Dispatches (Winter 2010)

-

Upload

doctors-without-borders-medecins-sans-frontieres-msf-canada -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Dispatches (Winter 2010)

MSF CANADA MAGAZINE Volume 12 Edition 1

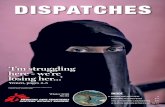

DISPATCHES

INGUSHETIA: Hope for peace gives way to despair in Ingushetia, p. 02SOMALIA: Around-the-clock healthcare saves lives, p. 04 | YEMEN: War surgery: balancing risk & immense needs, p. 06

ASIA-PACIFIC: Emergency relief for survivors of floods and quake, p. 08CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC: Sleeping sickness makes a deadly comeback, p. 12

DespairHope for peace gives way to

in ingushetia

With the sharp deterioration of the security situation in Ingushetia, people continue to live in fear for their safety and that of their fami-lies in this part of the Russian Fed-eration. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is one of the few aid organi-zations continuing to work in the republic and witnessing the severe impact violence is having on the people whose suffering goes large-ly unnoticed.

Ingushetia, a small republic in the North Caucasus bordering Chech-nya, once housed more than 140,000

displaced Chechens who between 1999 and 2003 fled what is referred to as the second Chechen war. There are still an estimated 18,000 internally displaced people in the republic, many living in precarious conditions. But the situation of the local population is not much bet-

ter. There are few natural resources and unemployment is around 70 per cent. Over the last two years, the situation has deteriorated further, with Ingushetia be-coming one of the most violent areas in the Russian Federation.

“I’m afraid to go out in the street, I’m afraid of the soldiers, of the military ve-hicles,” says 10-year-old Louisa. “My uncle was killed by the military recently, it was before my eyes. I miss him. He was very kind to me. When I’m on the way to school I just pray to God there are no military on my way.”

People tend to limit themselves to staying at home as much as possible. There’s no war going on, but people lack security – every day the small republic is shaken by explosions, shootings, attacks. More than 170 people were killed in 2008 and almost 200 between January and Oc-

tober of 2009. The constant feeling of stress and anxiety draws many people into depression.

“It was a usual morning,” says Zarema, a 24-year-old woman and MSF client, telling her own story. “My husband left for work. I made my pregnancy test, and suddenly – the result was positive. We had wanted a child so much. We had been trying for two years! I called my husband to tell him the good news, but he didn’t answer the phone.”

“I thought he was driving,” continues Zarema. “But then the people started gathering near our house. They told me the news: he had been blown up in his car. I can’t remember what happened next. I woke up in the hospital.”

“Every day emergency hospitals in In-gushetia receive victims of armed vio-

INGUSHETIA

02

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

© M

isha

Frie

dman

03

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

lence,” says Lamara Umarova, a supervi-sor for MSF’s mental health activities in the Caucasus. “It is beyond normal hu-man life. When people experience trau-matic stress, it overturns their perception of the world. Our counsellors work with the victims of violence and their relatives who are also suffering.”

MSF has been present in Ingushetia since 1999 when the second Chechen war started, supporting those displaced by the conflict. Today MSF provides primary healthcare to displaced people as well as the most vulnerable members of society. A psychosocial program has been an im-portant element of MSF activities in the republic since 2003. This work continues today, but its scope and focus has ex-panded, since almost all the inhabitants of Ingushetia are suffering from the cur-rent violence.

The numbers and their increase reflect a harsh reality: 439 violence-related con-sultations in January 2008 compared to 1,266 in September 2009. These are cases of trauma caused by violent inci-dents with its typical psychological con-sequences: overwhelming feelings such as fear, constant alarm and vigilance, grief and sadness; as well as symptoms of trauma such as sleeping problems, undesirable thoughts and flashbacks.

The insecure situation in the republic has changed the atmosphere in the society.

Madina, an MSF counsellor, sees this over and over: “Here – and it was the same in Chechnya [during the war] – there are many people who go to sleep dressed. They don’t change into sleepwear be-cause you never know what will happen to you at night. And how can you go out undressed? Our mentality doesn’t per-mit that.”

MSF mental health services are imple-mented by nine counsellors like Madi-na in three districts of Ingushetia, with a focus on acute trauma. The three main centres are open five days a week in the district hospitals of Nazran, Sun-zha and Malgobek. Aiming to provide better access for people in need, the counsellors receive clients weekly in six village clinics.

Mental health counsellors work in co-operation with local Ministry of Health staff. The medical service admits survi-vors of violence and refers these patients and their relatives to MSF counsellors or invites them to the facility. The Ministry of Health doctors acknowledge the posi-tive impact of this cooperation; they see their patients get better both physically and mentally after these sessions.

Over the past two years MSF has seen a sharp rise in the number of mental health consultations in Ingushetia, the propor-tion of violence-related consultations growing to approximately 90 per cent.

“I have become very nervous, irritable re-cently,” says one client, Sultan, who is 65 years old. “Every time I hear about a killing or a kidnapping I feel some dull ache in my chest, my blood pressure rises and my fingers grow numb. My own story comes back to me and I go through the night-mare again: I am taken into the forest with no explanation. They put a bag on my head and conducted me somewhere strik-ing my shoulder with a machine gun.”

“I hope that you will help me,” he says to his counsellor.

It is not easy to relieve acute traumatic stress, but observing the principle of strict confidentiality, using different counselling techniques and simply dis-playing sincere human sympathy allows MSF counsellors to gradually gain their clients’ trust and offer them real help. “After counselling sessions people are better aware of their condition, their problems,” Umarova says of MSF’s work with patients. “They understand how to cope with them, but it’s not easy to do that given the situation they live in.”

Maria BorshovaCommunications officer

Follow MSF head of mission for North Caucasus, Willem de Jonge, on Twitter at: www.twitter.com/msfrussia

© M

aria

Bor

shov

a

© M

isha

Frie

dman

04

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

Quickly changing into his green gown, Dr. Maslah hurries to the operating theatre in South Galcayo

hospital to perform an emergency op-eration on a young man who has been stabbed. “The call came at 8 p.m.,” he explains. “By 10 p.m. we were in theatre and by 11 p.m. we had managed to stabi-lize the patient.”

The following morning relatives of the patient gather in the hospital chatting, and sometimes even laughing loudly, as they receive news that the young man is going to be OK. They reassure friends and other relatives who arrive, having rushed to the hospital fearing the worst.

As one of 144 Somali staff working for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in South Galcayo hospital, Dr. Maslah has played a crucial part in keeping the surgical ac-tivities running. In early 2008, at a time when the conflict in Somalia was intensi-fying and medical needs were increasing,

SOMALIA

Around-the-clock healthcare

saves countless lives

in South Galcayo hospital

© M

SF

05

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

MSF IN SOmalia

MSF has worked in Somalia for more than 17 years and continues to provide free medical care in eight regions of the country thanks to MSF’s commit-ted Somali staff, who are supported by a remote management team based in Nairobi. In 2008 alone, MSF teams provided 727,428 outpatient consulta-tions, including 267,168 for children under five. Over 55,000 women re-ceived antenatal care consultations and more than 24,000 people were admit-ted as inpatients to MSF-supported hospitals and health clinics. There were 3,878 surgeries, 1,249 of which were for injuries due to violence. Medical teams treated 1,036 people suffering from the deadly neglected disease kala azar, more than 4,000 for malaria and started 1,556 people on tuberculosis treatment. Nearly 35,000 people suf-fering from malnutrition were provided with food and medical care and 82,174 vaccinations were given.

MSF was forced to evacuate its interna-tional staff from the country. Since then MSF’s projects have been run by Somali staff, supported and supervised by man-agement teams based in Nairobi who visit whenever security allows. Without the work of Dr. Maslah and the hundreds of other Somali staff that work for MSF throughout the country, thousands of people would have been left without free lifesaving medical care.

Night time phone calls for urgent opera-tions are a routine part of Dr. Maslah’s work, as South Galcayo hospital is the only hospital to provide free emergen-cy surgery in the area. “Every month I’ll perform around 40 operations on people with abdominal injuries,” says Dr. Maslah, “gunshot and stab wounds, injuries of the colon and people who’ve been in car accidents.”

Surgery is just one of the services MSF provides in South Galcayo hospital, where some patients come from as far away as Ethiopia to receive care. The waiting room of the outpatient depart-ment, the inpatient department, the ‘out of bounds for men’ wards of the materni-ty department and the bright, ventilated compound of the tuberculosis centre all have one thing in common – they are all constantly teeming with activity. Every month MSF gives almost 4,000 outpa-tient consultations, admitting around 120 people for inpatient care and deliv-ering more than 100 babies.

Prolonged drought coupled with fight-ing and high food prices means the nutri-tional centre is often packed to capacity. Pointing to a queue of frustrated-looking women holding weak, dehydrated ba-bies waiting to be admitted to MSF’s therapeutic feeding centre, Jibril the su-pervisor explains: “Every month we ad-mit several cases of diarrhea, measles, dehydration and sometimes meningitis. But now severe acute malnutrition is becoming the most common problem. We are currently treating 90 patients in a space meant for only 60.”

The exhaustion on the mothers’ faces re-veals the long journey that most of them have made to reach the hospital. Because of the ongoing insecurity, MSF teams are un-able to go out in cars and collect patients. As one mother says, “Many in the village know that there is free treatment here, but the biggest problem is the journey. It can take many days and is often very expen-sive, costing around 500,000 Somali shil-lings (the equivalent of about $10). A lot of people can’t afford it, so they stay at home and some of them die in the village.”

The burn marks on the bodies of a num-ber of the young babies in the feeding centre show that many of the mothers first turn to traditional healers for treat-ment and only come to the hospital as a last resort.

In sharp contrast to the group of waiting mothers is a woman wearing a big smile

standing at the door of the feeding centre. In one arm she carries a healthy looking baby and in the other she holds a bag containing the family food ra-tion she has been given by MSF to take home. She raises her voice above the deafening noise of the crying children to thank one of the staff. “She has been here for quite some time and today she is returning home with a healthy baby,” says Jibril.

MSF staff like Jibril and Dr. Maslah work around the clock at South Galcayo hos-pital with many other committed Somali staff to make a profound difference. “The staff at this hospital save many lives,” says Dr. Maslah.

In a country where violence, suffering and death from preventable and treat-able diseases are commonplace, the pro-vision of free independent medical care is vital.

Ahmed Dahir and Susan SandarsCommunications officers

© M

SF

06

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

YEMEN

When war is raging, surgery saves lives. Such is the case in Yemen, where Médecins Sans Frontières

(MSF) continued to provide emergency aid at the end of 2009 in the midst of a renewed battle in the country’s north.

But as anesthesiologist Arnaud Drouart discovered working with MSF amidst the chaos of conflict in Yemen, to save lives doctors need to be able to get to their patients.

“Two or three times we had to postpone surgical operations because we couldn’t risk going to collect the patients waiting in the tents,” says Drouart. “We would stay together in the operating room for half an hour or an hour, waiting for the fighting nearby to stop so that we could transfer the patient to the recovery room (there are windows in the recovery room) and then go and collect other pa-tients from the tents.”

Fighting began between the Yemeni army and a group known as Al Houthi in Saada province in August 2009. Fre-quent violent clashes took place mostly around Saada City, along the Saada-Baqim road, and, farther west, around Haydan and Malaheed.

As of November 2009, MSF was the only international medical organization able to continue working in the region since the renewed outbreak of hostilities. Staff were doing everything to remain as close as possible to the population, while en-suring the security of patients and medi-cal teams. At times, some international staff had to be evacuated from the area, and staff travel was severely restricted.

“I remember the night when they didn’t stop bombing,” says Drouart, “and I was telling myself, ‘there will be wound-ed arriving soon, there will be wounded arriving soon.’ And sure enough, in the middle of the night we had to operate on a patient. The possibility of trans-ferring a patient was totally unpredict-able. And I think it was the same for the patients: one day they could get to the hospital, the next it was not possible… it was very uncertain.”

MSF supports two Ministry of Health hospitals in Yemen, one located in Shara’a in Razeh district, and the other in Al Talh in Saher district. In both hospitals, free medical services provided by MSF include primary healthcare, emergency consultations and hospitalizations, and gynecological and obstetrical care.

In Al Talh, where Drouart was working, MSF also conducts emergency surgery. Between Aug. 11 and Sept. 27, the MSF team performed 195 surgeries, 135 of which were for war-related wounds.

During intense fighting in September and October 2009, running all of these activi-ties became increasingly complex, despite authorizations MSF had from both sides.

In some cases, aid was not possible de-spite the immense needs. “At one point we had to temporarily stop surgical activities in Al Talh and reduce the sup-port we provide to primary health struc-tures,” says Andrés Romero, MSF head of mission in Yemen.

On Oct. 15, 2009, the hospital in Razeh was hit by rocket fire. Staff and patients were forced to evacuate the premises the following day despite the many people in need of continued medical attention. Just the day before, 10 war-wounded patients, including six children and two women, had been admitted. At the time, MSF teams had been performing around 560 emergency consultations per month in Razeh.

The continuous fighting in Yemen near the end of 2009 forced large numbers of

War surgery balancing risk and immense needs

© A

rnau

d D

roua

rt /

MSF

© A

rnau

d D

roua

rt /

MSF

07

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

people to flee repeatedly. It was difficult to obtain precise figures on the overall number of displaced people as rescue teams and humanitarian organizations had difficulties reaching all areas. Ac-cording to UN figures, at one point there were approximately 60,000 displaced people registered in Saada, Amran and Hajja governorates.

In August 2009, MSF also began provid-ing aid to people displaced by the conflict in Mandabah area, north of Saada. A wa-ter supply system was created to provide drinking water for around 250 families.

As others providing assistance concentrat-ed on the distribution of food and non-food items, MSF focused on providing medical care for the people in this area.

“Healthcare access in the governorate is definitely an issue, as most of the health structures are not functioning anymore and others are very difficult to access. It remains difficult to estimate the number of civilian casualties,” says Romero.

MSF has worked in Saada governorate in northern Yemen since September 2007, providing medical care to the popula-tion affected by the conflict that began in 2004 between government forces and the group Al Houthi.

Between January and October 2009, in Saada governorate, MSF teams car-ried out 32,000 consultations, of which 10,000 were for emergencies, and ad-

mitted 1,780 people to hospital. Dur-ing the same period, teams performed 915 surgeries, around 255 of them for war injuries.

“It has been a daily challenge for MSF to continue offering assistance in such difficult security conditions,” adds Romero, “considering the numerous problems, namely insecurity and lack of communication.” All land and wireless telephones have been unreliable, roads linking Saada governorate with the rest of the country have been blocked and MSF Yemeni staff have often been working in hospitals without contact with their families. Though MSF takes all possible security precautions, even staff working in the hospitals can be at risk.

“The hospital was never directly tar-geted, but when fighting is close there can always be mistakes, stray bullets” says Drouart about his time as an anes-thesiologist in Al Talh hospital in August 2009. “We had the case of a stray bullet or a piece of shrapnel – we don’t know which – that burst through a tent and injured a staff member.”

MSF has adapted to the situation in Yemen by continually assessing secu-rity precautions, sending medical sup-plies and staff including a surgical team through Saudi Arabia, and by following very closely the evolution of the conflict.

This flexibility allows for continuing ef-forts to offer care to those who need it

most wherever they are. In November 2009, the organization started work to set up a hospital in Mandabah, close to the border with Saudi Arabia. The hos-pital will offer emergency consultations, surgery, primary and secondary health-care and maternity services to the thou-sands who have fled the conflict and are living in the Mandabah area.

Andréa BussottiCommunications officer

The story of four fi eld workers who struggle to provide emergency medical care under extreme circumstances. Coming soon to select theatres in Canada

See www.msf.ca for scheduled screening locations and dates.

Contact [email protected] if you want to organize a screening in your community!

SHORT-LISTED FOR AN ACADEMY AWARD®

© M

SF

© M

icha

el C

oles

08

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

ASIA-PACIFIC

© F

rede

ric B

aldi

ni /

MSF

When a disaster strikes, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) mobilizes to identify urgent needs and

carry out critical medical activities in a tar-geted effort to help save lives and reduce suffering. After a series of natural disasters hit the Philippines and Indonesia in late September 2009, MSF responded swiftly, providing primary healthcare, relief items and psychosocial support to people in-jured and displaced by the devastating floods and earthquake.

International MSF staff, including sur-geons, doctors, nurses and logisticians, joined Filipino and Indonesian staff as part of the aid effort.

PHILIPPINES

Typhoon Ketsana hit in the early morning hours of Sept. 26, 2009 dropping more

rain on Manila in 12 hours than the av-erage rainfall for the entire month. One week later, a second typhoon struck.

Devastating floods followed these storms, compounded by weeks of con-tinuous rain and subsequent mudslides, destroying dozens of towns and villages across the Philippines and killing hun-dreds of people.

“The water came in the evening and rose up to 10 feet. It was terrifying. I had never seen anything like this,” says 63-year-old Ernesto Ruperto, who was caught in the flooding with his family.

The disasters affected more than 8.4 mil-lion people and caused 849 deaths. MSF responded to the emergency by provid-ing medical assistance and relief items to the hardest hit communities across the country, including Manila and Laguna

Bay, as well as Pangasinan province.

In the slums near a canal east of Manila and in the affected areas of Laguna Bay, MSF ran mobile primary healthcare clin-ics; around 900 patients around Laguna Bay received care. In all areas, serious cases were referred to local hospitals. To meet essential daily needs, kits containing non-food items, such as soap and cooking utensils were distributed to 1,900 families, as well as 48 cleaning kits.

In Manila and surrounding areas, tens of thousands of people were forced to take shelter in crowded evacuation centres or partially-destroyed houses. After a disas-ter, people living in these conditions are exposed to waterborne and contagious diseases. Close medical follow-up is criti-cal. Diarrhea as well as respiratory and skin infections are common. After the flooding, MSF provided 50 latrines and

09

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

Emergency

relieffor survivors of floods and quake

© B

enoi

t Fin

ck /

MSF

© A

ndre

w C

abal

lero

-Rey

nold

s

10

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

sanitation kits with chlorine and brush-es to improve hygiene and mitigate the spread of disease in the evacuation cen-tres. In the flooded areas where people were staying in makeshift houses, MSF also organized human waste disposal to reduce the risks of contamination, as most latrines were underwater.

MSF teams working in Pangasinan prov-ince performed more than 2,000 mobile clinic consultations and distributed over 11,000 family kits, made up of household items such as soap, towels, blankets, buckets, cooking utensils, jerry cans and chlorine. One thousand construction kits were also given out, roughly one kit per 10 families in the area.

INDONESIA

On Sept. 30, 2009, the ground shook in Sumatra. An earthquake with a magni-tude of 7.6 struck the Indonesian island and killed at least 1,100 people. The is-land is located on the so-called Ring of Fire, an arc of fault lines on the Pacific basin prone to earthquakes and volca-nic eruptions.

Within three days, MSF was on the ground providing medical and humanitarian as-sistance. After an initial assessment of people’s needs, MSF mobile clinics went to some of the most neglected rural areas of the country – the villages near Padang and Pariaman.

As a medical humanitarian organi-zation, responding to emergen-cies – including disasters – has

always been at the heart of MSF’s work. However, as much as the organization wishes to always act, crises occur ev-ery day and it is beyond MSF’s capacity to respond to all of them. MSF is often faced with difficult decisions: Where to intervene and how to prioritize?

Immediately after a disaster, MSF teams strive to reach the affected area within 48 hours to conduct an assessment of the needs.

An assessment team consists of medical and logistical experts attempting to iden-tify the magnitude of the crisis and the immediate life-saving needs of the people who are affected. These needs may range from food, drinking water and sanitation, to emergency clinical services, psycho-logical support, shelter and fuel.

MSF also takes into consideration the existing response capacity – both local and international – to avoid duplication or overlapping of relief efforts. After the 2004 Asian tsunami, for example, the or-ganization decided to focus its efforts on Aceh in Indonesia as health needs were

more pressing in this hard-hit region of Indonesia compared with Thailand, where effective responses were mounted by the Thai community.

These types of initial assessments will usually take about two to 10 days de-pending on the nature and scale of the emergency. During these assessments, the MSF team will also distribute relief items to the survivors, donate medical supplies to local health facilities and pro-vide medical assistance if needed.

The information collected during these assessments allows MSF to gauge if there are unmet needs that teams may address. MSF ensures the best use of its limited resources to provide effective, high-quality aid.

MSF has observed in recent years that natural disasters have intense media cov-erage while other emergencies such as epidemics and armed conflict, receive comparatively little media attention. Un-expected, dramatic natural disasters like earthquakes and tsunamis are extremely newsworthy. However, media coverage may generate public demand for instant action before a careful assessment of needs is carried out.

These types of emergencies have a simi-lar pattern: when an emergency is wide-ly covered by mainstream news organi-zations, a huge influx of money and in-kind donations are quickly channelled to where the disaster occurred. In the first few days, these resources may help to ease the situation. However, the flooding of human and material resources without assessing and balancing the real need may overload the coordination of local and international groups and lead to an overlap or even a waste of relief efforts.

From time to time, following huge me-dia coverage of a natural disaster, it is not unusual to read about inappropriate donations of fresh food such as sushi, winter clothes to tropical regions, instant noodles to areas without cooking fuel or expired drugs sent to the affected areas.

Doing an assessment before deciding the appropriate way to respond is im-portant. Interventions should not only be quick but also based on the specific needs of the affected populations in each emergency.

Hoo Lai-tingCommunications officer

When to respond to a disaster? MSF considerations

© Ju

an-C

arlo

s To

mas

i

The clinics treated people with respira-tory tract infections, diarrhea and skin diseases, all health issues related to the difficult living conditions endured by survivors. Patients were monitored for infectious diseases to avoid the outbreak of an epidemic. MSF also distributed relief materials, including tarpaulins, blankets, mats, hygiene kits, kitchen kits and tool kits and pro-vided water and sanitation support to the villages near Pariaman. Close by, where there had been a landslide, MSF set up a camp with water-proof shelter for 90 families in the village of Kam-pung Panas.

Two weeks after the earthquake, medi-cal needs related to the disaster had been covered. The emergency phase of the mission ended and the recovery phase began. MSF continued to assess and fo-cus on the medical needs. “In an emer-gency, we need to be flexible, to adapt

our strategy to focus on the needs of the population,” says Elisabetta Maria Faga, MSF emergency coordinator in Padang.

MSF moved to provide mental health support to help people cope with the traumatic effects of the disaster. Group and individual consultations were car-ried out for both adults and children who needed more support. “I worried a lot and had difficulty sleeping during the first two weeks after the earth-quake, but I am getting better after a psy-chological consultation with MSF,” says 29-year-old Novaldi, a villager of Lubuk Laweh near Pariaman, who lost six mem-bers of his family in the earthquake.

The MSF teams in Indonesia consisted of 70 international and Indonesian staff working in Padang and Pariaman, includ-ing doctors, nurses, psychologists, water and sanitation specialists and logisticians.

Overall, 15,000 individuals representing 6,000 families received non-food items in Sumatra, including 20,000 hygiene and shelter kits. Water and sanitation projects and mental health services were pro-vided in villages and temporary shelters. MSF also supported a government-led mass vaccination campaign against mea-sles and tetanus. The intervention ended the third week of November, nearly eight weeks after the earthquake struck.

“Globally, the aim of MSF is always to in-tervene in the emergency phase address-ing the most pressing needs. Then both the government and other organizations will take over and be responsible for re-construction,” says Loreto Barcelo, MSF emergency coordinator in Pariaman.

Compiled by Kevin HillCommunications officer

Now available in stores on DVD

Triage: Dr. James Orbinski’s

humanitarian dilemma

Follow the powerful odyssey of James Orbinski, a humanitarian and doctor who returns to Africa to ponder the meaning of his life’s work and the value of helping others.

11

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

© Ju

an-C

arlo

s To

mas

i

12

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC

It has been almost two months since I left home. I think I’m into a groove. I’ve started to get comfortable shav-

ing using a computer screen as a mirror. It’s tricky to not allow any water to drip onto the keyboard, but totally doable. I have mastered straining coffee through a handkerchief without making too big a mess. And I’ve got a vocabulary in the local language M’Bai of about 35 words – nothing builds a therapeutic relation-ship like greeting someone in their own language and genuinely telling them they have a beautiful child.

To give an idea of how busy we are, here’s a snapshot of our sleeping sick-ness centre:

• TENT 1 All 12 beds filled with sleep-ing sickness patients.

• TENT 2 Seven of eight beds filled with malnutrition or severe malaria cases. One bed with a one-month-old baby who has sleeping sickness and severe malaria.

• TENT 3 One patient only. A one-year-old from Chad in isolation due to measles.

• TENT 4 Twelve patients in 11 beds. A set of newborn twins who arrived yes-terday – I put them in the same bed. Their mother died in childbirth and the children have not breast fed in three days. Until the family and I find a long-term solution, I’ve got to admit them.

• TENT 5 All 12 beds filled. Eleven with sleeping sickness patients and one with a young man with a possible seizure disorder.

• TENT 6 Eight patients in eight beds. Five patients with sleeping sick-ness and three with other illnesses.

In the small village of Maitikoulou, in northern Central African Republic (CAR), there is a bustling and vital sleeping sickness program run by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). In the 1960s it was widely believed the deadly disease Human African Trypanosomiasis (also known as sleeping sickness) had been virtually eradi-cated, and efforts to develop new drugs and to set up treatment programs were phased out. But the disease has made a resurgence, and among the remote villages in northern CAR the growing number of sleeping sickness cases is alarming. Dr. Raghu Venugopal explains.

Sleeping sickness makes a deadly comeback

© M

icha

el K

ottm

eier

/ A

gen

da

13

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

• HANGAR 1 Five sleeping sickness patients and one patient who needs to be transferred for surgery.

• NEW ADMISSIONS Eighteen sleeping sickness patients (17 to the hangar, and one in the one free bed).

• TOTAL PATIENTS 77• FREE BEDS 0

Although we primarily aim to treat sleep-ing sickness, people come with many other pathologies. Malaria, meningitis, malnutrition and emergencies related to pregnancy and childbirth – these urgencies require our attention as much as sleeping sickness. We can’t treat one disease and close our eyes to the other problems here.

But our main focus is sleeping sickness and, busy as we are already, we are spread-ing the word and actively encouraging

people from nearby villages to come and be treated. Our message must have spread to the village of Dilingala in southern Chad as that’s where Jean came from. I found him in the laboratory. Something was ob-viously wrong. Jean was a boy who looked about six or seven years old and was draped across his older brother’s arms, limp and barely able to open his eyes.

One of our out-patient department staff had sent Jean to the lab. He had request-ed a serological screening test for sleep-ing sickness. This rapid test looks for antibodies for sleeping sickness and just requires a quick pin prick.

Jean’s brother explained that Jean had be-come increasingly sick over the past week. He could not walk, he would sleep all day, he would not eat and he was having fe-vers. When I tried to make Jean walk, he

could barely stand. He seemed to be in a confused, altered mental state. He could not talk and he could not swallow the few drops of water we tried to give him. He would not cry or protest if pinched. When he did open his eyes he looked around in a wild and confused manner. This is sleep-ing sickness – the worst kind.

Not surprisingly, the test for trypano-somiasis was positive, and other tests showed that he had moderately severe malaria as well. We did a lumbar punc-ture immediately to check the severity of the sleeping sickness. Lumbar punctures can actually be done pretty quickly and without too much suffering but – let’s face it – it does hurt anytime someone sticks a big needle in your back.

Our superb lab technician Yvonne – who is always keen to show us important lab

© M

icha

el K

ottm

eier

/ A

gen

da

14

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

findings – showed the actual trypano-some parasites swimming in Jean’s ce-rebral spinal fluid. We whisked Jean off to the inpatient department and the nurses immediately started his intrave-nous treatment for sleeping sickness. At the same time we treated him for ma-laria. That evening, when I did the night rounds, I found Jean’s mother sitting on the ground near our nurse’s station and I told her Jean was very sick but he was getting everything we had to help him. And with that, we put Jean in the closest tent to the nursing station.

Today is the fifth day of his treatment and each day he gets a little better. He is able to eat some therapeutic food, though he vomits from time to time – a side effect I attribute to the drug eflornithine.

Jean’s brother, who affectionately holds him a lot, says he talks to him but we could not coax any words out of him on today’s ward round. Jean still cannot walk very much though he can now follow simple commands like eye closing and shaking hands. The normal smile and giggle of a seven-year-old boy is what we’re waiting for. Maybe soon.

We’ve got big plans for the next few months. We’re going to try to build up some mobile (village-based) activities. The first step will be to take two MSF trucks and a small team to one of the nearby villages where, amongst other things, we will do a simple blood test for sleeping sickness from the back of the trucks for about 60 to 80 villagers. We hope to bring back to our camp anyone who is obviously sick.

Longer-term, we aim to move south and delve into untested villages where we suspect there is much more sleeping sickness to diagnose and treat.

To me, this is what MSF is all about – doing our best and providing necessary medical care under difficult circumstanc-es, ultimately measuring our success and the meaning of our work one patient and one name at a time.

Raghu VenugopalMedical doctor

WHAT IS

SLEEPING SICKNESS?Sleeping sickness is caused by a parasite that almost exclusively affects humans. The infection is passed from human to human through the aggressive tsetse fly. It is only found in Africa, where MSF’s treatment and research has done a lot to advance the care of this disease. Initially it causes intermit-tent fevers and a flu-like illness, followed by anemia, cardiac problems and severe neu-rological manifestations. A wide variety of neurological and psychiatric changes can occur, including difficulty sleeping, exces-sive daytime sleeping, clumsiness, confu-sion, mania, paranoia, depression and per-sonality changes. Patients can also develop movement disorders where they involun-tarily writhe around. The disease can ulti-mately end in coma and death.

New treatmentThe first new sleeping sickness treatment in 25 years was approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) in May 2009. Nifurtimox-eflornithine combination ther-apy (NECT) requires 14, rather than 56, intravenous infusions and is better suited to remote locations. “Until now, we have been losing patients because of toxic old drugs,” says Jacqueline Tong, head of MSF’s sleeping sickness program. “So we welcome and urgently need this new, safer and less complicated treatment to save lives.” MSF was one of the partners in developing NECT and has worked with the WHO to develop a kit that contains the medicine and all the equipment needed to administer the treatment.

$347 Total cost per patient (medicines, medical treatment and transport) using the NECT kit

$696 Total cost per patient using the older eflornithine treatment

An inspired way to support MSFTopping up your RRSPs? Did you know you can donate your RRSPs or RRIFs

by naming MSF as a full or partial beneficiary?

To learn more about charitable bequests or other planned gifts, please call me:Janice St-Denis | Planned giving offi cer | 1-800-982-7903, Ext. 3467

© M

icha

el K

ottm

eier

/ A

gen

da

BANGLADESHAmy Hollings Gabriola Island, BC Nurse

BRAZILTyler Fainstat Kingston, ON Head of mission

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLICMichele Beaudry Sechelt, BC Mental health specialist Nicolas Bérubé Montréal, QC LogisticianNicholas Gildersleeve Montréal, QC Project coordinator Nathalia Guerrero Montréal, QC Logistician Matthew Hatson Ottawa, ON Financial coordinatorMiriam Lindsay Irlande, QC LogisticianTara Newell London, ON Project coordinatorRobert Parker Sutton, QC Head of missionRaghu Venugopal Toronto, ON Doctor

CHADSerena Kasparian Montréal, QC DoctorCaroline Pelletier Montréal, QC LogisticianMatthew Schraeder Massey, ON LogisticianAda Yee Calgary, AB Financial coordinator

COLOMBIAElaine Sansoucy Montréal, QC Nurse

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGOTamiko Andrews Montréal, QC NurseCharmaine Brett Ottawa, ON Project coordinatorOwen Campbell Montréal, QC LogisticianNadine Crossland North Battleford, SK NurseFrédéric Dubé Québec, QC LogisticianClaire Foulon-Abdulahad Montréal, QC LogisticianChantal Gauthier Varennes, QC NurseReine Lebel Pontiac, QC Mental health specialist Isabelle Major Trois-Rivières, QC LogisticianAli Parandeh Port Moody, BC Financial coordinatorGisèle Poirier Montréal, QC NurseDenis Roy Montréal, QC Mental health specialistNicolas Verdy Montréal, QC Logistician

ETHIOPIAHarry MacNeil Toronto, ON Water and sanitation specialist

HAITIPatrick Boucher Québec, QC LogisticianMichelle Chouinard St-Quentin, NB Head of mission Annie Dallaire Ile-Perrot, QC Financial coordinator Marise Denault Hull, QC Project coordinatorDanielle Trepanier Stoney Point, ON Logistician

INDIARichard Crysler St. Catharines, ON Mental health specialistDiane Rachiele Montréal, QC Financial coordinator Wendy Rhymer Winnipeg, MB Nurse

IRAQReshma Adatia Vancouver, BC Project coordinator

KENYAMaguil Gouja Montréal, QC Financial coordinator Lauralee Morris Brampton, ON DoctorLuis Neira Montréal, QC Medical coordinator

MALIMartine Verreault Rivière-du-Loup, QC Pharmacist

MOZAMBIQUEIsabelle Casavant Montréal, QC NurseSerge Kaboré Québec, QC Doctor

MYANMARAnne-Josée Boutin-Trudeau Montréal, QC LogisticianIsabelle Roger Gatineau, QC Epidemiologist

NIGERDavid Descossy Montréal, QC LogisticianMichèle-Alexandra Labrecque Montréal, QC DoctorMarie-Michèle Houle Victoriaville, QC Nurse

PAKISTANPeter Heikamp Montréal, QC LogisticianIvan Gayton Vancouver, BC Project coordinator

PHILIPPINESGrant Assenheimer Edmonton, AB Logistician

Rachelle Séguin Greenfield Park, QC NurseJL Crosbie Toronto, ON Logistician

PAPUA NEW GUINEAJaroslava Belava Vancouver, BC NurseNadia Perreault Mascouche, QC NurseBrenda Vittachi Calgary, AB Nurse

SOUTH AFRICACheryl McDermid Vancouver, BC Doctor

SOMALIAAdam Childs Guelph, ON Head of mission

SUDANJustin Armstrong Haileybury, ON Project coordinator Edith Cabot Halifax, NS NurseOonagh Curry Toronto, ON LogisticianSylvain Groulx Montréal, QC Head of mission Michael Lawson Ottawa, ON LogisticianLetitia Rose Vancouver, BC NurseMichael White Toronto, ON Project coordinator

SRI LANKASarah Lamb Ottawa, ON LogisticianGrace Tang Toronto, ON Project coordinatorFiona Turpie Hamilton, ON Anesthetist

UGANDAAlphonsine Mukakigeri Montréal, QC Financial coordinator

ZIMBABWENicolas Hamel Montréal, QC NurseIvik Olek Montréal, QC Nurse

CANADIANS ON MISSION

DISPATCHESMédecins Sans Frontières (MSF)720 Spadina Avenue, Suite 402 Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2T9Tel: 416-964-0619Fax: 416-963-8707Toll free: 1-800-982-7903Email: [email protected]

www.msf.ca

Editor: linda o. nagyEditorial director: Avril BenoîtTranslation coordinator: Jennifer OcquidantContributors: Maria Borshova, Andréa Bussotti, Ahmed Dahir, Kevin Hill, Hoo Lai-ting, Susan Sandars, Raghu Venugopal

Cover photo: © Simon C RobertsBack page created by Jordan Cohen and Damian Simev as part of the Young Lions ad competition.

Circulation: 90,500Layout: Tenzing CommunicationsPrinting: Warren’s Waterless PrintingWinter 2010

ISSN 1484-9372

15

Dis

pat

ches

Vol

. 12,

Ed.

1

affl iction

Your donation makes the distinction.www.msf.ca