Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

-

Upload

grulletto-grullone -

Category

Documents

-

view

226 -

download

0

Transcript of Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

1/112

This article appeared in AMERICAS, a journal of the Pan-American Union, Washington DC, USA, in November 1965 (vol.

17, no 11), with illustrations by Juan Carlos Castagnino from the 1962 edition ofMartin Fierro published by the

University of Buenos Aires Press.

EPIC OF THE GAUCHO

by Catherine E. Ward.

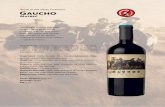

Gaucho and tango are probably the two Argentine words most foreigners have heard of. Both have

become traditional institutions rather than actual realities, but they are still good representatives of the two

most characteristic faces of Argentina. The tango is the music of the city; tough, sentimental., quick-witted,

sexy, it makes the most of the character it has grown out of its hybrid origins. The Gaucho is the man of thePampa, the "real" country that encloses the city and remains aloof from it; the expert horseman and

cattle-worker, with his primitive life and sententious speech, deeply rooted in the land. And the archetypalGaucho is Martin Fierro, hero of the popular epic which has become the Argentine national poem.

It would be difficult for anyone to visit Argentina and not come acrossMartinFierro; as a national institution itis worked hard. A steady stream of editions fills the bookshops, with copies bound in cowskin or poncho fabric

as tourist attractions: quotations from it appear in advertisments on fences and on decorative tiles in suburbanvillas: its mine of quotable aphorisms can be called into play on most occasions.

The background ofMartin Fierro is the 60's and 70's of the nineteenth century: the years of civil wars betweenBuenos Aires and the Federalist provinces, and of political confusion in the city, which meant neglect or

exploitation of the country people to the point of their extinction. The old semifeudal life of the country settlersand huge estancias (ranches) was disrupted: conscription drained the land of men; corrupt local government

and an inefficient frontier force provided them no protection.

The poem relates the adventures and sufferings of its hero froin his own point of view. In the first part he ispress-ganged into the frontier army against the Indians, and after several years, unpaid and in appalling condi-tions, he deserts. He finds his home destroyed and his family lost; gets involved in fights and becomes an

outlaw; and eventually, with his companion Cruz, escapes across the desert Pampa to try their luck with anIndian tribe. The second part takes up the story seven years later. Life with the Indians proves still worse: Cruz

dies in a plague; and after killing an Indian to rescue a captive woman, Fierro returns to his ownpart of the

country. He meets his sons, and Cruz's son, who in turn tell their stories, and engages in a singing contest with a

challenger who turns out to be seeking vengeance for a brother whom Martin Fierro killed in a fight yearsbefore; finally, after a farewell speech of advice to the sons, he rides off into the distance. Interspersed with theplot are digressions on Gaucho skills and the lore of the Pampa, comic incidents, passages of proverbial

wisdom, and lyrical flights on metaphysical themes; and throughout, like a chorus, laments at the Gauchos'unjust fate.

*

The author ofMartin Fierro, Jose Hernandez, was born in 1834 in Buenos Aires of old Spanish-Argentine fami-lies. His father dealt in cattle on ranches on the Pampa south of the city, and he grew up there, working with the

Gauchos, until the fall of the dictator Rosas in 1852 brought on a period of civil wars. Herniindez campaigned asa soldier and as a journalist on the side of the Federalists against the Unitarians in Buenos Aires, but his chief

loyalty was always to the country people, whose rights he championed in pamphlets and newspapers (including

for a short time one of his own). He went into exile several times, to Brazil and Uruguay; eventually he settled

in Buenos Aires and became a deputy and a senator. He died in 1880.

The two parts of his long, poem (it has over 6.000 lines altogether, in six-line verses) were published in 1872

and 1879. The first part had an extraordinary popular success: copies of the cheap yellowish pamphlets were or-dered wholesale by stores deep in the country, the Gauchos accepted it as their own, and it was recited and readaloud to those who could not read. The second part (twice as long as the first and more varied) was written by

popular request, and equally successful. Its first printing was of 20.000, after 48,000 copies had already beenprinted of the first part alone.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

2/112

In spite of its popularity, however, the poem attracted no interest in cultured circles of the time, whose sightswere all set on Paris; there had been a number of earlier works in Gaucho idiom, but the fashion for these had

passed. Martin Fierro was not treated seriously as literature until 1913, when a series of lectures by LeopoldoLugones dealt with it in terms of universal epic and heroic poetry. It is now an accepted part of the school

curriculum -- a classic to be bored by or to rediscover.

*

As literature, Martin Fierro has a curious position. It is a primitive poem written by an educated man, a

genuinely popular work, not a rustic poem intended for sophisticated readers, but not limited, either, to its

popular audience. It can he read on various levels: as an entertaining story, as a protest against social injusticeand a record of historical conditions, for its special poetry born of the character of its hero and his world, and for

its practical philosophy of life in general.

A foreigner can approach Martin Fierro on any of these levels, but to anyone who enjoys proverbs one of thebest things about it is aphorisms. These are by no means always banal folk wisdom, but have a bite to them, like

this practical comment from a reformed cardsharper:

Mas cuesta aprender un vicio

Que aprender a trabajar.

It's harder to learn to he crooked than it is to learn honest work.

-- or this astringent piece of advice on the realities of friendship:

Su esperanza no la cifren

Nunca en el coraz6n alguno

En el mayor infortunioPongan su confianza en Dios --

De los hombres, solo en uno,

Con gran precaucion en dos.

Don't sum up all your hopes in any one heart ever;

in the worst of troubles put your trust in Godamong men, in one only, or with great caution, two.

The language of Martin. Fierro is both colloquial and dignified. The narrative, with its colourful dialect

expressions, is quick and humourous, and the more heightened, lyrical passages use simple images with a quaint

formality reminiscent of the poetry of the Bible. The story is told in the first person as if sung to the guitar in thetraditional Gaucho manner: the language of the poem carries its own rhythm and would have nothing to gainfrom the addition of a tune, but it can well be imagined half-recited, half-intoned, to an expressive

accompaniment. Needless to say any translation of a poem like this is bound to be imperfect, as apart fromtechnical difficulties, there could be no equivalent dialect in another language that would draw on the same

range of images. Rather than go into these problems, as a translator, I would like to try to express what I mostadmire inMartin Fierro,and what seemed most worth attempting to communicate in another language.Four

excerpts can illustrate this.

Al sentirse lastimao

Se puso medio afligido.

Pero era indio decidido,Su valor no se quebranto

Le salian de la garganta

Como una especie de aullidos.

Lastimao en la cabeza

La sangre lo enceguecia;

De otra herida le salia

Haciendo una charca ande estaba...

Con los pies la chapaliaba

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

3/112

Sin aflojar todavia.

When he felt he was wounded he started to groan a bit,

but he was tough as indians come and his courage didn't break out of his mouth there came a noise like the howling of a dog.

He was wounded in the head and the blood got in his eyes

from another gash it fell and made a puddle where he stood he was splashing in it with his feet and still without weakening...

In this literal and horrifying description.of a fight to the death we have the poem at its simplest level and

superbly done: a vividly pictured adventure story.

Martin Fierro is essentially a male and heroic poem. Like theIliad, its raw material is blood and courage: man's

survival or death are its primary laws, and its moral themes are images of that battle the necessity for mental

courage in the face of suffering. The world ofMartin Fierro might be one from pre-history. Its landscape, thetreeless pampa, is non-human, neutral as the flat sea it resembles. Human life and society exist on it like islands,

and consist of basic elements: food and clothes, the family, work, companions, singing. Martin Fierro's ideal lifeas described at the beginning of the poem is simply these, and his greatest sorrows are being deprived of them.The poem's protests hardly get to mention the lack of further social refinements such as education or religion. A

Gaucho needs all his courage and skill to preserve his life as it is, against natural obstacles; the agents of evil inthe poem are the authorities who interfere to destroy this simple pattern.

Habia un gringuito cautivo

Que siempre hablaba del barco

Y lo augaron en un charco

Por causante de la peste

Tenia los ojos celestes

Como potrillito zarco.

There was a gringo boy captive -- always talking about his ship and they drowned him in a pond for being the cause of the plague.

His eyes were pale blue like a wall-eyed foal.

The pathos of this stanza is much rarer in the poem than the violence of the first passage, but it illustrates acontrasting point: Hernandez's skill (when he chooses) in organizing detail into dramatic effects, while

remaining in the character of the unlettered gaucho narrator. Here he uses a quite Shakespearian device of

bringing a scene to life by an unexpected homely touch: the captive boy's blue eyes arnong the dark faces of the

Indian executioners, and a sudden reminder of a wider world with the ship he talked about -- the immigrants'

ship that had brought him to the country.

However, parts of the poem show considerably less art of this kind than others, and it is often hard to tell how

far the naive or even banal elements in it are deliberate, as appropriate to a gaucho singer, or simply due toHernandez himself not noticing the difference. On the whole the impression is that although Hernandez was

deliberately imitating naive storytelling, he probably also shared the gauchos' unsophisticated tastes. In any case,the naive repetitions are balanced by the evident care taken throughout the poem to produce effects by contrasts

-- comic after serious passages, digressions after excitement, and so on.

A more important point is that the poem itself does not show signs of moralistic writing down, in spite of theexplicit didactic aims that Hernandez set out in his Prefaces -- by reaching the gauchos indirectly in their own

language, he hoped to influence them to respect themselves and learn more civilized feelings. The mostHernandez can be accused of on this score is that Martin Fierro, his hero, is not a typical example of a gaucho:by most accounts the gaucho soldiers were a bloodthirsty lot, and even in peacetime they were given a bad name

from the many outlaws and semi-savage casual workers who roamed the land -- there can have been few such

sensitive and God-fearing citizens among them as Martin Fierro. But the answer to this is that a hero can bearchetypical without being average-typical: one of the protests of the poem is that to the authorities the gauchos

are merely bandits, with no allowance for their human merits and rights.

The next two quotations also illustrate contrasted elements in the poem, this time of content rather than form.First something of the poem's high style:

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

4/112

Soy gaucho, y entiendenlo

Como mi lengua lo esplica --

Para mi la tierra es chica :

Y pudiera ser mayor --

Ni la vibora me pica

Ni quema mi frente el sol.

. Naci como nace el peje

En el fondo de la mar --

Naides me puede quitar

Aquello que Dios me dio --

Lo que al mundo truje yo

Del mundo lo he de llevar.

Mi gloria es vivir tan libre

Como el pajaro del cielo . . .

I am a gaucho, and take this from me as my tongue explains to you for me the earth is a small place and could be bigger yet

the snake does not bite me nor the sun burn my brow.

I was born as the fish is born in the bottom of the sea;no one can take from me what I was given by God

what I brought into the world I shall take from the world with me.

It is my glory to live as free as a bird in the sky . . .

This is the bravata --the singer's bravura piece of defiant boasting. Here, at the beginning of the poem, he is

presenting his credentials; he does so again in a similar tone at the start of the second part, and at the end thevoices of Hernandez and Martin Fierro merge in a confident claim for immortality. The exaggeration is poeti-

cally right and exhilarating. In a world empty or hostile to man, the powers of human imagination must be builtup defiantly if they are to exist at all. In such a world, man -- the only vertical on a flat horizon -- stands or falls

by the value he puts on himself.

So much of the poem is taken up with the gaucho's suffering and laments at the hostility of the world outside

(sufriris probably the poem's most frequent word), that it is a relief when the picture simplifies into the natural

hostility of man against nature. Faced with the challenge of the desert pampa, or even of natural disasters like

the plague, or the Indians' savagery, the gaucho can hold up his head and be active even in sorrow, whereas in aprison or an army camp, man-made ordeals, he can only suffer passively. These bravura passages ofself-assertion are like acts of faith, and in them the poem takes off into pure poetry: the simple images hold more

than they say.

Finally, some of Martin Fierro's parting advice to his sons:

Nace el hombre con la astucia

Que ha de servirle de guia --

Sin ella sucumbiria, .

Pero sigun mi esperencia --

Se vuelve en unos prudencia,Y en los otros picardia.

A man is born with the astuteness that has to serve him as a guide.

Without it he'd go under -- but in my experience

in some people it turns to discretion, and in others, dirty tricks.

El que obedeciendo vive

Nunca tiene suerte blanda --

Mas con soberbia agranda

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

5/112

El rigor en que padece --

Obedezca el que obedece,

Y sera bueno el que manda.

No one whose job is to obey has an easy time of it,

but if he's proud he only increases the hardships he has to bear

if you're the one to obey, then obey so the one who's boss does his job well.

Procuren de no perder

Ni el tiempo, ni la verguenza --

Como todo hombre que piensa

Procedan siempre con juicio --

Y sepan que ningun vicio

Acaba donde comienza.

.

Do your best not to lose either time or your self-respect.As you're men with power to think use your judgment when you act --

and keep in rnind that there's no vice which ends as it began.

The last quotations showed the poem's metaphysics, here are examples of its practical morality. And it is their

practical quality which is chiefly interesting about these sayings: in a world where no morality can be taken forgranted, any ideal not based on immediate reality would perish.

There are two sets of moral aphorisms in the poem: Martin Fierro's parting advice, which these verses come

from, and an earlier episode when the old thief Viscacha gives his advice to one of Martin Fierro's sons. They

are clearly intended to be contrasted. Old Viscacha is cynical to the point of living like a dog, and his adviceconsists in getting the maximum to eat with the minimum of trouble and no scruples; Martin Fierro is concerned

with surviving within the laws of society and one's own conscience, by keeping one's self-respect. But whatgives point to the difference between the two sets of values is that in so many ways they are alike. It is notsimpIy a contrast between material and spiritual values; both them are based on the necessity to survive by one's

wits in a hard world. Viscacha says:

Jamas llegues a parar

A donde veas perros flacos.

Don't you ever stop off at a place where the dogs don't look well fed.

El primer cuidao del hombre

Es defender el pellejo...

The first concern a man has is taking care of his own skin...

Hacete amigo del Juez,

No le des de que quejarse...

Make friends with the Judge, don't give him a chance to complain of you...

and Martin Fierro:

Ansi como tal les digo

Que vivan con precaucion Naide sabe en que rinconSe oculta el que es su enemigo.

El hombre, de una mirada

Todo ha de verlo, al momento

El primer conocimiento

Es conocer cuando enfada.

It's as a friend I warn you to be on your guard in life.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

6/112

You never know what corner your enemy's lurking in...

A man has to see how things are in one glance, right away.

The first thing you have to know is to know when you're giving offence . . .

But although their motives are similar in kind (self-preservation), they are different in scope. Martin Fierro's

morality is "better" than Viscacha's because it is bigger -- practical on more levels. He includes Viscacha's

world-view whereas Viscacha does not include his. The conditions of Martin Fierro's world are more complexbecause he includes the factor of conscience, and therefore defers to laws of psychological cause and effectwhich do not enter into Viscacha's calculations.

Martin Fierro's values are also convincing because they are upheld by his experience in the poem, and thedevelopment of his character. In the first part he is by no means entirely respectable, notably in the incident

when he picks a fight and kills the black man at a dance. There is no indication at the time that either he or the

reader is expected to feel ashamed of this, and presumably, it was acceptable by normal gaucho standards.

When he first introduces himself Martin Fierro boasts "that I never fight nor kill / except when it has to bedone"; and even much later in the poem he appeals to a primitive code of honor by making the excuse that the

black man was the first actually to draw blood with his knife. But meanwhile, in the course of the story, MartinFierro grows older and wiser (or sadder), and another more humane morality evolves through him. When thedead man's brother claims his vengeance, Martin Fierro is prepared to fight but not from choice -- he accepts

the company's decision to stop the fight. Some critics find this conclusion unsatisfactory; the Argentine writerJ.L.Borges has a story in which he makes Martin Fierro come back later to fight the second Black and be killed

himself. It might be still more "realistic" to make Martin Fierro win again, and be forced to accept theresponsibility for yet another death on his hands. . . . But the actual rather ambiguous ending is not out of

keeping with the way Martin Fierro's character has been moving. Perhaps a primitive code of honor and an

ethic of avoiding unnecessary violence are incompatible. In any case, by the time Fierro comes to sum up whathe has learned from life, in his advice to his sons, he puts his change of heart into words:

El hombre no mate al hombreNi pelee por fantasia

Tiene en la desgracia mia

Un espejo en que mirarse

Saber el hombre guardarse

Es la gran sabiduria.

Man does not kill man, nor fight just out of vanity.

You have, in my misfortunes, a glass to see yourselves in:

the greatest wisdom a man can have is to know how to control himself.

La sangre que se redama

No se olvide hasta la muerte La impresion es de tal suerte

Que a mi pesar, no lo niego

Cae como gotas de fuego

En el alma del que la vierte.

Blood that is spilt will never be forgotten till the day you die.It makes so deep an impression -- in spite of myself, I can't deny it --

that it falls like drops of fire into the soul of him who shed it.

This is acceptable, and respectable, because it is not a morality imposed by commandment from above. Its mo-tives are entirely practical: given the condition that man has a conscience, he must for his own sake take intoaccount the effects of his own actions on himself. And as Martin Fierro says to his sons, the only advice it is

possible to give is simply to pass on one's own experience. Without losing his character as a gaucho, by the end

of the poem Martin Fierro grows into a kind of Everyman, whose experiences and conclusions hold good not

only in his own world, but in other more complex places and times.

C.E.Ward [Kate Ward Kavanagh]

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

7/112

Enrique Policastro (1898-1971): Ombes ( private collection )

MARTN FIERRO THE GAUCHO

Introduction

When Jos Hernndez was born in 1834, Argentina was entering a period of nearly twenty years' dictatorship

under Juan Manuel de Rosas, which was to be succeeded by a further period of political confusion and civil

wars. The work and the life of Hernndez are closely involved with this stage of his country's history.

The River Plate Provinces had achieved independence from Spain in 1810-16; in the following years Paraguay,Bolivia and Uruguay separated into their present forms and the Argentine nation was defined. Republican

government was decreed but there was conflict over the form it should take, between the opposing parties ofFederalists and Unitarians. As a rough distinction: the Federalists, in favour of a federation between

independently governed provinces, were the provincial landowners and caudillos (leaders) supported by "the

people" -- representing the old order from Colonial times, when the land was divided into immense estates; theUnitarians, in favour of centralized government with Buenos Aires as capital, represented largely the

commercial and intellectual interests of the city, more accessible to European liberal ideas. In the late 1820's,

increasing confusion under Unitarian rule led to a take-over by Rosas, a Federalist governor of Buenos Airesprovince who, however, had by 1835 established a personal dictatorship over the whole country.

Buenos Aires did not become the official capital of Argentina until 1880. Until the mid-eighteenth century the

colony had faced towards the older cities in the north-west, nearest to Peru, the seat of Spanish rule; no directtrade across the Atlantic was allowed, and Buenos Aires was a small backward town, isolated by hundreds of

miles of the flat treeless pampa inhabited only by unconquered nomadic Indians. It first became a capital in the

late eighteenth century when Spain made a separate viceroyalty of the River Plate countries; it had theadvantage of contact with Europe across the Atlantic, but its right to be the seat of government was disputed by

the other provinces -- hence years of civil wars both before and after the static period of Rosas's tyranny.

Hernndez took an active part in these struggles: his life stretches from the last years of the old semi-feudal

society prolonged by Rosas, to the 1880s when progress in the form of railways, enclosure of land with

barbed-wire fencing, large-scale immigration, etc., was approaching its peak.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

8/112

Hernndez's parents both came from established colonial families: chiefly Spanish but including French and

Irish ancestors; Argentine for at least three generations. His father was not rich and worked as a cattle-dealer,travelling frequently between distant ranches. His mother's family, Puerreydon, was a prominent one; Jos was

born on their property on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, and brought up there by his grandmother while hisparents were away in the country. He had both Unitarian and Federalist relations; when he was six his mother's

family, as opponents of the Rosas regime, were forced to emigrate, and he then stayed with his paternal

grandfather and attended a private school.

His mother died when he was ten; at about this time he became ill and was sent on doctors' orders to live withhis father, who was working on huge cattle ranches south of Buenos Aires. He got well, learnt to ride and grew

exceptionally strong. Here he joined in the traditional life of an estancia (ranch) and the gauchos who worked it

-- experts with horses and cattle, the children of the pampa whose spokesman he was to become. The ranches helived on were close to Indian territory: Hernndez must have encountered both the friendly Indians who worked

with the gauchos, and the hostile tribes whose raids had continually to be fought off.

This life continued until he was eighteen, when his father was killed by lightning, leaving him with a youngerbrother. In the same year, 1852, Rosas was deposed and a period of intermittent civil wars set in, for almost the

next twenty years. During this period Hernndez took part as a soldier and as a journalist on the side of theFederalists, but chiefly, and apart from party politics, in defence of the gauchos and country people whose wayof life was being destroyed by conscription, neglect, and corrupt local government.

The fall of Rosas led to a confusion of loyalties, with battles first between pro- and anti-Rosas Federalists, then

between Buenos Aires (largely Unitarian) and the Federalist provinces. Hernndez first joined the pro-Rosasmilitia; later in Buenos Aires city he joined the party in favour of reconciliation with the Federalist provinces,

and wrote for that party's newspaper. A few years later the Buenos Aires government changed, and he was

forced to leave for the Federalist rival capital at Paran in Entre Rios province to the north-east. Here he livedfor the next ten years (1858-68): working first at manual labour (he was a huge, black-bearded, gentle, man

"like a strong-man in a circus", his brother described him); later at various posts in the Federalist government,including stenographer to the Senate; and always producing newspaper articles and pamphlets. He married inParan in 1863, and eventually had seven children.

Hernndez fought for the Federalists in the series of battles leading to their eventual defeat; as a journalist he

criticized his own party when necessary as well as violently attacking the Unitarians. During this period he canbe thought of now as an antithesis in ideas to Sarmiento, the great Unitarian president and educationalist:

Hernndez as champion of the values of the primitive life based on the land and its work; Sarmiento asrepresentative of change and civilization in the European (or North American) manner.

In 1869 Hernndez was able to return to Buenos Aires, and started his own newspaper there, called El Ro de la

Plata; after a year this was closed by Sarmiento when there was a new Federalist rising. Hernndez fought with

the Federalists in their final defeat and after it went into exile: first in Brazil and then in Montevideo, where heworked as a journalist for the next few years Uruguay, across the River Plate estuary from Buenos Aires,being always closely related to Argentina in politics and sympathies.

He began his narrative poemEl Gaucho Martn Fierro in a Brazilian village, and continued it in Montevideo

and in the small dockside hotels where he stayed when paying secret visits to Buenos Aires to see his family.The poem was printed very cheaply, in a yellowish pamphlet full of misprints, in 1872.

*

Hernndez's poem aimed to speak to the country people in their own language about their own troubles. It tells

the adventures and opinions of an archetypal gaucho suffering the hardships and injustice of the times: from acontented life working on a ranch, the unsuspecting hero is press-ganged into the ill-treated frontier militia; hedeserts to find his home abandoned and his family lost, becomes an outlaw, and finally escapes across the

frontier to try his luck living with the Indians. It is written in the words, images and proverbs of the gauchos --

almost a sub-language of Spanish: humourous, contentious, and lyrical, in rhymed stanzas supposedly sung to

the guitar, the gauchos' traditional instrument.

Argentine cultural circles were at this time ruthlessly orientated towards France; there had been a school of

"gaucho" poetry some years earlier, but this was considered a rustic idiom for which the vogue had passed.Martn Fierro was ignored in the city but had an unprecedented popular success in the country, where it was

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

9/112

accepted as genuine gaucho. 48,000 copies were reprinted in the next six years; it was ordered wholesale by

provision stores deep in the country, read and recited at local gatherings to those who could not read.

By 1874 Sarmiento was no longer President and Hernndez had returned to live in Buenos Aires. He went intobusiness with his brother, dealing in cattle and land, owned a bookshop; and took part in politics: he was elected

Deputy in 1879 and later Senator.

The 1870s and 80s saw a wave of material changes in Argentina. The Indians were exterminated or resettled,railways spread across the pampa, a flood of immigration altered the whole balance of the population andswelled the capital to disproportionate size. Hernndez continued as champion of the country people in their

perennial struggle against a remote bureaucracy. As a politician he toured country districts, a much-loved figure

who was popularly identified with the hero of his poem -- even in the city he was known as "Martn Fierro".

Popular demand led him to write the sequel La Vuelta de Martn Fierro (The Return of Martn Fierro),

published in 1879. It was twice as long as the first part, and (unlike some sequels) as good or better. It is more

varied and more serious, and perhaps more studied: Martn Fierro, from being a straightforward hero to whom aseries of adventures happen -- largely picaresque in spite of their social message -- becomes a more subjective

figure, older and wiser, with a universal dimension: almost an Everyman.

The second part of the poem follows on from the first with the story of Martn Fierro 's life with an Indian tribe,

with his companion Cruz, who dies there, and his return to his own country. After this come long separatestories told by Fierro 's two sons and by Cruz's son (one the celebrated episode with old Viscacha), then the

curious lyricalpayada, or singing contest, between Martn Fierro and a challenger (who turns out to be thebrother of the man Fierro killed in Part One); and finally a concluding passage of aphoristic wisdom. La Vuelta

had no more of a literary success, and no less of a popular one, than the first part. It was printed in ever-

increasing numbers, and by the end of the century there had been more than twenty editions of the two partstogether.

*

Hernndez's concern with social justice for the gauchos is expressed as strongly as ever in the second part of thepoem. In other ways however, he had by that time grown nearer to Sarmiento's "progressive" ideals (just as

Sarmiento grew to have increased respect for the values of the land and its people). In 1880, when Buenos Aireswas finally voted official capital of the nation, Hernndez supported the motion in a long speech in Congress,

urging the development of the country along the lines of the North American states, to take its place ininternational affairs. For this attitude he has been accused of disloyalty to Federalism, but in the same speech he

warns against the obstacles created by excessive party-feeling in a nation emerged so recently from the bitter

experience of civil wars. His positive loyalties remained consistent: it is always the land and its people that he

urges to be considered foremost as the basis of the nation's strength and wealth. In 1884, when he was Senator,

Hernndez was invited to tour the world studying cattle breeding at government expense. He refused, on thegrounds that improvement should begin at home, and instead wrote a handbook of ranch management,

Instrucciones del Estanciero -- the other work of his that is still read, reminiscent ofMartn Fierro in its

aphorisms and good sense.

Hernndez died in 1886, aged fifty-two, of a heart attack caused, according to some accounts, by chagrin atthe state of the country. His last words, reported by his brother, were "Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires..."

Living through a period of the virtual formation of a modern state. Hernndez must indeed have suffered from

seeing unique chances frustratingly lost; in what he cared most about, the land, he saw the extinction of thegauchos' old way of life with no planned settlement to take its place -- to this day in Argentina, the capital and

the interior are separate worlds, and their voices still seek a true synthesis in government. But throughout hislife, in a chronically unstable political scene where he was more often than not in the minority, Hernndezseems to have possessed the vital quality of persistence: managing to survive, and taking any opportunity to

press his cause regardless of the likelihood of immediate success. He, and still more his spokesman Martn

Fierro, voice a spirit of the land that is still valid, even though the gaucho's life as Hernndez knew it has

disappeared with the isolation that formed it.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

10/112

AlthoughMartn Fierro continued to be reprinted, it was not established as the national classic it is today until

1913, when it was first studied seriously as an example of epic literature by Leopoldo Lugones, in a series oflectures collected in his bookEl Payador(The Singer.). It is now firmly ensconced in the Argentine school

curriculum, and is worked hard as a national institution. Quotations from it appear on advertisement hoardings,and it provides ornamental mottoes for suburban villas; editions appear continually, new artists illustrate it, and

no critic escapes his obligation to opine on it. It has become a classic: to be bored with, to react against, or to

rediscover.

Antonio Berni (1907-1981): Pampa (private collection )

Note on the Translation

The difficulties of translatingMartn Fierro must be obvious. As it in written in a language unique to its

geographical and historical circumstances, no dialect of another language could be entirely appropriate: evenwith a similar background (as with North American cowboys, for instance); the inherited traditions, religion,

etc., would alter the type of images used.

In this translation (originally with a bilingual edition in mind) the aims have been, in this order: (a) to followthe text as closely as possible, especially in the imagery; (b) to make the translation read fluently in current but

neutral (i.e. non-dialect and international) English; (c) to keep a rhythm in the translation giving an idea of theshape and movement of the original. The poem is written almost entirely in six-line rhymed stanzas, with

almost invariably a strong pause at the end of every second, fourth, and sixth line, so that the lines fall into pairs.

In this translation those six lines are printed as three long divided lines: with very few exceptions each long line

in English corresponds to two short lines in the Spanish, though for the sake of fluency the order of phrases maybe rearranged. This should help readers whose Spanish is limited or who are unfamiliar with River Plate idioms,

towards reading the original. For this reason too, closeness to the text was given priority over trying to findrhyme or strict rhythm in English (an English translation with these priorities reversed already exists in Walter

Owen's of 1933, which renders the poem's colloquial element often very successfully, though arguably not its

poetic dignity).

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

11/112

The translation follows the original punctuation with the dashes which Hernndez used freely to mark pauses --particularly before the last two lines of a stanza where a proverb often comes as a punch-line. Images have been

translated directly wherever possible, though sometimes expanded to make the point of comparison clearer.Where there is any considerable departure from the original, the literal translation is given in a note. Exceptions

are cases where there is a saying in English with nearly precise equivalent meaning (e.g. "by the skin of my

teeth" for con el hilo en una pata). Untranslateable jokes (e.g. at 1/5/11) are explained in notes, attempting to

show the type of humour in the original even if there is no equivalent. In general, words in Spanish have beenavoided except when they have no translation (such as poncho and mate), or have an important specific meaning(criollo), with the names of some animals.

Frequently used general terms (gaucho, indian, pampa, christian) have not been given capital letters. Capitalshave been used for abstract concepts (Law, Government) or words alien to gaucho life that the narrator may be

emphasising, sometmes ironically. "Negro" (probably less offensive in Spanish) has been replaced by "black" or

the humourous "darky", except for the protagonist of the singing contest at II.30 which has been left as in the

original.

An earlier version of this translation, edited by the State University of New York, Albany, NY, was published in1967, courtesy of the Pan-American Union in Washington, with illustrations by Antonio Berni. It has also beenused for an edition in English accompanied by works by Argentine painters, published by the Zurbaran Gallery,

Buenos Aires, in 1996.

Pronunciation

The chief characteristics of pronunciation in Argentine (River Plate) Spanish are as follows.

c followed by e or i , and z, are pronounced as s (cinco, zorro).ll (double l) and y pronounced 'zh' as French 'j' or hard as 'dg' in 'bridge' (yo, criollo).

Other dialect pronunciations are frequently (not invariably) imitated in the spelling of the original poem,

e.g: s for x (esplico for 'explico'); f for sb (refalarfor 'resbalar'); j for sg (dijusto for 'disgusto'); j for f (juertefor 'fuerte'); gu for h (guella for 'huella'); gu for b (gueno for 'bueno'); gu for v (guelta for 'vuelta'); l for d

(alvertirfor 'advertir'); also -ao for -ado (encontrao for 'encontrado'). Words can be shortened (virtu for'virtud', dotorfor 'doctor', inorarfor 'ignorar',pa for 'para', ay for 'ahi', etc. )

Books consulted

Francisco I. Castro: Vocabulario y frases de 'Martn Fierro'. Editorial Kraft, Buenos Aires, 1957 (2nd ed).

Editions of Martn Fierro by: Santiago Lugones: Ediciones Centurin, Buenos Aires, 1948 (2nd edition);

Eleuterio F.Tiscornia: "Coni", Buenos Aires, 1951 (with commentary and grammar); Carlos Alberto Leumann:Angel Estrada, Buenos Aires, 1945. Facsimiles of first editions: Ediciones Centurin, Buenos Aires, 1962.

Translations: Walter Owen: Blackwell, England, 1933, and Editorial Pampa, Buenos Aires, 1960.

Henry Alfred Holmes: Hispanic Institute in the United States, New York, 1948.

Enrique Herrero (ed.): Prosas de Jos Hernndez, Editorial Futuro, Buenos Aires, 1944.Leopoldo Lugones:El Payador. W.H.Hudson: Far Away and Long Ago.

C.E.Ward (1967)

Kate Ward Kavanagh (2007)

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

12/112

MARTN FIERRO THE GAUCHO *

1

Here I come to sing to the beat of my guitar:because a man who is kept from sleep by an uncommon sorrow

comforts himself with singing, like a solitary bird.

I beg the saints in heaven to help my thoughts:

I beg them here and now as I start to sing my storythat they refresh my memory and make my understanding clear.

Come, saints with your miracles, come all of you to my aid,

because my tongue is twisting and my sight growing dimI beg my God to help me at this hard time.

I have seen many singers whose fame was well won,and after they've achieved it they can't keep it up --it's as if they'd tired in the trial runs* without ever starting the race.

But where another criollo* goes Martin Fierro will go too:

there's nothing sets him back, even ghosts don't scare him --

and since everybody sings I want to sing also.

Singing I'll die, singing they'll bury me,

and singing I'll arrive at the Eternal Father's feet

out of my mother's womb I came into this world to sing.

Let me not he tongue-tied nor words fail me:

singing carves my fame, and once I set myself to sing

they'll find me singing, even though the earth should open up.

I'll sit down in a hollow to sing a story --

I make the grass-blades shiver as if it was a wind that blew:my thoughts go playing there with all the cards in the pack.*

I'm no educated singer, but if I start to singthere's nothing to make me stop and I'll grow old singing --

the verses go spouting from me like water from a spring.

With the guitar in my hand even flies don't come near me:no one sets his foot on me, and when I sing full from my heartI make the top string moan and the low string cry.

I'm the bull in my own herd and a braver bull in the next one;

I always thought I was pretty good, and if anyone else wants to try me

let them come out and sing and we'll see who comes off worst.

I don't move off the track even though they're out cutting throats:*

with the soft, I am soft, and I am hard with the hard,

and in a time of peril, no one has seen me hesitate.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

13/112

In danger -- by Christ! my heart swells wide:since the whole earth's a battlefield and no one need be surprised at that,

anyone who holds himself a man stands his ground, no matter where.

I am a gaucho, and take this from me as my tongue explains it to you:for me the earth is a small place and could be bigger yet --the snake does not bite me nor the sun burn my brow.

I was born as a fish is born at the bottom of the sea;

no one can take from me what I was given by God --

what I brought into the world I shall take from the world with me.

It is my glory to live as free as a bird in the sky:

I make no nest on this ground where there's so much to be suffered,

and no one follows me when I take to flight again.

In love I have no one to come to me with quarrels:

like those beautiful birds that go hopping from branch to branchI make my bed in the clover and the stars cover me.

And whoever may be listening to the tale of my sorrows know that I never fight nor kill except when it has to be done,

and that only injustice threw me into so much adversity.

And listen to the story told by a gaucho who's hunted by the law;who's been a father and husband hard-working and willing --

and in spite of that, people take him to be a criminal.

NOTES to I.1.

TITLE] Gaucho] Historically, as a social class, gaucho means the countrymen who were born and lived on the pampa plain,originally descendents of Spanish settlers with the more approachable of the native Indians from the north of the country. In

earlier times they lived off the herds of wild cattle and horses introduced by the settlers, selling hides etc.; later as the landbecame more controlled, by working on the estancias (ranches). Gaucho in common speech is more a description of thecharacteristics evolved from this way of life: horsemanship and skill in dealing with cattle, courage and total self-reliance in

their isolated primitive life. As fighters the gauchos were typically fierce, following their own laws of honour and chosenleaders; hence they were a considerable force during the nineteenth-century struggles for power in the land the dictatorship

of Rosas (1835-52) was founded on their loyalty to him. To city people gaucho was often a synonym for barbarism, but withtime the less violent aspects of gauchos prevailed in popular imagination, and by extension gaucho comes to be a descriptionof anything strong and simple, well-done or well-made. A gauchada in modern Argentine slang means the action of a friend,

doing a favour. There are diverse theories of the origin of the name; one being from guacho, orphan (see note to I.11.7).

I.1.4] trial runs] Local horse-racing was a big event in gaucho life (see II.11). There may also be a reference here to earlierwriters on "gaucho" themes who were disheartened by the disapproval of literary circles in the city.I.1.5] criollo ("criOZHo")] native Spanish-American. It comes to mean true countryman, as opposed to immigrants

(gringos) and Europeanised city-men. (See I/12/12, II/12/18 etc)

I.1.8] cards in the pack] Literally "Coins, Cups, and Clubs" (suits from the originally European card pack).I.1.12] cutting throats] Prisoners and wounded were commonly killed off after a battle. Throat-cutting was the preferredmethod with gauchos as with Indians. There is a horrifying account of this in W.H.Hudson's Far Away and Long Ago(chapter 8). (See also I.3.54)

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

14/112

2

No one speak of sorrows to me because I live sorrowing;and nobody should give himself airs even though he's got a foot in the stirrup --

even the gaucho with most sense often finds himself left on foot.

You gather experience in life, enough to lend and give away,

if you have to go through with it between tears and suffering because nothing teaches you so much as to suffer and cry.

Man comes blind into the world with hope tugging him on,and within a few steps, misfortunes have caught him and beat him down....

La pucha --* the hard lessons Time with its changes brings!*

*

I have known this land when the working-man lived in it

and had his little cabin and his children and his wife...It was a delight to see the way he spent his days.

Then... when the morning star was shining in the blessed sky,

and the crowing of the cocks told us that day was near,a gaucho would make his way to the kitchen... it was a joy.

And sitting beside the fire waiting for day to come,he'd suck at the bitter mate* till he was glowing warm,

while his girl was s1eeping tucked up in his poncho.*

And just as soon as the dawn started to turn red,

and the birds to sing and the hens come down off their perch,

it was time to get going, each man to his work.

One would be tying on his spurs, someone else go out singing;

one choose a supple sheepskin, one a lasso, someone else a whip and the whinneying horses calling them from the hitching rail.

The one whose job was horse-breaking* headed for the corral,

where the beast was waiting, snorting fit to burst wild and wicked as they come* and tearing itself to bits.

And there the skilful gaucho, soon as he'd got a rein on the colt,

would settle the leathers on his back and mount him straight away...A man shows, in this life, the craft God gave to him.

And plunging around the clearing, the brute would tear itself upwhile the man was playing him with the round spurs, on his shouldersand he'd rush out squirming with the leathers squeaking loud.

Ah, what times they were! you felt proud to see how a man could ride.When a gaucho really knew his job, even if the colt went right over backward,

not one of them wouldn't land on his feet with the halter-rein in his hand.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

15/112

And while some were breaking-in, others went out on the landand rounded up the cattle and got together the horse-herds and like that, without noticing, they'd pass the day, enjoying themselves.

And as night fell, you'd see them together again in the kitchen,

with the fire well alight and a hundred things to talk over they'd be happy, chatting together till after the evening meal.

And with your belly well filled it was a fine thingto go to sleep the way things should be, in the arms of love

and so to next day, to begin the work from the day before.

*

I remember--- ah, that was good! how the gauchos went around,

always cheerful and well mounted and willing for work...But these days--- curse it! you don't see them, they're so beaten down.

Even the poorest gaucho had a string of matching horses,he could always find some amusement, people were ready for anything....Looking out across the land you'd see nothing but cattle and sky.*

When the branding-time came round that was work to warm you up!

What a crowd! lassooing the running steers and quick to hold and throw them....

What a time that was! in those days for sure you'd see some champions.

You couldn't call that work, it was more like a party

and after a good throw when you'd managed it skilfully,

the boss used to call you over to give you a swig of liquor,

because the great jug of booze* always lived there under the cart,

and anyone who wasn't shy, when he saw the open spout

would take a hold on it fearlessly as an orphan calf to the teat.

And the games that would get going when we were all of us together!

We were always ready for it, as at times like thosea lot of neighbours would turn up to help out the regular hands.

For the womenfolk, those were days full of hurry and bustlingto get the cooking done and serve the people properly...

And so like this, we gauchos always lived in grand style.

In would come the meat roast in the skin and the tasty stew,cooked maize well ground, pies and wine of the best...But it has been the will of fate that all these things should come to an end.

A gaucho'd live in his home country as safe as anything,

but now -- it's a crime! things have got to be so twisted

that a poor man wears out his life running from the authorities.

Because if you set foot in your house and the Mayor finds out about it,

he'll hunt you like a beast even if it makes your wife miscarry....

But there's no time that won't come to an end nor a rope that won't break sometime.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

16/112

And you can give yourself up for dead right away, if the Mayor catches you,because he'll come down on you there and then, with a flogging --

and then if a gaucho puts up a fight they call him a hard case.

They'll bruise your back with beating and break your head open for you,and then without any more ado, bleeding as you are and all,they lash your elbows together and head you for the stocks.

That's where your misfortunes start, and that's where the dance begins

because now there' s no saving you, and whether you like or not

they send you off to the frontier,* or sling you into a regiment.

That was the way my troubles began, the same as many another's.

If you like, I'll tell you... in more verses, what I've gone through.

Once you're done for, you can't be saved, not even by the holy saints.

NOTES to I.2I.2.3] la pucha!] common euphemism forputa (whore)I.2.6] mate] (two syllables) a strong green tea made in a small gourd or pot (a mate) and sucked through a perforatedmouthpiece (bombilla). A stimulant and essential vitamin source for meat-eaters.

his girl] china, meaning indian woman, affectionately extended to any criolla country girl. Legal marriage wasuncommon.

poncho] made of two strips of cloth sewn with a space for the head, generally striped and fringed, essential equipmentas a cloak, blanket, or in fighting. See I.7.18; I.9.19-30, etc.I.2.9] horse-breaking] the gaucho method was to dominate and exhaust the horse by force and good balance. A good

domadorwas immensely respected. See II.10 for the alternative method with the indians.

wicked as they come] literally, "worse than your grandmother".I.2.17] nothing but cattle and sky] the flat treeless pampa, technically the plain of rich soil extending 300 miles inland and tothe south of Buenos Aires city (the "dry pampa", more barren and less flat, extends beyond this, towards Patagonia in thesouth and the Andes mountains in the west). This was before its division with fences and more plantations.I.2.19] liquor] caa, cane-liquor. Jug of booze in the next verse, in the original a pun replacing damajuana (demijohn) withmamajuana (mamar= get drunk).

I.2.23] roast in the skin] a delicacy. Meat was roasted on an upright spit leaning over an open fire.I.2.25]Mayor] the civil authority in country districts, under the Judge.Mayor,Judge, and Commandant(of the militia) are

virtually interchangeable in the poem as representives of corrupt authority.

I.2.28]frontier] frontier forts against the land still occupied by indians, manned by recruited soldiers.

3

In my part of the land, at one time, I had children, cattle, and a wife;but my sufferings began, they pitched me out to the frontier and when I got back, what was I to find! a ruin, and nothing more.

I lived peacefully in my cabin like a bird in its nest,my beloved children were growing up there at my side....

When you're unhappy, all that's left you is to mourn for good things that are lost.

What I enjoyed, in a country store* when there was most of a crowd

was to warm myself up a bit -- because when I've had a drink

the verses come from inside of me like water from a waterfall.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

17/112

One day, there I was singing in the middle of a big party,and the Justice of the Peace* thought he'd make the most of the occasion

he appeared on the scene, and there and then he had the whole crowd rounded up.

The ones who knew best got away and managed to escape:I didn't want to run off -- I'm a quiet one, and there was no reason I stayed there quite calmly and so I let myself get caught.

There was a gringo*with a barrel-organ and a monkey that danced

who was making us laugh when the round-up came to him --

a huge fellow he was, and ugly! you should have seen how he cried.

Even an Englishman ditch-digger* who'd said in the last war

that he wouldn't do the service because he came fromInca-la-perra

he had to escape as well and take cover in the hills.*

Not even the people looking on were spared from this bumper catch;

the singer was yoked together with the gringo who had the monkey only one, as a favour, the storeman's wife got to save.

They formed up a troop of recruits with the men they'd caught at the dance;they mixed us in with some others that they'd grabbed as well....

Even devils didn't think up the things you see going on here.

The Judge had taken against me the last time we had to vote.*I'd played it stubborn and I didn't go near him that day --

and he said I was working for the ones in theproposition.*

And that's how I suffered the punishment for someone else's sins, maybe.

Voting lists may be bad or good, I always keep out of sight

I'm a gaucho through and through and these things don't satisfy me.

As they sent us off, they made us more promises than at an altar.

The Judge came and made us speeches, and told us many times,

"In six months' time, boys, they'll be going out to relieve you".

I took a classy dark roan --* a real winner he was, the brute!With him in Ayacucho* I won more money than there's holy water --a gaucho always needs a good horse to get him a bit of credit.*

And without any more ado I loaded up with the gear I had:

saddle-rugs, poncho, everything there was in the house, I took the lot I left my girl that day with hardly a shirt to her back.

There wasn't a strap missing, I staked all I had, that time:halter, tether, and leading-rein, lasso, bolas, and hobbles....

People seeing me so poor today won't believe all this, maybe!*

*

And so, with my dark roan tossing his head I made for the frontier.

I tell you, you ought to see the place they call a fort --I wouldn't even envy a mouse who had to live in that hole.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

18/112

Of all the wretched men who were there they hadn't let one go free.The older ones grumbled, but when one made a complaintstraight away they staked him out* and that was the end of that.

At the evening roll-call the Chief showed us his hand,

saying, "Anyone who deserts will get five hundred straight.We won't pull any punches he'll find he'd be better dead."

They didn't give arms to anyone because the whole lot there werewere being kept by the Colonel (so he said on that occasion)

so as to hand them out on the day if an invasion came.

At first they left us to laze around and grow fat,but afterwards -- I daren't tell you the things that happened next.

Curse it! they treated us the way you treat criminals.

Because they'd go hitting you with their swords, on your back

even though you weren't doing anything it was bad as in Palermo,*

they'd give you such a time in the stocks that it would leave you sick.

And as for indians* and army service -- there wasn't even a barracks there.

The Colonel would send us out to go and work in his fields,and we left the cattle on their own for the heathens to carry off.

The first thing I did was sow wheat, then I made a corral;I cut adobe for a wall, made hurdles, cut straw....la pucha! how you work and they don't even throw you a cent.*

And the worst of all that mess is that if you start to get your back up,they come down on you like lead... Who'd put up with a hell like that!

If that's serving the Government I don't care for the way they do it.

*

For more than a year they kept us at this hard labour;

and the indians, you may be sure, came in whenever they liked as nobody went after them they were never in any hurry.

Sometimes, when the look-out patrol came back from the plain, they'd saythat we ought to be on the alert, the indians were moving in,

because they'd found some tracks or the carcass of a mare.*

Only then the order would go out for us to form a line,and we'd turn up at the fort bareback, even two aback,unarmed -- half a dozen poor beggars going out just to get scared.

And now the fuss began, all for show, naturally,

of them teaching army drill to the crowd of gaucho recruits,

with an instructor, a... foo1 who'd never learnt his job.

Then they'd give out the arms to defend the fortifications,

which consisted of pikes and old swords tied together with strips of hide --

the firearms I don't count because there was no ammunition.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

19/112

(And one of the sergeants, when he was drunk, told me they did have some,but that they used to sell it for hunting ostriches --so that was how they went day and night blasting away at the birds.)

And when the indians went off with whatever they'd looted,

we'd set out in a great hurry chasing after them if they didn't take more with them it's because they hadn't found it.

And there truly you see misfortune and tears and sufferings.No one asks the indians for mercy -- where they break in

they'll steal and kill all they come across and burn down the settlements.

Even the poor little angels aren't saved from their fury --old men, boys and children, they kill them all in the same way --

an indian fixes everything with his spear and a yell.

Your flesh shakes to see them, their manes flying in the wind,

reins in their left hand and spear in the right

they break through wherever they turn, as there's no spear-thrust goes wide.

They ride tremendous distances from deep inside the desert,

and so they arrive half dead of hunger and thirst and fatigue --but an indian's like the ant that stays awake night and day.

He knows how to handlethe bolas* as no one else can handle them as his enemy moves away he'll sling off a loose ball,and if it reaches him it won't leave him alive.

And an indian is tough as a tortoise, to finish off if you do get to spill his guts it won't even worry him,

he'll stuff them back in a moment, hunch down and gallop away.

They used to plunder as they pleased and then went off scot-free.They took the captive women with them, and we were told that sometimes

poor women, they used to cut the skin off their feet, alive.

Curse it, if your heart didn't break seeing so many crimes!

Not even able to gallop we'd follow them far behind --and how could we have caught up with them on those broken-down old nags!

After two or three more days we would turn back to the fort

with our horses dropping by the road -- and so that someone could sell it,

we'd round up the cattle they'd left straggling behind.

*

Once, out of the many times when we rushed out uselessly,

the indians landed on us with such a raid and a spear-attack

that from that time onwards people lost their nerve.

They'd been hiding in ambush, behind some higher ground.

You should have seen your friend Fierro flinching as if he was soft!

They shot out like popcorn the moment a cow-bell rang.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

20/112

Although there were a good many of them we took our stand where were.In a moment we formed up the few men that we had and they charged us in a line beating their mouths with their hands.

They came on in a stampede that made the ground shake....

I'm not lame when there's fighting to be done, but I was in a sweatbecause I was riding a half-wild horse that I'd caught in the hills.

What a yelling, what a racket! what a rate they moved at!The whole of that indian band landed on us howling --

pucha! they scattered us like a herd of wild mares.

And the mounts those heathens had! like a flash, they were so fast.They clashed into us, and then in the confusion

take one -- leave one -- they picked us off with their spears.

Anyone who gets lanced by them is not likely to recover....

Finally, to make the story short, we got out of those hills

like a flock of pigeons flying away from hawks.

You have to admire the skill of the way they handle a spear.

They never give up a chase and they pressed close after us --we were in such a hurry we could have jumped over the horses' ears.

And just to add to the fun at the height of this danger,up came an indian frothing at the mouth with his spear in his hand,yelling out, Christian finish! Spear go in up to feather!*

He rushed at me screaming stretched flat along the horse's ribs,brandishing over his arm a lance long as a lassoo

one false move, and that devil will have me off with a swing of the shaft.

If I lose my head or hesitate I won't escape, that's certain.I've always been pretty tough, but on that occasion

my heart was bumping like the throat of a toad.

God forgive that savage the way he wanted to get me....

I got out my Three Maries* and led him on, dodging round --pucha! if I hadn't had bolas he'd have had my guts that day.

He was the son of a chieftain according to what I found out --

the truth of the matter was he had me very worried indeed --

till finally, with a bolas-swing I got him down off his horse.

I threw myself off right away and stood on his shoulder-blades.

He started making faces and trying to hide his throat --but I performed the holy deed of stretching him out cold.*

There he stayed as a landmark and I jumped on his horse.I made off fast from the indians as if they caught me, it meant death --and in the end I escaped from them by the skin of my teeth.*

NOTES to I.3I.3.3] country store]pulpera, the centre of social activity in country settlements.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

21/112

I.3.4]Justice of the Peace] or Judge see note at I.2.26.I.3.6] gringo] a foreigner, in Argentina at that time an immigrant, often Italian, also British (including Irish).

I.3.7] ditch-digger] ditches were for draining, or on boundaries instead of fencing. (There was an abandoned scheme for agreat ditch to defend the frontier.)

Inca-la-perra]Inglaterra=England;perra=bitch. A common type of joke with an unfamiliar word deliberately

mispronounced to make it incongruous or suggestive. Other examples at I.5.9; II.16.2, etc.hills] the typical pampa is dead flat until its more "desert" outskirts are reached (see note at I.2.17). There is a small

range of hills at Tandil, about 200 miles south of Buenos Aires.

I.3.10] had to vote] voting is obligatory in Argentine elections.proposition] humorous mistaken word, as at II.24.4, etc.

I.3.13] dark roan] literally, moro ("Moor"). Technically, black with a few white hairs giving purple lights to the coat. Dark-coloured horses were highly prized; Viscacha's horse was a moro (II.14.3) and the indian's (II.10.3) "a black without amark". See also note at II.13.2.

Ayacucho] a town in Buenos Aires province.

a bit of credit] i.e. to bet on.I.3.15] bolas] see note at verse 36 below.

seeing me so poor] a gaucho's harness and equipment were the sign of his wealth.I.3.17] staked him out] see I.5.13 for a description of this punishment.I.3.18]pull any punches] literally, "make him smoke strong tobacco".I.3.21] Palermo] residence of the tyrant Rosas (ruled 1835-52) on the outskirts of Buenos Aires.I.3.22] indians] the "indians " inMartin Fierro are the Pampa indians, one of several nomadic tribes originating with the

Araucanas of Chile, that spread eastwards as the horses and cattle abandoned by the first Spanish explorers multiplied intowild herds. They adopted the horse and lived almost entirely on near-raw meat and blood (details in this canto and in Part II,

cantos 2-10, are accurate). Other Amerindian populations with more knowledge of agriculture, etc. (more "civilised") were

in the north-west (on the fringes of the former Inca empire), cruelly exploited by the Spanish, and the Guaranes in the north-east (from what became Paraguay), who mingled with settlers after the Jesuit settlements were abandoned. The Pampa

indians were never "civilised" and the government was never strong enough to contain them. They encroached increasinglyuntil in the expeditions under General Rocas in 1879 and 1883 they were exterminated; survivors were forcibly resettled.

(See II.15.12.) A classic first-hand account, near-contemporary with the poem, isExcursion to the Ranquele Indians by

Lucio V.Mansilla, published in 1870.I.3.23] cent] real, a small coin.

I.3.26] carcass] the indians habitually ate horse-meat.I.3.36] bolas] or boleadoras, originally an indian weapon, adopted by gauchos. 3 (sometimes 2) balls of stone covered withleather are attached to joined plaited ropes; one (generally shorter) held in the hand, the others whirled and sent flying. Forthe bolas in action, see verses 52-53, and II.9.5-31.I.3.49]feather] i.e. the tuft of feathers behind the spear-head.I.3.52} Three Maries] the three balls of the bolas (from the name for the stars in Orion's Belt see I.9.11).I.3.54] stretching him out cold] literally, "making him stretch out his muzzle" (see also I.9.42).

I.3.55] by the skin of my teeth] literally, "with the string still round my leg".

4

I'll carry on with this story though it's too long by half ...

Just imagine, if you can, how I'd be on my guardafter I'd saved my skin from a danger cruel as that one

I won't be telling you about our pay, because that kept well out of sight.At times we'd reach the state of howling from poverty the cash never got to us that we were hoping for.

And we went around so filthy it was horrible to look at us.I swear to you, it hurt you to see those men, by Christ!

I've never seen worse poverty in all my bitch of a life.

I hadn't even a shirt nor anything that was like one

the only use my rags were in the end, was to light the fire...

There's no plague like an army fort to teach a man to endure.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

22/112

Poncho, saddle-rugs, harness, my clothes, the coins off my belt,*I tell you, the whole lot got left one by one, in the barrack-store ...The rats and the poverty had got me half crazed by now.

Only one rough blanket was all that was left to me.

I'd acquired it playing taba,* and that just served to cover me ...The lice that got in there wouldn't leave -- not even with a free pardon.

And on top of that, even my dark roan slipped from out of my hands.I'm not a fool, but I tell you, brother ... the Commandant came up one day,

saying he wanted him, "to teach him how to eat grain."*

So imagine, anyone, the state your friend here was in:on foot with his navel showing, poor and naked and worn out --

they couldn't have treated me worse even as a punishment.

And so the months passed by and the next year came,

and likewise, everything went on just as it did before

all done on purpose, seemingly, to drive the men there mad.

We gauchos weren't allowed to do anything of our own

except to go out at dawn when no indians were around,to hunt with bolas in the open country and ride the Government horses lame.

And we'd turn up at the camp with our mounts done in,but someimes pretty well provided with feathers,* and a few hides,that we'd trade in right there with the keeper of the store.

*

The man who kept the store was a friend of the Chief.

He gave us mate and tobacco in exchange for the ostrich-feathers --

even a glint of silver, if you'd brought him a hide.

All his stock was a few bottles and some barrels with nothing in them,

and yet he'd be selling people anything they required --some of them believed it was the Quartermaster's store he had there.

He never went short of a thing, that crafty trader, curse him!and as for greed, he'd swallow anything, just like an ostrich

the men used to call it the Store Where Anything Goes.*

Although it's fair that the man who's selling should bite off a bit for himself,he stretched the point so far that with those four bottles he hadhe loaded up whole carts-full of feathers and horse-hair and skins.

3_He had us all noted down with more reckonings than arosary,

when they announced a payment or an Advance they were going to give out,

but the Lord knows who the fox was ate that up at the Paymaster's.

Because I never saw it come, and a good many days after that,

in the same store-house, they gave a credit

which people accepted, very pleased to get this small amount.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

23/112

Some of them took out their clothes which they'd got there in pawn,others gave up the money for debts which were overdue ...When the party was done, the store-keeper was left with the whole heap.

*

I leant back against a post giving them time to pay,and putting a good face on it I was acting dumb,

waiting for them to call me to collect my dole.

But I might just as well have stayed there stuck to that post for ever.

It was almost evening-prayer time and nobody called me ...Things were looking murky, and I began to feel uneasy.

To get rid of my hunger pains I saw the Major, and went up to him.

I started edging up to him, and pretending to be shy I said,"Maybe tomorrow... they'll finish paying us?"

"What d'you mean, tomorrow!" he answered back right away."The payment's finished now, trust you to be a greedy brute!"I gave a laugh and said, "I.... haven't even had a cent."

He opened his eyes so wide they nearly fell off his face,

and right there he said again staring fit to eat me up,

"So what do you expect to get if you haven't got on the list!"

"This is a fine way to make a mess of things," I said to myself privately,

"It's two years I've been here and I've seen not a cent so far.

I get into all the fighting but I don't get onto the list!"

I could see it was a tricky case, and didn't want to wait any longer.

It's as well to live peaceably with whoever's in command of us

and so, retreating backwards, I started to move away.

The Commandant heard all about it and called for me next day,

telling me that he wanted to get things straightened out --that this wasn't like Rosas's time,* no one was left owing these days.

He called the Corporal and the Sergeant and the inquiry began whether I'd come to the camp at this time, or the other,

and whether I'd come on a colt of my own, or a government horse, or a wild one.

And it was all a lot of fuss about nothing, and play-acting.I could see it was all a trick for them to get fat on my purse -but if I'd gone to the Colonel they'd make me complain at the stakes.

The sons of bitches I hope their greed will split them down the seams.

Not even a bit of tobacco do they give the poor recruit,

and he's skinny as a mountain deer,* they keep him so underfed.

But what could I do against them, like an ostrich-chick in the wilds!

All I could do was give up for dead so as not to be worse off still ...

So I acted sleepy in front of them, though I'm pretty well wide awake.

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

24/112

NOTES to I.4I.4.5] coins off my belt] or "buttons" of silver or gold, the gaucho's money reserve. (See also I.7.3, II.22.6.)

I.4.6] taba] a dice game, using a cow's knuckle-bone.I.4.7] to eat grain] i.e. a high-class diet.I.4.11]feathers] ie. ostrich feathers.

I.4.14] Where Anything Goes] literally, "the store of Virtue".I.4.16] reckonings] cuentas, meaning both "beads" and "accounts".I.4.26]Rosas's time] The recent dictator, famed for rough justice. (See Introduction, and I.3.21.)

I.4.29] mountain deer] guanaco.

5

I was getting hopeless, waiting for an opportunitywhen the indians would raid us, so that in the confusion

I could turn outlaw on them and go back to my home.

You couldn't call that service nor defending the frontier,

it was more like a nest of rats where the strongest one plays the cat it was like gambling with a loaded dice.

Everything there works the wrong, way round, soldiers turn into labourers,and go round the settlements out on loan for work

they join them up again to fight when the indian robbers break in.

In this merry-go-round, I've seen many officers who owned land,with plenty of work-hands and herds of cattle and sheep I may not be educated but I've seen some ugly deals.

And I take it they're not interested in getting things put straight --

if it was for that, the officer even though he stays there in charge,

would need no more than his poncho and sword, and his horse and his duty.

And so, then, when I saw there was no curing that disease,

and that if I stayed there I'd maybe find my grave,

I thought the safest thing would be to make a move.

*

And then on top of it all, one night what a staking-out they gave me!

They nearly pulled me out of joint all because of a little quarrel --

curse it, they stretched me out just like a fresh hide!

I never shall forget how it happened to me that time.

One night, I was coming in to the fort when one of the regulars,On duty, who was fairly drunk -- failed to recognise me.

He was a gringo who talked so thick no one understood what he said.

Lord knows where he can have come from! he wasn't Christian, probably,as the only thing he said was he was a Pap-oli-tano.*

-

7/22/2019 Martin Fierro Epic of the Gaucho

25/112

He was on sentry-duty, and on account of the drink he'd hadhe couldn't see me too well and that was all there was to it --the fool got a fright about nothing and I was left to pay the bill.*

When he saw me coming he called out Who dere!

I dare, I answered -- Ands oop! he screamed at me and I said, very quietly, Andthe soup's what you'll end in!*

Just then -- Christ save me! I heard the gun-catch click.I ducked, and that moment the brute let off a shot at me

being drunk, he fired without aiming, or I wouldn't be telling the tale.

No need to say, at the sound of the shot the wasps' nest started buzzing.Out came the officers, and so the fun began --

the gringo stayed at his post and I went to the staking-ground.

They stretched me on the earth between four bayonets.

The Major camealong, fairly stinking, and started screaming out,"I'll teach you, you devil, to go around claiming pay!"

They tied four girth straps to my hands and my heels;

I put up with their hauling without letting out a squeak,and all through the night I cursed that gringo, till I wore him out.

*

I don't know why the Government sends us, out here to the frontier,

these gringos that don't even know how to handle a horse --