Yuko Shiraishi

-

Upload

annely-juda-fine-art -

Category

Documents

-

view

227 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Yuko Shiraishi

Annely Juda Fine Art23 Dering Street (off New Bond Street)

London W1S [email protected]

Tel 020 7629 7578 Fax 020 7491 2139Monday - Friday 10 - 6 Saturday 11 - 5

Yuko Shiraishi

Signal

11 September - 26 October 2013

YUKO SHIRAISHI: NETHERWORLD

The discovery of the tomb of Tuthankhamun, with its remarkably intact contents, generatedgreat popular interest, and still does. The contrast between the New Kingdom boy-king,whose small mummified body lies mutely at the centre of it all, and the enormous detail thatthe contents of the tomb offered up for interpretation, is one of the great tales of archaeology.Yuko Shiraishi uses the dimensions and the structure of this tomb for her newest installation,Netherworld, for non-archaeological reasons. Her principal point of departure was not theromantic tale of the excavation but the British Museum's 2010 exhibition of the Book of theDead, the collections of spells and charms that codify the changing patterns of ancientEgyptian thinking over many thousands of years. She read deeply into the Egyptians' religiousbelief and cosmology, and started to link their ideas about death and life, mortality and vitality,to her existing absorption in many aspects of science.

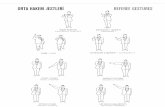

This focus on science and philosophy has coincided with her experimentation with paintings characterised by points in a unified field rather than by the horizontal lines that hadpreviously preoccupied her, and which had proved capable of sustaining such rich variation.Over recent years a new stage, and a new sense of space, have opened up, and she hasmade a wider range of drawings and studies than before. These drawings have taken on anew significance in Shiraishi's development of her work, and show a spirit of restless formalexploration. Many such drawings are part of her research for Netherworld; they also illuminatethe changes in the ambitions of the paintings. In particular they exemplify drawing as a modeof thinking and of modelling forms of thought – a two-way process. Drawings that attempt tostructure models of mythic and religious systems, the cycles of star formation, and theprocess of programmed cell death (apoptosis), in turn suggest forms that can be used forthinking that floats free of the functions of explanation. Many of these drawings are based onthe circle. The deep appeal of simple diagrammatic forms, especially when they do not fullyexplain ambiguous relationships between, say, two dimensions and three, or three dimensionsand four, is vividly exploited in these studies. They also display a striking contrast between thevery small scale and the very large, in that their titles include frankly metaphysical proposalssuch as World, Star and Body.

While investigating what has changed in this new stage of her work as a painter, it is alsoworth noting what has not changed. The format is still, in most cases, a vertically emphasisedrectangle. This slight adjustment of the absolute mathematical square to a taller format preserves a particular relationship with the vertical emphasis of the viewer as he or she standsbefore the painting. It provides a sense of reciprocal mirroring of a basic fact of standing that,allied to her confident and knowledgeable control of colour, gives all of her paintings a steadying and sustaining power.

Artists repeat themselves; it is a sign that an artistic proposal is being made. They alsochange. The pleasures of experiencing Shiraishi's work in this new stage are consistent withher earlier work, but the way those mental and physical pleasures are brought about suggeststhat the paintings depend on a new aspect of engagement. The move apparently describedby the words, 'a move from lines to points', is also, I think, a move to a new kind of potentialspace in the paintings; a space where interpretation – thinking, in simple terms, about what itis that we see – interacts with and interferes with the evidence of our senses, in a productiveway.

A relationship between points is not the same as a relationship between horizontal lines. Therelationship between points on a flat plane, when that flat plane can also be read spatially, isambiguous. The size and colour of the point will make it recede or advance, in a consistent orvariable way, against other points. This is something we experience again and again in lookingat Shiraishi's new paintings: implied relationships that do not settle into fixity. We look at thepoints, attempt to grasp how they connect, and often sense an implied figure, a central formthat could be the principle of organisation for what we see – but because some of the pointsare vestigial, and vanish when not stared at, the figure remains tantalisingly changeable andmotile. The sense of space in these new paintings differs from the horizontally organisedworks because it is frankly bigger. Although at first sight there is less in them, when we beginto perceive something, it is less abstract, and more like a centrally organised figure: not ahuman figure, perhaps something crystalline or molecular. Here is the largest painting in thegroup: a silvery grey ground animated by four points, two in pink, two in white, apparentlydefining the figure of a rectangle. It is untypical of the new paintings in its apparent simplicity,but the points are not in fact precisely aligned on the vertical axis. The painting is part of auniverse of movement, not of settled geometry. One smaller painting, Four, is legible andimmediately comprehensible as a slightly flattened square, made by four green points visiblethrough a layer of pink overpainting. But each of the four points that define this rectangle isghosted by a larger disc, a vestigial presence of red, just visible under the layer of pink. Soeven with a painting that is untypical of the group, and which offers an apparently simple rectilinear figure, a degree of uncertainty is created about what it is we see. The regularity ispulled and questioned by an only partially perceptible irregularity, with which it is twinned.These are figures, but they preserve a dynamic relationship with their ground, which is itself afield of variable texture, colour, transparency, opacity and energy. The relationship betweenfigure and ground is never simple.

There is a strong analogy for looking at these paintings in the experience of looking atstars. Diagrams of constellations flatten out interstellar space to isolate a legible, memorable,two-dimensional form; but when looking at the night sky itself the variable magnitude andcolour of the stars means we intuit, correctly or not, spatial relationships in depth, as well asthe familiar or half-remembered name for what we see. However, the paintings offer only ananalogy to looking at stars, they are in no way a representation of the night sky. The colour ofthe points or discs suggests an analogy with molecular models, and thus with visualisationand construction rather than with human vision. The colour relationships that remain the focusof Shiraishi's judgment and craft as a painter give us, at the same time, much for humanvision to work on, and this interacts and interferes with the ideational space of diagrams,models and three-dimensional figures. Jinsang Yoo writes: 'For Shiraishi, the possibility ofpainterly colours is not limited to the properties of pigment but can be enlarged into a reciprocal network that comprises all the matter that makes up the universe. Colour is notsimply paint but rather an optical mediator, and its allure is mirrored within the fundamentalinterconnectedness of the universe.'1

In describing the experience of these paintings I have used the word point, which suggestssomething geometrical, though many other words might be better – spots, which suggestsolar activity or visual interference in the eye; discs, which suggest two-dimensionality, thespace of the diagram; dots, which suggest indistinctness and irregularity and with that energy;or specks, which suggest dust and matter. Many of what I call points are drawn in one colour,then painted in another, which does suggest that they are discs; some are only drawn circles,

and are hardly there (dark matter, perhaps; or an equivalent of stars of the sixth magnitude,the faintest visible with the naked eye). Descriptive language fails cheerfully before this problem: there is not a right word for what I have called the 'points'.

The paintings using points and relationships are something new in Shiraishi's work. Thereare nevertheless important areas of continuity. Sometimes, within the puzzles these paintingsset for grasping, interpreting and holding onto a sense of 'figure', you become aware thatthere are possible connections between the points on the horizontal plane. You follow the lineacross. Does it match up? It is not always possible to say. One of the points becomes indistinct, or appears more strongly drawn into another relationship, another line of force. Theyears of work Shiraishi has put into exploring horizontality, as a deeply grounded aspect ofbeing, are not abandoned in these new paintings. The implicit structures are often based onprocedures of ruling and on horizontal lines, however vestigial the sense of this is for theviewer when looking at the final painting. These are paintings that suggest cosmic space, andare also grounded.

In Netherworld, four portals or doors are fitted tightly inside each other, each with angled indications of structure at the top that suggest an unfamiliar architecture. They seem to beexploded enlargements of a central rectilinear form: each is an outline, one side of somethinglarger. Only the innermost is clearly shown as part of a complete box-like shape. At the centreof it, resting on the gallery floor, is a diagrammatic suggestion of a recumbent human shape.So we are perhaps in some kind of tomb or sanctuary. The daylight from above is filtered intodim blue, and three lamps shine down, slowly changing their colour.

Ancient Egyptian tombs include what must be the first sculptures of false doors.Netherworld also seems to have false doors: the three outer portals exist as a set ofentrances tightly jammed each within the other, not as entrances you can actually enter. Thesense of an exploded, transparent form perhaps suggests a screen object that can be manipulated at will, but the physical encounter with this interlocked diagrammatic shape, andthe peculiar scale and detailing, suggest something else. Each portal is differently structured,not simply a smaller version of the one it is nested inside and connected to. There is no waythrough here, but the space around the form can be entered. We can carefully circumnavi-gate, approach the figure from all angles. We can stay here, not to pry and intrude, but toshare the space with whatever we think the resting form is, as the lamps adjust the light shining on it through a cycle of slow changes.

The structures that I have described as portals are made precisely from the measurementsof one side of each of the four gilded wooden shrines, each of which fitted inside each other.The largest of these was fitted in a tomb chamber that left only 60cm at each end and 30cmon either side, and almost entirely filled the available space. The installation allows us to getclose if we choose, but the human reaction to the idea of a tomb is strong. Tombs tend to becramped and small – rooms for one occupant only. Even when built as public displays ormausolea, with spaces for visitors to approach, you do not tend to stay long in them. Thewalk-in tomb of Noel Desenfans and Sir Francis Bourgeois, which is incorporated intoDulwich Picture Gallery, colours daylight into unexpected dim yellow. It is the light, as muchas the surprising presence of the sarcophagi, that creates such a strong atmosphere whenyou enter from the beautifully lit picture galleries. Shiraishi's installation, like Soane's permanent building, depends on a simple transformation of daylight for its primary effect, that

of entering another world – here it is a bluish, night-time world. It is a world like ours but perhaps suggesting different rules or possibilities. Colours that we tend, intuitively, to attributeto objects as a primary rather than a secondary property, are revealed as changeable. Youreyes take time to adjust to what you see, as the altered daylight interacts with the light of thethree lamps.

What you see is a figure that is lying down. This figure is modelled on the mummy ofTutankhamun, but generalised and abstracted into a figure of transformation. Shiraishi haslong had an interest in 'the physical acts of sitting and standing' as phenomenological givensof our relationship to space and to the world. To these interests her latest installation adds theact of lying down. A figure lying on its back is a customary way in which death is representedin western culture, and in particular in church monuments. The association of death withpeaceful sleep is a strong one, but the position in which the sculpted dead are usually placed,lying straight and horizontal, is not the way most people sleep, curled up on one side. Thedead are placed on their backs to remain alert and ready for the moment of resurrection. Theymay have their eyes open; more usually they are portrayed sleeping. In Egypt, through thousands of years in which short generations quickly succeeded each other, the dead wererepresented with their eyes wide open. The constant experience of change and of the shortness of human life was in sharp contrast with the infinitesimally small changes in art production. Wide open eyes seem to be a constant through the whole culture. On the shapedcoffin lids (often now displayed bolt upright), the scrolls, the shrines and sculptures in theBritish Museum's Egyptian galleries, I have not found an image of the dead with eyes closed.Death was considered as another stage of existence, in which the power of seeing was clearlyneeded.

The figure in Netherworld does not have a face we can see. Shiraishi has engaged deeplywith ancient Egyptian thought, not to reproduce it, but as part of a material and aestheticenquiry. The interest of what it means to lie down is first of all a physical and experiential one:the act of lying straight on your back is also part of life. When you lie on your back on grass,looking at the sky, the transfer of your weight to the earth is complete. It is a feeling of beingcompletely supported – and it is a very particular way of feeling fully alive. You become awareof your being on the planet as it turns, and of the wind moving the clouds directly above you.If you are trying this at night, you will find it is one of the best ways to look at stars. One of theliberating things about lying flat in this way is that you do not choose where to look. You justlook.2

The figure is balanced, securely and delicately, on its back. At the same time its structure –three concentric bands of steel in the horizontal plane, interlocked with three arranged vertically – implies physics more than it does biology. Directed to its centre − its heart − is thecycle of slowly changing light. The changes are derived from the conventional colours for representing the life cycle of a star. The celestial bodies that have been humankind's companions since before recorded history are thus incorporated into the figure's body and itsheart.3 Shiraishi's figure lies ambiguously in a state of suspended or somehow altered animation. This is not a flat representation of death as finite, and neither is it a representationof life. Shiraishi brings together ancient Egyptian thinking about life and death – the sun god'sjourney through darkness and the netherworld – with aspects of normative contemporary science. We are made from star-matter. The physical continuity of matter, from the raw materials of stars, to life (and consciousness, something that has evolved) and to whateverlies beyond life, is something Shiraishi regards as worthy of our strong interest – and our

wonder. She sees the broad coincidences between contemporary scientific descriptions ofthe cycle of matter and ancient intuitions about the cosmos (in forms of thought otherwiseregarded as obsolete), as raising profoundly interesting questions.

According to Barbara Lüscher, the writings we know as the Book of the Dead 'can best betranslated as "Spells for Coming Forth by Day", referring to the wish to emerge safely fromthe tomb in a spiritualised form.'4 However, this wish was clearly understood as only to begranted for a select few. As so often with systems whose aesthetic legacy continues to fascinate, the ancient Egyptian imperial structure was crushing and autocratic. For millennia itmaintained a hierarchical division of labour that was a tragic waste of human lives. There arefootstools from Tutankhamun's tomb that show this enthusiasm for domination with absoluteclarity. Each is decorated with foreign slaves, lying down in rows, head to head, to be troddenupon by the supreme king.5 These prostrate figures can perhaps be seen as a counter-version of the motif of the mummified figure lying down, whose ba ('spirit') could travel forthby day: figures who, in life, endured absolute domination.

Egypt sits at one end of the traditional story of art, through which its thinking about theuncertain relationship between death and life has remained visible. In Historical Grammar ofthe Visual Arts, Aloïs Riegl wrote: 'No obsolete worldview, once overcome, vanishes instantlyfrom the face of the earth. Although it might not persevere as a deep-rooted conviction, itcan, thanks to the pressure of tradition, continue to reverberate for centuries in outer forms.These forms play the most important role in the visual arts.'6 Ancient Egyptian art and thoughthave had a particularly long and curious afterlife, and remain potent in the imagery and imagination of our own culture.

Shiraishi's engagement with ancient Egyptian thought is part of the democratic culture ofthe contemporary museum, where mummies have for a long time been significant ways tolearn about death (as have pets). The galleries at the British Museum are always filled with thesound of children. This is not the kind of afterlife the Egyptians sought or can have expected,but we can be glad about it.

Yuko Shiraishi has synthesised from Egyptian art and thought (perhaps deliberately againstthe grain of actual Egyptian history) aspects of excited, speculative thinking about the cosmos, and linked these to a contemporary scientific worldview and an almost science-fiction future. Netherworld allows for uncertainties about our relationship to our world andtime to be felt. She has located in particular a mysterious sense of coexisting times, day-nightor night-day, times of generation and change, that reverberate with her continued journey as amaker of paintings.

Ian Hunt, September 2013

1. Jinsang Yoo, 'Yuko Shiraishi: Ramification of Colors', in Yuko Shiraishi: Space Space, Seoul: Kukje

Gallery, 2012, p.8

2. One of the few representations of this liberatory angle of view, straight upwards, is, paradoxically

enough, in Carl Dreyer's film Vampyr (1932). The hero has in some way been separated from his body,

which he leaves slumbering in a seated position near a graveyard. Taking flight from it as a spectral

form, he journeys to a workshop in which he discovers his own body now placed in a coffin with its

eyes open, dead or in a paralysed state. The camera then sees, from within the coffin, the glass plate

above his head screwed into place; and then we see through his eyes, straight upward: faces, including

that of the vampyr herself, an ancient white-haired woman. The coffin is then carried past buildings,

trees, open sky, all seen from the coffin. It's an unforgettable prospect of the space above our heads

and of life – as you have never before seen it, but through the eyes of one who fears being buried alive.

Fortunately the coffin is carried past the figure's own doubled body, still slumped as he left it, and his

spirit reunites with it in time to prevent his other body being buried. The theology of this – two bodies

apparently sharing only one soul – is at least as complex as ancient Egyptian thought about the ka and

the ba (see note 3). It is also a film that seems take place at a mysterious time that is neither day nor

night, but which could somehow be photographed.

3. 'Many societies, ancient and modern, have conceived of the person as comprising body and spirit (or

"soul"). The view of the ancient Egyptians was more complex. For them, the individual was a composite

of different aspects, which they called kheperu, or modes of existence. Prominent among these were

the physical body and its most important organ, the heart. The heart – rather than the brain – was

regarded as the functional centre of the person's being and also the site of the mind or intelligence. The

name and the shadow were also important, as each embodied the individual essence of the person.

Everyone also possessed spirit aspects called the ka and the ba. Both of these concepts are challeng-

ing to interpret. They have no precise equivalents in modern thought, and since their characters evolved

through time the Egyptians' own understanding of then changed. The ka is often associated with the

life-force. It was passed on from parent to child down the generations, but it was also personal to every

individual, a kind of 'double', which is often represented in art as an exact copy of the owner. After

death the ka remained at the tomb, where it was nourished by food offerings. The ba was the nearest

equivalent to the modern notion of the "soul". To a greater extent than the ka, the ba represented the

personality. It remained with its owner during life, but after death it acquired special importance. It had

the ability to move freely and independently of the body, and hence could leave the tomb by day.

Probably on account of this characteristic the ba was regularly depicted as a human-headed bird. This

form also emphasised the ba's ability to transform itself into different shapes, particularly various kinds

of birds. The freedom of movement of the ba is a constant theme of the Book of the Dead, many spells

asserting that the deceased would go forth from the tomb as a living ba. It was required, however, to be

return each night to be reunited with the mummy.' John H. Taylor (author and editor), 'Life and Afterlife

in the Ancient Egyptian Cosmos', Journey Through the Afterlife: Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead,

London: British Museum Press, 2010, p.17.

4. Ibid., p.288.

5. Marianne Eaton-Krauss, The Thrones, Chairs, Stools and Footstools from the Tomb of Tutankhamun;

incorporating the records made by Walter Segal, Oxford: Griffith Institute, 2008. The tomb included the

most complete set of ancient Egyptian furniture in existence. The measured drawings, photographs and

notes by the German architect Walter Segal date from his expedition to Egypt in 1935, and are also

available, along with much else of interest about the excavation, on the Griffith Institute's website

(www.griffith.ox.ac.uk). Walter Segal (1907-1985) relocated to London after making them, and he

became there the foremost exponent of self-build housing, giving his name to an easily learnt method

of building houses in wood. A career that could move between these diverse concerns is of unusual

interest. See John McKean, Learning from Segal/von Segal lernen, Basel and Boston: Birkhauser, 1989.

6. Aloïs Riegl, Historical Grammar of the Visual Arts [1897-88], tr. Jacqueline E. Jung, New York: Zone,

2004, p.56

Netherworld 2013

stainless steel tubing and LED lights

435 x 380 x 265 cm detail 4

Netherworld 2013

stainless steel tubing and LED lights

435 x 380 x 265 cm detail 4

3

Conceived of sky, born of dusk.

Sky conceived you and Orion,

Dusk gave birth to you and Orion.

Who lives lives by the gods' command,

You shall live!

You shall rise with Orion in the eastern sky,

You shall set with Orion in the western sky,

The Pyramid text of Pepi I Meryre (reign 2332 – 2283 BC)

Utterance 442: Sarcophagus Chamber, West Wall

My first encounter with death was when my family dog died.

I was five years old. I could see his pink skin below the white fur soaked with my tears. I could feel his

warmth as I pressed my face into his body.

The day after he died we dug a hole in the garden and buried him. Before burying him I wanted to give

him one last hug. He was so heavy that my uncle had to help me lift him up. His body was already stiff

and I could see his blackish pink tongue between his fangs. His body seemed somehow deflated. The

earth we piled over him was teeming with insects. As his body disappeared into the ground, I began to

wonder what would happen to him.

His absence and motionlessness seemed to expand and fill the whole house, overwhelming me with a

terrible sadness. When that night I asked my grandmother and uncle what would happen to him, they

took me out into the garden and told me that he would turn to earth and then become a star. They

pointed upwards to the night sky. Back then there was relatively little pollution in Tokyo and not that

many lights, so the sky was bright with stars. I vividly remember how I stared up wondering which of

the stars my dog had turned into.

Ever since then I have always had at the back of my mind the idea that death and stars are somehow

related.

Over the years death has impinged on my life in many different ways. My grandmother, who showed me

the stars that night, is no longer alive.

My childhood memories were stirred two years ago when I saw the Egyptian ‘Book of the Dead’

exhibition at the British Museum. This was when I started thinking about the Netherworld project.

The first civilisations to develop script were China and Egypt. The invention of writing both

revolutionised the course of history and also enslaved humanity to the desire to leave its mark for

posterity. In Egypt, the resulting obsession with immortality led to the cult of the mummy.

Tutankhamun’s Tomb 2013

ink on computer printout 21 x 29.7 cm

The hieroglyphics that are also such a key characteristic of Egyptian culture were used to decorate the

walls of tombs in the place of rich burial furnishings. The hieroglyphs themselves and the words and

sentences composed from them operated as a form of magic. The deceased were believed to be

protected from decay by the permanence of the hieroglyphic script and thus to be safe for ever.

My Netherworld is not, however, centred on script but on the structure of the tomb, which I have

modelled after that of Tutankhamun. The reason for choosing Tutankhamun’s tomb is because it has

survived more intact than any other. The tomb surrounded the deceased with many layers: four shrines,

one sarcophagus, three coffins and the famous gold mask on the mummy of the dead Pharaoh. These

layers were like a cocoon protecting the mummified body. They acted as physical barriers to prevent

intrusion by bandits at the same time as echoing in their multi-layered configuration the repetitiveness

of the spells written in hieroglyphics on the walls.

In Ancient Egypt, dusk marks the beginning of the journey to the afterlife, when the Ka and Ba that

leave a person’s body at the moment of death reunite, allowing the deceased to join the stars in the

sky. The Ka is the vital essence which comes into existence when a person is born. Because it was

believed that the Ka needed sustenance in the afterlife, the Egyptians made offerings of food and water

to the deceased. Ba was that which made a person individual and corresponds to our notion of

personality.

Mummification aimed to keep the body biologically unchanged in order that it could be reunified with

the soul in the next life. Extreme dryness and coldness also helped prevent decomposition of the body.

The process of programmed cell death, apoptosis, is a key feature of biological life. It underlies the

formation of fingers and toes, for example, and functions in such a way that the dying cells break down

into fragments that the body can remove without damage occurring to surrounding cells. In an adult

between 50 and 70 billion cells die each day. In a growing child the number is between 20 and 30

billion.

Apoptosis is not purely benign in its action, however, and has been implicated in a wide variety of

diseases. Too much apoptosis can lead to the body atrophying. We now know scientifically what the

Ancient Egyptians believed to be true, namely that life implies death and death implies life, that man is

born programmed to die.

This cycle of birth and death is also seen in the realm of the stars to which the Egyptians believed the

Pharaohs migrated after death. When the universe began there was only hydrogen. As the universe

moved into its first stage, this hydrogen fuelled the process by which nitrogen, carbon, silicon and iron

came into being.

These elements, which are the building blocks of human life, were all created within stars, which then

exploded and dispersed them in the second and third stages of the universe. The cyclicality of the life

of stars and that of humankind are linked in a way understood by the Egyptians with extraordinary

prescience. Birth is the beginning of death, and death is the beginning of life.

Yuko Shiraishi, August 2013

Signal, Installation at Annely Juda Fine Art, London

Anubis and Apoptosis (1) 2013

collage on paper 45.5 x 54.5 cm

Study - Nether World - 2 2013

collage on paper 45 x 38.8 cm

Orion and Apoptosis 2013

collage on paper 41.5 x 29.5 cm

World - 1-4 2013

pencil, crayon and collage on paper 20 x 15.4 cm each

Study - Nether World - 1 2013

collage on handmade paper 62 x 46 cm

Birth and Death Star 2013

collage on paper 45 x 32 cm

Signal, Installation at Annely Juda Fine Art, London

Signal, Installation at Annely Juda Fine Art, London

Signal between 1 and 2 2012

oil on canvas 183 x 168 cm

Overtone 2013

oil on canvas 137 x 121.4 cm

Here 2006-2013

oil on canvas 213 x 193 cm

Out There 2013

oil on canvas 152.4 x 137 cm

Begin Again 2013

oil on canvas 167.6 x 152.4 cm

Signal (3) 2013

oil on canvas 183 x 167 cm

Signal 2 2013

oil on canvas 212 x 182.5 cm

Recent Projects

Confession Show, Peep Box x Peep Show, Confession Box

Installation at The Russian Club Gallery, London

25 November 2010 - 15 January 2011

This project Confession Show, Peep Box x Peep Show, Confession Box is exploring

the architectural structure not only made to fit the human physical scale, but also to

create the psychological space filled with secrecy, guilt, sin and inhibition. Shiraishi is

fascinated by the way the act of confessing in the small confines of the box is

curiously similar to the peeping voyeurism of a sex show. In her work, the confession

panel works as a peeping window into the world within. She wants to explore human

fascination with the act of peeping and looking into the hidden and secret world in

darkness.

Missing Link

Place to Be

Installation at Galerie Gisèle Linder, Basel

15 June - 17 July 2010

The idea for this project came from reading Aldous Huxley’s Heaven and Hell and The

Human Situation. That people can be transported by the sight of shimmering objects

and go to extraordinary lengths to extract diamonds and precious metals from the

earth have nothing to do with beauty or usefulness. It is more to do with how their

reflective properties draw us into ‘a world of visions’, ‘the most remote of all our inner

worlds’, which lies deeper than the ‘world of memory, fantasy and imagination’ or

even that of the Jungian collective unconscious.

By creating a courtyard garden full of shimmering elements, Shiraishi wants people to

experience and reflect on what Huxley has so compellingly drawn our attention to.

She wants it to act as a Missing Link that takes us beyond the mundane and makes

us able to experience ‘consciously something of that which, unconsciously, is always

with us.’

Specimen

Specimen square record

April 2011

Specimen is an editioned work that takes the form of square vinyl records with five

original soundtracks encoded with insect sounds.

The soundtrack Specimen is composed by Yuko Shiraishi. The Passage of the

Butterfly is composed by Yuko Shiraishi and Tadao Kawamura, who have been

collaborating musically as band 36 since 2010, after the poem of the same title by

Edgar Allan Poe. White White Whale, which references Herman Melville’s Moby Dick,

is also jointly composed by Shiraishi and Kawamura. The third track, in two parts,

comprises Neuro-Specimen, composed by the musician John Matthias, and Ten Mile

Bank by Matthias and Andrew Prior.

Specimen

Installation at Shigeru Yokota Gallery, Tokyo 2011

Specimen

performance by Yuko Shiraishi and Tadao Kawamura and musicians

Women in Landscape – Women in many worlds

This work was a site specific installation and formed part of the exhibition Parallel

Remix, which was also curated by Yuko Shiraishi at the Leonard Hutton Galleries, New

York. For the exhibition Shiraishi selected artists who she knew to have an under-

standing of art history and that had the capacity and interest to look back on and

draw from the past. The exhibition included works by contemporary artists as well as

artists such as Malevich, Soutine and Chashnik.

Women in Landscape - Women in Many Worlds 2010

two-part vinyl installation and ink, acrylic and printed drawing

site-specific installation

Installation at Leonard Hutton Galleries, New York

14 October - 20 November 2010

Four 2013

oil on canvas 55 x 45cm

BIOGRAPHY

1956 Born in Tokyo

1974-76 Lived in Vancouver, Canada

1978-81 Chelsea School of Art, BA

1981-82 Chelsea School of Art, MA

Lives and works in London

SELECTED ONE PERSON EXHIBITIONS

1988 Edward Totah Gallery, London

1989 Shigeru Yokota Gallery, Tokyo

1990 Edward Totah Gallery, LondonArtsite, Bath

Galerie Konstruktiv Tendens, Stockholm

1991 Cairn Gallery, Nailsworth

1992 Edward Totah Gallery, London

Shigeru Yokota Gallery, Tokyo

1993 Gallery Kasahara, Osaka

1994 Galerie Konstruktiv Tendens, Stockholm

1996 Gallery Kasahara, Osaka

Galerie Hans Mayer, Düsseldorf

Focus, Experimental Art Foundation,Adelaide

1997 Juxtapositions, Annely Juda Fine Art, London

Shigeru Yokota Gallery, Tokyo

Galerie Konstruktiv Tendens, Stockholm

1998 Ernst Múzeum, Budapest (with Soós Tamás)

1999 Nancy Hoffman Gallery, New YorkAs Dark as Light, Tate Gallery St Ives, Cornwall

2000 Galerie Konstruktiv Tendens, Stockholm

2001 Shigeru Yokota Gallery, Tokyo

Assemble - Disperse, Annely Juda Fine Art, London

Gallery Kasahara, Osaka

2002 Infinite Line, Die unendliche Linie, Museum Wiesbaden, Germany

2002-03 Episode, Mead Gallery, Warwick Arts Centre, University of Warwick, Coventry; travelled to Leeds City Art Gallery

2003 There and Back, Crawford Municipal Art Gallery, CorkTuesday is Cerise, Waygood Gallery, Newcastle

2005 Temperature: Installation, Project and Painting, Annely Juda Fine Art, London

2006 A Way of Seeing, Leonard Hutton Galleries, New York (with Josef Albers)

Above and Below, Galerie König, Hanau (with Werner Haypeter)

Konstruktiv Tendens, Stockholm

8 x 2, Gesellschaft für Kunst und Gestaltung, Bonn and Galerie Friedrich Müller, Frankfurt (with Katsuhito Nishikawa)

2007 Contact, Galerie Dorothea van der Koelen, Mainz

2007-08 Even If Love, Kunstverein Ludwigshafen and Wilhelm- Hack-Museum (with Birgitta Weimer)

2008 Projects with Architecture 2001-2008, PEER, London

2009 Space Space: Installation, Project and Painting, Annely Juda Fine Art, London

2010 Place to be, Galerie Gisele Linder, Basel

The Russian Club Gallery, London (with Phil Coy)

2011 Specimen, Shigeru Yokota Gallery, TPH, Tokyo

2012 Space Space, Kukje Gallery, Seoul, Korea

2013 Signal, Annely Juda Fine Art, London

ONE PERSON PROJECTS

2001 FIH: Field Institute Hombroich (with Tadashi Kawamata, Katsuhito Nishikawa) Stiftung Insel Hombroich Museum, Neuss, Germany

2001-04 BBC White City Project (with Allies & Morrison), London

2005 Swimmingpool (with Mie Miyamoto, Jonathan Moore - Coldcut) Stiftung Insel Hombroich Museum, Neuss, Germany

2006 Moorfields Eye Hospital Children’s Centre, London

2008 Jiundou Hospital, Tokyo, Japan (with architect: Nissouken)

Canal Wall – a semi-permanent wallpainting commissioned by PEER in partnership with Shoreditch Trust at Regent’s Canal

Kyoto Art Walk (Curated by Yuko Shiraishi) Njojo Castle, Kiyomizudera Temple, Tofukuji Temple, Kyoto

2010 Parallel Remix, curated by Yuko Shiraishi, Leonard Hutton Gallery, New York

2011 Specimen, square vinyl record, TPH, Tokyo

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

1980 New Contemporaries, ICA, London

1988 The Presence of Painting: Aspects of British Abstraction 1957-88, Arts

Council Touring Exhibition: Mappin Gallery, Sheffield; Hatton Art Gallery, Newcastle; Ikon Gallery, Birmingham

1990 Künstlerinnen des 20. Jahrhunderts,Museum Wiesbaden, Germany

Galerie Konstruktiv Tendens, Stockholm

Whitechapel Open, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London

1991 Double Take, American-Japan Art

Association, New York

1992 Geteilte Bilder - Das Diptychon in

der neuen Kunst, Folkwang

Museum, Essen

A Sense of Purpose, Mappin

Gallery, Sheffield

1993 Moving into view - Recent

British Painting, Arts Council

Touring Exhibition, Royal Festival

Hall, London

Zwei Enerigien, Haus für

Konstruktive und Konkrete Kunst,

Zurich

Contemporary Art, Courtauld

Institute, London

1994 Unveiled, Cornerhouse Gallery,

Manchester

Jerwood Painting Prize 1994,

Royal Scottish Academy,

Edinburgh; Royal Academy of

Arts, London

1995 New Painting, Arts Council

Touring Exhibition

Pretext Heteronyms, Clink

Street, curated by Rear Window

1996 New Painting from the Arts

Council Collection, Bath

Museum, Bath

1997 Pretext Heteronyms, San Michele,

Rome

Haus Bill, Zumikon

1998 Clear and Saturated, Arti et

Amicitiae, Amsterdam

Immerzeit, Forum Konkrete Kunst

Galerie am Fischmarkt, Erfurt,

Germany

1999 Geometrie als Gestalt, Neue

Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Vendégjáték, Ludwig Múzeum,

Budapest

2000 Blue: Borrowed and New, The New Art Gallery, WalsallGrau ist nicht Grau, Galerie Gisèle Linder, Basel

2001 NU Konstuktiv Tendens-efter 20ar,Galerie Konstruktiv Tendens, Stockholm

2002 Colour - A Life of its own,Mücsarnok, Budapest

2003 Index on Colour, Leeds City Art Gallery, Leeds

2004 Art Scope Japan, Daimler Chrysler Contemporary, Berlin

Apriori, Galerie Dorothea van der Koelen, Mainz

2005 Swimmingpool (with Mie Miyamoto, Jonathan Moore - Coldcut) FIH, Stiftung Insel Hombroich Museum, Neuss

Föhn, Chelsea College of Art and Design, London

Kyoto Art Walk, Njojo Castle, Kyoto, Japan

2006 Intimate Space, MOT, LondonThe Best of Basle 2006, Galerie Hans Mayer, Düsseldorf

Busan Biennale, Korea

2007 Schwebend – Hovering, Galerie Dorothea van der Koelen, Mainz

Painting Painting, Modern Gallery – Vass László Collection, Veszprém, Hungary

Annely Juda - A Celebration, Annely Juda Fine Art, London

2009 Alles, Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen

Samlingsutställning, Galerie Konstruktiv Tendens, Stockholm

The Club Room, The Russian Club Gallery, London

2009/2010 Konkrete Idole - Nonfigurative Kunst und afrikanische Skulpturen, Museum Liner, Appenzell, Switzerland

When Ideas Become Form, Galerie Dorothea van der Koelen, Mainz

2010 Sameness & Difference, The Russian Club Gallery, London

Line and Colour in Drawing, Musées Royaux des Beaux Arts de Belgique, Brussels, Belgium

2011 Abstraction, The Room – Four Walls and a Floor, London

Artists for Kettles Yard, Kettles Yard, Cambridge

2012 10 x 10 Drawing the City London,Somerset House, London

2013 Matthew Tyson & Imprints, mpk Museum Pfalzgalerie Kaiserslautern

Russian Club presents ‘Wonderland’, Annely Juda Fine Art,London

SELECTED PUBLIC COLLECTIONS

Arts Council of Great Britain

British Council, London

British Government Art Collection, London

British Museum, London

Contemporary Art Society, London

Daimler Benz, Stuttgart, Germany

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, Austria

Graves City Art Gallery, Sheffield

Ludwig Muzeum, Budapest, Hungary

Max Bill - George Vantongerloo Foundation,Zumikon, Switzerland

McCrory Corporation, New York, USA

The National Museum of Art, Osaka, Japan

Ohara Museum, Kurashiki, Japan

Seibu Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan

Weishaupt Forum, Ulm, Germany

Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen,Germany

Kunsthalle Würth, Germany

ISBN 1-904621-52-X

Essay © Ian Hunt

Catalogue © Annely Juda Fine Art/Yuko Shiraishi 2013

Works © Yuko Shiraishi

Printed by Deckers Snoeck, Belgium

Special thanks to:

Andrew Everett and Gary Woodley for constructing Netheworld.

Yu Daigaku for the model and computer drawings.

Kyoko Ando for translating from Japanese to English.