Documenting Copper Artifacts of Harappan/Chalcolithic Bagasra: … · The civilization in the Indus...

Transcript of Documenting Copper Artifacts of Harappan/Chalcolithic Bagasra: … · The civilization in the Indus...

Documenting Copper Artifacts of Harappan/Chalcolithic Bagasra: Context, Type and Composition

Ambika Patel1 and P. Ajithprasad2 1. Department of Museology, Faculty of Fine Arts, The Maharaja Sayajirao University

of Baroda, Vadodara – 390002, Gujarat, India (Email: [email protected]) 2. Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, The Maharaja Sayajirao

University of Baroda, Vadodara – 390002, Gujarat, India (Email: [email protected])

Received: 31 August 2015; Accepted: 29 September 2015; Revised: 17 October 2015 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 3 (2015): 219-231

Abstract: Gujarat, the southern regional extension of Indus civilization has reported many Harappan/ Chalcolithic sites with copper artifacts as one of the major category of assemblage. The documentation and classification enable us to understand the functional types and varieties of copper artifacts yielded from the site. The present paper is an outcome of the documentation, classification, typological study and composition analysis of the copper artifact assemblage from the Harappan/Chalcolithic site, Bagasra. The main types of copper artifacts identified fall under the categories such as weapons, implements, ornaments and vessel. The contextual and typological studies of the copper artifacts indicate equal quantity of identifiable copper artifacts from phases 3 and 2 at the site. Majority of the copper artifacts are heavily corroded with almost no core left in them, caused difficulty to choose representative samples for analysis. The compositional analysis of two artifacts indicates the presence of arsenic and zinc as alloy elements in the objects.

Keywords: Gujarat, Harappan, Chalcolithic, Bagasra, Copper Artifacts, Typology, Composition Analysis

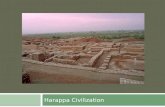

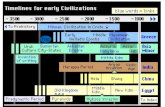

Introduction The civilization in the Indus Valley region, contemporary to Mesopotamia and Egypt came to light through the Excavations in 1920 at Mohenjodaro and Harappa, brought to light the civilized life in the Indian subcontinent dating back to 2500 BC popularly known as Harappan Civilization. The Harappans established themselves over the regions comprised of present day Pakistan and north western India covering an area of 680,000 square kilometers (Kenoyer 1998). Rao (1973) envisaged four provinces of Harappan domain and the region of eastern province consisted of Gujarat, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. Gujarat, the western most state of modern India, and the southward extension of the Indus Valley civilization witnessed many archaeological excavations that sought to extend our understanding of Harappan Civilization (Possehl 1992). Among the varied and impressive array of artifacts produced by Harappans

ISSN 2347 – 5463 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 3: 2015

220

(Kenoyer 1998; Possehl 2002) metal artifacts form a major class of assemblage unearthed from each of the Indus cities (Marshall 1931; Mackay 1938, 1943; Vats 1940; Rao 1979; Lal 1979; Bisht 1997; Kenoyer 1998;) as well as smaller sites (Shaffer 1982; Hedge et al. 1988; Dhavalikar 1992, 1996; Shinde 1992; Sonawane et al. 2003; Bhan et al. 2004; Ajithprasad 2008; Kharakwal et al. 2008, 2009).

Metals carry story of their making in the form of signatures indicating various stages of fabrication and therefore highlight the history of technology and innovations. Technical studies of metal antiquities can be used to unravel the mysteries of proto-historic societies. Based on excavated assemblages from various sites of Indus realm in general it appears that, among the metallic artifact category, copper and copper alloys form a major group. It appears that variety of artifacts namely knives, blades, saws, spears, arrow heads; ornaments such as beads, rings and bangles; house hold materials such as dishes and other vessels; objects of religious importance such as parasu (battle axe), items of economic significance such as scale pans, tablets etc. were fabricated out of copper and copper alloys by the Indus craftsmen (Kenoyer 1998; Vidale 2000; Vidale and Miller 2000).

Though Harappan/Chalcolithic cultural period is rich in quantum and variety of copper artifacts, many of the excavated collections are not yet completely studied and published. Thus it becomes very significant to have site wise detailed study of the context, typology, elemental compositions and methods of production of copper artifact assemblages from various Indus sites so as to have the complete understanding of the copper metallurgy of the region of Gujarat during Indus civilization time. This paper is an attempt to study and understand the context and to catalogue the artifact types of Copper/Bronze objects from Bagasra, Gujarat, Western India.

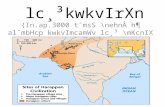

Situating the Site Bagasra/Gola Dhoro (23o 3' 30" N; 70o 37' 10" E), is located on the southern shore of the Gulf of Kachchh in Maliya Taluka of Rajkot District at the meeting point of three major cultural regions namely, Kutch, Saurashtra and North Gujarat (Fig. 1). This provided the site a strategic positioning and enabled it to act as a conduit for the transportation of materials and movement of communities from one region to another during third millennium BC (Sonawane et al. 2003). The material evidences unearthed from the site by the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda from 1996 to 2005, revealed four phases of occupation at the site (Sonawane et al. 2003) and is shown in Table 1.

The Context Phase-I represents the early stage of the Mature/Urban phase Harappan along with Anarta pottery of north Gujarat. Phase-II demarcates the construction of a fortification and incorporates both Classical/Mature Harappan remains and Anarta Pottery and isolated sherds of the Sorath Harappan ceramics. Phase III is remarkable for the predominance of Sorath Harappan pottery over the Classical Harappan and a general

Patel and Ajithprasad 2015: 219-231

221

disorganisation of construction activities at the site. Phase IV is the Post-Mature/Urban Harappan habitation and is distinguished by Sorath Harappan pottery; resembling Rangpur IIC and Rojdi C pottery and by the absence of the Classical Harappan artifacts in the deposit (Sonawane et al. 2003).

Table 1: Phases of Occupation at Bagasra (Courtesy: Sonawane et al. 2003) Context Affiliation

Early Urban/ Phase I Anarta (pre-fortification) and Harappan Urban / Phase II Harappan & Anarta (fortification) Late Urban / Phase III Sorath Harappan (Rangpur IIA & IIB), Anarta & Harappan Post Urban/Phase IV Post Urban Sorath Harappan (Rangpur IIC; Rojdi C)

Figure 1: Bagasra and other Excavated Harappan Sites in Gujarat

As compared to the relatively small size of the settlement (measuring 1.92 hectares and of 7.50 m height), the site yielded good number of copper artifacts (about 250) that included chisels, bangles, knives, axes, points, spear heads, scissors, rings, hooks, rods, beads, ingots and also unique objects like bone handled knives, parasu and a hoard of copper bangles in a copper vessel. Apart from the aforesaid objects, there are materials which indicate copper working such as crucible pieces (Table 2) and slag. A large number of small bits and pieces of copper of negligible size and distorted shapes are categorized as unidentified objects. Amongst the four phase occupation of the site, as far as concentration of copper objects is concerned, Phase I yielded the lowest number

ISSN 2347 – 5463 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 3: 2015

222

constituting 4% while Phase II showed 43% & Phase III with an yield of 47% (Fig. 2). There is a drastic reduction in quantum of artifacts in Phase IV with 4% as compared to earlier phases. Phase II and III represent more or less equal quantum of copper artifacts there by highlighting increased use of copper during both Classical Harappan and Sorath Harappan occupation times of the site.

Table 2: Contextual details of Crucibles from Bagasra Sl. No. An. No. Trench Layer Depth Phase Remarks1 6911 Eo6 3 80 cm II Broken 2 1927 Er13 11 540 cm II Broken 3 6981 Ea12 5 90 cm II Broken 4 7369 Eh2 6 267 cm II Broken 5 3828 Ea11 2 70 cm III Broken 6 4575 Ef8 1 30 cm III Broken

Figure 2: Percentage of Occurrence of Copper objects in Phase I-IV at Bagasra

The settlement highlighted two distinct habitation segments; viz.; fortified northern side and unfortified southern side. The Phase II is noted by the construction of a walled enclosure of 7m thickness made of mud bricks of typical Harappan ratio and the rapid increase in Classical Harappan materials namely unicorn seals. Manufacturing debris and other material evidence of craft activities (shell working, faience working etc.) are more intense inside the fortification area indicating the involvement of the residents within the walled area in the production of stone bead, faience and marine shell craft items (Bhan et al. 2004). The residential structures outside the fortification wall continued to be used and renovated (Chase 2010). Copper artifacts and crucible fragments indicating secondary production was evidenced from both inside and outside of the walled enclosure.

4%43%47%

6% 0% PIP2P3P4Sur.

Patel and Ajithprasad 2015: 219-231

223

Figure 3: Distribution of copper artifacts and crucible fragments in Phase II

(Courtesy: Department of Archaeology & Ancient History, MSU)

The trenches from both inside and outside areas of the fortification of settlement yielded copper artifacts. The two bone handled knives which are unique were reported from outside the fortification. The evidences of copper artifacts from trenches viz., Ea12-16; Eb10, 11 and Eq2 indicate the association of copper implements/tools with industrial working areas (Fig. 3) such as shell working, faience working etc. Looking at

ISSN 2347 – 5463 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 3: 2015

224

the distribution of copper in Phase II, the areas inside the fortification indicated more copper yield compared to outside the fortification. However the evidences for the corroboration of copper working, through the yield of crucibles were more or less uniformly distributed both inside and outside areas.

Typology To have better understanding of the copper artifacts from various sites and to have uniformity in data to compare and contrast, there is a call for developing typology. Typology of copper artifacts by Yule (1885); Miller (1999) etc. also draws our attention towards the need of a formalized typology for Indus copper objects. Yule proposed a rough and detailed classification system for both vessels and ornaments (Yule 1985), while Hieidei J. Miller’s classification of Chanhu-daro metal artifacts is more specific by the combination of morphological and functional perspectives.

The classification applied for copper artifacts in the current work is preliminary and provisional in its nature. This preliminary typology developed for Bagasra copper objects was broadly based on their morphological appearance. The basic documentation register used in the excavation site for registering artifacts (accessioning) called “Antiquity Register” refers to different terms for describing copper artifacts such as “nodules”, “pellets”, “corroded copper object”, “copper pieces” “unidentified copper object” etc. mainly for unidentifiable ones. They are having heavy incrustation and disfigured morphology and constitute the major part of the assemblage. Physical verification of each and every copper artifact from the site has done carefully to overcome the issue of random nomenclature and to identify objects as much as close to their functional perspective.

Unidentified Objects Large numbers of objects are small in size and difficult to identify due to heavy corrosion. All these small unidentifiable fragments were categorized as “unidentified objects” which make the biggest (121 numbers) group. Due to uncertain morphology all the remaining objects have been grouped in to miscellaneous/unidentified category. Majority of them are prills (small and rounded in morphological appearance) and fragments with thick corrosion on their surface make it extremely difficult to assign function. Unidentified objects remain as a major group in phase II and III, their altered, encrusted, de-shaped appearance have affected identification as well as quantification of the type.

Based on morphology the main types classified are, weapons, implements/tools, ornaments and vessel. Quantitatively, the implements/tools and the ornament types are more or less in equal number.

Weapons (?) One Arrowhead and two spear heads (Fig. 4) from the phase II can be considered under the category of weapon. The arrowhead is un-tanged and its swallow tailed barb

Patel and Ajithprasad 2015: 219-231

225

draws parallels with those from other classical Indus sites. The spear heads are flat and leaf shaped without midrib and having short flat tang. They are so heavily corroded, it is difficult to predict whether they have holes on the tang or on the base part of the blade body, which is seen in spear heads from Chanhudaro, Mohanjodaro (Macky1938), Dholavira (Bhist 1997), Lothal (Rao 1977) etc.

Figure 4: Spear Heads

ISSN 2

226

ImpleAnothmechahouse bladesones aand Lsides (trimmimplemutilitarareas o

OrnamItems The tyBangle1991). Rings anotheand I r

VesseTypicascale pwithinmorphcarinafrom reportshould

347 – 5463 He

ements/Tooher categoryanical or ma

hold utilitas, rods and are knife fraothal were (Fig. 6). Raz

med into shments/tools,rian/functionof phase II c

ments of personal

ypes found es are any The banglesare genera

er coiled. Phrespectively

el/Pot al Indus coppans. The mn a copperhologically sated body an

a sheet of ted similar kder.

P11

eritage: Journa

ols y of artifacanual tasks arian works celts (Fig. 5

agments andL-shaped w

zors might hape. Since , it is verynal perspect

can highlight

Figure 5: I

l adornmentat Bagasra circlets mads from Bagaslly small ro

hase III yield while Phase

pper/bronze most interestr vessel assimilar to and sagging b

copper usikind of squa

1

al of Multidisci

t is implemsuch as cretc. The va

). Blade tood razor (par

while Bagasrhave been pmany of th

y difficult ttives. Detailt more insigh

Implements

t form anothare, bangles

de of continsra were thic

ound and soded maximue IV was dev

vessel formting discovessigned to squat med

base. It appeng a variet

at vessel from

P2

27

Phas

iplinary Studie

ment/tool waft producti

arieties of imols, made ourasu). The raa yielded a

produced byhe blades pto assign thled study ofht on these l

s/Tools from

her categorys, rings, spinually homock ones witholid, represe

um number ovoid of orna

ms include jaery of Bagas

the end odium size, sqears that thety of fabricm Mohenjo-

P3

3

ses

es in Archaeolo

which mightion, agricult

mplements/tut of copper azor reporterazor with

y hammeringperhaps usehe blade to

f the implemlines.

m Phases I to

y of Indus ciral rings, wogenous mah round andented two tof ornament

aments.

ars, pots, bosra was a hoof urban pquat shape,

e vessel seemcation techndaro with d

34

ogy 3: 2015

t have beenture relatedools from Bsheets and

ed from Mocurved blad

g sheet metaed as multools to the

ments from t

o IV

copper/bronwire and beaaterial (Ken

d crescent crotypes one sts followed b

owls, dishesoard of coppphase. The

wide moutms to be manniques. Mackdistinctive le

P46

n used in d activities; Bagasra are

noticeable henjo-daro de on both al before it ifunctional

eir specific the activity

nze objects. ad (Fig. 7).

noyer et al. oss section. simple and by Phase II

, pans and per objects

vessel is th, sharply nufactured kay (1938) dge on the

Patel and Ajithprasad 2015: 219-231

227

Figure 6: Parasu/Battleaxe/Razor from Bagasra

Corroboration of Copper Working The proximity of Gola Dhoro/Bagasra to the little Rann of Kachchh and surrounding saline areas provide a conducive environment for copper artifacts to deteriorate in a faster rate. This supports the occurrence of heavily corroded copper artifacts in large numbers. It is a tough job for an archaeologist to identify the fabrication areas/working areas of metal at in situ situation. Fragmentary crucibles and ‘ingots’ from the site indicate some sort of secondary production. Structures associated with Phase I, a small

ISSN 2

228

brick associfrom tperhapworkinstagesin the secondslag insmeltioccurrunifor(Tablewith svitrifiecoppeout in

The scphase appeamay eMillertill daoriginintermdepenprodu(directwell. HThe evviews.

347 – 5463 He

F

structure inated with cthis area alops used forng activities

s itself. Thus inner side o

dary producndicates theing. The srence both rm pattern. Te 2). The extestraw, whiched. Some ofr sticking toit.

canty numbsites could

rs that it is enable one tor (1999), opinte indicate mal smelting

mediary stagnding upon uction, viz., t shaping of However, tovidences fro.

01020

eritage: Journa

Figure 7: Or

n trench Ebcopper workong with ser melting cs directing the recover

of them andction i.e., me copper wospatial distrinside and Trench Eo6, erior surface

h during firif them haveo interior sid

er of crucibl represent smore likely

o draw defines that basemelting (secg ingots to ge in the pro

the state ocasting (refthe metal) m

ools and techom Bagasra

P12

al of Multidisci

rnaments fro

b11 adjacentking (Sonaweveral piecescopper ingothe economy of heavy s

d a few slag melting, castiorking at thribution of

outside theEr13, Ea12,

e of the crucng might ha

e shown smde of the cru

le fragmentssmall scale y melting aninite distincted on the pucondary prod

produce socess of prodof the metalfers to man

might have ahniques of balso draw p

P2

12

Pha

iplinary Studie

om Phases I

t to westernwane et al. 2s of copper/

ots. These emic prosperitsand temperpieces yield

ing/fabricatihe site main

the crucible fortificatioEh2, Ea11 a

cible fragmeave served a

moky black pucible suppo

s with coppsmelting of nd not smetion between

ublished dataduction) ratsecondary oduction. Thel while wornipulation oadopted by tboth the cateparallels with

P3

18

ases

es in Archaeolo

to IV at Bag

n fortificatio2003). Intens/bronze impevidences clty of this sered cruciblesded from theon etc. Thely secondarles from thon wall (Figand Ef8 yieldents were mas insulatingpatch on theorts the proc

per prills rephigh qualit

elting. Furthn the two pa on copper her than smor refined e methods orking. The tof molten mthe metal woegories remah the above

P40

ogy 3: 2015

gasra

on wall appse use of fir

plements andlearly indicaettlement ins with coppee site indica negligible

ry melting rhe site indicg. 3) more ded crucibleade of fine c

g material ane exterior sucess of melti

ported from ty copper. H

her archaeomrocesses. Keworking at

melting. The ingots is a

of productiotwo main mmetal) and orkers of Indain more or

e mentioned

pear to be re is noted d crucibles ate copper n its initial er adhering ate possible amount of

rather than cates their or less in

e fragments clay mixed nd was not urface. The ing carried

Harappan However it metric tests enoyer and Indus sites melting of

a common n can vary

methods of fabrication dus sites as

less same. published

Patel and Ajithprasad 2015: 219-231

229

Composition Analysis To understand the composition of the copper artifacts two representative samples were chosen for analysis. The chemical composition of the chosen samples was determined by using Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDAX) method. As majority of the objects are heavily corroded, to expose the inner layer, cleaning was done by abrading paper. The exposed inner surface was subjected to EDAX and the composition was determined.

Table 3: EDAX Composition

The objects were deeply corroded and mineralized to a great extent with heavy encrustation. Due to this, the composition indicated high yield of oxygen and chlorine. Zinc was present in both the objects. Arsenic shows its presence in small quantities both in bangle and ring. Arsenic is a common constituent of many copper ores like energite and famitinite and passes on to the metal unless it is roasted for a long period of time at a temperature higher than 5000C. Presence of Arsenic points out its possible application in casting technique applied for the making of the bangle and ring with the help of moulds. Micro structural studies can bring out more information on manufacturing techniques. Lead is absent in both the objects. Fe is present in both the objects and Iron being a common constituent in copper ores like chalcopyrite, pyrolite etc., and it usually passes on to the metal while smelting. Complete removal of iron from the ore is difficult and it requires high temperature as 1200O C. This indicates that the ore used at Bagasra had iron content in it and also the smelting might have done below 1200O C.

Conclusion The contextual and typological study of the copper artifacts from Bagasra showcases occupational phases III and II with more or less equal quantity of identifiable copper artifacts. Though, Phase III, which represents the amalgamation of three cultural traits such as Classical Harappan, Anarta and Sorath elements identification of “signature type” copper artifacts for Sorath Harappan was not feasible through this preliminary study. However the presence of relatively higher number of ornaments points to some indication of Sorath influence. The preliminary compositional analysis of two artifacts indicates the presence of arsenic and zinc as alloy elements in the objects. The presence of iron in the objects indicates the use of iron rich ore for production. Beyond the typological examinations, a detailed comparative analytical study of Phase II and III is targeted to understand the differences and similarities as well as the growth and development of technological traditions. More detailed typological and contextual studies along with analytical methods for copper assemblages from other sites of this region are necessary to have better understanding of Indus metal technology over time.

An. No. Object Cu Zn As Pb O C Cl Al Si S Ca FeBSR 6310

Bangle 58.94 2.21 0.44 Ab 15.55 19.96 0.22 0.45 1.17 0.59 0.43 Ab

BSR 4494

Ring 34.39 1.73 0.25 Ab 24.37 20.25 1.26 0.47 1.78 Ab 0.58 5.30

ISSN 2347 – 5463 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 3: 2015

230

Acknowledgements We express our sincere gratitude to Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda for all kinds of support. We also extend thanks to Prof. Jonathan Mark Kenoyer for his support and suggestions.

References Ajithprasad, P. 2008. Jaidak(Pithad): a Sorath Harappan site in Jamnagar district,

Gujarat and its architectural features; Occasional Paper 4; Linguistics, Archaeology and the Human Past. (Eds) Toshiki Osada and Akinori Uesugi. Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Koyoto, Japan. pp 83-99.

Bhan, K.K., V.H. Sonawane, P. Ajithprasad and S. Pratapchandran. 2004. Excavations of an Important Harappan Trading and Craft Production Center at Goladhoro (Bagasra), on the Gulf of Kutch, Gujarat, India. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in History and Archaeology, Center for Advanced Study, Department of Ancient Culture and Archaeology, University of Allahabad. Vol 1(2),pp.153-158.

Bisht, R. S. 1997. Dholavira Excavations: 1990-94. J. P. Joshi, D. K. Sinha, S. C. Saran, C. B. Mishra and G. S. Gaur (eds.). Facets of Indian Civilization - Recent perspectives – (Essays in Honour of Prof. B. B. Lal): Vol. I (Prehistory and Rock-Art, Proto History): 107-120. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

Chase, B. A. 2010. Social Change at the Harappan Settlement of Gola Dhro: A Reading from Animal Bones. Antiquity 84: 528-543.

Dhavalikar, M. K. 1992. Kuntasi: A Harappan Port in Western India. C. Jarriage (ed.). South Asian Arachaeology 1989: 73-82. Madison: Prehistory Press.

Dhavalikar, M.K., M.H.Raval and Y.M.Chittalwala 1996. Kuntasi-a Harappan Emporium on the west coast, Pune. Deccan College.

Kenoyer, J. M. and H. M.-L. Miller. 1999. Metal Technologies of the Indus Valley Tradition in Pakistan and Western India. V. C. Piggot (ed.). The Emergence and Development of Metallurgy: 107-151. Philadelphia: University Museum.

Kenoyer, J. M., M. Vidale and K. K. Bhan. 1991. Contemporary Stone Bead Making in Khambhat, India: Patterns of Craft Specialization and Organization of Production as Reflected in the Archaeological Record. World Archaeology 23 (1) Craft Production and Specialization: 44-63.

Kenoyer, J.M. 1998. Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. American Institute of Pakistan Studies. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

Kharakwal, J. S., Y.S. Rawat and T. Osada. 2008. Preliminary Observations on the Excavation at Kanmer, Kachchh, India 2006-2007. T. Osada and A. Uesugi (Eds.). Occasional Paper 5: Linguistics, Archaeology and the Human Past: 5-23. Kyoto: Research Institute for Humanity and Nature.

Kharakwal, J. S., Y.S. Rawat and T. Osada. 2009. Excavations at Kanmer: A Harappan Site in Kachchh, Gujarat. Puratattva 39: 147-164.

Lal, B.B. 1979. Kalibangan and the Indus Civilization. D.P.Agrawal and D.K.Chakrabarti (Eds.) Essays in Indian Protohistory, Delhi, pp.65-97.

Patel and Ajithprasad 2015: 219-231

231

Mackay, E.J.H. 1938. Further Excavations at Mohanjodaro, 2 vols. Delhi. Patel, A. 2005-2006. Copper Artifacts from Bagasra (Gola Dhoro), a Harappan Site of

Gujarat, Western India. Puratattva 36: 222-231. Possehl, G. L. 1986. Rojdi: The Investigation of a Prehistoric Town in India. American

Journal of Archaeology 90 (4): 467-468. Possehl, G. L. 2002. Harappans and Hunters: Economic Interaction and Specialization

in Prehistoric India. K. D. Morrison and L. L. Junker (eds.). Forager-Traders in South and Southeast Asia Long-Term Histories: 62-76. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Possehl, G.L.1992. The Harappan Civilization in Gujarat: The Sorath and Sindhi Harappans. The Eastern Anthropologist. Vol.45. No.1-2. Ethnographic and Folk Culture Society, Lucknow. pp. 117-154.

Rao, S. R. 1973. Lothal and the Indus Civilization. Bombay: Asia Publishing House. Rao, S.R. 1979. Lothal a Harappan Port Town(1955-62). Memoirs of the Archaeological

Survey of India 78.Vol.1. New Delhi. Shinde,V. 1992. Excavations at Padri- 1990-91: A preliminary Report, In Man and

Environment XVII (1): 79-86. Sonawane,V.H. et al. 2003. Excavation at Bagasra-1996-2003: A Preliminary Report,

Man and Environment. Vol. XXVIII (2). pp. 21-50. Vats, M.S. 1940. Excavations at Harappa, Vol.2. Government of India. Delhi. Vidale, M. 2000. The Archaeology of Indus Crafts: Indus crafts people and why we study them.

Rome. Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Orientale. Vidale, M., & Miller, H. 2000. On the development of Indus Technological virtuosity

and its relation to social structure. In South Asian Archaeology 1997, Rome (pp.115-132). Naples. Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Orientale and Istituto Universitario Orientale.

Yule, P. 1985. Metal work of the Bronze Age in India. C. H. Beck’sche Verlagbuch handlung. Munich.