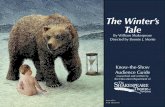

The Winter's Tale - Education Pack 2011-12propeller.org.uk/media/files/The Winter's Tale - Education...

Transcript of The Winter's Tale - Education Pack 2011-12propeller.org.uk/media/files/The Winter's Tale - Education...

EEdduuccaattiioonn PPaacckk WWrriitttteenn aanndd ccoommppiilleedd bbyy WWiillll WWoolllleenn

PPrrooppeelllleerr TThheeaattrree CCoommppaannyy LLttdd

HHiigghhffiieelldd ·· MMaannoorr BBaarrnnss ·· SSnnoowwsshhiillll ·· BBrrooaaddwwaayy ·· WWoorrccss WWRR1122 77JJRR

TTeell::0011338866 885533 220066 wwwwww..pprrooppeelllleerr..oorrgg..uukk

2

Contents Page

About Propeller p. 3 To Teachers p. 4 Cast and Creatives p. 5 Synopsis p. 6 William Shakespeare pp. 7-8 Cue Script Exercise p. 9 Cue Scripts pp. 10-15 Source of the Story p. 16 Doubling decisions p. 17 Interview with Robert Hands -actor playing Leontes p. 18 Interview with Richard Dempsey -actor playing Hermione/Dorcas p. 21

Roger Warren on ‘Time and Truth in The Winter’s Tale’ p.23 The Trial of Leontes p.26

3

About Propeller Propeller is an all-male Shakespeare company which seeks to find a more engaging way of expressing Shakespeare and to more completely explore the relationship between text and performance. Mixing a rigorous approach to the text with a modern physical aesthetic, they have been influenced by mask work, animation and classic and modern film and music from all ages. Productions are directed by Edward Hall and designed by Michael Pavelka. Lighting is designed by Ben Ormerod. Propeller has toured internationally to Australia, China, Spain, Mexico, The Philippines, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Cyprus, Ireland, Tokyo, Gdansk, Germany, Italy, Malta, Hong Kong and the U.S.A.

As our times have changed, so our responses to Shakespeare’s work have changed too and I believe we have become an ensemble in the true sense of the word: We break and reform our relationships using the spirit of the particular play we are working on. We have grown together, eaten together, argued and loved together. We have toured

all over the world from Huddersfield to Bangladesh. We have played in National theatres, ancient amphitheatres, farmyards and globe theatres. We have been applauded, shot at and challenged by different audiences wherever we have gone. We want to rediscover Shakespeare simply by doing the plays as we believe they should be done: with great clarity, speed and full of as much imagination in the staging as possible. We don’t want to make the plays ‘accessible’, as this implies that they need ‘dumbing down’ in order to be understood, which they don’t. We want to continue to take our work to as many different kinds of audiences as possible and so to grow as artists and people. We are hungry for more opportunity to explore the richness of Shakespeare’s plays and if we keep doing this with rigour and invention, then I believe the company, and I hope our audiences too, will continue to grow. Edward Hall, Artistic Director.

Edward Hall

4

To Teachers This pack has been designed to complement your class’s visit to see Propeller’s 2012 production of The Winter’s Tale, on national and international tour. Most of the pack is aimed at A-level and GSCE students of Drama and English Literature in the UK, but some of the sections, and suggestions for classroom activities, may be of use to teachers teaching pupils at Key Stages 2, 3 & 4, while students studying in other countries and those in higher education may find much of interest in these pages. While there are some images, the pack has been deliberately kept simple from a graphic point of view so that most pages can easily be photocopied for use in the classroom. Your feedback is most welcome. You can make any comments on the pack on the Propeller website forum. www.propeller.org.uk Workshops to accompany the production are also available. I hope you find the pack useful. Will Wollen Education Consultant Propeller

Ben Allen (Mamillius) and the company of Propeller’s The Winter’s Tale. Photo: Manuel Harlan

5

Cast and Creatives

Directed by EDWARD HALL Text adaptation by EDWARD HALL & ROGER WARREN Designed by MICHAEL PAVELKA Lighting by BEN ORMEROD Music by PROPELLER Sound by DAVID GREGORY

Cast Ben Allen Mamillius / Perdita Nicholas Asbury Polixenes Tony Bell Autolycus / Officer, lord of Sicilia Dugald Bruce-Lockart Antigonus Gunnar Cauthery Emilia / Mopsa / First lord of Sicilia Karl Davies Young Shepherd / Cleomenes Richard Dempsey Hermione / Dorcas John Dougall Dion / Old Shepherd Robert Hands Leontes Finn Hanlon Florizel / Mariner Vince Leigh Paulina Chris Myles Camillo Gary Shelford 1st Lady / Hermione’s Attendant Dominic Thorburn First lord of Sicilia

Tony Bell (Autolycus) John Dougall (Old Shepherd) Ben Allen (Perdita)

Photos: M

anuel Harlan

6

Synopsis

Leontes, the King of Sicilia, asks his dearest friend from childhood, Polixenes, the King of Bohemia, to extend his visit. Polixenes has not been home to his wife and young son for more than nine months but Leontes’ wife, Hermione, who is heavily pregnant, finally convinces her husband's friend to stay a bit longer. As they talk apart, Leontes thinks that he observes Hermione’s behaviour becoming too intimate with his friend, for as soon as they leave his sight he is imagining them "leaning cheek to cheek, meeting noses, kissing with inside lip." He orders one of his courtiers, Camillo, to stand as cupbearer to Polixenes and poison him as soon as he can. Camillo cannot believe that Hermione is unfaithful and informs Polixenes of the plot. He escapes with Polixenes to Bohemia.

Leontes, discovering that they have fled, now believes that Camillo knew of the imagined affair and was plotting against him with Polixenes. He accuses Hermione of adultery, takes Mamillius, their son, from her and throws her in jail. He sends Cleomenes and Dion to Apollo’s Oracle at Delphi, for an answer to his charges. While Hermione is in jail her daughter is born, and Paulina, her friend, takes the baby girl to Leontes in the hope that the sight of his infant daughter will soften his heart. By this time Leontes has decided that Polixenes, Hermione and Camillo were all conspiring to murder him. He orders Antigonus, Paulina’s husband to throw the baby into the fire, but Antigonus will not. Leontes relents but commands that the baby be abandoned in a desolate place.

Leontes puts Hermione on trial, and the Oracle at Delphi confirms that she is chaste, the child is not a bastard, Camillo is honest and Leontes is a tyrant. The oracle also says that “The king shall live without an heir if that which is lost be not found”. Leontes refuses the truth and immediately the news arrives that Mamillius, pining for his mother, has died. Hermione faints, Leontes realizes his terrible errors, and Paulina enters with the horrible news that Hermione, too, has died.

Antigonus arrives on the sea coast of Bohemia having dreamt that Hermione is dead and has been found guilty. He leaves the baby, named Perdita, to her fate. He is killed by a bear and the baby is found by an Old Shepherd and his son, who decide to raise her as their own.

With the help of Time, we skip forward 16 years. Perdita is now a young lady, in love with the young man Doricles. He is actually Florizel, son of Bohemia's King Polixenes. Perdita is the queen of the local sheep-shearing festival and entertains everyone with her winning personality, good looks and natural charm. We meet a whole new cast of characters, including the rogue, vagabond and pickpocket Autolycus. Polixenes and Camillo are looking for Florizel. They finally catch up with him at the festival and observe his love of Perdita. Florizel asks the Old Shepherd to bless his betrothal to Perdita. Polixenes, whose permission has not been asked, removes his disguise and declares that the marriage will not happen and that the Old Shepherd will be executed for allowing a prince to court his daughter. In addition, Perdita will be "scratched with briers" and Florizel disinherited if he ever sees her again.

We return to Sicilia, where Leontes is still mourning the death of his family. Paulina gets him to agree never to marry again unless she gives the go ahead. Florizel and Perdita show up pretending to be on a diplomatic mission from Bohemia and both charm Leontes. Leontes vows to help the young couple and they all go off, to reunite with Polixenes and Camillo, after all these years. We then hear from three lords that the lovely young shepherdess is actually the long-lost heir of Sicilia, and that Paulina has revealed an amazing statue of the long-dead Hermione. They all go to see this wonder and Paulina reveals the living Hermione. Her reward is to be given Camillo as a husband.

7

William Shakespeare The person we call William Shakespeare wrote some 37 plays, as well as sonnets and full-length poems; but very little is actually known about him. That there was someone called William Shakespeare is certain, and what we know about his life comes from registrar records, court records, wills, marriage certificates and his tombstone. There are also contemporary anecdotes and criticisms made by his rivals which speak of the famous playwright and suggest that he was indeed a playwright, poet and an actor.

The earliest record we have of his life is of his baptism, which took place on Wednesday 26th April 1564. Traditionally it is supposed that he was, as was common practice, baptised three days after his birth, making his birthday the 23rd of April 1564 – St George’s Day. There is, however, no proof of this at all.

William's father was a John Shakespeare, a local businessman who was involved in tanning and leatherwork. John also dealt in grain and sometimes was described as a glover by trade. John was also a prominent man in Stratford. By 1560, he was one of the fourteen burgesses who made up the town council. William's mother was Mary Arden who married John Shakespeare in 1557. They had eight children, of whom William was the third. It is assumed that William grew up with them in Stratford, one hundred miles from London.

Very little is known about Shakespeare’s education. We know that the King’s New Grammar School taught boys basic reading and writing. We assume William attended this school since it existed to educate the sons of Stratford but we have no definite proof. There is also no evidence to suggest that William attended university.

On 28th November 1582 an eighteen-year-old William married the twenty-six-year-old Anne Hathaway. Seven months later, they had their first daughter, Susanna. Anne never left Stratford, living there her entire life.

8

Baptism records reveal that twins Hamnet and Judith were born in February 1592. Hamnet, the only son died in 1596, just eleven years old.

At some point, Shakespeare joined the Burbage company in London as an actor, and was their principal writer. He wrote for them at the Theatre in Shoreditch, and by 1594 he was a sharer, or shareholder in the company. It was through being a sharer in the profits of the company that William made his money and in 1597 he was able to purchase a large house in Stratford.

The company moved to the newly-built Globe Theatre in 1599. It was for this theatre that Shakespeare wrote many of his greatest plays, including, in 1611, The Winter’s Tale.

In 1613, the Globe Theatre caught fire during a performance of Henry VIII, one of Shakespeare’s last plays, written with John Fletcher, and William retired to Stratford where he died in 1616, on 23rd April.

Propeller’s 2005 production of The Winter’s Tale at The Watermill Theatre Photo: Tristram Kenton

9

Cue Script Exercise

When Shakespeare wrote The Winter’s Tale in 1611, the actors would not have been given the whole script. Instead, they would have been given their part (or ‘role’, literally a ‘roll’ on which their part was written). Printing or copying the whole play for each actor would have been far too expensive and time-consuming, and a playwright would not have wanted a disloyal actor to be able to give the whole play to a rival company. As well as their lines, the actors would have been given their cues – just three or four words from the person who spoke just before them. Thus they would have their cues to enter, to speak and to exit. They would not be told how long the gap was between one of their speeches and the next. They simply had to listen for their cue and be ready to speak, trusting, of course that their fellow actors had learned their lines properly – if their cue wasn’t given then they wouldn’t speak! Rehearsals were short – at busy times they would only have three or four mornings to rehearse a new play – so learning the script accurately and very quickly was crucial to the actor’s craft. ■ The following pages are cue scripts (neatly word-processed!) for a scene from The Winter’s Tale. You will need to cast Leontes, Hermione, Paulina, Officer, Servant and photocopy as many Lords’ scripts as you need (you’ll need at least two). Once you have tried to run the scene, come back to these notes. ■ What happened in your scene when Hermione fainted? How did the other characters react? ■ What clues are there in the script that tell you how to speak your lines? How much does listening become important? ■ To whom are you speaking on each line? How do you know? Why do you think Shakespeare is helping you?

10

Cue Script Cue Script Cue Script Cue Script –––– LeontesLeontesLeontesLeontes

Break up the seals, and read. (Cue) …Praised! Hast thou read truth? …here set down. There is no truth at all i’th’ oracle. The sessions shall proceed. This is mere falsehood. …the King, the King! What is the business? …Queen’s speed, is gone. How, ‘gone’? …Is dead. Apollo’s angry, and the heavens themselves Do strike at my injustice. How now there? …death is doing. Take her hence. Her heart is but o’ercharged, she will recover. I have too much believed mine own suspicion. Beseech you, tenderly apply to her Some remedies for life. Apollo, pardon My profaneness ’gainst thine oracle.

Leontes is expecting a different

verdict in this scene. How has he

changed from the beginning to the

end? How are you behaving to let the

audience know that you have

changed? At which points in the

scene does the situation change for

you?

Make sure that you are always

speaking to someone (even if it is the

god Apollo). Sometimes the person

you are speaking to might have to

change in the middle of a line.

11

Cue script Cue script Cue script Cue script –––– OfficerOfficerOfficerOfficer …(Cue) the seals, and read. Hermione is chaste, Polixenes blameless, Camillo a true subject, Leontes a jealous tyrant, his innocent babe truly begotten, and the King shall live without an heir if that which is lost be not found. …Hast thou read truth? Ay, my lord, even so as it is here set down.

You are holding the verdict from the oracle and it is

your duty to deliver it. A great deal depends on what

you say. How is the officer feeling as he breaks the

seals?

Is the occasion formal or relaxed, and how does that

affect the way you give your lines.

After you have spoken the scene continues. What is

the officer doing? What does he hear and see, and

how does it affect him?

12

Cue Script Cue Script Cue Script Cue Script –––– HermioneHermioneHermioneHermione …(Cue) be the great Apollo! Praised! …Is dead. [Faints]

Hermione has been let out of her cell for this

occasion. She has now been accused publicly of

adultery and high treason. She, of course, is

innocent. How does she feel mentally and

physically?

What are her biggest fears?

How does she feel when she hears the verdict of the

oracle?

Why does she faint?

13

Cue Script Cue Script Cue Script Cue Script –––– ServantServantServantServant …(Cue) This is mere falsehood. [Enter] My lord the King, the King! What is the business? O sir, I shall be hated to report it. The prince your son, with mere conceit and fear Of the Queen’s speed, is gone. How, ‘gone’? Is dead.

How does the news the servant has to tell affect

his/her entry onto the stage?

Why does the servant say ‘the King’ twice?

Why doesn’t the servant say ‘dead’ the first time?

14

Cue Script Cue Script Cue Script Cue Script –––– PaulinaPaulinaPaulinaPaulina …(Cue) How now there? This news is mortal to the Queen. Look down And see what death is doing. …remedies for life. [Exit]

Paulina spends the first half of this extract saying

nothing. What is she doing? How is she feeling? How

do those feelings change throughout the scene?

What is her attitude towards Leontes?

What is she doing as she exits?

15

Cue Script Cue Script Cue Script Cue Script –––– LordsLordsLordsLords …(Cue) be not found. Now blessèd be the great Apollo! …remedies for life. [Exit]

You have been called to witness the verdict of the oracle.

Have any of you brought Hermione here from her cell?

For whom do you feel the most sympathy?

What is your reaction to the servant’s news?

What must you be doing when you exit?

16

The Winter’s Tale – Source of the Story

The main source of The Winter's Tale is from Robert Greene's popular romance Pandosto: The Triumph of Time, published in 1588. Shakespeare changed all the characters' names and created two new ones, the Clown/Young Shepherd and Autolycus. He also swaps Sicilia for Bohemia. Pandosto, King of Bohemia, becomes Leontes, King of Sicilia. Bellaria, Queen of Bohemia, becomes Hermione, Queen of Sicilia. Egistus, King of Sicilia corresponds to Polixenes, King of Bohemia. Garrinter corresponds to Mamillius. Fawnia is Perdita. Dorastus becomes Florizel, Polixenes’ son. Franion turns into Camillo. Porrus, an old shepherd, corresponds to Shakespeare’s Old Shepherd

The plots of the plays are remarkably similar but in Greene’s version Bellaria (Hermione) does actually die after her trial and Pandosto commits suicide at the end of the story. Greene has Bellaria ask that the oracle be consulted but in The Winter’s Tale this is Leontes' idea.

Robert Greene 1558 - 1592 one of the most popular English prose writers of the later 16th century and Shakespeare's most successful predecessor in blank-verse romantic comedy. Greene gives us our first printed reference to Shakespeare, and clearly hadn’t taken to the new kid on the block. Shakespeare is described as “an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers heart wrapt in a Players hide, supposes he is as well able to bumbast out a blanke verse as the best of you.”

The stories that Shakespeare uses in all 37 odd of his plays are almost entirely drawn from stories that already existed. He and his contemporaries were constantly ‘stealing’ and retelling stories to produce new works. The economic pressure on companies to churn out new works would have been immense; it wouldn’t even have been financially viable to run a play like The Winter’s Tale for two weeks at a London playhouse. In order to keep the audiences (who, of course had no television or cinema) coming in, theatres had to promise a stream of new plays to be heard. Over a two-month period a company might rotate a dozen plays, playing the most popular one only ten times. Compare that with many West End theatres in London today who have been showing the same production for years.

17

Doubling decisions

When Shakespeare was writing plays he was always writing with a specific company of about sixteen actors in mind. So, when he wrote a story like The Winter’s Tale, with more than twenty named characters and directions for further lords, servants, and shepherds, he would have been expecting some of the actors to be playing more than one part.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth century there was a fashion for large casts, so it was likely that each actor would play one part, and there would be a number of non-speaking actors, paid to be servants or lords to make up the picture of a scene.

Today, fashion and economic restraints means that it is common to play Shakespeare with fewer actors than characters (Propeller’s production has only fourteen actors), so actors will often find themselves ‘doubling’. Every production can make different choices about which characters are played by the same actor - with interesting results, forcing the audience to draw comparisons between the two characters.

In Propeller’s production the following parts are doubled:

Mamillius (Leontes’ son) and Perdita (Leontes’ daughter) Hermione and Dorcas (shepherdess) Emilia and Mopsa

♦ Choose one of these pairs and discuss what effect the doubling has on the production. Or consider the effect of the pairings below:

In 1969, Judi Dench famously played both Hermione and Perdita for the RSC.

In Théâtre de Complicité’s 1992 production, Leontes and the Clown/Young Shepherd were both played by Simon McBurney, and Katherine Hunter played Paulina, Mamillius and the Old Shepherd!

18

Interview with Robert Hands – actor playing Leontes What’s going on for Leontes at the beginning of the play? I’d say he was a confident ‘alpha male’, happy with his lot. He’s having a fantastic party; he wants his mate to stay longer; he loves his wife; he loves his son. He wants the party to carry on. What happens in that famous moment in the first act when it all changes for him? I think he clocks his wife succeeding where he’s failed and it takes hold of him. It’s like it possesses him, but it doesn’t do it all in one go. From nowhere the thought just drops into his head. I don’t even think he realises he’s being jealous because he’s never had to be jealous before. It’s like a sort of cancer; it just grows and grows and grows, and all the time he’s trying to fight it. He decides, “I’ll talk to my son”, and then it comes back again and there’s a sense that he can’t believe it and doesn’t want to believe it until finally they leave and he can’t deny it any longer. And when his son dies? That’s the bucket of cold water in the face moment, the smack, when all of a sudden he comes round and sees what he’s done. It needs something that momentous to make him see, because he’s sort of become hysterical with it. How would you describe him as a father before this all happens? He’s a good father, devoted to his son. He doesn’t describe his relationship with his son, but his friend Polixenes describes his relationship with his son and Leontes agrees with him, saying that’s exactly how he feels. They’re very close. As an actor do you enjoy the break of being a sheep in the second half? Between you and me [!], I’ve only performed it four times at this stage so at the end of Sicilia at the moment I’m thinking, “I don’t want to be a sheep!”, but I suspect as it goes on I’ll start enjoying it more and more. All I’m thinking about at the moment is the Act Five that’s coming up. Of course we’re doing this alongside Henry V so that’s hard enough – you have to get your head into a different place. You’ve had a break from Propeller and come back to the company. How’s it changed?

Robert Hands as Leontes

19

Yes, I did Rose Rage and then A Midsummer Night’s Dream [2004] then I came back in 2010 to do Comedy of Errors and Richard III. The company has got better. On every level it’s got better. It has funding – which means that the production values are higher. We have a hands-on producer – which we didn’t have before. It

used to be completely on a wing and a prayer; someone would phone someone who’d phone someone and miraculously we’d all turn up at rehearsals. But the whole thing is thanks to Jill Fraser [Artistic Director of The Watermill Theatre from 1981 until her death in 2006] who had a theatre building to run at the same time. But it was entirely thanks to her loyalty and ‘balls’ that the company got anywhere at all. But it was an odd sock arrangement and now it seems so much more looked after. Maybe it’s because I’m getting older, but the younger actors seem so much better now – really committed and really talented – there was an awful lot of mucking about before that doesn’t go on now; there’s a complete focus in the rehearsal room. And Ed [Edward Hall] has honed his voice. He’s really developed as a director, more confident – and so he should be too, he’s a world-famous director now! It used to feel more like a rugby club, but now it’s a really shithot theatre company. What’s Propeller got that other theatre companies haven’t? It’s truly an ensemble company. There is no segregation, no sense of hierarchy. Ed’s very happy to take comments from the floor. Sometimes he leaves the rehearsal room and knows that we’ll sort something out better than if he did it, for example he let the actors just get on with creating a lot of the set pieces in Bohemia. That feels very Propeller – just being left to your own devices. But for other bits it’s completely different and Ed’s absolutely hands-on. Can you describe the process of putting together the music? That’s a perfect example of where Ed just backs away and lets the actors get on with it. He’ll listen to it and say “that’s great” or “that needs changing”, but actually he’ll just give it to the room saying “what I want here is a piece of music that does this”. Usually there’s someone in the company who’s brilliant at it. Ed will often leave an hour early at the end of the day and we’ll just do music without him. I’m not a main music person though. Hopeless! I can sing quite competently, though. Back to Leontes. What’s changed for him? I think he’s completely broken by his experience. He’s lost two children and his wife. He’s lost his best friend. I still get very emotional when I talk about

Bohemia. Photo by Manuel Harlan

20

it. He’s living with remorse on a scale that most people wouldn’t have to, but then, of course, he went much further than most people ever would. I’ve elected to play him in a wheelchair; his body has just responded to those emotions by just giving up, it doesn’t have any strength in it anymore. There’s nothing actually ‘wrong’ with him, he hasn’t ‘got’ something, I just don’t think he has the will to carry his body. His life has become about atoning for those sins, visiting the chapel every day and contemplating his wife’s death. She comes back, of course. But it’s not really a happy ending. No. What happens the next day? I don’t know. Because the bottom line is that he’s killed their son. It doesn’t matter how much you atone, it’s happened. I like to think – of course it’s pure conjecture – that they reach some sort of peace between them. Do you have a favourite moment or a favourite line? Yes. The first moment when he sees Florizel and he says “Your mother was most true to wedlock, prince; For she did print your royal father off, Conceiving you...” I just think that the situation is so beautiful. He’s had such a terrible fifteen years. There’s something so beautiful about that – seeing his friend’s face in his friend’s son. I don’t know why but it really touches me. That notion’s crucial to the play: that redemption comes through the next generation. Is there anything outside the text that inspired you? A friend of mine is a psychiatrist and I explained to him what Leontes does. He said that it is actually a phenomenon called ‘morbid jealousy’, or sometimes (mistakenly) the ‘Othello complex’. Othello’s situation is actually completely different because he doesn’t just become jealous but is fed ‘poison’. But with this condition come a whole set of characteristics that fit with the script! It tends to happen to very high-achieving, confident alpha males, who drink very heavily. And the drink is a crucial part of that process. Which is why you’ll see that my Leontes always has a glass in his hand!

21

Interview with Richard Dempsey -actor playing Hermione/Dorcas How would you describe Hermione? At the beginning of the play she’s in a very contented family and marital state. She’s a very confident, strong woman who’s completely in love with her husband and not expecting any of the awfulness that’s about to come. She’s in a very happy and powerful place. How does she feel about being with lots of men? Well yes, I think she’s very comfortable in a male world, and because she’s a great Russian king’s daughter she’s used to being around strong male people and is completely comfortable with that and enjoys holding her own in that environment. For an audience it can be quite shocking when Leontes turns on her – what do you reckon attracts her to Leontes in the first place? Well of course when he attacks her it’s not the Leontes she knows; the Leontes she knows is one with whom she has a completely equal relationship, but whom she respects as a husband and as a king. There’s obviously a slight difference of status, but not one that has to be played up to in any way. I think she feels completely secure in her relationship with him so it comes as a complete shock when he comes in with this tirade of abuse and anger, all of which is based on nothing. So I think her attitude towards it at the beginning is “there’s something wrong with him” – it’s actually concern initially. So she doesn’t fancy Polixenes just a little bit?! Well I don’t know! Maybe she does a little bit; she’s confident sexually and aware of the power that she has as a woman, and I think she uses that. All of the stuff in the first scene is very public, and I think there is some flirtation, but certainly not in a sexual way and I don’t think it would have crossed her mind – she’s so committed to her husband. As she says in the trial she loves Polixenes as a friend; she loves him because he’s her husband’s friend. What do you think we gain by having a man playing Hermione?

Richard Dempsey as Hermione (top) and Dorcas (below). Photos: Manuel Harlen

22

I don’t think it really matters if that’s a man or woman doing that. It’s the part. I’ve thought a lot about that lady in Iran, the one that got accused of adultery and had to defend herself in court and was going to be stoned to death [Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani]. That woman was just an extraordinary example of strength and power and self-belief and eventually won her case. I studied cases like that and didn’t really think about it as a man playing a woman; it’s just such a fantastic part. There’s a big gap where we don’t see Hermione and in between you play Dorcas. That must be real fun after the trial? I have to say it’s hysterical - we do a bit of Beyoncé in the second half, which I love! It’s really nice to have that – not just for the audience but for the actors as well – to have the balance between the two worlds. Sicilia is very tragic and sad, and to have that balance of Bohemia and comedy is very important for the play I think. I love playing Dorcas. She’s a right old slapper! Is there any process for you that happens between the ‘two’ Hermiones, before we see her again? What happens to her? Well it’s debatable really. It depends what your take is on the play. Vinnie [Vince Leigh], who plays Paulina, and I decided that when Hermione appears at the end of the play they hadn’t actually decided whether she would come to life or not, and it’s actually Paulina who makes the decision. She just takes a chance with Perdita being there and Leontes being in such a changed emotional state. And presumably she’s lived in a completely female world all that time? We’ve decided that it’s just been exclusively her and Paulina and nobody else has been allowed to see her apart from her maid and servants. A long time has passed so she’s had a long time to reflect and meditate on what’s happened. I just try to ficus on the fact that she’s a compassionate woman with a strong belief in honour and faith. It’s not a ‘Christian’ world, but she does have a very strong belief and faith that all will be well in the end, despite the death of her son. She just lives and breathes compassion. What’s going to happen at the end of the play? Is there a happy ending? It’s interesting, isn’t it? I suspect she resolves things with her husband, because of her absolute underlying dedication to honour, but I’m not sure about her relationship with Polixenes – I suspect she’d find that very hard to resolve, because had he not left with Camillo things could have been very different. That ‘triangle’ would be slightly different after the play finishes. Do you have a favourite line or favourite moment? I love the trial – it’s just an absolute gift. My favourite line in the trial is: “ life,/ I prize it not a straw, but for mine honour,/ Which I would free, if I shall be condemn'd/ Upon surmises, all proofs sleeping else/ But what your jealousies awake...”

At time of writing Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani is still at risk of execution. To email the Head of the Iranian Judiciary to ask that Sakineh is spared execution, and granted a fair trial you can visit www.amnesty.org.uk

23

Roger Warren (Co-Adapter Of Text) on ‘Time And Truth In The Winter’s Tale’

THE WINTER’S TALE is one of a group of plays (Cymbeline and The Tempest are the others) written close together at the end of Shakespeare’s career, probably in 1610–11, with Pericles (1607–8) as a forerunner. They are often called "romances" because they contain unlikely events and interventions by pagan gods; and "winter’s tale" was proverbial for a story to pass a winter’s night: the play itself draws attention to the way in which its events seem ‘like an old tale’, that is, an old wives’ tale. But neither "romance" nor "old tale" should imply that these late plays are escapist fantasies. Myths and folk-tales embody truths which remain relevant because they focus the deepest instincts, joys and fears, of human beings; and these plays contrast the extremes of human experience, setting betrayal, jealousy, and lust for power against integrity, forgiveness, and reconciliation. The language has a corresponding range, from quasi-tragic intensity to lyrical beauty. At the end of his career, Shakespeare was vigorously experimenting with his dramatic technique and renewing it, using the extremes of incident and language to create new imaginative worlds.

The story of The Winter’s Tale derives from Pandosto: The Triumph of Time, a prose narrative by Robert Greene, published some twenty years earlier, in 1588. What attracted Shakespeare to this "old tale"? Surely the topic that it announces uncompromisingly in its opening lines:

Among all the passions wherewith human minds are perplexed, there is none that so galleth with restless despite as that infectious sore of jealousy. … Whoso is pained with this restless torment doubteth all, distrusteth himself, is always frozen with fear and fired with suspicion.

Here is the germ of Shakespeare’s play. Sexual jealousy was an enduring preoccupation for Shakespeare from the slight but virulent case of Claudio in Much Ado About Nothing via Othello to Posthumus in Cymbeline and Leontes in The Winter’s Tale. But whereas in the other plays Shakespeare goes to some lengths to "motivate" the jealousy, that of Leontes is wholly self-conceived. In him, Shakespeare dramatizes the essentially irrational nature of jealousy: his fevered imagination distorts what he sees.

The Winter’s Tale begins in a witty, elegant court society. At its centre is a relaxed and intimate family circle: Leontes, his pregnant wife Hermione, his lifelong friend Polixenes, and his young son Mamillius. All seems right with the world; then, suddenly, in the first of the play’s extreme contrasts, Leontes misinterprets the warmth and affection surrounding him as sexual betrayal. His mind is seized by a destructive disease which burns ferociously through the first half of the play: he treats his pregnant wife in particular with a savagery that borders on sadism, what Hermione rightly calls his ‘immodest hatred’. The root of Leontes’ jealousy is simple: he doesn’t trust his wife. By

24

the end of the trial scene, he appears to have destroyed everything that was once precious to him: his wife, his children, his relationship with his best friend. From these depths he, and the play, must rise.

It starts to do so with another extreme contrast. Abandoning Hermione’s baby daughter Perdita in the wilds of Bohemia, Antigonus is killed by a bear; but the baby is rescued by a kindly, humorous Old Shepherd, who summarizes the technique of the play when he tells his son: ‘thou met’st with things dying, I with things new born.’ During the next sixteen years, Perdita grows up in rural surroundings: and her dawning love for Polixenes’ son Florizel is dramatized during the sheep-shearing celebrations in the play’s second half. But Shakespeare does not idealise this rural world. It is preyed upon by the con-man Autolycus, whose name means ‘the wolf himself’. More seriously, Polixenes destroys the rural festivities when he tries to part Florizel and Perdita with a savagery that echoes Leontes’ earlier violence. Time can heal, but it can also recycle.

The sixteen-year gap in the middle of the play is bridged by Time himself. This might seem merely another device of an "old tale"; but in fact that gap of time has specific dramatic functions. Here again, Shakespeare took a hint from his source. The motto on the title-page of Greene’s Pandosto is ‘Temporis filia veritas’ (‘Truth is the daughter of Time’). Greene’s title-page continues: ‘although by the means of sinister fortune truth may be concealed, yet by time, in spite of fortune, it is most manifestly revealed.’ This truth is two-fold: while new life, in the person of Leontes’ daughter, flourishes in Bohemia, there is a corresponding renewal back in Sicilia, where Leontes himself is undergoing a process of repentance and psychological ‘re-creation’. It is easy to destroy; healing takes much longer. His earlier behaviour was so extreme that a correspondingly extreme period of repentance is needed to expiate what he has done.

This process is supervised by Paulina, who embodies several roles: as she herself tells Leontes, she is ‘your loyal servant, your physician, / Your most obedient counsellor’ — priestess and psychiatrist in one. But compassionate though she is, she has directed his ‘re-creation‘ by keeping his wounds open. When they reappear after the sixteen-year gap, she reminds Leontes that he ‘killed’ Hermione. He replies:

Killed? She I killed? I did so; but thou strik’st me Sorely to say I did. It is as bitter Upon thy tongue as in my thought. Now, good now, Say so but seldom.

He fully admits what he has done, but asks Paulina not to remind him of it too often. He is learning, that is, the moderation he disastrously lacked earlier in the play; and so he is ready for the reunion with his daughter — magically expressed in the language she herself uses in the rural scenes: "Welcome hither, / As is the spring to the earth!" — and for the revelations of the Statue scene where, Paulina reminds him, “It is required / You do awake your

25

faith.”— that trust in his wife that he so signally lacked earlier. But the reunion and reconciliation at the end of The Winter’s Tale are hard-won. The play reminds us of the cost: Leontes’ son Mamillius and Paulina’s husband Antigonus remain dead. Like Greene’s Pandosto, the play may dramatize “the Triumph of Time”, but in doing so it does not sentimentalize the toughness of the “Truth” that Time can reveal. ROGER WARREN

Tony Bell as Autolycus. Photo: Manuel Harlan

26

The Trial of Leontes In Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale it is Hermione who is put on trial, despite the fact that she is not guilty of the crime of which she has been accused. One might argue that it is Leontes’ actions that merit a criminal charge. Imagine THE TRIAL OF LEONTES... Decide what charges Leontes might face. Imagine that it is your job to make the case for the prosecution. Write a speech that puts the argument against Leontes. Draw on evidence from the Propeller production you saw or from Shakespeare’s text. Which characters from the play might you call as witnesses for the prosecution? Draw up some questions that you would like to ask the witnesses.

Choose a character from the play and imagine that you have been called as a witness at the trial of Leontes. Use the evidence of Shakespeare’s text and the production you saw to decide how that character feels about the king’s behaviour.

Imagine that it is your job to make the case for the defence! Write a speech that puts the argument for Leontes. Draw on evidence from the Propeller production you saw or from Shakespeare’s text. Which characters from the play might you call as witnesses for the defence? Draw up some questions that you would like to ask the witnesses.

You are Leontes. Prepare a statement in your defence.

‘Stage’ the trial as a group, with the case made for and against the king, ‘hotseating’ the witnesses. Then come out of character to work as a jury to decide upon your verdict.