A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

-

Upload

luka-bruketa -

Category

Documents

-

view

381 -

download

56

Transcript of A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 1/72

A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification

Author(s): A. W. LawrenceSource: The Annual of the British School at Athens, Vol. 78 (1983), pp. 171-227Published by: British School at Athens

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30102803 .

Accessed: 23/01/2014 12:21

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

British School at Athens is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Annual of

the British School at Athens.

http://www.jstor.org

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 2/72

A SKELETAL

HISTORY

OF BYZANTINE

FORTIFICATION

(PLATES 8-21)

T

HISseriesof

analytical

descriptions

was

written

in

the

hope

it

might

reveal

both how

defensive

principles changed

and to what

extent

tradition

prevailed,

all

through

the

Byzantine

centuries.

Ideally

the

investigation

should

have been

restricted

to

fortifications of which the exact or

approximate

date was known from

literature

or

by

inscription,

but their

number is far too

small to be

genuinely

representative

even of

major

works,

which

alone tended to be so

recorded.

I

have therefore

included,

in

addition,

fortifications that

I

thought

were built

in

response

to

specific

historical circumstances

and

could

thereby

be dated within the

limits of

roughly

one

generation. Obviously such ascriptionsare bound to be more or less questionable, but I have

assessed

their

plausibility

also on

stylistic

considerations; however,

no

monument

has been

included

solely

on

grounds

of

style.

Since

this

is no

balanced

account of

Byzantine

military

architecture but

a

necessary

preliminary,

the

space

allotted

to

the individual

buildings

bears little

relation to

their

merits,

or

rather to

my

knowledge

thereof.

I

write

briefly

of remains

already satisfactorily

published,

but otherwise at whatever

length

may

be

requisite

to the

argument, particularly

about ruins

I

have

myself

examined.

In the course

of

many years

I

saw and

made notes

on

Byzantine

fortifications

(some

repeatedly)

in

eight

countries,

beginning

as

long ago

as

1950

with

the aid

of a

Leverhulme

Fellowship.

The infirmities of

age

have

unfortunately

prevented

recent

checking

on the

spot.

CONTENTS

I.

Heritage

from the undivided

Roman

Empire

of

late third and fourth centuries

2.

Transition to the fifth

century:

Corycus

and

Sparta

3.

Constantinople

and

regional capitals,

412-c. 450

4.

Towns with massive

proteichisma,

mid

or late

fifth

century

5.

The

reign

of

Anastasius

I,

491-518

6. The

reign ofJustinian, 527-565

7.

Truncation of the

Empire,

late sixth

and

early

seventh

centuries

8. Small-scale works

against

the

Arabs,

mid

seventh-early eighth

centuries

9.

Ancyra/Ankara,

seventh-ninth

centuries

10.

Additions at

Constantinople prior

to c.

850

I1.

Early

and mid tenth

century:

Attaleia, Samothrace,

Philippi,

Kyrenia

12.

Qal'at Sim'an,

979,

and

smaller beacon-forts

13.

End

of the tenth

century:

Paicuiul

ui

Soare,

Sahyun,

Ohrid,

Didyma

14.

End of the eleventh

century:

Zvecan

and

St. Hilarion

15.

Mid and

late twelfth

century:

Constantinople, Pergamon,

Miletus

16.

The successor

states,

1204-c. 1250

17.

Last datable

works,

1261-1453

Appendix: Some featuresin vaguely dated monuments

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Thu, 23 Jan 2014 12:21:25 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 3/72

172

A. W. LAWRENCE

I.

HERITAGE FROM

THE

UNDIVIDED

ROMAN EMPIRE

OF

LATE THIRD

AND

FOURTH

CENTURIES

The various

types

of

Byzantine

fortifications

all

began

by

following precedents

set when

inability

to hold

the

frontiers had let

similar

dangers

prevail

within

the Roman

Empire.

The

first barbarian invasions, during the third quarter of the third century, evoked Aurelian's wall

of Rome and

a

proliferation

of

efficient,

though

less

imposing,

walls around towns

in

western

Europe,

but

generally

poor

and often small defences

in

provinces

that afterwards became

heartlands of the Eastern

Empire.

The town wall of

Nicaea/IznikI

is indeed

the

only

dated

one

that

can rank with

many

in

France

and

Spain,

and the

fact that it

was built for

an

Emperor

(Claudius

Gothicus

in

268/9)

probably

accounts

for

its

superiority

to

other

works

which

may

have

depended

on local resources of

money

and skill.

It

stood,

with occasional

minor

repairs,

for

nearly

a

thousand

years

before the

Lascarids chose Nicaea for

their

capital

and built an

outer

wall. The

curtains,

none

of which was less

than

3-6o

m

thick,

had

previously

been about

9

m

high;

externally they

were

interrupted

at

intervals

of

6o-7o

m

by

semicircular,

half-oval,

or

apsidal

towers

(scarcely distinguishable

at a

glance)

that

projected

to

roughly

the

same distance

as

their

maximum

width,

8-9

m,

and

had

originally

been little taller

than

the

curtains.

A

pair

of such towers

flanked each of the

main

gateways,

which

actually

were

ornamental

entrances of Roman

construction but

altered to receive

a

portcullis.

We

may

assume that

portable

catapults

were

expected

to be massed

on towers

along

any

threatened

sector of

the

5

km

perimeter.

Throughout

the

wall,

both the stone

facing

and the

core

of

cemented

pebbles

were

completely

intersected

by

several

levelling-bands

composed

of

four

brick

courses,

resulting

in

practically

the same effect

as the bands of

five

courses

used

at

Constantinople

more

than

I50

years

later.

In

contrast

to this

imperial enterprise

at

Nicaea,

a

reconstruction

of the Hellenistic

wall

across the

Miletus

isthmus2

made

it defensible with manual

weapons.

The

zigzag planning

had been accentuated by a tower projecting forward from the apex of every pair of curtains,

but these alone were

rebuilt;

the

ruined towers were

totally

demolished.

In

Greece the

destructive

Herulian

raid

of

267 gave

rise

to

extremely

diverse

precautions

against

a

recurrence.

Athens

naturally

fared

best.

A

massive new

wall,3

consisting

of reused

material and

incorporating

fragmentary

old

buildings,

enclosed

an area

of uneven

ground extending

far

northward

from the

acropolis

by

means

of curtains

of varied

length

and

rectangular

towers

at

irregular

intervals,

but not

all was

contemporaneous,

and most has been demolished

for

the

sake

of

revealing

classical remains.

At

Sparta

too

the town

had shrunk.

A

less

formidable,

though quite respectable,

wall

(FIG.

I)4

was

built

enclosing

a

stoa

on the southern

slope

of

the

acropolis,

with

a

pair

of small

square

towers

flanking

a

gateway,

and others

like them

amid the

straight

curtains;

pieces

of column-shaft

were

laid

horizontally

for

bonding-perhaps

the earliest instance of an afterwards common

practice.

Presumably

the Herulians also sacked

Aegina,

where

an

extensive

town

wall5

consists

of reused

material;

it seems to

have been

almost

devoid

of

flanking,

the one

salient

preserved

being

only

2'4

m

wide and

projecting

little

over

Unless the

length

of a source needs

to

be

specified,

I

cite

only

the first of

its

relevant

pages.

In

addition

to

editorially

authorized

abbreviations,

the title

stated in

n.

27

is shortened

in

subsequent

notes to

'Landmauer',

nd 'Courtauld'

refers

to

my

own

negatives,

now the

property

of

the Courtauld

Institute

of London

University;

they

include all the

photographs

illustrated

except

that

of

Pergamon,

for

which

I thank

the

donor.

I also thank

the owners of

copyrights

for

permission

to

reproduce figures.

1

W.

Karnapp

and A.

M.

Schneider,

Die Stadtmaueron

znik

(1938).

2

Milet

ii

3:

A.

von

Gerkan,

Die

Stadtmauern

(I935)

pl.

14.

3

Thompson, JRS 49

(1959)

6I

fig.

I;

Frantz,

Hesperia

8

(1979)

202

fig.

3.

The wall

used to be called Valerian's

because

of a

misleading

statement

by

Zosimus;

most has now been

demolished.

4

Traquair,

BSA

12

(1905-6) 417

pl.

viii.

5

Alt.

Agina

i

2:

W.

W.

Wurster,

Die

spdtromische

kropo-

lismauer

(1975) 9 Beilage

1-2

pls.

1-2.

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Thu, 23 Jan 2014 12:21:25 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 4/72

A SKELETAL HISTORY OF BYZANTINE FORTIFICATION

173

RO

0.,

OLIV

OLIVE

TREES

74.4

a

T7

-1

ml

N

qP

-In

7 5 ' e ,

r~cc,

4.-I

-1g

%

.

, ,

.

.. .

100 .

. . .

SCALEor

METRES

114000

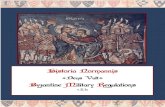

FIG.

1.

Sparta.

Plan of defences

(BSA)

a metre.

At

Olympia part

of the

sanctuary

was

converted

into a fort6 of

trapezium shape,

with the

temple

of Zeus

transformed to

a

strong

point

on one

corner,

and the back of the

south

stoa

forming

the

other end of the

enclosure;

there were three

rectangular

towers.

It has

been demolished to rescue the ancient material of which it consisted.

After the almost total excavation

of

a

very

elaborate town

wall

in

north-east

Bulgaria,

T. Ivanov's

fully

illustrated

monograph,

Abritus

i

(1980),

described

it

exhaustively

and dated

it

to the end of the third

century

or

beginning

of the fourth

by

comparing

plans

of

fortifications

all over

Europe

and

some

in

other

continents;

an

English summary

is

appended

to

his

Bulgarian

text,

and the list of

captions

is translated on

p.

248.

The whole enceinte of Abritus

is

extremely

6

ADelt

16

(I960)

Chron.

129 plan

3

pl. o105a;

eue

deutsche

usgrabungen

1959)

276.

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Thu, 23 Jan 2014 12:21:25 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 5/72

174

A.

W.

LAWRENCE

diversified

(plan

on

his

p.

30), though

its basic scheme

could

have been

treated as a

pattern

for

exact

repetition

of

features. The curtains

range

in

length

from

19

to

45-6o

m.

They

carried

a

walk about

io

m

above

ground,

entered

from both sides of the

towers,

which were

of three

storeys

connected

internally

by

wooden

stairs;

the

height

probably

amounted to

15

or

16 m

up to the merlons, above which rose tiled roofs on wooden structures (restorations on pp.

227-9).

The

towers were

individually

designed

but

basically

of

three

types: apsidal,

rectangular

(oblong

or

square),

and,

if

placed

at

a

corner,

fan-shaped.

There

were

four

main

entrances;

three of

them

opened

between

towers,

while

the

fourth stands within a shallow

rebate,

made

for

the

purpose;

all are alike

in

containing

two

gateways,

4I15-4-50

m

wide,

the outer

grooved

for

a

portcullis,

the inner

with

fittings

for

a

two-leaved

gate.

The existence

of

at least

nine

posterns

has been

verified;

some

led

through

curtains,

others from towers.

The castrum

t

Luxor,7

containing

dedications

of the

year

300

to

Diocletian

and his

colleagues,

had a disused Pharaonic

temple

for its

centre,

behind

a

new

wall

from which

apsidal

towers

projected

singly

if

at

regular

intervals but

paired

to flank

gateways;

there was

a

larger square

tower

on the one

remaining

corner.

A

door

in

the

flank of each

tower

opened

to

the

surrounding

ditch;

in

every

other

respect

the

design

conforms with

precedents

known at forts near frontiers

or

in

unruly country,

although

this

legionary

castrum

was

unlikely

to be

attacked,

being

presumably

the

quarters

for

the

garrison

of

Upper

Egypt.

Differentiation of corner

towers

by

size,

and

usually by

shape

also,

had

long

been

customary

in

forts; however,

not all the

shapes

found

in

Europe

were

used

by

the

less

venturesome

military

engineers

in

Asia or

Africa.8

Of

the

many

forts

built

under

Diocletian,

some

on the

fringes

of

the

Syrian

and

African

deserts

must

have been

familiar to

the

Byzantine

army

down

to

the

Arab

conquest.

A

typical

example,

Qasr

Bisheir,9

was

approximately

square

(the

sides

varying

from

54'45

to

57-05 m),

with

curtains

6-50

m

high,

lined

with two

storeys

of

rooms

surrounding

a court.

The

gateway,

2-65

m

wide and over

3

m

high,

is covered

by

a lintel below

a

relieving

arch;

it

occupies

half

the space between a pair of rectangular towers 6 m wide. Three-storeyed corner towers, some

I I

or

12

m

square, project slightly

more

than

3

m

from the

curtains.

Vaulting

is the normal

method

of

ceiling--inevitably

on this

timberless

edge

of

Jordan.

Diocletian's

palace

at

Split,

with its

internal

divisions,

is

basically

like

a

magnified

and

sumptuous

version of

a

castrum.Each entrance to

the

oblong

enclosure

is flanked

by

a

pair

of

octagonal

towers,

and

a

rectangular

tower

intervenes

on either

side

between them

and

the

much

larger

corner

towers,

which

are

square

and

almost

separate

from the

curtains. Each of

the

remaining gateways

is

groovedI'

to receive

a

portcullis,

which could have

been

nearly 13

cm thick.

Perhaps

in

imitation of

Split,

the

'Porta Caesarea'

at

the

neighbouring

city

of Salona

was outflanked

by octagonal

towers."

The

triple

entrance,

as

rebuilt

about

350,

contained

a

narrow corridor

to

either

side of

a

central

passage,

3-95

m

wide,

which

must have been

gated

at a wooden door-frame fixed into recesses at least 20 cm deep and 38 cm wide-dimensions

inconceivable

for a

portcullis.

Two coins issued

between

355

and

36I

define

a terminus

post

quem

for the

construction

and

brief

occupation

of a frontier

fort

at

Pagnik

Oreni

on the

Euphrates.12

The enclosure

(FIG. 2)

7

Monneret de

Villard,

Archeologia 95

(i953)

96

pl.

34-

8 von

Petrokovits,

JRS

6i (1971)

I78-218

analyses

late

Roman fortifications

in

Europe,

relying

largely

on tower

shapes.

The

fan

shape

(184

n.

15 fig.

29.7)

is not found

in

Asia or

Africa

and seems almost

confined

to

the

4th

cent.;

Procopius

records

as anomalous its

use in

a

fort

built for

Justinian

in

Thrace

(Aed.

v

8),

and

probably

this was due

to

imitation

of a Roman

example,

such

as

could

be seen at

Abritus.

9

R.

E.

Briinnow

and

A.

Domaszewski,

Die

ProvinciaArabia

ii

(1905)

49

figs.

619-36.

10

The

grooves

were

cut before the blocks

were

laid,

but so

carelessly

that the width varies

between

13.5

and

15

cm.

11

W.

Gerber,

Forschungen

n

Salona

fig.

244.

12

Harper,

AS

21

(1971)

10o,

22

(1972)

27.

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Thu, 23 Jan 2014 12:21:25 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 6/72

A SKELETAL

HISTORY OF BYZANTINE

FORTIFICATION

175

1

2

3

4

5

6

F

E

A

Xr

I

JI

Im

I I M

\3

VIY

/

1\

N

PAGNiK

RENi

971

0 10

25

M

V

2

I

x

FIG.

2.

Pagnik

Oreni.

Plan

of

excavation

(AS)

is

roughly

semicircular,

140

m

long

with

a

maximum width of

80

m,

following

contours

that

would aid defence.

The

curtains,

some

2

m

thick,

may

have been

quite

tall.

Few of them

are

appreciably

longer

than

25

m.

This shortness

(and

a

monstrous

elongation

of the

whole

perimeter)

was due to

cramming

on to the

frontage

as

many

towers

as

possible,

so

that it

allowed

of-in

fact,

called for-a much

larger

number of defenders

than

could be stationed

within as

a

garrison.

We

may confidently

assume

that

the

population

of

the whole

neighbourhood was expected to come, not merely for refuge, but to help keep every embrasure

manned

(in

spite

of

casualties)

throughout

an

assault,

using

manual

weapons

such as stones.

The

river,

just

below the

fort,

formed the

boundary

of the

aggressive

Sassanian

empire,

and

any army

it

put

across was sure to be

enormous,

with a

highly

trained

nucleus,

and well

equipped.

So the

designs

of the towers

were chosen to minimize

the effects of

siegecraft,

however

competent.

All

eleven of them are

curved,

but

they

differ

in

size and

shape;

one

is

very

shallow,

several are

semicircular,

others

apsidal

or bent like horseshoes.

Only

one was

walled at the

back,

though

all

were

roofed

upon

timbers

so

heavy

as

to make it

necessary

to

halve the

span

in

each of the wider

towers

by

means of

a

partition.

For

protection against

less

dangerous

enemies,

the

desert

fringe

of southern

Palestine received

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Thu, 23 Jan 2014 12:21:25 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 7/72

176

A. W. LAWRENCE

a chain of

much smaller

forts,

examples

of the

type archaeologically

called

a

tetrapyrgos,13

which the

Greeks

had

used

since

the fourth

century

B.c.

Four

towers

always

project

at

right

angles

from

the

corners

of a

square

or

oblong

enclosure

(cf.

FIG.

20).

One of the

Palestinian

set

that has

been

excavated,

at

En

Boqeq,

contained

objects

datable

about

370-400.

It

measures

some 23 X28 m externally, the wall is 1-75-2 m thick, and the gateway 1-70m wide. Most of

the

interior

was left

open

as a court

but

a

few

rooms

encroached

upon

it.

The

towers,

of

roughly

6

x

4

m,

project only

about

a

metre

in

one direction but

4

m

in

the other.

The

Isaurians remained unsubdued

in

their mountains for

some

230 years

after

they

rebelled

against

Gallienus,

whose

successors,

late

in

the

third

century,

tried to

keep

them

innocuous

by building

a

ring

of

forts,

of which no

details

are

known.

The

Isaurians

became more

formidable

after three

generations

of

independence,

as is

shown

by

their

attempt

to

capture

Seleucia/Silifke

about

355.

Fear

of

a

recurrence

must

have induced

an

imperial

official,

'the

splendid

ruler of the

Eparchy

of the

Isaurians',

to secure the nearest

piece

of coast towards

the

south-east,

some

15

km

distant,

by

building

a

fortified town

at an

inlet

suitable to

be the

harbour

for a

relieving

force.14

His

inscription,

which

is

datable between

367

and

375

by

the

reigns cited, names the place Korasionnd says it had previouslybeen uninhabited. The plan

is reminiscent

of

ancient

Greek rather

than

Roman

practice;

towers,

6

or

7

m

square,

are

interposed

between short

aligned

curtains

or

attached

solely

by

a corner

to

right-angle

bends.

Supposedly

about

the

middle of

the

fourth

century

a

force of Isaurians

came

into

Pamphylia

and

began

marauding,

but

was annihilated

in

an attack

by

the

garrison

of Side.

Any

respite

gained

by

this

success

must

have

been

of

relatively

short

duration,

for

the Isaurians

soon

grew

stronger

and

acquired

military

expertise.

Letters written

in

40

I

and

the

following

years

vividly

describe

the

terror

in which

they

kept

the

population

in

their

vicinity,

while

they

constantly

raided

far

and

wide

through

Asia

Minor,

and once

even

penetrated

to

Galilee

and

Phoenicia.

Pamphylia obviously

remained

in

danger

until

Leo

I,

who

reigned

from

457

to

474,

imposed

military governorsupon it as well as upon two inland provinces throughwhich the route from

Isauria

passed.

But defensive works

had

surely

been undertaken

already,

when

it first

became

apparent

that

large

towns

might

be

attacked,

however distant

from

the raiders'

homeland;

Side would

not have

been

excepted,

since

the

garrison

was liable

at

any

time to vacate the

city

in

order

to

stop

the

plundering

of

some other

district,

and

its

Hellenistic

wall

was no

longer

defensible.

The

dilapidations

were,

in

fact,

made

good'5--thoroughly

on

the

landward

sectors,.where

new construction sometimes

begins

at

ground

level

and is

apparent

all

the

way

up

the

facing

of

a

tower;

a

back wall

also

was added

to

the towers

that

originally

had

none,

so

reinforcing

their whole structure. Entrances were either

partially

or

completely

blocked.

Alterations

of

this sort

are

found,

here

and

there,

throughout

the landward

defences,

which

extend

for

approximately

I

km. But more than

half the

enceinte

faced

seaward,

and received

only a minimum of repair although it had originally been less strongly built and must have

deteriorated

quite

as

badly; obviously

the

guards posted

along

it could obtain

help

promptly

in

case the

enemy

should mass on

a

beach outside.

The

population

of

Side at this

time-probably

late

in

the

fourth

century--apparently

was

large

enough

to

man

any

threatened

parts

of

the

wall,

even

in the

temporary

absence of

the

garrison.

Fortifications

against

Isaurian raiders are identifiable at two other cities of

Pamphylia.

The

13

The

word is

a

grammatically

undesirable

variant

of

the

Hellenistic

tetrapyrgia,

hich

may

have had a

less

restricted

meaning.

14

According

to

Strabo,

the

river

was

navigable

up

to

Seleucia

(now

nine

miles

inland)

but

this

may

have ceased to

be the

case

by

the

4th

cent.

owing

to

alluvium,

which has

formed

an

extensive

plain

around the

mouth,

accompanied

by

shoals

on

its west side.

The

steep

east

shore

may

already

have

been

preferable

as

a

landing-place

when

the

new

town

was

built

at

it.

15

A. M.

Mansel,

Die

Ruinen

onSide

(1963) plan

in

pocket;

Francis

Beaufort,

Karamania

1818)

147.

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Thu, 23 Jan 2014 12:21:25 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 8/72

A

SKELETAL HISTORY

OF BYZANTINE FORTIFICATION

177

administrative

capital,

Perga,

relied

on its excellent Hellenistic

wall,

but the Roman

propylaea

in

front of

the

main

entrance could have sheltered attackers.

It

was

therefore

blocked,

and

an

extension built

on either

end,

joining

the

old

wall

behind.16

Two

rectangular

towers

(PLATE

8a)

are

conspicuous

in this

connecting

masonry,

which

is

composed

of reused

blocks;

they

remain standing to a slightly higher level than their junctions with the curtains, and are

devoid of

apertures except

at the back.

Another

predominantly

Hellenistic wall

(in

one

part

Hadrianic)

surrounded

Attaleia/Antalya,

the

seaport

for

Perga;

it was now

supplemented

by

a

proteichisma,

much of

which

(FIG.

14)

still existed less than a

hundred

years ago.17

The

manpower

required

to

defend the two lines must have

exceeded

that

previously

needed,

and

would not have

been

available

for a later

menace

than the Isaurians

presented.

The

style

too

associates the outwork

with

that

period,

for

the front

was

studded

with

little

triangular

salients

as

in a

proteichisma

at

Salonica,

which

presumably

was built either

in

the last

quarter

of the

fourth

century

or near the

middle of the fifth.

2.

TRANSITION TO THE

FIFTH

CENTURY: CORYCUS AND

SPARTA

The

Eastern

Empire

was

formally separated

from

the Western

in

395,

when

the

term

'Byzantine'

ceases to be of

questionable

validity.

The

short coast of

Rough

Cilicia,

which

has been almost

uninhabited

during

recent

centuries,

bears

an

astonishing profusion

of

both

Roman

and

Early

Christianmonuments.

But at

Corycus,

the most

westerly

of the

ancient

cities,

the ruins are

almost

exclusively

Christian;

the

pagan

buildings

there were

demolished

to obtain

material

for a

fortress,18

eaving nothing

standing

except

an

arch

that

became its

main

gateway. Lengths

of

column shafts were cut to

fit

a

wall-thickness and laid

as

stretchers to tie the

masonry;

they

occur at

fairly

regular

intervals

in

the

curtains

and abound in

towers,

some

of

which are

decoratively

studded

at half a

dozen

levels with

rows

composed

alternately

of

two

or

three

pieces

of shaft

(PLATES

b,

9a).

The

ashlar facing of the cemented rubble consists very largely of classical blocks, many of them

uniform

in

size and reused

unaltered.

Since a

large

proportion

of the

material

unquestionably

came from

temples,

the

destruction of which

was

not

permissible

till

391,

that

date

would be

a

firm

terminus

ost

quem

or

the

construction,

but for

the

possibility

that

the

emperor may

have

given

special

authorization.

A

vague

substitute for

a

terminus

nte

quem

s

supplied by

the

recorded

fact that a

period

of

abandonment

began

so

long

before

I

ioo

as

to have

made the

fortress then

unserviceable

until

repaired;

considering

the

general

excellence of the

structure,

this

delapidation

is

quite

likely

to

imply

neglect during

not less than

a

couple

of

centuries.

The

original

purpose

of

the

fortress,

and

consequently

its

age,

can

be

deduced

from its

situation

and

design.

Over

more

than a

two-hour walk

to the

north-east

a

practically

continuous

urban

population

occupied

a

narrow

strip

between the sea and

the

mountains,

but the

density

was

greater

in the half nearer

Corycus;

north-west towards Seleucia the absence

of ruins

in

the

neighbourhood

shows

that,

at

most,

only

peasantry

can

have lived

on

the

way

to

Korasion,

nearly

two

hours

away.

Obviously

Corycus

was too

peripheral

to have

been

a

refuge

for

any

but the

closest

non-combatants. But its

placing,

adjoining

an

artificially

sheltered

harbour,

was

ideal

for

a

military

outpost

at

a

time

when the

Byzantines

held command

of the

seas;

it

could be

maintained in a

hostile environment

because maximum

defensibility

had

16

K.

Lanckoronski,

Niemann,

and

Petersen,

Stddte

Pam-

phyliens

und

Pisidiens

(1890) 33 fig.

49.

17

Ibid.

9 fig- 4;

the Turkish

plan

is discussed below

with

reference

to the

early

Ioth

cent.

18

MAMA ii:

E.

Herzfeld and

S.

Guyer,

Meriamlikund

Korykos

1930)

fig.

177

etc.;

MAMA

iii:

J.

Keil

and

A.

Wilhelm,

Denkmdler

us

demRauhen

Kilikien

(1931)

102

fig. 133

pl.

42;

W.

Miiller-Wiener,

Castles

of

the Crusaders

1966) 79

pls.

11I-14;

Courtauld.

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Thu, 23 Jan 2014 12:21:25 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 9/72

178

A. W. LAWRENCE

been conferred on some

I1

hectares

of low

plateau,

clearly anticipating

that

invaders

might

come

by

land

in

much

superior

numbers and

prepared

for a

determined

siege.

The

design

presumes

that not

less

than

about

a

hundred men

would

always

be

available

to

repel

assault,

but there was

space

inside for several

times as

many,

so the

commander could

spare

a considerable force for expeditions along the coastline or into the foothills. The prospective

enemies

are identifiable

as

Isaurians;

no others

can have been

envisaged

till the seventh

century,

when the

Arabs won and

exploited

control

of the seas with

the result that the

harbour

(an

integral

part

of

the

design)

must

have

become worse

than

useless,

and

Corycus

was

irrelevant to later

campaigns

by

land. Since the Isaurian menace

reached its

peak

by

about

400,

we

may

assume

that

the construction

of the fortress was not

postponed

(though

it

might

have

been

feasible,

under

a

strong

guard,

even

after the Isaurian

subjugation

of

the coast

towards

the

east).19

The

fortress stands beside

a

small

valley

flattened

by

alluvium,

which

shelves

into the water

of

a

bay (PLATE9b).

The builders

took full

advantage

of a terrace

of hard

rock,

the

edge

of

which

met the

valley

inland as

an

eroded

cliff,

several metres

high;

in

continuation,

they

cut

a ditcho2 with vertical sides across the terrace itself

(PLATE9a),

which extends far eastward

between

the wave-riven

shore of

the

open

sea and

the foothills of

the mountains.

Two

lines

of

defence,

a few metres

apart,

so

complemented

each

other that

they

functioned

as a unit.

The

main

wall,

with

towers,

on the surface

of the terrace

was

infinitely stronger

than

the

simple

outer

line,

which revets

the foot

of

the

cliff

till that

merges

northward

into

rising

ground,

then returns

to the sea on

the east as the

lining

of the

ditch,

and

completes

a

roughly

square

course

by

two

free-standing

sides,

the south-eastern

along

the

sea,

the south-western

along

a

beach

at

the

mouth

of the

valley

where

a harbour has silted

up.

This was

sheltered

by

a

jetty

which

projects

from

the south corner

of the

fortress;

though

it is now truncated

and

a

mere

jumble

of

stone,

in

1811 Beaufort

saw

it

whole,

'about

ioo

yards

long',

consisting

of

'great unhewn rocks', and terminated by a mass of cemented rubble behind a stone facing,

'2o

feet

square

with

pilasters

at the

corners'.

This,

he

realized,

had almost

certainly

been

the

base

of

a

lighthouse21

to

guide

ships

into

port.

They

could

safely

lie

and unload

at

the

jetty,

even

under

siege;

there

was

a

wide

gateway

through

the

outer defences at its

outset,

while

the classical

arch that forms

the

corresponding passage

through

the inner wall is

staggered

to

nearly opposite

the

middle of the

harbour

frontage.

The

plan

took

for

granted

that

the

Empire

would

always

command

the

sea.

A

first indirect reference

to

the fortress

may

possibly

be

recognized

in

Nicephorus

Patriarcha's

casual

mention22 of

an officer as

being

'the

commander

of the

army

of the Kourikiots'

n

697;

this,

however,

might

have been

a

corps

recruited

from

the

Corycus

district and

stationed

elsewhere,

especially

since

he was then

in

the

Cibyrrhaeot

theme.

The date comes

within

a period, 650-718, when the Arab fleet dominated the seas, looting and destroying towns

around

Asia Minor

and

attacking

Constantinople,

but coincides

with a lull in its

activities.

Militia

at

Corycus

should

have been

able to

prevent

raids on

the

populous

coast

between

there

and

the Lamas

river,

there

being

no other

place

suitable for

a

large

force to

disembark,

and

the

very

fact that the

inhabitants

remained numerous

enough

to

provide

an

'army'

implies

that

they

had

been

relatively

untroubled.

19

Theoretically,

the

fortress

might

have

been

built at

any

time between

39

I

(or

earlier

f the

emperor

had

granted special

leave for

demolitions)

and the rise to

power

of

an Isaurian

self-named

Zeno,

who

succeeded

his

imperial

father-in-law

in

474

and

reigned

to

491.

Anastasius

I

then launched the first

of the

campaigns

that crushed

the Isaurians.

20

The floor of the

ditch is all

above sea-level

but too

shelving

to have held water

unless

dammed.

21

Beaufort,

op.

cit.

242.

22

Migne,

Patrologia

Graeca

100

col.

940.

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Thu, 23 Jan 2014 12:21:25 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 10/72

A

SKELETAL

HISTORY OF

BYZANTINE

FORTIFICATION

179

In

831

the

fall

of

Tarsus

gave

the Arabs control of the entire Cilician

plain,

which

ends

at

the

Lamas,

and

the

resultant

insecurity

in

the coastal

strip

to westward is

likely

to have

caused

mass

emigration,

because

aggression

could not be

prevented.

If

the hundreds of

men

necessary

to defend the

Corycus

fortress

ceased

to be

locally

available,

the

Byzantines

would have

been

obliged to relinquish it; in any case its utility had gone.

The

Byzantines

regained

Cilicia

in

965

and held

it

for over

a

century,

till the

Seljuks

took

it,

but the transit of the First Crusade

in

I

0oo

enabled the

Byzantines

to recover

it

again.

They

found,

so

Anna

Comnena

reports,23

that

'Kourikon,

a

city

which had

formerly

been

very

strong,

had come

in

later

times

to be

falling

into ruin'. The

statement must

apply

to

the

fortress,

not

to

the more ancient and

comparatively

negligible

city

wall. She

next

records24

that the

emperor

sent

his

officer 'Eustathius to

occupy

Kourikon

nd

rebuild

it

quickly'.

Probably

the

first

unseemly

repairs

to

the

outer

line

are

due to him.

Early

remains are

distinguishable

in

the ruins

by

their

design quite

as much

as

by

the

presence

of

classical

ingredients,

some of which

were

transferred to later alterations. The

original

main

wall

not

only

rose from a

higher

level

than

the

outer line but was also

much

taller,

even in the curtains. Towers were

dispersed unevenly,

close

together

where attack would

be

easiest,

furthest

apart

beside

the

harbour;

none

directly

faced the

open

sea.

They

were

diverse

in

width,

projection,

and

height.

The

tallest,

just

behind

the northern

extremity,

has

partially collapsed,

leaving

a

slice

intact

with a

few merlons

(perhaps

not

original).

Its summit

was

valued,

no

doubt,

for a look-out

towards

the

eastern

approaches;

in

addition,

catapults

might

have

been

mounted,

as

upon

Hellenistic

prototypes,

for

the

sake

of

the

increased

range

obtainable from

such

an

elevation.

This

supposition

could

explain

the

abnormally

and

unnecessarily long

inward

projection

of the

tower,

the front of

which faces east and

is

aligned

with the

adjoining

curtain

to the south but stands

forward

from that

to the

north;

the entire

northern

flank

was

roughly

twice

as

long

as the

part exposed,

so that

there would have been

space upon it for several catapults. None of the better-preserved towers is very far from square,

except

one at

the south-east corner

(PLATE b)

that is

pentagonal,

with

a

beak

pointing

towards

the shoreline

beyond

the

ditch.

Although

most of them rise

only

slightly

above

the

curtains,

there

are no windows on

the

fronts,

contrary

to Hellenistic

practice,

nor

many

slits;

the

roof

was

the

main

or even

sole

defensive

position.

One

almost

square

tower

(on

the

north-west)

is now

reduced to two

storeys,

though

it

must

have

had at least

one

more because

a

column-shaft

lies

as

a

stretcher

in

the

present

top

course

of

masonry.

At the

centre of the

back

(PLATE

Ioa,

b)

is

a

doorway

into

the

upper

storey,

accessible from

the

wall-walks on

both

the

adjacent

curtains,

which

differ

considerably

in

their

levels;

a

row of

huge

cantilevered blocks

(salvaged

from a

classical

cornice)

provides

a

horizontal

approach

from

the

lower curtain

to

the

threshold,

beyond

which

are smaller

cantilevered blocks

forming

separate

steps

to

the

higher

curtain.

Precedents for these two devices are known only in Hellenistic towers.

The

outer line

is the

earliest

post-classical

example

of

the

two

kinds

of

Hellenistic

proteichisma.

On

most

of

its course it

is a

free-standing,

featureless

wall

that

probably

was

not

much

higher

than a

man

(for

the

top

is

late,

of several

periods);

on the eastern side it

revetted the

scarp

of

the.

ditch

and was

continued

upward

free-standing.

Except

for the

original

tower on

the

south-east corner

where the

floor of the ditch shelves into

the

sea

(PLATE8b),

the

whole

length

of the ditch

was

probably

featureless until

long

after a final

Byzantine

withdrawal.

That occurred in

unknown

circumstances at some

date

before

1167,

by

which

time

Corycus already

belonged

to the

newly

founded Armenian

state of Cilicia.

23

Alexiad i

IoC.

24

Ibid.

ioD.

Eustathius was

ordered also

to

restore

defences

at

Seleucia/Silifke

that

are

likely

to

have

originated

before the

wars with

the

Isaurians

but been

strengthened during

them.

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Thu, 23 Jan 2014 12:21:25 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 11/72

18o

A. W. LAWRENCE

The

subsequent

history

of

Corycus,

both

political

and

architectural,

is reserved for

a

forthcoming

issue

of

Yayla.

Here

all

that need be said is

that

both lines

of

fortification

along

the ditch became more

elaborate,

and the outer

acquired

salients that

encroached

upon

the

floor;

the

Armenians

put

a

drawbridge

across,

and

built

gateways

to serve it

through

both

the outer and the inner line. Most of the salients are in the style of western Europe and must

be works of

even later

owners,

the

Lusignan kings

of

Cyprus

or their Genoese

associates,

who

made the

final

additions

to the inner

line.

(The original

defences

of

the sector had

evidently

been

designed

to

repel unsophisticated

enemies,

and were

inadequate

against

Turks trained

to

siegecraft.)

After the

Muslim

conquest

of the

Armenians,

Corycus

was

held

as an

isolated

Christian

possession;

the

King

of France twice considered whether to use it

for

the base of

a

Crusade

to liberate them.

Eventually,

in

1448,

the

Seljuks

of Karamania

contrived

to

seize

the

fortress,

which

in

1482,

on the extinction

of

their

dynasty,

passed

to the Ottomans and

was allowed to

lapse

into

ruin.

In

many respects

Corycus

is

a

precursor

of

Justinianic

fortifications,

which likewise were

planned

for

defence

by

local,

partially

trained,

militia. For

that

reason,

the

height

of

curtains

and the size of towers at

Corycus

exceed the dimensions normal in forts

garrisoned by

the

Roman

army;25

instead,

they

followed

precedents

in

city

walls,

which must have been manned

principally

by

civilians.

The

designer

had also studied Hellenistic

remains and

may

have been

the

first

to revive their

practices,

which had

again

become

apposite

in

the

changed

conditions

of

warfare,

after five centuries of

Roman disuse.

Someone

of much less

intelligence

was

responsible

for the refortification of

Sparta26

shortly

after the devastation

by

Alaric

in

396;

the

material was collected from

destroyed

buildings

too soon for

it

to become

weathered,

and

put

together

badly,

as

though

hurriedly.

The

entire

acropolis

was

now

(FIG.

I)

enclosed with

a

new

wall

except

where

it

incorporated

the corner

built after

267

(though

with

the

gateway

transferred to

a

slightly

different

position).

There

are, however, only discontinuous, scanty vestiges, here and there. The layout included sectors

that

were,

in

turn,

convex,

concave,

and

straight.

The

towers,

of two or more

periods,

varied

in

size but all

were

larger

than

their

predecessors

beside

the older

corner;

most

were

rectangular

and

spaced

far

apart,

but

some,

obviously

added

at

a

later date

to a

rounded

salient,

were

semicircular and crowded

together.

3.

CONSTANTINOPLE

AND REGIONAL

CAPITALS,

412-C.

450

The walls

of

Constantinople

have

been

published

so

elaborately27

that there

is no occasion

to do more

than summarize the

general

design

of each successive

scheme-in

the

past

tense

to allow for their

more or less ruined

condition. Most

of the circuit

(FIGS.

3, 4, 5)

originated

during

the

(largely

nominal) reign

of Theodosius

II,

408-50.

First,

in

412,

the

construction

began

of a

single

wall

over

7

km

long,

on the landward

boundary

of the

city

from the Sea

of

Marmara

to

the Blachernae suburb

(beyond

which

an older

wall was retained

to the

Golden

Horn).

The

curtains,

some

5

m

thick,

were

not less

than

Io

m

high

at

the

wall-walk,

upon

which stood

a

crenellated

parapet

2

m

high;

the

merlons were

extended

backward

by

short

traverses,

a

means

of reinforcement

and

shelter

for

defenders

that

may

have been

common ever

since the Greeks invented it

(probably

in

the fourth

century B.c.), though

25

Exceptional

dimensions

in the citadel

at

Old

Cairo

(S.

Toy, History

of

Fortification

1955)

54)

could have

provided

for

the

occasional

depletion

of

the

garrison

to subdue trouble

in

the

provinces;

it was the

headquarters

of the

army

in

Egypt.

26

Cf.

n.

4.

27

Die

Landmauer

on

Konstantinopel(1938)

by

F. Krischen-

generalities

and

drawings

restoring original

condition

of

Theodosian

walls;

ii

(i943)

by

B.

Mayer-Plath

and

A. M.

Schneider-piecemeal

survey.

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Thu, 23 Jan 2014 12:21:25 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 12/72

A

SKELETAL HISTORY OF BYZANTINE

FORTIFICATION

181

inevitably very

few

examples

are

preserved.

Double staircases

(of

the

type

now called

Palladian)

were bonded to the inward face of the

wall;

their

converging flights,

a

couple

of

metres

wide,

climbed

upon

arches of

graduated heights

to

a

landing

level with

the

walk,

precisely

as is

shown

in a

Roman

painting

of

an

amphitheatre. Gateways

were

approached

through

the

tallest

arch,

at the centre of

the

thirty-metre support. Towers, spaced usually

60o

to

70

m

apart,

projected

some

io

m

forward from the curtains

and rose

5-6

m

higher,

with

an

external

o9--

50

M

FIG.

3.

Constantinople.

Plan of

Theodosian

system

and final

ditch

(Landmauer)

stair

up

to the

roof,

which was lined with a

crenellated

parapet.

The

towers were

alternately

rectangular,

of

I

o-

I

m

a

side,

and

octagonal

of similar

dimensions,

but no

military advantage

seems to have resulted from this

differentiation;

it

made

the

appearance

more

interesting.

The

lower

part

of each

tower,

opposite

the

curtains,

contained

a

vaulted

room

lit

by

windows too

far out of reach from the floor to have

been intended for

defence;

it was usable for

storage

or

barracks,

and

a

postern

opened

through

the

right

flank,

but the

overriding

purpose

must have

been to save material

in

the structure.

An

upper

room,

entered

from the walk

along

the

curtains,

was

provided

with a

variable number of windows for

catapults;

it was

5

m

high,

normally barrel-vaulted or, if octagonal, domed. The main gateways pierced a curtain between

rectangular

towers

except

in

the case of the

Adrianople

Gate,

where the towers were

hexagonal-probably

not for

military

reasons but to add interest

to

their

appearance.

Aesthetic

as well

as

practical

considerations

may

also have influenced the decision

to face the mortared

rubble of the

wall

with limestone blocks

or

with

dark-red

brickwork,

interrupted

at

several

levels

by

bands

comprising

five courses of

pale

yellow

bricks,

which

go

all the

way

through

for

bonding.

An

earthquake

in

447

wrecked

fifty-seven

towers,

as is not

surprising

in

view of the size

and

height

of the

upper

rooms,

so

great

was the thrust that their

massive

vaulting

could

exert

when

shaken. Their restoration was

undertaken

immediately,

and

accompanied

by

the

building

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Thu, 23 Jan 2014 12:21:25 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 13/72

182

A.

W. LAWRENCE

,

.1o

2

M.

FIG.

4.

Constantinople.

Section of

Theodosian

system

with

rectangular

towers

(Landmauer)

of

a

low outer wall with

small

towers,

more resistant to

shock;

presumably

it

was intended

to

minimize the risk that breaches caused by some future earthquake might again invalidate the

entire

defensive

system.

The

two walls were

separated

by

a

space

of

13-50

m,

reduced to less

than

4

m

where towers

protruded.

No

classical

precedent

for

an

outer wall is known

(unless

a

free-standing

proteichisma

at

Selinus should so rank because of salients that resembled towers

in

plan).

The Asiatic

peoples

had built

strong

outer walls from the Bronze

Age

to the sixth

century

B.C.28

when

one

of

exceptional magnitude

was included

in

the defences of

Babylon,

of which

educated

Byzantines

must

have

read,

for

they

were described

by

Herodotus and

28

There

is no

evidence for

recrudescence

in

Parthian

times;

the

outer

line

at Hatra

seems

a

mere

proteichisma,

I130

m

thick,

with

only

one

visible

salient.

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Thu, 23 Jan 2014 12:21:25 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 14/72

A

SKELETAL HISTORY OF BYZANTINE

FORTIFICATION

183

5

.

9

.

. . .

FIG.

5.

Constantinople.

Section of

Theodosian

system

with

octagonal

and

apsidal

towers,

and

plans

at two

levels

(Landmauer)

later

authors,

down

to

Strabo.

Only

if

there

were

oriental features at

Constantinople

that

could not have been derived from these ancient sources would it be

reasonable

to

postulate

an unverified addiction to outer walls

in

the Sassanian

empire,

then the

dominant

power

in

Western Asia outside the Byzantine territory. In fact, though, the structure at Constantinople

followed

classical,

not

Asiatic,

precedents

in

its most notable features. The wall was solid to

the

exiguous

thickness

of

1.30

m,

and

backed

with a

series of blind

arches,

spanning

the

intervals

of

2

m

between

piers

that

projected

3

m,

in

a

manner

found

in

both

Hellenistic

and

Roman

examples

and,

perhaps contemporaneously,

around the

monastery

of

Daphni

(see

Appendix).

Slits

through

the

frontage-one

at

the centre of each

arch-gave

overlapping

fields of fire. The

walk,

4

m

wide behind the

parapet,

stood at

a

mean

height

of

only

4

m

above the interval between the two

walls,

but a

drop

in

the

ground

almost doubled it

externally,

with the

masonry

of the lower

part

forming

a

revetment to the

curtains,

though

it was

free-standing

at

the

very

base of the

towers,

which

projected

in

their

entirety.

The same effect

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Thu, 23 Jan 2014 12:21:25 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8/10/2019 A Skeletal History of Byzantine Fortification a. W. Lawrence

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/a-skeletal-history-of-byzantine-fortification-a-w-lawrence 15/72

184

A. W. LAWRENCE

would

have resulted

if

a

proteichisma

that lined the

scarp

of

a

ditch had

been

studded with

towers;

we do not know whether there

had

been

any

actual

instance

of that

scheme,

but the

designer clearly

was

thinking

of

a

proteichisma

such as often rose

from

the

floor

of

a

ditch,

revetting

the

scarp,

and

continued

free-standing.

He

may

conceivably

have

complied

with that

practice and set his foundations in a ditch, which would have been obliterated when

(supposedly

c.

iooo)

that now visible was

given

its

final

dimensions,

for the enormous amount

of

spoil

extracted

on

each

occasion seems to have been

spread evenly

on the

intervening

space,

the berm. This

conjecture

could

explain

why

the outer towers were

equipped

to shoot

only

to

a

fairly long

distance-no

slits were

provided

below

a

vaulted room entered

from

the

wall-walk,

and

its

roof

platform

was the

major

defensive

position.

The inner towers

all

overlooked

curtains of the outer

wall and

bore

most

of

the

responsibility

for

its

defence;

the

towers

of the outer wall stood

opposite

the middle of

curtains

in

the inner

wall,

and

were

alternately

rectangular

and

apsidal

in

accordance

with the taste for

repetitive

variation

manifested

in

the

original

Theodosian

system.

At entrances

a

simple gateway through

the

outer

wall was

aligned

with that

in

the

inner,

and a court was

formed,

bounded

on each side

by

a

little

two-storeyed

building

and a door between it and the front of the

original