BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION

-

Upload

steve-b-salonga -

Category

Documents

-

view

316 -

download

4

description

Transcript of BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION

is a project of the National Center for Appropriate Technologyis a project of the National Center for Appropriate Technologyis a project of the National Center for Appropriate Technologyis a project of the National Center for Appropriate Technology

www.attra.ncat.org

By Steve Diver — NCAT Agriculture SpecialistFebruary 1999

Introduction

Biodynamic agriculture is an advanced organicfarming system that is gaining increased attentionfor its emphasis on food quality and soil health.

Biodynamic agriculture developed out of eightlectures on agriculture given in 1924 by RudolfSteiner (1861−1925), an Austrian scientist andphilosopher, to a group of farmers near Breslau(which was then in the eastern part of Germanyand is now Wroclaw in Poland). These lectures,as well as four supplemental lessons, arepublished in a book titled Spiritual Foundations forthe Renewal of Agriculture, originally published inEnglish as An Agricultural Course (1).

The Agriculture Course lectures were taught bySteiner in response to observations from farmersthat soils were becoming depleted following theintroduction of chemical fertilizers at the turn ofthe century. In addition to degraded soilconditions, farmers noticed a deterioration inthe health and quality of crops and livestock. Thus, biodynamic agriculture was the firstecological farming system to develop as agrassroots alternative to chemical agriculture.

A basic ecological principle of biodynamics is toconceive of the farm as an organism, a self-contained entity. A farm is said to have its own

800-346-9140

Appropriate Technology Transfer for RuralA

BIODYNAMIC FARMING &COMPOST PREPARATION

ATTRA is the national sustainable agriculture information center funded by the USDA’s Rural Business -- Cooperative Service.

Abstract: Biodynamic agriculture was the first ecological farming system to arise in response to commercialfertilizers and specialized agriculture after the turn of the century, yet it remains largely unknown to themodern farmer and land-grant university system. The contribution of biodynamics to organic agriculture issignificant, however, and warrants more attention. The following provides an overview of biodynamicfarming and includes additional details and resources on the specialized practice of biodynamic composting.

ContentsBiodynamic Preparations....................................... 3Biodynamic Compost............................................. 3Liquid Manures & Herbal Teas .............................. 8Planetary Influences .............................................. 9Community Supported Agriculture......................... 9Food Quality .......................................................... 9Research into Biodynamics ................................... 10Journals & Newsletters .......................................... 10References ............................................................ 11Contacts................................................................. 12Suggested Reading on Biodynamic Farming ........ 13Suggested Reading on Biodynamic Compost ....... 14Email Discussion Groups ...................................... 14World Wide Web Links .......................................... 15Publishers/Distributors of Biodynamic Literature... 15

ALTERNATIVE FARMING SYSTEMS GUIDE

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 2

individuality. Emphasis is placed on theintegration of crops and livestock, recycling ofnutrients, maintenance of soil, and the healthand wellbeing of crops and animals; the farmertoo is part of the whole. Thinking about theinteractions within the farm ecosystem naturallyleads to a series of holistic managementpractices that address the enviromental, social,and financial aspects of the farm. A comparisonof objectives between biodynamic andconventional agriculture systems in Appendix Isummarizes these ideas in table format.

A fundamental tenet of biodynamic agricultureis that food raised biodynamically isnutritionally superior and tastes better thanfoods produced by conventional methods. Thisis a common thread in alternative agriculture,because other ecological farming systems makesimilar claims for their products. Demeter, acertification program for biodynamically grownfoods, was established in 1928. As such,Demeter was the first ecological label fororganically produced foods.

Today biodynamic agriculture is practiced onfarms around the world, on various scales, andin a variety of climates and cultures. However,most biodynamic farms are located in Europe,the United States, Australia, and New Zealand.

While biodynamics parallels organic farming inmany ways especially with regard to culturaland biological farming practices it is set apartfrom other organic agriculture systems by itsassociation with the spiritual science ofanthroposophy founded by Steiner, and in itsemphasis on farming practices intended toachieve balance between the physical andhigher, non-physical realms†; to acknowledgethe influence of cosmic and terrestrial forces;

and to enrich the farm, its products, and itsinhabitants with life energy‡. Appendix II is atable that illustrates cosmic and terrestrialinfluences on yield and quality.

In a nutshell, biodynamics can be understood asa combination of “biological dynamic”agriculture practices. “Biological” practicesinclude a series of well-known organic farmingtechniques that improve soil health. “Dynamic”practices are intended to influence biological aswell as metaphysical aspects of the farm (suchas increasing vital life force), or to adapt thefarm to natural rhythms (such as planting seedsduring certain lunar phases).

The concept of dynamic practice thosepractices associated with non-physical forces innature like vitality, life force, ki, subtle energy andrelated concepts is a commonality that alsounderlies many systems of alternative andcomplementary medicine. It is this latter aspectof biodynamics which gives rise to thecharacterization of biodynamics as a spiritual ormystical approach to alternative agriculture. See the following table for a brief summary ofbiological and dynamic farming practices.

† The higher, non-physical realms include etheric,astral, and ego. It is the complicatedterminology and underlying metaphysicalconcepts of Steiner which makes biodynamicshard to grasp, yet these are inherent in thebiodynamic approach and therefore they arelisted here for the reader’s reference.

‡ Life energy is a colloquial way of saying ethericlife force. Again, Steiner’s use of terms likeetheric forces and astral forces are part andparcel of biodynamic agriculture.Biodynamic farmers recognize there areforces that influence biological systems otherthan gravity, chemistry, and physics.

Bio-Dynamic Farming PracticesBiological Practices Dynamic Practices Green manures Special compost preparations Cover cropping Special foliar sprays Composting Planting by calendar Companion planting Peppering for pest control Integration of crops and livestock Homeopathy Tillage and cultivation Radionics

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 3

Dr. Andrew Lorand provides an insightfulglimpse into the conceptual model ofbiodynamics in his Ph.D. dissertationBiodynamic Agriculture A ParadigmaticAnalysis, published at Pennsylvania StateUniversity in 1996 (2).

Lorand uses the paradigm model described byEgon Guba in The Alternative Paradigm Dialog (3)to clarify the essential beliefs that underpin thepractices of biodynamics. These beliefs fall intothree categories:

1. Beliefs about the nature of reality withregard to agriculture (ontological beliefs)

2. Beliefs about the nature of the relationshipbetween the practitioner and agriculture(epistemological beliefs); and,

3. Beliefs about how the practitioner shouldgo about working with agriculture(methodological beliefs).

Lorand's dissertation contrasts the ontological,epistemological, and methodoligical beliefs offour agricultural paradigms: TraditionalAgriculture, Industrial Agriculture, OrganicAgriculture, and Biodynamic Agriculture. Asummary of these four paradigms can be foundin Tables 1−4, Appendix III.

The Biodynamic Preparations

A distinguishing feature of biodynamic farmingis the use of nine biodynamic preparationsdescribed by Steiner for the purpose ofenhancing soil quality and stimulating plantlife. They consist of mineral, plant, or animalmanure extracts, usually fermented and appliedin small proportions to compost, manures, thesoil, or directly onto plants, after dilution andstirring procedures called dynamizations.

The original biodynamic (BD) preparations arenumbered 500−508. The BD 500 preparation(horn-manure) is made from cow manure(fermented in a cow horn that is buried in the soilfor six months through autumn and winter) andis used as a soil spray to stimulate root growthand humus formation. The BD 501 preparation

(horn-silica) is made from powdered quartz(packed inside a cow horn and buried in the soilfor six months through spring and summer) andapplied as a foliar spray to stimulate and regulategrowth. The next six preparations, BD 502−507,are used in making compost.

Finally, there is BD preparation 508 which isprepared from the silica-rich horsetail plant(Equisetum arvense) and used as a foliar spray tosuppress fungal diseases in plants.

The BD compost preparations are listed below:

• No. 502 Yarrow blossoms (Achillea millefolium)• No. 503 Chamomile blossoms (Chamomilla officinalis)• No. 504 Stinging nettle (whole plant in full bloom) (Urtica dioca)• No. 505 Oak bark (Quercus robur)• No. 506 Dandelion flowers (Taraxacum officinale)• No. 507 Valerian flowers (Valeriana officinalis)

Biodynamic preparations are intended to helpmoderate and regulate biological processes aswell as enhance and strengthen the life (etheric)forces on the farm. The preparations are used inhomeopathic quantities, meaning they producean effect in extremely diluted amounts. As anexample, just 1/16th ounce a level teaspoon of each compost preparation is added toseven- to ten-ton piles of compost.

Biodynamic Compost

Biodynamic compost is a fundamentalcomponent of the biodynamic method; it servesas a way to recycle animal manures and organicwastes, stabilize nitrogen, and build soil humusand enhance soil health. Biodynamic compost isunique because it is made with BD preparations502−507. Together, the BD preparations and BDcompost may be considered the cornerstone ofbiodynamics. Here again, “biological” and“dynamic” qualities are complementary: biodynamic compost serves as a source ofhumus in managing soil health and biodynamiccompost emanates energetic frequencies tovitalize the farm.

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 4

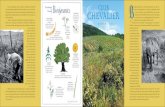

The traditional manner in which the biodynamic compost is made is rather exacting. After the compostwindrow is constructed, Preparations 502−506 are strategically placed 5−7 feet apart inside the pile, inholes poked about 20 inches deep. Preparation No. 507, or liquid valerian, is applied to the outside layerof the compost windrow by spraying or hand watering.

Figure 1. Use of Biodynamic Preparations in a Compost Pile

Valerian (507) is mixed into a liquid; a portion is poured into onehole, andthe rest is sprinkled over the top of the compost pile.

More specific instructions on biodynamicpreparations, placement in the compost,compost making, and compost use can be foundin the following booklets, available through theBiodynamic Farming and GardeningAssociation (BDFGA) in San Francisco,California (4):

Blaser, Peter, and Ehrenfried Pfeiffer. 1984. Bio-Dynamic Composting on theFarm; How Much Compost Should We Use?Biodynamic Farming and GardeningAssociation, Inc., Kimberton, PA. 23p.

Corrin, George. 1960. Handbook onComposting and the Bio-DynamicPreparations. Bio-Dynamic AgriculturalAssociation, London. 32 p.

Koepf, H.H. 1980. Compost − What It Is,How It Is Made, What It Does. Biodynamic Farming and GardeningAssociation, Inc., Kimberton, PA. 18 p.

Pfeiffer, Ehrenfried. 1984. Using the Bio-Dynamic Compost Preparations & Sprays inGarden, Orchard, & Farm. Bio-DynamicFarming and Gardening Association,Inc., Kimberton, PA. 64 p.

Dr. Ehrenfried Pfeiffer (1899−1961), a soilmicrobiologist and agronomic researcher who

worked directly with Steiner, conductedextensive research on the preparation and use ofbiodynamic compost. For many years Pfeifferserved as a compost consultant to municipalcompost facilities, most notably Oakland, CA, aswell as countries in the Caribbean, Europe, andthe Far East.

Pfeiffer’s research into the microbiology ofcompost production led to the development of acompost inoculant, BD Compost Starter®, thatcontains all the BD compost preparations(502−507) plus stirred BD No. 500, as well as 55different types of microorganisms (mixedcultures of bacteria, fungi, actinomycetes,yeasts). BD Compost Starter® is widely used bybiodynamic farmers because it is easy to applywhile building the compost pile. Today, thestarter is prepared and sold through theJosephine Porter Institute (JPI) for AppliedBiodynamics (5) in Woolwine, Virginia.

While use of BD compost preparations and/orBD Compost Starter® is universal in biodynamiccomposting, the actual construction andmaintenance of compost piles includingfrequency of aeration and length till maturity may vary among farming operations.

Dandelion (506) Yarrow (502)

Nettle (504) Oak Bark (505)

Valerian (507) Chamomile (503)

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 5

The static pile method is the traditionalbiodynamic choice. In static piles materials areformed into a windrow, inoculated with BDpreparations, covered with straw, and leftundisturbed for 6 months to one year prior touse. A small amount of soil is commonlysprinkled onto the outside of the pile prior tocovering with straw. Soil can also be addedduring the windrow construction process, whenbrown (carbon) and green (nitrogen) feedstockmaterials are laid in alternating layers.

On larger farms that handle massive volumes ofcompost feedstock, the piles are often managedwith a compost turner, so the time to maturity ismuch shorter, for example 2−3 months. A newdevelopment is the aerated static pile (ASP),wherein ventilation pipes are inserted into astatic pile to increase oxygen supply and reducethe length of time to compost biomaturity.

Contrasting viewpoints exist in the compostindustry as well as amongst on-farm compostmakers as to which method is best. When pushcomes to shove, most people agree that the bestcompost method is one that fits the individualfarmer’s situation.

Recent biodynamic research supports the staticpile approach as a viable compost option. In theJuly−August 1997 issue of Biodynamics , Dr.William Brinton (6) of Woods End AgriculturalResearch Institute published “Sustainability ofModern Composting: Intensification VersusCosts and Quality. ” Brinton argues that low-tech composting methods are just as effective instabilizing nutrients and managing humus asthe management and capital intensive compostsystems that employ compost turners and dailymonitoring. These findings are particularlyencouraging to farmers choosing the low-inputapproach to this age-old practice oftransforming organic matter into valuablehumus. The full report can be viewed onWoods End Institute’s website at: <www.woodsend.org/sustain.pdf>.

At the other end of the compost spectrum arethe high intensity windrow systems forexample the Controlled Microbial Compostingsystem promoted by the Siegfried Luebke

family of Austria and the Advanced CompostSystem promoted by Edwin Blosser of

Midwestern Biosystems in Illinois thatemphasize specialized compost turners,microbial inoculation, frequent turning, dailymonitoring for temperature and CO2, compostfleece to cover and protect the windrow, andqualitative testing for finished compost. Inaddition to efficient handling of organic wastes,premium-grade compost is a goal.

It should be noted these highly mechanizedsystems seem to fit operations that generatelarge volumes of animal manures or othercompost feedstocks, such as a dairy farm or foodprocessing plant. On-farm production ofcompost is often matched with sale of bagged orbulk compost to local horticultural operations asa supplemental income.

Ultimately, the choice of composting methodwill depend to a large extent on the scale offarming operation, equipment and financialresources on hand, and intended goals forcompost end-use.

Research at Washington State University (WSU)by Dr. Lynn Carpenter-Boggs and Dr. JohnReganold found that biodynamic compostpreparations have a significant effect on compostand the composting process (7). Biodynamicallytreated composts had higher temperatures,matured faster, and had higher nitrates thancontrol compost piles inoculated with field soilinstead of the preparations. The WSU research isunique for two reasons: it was the firstbiodynamic compost research undertaken at aland-grant university, and it demonstrated thatbiodynamic preparations are not only effective,but effective in homeopathic quantities.

A summary of this research can be found on theUSDA-Agriculture Research Service's TektranWebsite at:

Effects of Biodynamic Preparations on CompostDevelopmentwww.nal.usda.gov/ttic/tektran/data/

000009/06/0000090623.html

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 6

In related research, Carpenter-Boggs andReganold found that biodynamically managed

soils (i.e., treated with biodynamic compost andbiodynamic field sprays) had greater capacity tosupport heterotrophic microflora activity,higher soil microorganism activity, and differenttypes of soil microrganisms than conventionallymanaged soils (i.e., treated with mineralfertilizers and pesticides).

A summary of this latter research can be foundon the USDA-Agriculture Research Service'sTektran Website at:

Biodynamic Compost and Field Preparations: Effects on Soil Biological Communitywww.nal.usda.gov/ttic/tektran/data/

000009/06/0000090640.html

Because compost is often at a premium onfarms, European biodynamic researcher MariaThun developed Barrel Compost. Consisting offresh cow manure that has been treated with theoriginal preparations as well as egg shells andbasalt rock dust then allowed to ferment in apit for about 3 months, finished Barrel Compostis diluted in water and applied directly to thefields as a spray. Use of Barrel Compostcompensates to some degree for lack ofsufficient compost. A variation on BarrelCompost is mixing stinging nettle with freshcow manure in a 50:50 volume to volume ratio.

Some notable concepts and practices relating tosoil and compost management from thebiodynamic experience:

• Microbial inoculation: Dr. EhrenfriedPfeiffer’s work with composts in the 1940’sand 50’s led to the development of the BDCompost Starter®, one of the earliestcompost inoculants in commercial use in theUnited States.

• Soil in Compost: The addition of soil tocompost was an early biodynamic practiceprescribed by Steiner. Dr. Pfeiffer discussedthe reasons and benefits for adding soils tocompost in the 1954 edition of Bio-DynamicsJournal (Vol. 12, No. 2) in an article titled

“Raw Materials Useful for Composting.” Hesaid that soil is an essential ingredient to

• compost and should be added at 10%-20% ofthe windrow volume.

Mineralized Compost: The addition of rockpowders (greensand, granite dust) to compostpiles is a long-time biodynamic practice knownas mineralized compost. The dusts add mineralcomponents to the compost and the organicacids released during the decomposition processhelp solubilize minerals in the rock powders tomake nutrients more available to plants.

• Phases of Compost: An outgrowth of Dr.Pfeiffer’s compost research was a clearerunderstanding of the Breakdown and Buildupcompost phases:

The Breakdown Phase: In the breakdownphase organic residues are decomposed intosmaller particles. Proteins are broken downinto amino acids, amines, and finally toammonia, nitrates, nitrites, and freenitrogen. Urea, uric acids, and other non-protein nitrogen-containing compounds arereduced to ammonia, nitrites, nitrates, andfree nitrogen. Carbon compounds areoxidized to carbon dioxide (aerobic) orreduced methane (anaerobic). Theidentification and understanding ofbreakdown microorganisms led to thedevelopment of a microbial inoculant tomoderate and speed up the breakdownphase. The BD Compost Starter® developedby Dr. Pfeiffer contains a balanced mixtureof the most favorable breakdown organisms,ammonifiers, nitrate formers, cellulose,sugar, and starch digesters in order to bringabout the desired results. The microbialinoculant also works against organisms thatcause putrefaction and odors.

The Buildup Phase: In the build-up phasesimple compounds are re-synthesized intocomplex humic substances. The organismsresponsible for transformation to humus areaerobic and facultative aerobic, sporing andnon-sporing and nitrogen fixing bacteria ofthe azotobacter and nitrosomonas group.

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 7

Actinomycetes and streptomycetes also playan important role. The addition of soil, 10%

by volume, favors the development andsurvival of these latter organisms. Thedevelopment of humus is evident in colorchanges in the compost, and throughqualitative tests such as the circularchromatography method.

• Compost & Soil Evaluation: Biodynamicresearch into compost preparation and soilhumus conditions has led to thedevelopment or specialized use of severalunique qualitative tests. A notablecontribution of biodynamics is the image-forming qualitative methods of analysis;e.g., circular chromatography, sensitivecrystallization, capillary dynamolysis, andthe drop-picture method. Other methodsfocus on the biological-chemical condition;e.g., The Solvita® Compost Test Kit and TheSolvita® Soil Test Kit (8), colorimetrichumus value, and potential pH.

Cover Crops and Green Manures

Cover crops play a central role in managingcropland soils in biological farming systems. Biodynamic farmers make use of cover crops fordynamic accumulation of soil nutrients,nematode control, soil loosening, and soilbuilding in addition to the commonlyrecognized benefits of cover crops like soilprotection and nitrogen fixation. Biodynamicfarmers also make special use of plants likephacelia, rapeseed, mustard, and oilseed radishin addition to common cover crops like rye andvetch. Cover crop strategies includeundersowing and catch cropping as well aswinter cover crops and summer green manures.

Green manuring is a biological farming practicethat receives special attention on thebiodynamic farm. Green manuring involves thesoil incorporation of any field or forage cropwhile green, or soon after flowering, for thepurpose of soil improvement. Thedecomposition of green manures in soilsparallels the composting process in that distinctphases of organic matter breakdown and humus

buildup are moderated by microbes. Manybiodynamic farmers, especially those who

follow the guidelines established by Dr.Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, spray the green residue witha microbial inoculant (BD Field Spray®) prior toplowdown. The inoculant contains a mixedculture of microorganisms that help speeddecomposition, thereby reducing the time untilplanting. In addition, the inoculant enhancesformation of the clay-humus crumb whichprovides numerous exchange sites for nutrientsand improves soil structure.

Further information on this topic can be foundin the ATTRA publication Overview of CoverCrops and Green Manures<www.attra.org/attra-pub/covercrop.html>.

Crop Rotations & Companion Planting

Crop rotation the sequential planting of crops is honed to a fine level in biodynamicfarming. A fundamental concept of croprotation is the effect of different crops on theland. Koepf, Pettersson, and Schaumann speakabout “humus-depleting” and “humus-restoring” crops; “soil-exhausting” and “soil-restoring” crops; and “organic matterexhausting” and “organic matter restoring”crops in different sections of Bio-DynamicAgriculture: An Introduction (9).

Seemingly lost to modern agriculture with itsmonocrops and short duration corn-soybeanrotations, soil building crop rotations were under-stood more clearly earlier in this century when theUSDA published leaflets like Soil-Depleting, Soil-Conserving, and Soil-Building Crops (10) in 1938.

Companion planting, a specialized form ofcrop rotation commonly used in biodynamicgardening, entails the planned association oftwo or more plant species in close proximityso that some cultural benefit (pest control,higher yield) is derived. In addition tobeneficial associations, companion plantingincreases biodiversity on the farm which leadsto a more stable agroecosystem. See theATTRA publication Companion Planting: Basic

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 8

Concepts and Resources<www.attra.org/attra- pub /complant.html> for more information.

Liquid Manures and Herbal Teas

Herbal teas, also called liquid manures orgarden teas, are an old practice in organicfarming and gardening especially inbiodynamic farming yet little is publishedon this topic outside of the practitionerliterature. A complementary practice is the useof compost teas.

In reality, herbal teas usually consist of onefermented plant extract, while liquid manuresare made by fermenting a mixture of herb plantsin combination with fish or seaweed extracts. The purpose of herbal teas and liquid manuresare manyfold; here again, they perform dualroles by supporting biological as well as dynamicprocesses on the farm; i.e., source of solubleplant nutrients; stimulation of plant growth;disease-suppression; carrier of cosmic andearthly forces. To reflect their multi-purposeuse, they are sometimes referred to as immune-building plant extracts, plant tonics, bioticsubstances, and biostimulants.

Further insight into foliar-applied plant extracts,liquid manures, and compost teas can beunderstood by viewing biological farmingpractices in the way they influence therhizosphere or phyllosphere. (Those microbially-rich regions surrounding the root and leafsurfaces). Herbal teas and liquid manures aimto influence the phyllosphere; composts, tillage,and green manures influence the rhizosphere.

In addition to physical modification of the leafsurface to inhibit pathogen spore germinationor the promotion of antagonistic (beneficial)microbes to compete against disease-causingorganisms (pathogens), foliar-applied bioticextracts can sometimes initiate a systemicwhole plant response known as inducedresistance.

Horsetail tea is extracted from the commonhorsetail (Equisetum arvense), a plant especiallyrich in silica. Horsetail is best seen as aprophylactic (disease-preventing, not

disease-curing) spray with a mildfungus-suppressing effect. During the monthswhen green plants are not readily available, youcan prepare an extract by covering dry plantswith water and allowing them to ferment in asunny place for about ten days. Driedequisetum, available through the JosephinePorter Institute for Applied Biodynamics (5) inWoolwine, Virginia, can also be used to makehorsetail tea.

Stinging nettle tea is extracted from whole nettleplants (Urtica dioica) at any stage of growth up toseed−set. To make nettle tea, use about threepounds of fresh plants for every gallon of water,allow the mixture to ferment for about ten days,then filter it and spray a diluted tea. Dilutionrates of 1:10 to 1:20 are suggested in thebiodynamic literature. A biodynamic nettle teais prepared by adding BD preparations 502, 503,505, 506, and 507 prior to the soaking period.

Chamomile tea is derived from the flowers oftrue chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) whichhave been picked and dried in the sun. Freshflowers may be used too, but they are onlyavailable during a short part of the growingseason. To prepare the tea, steep about one cupof tightly packed flowers per gallon of hotwater. Stir well, and spray the filtered tea whencool. Chamomile is high in calcium, potash, andsulfur; it is good for leafy crops and flowers andpromotes health of vegetables in general.

Comfrey tea is another tea commonly used inorganic farming and gardening. Comfrey is arich source of nutrients; it is especially good forfruiting and seed filling crops. It can be madeby packing a barrel three-quarters full withfresh cut leaves, followed by topping the barrelfull of water. It is allowed to steep for 7−14days, then filtered and diluted in half withwater prior to use.

The Biodynamic Farming & GardeningAssociation (4) can supply literature on herbalteas. Two pamplets you may be interested toknow about are:

Pfeiffer, Ehrenfried. 1984. Using the Bio-Dynamic Compost Preparations & Sprays inGarden, Orchard, & Farm. Bio-Dynamic

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 9

Farming and Gardening Association,Inc., Kimberton, PA. 64 p.Koepf, H.H. 1971. Bio-Dynamic Sprays. Bio-Dynamic Farming and GardeningAssociation, Inc., Kimberton, PA. 16 p.

Compost teas are gaining wider recognition inbiodynamic and organic farming for theirdisease suppressive benefits as well as for theirability to serve as a growth-promoting microbialinoculant. See the ATTRA publication CompostTeas for Plant Disease Control for more detailedinformation at:<www.attra.org/attra-pub/comptea.html>.

Planetary Influences

Lunar and astrological cycles play a key role inthe timing of biodynamic practices, such as themaking of BD preparations and when to plantand cultivate. Recognition of celestial influenceson plant growth are part of the biodynamicawareness that subtle energy forces affectbiological systems. A selection of resources arelisted below. On examination of the variationsin agricultural calendars that have sprung fromthe biodynamic experience, it is apparent thatdiffering viewpoints exist on which lunar,planetary, and stellar influences should befollowed.

Stella Natura − The Kimberton Hills BiodynamicAgricultural Calendar, available throughBDFGA for $11.95, is the biodynamic calendaredited by Sherry Wildfeur and the mostprominently known calendar of this typein the United States. It contains informativearticles interspersed with daily and monthlyastrological details, and lists suggested timesfor planting root, leaf, flowering, andfruiting crops.

Working with the Stars: A Bio-Dynamic Sowingand Planting Calendar, available through JPI for$12.95, is the biodynamic calendar based onMaria Thun’s research and is more prominentlyused in Europe. Of the three calendarsmentioned here, Thun’s calendar relies moreheavily on planetary and stellar influences. Itcontains research briefs as well as daily andmonthly astrological details, again withsuggested planting times.

Astronomical Gardening Guide, available throughAgri-Synthesis in Napa, California (11) for aself-addressed stamped envelope, is thebiodynamic gardening guide compiled by GregWillis of Agri-Synthesis. This calender, which isa simple 2-sheet information leaflet, focuses onlunar phases.

Community Supported Agriculture

In its treatment of the farm as a self-containedentity or farm organism, biodynamics completesthe circle with appropriate marketing schemes tosupport the economic viability of farms. TheDemeter label for certified biodynamically grownfoods is one avenue. A second outgrowth of thisview is the Community Supported Agriculturemovement.

Community Supported Agriculture, or CSA, is adirect marketing alternative for small-scalegrowers. In a CSA, the farmer grows food for agroup of shareholders (or subscribers) whopledge to buy a portion of the farm's crop thatseason. This arrangement gives growers up-front cash to finance their operation and higherprices for produce, since the middleman hasbeen eliminated. Besides receiving a weekly boxor bag of fresh, high-quality produce,shareholders also know that they're directlysupporting a local farm.

Farms of Tomorrow Revisited: CommunitySupported Farms, Farm Supported Communities(12) by Trauger Groh and Steven McFadden is a294-page book that discusses the principles andpractices of CSA’s with insights to thebiodynamic perspective and farm case studies. The ATTRA publication Community SupportedAgriculture located on the ATTRA website at<www.attra.org/attra-pub/csa.html> provides a summary of ideas and businesspractices for CSA farms, accompanied byextensive resource listings.

Food Quality

A host of biodynamic researchers have lookedinto the quality of biodynamically grown foods.Though nutritional comparisons between foods

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 10

raised by organic and conventional productionmethods is controversial certainlymainstream science adheres to the view that nodifferences exist notable contributions frombiodynamic researchers include image-formingqualitative methods of analysis (e.g., sensitivecrystallization, circular chromatography,capillary dynamolysis, and the drop-picturemethod) and studies that report on nutritionalanalysis (13−15).

Research into Biodynamics

Research in Biodynamic Agriculture: Methods andResults (16) by Dr. H. Herbert Koepf is an 84-page booklet that presents an overview ofbiodynamic research from the early 1920s to thepresent. It includes testing methods, farm trials,university studies, and a complete bibliography.This pamphlet is especially useful because muchof the research features German studies whichare otherwise inaccessible to most Americans. Itlists for $9.95 in the BDFGA catalog.

Dr. John Reganold published a study in the April16, 1993 issue of Science “Soil Quality andFinancial Performance of Biodynamic andConventional Farms in New Zealand” thatcontrasted soil quality factors and the financialperformance of paired biodynamic and conven-tional farms in New Zealand (17). In a comparisonof 16 adjacent farms, the biodynamic farmsexhibited superior soil physical, biological, andchemical properties and were just as financiallyviable as their conventional counterparts.

Agriculture of Tomorrow (18) contains researchreports from 16 years of field and laboratorywork conducted by the German researchersEugen and Lilly Kolisko. Unlike much of thebiodynamic research by Koepf, Reganold,Pfeiffer, and Brinton which focuses on compostand soil agronomic conditions, the Koliskos diveright into the esoteric nature of biodynamics: themoon and plant growth; the forces ofcrystallization in nature; planetary influences onplants; homeopathy in agriculture; experimentswith animals to study the influence ofhomeopathic quantities; capillary dynamolysis;research on the biodynamic preparations.

Journals & Newsletters

Biodynamics, started by Dr. Ehrenfried Pfeifferin 1941, is the leading journal on biodynamicspublished in the United States. Contentsincludes scientific articles as well as practicalreports on: composts, soils, biodynamicpreparations, equipment, research trials,laboratory methods, biodynamic theory, andfarm profiles. Subscriptions are $35 per yearfor six issues, available through BDFGA (4).

Applied Biodynamics is the newsletter of theJosephine Porter Institute for Applied Bio-Dynamics, which makes and distributesbiodynamic preparations. The journal featuresarticles on use of the preparations, compostmaking procedures, and other biodynamicmethods from a practical perspective. Subscriptions are $30 per year for three issues,available through JPI (5).

The Voice of Demeter is the newsletter of theDemeter Association, which is the officialcertification organization for biodynamicallygrown foods. It is published twice yearly as aninsert to Biodynamics; separate copies are availableby request from Demeter Association (19).

Star and Furrow is the journal published by theBio-Dynamic Agricultural Association (BDAA)in England. Established in 1953, the Star andFurrow follows earlier publications of the BDAAdating back to the 1930s. Issued twice (‘Summer’and ‘Winter’) per year, overseas (airmail)subscriptions are £6 British pounds. Contact:

Star and FurrowBio-Dynamic Agricultural AssociationRudolf Steiner House35 Park RoadLondon NW1 6XTEngland

Harvests is the current publication of the NewZealand Biodynamic Farming and GardeningAssociation (NZ-BDGA), published four timesper year. The NZ-BDGA has published anewsletter or journal since 1947. Subscriptionsare NZ$55 per year. Contact:

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 11

HarvestsNZ−BDGAP.O. Box 39045Wellington mail CentreNew ZealandTel: 04 589 5366Fax: 04 589 5365

The News Leaf is the quarterly journal of theBiodynamic Farming and GardeningAssociation of Australia Inc. (BDFGAA), inprint since 1989. Subscriptions are $US25. Contact:

The News LeafBDFGAAP.O.Box 54Bellingen 2454 NSWAustraliaTel/Fax +2 66558551 or +2 [email protected]

Summary −−−−Viewpoint −−−− Conclusion

Biodynamics uses scientifically sound organicfarming practices that build and sustain soilproductivity as well as plant and animal health.The philosophical tenets of biodynamics especially those that emphasize energetic forcesand astrological influences are harder tograsp, yet they are part and parcel of thebiodynamic experience.

That mainstream agriculture does not accept thesubtle energy tenets of biodynamic agricultureis a natural result of conflicting paradigms. Inmainstream agriculture the focus is on physical-chemical-biological reality. Biodynamicagriculture, on the other hand, recognizes theexistence of subtle energy forces in nature andpromotes their expression through specialized“dynamic” practices.

A third view, expressed by a local farmer,accepts the premise that subtle energy forcesexist and may affect biological systems, butholds there is not enough information toevaluate these influences nor make practicalagronomic use of them.

The fact remains that biodynamic farming ispracticed on a commercial scale in many countriesand is gaining wider recognition for itscontributions to organic farming, food quality,community supported agriculture, and qualita-tive tests for soils and composts. From a practicalviewpoint biodynamics has proved to beproductive and to yield nutritious, high-qualityfoods.

References:

13) Steiner, Rudolf. 1993. Spiritual Foundationsfor the Renewal of Agriculture: A Course ofLectures. Bio-Dynamic Farming andGardening Association,Kimberton, PA. 310 p.

2) Lorand, Andrew Christopher. 1996. Biodynamic Agriculture A ParadigmaticAnalysis. The Pennsylvania State University,Department of Agricultural and ExtensionEduation. PhD Dissertation. 114 p.

3) Guba, E. 1990. The Alternative Paradigm Dialog.Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA.

4) Biodynamic Farming and GardeningAssociation25844 Butler RoadJunction City, OR [email protected]

5) Josephine Porter InstituteP.O. Box 133Woolwine, VA [email protected]

6) Brinton, William F. 1997. Sustainability ofmodern composting: intensification versuscosts & quality. Biodynamics. July-August. p.13-18.

7) Carpenter-Boggs, Lynne A. 1997. Effects ofBiodynamic Preparations on Compost, Crop,and Soil Quality. Washington StateUniversity, Crop and Soil Sciences. PhDDissertation. 164 p.

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 12

References: (continued)

8) Woods End Research LaboratoryRt. 2, Box 1850Mt. Vernon, ME 04352207-293-2456Contact: Dr. William BrintonE-mail: [email protected]: www.woodsend.org

9) Koepf, Herbert H., Bo D. Pettersson andWolfgang Schaumann. 1976. BiodynamicAgriculture: An Introduction. Anthro-posophicPress, Hudson, New York. 430 p.

10) Pieters, A. J. 1938. Soil-Depleting, Soil-Conserving, and Soil-Building Crops. USDALeaflet No. 165. 7 p.

11) Agri-Synthesis, Inc.P.O. Box 10007Napa, CA 94581707-258-9300707-258-9393 FaxContact: Greg [email protected]

12) Groh, Trauger, and Steven McFadden. 1997.Farms of Tomorrow Revisited: CommunitySupported Farms, Farm Supported Commu-nities. Biodynamic Farming and GardeningAssociation, Kimberton, PA. 294 p.

13) Schulz, D.G., K. Koch, K.H. Kromer, andU. Kopke. 1997. Quality comparison ofmineral, organic and biodynamiccultivation of potatoes: contents,strength criteria, sensory investigations,and picture-creating methods. p. 115-120. In: William Lockeretz (ed.) Agricultural

14) Production and Nutrition. TuftsUniversity School of Nutrition Scienceand Policy, Held March 19−21, Boston,MA.

15) Schulz, D.G., and U. Kopke. 1997. The qualityindex: A holistic approach to describe thequality of food. p. 47-52. In: William Lockeretz(ed.) Agricultural Production and Nutrition. Tufts University School of Nutrition Science andPolicy, Held March 19−21, Boston, MA

16) Granstedt, Artur, and Lars Kjellenberg. 1997.Long-term field experiment in Sweden: Effects of organic and inorganic fertilizers onsoil fertility and crop quality. p. 79-90. In: William Lockeretz (ed.) AgriculturalProduction and Nutrition. Tufts UniversitySchool of Nutrition Science and Policy, HeldMarch 19−21, Boston, MA.

17) Koepf, Herbert H. 1993. Research inBiodynamic Agriculture: Methods and Results. Bio-Dynamic Farming and GardeningAssociation, Kimberton, PA. 78 p.

18) Reganold, J.P. et al. 1993. Soil quality andfinancial performance of biodynamic andconventional farms in New Zealand. Science.April 16. p. 344−349.

19) Kolisko, E. and L. 1978. Agriculture ofTomorrow, 2nd Edition. Kolisko ArchivePublications, Bournemouth, England. 322 p.

20) Demeter Association, Inc.Britt Rd.Aurora, NY 13026315-364-5617315-364-5224 FaxContact: Anne [email protected]

Contacts:

Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Association25844 Butler RoadJunction City, OR [email protected]

Publisher of Biodynamics bi-monthly journal,Kimberton agricultural calendar, and extensiveselection of books.

Josephine Porter Institute for Applied Biodynamics, Inc.Rt. 1, Box 620Woolwine, VA 24185540-930-2463http://igg.com/bdnow/jpi/JPI makes and distributes the full range of BD

Preparations, as well as the BD Compost Starter®and the BD Field Starter®. Publisher of AppliedBiodynamics, a quarterly newsletter.

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 13

Contacts: (continued)

Pfeiffer Center260 Hungry Hollow RoadChestnut Ridge, NY 10977845-352-5020, Ext. 20845-352-5071 [email protected]

Educational seminars and training on biodynamicfarming and gardening.

Demeter Association, Inc. Britt Rd.Aurora, NY 13026315-364-5617315-364-5224 FaxContact: Anne [email protected]

Demeter® certification for biodynamic produce;publisher of The Voice of Demeter.

Michael Fields Agricultural InstituteW2493 County Rd. ESP.O. Box 990East Troy, WI 53120262-642-3303www.michaelfieldsaginst.org

Research and extension in biodynamics,publications, conferences and short courses.

Suggested Reading on Biodynamic Farming:

BDFGA (New Zealand). 1989. Biodynamics: NewDirections for Farming and Gardening in NewZealand. Random Century New Zealand, Auckland.230 p.

Castelliz, Katherine. 1980. Life to the Land: Guidelines to Bio-Dynamic Husbandry. Lanthorn

Press, Peredur, East Grinstead, Sussex, England. 72 p.

Groh, Trauger, and Steven McFadden. 1997. Farmsof Tomorrow Revisited: Community SupportedFarms, Farm Supported Communities. BiodynamicFarming and Gardening Association,Kimberton, PA. 294 p.

Lovel, Hugh. 1994. A Biodynamic Farm for GrowingWholesome Food. Acres, USA, Kansas City, MO. 215 p.

Koepf, Herbert H. 1989. The Biodynamic Farm: Agriculture in the Service of the Earth and Humanity.Anthroposophic Press, Hudson, New York. 248 p.

Koepf, Herbert H., Bo D. Pettersson and WolfgangSchaumann. 1976. Biodynamic Agriculture: AnIntroduction. Anthroposophic Press, Hudson,New York. 430 p.

Koepf, Herbert H. 1993. Research in BiodynamicAgriculture: Methods and Results. Bio-DynamicFarming and Gardening Association,Kimberton, PA. 78 p.

Pfeiffer, Ehrenfried. 1975. SensitiveCrystallization Processes − A Demonstration ofFormative Forces in the Blood. AnthroposophicPress, Spring Valley, NY. 59 p.

Pfeiffer, Ehrenfried. 1981. Weeds and WhatThey Tell. Bio-Dynamic Literature,Wyoming, RI. 96 p.

Pfeiffer, Ehrenfried. 1983. Bio-DynamicGardening and Farming. [collected articles, ca.1940 - 1961] Volume 1. Mercury Press, SpringValley, New York. 126 p.

Pfeiffer, Ehrenfried. 1983. Bio-DynamicGardening and Farming. [collected articles, ca.1940 - 1961] Volume 2. Mercury Press, SpringValley, New York. 142 p.

Pfeiffer, Ehrenfried. 1983. Soil Fertility: Renewal andPreservation. Lanthorn, East Grinstead, Sussex,England. 200 p.

Pfeiffer, Ehrenfried. 1984. Chromatography Appliedto Quality Testing. Bio-Dynamic Literature,Wyoming, RI. 44 p.

Pfeiffer, Ehrenfried. 1984. Bio-DynamicGardening and Farming. [collected articles, ca.1940 - 1961] Volume 3. Mercury Press, SpringValley, New York. 132 p.

Podolinsky, Alex. 1985. Bio-Dynamic AgricultureIntroductory Lectures, Volume I. GavemerPublishing, Sydney, Australia. 190 p.

Podolinsky, Alex. 1989. Bio-Dynamic AgricultureIntroductory Lectures, Volume II. GavemerPublishing, Sydney, Australia. 173 p.

Proctor, Peter. 1997. Grasp the Nettle: MakingBiodynamic Farming and Gardening Work. RandomHouse, Auckland, N.Z. 176 p.

Remer, Nicolaus. 1995. Laws of Life in Agriculture. Bio-Dynamic Farming and Gardening Association,Kimberton, PA. 158 p.

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 14

Suggested Reading on Biodynamic Farming: (continued)

Remer, Nikolaus. 1996. Organic Manure: ItsTreatment According to Indications by RudolfSteiner. Mercury Press, Chestnut Ridge, NY. 122 p.

Sattler, Fritz and Eckard von Wistinghausen. 1989. Biodynamic Farming Practice [English translation,1992]. Bio-Dynamic Agricultural Association,Stourbridge, West Midlands, England. 336 p.

Schilthuis. Willy. 1994. Biodynamic Agriculture: Rudulf Steiner’s Ideas in Practice. AnthroposophicPress, Hudson, NY. 11 p.

Schwenk, Theodore. 1988. The Basis of PotentizationResearch. Mercury Press, Spring Valley, NY. 93 p.

Steiner, Rudolf. 1993. Spiritual Foundations for theRenewal of Agriculture: A Course of Lectures. Bio-Dynamic Farming and Gardening Association,Kimberton, PA. 310 p.

Storl, Wolf D. 1979. Culture and Horticulture: APhilosophy of Gardening. Bio-Dynamic Literature,Wyoming, RI. 435 p.

Thompkins, Peter, and Christopher Bird. 1989. The Secrets of the Soil. Harper & Row, NewYork, NY. 444 p.

Suggested Reading on Biodynamic Compost:

Blaser, Peter, and Ehrenfried Pfeiffer. 1984. “Bio-Dynamic Composting on the Farm” and “How MuchCompost Should We Use?” Bio-Dynamic Farming andGardening Association, Inc., Kimberton, PA. 23 p.

Corrin, George. 1960. Handbook on Compostingand the Bio-Dynamic Preparations. Bio-DynamicAgricultural Association, London. 32 p.

Courtney, Hugh. 1994. Compost or biodynamiccompost. Applied Biodynamics. Fall. p. 11−13.

Courtney, Hugh. 1994. More on biodynamiccomposting. Applied Biodynamics. Winter. p. 8−9.

Courtney, Hugh. 1995. More on biodynamiccomposting - II. Applied Biodynamics. Spring. p. 4−5.

Koepf, Herbert H., B.D. Pettersson, and WolfgangSchaumann. 1976. Bio-Dynamic Agriculture: An

Introduction. The Anthroposophic Press, SpringValley, NY. 430 p.

Koepf, H.H. 1980. Compost − What It Is, How It IsMade, What It Does. Biodynamic Farming andGardening Association, Inc., Kimberton, PA. 18 p.

Pfeiffer, Ehrenfried. 1983. Soil Fertility, Renewal &Preservation (3rd Edition). The Lanthorn Press, EastGrinstead, England. 199 p.

Pfeiffer, Ehrenfried. 1984. Bio-dynamicGardening and Farming. [collected articles, ca.1940 - 1961] Volume 3. Mercury Press, SpringValley, New York. 132 p.

Pfeiffer, Ehrenfried. 1984. Using the Bio-DynamicCompost Preparations & Sprays in Garden, Orchard,& Farm. Bio-Dynamic Farming and GardeningAssociation, Inc., Kimberton, PA. 64 p.

Remer, Nikolaus. 1996. Organic Manure: ItsTreatment According to Indications by RudolfSteiner. Mercury Press, Chestnut Ridge, NY. 122 p.

Sattler, Friedrich, and Eckard v. Wistinghausen. 1992. Bio-Dynamic Farming Practice. Bio-Dynamic Agricultural Association, Stourbridge,England. 333 p.

E-mail Discussion Groups:

BDNOW! E-mail discussion groupwww.igg.com/bdnow

Send mail to [email protected], andtype SUBSCRIBE BDNOW YOUR NAME inthe body of the message.

BDNOW! E-mail archiveshttp://csf.colorado.edu/biodynamics/

BDA Discussion Forumwww.biodynamics.com/discussion

World Wide Web Links:

What is Biodynamics? by Sherry Wildfeuerwww.angelic-organics.com/intern/

biodynamics.html

Biodynamics: A Science of Life and Agriculture bySherry Wildfeurwww.twelvestar.com/Earthlight/issue06/

Biodynamics.html

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 15

World Wide Web Links: (continued)

The Nature of Forces by Hugh Lovelwww.twelvestar.com/Earthlight/issue07/

Nature%20of%20Forces.html

Rudolf Steiner: Biographical Introduction forFarmers by Hilmar Moorewww.biodynamics.com/bd/

steinerbioPAM.htm

Michael Fields Agricultural Institutewww.michaelfieldsaginst.org

Bulletin #1 (1989): Thoughts on Drought-Proofing your Farm: A Biodynamic Approach, byWalter Goldstein.www.steinercollege.org/anthrop/mfbull1.html

Bulletin #2 (1992): Issues in SustainableAgriculture: What are the Next Steps?, by CherylMiller.www.steinercollege.org/anthrop//mfbull2.html

Bulletin #3 (1992): Soil Fertility in SustainableLow Input Farming, by Dr. Herbert H. Koepf.www.steinercollege.org/anthrop//mfbull2.html

Biodynamic Research: An Overviewhttp://ekolserv.vo.slu.se/Docs/www/Subject/Biodynamic_farming/100-149/

141BIODYNA_RESEARCH-_AN_OVERVIE

Biodynamic Preparations at Sacred-Soil Sitehttp://sacred-soil.com/frlobdpreps.htm

Effects of Humic Acids and Three Bio-DynamicPreparations on the Growth of Wheat Seedlingswww.wye.ac.uk/agriculture/sarg/

postesa1.html

Influence of Bio-Dynamic and Organic Treatments onYield and Quality of Wheat and Potatoes: The Wayto Applied Allelopathy?www.wye.ac.uk/agriculture/sarg/

oral96.html

Biodynamic Research Institute in Swedenwww.jdb.se/sbfi/indexeng.html

Long-Term Field Experiment in Sweden: Effects ofOrganic and Inorganic Fertilizers on Soil Fertility andCrop Qualitywww.jdb.se/sbfi/publ/boston/boston7.html

UC-SAREP Newsletter Review: “Soil quality andfinancial performance of biodynamic andconventional farms in New Zealand.”www.sarep.ucdavis.edu/SAREP/NEWSLTR/ v6n2/sa-13.htm

Subtle Energies in a Montana Greenhouse by WoodyWodraskawww.biodynamics.com/bd/subtle.html

Rudolf Steiner Archive and e.Librarywww.elib.com/Steiner

Biodynamic and Organic Gardening Resource Sitewww.biodynamic.net

Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Associationwww.biodynamics.com

The Josephine Porter Institute of AppliedBiodynamicshttp://igg.com/bdnow/jpi

BDNOW! Allan Balliett’s Web Site www.igg.com/bdnow

American Biodynamic Associationwww.biodynamics.org

Rudolf Steiner Collegewww.steinercollege.org

Videos:

Bio-Dynamic Gardening: A How to Guide videowww.bestbeta.com/biodynamic.htm

Rudolf Steiner and the Science of Spiritual Realities,A Video Documentarywww.bestbeta.com/steiner.htm

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 16

Publishers −−−− Distributors of Biodynamic &Steiner Literature:

Acres, USA BookstoreP.O. Box 8800Metairie, LA 70011-8800504-889-2100504-889-2777 [email protected]

Anthroposophic Press3390 Route 9Hudson, NY 12534518-851 [email protected]

Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Association25844 Butler RoadJunction City, OR [email protected]

Rudolf Steiner College Bookstore9200 Fair Oaks Blvd.Fair Oaks, CA 95628916-961-8729916-961-3032 Faxwww.steinercollege.org/bstore/index.html

Woods End Research LaboratoryRt. 2, Box 1850Mt. Vernon, ME 04352207-293-2456Contact: Dr. William BrintonE-mail: [email protected]: www.woodsend.org/

Woods End publishes noteworthy manuals oncompost, soil organic matter, and green manures.

By Steve DiverNCAT Agriculture Specialist

February 1999

The ATTRA Project is operated by the National Center for Appropriate Technology under a grant fromthe Rural Business-Cooperative Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. These organizations do notrecommend or endorse products, companies, or individuals. ATTRA is located in the Ozark Mountainsat the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville at P.O. Box 3657, Fayetteville, AR 72702. ATTRA staffmembers prefer to receive requests for information about sustainable agriculture via the toll-freenumber 800-346-9140.

The electronic version of Biodynamic Farming &Compost Preparation is located at:http://www.attra.org/attra-pub/biodynamic.html

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 17

Objectives in Biodynamic and Conventional Farming*‘Biodynamic’ objectives ‘Conventional’ objectives

A. Organization

Ecological orientation, sound economy, efficientlabor input

Economical orientation, mechanization, minimizinglabor input

Diversification, balanced combination of enterprises Specialization, disproportionate development ofenterprises

Best possible self-sufficiency regarding manures andfeed

Self-sufficiency is no objective; importation offertilizer and feed

Stability due to diversification Programme dictated by market demands

B. Production

Cycle of nutrients within the farm Supplementing nutrientsPredominantly farm-produced manuring materials Predominantly or exclusively bought-in fertilizersSlowly soluble minerals if needed Soluble fertilizers and limeWeed control by crop rotation, cultivation, thermal Weed control by herbicides (cropping, cultivation,

thermal)Pest control based on homeostasis and inoffensivesubstances

Pest control mainly by biocides

Mainly home-produced feed Much or all feed bought inFeeding and housing of livestock for production andhealth

Animal husbandry mainly oriented towardsproduction

New seed as needed Frequently new seed

C. Modes of influencing life processes

Production is integrated into environment, buildinghealthy landscapes; attention is given to rhythm

Emancipation of enterprises from their environmentby chemical and technical manipulation

Stimulating and regulating complex life processesby biodynamic preparations for soils, plants, andmanures

No equivalent biodynamic preparations; use ofhormones, antibiotics, etc.

Balanced conditions for plants and animals, fewdeficiencies need to be corrected

Excessive fertilizing and feeding, correctingdeficiencies

D. Social implication; human values

National economy; optimum input : output ratioregarding materials and energy

National economy; poor input : output ratioregarding materials and input

Private economic : stable monetary results Private economic : high risks, gains at timesNo pollution Worldwide considerable pollutionMaximum conservation of soils, water quality, wildlife

Using up soil fertility, often erosion, losses in waterquality and wild life

Regionalized mixed production, more transparentconsumer-producer relationship; nutritional quality

Local and regional specialization, more anonymousconsumer-producer relation; interested in gradingstandards

Holistic approach, unity between world conceptionand motivation

Reductionist picture of nature, emancipated, mainlyeconomic motivation

* Koepf, H.H. 1981. The principles and practice of biodynamic agriculture. p. 237−250. In: B.Stonehouse (ed.) Biological Husbandry: A Scientific Approach to Organic Farming. Butterworths,London.

Appendix IAppendix IAppendix IAppendix I

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 18

Appendix II

Yield and Quality Under the Influence of Polar Opposite Growth Factors*

Earthly influence Cosmic InfluenceInclude among others:

Soil life, nutrient content of soil; water supply;average atmospheric humidity.

Light, warmth and other climatic conditions; andtheir seasonal and daily rhythms.

Vary locally according to:Clay, nutrient, humus, lime and nitrogen content ofthe soil; nutrient and water holding capacity;temperature and precipitation.

Sun; cloudiness; rain; geographical latitude; altitudeand degree of exposure; aspect of land; annualweather pattern; silica content of soils.

Normal influences on growth:High yields protein and ash content. Ripening; flavor; keeping quality; seed quality.

One-sided (unbalanced) effects:Lush growth; susceptibility to diseases and pests;poor keeping quality.

Low yields; penetrating or often bitter taste; fibrouswoody tissue; hairy fruit; pests and diseases.

Managerial measures for optimum effects:Liberal application of manure and compost treatedwith biodynamic preparations; sufficient legumes inrotation; compensating for deficiencies; irrigation;mulching.

Use of manures; no overfertilization; compensatingfor deficiencies; suitable spacing of plants; amountof seed used.

Use of Preparation No. 500 Use of Preparation No. 501

* Koepf, Herbert H., B.D. Pettersson, and Wolfgang Schaumann. 1976. Bio-Dynamic Agriculture:An Introduction. The Anthroposophic Press, Spring Valley, NY. p. 209.

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 19

Table 1. Traditional Agriculture Paradigm*

Ontology Epistemology MethodologyTraditional agriculture varies fromculture to culture, from region toregion, sometimes from tribe to tribewithin a culture and a region. It isoften a complex, living and dynamicweb of relationships, in which:

The traditional practitioner stands inrelationship to farming that ischaracterized by customs, rituals,generational wisdoms, tribal rules,superstitions, religious mores andoften other external values.

The traditional practitioner practicesoften rote patterns of seasonalpreparations, planting, cultivation,and harvesting based on conventionhanded by parents, tribal elders andconsistent with customs.

the earth is a living being within aliving universe;

Innovations are not continuallysought out and typically are slow inacceptance.

forces are at work in all that is bothanimate and inanimate;

Biodiversity is part of the traditionalpractices, stemming from thefarmer’s need for self-sufficiencywith as much variety as possible.

celestial rhythms play a role inhealth and prosperity;animals and humans are an integralpart of the wholethe farm is not considered a distinctbeing; andalthough these elements form awhole, the image of health is notnecessarily discernable

Table 2. Industrial Agriculture Paradigm*

Ontology Epistemology MethodologyIndustrial agriculture is an economicenterprise aimed at maximum short-term profit based on the mostefficient use of resources andmaximization of labor andtechnological efficiencies, in which:

The industrial practitioner stands inan exploitative business relationshipwith the “factory” farm. Observation, analysis and policydecisions are made on a bottom linebasis.

The industrial practitioner issuccessful to the extent thateconomic profit is maximized. Consequently, methods andpractices that lead to efficiencies oftechnology and labor are employed,assessed, and refined.

the earth is a relatively unlimitedsource of exploitable resources;

A technological framework shapesand restrains the thinking, problemidentification and analysis of thepractitioner.

Innovations are constantly soughtout, but evaluated on the basis oftheir contribution to added profitfrom the business enterprise; whichmay come from increased output ordecreased input.

substances are analyzed for amechanical/manipulative use;

Biodiversity is seen to beeconomically inconsistent withefficiency. Monocrop production isthe rule in the industrial paradigm.

the influences of natural conditionsare limited by technology;animals and humans are seen in thecontext of output of cash flow; andthe farm is often seen as a machineor “factory” (mechanicalperspective)

Appendix IIIAppendix IIIAppendix IIIAppendix III

// BIODYNAMIC FARMING & COMPOST PREPARATION Page 20

Table 3. Organic Agriculture Paradigm*

Ontology Epistemology MethodologyOrganic agriculture recognizes lifeas a complex ecosystem in which:

The organic practitioner stands in abenevolent appreciation of thecomplexity of the ecosystem andattempts to work within theframework of this ecosystemtowards sustainability (zero-sum netgains or losses).

The organic practitioner seeks asustainable subsistence, and restrictshis/her activities to non-exploitativepractices that “do no harm,” andthus that support ongoingsustainability.

nature, on earth, is a livingecosystem; albeit purely material;

Organic production does notemphasize biodiversity as anessential principle, and monocropproduction is common.

substances are analyzed forbalanced, ecological use;natural conditions are accepted andadjusted to;domestic animals are often excludedfor ethical values; andthe farm is seen as an integral part oflarger ecosystem (ecologicalperspective)

Table 4. Biodynamic Agriculture Paradigm*

Ontology Epistemology MethodologyBiodynamics is a complex living anddynamic (spiritual) system ofagriculture, in which:

The biodynamic practitioner standsin both a supportive and remedialrelationship to this complex, living,dynamic farm individuality**.

From the diagnostic-therapeuticrelationship follows that thebiodynamic practitioner’s activitiesare divided into supportive(preventative) maintenance andremedial (therapeutic) inteventions.

the earth is a living being in a livinguniverse, characterized by aspiritual-physical matrix;

Observation, diagnosis and therapydevelopment are the central themesof the practitioner’s relationshipwith the farm.

In practice, there is a strong focus onbalance, biodiversity, and plant andanimal immunity.

substances are carriers of forces thatcreate life;celestial rhythms directly effectterrestrial life;animals and humans emancipatefrom celestial rhythms; andthe farm is a living, dynamic,spiritual individuality** (spiritualperspective)

* Lorand, Andrew Christopher. 1996. Biodynamic Agriculture A Paradigmatic Analysis. ThePennsylvania State University, Department of Agricultural and Extension Eduation. PhDDissertation. 114 p.

** Where Lorand uses the terminology of Steiner (individuality), other authors instead use theterm organism