Krell Glandula Pineal Descartes Merleau-ponty-bataille

-

Upload

philobureau2598 -

Category

Documents

-

view

27 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Krell Glandula Pineal Descartes Merleau-ponty-bataille

omnipotence of historical materialism or the untranscendability ofdialectical reason.Thirdly, although Raymond Aron's reproach that Parisian Marxismwas Marxism for agrgs is quite unjusty63 it is the case that neitherSartre, nor Althusser, nor their respectlve followers, furnished the'concrete analysis' of the French situation their reconstructions weresupposed to facilitate and for which they had called. The inqlieationsof this for the political project and reputation--of their Marxlsm need

finally - it can be said that whilst Sartre andvery different ways! made enornous eontributionsto the de-stalinization of French Marxlsm, each then proceeded, afterhis own fashion, to tiklaoize' it. Their most serious tflirtations' were notwith Cartesianism or existentialism, Spinozism or structuralisp, butwith Maoism an involution which was theoretically retrogressive andpolitically perilous, the illusion of the Parisian epoch rapidly giving wayto a disillusionment from which French Marxism has never recovered.If it is to recover, if the dialectic is to have further adventures, it willhave to avoid these or eognateerrors one of which, however, would betotally to renounce its past. For whatever the shortcomings of Sartre's,Althusser's, and modern French Marxism generally, it was never, as iscurrently fashionable to believe in Paris, a useless passion.b4

no underlining.Fourthly-and

Althusser, in their

Paradoxes of the Pineal'. FromDescartes to Georges BatailleDAVID I/ARRELL KRELI,

Illustrious Gentlemen of the Academy!You do me the honour of requesting tltat I sub:llit to tlle academy areport on ly earlier life as a1 ape gplc?'??J/J?'.$-t-/?t2-f b.,rllllel.)ellj .I?ranz lttf ka , 13-1-11 ./.a/it'/?/ r c/-??t? jlatlenlie

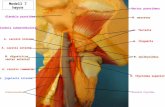

ventricle of the hunlan brain a l'liniscultt pedtlllculatebud, close to the optic thalamus, that is, tt) tlle tw'l) beds ()f optic nttrves,a gland soft in substance yct ctlntaining gritty partieles. Fultctitln :tlnknown. Because of its pine-ctlne slape it is called the collalilllllorpineal body, even though the recent phottlgraplls of it by Nilsstlll andLindberg slow it to be morpllologically relliniscent of notlling somueh as the plucked tail of a gamebird, wllicll Silnon I.lttdalus refers toas

tthe pope's nose'-! rroday it is presullled to be an elldtlcrine gland ofsome sort, evcn though there is no doubt tlltt lllorphogelltttically in a1lvertebrates it is a vestigial unpaired cye. As ftlssil cvidenctt illdicatesand we still find it almost fully developed i1 stllne extant allplibiansancestral vertebrates possessed in addition to tlle pairtttl hilatttral eyes asolitary dorsal eye opening at tle top ()f tlle sltull to thc sky. flAhissingular evagination of the braill--stlmetlliltgbctwixt a visual organand a gland seems to hold a special fascillation for pllilosophers. Herewe shall consider two of thena : Ren Descartcs ( 159 (y-165()) , tllc father,as we say, of modern philosophy ; alld Gctlrges Bataille ( 1897-1962) ,the father, as many say, of post-naodern jllilosophy. Tlree hundrcdyears separate thern. Devotion to the pineal body coljoins tlem.

Descartes knew nothing of the pillcal t?)'tr. lt was apparently only bythe mid-nineteenth eentury that the mtlrphogenesis of thc conariulnbeeame established. Yet vision prompted Ilcscarttls' clloice ()f tlltl glalldas seat of the soul, sige Jc lklle. l 1) lctters t() 'leysstlnjlicr (29 January

Behind the third

' See Lellnart lilsson and Jall 1wi l'ldilttrg, lholtl -1/t7// ( I3oston : Iwittle,Brown and Cofnpany, 1974) , 1 70. i'Inllc ptlllc's Ilosc' apllears ()f clltlrsc at thatfarnous Christlnas d i nner at the otltsttt ()f J tlyctt 's

l'Yt'llmal'tf?.

111(, -/1?*/?'./

a.% ?b'oung .t'1,.'//,?(l.l arlnondsvvorth : Pcngui 1, , l t.)6()) , 33 . C.() r) t ttlll ptlraryendocrinology appcars t() be making ctlllsiderable atlvallt-es 11) I-csrtrcll ()1'1 tllefunctions of tl3c pi ncal gland, but 1 sllall r1()t try t() tI() jtlstice t() t 11e111 llerc,where it is a cjuestion of I'arad ()x alll ('llscssitlll rat Ilt-r t Ilajl y'lllrsl'tlltdgy.

63 D'une Stz?'n! Famille J l'Autre Essais sur les slarxismes lmaginaires(Paris: Gallimard, 1969), 73, 78-79.:4 This lecture, draws on a book devoted to Louis Althusser, Althussev TheDetouroflheor.v (London: Verso, 1987). I would like to thank Sarah Baxterfor all her help,

David Farrell Krell

1640) and Mersenne (1 April 1640), as well as in the Treate t)?2 J/cPassions of the Soul ( 1645-46), Descartes recounted the principalattraction of the pineal body for him : it is the only part of thc bicameralbrain that is not duplex but singular, and its singularity, along with its

contiguity with the two beds of optic nerves, suggest its functionwhich is, as Descartes believes, to serve as what we today call thech-jf-m' of the optic nerves, that which integrates the two images our

yes receive into the one image we see. Descartes was quick to locate inthe pineal body t%esf-p--mpmmynis, then the imagination, and finally,though considerably less confidently, the rational soul itself.

H r five additional traits of la ycffc glande reinforceoweve ,Descartes' choice. Allow me to enumerate them, go on to discuss thegland's functions, and then finally state a number of paradoxes anddifficultiesl=eda-wit--wealy lh. onqlj-u-mt-self .

w jj kktion, inFirst, the singular gland occupies t e most appropr ate pos

the middle of the brain--azf milieu, says the Treatise (?/z the Passlhns ofthe Soul, fbetween

a11 the concavities'.z Yet it is important to noteDescartes' slight shift in point of view, or the slight shift of the glanditself : in the earlier, unpublished Treatise on Man (written in Frenchabout 1633-34, published posthumously by Clerselier in 1664)Descartes locates the gland at Sabout' environj the middle of the brain,specifying that it is

da bit removed from the centre'.3 lts position slightlyoff-centre will prove to be significant in terms of the gland's djj-erentialstructure and function, which 1 shall discuss in a moment. .

Second, the little gland is served by the carotid arteries, whichsupply the heart's blood and the rarified animal spirits to the brain. Thegland itself is the well-spring' of the animal spirits and is lightlysupported by these arteries. Thus its base is highly elastic, allowing thegland to incline in a1l directions, in order to eject les c.>r/'ly a3imaux toa11 the requisite locales. Elastic, agile, adroit, tle little gland is con-stantly in a state of agitatior and vital vibration.

Third, the gland is exceedingly soft and delicate in substance.(Descartes never mentions the grainy or sandy particles within, the gritthat as Socrates complains in Theaetetus often makes the wax slab ofmemory unfit for impressions.) Although the surface of the glandmust, as we shall see, be capable of sustaining certain convolutions,

2 See articles XXXI and XXXIV of the l'reate. l shall citc Descartes'Oeuvres et fzffrd-, Andr Bridoux (ed.) (Paris: Gallimard, Pliade, 1953),simply by page number in parentheses in the body of my text. I shall occa-sionally refer to the Adam-rranneryedition, cited it as Arf', with volume andpage numbers.

3 In the Pliade edition, p. 855; cf . AT, XI, p. 180. lt is important to refer toAT for the Treatise on Man and its integument, The Wbrfl, along with theeditors' Suzvertissement', in voltlfze XI of t hat elition .

folds or traces, so that tlle soul can read tllese marks and tlus cone to

know, these incisions ()f the surface dare not bt) exccssive, lest thevirginal gland become corrugated, rutted, rtlined . The glalld is soft in

11 human beings, explains Descartes to Iklttyssollllicr, ald not only ina

lethargics', as has been tlloug. ht since Platt). It is s() ctlrruptible or,one is tenpted to say, entirely i:) the spirit ()f Descartes, so volatile insubstance that it vanishes soon after death, Descartes urges s'leysson-nier, who suspects that the gland to which Descartes is so devoted is

mythological, not to wait three or four days before setting out in searchof it. Only the freshest cadavers will yieltl tlle pilleal to the dissector'sobservation.

Fourth, Descartes notes that tlltt ctlnariunl is tlle ()I11y part of thcbrain that is smaller in human beings tllall in anilnals, s(') tlat it is meetand just that it should be tlle seat of ilatellectitln. Yet thcre is somethingparticularly paradoxical about this fourth cllaracteristic

; lct tls pause a

moment to consider it.lt is of course usually the fnagnitudc ()f tllc llumarl brain that is

celebrated as a mark of distinction. k-lten'lAhomas Aquinas asks

whether the body of man is suitably disposcd lsumnla theologiae,1q91a3) he can justify the body's lack of tlick fur, sturdy carapace andnatural protections of all kinds, as wcll as its relatively (1ull senses andsluggisl locomotion, only by appealilag t() its adroit hand and laassive

brain. Utilas p/tzaz/z/zp and nlaximupl ccrc/a?-l/p? togcther constitutethe human organ t.?/rtz?z/wp/ or dtool of t()()ls'. I'l()w strange then that forDescartes the seat of intellection and agcncy shtluld be marked in factby a kind of devolution. For while the holninid brain cxpands in size,and while the olfactory sense claims lcss and less ccrebral spacc, stlrren-dering to that dproper end' wllicll i:t l'Iaapl is intellectioll, the citadel ofthe Cartesian rational soul, shrinking rather tllan expandilg, followsthe way of a1l flesl. llescartes thtls exptlses lliTnself t() Jack Shandy'sbarb : the great plilosopher chosc ltjeplbleal glalld ()f tle brain ; wllich,as he philosophized, formtttl a cushioll ftl1- ller gi .c. the s()tlll about the

,4size of a marrow pea .

To this paradox one Iuight addtlce otllcrs. l'Vilat is (lne t() Iuake ()f thegland's central off-centre position? Of its service as the twell-spring' ofthe spirits, which nolle tle less sprillg frtllu tlle llttart? Altt.l wllat isneto make of a source that can stretcl antl i ncline 7. S'Vllat about that softsubstance, like warrn wax, illcapablc ()f rctailliTlg irnllrcssions eventhough that is its principal function ? sVllat abtlut a sllrfacc botll virginaland visitcd ? Does n()t tlis warln stlft wax slcrifice a1l its secllndaryproperties, and its primary ()11e as well ? ''hlllt are A&.'tt t() nlakc ()f' that part

that volatilizes so soon after death, as though it were notthe mere cushfon of the soul, the cushion of the seat of the sedentarysoul, but the fugitive soul ftself ?Let us set aside these initial paradoxes of the pineal, in order to recallthe principal functions of tjzepetiteyange as oescartes recounts themin the Trait de jx.fowse. uany (jrtajls of that treatse conform to whatwe know from the 1637 Discouyse on go//ytytr/ and tjae Iater passits.Perhaps its most interesting feature is the attempt to leave the drationalsoul' altogether out of account. Here Descartes sets his machine de sa-eagoing, allowing it to run through a11 ts paces without the encumbranceof mind. Not only Malebranche but also hosts of future neurophysio-logsts will be fascinated and utterly eonvinced by this automaton.jEveryrational soul of the eighteenth nineteenth and twentieth cen-turies will be happy to Iet the torso of Descartes' Treatise end where tin fact ends-withoutthe contrivance, the scholastic baggage, of l'mez'tz?'loapp7/?/c.

of the cadaver

A this prototypical and paradigmatic text, we,know,is that t is part of a larger project on lkht, entitled The tipbstyajytreatiseand a world its author assures us that are altogeger-gcttjtvusjjychaptersix of he Icos/t begjns : 'permit our tlaought then to exft'jfromthe world awhile in order to come to see another altogether novelworld wlafeh ! slaall b fn to birth in its presence witlain imaynary',

1-jpr

spaces (AT xf J J) we shalj jaave occasion to remember these, ) .

imaginary spaces n whfch lhomme pyucypjs. antj tjje entfre motjerrjscience of physiology are brought to birth when we turn to GeorgesBataille's mythologcal anthropology. Iror the moment, let it suffice tojnotethat Descartes' own text is a kind of automaton a simulacrummime or hypomnetic of the world perhaps of the world of ecclesiastlical and court authorfty, itjelf a fabric of fictions, so that only a fctioncould rafse a claim to what is called ttruth'. Let us turn now toDescartes' fiction-science.The Treate (w uatt tejls us that the most vibrant, forceful andsubtle parts of the blood circulate among tlae concavities of the brain,jthereyielding a certain qufte subtle wind or rather, a very lively andvery pure flame to which tlae name antbnal .y.ljs/.q jjave been gjvens-s

These < ather ab' 'bg out ut also enter fnto and issue from a tiny glandalmost in the centre of the brain. A vast network of tubes allows thespirits Ih.B. : the short form is always spinwts,

never animay) to flow toal1 the regions of the brain, a11 the sense organs and a11 the Iimbs of the

second feature of

Lsp-or this and tl,c following, see the Traitae p'zo/aw?, pliade, pp. 812-.AT xl pp. i27-131, 165-171t.

8ls, 841-846and ,8.5+-86:$; corresponding to , ,Zilsl llutJllllldlPllftjllfe'alnqtetsjj ionyy p, aarjyeanrttjjetysessoijny ojmusX,

ttetwf vronxl njoW On ref e r,ylf,

, . . ,Z

body. ltself sllaped like a flanae, thc glaTld llarbtltlrs and dispatclles thetinier flames of the spirits in pefpetual pentecost. Tle pores of tle braininto which the ejaculate spirits flow are like intervals among tile threadsof a tapestry. The spirits tunlbie into tlacln, talways looking back at' ()rtfacing' regardans) thc gland. Strange that thcy can <l()ok'

; curious thatthe gland whose gaze follows thena needs either the spirits or thecerebral tapestry. Nevcrtheless, these intervals ()r brcachcs in the tapcs-try are cxtrtmely inportant for Dcscartes' aceount of pcrception andmemory. Let us imitate the aninaal spirits, lltlwcvcr, and Io()k solely tothe gland.Corresponding to its tlifferelttiating fullction, tle pincal gland inDescartes' physiological systeln possesscts a differentiated structure. ltis composedof lvery soft material', Tllaterial tllat is ntlt embedded firmlyin the substancc of the brain but attachctl t() it by dclicate, pliablearteries. The foree of tle blotld that is prtlpclled tllrough tlese arteriesholds the gland in approxinlatc equilibriullt, like a flamc dancillg on itscandlewick. The elastic arterics allow tlle

g. Iand t() spill tllc spirits in theparticular direction they arc to pursue towards tllis ()r tlaat l-egion of thebrain. $V'e might ask what actually causes the glalld to tip in diffcrentdirections. Descartes cites two causcs in addition t() the altogethermysterious and here uncxplailzed and undiscussed infltlttnce of therational soul. The second is an exterior, tltluglln()t extrinsic, cause; towit, the aetion of objccts imprintcd ()!1 tlle senses. 'lalle first is anintrinsic cause, that is, one that operates cntirely witllin the circuitry ofblood and brain, tube and porfz

; laluely, the difference' in forceexerted by the sundry partics of anilnal spirits as tlaey burst from thegland. The animal spirits, Descartes cmpllasizes, are 'alltlost alwaysdifferent in some respect' (854-855/180) , Diflkrence and I am tcmp-ted to write the word as dlf'fl-aklce, with a pinttal a, as it weredominates the systen. Dominatcs it dynalnically (in the ilydraulicstanding or leaning of thc gland) , topographically (in tllc gland'sslightly off-centre position, as well as in tlle intervals alatlllg tl'e threadsin the tapistry) and energetically (in thc gradients of force possessed bythe enlitted animal spirits) .And yet, at the end of the day, tlle cxtttrior (lbjccts ()f seltse perccptionwin the upper hand in Descartes' accotlnt, ftlr tparadtlxicallyl inherentreasons. W'hat 'ordinarily' causes tlc gland t( lllfls't! is 'thc ftlrce of thobject itself' exerted on a sensc (lrgan. 'l'iltt scllsc tlrgall iI1 ttlrll acts (,1)the apcrtures of the appropriatc tubes leadillg t() tlltt brtin . I f tllese ttubes naay be colzpared to the :0?-//-g.,t>7?/ ()f clltlrcll (lrgal'ts , vvriteslleacartes, then sensible objeets in tlle ttxterrlal Nvf )1-! tl are tlike tlteorganist's f ingers' (84 1 / 1 65) . ''l''l'e 1 ittltt 1':1:11) ()11 t itc i Idsitle, tlle l1()11tln-culus who nornaally serves as tlle elnlltl(.l illlrllt ()f t 11 e i !)) ltll llellt rat i()1'1a1princi pl e , i s ntlvv cat a pl , ltc ()1 ()t l t si (.1 e t 1) t! 1)( )t1 y- :1

.1

) f. I t 1) (? 1).1

i l'l t 1 i

'

1 t t'' '1 1,, o

world wherc we may serve as an example-a privilegcdexample for both sense perceptfon and memory. objects strike t/7-c:-pent) the eye. More specifically, rays of light press against selectedpoints of the eyeball; they then trace at the rear of the eye a figure that.correspondsto the figure of the object' sundry threads of optic nervetissue transmit this figure to the brain tubes upon which they open, andare thus Kalso able to trace the figure in the interior surface of the brain'.At this juncture the animal spirits sally forth from those points of thegland that are inelined toward the tubes in question, that is to say, thepoints that Cface' or <look at' the tubes towards which the gland is nowleaning. Precisely when or how, by whom or by what, the gland isinelined remains unclear: at times Descartes describes the gland asinclining in a particular direction in order to cast the animal spirits inthe proper direction (854/179) ; at other times he descrfbes the spirits'egress from the gland as a gratuitous Sheading towards' the requfsitetubes, this spontaneous departure attracting, the gland fn such a waythat the animal spirits draw it along in their jetstream (863/188) .Whatever the case, sense perception remains multiple typpgraphy (thevarious impressions, traces, coinages) and iczqqgyg-phy (tlae retracijagof the identical figure, the con of the objeet) . In tge wake of senseperception, memory too is a typographic and iconographic system.Descartes encourages us in the Treauke on xvtzv tjus (8yz/lyy-jyy;:

1- $T--

1Ve. 1S1On

Think of it in the following way. After the spirits emerge from glandH (Figure 29), having received there the impression of some idea,they pass thence by tle tubes 2, 4, 6, and tubes similar to then, intothe pores or intervals amongthe tiny threads that compose this part/.?of the brain. The spirits have the power to enlarge these intrvalssomewhat and to bend and variously deploy the tiny threads theyencounter on their paths, according to the diverse ways they lnoveand the diverse apertures of the tubes along which they pass. Theresult is that the animal spirits trace there too the figures tllatcorrespond to those of the objeets. They do not always do so here aseasily or as perfectly at the first stroke as they do on the gland H, butlittle by little they yet better and better, as long as their action isrobust and long-lastlng or is reiterated several times. This preventsthese figures from being readily erased, and conservestlcm there insuch a way that by virtue of them the ideas that were formerly on thegland are able to take shape there once again long afterwards, withoutrequiring the presence of the corresponding objects. And in thismemoty consists.

Not only the sense organs, the tubes and the gland receive impres-sions, but so also do the animal spirits themselves. W'hether they arestamped passively or somehow actively see and sean the figure on the

glald, to whicll they are always ltltlkillg baclt, as 1 f awaitillg a sign ;whether, in otler words, tlle altill-lal sjlirits are 1))()r(? spectating spiritthan branded animal ; svlletller tlle spirits ll(tetl tllc gland at al1 iIt orderto see or to be inapressed, ilaslnucl'l as tlley tllelnselves llave trans-ported the figures there

; whether tie glantl lleeds //?t????, since it clearlyhas possession of the iltpressed figurcs; these arc a11 ll-resting ques-tions. rrhe spirits' power to enlarge tle intervals and to wcave thethreads into a picturesque tapestry is hartlly surprisillg; wlat seenasodd is that they should requilv threads to svllrlt (ll, and tlat theirweaving and tracing slould not always succeed at tle first strolte. Sineethey havc already transluitted the figure fron the seltse orgall to tlegland they are surely capable ()f remelnbel-ing it well entlugh witlilutthe warp and uzoof of the threads, or at least well enougll t() wcave thel'nexpertly. (Capable of b-etnenlbenblg it ? 'Vllat lm l saying?

) ln any case,the animal spiritj'shotlld prefer the gland as tlleir lncdi uln and stickwith it, as it were. For the ilnages are casier t() apply tllcrc and l'noreperfect in the execution. Jvhy the spirits shtluld peregrinatc to region 1)(not ho'l.e they do so, since clearly they relylcnabcr tllc wayl , and whythey should toil away at their own artistic education tllese things tooremain enigmatic. 'Fhat the gland's future recollections dcpend ()n theimages woven by animal spirits in tlc Ghobelill of lzlelnory is 1ndisput-able. Yet why the anilnal spirits shotlld have t() dcpend ()n tle apparatusat all, and why tle gland should have to rely- t):1 the journcymanWCaVGS WC Cannot ascertal' n .

Descartes therefore illustrates. 'vitll an ilnage . N()t t() be ftlrgotten.He writes (853/ 178) that tle allinzal spi rits llave the power to forn)certain passages' in the brain tissuc wlliell rttluail (lpen' aftttr sensationhas ceased. E vel if these passages sllllultl cltlse tltty lttavc ta certaindispositiol' in the slendcr tllrcads of tlle braiIl 13y Nvlliell tl'ie routc cal bctraced and reopened '. Descartes appeals t() tlle illage ()f a ptlntrl) and thcaction of puncture or perforation

( lzigure 30) , a particularly vitllent butstrikingly efficielt forln of'

typography . I2-vell tftcr the I'tlncl isrenoved, the tiny holcs in the stretclled canvas druluheatl perdtlre

; or,if they should seal up again, thc canvas still bears stignlas of the holesand a tdisposition' to reopen then. rlMhereis stllzetlling odd about tlisirfage, both its canvas and its pulcll. Canvas is ntlrlually uscd forpainted portraits, such as F ral'lz I Ials's lilellfass ()1- tllc l'taugllty philo-

sopher. 'Yet here a punctuatcd pattcrn allpears, l1()t cxactly a paint-by-numbers canvas that guarantecs

81 stanllardizetl and infinitelyreiterable ilzaage, but a sort ()1' cllild's sttvvillg carl. ()r tlt) tlle lltllesindicate tllat tlis model for lnelllory is a ltilld (?f sitlve, t() be uscd , asSocrates would say, for lnilkil'lg bil ly-gtlats ?

Rather than continue vvitl) I-lesctrtes' acctllllt ()1' t I)e Ill'lltral glalttl 111

sensation and lnelntlry. 1ct j'ne sulllfl'arizc witll tlle l'tllltlvvillg tlll-eepoints :

.w.w.w v xu . Rx A taa x.A cAA Paradoxes of the Pineal

clear that the gland, the animal spirits and every other item ofthe apparatus is subject to the logic of supplementarity: al1 are essentialto and yet utterly superfluous for Descartes' account.

2. That aceount presupposes everywhere what it most needs toexplain, namely, why it should be necessary to call upon either a soul ora machine to read representations engraved ol a gland : the aecountmerely postpones a1l the essential problems, pushing tlem as Sehell-ing said in another context one step farther down the line'.

3. Descartes' protracted fiction is itself a mimetic effect of memory,rather tlan an explanation of it, and that effeci is unlimited ; it is notmerely memory function and its various machine parts that prove to besuperfluous but the soul l'J.t?J the soul as such', Neitller the petiter/t7??#c nor the animal spirits nor the invisible soul knows what it isdoing: the gland teeters and tips (miraculously) in the right direction,even though neither it nor the soul knows what is to be rememberd

; the .frantic tumblings of the animal spirits in the grand flea circus of themind cause an image to form on the gland, the same gland that has onlynow spilled them; and the soul, the little man, dragged back in torender an aecount of himself, scans the illegible and illiterate gland andpronounces upon what neither of them will ever know. ln so far as thesoul needs the animal spirits those ultimate oxymorons and in so far

as it needs the gland, it is just another piece of superfluous machinery.Lifeless. Death itself .

1 lt 1 s

Georges Bataille does not attribute his fixation on the pineal eye toDescartes' fictional physiology and philosophy. Seldom lnentioningthe name of his predecessor, Bataille freely admits that during the years1927 to 1930 it obsessed him, first as a traumatic representation whoseaffective eharge could not be abreacted, and then as the deliberatelychosel eentral figure of a mythological anthropology. Yet anotherfiction. The power of that fiction may be felt in such texts as <'T'he SolarAnus' (1927) , The S1/ry of le Eye ( 1928), (The ysuve'

( 1930) and'T'he Pineal Eye' circa 1930) . I shall leave the first two texts to yourprivate delectation, and comment here only on some portions of drrhe

ysuve' and t'T'he Pineal Eye'.5Bataille remains unabashed by the notion of an anthropology that

uses science against science and that surrenders at various points in itscomplex textual economy to a series of images'. Images of what? Of6 See Georges Bataille, Visions of Excess.. Selected l'llrf/l'zws, 192 3-1939,Allan Stoeki (ed.) (lanchester University Press, 1985), 74-90. In Bataile's

Oeuvres coplle-, presented by Michel Foucault, 10 vols (Paris : Gallimard,1970 ff.), see 1l, 13-35. In my text I will cite the French pagination, then thcEnglish : See also the selections published in October 36 (Cambridge,Alassatrltusetts: SIIT Press, Sprillg 1986).

nothing less tlan the origins of tle lluluan species. i Iowttver unjustifiedsucl surrender to images may seen, argtles Bataille (22/80) ,

the introductiol of a lawless intellectual seritts intt) tlle world ()flegitimate thought defites itself at the outset as tlle llost ardutlus andaudacious operation. And it is cvideIlt tllat if l't werr I14)t practisedwithout equivocation, with a resolutitlll alltl :1 rigtlur rarly attaillcdin other cases, it wotlld be tlle l'nost vaill tlp(2ratttlll .

Images of the greatest intensity, an intcllsity nleasured against tllerevulsion tle images arouse. And yet illtroduced by an explicit appealto philosophy of both tlle epistenaological ttrigour'l and lntlrul (srestlltt-

tion' twithout equivocation') kinds. Bataille is (lbsessed witll t1' nlpera-1tive prescriptions' (after tle nanner of It:tl'1tl , developttd il) ntltllingless than $a clear and distinct 'way' (in tlle 'wake ()f llescartes and llis

- ninlaux ) .e% .#7

Bataille's images have relatively stablc valellces, and ftlrlll relativelystable molecules, hosvevercaustic their actiol) lllay seeln. ? Iltltt) coll-temporary svith f'-rlac Pincal E ye' (260) expresses tlleir colleetive aina :

the images are to arouse in oneself a sense oftwlat nliserably miscarried

at the beginning of the constitution of tlltt hul-lall botly'. '-lqllat sucllmiscarriage is the proper name for tlle birtll of llunlallkind Bataillc doesnot doubt. ls unablc to doubt. F or all the force 01.*,

tlle cogito ald dubois gathered in this distended pineal eye. Likc Sandor Ik-crttnczi's lssay't),7 a T/ct?r.p ofGenitality ( 1924) , with its pervasive catastrllplaisln andits dthalassal regressive tendency',; Bataille's l'nytlloltlgical antlll-opo-logy is an account of phylogenetic tragttdy, prceariotls survival,anguished adaptation, freakisl'l pcrnnutttitlll alltl igllolninious self-recognition. lts guiding inage : an unpaired ttyc at tlle stlnamit of theskull, the eye and its pedtlnclc ttrcct witll l)l()()d frolll tlle llcart andramming the bone, groping for tlle apcrtur: tllat was ()l)cc tllere,erupting then like a volcano and exposing itself to a sun tllat will blild itutterly. That pressure on the skull and tlle ertlption Bataille kllows itfull well are eninently anal, and the eye's allolnalous urge t() cxposcitself to the blue of noon purely autotlcstrtlcti ve . Antl yet tlley folltlw a

certain logic, perhaps the only logic tllcrc ttver was, ascensiollal al'ldarchitectonic. 'lahe pineal eye does Itlt illvcl'lt tllat ltlgic, but suffcrs it.

I have already mentioned Aquillas' article ()11 tlte suitablc disptlsitionof the human body. Tle bulk of tllat articlc llas t() dt) u'itl'1 tlle ttrcctposture of humanltind, tlle vertical axis k1ltlllg wlliell tlle spcciesdevelops and in Nvllich it invests all its l'ltlpes . l I tinlalls apparelltly sl-lartt

? Sllzdor 12 crenczi , u%t-ll l-l.f' t(?ll a2/?' /3.'J't'/?4?/???r?/h'.t', 2 $-() Is , ( Ira 11 k f u rt :,111

llain -.F*.1

stl 1) f..?r , 1 9 7 2 ) , l I , 3 1 7 4()4 ) . I.*i2

! 1 g 1 1 s 1 '1 t rl T1s 1:.1

t 1 ( , T'1, '/ h /,.? ff ?../'? .- .,l l '/?trzf.?

l ), (t('

('7c>??-/?/?'/ l '1 ) .'s' l 1

' : r''k

'''. l

.- 1. ! l

1.4, l : ) 1k t ! ( >: t ' '- -.

'.i : i t : -'x t ? I l ( . i i , '-

( k , )..

)

UaVIG 2' arre'; Arell

that axis with plants, while animals move on the lorizontal. Yet onlyapparently. The doctrine to be defended is Ecclesiastes 7:30, Deusfecithominem rectum. (It is rectal, erectile man that obsesses Bataille andothers both before and after him one thinks of Lacan's 'Kant avecSade' and its trectification of the position of ethics'.8) AnticipatingFreud's famous notes at the beginning and end of chapter four ofCivilization and 1ts Discontentsa% Aquinas recounts the necessaryregression of man's olfactory sense before the upsurgent, gropingintellect. The very face of man is itself erect, and like Descartes' mobilepineal it is able to turn freely, in order to scan the things both of heavenand of earth'. The brain is not oppressed under folds of flesh but is

superomnespartes cozlpo?- elevatum. Thomas conjures the nightmarevision of a prone humanity, sacrificing its hands to the earth as fore-paws, seizing food with its jaws which now jut forward, stretching tleentire skull into a sickening oblong shape; in unstoppable devolutionthe lips and tongue toughen and grow hard, their mucous tissue nowleathery and gross, lest these organs wound themselves on the jaggedearth on which they scavenge. And howwould this horned tongue wrapitself about speech, (which is the proper work of reason'? No. Thomasknows, as after him Freud and Bataille will know it, that the humantrajectory is upward. When therefore Bataille dreams excessively tof

leaving, in one way or another, the limits of our luman experience'(15/74), those dreams are continuous with the dreams of a11

metaphysics and morals, resisting the same nightmare. Bataille, trainedas a medievalist, would not object to the following extended quotationfrom the conclusion to article 3 of question 91, which begins with an

astonishing paradox:And in so far as man has erect posture he is most remote from plants.For man has what is superior in him namely, his head turnedtowards what is superior in the world; and what is inferior in him is

turned to the inferior part of the world. Thus matters are optimallydisposed with a view to the whole. By way of contrast, plants turnwhat is suprior in them to the nether world (for their roots are

analogous to the mouth) ; and what is inferior they turn to the upperworld. And the brute animals assume the middle position: for tllesuperior part of animals is the part that takes in nourisllment,whereas the lower part is that qua czaff/ supetjluum.8 See Jacques Lacan, ltant avec Sade', in /c/7'l: (Paris; du Seuil, 1966),

765. See also p. 779, toeuvre ennuyeuse . . .'.9 Sigmund Freud, Das Unbehagen in der Kultur ( 1930), in tle Freud

Studienausgabe, 12 vols (Frankfurt am Main; Fischer, 1982), IX, 229-230and 235-236. See also 1etters.55 and 75 to Fliess, in Freud, Aus den

a'ftn/hngc?l

der Psychoanalyse, Ernst Kris, (ed.) (New York: Imago, 1950), 198-199,2 4 6-218.

/vith the angelic doctor's ilnage firnaly in place, tlle illage of tlc tree

obscenely turning its netller parts to tlle slty, it will perlaps not be

excessive to remarl that the paradoxes ()f tlle pincal even when the

gland and eye rezain unmentioned extend far baek in our history,from Hegel's plilosophy of nature as developttd in tlle lllyclopedland in the 1805-06 lectures at Jena ()n lealphilosopllic, back lhroughKant's Anthropology Jzo/z? a Fz't't.jw/t'7/?'c Point (?.J Vc'?.c and Descartes'

Treatise on 2Jz1?r/, to Thomas, Thomas' Aristotle, Aristotle's Plato, and

Plato's Timaeus. For it is the doctrine ()frlaimaeus of Locri, the

Pythagorean doctrine as recorded il Plato's l'inlaelts, that we recall

wlen Bataille designatcs Stle sumnit ()f the llead' as tlle focal goint of

tle new equilibrium'. Correspondilg to tllis focal point s tllc dinainu-tion of everything in the bonc structure tllat igoes against the vcrticalimpulse of the human being', such tlilninution llecessitating above a11

else ! the reduction of the projection of the anal orifice' ( 18/76) . 'lahe

energies of evolution (or of devolutitln, sillce tllese arc ulldttcidablttwhere birth is miscarriage) tend rather ttlwards the buceal (lrifice,towards the lypertrophy of the larynx, brain and eyes. lncuding,presumably, the pincal eye. M' ''lzicl'l is for l'ltlnr we call see it, elearlyand dlstinctly the ultinlate paradox : if ftlr Descartes tlltt diluinutionand volatility of the gland testify to tl'e distallcc betweel llulnanity and

bestiality, then that blind vcstigial eytt, that stlrtlid gland exuding tctrsand worse than tears, has erected itself as a lnolltllllent or l'llenlorial to

the absurdly frustrated ascent of Ilal. Bataille alltlws llis falltasy t() fecdon Cdischarges of energy at thc top ()f tlltl Iluad', cllnfessing in a1

autabiographical vein reminisccnt t)f llescartes' lnl--t-oltl'-%e and 51'?tlila-lg't')/?- the following ( 19/77) '.

. . this eye that l wanted to havc tt tlltt ttl)7 ()f Illy skull (since I had

read that its enbryo existed, like thtt seed ()f a trtte, in the interior of

the skull) did not appear to ne as allytlling other tllal) a sexual organof unheard-of selsitivity, whicll would llav: vibrated , causing nle to

emit atrocious sereams, tlle screalzls of a luagltificelt bttt stinkilge'aculation.

J

You have seen and perhaps cven hcarl tllllse scrcarns in tl'c paintingsof 12 rancis Bacon, who read Bataille as t/lalttbranclle rcad llcsc:lrtes

;

lt'

and you have felt tlat ejaculation, Descartes llilllsclfwould illsist , everytime you have ever succeeded in rttrnttnabttring stllnething or had what

the Germans call an %l/?t'z-A'?-/t-?/J???'. '.

10 I aln thinking of a 'vvllole sttries ()f pllrtraits f 1'()111 tllc llitl- 1 94()s t() t l1c llli(1-

195(Js, e-g. il-lead l '( 1948) ,

t l'Ieatl I l'

( 1 949) , dstlldy ftlr l'tlrtrait' ( l 949 ) ,lshtlj7e

I 1' ( 195 1 ) and tchirfpanzee'( 1955) . Scc a1s() tl'tc appall.'sis lly l l;1yvll -/tles, veb

of Irnages' , in Ih-atlcis p.tq?t-fkp? ( t.z()Tltl('ll'l -.' INlle 61

'ate ( ; :1 l Iery . 1 t)85) , esp . pp .

1 2- 1 .F; .

Many paradoxes of the pineal eye remain to be explored. Yet l amshort of time, and you perhaps of patience. No doubt I have allowed a

sheer contingency to guide my reflections the fact tlat two TFrench

philosophers' take up the pineal, the first as seat of the soul', the secondasthe symbol of the human malaise. You might well demand somethingmore an intrinsic connection, an historical thread, a necessity, a

deduction more than these paradoxes. All 1 can do is raise the ques-tion that seems to emerge in both cases: Why, where it is apparently tlemost hard-nosed of matters, namely, the rather shocking interventionof a coarse materialism into the discourse of rational psychology, whythe upsurgence in both cases of h'ction? Even if we feel confident thatthe fictions are quite different, that the circumstances in which theyarise are quite diverse, are we satisfied that the paradox of hard scienceand soft fiction dissolves? Rather than insist on the question, however,I prefer to hand over the reins to Bataille. Who is, 1 know, limself themost wanton of steeds.ll

Allow me to invoke a series of problems and paradoxes arising fromthe extraordinary text, drrhe Pineal Eye', invoke them with very littlecommentary. Bataille distinguishes between the horizontal axis of every-day vision, which ifetters' the human being Ctightly to vulgar things',and the pineal eye, which breaks through to 'a sky as beautiful as death'(26/83) . lt is as though Bataille were reiteratlng Heidegger's basiccomplaint: man led by beings, has no eye for Being. (1 mention

11 I am grateful to A. Phillips Griffiths for provoking these thoughts on the

lnits of my undertakinghere. Nor can l do justice to his suggestiol that I takeup the question of soul and body in Kant's paralogisms of jure reason (KrV, B

399ff.), especially the second paralogism, coneernilg the slmplicity and incor-ruptibility of the soul a simplicity and incorruptibility that are surelyreminiscent of tbepeteqrlande in Descartes' system. Kant calls the doctrine of

incorruptibility fthe Achllles of all dialectical deductions' (A 351), ithe cardinalprinciple of the doctrine of the rational soul' (A 356) and the tmainstay' (A 361 :Hauptsttze) of rational psycholoor. Yet this central pillar is fissured, thccardinal or hinge is jammed, and Achilles has his heel. l shall refrain fronlcomment on either the highly reduced and dlogicized' version in B, or the moreexpansive discussion in A, both of them much discussed in the literaturc, alldshall merely pose two questions concerning Kant's introductory remarks to theparalogisms, remarks common to both A and B. First, if the dI think' is tlle solc

text', der tzffczge Fexf (B 401) , of rational psychology, do not body Klpeand matter iklaten'e) come to intervene in The Cn'tique ofpure ftz-t)?; as a

kind of fiction a radically undecipherable text? Second, is it because matter istno thing-in-itself but only a representation in us' (A 360) that Kant envisagesthe monstrous possibility of an empirical psychology that would be $a kind of

physiology of the inner sense' (B 405)? Perhaps the text of rational psychologybegins to suffer change already in Descartes' fiction? Perhaps what Bataille is

attempting can be 'described as a physiology of the inner scnsc?

Heidegger because,which that tlinker offered lis one antl ()1-11y lecturc eourse illvolvingtheoretical biology. It is also the year when Alfrcd Ntlrth SYllitehead

was putting the finishing touches on Procttss tyz/l letlly'. N() pinealgland or pineal eye graces either accotlllt. Yet tlltt central problemdiscussed in Heidegger's lectures, namely, the iabyss of esscncc' tlat

arates human bein' gs from aninals but also sets tle two in relation tosepone another by virtue of the body, lzas mucll to do witll vision and thus

bears some relation to Bataille-lz) Yet why an eye for llcing'? Shouldnot Bataille rather desire to have an eye out, as it were, for lleillg'? As

though the acolyte of tBeing' llas ole eye too maTly perltaps? And whytlis complaint about the Ilorizontal axis ()f vision, wlicl) 'fetters' us to

the mundane? For is it not the pineal cye itself tllat embodics the

ultimate vulgarity? 'lale pineal eye, and ltlt tllc llighly diffcrentiatedeyes scanling the horizon, that expresses 'a lniscry al1 tle nlore oppres-sive in that it is apparently conftlsed witll serellity' (27/83) ? I2()r tlepineal gland, which remains in a virtual statc' in tltt braill, can 'attain

its meaning only - . witla the help ()f naytllical ctlnftlsion', the confu-sion tlat condemns nature and Ilature's hunAallkintl to a spttcial exis-

tence'. Such confusion, we have said, originates at least as far baek as

rrimaeus, for whom the universe of astronollly' is mal's 'higlestachievenAent',soll fc/p?c (32/87) ;

it is surely co-extensive witll wllatNietzsclze identifies as thc lzistory of nihilislll. rl'llus tlle 'vertigo-trce'envisagedby Bataille (27/84) would l)e the Ptlrpllyriall tree, tlle tree ofmetaphysics as portrayed by Dcscartes iI1 a letter to Picot ;13 and the

pineal eye is the triangulatetl eye of Providence, witl tle triangle

merely inverted and tlle eyc, enucleatcd, ()I11y nztlre wretcllcd :

as coincidencc would llavc it , 1930 is tlze year in

'rhus the pineal eye, detaching itsttlf frtlln tlle lltlrizllntalsystem ofnormal ocular vision, appears in a lll'lld of llilnbus ()f tears, like tlle

eye of a tree, or rather like a hulnall tree. At the saldte tilllc, tllis oculartree is only a giant t1'gntlblcl pillk penis, drunlt witl) tlle sun and

suggesting or solicl-ting a malaise : nausea, thtt siclclliltg tiespair ofvertigo . ln this transf iguratltlll ()f llattlre , during vvllicll visitln itself ,

attraeted by natlsea , is ttlrn tltlt and ttlrll allart by tlltt stlnbursts intowhich it startts, tlle ertretitlll ceascs t() be a pai 11f tll u Illleaval ()11 tllc

12 A/lore prccisely, it is tlle secolld llalf ()f I Ittideggttr's lt)29--3() lttcturc ctlurse,

'The la-undalnental Concepts ()f s'Ictapllysics : y'Vtlrlt1 121!11 tude Solitude'

that is relcvant llcrc. See vol tl nae 29/3() f lf t l1c 'lalllbl a//tra/'trdzl,(z.,f.zt,?' f,'o-t7p?/-

ausgabe (F rallkf urt anl Nlai T1 : V . l ltlsttrltlal'l 11,

1 983 ) , 27 3 f f . Sett a1s() tlle

remarks on tlis course by Jacqutts llerrida ant! 1) . l'- . Iol'tlll i ltlleading

Heidegger' , l?esearch 11?/-'/?J??(????t???(?/f?Jr', XVII, 1 987 , passijll . '

. 43- l-lcidcggcr ci tcs the 1 cttcr ( i 1)

-.'1a

I %. 1 1) 1 n llis 1. l-tutr???t'??'/?t>??

(Izral-lltf tlrt

.!'#' .

arn 1.1 73i 11 :'!.- . I'Q l ( lster r''k'l tl 11 : 1 , l 9() 7 ) , 1 9 5 .

surface of the earth and, in a vomiting of fI? lrless blood, ittransforms itself intq a vertiginous fall in celest-ul space, accom-panied by a horrifying cry (27/84).

These image: of a mtilation exceeding castration, irreducible to theOedipal triangle, are very much continuous with images that are centralto German ldealism, especially to Hamann and Schelling.l4 They bringus to our most ingenuous formulation of the pineal paradox: Could it be

that the mythical confusion' of the vertical axis itself is the source of al1

the pejoration and misery lavished here the tears, ignominy, malaise,vertigo, nausea, the bloodletting and the fall so that a more gentlereturn to the vestigial organ in dreamless sleep, superfluous but with-out ambitions, locked forever beneath the skull and pursuing itsmodest, altruistic endocrine function, would be something like theearthly salvation of the species?

Perhaps that vertiginous fall and more gentle return is what thathorrific section of 'The Pineal Eye' which Bataille calls t'l'he Sacrifice ofthe Gibbon' is really al1 about. lt is not the ape alone that is inverted andthat hideously erupts but as though it were Kafka's urbane ape that is

spinning the entire tale, as though it were precisely 'A Report for an

Academy' (1919) not the ape alone but also that spectral creaturepossessed of the pineal eye, possessed by it, obsessed with the essentialmark of human devolution. If Bataille greets the eye with tthe unin-telligible discharge of a burst of laughter' (32/87) , sueh laughter is

hardly triumphant, and not even malicious. The final lines of Bataille'smythological anthropology read as follows:

. . . surrounded by a halo of death, a creature who is too pale and toolarge stands up, a creature who, under a sick sun, is nothing otherthan the celestial eye it lacks (35/90) .If the superfluous pineal apparatus of Descartes' Treatise ofvan in

fact makes the rational soul superfluous, the pineal eye threatens toreduce the species man to hzuingsbsuperjluum. And yet during the pastthree hundred years Descartes' fiction has become the remarkablytenacious physiological science of our schools of medicine and villagesurgeries. Should we not, then, ladies and gentlemen of the academy,ape the history of modernity? Should we not agree here and now toreturn three hundred years hence, in order perhaps to find the obses-sions of Georges Bataille obsessions that evoke in us nothing so muchas a burst of derisive laughter to find those obsessions thoroughlypervading what by then we will no longer laavc the temerity t() call thesciences of man?

14 I am thinking of Schelling-and Schelling's use of l-lamann-in tletreatise On the Essence of Human Freedom (1809) . See D. F. Krell, 'T'heCrisis of Reason in the Nineteenth Century', il Collegium #/?c?c?o-

menologicum: The First Ten yptzr., Giuseppina Moneta, John Sallis andJacques Taminiaux (eds) (forthcoming in 1989).

228

Notes en UonlrlDulorsi

Pascal Engel is sltre '/: Co'frellces Jc l'hilosophie at the llniversit desxsclr?ce. Sociales, Grenoble . l It! publislled ltlentit et ?-tl./?r?lct? (Presses de

l'Ecole Normale Sup. rieure, Paris) in 1 98.5 , and lis l''lll'lllstlpll? Jl Ia Dzf/zdc(Fayard, Paris) is forthcoluillg.

J . J . Lccerclc is Professor at tl'te Ullivcrsity of Nalltcrre. l lis lllilosopythrougl the f-tmifzzz Cilass (1 lutcllinson) was publisllfcd in l 985, and llisFirankenstein: 'nythe et p/??'/o.(?>/?? ( Presscs Universitaires dc I'rancc, Paris) is

forthcoming.

lklichlc Le Doeu f f is at the (.'c?? /?'c h''a /?'t???f7/ (1e !/'J lttt.'llt,t't'lle u$'cl't?/?/?. lue in

Paris. An English translatioll of llcr 1- )??t7.(#??t7?'?'t? l'glilosoplique (ttl itionsPayot, Paris, 1980) is about to be publislled by tlltt Athltlne lrcss.

Nlichel Dcguy has publislled mally volulnes ()f p()(2111s and tlther wtlrlk's sincc

1959 . His Donnant f?f.)/2/2tr?/?/' (1t?8

l ) was publislled iI1 Ellglisl) 111 1984 Llj'l'vl'ngGz'zg-g, U C Press) . l I is latest bo() k i s 1-a y?f'?tol'c ,1 't?. t >t7. .$-t??? lc ( d itio n s d u

Scuil, Paris, 1987) .

'Vincent Carraud is at the U nivcrsity ()f Paris X l I - I Ie is Sat'?-.llt'z/'pzi of theBulletlCzrlt//k/l/pt? (l-t-hives t/t, 1''lt'l()s()phl'e) .

Bruno Latour is Professor at the ltkole Jc. tj'll'll(vs, laris. l Iis 'works includeLaboratoly Llf'e (Princeton , 1986) , tSc?'c/?t't? ?'?? z'jt-tlll ( l I arvard , 1987) an d '/>cPasteunation of ./-/ raltce ( I l arvard , 1 988) .

Paul Ricoeur is Professor EIucritus of tlle Ullivttrsity of l'aris X , I'Iis luanyworks include bkeud tzz/,/ Ihilosoplly (Arale U I) , 'lhe (.'()lljli(?t (tf /7?/t??../..)rt?/tz-

tions (Northwcstern U I) , 'lhe /??/&? ()j' A.&?/t?>/?f??-('l>t)r()nt()

U' I) l-inle t'JSJ

hal-rative (3 vols. : Ch icago U P) alld llelnlelleltlsff/l/ tllc .f//?/?t.z?! s.st:?llt-es

(CambridgeUP).

Richard Ilcarney, Llniversity l-ecturer i!) Plliltlsophy at University Collegt,Ilublin , is thc author ()f naany Nvorks ()11 I risl) ctllturc altd Iurtdj'lean I)I1ilos()-

hy , incl udi l1g llialoglles t,?'J/? ( 'olltenlpolvl' ( b??/J'??fa/?1(11 -1yl/'/?/ttap'-

( l 98,1) ,Pszlotlttl-t ljzl t'?'pt>???t,??/.$'

?'??lljltmtlllet.lll 0'/??'//o/)/? J.' ( 1 98t')) ( 1)t ytl Nl :1 l 1cl lt-stu-r I.J 1' )

alld 7 ht.! l'lz'rtzlt.? f?/- lnlan'llatio'l ( l I u tcllillst ,1 1,

1 t?88) .

l-7 li e (,'''' eorgcs )' () uj ai 1) 1 s 2 ss 1 sta I1t1)1-4

) f tksst) 1-( lf I'

11 1 1 ( )s( ) l. 11 y a t (.'N- :1 rl t.- t ( ) 11(>

() 1 1 egc ,1$11 nnesota.

David Farrell Krell

surface of the earth and, in a vomiting of flavourless blood, ittransforms itself into a vertiginous fall in celestial space, accom-panied by a horrifying cry (27/84).

These imags of a mutilation exceeding castration, irreducible to theOedipal triangle, are very much continuous with images that are centralto German Idealism, especially to Hamann and Schelling.l4 They bringus to our most ingenuous formulation of the pineal paradox: Could it bethat the tmythical confusion' of the vertical ax itself is the source of allthe pejoration and misery lavished here-the tears, ignominy, malaise,vertigo, nausea, the bloodletting and the fall so that a more gentlereturn to the vestigial organ in dreamless sleep, superfluous but with-out ambitions, locked forever beneath the skull and pursuing itsmodest, altruistic endocrine function, would be something like theearthly salvation of the species?

Perhaps that vertiginous fall and more gentle return is what thathorrific section of d'rhe Pineal Eye' which Bataille calls t'T'he Sacrifice ofthe Gibbon' is really a11 about. It is not the ape alone that is inverted andthat hideously erupts but as though it were Kafka's urbane ape that is

spinning the entire tale, as though it were preeisely (A Report for anAcademy' (1919) not the ape alone but also that spectral creaturepossessed of the pineal eye, possessed by it, obsessed with the essentialmark of human devolution. If Bataille greets the eye with the unin-telligible discharge of a burst of laughter' (32/87) , such laughter is

hardly triumphant, and not even malicious. The final lines of Bataille'smythological anthropology read as follows :

. . . surrounded by a halo of death, a creature who is too pale and toolarge stands up, a creature who, under a sick sun, is nothing otherthan the celestial eye it lacks (35/90) .lf the superfluous pineal apparatus of Descartes' Treate ofMan in

fact makes the rational soul superfluous, the pineal eye threatens toreduce the species man to hjuings'supetfluum.And yet during the pastthree hundred years Descartes' fiction has become the remarkablytenacious physiological science of our schools of medicine and villagesurgeries. Should we not, then, ladies and gentlemen of the academy,ape the history of modcrnity? Slould we not agree here and now toreturn three hundred years hence, in order perhaps to find the obses-sions of Georges Bataille obsessions that evoke in us nothing so muchas a burst of derisive laughter to find those obsessions thoroughlypervading what by then we will no longer have the temerity to call thescicnces of man?

14 I am thinking of Schelling-and Schelling's use of Hamann-in thetreatise On the Essence of Human Freedom ( 1809) . See D . F. Krell, d'l'heCrisis of Reason in the Nineteenth Century', in Collegium P/7ue'z/o-menologicum: The Fr-r Ten Fetzr', Giuseppina Moncta. John Sallis andllltacl I I fxq ''Vn na i n i n 1 lv ffxcl qh ( fart l

(.1 i I I i i lAc#' ln i tk;< i'

Notes on Contributors

Pascal Engcl is slt pr de (,b?!#J, l'ellces t', Pllilosoph? at thc lhl'ersit Jt?.';

Sclnces Sociales, Grenoble. l lc publislled ltlelllit(.; c/ 7ry/p'g/?ct? (Presses del'Ecole Norrnale Suprieure , Paris) in 1 985 , alltl llis l%l'l()-b'opllie tta Ia /r?.4?/?/?(Fayard, Paris) is forthcomilv.

J . J . Lecercle is Professor at tlle Univcrsity of Nanterre. l lis Philosopllythrough the f-ot?/7g-kr Glass (l-lutchinson) was publisllcd in 198,5 , and lkisFrankenstein: tnythe et philosophie (Prcsscs Ullivcrsitaires tle I'rallcc, Paris) is

forthcoming.

lklichle Le Inoeuff is at the (-.'t??? f re 2NTt?/?'f???C/ de /t7 /?t?t'/?t??'c/2t' z%('-i(?1l f?,'/iklf e inParis. An Englisl translation ()f her lv '/pplf?tt.r?'/?tz-t.' l'hilosoplliqlte (t-d iti ol'lsPayot, Paris, 1980) is about to bc publislled by tllc Athlollc l'ress.

lklichel Deguy has published many volulnes ()f ptlenls alld othcr works since1959. His Llonnant Dcp?zzltrz?'?l

( 198 1 ) was ptlblislled in Ellglislt i1h 1984 llil'vlgtbg$ UC Prcss) . His latest book is lua potl-s-z''c

p? 'est pas .t??//t? (d ititlns duSeuil, Paris, 1987) .

Vincent Carraud is at the University of Paris X l l . I Ie is St't'?tJ/?7'?-c ()f thcBulletin Ctzrf/-uar/c l'Archives J? lhiloulphiel .

Bruno Latour is Profcssor at thc lcolc Ja t.,lille., Paris. I I is N.N'lrlls illcludeLaboratoryA/'e (Princeton , 1 986) , Sciellcc ?1; tbt.'till'l ( l Iarvartl, 1987) all(I lhePa-teurisation of f'rzacc ( 1 Iarvard, l 988) .

Paul Ricoeur is Professor Elzacrittls ()f tllc Ullivttrsity of Paris X. l 1is nanyworks include Freud and Philosopll' (Yale U P) , 111(, t.b/?//?'t7J (tf ./p/e'?>?'t?/t'?-

tions (Northwestern U P) , 1he .&??/t? (1f 7/, elaphol' (-I-()r(?nto L-, P) , l-ilnt, zzpt',/uiharrative (3 vols . : Crllicago l..l

13

) alltl //??7??t-/?t'?//Ft-- (111(1 //?tz lllI1tlall K8't-z'fz/?t-c-

id (J P)(Ctlnbr ge .

ltichard ltearncy, t; Iliversity Lecttlrer il1 Pllilllstlpll).' at U' llivtlrsity Ctlllcgc,(Dublin, is the author of jllany Nvorks ()rl I risll eulttlre alltl I'--tlrtllleall 1.)111 lf)s()-phy, including Iialoglles 7.4.,,'//1 ( ..'lllltetllplll'al' ( b??/??ta??/t//

llllbllt'Al ( 1 984) ,A'Iodenl 51' otlcpFpt???/- 121 /il/rt?/lctz?? 1'11 l'I()-%()ph)' ( 1986) ( lltltl 1 l l all cllttster U I)and The l.V't71.' tl.J llnaglbta 1?b?? ( l I tttchillsllll , 1 988 ) .

lavourless blood, itestial space, accom- Notes on Contributorsn, irreducible to theaages that are central1elling.14 They bringparadox: Could it be?1f is the source of a1lignominy, malaise,that a more gentle

perfluous but with-t and pursuing itssomething like the

'eturn is what thatlls d'T'he Sacrifice ofthat is inverted ands. urbane ape that is(A Report for anY

t spectral creaturel with the essential

'e with tthe unin-such laughter is

tl lines of Bataille's

is too paie and toois nothing other

reatlse oyyvtzyz ineye threatens to

'et duringthe past) the remarkablylicine and villaget of the aeademy,here and now too find the obses-nothing so muchiions thoroughlyzerity to call the

I'lamann in the) . F. Krell, t'Fhe'#E'sif/ll Phaeno-

John Sallis and

Paseal Engel is Matre de Confrences de P/ltl.c.pe at the Univen desScJacex Kdales, Grenoble. He published Identit et rfrence (Presses deI'Ecole Ntnrmale Suprieure, Paris) in 1985, and his Philosophie de la logiquc(Fayard. Paris) is forthcoming.J. J. Lecercle is Professor at the University of Nanterre. His Philosophy,f/zrtlze/zthe

.l-tptaszg Glass (Hutchinson) was published in 1985 and hisFrankenstnh: mythe etphilosophie (presses Universitairesde Franee Paris) isforthcoming. '

Micllle Le Doeuff is at the Centre Ncfortzf de la Recherche Sci?nr/kl/d inParis. An English translation of her L'Imaginaire Philosophique (ditionsPayot, Paris, 1980) is about to be published by the Athlone Press.Michttl Deguy has published many volumes of poems and other works since1959. His DonnantDonnant (1981)was published in English in 1984 Givingfh,g, U C Press). His latest book is La

.ptlco/'r n kst >Tz.& seule (ditions duSeuil, Paris, 1987).

Vincent Carraud is at the University of Paris XIl. He is Secrtaire of theBulletin Ctvz-lJr-c (Archivesde Phllosophie) .

Bruno Latour is Professor at the Ecole des-klines, Paris. His works includeLaboratoryLlj (Princeton, 1986), Science 2Wx4c!2'()rJ (Harvard, 1987) and ThePastcunation ofFrance (Harvard, 1988) .

Paul Ricoeur is Professor Emeritus of the University of Paris X. His manyworks include Freud and Philosophy (Ya1e UPI , The C()?WJ'cl of 'fz//er.pzz/a-tions (Northwestern UP) , The Rule of zjletaphor (Toronto U P) , lme and-N-fzl-zwll'rd (3 vols. : Chicago UP) and Helmeneutics tz?l# the ffzrntzr Sciences(Canlbridge UP) .

Ricllard Kearney, University Lecturer in Plilosophy at U niversity College,Dublfn, is the author of many svorks on lrish culture and European philoso-phy, i ncluding Dialogues zcff/l Colltenlporan' C()?7l?'z?t?z?/t7/ Thinkers ( 1984 ) ,-'blodern a)./t:?t'e?'r?dpll. ,*?/

El ?-o/'tz/? Philosophl'( 1986) (both lanchester UP)and 'lhe l's ke of /n?tzgl'lltrllleol?

( Hutchinson, 1988) .D . C. Barrett is Reader in Plilosoply at the University of S-arwick.Elie Georges Noujain is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at CarletonCollege,Rlinnesota.