why was the marlboro man so successful (legat de statutul social).pdf

Transcript of why was the marlboro man so successful (legat de statutul social).pdf

-

1 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

The Rise and Fall of an Icon: the Case of the Marlboro Man

by Murray Milner, Jr.

Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture

University of Virginia

Abstract

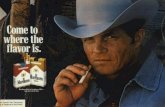

It is generally recognize that Marlboro cigarettes were transformed from a minor brand to

the bestselling cigarette in the world by an advertising campaign that featured the Marlboro Man,

a rancher/cowboy figure who was used in advertising campaigns from 1954 to 1999. The rise and fall

of this advertising icon is described and explained drawing on a general theory of status relations. It

is also argued that this approach is relevant to understanding the status of a wide array of cultural

objects, as well as the status dynamics of most groups.

Introduction

This paper explains the rise and fall of a key advertising icon, the Marlboro Man, by drawing

on a theory of status relations. On a theoretical level it suggests that explanation of the status and

mobility of cultural objects, including how things become art, high fashion, and collective memories,

could be made more parsimoniously by drawing on a general theory of status relations. This case

study is also illustrates how the theory is useful not only in understanding the status of categories of

cultural objects, but in explaining the status of a historically specific popular culture icon.

As used here an object can refer to either a symbolic object (e.g. a title or educational

degree), or a physical object (e.g., clothes or an automobile). The crucial feature is that an object is

not a subject or an actor capable of social action, but it is culturally created and defined.

-

2 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

Cultural Sociology and Stratification

Much of the literature on the link between cultural sociology and stratification has focused

on how cultural capital is acquired to maintained positions of social privilege or how peoples

position in the stratification system affects their consumption of culture (e.g., Bourdieu and Passeron

1977; Bourdieu 1984; DiMaggio 1982, 1987; DiMaggio and Mohr 1985; Lamont 1988; Lamont and

Lareau 1988; Halle1993; Bryson 1996; Bihagen and Katz-Gerro 2000). Possession of cultural objects

and knowledge about these objects are seen as one form of the more general notion of cultural

capital.

A different question, however, is how do cultural objects gain and lose status? As Dant

(2006) and Mc Donnell (2010) have pointed out the effectiveness and power of cultural objects is not

solely dependent upon their status; it is also affected by their actual material characteristics.

Nonetheless, a central issue is why some objects are valued and others are not. The research on the

status of cultural objects includes: why things are included in literary and religious canons (Corse

1997; Sheeley 1998) how things become art (Becker 2008; Peterson 2003), why certain music is

popular (Katz-Gerro, Sharon Raz and Yaish 2007; Bryson 1996); how film becomes an art form

(Baumann 2001), how the evaluation of genres of food have changed (Johnson and Baumann 2007),

how the role and status of capital cities change (Therborn 2006), and the role of critics and reviews

on determining the status of a variety of cultural objects (Blank 2007). Generally this literature

focuses on the changes in the status of categories and genre of cultural objects. There is, however,

the question of why the stature of a particular objects changes, which will be the primary focus of

this article.

Baumann (2006) has proposed a general theory of how cultural objects become legitimized

as art, drawing on the parallels between how things become art and the mobilization of social

-

3 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

movements. The more general issue, however, is how do cultural objects loose and gain status. The

question is not only why some things are art and some things are not, but why some art is in the

Metropolitan Museum of Art and some only in a local museum. Similarly, why are items that are

delicacies in some cultures considered inedible and even revolting in others; why are some second-

hand items valuable antiques or archeological artifacts and others trash; why are some clothes

fashionable and others so yesterday; why are some decorations thought to be elegant and some

kitsch? I cannot, of course, address all of these questions, but I want to propose a frame work that is

structured in such a way that it could be tested in an array of status systems, including those having

to do with the stratification of cultural objects. I will attempt to do this by drawing on a theory of

status relations that I have previously used to analyze Indian castes (1994a), religious worship and

doctrines (1993, 1994b), American teenagers (2004), celebrities (2005, 2010), and human rights

(2011).

Theory of Status Relations

Status is the accumulated approvals and disapprovals that people expressed toward an actor

or an object. As used here it is synonymous with prestige, honor and dishonor, esteemthough

each of these terms may have slightly different connotations.

The theory attempts to explain the key features of social relationships when status is a

central resource and is significantly insulated from, and hence not reducible to, economic and

political power. Status relationships include human relationships to cultural objects. Culture not

only structures humans relationships to objects, but it also includes the status relations between

objectsor more accurately the relative status that humans attribute to objects. To be more

concrete, people not only see the location and quality of their home as affecting their own status,

but they see the status of their home as part of a larger status system of family homes.

-

4 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

The main elements of such a theory can be stated in four points. The first two elements deal

with the nature of status as a resource.

Inalienability: Status is relatively inalienable. It is "located" primarily in other peoples'

minds. Hence, in contrast to wealth or political position it cannot be appropriated. Conquerors,

robbers, or parents can take away your property or remove you from a social role or office, but to

change your status they have to change the opinions of other people. This inalienability makes

status a desirable resource. Those with new wealth or political power nearly always attempt to

convert some of these resources into status to gain greater security and legitimacy. Once status

systems become institutionalized they are relatively stable. With respect to teen culture,

adolescents repeatedly report the difficulty of changing their status once it is established. Once one

is a convicted felon it is difficult to get a good job. The ranking of social categories is also relatively

stable; cheerleaders are not the core of the popular crowd one year only to be replaced by math

whizzes the next year.

Similarly, once a cultural object such as an icon gains high or low status it is difficultthough

not impossibleto change that status. Icons with a well-established positive status have a great

advantage over newer images. The exception is when status is bought or enforced by economic or

political power; the Soviet regime may have been able to bar jazz and rock from public performances

and insist that art take the form of socialism realism, but as soon as the political restraints were

removed the status of these cultural categories changed rather quickly. More generally, the more

insolated status and sacredness is from the mundane and profane, the more inalienable and stable it

is. Hence, advertising icons, which are usually intended to produce economic gain, tend to be less

stable than religious icons.

Inexpansibility: Status is relatively inexpansible. Some societies have a per capita income

that is a hundred times greater than other societies. In contrast, status is basically a relative ranking.

-

5 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

If ten thousand Academy Awards were given each year, they would be less prestigious.

Inexpansibility means that when someone (or something) moves up, someone moves down.

Consequently, where status is the central resource, mobility tends to be highly regulated and

restricted as in the Indian caste system, the Social Register and the National Academies of Science.

This is also the case for what pictures are hung in the Rijksmuseum and the Louvre, and what is sung

at La Scala and the Metropolitan. In major museums very few of their holding or sold off and only a

few new items are acquired each year. This is not to say that innovation and mobility never occur,

but only that they are highly regulated in well-established status systems. Conversely, If moving up is

restricted, putdowns are common. This is apparent in teenagers belittling peers, racist remarks,

negative campaigning, and cultural critique. The professional art or music critic who likes everything

is seldom taken seriously and is soon unemployed.

Inexpansibility is key source of iconoclasm: to promote one idea, belief, or imagery, it is

usually necessary to demote and even destroy alternatives. For example, a key way 17th century

Protestants succeeded in promoting the primacy of the Bible, the preaching of the Word, and the

believers direct personal relationship with God, was to demote the Saints, their images, and their

role as intercessors to God. Nor is it accidental that a key element of the Dada movement was not

only the denunciation of war, but the rejection of traditional definitions and standards of art. It is a

mistake see iconoclasm simply as fanaticism, though of course, it can take this form.

The next two elements of the theory focus on the sources of status.

Conformity: Conformity to the norms of the group is a key source of status. This is an

obvious point, but the consequences are somewhat less obvious: those with higher status tend to

elaborate and complicate the norms. Social groups, especially status groups, often elaborated the

norms that govern lifestyle and consumption. Complicated and subtle norms about dress, language

and demeanor make it harder for outsiders and upstarts to conform and hence become competitors.

-

6 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

Brahmans elaborate complicated rules about purity and pollution that it difficult for those in lower

castes to follow.

When it comes to cultural objects it is the gatekeepers who play this role. Examples include

curators at museums, editors at publishing houses, DJs at radio stations, conductors of orchestras,

and non-professional connoisseurs. The higher the status of the museum, publishing house, or

orchestra, the more elaborate the normative system and the more rigorously it tends to be enforced.

The most innovative music is seldom performed first by the top orchestras; avant garde art is not

usually seen first in the top museums.

Some kinds of nonconformity are, however, usually crucial to attaining high status. Popular

teenagers frequently flout the norms of adults and school officials; movie stars are often engage in

unconventional romantic relationships; innovative artist may reject commercial success or

contemporary standards (e.g. Isadora Duncan); the most innovative choreographers often form their

own dance schools or companies, (e.g., Martha Graham, and Alvin Ailey). It is usually only after such

deviant movements, and the cultural objects they have created, have developed a following that

they are admitted to more established cultural institutions.

Gatekeepers are not always effective, however, and where this is the case fashion often

becomes an alternative mechanism for maintaining a groups high status. It is difficult to produce a

painting that will pass for a Rembrandt. It is relatively easy, however, for clothing manufacturers to

copy the latest fashion designs or for teenagers to copy the latest slang of popular students. Hence,

instead of careful gate keeping resulting in a relatively stable status system of cultural objects, the

alternative strategy for maintaining high status is to constantly stay ahead by changing what is in.

This is seen in both fashion designs and teenage slang where many things quickly become so

yesterday.

-

7 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

Another form of elaboration occurs; this elaborates by embellishing and exaggerating an

actors level of conformityas contrasted to the elaboration and complication of the norms per se.

For example, groups tend to exaggerate the accomplishments of their heroes because heroes must

conform to extraordinary norms. Religious icons are typically of saintsthose who are considered to

have been exemplary, often undergoing torture and death to be true the norms of their faith.

Predictably their level of virtue, devotion, and heroismi.e. their conformity to the ideals of their

faithare often elaborated on after the fact. For example, St. George, the patron saint of England,

was a 3rd century Roman soldier who became a martyr because he refused to recant his Christian

faith. Six hundred years after his death stories of him killing a dragon to save a princess are

elaborated. Keep in mind that in the Western tradition dragons are often a symbol of generalized

malevolence and evil.

Elaborations also occur about the behavior of those who are viewed negatively exaggerating

their deviance, failings, and evil actions. This is seen in the negative stereotypes of various

minorities. It is also seen in the characteristics associated with evil spirits. They may not just do bad

things such as cause infertility, but they can be transformed into the epitome of evil, for example, the

Satan of Abrahamic religions. Such elaboration is not restricted to religious literature but occurs in

popular culture. Sherlock Holmess Professor Moriarty and the Batmans Joker are obvious

examples. Various icons can be associated with evil characters too, for example, the devils

pitchfork.

Similarly when it comes to the actual physical icons, the norms of what constitutes an

appropriate icon and how an icon is to be treated are elaborated. While there are religious icons

that are simple objects, most are elaborate depictions, often using gold leaf and vivid colors.

Moreover, they must be treated with reverence and treated as holy objects in and of themselves,

sometimes stored in containers or cabinets encrusted with jewels.

-

8 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

In sum, where conformity to the norms are a key source of status both the content of the

norms, and the conformity (or deviance) of exemplary individuals and categories are often

elaborated.

Associations: If you associate with people and things of higher status, it improves your

status, and if you associate with those of lower status, it decreases your status. This is especially so if

the relationship is expressive and intimate rather than instrumental and impersonal. Sex and eating

are the classic symbols of intimacy. Therefore teenagers are preoccupied with who goes with

whom, and who eats with whom in the lunchroombecause it has a crucial impact on their own

status. Similarly the key prohibitions in the Indian caste system regulate who marries whom and who

eats with whom. Brahmans can supervise those of lower castes when they are working, but not

marry them. Teenagers are more relaxed about associations in the classroom because this is an

instrumental setting; the cool kid can work with nerds on class project, but not party with them.

Similar processes operate in humans relationships with objects, though the forms of

intimacy usually take the form of touching, frequent use, ownership, etc. Your status is more

affected by the kind of personal car you drive and the food you serve at dinner parties than the

subway route you take to work and what you eat for lunch at your office desk; the first are

expressive and the second largely instrumental.

Like people, cultural objects tend to be sorted. You dont keep the garbage in the living

room. A high-status executive might take Penthouse and Hustler, but he is unlikely to put them on

his living room coffee table next to his copies of Foreign Affairs and Architectural Digest. The

socialite hostess is unlikely to serve cornbread with beef bourguignon.

In sum, where status is important, associations of people and objects are carefully regulated.

-

9 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

Icons and Iconic Figures

Now the notion of icon needs to be clarified. Classic Icons are religious works of art that point

to something sacred such as saints, deities, doctrines and core values. Typically they are small

paintings carried in worship processions in Eastern Orthodox churches. The icons are in some

respects sacred in their own right, but they also point to something that is even more sacred. They

are similar in this regard to relics, holy places, and sacraments. The term has come to be used more

generally to refer to a distinctive symbol which points to something else. The analysis of icons

usually involves two related status systems. The status of the iconic figure: the saint, the deity, the

hero, etc. and the status of the image and material object that represent this figure.

Iconic figures: iconic figures are usually associated with core values: faithfulness, loyalty,

bravery, extraordinary performances. Not only do they conform to the norms about such matters in

concrete ways, but they point to and affirm the importance and legitimacy of these more abstract

ideas. St. George is the patron saint of England and was widely admired and symbolized in many

Christian societies. His popularity was probably because he an accomplished soldier, a courageous

defender of his faith, and a pious Christian martyr. Martin Luther King and Gandhi were not only

moral prophets and shrewd politicians, but they came to be both the incarnation and the icons of

these virtues. Albert Schweitzer was a great musician, a world-class scholar, and an iconic

humanitarian who became a missionary doctor in Africa.

Iconic figures often have intimacy with the transcendent: through prayer, meditation,

retreat, and writing about such transcendent values. They also tend to regulate their intimacy with

the hoi polloi. Gurus, saints, and rock stars often spend significant amounts of time in retreat at

monasteries, ashrams, and gated mansions.

-

10 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

Followers value intimacy with the iconic figure such as eating with them, shaking their hand,

and going on pilgrimages to visit them.

Physical icons: Obviously the physical icons are associated with the iconic person. Examples

of these physical icons include religious icons & relics, objects that once belonged to an iconic figure,

for example, clothing of rock stars, baseballs hit by famous sluggers, letters written by iconic figures,

autographed pictures, and posters of the iconic figure. As with other kinds of status systems the

more intimate the object is with the iconic figure the more valuable and powerful it is, for example,

bodies or body parts, shrouds, crosses or swords that they wore, guitars that they used, etc.

For non-religious icons portrayed the mass media a different strategy is required with

respect to conformity. The quality of the media production must match existing standard, but there

are usually technological limits at any given time. Hence, there is not really an equivalent of coating

images with gold leaf when it comes to making TV commercials. The alternative strategy seems to be

to select people who are especially attractive or ideal-typical of the characters they are portraying.

Similarly the settings in which media icons are filmed are often spectacular: beautiful scenery, aerial

views, seemingly dangerous or exciting activities.

In short, iconic figures and the physical icons that represent them are usually part of a status

system. Many of the observed patterns of iconic actors, their devotees, and iconic objects can be

more systematically understood by viewing them through the lens of the theory of status relations.

A Case Study: the Marlboro Man

According the Advertising Age, which was started in the 1930s and is a key publication for

the industry, the ten most successful advertising images of the 20th century are:

1. The Marlboro Man - Marlboro cigarettes

2. Ronald McDonald - McDonald's restaurants

-

11 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

3. The Green Giant - Green Giant vegetables

4. Betty Crocker - Betty Crocker food products

5. The Energizer Bunny - Eveready Energizer batteries

6. The Pillsbury Doughboy - Assorted Pillsbury foods

7. Aunt Jemima - Aunt Jemima pancake mixes and syrup

8. The Michelin Man - Michelin tires

9. Tony the Tiger - Kellogg's Sugar Frosted Flakes

10. Elsie - Borden dairy products

Others might quibble about the precision of this ranking, but there seems no doubt that the

Marlboro Man was a top advertising icon of the last century. Why was this so? It was the icon for a

product that was increasingly being labeled as harmful by the medical profession. It used the image

of a cowboy just when the population was becoming overwhelmingly urban. It never used humor or

especially innovative images.

History of Marlboros and the Marlboro Man1

Marlboro cigarettes were initially an English brand dating back to 1824. The name came

from the location of the manufacturing plant that was on Greater Marlborough Street in London. It

was introduced into the U.S. in 1902. The U.S. brand was initially unsuccessful and was discontinued.

It was reintroduced in the 1920s as a filter cigarette aimed at women, using the advertising slogan

Mild as May. In the 1950s research associating smoking with lung cancer gained increasing

publicity and filter cigarettes become more popular. Philip Morris wanted to reposition the Marlboro

brand so that it would appeal to the much larger mens market. Leo Burnett, a Chicago advertising

executive, was charged with this task. He was arguably the most successful advertising man of all

1 Information about the history of Marlboros and the Marlboro Man was acquired from a number of different

websites. There seems to be little disagreement about the facts that make up the history of the brand and its icon.

-

12 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

time creating such brand images as the Jolly Green Giant, the Pillsbury Doughboy, Charlie the Tuna,

Morris the Cat, Tony the Tiger and the 7up "Spot."

He designed a campaign that associated Marlboros with a variety of masculine figures

including seas captains and an array of athletes. Burnett saw a 1949 Life magazine picture of C.H.

Long (19101978), a ranch foreman at the AJ Ranch in Claredon, Texas and decided the way to

expand the market was to associate Marlboros with the masculinity and folklore of the West. A

series of male models were used, but Darrell Winfield, a California rancher, served as the main model

for nearly twenty.

The image of the Marlboro man was nearly an immediate success increasing sales

dramatically. The image was used in the U.S. from 1954 until 1999, and is still used in a few

countries. It transformed Marlboros into the all-time best selling cigarette in the world. Why was

the campaign so successful?

Let us look at it through the lens of the theory of status relations. We will take up the

elements of the theory of status relations in a slightly different order:

Association:

The Marlboro Man associated product with a vast mythology about the western U.S. At the

end of the 19th century Frederick Jackson Turner had elaborated the thesis that American culture and

the American character had been fundamentally shaped by the frontier experience with its emphasis

on independence, freedom, and the leaving behind of old customs. Whatever the truth of the thesis,

it became a well established mythology. This theme was repeatedly articulated in popular culture. It

is found in numerous novels including those by Zane Grey, Cormac McCarthy, and Larry McMurtry.

Some of the most popular movies of the last half for the twentieth century were Westerns, including

Stage Coach, The Gun Fighter, Cowtown, The Kid from Texas, Mule Train, The Outriders, Rio Grande,

Fort Apache, Bad Day at Black Rock, Sierra, Wagon Master, Winchester 73, Across the Wide

-

13 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

Missouri, and Cattle Drive, True Grit, and the Last Picture Show. Western movies featured the major

movies stars of the time including John Wayne, James Stewart, Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, Spencer

Tracy, Clark Gable, Tony Curtis, Joel McCrea, Alan Ladd, Randolph Scott, Mickey Rooney, Rod

Cameron, and Tyrone Power. The major actresses of the time also appeared in Westerns: Susan

Hayward, Ava Gardener, Marilyn Monroe, Barbara Stanwyck, Shelly Winters, Maureen OHara,

Dorothy Malone, and Rhonda Fleming. Many of these films were created by some of the most

prominent directors of the time including Howard Hawks (who toward the end of his career received

an Honorary Academy Award as a master American filmmaker) and John Ford (who received four

Academy Awards as Best Director). Probably the best-known B movie stars of the time were

Gene Autry, Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, who appeared almost exclusively in Westerns. Similarly the

most popular TV programs of the time were Westerns: Gunsmoke, Bonanza, Wagon Train, and Have

Gun, Will Travel. These are only the best-known series. Wikipedia list 174 American TV series that

were westerns. The power and centrality of this mythology is shown in linguistic usage: the

common meaning attributed to the noun Western refers to a movie or a novel that portrays the

western U.S. in the 19th century.

The key point is that the Marlboro Mans status and success was in large part due to the fact

that it could be associated with an enormous bank of popular culture and mythologyand

substantial skill and money were spent to do this.

Conformity:

The Marlboro Man image conformed to and reinforced the norms of masculinity, autonomy,

freedom, independence, boldness, and implicit but not blatant sexinessindirectly countering the

increasing health concerns about smoking.

In one TV commercial a wild stallion is portrayed as stealing the ranchers best mares. The

stallion almost certainly symbolizes sexuality, masculinity, freedom and being untamed. A cowhand

-

14 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

is in hot pursuit of the stallion. The rancher is shown lighting up a Marlboro and thinking about what

is happening. Suddenly he whistles for the cowhand to stop the chase and he comments, supposedly

to himself, You dont see many wild stallions anymore . . . theyre the last of a rare and singular

breed. Then over a crescendo of music the announcers voice says, Come to where the flavor is.

Come to Marlboro Country. The commercial not only suggest that smoking is a way of affirming and

conforming to the norms of freedom and singularity, but that wildness (i.e., risky behavior) should be

respected. Another way of saying this is that the norms and values of individualism and freedom are

elaborated to define smoking as a way of conforming to these beliefsespecially by smoking

Marlboros. The TV commercial draws on elements of both conformity and association to raise the

status and attraction of its product.

Inalienability:

Compared to deities and saints advertising icons have relatively short lives. In part because

they are by their nature not insulated from economic and political interests. As advertising

campaigns and images go, however, fifty years of great success is a very long time. This relative

longevity was due in part to the icons association with the deeply established mythology of the

American West, and in part to the relative stability that occurs from simply having attained a high

level of status and the elaboration process discussed above. But clearly the Marlboro man has

ridden into the sunset and is no longer a significant Icon. How is this to be explained? Let us begin

by considering the significance of the inexpansibility of status.

Inexpansibility:

Two key things happened. First, medical research overwhelmingly demonstrated that

smoking contributed to a whole array of fatal diseases. It is hard to convince even the most fantasy-

imbued would-be cowboy that dying of lung cancer is the best way to express their masculinity and

commitment to freedom. This enormously reduced the status and coolness associated with smoking.

-

15 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

This, of course, affected all cigarette brands and total cigarette sales begin to decline in the U.S.

(though not in the world). Increasingly laws restricted both the advertising of cigarettes and more

generally their marketing. Stated in another way, the status of the status system of which Marlboros

were a part, steadily declined. Hence, there was less status to distribute among brands. While

Marlboro may have still had the highest relative status among cigarette brands, the total cultural

status that this brought the brand was much less.

Second, the cultural revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s demoted the mythology of the West

in general and macho culture in particular. There had been a long history of women resisting

patriarchy and male dominance, but a new wave of feminism emerged in the 1960s and 1970s that

not only called into question womens second class status, but questioned the legitimacy of

supposedly universalistic notions that were in fact largely male perspectives. A number of books

took up these themes (see Ryan 1996). Two especially influential books were Betty Friedans The

Feminine Mystique (1963) and Carol Gilligans In a Different Voice (1982). The first attacked the

notion that a womans identity and status should be largely derived from that of their husbands (via

association). The second both rejected many conventional perspectives because they were created

primarily out of the experience of men, and also argued for the legitimacy of viewpoints that were

especially characteristic of women.

The protests of Native Americans and revisionist histories redefined the settling of the West

as conquest rather than a heroic adventure story. In addition to scholarly studies (e.g., Jennings

1975, Steele 1994), Dee Browns Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (1970), a best-seller and TV film,

did much to demote the romanticism associated with Indian wars. The environmental movement

pointed out that the Western settlement often produced overgrazing, the extinction of species, as

well as other forms of environmental degradation.

-

16 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

In short, the glories of the West and the coolness of smoking were critiqued and put down

and the decline of the Marlboro Man followed.

Conclusion

The story of the Marlboro man and of icons in general can certainly be told without invoking

the particular theory I have used. I would argue that the theory adds two things. First, it gives

guidance about how to analyze this particular concrete case by providing a check list of processes

that important in most status systems. Second, it shows that systems of icons and the history of

particular icons are cases of a much more general phenomenon, that is, the emergence and

operation of status systems. Hence, it suggest a way of analyzing not only an array of icons, but the

status structure of virtually any kind of cultural object. For example, collective memories, and history

itself, refer to those events and experiences that have been given high enough status that they

should be recorded and recalledand like any other status system what counts as history will be

shaped by conformity, association, inalienability, and inalienability. In large part, what is meant by

revisionist history is that the criteria for what is considered important are shifted, i.e., the status

system that is the core of historiography is changed. To give another example, the waiting list for

who is to receive an organ transplant is a status stratification system that operates very much like the

status system of art museums in which gate keepers play a key role.2 This is not, of course to argue

that there will not be features that are relatively unique to any given category of cultural objects.

Nor is it to suggest that this kind of analysis explains everything or that other theoretical approaches

should be discarded. Rather it sets the stage for efforts to more fully integrate our understanding of

the stratification of individual, groups, and cultural objects.

2 I am aware that this argument in many ways parallels Bourdeaus (1984) discussion of fields. To elaborate

the similarities and differences is beyond the scope of this paper.

-

17 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

Bibliography

Baumann, Shyon. 2007. A general theory of artistic legitimation: How art worlds are like social

movements, Poetics, 35: 4765.

Becker, Howard S. 2008 [1982]. Art Worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bihagen, Erik and Tally Katz-Gerro. 2000. Culture consumption in Sweden: The stability of gender

differences, Poetics 27: 327-349.

Blank, Grant. 2007. Critics, Ratings, and Society. Lanham MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Bryson, Bethany. 1996. "Anything But Heavy Metal": Symbolic Exclusion and Musical Dislikes

American Sociological Review, 6: 5 (Oct.): 884-899.

Bourdieu, Pierre and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1977. Reproduction in education, society and culture.

London; Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of Judgment and Taste. Cambridge: Harvard

University Press.

Corse, S. M. 1997. Nationalism and literature: the politics of culture in Canada and the United States.

Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press.

Dant , Tim. 2006. Material civilization: things and society, British Journal of Sociology, 57: 2.

Godard, Barbara. 2002. "Feminist Periodicals and the Production of Cultural Value: The Canadian

Context," Women's Studies International Forum, 25: 2: 209-223.

DiMaggio, P. (1982). Cultural capital and school success: The impact of status culture participation on

the grades of U.S. high school students. American Sociological Review, 47(2), 189-201.

DiMaggio, P., and Mohr, J. (1985). Cultural capital, educational attainment, and marital selection.

American Journal of Sociology, 90(6), 1231-1261.

-

18 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

Halle, D. (1993). Inside culture: art and class in the American home. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

Jennings, Francis. 1975. The Invasion of America: Indians, colonialism, and the cant of conquest.

New York: Norton.

Johnston, Jose and Shyon Baumann. 2007. Democracy versus Distinction: A Study of

Omnivorousness in Gourmet Food Writing, American Journal of Sociology, 113: 1: (July):

165-204.

Katz-Gerro, Tally, Sharon Raz and Meir Yaish. 2007. Class, status, and the intergenerational

transmission of musical tastes in Israel," Poetics 35: 152167.

Lamont, M., and Lareau, A. (1988). Cultural capital: Allusions, gaps and glissandos in recent

theoretical developments. Sociological Theory, 6: 2: 153-168.

Lareau, A. (1997). Human capital or cultural capital? Ethnicity and poverty groups in an urban school

district. American Journal of Sociology, 103: 3: 816-817.

McDonnell, Terence E. 2010. Cultural Objects as Objects: Materiality, Urban Space, and the

Interpretation of AIDS Campaigns in Accra, Ghana, American Journal of Sociology, 115: 6

(May): 1800-1852.

Milner, Murray Jr. 1993. "Hindu Eschatology and the Indian Cast System: An Example of Structural

Reversal," The Journal of Asian Studies, 52 (May):298-319.

____________. 1994a. Status and Sacredness: A General Theory of Status Relations and an Analysis

of Indian Culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

_____________. 2004. Freaks, Geeks, and Cool Kids: American Teenagers, Schools, and the Culture

of Consumption. New York: Routledge.

_____________. 2005. Celebrity Culture as a Status System, The Hedgehog Review, Spring, 66-76.

_____________. 2010. Is Celebrity a New Kind of Status System? Society, 47: 379387;

-

19 Milner on the Marlboro Man, to be presented at ASA meeting, August 2011.

_____________. in press [2011]. Human Rights as Status Relations: A Sociological Approach to

Understanding Human Rights, in Handbook of Human Rights, edited by Thomas Cushman.

New York: Routledge.

Paul DiMaggio. 1987. "Classification of Art," American Sociological Review, 52: (August): 440-455.

Peterson, Karin Elizabeth. 2003. Discourse and Display: The Modern Eye, Entrepreneurship, and

the Cultural Transformation of the Patchwork Quilt, Sociological Perspectives, 46: 4,

(Winter): 461-490.

Ryan, Barbara, 1996. The women's movement: references and resources. New York: G.K. Hall.

Sheeley, Steven M. 1998. "Scripture" to "Canon" Review and Expositor, 95: 513-522.

Shyon Baumann, 2001. Intellectualization and Art World Development: Film in the United States,

American Sociological Review, 66: 3 (Jun.): 404-426.

Therborn, Gran. 2006. Eastern Drama: Capitals of Eastern Europe, 1830S-2006, International

Review of Sociology, 16:2, 209-242.

Witkin, Robert W. 1997. Constructing a Sociology for an Icon of Aesthetic Modernity: Olympia

Revisited, Sociological Theory, 15: 2 (Jul.): 101-125.