THE SOUL OF THE APE - Valdosta State University › ~jloughry › BIOL4650 › Essay... · THE SOUL...

Transcript of THE SOUL OF THE APE - Valdosta State University › ~jloughry › BIOL4650 › Essay... · THE SOUL...

MACROSCOPE

THE SOUL OF THE APE

Clive D. L. Wynne

My title is borrowed from a book by Eu-gene Marais (1871-1936), publishedposthumously in 1969.Marais was one

of the first to make a closestudy of the behavior ofnonhuman primates in the wild. His analyses werefar ahead of their time, because he attempted tounderstand the actions of these creatures in termsof the evolutionarycontinuitywith Homosapiensthat Charles Darwin had earlier proposed. Al-though genetic analyses were still a long way off,itwas obvious to Darwin and his converts in the19thcentury that the great apes-chimpanzees, go-rillas, orangutans and bonobos, or pygmy chimps-must be our distant cousins. "He who under-stands baboon," Darwin noted, "would do moretoward metaphysics than Locke."

Although today we recognize baboons asmonkeys, not apes, and therefore less closely re-lated to us, Darwin's point still stands. AndMarais was on the right track when he observedfree-living and captive baboons in his nativeSouth Africa and puzzled over the similarities-and differences-he could see between their be-havior and that of human children and adults.

Most of the questions with which Marais grap-pled remain unanswered. But in recent years at-tempts to understand primate minds havespawned a controversial new ethic. It is based onthe notion that the differences in psychology be-tween people and other great apes are too smallto justify different treatment. That is, nonhumanapes should get the same ethical considerationthat their human brethren receive. This view ismost manifest in the Great Ape Project, whichdescribes itself as working to raise the legal andmoral status of these animals. The ultimate aimof this group is to have the United Nations adopta declaration on the rights of nonhuman apes,one that would make all medical research onthem impossible.

Clive D. 1. Wynne is a senior lecturer in the Df7!artment ofPsy-

chology at The University of Western Australia. This essay was

written while he was a visiting scholar in the Department ofPsychology at Duke University. Address: The University ofWestern Australia, Nedlands, Western Australia 6907.

Internet: [email protected]

120 American Scientist, Volume 89

Supporters of the Great Ape Project are im-pressed by the genetic similarity between peopleand nonhuman apes and by the relatively shortperiod of time since we and our closest relatives(chimpanzees) diverged from a common ancestor.Most advocates of this project point to what theyconsider the key psychological similarity betweennonhuman apes and ourselves: Nonhuman apes,they argue, are self-aware. As a consequence ofthis self-awareness, gorillas, chimpanzees, bono-bos and orangutans must suffer in captivity inways not so different from what we would expe-rience under similar circumstances.

This is not an abstract scholarly debate. Thereare about 1,600chimpanzees held for biomedicalresearch in the U.S., and these animals are essen-tial to the study of several maladies, ones forwhich few if any other approaches are available.Probably the single most important example isliver disease. It was research on chimpanzees thatprovided the vaccine against hepatitis B.Carriersof hepatitis B are about 200 times more likely todevelop liver cancer than the general population,so the hepatitis B vaccine can be considered thefirst cancer vaccine. More than a million peoplein the United States have been infected with he-patitis B,and nearly half the global population isat high risk of contracting this virus. Chim-panzees have also been crucial for the study ofhepatitis C, a chronic disease for some four mil-lion Americans.

And hepatitis just heads the list. AIDS is an-other prominent example, because chimpanzeesare the only nonhuman species that can be in-fected with HIV-l, the common form of the virusfound throughout the world. The reason becameclearer last year, when investigators found proofthat HIV-l spread to humans from chimps earlyin the 20th century. Now more than 36 millionpeople around the world are infected with thisvirus, and some 22 million have already diedfrom AIDS. Chimpanzees continue to be im-mensely valuable in the search for a vaccine.Chimps are also helping scientists to battle otherdire health problems, including spongiform en-cephalopathy ("mad-cow disease"), malaria, cys-tic fibrosis and emphysema.

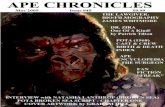

Figure 1. Seemingly doleful gaze of a baby gorilla inspires questioning about whether such great apes are self-aware.

50 the stakes are very high indeed. On the onehand, precisely because they are closely relatedto us, nonhuman great apes are the only suitablespecies for research on several diseases that causeimmense human suffering. On the other hand,these creatures may be so similar to ourselvesthat making them the subjects of biomedical ex-perimentation may be difficult to justify ethically.This could be a Faustian dilemma-are we sell-ing chimp souls to better our human lives?

I don't pretend to have the answer to such aweighty moral question. But as a psychologist Ido feel qualified to examine one of the reasons be-ing cited for providing these creatures with rights:the idea that nonhuman great apes are self-aware.In my view, the evidence for this assertion is con-siderably exaggerated. 5everallines of reasoninghave been put forward to buttress this claim. Letme examine each of these arguments in turn.

First, it is said, the minds of nonhuman greatapes are much like ours because some of theseanimals have been taught to use language-signlanguage. Research on the abilities of chim-panzees and bonobos to communicate usingsigns has been going on for more than 30 years.The early excitement that accompanied reports ofsigning chimpanzees has died down, perhaps be-cause the details are not that compelling. In allthese studies, the animal's vocabulary developedpainfully slowly, and it never exceeded a coupleof hundred signs (about two weeks' work for ahealthy two-year-old child). Often the chimp in-volved could only repeat gestures, and in anycase, chimpanzee "sentences" rarely extend be-yond one or two signs-making any discussionof grammar or syntax seem rather forced.

The occasional anecdote of a chimpanzeeforming a novel combination of signs to repre-

2001 March-April

"':e0u

§

j~~

121

sent a word he had not been taught (such as sign-ing water-birdfor swan) prompted some to be-lieve that these animals indeed have an innatecapacity for language. But in reality such casesare extremely rare and quite hard to interpret.How does one know, for example, that thischimp did not intend two distinct utterances, wa-ter and bird, to indicate the two things then inview? In my estimation, such curiosities con-tribute little to the debate.

Somewhat more relevant are recent reports of abonobo named Kanzi, whose linguistic abilities(as expressed by pressing buttons on a specialkey-board) are alleged to far exceed those seen duringthe earlier sign-language studies with chim-panzees. A critical test for Kanzi's comprehensionof sentence structure involved asking him to re-spond to an instruction such as "would you pleasecarry the straw?" Sure enough, Kanzi picks up thestraw. But there's a weakness here. Although itcould be that grammar conveyed the correctmeaning of the test sentence, it could equally bejust the circumstances that made the requested ac-tion obvious (given that Kanzi knows what thewords carryand straw refer to). After all, a chimpmay carry a straw; a straw cannot carry a chimp.Investigators have also claimed to discern gram-matical structure in Kanzi's own keyboard strokes.But because the average length of his utterances isaround 1.5 pushes, I believe that a meaningfulanalysis of grammar or syntax is impossible.

The second tier of evidence for self-awarenessin nonhuman apes comes from so-called mirrortests. These experiments can be conducted in sev-eral different ways. For example, while the sub-ject is anesthetized or sleeping, the experimenterplaces a mark on the forehead or ear with anodorless, tasteless dye. Upon waking, the animalis shown a mirror. Will the creature recognizethat the splash of dye is on his own face? The an-swer is taken to be yes if the animal touches themarked area of skin more often with a mirror infront of him than without.

Although there were methodological problemswith some earlier studies, it is now broadly ac-cepted that chimpanzees, bonobos and orang-utans can recognize themselves in mirrors.Claims that dolphins and gorillas can pass thistest are disputed. And all other species examined(including fish, dogs, cats, elephants and parrots)react to themselves in a mirror either not at all oras if the reflection is another animal.

The problem with the mirror test of self-recognition lies not in the results-clearly somenonhuman apes can recognize themselves in mir-rors-but in the interpretation. Why should suchself-recognition be equated with self-awareness?Some people cannot recognize themselves in mir-rors (blind people are the most obvious group),but nobody suggests they lack any aspect of self-awareness. Conversely, in autistics self-awarenessis clearly impaired. And yet autistic children de-velop the ability to recognize themselves in mir-

122 American Scientist, Volume 89

rors at the same rate as normal children. So thesetests of self-recognition in mirrors are interestingand doubtless say something about how animalsview their bodies, but they tell us nothing aboutthe deeper question of self-awareness.

The final set of evidence for self-awareness innonhuman apes comes from something called"cognitive perspective taking." Daniel Povinelliand his colleagues at the University of Southwest-ern Louisiana developed the best-known experi-ment of this sort. They based it on certain teststhat are used to judge mental development inautistic children. In Povinelli's "guesser-knower"experiment, a chimpanzee watches a trainer putfood into one of four cups. The chimpanzeeknows that the cups are there (hewas shown thembefore the experiment started) but cannot seewhich of them receives the food. Another trainerwho has viewed the manipulations (the knower)then points to the baited cup. A third trainer whohas not seen the food go in (the guesser) points toa different cup. A chim~r child-who has anawareness that others have minds, can readily ap-preciate that one trainer knows where the food ishidden, and the other one doesn't.

Chimpanzees in these experiments were ulti-mately successful in picking the cup containingthe food (selecting the cup pointed to by theknower), but they required many hundreds oftraining experiences before they could make theright choice reasonably consistently. This patternsuggests only that the apes involved graduallylearned to associate one stimulus (the knower)with the reward, not that the animal is treatingthe trainers as people with minds.

In more recent experiments, Povinelli and hiscoworkers offered a chimpanzee a choicebetweenbegging from a person who could see variouspieces of food and begging from a person whocould not (because she was blindfolded, for ex-ample). To the experimenters' surprise, chimpswere initially just as likely to approach the trainerwho could not possibly see the food. With enoughexperience, the chimps gradually learned to askonly the person with unrestricted vision for a tastymorsel. But they showed no spontaneous under-standing that being unable to see disqualified aperson from providing snacks. So here again, Ifind little to indicate that apes have any aware-ness of the minds of others, much less that theyhave an awareness of their own thoughts.

In truth, scientists do not yet know much aboutthe soul of the ape. But we've learned a few thingssince Marais made his pioneering observations.It is clear that these animals do not show self-awareness in anything likethe ways a human does,even when given the tools to do so. But if theirminds are not like ours, what are they like? I don'tknow. I don't even know how we would drawethical conclusions from that knowledge ifwe hadit. The only thing I'm sure of is that we shouldview apes as worthy of wonder for being whatthey are-not merely as reflections of ourselves.