Jaworski and Kohli 1993

Transcript of Jaworski and Kohli 1993

Bernard J. Jaworski and Ajay K. Kohli

Market Orientation: Antecedentsand Consequences

This research addresses three questions: (1) Why are some organizations more market-oriented thanothers? (2) What effect does a market orientation have on employees and business performance? (3)Does the linkage between a market orientation and business performance depend on the environmentalcontext? The findings from two national samples suggest that a market orientation is related to top man-agement emphasis on the orientation, risk aversion of top managers, interdepartmental conflict and con-nectedness, centralization, and reward system orientation. Furthermore, the findings suggest that a mar-ket orientation is related to overall (judgmental) business performance (but not market share), employees'organizational commitment, and esprit de corps. Finally, the linkage between a market orientation andperformance appears to be robust across environmental contexts that are characterized by varying de-grees of market turbulence, competitive intensity, and technological turbulence.

RECENT years have witnessed a renewed empha-sis on delivering superior quality products and

services to customers (e.g., Bitner 1990; Day andWensley 1988; Parasuraman, ZeithamI, and Berry1985). Because customer needs and expectations con-tinually evolve over time, delivering consistently high-quality products and services requires ongoing track-ing and responsiveness to changing marketplace needs,i.e., being market-oriented. More formally, a marketorientation refers to the organization-wide generationof market intelligence, dissemination of the intelli-gence across departments, and organization-wide re-sponsiveness to it (see Kohli and Jaworski 1990).

Why are some organizations more market-orientedthan others? Remarkably, this fundamental issue hasnot been addressed in any empirical study to date.

Bernard J. Jaworski is Associate Professor in the Department of Mar-keting at the Karl Eller Graduate School of Management, University ofArizona, Tucson and currently Visiting Associate Professor, HarvardBusiness School. Ajay K. Kohli is Associate Professor in the Departmentof Marketing Administration, College of Business Administration, Uni-versity of Texas—Austin. The authors express their thanks to Tom Kin-near for his direction and to three anonymous reviewers and Rick Stae-lin for their helpful suggestions. They gratefully acknowledge the supportthey received from the Marketing Science Institute and the College ofBusiness Administration at the University of Texas—Austin. The au-thors contributed equally to the paper.

Several propositions pertaining to the antecedents ofa market orientation have recently been advanced byKohli and Jaworski (1990). However, as they pointout, these propositions need empirical validation.

Furthermore, although a market orientation is pos-ited to lead to greater customer satisfaction and or-ganizational commitment of employees, these rela-tionships also have not been subjected to empiricaltesting. In an encouraging step, Narver and Slater(1990) report empirical support for the often-assumedor implied relationship between a market orientationand performance. However, arguments have been ad-vanced in the literature suggesting that a market ori-entation may have a strong or a weak effect on busi-ness performance, depending on the environmentalconditions such as market turbulence and competitiveintensity (e.g., see Houston 1986). Such potentialvariations in the impact of a market orientation onperformance remain to be empirically investigated.

The purpose of this research is to address the voidsin knowledge noted above. Specifically, two nationalsamples are investigated to determine (1) the effect ofthree sets of factors posited in the literature on a mar-ket orientation, (2) the hypothesized effect of a marketorientation on business performance and employees,and (3) the role of environmental characteristics in

Journat of tVlart(etingVol. 57 (July 1993). 53-70 Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences/53

moderating the relationship between market orienta-tion and business performance. This research shedslight on the relative importance of a number of or-ganizational factors that are posited to help or hindera market orientation, as well as the nature of the im-pact of the orientation on employees and business per-formance.

In addition to testing theory, the research findingsare useful to managers for undertaking change effortsdirected at building market-oriented organizations (seealso Day 1990). Furthermore, this research empiri-cally addresses the issue of whether all businessesshould focus on a market orientation. This is an im-portant consideration, because devoting resources todevelop a market orientation potentially may bewasteful if the orientation does not lead to higher per-formance in certain business environments, such asthose with low competitive intensity. Finally, this re-search sheds light on the impact of a market orien-tation on the employees of an organization, an aspectof market orientation that has been underemphasizedin previous writings.

First, a brief review of the literature on marketorientation will be provided, and hypotheses pertain-ing to the antecedents and consequences of the ori-entation will be discussed. While internal organiza-tional as well as external factors (e.g., competitiveintensity) can be argued to be antecedents of marketorientation (see Lusch and Laczniak 1987), the pres-ent study focuses on internal factors. This perspectiveembodies a more applied orientation, because man-agers have more control over internal antecedentscompared to external ones. Next, two large-scale fieldinvestigations undertaken to test these hypotheses aredescribed, followed by a discussion of the researchresults. The paper will conclude with a discussion ofthe managerial relevance of the findings and futureresearch directions.

Background and HypothesesIntroduced in the early 1950s, the marketing concept(the philosophical foundation of a market orientation)represents a cornerstone of marketing thought (seeBorch 1957; McKitterick 1957). However, given itswidely acknowledged importance, it is remarkable howlittle research has focused on the subject. Only a smallset of conceptual articles exists that offers preliminarysuggestions for engendering a market orientation (e.g.,Felton 1959; Stampfl 1978; Webster 1988). And thefew empirical studies that have been conducted on thesubject primarily concern the extent to which organ-izations have adopted the marketing concept, ratherthan the antecedents or consequences of a market ori-entation (e.g., Barksdale and Darden 1971; Hise 1965;Lusch, Udell, and Laczniak 1976; McNamara 1972).

There is, however, a strong resurgence of academicand practitioner interest in market orientation (e.g.,Deshpande and Webster 1989; Deshpande, Farley, andWebster 1993; Houston 1986; Narver and Slater 1990;Olson 1987; Linden 1987; Shapiro 1988).

Using a theories-in-use approach described byZaitman, LeMasters, and Heffring (1982), Kohli andJaworski (1990) define a market orientation as com-posed of three sets of activities: (1) organization-widegeneration of market intelligence pertaining to currentand future customer needs, (2) dissemination of theintelligence across departments, and (3) organization-wide responsiveness to it. Furthermore the respon-siveness component is defined as being composed oftwo sets of activities—response design (i.e., usingmarket intelligence to develop plans) and responseimplementation (i.e., executing such plans). This def-inition focuses on specific behaviors and therefore fa-cilitates operationalizing the market orientation con-struct.

The three-component conceptualization also makespossible a more focused analysis of the role of anygiven antecedent of a market orientation. (As will bediscussed later, the same antecedent may potentiallyhave an opposite effect on the different componentsof a market orientation.) Therefore, the authors adoptthe three-component conceptualization of market ori-entation in the present study. It is useful to note that,traditionally, customers have been considered to bethe primary focus of a market orientation. Consistentwith Lusch and Laczniak (1987), a somewhat broaderperspective is embraced, in that additional forces in amarket (e.g., competition, technology, regulation) areconsidered to belong to the domain of the market ori-entation construct.

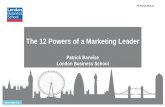

In order to guide the following discussion, a figureidentifying the key constructs included in the study isprovided (Figure 1). Based on the literature subse-quently discussed, three sets of antecedents pertainingto top management, interdepartmental factors, and or-ganizational systems are hypothesized to be related tomarket orientation, and market orientation is hypoth-esized to be related to employee commitment, espritde corps, and business performance. Finally, the linkbetween a market orientation and business perfor-mance is hypothesized to be moderated by market tur-bulence, competitive intensity, and technological tur-bulence. Because a fairly detailed discussion of thehypotheses is provided by Kohli and Jaworski (1990),only a brief synthesis is offered in order to conservespace for discussing the empirical aspects of the re-search in detail.

Antecedents to a Market OrientationThe first set of antecedents included in the present studypertains to top management in an organization. Sev-

54/Journal of Marketing, July 1993

FIGURE 1Antecedents and Consequences of Market Orientation

TOP MANAGEMENT

• Emphasis• Risk Aversion

INTERDEPARTMENTALDYNAMICS

• Conflict• Connectedness

ORGANIZATIONAT.SYSTEMS

• Formalization• Centralization• Departmentalization• Reward Systems

•

MARKET ORIENTATION

• Intelligence Generation• Intelligence Dissemination• Responsiveness

EMPLOYEES

• OrganizationalCommitment

• Esprit de Corps

ENVIRONMENT

• Market Turbulence• Competitive Intensity• Technological Turbulence

BUSINESSPERFORMANCE

eral authors suggest that top managers play a criticalrole in shaping an organization's values and orienta-tion (e.g., see Felton 1959; Hambdck and Mason 1984;Webster 1988). The central theme in these writings isthat unless an organization gets clear signals from topmanagers about the importance of being responsive tocustomer needs, the organization is not likely to bemarket-oriented (see Levitt 1969, p. 244; Webster 1988,p. 37). Top management reinforcement of the impor-tance of a market orientation is likely to encourageindividuals in the organization to track changing mar-kets, share market intelligence with others in the or-ganization, and be responsive to market needs. There-fore:

H,: The greater the top management emphasis on a mar-ket orientation, the greater the (1) market intelligencegeneration, (2) intelligence dissemination, and (3) re-sponsiveness of the organization.

A second antecedent of market orientation relatesto top managers' risk posture. Responsiveness tochanging market needs often calls for the introductionof new products and services to match the evolvingcustomer needs and expectations. But new products,services, and programs often run a high risk of failureand tend to be more salient than established products.Kohli and Jaworski (1990) argue that if top manage-ment demonstrates a willingness to take risks and to

accept occasional failures as being natural, juniormanagers are more likely to propose and introduce newofferings in response to changes in customer needs.By contrast, if top management is risk aversive andintolerant of failures, subordinates are less likely tofocus on generating or disseminating market intelli-gence or responding to changes in customer needs.Therefore, it can be expected that

H2: The greater the risk aversion of top management, thelower the (1) market intelligence generation, (2) in-telligence dissemination, and (3) responsiveness of theorganization.

The second set of factors that is hypothesized tohave an effect on a market orientation pertains to in-terdepartmental dynamics. A particularly salient fac-tor proposed to affect a market orientation is inter-departmental conflict, which refers to the tension amongdepartments arising from the incompatibility of actualor desired responses (cf. Gaski 1984; Raven andKruglanski 1970, p. 70). Several authors point to in-terdepartmental conflict as an inhibitor of a marketorientation (see Levitt 1969; Lusch, Udell and La-czniak 1976; Felton 1959). Essentially, interdepart-mental conflict is likely to inhibit communication acrossdepartments (cf. Ruekert and Walker 1987), therebylowering market intelligence dissemination. In addi-tion, tension among departments is likely to inhibit a

Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences / 55

concerted response by the departments to market needs,thereby hampering a market orientation. No effectsare expected for intelligence generation, because in-terdepartmental conflict should not affect the infor-mation acquisition process in a given department.Hence:

H3: The greater the interdepartmental conflict, the lowerthe (1) market intelligence dissemination and (2) re-sponsiveness of the organization.

A market orientation is also posited to be affectedby interdepartmental connectedness, which refers tothe degree of formal and informal direct contact amongemployees across departments. Several related streamsof research suggest that connectedness facilitates in-teraction and exchange of information, as well as theactual utilization of the information (see Cronbach andAssociates 1981; Deshpande and Zaltman 1982; Pat-ton 1978). Therefore, it can be expected that the greaterthe extent to which individuals across departments aredirectly connected (or networked), the more they arelikely to exchange market intelligence and respond toit in a concerted fashion (see also Kohli and Jaworski1990). As before, no effects are expected for the in-telligence generation component. Thus:

H4: The greater the interdepartmental connectedness, thegreater the (1) market intelligence dissemination and(2) responsiveness of the organization.

The third set of antecedents that is proposed toaffect a market orientation pertains to organizationalstructure and systems. Three structural variables—formalization, centralization, and departmentaliza-tion—must first be considered. Formalization repre-sents the degree to which rules define roles, authorityrelations, communications, norms and sanctions, andprocedures (Hall, Haas, and Johnson 1967). Central-ization refers to the inverse of the amount of dele-gation of decision-making authority throughout anorganization and the extent of participation by orga-nizational members in decision-making (Aiken andHage 1968). Departmentalization refers to the numberof departments into which organizational activities aresegregated and compartmentalized.

Research to date suggests that both formalizationand centralization are inversely related to informationutilization (see Deshpande and Zaltman 1982; Hageand Aiken 1970; Zaltman, Duncan, and Holbek 1973).In the present context, information utilization corre-sponds to designing programs in response to marketintelligence. Therefore, as Stampfl (1978) argues, itappears that formalization and centralization are in-versely related to an organization's responsiveness.Similarly, Lundstrom (1976) and Levitt (1969) dis-cuss departmentalization as a barrier to communica-tion and, hence, to market intelligence dissemination.

Interestingly, there is reason to believe that the or-

ganizational structure may not affect the three com-ponents of a market orientation in the same fashion.As noted earlier, because a market orientation essen-tially involves doing something new or different inresponse to market conditions, it may be viewed as aform of innovative behavior. Zaltman, Duncan, andHolbek (1973, p. 62) characterize innovative behavioras being composed of two stages: (1) the initiationstage (i.e., awareness and decision-making) and (2)the implementation stage (i.e., carrying out the de-cision). In the present context, the initiation stage cor-responds to intelligence generation, dissemination, andthe design of organizational response, whereas the im-plementation stage corresponds to the actual organi-zational response.

Zaltman, Duncan, and Holbek (1973) draw on nu-merous studies to argue that organizational dimen-sions such as formalization, centralization, and de-partmentalization may have opposite effects on the twostages of the innovative behavior. In particular, theyindicate that, whereas these variables may hinder theinitiation stage of innovative behavior, the same vari-ables may actually facilitate the implementation stageof innovative behavior. This suggests that formali-zation, centralization, and departmentalization may beinversely related to market intelligence generation,dissemination, and response design but positively re-lated to response implementation. Therefore, it is hy-pothesized that:

H5: The greater the formalization, (1) the lower the in-telligence generation, dissemination, and response de-sign and (2) the greater the response implementation.

He: The greater the centralization, (1) the lower the in-telligence generation, dissemination, and response de-sign and (2) the greater the response implementation.

H7: The greater the departmentalization, (1) the lower theintelligence generation, dissemination, and responsedesign and (2) the greater the response implementa-tion.

The last antecedent investigated in this study re-lates to the measurement and reward system that is inplace within an organization. Literature on the subjectsuggests that measurement/reward systems are instru-mental in shaping the behaviors of employees (cf. An-derson and Chambers 1985; Jaworski 1988; Lawlerand Rhode 1976; Hopwood 1974). In the present con-text, Webster (1988, p. 38) argues that " . . . the keyto developing a market-driven, customer-orientedbusiness lies in how managers are evaluated and re-warded." He observes that if managers primarily areevaluated on the basis of short-term profitability andsales, they are likely to focus on these criteria andneglect market factors such as customer satisfactionthat assure the long-term health of an organization.Consistent with the preceding arguments, it can be ex-pected that individuals in organizations that empha-

56 / Journal of Marketing, July 1993

size customer satisfaction and market-oriented behav-ior as bases for administering rewards will more readilygenerate market intelligence, disseminate it internally,and be responsive to market needs. That is:

Hg: The greater the reliance on market-based factors forevaluating and rewarding managers, the greater the(1) market intelligence generation, (2) intelligencedissemination, and (3) responsiveness of the organi-zation.

Consequences of a Mariiet OrientationA market orientation is frequently posited to improvebusiness performance. The argument is that organiza-tions that are market-oriented, i.e., those that trackand respond to customer needs and preferences canbetter satisfy customers and, hence, perform at higherlevels. The study by Lusch and Laczniak (1987) pro-vides some support for this relationship. A more re-cent study by Narver and Slater (1990) also offers em-pirical support for the relationship posited betweenmarket orientation and business performance. Theformal hypothesis to be tested is:

Hg: The greater the market orientation of an organization,the higher its business perfonnance.

The next set of consequences examined in the studyfocus on organizational employees. The research re-ported by Kohli and Jaworski (1990) suggests that amarket orientation affords a number of psychologicaland social benefits to employees. Specifically, a mar-ket orientation is argued to lead to a sense of pride inbelonging to an organization in which all departmentsand individuals work toward the common goal of sat-isfying customers. Accomplishment of this objectiveis posited to result in employees sharing a feeling ofworthwhile contribution, a sense of belongingness, and,therefore, commitment to the organization. The for-mal testable hypothesis is:

H|o: The greater the market orientation, the greater the (1)esprit de corps and (2) organizational commitment ofemployees.

As noted earlier, several scholars suggest that theenvironmental context of an organization is likely toinfluence its level of market orientation. As a result,organizations in more competitive environments maybe expected to be more market-oriented (Lusch andLaczniak 1987). Several scholars draw on this generalargument to suggest that the importance of market ori-entation varies with the environmental context (seeBennett and Cooper 1981; Houston 1986; Tauber 1974).Stated differently, they argue that the linkage betweenmarket orientation and performance depends on theenvironmental characteristics of an organization.

In the present study, three environmental charac-teristics are included that have been proposed by Kohliand Jaworski (1990) to influence the linkage between

a market orientation and performance. First, marketturbulence—the rate of change in the composition ofcustomers and their preferences—is considered. Or-ganizations that operate in the more turbulent marketsare likely to have to modify their products and ser-vices continually in order to satisfactorily cater to cus-tomers' changing preferences. By contrast, an orga-nization's products and services are likely to requirerelatively little modification in stable markets wherethe customers' preferences do not change very much.Therefore, businesses operating in the more turbulentmarkets are likely to have a greater need to be market-oriented, (i.e., to track and respond to evolving cus-tomer preferences) compared to businesses in stablemarkets. In other words, a market orientation is likelyto be more strongly related to performance in turbu-lent markets than in stable markets. Stated formally:

H|,: The greater the market turbulence, the stronger therelationship between a market orientation and busi-ness performance.

A second environmental factor that may be arguedto moderate the linkage between a market orientationand business perfomiance is competitive intensity. AsHouston (1986) and Kohli and Jaworski (1990) ob-serve, in the absence of competition, an organizationmay perfonn well, even if it is not very market-ori-ented, because customers are "stuck" with the orga-nization's products and services. By contrast, underconditions of high competition, customers have manyaltemative options to satisfy their needs and wants.As a result, an organization that is not very market-oriented is likely to lose customers to competition andfare poorly, so a market orientation is expected to bea more important determinant of performance underconditions of high competitive intensity. That is:

H]2: The greater the competitive intensity, the stronger therelationship between a market orientation and busi-ness perfonnance.

The third environmental factor posited to moder-ate the relationship between a market orientation andbusiness performance is technological turbulence—therate of technological change. A market orientation es-sentially is a means to developing a competitive ad-vantage, because it enables an organization to under-stand customer needs and offer products and servicesthat meet those needs. While this is important, theremay be altemative avenues to gaining a competitiveadvantage. To the extent such altemative avenues ex-ist, the importance of a market orientation is likely tobe diminished. One such avenue is technology. Or-ganizations that work with nascent technologies thatare undergoing rapid change may be able to obtain acompetitive advantage through technological innova-tion, thereby diminishing—but not eliminating—theimportance of a market orientation. By contrast, or-

Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences / 57

ganizations that work with stable (mature) technolo-gies are relatively poorly positioned to leverage tech-nology for gaining a competitive advantage and mustrely on market orientation to a greater extent. For ad-ditional arguments along similar lines, see Bennett andCooper (1981), Houston (1986), Kaldor (1971), andTauber (1974). The discussion above suggests that:

H13: The greater the technological turbulence, the weakerthe relationship between a market orientation andbusiness performance.

Data CollectionSampie /The first sample was drawn from the member com-panies of the Marketing Science Institute (MSI) andthe top 1000 companies (in sales revenues) listed inthe Dun and Bradstreet Million Dollar Directory. Amultiple-informant design was employed in this sam-ple.

A letter from the MSI executive director was mailedto a senior executive at all forty-nine MSI membercompanies requesting that they participate in the study.Each executive was asked to provide the names of asenior marketing and a senior nonmarketing executivein one or more of the SBUs of the company for sub-sequent contact by the researchers. Out of a total offorty-nine companies, thirteen companies agreed toparticipate in the study and provided names of indi-viduals in twenty-seven SBUs. The names of both amarketing and nonmarketing executive were providedfor each SBU. A copy of the questionnaire, togetherwith a personalized letter and a retum envelope, wasmailed to the two informants in each SBU. A re-minder postcard was mailed to each individual ap-proximately 1 week after the initial mailing. After ap-proximately 3 weeks, a replacement copy of thequestionnaire, together with another personalized let-ter, was mailed to the informants. The response ratewas 88.9% for the marketing executives and 77.8%for the nonmarketing executives.

From the D&B sampling frame, 500 companieswere chosen from among the top 1000 by selectingevery altemate listing. The initial contact was madewith the CEO of each company in a personalized let-ter requesting the company's participation in the study.A total of twenty-one companies could not be reachedbecause of incorrect addresses and CEO successions,resulting in an effective base of 479 companies. TheCEOs were requested to provide the names of two se-nior executives (one marketing and the other non-marketing) in their SBUs to serve as informants. Atotal of 102 companies agreed to participate, and 229SBU names were obtained. Names were provided for206 marketing and 187 nonmarketing executives. In-

formants in these SBUs were then contacted directlyby the researchers and requested to complete and re-tum the study questionnaire according to the proce-dure described for the MSI companies. The responserate was 79.6% for the marketing executives and 70%for the nonmarketing executives.

These procedures resulted in responses from a to-tal of 222 business units. The market share for thesebusiness units ranges from 1% to 100%, with an av-erage share of 30%. For the purposes of analysis, theresponses of the two informants were averaged to ob-tain scores for each business unit. In the relatively fewinstances where only one informant provided the data,the responses were used in the original form.

Sampie iiIn order to cross-validate the fmdings from the sampleabove, data were obtained from a second sample. Thesampling frame for this group was the American Mar-keting Association membership roster, which pro-vided the names of additional informants. From thissampling frame, 500 names were selected at random,after first eliminating those whose titles suggested thatthey were relatively low in their organizational hier-archy. From this set, thirteen individuals could not bereached because of incorrect addresses, resulting in aneffective base of 487. The 3-wave mailing proceduredescribed earlier was used to obtain data from thissample. A total of 230 responses were obtained, fora response rate of 47.2%.

Instrument Development andRefinement

The study used existing scales for measuring the or-ganizational structure constructs of formalization,centralization, and departmentalization. Scales for theother constructs included in the study were not avail-able in the literature. Therefore, the first step entailedthe development of new scales for these constructs.The following 4-phase iterative procedure was adoptedfor the purpose.

First, the authors independently generated a largepool of items for each of the constructs included inthe study. Care was taken to tap the domain of eachconstruct as closely as possible. For example, multi-ple items were generated to correspond to each of thethree components of market orientation. From this poolof items, a subset was selected using the criteria ofuniqueness and the ability to convey "different shadesof meaning" to informants (see Churchill 1979). Sev-eral items were reverse-scored in order to minimizeresponse set bias.

Next, because of the centrality of the market ori-entation scale, its items were tested for clarity and ap-propriateness in personally administered pretests with

58 / Joumal of Marketing, July 1993

twenty-seven managers from marketing as well asnonmarketing departments and also from top man-agement levels. The managers were asked to completea questionnaire that included the items and indicateany ambiguity or other difficulty they experienced inresponding to the items, as well as offer any sugges-tions they deemed appropriate. Based on the feedbackreceived from the managers, some items were elimi-nated, others were modified, and additional items weredeveloped.

This was followed by another phase of pretests inwhich the scales for all constructs were clearly markedas such and presented to seven academic experts, whowere asked to critically evaluate the items from thestandpoint of domain representativeness, item speci-ficity, and clarity of construction. Based on the de-tailed critique received, some items were eliminatedand others revised to improve their specificity andprecision.

The items that were developed and refined weresubjected to yet another phase of pretests involvingpersonal interviews with seven managers, who wereasked to complete a questionnaire that included themeasure items as they applied to their business unit.At this stage, very few concems were raised and onlyvery minor refinements were made. A brief descrip-tion of the final scale items follows. The completescales are provided in the Appendix.

Market orientation was measured by a 32-itemscale. Of these items, ten pertain to market intelli-gence generation, eight to intelligence dissemination,and fourteen to responsiveness at the business unit level.Of the fourteen responsiveness items, seven tap theextent to which an organization develops plans in re-sponse to market intelligence (response design), andthe remaining seven assess the actual implementationof these plans (response implementation). Consistentwith Lusch and Laczniak (1987), items that tapped thethree components were interwoven with issues relatedto the needs and preferences of customers and end users,competitiors' moves, and regulatory trends. Sampleitems for the three components were: (1) "In our busi-ness unit, intelligence on our competitors is generatedindependently by several departments," (2) "We haveinterdepartmental meetings at least once a quarter todiscuss market trends and developments," and (3)"Customer complaints fall on deaf ears in this busi-ness unit" (reverse-scored). Each item was scored ona 5-point scale, ranging from "strongly disagree" to"strongly agree."

Top management emphasis on market orientationand risk aversion were measured by two separate scales.The first scale was composed of four items (e.g., "Topmanagers repeatedly tell employees that this businessunit's survival depends on its adapting to marketneeds"). Items in this scale focused on the verbal re-

inforcement top managers provided for market-ori-ented activities. The risk aversion scale was com-posed of six items (e.g., "Top managers in this businessunit like to "play it safe"), and tapped top managers'disposition toward innovative actions in the face ofrisk and uncertainty. Items for each scale were scoredon a 5-point scale, ranging from "strongly disagree"to "strongly agree."

The two constructs pertaining to interdepartmentaldynamics—conflict and connectedness—were eachmeasured by 7-item scales. The conflict items per-tained to the extent to which the goals of the differentdepartments were incompatible and tension prevailedin interdepartmental interactions (e.g., "Protecting one'sdepartmental turf is considered to be a way of life inthis business unit"). The connectedness items tappednotions of the extent to which individuals in a de-partment were networked to various levels of the hi-erarchy in other departments (e.g., "In this businessunit, it is easy to talk with virtually anyone you needto, regardless of rank or position"). Items for eachscale were scored on a 5-point scale, ranging from"strongly disagree" to "strongly agree."

Formalization and centralization were measuredby the widely used scales developed by Aiken andHage (1966, 1968). The 9-item formalization scaleassessed the extent to which jobs in the organizationwere codified, and there was an emphasis on observ-ing rules (e.g., "How things are done around here isleft up to the person doing the work" [reverse-coded]).The 5-item centralization scale assessed the degree ofhierarchical authority within an organization (e.g., "Aperson who wants to make his own decisions wouldbe quickly discouraged here"). All items were scoredon a 5-point scale, ranging from "strongly disagree"to "strongly agree."

Departmentalization was measured by a count ofthe number of departments in the business unit. Re-ward system orientation was measured by a 6-itemscale that assessed the extent to which customer re-lations, customer satisfaction, and market-orientedbehaviors were used to evaluate and reward individ-uals in the organization. For example, "Customer sat-isfaction assessments influence senior managers' payin this business unit." A 5-point scoring format (1 =strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) was employedfor these items.

Market turbulence, competitive intensity, andtechnological turbulence were measured by three scalescomposed of six, six, and five items, respectively. Theitems for the market turbulence scale assessed the ex-tent to which the composition and preferences of anorganization's customers tended to change over time(e.g., "We are witnessing demand for our productsand services from customers who never bought thembefore"). Competitive intensity scale items assessed

Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences / 59

the behavior, resources, and ability of competitors todifferentiate (e.g., "Anything that one competitor canoffer, others can match readily"). Technological tur-bulence items tapped the extent to which technologyin an industry was in a state of flux (e.g., "The tech-nology in our industry is changing rapidly"). A 5-pointscoring format (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = stronglyagree) was employed for all items.

Business performance was measured using twodistinct approaches reflected in the literature—^judg-mental as well as objective measures. The judgmentalmeasure asked informants for their assessment of theoverall perfonnance of the business and its overallperfonnance relative to major competitors, rated on a5-point scale ranging from "poor" to "excellent." Theobjective measure was the dollar share of the servedmarket.

Organizational commitment and esprit de corpswere measured by two 7-item scales. The organiza-tional commitment scale items tapped the extent towhich a business unit's employees were fond of theorganization, saw their future tied to that of the or-ganization, and were willing to make personal sacri-fices for the business unit (e.g., "Employees often goabove and beyond the call of duty to ensure this busi-ness unit's well-being"). The esprit de corps scale as-sessed the extent to which a team spirit prevailed inthe organization (e.g., "People in this business unitare genuinely concerned about the needs and prob-lems of each other"). All items were scored on a 5-point scale, ranging from "strongly disagree" to"strongly agree."

Each of the scales described above was refined inthe following manner. The reliability of each scale wasestimated by computing its coefficient alpha. Itemsthat exhibited low inter-item correlations were elim-inated, in order to improve the internal consistency ofthe scales. The reliability coefficient of each of therefined scales is reported in the Appendix (except forthe overall responsiveness construct, which has a re-liability coefficient of .89). As may be seen from theAppendix, the refined scales generally have good tohigh reliability coefficients that exceed the levels rec-ommended by Nunnally (1978).

Analyses and ResultsThe data obtained from Sample I were analyzed toassess the degree of congruence between the two in-formants. First, the difference in the ratings of the twoinformants for each of the twenty-six constructs in-cluded in the study was computed. The average ab-solute differences for twenty-one of the twenty-sixconstructs were less than 1.0. In the case of five con-structs, the average absolute differences ranged from1.01 to 3.86. Given that most scales include multiple

items, each rated on a 5-point scale, the differencesnoted were extremely small (on the order of 5% orless) and seemed to indicate the lack of a systematicbias in one direction or another in the reports of themarketing and nonmarketing managers.

Second, for each of the constructs, the correlationbetween the responses of the marketing executives andnonmarketing executives was computed. In general,the correlations are moderate and positive (.09, .17,.35,.28,.39,.29, .24, - . 07 , .31, .36, .52,.84,.02,.29, .17, .24, .18, .26, .42, .53, .37, .33, .51, .17,.33, .34). Although the two reports were positivelycorrelated, the correlations were not perfect, whichsuggests that the two informants were keying in ondifferent perspectives in providing their responses. (Thelack of f)erfect congruence between the informants wasentirely consistent with the results from previousmultiple-informant studies (e.g.. Silk and Kalwani(1982) reported in the literature.) Therefore, the scoresobtained from the two informants were averaged toderive the score for each construct, in an attempt toobtain more complete measurement of the focal or-ganizational characteristics.

Next, the scores for market orientation (and theother multi-item constructs) were computed by equallyweighting and adding the corresponding item scores.(As a result, the market orientation score was the un-weighted sum of the three components of generation,dissemination, and responsiveness.) The mean scoreof market orientation was 113.95, with a standard de-viation of 15.80 and a range of 68.5 to 150 (out of apossible range of 31 to 155). The correlation betweenthe generation and dissemination component was .62,between dissemination and responsiveness .70, andbetween responsiveness and generation .55. Further-more, the correlations between the overall market ori-entation and the generation, dissemination, and re-sponsiveness components were .79, .88, and .92,respectively.

The first nine hypotheses (H, through H9) relatedto the antecedents of a market orientation. These weretested by estimating the following regression equa-tions:

y, =Y2 =

+ e,+ e2+ e,+ e.

where y, denotes overall market orientation, Y2 throughY4 denote market intelligence generation, market in-telligence dissemination, and responsiveness, respec-tively, and X| through Xg correspond to (1) top man-agement emphasis on market orientation, (2) topmanagement risk aversion, (3) interdepartmental con-fiict, (4) interdepartmental connectedness, (5) for-

60/Joumal of Marketing, July 1993

malization, (6) centralization, (7) departmentaliza-tion, and (8) reward system orientation. The e's arethe error terms. Because interdepartmental confiict andconnectedness were hypothesized to affect intelli-gence dissemination and responsiveness, but not in-telligence generation (H3, H4), confiict and connect-edness were not included as predictors of intelligencegeneration in the second equation above. The resultsobtained from estimating the four equations withSample I and Sample II are provided in Tables 1 and2.

Additionally, H5 through H7 hypothesized oppo-site effects of formalization, centralization, anddepartmentalization on the two components ofresponsiveness—response design and responseimplementation. Accordingly, two additional regres-sion equations were estimated by incorporating re-sponse design and response implementation as the de-pendent variables and the eight independent variablespreviously noted. The results obtained for the effects

of formalization, centralization, and departmentali-zation on the two components of responsiveness inboth samples were identical to those obtained for overallresponsiveness reported in Tables 1 and 2.

Hypotheses 9 and 10 pertained to the effect of amarket orientation on business performance and em-ployees' organizational commitment and esprit de corps.These were tested by regressing performance (using,in turn, the judgmental measure as well as the objec-tive measure of market share) on market orientation.To control for the effects of additional determinantsof performance, six control variables were incorpo-rated as independent variables in the regression equa-tions. The control variables related to competitive in-tensity, buyer power, supplier power, entry barriers,pressure from substitute products, and product qual-ity. The literature suggests these variables to be im-portant determinants of performance (e.g., Bouldingand Staelin 1990; Jacobson and Aaker 1987; Porter1980). Measures of these variables were specifically

TABLE 1^Antecedents of a Market Orientation: Standardized Regression Coefficients Estimated With Sample I

Dependent VariablesIndependent

VariablesMarket

OrientationIntelligenceGeneration

IntelligenceDissemination Responsiveness

Top Management EmphasisTop Management Risk AversionInterdepartmental ConflictInterdepartmental ConnectednessFormalizationCentralizationDepartmentalizationReward System Orientation

N

.24***ns

- .17*.20**ns

- .22 * *ns

.30***

.63134

.27***ns——nsnsns

.39***

.34144

.25***ns

- . 2 7 * * *nsns

- .14*ns

.24***

.49154

.20**- . 2 4 * * *- . 23 * *

nsns

- . 2 2 * *ns

.16*

.54150

***p < .001**p < .01•p < .05

TABLE 2Antecedents of a Market Orientation: Standardized Regression Coefficients Estimated With Sample II

IndependentVariables

Top Management EmphasisTop Management Risk AversionInterdepartmental ConflictInterdepartmental ConnectednessFormalizationCentralizationDepartmentalizationReward System OrientationR^N

MarketOrientation

.24***ns

- . 2 8 * * *.22**nsnsns

. 3 1 * * *

.58123

Dependent VariablesIntelligenceGeneration

.20*ns

ns- .34**

ns.38***.33130

IntelligenceDissemination

.28***ns

- .20*.27**nsnsns

.20**

.38138

Responsiveness24***

- . 12*- . 3 2 * * *

nsnsnsns

.19**

.55138

***p < .001**p < .01*p < .05

Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences / 61

developed for the study. Similarly, employees' or-ganizational commitment and esprit de corps wereseparately regressed on market orientation and thecontrol variables to test H9 and Hio. The results ob-tained are reported in Tables 3 and 4.

Finally, H,, thru H,3 hypothesized that the impactof a market orientation was contingent upon the levelof market turbulence, competitive intensity, and tech-nological turbulence. To test for the moderating effectof the three moderator variables, a split group analysiswas performed, with both Sample I and Sample IIseparately (see Amold 1982). First, the sample wassorted in ascending order of a moderator variable (e.g.,market turbulence) and then it was split at the medianto form two groups, one with relatively low marketturbulence and the other with relatively high marketturbulence. Next, perfonnance was regressed on mar-ket orientation and the six control variables in the fullsample, while allowing all regression coefficients totake on different values in the two subgroups.

Then, the regression equation was reestimated, thistime constraining the coefficient associated with mar-ket orientation to take on the same value in the twosubgroups. The Chow (1960) test was performed toassess the statistical significance of the difference inthe regression coefficients of the market orientationvariable across the low and high market turbulencesub-groups. The hypothesized moderating effects ofcompetitive intensity and technological turbulence weretested in a similar fashion by re-sorting the samplesusing these variables in turn and proceeding as de-scribed.

Findings and DiscussionIn this section, the focus is on the substantive inter-pretation of the results and the emergent findings. Ad-ditionally, several methodological issues that are ger-mane to the substantive interpretation of the resultsare discussed.

TABLE 3Consequences of a Market Orientation: Standardized Regression Coefficients Estimated With Sample I

IndependentVariables

Dependent VariablesOverall

PerformanceMarketShare

OrganizationalCommitment

Espritde Corps

Market OrientationProduct QualityCompetitive IntensityBuyer PowerSupplier PowerEntry BarriersSubstitutes

N

.23**

.24**nsnsnsnsns.18145

nsns.39***ns

.22*nsns.06112

44***.18*nsnsnsnsns.31153

. 5 1 * * *

.18*nsnsnsnsns.40153

*»»p < .001**p < .01*p < .05

TABLE 4Consequences of a Market Orientation: Standardized Regression Coefficients Estimated

With Sample II

IndependentVariables

Market OrientationProduct QualityCompetitive IntensityBuyer PowerSupplier PowerEntry BarriersSubstitutes

N

OverallPerformance

.36***nsnsnsnsnsns.25136

Dependent VariablesMarketShare

nsns

- . 2 1 *nsnsnsns.1189

OrganizationalCommitment

.66***nsnsnsnsnsns.50139

Espritde Corps

.58***nsnsnsnsnsns.39135

•p < .001**p < .01*p < .05

62 / Journal of Marketing, July 1993

First, focusing on the antecedents of a market ori-entation, there is strong convergence in the findingsfrom the two samples. The only exceptions relate tothe role of interdepartmental connectedness and or-ganizational centralization (see Tables 1,2). Overall,the results suggest that several factors drive the mar-ket orientation of a business. The amount of emphasistop managers place on a market orientation appears toaffect the generation of market intelligence (b = .27,p < .001, Sample I, b = .20, p < .05, Sample II),its dissemination within the organization (fc = .25, p< .001, Sample I, b = .28, p < .001, Sample II),and the responsiveness of the organization {b = .20,p < .01, Sample I, b = .24, p < .001, Sample II).Therefore, it appears important that top managerscontinually emphasize the need for ongoing trackingand responding to market developments to employ-ees. Top managers' risk aversion does not appear toaffect intelligence generation or dissemination, but itseems to have a negative effect on the responsivenessof the organization (b = - .24 , p < .001, Sample I;b = — .\2, p < .05, Sample II). These findings sup-port the earlier expectation that responding to marketdevelopments entails some amount of risk and that iftop managers are unwilling to assume these risks, theorganization is less likely to be responsive to thechanging preferences of customers.

Interdepartmental conflict, as expected, appears toinhibit intelligence dissemination {b = — .21, p < .001,Sample I, b = - .20 , p < .05, Sample II) as well asthe responsiveness of an organization (b = — .23, p< .01, Sample I, b = - . 32 , p < .001, Sample II).This supports the expectation that individuals in or-ganizations in which tension prevails across depart-ments are less likely to be willing to share market in-formation or to work in concert with other departmentsto satisfy customer needs and expectations.

Results from both samples suggest that connect-edness among departments promotes a market orien-tation. The results from Sample II suggest that con-nectedness facilitates the dissemination of intelligencewithin an organization (Jb = .27, p < .01), therebyimproving the market orientation. Curiously, in Sam-ple I, connectedness does not appear to be related tointelligence dissemination, although it is related tooverall market orientation (b = .20, p < .01). Theseresults call for additional research to examine the link-age between connectedness and a market orientation.

Turning now to the role of organization-wide sys-tems, a market orientation appears to be very stronglyrelated to the orientation of the reward systems withinthe organization (b = .30, p < .001, Sample I; b =.31, p < .001, Sample II). Organizations that rewardemployees on the basis of factors such as customersatisfaction, building customer relationships, and soon tend to be more market-oriented.

Comparisons of the standardized regression coef-ficients in both Sample I and Sample II suggest thatthe design of reward systems has the strongest impacton market orientation from among the set included inthe study. The "right" reward systems appear to fa-cilitate all three components of a market orientation—intelligence generation {b = .39, p < .001, SampleI, b = .38, p < .001, Sample II), intelligence dis-semination (b = .24, p < .001, Sample I, b = .20,p < .01, Sample II), and responsiveness (b = 16, p< .05, Sample 1; b = .19, p < .01, Sample II).

The results from both samples suggest that cen-tralization of decision-making serves as a barrier to amarket orientadon. However, the patterns of resultsfor this variable across the two samples is different.In sample I, centralization is inversely related to in-telligence dissemination (b = -.14, p < .05) and re-sponsiveness {b = - . 22 , p < .01), and in sample II,centralization is inversely related to intelligence gen-eration (b = - .34 , p < .01).

Contrary to prior hypotheses, formalization doesnot appear to be related to a market orientation. Thisresult parallels in part the results reported by Narverand Slater (1991), who suggest that programmatic ap-proaches to improving market orientation may not beeffective. Formalization refers to the existence of for-mal rules and regulations in an organization and theorganizadon's efforts to enforce those rules.

Emphasis on rules is typically argued to make anorganizadon less adaptive to external changes. Whilethe results suggest that formalization is unrelated to amarket orientation, an aitemative interpretation is thatmere emphasis on rules is less relevant than the pre-cise nature of the rules in an organization. In otherwords, it is possible that, if properly designed, rulesmay facilitate rather than hinder a market orientation.For example, an organization may use rules to man-date that the various departments meet every monthfor a "market assessment" meedng. Such a rule is likelyto enhance intelligence disseminadon. Similarly, otherrules may mandate fast response to customer com-plaints or other market developments, thereby im-proving a market orientadon. Similarly, the lack of arelationship between departmentalization and a mar-ket orientation suggests that the sheer number of de-partments is less important than the connectedness andlevel of confiict among departments.

What are the hypothesized effects of a market ori-entation on business performance and employees? Asshown in Tables 3 and 4, a market orientation appearsto be significandy related to business performance whenoverall performance is assessed using judgmentalmeasures (b = .23, p < .01, Sample I; b = .36, p <.001, Sample II). By contrast, a market orientationdoes not appear to be related to performance using themore objective measure of market share. These results

Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences / 63

would appear to provide somewhat mixed support forthe importance of a market orientation. However, sev-eral issues warrant mention in this context.

First, it is unclear whether market share is a par-ticularly appropriate indicator of performance. For ex-ample, it is possible that certain high-performingcompanies may deliberately pursue a "focus" strategyand be unconcerned about share positions (cf. Porter1980). The literature is replete with examples of low-share companies outperforming high-share companies(e.g.. Inland Steel vs. USX). In such instances, mar-ket share may be a less accurate indicator of perfor-mance compared to judgmental assessments that takeinto account the particular strategy of a company.

Second, it is possible that there is a lag in the ef-fect of market orientation on market share, i.e., amarket orientation leads to higher market share overa relatively long period of time. If so, such effectsmay not be captured in the cross-sectional design em-ployed in the study. Based on these considerations,the authors tend to place more confidence in the re-sults obtained using judgmental measures of perfor-mance. (The results also suggest that product qualityis not related to market share, a finding that divergesfrom the results of studies using the PIMS database.)

The results reported in Tables 3 and 4 provide strongsupport for the hypothesized effects of a market ori-entation on employees' organizational commitment (b= .44, p < .001, Sample I; ^ = .66, p < .001, Sam-ple II) and esprit de corps (b = .51, p < .001, SampleI; b = .58, p < .001, Sample II). It appears that amarket orientation nurtures a bonding between em-ployees and the organization, as well as promotes afeeling of belonging to one big organizational familydedicated to meeting and exceeding market needs andexpectations.

Finally, the tests of the hypothesized moderatingeffects of market turbulence, competitive intensity, andtechnological turbulence on the linkage between mar-ket orientation and perfomiance (H11-H13) are ex-amined. The differences in regression coefficients as-sociated with market orientation are not statisticallysignificant (/? < .05) across environments character-ized by high and low levels of the three moderatorvariables in both samples. These results do not sup-port the hypothesized moderating effects for any ofthe three moderator variables. In other words, thelinkage between a market orientation and performanceappears to be robust across contexts characterized byvarying levels of market turbulence, competitive in-tensity, and technological turbulence. (Alternatively,it is possible that the hypothesized moderating effectsdo exist but were not detected because of the poten-tially insufficient power of the statistical test as a re-sult of the relatively small sample size or because thereliabilities of the measures were not sufficiently high.)

ConclusionManageriai impiicationsThe purpose of the study was to empirically test sev-eral hypotheses advanced in the literature regardingantecedents and consequences of a market orientation.The findings of the study suggest that the market ori-entation of a business is an important determinant ofits performance, regardless of the market turbulence,competitive intensity, or the technological turbulenceof the environment in which it operates. As such, itappears that managers should strive to improve themarket orientation of their businesses in their effortsto attain higher business performance. It should be notedthat, although a relationship between market orien-tation and market share was not found in this study,this finding should be tempered by the considerationsdiscussed earlier in the paper.

The study suggests several factors as important de-terminants of a market orientation. Specifically, amarket orientation appears to be facilitated by theamount of emphasis top managers place on marketorientation through continual reminders to employeesthat it is critical for them to be sensitive and respon-sive to market developments. Importantly, a marketorientation appears to require a certain level of risk-taking on the part of senior managers and a willing-ness to accept occasional failures of new products andservices as being a normal part of business life. In theabsence of such a willingness to take calculated risks,employees in the lower levels of an organizational hi-erarchy are unlikely to want to respond to market de-velopments with new products, services, or programs.

While the role of top managers in engendering amarket orientation is important, it appears that the na-ture of interdepartmental dynamics also plays a veryimportant role in determining the level of market ori-entation of a business. Two factors that appear to af-fect a market orientation are interdepartmental con-nectedness and conflict. Interdepartmental conflictappears to reduce a market orientation, whereas con-nectedness appears to play a facilitative role. As such,it may be useful to promote interdepartmental con-nectedness through physical proximity of departmentsand through telematics (e.g., computer hookups, voicemail). While some level of interdepartmental conflictis inherent in the charters of the different departments,it appears useful to reduce the level of conflict by us-ing various means such as interdepartmental trainingprograms, cross-functional activities, and alignmentof departmental perfonnance objectives by focusingthem on markets (e.g., customer satisfaction).

The role of market-based reward systems and de-centralized decision-making in engendering a marketorientation appears to be strong, suggesting that re-ward systems should take into account the contribu-

64 / Journal of Marketing, July 1993

tions of individuals in sensing and responding to mar-ket needs. Additionally, the negative relationshipbetween centralization and market orientation sug-gests that it may be useful to "empower" employeesto make decisions at lower levels of organizations ratherthan concentrate decision-making in the upper eche-lons of an organization. Although formalization anddepartmentalization do not appear to affect a marketorientation, it would seem that the content of formalrules, rather than their mere presence, is a more im-portant determinant of market orientation. Similarly,the manner in which the various departments interactwith each other appears to be a more important de-terminant of market orientation than the sheer numberof departments in a business.

Research DirectionsThere appear to be several areas in need of furtherresearch. Perhaps the most important relates to an as-sessment of the impact of a market orientation onbusiness performance. Although the results of this studyprovide support for a relationship between market ori-entation and a judgmental measure of performance,the posited relationship between market orientation andmarket share was not supported. In this regard, it isimportant to note that business performance is a mul-tidimensional construct and may be characterized in anumber of ways, including effectiveness, efficiency,and adaptability (see Walker and Ruekert 1987). Fur-thermore, performance on one dimension may runcounter to performance on other dimensions. There-fore, it would be useful to explore the complexitiesof the relationship between market orientation and al-ternative dimensions of business performance in fu-ture studies. It would also be useful to assess the re-lationship between a market orientation and businessperformance over extended periods of time.

Second, it seems desirable to assess the role ofadditional factors in influencing the market orienta-tion of an organization. For example, do certain incharacteristics of employees (personality, attitudes) helpor hinder a market orientation? Similarly, some of thevariables included in the present study deserve furtherinvestigation. For example, while fonnalization washypothesized to affect a market orientation, it was foundto be unrelated to it or any of its components. Futureresearch is needed to assess the characteristics of rulesthat facilitate or hinder a market orientation.

Furthermore, it is possible to argue that certainvariables, such as interdepartmental conflict, modeledin the study as antecedents of a market orientationcan also be treated as consequences of market orien-tation. It would be useful to conduct studies to assessthe size and direction of the relationship betweeninterdepartmental conflict and market orientation.In a similar vein, it appears likely that the environ-mental variables modeled in this study as moderatorsact in tandem either to increase or decrease the im-portance of market orientation for business per-formance. The limited sample size in this studyprecludes an analysis of such joint moderating ef-fects. It would be useful to perform such analyses infuture studies to better understand the conditions un-der which market orientation is particularly importantfor business performance.

From a methodological standpoint, data in this studywere obtained from senior managers in each of theSBUs. It would be useful to obtain a broader sampleof managers and perhaps even nonmanagers in SBUsin future studies. This would minimize any potentialbias in the data resulting from the level of the infor-mants. Furthermore, it would be very interesting tocompare perceptions of employees at different levelsof an SBU and account for differences in perceptions,if any, concerning the SBU's market orientation.It also would be useful to try to measure marketorientation using unobtrusive measures, such ascontent analysis of internal company memos, annualreports, and so on and relate these to other measuresof market orientation, such as the one used in thisstudy.

Finally, this study employs a cross-sectional anal-ysis of a large number of businesses. While providingimportant insights into the determinants of a marketorientation, it does not shed much light on the changeprocesses involved in improving a market orientation.For example, a relatively low level of market orien-tation may in fact lead managers to alter certainantecedents such as reward systems which, in turn,lead to a higher level of market orientation. In thisregard, it would be useful to conduct in-depth studiesof a few organizations engaged in the change processso as to better understand the factors that influencethe initiation and implementation of change effortsdirected at improving the market orientation of abusiness.

Scale

Appendix

Scale ItemsCoefficient

AlphaMarket Orientation

(IntelligenceGeneration)

In this business unit, we meet with customers at least once ayear to find out what products or services they will need in thefuture.Individuals from our manufacturing department interact di-rectly with customers to learn how to serve them better.

.71

Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences / 65

Market Orientation(IntelligenceDissemination)

Market Orientation(Response Design)

Market Orientation(ResponseImplementation)

Top ManagementEmphasis

3. In this business unit, we do a lot of in-house market research4. We are slow to detect changes in our customers' product pref-

erences.5. We poll end users at least once a year to assess the quality of

our products and services.6. We often talk with or survey those who can influence our end

users' purchases (e.g., retailers, distributors).7. We collect industry information through informal means (e.g.,

lunch with industry friends, talks with trade partners).8. In our business unit, intelligence on our competitors is gen-

erated independently by several departments.9. We are slow to detect fundamental shifts in our industry (e.g.,

competition, technology, regulation).10. We periodically review the likely effect of changes in our busi-

ness environment (e.g., regulation) on customers.

1. A lot of informal "hall talk" in this business unit concerns ourcompetitors' tactics or strategies.*

2. We have interdepartmental meetings at least once a quarter todiscuss market trends and developments.

3. Marketing personnel in our business unit spend time discuss-ing customers' future needs with other functional departments.

4. Our business unit periodically circulates documents (e.g., re-ports, newsletters) that provide information on our customers.

5. When something important happens to a major customer ormarket, the whole business unit knows about it in a short pe-riod.

6. Data on customer satisfaction are disseminated at all levels inthis business unit on a regular basis.

7. There is minimal communication between marketing and man-ufacturing departments concerning market developments.

8. When one department finds out something important aboutcompetitors, it is slow to alert other departments.

1. It takes us forever to decide how to respond to our competi-tors' price changes.

2. Principles of market segmentation drive new product devel-opment efforts in this business unit.

3. For one reason or another we tend to ignore changes in ourcustomers' product or service needs.

4. We periodically review our product development efforts to en-sure that they are in line with what customers want.

5. Our business plans are driven more by technological advancesthan by market research.

6. Several departments get together periodically to plan a re-sponse to changes taking place in our business environment.

7. The product lines we sell depend more on internal politics thanreal market needs.

1. If a major competitor were to launch an intensive campaigntargeted at our customers, we would implement a responseimmediately.

2. The activities of the different departments in this business unitare well coordinated.

3. Customer complaints fall on deaf ears in this business unit.4. Even if we came up with a great marketing plan, we probably

would not be able to implement it in a timely fashion.5. We are quick to respond to significant changes in our com-

petitors' pricing structures.6. When we find out that customers are unhappy with the quality

of our service, we take corrective action immediately.7. When we find that customers would like us to modify a prod-

uct or service, the departments involved make concerted ef-forts to do so.

1. Top managers repeatedly tell employees that this business un-it's survival depends on its adapting to market trends.

.82

.78

.82

.66

66 / Journal of Marketing, July 1993

Top Management RiskAversion

InterdepartmentalConflict

InterdepartmentalConnectedness

Formalization

Centralization

2. Top managers often tell employees to be sensitive to the ac-tivities of our competitors.

3. Top managers keep telling people around here that they mustgear up now to meet customers' future needs.

4. According to top managers here, serving customers is the mostimportant thing our business unit does.

1. Top managers in this business unit believe that higher finan-cial risks are worth taking for higher rewards.

2. Top managers here accept occasional new product failures asbeing normal.*

3. Top managers in this business unit like to take big financialrisks.

4. Top managers here encourage the development of innovativemarketing strategies, knowing well that some will fail.

5. Top managers in this business unit like to "play it safe."6. Top managers around here like to implement plans only if they

are very certain that they will work.

1. Most departments in this business get along well with eachother.

2. When members of several departments get together, tensionsfrequently run high.

3. People in one department generally dislike interacting with thosefrom other departments.

4. Employees from different departments feel that the goals oftheir respective departments are in harmony with each other.

5. Protecting one's departmental turf is considered to be a wayof life in this business unit.

6. The objectives pursued by the marketing department are in-compatible with those of the manufacturing department.

7. There is little or no interdepartmental conflict in this businessunit.

1. In this business unit, it is easy to talk with virtually anyone youneed to, regardless of rank or position.

2. There is ample opportunity for informal "hall talk" among in-dividuals from different departments in this business unit.

3. In this business unit, employees from different departments feelcomfortable calling each other when the need arises.

4. Managers here discourage employees from discussing work-related matters with those who are not their immediate su-periors or subordinates.

5. People around here are quite accessible to those in other de-partments.

6. Communications from one department to another are ex-pected to be routed through "proper channels."*

7. Junior managers in my department can easily schedule meet-ings with junior managers in other departments.

1. I feel that I am my own boss in most matters.2. A person can make his own decisions without checking with

anybody else.3. How things are done around here is left up to the person doing

the work.4. People here are allowed to do almost as they please.5. Most people here make their own rules on the job.6. The employees are constantly being checked on for rule vio-

lations.7. People here feel as though they are constantly being watched

to see that they obey all the rules.

1. There can be little action taken here until a supervisor ap-proves a decision.

2. A person who wants to make his own decision would be quicklydiscouraged here.

.85

.87

.80

.76

.88

Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences / 67

Reward SystemOrientation

OrganizationalCommitment

Esprit de Corps

Overall Performance

Market Turbulence

Competitive Intensity

TechnologicalTurbulence

3. Even small matters have to be referred to someone higher upfor a final answer.

4. I have to ask my boss before I do almost anything.5. Any decision I make has to have my boss' approval.

1. No matter which department they are in, people in this busi-ness unit get recognized for being sensitive to competitivemoves.

2. Customer satisfaction assessments influence senior managers'pay in this business unit.

3. Formal rewards (i.e., pay raise, promotion) are forthcoming toanyone who consistently provides good market intelligence.

4. Salespeople's performance in this business unit is measuredby the strength of relationships they build with customers.

5. Salespeople's monetary compensation is almost entirely basedon their sales volume.*

6. We use customer polls for evaluating our salespeople.

1. Employees feel as though their future is intimately linked tothat of this organization.

2. Employees would be happy to make personal sacrifices if itwere important for the business unit's well-being.

3. The bonds between this organization and its employees areweak.

4. In general, employees are proud to work for this business unit.5. Employees often go above and beyond the call of duty to en-

sure this business unit's well being.6. Our people have little or no commitment to this business unit.7. It is clear that employees are fond of this business unit.

1. People in this business unit are genuinely concerned about theneeds and problems of each other.

2. A team spirit pervades all ranks in this business unit.3. Working for this business unit is like being a part of a big fam-

ily.4. People in this business unit feel emotionally attached to each

other.5. People in this organization feel like they are "in it together."6. This business unit lacks an "espirit de corps."7. People in this business unit view themselves as independent

individuals who have to tolerate others around them.

1. Overall performance of the business unit last year.2. Overall performance relative to major competitors last year.

1. In our kind of business, customers' product preferences changequite a bit over time.

2. Our customers tend to look for new product all the time.3. Sometimes our customers are very price-sensitive, but on other

occasions, price is relatively unimportant.*4. We are witnessing demand for our products and services from

customers who never bought them before.5. New customers tend to have product-related needs that are

different from those of our existing customers.6. We cater to many of the same customers that we used to in

the past.

1. Competition in our industry is cutthroat.2. There are many "promotion wars" in our industry.3. Anything that one competitor can offer, others can match readily.4. Price competition is a hallmark of our industry.5. One hears of a new competitive move almost every day.6. Our competitors are relatively weak.

1. The technology in our industry is changing rapidly.2. Technological changes provide big opportunities in our indus-

try.

.73

.89

.90

.83

.68

.81

.88

68 / Journal of Marketing, July 1993

3. It is very difficult to forecast where the technology in our in-dustry will be in the next 2 to 3 years.*

4. A large number of new product ideas have been made pos-sible through technological breakthroughs in our industry.

5. Technological developments in our industry are rather minor.*This item was eliminated, based on the scale refinement procedure described in the text.

REFERENCESAiken, Michael and Jerald Hage (1968), "Organizational In-

dependence and Intra-organizational Structure," AmericanSociotogical Review, 33, 912—30.

and (1966), "Organizational Alien-ation,507.

American Sociological Review, 31 (August), 497—

Anderson, Paul and Terry Chambers (1985), "A Reward/Measurement Model of Organizational Buying Behavior,"Journal of Marketing, 49 (Spring), 7-23.

Arnold, Hugh H. (1982), "Moderator Variables: A Clarifi-cation of Conceptual, Analytic, and Psychometric Issues,"Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 29(April), 143-74.

Barksdale, Hiram C. and^ill Darden (1971), "Marketers' At-titude Toward the Marketing Concept," Journal of Mar-keting, 35 (October), 29-36.

Bennett, Roger and Robert Cooper (1981), "Beyond the Mar-keting Concept," Business Horizons, 22 (June), 76-83.

Bitner, Mary Jo (1990), "Evaluating Service Encounters: TheEffects of Physical Surroundings and Employee Re-sponses," Journal of Marketing, 54 (April), 69-82.

Borch, Fred J. (1957), "The Marketing Philosophy as a Wayof Business Life," in The Marketing Concept: Its Meaningto Management, Elizabeth Marting and Albert Newgarden,eds. New York: American Management Association, 3—16.

Boulding William and Richard Staelin (1990), "Environment,Market Share, and Market Power," Management Science,36 (October), 1160-77.

Chow, Gregory C. (I960), "Tests of Equality Between Setsof Coefficients in Two Linear Regressions," Econometrika,28 (July), 591-605.

Churchill, Gilbert A., Jr. (1979), "A Paradigm for DevelopingBetter Measures of Marketing Constructs," Journal of Mar-keting Research, 16 (February), 64—73.

Cronbach, Lee J. and Associates (1981), Toward Reform inProgram Evaluation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Day, George S. (1990), Market Driven Strategy: Processes forCreating Value. New York: The Free Press.

Deshpande, Rohit, John U. Farley, and Frederick E. Webster,Jr. (1933), "Corporate Culture, Customer Orientation, andInnovativeness in Japanese Firms: A Quadrad Analysis,"Journal of Marketing, 57 (January), 23-37.

and Robin Wensley (1988), "Assessing Advantage:A Framework for Diagnosing Competitive Superiority,"Journal of Marketing, 52 (April), 1-20.

Deshpande, Rohit and Gerald Zaitman (1982), "Factors Af-fecting the Use of Market Research Information: A PathAnalysis," Journal of Marketing Research, 19 (February),14-31.

and Frederick E. Webster, Jr. (1989), "Organiza-tional Culture and Marketing: Defining the ResearchAgenda," Journal of Marketing, 53 (January), 3-15.

Felton, Arthur P. (1959), "Making the Marketing Concept

Work," Harvard Business Review, 37 (July-August), 55-65.

Gaski, John F. (1984), "The Theory of Power and Conflict inChannels of Distribution," Journal of Marketing, 48 (Sum-mer), 9-29.

Hage, Jerald and Michael Aiken (1970), Social Change inComplex Organizations. New York: Random House.

Hall, Richard H., J. Eugene Haas, and Norman J. Johnson(1967), "Organizational Size, Complexity, and Formali-zation," American Sociological Review, 32 (December),903-11.

Hambrick, Donald C. and Phyllis A. Mason (1984), "UpperEchelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Man-agers," Academy of Management Review, 9 (2), 193-206.

Hise, Richard T. (1965), "Have Manufacturing Firms Adoptedthe Marketing Concept?" Journal of Marketing, 29 (July),9-12.

Hopwood, Anthony (1974), Accounting and Human Behavior.London: Haymarket Publishing Limited.

Houston, Franklin S. (1986), "The Marketing Concept: WhatIt Is What It Is Not," Journal of Marketing, 50 (April),81-7.

Jacobson, Robert and David A. Aaker (1987), "The StrategicRole of Product Quality," Journal of Marketing, 51 (Oc-tober), 31-44.

Jaworski, Bernard J. (1988), "Toward a Theory of MarketingControl: Environmental Context, Control Types, and Con-sequences," Journal of Marketing, 52 (July), 23-39.

Kaldor, A. G. (1971), "Imbricative Marketing," Journal ofMarketing, 35 (April), 19-25.

Kohli, Ajay K. and Bernard J. Jaworski (1990), "Market Ori-entation: The Construct, Research Propositions, and Man-agerial Implications," Journal of Marketing, 54 (April), 1-18.

Lawler, Edward E. and John G. Rhode (1976), Informationand Control in Organizations. Pacific Palisades, CA:Goodyear Publishing Company.

Levitt, Theodore (1969), The Marketing Mode. New York:McGraw-Hill.

Linden, William J. (1987), "Marketing Marketing: The RyderSystem Story," paper presented at Marketing Science In-stitute mini-conference on Developing a Marketing Orien-tation, (April), Cambridge, MA.

Lundstrom, William J. (1976), "The Marketing Concept: TheUltimate in Bait and Switch," Marquette Business Review,20 (Fall), 214-30.

Lusch, Robert F., Jon G. Udell, and Gene R. Laczniak (1976),"The Practice of Business," Business Horizons, 19 (De-cember), 65-74.