TuanV.Nguyen% · • Calculate’PVvalue’ ... Study Samplesize%% Proporon%% Pvalue % 1 20...

Transcript of TuanV.Nguyen% · • Calculate’PVvalue’ ... Study Samplesize%% Proporon%% Pvalue % 1 20...

Tuan V. Nguyen Gene$cs Epidemiology of Osteoporosis Lab

Garvan Ins$tute of Medical Research

Garvan Ins$tute Biosta$s$cal Workshop 21/4/2014 © Tuan V. Nguyen

Introduction to Bayes Factor

• Problem of reproducibility

• P value revisited

• Bayes Factor

• R func$ons

Lack of reproducibility

• Observa1onal studies: out of 20 exci$ng findings, only 1 was replicated by NIH sponsored clinical trial

• Basic research and animal models: Bayer Healthcare reviewed 67 high-‐profile findings, <1/4 were replicated

• Randomized clinical trials: 49 famous trials (1990-‐2003):

– 7 (16%) were contradicted by subsequent studies

– 20 (44%) were replicated

– 11 (24%) remained unchallenged

Ioannidis et al JAMA 2005; JNCI 2007

Reasons for lack of reproducibility

• Publica$on bias • Rewards for "posi$ve" results • Experimental biases

• Sta1s1cal biases: Confounding; uncri$cal use of P-‐values • Bad sta1s1cs: Failure to adjust for

– mul$ple tests of hypothesis

– mul$ple looks at data (eg data torture)

– mul$ple sta$s$cal analyses (eg fishing expedi$on)

Multiple comparisons

• 10,000 compounds were screened for biological ac$vity

• 500 passed the ini$al screen à studied in vitro

• 25 went to phase I trial (animal trial)

• 1 went to phase II trial (human trial)

"Basic research is like shoo-ng an arrow in the air and, where it lands, pain-ng a target" (Hosmer Adkins)

P-‐value: a revisit

Test of significance procedure

• Propose a hypothesis; state a null hypothesis (H0)

• Collect data (eg experiments)

• Calculate P-‐value P = Pr(data | H0 is true)

If P < 0.05, the finding is considered "significant"

Test your understanding

P-‐value is ... In terms of prob ... Probability that the null hypothesis (no effect) is true P(H0) Probability of the data under H0 P(x | H0) Probability of H0 under the data P(H0 | x) Probability that the data (or more extreme data) if H0 were true

P(X ≥ x | H0)

P-‐value = 0.04

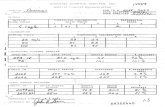

Sample size and "significance"

Study Sample size Propor1on P value

1 20 15 (0.75) 0.041

2 200 114 (0.57) 0.041

3 2000 1046 (0.525) 0.041

4 2,000,000 1,001,445 (0.5007) 0.041

Four hypothe$cal studies ...

Consider this study

Consider this study

How would you interpret this ?

P-‐value = 0.04

Another study (hypothetical)

set.seed(666)

n1 = 100; n2 = 100;

mean1 = 103; mean2 = 98;

sd = 15;

x1 = rnorm(n1, mean1, sd)

x2 = rnorm(n2, mean2, sd)

x = c(x1, x2)

group = c(rep("A", n1), rep("B", n2))

boxplot(x ~ group)

t.test(x ~ group)

> t.test(x ~ group)

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: x by group

t = 2.3455, df = 196.13, p-value = 0.02 alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not

equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval: 0.8583085 9.9252430 sample estimates:

mean in group A mean in group B

102.0000 96.6082

A B

6080

120

A surge of P values near 0.05

Multiple tests of hypothesis

• A "significant result" could be a chance finding • Example:

– Test 5 hypotheses

– Each test, we have type I error 5%

– Probability that one significant result by chance is 1 – (1 – 0.05)^5 = 23%

• In general, the prob of obtaining (by chance alone) at least 1 significant result in k tests is 1 – (1 – a)^k

Traditional statistical inference

Tradi$onal sta$s$cal rules are a collec$on of principles and conven$ons to avoid errors over the long run; they do not tell us how likely our claims are to be true, nor do they easily apply to individual results.

Bayes Factor

Thomas Bayes (c. 1702 – April 17, 1761)

Bayes Theorem: basic fact

Bayes theorem

Likelihood Prior probability of hypothesis x

P(D | H) P(H) P(H | D)

Posterior probability of hypothesis =

Bayes theorem -- again

Likelihood Prior probability of hypothesis x

P(D | H) P(H) P(H | D)

Posterior probability of hypothesis =

D: Data H: Hypothesis

In Bayesian inference, we need 2 key elements: data and prior informa1on

Bayes theorem – in ratio terms

Likelihood (Bayes Factor)

Prior probability of hypothesis x Posterior probability

of hypothesis =

D: Data H: Hypothesis

In Bayesian inference, we need 2 key elements: data and prior informa1on

€

€

P H1( )P H0( )

€

P H1 |D( )P H0 |D( )

€

P D |H1( )P D |H0( )

Bayes Factor (BF)

A more objec$ve way to measure evidence (no need prior informa$on)

BF10 =P data |H1( )P data |H0( )

Question

• Hypotheses – H0: there is no effect

– H1: there is effect

• Do my data (D) favor H0 or H1?

• Answer: Bayes Factor

Bayes factor: A metric of evidence

BF Meaning >1 Data support H1 over H0 <1 Data support H0

1 Data support neither H0 nor H1

BF10 =P data |H1( )P data |H0( )

Interpretation of BF

BF Interpreta1on

>100 Decisively favors H1

30 to 100 Very strong evidence for H1

10 to 30 Strong evidence for H1

3 to 10 Substan$al evidence for H1

1 to 3 Weak evidence for H1

1 No evidence

0.3 to 1 Weak evidence for H0

0.1 to 0.3 Substan$al evidence for H0

0.03 to 0.1 Strong evidence for H0

0.01 to 0.03 Very strong evidence for H0

<0.01 Decisive evidence for H0

Bayes Factor: technical stuff

• Let effect size be δ = μ / σ

€

€

f D |δ,σ 2( ) = N yi |σ,δ( )i=1

N

∏

• Under H0, δ = 0, σ unknown

• Under H1, δ ≠ 0, σ unknown, use Jeffrey-‐Zellner-‐Siow BF

€

BF =

1+t 2

N −1#

$ %

&

' (

−N / 2

1+ Nτ 2( )−1/ 2 1+t 2

1+ Nτ 2( ) N −1( )

#

$ % %

&

' ( (

−N / 2

Use R package BayesFactor à easier and faster

Bayes Factor for 2 groups

set.seed(666)

n1 = 100; n2 = 100;

mean1 = 103; mean2 = 98;

sd = 15;

x1 = rnorm(n1, mean1, sd)

x2 = rnorm(n2, mean2, sd)

x = c(x1, x2)

group = c(rep("A", n1), rep("B", n2))

library(BayesFactor)

dat = data.frame(x, group)

bf = ttestBF(formula = x ~ group, data=dat)

bf

Bayes Factor interpretation

> bf Bayes factor analysis -------------- [1] Alt., r=0.707 : 1.976683 ±0% Against denominator: Null, mu1-mu2 = 0 --- Bayes factor type: BFindepSample, JZS

Interpreta1on: The data are 1.98 1mes more likely under the alterna1ve hypothesis (ie there is an effect) than under the null hypothesis of no effect

95% credible interval

> chains = posterior(bf, iterations=10000)

> dif = chains[,2]

> hist(dif, col="blue", border="white")

> quantile(dif, c(0.025, 0.50, 0.975))

2.5% 50% 97.5%

0.6163938 5.0365395 9.4904096

Histogram of dif

dif

Frequency

0 5 10

0500

1000

1500

BF, data, and sample size

• Larger sample size studies provide stronger evidence?

BF01, data, and sample size

http://daniellakens.blogspot.com.au/2014/09/bayes-factors-and-p-values-for.html

Prior probability of hypothesis, BF, and posterior probability of hypothesis

• Prior probability = what do you think the hypothesis is true (before the study is conducted)

• BF = evidence

• Posterior probability = probability of hypothesis awer seeing the evidence

Approximate BF

• Edwards (1963): rela$onship between BF and test sta$s$c (for t and z test)

• Minimum BF

minBF = exp −0.5z2( )

Biểu đồ tiên lượng (Nomogram) BF

RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access

A nomogram for P valuesLeonhard Held

Abstract

Background: P values are the most commonly used tool to measure evidence against a hypothesis. Severalattempts have been made to transform P values to minimum Bayes factors and minimum posterior probabilities ofthe hypothesis under consideration. However, the acceptance of such calibrations in clinical fields is low due toinexperience in interpreting Bayes factors and the need to specify a prior probability to derive a lower bound onthe posterior probability.

Methods: I propose a graphical approach which easily translates any prior probability and P value to minimumposterior probabilities. The approach allows to visually inspect the dependence of the minimum posteriorprobability on the prior probability of the null hypothesis. Likewise, the tool can be used to read off, for fixedposterior probability, the maximum prior probability compatible with a given P value. The maximum P valuecompatible with a given prior and posterior probability is also available.

Results: Use of the nomogram is illustrated based on results from a randomized trial for lung cancer patientscomparing a new radiotherapy technique with conventional radiotherapy.

Conclusion: The graphical device proposed in this paper will enhance the understanding of P values as measuresof evidence among non-specialists.

BackgroundP values are the most commonly used tool to measureevidence against a hypothesis [1]. The P value is definedas the probability, under the assumption of no effect(the null hypothesis H0), of obtaining a result equal toor more extreme than what was actually observed. Thecomplexity of this definition has led to widespread mis-interpretations and criticisms [2-5]. Indeed, P values areoften misinterpreted (a) as the probability of obtainingthe observed data under the assumption of no realeffect, (b) as an “observed” type-I error rate, (c) as thefalse discovery rate, i.e. the probability that a significantfinding is “false positive”, and (d) as the (posterior)probability of the null hypothesis [6].The latter misinterpretation has given rise to interest-

ing work on the connection between P values and(posterior) probabilities of the null hypothesis. Within aBayesian framework, the posterior probability is a func-tion of the prior probability and the so-called Bayesfactor, which summarizes the evidence against the nullhypothesis.

Several attempts have been made to transformP values to lower bounds on the Bayes factor and theresulting posterior probability of the null hypothesis[7-11]. In this context Bayes factors are usually orientedas P values such that smaller values provide strongerevidence against the null hypothesis. These techniquescalibrate P values such that an interpretation as mini-mum Bayes factor or minimum posterior probability isjustified. Although the different approaches do notresult in identical calibration scales, a universal findingis that the evidence against a simple null hypothesis isby far not as strong as the P value might suggest.However, the acceptance of calibrated P values in clin-

ical fields is low. Minimum Bayes factors have theadvantage that they do not depend on the prior prob-ability of the null hypothesis [9], but their interpretationrequires an intuitive understanding of odds, similar tolikelihood ratios in diagnostic studies [12]. Clinicians,however, prefer to think in terms of probabilities. Thecalculation of the minimum posterior probability, on theother hand, requires to decide on a prior probability ofthe null hypothesis. Fixing a prior probability may bedifficult for the clinician, who would perhaps prefer toinvestigate - for a given P value - the dependence of the

Correspondence: [email protected] Unit, Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University ofZurich, Hirschengraben 84, 8001 Zurich, Switzerland

Held BMC Medical Research Methodology 2010, 10:21http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/10/21

© 2010 Held; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative CommonsAttribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction inany medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access

A nomogram for P valuesLeonhard Held

Abstract

Background: P values are the most commonly used tool to measure evidence against a hypothesis. Severalattempts have been made to transform P values to minimum Bayes factors and minimum posterior probabilities ofthe hypothesis under consideration. However, the acceptance of such calibrations in clinical fields is low due toinexperience in interpreting Bayes factors and the need to specify a prior probability to derive a lower bound onthe posterior probability.

Methods: I propose a graphical approach which easily translates any prior probability and P value to minimumposterior probabilities. The approach allows to visually inspect the dependence of the minimum posteriorprobability on the prior probability of the null hypothesis. Likewise, the tool can be used to read off, for fixedposterior probability, the maximum prior probability compatible with a given P value. The maximum P valuecompatible with a given prior and posterior probability is also available.

Results: Use of the nomogram is illustrated based on results from a randomized trial for lung cancer patientscomparing a new radiotherapy technique with conventional radiotherapy.

Conclusion: The graphical device proposed in this paper will enhance the understanding of P values as measuresof evidence among non-specialists.

BackgroundP values are the most commonly used tool to measureevidence against a hypothesis [1]. The P value is definedas the probability, under the assumption of no effect(the null hypothesis H0), of obtaining a result equal toor more extreme than what was actually observed. Thecomplexity of this definition has led to widespread mis-interpretations and criticisms [2-5]. Indeed, P values areoften misinterpreted (a) as the probability of obtainingthe observed data under the assumption of no realeffect, (b) as an “observed” type-I error rate, (c) as thefalse discovery rate, i.e. the probability that a significantfinding is “false positive”, and (d) as the (posterior)probability of the null hypothesis [6].The latter misinterpretation has given rise to interest-

ing work on the connection between P values and(posterior) probabilities of the null hypothesis. Within aBayesian framework, the posterior probability is a func-tion of the prior probability and the so-called Bayesfactor, which summarizes the evidence against the nullhypothesis.

Several attempts have been made to transformP values to lower bounds on the Bayes factor and theresulting posterior probability of the null hypothesis[7-11]. In this context Bayes factors are usually orientedas P values such that smaller values provide strongerevidence against the null hypothesis. These techniquescalibrate P values such that an interpretation as mini-mum Bayes factor or minimum posterior probability isjustified. Although the different approaches do notresult in identical calibration scales, a universal findingis that the evidence against a simple null hypothesis isby far not as strong as the P value might suggest.However, the acceptance of calibrated P values in clin-

ical fields is low. Minimum Bayes factors have theadvantage that they do not depend on the prior prob-ability of the null hypothesis [9], but their interpretationrequires an intuitive understanding of odds, similar tolikelihood ratios in diagnostic studies [12]. Clinicians,however, prefer to think in terms of probabilities. Thecalculation of the minimum posterior probability, on theother hand, requires to decide on a prior probability ofthe null hypothesis. Fixing a prior probability may bedifficult for the clinician, who would perhaps prefer toinvestigate - for a given P value - the dependence of the

Correspondence: [email protected] Unit, Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University ofZurich, Hirschengraben 84, 8001 Zurich, Switzerland

Held BMC Medical Research Methodology 2010, 10:21http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/10/21

© 2010 Held; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative CommonsAttribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction inany medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

BFfor

otherwise.

§©̈

·¹̧

� �§©̈

·¹̧

!

®°

¯°

�Q Q QQ

xx

x/

exp2

21

Here, x is the value of the c2-test statistic which hasgiven rise to the observed P value. It can be easilyshown that BF decreases with increasing degrees-of-free-dom. Perhaps more interestingly, BF is equal to the BSlower bound for normal priors for ν = 1, equals the SBBlower bound for ν = 2, and is equal to the ELS lowerbound for ν ® ∞. This illustrates that the range of

lower bounds on the posterior probability given inTable 1 reflects a large variety of different tests andscenarios.

A nomogram for P valuesThe apparent complexity of the formulae presented inthe previous section may be one of the reasons why theproposed calibration of P values has not entered routinescientific research. I therefore suggest to adapt a graphi-cal device, originally developed for diagnostic tests [13],to the setting outlined above. The original Fagan nomo-gram allows to visually determine the post-test

Figure 1 A nomogram for P values. The prior probability for the null hypothesis is located on the first axis, the observed P value on thesecond axis, and the minimum posterior probability on the third axis.

Held BMC Medical Research Methodology 2010, 10:21http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/10/21

Page 3 of 7

P-value (breast cancer and fat consumption)

• Women’s Health Ini$a$ve Study (WHI), JAMA

“A low fat dietary pa=ern did not result in a sta-s-cally significant reduc-on in invasive breast cancer risk”

Data:

Invasive breast cancer HR 0.91 (0.83 – 1.01), P = 0.07

Breast cancer mortality HR 0.77 (0.48 – 1.22)

Letrozole and Tamoxifene for breast cancer

n engl j med 353;26 www.nejm.org december 29, 2005 2747

The new england journal of medicineestablished in 1812 december 29, 2005 vol. 353 no. 26

A Comparison of Letrozole and Tamoxifen in Postmenopausal Women with Early Breast Cancer

The Breast International Group (BIG) 1-98 Collaborative Group*

abstract

The Writing Committee (Beat Thürli-mann, M.D., chair, Aparna Keshaviah, Sc.M., Alan S. Coates, M.D., Henning Mouridsen, M.D., Louis Mauriac, M.D., John F. Forbes, F.R.A.C.S., Robert Pari-daens, M.D., Ph.D., Monica Castiglione-Gertsch, M.D., Richard D. Gelber, Ph.D., Manuela Rabaglio, M.D., Ian Smith, M.D., Andrew Wardly, M.D., Karen N. Price, B.S., and Aron Goldhirsch, M.D.) takes responsibility for the content of this arti-cle. The affiliations of the Writing Com-mittee members are listed in the Ap-pendix. Address reprint requests to the International Breast Cancer Study Group Coordinating Center, Effingerstrasse 56, 3088 Bern, Switzerland, or at [email protected].

*Members of the BIG 1-98 Collaborative Group are listed in Supplementary Ap-pendix 1, available with the full text of this article at www.nejm.org.

N Engl J Med 2005;353:2747-57.Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society.

backgroundThe aromatase inhibitor letrozole is a more effective treatment for metastatic breast cancer and more effective in the neoadjuvant setting than tamoxifen. We compared letrozole with tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for steroid-hormone-receptor–posi-tive breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

methodsThe Breast International Group (BIG) 1-98 study is a randomized, phase 3, double-blind trial that compared five years of treatment with various adjuvant endocrine therapy regimens in postmenopausal women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer: letrozole, letrozole followed by tamoxifen, tamoxifen, and tamoxifen followed by letrozole. This analysis compares the two groups assigned to receive letrozole initially with the two groups assigned to receive tamoxifen initially; events and fol-low-up in the sequential-treatment groups were included up to the time that treat-ments were switched.

resultsA total of 8010 women with data that could be assessed were enrolled, 4003 in the letrozole group and 4007 in the tamoxifen group. After a median follow-up of 25.8 months, 351 events had occurred in the letrozole group and 428 events in the tamox-ifen group, with five-year disease-free survival estimates of 84.0 percent and 81.4 percent, respectively. As compared with tamoxifen, letrozole significantly reduced the risk of an event ending a period of disease-free survival (hazard ratio, 0.81; 95 percent confidence interval, 0.70 to 0.93; P = 0.003), especially the risk of distant re-currence (hazard ratio, 0.73; 95 percent confidence interval, 0.60 to 0.88; P = 0.001). Thromboembolism, endometrial cancer, and vaginal bleeding were more common in the tamoxifen group. Women given letrozole had a higher incidence of skeletal and cardiac events and of hypercholesterolemia.

conclusionsIn postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive breast cancer, adjuvant treat-ment with letrozole, as compared with tamoxifen, reduced the risk of recurrent dis-ease, especially at distant sites. (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00004205.)

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Downloaded from www.nejm.org at NovartisLibrary on December 31, 2005 .

T h e n e w e n g l a n d j o u r n a l o f m e d i c i n e

n engl j med 353;26 www.nejm.org december 29, 20052754

need for new approaches to reduce this risk, which is associated with estrogen deprivation. The ab-sence of an increase in the median percent change from baseline in cholesterol levels during treat-ment with letrozole is similar to data from the

MA.17 trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group, which compared letrozole with a placebo.26 The low-grade hyper-cholesterolemia we found in patients given letro-zole, but not tamoxifen, was also reported in a

8010

5143

2867

4957

2973

4587

3311

5055

1631

1154

4548

3452

5744

2258

2024

5986

8010

8010

8010

8010

8010

351

187

164

157

190

140

205

179

89

70

128

223

227

124

92

259

166

323

296

228

184

428

230

198

173

251

147

274

208

107

92

155

271

273

155

126

302

192

383

369

310

249

0.003

0.04

0.02

0.28

0.004

0.75

<0.001

0.09

0.18

0.04

0.20

0.003

0.03

0.03

0.01

0.06

0.16

0.02

0.002

<0.001

0.001

Primary end point

Disease-free survival

Age

<65 yr

≥65 yr

Tumor size

≤2 cm

>2 cm

Nodal status

Negative (including Nx)

Positive

ER and PgR status

ER- and PgR-positive

ER-positive and PgR-negative

ER-positive and PgR status

missing or unknown

Local therapy

Breast-conserving surgery

Mastectomy

Radiotherapy

Yes

No

Chemotherapy

Yes

No

Secondary end points

Overall survival

Systemic disease–free survival

Additional end points

Disease-free survival excluding

2nd nonbreast cancers

Time to recurrence

Time to distant recurrence

No. ofPatients

Hazard Ratio(95% CI)

No. of EventsVariable P ValueTamoxifen

0.81 (0.70–0.93)

0.86 (0.70–1.06)

0.83 (0.72–0.97)

0.79 (0.68–0.92)

0.72 (0.61–0.86)

0.73 (0.60–0.88)

0.82 (0.67–0.99)

0.79 (0.64–0.97)

0.89 (0.72–1.10)

0.76 (0.63–0.92)

0.96 (0.76–1.21)

0.71 (0.59–0.85)

0.84 (0.69–1.03)

0.83 (0.62–1.10)

0.72 (0.53–0.98)

0.86 (0.68–1.08)

0.76 (0.64–0.91)

0.82 (0.69–0.98)

0.77 (0.61–0.98)

0.70 (0.54–0.92)

0.85 (0.72–1.00)

Letrozole

0.50 0.75 1.00 1.25

TamoxifenBetter

LetrozoleBetter

Hazard Ratio

Figure 3. Cox Proportional-Hazards Model Results of Primary, Secondary, and Additional End Points.

The results were adjusted for randomization option and chemotherapy stratum. The size of the boxes is inversely proportional to the standard error of the hazard ratio. The dashed vertical line is placed at 0.81, the hazard-ratio estimate for the overall analysis of the pri-mary study end point. Patients with missing data or unknown status were not included in the subgroup analyses. CI denotes confidence interval, ER estrogen receptor, and PgR progesterone receptor.

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Downloaded from www.nejm.org at NovartisLibrary on December 31, 2005 .

BFfor

otherwise.

§©̈

·¹̧

� �§©̈

·¹̧

!

®°

¯°

�Q Q QQ

xx

x/

exp2

21

Here, x is the value of the c2-test statistic which hasgiven rise to the observed P value. It can be easilyshown that BF decreases with increasing degrees-of-free-dom. Perhaps more interestingly, BF is equal to the BSlower bound for normal priors for ν = 1, equals the SBBlower bound for ν = 2, and is equal to the ELS lowerbound for ν ® ∞. This illustrates that the range of

lower bounds on the posterior probability given inTable 1 reflects a large variety of different tests andscenarios.

A nomogram for P valuesThe apparent complexity of the formulae presented inthe previous section may be one of the reasons why theproposed calibration of P values has not entered routinescientific research. I therefore suggest to adapt a graphi-cal device, originally developed for diagnostic tests [13],to the setting outlined above. The original Fagan nomo-gram allows to visually determine the post-test

Figure 1 A nomogram for P values. The prior probability for the null hypothesis is located on the first axis, the observed P value on thesecond axis, and the minimum posterior probability on the third axis.

Held BMC Medical Research Methodology 2010, 10:21http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/10/21

Page 3 of 7

Bayes Factor

• P-‐value – commonly misunderstood

– affected by sample size and mul$plicity of tests

• Bayes Factor: an objec1ve metric of evidence – "hot" topic of research in gene$cs and clinical medicine

“Half of what doctors know is wrong. Unfortunately we don’t know which half.”

Quoted from the Dean of Yale Medical School,

in “Medicine and Its Myths”,

New York Times Magazine, 16/3/2003