docshare02.docshare.tipsCurrent View of Risk Factors for Periodontal Diseases*1041 Current View of...

Transcript of docshare02.docshare.tipsCurrent View of Risk Factors for Periodontal Diseases*1041 Current View of...

1041

Current View of Risk Factors forPeriodontal Diseases*Robert J. Gerico

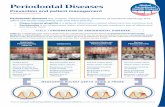

Periodontal diseases are infections, and many forms of the disease are associatedwith specific pathogenic bacteria which colonize the subgingival area. At least two ofthese microorganisms, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Actinobacillus actinomycetem-comitans, also invade the periodontal tissue and are virulent organisms. Initiation andprogression of periodontal infections are clearly modified by local and systemic con-

ditions called risk factors. The local factors include pre-existing disease as evidencedby deep probing depths and plaque retention areas associated with defective restorations.Systemic risk factors recently have been identified by large epidemiologie studies usingmultifactorial statistical analyses to correct for confounding or associated co-risk factors.Risk factors which we know today as important include diabetes mellitus, especially inindividuals in whom metabolic control is poor, and cigarette smoking. These two riskfactors markedly affect the initiation and progression of Periodontitis, and attempts to

manage these factors are now an important component of prevention and treatment ofadult Periodontitis. Systemic conditions associated with reduced neutrophil numbers or

function are also important risk factors in children, juveniles, and young adults. Diseasesin which neutrophil dysfunction occurs include the lazy leukocyte syndrome associatedwith localized juvenile Periodontitis, cyclic neutropenia, and congenital neutropenia.Recent studies also point to several potentially important periodontal risk indicators.These include stress and coping behaviors, and osteopenia associated with estrogendeficiency. There are also background determinants associated with periodontal diseaseincluding gender (with males having more disease), age (with more disease seen in theelderly), and hereditary factors. The study of risk in periodontal disease is a rapidlyemerging field and much is yet to be learned. However, there are at least two significantrisk factors-smoking and diabetes-which demand attention in current management ofperiodontal disease. J Periodontol 1996;67:1041-1049.

Key Words: Periodontal diseases/microbiology; Periodontitis microbiology; risk fac-tors/diabetes, smoking, osteopenia, stress; Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans;Bacteroides forsythus; Fusobacterium nucleatum; Porphyromonas gingivalis; Prevo-tella intermedia; Wolinella recta.

Changes in our knowledge of the etiology of periodontaldisease, and the recognition of the potential importanceof susceptibility factors as they affect initiation and pro-gression of periodontal disease, have led to intense studyof specific risk factors for periodontal diseases. It was

previously believed that the population was universallysusceptible to periodontal disease. Epidemiologie studies,such as the survey conducted by the National Center forHealth Statistics and those of the National Institute ofDental Research, along with additional studies from

*Departments of Oral Biology, Periodontology, and Microbiology andPeriodontal Disease Research Center, School of Dental Medicine andSchool of Medicine and Biomedicai Sciences, State University of NewYork, Buffalo, NY.

abroad, have changed the view of universal susceptibility,since they report that 5% to 20% of the population sufferfrom severe forms of destructive Periodontitis.1-3 While a

significant proportion of the population is susceptible to

Periodontitis, it appears that there is a larger segment ofthe population that is not susceptible to the severe formsof Periodontitis. This observation leads to the proposalthat there are susceptibility factors or risk factors thatmodulate susceptibility or resistance to destructive Per-iodontitis.

Concepts concerning the etiology of periodontal dis-ease have also changed markedly in the last three decades.Several specific bacteria, including Porphyromonas gin-givalis, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Prevotel-

1042 RISK FACTORS FOR PERIODONTAL DISEASESJ Periodontol

October 1996 (Supplement)

Table 1. Hierarchy of Evidence for Risk Factors*

Study DesignHypothesis Hypothesis Interpretation andGenerating Testing Health Policy Implication

1. AnecdoteCase reportCase series

2. Case-control3. Cross-sectional4. Longitudinal (cohort)5. Intervention

a) RCT of treatment effectsin high- vs. low-risk groups

b) RCT in which risk factoris modified

XX

XXX

X

X

Suggests a relationship

Evidence for risk indicatorEvidence for risk indicatorEvidence for risk factor

Evidence for risk factor modulation

Strongest evidence for specific in-teraction to apply to population

*Based on Ibrahim.8 RCT = randomized controlled trial.

la intermedia, Bacteroides forsythus, and perhaps otherssuch as Wolinella recta, Fusobacterium nucleatum, andspirochetes, are associated with severe forms of peri-odontal disease.4 In addition, a group of pathogens not

normally found in the oral cavity has been associated withperiodontal disease, including Enterobacteracea, Pseu-domonadacea, and Acinetobacter.5 Periodontal disease islikely an infection, with severe forms of the disease as-

sociated with specific bacteria that have colonized thesubgingival area in spite of the host's protective mecha-nisms. Furthermore, some of the pathology appears to re-sult from host-mediated responses triggered by bacterialinfection. However, the susceptibility of individuals ap-pears to vary greatly depending upon which risk factorsare operative. Risk factors can be thought to affect notonly both protective and destructive host responses, butalso the pathogenic flora.

In this paper, risk factors for periodontal disease willbe assessed with emphasis on risk factors for adult Per-iodontitis. Recent studies have generated interest in theassociation between periodontal infections and other sys-temic conditions and diseases, including oral infectionsthat act as foci for disease or injury at other sites includ-ing the lungs, and periodontal disease as it may affectdiabetic control, adverse pregnancy outcomes, heart dis-ease, and stroke. These will be addressed in detail byother papers in this supplement.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN THEASSESSMENT OF RISK FACTORS FORPERIODONTAL DISEASES

DefinitionsA risk factor for periodontal disease is a characteristic,aspect of behavior, or an environmental exposure whichis associated with destructive Periodontitis. The associa-tion may or may not be causal.6 Some risk factors are

modifiable, while others cannot be modified or cannoteasily be modified. Those factors that cannot be modifiedare' often called "determinants," or background factors.

"Risk factor" often implies a modifiable condition. Theterm "risk indicator" is used to describe a possible factorassociated with a disease, which is identified from case-control or cross-sectional studies. True risk factors are

those associations with disease that are confirmed in lon-gitudinal studies.7 The term "risk marker" usually refersto a risk factor which is predictive, i.e., associated withan increased probability of disease in the future.

Study DesignThere are several study designs that are useful in the as-

sessment of risk factors for diseases including Periodon-titis, and which can be considered to constitute evidenceof increasing strength (Table 1). Studies which are weak-est, but provide the basis for generating hypotheses, in-clude anecdotes, case histories, and case series reports.The next strongest line of evidence concerning the asso-ciation between a potential risk factor or risk indicatorand disease is provided by case-control studies. Case-con-trol studies can often identify risk indicators, but are notoften able to assess the role of important confoundingfactors. Cross-sectional population-based studies are oftenmore powerful than case-control studies because they de-scribe large populations and allow a more rigorous as-

sessment of confounders or co-risk factors by multivariatestatistical analysis. Cross-sectional studies then are im-portant since they can lead to identification of risk indi-cators which are reasonable or plausible correlates of dis-ease.

Longitudinal studies are generally useful in providingstrong evidence that a risk indicator or putative risk factoris indeed a true risk factor. Risk indicators may be, butare not always, confirmed as risk factors in longitudinalstudies. Longitudinal periodontal studies, although theyprovide strong evidence, are often difficult since adultPeriodontitis is most often a slowly progressing disease,and the definition of a new case is by no means clear.Longitudinal studies are often necessary, however, to re-

solve important questions regarding which risk indicatorsidentified in cross-sectional, case-control, or case history

Volume 67Number 10 GENCO 1043

studies are indeed associated as true risk factors. Fur-thermore, longitudinal studies offer the possibility for es-

tablishing the temporal sequence of the risk factor as itrelates to onset or progression of the disease.

Analysis of risk is ultimately directed to improving thehealth of the population, and the final evidence for theefficacy of elimination or suppression of a risk factor inmodulating or reducing the disease or condition is foundfrom intervention studies. The strongest experimental de-sign for an intervention study is the randomized con-trolled trial in which modification of the risk factor israndomly assigned to a test group as compared to a con-

trol group which receives an appropriate placebo inter-vention. Identification of the mechanism of action of riskfactors allows one to understand the mode of action ofthe risk factor and possibly to design effective risk inter-vention studies which address the mechanism of action.8

In a typical early, randomly controlled trial, the effectsof treatment are compared in a high-risk and a low-riskgroup to determine if outcomes differ. If they do, thenother placebo-controlled randomized trials are carried outin which the risk factor is modified, and the effects on

disease initiation, progression, or response to treatmentare measured. These intervention trials provide strong ev-

idence that the risk factor is clinically important in thedisease, and hence should be eliminated or reduced inprevention or treatment of the disease.

Measurement of PeriodontitisPeriodontitis is defined as the loss of both the attachmentof the periodontal ligament and bony support of the toothand most often occurs with inflammation of the gingivaltissues.9 Features of Periodontitis are measured by as-

sessing risk with various gingival scoring methods whichmeasure gingival inflammation, usually bleeding; probingdepth; clinical attachment level (CAL); and radiographieevidence of loss of alveolar housing. Probing depths havebeen used in the past as a measure of periodontal disease;however, they are highly variable since they depend to a

great extent on gingival inflammation. Clinical attachmentloss is measured from a fixed point on the tooth (e.g.,cementoenamel junction, or the margin of a restoration)to the depth of the periodontal pocket. Relative attach-ment levels are measured from an arbitrary but fixed pointon a stent or instrument and are considered highly repro-ducible measures and better indications of destructive Per-iodontitis than probing depths.10 Measurement of alveolarcrestal bone loss is also considered an important definingfeature of Periodontitis and is correlated with clinical at-tachment loss and carried out as an independent measure.

Measurement of both CAL and radiographie measure-

ment of alveolar housing loss is difficult but informativein large-scale epidemiologie studies. However, for prac-tical reasons, clinical attachment loss is often used as thesingle measure of destructive periodontal disease (depen-

dent variable) in epidemiologie studies where risk is as-sessed. It is clear that assessment of radiographie alveolarbone height can give important insights into risk factorsfor Periodontitis since measurement of alveolar bone lossmay be more sensitive than CAL in assessing risk factorswhich affect bone metabolism and bone résorption as oc-

curs in periodontal disease. In fact, this has been observedby Grossi and coworkers.1112

Analysis of CAL or loss of alveolar bone as a contin-uous outcome variable is sometimes useful to establishcase definitions. Establishment of a case definition forPeriodontitis is by necessity arbitrary. Various cut-offpoints for CAL have been suggested; however, none isuniversally agreed upon. For example, Machtet et al. sug-gested that on the basis of error of the method (approxi-mately ± 2 mm), the cut-off should be greater than 2mm.13 They also argued that since histologie measure-

ments of normal periodontium showed that the apical ex-

tent of the junctional epithelium was at most 4 mm fromthe cementoenamel junction, this limit should be consid-ered in the definition of Periodontitis. Therefore, they se-lected 6 mm of attachment loss as a level associated withPeriodontitis. Since a single area may not reflect infec-tious Periodontitis but may result from non-infectious pro-cesses such as trauma, they argued that two sites of 6 mm

of clinical attachment loss, and one pocket depth of 5mm, would define a case of Periodontitis which is termed,"established Periodontitis." This definition, like all defi-nitions of a case, is somewhat arbitrary; however, it willlikely result in few false-positives for definition of dis-ease, and is of use in risk assessment studies.

Another approach is to use an extent and severity in-dex.14 Extent refers to the number of teeth in the mouthwith attachment loss of predetermined value above a

threshold, and severity is the mean attachment loss forthose teeth exhibiting the threshold level of attachmentloss. Perhaps a case definition which is based upon theextent and severity seen in any particular study is a usefulway to define a case and to dichotomize or further cate-

gorize members of a population with respect to periodon-tal disease. What is important, of course, is that there are

a sufficient number of cases and controls so that risk fac-tors can be assessed in these populations. Other estimatesof periodontal disease, such as tooth loss or mobility mea-

surements, have not met with reasonable success, possiblybecause mobility is difficult to measure objectively, andtooth loss is often related to factors other than periodontaldisease, such as caries and extractions for prostheticneeds.

Lack of a clear-cut definition of a case of Periodontitisalso has hindered longitudinal studies which attempted todefine incidence or occurrence of new cases, and oftenprogression of disease is used. The rate of periodontalattachment loss by using repeated measures and estab-lishing step-wise thresholds based upon factors which

1044 RISK FACTORS FOR PERIODONTAL DISEASESJ Periodontol

October 1996 (Supplement)

contribute to error including pocket depth, tooth type, andtooth location for each individual patient and examinerhas been used to assess risk factors.14

Analysis of DataCorrelation or univariate analysis is often seen in olderstudies of risk, especially in case-control or small cross-

sectional studies. The weakness of such an analysis re-sides in the inability of single correlation analysis to de-velop comprehensive models of the disease, since onlyone, or at most a few, potential risk factors can be ana-

lyzed at one time. Hence, they often account for only a

small amount of the variance in disease outcome. Also,univariate analysis does not allow adjustments for con-

founding variables. Powerful, modern statistical analysesusing multiple regression models, linear discriminateanalysis, and multivariate logistic regression have provid-ed the necessary tools to assess the role of risk factors inperiodontal diseases, since these analyses can account forconfounding and co-risk factors.'5

STUDIES OF BACKGROUND FACTORS ORDETERMINANTS FOR PERIODONTALDISEASES

AgingStudies of periodontal disease prevalence, or extent andseverity from epidemiologie studies show more periodon-tal disease in older age groups as compared to youngergroups.1'"'12'16-18 Also, studies have shown that there isgreater plaque development and more severe gingivitis inelderly persons as compared to younger persons, sug-gesting age-related effects.18 The question of why peri-odontal disease is more severe in elderly people is stillopen. Most studies suggest, however, that periodontal dis-ease is more severe in elderly people because of cumu-

lative tissue destruction over a lifetime rather than an age-related, intrinsic deficiency or abnormality which affectsperiodontal susceptibility. For example, an analysis of ep-idemiologie data from the National Health and NutritionExamination Survey I in the United States concluded thatwhen oral hygiene status was considered, age was muchless of a factor in determining periodontal disease.'8 Morerecent studies suggest that at least in the moderately el-derly (up to age 70) the rate of periodontal destruction isthe same throughout adulthood.1920 Therefore, it appearsthat age, per se, is not an intrinsic risk factor, at least untilage 70 or 75.

It is still unknown whether deterioration of host pro-tective mechanisms or accelerated host destructive mech-anisms or susceptibility to periodontal infection are al-tered in the very elderly (those beyond age 75). Theremay indeed be an increased risk of periodontal diseaseassociated with advanced age, per se.

RaceStudies by Beck and coworkers showed that approxi-mately three more times blacks had advanced periodontaldestruction as compared to whites of the same age cohort(65 years and above).21 In an analysis of risk indicatorsfor blacks and whites, there were more indicators relatedto socioeconomic status for blacks than for whites. Theyalso found, however, that P. intermedia was a risk indi-cator for blacks but not for whites. Hence, their analysisand the analysis of other studies addressing the issue ofrace found that when blacks and whites belonged to thesame socioeconomic group, differences in periodontaldisease often disappeared."'12'22

GenderPeriodontal disease is often reported in population studiesto be more prevalent or severe in males than in femalesat comparable ages. This was seen in several stud-ies.1"12'23 Males usually exhibit poorer oral hygiene thanfemales.24 However, when correcting for oral hygiene, so-

cioeconomic status, and age, male gender is associatedwith more severe periodontal disease when either attach-ment loss or bone height is used as the dependent vari-able."12 The reasons for these gender differences are notclear, and their elucidation may reveal important destruc-tive or protective mechanisms. There are gingival inflam-matory conditions found in females which are related tohormonal conditions, such as pregnancy gingivitis. In a

recent study, women aged 50 to 64 who were receivingestrogen replacement therapy had less gingival bleedingthan women of the same age who did not receive estrogenreplacement therapy. These differences persisted even af-ter adjusting for other possible confounding factors suchas higher education levels and lower plaque accumula-tion.25 Further assessment of the possible protective roleof female hormones in destructive periodontal diseasemay help understand the small but definite increase inperiodontal disease seen in males.

Socioeconomic StatusThe relationship of periodontal disease to socioeconomicstatus can be viewed globally, where wide variations insocioeconomic status among different populations are

compared. These studies comparing populations from de-veloping countries with those from industrialized coun-tries suggested that periodontal disease may be associatedwith nutritional deficiencies seen in developing coun-

tries.2226 However, Ramfjord et al. found that the peri-odontal condition of young men in India who exhibitedclinical symptoms of general malnutrition was not differ-ent from the periodontal condition of well-nourished in-dividuals.27 Similar findings were made in a nutritionalsurvey of 700 men in Alaska, where it was found that theperiodontal condition of individuals with nutritional de-ficiencies was not different from the periodontal status of

Volume 67Number 10 GENCO 1045

controls who were nutritionally healthy.28 Other studiescomparing the periodontal status of individuals in devel-oped and in developing countries of varying levels ofsocioeconomic status also failed to show a relationshipbetween periodontal disease and nutrition.2629-30 Anotherperspective comes from a study of periodontal disease indeveloped countries such as the United States, where itis found that periodontal disease is more severe in indi-viduals of lower socioeconomic status.23-24 However, inmore recent studies, when periodontal status was adjustedfor oral hygiene and smoking, the association betweenlower socioeconomic status and more severe periodontaldisease was not seen.11-12

GeneticsThe genetic aspects of localized juvenile Periodontitis are

covered in a recent review.31 Hart and coworkers also re-

ported a detailed analysis of the literature which they pro-pose supports autosomal modes of transmission of local-ized juvenile Periodontitis.32 They also note that juvenilePeriodontitis is likely heterogeneous and, indeed, some

rare X-linked forms may exist. Linkage analysis and iden-tification of abnormal genes in juvenile Periodontitis willultimately be needed to prove the genetic aspects of thisdisease and to explain, in part, the abnormality in neutro-phil function which appears to be familial.33

The genetic aspects of adult Periodontitis also havebeen addressed. In earlier studies, adult forms of peri-odontal disease were shown to be associated with humanleukocyte antigens. For example, negative associations ofPeriodontitis have been reported for HLA-A2.34 36 An in-crease of HLA-A9 also has been reported in patients witha severe form of adult periodontal disease.37-38 It is notclear, however, from the studies showing a positive as-sociation with HLA-A9 whether their populations includ-ed some individuals who had previously suffered fromjuvenile Periodontitis, since Reinholdt et al.39 reported an

increase of HLA-A9, as well as HLA-28 and HLA-W15,in localized juvenile Periodontitis patients. Studies ofadult Periodontitis patients who have not previously suf-fered from localized juvenile Periodontitis are needed toresolve this question.

Studies on 26 sets of twins (aged 12 to 17; seven mono-

zygotic and 19 dizygotic) found no evidence for differ-ences in gingival recession, gingival crevice depth, gin-gival bleeding, calculus, or plaque40 More recently, Mich-alowicz and coworkers41 studied 110 pairs of adult twinswhich included 63 pairs of monozygotic twins reared to-gether, 33 pairs of same-sex dizygotic twins reared to-gether, and 14 pairs of monozygotic twins reared apart.They reported significant genetic variance in the popula-tion for proportional alveolar bone height. A second re-

port by the same group found a genetic component forgingivitis, probing depth, attachment loss, and plaque.42These studies suggest a genetic component for periodon-

tal disease. However, the interactions are complex, andconfirmatory studies in twins, families, and studies of ge-netic polymorphisms are necessary before genetic influ-ences on periodontal disease can be understood.

STUDIES OF RISK FACTORS OR INDICATORSFOR PERIODONTAL DISEASES

Periodontal MicrofloraRecent studies have pointed to a few members of theperiodontal microflora as candidate pathogens for initia-tion and progression of periodontal disease. Recently, im-munofluorescent techniques have been developed foridentification and semi-quantitation of these organisms inthe large numbers of subgingival samples taken in epi-demiologie studies. These microbial epidemiologie stud-ies have shed light on the role of specific periodontalorganisms in periodontal disease. Carlos and coworkers43found that the presence of P. intermedia (formerly calledBacteroides intermedius), along with gingival bleedingand calculus, was correlated with attachment loss in a

group of Navajo adolescents aged 14 to 19. Grossi andcoworkers tested a panel of microorganisms including A.actinomycetemcomitans, B. forsythus, Campylobacterrectus, Capnocytophaga species, Eubacterium sabur-reum, F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis, and P. intermedia." 2Of these organisms, only two, P. gingivalis and B. for-sythus, were associated with increased risk for attachmentloss as a measure of periodontal disease after adjustmentfor age, plaque, smoking, and diabetes." The same two

organisms were also identified as risk indicators for peri-odontal alveolar bone loss.12 Interestingly, in both studiesCapnocytophaga species were found in higher levels insubjects with lower levels of periodontal disease, sug-gesting that these species may be part of the normal flora.A study of oral bacteria as risk indicators for Periodontitisin older adults found that the differences in the prevalenceof periodontal disease between blacks and whites is ex-

plained, in part, by different prevalences of P. gingivalisand P. intermedia.*4 This study also found that non-bac-terial factors such as having visited the dentist more than3 years ago, having fewer teeth, and using tobacco were

associated with periodontal diseases as evidenced by hav-ing a loss of attachment of 7 mm or greater. The epide-miologie data of Beck and coworkers44 suggest that spe-cific bacteria such as P. gingivalis and P. intermedia playa role in periodontal disease in older adults. The impor-tance of specific bacteria in periodontal destruction ishighlighted by the finding that the quantity of total plaqueaccumulation is only weakly correlated with destructiveperiodontal disease.11-12,45

SYSTEMIC DISEASES AND CONDITIONS ANDPERIODONTAL DISEASESSeveral recent studies have addressed the question ofwhich systemic disorders or diseases increase the risk for

1046 RISK FACTORS FOR PERIODONTAL DISEASESJ Periodontol

October 1996 (Supplement)

periodontal disease. Grossi and coworkers studied a largenumber of systemic diseases as risk indicators for peri-odontal disease in a population of 1,426 subjects aged 25to 75 residing in Erie County, New York." '2 It was foundthat there were 17 systemic diseases and conditions re-

ported in enough frequency in this population to be ableto assess whether or not they were risk indicators for peri-odontal disease. These included allergy, hives, asthma,hay fever, high blood pressure, arthritis, anemia, cancer,gall bladder disease, mononucleosis, kidney disease, thy-roid disease, gout, venereal disease, hepatitis, diabetes,angina, and cataracts. Of these diseases, only diabetesmellitus was found to be associated with more severe de-structive periodontal disease, when measuring attachmentlevel as a dependent variable. It is of interest that whenmeasuring clinical attachment level or bone loss, allergieswere found to be associated with less severe periodontaldisease, an association which may be related to medica-tions taken by individuals with allergies. Furthermore,anemia was found to be associated with less periodontaldisease when using attachment loss as a measurement,and a history of kidney disease was associated with lessperiodontal disease when using bone loss as a measure-ment. The explanation of these latter findings is not clear;however, it does illustrate the potential for alveolar bonemeasurements and probing attachment measurements togive a different assessment of risk indicators or, in thiscase, protective factors. In a previous study of 1,300 hos-pitalized patients, no correlations were seen with variousdiseases.46 However, in a larger study of 4,000 subjects,of all the diseases assessed, only patients with diabetesmellitus had a statistically significantly higher prevalenceof periodontal disease than others47

Population-based studies may not have a sufficientnumber of individuals afflicted with rare or uncommon

systemic diseases to derive any conclusion about theirrelationship to periodontal disease. Case-control studiesor case histories have provided hypotheses regarding theassociations of these rare conditions with periodontal dis-ease. For example, diseases associated with neutrophil de-fects such as Chediak-Higashi syndrome, Down's syn-drome, and Papillon-LeFèvre syndrome have been shownfrom case-control and case history studies to be associ-ated with severe forms of destructive Periodontitis (seeGenco and Löe for review31). Acquired immunodeficiencysyndrome (AIDS) also appears to be associated with se-

vere forms of gingivitis and Periodontitis. The associationof risk factors in HIV-seropositive or AIDS patients is an

active area of research, and it appears that reduction ofCD4 cell numbers and smoking are associated with severe

forms of periodontal disease in these patients.31

Diabetes MellitusA series of population-based epidemiologie studies haselucidated the relationship between destructive periodon-

tal disease and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus(NIDDM). Some of these studies were carried out on a

population with the highest reported prevalence ofNIDDM, the Pirna Indians from the Gila River IndianCommunity in Arizona.48-50 In one study of this popula-tion, an analysis was carried out by using two indepen-dent measures of periodontal disease-attachment loss andradiographie bone loss.48 The 3,219 subjects, aged 5 toover 95, were evaluated for their diabetic status by a

2-hour glucose tolerance test and for periodontal diseaseby assessing clinical attachment levels and interproximalalveolar bone levels. They were also evaluated for a largenumber of general and oral health abnormalities. Diabetesprevalence ranged from 3% in the 5- to 24-year-old agegroup to 60% to 70% in the 45 and older age group. Inall groups studied, subjects with diabetes mellitus had a

higher prevalence of periodontal disease when using ei-ther measure of periodontal disease, even after correctingfor age, plaque, and other possible confounding factors.These studies indicate that diabetes is a risk indicator forperiodontal disease.

A further study was carried out on this population inwhich the correlation of diabetes and periodontal diseasewas further analyzed to determine whether it could beaccounted for by age, gender, calculus, plaque, gingivalindex, fluorosis, or caries, factors that might confound therelationship with diabetes mellitus.49 Only diabetic status,age, and the presence of subgingival calculus were sig-nificantly associated with increased prevalence and se-

verity of periodontal destruction in this population. Next,Nelson and coworkers carried out a longitudinal study inwhich the incidence of periodontal disease was deter-mined in a subset of 701 Pirna Indians, aged 15 to 54,who initially had little or no evidence of periodontal dis-ease.50 The age- and gender-adjusted incidence of peri-odontal disease in NIDDM subjects was found to be 78cases per 1,000 person years, significantly higher than therate of 29 cases per 1,000 person years in subjects withoutdiabetes (relative risk 2.6). This longitudinal study pro-vides convincing evidence that non-insulin-dependent di-abetes mellitus is a risk factor for periodontal disease.Several recent studies of large populations, taking intoconsideration the effects of age on periodontal disease,have consistently found that diabetes mellitus is a riskfactor for periodontal disease.48-51

With respect to insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus(IDDM), Cianciola et al.52 found that 11.3% to 16% ofthose aged 13 to 18 had Periodontitis, and after age 18more than 25% had Periodontitis. This is compared to1.7% of the 13- to 18-year-old non-diabetic controls whohad Periodontitis. Hence, insulin-dependent diabetics inthe teenage years appear to be more susceptible to de-structive Periodontitis. Glavind et al.53 found that betweenthe ages of 30 to 40, insulin-dependent diabetics had an

increase in periodontal breakdown as compared to non-

Volume 67Number 10 GENCO 1047

diabetics. Furthermore, they showed that those who hadgreater duration of diabetes and diabetics with retinalchanges also had greater loss of periodontal attachmentthan the others. There are several studies that failed todemonstrate significant differences in periodontal diseasebetween diabetics and non-diabetic subjects.54-56 However,clinical studies comparing diabetics with non-diabeticsmust consider not only age matching but also the agerange of the patients before making conclusions. Patientstoo young may not show differences in the prevalence or

severity of periodontal disease between groups with andwithout diabetes, since the onset of Periodontitis appearsto be around puberty. On the other hand, patients who are

older may not have differences in periodontal disease be-cause of tooth extractions.

SmokingThere is a long history of association between tobaccosmoking and periodontal disease.57-59 However, the per-ception that greater levels of plaque and calculus in smok-ers than non-smokers fully accounted for the associationleft the clinical community largely unconvinced of theimportance of smoking per se in periodontal disease. In1983, Ismail et al.60 analyzed smoking and periodontaldisease and found that after adjusting for potential con-

founding variables such as age, oral hygiene, gender, andsocioeconomic status, smoking remained a major risk in-dicator for periodontal diseases. In studies by Grossi etal.,"12 smoking was shown to be a strong risk indicatorfor periodontal disease with an odds ratio of 2.0 to 5.0when using attachment loss as a measurement, and oddsratios of 1.5 to 7.0 when using alveolar bone loss as themeasure of periodontal disease after adjusting for age,gender, socioeconomic status, plaque, and calculus. Gros-si and coworkers found a direct and linear dose responsebetween the level of smoking (pack years) and destructivePeriodontitis, lending further support to smoking as a riskfactor for periodontal disease."12 There is mounting evi-dence that smokers also have a different periodontal mi-croflora61 and also heal less satisfactorily after periodontaltherapy than non-smokers.62 It is likely that smoking is a

major risk factor for destructive periodontal disease inman, and that modification of this risk factor is importantin the treatment and prevention of periodontal disease.

Other Possible Risk Factors for Periodontal DiseasesThere are preliminary studies which suggest that stress,distress, and coping behaviors63 are associated with in-creased severity of destructive periodontal disease. Thisassociation has long been suspected but was difficult to

scientifically assess before valid, reproducible measures

of stress, distress, and coping behaviors were applied to

periodontal risk assessment studies. Instruments for as-

sessing these psychosocial variables are now availablewhich allow this to be done, and the indication is that

stress, distress, and coping behaviors are important riskindicators for periodontal disease. In the Erie Countystudy reported by Moss,63 it was found that financial stresswas related to more severe periodontal disease and thateffective coping behaviors modulated this effect.

Osteopenia/OsteoporosisOsteopenia and osteoporosis have been studied in case-

control and anecdotal studies (see Genco and Lòe31 forreview). For example, in a study by Danieli, 208 women

aged 60 to 69 were assessed for smoking habits, peri-odontal disease, and current osteoporosis severity basedupon the percentage of cortical area at the metacarpalmidshaft.64 In this study, 52% of the smokers, 26% of thenon-smokers, and only 8% of the non-osteoporotic non-smokers required dentures since reaching the age of 50.This series of case reports suggests that osteoporosis andsmoking are important factors promoting tooth loss. Inanother study, Kribbs compared osteoporotic patientswith controls and found that the osteoporotic group hada greater percentage of subjects who were edentulous orhad greater tooth loss.65 However, the reason for tooth lossis difficult to determine, and it is not clear whether toothloss was weakly or significantly associated with more se-vere Periodontitis.

Evaluation of osteopenia and periodontal disease af-fords an interesting insight into metabolic bone abnor-malities and locally induced bone résorption caused byperiodontal infection. A direct association between skel-etal and mandibular osteopenia and destructive periodon-tal disease as measured by loss of interproximal alveolarbone in postmenopausal women has been reported byWactawski-Wende and coworkers.66

SUMMARYExtensive evaluation of risk factors for periodontal dis-ease has led to the identification of the following as riskindicators: P. gingivalis, B. forsyihus, P. intermedia, gen-der, and age. Both type I (insulin-dependent) and type II(non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus are importantsystemic diseases which are risk factors for periodontaldisease. Smoking is perhaps one of the most importantrisk factors for periodontal disease, increasing the risk 2-to 7-fold depending on the level of smoking.

Future studies will help us to better understand the roleof osteoporosis, as well as stress, distress, and coping as

they increase the susceptibility of individuals to peri-odontal disease. These associations and the strength ofevidence supporting these are summarized in Table 2. Anew generation of studies is needed not only to identifyother potential risk factors for periodontal diseases, butalso to determine the effective interventions directed tomodulating important risk factors and to assess their ef-fects on the initiation and progression of periodontal dis-ease, and their effects on periodontal therapy.

1048 RISK FACTORS FOR PERIODONTAL DISEASESJ Periodontol

October 1996 (Supplement)

Table 2. The Strength of Association of Putative Risk Factors and Destructive Periodontal Disease

PutativeCase Case- Cross-

Report Control Sectional Longitudinal Intervention

1. Specific bacteriaP. gingivalisB. forsythusP. intermedia

2. Gendermale

3. Age

yesyesyes

yesyes

4. Diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) yes

IDDM yes5. Smoking NR

6. Osteoporosis yes7. Stress, distress, coping8. PMN disorders yes

yesyesyes

NRyesyes

yesyes

yesyesyes

yesyesyes

yesyesyes

yesyes

yesyesNR

yesyesyes

NRno to 7th decadeyes

NRyes

NRNRyes (case series)

yesyesyes

NRNRyes (treatment re-

duces glycosy-lated hemoglo-bin)

NRyes (smokers heal

poorly)NRNRNR

NR = not reported, or not relevant.

REFERENCES1. Miller AJ, Brunelle JA, Carlos JP, Brown LJ, Löe H. Oral Health

of United States Adults: National Findings. Bethesda, MD: NationalInstitute of Dental Research; 1987. NIH publication no. 87-2868.

2. Hugoson A, Jordan T. Frequency distribution of individuals aged20-70 years according to severity of periodontal disease. CommunDent Oral Epidemiol 1982;10:187-192.

3. Brown LJ, Löe H. Prevalence, extent, severity and progression ofperiodontal disease. Periodontol 2000 1993;2:57-71.

4. Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Microbial etiological agents of destruc-tive periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000 1994;5:78-111.

5. Slots J, Feik D, Rams TE. Age and sex relationships of superin-fecting microorganisms in Periodontitis patients. Oral Microbiol Im-munol 1990;5:305-308.

6. Last JM. A Dictionary of Epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York, NY:Oxford University Press; 1988.

7. Beck JD. Methods of assessing risk for Periodontitis and developingmultifactorial models. J Periodontol 1994;65:468-478.

8. Ibrahim M. Epidemiology and Health Policy. Rockville, MD: AspenSystems Corporation; 1985.

9. Genco RJ. Classification of clinical and radiographie features ofperiodontal disease. In: Genco RJ, Goldman HM, Cohen DW, eds.Contemporary Periodontics. St. Louis: The CV Mosby Company;1990:63.

10. Goodson JM. Selection of suitable indicators of Periodontitis. In:Bader JD, ed. Risk Assessment in Dentistry. Chapel Hill, NC: Uni-versity of North Carolina Dental Ecology; 1990:69.

11. Grossi SG, Zambón JJ, Ho AW, et al. Assessment of risk for peri-odontal disease. I. Risk indicators for attachment loss. J Periodontol1994;65:260-267.

12. Grossi SG, Genco RJ, Machtei EE, et al. Assessment of risk forperiodontal disease. II. Risk indicators for alveolar bone loss. J Per-iodontol 1995;66:23-29.

13. Machtei EE, Norderyd J, Koch G, Dunford R, Grossi S, Genco RJ.The role of periodontal attachment loss in subjects with establishedPeriodontitis. J Periodontol 1993;64:713-718.

14. Carlos JP, Wolfe MD, Kingman A. The extent and severity index:A simple method for use in epidemiologie studies of periodontaldisease. J Clin Periodontol 1986;13:500-505.

15. Stamm JW, Stewart PW.Bohannan HM, Disney JA, Graves RC,Abernathy JR. Risk assessment for oral diseases. Adv Dent Res1991;5:4-17.

16. Marshall-Day CD, Stevens RG, Quigley LF Jr. Periodontal diseaseprevalence and incidence. J Periodontol 1955;26:185-203.

17. Schei O, Waerhaug J, Lövdal A, Arno A. Alveolar bone loss asrelated to oral hygiene and age. J Periodontol 1959;30:7-16.

18. Abdellatif HM, Burt A. An epidemiological investigation into therelative importance of age and oral hygiene status as determinantsof Periodontitis. J Dent Res 1987;66:13-18.

19. Holm-Pedersen P, Agerbaek N, Theilade E. Experimental gingivitisin young and elderly individuals. J Clin Periodontol 1975;2:14-24.

20. Machtei EE, Dunford R, Grossi SG, Genco RJ. Cumulative natureof periodontal attachment loss. J Periodont Res 1994;29:361-364.

21. Beck JD, Koch GG, Rozier RG, Tudor GE. Prevalence and riskindicators for periodontal attachment loss in a population of oldercommunity-dwelling blacks and whites. J Periodontol 1990;61:521-528.

22. Russell AL. Geographical Distribution and Epidemiology of Peri-odontal Disease. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1960(WHO/DH/33/34).

23. U.S. Public Health Service, National Center for Health Statistics.Periodontal Disease in Adults, United States 1960-1962. PHS Pub-lication No. 1000, Series 11, No. 12. Washington, DC: GovernmentPrinting Office; 1965.

24. U.S. Public Health Service, National Center for Health Statistics.Basic Data on Dental Examination Findings of Persons 1—75 Years;United States, 1971-1974. DHEW Publication No. (PHS) 79-1662,Series 11, No. 214. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office;1979.

25. Norderyd OM, Grossi SG, Machtei EE, et al. Periodontal status ofwomen taking postmenopausal estrogen supplementation. J Perio-dontol 1993;64:957-962.

26. Russell AL. Periodontal disease in well and malnourished popula-tions. Arch Environ Health 1962;5:153-157.

27. Ramfjord SP, Emslie RD, Greene JC, Held AJ, Waerhaug J. Epi-demiological studies of periodontal diseases. Am J Public Health1968;58:1713-1722.

28. Russell AL, Consolazio CF, White CL. Periodontal disease and nu-

trition in Eskimo scouts of the Alaska national guard. J Dent Res1961;40:38-43.

29. Waerhaug J. Prevalence of periodontal disease in Ceylon. Associa-tion with age, sex, oral hygiene, socio-economic factors, vitamindeficiencies, malnutrition, betel and tobacco consumption and ethnicgroup. Final report. Acta Odontol Scand 1967;25:205-231.

Volume 67Number 10 GENCO 1049

30. Wertheimer FW, Brewster RH, White CL. Periodontal disease andnutrition in Thailand. J Periodontol 1967;38:100-104.

31. Genco RJ, Löe H. The role of systemic conditions and disorders inperiodontal disease. Periodontol 2000 1993;2:98-116.

32. Hart TC, Marazita ML, Schenkein HA, Diehl SR. Re-interpretationof the evidence for X-linked dominant inheritance of juvenile Per-iodontitis. J Periodontol 1992;63:169-173.

33. Van Dyke TE, Schweinebraten M, Cianciola LJ, Offenbacher S,Genco RJ. Neutrophil Chemotaxis in families with localized juvenilePeriodontitis. J Periodont Res 1985;20:503-514.

34. Terasaki PI, Kaslick RS, West TL, Chasens AI. Low HL-A2 fre-quency and Periodontitis. Tissue Antigens 1975;5:286-288.

35. Kaslick RS, West TL, Chasens AI. Association between ABO bloodgroups, HL-A antigens and periodontal diseases in young adults: Afollow-up study. J Periodontol 1980;51:339-342.

36. Kaslick RS, West TL, Chasens AI, Terasaki PI, Lazzara R, WeinbergS. Association between HL-A2 antigen and various periodontal dis-eases in young adults. J Dent Res 1975;54:424.

37. Klouda PT, Porter SR, Scully C, et al. Association between HLA-A9and rapidly progressive Periodontitis. Tissue Antigens 1986;28:146-149.

38. Amer A, Sing G, Drake C, Dolby AE. Association between HLAantigens and periodontal disease. Tissue Antigens 1988;31:53-58.

39. Reinholdt J, Bay I, Svejgaard A. Association between HLA-antigensand periodontal disease. J Dent Res 1977;56:1261-1263.

40. Ciancio SC, Hazen SP, Cunat JJ. Periodontal observations in twins./ Periodont Res 1969;4:42-45.

41. Michalowicz BS, Aeppli D, Virag JG, et al. Periodontal findings inadult twins. J Periodontol 1991;62:293-299.

42. Michalowicz BS, Aeppli DP, Duba RK, et al. A twin study of ge-netic variation in proportional radiographie alveolar bone height. /Dent Res 1991;70:1431-1435.

43. Carlos JP, Wolfe MD, Zambón JJ, Kingman A. Periodontal diseasein adolescents: Some clinical and microbiologie correlates of attach-ment loss. / Dent Res 1988;66:1510-1514.

44. Beck JD, Koch GG, Zambón JJ, Genco RJ, Tudor GE. Evaluationof oral bacteria as risk indicators for Periodontitis in older adults. JPeriodontol 1992;63:93-99.

45. Haffajee AD, Socransky SS, Dzink JL, Taubman MA, Ebersole JL,Smith DJ. Clinical, microbiological and immunological features ofsubjects with destructive periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol1988;15:240-246.

46. Sandler HC, Stahl SS. Prevalence of periodontal disease in a hos-pitalized population. J Dent Res 1960;39:439-449.

47. Sandler HC, Stahl SS. The influence of generalized diseases on clin-ical manifestations of periodontal diseases. J Am Dent Assoc 1954;49:656-667.

48. Shlossman M, Knowler WC, Pettitt DJ, Genco RJ. Type 2 diabetesmellitus and periodontal disease. J Am Dent Assoc 1990,121:531—536.

49t Emrich LJ, Shlossman M, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease in non-

insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol 1991 ;62:123—130.

50. Nelson RG, Shlossman M, Budding LM, et al. Periodontal diseaseand non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in Pirna Indians. Dia-betes Care 1990;13:836-840.

51. Oliver RC, Tervonen T. Periodontitis and tooth loss: Comparing di-abetics with the general population. J Am Dent Assoc 1993;124:71-76.

52. Cianciola LJ, Park BH, Bruck E, Mosovich L, Genco RJ. Prevalenceof periodontal disease in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (juve-nile diabetes). J Am Dent Assoc 1982;104:653-660.

53. Glavind L, Lund B, Löe H. The relationship between periodontalstate and diabetes duration, insulin dosage, and retinal changes. JPeriodontol 1968;39:341-347.

54. Barnett ML, Baker RL, Yancey JM, MacMillan DR, Kotoyan M.Absence of Periodontitis in a population of insulin-dependent dia-betes mellitus (IDDM) patients. J Periodontol 1984;54:402-405.

55. Hove KA, Stallard RE. Diabetes and the periodontal patient. J Per-iodontol 1970;41:713-718.

56. Nichols C, Laster LI, Bodak-Gyovai LZ. Diabetes mellitus and peri-odontal disease. J Periodontol 1978;49:85-88.

57. Pindborg JJ. Tobacco and gingivitis. I. Statistical examination of thesignificance of tobacco in the development of ulceromembranousgingivitis and in the formation of calculus. J Dent Res 1947;26:261-264.

58. Frandsen A, Pindborg JJ. Tobacco and gingivitis. III. Difference inaction of cigarette and pipe smoking. / Dent Res 1949;28:464-465.

59. Solomon HA, Priore RL, Bross IDJ. Cigarette smoking and peri-odontal disease. J Am Dent Assoc 1968;77:1081-1084.

60. Ismail AI, Burt BA, Eklund SA. Epidemiologie patterns of smokingand periodontal disease in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc 1983;106:617-623.

61. Zambón JJ, Grossi SG, Machtet EE, Ho AW, Dunford R, Genco RJ.Cigarette smoking increases the risk for subgingival infection withperiodontal pathogens. J Periodontol 1996;67(suppl):1050-1054.

62. Grossi SG, Skrepcinski FB, DeCaro Zambón JJ, Cummins D,Genco RJ. Response to periodontal therapy in diabetics and smok-ers. J Periodontol 1996;67(suppl):1094-1102.

63. Moss ME, Beck JD, Kaplan BH, et al. Exploratory case-controlanalysis of psychosocial factors and adult Periodontitis. J Periodon-tol 1996;67(suppl): 1060-1069.

64. Danieli HW. Postmenopausal tooth loss. Contributions to edentulismby osteoporosis and cigarette smoking. Arch Intern Med 1983;143:1678-1682.

65. Kribbs PJ. Comparison of mandibular bone in normal and osteo-

porotic women. J Prosthet Dent 1990;63:218-222.66. Wactawski-Wende J, Grossi SG, Trevisan M, et al. The role of os-

teopenia in periodontal disease. J Periodontol 1996;67(suppl):1076-1084.

Send reprint requests to: Dr. Robert J. Genco, State University of NewYork at Buffalo, School of Dental Medicine, Department of Oral Biol-ogy, 115 Foster Hall, Buffalo, NY 14214.