Dispatches (Winter 2009)

-

Upload

doctors-without-borders-medecins-sans-frontieres-msf-canada -

Category

Documents

-

view

233 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Dispatches (Winter 2009)

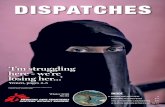

DispatchesM S F C A N A D A N E W S L E T T E R

Vol.11, Ed.1

IN THIS ISSUE2

4

6

8

10

12

14

15

1999 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate

Fleeing the violence

Congo’s lost people

Water everywhere,but not a drop to drink

Malnutrition inUganda: Pushingback against achronic struggle

Meeting healthcareneeds amid mountains and desert

15,000 come toRefugee Camp in theHeart of the City

Suddenly… a book

Canadians on mission

DEMOCRATICREPUBLIC OF CONGO:

CONDITION CRITICAL

© D

omin

ic N

ahr

/ O

eil

Pub

lic

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1 page 3

D e m o c r a t i c R e p u b l i c o f C o n g o

As fighting in North Kivu, DemocraticRepublic of Congo is making the

headlines, the neighbouring district ofHaut-Uele is also affected by violence.Rebels from the Lord’s Resistance Army(LRA) are terrorizing people, looting,burning villages, abducting children andkilling adults. Médecins Sans Frontières(MSF) went to the town of Dungu, whichwas attacked by the rebels on Nov. 1,2008 to assess the needs of the popula-tion. An MSF medical team began activi-ties in Dungu on Nov. 10.

J. (name withheld) is a carpenter working inthe convent in Duru, a village many hours’walking distance from Dungu. J. has a wifeand five children and also cares for a youngniece. He told a member of the MSF teamwhat happened to his family. His story illus-trates the distress suffered by civilians whofall prey to the rebels’ brutality and have toflee their villages.

It all started around 1 p.m. I had just fin-ished cutting a cluster of palm nuts some250 metres away from the market and theconvent and was just about to get backwhen a child from the village gestured inmy direction warning me not to get closer.According to him, the LRA had surroundedthe mission and had even abducted chil-dren from the secondary classes.

I immediately went home and got the sixchildren and my wife together; as ourneighbour was away I took his four chil-dren too and we fled to the bush, two kilo-metres away from the village. There westayed two days, next to our plot. Wecould feed on beans and aubergines thatI got from our field and that my wifecooked in empty cans as we didn’t haveany saucepan.

A boy who had been captured by the LRAbut had managed to escape after three days

joined us. He said that the LRA had left thevillage at around 3 a.m. and had crossedthe river. Together with our neighbour whohad joined us in the bush, we decided toreturn to the village to see what had hap-pened and also to get some essentialthings. It was quite distressful to see thatmy entire compound had been burneddown: the three small huts, the straw hut,the kitchen and the goats’ shed. Everythinghad been burned down. My six goats werelying on the ground, shot dead.

“MY NEIGHBOUR DECIDED TO CROSS THEFOREST INTO SUDAN WITH HIS FAMILY”

Overcoming our pain we rapidly cut up agoat and shared it between us. I addedthe rest of two burnt chickens and carriedthe lot on my back, returning to our hid-ing place. My neighbour decided to crossthe forest into Sudan with his family. Asfor us, as my wife didn’t want to go to this

FLEEING THE VIOLENCE

© D

omin

ic N

ahr

/ O

eil

Pub

lic

© E

spen

Ras

mus

sen

© V

anes

sa V

ick

© S

ven

Torf

inn

© D

omin

ic N

ahr

/ O

eil

Pub

lic

country which she doesn’t know, wedecided to go the next day to Dunguwhere we have relatives.

The next day, a Sunday, we set out forDungu at around 4 p.m. to get to Kpaika, avillage, the same day. When we got toKpaika my eight-year-old son had swollenlegs after this long walk, so we decided torest for the night in the chapel and to leaveearly the next morning.

Around 4 a.m. we were woken up by gun-shots and people screaming. We fled – mywife put our youngest daughter on her backand carried our eight-year-old son; Igrabbed our three-year-old son. My wife fellinto a hole, so I put the toddler down on theground to help her get out. That’s when anLRA soldier spotted us and gave chase. Ibarely managed to get my wife out of thehole and to flee with her. I then realized,too late, that I had left the toddler behind

and I could hear him scream, but it was toolate, impossible to turn back without riskingto get caught, all of us.

A MIRACLE

From the forest, where we hid, we tried toget some news. People said that many hadbeen killed in Kpaika. Around 11 a.m. itwas completely silent. We then heard thefaint noise of leaves being trampled bymany people. We approached carefullyand saw that the noise was coming fromthe road, where many people were fleeing.We asked everyone if they had seen a lit-tle boy, alone on the road. Eventually,someone told us that he had seen an LRAsoldier carrying our son on his back. Thisnews drove us to despair.

My wife and I decided to save the remain-ing five children by taking them away asquickly as possible, knowing that by

doing so we were getting ever furtheraway from the little one. So we joined theflow of fleeing people and arrived inKiliwa on Tuesday. Then, through somemiracle we learned in Kiliwa that our lit-tle boy had been freed, that a well-mean-ing person had taken care of him and wastaking him to Dungu.

We spent the night outside under a mangotree on the road side, dehydrated andexhausted, but with a lighter heart whenthinking of our son, hoping he mightalready be on his way. We left Kiliwa ataround 4 a.m. and walked all day. Wereached Dungu after 6 p.m. We were givenrefuge by the priests and we have been withthem for four days now. We’re waiting forour little one.

Claude MahoudeauCommunications officer

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1 page 3

D e m o c r a t i c R e p u b l i c o f C o n g o

As fighting in North Kivu, DemocraticRepublic of Congo is making the

headlines, the neighbouring district ofHaut-Uele is also affected by violence.Rebels from the Lord’s Resistance Army(LRA) are terrorizing people, looting,burning villages, abducting children andkilling adults. Médecins Sans Frontières(MSF) went to the town of Dungu, whichwas attacked by the rebels on Nov. 1,2008 to assess the needs of the popula-tion. An MSF medical team began activi-ties in Dungu on Nov. 10.

J. (name withheld) is a carpenter working inthe convent in Duru, a village many hours’walking distance from Dungu. J. has a wifeand five children and also cares for a youngniece. He told a member of the MSF teamwhat happened to his family. His story illus-trates the distress suffered by civilians whofall prey to the rebels’ brutality and have toflee their villages.

It all started around 1 p.m. I had just fin-ished cutting a cluster of palm nuts some250 metres away from the market and theconvent and was just about to get backwhen a child from the village gestured inmy direction warning me not to get closer.According to him, the LRA had surroundedthe mission and had even abducted chil-dren from the secondary classes.

I immediately went home and got the sixchildren and my wife together; as ourneighbour was away I took his four chil-dren too and we fled to the bush, two kilo-metres away from the village. There westayed two days, next to our plot. Wecould feed on beans and aubergines thatI got from our field and that my wifecooked in empty cans as we didn’t haveany saucepan.

A boy who had been captured by the LRAbut had managed to escape after three days

joined us. He said that the LRA had left thevillage at around 3 a.m. and had crossedthe river. Together with our neighbour whohad joined us in the bush, we decided toreturn to the village to see what had hap-pened and also to get some essentialthings. It was quite distressful to see thatmy entire compound had been burneddown: the three small huts, the straw hut,the kitchen and the goats’ shed. Everythinghad been burned down. My six goats werelying on the ground, shot dead.

“MY NEIGHBOUR DECIDED TO CROSS THEFOREST INTO SUDAN WITH HIS FAMILY”

Overcoming our pain we rapidly cut up agoat and shared it between us. I addedthe rest of two burnt chickens and carriedthe lot on my back, returning to our hid-ing place. My neighbour decided to crossthe forest into Sudan with his family. Asfor us, as my wife didn’t want to go to this

FLEEING THE VIOLENCE

© D

omin

ic N

ahr

/ O

eil

Pub

lic

© E

spen

Ras

mus

sen

© V

anes

sa V

ick

© S

ven

Torf

inn

© D

omin

ic N

ahr

/ O

eil

Pub

lic

country which she doesn’t know, wedecided to go the next day to Dunguwhere we have relatives.

The next day, a Sunday, we set out forDungu at around 4 p.m. to get to Kpaika, avillage, the same day. When we got toKpaika my eight-year-old son had swollenlegs after this long walk, so we decided torest for the night in the chapel and to leaveearly the next morning.

Around 4 a.m. we were woken up by gun-shots and people screaming. We fled – mywife put our youngest daughter on her backand carried our eight-year-old son; Igrabbed our three-year-old son. My wife fellinto a hole, so I put the toddler down on theground to help her get out. That’s when anLRA soldier spotted us and gave chase. Ibarely managed to get my wife out of thehole and to flee with her. I then realized,too late, that I had left the toddler behind

and I could hear him scream, but it was toolate, impossible to turn back without riskingto get caught, all of us.

A MIRACLE

From the forest, where we hid, we tried toget some news. People said that many hadbeen killed in Kpaika. Around 11 a.m. itwas completely silent. We then heard thefaint noise of leaves being trampled bymany people. We approached carefullyand saw that the noise was coming fromthe road, where many people were fleeing.We asked everyone if they had seen a lit-tle boy, alone on the road. Eventually,someone told us that he had seen an LRAsoldier carrying our son on his back. Thisnews drove us to despair.

My wife and I decided to save the remain-ing five children by taking them away asquickly as possible, knowing that by

doing so we were getting ever furtheraway from the little one. So we joined theflow of fleeing people and arrived inKiliwa on Tuesday. Then, through somemiracle we learned in Kiliwa that our lit-tle boy had been freed, that a well-mean-ing person had taken care of him and wastaking him to Dungu.

We spent the night outside under a mangotree on the road side, dehydrated andexhausted, but with a lighter heart whenthinking of our son, hoping he mightalready be on his way. We left Kiliwa ataround 4 a.m. and walked all day. Wereached Dungu after 6 p.m. We were givenrefuge by the priests and we have been withthem for four days now. We’re waiting forour little one.

Claude MahoudeauCommunications officer

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1

South Kivu, Democratic Republic ofCongo (DRC) is infamous for its history

of violence, especially acute during the warperiods of the 1990s and early 2000s.People here are torn by conflict. They’reworn out. They’ve been suffering for somany decades, with no chance to recover.They’re weary. The public institutions, gov-ernment structures, and infrastructure –none of them function in these mountains.

In Baraka, Médecins Sans Frontières(MSF) runs the only functioning hospitalin a zone where many people have to walkfive days from where they live to reach it.

Some months ago, a man came in fromthe bush to ask MSF to help some fami-lies that had escaped fighting betweentwo rebel groups. To reach those who hadfled meant a nine-hour drive on a dirtroad, then nine hours by foot on barelyvisible jungle footpaths.

I journeyed there with an MSF doctor, atranslator and a guide from the communi-ty. We were covered in mud as we crossedrivers in the pouring rain and fought ourway through tall grasses. Each of us wascarrying heavy backpacks with food andwater rations for four days, plus a blanket,a change of clothes and an emergencymedical kit. We wouldn’t be able to treateveryone, but we needed to assess howlong it took to get there, how many people

there were, what was causing the mostprevalent diseases as well as deaths.

As we reached the top of a plateau whichopened up to rolling green hills, we werestruck by the beauty of the region. Huts ofsticks and mud with straw roofs sooncame into view. The numbers were shock-ing: there were surely about 10,000 dis-placed people hidden away here.

It was the greatest misery I’ve ever wit-nessed. They were here in isolation with nooutsiders ever knowing. The first hadescaped here seven months earlier, andsubsequent waves had joined them as vil-lage after village was destroyed in fighting.It was shocking. We were the first muzun-gus (white people) to have ventured to thatarea. The displaced people just stared at usin disbelief, and we at them.

They were originally from a good distanceto the north where a historical conflict leftthem living on a battle ground. The con-flict has involved the looting of villages,the raping of women, the setting of fires,the slaughtering of animals, and randomshootings. This is what happens in thesewars; it’s nasty. It’s no wonder familiesflee for their lives.

You hear things in the news about howthe United Nations or aid agencies cometo the rescue to establish camps for inter-

nally displaced people, supplying themwith plastic sheeting, water and food.But here was an isolated group sufferingin silence.

It was cold, windy and wet in these moun-tains. As many as a dozen people lived ineach hut, huts so awful you wouldn’tdeign to put farm animals in them. Nomattresses or blankets – people had nochoice but to lay in the mud. There waspotential farmland in the area but due toa lack of seeds to cultivate, food wasscarce. Some reported they only ate twoto three times a week. They received thisfood usually through what we call transac-tional sex, wherein the women would havesex with local men in order to receivefood, if only a little rice to feed their fam-ilies. Women were often raped by residentmen or local military patrols.

The health of this lost group of 10,000, afive-day walk from our hospital, wasequally shocking. Women were deliveringbabies in isolation, with up to 30 per centdying in childbirth. There were manycomplex obstetrical cases because thewomen are very small hipped, and whenalready malnourished and weak, child-birth can be dangerous. Too many womenwere dying this way, and the infant deathrate was also unacceptably high. Mostwomen said they had lost at least onechild, usually due to chronic diarrhea

(likely cholera) and malnutrition. All told,there were multiple symptoms of generalweakness meaning people were too ill tocultivate their fields or do much of any-thing to sustain a livelihood.

Water and sanitation were abysmal. Theywould use the same water for bathing asfor cooking. This is typical in a refugeecamp before nongovernmental organiza-tions arrive – complete disorder and nosupport system.

During this first visit, we did a lot of focusgroups with men and women, separately,to better understand what they needed.With their beliefs in traditional medicineand evil spirits, they believed they werecursed because 100 children had sud-denly died. The symptoms they described– visible red spots and the curse passingfrom one child to another – sounded likea measles outbreak.

All around us there were sick and dyingpeople, but we didn’t have the medicalcapacity to test and treat everyone on thisvisit. The priority was to report back on whatwe were seeing in order to galvanize longer-term support for them. Still, Julie, the doc-tor, would often throw off her backpack andstart treating the severe, life-threateningcases. We were there for three days only,with a gruelling walk ahead of us to returnto our MSF base for the necessary suppliesto treat them properly.

Upon our return to Baraka, we presentedthe needs to other aid organizations to con-vince them to go and start helping thesepeople. The problem for MSF is that we arecompletely stretched in North Kivu, wherefull-scale war has erupted once again.

There are so many internally displaced peo-ple harmed by conflict, so many needs, andso many impossible choices for us as anorganization with limited resources.

The best that MSF could do in this casewas to bear witness and to lobby. Nowthings are moving forward. We have con-vinced the ministry of health to set up someclinics in this area. So if we can take anysense of accomplishment from this, it isthat we were the first to find this area, thefirst to witness what they are experiencing,to give them a voice, and to make decision-makers care about their suffering andlonger-term health needs. Other organiza-tions will help provide things like shelterand food. Materials for houses, medicine,all will be brought by foot. There is no otherway to do it right now.

There is so much need in DRC, particularlyin the Kivus with war raging in the North,and the South recovering from decades ofwar that could re-ignite at any moment.This is one particular instance where Ihelped give voice to a community of people,and I am very proud I did. Tragically, thereis too much happening here to assist justthis one community – as one of so manythat are suffering in this region.

Tara NewellProject coordinator

Tara Newell, from London, Ontario isa project coordinator with MSF.Newell is a former federal public ser-vant and has been working for MSFsince 2004.

The humanitarian crisis in DemocraticRepublic of Congo (DRC) is not new.For more than 15 years, armed groupsand national armies have been fight-ing each other here. Millions ofCongolese people have suffered anddied in successive wars.

The conflict has been particularlyunrelenting in DRC’s eastern pro-vinces. Here, hundreds of thousandsof people have spent years runningfrom war. For these men, women andchildren, there seems to be no hopefor a normal life. In late August 2008,the conflict began escalating onceagain, causing more displacementand misery.

MSF has been working in DRC since1981, trying to relieve suffering inplaces where others are unwilling orunable to help. Currently, MSF is serv-ing displaced people and local resi-dents throughout the conflict zone.The organization is providing primaryand secondary healthcare, includingsurgery, at hospitals and health cen-tres. MSF is also running mobile clin-ics and cholera treatment centres, andproviding mental healthcare, as wellas distributing clean water and basicrelief items.

CONGO’S LOST PEOPLE

AN UNRELENTING

CRISIS

We can’t all go, but we can help those who do.We’ve reached some, but there are many, many more. The people of eastern DRC are in critical condition.

See their plight and learn how you can help MSF reach them. Visit www.msf.ca

© T

eres

a S

ancr

isto

bal

© T

ara

New

ell

© Cédric Gerbehaye / Agence VU page 5

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1

South Kivu, Democratic Republic ofCongo (DRC) is infamous for its history

of violence, especially acute during the warperiods of the 1990s and early 2000s.People here are torn by conflict. They’reworn out. They’ve been suffering for somany decades, with no chance to recover.They’re weary. The public institutions, gov-ernment structures, and infrastructure –none of them function in these mountains.

In Baraka, Médecins Sans Frontières(MSF) runs the only functioning hospitalin a zone where many people have to walkfive days from where they live to reach it.

Some months ago, a man came in fromthe bush to ask MSF to help some fami-lies that had escaped fighting betweentwo rebel groups. To reach those who hadfled meant a nine-hour drive on a dirtroad, then nine hours by foot on barelyvisible jungle footpaths.

I journeyed there with an MSF doctor, atranslator and a guide from the communi-ty. We were covered in mud as we crossedrivers in the pouring rain and fought ourway through tall grasses. Each of us wascarrying heavy backpacks with food andwater rations for four days, plus a blanket,a change of clothes and an emergencymedical kit. We wouldn’t be able to treateveryone, but we needed to assess howlong it took to get there, how many people

there were, what was causing the mostprevalent diseases as well as deaths.

As we reached the top of a plateau whichopened up to rolling green hills, we werestruck by the beauty of the region. Huts ofsticks and mud with straw roofs sooncame into view. The numbers were shock-ing: there were surely about 10,000 dis-placed people hidden away here.

It was the greatest misery I’ve ever wit-nessed. They were here in isolation with nooutsiders ever knowing. The first hadescaped here seven months earlier, andsubsequent waves had joined them as vil-lage after village was destroyed in fighting.It was shocking. We were the first muzun-gus (white people) to have ventured to thatarea. The displaced people just stared at usin disbelief, and we at them.

They were originally from a good distanceto the north where a historical conflict leftthem living on a battle ground. The con-flict has involved the looting of villages,the raping of women, the setting of fires,the slaughtering of animals, and randomshootings. This is what happens in thesewars; it’s nasty. It’s no wonder familiesflee for their lives.

You hear things in the news about howthe United Nations or aid agencies cometo the rescue to establish camps for inter-

nally displaced people, supplying themwith plastic sheeting, water and food.But here was an isolated group sufferingin silence.

It was cold, windy and wet in these moun-tains. As many as a dozen people lived ineach hut, huts so awful you wouldn’tdeign to put farm animals in them. Nomattresses or blankets – people had nochoice but to lay in the mud. There waspotential farmland in the area but due toa lack of seeds to cultivate, food wasscarce. Some reported they only ate twoto three times a week. They received thisfood usually through what we call transac-tional sex, wherein the women would havesex with local men in order to receivefood, if only a little rice to feed their fam-ilies. Women were often raped by residentmen or local military patrols.

The health of this lost group of 10,000, afive-day walk from our hospital, wasequally shocking. Women were deliveringbabies in isolation, with up to 30 per centdying in childbirth. There were manycomplex obstetrical cases because thewomen are very small hipped, and whenalready malnourished and weak, child-birth can be dangerous. Too many womenwere dying this way, and the infant deathrate was also unacceptably high. Mostwomen said they had lost at least onechild, usually due to chronic diarrhea

(likely cholera) and malnutrition. All told,there were multiple symptoms of generalweakness meaning people were too ill tocultivate their fields or do much of any-thing to sustain a livelihood.

Water and sanitation were abysmal. Theywould use the same water for bathing asfor cooking. This is typical in a refugeecamp before nongovernmental organiza-tions arrive – complete disorder and nosupport system.

During this first visit, we did a lot of focusgroups with men and women, separately,to better understand what they needed.With their beliefs in traditional medicineand evil spirits, they believed they werecursed because 100 children had sud-denly died. The symptoms they described– visible red spots and the curse passingfrom one child to another – sounded likea measles outbreak.

All around us there were sick and dyingpeople, but we didn’t have the medicalcapacity to test and treat everyone on thisvisit. The priority was to report back on whatwe were seeing in order to galvanize longer-term support for them. Still, Julie, the doc-tor, would often throw off her backpack andstart treating the severe, life-threateningcases. We were there for three days only,with a gruelling walk ahead of us to returnto our MSF base for the necessary suppliesto treat them properly.

Upon our return to Baraka, we presentedthe needs to other aid organizations to con-vince them to go and start helping thesepeople. The problem for MSF is that we arecompletely stretched in North Kivu, wherefull-scale war has erupted once again.

There are so many internally displaced peo-ple harmed by conflict, so many needs, andso many impossible choices for us as anorganization with limited resources.

The best that MSF could do in this casewas to bear witness and to lobby. Nowthings are moving forward. We have con-vinced the ministry of health to set up someclinics in this area. So if we can take anysense of accomplishment from this, it isthat we were the first to find this area, thefirst to witness what they are experiencing,to give them a voice, and to make decision-makers care about their suffering andlonger-term health needs. Other organiza-tions will help provide things like shelterand food. Materials for houses, medicine,all will be brought by foot. There is no otherway to do it right now.

There is so much need in DRC, particularlyin the Kivus with war raging in the North,and the South recovering from decades ofwar that could re-ignite at any moment.This is one particular instance where Ihelped give voice to a community of people,and I am very proud I did. Tragically, thereis too much happening here to assist justthis one community – as one of so manythat are suffering in this region.

Tara NewellProject coordinator

Tara Newell, from London, Ontario isa project coordinator with MSF.Newell is a former federal public ser-vant and has been working for MSFsince 2004.

The humanitarian crisis in DemocraticRepublic of Congo (DRC) is not new.For more than 15 years, armed groupsand national armies have been fight-ing each other here. Millions ofCongolese people have suffered anddied in successive wars.

The conflict has been particularlyunrelenting in DRC’s eastern pro-vinces. Here, hundreds of thousandsof people have spent years runningfrom war. For these men, women andchildren, there seems to be no hopefor a normal life. In late August 2008,the conflict began escalating onceagain, causing more displacementand misery.

MSF has been working in DRC since1981, trying to relieve suffering inplaces where others are unwilling orunable to help. Currently, MSF is serv-ing displaced people and local resi-dents throughout the conflict zone.The organization is providing primaryand secondary healthcare, includingsurgery, at hospitals and health cen-tres. MSF is also running mobile clin-ics and cholera treatment centres, andproviding mental healthcare, as wellas distributing clean water and basicrelief items.

CONGO’S LOST PEOPLE

AN UNRELENTING

CRISIS

We can’t all go, but we can help those who do.We’ve reached some, but there are many, many more. The people of eastern DRC are in critical condition.

See their plight and learn how you can help MSF reach them. Visit www.msf.ca

© T

eres

a S

ancr

isto

bal

© T

ara

New

ell

© Cédric Gerbehaye / Agence VU page 5

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1 page 7

H a i t i

In early September 2008, hurricanes Gustav, Hanna andIke ravaged Haiti.

Nearly 800 people died, and tens ofthousands were left homeless. Roads

and infrastructure were destroyed. Thelandscape in the northwestern city ofGonaives was desolate.

Before the hurricanes, the inhabitants ofGonaives had access to many wells, and anaqueduct system served certain neighbour-hoods. It took just a few hours for everythingto be destroyed. Torrents of mud smashedthe drinking water pipes and buried and con-taminated hundreds of wells.

A city of 300,000 inhabitants suddenlyfound itself completely without drink-able water.

The first medical consultations organizedby Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) showedan incidence of diarrhea of nearly 100 percent in certain neighbourhoods, as well asmany skin infections – extremely alarmingindicators. The residents, having no alter-native, continued to draw their water fromwells contaminated by polluted mud.

In addition to setting up an 80-bed hospitaland organizing mobile clinics to reach thearea’s most isolated inhabitants, MSF quick-ly established a major program for the treat-ment and distribution of drinking water.

Gregory VandendaelenPress officer

Photos © Gregory Vandendaelen / MSFunless otherwise noted.

Water everywhere,but not a drop to drink

Transporting water to the four corners of the city is a dailychallenge. Not a day goes by withoutone of the six MSF trucks gettingstuck in the mud. When this happens,its contents are transferred to anothertruck using a pump. Thus lightened,the truck can get moving again.

One of MSF’s 41 water supply points. This large blue envelope is a 15,000 litrewater bladder. Made of PVC, it is placed in an elevated position and filled everyday. From this, approximately 3,000 people have access to about five litres of watereach to meet their basic daily needs, including cooking, cleaning and washing. InCanada, people use on average 300 litres of water per day.

All the water distribution facilities are only temporary. Soon MSF will begin the

renovation of more than 200 existingwells. The best performing wells and

those located in the most affected areaswill be selected. Since these wells are

contaminated, it will be necessary toclean them up and repair the many

damaged pumps.

At the time this article was written, MSF estimated it could provide drinking water to one third of the inhabitants of the city of Gonaives, more than 100,000 people. This is one of the mostambitious water management projects in the history of MSF.

Flying over Gonaives, Haiti’s fourth largest city, one is struck by the sheerquantity of water still remaining in and around the area, even five weeks afterhurricanes ravaged this city in northwest Haiti in September 2008. The seastill covers much agricultural land (some of the region is below sea level), butthe Artibonite River and its many tributaries also brought torrents of muddown from the nearby mountains.

© K

lavs

Chr

iste

nsen

The quantity of mud in the streets ofthe city is such that it is estimated it

will take about 18 months and theuse of some 50 trucks working

constantly to restore the city to itsformer state. In some places, the mud

was more than two metres deep.

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1 page 7

H a i t i

In early September 2008, hurricanes Gustav, Hanna andIke ravaged Haiti.

Nearly 800 people died, and tens ofthousands were left homeless. Roads

and infrastructure were destroyed. Thelandscape in the northwestern city ofGonaives was desolate.

Before the hurricanes, the inhabitants ofGonaives had access to many wells, and anaqueduct system served certain neighbour-hoods. It took just a few hours for everythingto be destroyed. Torrents of mud smashedthe drinking water pipes and buried and con-taminated hundreds of wells.

A city of 300,000 inhabitants suddenlyfound itself completely without drink-able water.

The first medical consultations organizedby Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) showedan incidence of diarrhea of nearly 100 percent in certain neighbourhoods, as well asmany skin infections – extremely alarmingindicators. The residents, having no alter-native, continued to draw their water fromwells contaminated by polluted mud.

In addition to setting up an 80-bed hospitaland organizing mobile clinics to reach thearea’s most isolated inhabitants, MSF quick-ly established a major program for the treat-ment and distribution of drinking water.

Gregory VandendaelenPress officer

Photos © Gregory Vandendaelen / MSFunless otherwise noted.

Water everywhere,but not a drop to drink

Transporting water to the four corners of the city is a dailychallenge. Not a day goes by withoutone of the six MSF trucks gettingstuck in the mud. When this happens,its contents are transferred to anothertruck using a pump. Thus lightened,the truck can get moving again.

One of MSF’s 41 water supply points. This large blue envelope is a 15,000 litrewater bladder. Made of PVC, it is placed in an elevated position and filled everyday. From this, approximately 3,000 people have access to about five litres of watereach to meet their basic daily needs, including cooking, cleaning and washing. InCanada, people use on average 300 litres of water per day.

All the water distribution facilities are only temporary. Soon MSF will begin the

renovation of more than 200 existingwells. The best performing wells and

those located in the most affected areaswill be selected. Since these wells are

contaminated, it will be necessary toclean them up and repair the many

damaged pumps.

At the time this article was written, MSF estimated it could provide drinking water to one third of the inhabitants of the city of Gonaives, more than 100,000 people. This is one of the mostambitious water management projects in the history of MSF.

Flying over Gonaives, Haiti’s fourth largest city, one is struck by the sheerquantity of water still remaining in and around the area, even five weeks afterhurricanes ravaged this city in northwest Haiti in September 2008. The seastill covers much agricultural land (some of the region is below sea level), butthe Artibonite River and its many tributaries also brought torrents of muddown from the nearby mountains.

© K

lavs

Chr

iste

nsen

The quantity of mud in the streets ofthe city is such that it is estimated it

will take about 18 months and theuse of some 50 trucks working

constantly to restore the city to itsformer state. In some places, the mud

was more than two metres deep.

two district referral hospitals. At St.Kizito, MSF supports the only inpatienttherapeutic feeding centre in the region.Once children are stabilized at the centre,they are discharged and followed by themobile clinics closer to their homes.

In Karamoja many families cannot affordfood, let alone the right food, and must sur-vive on cereal porridges that lack essentialnutrients. Therefore MSF treats malnour-ished children with therapeutic ready-to-use food designed to match their needs.

“Here we use Plumpy’nut, two sachets forchildren of less than eight kilograms andfor children over eight kilograms, threesachets,” explains Mbaluto. “Soap andmosquito nets are provided to help withhygiene and to prevent malaria. A supplyof Plumpy’nut is given to the mothers andthey are asked to come back 10 dayslater. We have not seen many problems;rather, some good progress. Most of thechildren like the taste of the therapeuticfood and are gaining weight. It dependson the location, but we usually see about60 to 70 patients a day.”

The team is encouraging communityhealth workers to seek out malnourishedchildren by visiting families and explain-ing the services MSF is offering. “So far,the mothers are coming steadily and inmost clinics 80 to 90 per cent of thembring their children for followup visits,”Mbaluto says. “But still, in one or twoclinics, we are only seeing around 50 percent, so we have some work to do there.”

MSF believes the challenge in areas mostdevastated by malnutrition is not only totreat those most affected but also to pre-vent them from falling into the terminalstages of malnutrition in the first place,and to do so by ensuring all children haveaccess to nutrient-rich foods.

Susanne DoettlingCommunications officer

Photos © Julie Rémy

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1 page 9

In Karamoja, Uganda, malnutrition ischronic. In 2008, this remote region of

northeast Uganda began suffering itsworst drought in five years, creating ahumanitarian crisis. The last two yearssaw back-to-back dry spells followed byunusually heavy rains. Rising food pricesmake what food is available in the marketsimply unaffordable. Inadequate rain in2007 and late rains in 2008 have led tolate and insufficient planting of peanutsand sorghum. There are also rising num-bers of animal losses.

Karamoja is home to about one million peo-ple, people who are mostly dependent onanimals for their livelihoods. The region iswell known for conflicts connected to cattleraiding. Pastoral-nomadic lifestyles andinsecurity make it difficult for people toaccess the region’s few health facilities.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) opened atherapeutic feeding program for childrenunder the age of five in the worst-affecteddistricts of Moroto and Nakapiripirit. Teamsgo directly to the villages, bringing health-care to the nomads of Karamoja.

“The best way to assist and treat chil-dren, the most vulnerable, is to travelout to the villages to find the malnour-ished kids while providing them withtwo-week rations to get them through theworst,” explains Kodjo Edoh, MSF headof mission in Uganda. In Karamoja how-ever, adds Edoh, “we fear the worst isstill to come.”

The MSF nutritional intervention startedin June 2008 and was expected to runonly until September. But as ofSeptember, with almost 24,000 childrenscreened and 2,300 of them severelymalnourished, the program will continuewell into 2009.

George Mbaluto, a Kenyan nurse incharge of the program, describes how themobile clinics for the feeding program areset up: “The mothers come with theirchildren and sit together in the waitingarea. Here they are given education onnutrition and personal hygiene.”

Children between six months and fiveyears are then screened with a mid-upper

arm circumference (MUAC) bracelet.“Any child measuring between 11 and13.5 centimetres on the MUAC has hisweight and height taken,” says Mbaluto.“Those measuring less than 11 centime-tres as well as those with bilateral oede-ma [swelling due to fluid accumulation]are admitted directly as they are consid-ered to have severe malnutrition.”

Every newly admitted child is tested formalaria and screened for other medicalconditions such as infections and diar-rhea. In some areas, 60 to 90 per cent ofthe kids were found to have malaria. Twonurses do consultations, examine thechildren from head to toe and rule out anycomplications. They look for infectionsand depressed immunity. The childrenreceive vitamin A, as well as folic acid toprevent anemia. They receive antibioticsand other drugs to treat complications.

Children who are severely malnourishedwithout other medical complications willbe treated on site, while a child who isvery sick or has poor appetite is referredto St. Kizito Hospital in Matany, one of

U g a n d a

MALNUTRITION IN KARAMOJA:Pushing back against a chronic struggle

two district referral hospitals. At St.Kizito, MSF supports the only inpatienttherapeutic feeding centre in the region.Once children are stabilized at the centre,they are discharged and followed by themobile clinics closer to their homes.

In Karamoja many families cannot affordfood, let alone the right food, and must sur-vive on cereal porridges that lack essentialnutrients. Therefore MSF treats malnour-ished children with therapeutic ready-to-use food designed to match their needs.

“Here we use Plumpy’nut, two sachets forchildren of less than eight kilograms andfor children over eight kilograms, threesachets,” explains Mbaluto. “Soap andmosquito nets are provided to help withhygiene and to prevent malaria. A supplyof Plumpy’nut is given to the mothers andthey are asked to come back 10 dayslater. We have not seen many problems;rather, some good progress. Most of thechildren like the taste of the therapeuticfood and are gaining weight. It dependson the location, but we usually see about60 to 70 patients a day.”

The team is encouraging communityhealth workers to seek out malnourishedchildren by visiting families and explain-ing the services MSF is offering. “So far,the mothers are coming steadily and inmost clinics 80 to 90 per cent of thembring their children for followup visits,”Mbaluto says. “But still, in one or twoclinics, we are only seeing around 50 percent, so we have some work to do there.”

MSF believes the challenge in areas mostdevastated by malnutrition is not only totreat those most affected but also to pre-vent them from falling into the terminalstages of malnutrition in the first place,and to do so by ensuring all children haveaccess to nutrient-rich foods.

Susanne DoettlingCommunications officer

Photos © Julie Rémy

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1 page 9

In Karamoja, Uganda, malnutrition ischronic. In 2008, this remote region of

northeast Uganda began suffering itsworst drought in five years, creating ahumanitarian crisis. The last two yearssaw back-to-back dry spells followed byunusually heavy rains. Rising food pricesmake what food is available in the marketsimply unaffordable. Inadequate rain in2007 and late rains in 2008 have led tolate and insufficient planting of peanutsand sorghum. There are also rising num-bers of animal losses.

Karamoja is home to about one million peo-ple, people who are mostly dependent onanimals for their livelihoods. The region iswell known for conflicts connected to cattleraiding. Pastoral-nomadic lifestyles andinsecurity make it difficult for people toaccess the region’s few health facilities.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) opened atherapeutic feeding program for childrenunder the age of five in the worst-affecteddistricts of Moroto and Nakapiripirit. Teamsgo directly to the villages, bringing health-care to the nomads of Karamoja.

“The best way to assist and treat chil-dren, the most vulnerable, is to travelout to the villages to find the malnour-ished kids while providing them withtwo-week rations to get them through theworst,” explains Kodjo Edoh, MSF headof mission in Uganda. In Karamoja how-ever, adds Edoh, “we fear the worst isstill to come.”

The MSF nutritional intervention startedin June 2008 and was expected to runonly until September. But as ofSeptember, with almost 24,000 childrenscreened and 2,300 of them severelymalnourished, the program will continuewell into 2009.

George Mbaluto, a Kenyan nurse incharge of the program, describes how themobile clinics for the feeding program areset up: “The mothers come with theirchildren and sit together in the waitingarea. Here they are given education onnutrition and personal hygiene.”

Children between six months and fiveyears are then screened with a mid-upper

arm circumference (MUAC) bracelet.“Any child measuring between 11 and13.5 centimetres on the MUAC has hisweight and height taken,” says Mbaluto.“Those measuring less than 11 centime-tres as well as those with bilateral oede-ma [swelling due to fluid accumulation]are admitted directly as they are consid-ered to have severe malnutrition.”

Every newly admitted child is tested formalaria and screened for other medicalconditions such as infections and diar-rhea. In some areas, 60 to 90 per cent ofthe kids were found to have malaria. Twonurses do consultations, examine thechildren from head to toe and rule out anycomplications. They look for infectionsand depressed immunity. The childrenreceive vitamin A, as well as folic acid toprevent anemia. They receive antibioticsand other drugs to treat complications.

Children who are severely malnourishedwithout other medical complications willbe treated on site, while a child who isvery sick or has poor appetite is referredto St. Kizito Hospital in Matany, one of

U g a n d a

MALNUTRITION IN KARAMOJA:Pushing back against a chronic struggle

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1 page 11

For several years Médecins SansFrontières (MSF) teams in Pakistan

have been running clinics and health cen-tres in the regions bordering Afghanistan,where insecurity has had a serious impacton healthcare. But it has become clearthat in other rural areas in Pakistan manypeople are finding it hard or impossible toget medical treatment they can afford.This is particularly true of easternBalochistan province, where people’shealthcare needs are some of the mostneglected in the country.

Life here is harsh, with cold winters anddry, blistering hot summers. There aresteep barren mountains in the north ofthe province and desert plains in thesouth that slope down to the Indus valley.

“We have been trying to work in eastBalochistan on a permanent basis for several years now,” says Chris Lockyear,MSF’s head of mission in Pakistan. “Our new program in Jaffarabad districthopes to address some of the very great needs.”

In June 2007, cyclone Yemyin broughtwidespread flooding to Balochistan. MSFphysician Ahmed Bilal describes theemergency response:

“We started working in an area that wasvery hard to reach, and when we got therewe saw how terrible the conditions were.Whole villages were destroyed. We startedup treatment centres under the open sky.We treated about 3,000 people in twoweeks. When we heard that in one areachildren were dying of diarrhea, we veryquickly did some rapid tests, which con-firmed it was cholera. The MSF base inIslamabad immediately sent downcholera kits and logistical materials andwe set up six cholera treatment centres.We treated more than 300 children.Before our arrival four children had diedof cholera, but after we set up the treat-ment centres there were no deaths.”

“I remember the conditions being very, verybad – nothing to drink, nothing to eat. Wecovered the whole of that difficult area andthe regional officials really appreciated the

work of MSF – they said that MSF was righton the frontline, the first to get there inthese terrible conditions.”

Working in the floods, Bilal and histeam saw how bad the general healthsituation is here. He has been workingwith MSF for more than three years, inmany places, and he believes eastBalochistan is an area in great need.The land is some of the richest inBalochistan, but most of it is owned bylandlords and the majority of peoplework as daily labourers.

“They often cannot pay for good food forthemselves or their children,” explainsBilal. “The mothers are often very mal-nourished and when they are breastfeed-ing, they have no proper food to give theirbabies,” he adds. “And sewage gets intothe drinking water channels, which peo-ple are using for drinking, for cooking, foreverything. The number of cases of diar-rhea, typhoid and hepatitis is very highand when they get diarrhea, the childrenquickly become malnourished.”

In July of 2008 MSF did a rapid nutri-tional survey and found high rates of mal-nutrition in the district. It was agreed withthe authorities that MSF should start anutrition program.

“We are working in the main regional hos-pital, an old 40-bed hospital built in1944,” says Bilal. “It is in very bad con-dition, and we have been offered a sepa-rate ward we are repairing. It is alwaysbusy and people come from far away,from all over the region. They know thereare new doctors in the hospital, ‘doctorsfor weak children’ they call us.”

The MSF team is seeing increasingnumbers of patients. One of the biggestchallenges is making sure patients con-tinue their treatment after the first visitto the hospital. Outreach workers visitpatients at home because some peoplefind it hard to come back for check-upsand to collect their next ration of thera-peutic food.

People are so poor they cannot pay fortransportation to the health clinic.Ninety per cent of mothers in the area

work as day labourers, mostly in thebrick kilns or in the rice fields. Theyhave to work up to 10 hours, in temper-atures up to 50 C in July, and if they donot work a full day they do not get paid.“So it is very hard for them to find thetime to come to the hospital,” explainsMSF staff Aleem Shah. “They want tocome, and they do come when they can,but often it is simply impossible so weneed to go out to their homes.”

Gaining acceptance is also a challengewhen working in a new area. Shah recallsa mother who brought in her two-year-oldboy from a long way away by donkey cart.Her toddler had vitamin A deficiency,probably since birth, and was blind. Hewas severely malnourished so MSF gavehim special therapeutic food rich in vita-mins and minerals. The mother hadbrought her child alone on the first visit,but when she brought him back for acheck up, her mother and mother-in-lawcame along. The boy was doing much bet-ter, and they all had tears in their eyes.They explained he used to just lie therelimply, but now he was more active, show-ing signs of liveliness.

“I saw tears of joy and happiness runningdown the mother’s face,” says Shah.“This is the best thing, better than words,and it makes me feel what we are doing isreally worthwhile.” After this family wentback to their village, MSF had 30 morepatients from the same area, a sign thatMSF’s medical services are becomingbetter known.

Now that the therapeutic feeding centreis fully up and running, MSF hopes toexpand its medical programs in theregion. Tuberculosis is common, as ishepatitis. People’s general health statusis poor. There is little public health edu-cation. Maternal mortality is high, in partbecause life-saving caesarean sectionsare not available to women with deliverycomplications. The nearest referral hospi-tal is 200 kilometres away, but people aretoo poor to get there. “Healthcare in thisarea is completely neglected,” says Bilal.“For the people here, I think there is agreat need for MSF to do more.”

Robin MeldrumCommunications officer

P a k i s t a n

MEETING HEALTHCARE NEEDSamid mountains and desert

© M

SF

© T

on K

oene

/ M

SF

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1 page 11

For several years Médecins SansFrontières (MSF) teams in Pakistan

have been running clinics and health cen-tres in the regions bordering Afghanistan,where insecurity has had a serious impacton healthcare. But it has become clearthat in other rural areas in Pakistan manypeople are finding it hard or impossible toget medical treatment they can afford.This is particularly true of easternBalochistan province, where people’shealthcare needs are some of the mostneglected in the country.

Life here is harsh, with cold winters anddry, blistering hot summers. There aresteep barren mountains in the north ofthe province and desert plains in thesouth that slope down to the Indus valley.

“We have been trying to work in eastBalochistan on a permanent basis for several years now,” says Chris Lockyear,MSF’s head of mission in Pakistan. “Our new program in Jaffarabad districthopes to address some of the very great needs.”

In June 2007, cyclone Yemyin broughtwidespread flooding to Balochistan. MSFphysician Ahmed Bilal describes theemergency response:

“We started working in an area that wasvery hard to reach, and when we got therewe saw how terrible the conditions were.Whole villages were destroyed. We startedup treatment centres under the open sky.We treated about 3,000 people in twoweeks. When we heard that in one areachildren were dying of diarrhea, we veryquickly did some rapid tests, which con-firmed it was cholera. The MSF base inIslamabad immediately sent downcholera kits and logistical materials andwe set up six cholera treatment centres.We treated more than 300 children.Before our arrival four children had diedof cholera, but after we set up the treat-ment centres there were no deaths.”

“I remember the conditions being very, verybad – nothing to drink, nothing to eat. Wecovered the whole of that difficult area andthe regional officials really appreciated the

work of MSF – they said that MSF was righton the frontline, the first to get there inthese terrible conditions.”

Working in the floods, Bilal and histeam saw how bad the general healthsituation is here. He has been workingwith MSF for more than three years, inmany places, and he believes eastBalochistan is an area in great need.The land is some of the richest inBalochistan, but most of it is owned bylandlords and the majority of peoplework as daily labourers.

“They often cannot pay for good food forthemselves or their children,” explainsBilal. “The mothers are often very mal-nourished and when they are breastfeed-ing, they have no proper food to give theirbabies,” he adds. “And sewage gets intothe drinking water channels, which peo-ple are using for drinking, for cooking, foreverything. The number of cases of diar-rhea, typhoid and hepatitis is very highand when they get diarrhea, the childrenquickly become malnourished.”

In July of 2008 MSF did a rapid nutri-tional survey and found high rates of mal-nutrition in the district. It was agreed withthe authorities that MSF should start anutrition program.

“We are working in the main regional hos-pital, an old 40-bed hospital built in1944,” says Bilal. “It is in very bad con-dition, and we have been offered a sepa-rate ward we are repairing. It is alwaysbusy and people come from far away,from all over the region. They know thereare new doctors in the hospital, ‘doctorsfor weak children’ they call us.”

The MSF team is seeing increasingnumbers of patients. One of the biggestchallenges is making sure patients con-tinue their treatment after the first visitto the hospital. Outreach workers visitpatients at home because some peoplefind it hard to come back for check-upsand to collect their next ration of thera-peutic food.

People are so poor they cannot pay fortransportation to the health clinic.Ninety per cent of mothers in the area

work as day labourers, mostly in thebrick kilns or in the rice fields. Theyhave to work up to 10 hours, in temper-atures up to 50 C in July, and if they donot work a full day they do not get paid.“So it is very hard for them to find thetime to come to the hospital,” explainsMSF staff Aleem Shah. “They want tocome, and they do come when they can,but often it is simply impossible so weneed to go out to their homes.”

Gaining acceptance is also a challengewhen working in a new area. Shah recallsa mother who brought in her two-year-oldboy from a long way away by donkey cart.Her toddler had vitamin A deficiency,probably since birth, and was blind. Hewas severely malnourished so MSF gavehim special therapeutic food rich in vita-mins and minerals. The mother hadbrought her child alone on the first visit,but when she brought him back for acheck up, her mother and mother-in-lawcame along. The boy was doing much bet-ter, and they all had tears in their eyes.They explained he used to just lie therelimply, but now he was more active, show-ing signs of liveliness.

“I saw tears of joy and happiness runningdown the mother’s face,” says Shah.“This is the best thing, better than words,and it makes me feel what we are doing isreally worthwhile.” After this family wentback to their village, MSF had 30 morepatients from the same area, a sign thatMSF’s medical services are becomingbetter known.

Now that the therapeutic feeding centreis fully up and running, MSF hopes toexpand its medical programs in theregion. Tuberculosis is common, as ishepatitis. People’s general health statusis poor. There is little public health edu-cation. Maternal mortality is high, in partbecause life-saving caesarean sectionsare not available to women with deliverycomplications. The nearest referral hospi-tal is 200 kilometres away, but people aretoo poor to get there. “Healthcare in thisarea is completely neglected,” says Bilal.“For the people here, I think there is agreat need for MSF to do more.”

Robin MeldrumCommunications officer

P a k i s t a n

MEETING HEALTHCARE NEEDSamid mountains and desert

© M

SF

© T

on K

oene

/ M

SF

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1 page 13

Imagine, you have 3 minutes to gather yourfamily and flee.

This is what people in Winnipeg,Edmonton, Calgary and Vancouver were

asked to do in September and October of2008 when Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)brought to their city a travelling exhibit calledA Refugee Camp in the Heart of the City. Theexhibit was a reconstruction of a refugeecamp, where MSF field workers shared first-hand knowledge of the living conditions ofthe 42 million people around the world dis-placed by conflict. As they toured the differ-ent areas of the camp 15,000 visitors had toask themselves: Where will I find shelter?How will I feed my family? How will I getmedical care for my children?

As a tour guide, it was an honour for me torepresent the voices of people I worked within Sudan and Bangladesh. They would havebeen so pleased to know their stories werebeing heard on the other side of the worldhere in Canada. Our Canadian image is diffi-cult to define, but the people I have workedwith in other countries see us as diverse,humble, fair and respectful of people regard-less of their situation.

After returning from Darfur, Sudan in thespring of 2008, I was numb to the suffer-ing I had witnessed. It is difficult to talkabout because the context is so hard todescribe. Issues such as humanitariancrises are strange to slip into a dinner tableconversation or daily interactions with peo-ple. Although I think about the people inSudan every day, I rarely discuss them.

Many Canadians already have a difficulttime understanding what it is like to livewithout secure access to water, sanitation,or basic healthcare. My weak verbaldescriptions seem to cheapen the powerfulrepresentation the 42 million refugees andinternally displaced people deserve.

The Refugee Camp in the Heart of the Citywas a perfect tool for explaining the situationstep by step, discussing the issues, thenspeaking with the tour group about the chal-lenges and how they’re met, by MSF as wellas the refugees themselves. It was amazingto see school groups – kids as young as eightyears old – show interest, ask questions, andbe motivated to learn more. Visitors to theexhibit were able to see how their awarenessand desire for action – average Canadianswanting to make a difference – can support

refugees and displaced people struggling tosurvive. Activities like A Refugee Camp inthe Heart of the City encourage the public tobecome aware and hold international powersaccountable to their responsibilities.

During the four weeks I travelled with theexhibit, I guided about 80 tours. I expect-ed I would get bored with the redundan-cy, but the participants on the tour askedmany thoughtful questions and oftenshared with the group their knowledge,including sometimes their own experi-ences as refugees.

While at the nutrition station with a Grade 4class on one tour, we were discussing howchallenging it is to treat severely malnour-ished children. Mothers and care-givers havea difficult time staying motivated to re-feed

the patients because these children appearso hopeless and close to death. Family mem-bers may be tempted to give the therapeuticfood to their other children who do notappear to have such a seemingly grim fate.

However, severely malnourished childrenhave an excellent recovery rate. One nine-year-old student on the tour asked what I didto keep the mothers motivated. I answered itwas not me who kept the mothers motivatedbut one of the local Sudanese MSF employ-ees named Abdul. I was describing thegames he played with the toddlers – havingthem deliver the therapeutic food to the bedsof the younger kids. While mentioning hisother inspirational interventions my eyesfilled with tears and my lips started to quiver.I sent the students to the cholera station, thenext area of the tour, to avoid my emotional

scene. Perhaps I am not as numb to the sit-uation as I thought I was.

Some westerners think poverty in thedeveloping world is the reality of the peo-ple there and they do not suffer as muchas we would in the same situation. Ofcourse, nothing could be further from thetruth. Abdul’s story is one that needs thecontext of a Refugee Camp exhibit for peo-ple to understand how the fundamentalhuman act of caring makes a difference.

Kevin BarlowRegistered nurse

Photos © linda o. nagy / MSF

M S F i n C a n a d a

15,000 COME TO REFUGEE CAMP IN THE HEART OF THE CITY

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1 page 13

Imagine, you have 3 minutes to gather yourfamily and flee.

This is what people in Winnipeg,Edmonton, Calgary and Vancouver were

asked to do in September and October of2008 when Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)brought to their city a travelling exhibit calledA Refugee Camp in the Heart of the City. Theexhibit was a reconstruction of a refugeecamp, where MSF field workers shared first-hand knowledge of the living conditions ofthe 42 million people around the world dis-placed by conflict. As they toured the differ-ent areas of the camp 15,000 visitors had toask themselves: Where will I find shelter?How will I feed my family? How will I getmedical care for my children?

As a tour guide, it was an honour for me torepresent the voices of people I worked within Sudan and Bangladesh. They would havebeen so pleased to know their stories werebeing heard on the other side of the worldhere in Canada. Our Canadian image is diffi-cult to define, but the people I have workedwith in other countries see us as diverse,humble, fair and respectful of people regard-less of their situation.

After returning from Darfur, Sudan in thespring of 2008, I was numb to the suffer-ing I had witnessed. It is difficult to talkabout because the context is so hard todescribe. Issues such as humanitariancrises are strange to slip into a dinner tableconversation or daily interactions with peo-ple. Although I think about the people inSudan every day, I rarely discuss them.

Many Canadians already have a difficulttime understanding what it is like to livewithout secure access to water, sanitation,or basic healthcare. My weak verbaldescriptions seem to cheapen the powerfulrepresentation the 42 million refugees andinternally displaced people deserve.

The Refugee Camp in the Heart of the Citywas a perfect tool for explaining the situationstep by step, discussing the issues, thenspeaking with the tour group about the chal-lenges and how they’re met, by MSF as wellas the refugees themselves. It was amazingto see school groups – kids as young as eightyears old – show interest, ask questions, andbe motivated to learn more. Visitors to theexhibit were able to see how their awarenessand desire for action – average Canadianswanting to make a difference – can support

refugees and displaced people struggling tosurvive. Activities like A Refugee Camp inthe Heart of the City encourage the public tobecome aware and hold international powersaccountable to their responsibilities.

During the four weeks I travelled with theexhibit, I guided about 80 tours. I expect-ed I would get bored with the redundan-cy, but the participants on the tour askedmany thoughtful questions and oftenshared with the group their knowledge,including sometimes their own experi-ences as refugees.

While at the nutrition station with a Grade 4class on one tour, we were discussing howchallenging it is to treat severely malnour-ished children. Mothers and care-givers havea difficult time staying motivated to re-feed

the patients because these children appearso hopeless and close to death. Family mem-bers may be tempted to give the therapeuticfood to their other children who do notappear to have such a seemingly grim fate.

However, severely malnourished childrenhave an excellent recovery rate. One nine-year-old student on the tour asked what I didto keep the mothers motivated. I answered itwas not me who kept the mothers motivatedbut one of the local Sudanese MSF employ-ees named Abdul. I was describing thegames he played with the toddlers – havingthem deliver the therapeutic food to the bedsof the younger kids. While mentioning hisother inspirational interventions my eyesfilled with tears and my lips started to quiver.I sent the students to the cholera station, thenext area of the tour, to avoid my emotional

scene. Perhaps I am not as numb to the sit-uation as I thought I was.

Some westerners think poverty in thedeveloping world is the reality of the peo-ple there and they do not suffer as muchas we would in the same situation. Ofcourse, nothing could be further from thetruth. Abdul’s story is one that needs thecontext of a Refugee Camp exhibit for peo-ple to understand how the fundamentalhuman act of caring makes a difference.

Kevin BarlowRegistered nurse

Photos © linda o. nagy / MSF

M S F i n C a n a d a

15,000 COME TO REFUGEE CAMP IN THE HEART OF THE CITY

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1

BANGLADESHGrant Assenheimer Oakville, ON Logistician

BURUNDIJoel Montanez Moncton, NB Mental health specialist

CAMEROONSerge Kaboré Québec, QC Medical coordinatorRobert Parker Québec, QC Project coordinator

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLICPatrick Boucher Montréal, QC LogisticianDuncan Coady Pinawa, MB Financial coordinatorEdith Fortier Montréal, QC Project coordinatorMélanie Lachance Poisson

Québec, QC NurseMireille Roy Montréal, QC Laboratory technicianRachel Seguin Montréal, QC Nurse

CHADNicolas Berubé Montréal, QC LogisticianIvan Gayton Vancouver, BC Project coordinatorGuylaine Houle Montréal, QC LogisticianJean-Marc Kuyper Montréal, QC LogisticianAudra Renyi Toronto, ON LogisticianSonya Sagan Binbrook, ON LogisticianMatthew Schrader Massey, ON LogisticianLuke Shankland Montréal, QC Project coordinator

CHINAPeter Saranchuk St. Catharines, ON Doctor

COLOMBIAMartin Girard Montréal, QC Project coordinator

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGOMélanie Bergeron Sherbrooke, QC Liaison officerMarie-Ève Bilodeau Ottawa, ON Training officerOwen Campbell Montréal, QC LogisticianAnnie Désilets Ottawa, ON Emergency coordinatorElias Frédéric Montréal, QC LogisticianElizabeth Kavouris Vancouver, BC NursePierre Langlois

Sainte-Catherine-de-Hatley, QC AdministratorTara Newell London, ON Project coordinatorJean-François Nouveaux Montréal, QC LogisticianNadia Perreault Mascouches, QC NurseDenis Roy Montréal, QC Mental health specialistJoannie Roy Verdun QC Laboratory technicianSylvie Savard Hull, QC Financial coordinator

ETHIOPIAJustin Armstrong Haileybury, ON Project coordinatorVanessa Bailey Victoria, BC NurseStephanie Gee Vancouver, BC NurseDoris Gonzalez-Fernandez Montréal, QC DoctorRalph Heeschen Ajax, ON LogisticianAnneMarie Pegg Yellowknife, NT DoctorDominique Proteau Québec, QC Project coordinatorJonathon Rasenberg Flinton, ON LogisticianChristophe Rouy Québec, QC Logistician

HAITICharmaine Brett Ottawa, ON Human resources officerAnnie Dallaire Montréal, QC Financial coordinatorWendy Lai Toronto, ON DoctorPatrick Laurent

Montréal, QC Water and sanitation specialistMonic Lessard Montréal, QC AdministratorElaine Sansoucy Saint-Hyacinthe, QC NurseKevin Tokar Ottawa, ON Logistician

INDIAJudy Adams Miramichi, NB Mental health specialist

KENYAIndu Gambhir Ottawa, ON Project coordinatorMaguil Gouja Montréal, QC Financial coordinator

MOZAMBIQUEIsabelle Casavant Montréal, QC Nurse

MYANMARLeah Battersby Whitehorse, YT LogisticianMatthew Calvert Ottawa, ON LogisticianFrédéric Dubé Québec, QC LogisticianMathieu Léonard Sherbrooke, QC LogisticianLori Wanlin Winnipeg, MB Logistician

NIGERMaude Bernard Montréal, QC NurseJosé Godbout Blainville, QC Project coordinatorAudrey St-Arnaud Blainville, QC Nurse

NIGERIASharon Janzen Vancouver, BC Nurse

PAKISTANFrank Boyce Belleville, ON DoctorGabriele Pahl Kingsville, ON Medical coordinator

PAPUA NEW GUINEAViolet Baron Cochrane, AB Financial coordinatorMaryse Bonnel Morin Heights, QC NurseShannon Lee Fredericton, NB Project coordinatorJulia Payson Vernon, BC Project coordinatorAlanna Shwetz Smiths Falls, ON Nurse

SOMALIALori Beaulieu Prince George, BC AdministratorNancy Dale Toronto, ON NurseLuis Neira Montréal, QC Medical coordinatorJames Squier Saltspring Island, BC Logistician

SOUTH AFRICACheryl McDermid Vancouver, BC Doctor

SRI LANKAJohn Crosbie Toronto, ON Logistician

SUDANReshma Adatia Vancouver, BC CoordinatorLaura Archer Westmount, QC Nurse

Daniel Arnold Vancouver, BC LogisticianLeanna Hutchins Canmore, AB LogisticianVictoria Kennedy Toronto, ON NurseSarah Lamb Toronto, ON LogisticianRink De Lange Sainte-Cécile-de-Masham, QC

Water and sanitation specialistLeanne Olsen Sainte-Cécile-de-Masham, QC NurseJennie Partridge Canmore, AB NurseKerri Ramstead Brandon, MB NurseGrace Tang Toronto, ON Project coordinator

TURKMENISTANSharla Bonneville Toronto, ON Logistician

UZBEKISTANAda Yee Calgary, AB Financial coordinator

page 15

In the tenuous border area between thenorth and south of Sudan sits Abyei, a

town of 60,000. Oil and the sharing ofwealth in Sudan played a huge role in a21-year conflict that only ended in2005. It is anyone’s guess whether aplanned referendum to determine sepa-ration of the south will ever come topass. Abyei, always at risk for renewedhostility, was virtually destroyed in May2008 during attacks. At that timeMédecins Sans Frontières (MSF), whichhas been there since 2006, was treating700 children for malnutrition.

The suddenness and devastation of thatattack underscores the work of MSF andthe vital need for that work to continue.While the place of Abyei can be erased,the truth of it – that it existed, that thepeople there truly lived and breathed – ismore deeply etched in the fabric ofhuman consciousness by the penetratingand incisive depictions in Toronto physi-cian James Maskalyk’s highly acclaimedblog, “Suddenly...Sudan.” Maskalykwrote the blog from February to July of2007, while working in Abyei on his firstmission with MSF. Through his blog andhis forthcoming book, Six Months inSudan, due out in April 2009, Abyei andall of its heartbeats will continue to per-sist inside of us.

Maskalyk’s quest seemed to be to createtime and place travel so that no matterwhere they were, anyone reading wouldbe present in the moments he wasrecounting – “That boy, the one whosebone we drilled into with a hypodermiccannula, the one who I used as an exam-ple of our small therapeutic successes,the one who came to life after lying dry,drooping in his mother’s arms, he died. Iwas told the next day. The cannula hadstopped working, but he was drinking.An hour later, when the nurse next wentto check, he was dead. A husk.

“Diarrhea is a killer. I see it nearlyevery day. It kills children, turns themto husks. The work it takes to keep theirmachinery turning with the desert out-side and one inside, is simply toomuch. They cave in, exhausted, andcreak to a stop.”

Throughout the months of writing,Maskalyk’s blog embodied the meaningof témoignage, or bearing witness. Heforces us to breathe the faint breaths ofthe helpless, brushes their skin upagainst our own, and draws our gaze intothe soft eyes of those who smile as wesmile, cry as we cry. Victories are oneheartbeat at a time. Deaths, the same.Maskalyk’s témoignage teaches us to

give in, to let go and simply be – with thetwo-year-old abandoned near a tree byhis family, with the young woman suffer-ing from TB who walked for days to getto the clinic to deliver a premature baby“no bigger than a bird,” with the wait-ing, the laughing, the silent. Many readhis blog – professionals, students,thinkers, family. They all got it. Theyunderstood. As one person put it, “I amgrateful for your images and words butsometimes they twist inside my heart.”

The original blog:www.msf.ca/blogs/JamesM.php

The forthcoming book: www.randomhouse.ca

Calvin WhiteMental health counsellor

Calvin White is a mental healthcounsellor and writer who lives inSalmon Arm, British Columbia. In2009 he plans to leave on his firstmission with MSF, as a mentalhealth officer.

DispatchesMédecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders

720 Spadina Ave., Suite 402 Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2T9Tel: 416.964.0619Fax: 416.963.8707Toll free: 1.800.982.7903Email: [email protected]

Editor:linda o. nagy

Editorial director:Avril Benoît

Translation coordinator:Julie Rémy

Contributors:Kevin BarlowSusanne DoettlingRobin MeldrumTara NewellGregory VandendaelenCalvin White

Circulation: 83,000Layout: Tenzing CommunicationsPrinting: Warren’s Imaging and Dryography

Winter 2009

ISSN 1484-9372

M S F r e a d s C a n a d i a n s o n m i s s i o n

Suddenly… a book

© J

ames

Mas

kaly

k

Dispatches Vol.11, Ed.1

BANGLADESHGrant Assenheimer Oakville, ON Logistician

BURUNDIJoel Montanez Moncton, NB Mental health specialist

CAMEROONSerge Kaboré Québec, QC Medical coordinatorRobert Parker Québec, QC Project coordinator

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLICPatrick Boucher Montréal, QC LogisticianDuncan Coady Pinawa, MB Financial coordinatorEdith Fortier Montréal, QC Project coordinatorMélanie Lachance Poisson

Québec, QC NurseMireille Roy Montréal, QC Laboratory technicianRachel Seguin Montréal, QC Nurse

CHADNicolas Berubé Montréal, QC LogisticianIvan Gayton Vancouver, BC Project coordinatorGuylaine Houle Montréal, QC LogisticianJean-Marc Kuyper Montréal, QC LogisticianAudra Renyi Toronto, ON LogisticianSonya Sagan Binbrook, ON LogisticianMatthew Schrader Massey, ON LogisticianLuke Shankland Montréal, QC Project coordinator

CHINAPeter Saranchuk St. Catharines, ON Doctor

COLOMBIAMartin Girard Montréal, QC Project coordinator

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGOMélanie Bergeron Sherbrooke, QC Liaison officerMarie-Ève Bilodeau Ottawa, ON Training officerOwen Campbell Montréal, QC LogisticianAnnie Désilets Ottawa, ON Emergency coordinatorElias Frédéric Montréal, QC LogisticianElizabeth Kavouris Vancouver, BC NursePierre Langlois

Sainte-Catherine-de-Hatley, QC AdministratorTara Newell London, ON Project coordinatorJean-François Nouveaux Montréal, QC LogisticianNadia Perreault Mascouches, QC NurseDenis Roy Montréal, QC Mental health specialistJoannie Roy Verdun QC Laboratory technicianSylvie Savard Hull, QC Financial coordinator

ETHIOPIAJustin Armstrong Haileybury, ON Project coordinatorVanessa Bailey Victoria, BC NurseStephanie Gee Vancouver, BC NurseDoris Gonzalez-Fernandez Montréal, QC DoctorRalph Heeschen Ajax, ON LogisticianAnneMarie Pegg Yellowknife, NT DoctorDominique Proteau Québec, QC Project coordinatorJonathon Rasenberg Flinton, ON LogisticianChristophe Rouy Québec, QC Logistician

HAITICharmaine Brett Ottawa, ON Human resources officerAnnie Dallaire Montréal, QC Financial coordinatorWendy Lai Toronto, ON DoctorPatrick Laurent

Montréal, QC Water and sanitation specialistMonic Lessard Montréal, QC AdministratorElaine Sansoucy Saint-Hyacinthe, QC NurseKevin Tokar Ottawa, ON Logistician

INDIAJudy Adams Miramichi, NB Mental health specialist

KENYAIndu Gambhir Ottawa, ON Project coordinatorMaguil Gouja Montréal, QC Financial coordinator

MOZAMBIQUEIsabelle Casavant Montréal, QC Nurse

MYANMARLeah Battersby Whitehorse, YT LogisticianMatthew Calvert Ottawa, ON LogisticianFrédéric Dubé Québec, QC LogisticianMathieu Léonard Sherbrooke, QC LogisticianLori Wanlin Winnipeg, MB Logistician

NIGERMaude Bernard Montréal, QC NurseJosé Godbout Blainville, QC Project coordinatorAudrey St-Arnaud Blainville, QC Nurse

NIGERIASharon Janzen Vancouver, BC Nurse

PAKISTANFrank Boyce Belleville, ON DoctorGabriele Pahl Kingsville, ON Medical coordinator

PAPUA NEW GUINEAViolet Baron Cochrane, AB Financial coordinatorMaryse Bonnel Morin Heights, QC NurseShannon Lee Fredericton, NB Project coordinatorJulia Payson Vernon, BC Project coordinatorAlanna Shwetz Smiths Falls, ON Nurse

SOMALIALori Beaulieu Prince George, BC AdministratorNancy Dale Toronto, ON NurseLuis Neira Montréal, QC Medical coordinatorJames Squier Saltspring Island, BC Logistician

SOUTH AFRICACheryl McDermid Vancouver, BC Doctor

SRI LANKAJohn Crosbie Toronto, ON Logistician

SUDANReshma Adatia Vancouver, BC CoordinatorLaura Archer Westmount, QC Nurse

Daniel Arnold Vancouver, BC LogisticianLeanna Hutchins Canmore, AB LogisticianVictoria Kennedy Toronto, ON NurseSarah Lamb Toronto, ON LogisticianRink De Lange Sainte-Cécile-de-Masham, QC

Water and sanitation specialistLeanne Olsen Sainte-Cécile-de-Masham, QC NurseJennie Partridge Canmore, AB NurseKerri Ramstead Brandon, MB NurseGrace Tang Toronto, ON Project coordinator

TURKMENISTANSharla Bonneville Toronto, ON Logistician

UZBEKISTANAda Yee Calgary, AB Financial coordinator

page 15

In the tenuous border area between thenorth and south of Sudan sits Abyei, a

town of 60,000. Oil and the sharing ofwealth in Sudan played a huge role in a21-year conflict that only ended in2005. It is anyone’s guess whether aplanned referendum to determine sepa-ration of the south will ever come topass. Abyei, always at risk for renewedhostility, was virtually destroyed in May2008 during attacks. At that timeMédecins Sans Frontières (MSF), whichhas been there since 2006, was treating700 children for malnutrition.

The suddenness and devastation of thatattack underscores the work of MSF andthe vital need for that work to continue.While the place of Abyei can be erased,the truth of it – that it existed, that thepeople there truly lived and breathed – ismore deeply etched in the fabric ofhuman consciousness by the penetratingand incisive depictions in Toronto physi-cian James Maskalyk’s highly acclaimedblog, “Suddenly...Sudan.” Maskalykwrote the blog from February to July of2007, while working in Abyei on his firstmission with MSF. Through his blog andhis forthcoming book, Six Months inSudan, due out in April 2009, Abyei andall of its heartbeats will continue to per-sist inside of us.

Maskalyk’s quest seemed to be to createtime and place travel so that no matterwhere they were, anyone reading wouldbe present in the moments he wasrecounting – “That boy, the one whosebone we drilled into with a hypodermiccannula, the one who I used as an exam-ple of our small therapeutic successes,the one who came to life after lying dry,drooping in his mother’s arms, he died. Iwas told the next day. The cannula hadstopped working, but he was drinking.An hour later, when the nurse next wentto check, he was dead. A husk.

“Diarrhea is a killer. I see it nearlyevery day. It kills children, turns themto husks. The work it takes to keep theirmachinery turning with the desert out-side and one inside, is simply toomuch. They cave in, exhausted, andcreak to a stop.”