the presidencies of the cassation councils are in force, they will beappointed to members of the ulema hierarchy. 1Throughout later years, the same tendencies occur. In 1881, forexample, membership to the high central cassation court is discussed. Inthis situation once again, the preferred profile for membership is an indi-vidual who has been involved in both nizami and yer 'i activities in thepast - that is, an individual who has been a member of the ?er ' investi-gation council, the Mecelle Cemiyeti(Mecelle Committee) and also a tea-cher at the civil Law School. 12 In a similar manner, as noted earlier, in"upon heformation f thecentralhighcourt,thedivan-itemyiz f a provincewillnaturally e attachedand appended o it." and "Thecentralhigh courtwill hearmurder ases hat took place n the central ancakof a province s a first nstancecourt and in additionto the justicecouncilsand?er tcourts,it will hear,as anappeals ourt,upon request, criminal ases]that tookplacein the capitalof theprovince nd in the districts ttached o it."iradeler,Dahiliye45362, 17 N 1289.80. Iradeler,Meclis-i Mahsus1943 5 S 1290, "... fakatriyasetlerinmerkeznai-blerine tefviziyleonlarinyerine dahi birer bab naibi tayini tertibat... divan-itemyizlerin ezaifi seyalnizvilayetcemehakim-i airedeg6riilendeavi-ihukukiyeve cinaiyenin stinafenveyatedkikenriiyetisuretine... divanriyasetine akledi-lerekyerlerinedigernaibtayinkilinmakiizere... ""with he handingoverof thepresidencies o the centralnaibs other bab naibs[will be] appointedin theirplace... theonlyassignment f the divan-i emyiz s to hear hecommon aw andcriminalcaseswhich wereheardat otherprovincial ourtsas an appeals ourt or[to function]as an investigativecouncil]... thoselocal naibswhosecompetencyis provenby experience nddocumentedwill be transferredo the presidency fthe divanand othernaibswill be appointed o their[former]positions."81. iradeler,Dahiliye46700 5 Ca 1290, "vilayetlerdekiivan-i emyizriyasetleri-nin tebeddiiliivukubuldukgaarik-i lmiyyemensubatindanhl ve erbabina ev-cihi... " "whenpresidencies f the provincial assationcouncilsbecomevacant,theywill be conferred o membersof the ulemacorps... "82. iradeler,Dahiliye67692 9 M 1299, "... meclis-i edkikat-ier'iye le meclis-icemiyetiazasindan e Mekteb-iHukukmuallimlerindenlupmalumat e ehliyeti

177

-

7/29/2019 Miller-Apostates and Bandits

25/25

RuthA. MILLER

1887, the central cassation court president and Mecelle commissioner,Ahmet Hilmi Efendi fell ill, and the open position went not to any civilfunctionary of the nizami system, but to Omer Hilmi Efendi, a formerinvestigator at the Imperial Foundations Ministry - a position whichcould not be more central to ?er 'i philosophy. 83What we can observewith this anecdotal evidence, therefore, is exactly what we might expectfrom the numerical analysis above: as has been the case up until now,there is no marginalization or destruction of the supposedly more tradi-tional ?er i system, merely an incorporation of its administration into thechanging nizami whole.

CONCLUSIONThisincorporationfthereligiousstablishmentntothesecularra-mework,owever,ad mplicationshichwouldbecomeullyclear nlyinthe20th entury. hmetHilmiEfendi,OmerHilmiEfendi, nd heircompatriotsn the officeof theSeyhiilislam aynot haveseen theirinfluence ecrease indeedheymayhavebecomemorepowerfulhantheyhadbeenbefore butneitherwas helegalenvironmentnwhichthey were operating in the nineteenth century a continuation of the clas-sical environment of years past. By the time the Ottoman Empire dis-solved, the stage had instead been set for a new and totalizing criminallaw system in Turkey,represented by Mussolini's criminal code. 84And inthis new system, religious and secular, conservative and reforming, tra-ditional and modern would all act as pillars for an overriding state autho-

rity unlike any which had come before.Ruth A. MILLER

(University of Massachusetts, Boston)

miicerreblanAbdiilsettar fendi'ninmahkeme-imezkure zalignatayiniyle..."83. iradeler,Dahiliye 85244 18 L 1305, "...yerine iktidarve ehliyeti cihetleMecelleCemiyetiazasindanabikanfetvaeminive halaEvkaf-1Hiimayunmiifet-tigi faziletlu Omer Hilmi Efendi Hazretlerinin ayini..." See also iradeler,Dahiliye84989 9 R 1305, whichdiscusses he sameappointment.84. SeeTurkey,CodePMnal.onstantinople:.A.Rizzo,1939. Italy,PenalCodeoftheKingdom f Italy,asApproved yRoyalDecreeof October9, 1930. London:HM StationeryOffice, 1931.