The View from Richmond Hill - WordPress.com · 2015. 4. 4. · The View from Richmond Hill “The...

Transcript of The View from Richmond Hill - WordPress.com · 2015. 4. 4. · The View from Richmond Hill “The...

The View from Richmond Hill

“The terrace at Richmond does assuredly afford one of the finest prospects in the world.

Whatever is charming in nature, or pleasing in art, is to be seen here… whatever be your

ideas of paradise, and how luxuriantly soever it may be depicted to your imagination, I

venture to foretell that here you will be sure to find all those ideas realised... Sweet

Richmond! never, no, never, shall I forget that lovely evening, when from thy fairy hills

thou didst so hospitably smile on me, a poor lonely, insignificant stranger! As I traversed

to and fro thy meads, thy little swelling hills and flowery dells, and above all that queen

of all rivers… I forgot all sublunary cares, and thought only of heaven and heavenly

things. Happy, thrice happy am I, I again and again exclaimed, that I am no longer in

yon gloomy city, but here in Elysium, in Richmond.”

When Karl Moritz penned his florid tribute to the village of Richmond on the Thames, its

reputation as an English arcadia was already growing. The young German clergyman

visited on a walking tour of Britain in 1782, and resting his tired feet looked down the

green hill to the slow bend in the river. He was probably sitting not so very far from the

spot where his countryman Augustine Heckel had some thirty years before sketched The

View from Richmond Hill, which had since been engraved by Charles Grignion and widely

reproduced. Heckel had shown ladies and gentlemen dressed in their finery, parading in

carriages, on horseback and on foot, enjoying the scenery on a bright blue day. The same

perspective was reworked over and again in the nineteenth century, though more often in

dreamy tones and depicting romantic scenes of shepherds and young lovers rather than the

local aristocracy. John Martin provided a representative example, but Turner and

Reynolds also painted it: Wordsworth and Walter Scott memorialised it in verse and

novels. In 1902 it became the only view in Britain to be protected by Act of Parliament.

When the first white inhabitants of the township of Melbourne made their way up the

Yarra and gave the name Richmond to the hill which rose from the left bank of the river

and which provided commanding views to the east, the south and the west: this was the

lustre that they were seeking. A pastoral paradise. And a name which, happily and

patriotically, had royal connections and a noble lineage extending back to the eleventh

century, when Alain Le Roux built a castle in the north of England to put down the local

rebellions against the new king, William the Conqueror. Riche-mont: the strong hill.

Alain’s successors ruled much of the north for many years, and when Henry, Earl of

Richmond ascended the throne as Henry VII in 1485, they ruled the rest of England too. In

1497 the manor house at Sheen in Surrey burnt down. Henry replaced it with the new

Richmond Palace, which became a favored residence for the Tudor monarchs, and the

house where Queen Elizabeth died in 1603.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

What better name for an out of town retreat for the new ruling class of the Port Phillip

District? The name seems to have arisen from popular usage rather than governmental

fiat, but its connotations would have seemed happy enough to officials looking to raise as

much money as possible from the first land sales in 1839. The 25 acre blocks were sold off

as farmlets and fetched £13 to £28 an acre. Some were soon resold, others subdivided, and

within a short time a number of gentlemen’s cottages dotted the hillside. Advertisements

stressed the clean air and the quality of soil, water and timber, as well as a rollcall of

increasingly well-to-do neighbours with whom one might have the chance to mingle should

one be the lucky purchaser of a block amongst "the abode of aristocracy, wealthy and

retired opulence", as an early auctioneer put it. According to the Port Phillip Patriot and

Melbourne Advertiser Richmond would be a sought after location for those refined

gentlemen who would “enjoy after the toil of business and the oppression of the glowing

sun that air which carried health in its path and throws the essence of strength and vigour

round the drooping soul”. William Westgarth would in his later years tell of his adventures

riding out to visit a friend at his “country seat”: it was so remote from the town that there

are (unconfirmed) stories of bushrangers hiding in wait along the road in the vicinity of the

current Fitzroy Gardens. Garryowen, writing some fifty years later, recalled that “In early

days this suburb was a splendid section of green, undulating, well-timbered bush… These

subdivisions were intended for Rus in urbe boxes, where the well-to-do Melbourne

merchants and professionals could retire after the worry and wear, the profit and loss, of a

busy day, and smoke the calumet of peace in the bosoms of their families. It never entered

into the sphere of probability that the then Richmond

would, in a few years, become the great, thriving,

working, hive of busy bees it is to-day.”

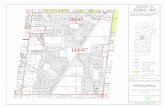

Though Richmond Hill is the name generally given to the

ridge of higher ground overlooking the river flats, it

actually consists of three local peaks. The northwestmost

is today occupied by the Epworth Hospital; the eminence

to the southeast, sometimes referred to as Docker’s Hill

after its early owner the Reverend Joseph Docker, is

claimed by St Ignatius Church. The central part of the

ridge was sold off in 1839 as lots 25 and 26 to HG Brock

and the squatter and banker WH Yaldwyn repectively;

within a year they re-sold the land to John Gardiner and

W Meek, who both commenced subdivisions. On the west side of this hill the newly arrived

Dr Thomas Black began to build his residence, Pine Grove, in 1844. Amongst his claims to

fame: the first use of chloroform in Victoria, along with Farquhar McCrea; the founding of

the Port Phillip Medical Association and the Zoological Society of Victoria; and the

creation of the Bank of Victoria, the idea of which came to him, “inspired by the

exhilarating influence of wine and walnuts”, at a dinner with William Highett and other

local merchants at Pine Grove in 1852.

Dr Black and William Highett were at this time but two of the notable gentlemen residing

on their Richmond country estates. Nearby could be found other businessmen such as the

financier Henry “Money” Miller, founder of banks, building societies and insurance

companies, and a member of the colony’s first Legislative Council; another

parliamentarian in William Bust Burnley, and pastoralist, wine merchant and councillor

Daniel Stodhart Campbell; newspapermen George Cavenagh and Thomas Strode, lawyer

Richard Ocock and the kindly Judge Robert Pohlman, owner of sheep stations. In 1851

Black had a new neighbour on the east side of the hill, James Henty, who proceeded to

build a mansion with the same name as the locality: Richmond Hill. Royal names seemed

woven into the fabric of the suburb: you could find Henty’s place down at the end of

Goodwood St, named for the Duke of Richmond’s house and racecourse in Sussex: just off

Lennox St, which, though it might have been named for the Superintendent of Roads and

Bridges David Lennox, nevertheless recalled the Lennox family – Dukes of Richmond from

the late seventeenth century.

James was part of the notable Port Phillip pioneering

family, eldest son of Thomas Henty. After arriving in the

Swan River settlement in 1829, he spent many years as a

successful merchant in both Launceston and Portland. A

change in fortune in 1846 saw him bankrupt, and moving

back to England with his wife Charlotte and seven

children: but in 1851, in his early fifties he returned to

Melbourne to set up business once again as James Henty

and Co and built his Richmond home to accomodate a

growing family. He was clearly fond of the name: not

only the house but even his son was called Richmond. He

was a man of regular habits, rising early to take coffee

and to record the previous day’s events in his diary. He

would walk from Richmond Hill to his offices in Little Collins St, where it was habitual for

Charlotte to visit him in the afternoon, and then walk back home again in the evening.

Business flourished, and James was appointed to the Legislative Council (which he seldom

attended, and even more rarely spoke at), as a Commissioner of the State Savings Bank,

and as director and chairman of Victoria’s first railway.

This seems to paint a picture of a stern man, but such a portrait would be misleading.

When James and Charlotte settled back into life in Melbourne they had many friends and

were soon to be found dining with Lieutenant-Governor La Trobe, Bishop and Mrs Perry

and other local luminaries. The new house

reflected the Henty’s enjoyment of

hospitality, with large reception rooms on

the ground floor the home for many a

lavish entertainment, no doubt well

supplied with produce from the huge and

splendid gardens. These were one of the

great passions of James’s life, along with

his family, his religion, and cricket – he

was reputed never to have missed a match

at the MCG. The orchard ran down the

flanks of Richmond Hill, boasting peaches, oranges and nuts; the extensive kitchen

gardens fed the family and the many guests. James’s grandchildren raced around

underfoot, picking and eating gooseberries and strawberries, feasting on other preserved

fruits, and playing cricket with their grandpa in the greenhouse on a wet day. Rare plants

and ferns were grown in the conservatory, the air was filled with with the music of the

songbirds in the aviary (competing with the cheerful sqawking of the lorikeets and

cockatoos in the gum trees), and the remaining spaces were fitted out with tennis courts

and statuary. Three gardeners were employed to keep the whole affair in order.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

It was nearly thirty years after its optimistic regal naming that Richmond was finally set for

a visit by genuine royalty. The hospitality for which the wealthier sorts up on the Hill were

famous was set to be at its most liberal in 1867, during the visit of His Royal Highness

Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh. A grand plan was hatched for a Free Banquet for

Melbourne’s poor to be held at Richmond Paddock as part of the celebrations. A committee

led by the entrepeneurial Louis L Smith (later known to the Bulletin as ££ Smith) sourced

donations of food on a magnificent scale: “One bullock, to be roasted whole, 1 baron of

beef, 22 rounds beef, 5cwt roasting beef 12 sheep, 100 legs mutton, 44 lambs, 2 fat pigs,

3cwt pork, 56lb bacon, 14 hams, 50 ox tongues, preserved meat, 284lb German sausage,

7600lb potatoes, 600 dinner loaves, 300 loaves bread, 12 000 half pound loaves, 1 bag and

1cwt rice, 1 dozen tins sardines, 2 bags oysters, 1cwt Murray cod, 9 dozen pickles sauces

and curry, mustard, vinegar, pepper, salt, spices, 40 large plum puddings, 32 large tarts,

60 dozen assorted pastry, 1 box raisins, 4 bags sugar, 1 jar and 3 dozen jams, 80lb fresh

butter, cheese, 2 half chests tea 50lb coffee. WINES, ALES &c. - 900 gallons colonial wine,

4 cases colonial wine, 4 cases champagne, 6 cases claret 2 cases port, 20hhds ale, 54 dozen

stout, 2 dozen Bavarian beer, cordials. EXTRAS FOR CHILDREN: - 3432 buns, 1 050

quarts milk, 3 casks biscuits, 1 tin do , 3 tins lollies, 11 cases fruit, 3hhds gingerbeer, 10

gallons raspberry vinegar, 5 gallons ginger wine”.

Ten thousand people were expected to dine. In the event, the promise of free food and a

glimpse of “our beloved young sailor Prince” drew crowds estimated at between forty and a

hundred thousand. All started well, with half a mile of tables dressed with flowers and

greenery and laden with food, guarded by police, waiting for the royal arrival at one

o’clock. But the day was hot and windy, and more and more Melbournians crushed into the

park. The appointed hour came and went. Where was the Prince? Children cried, people

fainted, hardly a drop of water could be had. The people were “famishing in sight of tons of

provisions, and enduring the tortures of TANTALUS in the immediate vicinity of hundreds

of gallons of wine and beer furnished for their refreshment.” The crowd also noted that the

150 wives and daughters of the better classes sitting in the royal pavilion were not going

short of food and drink. Someone threw an egg at them, ruining a young girls hat. An

initial rush at the tables was quelled by the constabulary, but at half past two the line broke

and the crowds had scoffed the food in minutes. The dusty ground was strewn with bread

and meat scraps, and the mob looked for something better than brackish Yarra water to

drink. A wine fountain had been advertised, but Smith (bravely or foolishly) stood before

the crowd and announced that it would not be set flowing. The police given the task of

guarding the tent with all the booze were meanwhile enjoying its contents, in full view of

the parched public. Coming at the tent from all sides, cases of champagne were pulled out

from underneath the walls until the whole structure collapsed. A hundred gallon wine cask

was breached with the red stuff sluicing down and the crowd drinking as much as possible,

the rest running into the dry earth. Whispers were heard that the Prince was coming: the

banners were raised, taken down again. It later transpired that his carriage had

approached the park at around three o’clock, but had been warned of the disastrous events

occurring up ahead and turned back. The crowds, many of whom were women and

children who had come from many miles around in the genuine hope of a free meal, turned

back for the long trip home hungry and thirsty.

Bitter recriminations followed. The Argus found the embarassment for the colony difficult

to bear: “That these fair expectations should be falsified, and that such brilliant success

should only lead to disastrous defeat, was very hard, and yet we have to record that this

free banquet has proved one of the most tremendous and utter failures we have ever

known.” L.L. Smith blamed the late arrival of the Prince; everyone else blamed the

committee for not opening the tables at the appointed time anyway, before the masses had

been driven wild by hunger and thirst. Public opinion seemed on the side of the Argus: no-

one else thought it the fault of the Prince, and most were glad that he had not come in the

end after all: “We wish to show the Prince our best front and not to parade before him the

dregs of Little Bourke street”.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

The theatrical bent of the neighbourhood evident in schemes such as the Free Banquet was

further embellished in 1866 when actor and impresario George Selth Coppin moved into

Pine Grove, Dr Black’s old house atop Richmond Hill, next door to James Henty. And if

Henty was well known for his entertainments (though perhaps less so now since

Charlotte’s death the previous year), he was outdone by the man who had only settled on

Australia as a destination on the toss of a coin, for after tiring of his native Sussex, Coppin

found no better way to decide between the Antipodes and the Americas. He grew up with

an itinerant theatre company, his father a well to do man who married a woman twice his

age and gave up his inheritance to tread the boards. Young George developed into a fine

comic actor, and made a name for himself in 1850s Melbourne not only as a performer but

also as a proprietor of establishments such as the Theatre Royal and the Cremorne

Gardens pleasure grounds. A Richmond

councillor from 1858 and a generous and

popular local citizen, when George and his

family fell on hard times in 1863 and

returned to England, the citizens of

Richmond farewelled them with a dinner

and a gift of 300 sovereigns. Fortunes

somewhat restored, he returned three

years later and set up home on top of

Richmond Hill, where he lived for the next

forty years before his death in 1906.

Coppin continued to act, introducing new characters such as Milky White to a cast that

included the “vulgar” Billy Barlow, Demosthenes Dodge and Tony Lumpkin. Like his

neighbour James Henty he was elected to the Legislative Council, where he chose a sober

and responsible role rather than treating the parliamentary chamber as a second stage. It

was as an agent responsible for booking touring “artistes” though that he was particularly

well-known, and the talent which he engaged included the Irish actor Gustavus Vaughan

Brooke, Mr and Mrs Charles Kean and Madame Celeste. Many of these performers visited

him at his home: Sarah Bernhardt and the local girl, Richmond born Nellie Melba, were

both guests. By this time Pine Grove was well fitted to host the fabulous parties of which

Coppin was so fond. The ballroom opened through French windows into a fernery; the

dining room similarly joined a long verandah on the cooler south side of the house, which

was fitted with schoolrooms and offices. According to Alec

Bagot in Coppin the Great, the building was added to “until

it became a mansion, a show place of the district. With the

help of his friend Baron von Mueller, he created ferneries,

aviaries, flower gardens, wide sweeping lawns; with horse

paddocks and stables at the rear, from which would emerge

the smartest turnouts in the city. Not only his home, Pine

Grove became the seat from which he directed his manifold

activities… Any pretext was a good excuse to hold a party on

a lavish scale – someone’s birthday, a welcome to a

theatrical ‘star’, or a charity fete, when trees and shrubs

would be festooned with Chinese lanterns, an orchestra

playing in the conservatory, uniformed stewards dispensing

food and drinks. To every leading actor or actress

performing in Melbourne an invitation to Pine Grove bore

the cachet of distinction”.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

But by the end of the nineteenth century the high life of the Richmond Hill gentry was

drawing to a close. Down at the bottom of the hill, the Richmond river flats had been an

industrial and working class area since the 1860s, particularly along the water’s edge,

where ready access to the Yarra had attracted the noxious trades that dealt in the

processing and by-products of dead animals: abattoirs, woolwashers, fellmongers,

tanneries, knackeries and gluemakers. Small scale manufacturing, particularly in clothing

and bootmaking, also spread around the lower reaches of the suburb. By the 1890s

depression the working class tide was rising further up the slope. Come the early years of

the new century, industrial Richmond was in its heyday, with the new factories

increasingly dominating the suburb: the Rosella factory was completed in 1905; the Bryant

& May match factory followed in 1909; Ruwolt’s engineering works, Wertheim’s piano

factory, McNair’s pottery works – the list goes on.

James Henty had passed away in 1882 and the great house was in the hands of relatives.

The wealthy increasingly decamped to suburbs further afield, their stately homes turned

into boarding houses. The Queen’s death in 1901 put an end to another older Victoria. She

was followed in 1906 by Coppin, who passed away peacefully at home in his eighties,

surrounded by his family. The house became a private hospital, but the extensive Pine

Grove gardens were neglected, as were those next door which were so beloved by Henty.

The fruit trees died, the grass grew long and erased the paths, other shrubs and weeds ran

riot: according to the Herald, “All that remains of this princely garden are a statue of Diana

and a bravely flowering lilac bush.” An era had passed, though the next generation still

found a certain delight in these wild spaces in the heart of the suburb and they maintained

a “fairytale quality” for the local children who played amongst them.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

The barbarians seemed at last to have arrived at the very gates of Richmond Hill in 1915,

when the Labor Party dominated Richmond council voted to demolish Pine Grove, and

offer it to the Melbourne Motor-bus Company. The site would “be utilised in the march of

modern transit methods, and the stately old mansion, formerly the residence of the late

Mr. George Coppin, is to be dismantled to make way for an extensive and modern garage,

which will house the motor-buses of the metropolis”. The locals complained that it was an

ill use of the location, an imposition on a residential area which could only decrease their

property values. They claimed that the date of the council vote had been deliberately

moved so that they could not attend to oppose it. The reporter for the Richmond

Guardian, attending the meeting on a hot February night, noted that “It was evident from

very early that the vote would go in favor of the Motor Bus Co and so it proved. The Labor

councillors voted solid”. The Mayor, Gordon Webber, denied accusations of skulduggery,

and in return he also drew “public attention to the fact that members of the deputation

openly stated that they had no objection to a garage being built in Richmond so long as it

was not located in their own aristocratic neighbourhood but it could be placed (as one

member of the deputation naively put it) 'down the other end’ the other end being the east,

or working mans, part of Richmond”. Webber had a bit of a thing about the aristocracy. A

thirty year old rising star of the Political Labor Council, Mayor of Richmond, Secretary of

the Soap and Candle Workers Union, Member for Abbotsford in the Victorian parliament,

he was a teetoller, a Unitarian, and – to the horror of not only the establishment but also

some of his Labor comrades – a republican who refused to make the Loyal Toast at

functions.

The political class had changed along with the suburb. Gone were the patricians, and in

their place a new Labor political royalty. Four hundred years after Henry Tudor built

Richmond Palace, Frank Tudor became the local member for the seat of Yarra (covering

the Richmond area) in the new federal Parliament. As a hatmaker’s apprentice he travelled

to Britain and America to study international examples of trade unionism. On his return to

Melbourne he worked at the local Denton Mill, became president of the Felt Hatters' Union

and by 1900 had also become the president of the Victorian Trades Hall Council. Elected to

the new federal parliament as the local representative of the Political Labor Council, Tudor

became Secretary of the Labor Party, and Minister for Trade and Customs under the Fisher

governments, before finally becoming the leader of the federal Labor Party in opposition

from 1917.

Despite the intervention of the

Labor councillors, the bus depot

was never built. The Melbourne

Motor Bus company had 38 buses

and 150 employees at this time,

and grand plans for expansion.

The council believed that locating

the garage in Richmond would not only provide work for local men, but also provide cheap

transport into town. The company though was ill-starred. Despite winning this particular

battle against the aristocrats of Richmond Hill, their services were affected by a series of

strikes by drivers and conductors, and a fire at a motor-body builder works in St Kilda road

destroyed several of their vehicles. The proprietor, Edward Fitzgerald, was declared

bankrupt in 1916 and his fleet of Daimler charabancs and Tilling Stevens buses sold off.

But not in time to save Pine Grove: Coppin’s house and gardens were demolished, and the

land now lay vacant. A few years later, Mrs Henty-Wilson, last of the Henty line at

Richmond Hill, passed away. Both sites were purchased by a local shirt making company,

originally with premises in Carlton and Fitzroy, by the name of Pearson Law and Co:

shortened in 1917 to the more memorable Pelaco.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Frank Tudor would have seen the new Pelaco factory going up on Richmond Hill, but died

in January 1922 shortly before it opened. It cost £72,000, and was designed to be state of

the art in both production and employee comfort. Four storeys high, with workrooms that

(the company proudly boasted) were a third of a mile round the edge, with high ceilings

and large windows providing natural light and views. Advertisements for new staff claimed

it would be “the happiest factory in Australia” – “To girls of the right sort we offer steady

employment throughout the year; ideal working conditions, in the finest factory of its kind

in Australia; short hours, highest rates of pay. Come and join us, and be proud you’re a

Pelaco girl”.

Despite a commitment to relatively progressive labour relations, the work was intensive

and exhausting, from the cutting rooms – where material was folded so that 200 shirts

were made from a single cut – to the banks of electric sewing machines. One and a half

million shirts and pyjamas and three million collars were turned out every year. Whilst

Pelaco employed experienced machinists it also sought a steady supply of 15 to 17 year old

girls to train: much older than this and the minimum weekly wages were too high, though

staff were on piece-work rates and could generally earn more if they were quick. A

Taylorist approach pervaded the factory, including recruitment. Prospective employees

were interviewed by female personnel officers who tried them at different tasks and

assessed whether they were capable of handling the speed and monotony of the work. If

found unsuitable, the girls were sacked after three months. Eighty per cent lasted less than

a year at the machines.

Hard work was rewarded by the annual Pelaco

picnic. On the last Saturday before Christmas

in the company’s first year on Richmond Hill,

about a thousand staff took a ship from Port

Melbourne to Mornington, dancing along the

way to an orchestra from the Institute of the

Blind, reaching their destination by late

morning. As well as eating and drinking and

dancing there was a full sports program (Sack

Race, Elopement Race, Interdepartmental

Relay Race, Blindfold Race and a Rounders

competition, won by the Collars Department) and a competition for the Most Beautiful

Brunette and Most Beautiful Blonde. Observers were impressed by their model behaviour,

assessing them as “quiet and pleasant… quite a superior lot of girls”.

The Pelaco factory itself towered over the suburb below, the final demonstration of the

ascent of industry over local aristocracy: though from the right angle, perhaps a

resemblance to the original Richmond Castle in Yorkshire could be seen in its blocky

crenellations. The owners obviously worried that it was not yet visible enough. In 1939 the

staff newsletter Pelacograms proudly announced that “we’re getting a neon sign soon,

fourteen foot letters and double sided on the very pinnacle of the roof. All Melbourne will

know where we “hang out””. Though no longer in operation, the Pelaco sign has been

classified by the National Trust and is one of several iconic neon installations still to be

seen around the suburb.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

When James Henty, Dr Thomas Black, George Coppin and their ilk built their grand

homes, the View from Richmond Hill that they had in mind was no doubt something like

that shown by Heckel and Martin. And for some time, allowing for changes in fashion and

the design of carriages, substituting river gums and blackwoods for the orderly rows of

deciduous trees, and replacing the shepherds with groups of Wurundjeri people hunting

and fishing on the flats: well, with a bit of a squint as you looked back down the river Yarra,

it might not have seemed too dissimilar, the relatively open fields dotted by new houses

here and there. But by the time the Pelaco factory was completed in the 1920s the view was

a very different one. The fields were bricked over, the trees replaced by chimneys.

The Aboriginal people of the area too had long gone – only to

return as caricature, when Pelaco created a long running

advertising campaign based on the figure of an Aboriginal man,

along with the slogan ‘mine tink it they fit’. “Pelaco Bill” was

apparently modelled on a 1911 sketch by commercial artist A.T.

Mockridge of Mulga Fred, rodeo rider, horse whisperer,

stockwhip and boomerang master who was a fixture at shows

throughout south-eastern Australian for several decades. Fred

was, conveniently, reported to be proud to have his picture used

so prominently, and received a regular supply of new shirts from

the company as an ongoing form of thanks. He went by various

names: Mulga Fred, Fred Wilson, Fred Clark, and The King of

Poison Creek. This last name has a certain resonance: one Pelaco advert shows him rising

from the top of the Richmond Hill factory, preparing to throw a boomerang across the flats

of the foetid and polluted Yarra, where Indigenous people had fished less than a century

before.

Pelaco Bill though was a figment of an advertiser’s imagination, and the factory rooftop

was in reality the domain of the Pelaco girls. Nine hours a day on the vast clattering floors

of sewing machines, with breaks for morning and afternoon tea, and at one o’clock every

day the machinery was shut down for the “luncheon half-hour” in the café on the fourth

floor. It had a piano and a dancefloor, and “many of the girls enjoy the pleasure of jazzing”.

Not quite, perhaps, like the society soirees of old that took place on the very same spot in

Coppin’s Pine Grove, but considerably larger: the café could serve a thousand staff. And if

you were not in the mood for jazzing, or just wanted a breath of fresh air – well, you could

always pop upstairs, lean over the balcony and take in the suburb spread out below you –

the View from Richmond Hill.