Vietnam Studies The Role of Military Intelligence, 1965-1967

Military Review July 1967

Transcript of Military Review July 1967

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

1/116

..e ----.... ....

I d

Itt This Issue

*Strategic Mobility~ Military Managers~ RegionalWar Strategy

I I J U I-. Ju l y 6 7

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

2/116

UNITED STATESARMY COMMANOAND GENERALSTAFF COLLEGE, FORT LUVENWORTH, RANSAS

COMMANDANT Major general Michael S. DavisonASSISTANT COMMANDANT

Brigadier General Robert C. Taber

The Military Review is published by the United States Army Command and General IStaff College in close association with the United States Army War College. It provides a Iforum for the expression of military thought on national and military strategy, nationalsecurity affairs, and on doctrine with emphasis at the division and higher levels of command.

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

3/116

Military ReviewProfessional Journal of the US Army

Regional War St rat egy in t he 1970s . . . . LTC Joseph K. Bratt on, USA 3A Nati onal Securi ty Corps . . . . . . . . . LTC Irvin M. Kent , USA 11How New Is Limi ted War? . . . . . . . . . . Charles A, Lofgren 16St rat egic M obit i t y 1967-80 . . . . . . LTC George D. Eggers, Jr., USA 24New Soviet Defense Mi nister . . . , . . . . . . Harr iet Fast Scot t 33Soviet Armed Forc es at M idc ent rrry . . COL GEN V. F. Tolubk o, Soviet Army 37Mi l i ta ry Managers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Rober t D. Miewald 40St rat egy Defi ned . , . , . .. . . BG Arnaldo t iacalone, I tal ian Army 48Service Li f e in 1976 . . . . . . BRIG G. S. Heathcote, British Army, Ret 50The Case f or t he Defense . , . . MAJ N. A. Shackleton, Canadian Army 58Israel s Nahal Corps . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Leo Heiman 65The M ananas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Loui s M ort on 71Sive Up-ft s ~ood f or You . . . . . . . CDR Jarl J. Dif f endorfer, USN 83Systems Analysi s i n t he ArmY . . . . . . COL Joseph P. DWezo, USAR 89Mao s 10 Pr inc ip l es o f War . . . . . . . . . . . . . Kenm in HO 96M i l i t ary Not es . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99M i f i t ary Book s . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

The VIEWS expressed in this ma esine ARE THE AUTHORS and not necessarily those of theUS Army or the Command and Genera Staff College.

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

4/116

Editor in ChiefCOL Donald J. Delanay ._Associate Editor

COL George S. PappasArmy War College

Assistant EditorLTC A. Leroy CoveyFeatures Edit orLTC Charles A. GatzkaProduction EditorHelen M. Hall Spanish-American EditorMAJ Juan Horta-Merly ~Brazilian Editors

LTC Paulo A. F. VianaLTC Samuel T. T. PrimoPublication OfficerLTC Edward A. PurcellArt and DesignCharlea A. Moore

Donald L. Thomas

MILITARY REVIEW-Published monthly by the U. S. Arm Command and General Stsff College,. Fort Leavenworth, Kanaaa in En@sh, apanish, and Portu uese. se of funds for rinf ing of this publ ication hasbeen approved by Headquarters, Department ofaitha Army, 28 May 1C&sacomhlsas postage rid at Fort Leavenworth, ICarreas..%bscriptkm rates $400 (US currency) ayear in the United states, rdted Sfatae mili tary post offices, and those countries which ars mambars oftha Pan-Amerisan Postal Union (including SPSinh $S.00 a yaw in all othar oounfr ieai eingle copy price50 cents. Addraea evbsmipfion mail to the Gook Department, U. S. Army Command and General WICollege, Fort Leavenworth, Ifansaa 68027.

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

5/116

THE LEAVENWORTH TIE-. .

vTe US Army Command and GeneralStaff College has adopted an officialneckt ie symbolizing the fi ne tradit ionsof the College. The Leavenworth Tieis al l s i lk, dark blue in c o lor ,and hasa small Lamp of Learning embroideredin gold. The blue and the gold are fromt he College cr est as is t he Lamp ofLearning which represents the knowl.edge acquired at the Command andGeneral Staff College.

The tie has been authorized for off-duty wear byo Members of the staff and

facu l ty .. St uden t s at t endi ng a USACGSC

course leading to a diploma or certi fica te .

. Any indivi dual who has earned,

a USACGSC dipl oma by ei t her res identor nonresident instruction.

The tie is available at the CollegeBook Store for $S.75 or $4.00 by mail.

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

6/116

.,,

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

7/116

......

\RegionalWar Strategyin the 1970sLieutenant Colonel Joseph K. Bratton, United States Armg!

The views ezpres.red in thisarticle a re the authors and are notneeewarilg those of the Departnwntof the Ar-mg, Department of Defeuse, or the US Armg Commandawd GeneraJ Staff College.Editor.

THE United States ap.A preaches the crit ical dseade ofthe 1970s, the worldwide etruggle forpow er w hich ha s oversha dow ed thea spira t ion of 20th -centur y ma n ma yaccelerate to unpr ecedented intensity.Militant communism will remain theprincipal threat , and instabilit iesca usa d by uphaa vals in t he emerging,nations, population expansion, aggressive na tiona lism, a nd n uclear pro

July1967 3

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

8/116

~@lONAL WAR ,0TRATE6YIiferat ion may increase tensionsthroughout the world .Internat ionally , the threat or application of military strength will bethe moat important operat ive powerfa ctor. On th e oth er hind, milita rypower will be employed more frequent ly in i ta threa tening role in support of policy th a n in ita a ct ive opera tional role.Threat and ChallangaIn form, the Communist threat wil lnot cha nge great ly . The idea of w a r a sa continuation of political intercoursewill be the essence of Communisttheory and practice. The overridingdanger o f genera l war wi l l remain aswill the possibility of regional wars.It is in the periphera l a rea e, however,that the greatest danger of confrontation and conflict probably will arise,and i t ie in these lands that the turmoil of emerg ent development w ill beexploited by communism wheneverpossible as a means of enlarging itssphere of influence.

I f Communist st ra tegy should besuccessful, the United States wouldbe confronted with two or more concurrent limited wars. I f either of thetw o ma jor Communist count ries wer edeliberately to choose a policy of inst igat ing l imited wa rs, i t w ould besound str a tegy t o init iat e concurrentconflicts. The impact on US security

Lkwtsmmt Colonel Jo8eph K. Brattoa k with the Arnwe O&e of theDeputy Chief of Staff for Afilitarv OPemtwrw in Washington, D. C. A gmduute of the US Army Command andGeweral Staff College and the USArmzI War College, he received aMaster of Science degree from Masewchu8etts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Ma8swchneett8. His mili ta~eervice includee duty in Europe withthe hth Armored Diviaien awd inKorea wth the 7th Divisiow.

L..

resources would be severe. .-Darticularlvi f w a r in Korea , India , Ira n, or E uropewere to begin while the United Statesis committed heavily in Vktnam. Ifthis should ha ppen, the U nited St a teswould also be committed to protectthe Free Worlds vital interests ineach th rea tened a rea .

There are Iimite to the number ofregiona l wa rs for w hich the U nitedStates can tolerate concurrent commitment. The potential opponent=alsois limited in this respect. Nevertheless, i t appears that the United Statesmust be prepa red to w a ge.concurrent lya t lea st tw o limited w a rs, an d to d o soin widely separated regions. Since itmay not be feasible for the UnitedStates to wage a large-scale regionalwa r or wa re and st ill ma in t a in an a dequate capability for other contingencies a nd for deterr ence w ith inbeing forces a lone, such forces probably would have to be reinforced subsequently by sizable general purposereserv e forces.Problams Are ManyThe problems associated with concurrent regional wars are enormous.

,The United States must retain a general w a r ca pabili ty a t a l l t imes. Stra t egic mobility mns t be provided tomatch forces programed in any combination of two regional war contingency plans. Mobilizat ion and reservebases capable of rapid reconstructionof forces a nd ma teria l commit ted inlimited wars, moreover, are essentialto a void degra da t ion of genera l w a rcapabilities.

The Korean War was a limited regional war wi thout a prepared e t rategic pla n and without a ny widespreadprior recognit ion th a t such a wa r couldor w ould be wa ged in th e nuclea r age.Thus, K orea ma de it possible for th efirst time to think seriously of limited

[ Miliiry IWiew,. .

4

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

9/116

war. Currently, the Jimi ted war inecmt heeet Aeia ie a nother exa mple ofth e a pplica tion of a n a d J Locstr a tegyto a situation which wae not foreseenclearly in its incipiency.I t ie importa nt t o recognize tha t unlese regiona l w a r ca n be prevented, itmuet be limited. When t he vita l intereste of the U nited S ta tee a re involved,she must be prepa red t o condu ct a

REGIONAL WAR S7RATE6Yt oward genera l war . US s t r a t egy ,th erefore, must a im to confine regiona l wa r w the minimum intensitypossible. Objsctivee must be acldevsdby regional etrategy asytnmetriesl lyadvantegeeue to the United Steteewithout exceeding the opponents escalat ion threehold.A key to sueeees in regiona l wa r iethe achievement of maximum conces

l imited war or , a l ternat ively, to faceescalat ion to general war or some significa nt surrender. Neith er of t hese a lternatives i! acceptable. Accordingly,the US cont inuing search for mili ta ryoptions and emphzaie on the less destructive forme of violence is intendedto provide controlled and useful forcein environment s of grea t ~uncert a inty .

The major concern in regional warie esca lat ion. If crucia l interezta ar einvolved, successive and progressivecomm itm ent s ma y f orce th e conflictJdy 1SS7

sions from tbe enemy w ithout und ueesca lat ion a nd with out forcing him tothe desperat ion creat ed by the need torelinquish a vital interest , At worst ,there would be a re turn to the s ta twcquo ante; at best , i t may be possibleto achieve certain rollback goale before terminating hostili t ies.

Since a strategy for regional warmuet provide for deterr ence a e w ellas for the conduct of hostilities, plan:ning should consider the intsrdependence of nuclear a nd nonnu clear deter

5

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

10/116

REGIONAL WAR STRATE6Yrents. There can be no effective regional deterrence without a globaldeterrenc~ a nother exa mple of th edirect relationship between generaland limited war capabllifles. The Cuba n missile crisis exemplified t he a pplication of a combined regional andglobal deterrence against a epeciiicthrea t .I t wi l l a lways be important for theenemy to know that a ll over t he w orldhe is opposing US military power inits ent irety -even t hough only a ema llfraction of the power may be in thefield. Similarly, while regional stability ie prima rily a fun ct ion of t he prevailing local balance of power, thereC a n be no truly effective regional bala nce w ithout a concomita nt global ba lance. These considerations illustratethat , whi le regional wara inherentlyare limited, in their global context,th ey a ffect t he w orld pow ers and worldbalance of power either directly orindirectly.Structural OptionsIn planning regional deterrence,there are three structural optionsavailable, and the optimnm deterrentstra tegy is th e one w bich permits t headoption of the beet mix of theee options. In essence, the United Statescould uee onsite power, regionallyavailable power, and homeland-basedpower.

The optimnm military power mixfor a ny pa t ilcular region muet be det ermined by w eighin g loca l pow er fa ctors. Defense economics, the prevailing regional political climate, andglobal commitments will be importantfa ct ore in deeieion ma king, a e w ill t heuniq ue milita ry criteria of th e regionitself.

If aggression is part of a piecemealopera ticm, forces immedia tely a va ilable in the area mnet block a fai t

a cwmn pli.The exietence of such forceeusual ly w il l be a n. a dequa te deterrent ,If aggression is more ambitioue, however, deployed forces would delay thea ggr essOr unt ill reeerv e forces couldbe applied.

A continued and selective US forw a rd deploym ent , t herefore, still willbe needed in t he 1970s. A forw a rdstrategy not only provides quick react ion, it a lao ie a mea ns t o exploit fa vora ble evente a t a ppropriat e t imes a ndplaces.In plan ning forw a rd deployment fort he 1970-80 per iod, t he epeeit ic loca -,tiona of military bases will requirecareful scrutiny to avoid a possibilitythat the politicai liabilities of usingforeign fa cilities w ill out w eigh inherent deployment a dva nt a ge. Whereverpossible, milita ry forces a bould be IOJ :cated on territory that is controlledby t he Un ited St a tes or by come firmally.

In crea sed etra t egic lift ca pabilitiesin the future significantly will leesenrequirements for overseas bases andeven for deployed ma npow er, if w e assume th a t r eeerves ca n be responsivew ithin 30 t o 45 da ys. A forw a rd deploym ent solut ion w ill encompa ss bot hregional and strategic reserve forcesin some suitable mix, with technologyand defense economics playing rolesequally important with that of military planning.Nuclear Ragional War

Whether nuclear w ea pons should beinjected into regional war is a funct ion of preva iling circumst a nce. Normally, it will not be in the best USinterest to do so, but their use cannotbe precluded peremptorily. Secretaryof Defense Robert S. McNamara hassta ted th a t, ! preeent forcee conld relyon n onnuclea r mean s to count er a w iderange of Sine-Soviet aggreseione, ex

.MiliiryilwioW.8

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

11/116

REGIONAL WAR STRATEGYcept in Europe. The overriding 05jection to the use of nuclear weaponsin regional war is the danger of escalat ion tha t is inh erent in such use. Alt hough some stra tegist ha ve w rit t entha t nuclear wea pons must be used inlimited wars, most have concludedotherwise.

The United Statee, with mutual defense a greements w ith over 40 na t ions,

meaningful partnership in crisis. Thetraining of indigenous armed forcesis necessary. Continuing politicO-milita ry etTorts to ident i fy a nd correlat emutual goals and s tra tegy are neededsinca i t ia essent ial tha t U S a nd a l liedforces ha ve clari ty of understa ndingand mutual acceptance of common regional s t ra tegy .

As long as the United States has

NATO.%tRegional strategy muet recognize the primacy of maintaining the integrity of NATOEuropewill retain her commitment to coHec- vital interests in a particular region,tive security in the 1970s. No feasi- there must be allies in that region.ble US strategy for the deterrence or It a lso wil l he crucial to US strategyconduct of regional war can be devel- to be able to ma inta in th e sta bil ity ofoped w ithou t reg iona l a l liance s t ruc- these a l lies aga ins t externa l pressuresturee. of interna l insurgency. Inh erent ly, th e

Ther e a re corollar ies to a llia nce sys- government of the allied country isterns .Cont inued mili tary a nd economic the one best agent to withstand locala id t o a llies usua l]y is req uired t o pro- pressures, just as indigenous forcesvide greater s trength and a more are best able to cope with regionalMy les7

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

12/116

portance of regionai alliances is theprobability that in tbe 1970s theUnitad States wil l be the only FreeWorld nation that has the power tooppose internat ional cmmmmism.Even the strongeet of other Western~st a tes hencefort h will be of significa nt~strategic assistance only in its own~ -E uropea n region.F ~ lnally, th e stra tegic import a nce ofk.*logistics is such th a t n o sta te ca n engage succeaefuSy in dis tant warswi thout an adequate base infrastructur e. P roblems of base rights a nd a c1.

~ 6

mutual security systems and cooperat ive logistics a rr a ngement s w ill be essential to solve the problem.

In form ula t ing spesific tenet a ofmili tary strategy which would be ap-plicable wofldwide, it is necessary firstto esta blish a stra tegic cmwa pt w hichsupporta national objectives. Such aconcept for regional war is selectivecontainment supported by a strategyof dynamic stabil i ty.

I t is essential to this strategy thatvital US strategic interests in eachw orld region be ident ified. Regiona l

MilibIYSwim

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

13/116

w a rfare , wi th its inherent threat ofesca lat ion to genera l w a r, should notbe accepted except to preserve or attain these vital intereste. Even then,force should be a pplied on a eca le bestca lcula ted to prevent hostilities broad ening into general war.

In some areas, preservation of thes ta tus quo will he the best feasiblepolicy; in othere, dynamic stabilitymay permit advances toward objectives which a more conservat ive stra tegy would dlamiss as unattainable.But these advances must be madeshort of r egiona l w a r, or by a successful conclusion to such a war. Genera lly, a dva ncee ehould not be a tt emptedw hich w ould crea t e a proba bility ofregiona l wa r .Stratagic TanetsAn analysis of the mili tary etrategyrequirement s of th ose areas of th ew orld in wh ich regiona l w a r is meetlikely t o occur indica tes cert a in etra tegic tenets of general application forregiona l w a rs : US regional mil i tary s tra tegy inthe 1970s must be conceived principally to defeat th e ma jor t hreat : Commun ist-inspired a ggression of va ry ingintensities, aimed at subverting, isolating, and destroying the countries

of the Free World. Since no mili tary strategy canbe opera t ive wit hout a first-prioritygeneral war readinese poeture, regiona l w a r stra tegy must be considered a n essent ial subsidiary to genera lwa r s t ra t egy a nd a n adequa te genera lw a r ca pabili ty must be ma inta ined. Regional and global balances ofpower are interdependent. Mili tarystrategy, therefore, must insure that

globa l or regiona l pow er elements, t ogether a nd separa tely, rema in in ba lance or develop a symm etries fa vora bleto the United Sta tes .

. .REGIONALWAR STRATE6Y

In the 1970s the probability ofconcurrent l imited wars may arise.In consideration of the anticipatedca pabilities of t he Communist ca mp,regiona l wa r st ra tegy must provide forat least two concurrent l imited warsin widely separated areas, and eti l lmaintain contingency reserves and ageneral war posture.

In regional war , the UnitedStates probably would be al l ied withone or more indigenous powers. Typically, the armed forces of such alliesw ould he enga ged in strength in theirhomelan d or in a dja cent a reae. U Sforces, on t he other hand, would depend on long lines of communication.Regional war strategy, therefore, dicta tes that mutnal securi ty must bestructured to provide ma ximum par ticipation of indigenous allied forcesa nd fa cilities, w ith a llied forces t obe tr a ined a nd equipped by th e U nitedStates, prior to hostilities, wherevernecesea ry a nd possible.

Loss of Western Europe to communiem would represent an irreversible a nd unfa vora ble shif t in th e w orldbalance of power far exceeding inmagnitude and signif icance any Ioeein other areas. Regional strategy,,t herefore, muet recognize th e prima cyof maintaining the integrity of NATOEurope. Regiona l w a r n orma lly w ill notbe in tbe best intereets of the UnitedStates because of its high coste andthe ever-present danger of escalation.National security policy prescribegoale to deter war and to win any

war which becomes necessary at thelowest possible level of inteneity. Regional war etrategy, therefore, dicta tes th e need to ha ve a vailable a globally committed force which posseseesa complete range of integrated, flexible, a nd credible deterr ence th a t ca n

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

14/116

be applied in any region or combina. tion of regions.

s In most w orld regions, t he fisca land political problems of a peacetimedeploym ent of U S forces w ill rendersuch deploym ent, on a la rge eca le, infeasible. Peacetime forward deployment, however, a re importa nt toprevent fait8 wconzplie, acclimatizeforces, establish a regional infrastructure, demonstrate the f irm purpose of US commitment, and aid inthe ma intena nce of regiona l eecurity ,country building, and stabilization.Appropriate US forces with an expanda blesupport infra structure a honldbe deployed forw a rd in those a reasw here th e khrea t of confllct exists a ndwhere such forces are acceptable tothe country or countries concerned.

. The difficulties of a rr a ngin g forw a rd deployment in certa in dista nta reas, coupled w ith the. problems tha tw ould be crea ted by th e movement ofetrategic reserve forces to these areasfrom the United States on short notice, dictate the creation of regionalreserve forcee, on la nd or a floa t, es th ebeet available compromise.

S ufficient a ir a nd sezpow er muetbe provided to control etrategic routesto any region of deployment.

The peacetime deploym ent of regiona l w a r forces of th e strengths a ndtypes required probably ie infeasible.Since th e grea test opport unit y t o limita nd termina te regiona l wa r dependeona ra pid initia l response th a t could lea dto quick victory or favorable negotiation, a responsive strategic mobilityca pa bility -a ir a nd sea liftis essentia l . Rea dineas of mobili ty elements a ea minimum must be equal to that ofthe forces being deployed.

In large-scale l imited war, or inconcurrent regiona k w a rs, a ctive dut yfoicee proba bly w ill B e ina dequa te in

num bers to eng a ge in suet a ined opera t ions. Regional war strategy, therefore, will dictate the organization,training, equipping, and maintenanceof eiaable general purpose reserveforces th a t a re ca pable of oversea scomba t deploym ent w ithin 30 to 45da ya of initia l notif ica tion.

. Timely st ra t egic responee t o regional threats frequently wil l dependon the US capabil i ty to l i f t men andequipment. To insure rapid strategicresponee in regional war, selectedequipment a nd supplies for pla nned,deployment forces ehould be proposit ioned in or near t he thr eat ened regions.

Regiona l wa r stra tegy ehould envision th e use of nuclear w ean ons onlyfor use in or near the bat t le areashould be available regionally but notpla nn ed for uee, except a s directed byproper politics] authority after theenemy ini t ia tes nuclear warfare.

In consideration of the requirement for w orldwide deterrence a ndthe possibility of concurrent conflict,forces should not be shift ed fr om oneregion to another to counter suddenthreats . Such threete must be met byforces in th e th rea t ened region or byuncomm itt ed str a tegic reserves.

St ra tegy for regiona l wa r muet bebased on alternate means of eelectivecont a inment a nd colla tera l exploita tionto support or cree~ dyn a mic etebilityfully consistent with over-all nationalobjectives and national security pel-icy. S uch a comprehens ive ca pabilityis militarily essential, economicallyfeasible, and politically indispensable.With i t , US mil i tary st?ategy carfrust ra &by det erren ce, indirectmeans, or military victory-regionalCommun ist thrust s in th e deca de ofth e sevent ies. :

Military ROViOIV0

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

15/116

ANATIONAL CORPSECURITYLieutenant Colonel Irvin M. Kent, United States Armu

The views ezp-re.med im this article are the author8 aud are not uece88arily thoee of the Depmtmont ofthe ATVW, Depavtmeut of Defeuse,or the US Army Cemmaud and Gen-eral Staff College.Editor.

D ES P ITE ra cent improvementin training programe for Fed. era l ca reer civilia n personnel, t here remaine a wide gap between the needfor, a nd t he eupply of, midlevel a ndhigh er level personn el w ho u nders@ndthe relationship between militaryforce, military poIicy, and the otheraepects of the foreign and domesticpolicy of the United States.

Numeroue officials throughout ourFederal structure must not only understand this relationship, but mustbe able to apply such understandingto the eolution of their daily problems. This ie obviously true in department a nd a gencies such a s St a te ,11

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

16/116

NATIONAL SECURITY CORPSDefense, United States Information-Ageqcy, Agency for InternationalDevelopment, Central IntelligenceAgency, Office of C ivil D efense, Officeof Emergency Planning; and the Execut ive OS ice of t he P resident .Other AgenciesThis understanding and applicationis, perhaps, less obvious, but almostequa lly neeeesar y, for a t lea st certa inkey officiale in oth er depar t ments a ndagenciee euch as the Federal Bureauof Investigation, the Federal Avia!ionAgency, and the Departments of theTrea eury, J ust ice, Agriculture, a ndHealth, Education, and Welfare. Certakdy, the newly created eenior interdepartmental group, and ite subordinate regional interdepartmentalgroups, must be etaffed with personnel who have had training in the ueeof both the military and the nonmilita ry facets of na tiona l pow er in th ea chievement of na t iona l object ives.The laa t-na medgroups represent t heclea rest r equirement for such qua lified pereonn el. As U . Alexis J ohns onhas eaid:. . . the peculiar nattwe of internal

Lieutenant Colonel Irvin M. Kentis with the Judge Advocate Section,Heudquartere, US Amny Air DefenseCommand: Ent Air Force Ba-se, Colorado Sprmge, Cotarado. He holde aB.A. dtrg~ee from Swracuee Universi tyin New Yark and an LL.B. from Harvard Law School, Cambm-dge,Ma8eac?weett8. His 8ervice indudee duty inEwrope during World War II; in theAvctic; with the O~e of the StaffJudge Advocate, US Arnw Communications Zone, Europe; a nd with theUS Army Combat Development r70mmand, Civil Affair8 Agency, Fort Gordon, Georgia He is the author of TheCommander and Civil-Military Rekr=tirww~ which appeare,d in the April1967 i8eue of the MILITARYRmaw.

warfare, its deterrence and m@preaaien require a blend of military andncnmilitaW coantermea8ureeand corrective actions. In a veW real 8en8ethere is no line of demaroatirm between milita~ and nonmilitary meaaures.

Thla pronouncement ie beginning tobe understood throughout most af-fect ed G overn ment a gencies. Lessclearly understood, perhape, is the interplay between mil i tary and nonmili ta ry meaeurea in oth er a spects of th ecold wa r, a nd in the deterrence or COU .duct of a l imited or a genera l wa r.Economic, political, and military policies muet he coordina t ed. ThkJ doesoccur today to a considerable degreea t th e highest levels of G overnmentwhere policy ie formulated. However,t he implement a t ion of such a cohesivepolicy requir es a pa ra llel level of un derstanding by those who must turnpolicy pronouncement s int o da ily a cts.Senior Action OfficersAt mismanagement, and evenhigher levels, daily acte are not oftendra ma tic, bold etepe. Ra th er, the na tiona l policy is execut ed by t housa nds. .of small, seemingly unrelated actionsta ken in our na tiona l ca pitol, t hr oughout t he U ni ted St a t es , and a t hundredeof pla cee th roughout th e w orld. I t isa t t hie senior a ction officer level th a tw e need, an d la rgely do not h a ve, personnel w ho ha ve th e tra ining a nd w hounderstand the relationship betweenthe mil i tary and the nonmili tary aspects of our policy. These senior action officers must he integral memhere of their ow n depart ment or a geucies if they are to be truly effective.

Some emall stepe have heen takent o pr ovide such personn el by: Sending a handful of civilian officials through the eenior serviceschorde.

MiliiryReview&,,,, ., , ..s

12

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

17/116

NATIONAL SECURITT CORPS Excha nging a n even smallernum ber of car eer dicers betw een th e

State and Defense Departments . Attendance of a still smallernumber of mili ta ry personnel a t St a teDepa rt ment schools. Detailing a few military officersfor dut y with certa in civilia n a gencies. H iring some retired milita ry personnel for w ork in such a gencies.Nevertheless, the total of these effort s, w hile la uda ble, is insufficient t o

meet the needs of the Federal Government for a n outsta nding group ofkey tra ined people w ho ca n w ork w ithboth mil i tary and nonmili tary problems, ca n understa nd the rela tionshipbetween the two, and unders tand theabsolute neceseity for coordinated action:A corps of national security officialscould provide these personnel. Sucha corps would not constitute a newdepart ment or a gency: Ra ther, i twould serve as a pool to provide therequisit e t a lent needed t o fill key po-

Senior action officers must understandmilitsry and nonmilitary aspects of policysitions which require a high degreeof understanding of the interplay betw een mili ta ry a nd nonmili ta ry fa ctors in national policy. Some administrat ive overhead system would haveto be orea ted, but th is should be sma llJuly1967

and.could probably best be performedwithin the framework of an exist ingoffice of t he executive bra nch.These officia ls w ould be r equ ired ona long-t erm ba sis. A thr ee or four-yea rdetail of a career military officer

A primary incentive w ould be s car eerlasting to age 60 or 65w ould be ina dequa te since, before hecould rea ch a level w here he w ouldha ve a rea l impa ct on policy, he wouldreturn to his military service. Fortun a tely, however, t he num ber of suchpeople required would be relativelylimited. A survey of the departmentsand agencies probably would show arequirement of not more than 2,000snch spaces from GS13 or lieutenantcolonel a nd higher gra des. Such a eurvey should be ma de promptly t o ident ify specific posit ions t o be t illed byadequately cross-trained personnel.

The E xecut ive Office of t he P resident should be charged with supervis ion of such a survey a nd w ith th emonitorship of a progra m designed toinsure that these spaces are properlyfilled. This monitorship would, of ne-,cessit y, include responsibilit y for t herecruitment, training, initial placement, a nd ca reer ma na gement of th ese

13

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

18/116

: NATIDNAL SECURITY CORPSspecially selected and trained per-kennel.

The key to a successful program iethe recruitment of the type of peoplewho are needed. Certain special inducement s proba bly w ill be requiredto obta in a st eady f low of highly quzdified a pplica nt . A prima ry incent ivew ould be the opport unit y to ent er int oa career corpe in which an individualcould remain until age 60 or 65 sothat there would be neither the necessity nor desire to prepa re for a S eccmdcareer w~]ch now faces so many professional mifitary officere.

While euch a car eer corps w ouldneed peaple physically and mentallyca pable of outst a nding perform a nce ofduty, the physical s tandarde need notbe as strict as those required for ac-

Career civifian Omt id.9often sre ety nr iedby the nsrrownese of their career fieldtive military service. This factor, whencombhed w ith job security unt il a ge60-subjeet t o proper perform a nce ofduty and ~ sona l . good conductshould provide a prime incentive forma ny milita ry officers inmidcar eert o

B&.:. . . .

a P P IY for tra nsfer to such a ca reer corps.Similar l~ ca reer civilian officials a lltoo often find th emselves sty mied in

midcareer by the lack of opportunityfor further professional training, and

S ome milita ry officers would make goodrecruits for the corpsfrustrated by the narrowness of thefield in w hich t hey ma y a pply theirskills. Between these two groups maywell be found tbe bulk of the candL,dates for a career corps of nationalsecurity officiale.

Accepted a pplica nt should be a llowed to take with them to this coimstheir accrued retirement rights. Allactive Federal service, regardless oft ype, sbouldbe credit ed forlonge%t yand retirement purposes. They shouldenter the corps at a rat ing not lesstha n tha t w hich they held in their previous eervice. Within tbe corps, theyw ould be subject to t ra nsfer a s ,an dwhere required on a worldwide baeis .They a nd t heir dependent s should beentit led to governmental medical care.ont hea eme basis a s a ctive dut y military personnel.

Their gra de should be persona l, a ndpromotion ehould be based upon a

Military Roriow4

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

19/116

merit selection system. Continuingprograms of middle and upper careereducation should be provided by att enda nce a t senior service schools, a tprivate institutions of higher learning, a nd by oth er government a l a gencytraining. A progressive educationalprogram a t leas t equal to tha t nowprovided for ca reer milita ry officerswould be required. Such a programshould be ta ilored for th e individua l,a nd supplement , ra ther th a n duplica te,the educational and experience background he brings to the corps.Pay should be based on civil service standards, with a saving clause toprevent a ny init ial finan cial 10ss. P rovision should be made for adequatestat ion and family separat ion al lowa nces for certa in a ssignments. Retirement pay would be on a contributivebasis w ith the G overnment providingth e requisite init ial sum for th osetra nsferred from a ct ive miJ i ta ry duty .Others w ould bring w ith t hem thefunds w hich ha d been built up in theirprevious F edera l service, S ome specia lstipulat ion might ha ve to be ma de forthose recruited into the corps fromout ilde the a ctive F edera l service. Thesxistence of such a corps would be apowerful magnet to a t tract a numberof highly qu a lified people w ho, for onereason or a nother , h a d left governmenta l eervice a fter some years ofservice. Thks w ould not be a corps int owhich a young man could enter uponcompletion of college. Ra t her, t hk+corps, designed to fill only key ee-Ieetedpositions, would require a greatdea l of ma tu rity a nd experience.

WMle almost all recruitment intoth e corps event ua lly w ould bea t a boutth e end of 15 yea rs of Federa l service, recruitment init ially should spanth e group of th ose w ho ha ve betw een16 t o JJOyears of service. Those in theJUJY1967

NATIONAL SECURIN CORPSupper level of t hk group could servein t he corps for a t leest 10 yea rs before reaching age 60, or perhaps 66for those in the supergrade or generalofficer cat egory . Applica t ion should beopen to a ll in th e F edera l service wit hout restriction to current departmentor agency, and to those currently outs ide th e G overnment w ho have a number of years of previous governmentalexperience. Detailed study of formerrecords, as well as writ ten and oralexaminations, would provide selectionboa rds composed of high -level governmenta l officials w ith a basis for th eirchoice of those to be accepted.

It would be impossible in any shortperiod, of cours e, to fill a ll t he key P osit ions in the va rious depa rtment s a ndagencies with national security corpe0-~ na t iona l a gency cha rgedwith the a na gement of the progra mw ould ha ve t o develop priorit ies formanning such posit ions. But once aposit ion in a ny depa rtm ent or a gencyhad been determined to be a nat ionalsecurit y corps officia l position, t he d epar tment or agency would f i l l i t witha designated national security corpsofficer unless n one wa s a va ila ble w ith the requisite qualifications.It should be possible within a yearto recruit and plsce at least 10 percent of those required, and to havethe program at full s trength in notmore than f ive years af ter init ia t ion.Follow ing tha t , a nnua l recruitmentwould be on an as required basis.A national security corps reservestr ucture m ight a lso be etudled to provide for th e needs of th e Nat ion uponmobilization. A structure similar tomobilization designees in the ArmYmight be used. With or without such,an expansion capability, the existenceof such a corps would provide an increa se in na tiona l security .

15

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

20/116

How NewCharles A. I.ofgren

THE years since 1953, some-I

Nth ing of a m yt h has deteloped aboutthe Korean War. I t was , according tosome commenta tors , the U nited Sta tesf irs t l imited wa r . B ut wa s it?

Central to answering the quest ionis the job of defining limited war asth e term is curr ently used. When sugges t ing that pas t wars were or werenot limited, the same meaning mustbe a ssigned to limited a s ie a ssignedto it in current military, diplomatic,a nd schola rly discourse. Ot herw ise, w eare in no posit ion to make real comparisons. U nfortun a tely , much of theli terature on l imited war in the nuclear age gives relatively lit t le at tention to those general features whicha conflict muet display to qualify asa l imited w a r, a nd which the hk! torianmight use for comparative purposes.H ow ever, some cha ra cterist ics a re a pparent .

The most obvious. element in ourcurrsnt concept of limited war is thatsuch war must, in fact , be limitsd in

ka + AA___....- ... . ..hlilii~ Review

....16

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

21/116

its dimensions. The dimensions mostrelevant to l imited war include theoter-all objectives of each side, con.flict techniques, amount and types offorcee employed, weaponry, and thegeogra phiw il a rea of conflict .

Other dimensions include the duration of hostilities, t he number of a llies participating with each side, andthe legal s tatus of tbe war on eachside. Actua lly, mea suring limita tion ina ny given w a r m a y be a problem. Forhistorica l pnrposee, w e ca n best mea sure the restra int present in th e actua ldimensions of conflict by compa rin gthose dimensions a gainet w ha t observers at the t ime regarded as real alternat ives .IfistoricalExsmplesAmerican military hietory readilyprovides exa mplee of limita tion on th edimensions of w a rfa re. Rega rding objectives, only in the Civil War andWorld War II were they unlimited tothe extent that the Uni ted Sta tes dema nded th e complete eurr ender of th efoe. And in World Wa r II , J a pa ne surrender was not entirely unconditionalsince the nation retained its Emperor.

In other US conflicts, objectivessometimes shifted a nd even broad enediu th e cdprse of th e fight ing, a e in theWar of Independence nd the Spanish- ,America n Wa r. H ow ever, neither prelimina ry nor f inal w a r a ims includedtbe complete subjuga tion of t heenemy. More typical goale have beenfreedom of the seas, territorial gain,not including conquest of t he oppo-

Charles A. Lofgren ie an AesietantProfessor of American Historfi atClaremont Ikfene College, CCaremoat,California. He holde a Bachelor ofArte, a Masters, and a Ph. D. degreefrom Stanford University tn Califor-nia. He formerly taught at San JoseState College, San Jose, California.

LIMITED WARFAREnent a , homela nd , colonia l eelf-det ermina tion, protection of America n livesa nd propert y , a nd the safeguarding ofAmerica n security w hich ha s been agoa l in every w a r in the view of ma nypeople.When we compare ohjectivee in thepre-1950 w a rs w ith a lterna tive underdiscueaion a t th e t ime, we eee tha twhat appears to he a l imited aet ofgoals to us in the mid-20th centuryma y n ot ha ve seemed so limited t o contempora ry oba ervera , In t he Wa r of1812, simply fighting for freedom ofthe eea a and t o end the Indian menacefrom Ca na da appea rs t a me comparedto f ight ing to subjugate England.Matched againat destroying the Spanish G overnment , f ight ing for a freeCuba in the Spanish-American Wareeems similarly mild. But, of conree,contemporaries did not consider subjugat ing England or destroying theSpanieh Government as serious, realal ternat ivee.Modesof ConflictAlthough judged against al ternatives that contemporaries did regardas real, the major objectives in comepast American ware can paes mustera s limited ones. Du ring th e undecla redna val w a r w ith Fra nce, a less l imiteda lterna t ive w a s considered at th e t ime.Alexander Hamilton relished the ideaof the United States takhrg a port ionof the New World possessions o%Frances ally, Spain. In World War I,the US concept of peace withoutvictory paled beside what emerged asthe victory-through-peace goala of theE uropean a l liea .Regarding conflict techniqueeforces involved a nd w ea ponr yAmericans observed less restraint in theirpre-1950 wars, as meaeured againet ,potential modes of conflict. The needfor limita tion in t hese a rea e simply did

J uly1967 17

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

22/116

&

! LIMITED WARFAilEnot occur t o t he policym ekers involved.Yet in its t w o least l imited w a r%th eCivil War and World War IItheNation observed certain limits.

In the CWil War, the Union washighly circumspect in its use at firetof a x-sla ves a s soldiers a nd in incitingrebellion or even flight among theslaves remaining in the ConfederateSt a tes. The Federa l G overnment a lsorefrained from treat ing Crmfederateprisoners as trai tors , al though in astrict lega l eense this might ha ve beendone. The nonuse of poison gas inWorld Wa r II ie a n exa mple of res traint .We ca n a lso det ect some holdingback in other conflicts. In the undeclared na val wa r , the US Navy wa snot permitt ed t o ct iptur e una rmedFrench ships. In the war with Mexico,th e tota l forces fielded by t he U nit edSt a tes seem sm a ll com@a red to th osemobilized by eith er side a mere deca deand half later in the Civi l War. In theMexican interventions under Preeident Woodrow Wilson, the UnitedStates again exercised restrainta ga inst bringing sizea ble forces t obear .6eograpkic al Limit at ionsIn geographical extent, Americanshave clearly observed limits in theirmilita ry opera t ione-World Wa r H ,with ita global scope, is most noteworthy as an aberrat ion in the broadsweep of the Nations past. Perhapswe ehould not make too much ofgeographical l imitation, because limited object ives a nd lirhit ed resources,in par t , ma y ha ve dicta ted i t . TheMexican War provides an examplebot h of force u sed for essent ia lly persuasive purposes beyond the areabeing contested, but used as a precieion instrument within geographkxdlimits. G enera l Winfield S cott ma rched

..

on Mexico City, but P resident J a mesIL P olk resieted dema nds to a nnex a l lof Meaico or even t o extend t he w a rt o a ll of Mexico.

I t seems readi ly a pparent tha t ,among the wars which the Uni tedSt a tes fought prior t o 1950, a t leastsome were limited in t heir dim ensions.If such limita tion is t he only test, theKorean War most certainly was notour f irst l imited war.When present analysts speak about

l imited war , they are ta lking ahout aphenomenon in a w orld fa r di f ferentfrom the pre-1950 world. What hasmade limitation in the conflicts of thepresent era of history especially urgent is th e exiet ence of w ha t AlbertWahlstetter some years back calledthe delicate balance of terror.Today, threatened or applied force isa ra t iona l instr ument of policy only ifi t is used w ith restra int . Use of th elarger nuclea r wea pone a gainst a nenemy involves the risk that he ora n a l ly of his w ill use th em in r et~ n.Addtiional ElementsThis leads to consideration of &oot her element sin a ddition to t he obvious one of limita t ion-w hich a rehound up in t he modem notion of l imi ted war . Firs t , recent analys ts havestressed that l imi ted war ie a meansof employin g ca refully a nd consciouslycont rolled force for intern a tiona lcommunication and persuasion. In it ,mil i tary operations are not primari lyva lua ble in their own right for seizingand holding, destroying, or kWing.They a re mea nt t o convince th e enemythat coming to terms is less costlythan not doing so, and to convincea llies tha t t heir support is w ell pla ced.

Second, current l imited war doz.tr ine cont ends tha t forma l or informa ldiploma cy-t ha t is, some form ofMllitaIYevie18

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

23/116

LIMITED WARFAREbargaining between the contendingpart ies-must be a n integra l part ofa rm ed con~ lct if i t is to rema in limited. Sometimes diplomatic intercha nge ma y be taci t a t most , as w hen aw a r just fa des out. On ot her occa sions,diplomatic negotiation represents amean s of a djusting minor outst a ndingdifferences. In addition, i t offers the

To aesign either force or diplomacy aetatus inferior to that of the other isto miss a funda menta l point-both a ret ools of policy. Thie d oee not m ea nth a t policy is th e independ ent va ria ble,for development s on either t he diplomatic or the mil i tary front may affectpolicy goals. The important fact isthat threatened or applied force and

USAmwWhile the Korwm ContJict was limited in t er r it or y a n d for ces u sed , it d oes n ot fit t h emodern detinitimrof limited w srcha nce to forma lize w ha tever th e contending parties may be wil l ing to accept in light of th eir ga ins a nd lossesboth on th e mili ta ry front a nd in thosea reas closely intertw ined w ith th e mili tary si tuation.

Ae comprehen ded by curren t doctrine, force and diplomacy are closelyrelated. Batt lef ield succese may makediploma cy fruitful; diploma cy ma yma sk low -level a pplica t ions of force,and i t may give legit imacy to positions established by military means.J I I ly1967

diplomacy are dynamical ly related.Moreover, far from being a new development , this is a tra dit iona l a ssociation.Statesmen and warriors , however ,temporarily lost sight of i t in theirfirst reections to the near-total experience of World War H and to thenuclear weaponry which came out ofthat war. The implicatfone of the balance of terror reintroduced the force-diplomacy relationship into the strat~egists world.

19

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

24/116

LIMITED WARFARELimited war in the 1960s is defined hy t he presence in a n a rm ed conflict of three interlocking elemente: Actual l imitation on the conflict s dim ensions. Force employed as a persuasivetool. Diplomacy used as an integral

The most useful period of the warto exa mine for determining w hetheri t was a modern l imited war is thatwhich followed the Chinese Corn.munist intervention, when the strategic debate in the United States overthe war reached i ts height . In la teNovember 1950, a s t he U nit ed Na t ione

At nwNw J sp.d,,,Futurehis tor ia nsa re likely t o term Vietna mthe firs t U S limitedwa r ef the nuclea ra gepa rt , w ith force, of t he policy im plementation process.There is a new u rgency behind ea chof t hese element s beca use of t he riskewhich al l-out war entai ls . Because acomplex of considerations like thesew a s found in th e Korean Wa r, tha twar may have heen l imited forreasons more imperative than thosewhich underlay l imitat ion in previoue U S w a rs. B ut w a e th e confl ict inKores real ly a ha ped by a commitm entto modern l imited wa r doctr ine?

forces neared the northern border ofKorea, t hey met la rge n umbere ofCommunist Chinese troops. Shortlythereaf ter , they wi thdrew and thebattleline was stabilized acroes thepeninsula somewhat south of Seoulrthe capital of the Republic of Korea.

The following summer, they pushedthe North Korean and CommunistChinese northward to a l ine sl ightlya bove th e 38th P a ra U el, th e bounda ryfrom 1945 t o 1950 betw een Nort h a ndSbuth Korea. The war in Korea then

. Mlliify Review0

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

25/116

turned into a s ta lema te a long tha t l inea nd, f ina lly , w a s concluded by a n a rmistice in J uly 1953.Despite the presence of CommunistCh inese Armies in Korea , the makersof US strategy refused to condonedirect a ir or na va l w a r fare a ga instthe Communist Chinese homeland.Such act ion, they feared, would involve th e U nited St a tes, a e Genera l ofthe Army Omar N. B ra dley , Cha irmanof th e J oint C hiefs of S ta ff , put it , inthe w rong w a r , a t t he w rong pla ce, a tthe w rong t ime, and w i th tbe w rongenemy.No PrecedentGeneral of the Army Douglas Mac-Arthur, the US commander in the FarEaet and United Nat ions commanderin Korea, took exception, however, toWa shing tons refusa l t o condone directact ion againet Communist Chbm. On1 December 1950, w hen a n int erview era sked him a bout th e limita t ions imposed on his forces, Ma cArt hu r calledthem an enormous handicap withoutprecedent in milita ry history.Againet the foregoing background,no one can doubt that , in the way i tw a s condu cted by Wa sh@ton, th eKorean Conflict was something lesstha n a n a l l-out w a r , especial ly w henmeasured a ga inst the a l terna t ive. suggested a t th e t ime by G enera l Mac-Art hu r. The va rious officia le of t heTruman administration, who teetifiedin the S enat e hear ings w hich follow edG enera l Ma cArt hurs dismissa l, ma dea bundant ly clea r tha t the US G overnment under President Harry S Truma n w a s intent on keeping i t tha t w a y.After J a nua ry 1953, th e new a dministrat ion of Dwight D. Eisenhowerlargely displayed the same determinat ion.

B ut tha t in itself doee not make th eKorean ConSict f i t the current modelJlliy 1967

%LIM 17E0 WARFARE

of limited war. For one th ing, themotives underlying US restraint needconsid era tion. As ea rly a s 1957, H enryA. Kissinger suggested that theU nited Sta tee feught the Korea n Wa ra s sh e did, n ot beca upe w e believedin l imited w a r but beca use w e were re-luctant to engage in all-out war overthe iseues which were at s take inKorea.Official PositionThe Truma n a dministra t ion sa w th ea ffa ir in Korea not so much a s a realwa r , but r a t her a e a nuisance a nd anaberrat ion which distracted at tent ionfrom the more important Europeana rea. Limita t ion, th en, w a s not out ofa ny r ealiza t ion t ha t in th e nuclear eraforce could serve ae a rational tool ofpolicy only if it were limited. WhenGenera l Bradley s t a ted tha t the administra tion opposed implement ingthe MacArthur proposalabecausedoing so might tr igger an enlargedFar Eastern warhe demonstra tedt he officia l position.

Subsequent events lend credence tothis analysie. The maeeive retaliation and new look policies of theimmediate post-Korean period suggest that policymakers stiK did notcomprehend th e centra l fact of t he nuclea r era . With th e development of m utual deterrence between tbe majorpowers, the most probable wars wouldbe limited and the most credible national defense posture would be a balanced one which included forceeequipped for such w a rs.The K orea n experience is a mislea ding one eince limitation was present,but th e reasone for l imita t ion w ereessentially different from those of themodern l imited w a r . In a ddit ion, pea cenegotia tions-a nother element bear-,ing a deceptive surfa ce simila rity totbin khg in t he 1960e-a ppea red in

21

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

26/116

LIMITEOWARFAREthe conflict. As early as mid-December1950, when President Truman proclaimed a nat ional emergency in theface of wha t Me Fa r E a stern com-ma nder ca lled a new, w a q he a lsohinted tha t t he U nited Sta tes wa s wi]].ing to. negot ia te a set t lement . In J uly1951, seven months Iater, talks werelaunched. H ow ever, t hey never heea mepart of a closely coordinated combination of force and diplomacy.Wasbir@ons RefusalWashington largely refused to admit that force might be gainfully employed for persuasive purposes-thatie, to give incentive to the enemy toopt more quickly for a satisfactoryarmietice. On one han& this refusala ppeared in the fa i lure to a pply a ir a ndnaval pow er aga inst th e enemys vita lsin China. A century earlier, much incont ra ct , P reeident P olk did eend hisforcee against the center of Mexico inan effort to hasten a sat isfactorypeace. Similar action in Korea couldha ve led to a far less limited wa r .On the other hand, the US policy-makers might have ordered the USground at tack northward to continue.B ut th ey even declined to try this moremoderate method of raising the enemys costs. Instead, the US Government was content with such pressureas a stra tegica lly sta t ic wa r put on theNorth Korea n an d Communiet Chineseopponents.Some Americans, General Mac-Art hur included, did propose tha t agreat deal more force be applieda ga inst th e oth er side. Yet even implementing their suggestions wouldnot ha ve tra nsformed t he w a r int o thetype of conflict which limited warconn ot es t o toda ys stra tegists: Ma c-Arthur and his supporters neverlinked th eir proposils to a ny mecha nism for ending the war short of thea

surr ender of th e enemy. P ertinently,one of the final incidents Lw&ng toGeneral MacArthurs recall was hisuna uth orized ult ima tum to t he enemyfa rces in t he field to ca pitula te or fa cedestruction.Altogether, then, according to theview tha t any war l imited in i t sdimensions. ie a limited, w a r, Koreawae not the first such contlict in INhistory, beca uee th ere w ere others before it . And for t he sophisticat ~ d limited w a rrior of t he 1960e w ho believesthat Iimited war involves not only objective reetraint, but also tbe skillfuland purposeful manipulation and coordina tion of force a nd diploma cy, th eKorean Conflict wae not the Nationsfiret limited w a r. It eimply did n ot conta in a ll th e essent ial ingredient s, muchless a proper mixture of them.Insufficient FerceLimitat ion was present , but for thewrong reasons. Negotiation waspresent, but not coordinated withforce. I t was in many ways a ster i lefa ctor. Force efficient t o ra ise t heenemys costs to the point where hedesired a more rapid set t lement w a sla cking in officia l U S policy. F urt her,even those crit ice of t he officia l policyw ho ca lled for more milita ry pressuredid not conceive of it as an integralpart of a meaningful w hole.

If futu re historia ns a ccept th e sophisticated views of current strategists as the etsndard for categorizing limited wars, they likely will accept Vietna m ra ther tha n Korea a s thefiret US l imited war , a t least in thenuclear age. In Vietnam, the UnitedStates and her allies have consciouslylimited the conflict in respect to eachof the dimensions mentioned, Tbedegree of limitation and restraint exercised m a y be insufficient in th e eyesof some crit ics of officia l policies. Tbe

Miriiry Review

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

27/116

actual restraint observed, however,can only be called substantial, if notrema rka ble, in view of na tiona l ca pabilit ies a nd considering th e alterna tiveof a world nuclear war or of an enla rged Far E as tern wa r .In Vietnam, too, military force isbeing put t o persua sive uses. G oncera for the psychopolitical effects ofmili tary operat ions and at tent ion tocivic action programe testify to this.US bombing of the north is a claesic

-

.LIMITED WARFARE :

exa mple, in th e same ca tegory as G eneral Scotts march on Mexico City, ofapplying force beyond the area inwhich a decision is sought to influencethe decision in that area . US leadershave reaff irmed repeatedly a wil l ingness tu negotia te.

In a sense, the conduct of the Vietna m w a r signifies tha t a revolut ion instra tegic thinkhg in th e U nited St a teshas occurred within the past decadeand a ha l f.

Many Americans are confused by the bsrrage of i@~m)tion about mifiteryengagements. They Iong for the capsule eummary which has kept tebs en ourprevious war% a fine on the map that divides friend from foe.

Precisely what, they ask, is our military situation, and what are tbe pros-pects ef victory?

The first snswer is that Vietnms is aggression in e new guise, ss fsr re-moved from trench warfare ss the rifle from the Ionghow. This is a wsr of infiltration,of subversion, of ambush. Pitched battles are very rare, and evenmore rarely are they decieive.

Presirfat L@on B. Joh?won

July 1967 23\

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

28/116

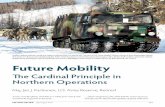

Lieutenant ColonelG eorgeD . E ggers,J r .UmtedStateu AZWW

D RING a n a ppeara nce beforeth e House Arma d S ervices Committa a in ea rly 1961, th e Comma nda ntof the US Marine Corps, GeneralDavid M. Shonp, appraised the adequa cy of t he existing U S str a tegic a irl if t a nd sea lif t ca pacity by say ingt here w a s a ctu a lIy %oore t ight t henferry in th e Armed Forces, a nd tha the wae including airplanes and shipsin t he w ord ferry. This an a lysis refleetad Ganeral Shoups concern oversignitiea nt dedcits in the t iat iona l stra tegic mobili~ mpa bility.

With MB peet to a irlift , bot h q ua ntitaliv13ar@quaMatiVe@ScienciS5 sxistsd. k t he sealift t ield, t he Navy sa mphibious sh~ ~ troop tra rteporta ,did! t ddpei,fg@@mr a w ere a t IW2t a dw it%~ ~ w ~ int f bl~ k obsohsa cence.Th6ae dei3cien&i@hti developed dur24

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

29/116

ing an era when US decieion makershad assigned a relat ively low priori tytothe ma intena nce of th e ca pabili ty todeploy sizable air and ground forcesof the continental United States(CONU S ) -ba sed etr a tegic reserve t ooverseas crisis a rea e.Presidential RecommendationsIn a epecial defense meesage submitted to Congress in March 1961,P reeident J ohn F. Kenn edy a nnouncedpla ne to improve t he ca pability of U Sconventional forces to cope wi th thethr eats of nonnuclear w a re and sublima ted w a rfa re. Among t he specificmeztsur ezrecommended by t he P reeident a nd a pproved by Congress in 1961were:

An acceleration and increase inth e procurement of a irlift a ircra ft a lready in productionthe C-130 andthe C-295.

D evelopment a nd procurement ofthe C-1.41jet traneport. Construction of new ships to increase the speed and capacity of theamphibious lif t provided the US Marine Corps by the US Navy.The defenee budgets for the ensu

ing four yeare continued to pbaeeemphasis on t he improvement of str a tegicLtsutenant Colortel George D. Eggers, Jr., ie w-tit the 1st Battalion,Islth Cavnkp, 1st Cavalr# Diviaierc(Airmobile), in Vietnam. He hokfe aB.S. in Militaty Science from the Univsrmtg of Mar@wu2, College Park; aMinter of Public Affairs from Princeton University, New Jersey; and is agrae!mzte of the US ArmII War CoUege,Carliale Barracka, Penna@ania. ?Iizacrvice ineludee troop and etaff dutyin Japan, Korea, and Germang, andw-t+ the War Plane Diviaien, Directorate of Strategic Plana and Poliog,O&e of the Deputy Chief of Staff forl&litt?&Operatiene, Department of

My 1s7

STRATE61C MOBILITYa irlift a nd a mphibious chipping capa bilities. However, efforts in the strategic mobility ares were not confinedto the procurement of new aircraftand shipe. Strategic mobility exerciees w ere condu cted to t est t he va lidi ty of movement pla ns a nd t o demonstrate the abi l i ty of the United Statest o project elements of her milita rypower in support of her global collective security commitments. The mostepeeta cula r of t he exercises w a s l?igLift, during which the personnel ofa n a rm ored division w ere deployed byetrategic air2ift from Texas to Germa ny in lese tha n t hree days .Ferry CapabilityToda y, w e obviouely poseesa a considera bly enha nced ferry ca pacity.Clea rly, w e must cont inue to improveupon tbie capabili ty in t he yea rs a head.Strategic mobility will constitute avita l component of th e US na tiona ldefense posture during the next 15years. The prima ry t hreat te t he pea ceand etabili ty will continue to be theresolve of th e ma jor Commun ist na t ions t o inspire, suppot i a nd exploitlow -level a ggression a ga inst t he countries of the Free World. The UnitedSt a tes, undoubtedly, w ili be ca lled uponto help counter this threat by providing a ssista nce to her a lliee in th e formof advice, materiel , and combat support or combat forces.To mueter her resources and to deploy her forcee a s required, t he U nit edStatee might be required to choosebetw een tw o broa d stra tegies. TheUnited States might continue to pursue her present strategy of forwarddeployments, w ith hea vy commitmentof forcee t o key overeea e a rea s, prestoekzge of equipment a nd supplieeboth af loat and zzhore, and her upkeep of a mobile strategic reservewi th in the CONUS.

25

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

30/116

1STRATEGIC MOBILITYAlternatively , we might withdrawpart or all of our forces presently de.ployed and place greater reliance onth e rapid deployment of th e CONUS

str a tegic r eserve to dea lw ith t he Communist t hreat s a e th ey develop. Rega rdless of th e na ture of th e stra tegicconcepts which evolve, strategic mo-,bility will be a matter of continuingconcern t o U S pla nners a nd opera tors

ity. The advantages of one mode oftransportat ion of fset the dkwdvanta ges of t he ot her. An optimum mixof st ra tegic airlif t a nd sealif t to meetfuture contingencies cannot be determ ined w ith precision. The va ria blesinvolved a re m a ny, an d th eir interrelat ionships are highly cOmP1eX .

~ Among the purely military factorsIw hich a pply in ea ch crisis situa tion

Troops of the M Armored Dhision st Fort Hoed, Texss, await their departure forGermany in Operstion Big Lifta a they devise and implement na t iona lstrategy in the 1967-80 period. Strategic mobility involves, essentially,th e int erth eeter deploym ent of forcesby airlif t or sealif t or by a combina, ~ ion of both mean s. A movement w hichrevolves long distan ces w ithin a th eater of opera tion ma y also be cla ssifiedas a etrategic deployment.The experience of the past two deca des has demonstra ted tha t t he a ircra f t a nd the SKI Pare pa r tners , notrivals, in t he field of str a tegic mobll

ca lling for st ra tegic deploym ent of U Sforces or equ ipment a re cons idera tions of t ime a nd speed, th e dista nceto the objective area, the quantity oftroops and materiel to be deployed,a nd the usabili ty a nd ca pacity of portand airfield facilit ies at both ends ofth e move. Other mili ta ry factors a rethe availability of prepositioned stocksin t he overseas a rea, tbe resupply an dreplacement requirements, and tbeconcurrent deman ds upon th e U S stra t egic lift ca pa city . .

, MilitcryReview26

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

31/116

Two strategic mobility operations illustra te tbe r eleva nce of t hese fa ct ore.The na tu re of t he initial pha se of t hecommitment of US units to the Dominica n Republic w a s such th a t a prepondera nce of a irSift over seal i ft w a semployed. On th e oth er ha nd, th e va etbulk of the men and equipment deployed to South Vietnam has movedby sea.Budget ProgramThe dimensions of the US strategicmobility capability are set by a continuing planning and study cyclew hose a nnua l end product is th e Depar tm ent of D efenee (D OD ) budgetprogra m for a irlif t a nd sealift forcee.Theee forces include t he t ra neport a ircra ft of t he Milita ry Airiift C omm a nd(MAC ), t he t roop car rier a ircra ft ofth e ta ctica l a ir comm a nd (TAC), th epassenger ships, ca rgo ships, an d ta nkers of the Mil i tary Sea Transportat ion S erv ice (MS TS ) nu cleue fleet,and certain reconditioned cargo chipsdesigna ted a s forw a rd f loa t ing depots.

The military etrategic mobility inventory also contains the long-rangetra nsport a ircra f t of th e Air Na tiona lG ua rd a nd Air Force R eeerve, a nd theamphibious shipping of the US Navy.S upplementing this mili ta ry capa bil itya re th e a ircra f t of t he U S commercialair carriers and the ehlps of the USMerchant Marine.Several major trende are discernible in t he str a tegic airlif t a nd sealift

programe and activi t ies of the pastfive yea rs. On e of th ese ie t be modernizat ion of t he str a tegic a irlif t f leet.Top priority has been given to thedevelopment , production, a nd precnr ement of long-ra nge, la rge-pa yloa d, t urbine-pow ered a ircra f t . B y th e ear ly1970s, the military strategic airliftf leet of th e regula r Alr Force will becomposed prima rily of t he C-141 a ndJuly 1ss7

STRATEGIC MOBILITYt he C-5A. This m oderniza tion progra mwill create a dramatic increaee in airlift capability.

At tbe present time, i t would takeMAC 30 days to transport an Armyforce of 21,000 troops and 34,000 tonsof cargo from the United States toSouth Vietn a m. B y th e end of Fisca lYear 1971, MAC, using a combinationof C-141s and C-5As, will be able tomove the same load in only 15 days.The decision by the DOD leadership to assign the highest priorityw ithin t he stra tegic mobility field t oth e modern iza t ion of st ra tegic a irlif twas based principally on ite determination that tbe exist ing air l i f t capabil ity w a s less a dequa te to m eet cont ingency requirements than was thea ealift f leet . The a irlif t moderniza tionprogram wae also given impetus byDODs adoption of the concept of airlifting personnel t o join up w ith equipment a nd euppliee a lrea dy positionedin eehmtedforeign locations.Sivil Air CarriarsAnother trend is the increased useof US civil air carriers to supplementMACe capability. Since 1961, MAChas applied an increasing percentageof its capability to fulfilling specific, mili ta ry a ir li ft requirements, part icularly those generated by large-scale,etra t egic deploym ent exerciees. Concurrently , the civi l air carriera haveha ndled more r outine mil ita ry tra f fic.This tr end w a e a ccentua ted by th e decieion to commit US combat and combat support units to South Vietnam.During one 6-month period, US commercial airlines carried approximately66 percent of t he tota l nu mber of passengers and approximately 30 percentof the total cargo tonnage air l i f ted totha t a rea .

Modernization of amphibious shipping is yet a nother tr end in tbe pro. 21

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

32/116

STRATEGIC MOBILITYgra m. To increa se th e deploym ent potential of the Marine Corps, the amphibious forces of the Navy are beingfurn ished new sh ipa wit h speeds of 20knots a nd w ith a capa bil ity for vertica l envelopment a s w ell as over-t hebeach a esault . A long-ra nge goa l is t oprovide sufficient modern a mphibiousshipping to li f t eimultaneouelythe aseault echelons of tw o Ma rine divisionand wing teame.Partial Modem mt ion

A fourth trend is the patilal modernisa t ion of t he MSTS nu cleue fleet .This modernization has been limitedto the roll-on and roll-off ship category. In F kca l Yea r ~ 966, t hr ee ofthese ships, designed to load and discharge wheeled and tracked vehiclesrapidly , were operational . MSTS haealso contracted to charter a fourthship of this type which ie to be constructed and operated by private industry . A program was ini t iated in1965 t o develop a new cla se of Na vyroll-on and roll-off ships with greaterca pacity a nd speed a nd low er procurement a nd opera ting costs. Congressa uth orized a nd a ppropria ted fends forthe construction of two fasbdeployment logistics ships.No comparable modernization progra m is cont empla ted for t he MSTSgenera l purpose ca rgo ships, pa eeengershzps, and tankers, al though rehabil itat ion and lengthening of some of thelat ter ships a re pla nn ed. The deeisionnot t o modernize t heee element eof t heMSTS fleet st emmed from th e judgment that the combined MSTS andMerchant Marine capabil i t ies weregeneral ly a dequa te to meet present a ndprojeeted military requirements.Anoth er fa ct or w hich influences t henature and scope of the MSTS sealift modernization program is congressional insistence that the MSTS

fleet not duplica te the capa bilities t heoretical ly avai lable in the US Merchant Marine.New MSTS ships muetbe justified, in part, on tbe basicthatt hey a re special purpose ships w hicha re mili ta ry in design an d functionand do not compete with US commercial shipping interests.DetariemtienA fina l tr end is t he deteriora tion of ,the US Merchant Marine. Since theend of World War H, ite posture hasdeel ined to euch a n extent tha t increa singly la rger Federal finan cial a ssistance has been required. One aspectw ith w hich w e ar e concerned is t heabil i ty of the active and reserve mercha nt fleets to supplement ,a s required,the national mil i tary seai i f t .There has been general agreementthat the number of ships in the Mercha nt Marine wa s a dequa te to meett he r equirement s imposed by a cold orlimited war crisie. I t has also beenrecognized, however, that our merchant ships have been growing progressively obsolescent. Most of themare extremely slow by present-daysta ndards a nd la ck modem ca rgo ha n-H ling ca pabilities. Nevert heless, nocomprehens ivem oderniza tion progra mhas been undertaken.The effort to meet the sealift requirements in support of the US commitment in South Vietnam broughtto light tmo additional shortcomingsof th e Mercha nt Ma rine a e consti tut ed.First, there is the question of theavai labi l i ty of US merchant shippingin a low or mid]ntensi ty warfare ei tua tion. MSTS officials ha ve cont endedtha t U S priva te shipping opera torsha ve not ma de sufficient tonna ge a va i la ble te sa t isfy th e requirement s inVietnam. Representatives of the shipping iines ha ve count ered by cha rgingthat MSTS:

a . MilprY Revmw

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

33/116

STRATEGIC MOBILITY

. Ha s not d eveloped a n effect ivesh]pping requiremen~ program to facili tate the preparation of long-rangepla na by th e shipping induetr y . Has fai led to make the most ef f icient use of the ships under its contr ol ; a nd cha rt er ra tes, in some instances, have been too low.The availability problem centersa round th e question of w heth er th echippers can be expected to meet expan ded mili ta ry requirements in a

nonna tiona l emergency si tua tion w hilerisking the loss of the commercialbusinese t o foreign compet itors. Theshippers position ie that the Government ehould rely more hea vily on t hew ithdra w a l of ca rgo ships from t heMarit ime Adminiatrat ions nationaldefense reserve fleet. More than 100

Intwavi.WirIifter became operational in 1965

ships have been ordered placed in anactive status at a cost of approximately $300,000 to $400,000 per chip.A final deficiency in the MerchantMarine ia a shortage of trained personnel to man the ahlps aseigned tothe Vietnam run. Shipping line offi

ciala and representat ives of the Mari

t ime Administrat ion and MSTS havebeen meeting periodically in an attempt to resolve some of the immediate sealift problems which adverselyaffect the Iogiatics situation in SouthVietnam. Regardless of any progressmade toward the el imination of thesesh ort-ra ng e difficult ies, t he long-t ermm, . . . .. ,.. .{- .. ~ ,.,6.

:-, ,. .. .-.} ,

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

34/116

STRATEGIC MOBILITYReflection upon these strategic mobility trends leads to the conclusionthat the modernizat ion programs havenot ma de a th oroughgoing a t t empt to

develop a modern sea lif , t ca pability tocomplement the comprehensive airliftmodernizatkm program. As a consequ ence, a progressive la ck of ba lan ceis emerging ,betw een the qua Sityof thestra tegic a irli ft ca pacity a nd tha t ofthe strategic sealift fleet .The d evelopment of t he C -5A repr esents eignitica nt progress tow a rd overcoming one of the primary disadvauta gee of present -da y a irlift a ircra ftthe cargo-carrying constraints imposed by their configur+ ions a nd pay loa d ca pa cities. Aside fr om t he moderna nd un ique fea tur es buil t into the newa nd highly specialized am phibious a ndroll-on and roll-off shipping, no comparable breakthrough has been madeor is in prospect with regard to twoproblem ar eas in th e militsr y sealiftfield-increa sed speed a nd impr ovedcargo handling.Recommended ActionsThe current t rends toward part ia la nd spora dic a irli ft modernizat ion a ndover-all deterioration of the US Merchant Marine must be reversed i f weare to possess the requisite flexibilityto deploy forces a nd equipment und erthe conditions of international crisiswhich could obtain during the remainder of the 1960s and 1970s. Wemust have botb modern seali f t anda irlift to perform th e str a tegic mobility tasks best suited to them. Thesespecific actilons a re recomm ended : Continued emphasis on tbe careful preparat ion, review, and correlation of strategic transportation requirements to support low or midintensity w a rfa re opera tions. The J ointCh iefs of S ta ff-D epa rt ment of D e

fense planning, programing, and

budgeting process provides a framew ork for th e a ccomplishment of thispurpose. ~ The implementa t ion of a long -

ra nge MSTS moderniza tion progra mto r epla ce th e fra ctional effort presently programed. First priority shouldbe given t o t he development of th enew class of fa st -deployn ient logisticsships. Second and third priorit iesshould be a ssigned to th e procur ementof new genera l purpose ca rgo shipsand tankers for the MSTS nucleusfleet.

The creation of a PresidentialCommission to investigate the capability of t he Mercha nt Ma rine to perform its dua l mission of ca rr ying U Scommercial cargoes and serving as anauxiliary to the MSTS tleet . The cont inua tion of th e str a tegic

a irSift a nd a mphibious s~ lpping modernizat ion programs. Funds for themoderniza t ion of MSTS s eelift shouldnot be diverted from these programs.The pr ocur emen t of C-141S a nd C-5Asshould be completed a s echedu led oreven expa nded if fut ure a irlift requirements so dictate. The amphibious shipping modernization programshould be continued until it achieveeita sta ted goa l of pr ovidhg a sufficientnumber of new SKIPSto l i f t s imulta neously the a ssault element s of tw oMarine division and wing teems.Strat egio Mobi l i t y Operat ionsThe current DOD organization forthe planning and execution of s trat egic mobilit y opera t ions ha s evolvedsince the end of World War II. Underthis syetem, tbe unified and specifiedcomma nders together w ith the individual services and transportat iona genciee develop th e t ra nsport a tionpla ns a nd movement echedules to eupport J oint C hiefs of S ta ff-a ppre+ edpla ns. The J CS periodica lly review

Militsrs ReviewA

30

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

35/116

transportat ion requirements snd capabili t ies a nd, wh en necessa ry, esta blish priorities for the allocation of resources to the ueing services and commands .As DOD Single Manager operat ingagencies, MAC and MSTS provide themea ne for etra tegic a ir li ft a nd sea lif t ;the Military Traff ic Management andTerm ina l S erv ice (MTMTS ) is responsible for t he movemen t of m ilita ry tr a f fic w itbin CONU S, to includeth e tra nsporta t ion of personnel a ndcargo to air and sea terminals.In fulfilling the requirement for simulta neous stra tegic deployments tothe Dominican Republic and to SouthVietnam, our strategic lif t resourceswere taxed severely, but no evidenceemerged of deficiencies in planningand control which would call for amajor change in organizat ion.Focal PointOne organizational improvementwhich ha s been ma de is t be esta blishment of a foca l point for str a tegicmobility w ithin t he D efense Esta blish.ment. A Special Assistant to theCha irman of the J oint C hiefs of S ta f ffor St ra tegic Mobility ba s been designa t ed. ,His m ission is t o provide afocus for a ll str a tegic mobility ma tters and to furnieh informa tion a nda dvice to the J CS a nd to the Secretaryof Defense on all facets of strategicmobility.In developing strategic mobilityprogram s, the J CS a nd the Secretaryof Defense have relied in the past onthe diverse inputs of the services,the operat ional commands, and thetransportation agencies. These inputswere correlat ed an d eva luat ed by th eJ oint S ta ff a nd the DOD s ta f f as par tof t he a nnua l pla nning, program ing,a nd budgeting cycle. It is in this correlat ion and evaluat ion process thatJuly lea7

STRATEGIC MOBILlfYthe Special Aseistant for StrategicMobility can perform an invaluableservice. He can provide the expertknowledge, objectivit y, a nd cont inuing interest w ith respect to a ba lan cedconcept of etrategic mobility that hasa t U lmesbeen lacking a t t he J CS -DODlevel.Major AdvantagesSh ould the present orga niza t ion foretr a t egic mobility prove ine@tu a l inthe years ahead, i t can be anticipatedthat an a t tempt wil l be made to combine MAC, MSTS, and MTMTS intea unif ied mobility comma nd under theimmedia te jurisdict ion of th e J CS .Such an arrangement, i ts supporteracontend, would have these major advantages :

It w ould provide a unit y of effortmissing under the current conceptw hich ca lls for separa te ma na gers forthe three primary forma of transportation.

By el iminat ing many of theoverla pping a nd duplica tor functionsof the Single Manager operat ingagencies it would reeult in greatereconomy and efficiency. I t would facil i tate strategic deployment pla nning by furnishing asingle point of contact for the usingservices and commande.To date, the studies of the variousproposa le ma de a long t heee lines ha veconcluded that the creat ion of a strat egic mobility comm a nd w ould result

in costly requ irement for new persOn nel an d facil it ies a rqi in t he genera t ionof complex budget and funding problems. The new command would notoffer any important advantages overthe existing organization to offset thedifficulties w hich its esta blishmentw ould propa ga te.These, of couree, a re t he tr a ditiona larguments in opposition to centraliza

31

-

7/27/2019 Military Review July 1967

36/116

~tion. They were employed, withoutsieccess, a ga inst t he sett ing up of t heD efense S upply Agency a nd t he St rikeComma nd. H ow ever, th ey ha ve been-decisive in relation to the determination not to restructure the strategicmobility organization. This is becausethey have been reinforced by the lackof reedily demonst ra ble opera t iona l orplanning defeeta which would justifyconsequential cbangee in the presentorganizational groupings.