Appraisal, Coping, Health Status Etc.. e de Lazarus

-

Upload

mihai-sticlaru -

Category

Documents

-

view

225 -

download

0

Transcript of Appraisal, Coping, Health Status Etc.. e de Lazarus

-

8/3/2019 Appraisal, Coping, Health Status Etc.. e de Lazarus

1/10

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Copyright 1986 by the American Psychological Association, Inc.1986, VOI.50, No. 3, 571-579 0022-3514/86/$00.75

Appraisal, Coping, Health Status, and Psychological SymptomsSusan Folkman, R ichard S. Lazarus, R and J. Gruen , and A nita DeLongis

University of California, BerkeleyIn this study we examined the relation between personality factors (mastery and interpersonal trust),primary appraisal (the stakes a person has in a stressful encounter), secondary appraisal (options forcoping), eight forms of problem- and emotion-focusedcoping, and somatic health status and psycho-logical symptoms in a sample of 150 community-residing adults. Appraisal and coping processesshould be characterized by a moderate degree of stability across stressful encounters for them to havean effect on somatic health status and psychological symptoms. These processes were assessed in fivedifferent stressful situations that subjectsexperienced n their day-to-day ives. Certain processes (e.g.,secondary appraisal) were highly variable, whereas others (e.g., emotion-focused forms of coping)were moderatelystable. We entered mastery and interpersonal rust, and primary appraisal and copingvariables (aggregated over five occasions), into regression analyses of somatic health status and psy-chological symptoms. The variables did not explain a significantamount of the variance in somatichealth status, but they did explain a significantamount of the variance in psychologicalsymptoms.The pattern of relations ndicated hat certain variableswere positivelyassociated and others negativelyassociated with symptoms.

Curren t theory and research on the rela tion between stressfulevents and indicators of adaptational status such as somatic healthand psychological symptoms reflect the belief that this relat ionis mediated by coping processes. Presumably, these coping pro-cesses are a t least moderate ly stable across diverse stressful sit-uations, and so, over the long term, they affect adaptational out-comes.

The task of identifying he mechani sms through which copingmay be related to outcomes has been approached from severaldirections. Wheaton (1983) and Kobasa (1979), for example,focused on characteristics of the personality that are antecedentsof coping; Wheaton considered fatalism and inflexibility, andKobasa considered hardiness. The assumption underlying thisapproach is that personality characteristics dispose the personto cope in cert ain ways that ei ther impa ir or facilitate the variouscomponents of adaptational status. However, there is little evi-dence that these personality characteristics do in fact significantlyinfluence actual coping processes (Cohen & Lazarus, 1973;Fleishman, 1984).

A second approach is to assess the way in which a personactually copes with one or more stressful events. Billings andMops (1984), for example, assessed the ways in which individua lscoped with a single recent stressful event; they found such copingto be related to depression. The assumpti on underlying his ap-proach is that the way in which a person copes with one or mor estressful events is representative of the way he or she copes withstressful events in general.

This research was supported by a grant from the MacArthur Foun-dation.Anita DeLongis s now at the Institute for Social Research, Universityof Michigan, Ann Arbor.Correspondence concerning his article should be addressed to SusanFolkman, Department of Psychology, Universityof California, Berkeley,Berkeley, California 94720.

571

A third app roach is to focus on characteristics of the stressfulsituat ions that people experience. Studies in which the researchersassess how people cope with situations in which they have nocontrol over the outcome illustrate this approach (e.g., Shanan,De-Nour, & Garty, 1976). The assumption is that people whoare repeatedly in uncontrollable situations experience helpless-ness, become increasingly passive in their coping efforts, andultimately experience demoralization and depression. Situationshave also been characterized by the nature of the psychologicalthreat they pose. Examples include studies of evaluation anxiety(e.g., Krohne & Laux, 1982) and loneliness (e.g., Jones, Hobbs,& Hockenbury , 1982; Schultz & Moore, 1984; Solano, Batten,& Parish, 1982), in which researchers evalua te the ways in whichpeople cope with situations that t hrea ten thei r self-esteem. Inthese instances any relation found between coping and long-termoutcome is probably due to the person's repeatedly experiencingstressful situations that t ouch on a pa rticular area of vulnerability,insofar as a single, isolated instance of poor coping is not likelyto have long-term implications for health and well-being.

A fourth and more sophisticated approach, which is illust ratedby the work of Pearl in and Schooler (1978), is to conside r therelative contributio ns of personality characteristics and copingresponses to psychological well-being. Pearli n and Schooler eval-uated personality characteristics (mastery, self-esteem, and self-denigration) and the ways in which people cope with chronicrole strains in relation to the amelioration of distress in each offour role areas: marriage, parenting, household economics, andoccupation. They found that personality characteristics and cop-ing responses had different effects that were relative to each other,depending on the nature of the stressful conditions. Personalitycharacteristics were more helpful to the stressed person in thoseareas in which there was little opportunity for control, such asat work, whereas coping responses were more helpful in areasin which the person's efforts could make a difference, such as inthe context of marriage.

-

8/3/2019 Appraisal, Coping, Health Status Etc.. e de Lazarus

2/10

57 2 FOLKMAN, LAZARUS, GRUEN, AND DELONGISIn ou r research, we draw on al l of these approaches within

the framewo rk of a co gnitive theory o f psychological stress, whichis descr ibed in the fol lowing sect ion. We include in our analys isantecedent personali ty factors , actual coping processes repor tedby the same person in f ive different stressful encounters , and theappraised character is t ics of those encounters . O ur g oal is to eval-uate the con tr ibutio n of each of these factors to ad aptat ion alstatus.

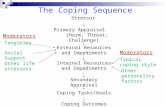

S t r e s s a n d C o p i n g T h e o r yThe cognit ive theory of psychological s tress and coping on

which this research is based (see Lazarus & Fo lkman , 1984b) istransact ional in that the person and the environment are viewedas being in a dynamic, mutually reciprocal , bidirect ional re la-t ionship. S tress is conceptualized as a relat ionship between theper son and the envi r onment tha t i s appr a i sed by the pe r son astaxing or exceeding his or her resources and as endanger ing well-being. The theory identif ies two processes, cognit ive appraisaland coping, as cr i tical mediators of s tressful person-environmentrelat ionships and their immediate and long- term outcomes.

Cognit ive appraisal is a process through which the personevaluates whether a par t icular encounter with the environmentis re levant to his or her well-being and, i f so, in w hat way. Thereare two kind s of cognit ive appraisal : pr ima ry and secondary. Inpr imary appraisal , the person evaluates whether he or she hasanything at s take in this encounter. F or example, is there potentia lhar m or benef i t to self -es teem? Is the heal th or well-being of aloved one at r isk? A range of personality characteristics includin gvalues, comm itmen ts , goals , and bel iefs abou t on self and theworld helps to define the stakes that the p erson identif ies as havingrelevanc e to well-bein g in specific stressful transac tions. In sec-onda ry appraisal the person ev aluates what , i f anything, can bedone to over come or p revent ha r m or to impr ove the pr ospec tsfor benefit. Various coping options are evaluated , such as changingthe s i tuat ion, accepting i t, seeking more information , or holdingback f rom acting impuls ively.Coping refers to th e p erson' s cognit ive and b ehavioral ef for tsto manage ( reduce, minimize, master , or tolerate) the internaland ex te r na l demands o f the pe r son- envi r onm ent t r ansac t ionthat is appraised as taxing or exceeding the person ' s resources .Coping has two major functions: deal ing with the probl em thatis causing the dis tress (problem-focu sed coping) and regulat ingemot ion (emotion-focused coping) . (For a review of this dis t inc-t ion in coping research, see Folkman & L azarus , 1980; Laz arus& Folk man, 1984b.) Previous invest igat ions (e .g. , Folkm an &Laza rus, 1980, 1985) have shown that peo ple use bot h forms o fcoping in virtually every type o f stressful encounter. Several formsof problem - and emotion-foc used coping have been identif ied inprevious research (Aldwin, Folkman, Schaefer , Coyne, & La-zarus , 1980; Folk man & Lazarus , 1985; Folkm an, Lazarus ,Dunkel-Schetter , DeLongis , & Gruen, in press) . For example,problem-focused forms of coping include aggress ive interpersonalef forts to a l ter the s i tuat ion, as well as cool , ra t ional , del iberateef forts to pro blem solve, and emotio n-focused forms o f copinginclude dis tancing, self -controll ing, seeking social suppo r t , es-cape-av oidan ce, accepting responsibi l i ty, and posi t ive reap-praisal.

Cognit ive appraisal and coping are t ransact ional var iables , bywhich we mean tha t they r e fe r no t to the envi r onment or to theperson alone, but to the integrat ion of both in a given transact ion.An appraisal of threat is a function of a specific set of environ-mental cond it ions that are app raised by a par t icula r person withparticu lar psychological characteristics. Similarly, coping consistsof the par t icula r thoughts and behaviors a person is us ing tomanage the demands of a pa r t i cu la r pe r son- envi r onment t r ans -act ion that has relevance to his or her well-being.

In anoth er repor t (Fo lkman et a l . , in press) in which the s ingles tressful encounter and i ts immediate outcome was the unit ofanalys is , we exam ined the relat ions amo ng cognit ive appraisal ,coping, and the im med iate outcom es of s tressful encounters. W eused an intraindivid ual analys is to com pare the sa me person ' sappraisal and coping processes over a var iety of s tressful en-counters in order to unders tand the fun ctional re lat ions amon gthese var iables . The f indings showed that ty pe o f coping var ieddepending on what was at s take (pr imary appraisal) and whatthe coping options were ( secondary appraisal) . For example, whenpeople fel t their self -esteem was at s take, they used more con-f rontive coping, self -control , escape-avoidance, and acceptedmore responsibility than when self-esteem was not at stake; whena goal a t work was at s take, they used more planful problemsolving than they used in encoun ters that did not involve thiss take. P lanful problem solving was also used m ore in e ncountersthat peo ple appraised as capable o f being changed for the bet ter ,whereas dis tancing was used more in e ncounters tha t were notamenab le to change. The f indings also indicated that coping wasrelated to the quali ty of encounter outcomes, b ut app raisal wasnot . Confrontive coping and dis tancin g were associated with out-comes the subject found unsat is factory, and planful problemsolving and posi t ive reappraisal were associated with sat is factoryoutcomes.

T h e P r e s e n t R e s e a r c hIn this s tudy we shif t our a t tent ion away f rom the relat ions

among appraisal and coping processes and their shor t- term out-comes that are viewed within th e con text of a specif ic s tressfulencounter. We focus instead on the relatio n between (a) apprai saland coping processes that are aggregated across s tressful en-counters and (b) indicators of long- term adaptat io nal s ta tus .

Appra isal and coping processes should be c haracter ized by atleas t a modera te degree of s tabil i ty across s tressful encounters i fsuch processes are to have an impa ct on ad aptat io nal s ta tus . Forexample, a coping s trategy such as confrontat ion , which involvesa high degree of mob ilization , is not likely to affect somatic hea lthunless i t is used by the person over and over again, and, s imilar ly,a s ingle act of self -blame is not l ikely to result in low morale ordepress ion; man y ins tances would be required (La zarus & Folk-man, 1984a).

The issue of s tabil i ty in the ways in which people appraise andcope with diverse s tressors remain s relat ively unadd ressed at theempir ica l level . Several invest igators found that s i tuat ional ap -praisals of control were not re lated to disposi t ional bel iefs abou tcontrol (Folkman, Aldwin, & Lazarus , 1981; Nelson & Cohen,1983; Sand ier & Lakey, 1982), suggesting that situ ation al ap-praisals of control may be more var iable than s table . With respectto coping, the evidence to date suggests that coping ef forts across

-

8/3/2019 Appraisal, Coping, Health Status Etc.. e de Lazarus

3/10

APPRAISAL, COPING, HEALTH, AND SYMPTOMS 573diffe ren t types of s i tua t ions a re mo re var iab le than s tab le . Men-aghan (1982) found grea te r supp ort fo r spec if ic i ty o f cop ing ac -cord ing to ro le a reas than for genera l ized coping s ty les ac rossro le a re a s in h e r a n a ly s i s o f th e C h ic a g o P a n e l Da ta (Me n a g h a n ,1982; Pear l in , L ieberman, Menaghan , & Mullah , 1981; Peaf l in& Schoole r , 1978) . Fo lkman and Lazarus (1980) found tha t peo-p le were more var iab le than s tab le in the ir re la t ive use of p rob lem -a n d e m o t io n - fo c u s e d c o p in g a c ro s s a p p ro x ima te ly 1 3 s t re s sfu lencounte rs . In a la te r ana lys is o f these da ta (Aldw in e t a l ., 1980) ,in wh ic h e ig h t ( r ath e r th a n two ) fo rms o f c o p in g we re e v a lu a te d ,p e o p le we re fo u n d to u s e c e r t a in fo rm s o f c o p in g s u c h a s w i s h fu lth in k in g a n d p o s i t iv e r e a pp ra i s a l m o re c o n s i s t e n tly th a n o th e rforms such as se l f-b lame. An except ion to th is pa t te rn was re -p o r t e d b y S to n e a n d Ne a le (1 9 8 4) , wh o fo u n d th a t p e o p le t en d e dto be cons is ten t in coping with s imila r types of s t ress on a day-to-day bas is ; however , they d id no t eva lua te cons is tency withrespec t to d iverse sources o f s t ress.

The l imited ava i lab le ev idence sugges ts tha t appra isa l andc o p in g p ro ce s s es ma y n o t b e c h a ra c te r i z e d b y a h ig h d e g re e o fs tab il i ty . Ye t theore t ica l ly the re sh ould be a t leas t some s tab i l i tytha t is due to the in f luence of pe rsona l i ty charac te r is t ic s such asthose s tud ied by Whea ton (1983) , Kobasa (1979) , and Pearl inand h is co l leagues (Men aghan , 1982; Pear l in e t a l ., 1981; Pear l in& Schoole r , 1978) . S tab i l i ty could a lso der ive from the personb e in g in th e s a me k in d s o f e n v i ro n me n ta l c o n d i t io n s (S to n e &Neale, 1984).

Ou r p u rp o s e i s t o e v a lu a te th e e x te n t to wh ic h p e o p le a res t a ble in th e i r p r ima ry a n d s e c o n d a ry a p p ra i s a l a n d c o p in g p ro -cesses ac ross d iverse s t ress fu l encounte rs , and to de te rmine theex ten t to which these processes , apar t f rom the persona l i ty char-ac te r is t ic s tha t might in f luence them, make a d iffe rence in ad-ap ta t iona l s ta tus .

M e t h o dS a m p l e

The sam ple consisted of 85 mar ried couples living in Contra CostaCounty, California, with at least one child at home. Th e sample wasrestricte d to women betw een the ages of 35 and 45; their husbands, whoseages were not a cri terion for eligibility, were between th e ages of 26 and54. In order to provide comparability with our previous community-residing sample (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980), the people selected for thestudy were Caucasian, prim arily Protes tant or Catholic, and had at leastan eighth-grade education, an above-marginal fami ly inco me ($18,000for a family of four in 1981), and were not bedridden.Qualifi ed couple s were identified throu gh random -digi dialing. Pro-spective subjects rece ived a letter expla ining the study, then a tel ephonecall from a project interviewer who answered questions and requested ahom e interview. O f the qualified couples wh o received letters, 46% agreedto be in the study. The acceptance rate was comparable with th at o f ourprevious field study, and not unexpected given that both members of thecouple had t o be willing to participate. The average age of the wom enwas 39.6, and that of the men w as 41.4. Th e average subject bad 15.5years of education, and the median family income was $45,000. Eighty-four percent of the m en and 57% of the women were employed for pay.People who refused t o be in th e study differed from those w ho participatedonly in years of education (a mean of 14.3 years). Ten couples droppedout o f the study; this was an attrition rate o f 11.8%. The data from thesecouples were excluded from the analysis; this yielded a final sample of75 couples. Interviews were conducted in tw o 6-m onth waves from Sep-tember 198t through August 1982.

P r o c e d u r e sSubjects were interviewed in their homes once a m onth for 6 months.Husbands and wives were inter viewed separately by differe nt interviewerson the same day and, if possible, at the sam e time. Inte rview s lasted ab out189 to 2 hours. The data reported in this article were gathered during thesecond th rough sixth interviews.

M e a s u r e sThe second through sixth interviews were devoted primarily to thereconstruction of the m ost stressful event that th e subject had experiencedduring the previous week. The interviewer used the Stress Interview, astructured protocol developed for this study, to elicit information aboutmultiple facets of the event. W e drew upon questions about th e subject'scognitive appraisal of the stressful encoun ters that w ere reported, an dthe ways in which the subject tried to manage the demands of thoseencounters. These questions are described in the paragraphs that follow.Additi onal questionnaires, which ar e also described in the paragraphsthat follow,were administered in orde r to assess personality characteristicsand adaptational status.Antecedent variables includ ed the personality traits of mastery, inte r-

personal trust, self-esteem, values and commitments, and religious beliefs.These variables were selected on both theoretical (e.g., Folkman, Schaefer,& Lazarus, 1979; Lazarus & DeLongis, 1983; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984a,1984b) and em piric al (e.g., Pearlin & Sehooler, 1978 ; Rotter, 1980)grounds.Mastery was measured during the second interview with a scale de-veloped by Pearlin and his associates (el. Pearlin & Schooler, 1978) foruse with a community-residing adult sample. Th e scale assesses the exten tto which on e regards one's life chances as being under one's control incontrast to being fatalistically determined. Subjects responded on a 4-point Likert scale about the extent to which they agreed or disagreedwith the following statements:

I have little control over the things that happen to m e.There is really no way I can solve some of the problems I have.There is little I can do to change many of the impo rtant things inmy life.I often feel helpless in dealing with the problems of life.Sometimes I feel that I 'm being pushed aro und in life.What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me.I can do just about anything I really set my m ind to do.

In this study the internal consistency o f the scale (alpha) was .75.Interpersonal trust was measured during the third interview with asubstantially shortened version of Rotter's (1980) Interpersonal Trust Scale.Subjects responded on a 5-poi nt Likert scale about th e extent to whic hthey agreed or disagreed w ith the following statemen ts:

In dealing with strangers o ne is better off to be cautious until theyhave provided evidence that they are trustworthy.Most people can be coun ted on t o do what they say they will do.The judiciary is a place where we can all get unbiased treatment.It is safe to believe that in spite of what people say, mo st people areprimarily interested in their own welfare.Most people would be horrified if they knew how much news thatthe pub lic hears an d sees is distorted.In these competitive times one has to be alert o r someone is likelyto take advantage of you.Most salesmen are honest in describing their products.Most repairm en will not overcharge even if they think you are ig-norant of their specialty.

-

8/3/2019 Appraisal, Coping, Health Status Etc.. e de Lazarus

4/10

57 4 FOLKMAN, LAZARUS, GRUEN, AND DELONGISMost elected public officials arc really sincere in their campaignpromises.

The alpha for the version of the Interpersonal Trust Scale used in thisstudy was .70.

Three other personality characteristics were assessed, but were notincluded in th e analysis: self-esteem, values and comm itme nts, and re-ligious beliefs. Self-esteem was measured with the Rosenberg (1965)Self-Esteem Scale duri ng the secon d interview. Prelim inary analyses in-dicated that the m easures of self-esteem and mastery were highly corre-lated (r = .65) and showed virtually the same pattern o f relations withthe other variables in the system. Because of i ts redundancy with masteryand i ts potential overlap with the self-esteem comp onent of depression,which is inclu ded in the m easure of psychological symp toms, self-esteemwas not included in further analysis.

Values and com mitm ents an d religious beliefs were also measured withscales developed for this study. The Values and C om mit men ts Scale wasadopted from Buhler's (1968) work in order to assess the qualities orthings that an individual might value or feel committed to. A factoranalysis of the 70-item scale produce d eigh t subscales: self-actualization,success, adheren ce to authority, comf ort and security, self-indulgence,traditional family life, mastery and challenge, and accepting hardship.Religious beliefs were m easu red wi th a 17-item checklist. A fa ctor analysisof this questio nnaire pro duce d thre e subscales: religiosity, athe ism, an dfatalism. Values and com mitm ents a nd religious beliefs were not includedin the analysis because preliminary evaluation indicated that they wererelated neither to the outcom e variables nor to an y other variables in thesystem.Primary appraisal (of what was at stake) was assessed as part of theStress Questionnaire, which was administered in interviews 2-6. I t wasmeasured w ith 13 i tems that described various stakes people might havein a specific encounter. Subjects indicated the ex tent to whic h each stakewas involv ed on a 5-po int Lik ert scale. Two subscales, previously identifiedthro ugh fac tor analysis (Folkm an et al., in press), were used in th is study:self-esteem, a six-item scale tha t comp rised ite ms such as th e possibilityof "losing the affection of someone im porta nt to you," "losing your self-respect," and "appearing incom petent" (alpha averaged over f ive admin-istrations was .78); and concern for a loved one's well-being, a three-it emscale that included the possibilities of "harm to a loved one's health,safety or physical well-being," " a loved one[ 's] havin g difficulty gettin galong in the world," and "ha rm to a loved one's emotional well-being"(a = .76). The remaining i tems ("n ot achieving an im portant goal atyour job or in your work," "h arm to your own health, safety, or physicalwell-being" "a strain on your f inancial resources" and "losing respectfor someo ne else") were' used as individu al items in the analysis.Secondar y appraisal (of coping options) was measured with four i temsfrom the Stress Questionnaire. Subjects indicated on a 5-point Likertscale the extent to which the si tuation was one "th at you could changeor do something about," "that you had to a ccept " "i n which you neededto know more before you could act ," and "in which you had to holdyourself back from doing what you w anted to do "Coping was assessed as pa rt of the Stress Question naire with the 66-item revised Ways of Coping Checklist (Folkman & la zaru s, 1985; Folk-man et al. , in press) . The checklist contained a broa d range of copingand behavioral strategies that people use to manage internal and externaldem ands in a stressful encounter. A facto r analysis, which we describedin a prior report (Folkman et al. , in press), produced eight scales: con-frontive coping (e.g. , "stood m y ground and fought for what I wante d""tried to get the person responsible to change his or her min d" "I expressedanger to the person(s) who caused the pro bl em "; , = .70); distancing(e.g. , "went on as if nothing had happen ed," "did n' t let i t get to m e- -refused to think about i t too much" "tr ied to forget the whole thing""ma de l ight of the si tuation; refused to get too serious about i t"; a =.61); self-control(e.g., "I tr ied to keep my feelings to myself ," "kept othersfrom knowing how bad things were," "tr ied n ot to burn my bridges, but

leave things open somewhat"; a =.70 ); seeking social support(e.g., "talke dto someone who could do something concrete about the problem ," "ac-cepted sympathy and understanding from someone"; a = .76); acceptingresponsibility (e.g., "criticized or lectured myself," "realized I broughtthe problem on myself" "I apologized or did something to make up";a = .66); escape-avoidance (e.g., "wished that the situation would goaway or somehow be over with," "tr ied to make myself feel better byeating, drinking, smoking, using drugs or medications, etc.," "avoidedbeing with people in general" "slept more than usual"; a = .72); planfulproblem solving (e.g. , "I knew wh at had to be done, so I doubled m yefforts to m ake things work" "I m ade a plan of action and followed i t ""came up w ith a couple of different solutions to the p roblem" ; ~ = .68);and positive reappraisal (e.g., "changed or grew as a person in a goodway," "I came out of the experience better than I went in " "foun d newfaith," "I prayed"; a = .79).

T he adaptational status (outcome) variables were extent o f psycho-logical symptoms and somatic health status. Psychological symptom -atology was assessedwith the Hopkins Sympt om Checklist (HSCL), w hichwas developed by Derogatis and his colleagues (Derogatis, Lip man, Covi,Rickels, & Uhle nhu th, 1970; Derogatis, Lipm an, Rickels, U hlen hut h, &Covi, 1974). It is a 58-item scale that ha s demo nstrate d a sensitivity tolow levels of symp toms in n orm al population s (Rickels, Lipm an, Garc ia,& Fisher, 1972; Uhle nhu th, Lipm an, Baiter, & Stem , 1974) an d a relativelyhigh stability over an 8 -month period (tes t-retest coefficient app roximately.70) in a comparable population (Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer, & Lazarus,1981). The HSCL was completed by subjects during the week beforetheir final interview. It contains five subscales, bu t becau se of high in-tereorrelations among the subscales, and a similar pattern ing of relationsbetween the subscales and the oth er variables in the study, we used thesum of ratings as a single score. Somatic health was assessed in the sixthinterview with a self-report questionnaire adopted with minim al m odi-fication from th at used by the Hum an Population Laboratory (Belloc &Breslow, 1972; Belloc, Breslow, & Hoch stim , 1971). It cont ain s que stion sabout a wide variety of chronic conditions and specific somatic sym ptoms,as well as disability in w orking, eating, dressing, and m obility (cf. De-Longis, Coyne, Dak of, Folkm an, & Lazarus, 1982). Subjects were assignedto o ne of four levels of health (disabled, chronically ill, symptom atic, an dhealthy), according to their m ost serious health problem, with low scoresindicating poor health. I tems that pertained to the person's overall energylevel were excluded from the scoring becau se of their overlap with psy-chological sym ptoms. T he scale has been found to be ac ceptably reliableand valid in comparison with medical records (Andrews, Schonell, &Tennan t, 1977; Meltzer & Hochstim , 1970).

Two addit ional measures of adaptational status--th e Center for Epi-demioiogic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) and theBradb urn Morale Scale (Bradburn, 1969; Bradb urn & Caplovitz, 1965)---were also used in the study. These scales were highly correlated with theHSCL (rs = .72 and -.56, respectively) and with each other (r = -.74),and showed a similar patterning of correlation with the other variablesin the system. Because of their apparent redunda ncy with the HSCL, theCES-D and the Brad burn M orale Scale were not included in this analysis .

R e s u l t sF o u r s e t s o f v a r i a b l e s - - p e r s o n a l i t y c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s ( m a s t e r y

a n d i n t e r p e r so n a l t ru s t ), p r i m a r y a p p r a i s al ( m e a s u r e d w i t h t h es i x s t a k e s i n d i ce s ) , s e c o n d a r y a p p r a i s a l ( m e a s u r e d w i t h t h e f o u ri n d i c e s o f c o p i n g o p t i o n s ) , a n d c o p i n g ( m e a s u r e d w i t h t h e e i g h tc o p i n g s c a l e s ) - - w e r e u s e d i n t h e a n a l y s i s i n o r d e r t o e x p l a i ns o m a t i c h e a l t h s t a t u s a n d p s y c h o l o g i c a l s y m p t o m s . P a i r e d t t es t sw e r e u s ed t o d e t e r m i n e w h e t h e r t h e r e s p o n s e s o f h u s b a n d s a n dw i v e s d i f f e re d w i t h i n e a c h o f t h e f o u r s e t s o f p r e d i c t o r v a r i a b l e s .W e d e t e r m i n e d s i gn i fi c an c e w i t h t h e D u n n M u l t i p l e C o m p a r i s o nt e s t. T h e r e w e r e n o s i g n i f i c a n t g e n d e r d i f fe r e n c e s i n p e r s o n a l i t y

-

8/3/2019 Appraisal, Coping, Health Status Etc.. e de Lazarus

5/10

APPRAISAL, COPING, HEALTH, AND SYMPTOMS 57 5character ist ics , secondary appraisal , or coping. The re was a s ig-nif icant dif ference in pr i mar y appraisa l because of two s takes:wives endorsed concern for a loved one ' s well-being more thandid their husbands , and husban ds endorsed concern about a goalat work m ore than did their wives. Given the absence of genderdif ferences in three of the fou r sets of var iables and the smallgender dif ference in th e four th set, responses were pooled for theanalyses to be repor ted .Stability

The s tab il i ty o f each of the pr imar y and secondar y appra i sa land coping var iables was es t imated with auto correlat ions acrossthe f ive measureme nt occas ions , as shown in Table 1.

The mean au tocor r e la tions of the pr imar y appr a i sa l o f s takesindices ranged f r om . 12 to .37, the seco ndary appraisal indicesf ro m. 12 to .24, and the coping scales f rom . 17 to .47.Bivariate Correlations

The pr ima ry appraisal , secondary appraisal , and coping scoreswere aggregated across f ive occas ions , and a mean was calculatedfor each var iable . The intercorrelat ion s within each set of pre-dictor var iables , including mastery and interpersonal t rus t, whichwere assessed one t im e only, are shown in Table 2.

The cor relat ions between the personali ty var iables (masteryand interpersonal t rus t) and appraisal and coping ranged f rom.01 to .37; most of the rs were below .20.

The cor relat ions between the four sets of predicto r var iablesand the two o utcom e var iables are shown in Table 3. Eleven ofthe 20 cor relat ions with soma tic heal th s ta tus were s ignif icant;these were al l weak to moderate , and none exceeded .30.

There w ere 17 significant relations out o f 20 with psychologicalsympto ms, 10 of these exceeding .30. Both o f the personali tyvar iables, a l l of the pr i mar y app raisal var iables, and al l but oneof the cop ing var iables were s ignificantly cor related w ith sym p-toms. Th e secondary appraisal var iables showed weaker relat ionswith psychological symptoms; only two of the four coping optionsshowed s ignif icant cor relat ions .Multiple Regression Analyses

Somatic health. In hierarchical regress ion analyses , four setsof predicto r var iables (personali ty var iables , pr im ary appraisal ,seconda ry appraisal , coping) were regressed on somatic heal ths tatus. O ne of the s takes scales , concern with ow n ph ysical well-being, was el iminated f rom the set of pr imary appraisal var iablesbecause i t was confounded with the outcome var iable . Theregress ion equation did not achieve s ignif icance. Although thefour sets of independe nt var iables accounted for 16% of the var i-ance in somatic heal th, the adjus ted R 2 was less than 1%.Psychological symptoms . Using psychological symptoms asthe depe ndent var iable , we per form ed a ser ies of mult iple regres-s ion analyses . F irs t , the fou r sets of predict or var iables were en-tered hierarchical ly. In each case the personali ty var iables werealways entered f irs t because in our theo ret ical f ramework theyare antecedents o f appraisal and coping processes . The o rder inwhich the appraisal and coping var iables were entered was rotatedin order to evaluate their re lat ive contr ibu tions to the tota l var i-ance accou nted for by the regress ion models . The second ary ap-

praisal var iables did n ot s ignif icantly explain var iance in theoutcome var iable regardless of their posi t ion in the equation,and they were el imina ted f rom fur ther analyses .

A regress ion analys is was then pe r formed with three sets ofpredictor var iables entered in the fol lowing order : personali tyvar iables (mastery and trus t) , pr imary appraisal var iables ( s ixstakes scales), and coping (eight coping scales). Together, thesevar iables explained 43% of the var iance; the adjus ted R 2 was.36. The personali ty var iables accounted for 18% of the var iance(p < .001) , whereas the pr imary ap praisal var iables accoun tedfor an a ddit ional 17% (p < .001) , and the coping var iables ac-counted for an addit ional 9% (p = .02) . When the order ing ofthe pr imary appraisal var iables and the coping var iables wasswitched in order to determine which explained a greater pro-por t ion o f var iance in psychological sympto ms, the coping var i-ables accounted for 20% (p < .001) of the var iance beyond thataccounted for by the personali ty variables , and the pr im ary ap-praisal var iables accoun ted for an addit ion al 5% (p = .099) ofthe var iance. The over lap between pr ima ry appraisal and copingthat these analyses revealed is consistent with previous f indingsthat indicated that they were s trongly related within s tressfulencounters as w ell (Folkm an et a l . , in press) .

Because there is no theoret ical bas is for order ing pr imaryappraisal and coping var iables when they are aggregated across

For purposes o f statistical analysis, we treated our subjects as inde-pendent o f their spouses. In so doing, we may have overestimated theavailable degrees of freedom. To examine this possibility, we adjusted thedegrees of freedom to reflect the N of couples rather than the N of in-dividuals. Several bivariate correlations that were significant (p < .05)became nonsignificant with the restricted degrees of freedom. H owever,in the key regression analysis, in no case did an F statistic or a partcorrelation that was previouslysignificant p < .05) become nonsignificant.

-

8/3/2019 Appraisal, Coping, Health Status Etc.. e de Lazarus

6/10

576 FOLKMAN, LAZARUS, GRUEN, AND DELONGIS

encounters , and because the regress ion analyses provided noempirica l bas is for ordering, the primary appra isa l and copingvariables were com bined into o ne se t for a f ina l regress ion anal-ys is. In this analys is , the person al i ty variables were entered asthe f i rs t se t , and the pri ma ry app ra isa l and coping variables asthe second se t . This regression analys is is summ arized in Table 4 .

According to the par t corre la t ions , control l ing for a ll the oth ervariables in the equat ion showed th at mas tery, in terpersonal t rus t,and concern for a loved one 's wel l -being were negat ive ly asso-ciated with psychological sym ptom s, whereas confrontive coping,concern about f inancia l securi ty , and concern about one 's ownphys ica l wel l -being were pos i t ive ly associa ted with symp toms.

D i s c u s s i o nThe centra l is sue of this research is whether the w ays in wh ichpeople cogni t ive ly appra ise and cope with the in ternal an d ex-

ternal dem ands o f s tress ful events are re la ted to so matic heal ths ta tus and psychologica l symptom s. Because the assumption ofs tabi l i ty of appra isa l an d co ping processes over occas ions under-l ies this is sue , we give our a t tent ion f i rs t to o ur f indings regardin gs tabil i ty , and then turn to the re la t ions among the person al i tyvariables , appra isa l , coping, and a dapta t iona l s ta tus .The Stability o f Appraisal and Coping Processes

On the whole the coping variables tended to have higher au-tocor re la t ions than d id the p r imary and s econda ry appra i s a l

-

8/3/2019 Appraisal, Coping, Health Status Etc.. e de Lazarus

7/10

APPRAISAL, COPING, HEALTH, AND SYMPTOMS 57 7per tains more to the person ' s internal s ta te than to the environ-ment, an d i t is interes t ing to n ote that i t a lso had the highestautocorrelat ion of the p r imary and secondary appraisal var iables .

Relations Among the Predictor VariablesThe intercorrelat ions within the sets of the aggregated var iables

measur ing pr imary appraisal , secondary appraisal , and copingparal le l those that are based on unaggregated scores (Folkmanet a l . , in press), a l though the intercorrelat ions that are based onthe aggregated var iables tend to be s l ightly larger , especial lyamong the coping var iables . One interpretat ion for the largerintercorrelat ions is that aggregating var iables over occas ions ledto reduced er ror var iance (cf. Epstein, 1983) . Ano ther interp re-tat ion also f i ts our data . Intraindiv idual analys is of these samevar iables (Folkma n et a l . , in press) indicated that our sub jectsused an average of 6.5 forms o f coping in each stressful encounter.The am ount o f each f or m of coping tha t was used va r ied ac -cording to what was at s take and the a ppraised chang eabil i ty ofthe encounter . In our analys is , even though subjects tended tocope differently f rom enco unter to en counter , by the t im e theydescr ibed how they coped with the d eman ds o f five separate en-counte r s, they had pr obably dr awn up on mos t o f the ava i lab leforms o f coping, thus reducing v ar iabil i ty and increas ing theinter relat ions .

var iables. This pat tern could be the result of the greater inherentrel iabil i ty of the mult i- i tem coping scales (alphas ranged f rom.61 to .79) in com par ison with the other var iables , which, withthe exception of self -es teem s takes and concern for a loved one ' swell-being, were s ingle i tems whose rel iabil i ty is uncer tain.

Although the coping scales showed more s tabil i ty than theother var iables , there were interes t ing dif ferences in the magni-tudes of their separate autocorrelat ions . The three coping scaleswith the lowest mean autoco rrelation , confrontive coping (averager = .21), seeking social sup por t (average r = . 17), and pla nfulprob lem solving (average r = .23) , include vir tual ly al l the prob -lem-focused coping s trategies that were assessed. The low au-tocorrelat ions suggest that the use o f these problem-focused formsof coping are s trongly inf luenced by the s i tuat ional context . Pos-i t ive reappraisal had the highest mean autoco rrelat ion ( .47) . Acomparable scale was also the most s table in a previous s tudy(Aldwin et a l . , 1980) , with appro xima tely the same level of au-tocorrelat ion over 9 months . The fact that posi t ive reappraisalwas more s table than other kinds o f coping in two s tudies withdif ferent populat ions suggests that i t may be m ore heavily inf lu-enced by personali ty factors than other coping s trategies .

Similar ly, the general ly low autocorrelat ions am ong the pr i-mar y an d secondary appra isal var iables may ref lect their sensi-t ivi ty to c ondit ions in the environment. Indices that assess con-cern with a loved on e ' s well-being, a goal a t work, f inancial se-cur i ty, respect for another , and whether the o utcome of anencounte r can be a l te r ed a re or ien ted to w ha t i s happening inthe envi r onment . The m ain except ion bo th conceptua lly andempir ic al ly is the s takes index that assesses the extent to whicha person' s self -es teem is involved in an encounter . This s take

Somatic Health StatusThe s ignif icant re lat ions between appraisal , coping, and so-

matic heal th s ta tus were al l negative, which indicated tha t themore subjects had at s take and the m ore they coped, the poo rertheir heal th was . In contras t , the more mastery they fel t , thebetter their heal th was . However , none of the cor relat ion s ex-ceeded .26. Given the m odest bivar iate cor relat ions and the in-tercor relat ions among the var iables , i t is not surpr is ing that incombination the predictor var iables did not account for s ignif -icant por t ions o f var iance in som atic heal th s ta tus .

Lazarus and Folkman (1984b) suggest three pathways throughwhich coping might adversely af fect somatic heal th s ta tus . F irs t ,coping can inf luence the f requency, intensi ty, durat io n, an d pat-terning of neurochemical responses ; second, coping can af fecthealth negatively when i t involves excess ive use o f injur ious sub-s tances such as a lcohol , drugs , and tobacco , or when i t involvesthe person in act ivi t ies of high r isk to l i fe and l imb; a nd third,cer tain fo rms of coping (e .g., par t icu lar ly denial- l ike processes)can impair heal th by impeding adaptive health/ i l lness- relatedbehavior. Other wr i ters, such as Depue, Monro e, and Shach man(1979) , emphasize s table pat terns of appraisal as a cr i t ical path-way through which somatic outcomes are af fected.

All these pathways depend on s table pat terns o f appraisal andcoping, which were not eviden t in this s tudy. Fur thermo re, thepathway through which denial-l ike coping impedes health/ il lness-related behavior of ten depend s on the presence o f heal th- relatedstressors, but in this study only 48 (6%) of the 750 stressful en-counters that subjects repor ted were direct ly related to heal th.Thus whether appraisal and coping processes do in fact af fecthea l th ou tcomes th r ough the pa thways jus t desc r ibed r emainsuncer tain.

-

8/3/2019 Appraisal, Coping, Health Status Etc.. e de Lazarus

8/10

57 8 FOLKM AN, LAZARUS, GRUEN, AND DELONGISP s y c h o l o g i c a l S y m p t o m s

Despite the lack of s tabil i ty in som e of the process var iables ,the regress ion analys is indicates that personali ty var iables andaggregated appraisal and coping processes have a s ignif icant re-la t ion to psychological symptoms. Mastery and interpersonal t rus twere s ignif icantly cor related with psychological sympto ms, evenaf ter we control led for appraisal and coping. Mastery and inter -personal t rus t were conceptualized in this s tudy as personali tyfactors that inf luenced app raisal and coping processes , but thebivar iate cor relat ions indicated that they were relat ively inde-pende nt o f these processes . Thus al though these personali ty fac-tors are impo r tant cor relates of psychological sympto ms, we arelef t unclear as to the m echan isms u nder lying this re lat ion.

The pat tern of cor relat ions between the s takes var iables andpsychological symp toms ind icated that in general the more sub-jects had at s take over diverse encounters , the more they werel ikely to exper ience psychological symptom s. The exception ishaving conce rn for a loved one 's well-being, which was negativelycorrelated with sympto ms. One interpretat ion of this re lat ion isthat a t ten ding to a loved one ' s well-being might have a salutoryef fect, or that people who are mo re other -centered than self-cen-tered are less a l ienated and bet ter of f psychological ly. Ano therinterpretat ion, which reverses the cause-ef fect pat tern, is thatthe more psychological symp toms one exper iences , the moredif ficult i t is to a t tend to the well-being of a loved one.

The s ignif icant par t c or relat ions between coping and psycho-logical symptoms were conf ined pr imar i ly to problem-focusedforms of coping. P lanful prob lem solving was negatively cor re-la ted with sym ptoms, whereas confrontive coping was posi t ivelycorrelated. These relation s parallel those foun d in a pr ior analysisof specific stressful encount ers (Fol kma n et al. , in press), in wh ichplanful problem solving was associated with sat is factory en-counter outcomes, and confrontive coping with unsat is factoryoutcomes. O n the bas is of the f indings f rom the two s tudies, i tis tempting to suggest that planful pro blem solving is the mo readaptive form of coping. However, i t is imp or tan t n ot to valuea par t icu lar form o f coping without reference to the context inwhich i t is used (see also Vaillant, 1977). There may b e occasions,for example, when confrontive coping is the m ore ad aptive form,as is suggested by studies of coping among cancer and tuberculosispatients (e.g. , Calden, Dupertuis, Hokanson, & Lewis, 1960;Cuadra, 1953; Rogenstine et al. , 1979).

The fai lure of individual forms of emotion-focused forms o fcoping to con tr ibute s ignif icantly to adapta t ional s ta tus at themult ivar iate level may have been due to mult icoll inear i ty. Escape-avoidance, for example, which h ad a .51 ze ro-order cor relat ionwith sym ptom s, was also cor related with confrontive coping at.52. Th eoret ical ly we expect dif ferent forms of coping to be in-tercor related, as noted ear lier . The intercorrelat ions , however,pose pr oblems a t the ana ly t ic level , and may mask impor tan trelat ions .

ConclusionA m ajor issue raised by this research concerns the s tabil i ty of

the var iables that w ere used in the analys is . These var iables rep-resent processes that occur in specif ic person-environmenttransact ions . Our research suggests that on the wh ole these pro-

cesses tend to be mo re var iable than s table (see also Folkm an &Lazarus, 1980). Nevertheless, they accounted for a significantamo unt of var iance in psychological sympto ms. To the extentthat this f inding depend ed on what l i t t le s tabil i ty there was inthe observed processes, researchers should turn their a t tent ionto how they mig ht m ore ef fect ively identify the s table aspects ofstressful person--environm ent transactions, and the ap praisal andcoping processes that occur within their context .

The analys is repor ted here was based on a samp le of jus t f ives tressful encounters. A larger sample of encounters might haverevealed greater s tabil i ty, par t icular ly in emotion -focused formsof coping, and increased our abil i ty to explain adaptat iona l s ta tus .

Another way in which our approach may have af fected theresults has to do w ith the level of abstractio n at which we assessedappraisal and coping processes . By exami ning specif ic thoughtsand acts , we assessed these processes at a re lat ively microa nalyt iclevel . Although this proc edure is necessary in order to exa minethe functional re lat ions among these processes , informal obser -vat ions of behavior suggest that people have cha racter is t ic waysof apprais ing and coping that t ranscend specif ic thoughts andacts, which a more abstract , macroa nalyt ic approac h might re-veal. Unfor tunately, t radit io nal me asures o f coping s tyle , suchas repress ion-sensi t izat ion (Byrne, 1961) , tend to b e unid imen -s ional and do not adequately capture the r ichness and complexitythat character ize actual appraisal and coping processes . A majo rchallenge in s tress and coping research is to develop a m etho dfor descr ibing s table s tyles of apprais ing and coping that doesnot sacr if ice the cognit ive and b ehavioral r ichness o f these pro-cesses (Fol kma n & Laza rus, 1981). At this highe r level of ab-s tract ion the l inks between appraisal , coping, and o utcomes suchas psychological symp toms sho uld become dearer .

ReferencesAldwin , C., Folkman, S., Schaefer, C., Coyne, J. C ., & Lazarus, R . S.(1980). Wa ys of coping: A process measure. Paper presented at theannual meeting of the American PsychologicalAssociation, Montreal.Andrews, G., SchoneU, M., & Tennant, C. (1977). The relationship be -tween physical, psychological, and social morbidity in a suburbancommunity. American Journal o f Epidemiology, 105, 27-35.BeUoc, N. B., & B reslow,L. (1972). Relationship o f physical health statusand health practice. PreventiveMedicine, I, 409-421.Belloc, N. B., Breslow,L., & Hochstim, J. (1971). Measurement of physicalhealth in a general population survey. American Journal o f Epide-

miology, 93, 328-336.Billings,A. G., & M oos, R. H. (1984). Coping, stress, and social resourcesamong adults with unipolar depression. Journal o f Personality andSocial Psychology, 46, 877-89 I.Bradburn, N. (1969). The structure o f well-being. Chicago: Aldine.Bradburn, N. M ., & Caplovitz, D. 09 65). Reports on happiness: A pilotstudy of behavior related to m ental health. Chicago: Aldine.Buhler, C. (1968). The general structure of the h uma n life cycle. In C.Buhler & E Massarik (Eds.), The course ofhum an life: A study o fgoalsin th e humanistic perspective(pp. 12-26). New York: Springer.Byme, D. (1961). The repression-sensitization scale: Rationale, reliab ility,and validity.Journal of Personality, 29, 334-349.Calden, G., Dupertuis, C. W., Hokanson, J. E., & Lewis, W. C. (1960).Psychosomatic factors in th e rate o f recovery from tuberculosis. Psy-chosomatic Medicine, 22, 345-355.Cohen, E, & Lazarus, R. S. (1973). Active coping processes, coping dis-positions, and recov ery from surgery.PsychosomaticMedicine, 35, 375-389.

-

8/3/2019 Appraisal, Coping, Health Status Etc.. e de Lazarus

9/10

APPRAISAL, COPING, HEALTH, AND SYMPTOMS 579Cuadra, C. A. (1953). A p sychometric investigation of control actors inpsychological adjus tmen t. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Universityof California, Berkeley.DeLongis, A., Coyne, J. C., Dakof, G., F olkm an, S., & Lazarus, R. S.(1982). Relatio nship of daily hassles, uplifts, an d m ajor life events tohealth status. Health Psychology,1, 119-136.Depue, R. A., Monroe, S. M., & Sh achman, S. L. (1979). The psycho-biology of hum an disease: Implications for concep tualizing the de-pressive disorders. In R. A. Depue (Ed.), The psychobiology of thedepressive disorders." Implications fo r the effects of stress (pp. 3-20).New York: Academic Press.Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., Covi, L., Rickels, K., & Uhlenhuth,E. H. (1970). Dimensionsof outp atient neu rotic pathology: Comparisonof a clinical versus a n empirical assessment. Journal o f ConsultingPsychology, 34, 164-171.Derogatis, L. R., Lipm an, R. S., Rickels, K., Uhlen hut h, E. H., & Covi,L. (1974). The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-reportsymp tom inventory. Behaviora l Science, 19, 1-15.Epstein, S. (1983). Aggregation and beyond: Some basic issues on theprediction o f behavior. Journal of Personality, 51, 360-392.Fieishm an, J. A. (1984). Personality characteristics and coping patterns.

Journal o f Health and Social Behavior, 25, 229-244.Folkman, S., Aldwin, C., & lazar us, R. S. (1981). The relationship betweenlocus o f control, cognitive appraisal and coping. Paper presented a t theannu al meeting of he A merican PsychologicalAssociation, Los Angeles.Folkm an, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a midd le-aged comm unity sample. Journal o f Health and S ocial Behavior, 21,219-239.Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1981). Reply to Sh inn and Kra ntz. Journalof Health and Social Behavior, 22, 457-459.Folkm an, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it mu st be a process:A study of emo tion and coping du ring three stages of a college ex-amination.Journal ofPersonality and Social P sychology, 48, 150-170.Folkman, S., Lazarus, R . S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A., & Grue n,R. (in press). The dy nam ics of a stressful encounter. Cognitive appraisal,coping, an d e ncou nter outcomes. Journal o f Personality and SocialPsychology.Folk man , S., Schaefer, C., & Lazarus, R. S. (1979). Cognitive processesas mediators of stress and coping. In V. Hamilton & D. M. W arburton(Eds.), Hum an stress and cognition: An information-processing ap-proach. (pp. 265-298). London: Wiley.Jones, W. H., Hobbs, S. A., & Hockenhury, D. (1982). Loneliness andsocial skills deficits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,, 42,682-689.Kan ner, A. D., Coy ne, J. C., Schaefer, C., & Lazarus, R . S. (1981). Com-parisons of two m odes o f stress measurem ent: Daily hassles and upliftsversus ma jor life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4, 1-39.Kobasa, S. C. (1979). Stressful life events, personality, and health: A ninquir y into hardiness. Journal of P ersonality and Social Psychology,,37, 1-11.

Krohne, H. W., & Laux, L. (1982). Achievem ent, stress, and anxiety.Washington, DC: Hemisphere.Lazarus, R. S., & DeLongis, A. (1983). Psychological stress and copingin aging. American Psychologist, 38, 245-254.Lazarus, R. S., & Folk man , S. (1984a). Copin g and ad aptation . In W. D.

Gentry (Ed.), The handbook o f behavioral medicine (pp. 282-325).New York: Guilford.Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984b). Stress, appraisal, and coping.New York: Springer.Menaghan, E. (1982). M easurin g coping effectiveness: A pan el analysisof marital pro blems and efforts. Journal ofHealth and So cial Behavior,

23, 220-234.Meltzer, J., & Hochstim, J. (1970). R eliability and validity o f survey dataon physical health. Public Health Reports, 85, 1075-1086.Nelson, D. W., & Cohen, L. H. (1983). Loc us of control perceptions andthe relationship between life stress and psychologicaldisorder. AmericanJournal o f Comm unity Psychology, 11, 705-722.Pearlin, L. I., Lieberman, M. A ., Menaghan, E. G., & M ullan, J. T. (1981).The stress process. Journal o f Health and Social Behavior, 22, 337-356.Pcarlin, L. I., & Schooler, C. (1978). Th e stru cture of coping. Journal ofHealth and Social Behavior, 19, 2-21.Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scalefor research in the general population. Applied Psychological Mea-surement, 1, 385--401.Rickels, K., Lip man , R. S., Garc ia, C. R., & Fisher, E. (1972). Evalua tingclinical improv emen t in anxious outpatients. American Journal ofPsychiatry, 128, 119-123.Rogenstine, C. N., va n-K am me n, D. P., Fox, B. H., Docherty, J. P., Ro-senblatt, J. E., Boyd, S. C., & Bun ney, W. E. (1979). Psychologicalfactors in the prognosis of m alignan t melanoma: A prospective study.Psychosomatic Medicine, 41, 147-164.Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the ado lescent self-image. Princeton,N J: Prin ceto n University Press.Rotter, J. B. (1980). Interpersonal tru st, trustworthiness, and gullibility.American Psychologist, 35, 1-7.Sandier, I. N., & Lakey, B. (1982). Locus of con trol as a stress indicator:The role o f control perceptions a nd social support. American Journalof Com munity Psychology, 10, 65-80.Schultz, N. R., Jr., & Moore, D. (1984). Loneliness: Correlates, attri-butions, and coping am ong older adults. Personality and Social Psy-chology Bulletin, 10, 67-77.Shana n, J., De-Nour, A . K., & Ga rty, I. (1976). Effects of prolonged stresson coping style in te rmin al and re nal failure patients. Journal ofHumanStress, 2(4), 19-27.Solano, C. H., Batten, P. G., & Parish, E. A. (1982). Loneliness andpatterns of self-disclosure.Journal o f Personality and Social Psychology,,43, 524-531.Stone, A. A., & Neale, J. M. (1984). New m easur e of daily coping: De-velopment an d prelimin ary results. Journal o f Personality and SocialPsychology, 46, 892-906.Uhlenhuth, E. H., Lipman, R. S., Baiter, M. B., & Stern, M. (1974).Symptom intensity and life stress in the city.Archives of General Psy-chiatry, 31, 759-764.Vaillant, G. E. (1977). Adaptation to life. Boston: Little, Brown.Wheaton, B. (1983). Stress, personal coping resources, and psychiatricsymptoms: An investigation of interactive models. Journal o f Healthand S ocial Behavior, 24, 208-229.

Received Apr i l 23, 1985 9

-

8/3/2019 Appraisal, Coping, Health Status Etc.. e de Lazarus

10/10

Reproducedwithpermissionof thecopyrightowner. Further reproductionprohibitedwithoutpermission.