Baroque

-

Upload

d-cason -

Category

Art & Photos

-

view

80 -

download

0

Transcript of Baroque

Europe in the 17th Century

2

THE BAROQUE PERIOD IN ITALY

• Started in Rome– As a reaction to the Protestant Reformation– Also in reaction to Mannerism

• The Baroque period is also referred to as the Age of Expansion, especially in the arts.

• Patron Popes of the Baroque period included:– Paul V– Urban VIII– Innocent X

Roman Catholic Church supported Baroque art style in response to the Protestant Reformation (movement

to reform Catholic Church) – communication of religious themes with viewer's direct and emotional

involvement

Aristocracy adopted Baroque style to impress visitors and to express triumphant power and control

Figure 19-2 CARLO MADERNO, facade of Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, 1606–1612. 5

Baroque Art of 17th Century - ITALY

Much of Italian Baroque Art was aimed at propagandistically restoring Catholicism’s predominance and centrality/ used as teaching tool

17th century Italian Baroque Art and Architecture characteristics: dramatic/theatrical, grandiose scale, elaborate ornateness – all used to spectacular effect

Figure 19-2 CARLO MADERNO, facade of Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, 1606–1612. 6

Baroque Art of 17th Century - ITALY

Much of Italian Baroque Art was aimed at propagandistically restoring Catholicism’s predominance and centrality/ used as teaching tool

17th century Italian Baroque Art and Architecture characteristics: dramatic/theatrical, grandiose scale, elaborate ornateness – all used to spectacular effect

•Pope Paul V commissioned MADERNO to complete St. Peter’s in Rome, 1606

Figure 19-2 CARLO MADERNO, facade of Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, 1606–1612. 7

Baroque Art of 17th Century - ITALY

Much of Italian Baroque Art was aimed at propagandistically restoring Catholicism’s predominance and centrality/ used as teaching tool

17th century Italian Baroque Art and Architecture characteristics: dramatic/theatrical, grandiose scale, elaborate ornateness – all used to spectacular effect

•Pope Paul V commissioned MADERNO to complete St. Peter’s in Rome, 1606

•Maderno had to work with the preexisting structure/ his design for the façade was never fully executed

Figure 19-2 CARLO MADERNO, facade of Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, 1606–1612. 8

Baroque Art of 17th Century - ITALY

Much of Italian Baroque Art was aimed at propagandistically restoring Catholicism’s predominance and centrality/ used as teaching tool

17th century Italian Baroque Art and Architecture characteristics: dramatic/theatrical, grandiose scale, elaborate ornateness – all used to spectacular effect

•Pope Paul V commissioned MADERNO to complete St. Peter’s in Rome, 1606

•Maderno had to work with the preexisting structure/ his design for the façade was never fully executed

•Clergy rejected the original central plan (by Bramante and Michelangelo) because of association with pagan buildings like the Pantheon

Figure 19-4 Aerial view of Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, 1506–1666. 9

Figure 24-3 CARLO MADERNO, plan of Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, with adjoining piazza designed by GIANLORENZO BERNINI.

ITALY – St. Peter’s – Maderno and Bernini

•Pope Paul V commissioned Maderno to add 3 nave bays – symbolic distinction between clergy, laity and provided space for processions

Figure 19-4 Aerial view of Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, 1506–1666. 10

Figure 24-3 CARLO MADERNO, plan of Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, with adjoining piazza designed by GIANLORENZO BERNINI.

ITALY – St. Peter’s – Maderno and Bernini

•Pope Paul V commissioned Maderno to add 3 nave bays – symbolic distinction between clergy, laity and provided space for processions

•Lengthening nave pushed the dome back – this changed Michelangelo’s plan to have structure pulled together and dominated by the dome

Figure 19-4 Aerial view of Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, 1506–1666. 11

Figure 24-3 CARLO MADERNO, plan of Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, with adjoining piazza designed by GIANLORENZO BERNINI.

ITALY – St. Peter’s – Maderno and Bernini

•Pope Paul V commissioned Maderno to add 3 nave bays – symbolic distinction between clergy, laity and provided space for processions

•Lengthening nave pushed the dome back – this changed Michelangelo’s plan to have structure pulled together and dominated by the dome

•BERNINI designed the monumental piazza (plaza) in front of St. Peter’s

12

Figure 24-3 CARLO MADERNO, plan of Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, with adjoining piazza designed by GIANLORENZO BERNINI.

ITALY – St. Peter’s – Maderno and Bernini

•Pope Paul V commissioned Maderno to add 3 nave bays – symbolic distinction between clergy, laity and provided space for processions

•Lengthening nave pushed the dome back – this changed Michelangelo’s plan to have structure pulled together and dominated by the dome

•BERNINI designed the monumental piazza (plaza) in front of St. Peter’s

•Like welcoming arms of the church

•Oval shaped/ four rows of Tuscan columns make up two colonnades/ end with Classical temple fronts

13

15

Gianlorenzo Bernini

• He arrives in Rome in 1605.• Made a lot of sculptures for St Peters. • He also designed the piazza.

His sculpture David has 4 of 5 characteristic of Baroque sculpture:– Motion– A different way of looking at space. – The concept of time– Drama

17

Martyrdom of St Lawrence, 1614-15.

18

GIANLORENZO BERNINI, Baldacchino, Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy,

1624–1633. Gilded bronze, 100’ high.

Baroque Architecture & Sculpture

Italy

Bernini’s baldacchino serves both functional and symbolic purposes.

It marks Saint Peter’s tomb and the high altar, and it visually bridges human scale to the lofty vaults and dome above.

Figure 19-5 GIANLORENZO BERNINI, baldacchino, Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, 1624–1633. Gilded

bronze, approx. 100’ high. 19Figure 19-6 GIANLORENZO BERNINI, Scala Regia,

Vatican City, Rome, Italy, 1663–1666.

ITALY - BERNINI•Bernini decorates interior of St. Peter’s – Bronze Baldacchino provides dramatic, compelling presence at the crossing.

Figure 19-5 GIANLORENZO BERNINI, baldacchino, Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, 1624–1633. Gilded

bronze, approx. 100’ high. 20Figure 19-6 GIANLORENZO BERNINI, Scala Regia,

Vatican City, Rome, Italy, 1663–1666.

ITALY - BERNINI•Bernini decorates interior of St. Peter’s – Bronze Baldacchino provides dramatic, compelling presence at the crossing.

•Left: Spiral columns recall those of an ancient baldacchino over same spot in Old St. Peter’s/ bronze columns cast in five sections from wooden models/ bronze was attained from dismantled portico of the Pantheon

Figure 19-5 GIANLORENZO BERNINI, baldacchino, Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, 1624–1633. Gilded

bronze, approx. 100’ high. 21Figure 19-6 GIANLORENZO BERNINI, Scala Regia,

Vatican City, Rome, Italy, 1663–1666.

ITALY - BERNINI•Bernini decorates interior of St. Peter’s – Bronze Baldacchino provides dramatic, compelling presence at the crossing.

•Left: Spiral columns recall those of an ancient baldacchino over same spot in Old St. Peter’s/ bronze columns cast in five sections from wooden models/ bronze was attained from dismantled portico of the Pantheon

•Below: Royal stairway in Vatican City connects papal apartments to the portico and narthex of St. Peter’s/

22

Bernini, Damned Soul, 1619

Figure 19-7 GIANLORENZO BERNINI, David, 1623. Marble, approx. 5’ 7” high. Galleria Borghese, Rome. 23

Bernini – Expresses the Italian Baroque Spirit in Sculpture

It demands space around it/ the figure moves out into and partakes of the physical space that surrounds it and the observer

Figure 19-9 GIANLORENZO BERNINI, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome, Italy, 1645–1652. Marble, height of group 11’ 6”. 24

Bernini – Interior Niche of Cornaro Chapel

•Ecstasy of St. Teresa – 1645-52

The whole chapel became a theater for the production of this mystical drama

Figure 19-9 GIANLORENZO BERNINI, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome, Italy, 1645–1652. Marble, height of group 11’ 6”. 25

Bernini – Interior Niche of Cornaro Chapel

•Ecstasy of St. Teresa – 1645-52

The whole chapel became a theater for the production of this mystical drama

•Theatricality and sensory impact were useful vehicles for achieving Counter-Reformation goals

I saw in his hand a long spear of gold, and at the iron's point there seemed to be a little fire. He appeared to me to be thrusting it at times into my heart,

and to pierce my very entrails; when he drew it out, he seemed to draw them out also, and to leave me all on fire with a great love of God. The pain was so great, that it made me moan; and yet so surpassing was the sweetness of this excessive pain, that I could not wish to be rid of it. The soul is satisfied now with nothing less than God. The pain is not bodily, but spiritual; though the body has its share in it, even a large one. It is a caressing of love so sweet which now takes place between the soul and God, that I pray God of His goodness to make him experience it who may think that I am lying.

During the days that this lasted, I went about as if beside myself. I wished to see, or speak with, no one, but only to cherish my pain, which was to me a greater bliss than all created things could give me

26

•Bernini depicts spiritual and physical passion/ he was master at carving marble and showing variety of TEXTURES (clouds, cloth, flesh, feathery wings)

And between death and light, Bernini may be suggesting there may be moments of ecstasy worth saving and remembering.

Bernini was 71 years old when he began the work of the monument to the Blessed Ludovica Albertoni, and it was one of his last sculptures.

The work depicts Ludovica Albertoni on her deathbed, experiencing both mortal suffering and religious ecstasy, surrounded by putti, and awaiting to rise to the Holy Spirit.

Figure 19-9 FRANCESCO BORROMINI, facade of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Rome, Italy, 1665–1676. 32

Figure 24-11 FRANCESCO BORROMINI, plan of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Rome, Italy, 1638–1641.

Borromini – Italian Baroque ArchitectureChurch of St. Charles of the Four Fountains

•The interior is a variation on the centrally planned church

•Plan is hybrid of Greek cross and oval with long axis between entrance and apse

•Side walls move in flow that reverses the façade’s motion/ protruding columns/ coffered oval dome

USES THE DYNAMIC OVAL

33

Baroque Architecture

Borromini capped the interior of San Carlo with a deeply

coffered oval dome that seems to float on the light entering through windows

hidden at its base.

34

Italy

BORROMINI, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (view into dome),

Rome, Italy, 1638-1641.

Figure 19-12 FRANCESCO BORROMINI, Chapel of Saint Ivo, College of the Sapienza, Rome, Italy, begun 1642. 35

Figure 19-13 FRANCESCO BORROMINI, plan of the Chapel of Saint Ivo, College of the Sapienza, Rome, Italy, begun 1642.

Borromini – Chapel of St. Ivo

•Exterior: Borromini played concave against convex forms on upper level of chapel/ lower level already there when he began work on upper level/ pilasters seem to push the bulging forms outward/ buttresses above pilasters curve upward to brace the tall ornate lantern topped by a spiral

•Centralized star plan/ apses on all sides

Figure 19-14 Chapel of Saint Ivo (view into dome), College of the Sapienza, Rome, Italy, begun 1642.36

Borromini – Dome of Chapel of St. Ivo

Figure 19-15 ANNIBALE CARRACCI, Flight into Egypt, 1603–1604. Oil on canvas, approx. 4’ x 7’ 6”. Galleria Doria Pamphili, Rome.

37

CARRACCI – Drawn to the Classics (contrast to Caravaggio)•Flight into Egypt- 1603- Carracci created the “ideal” or “classical” landscape (from Venetian Renaissance works) showing all the props of a pastoral scene and tranquil mood/ the architectural structures capture idealized antiquity and the idyllic life/ figures are diminished in size to become part of the landscape

Figure 19-16 ANNIBALE CARRACCI, Loves of the Gods, ceiling frescoes in the gallery, Palazzo

Farnese, Rome, Italy, 1597–1601. 38

CARRACCI – Ceiling Fresco in the Palazzo Farnese Gallery

Loves of the Gods – interpretations of the varieties of earthly and divine love in classical mythology

This fresco simulates framed easel paintings for ceiling design – this technique is called “quadro riportato” – and it became fashionable for ceiling painting for several hundred years

Baroque frescoRenaissance fresco

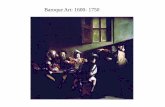

Caravaggio• The theatrical Baroque sculpture had its counterpart in

painting. • Caravaggio (Michelangelo de Merisi)• Portrayed dramatic movement, tenebrism, emotionally

charged subjects, and figures caught in time.• Tenebrism - exaggerated chiaroscuro. Translated as “dark

matter” it is often characterized by a small and concentrated light source in the painting or what appears to be an external”spotlight” directed as a very specific point in the composition.

Figure 19-17 CARAVAGGIO, Conversion of Saint Paul, Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del

Popolo, Rome, Italy, ca. 1601. Oil on canvas, approx. 7’ 6” x 5’ 9”. 41

CARAVAGGIO – One of the Most Noted Baroque Painters

•He disliked the classical masters and refused to emulate their work/style- was criticized for this

•He had a troubled personal life (info. from police records)

•Conversion of St. Paul – 1601

Figure 19-18 CARAVAGGIO, Calling of Saint Matthew, Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome, Italy, ca. 1597–1601. Oil on canvas, 11’ 1” x 11’ 5”. 42

CARAVAGGIO – Calling of St. Matthew – Theatrical Lighting

•Commonplace setting (bland street scene with plain building as backdrop)

Comparison

the Martyrdom of Saint Matthew

Figure 19-19 CARAVAGGIO, Entombment, from the chapel of Pietro Vittrice, Santa Maria in Vallicella,

Rome, Italy, ca. 1603. Oil on canvas, 9’ 10 1/8” x 6’ 7 15/16”. Musei Vaticani, Pinacoteca, Rome. 45

Entombment – Sums up CARAVAGGIO’S Distinctive Style

1603 – large-scale painting for Chapel of Pietro Vittrice in Rome

Caravaggio places the figures on a stone slab that seems to extend into the viewer’s space, suggesting that Christ will be laid directly in front of the viewer.

The theological implications are that Christ is being laid on the altar of a church, thus making real the doctrine of transubstantiation (the transformation of the Eucharistic bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ); Christ would thus be present during Mass, the Roman Catholic church service

46Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (detail), 1608.

48

David with the Head of Goliath, 1610.

CARAVAGGIO. Judith and Holofernes (c. 1598). Oil on canvas. Approx. 56 3⁄4” x 76 3⁄4”.

Figure 19-20 ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI, Judith Slaying Holofernes, ca. 1614–1620. Oil on canvas, 6’ 6 1/3” x 5’ 4”.

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.50

GENTILESCHI (Female) – “Caravaggista”

•Caravaggio’s style (combo. of naturalism and drama) became popular and appealed to patrons and artists

•Gentileschi was trained by her father (who was influenced by Caravaggio)

Judith and her Maidservant1613-14

Judith's maid Abra has gathered up the head of Holofernes in a basket, and they are preparing to leave his tent when they hear something which makes them stop and listen. The danger of their situation is implied by the position of the sword in Judith's hand: a few more inches and it will cut into her own white throat.

52

BAROQUE CEILING PAINTINGS (next three slides)

(1) Pietro da Cortona, Triumph of Barberini, Palazzo Barberini, Rome.(2) Giovanni Battista Gaulli, Triumph of the Name of Jesus. Il Gesu, Rome.(3) Fra Andrea Pozzo, Glorification of St. Ignatius, Sant’Ignazio, Rome.

Because of the considerable height and the expansive scale of most ceiling frescoes, the awe they produce was an opportunity to impress on worshipers the glory and power of the Catholic Church. Combined with Baroque theatricality, dynamism, and complexity, these frescos served the Counter-Reformation well.

Cortona’s Triumph of Barberini shows the family of Pope Urban VIII, in the radiant light of immortality.

Gaulli’s Triumph of the Name of Jesus offers the Roman Catholic faithful a glimpse of Heaven. To add more realism to the scene, Gaulli added painted figures on the stucco extensions that project outside the painting’s frame.

Fra Pozzo’s Glorification of Saint Ignatius gives the appearance that the roof has been lifted off of the church. Saint Ignatius was the founder of the Jesuit order, which was active in the Counter-Reformation.

Italy

Figure 19-22 PIETRO DA CORTONA, Triumph of the Barberini, ceiling fresco in the Gran Salone, Palazzo Barberini, Rome, 1633–1639.

53

DA CORTONA – Triumph of the Barberini

Figure 19-23 GIOVANNI BATTISTA GAULLI, Triumph of the Name of Jesus, ceiling fresco with stucco figures in the vault of the Church of Il Gesù, Rome,

Italy, 1676–1679. 54

GAULLI – Triumph in the Name of Jesus - 1676

Frescoes spanning church ceilings contributed to creating transcendent spiritual environments well suited to the needs of the Church in Counter-Reformation Italy

55

Figure 19-24 FRA ANDREA POZZO, Glorification of Saint Ignatius, ceiling fresco in the nave of Sant’Ignazio, Rome, Italy, 1691–1694.56

POZZO – Glorification of St. Ignatius - 1691

Fra Pozzo was lay brother of Jesuit order and master of perspective and ceiling decoration/ the church of Sant’ Ignazio was prominent in Counter-Reformation Rome because of its dedication to St. Ignatius, the founder of the Jesuit order

57

Spain

Baroque Painting

By the 17th century, the imperial age of the Spanish Habsburgs was over.

Struggling to maintain control of their empire, and keep Roman Catholicism dominant, both Philip III, and Philip IV continued to spend lavishly on art.

Baroque artists in Spain sought ways to move viewers and to encourage greater devotion and piety. They tended to depict scenes of death and martyrdom, and sought to instill strong emotional reactions in their viewers.

Spain was the proud home of two saints: Teresa of Avila and Saint Ignatius Loyola.

Figure 19-28 DIEGO VELÁZQUEZ, King Philip IV of Spain (Fraga Philip), 1644. Oil on canvas, 4’ 3

1/8” x 3’ 3 1/8”. The Frick Collection, New York. 58

VELAZQUEZ – Portraying Royalty, King Philip IV of Spain

•During a 3 month stay in Fraga, Philip ordered this painting

•Philip appears as military leader, in a red and silver campaign dress (but does not have a commanding presence)

59

Innocent X c. 1650; Galleria Doria-Pamphili, Rome

Figure 19-30 DIEGO VELÁZQUEZ, Las Meninas (The Maids of Honor), 1656. Oil on canvas,

approx. 10’ 5” x 9’. Museo del Prado, Madrid. 60

VELAZQUEZ – Art and Royal Life, Las Meninas

After visit to Rome from 1648 to 1651, he returned to Spain and painted his greatest masterpiece – Las Meninas (The Maids of Honor)/ it hung in Philip’s personal office

61

Here you see the artist looking at the viewer; in the background there appears to be a portrait of the king and queen, but it could be a mirror rather than a painting, and if so, the king and queen would then be standing near the viewer. Or, if the artist were looking at the entire scene with a mirror, then there is a sense of almost endless reflection back and forth.

DIEGO VELÁZQUEZ, Las Meninas (The Maids of Honor), 1656. Oil on canvas, approx. 10’ 5” x 9’. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Comparison

63