The Right to Fight African-American Marines in World … Right to...The estimated 5,000 blacks, free...

Transcript of The Right to Fight African-American Marines in World … Right to...The estimated 5,000 blacks, free...

African-Americans and the Marines

T he estimated 5,000 blacks, free men and slaves,who served the American cause in the Revolution-ary War included at least a few Continental Ma-

rines. For example, in April 1776 Captain Miles Penning-ton, Marine oificer of the Continental brig Reprisal,recruited a 5lave, John Martin (also known as Keto),without obtaining permission from the slaveholder, Wil-liam Marshall of Wilmington. Delaware. Private Martinparticipated in a cruise that resulted in the capture of fiveBritish merchantmen, but died in October 1777, along withall but one of his shipmates, when Reprisal foundered ina gale.

Two other blacks, Isaac Walker and a man known onlyas Orange, enlisted at Philadelphia's Tun Tavern in a com-pany raised by Robert Mullan. the owner of the tavern.which served as a recruiting rendezvous for Marines. Cap-tain Mullan's company, part o a battalion raised by MajorSamuel Nicholas, crossed the Delaware River with GeorgeWashington on Christmas Eve 1776 and fought the Britishat Princeton. The wartime contributions of the black Con-tinental Marines, and the other blacks who served on landor at sea, went unrewarded, for the armed forces of theindependent United States sought to exclude African-Americans.

For a time, a militia backed by a small regular Army—both made up exclusively of whites — seemed force enough

to defend the nation, but tensions between the United Statesand France resulted in the building of a fleet to replace thedisbanded Continental Navy. In 1798, when the time ar-rived to recruit crews for the new warships, the Navybanned "Negroes or Mulattoes," grouping them with "Per-Sons whose Characters are Suspicious:' The Commandantof the reestablished Marine Corps, Lieutenant Colonel Wil-liam Ward Burrows, followed the Navy's example andbarred African-Americans from enlisting, although blackdrummers and fifers might provide music to attract poten-tial recruits.

The Marine Corps maintained this racial exclusivenessuntil World War II. Its small size enabled the Corps torecruit enough whites to fill its ranks, but other considera-tions may also have helped shape racial policy. Marinesmaintained order on shipboard and at naval installations,and the idea of blacks exercising authority over whitesailors would have shocked a racially conscious America.The Marine Corps, moreover, had a sizable proportion ofSouthern officers, products of a society that had held blackslaves. Not even the Northern victory in the Civil War,which enforced emancipation, could bring the racestogether in the former Confederacy. Jim Crow, the per-sonification of racial segregation, rapidly imposed his gripon the entire nation, assuming the force of law in 1896when the Supreme Court decided Plessy v. Ferguson and,in effect, isolated blacks from white society.

government and establishing the FairEmployment Practices Commissionto monitor compliance. He also in-creased pressure on the armed forcesto provide blacks better treatmentand broader opportunities as he hadpledged during the previous autumn.

The naval establishment had beenslow to carry out the President'swishes. As late as the summer of1941, Secretary of the Navy FrankKnox continued to oppose therecruiting of African-Americans, ex-cept as stewards in officers' messes.He insisted that the restrictions onopportunities actually benefitedblacks, for in other specialties theywould have to compete on equalterms with whites and could not pos-sibly succeed. Since the President, anAssistant Secretary of the Navy dur-ing World War I, took a personal in-terest in the Navy and Marine Corps,Knox realized these services wouldhave to lower their racial barriers and

reluctantly suggested recruiting 5,000blacks for general service. In Janu-ary 1942, while the General Boardconsidered this proposal and reflectedon the presidential pressure behindit, General Holcomb voiced his deep-ly felt misgivings. Although furtheropposition could only be futile, theCommandant complained that thoseblacks seeking to enlist in the MarineCorps were "trying to break into aclub that doesn't want them:' The"negro race7 he argued, "has everyopportunity now to satisfy its aspir-ations for combat in the Army,"which had maintained four regularregiments of black soldiers sinceshortly after the Civil War.

Roosevelt tried to avoid antagoniz-ing a reluctant Navy, offering assur-ance that it need not "go all the wayat one fell swoop" and racially inte-grate the general service. He keptpushing, however, for greater oppor-tunities for blacks within the bounds

2

of segregation, and the Navy couldnot defy the Commander in Chief.Secretary Knox on 7 April 1942 ad-vised the uniformed leaders of theNavy, Marine Corps, and CoastGuard (a component of the wartimeNavy) that they would have to ac-cept African-Americans for generalservice. Some six weeks later, theNavy Department publicly an-nounced that the Navy, MarineCorps, and Coast Guard would en-list about 1,000 African-Americanseach month, beginning 1 June, andthat the Marines would organize aracially segregated 900-man defensebattalion, training the blacks recruit-ed for it from the beginning of bootcamp onward.

On 25 May 1942 the Commandantof the Marine Corps issued formalinstructions to begin on 1 June to

Change Comes tothe Marine Corps

African-Americans and the Marines he estimated 5,000 blacks, free men and slaves, who served the American cause in the Rwolution- ary War included at least a few Continental Ma-

rines. For example, in April 1776 Captain Miles Penning- ton, Marine officer of the Continental brig Reprisal, recruited a slave, John Martin (also known as Keto), without obtaining permission from the slaveholder, Wil- liam Marshall of Wilmington, Delawate. Private Martin participated in a cruise that resulted in the capture of five British merchantmen, but died in October l m , along with all but one of hi shipmates, when Reprisal foundered in a gale.

Two other blacks, Isaac Walker and a man known only as Orange, enlisted at Philadelphia's Tun Tavern in a com- pany raised by Robert Mullan, the owner of the tavern, which served as a d t i n g rendezvous for Marines. Cap- tain Mullan's company, part of a battalion raised by Major Samuel Nicholas, crossed the Delaware River with George Washington on Christmas Eve 1776 and fought the British at Princeton. The wartime contributions of the black Con- tinental Marines, and the other blacks who served on land or at sea, went unmvaded, for the armed forces of the independent United States sought to exdude African- Americans.

For a time, a militia backed by a small regular Army - both made up exclusively of whites - seemed force enough

to defend the nation, but tensions between the Unitd States and France resulted in the building of a fleet to replace the disbanded Continental Navy. In 1798, when the time ar- rived to recruit arws for the new warships, the Navy banned "N- or MulattoesIn grouping them with "Per- sons whose Characters are Suspicious." The Commandant of the reestablished Marine Corps, Lieutenant Colonel Wi- liam Ward Burrows, followed the Navy's example and barred African-Americans from enlisting, although black drummers and Hers might provide music to attract poten- tial recruits.

The Marine Corps maintained this racial exclusiveness until World War 11. Its small size enabled the Corps to recruit enough whites to fill its ranks, but other considera- tions may also have helped shape racial policy. Marines maintained order on shipboard and at naval installations, and the idea of b l a h exercising authority over white sailors would have shocked a racially conscious America. The Marine Corps, moreover, had a sizable proportion of Southern officers, products of a society that had held black slaves. Not even the Northern victory in the Civil War, which enforced emancipation, could bring the races together in the former Confederacy. Jim Crow, the per- sonification of racial segregation, rapidly imposed his grip on the entire nation, assuming the force of law in 1896 when the Supreme Court decided Plessy v. Ferguson and, in effect, isolated blacks from white society.

government and establishing the Fair Employment Practices Commission to monitor compliance. He also in- creased pressure on the armed forces to provide blacks better treatment and broader opportunities as he had pledged during the previous autumn.

The naval establishment had been slow to carry out the President's wishes. As late as the summer of 1941, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox continued to oppose the recruiting of African-Americans, ex- cept as stewards in officers' messes. He insisted that the restrictions on opportunities actually benefited blacks, for in other specialties they would have to compete on equal terms with whites and could not pos- sibly succeed. Since the President, an Assistant Secretary of the Navy dur- ing World War I, took a personal in- terest in the Navy and Marine Corps, Knox realized these services would have to lower their racial barriers and

reluctantly suggested recruiting 5,000 blacks for general service. In Janu- ary 1942, while the General Board considered this proposal and reflected on the presidential pressure behind it, General Holcomb voiced his deep- ly felt misgivings. Although further opposition could only be futile, the Commandant complained that those blacks seeking to enlist in the Marine Corps were "trying to break into a club that doesn't want them." The "negro race," he argued, "has every opportunity now to satisfy its aspir- ations for combat in the Army," which had maintained four regular regiments of black soldiers since shortly after the Civil War.

Roosevelt tried to avoid antagoniz- ing a reluctant Navy, offering assur- ance that it need not "go all the way at one fell swoop" and racially inte- grate the general service. He kept pushing, however, for greater oppor- tunities for blacks within the bounds

of segregation, and the Navy could not defy the Commander in Chief. Secretary Knox on 7 April 1942 ad- vised the uniformed leaders of the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard (a component of the wartime Navy) that they would have to ac- cept African-Americans for general service. Some six weeks later, the Navy Department publicly an- nounced that the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard would en- list about 1,000 African-Americans each month, beginning 1 June, and that the Marines would organize a racially segregated 900-man defense battalion, training the blacks recruit- ed for it from the beginning of boot camp onward.

--#-a *-Oyr

O n 25 May 1942 the Commandant of the Marine Corps issued formal instructions to begin on 1 June to

recruit qualified "colored malecitizens of the United States betweenthe ages of 17 and 29, inclusive, forservice in a combat organization."Given the nature of American soci-ety in 1942, that organization wouldbe racially segregated, the blacks inthe ranks being commanded bywhites. Those black volunteerswhom the Marine Corps acceptedwould, as most wartime whiterecruits, enter the reserve for the du-ration of the war plus six months, buttheir active duty would be delayeduntil the completion of a segregatedtraining camp, scheduled for 25 July.Some of the new recruits would serveas specialists, everything from cooksto clerks, who would see to the day-to-day operation of a racially exclu-sive training camp.

The task of forming and trainingeven one battalion of African-Americans seemed a formidablechallenge, for it involved giving rawrecruits their basic skills, further hon-ing the fighting edge, and finallycreating a combat team. General RayA. Robinson, in 1942 a colonel in

charge of the Personnel Section, Di-vision of Plans and Policies, at Ma-rine Corps headquarters, confessedduring an interview in 1968 that theadmission of blacks "just scared us todeath" Although the draft did not be-come the normal source of recruitsfor all the services until December1942, and the first draftees did notenter the Marine Corps until Janu-ary 1943, Robinson sought help fromthe Selective Service System, wherea black officer of the Army Reserve,Lieutenant Colonel Campbell C.Johnson, had been called to activeduty as an administrator. Johnson in-dicated that he would do what hecould and joked about passing theword that Marines die young, so thatonly those African-Americans will-ing to risk their lives would join.Robinson acknowledged that theCorps "got some awfully goodNegroes" over the years and believedthat Johnson was at least partlyresponsible.

Despite Johnson's interest in theblack Marines, the Corps had to relythroughout 1942 on volunteers, and

3

recruiting proved sluggish. By mid-June, only 63 African-Americans hadenlisted and recruiters were becom-ing desperate, since the training campfor blacks neared completion. Thislack of immediate results reflected thefact that the Marine Corps, after ex-cluding African-Americans since theAmerican Revolution, was attempt-ing to sign up recruits in a black com-munity that had no tradition ofservice as Leathernecks. Recruitersfound it especially difficult to sign upthe truck drivers, cooks, and typiststo support the battalion, even thoughblack educators assured the MarineCorps that an adequate pool of suchspecialists existed. When a recruiterin Boston told Obie Hall that hecould enter the Marine Corps im-mediately if he had the rightspecialty, Hall said he was a truckdriver. Although he "no more coulddrive a truck than the man in themoon," he wanted to go and had nohope of passing himself off as a cookor typist.

The number of African-Americanswho shared Hall's enthusiasm slow-

Painting by Col Charles H. Waterhouse, USMCR (Ret.)A black American served with the Marines when Gen George Washington fought the Battle of Princeton in January 1777.

ly increased. Some of those whojoined up looked on serving in theMarine Corps as an opportunity de-nied blacks for a century and a half.Others saw this service as a personalchallenge. By the end of September,about half of the 1,200 recruits need-ed to man the battalion and renderadministrative, housekeeping, andtransportation support had enlisted.The Presidential decision on 1 De-cember 1942 to make the SelectiveService System the normal source ofrecruits for all the services ensuredthat, beginning in January 1943,1,000 African-Americans would enterthe Marine Corps each month. Thisinflux resulted from the fact that thedraft law prohibited racial discrimi-nation in its administration; in prac-tical terms, this meant that the Armyand Navy could establish quotas forblack recruits but not arbitrarily ex-clude them.

While preparing to absorb theAfrican-Americans provided by the

Selective Service System, the MarineCorps reaffirmed its commitment toracial segregation, but it proposed tocarry out this policy without chan-neling blacks into meaningless as-signments that had little to do withwinning the war. Lacking recent ex-perience with blacks, the Marinessought to profit from the example ofthe Army, which avoided placingblacks in charge of whites. Applyingthis lesson, General Holcomb inMarch 1943 issued Letter of Instruc-tion 421, which declared it "essentialthat in no case shall there be colorednoncommissioned officers senior towhite men in the same unit, anddesirable that few, if any, be of thesame rank." LOl 421 was a classifieddocument and did not become pub-lic during the war, but the African-American Marine who could notearn promotion because a white non-commissioned officer blocked hispath immediately felt its impact. Toremove this racial roadblock while

adhering to the policy of segregation,white noncommissioned officerswould be removed as promptly andcompletely as feasible from the newlyorganized black units, forcing theMarine Corps to create in a matterof months a fully functioning cadreof black sergeants and corporals.

At best, the Commandant hadmixed feelings about the blackrecruits whom the Roosevelt ad-ministration had forced on him. "AllMarines;' he proclaimed, "are entitledto the same rights and privileges un-der Navy Regulations," but even ashe announced this idealistic princi-ple, he felt compelled to remind theAfrican-Americans that they should"conduct themselves with proprietyand become a real credit to theCorps" and to require periodicreports on their status. The blackMarines clearly faced a struggle foracceptance within the Corps beforethey got the opportunity to fight theJapanese.

Cpl Edgar R. Huff drills a platoon of recruits at the Mont ford Huff became a legend among the Marines who were trainedPoint Camp. He enlisted in the Marine Corps in June 1942. here. He retired in 1972 as a sergeant major at New River.

National Archives Photo 127-N-5337

4

Service in the Marine Corpsbrought men like Obie Hall, who en-listed from the cities of the Northwhere race relations were somewhatrelaxed, into contact with segregationat its harshest. Hall received asleeping-car ticket for the rail jour-ney from Boston to the training sitein North Carolina, and all went welluntil he reached Washington, D.C.,where he was ordered out of his as-signed berth. A porter, also anAfrican-American, explained thatHall had reached the "black line"south of which rail travel wassegregated. The porter, in defiance ofthe law and social custom of thattime, found an empty compartmentthat Hall occupied for the rest of thetrip. Some 18 months later, John R.Griffin of Chicago did not find asympathetic porter willing to breakthe rules; at Washington he had totransfer to a Jim Crow car, "hot,dirty, crowded (with babies cryingand old men drinking and [black}Marines discussing the fun they hadon leave)."

Segregation prevailed at the Ma-rine Barracks, New River, NorthCarolina — soon redesignated CampLejeune—where the African-Americans would train, and in thenearby town of Jacksonville. For theblack recruits, the Marine Corps es-tablished a separate cantonment, theMontford Point Camp, in western-most Camp Lejeune. At least oneMarine veteran, Lieutenant GeneralJames L. Underhill, suggested inretrospect that the Corps made a mis-take in pushing them "off to one corn-er;' for doing so reinforced the belief,accurate though it was, that blackswere not truly welcome. The MarineCorps, Underhill believed, "shouldhave dressed them up in blue uni-forms and put them behind a bandand marched them down FifthAvenue" to show their pride in beingMarines and their acceptance by theCorps. At the time, as Underhill sure-ly realized, neither the Marine Corps

nor much of American society wasready for such a gesture of racialamity.

The Montford Point Camp con-sisted at first of a headquarters build-ing, a chapel, two warehouses, amess hall, a dispensary, a steamgenerating plant, a motor pool,quarters and recreational facilities forthe white enlisted men who initiallystaffed the operation, a barber shop,and 120 green-painted prefabricatedhuts, each capable of accommodat-ing 16 recruits, though twice thatnumber were sometimes jammed intothem, pending the completion of newbarracks. The original camp alsoboasted a snack bar that dispensedbeer, a small club for the whiteofficers, and a theater, one wing ofwhich was converted into a library.As the black Marines cleared theland around the camp, they encoun-tered clouds of mosquitoes, a varie-ty of snakes, and the tracks of anoccasional bear, if not the animal it-self. To the north of the original site,across a creek, lay Camp Knox, oc-cupied during the Great Depressionof the 1930s by a contingent of theCivilian Conservation Corps, anagency that put jobless young mento work, under military supervision,on public improvements and recla-

5

mation projects. As the number ofAfrican-American Marines increased,they spilled over into the old CCCcamp.

Railroad tracks divided white resi-dents from black in segregated Jack-sonville. Suddenly, hundreds ofAfrican-American Marines on libertyappeared on the white side of thetracks, looking for entertainment. Atfirst, white businessmen reacted tothis sight by bolting their doors. Eventhe bus depot shut down until some-one realized that the liberty partiesmight well find other North Caroli-na towns like New Bern or Wilming-ton more attractive than Jacksonville,and the ticket agents went back towork.

Getting out of Jacksonville becameeasier, but returning to camp fromthe town proved difficult on a JimCrow bus line. Drivers gave priorityto white passengers, as state law re-quired, and restricted black pas-sengers to the rear of the bus, unlesswhites needed the space. Since thetwo races formed separate lines at thebus stop, drivers tended to take onlywhites on board and leave the blackMarines standing there as the dead-line for returning to Montford Pointdrew nearer. When this happened,angry black Marines, at the risk of

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 5344Sgt Gilbert H. "Hashmark" Johnson, a veteran of service in both the Army andNavy, glares at the boots in his recruit platoon. He became a Marine in 1942.

The 'Great White Father'olonel Samuel A. Woods, Jr.,launched the training programfor black Marines at Montford

(originally Mumford) Point. At thistime, based on the Army's practices, theMarine Corps believed that officers bornin the South were uniquely suited tocommanding African-Americans, andthe colonel fit the pattern, since he hailedfrom South Carolina. Born at Arlington,he graduated from The Citadel, SouthCarolina's military college, and in 1906accepted a commission in the Corps. Heserved in Haiti and Cuba but arrived inFrance as World War I was ending. Af-terward he saw duty in the Dominican

Republic and China, attended the NavalWar College, and headed the MarineCorps correspondence schools at theMarine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia.

The colonel's calmness and fairnessearned him the respect of the blacks hecommanded. He cultivated a paternalis-tic relationship with his men andemerged, according to one African-American veteran of the Montford PointCamp, as "the Great White Father ofeverybody," trying to ease the impact ofsegregation on the morale of his troops,though he accepted the separation of theraces, and insisting that the black Ma-rines exhibit self-pride and competence.

National Archives Photo 127-N-9511Col Samuel A. Woods, Jr., establishedthe Montford Point Camp and alsoserved as the first commanding officer ofthe 51st Defense Battalion (Composite).

violence from the local police, mightcommandeer a bus, remove thedriver, and take it to the gate nearestJacksonville, where the transit com-pany could retrieve it on the nextmorning. The white officer in com-mand at Montford Point, ColonelSamuel A. Woods, Jr., took steps toensure that the black Marines couldreturn safely to Montford Pointwithout risking arrest. He sent hisbattalion's trucks into town to pickup the men and assigned white non-commissioned officers from the staffat Montford Point to the militarypolice patrols that kept order in thetown. The NCOs detailed by ColonelWoods helped deter local authoritiesfrom making arbitrary arrests ofblack Marines. As black noncommis-sioned officers became available, oneof them accompanied each patrol,though unarmed and without au-thority to arrest or detain whiteMarines.

Although race also affected rela-tionships among Marines, especiallyduring the early months of the Mont-ford Point Camp, instances of the ra-cial harassment of black Marines be-came increasingly less frequent. Theimproved conditions resulted in partfrom Montford Point's isolation, butit also reflected the efforts of theAfrican-Americans to impress their

white fellow Marines. Obie Hall re-called that the men of MontfordPoint tried to look their sharpest, es-pecially when in the presence ofwhite Marines. "They really put thatchest out," he said. Pride in appear-ance had beneficial effects, for onewhite Marine remarked that,although he only saw blacks whenthey were on liberty because of thesegregation on Camp Lejeune, "theyalways looked sharp." The white mili-tary police remained unimpressed,however. They tended to share theracial attitudes of their civilian coun-terparts, and the persistent hostilitygenerated intense resentment amongthe African-American Marines.

Knowledge that they would haveto overcome racism to gain the rightto serve created a feeling of solidarityamong black Marines. At times, theycould invoke this unity to right awrong, as happened after the officerof the day at Montford Point, an-gered by what he considered raucousbehavior during a comedy beingshown at the camp movie theater,had the black audience take theirbuckets — these utilitarian posses-sions at the time were serving asseats—and put them over theirheads. The recently appointed blackdrill instructors reacted by orderingtheir Marines to clean the barracks

6

instead of attending a show beingstaged especially for them by blackperformers. When Colonel Woodsheard of the impromptu field day, heinvestigated, learned of the ill-considered action by the officer of theday, and made sure the African-Americans attended the perform-ance.

One incident painfully remindedthe African-Americans of theirsecond-class status in the MarineCorps, indeed throughout a JimCrow society. A boxing show stagedat the Montford Point Camp attract-ed a distinguished guest, MajorGeneral Henry L. Larsen, who hadtaken command of Camp Lejeune af-ter returning from the South Pacific.During an informal talk, he madewhat he considered a humorous re-mark, but his audience interpreted itas an insult. According to one of theblack Marines who was there, thegeneral said something to the effectthat when he returned from overseashe had seen women Marines and dogMarines, but when he saw "you peo-ple wearing our uniform," he knewthere was a war on. The off-handcomment may have served, however,to bring the men of Montford Pointeven closer together.

Oddly enough, a white officercame the closest to capturing the iso-

lation felt by blacks in segregatedNorth Carolina. Robert W. Troup, inpeacetime a musician and composerwho had played alongside black per-formers, accepted a wartime commis-sion and reported to Montford Point,where he made a lasting impression.One of the African-American Ma-rines, Gilbert H. Johnson, consideredhim a "topnotch musician, a very de-cent sort of officer;' and another,Obie Hall, described him as "thesharpest cat I've ever seen in my life."Bobby Troup's song "Jacksonville,"the unofficial anthem of men ofMontford Point, included the heart-felt plea:

Take me away from Jackson-ville, 'cause I've had my fill andthat's no lie.

Take me away from Jackson-ville, keep me away from Jack-sonville until I die. Jacksonvillestood still, while the rest of theworld passed by.While assigned to the 51st Defense

Battalion (Composite), the African-

American defense battalion autho-rized in 1942, Troup doubled asrecreation officer, organizing baseballand basketball teams, arranging theconstruction of sports facilities, andstaging shows using talent availableat Montford Point. Perhaps the mostpopular performer was Finis Hender-son, a private who had sung and tap-danced in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayerfilms. As the star of one of Troup'sshows, Henderson sang "Jacksonville"while stage hands threw bits ofbrown paper into the air flow froma pair of electric fans to simulate thedust blowing down the street of thatmuch-despised town. In December1944, Troup took command of theblack 6th Depot Company — the se-cond unit with that designation —which deployed to Saipan and han-dled supplies at the base there.

The training program at MontfordPoint, which signaled the first ap-pearance of blacks in Marine uni-

forms since the Revolutionary War,began with boot camp and had as itsultimate objective the creation of acomposite defense battalion. Thiscombat unit would be raciallysegregated, commanded by whiteofficers, and with an initial comple-ment of white noncommissionedofficers, who would serve only untilblack replacements became available.Colonel Woods had to start fromscratch, with no cadre of experiencedAfrican-Americans except for a hand-ful with prior service in the Army orNavy. When boot training began, thecolonel commanded both the campitself and the 51st Defense Battalion(Composite) being formed there.Lieutenant Colonel Theodore A.Holdahl — an enlisted veteran ofWorld War I who served as an officerin the Far East and CentralAmerica — had charge of recruittraining. Some two dozen whiteofficers, a number of them recentlycommissioned second lieutenants likeBobby Troup, and 90 white enlistedMarines, directed the training. Theenlisted men formed the Special En-listed Staff, which initially carriedout assignments that varied fromclerk or typist to drill instructor. TheMarine Corps screened the SpecialEnlisted Staff to exclude anyone op-posed to the presence of blacks in theranks. One of the Montford PointMarines suggested that, in the nor-mal pressures of boot camp, a break-down in the screening process couldhave doomed the program, for racialhostility would have reinforced theusual harassment visited on everyrecruit, white or black. "We wouldall have left the first week;' he joked."Some of us, probably, the first

7

In keeping with Marine Corpspolicy, Woods and Holdahl had toreplace the whites of the Special En-listed Staff with black noncommis-sioned officers as rapidly as possible.The command structure at MontfordPoint tried to identify the best of theAfrican-American recruits and place

Bobby Troup, a musician turned wartime Marine Corps officer, staged shows atMontford Point using talent such as Private Finis Henderson, a professional singerand dancer before enlisting, and Curtis Institute graduate Sgt Joe Wilder, not shown.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 6797

night:'

them on a fast track to positions ofresponsibility in boot camp and inthe battalion itself. The general clas-sification test, administered as a partof the initial processing, groupedthose who took the test into fivecategories, with the highest scores inCategory I, and afforded one tool forpredicting the ability of the new Ma-rines. Unfortunately, those black Ma-rines who administered the test andinterpreted the results were them-selves on-the-job trainees. Conse-quently, the test results could at timesprove misleading, with college gradu-ates sometimes showing up inCategories IV or even V. Drill in-structors, initially whites with vary-ing experience in the Marine Corps,had to rely on their own powers ofobservation to determine which ofthe African-American recruits hadthe aptitude to exercise effectiveleadership and master the necessarytechnology. Formal tests, written or

oral, provided a final winnowing ofthe candidates. The first promotions,to private first class, took place ear-ly in November 1942, a month be-fore the men selected to sew on theirsingle stripe had completed bootcamp.

The problem of classifying recruitsdemonstrated that the MontfordPoint Camp required skilled adminis-trators. Creating an administrativeinfrastructure proved difficult, for thecomparatively few volunteers whostepped forward in the summer andfall of 1942 included few clerks andtypists. Enough African-Americanrecruits would have to learn the mys-teries of Marine Corps administra-tion to fill the necessary billets, butracial segregation prevented themfrom taking courses alongside whites.For the present, white instructorswould teach administrative subjectsat Montford Point, until black Ma-

them along. When tackling the morecomplex subjects, like optical firecontrol or radar, the African-Americans attended courses offeredby the Army at nearby Camp Davis,North Carolina, and elsewhere.

Lacking a cadre of black veterans,the Marine Corps had to advance thebest of the African-American recruitsinto the ranks of noncommissionedofficers so as to achieve the goal ofa segregated defense battalion com-manded by white officers but with nowhite enlisted men in any capacity.The promotion of black Marines de-pended on ability, as revealed by theinitial classification tests, ratings fromsuperiors, the results of formal ex-aminations, and the existence ofvacancies that would not violate poli-cy by placing a black Marine incharge of whites. As the number ofAfrican-American Marines increasedand training activity accelerated,

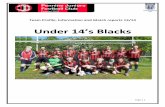

These Marines of the first platoon to enter recruit training atMontford Point were promoted to private first class a monthbefore they completed boot camp and became assistant drill

instructors. From left are Mortimer A. Cox; Arnold R. Bostick;Edgar R. Davis, Jr.; Gilbert H. "Hashmark" Johnson and EdgarR. Huff (their drill instructors); and Charles E. Allen.

rines could master the skills and pass some of the recently promoted pri-

8

Two of Those Who Succeededwo of the black Marines who overcame everychallenge, Edgar R. Huff and Gilbert H. Johnson,became legends among the men of Montford Point.

Both grew up in Alabama, and ultimately would marrytwin sisters, but their military backgrounds could not havebeen more different. Huff's service began when he joinedthe Marine Corps, but Johnson had served in both theArmy and Navy before he reported to Montford Point.

Gilbert H. Johnson earned the nickname "Hashmark" be-cause he wore on the sleeve of his Marine Corps uniformthree of the diagonal stripes, called hashmarks, indicatingsuccessful previous enlistments. Born in Mt. Hebron,Alabama, in 1905, he joined the Army in 1923 and servedtwo three-year hitches with a black regiment, the 25th In-fantry. In 1933, he enlisted in the Naval Reserve as a messattendant, serving on active duty in officers' messes at var-ious installations in Texas. He entered the regular Navy inMay 1941 and had become a steward second class by 1942when he heard that the Marine Corps was recruitingAfrican-Americans.

With infantry experience ranging from company clerkto mortar gunner and squad leader, Johnson felt he wasideally suited to become a Marine. As regulations required,he applied to the Secretary of the Navy, via the Comman-dant of the Marine Corps, for a discharge from the Navyin order to join the Marines. He received the necessary per-mission and reported to Montford Point on 14 November1942, still wearing his steward's uniform.

As he anticipated, he possessed vitally needed skills thatresulted in his being chosen as an assistant drill instructorand later a drill instructor. He ended up supervising thevery platoon in which he had started his training. Lookingback on his days as a DI, Johnson conceded that he wassomething of an "ogre" on the drill field. "1 was a stern in-structor;' he said, "but I was fair:' He sought, with unswerv-ing dedication, to produce "in a few weeks, and at mosta few months, a type of Marine fully qualified in everyrespect to wear that much cherished Globe and Anchor:'In January 1945, he became sergeant major of the Mont-ford Point Camp and in June of that year joined the 52dDefense Battalion on Guam, also as sergeant major, remain-

Gilbert H. "Has Jiniark" JohnsonDepartment of Defense Photo (USMC) 5344

9

ing in that assignment until the unit disbanded in 1946.His subsequent career included service during the Korean

War. He retired in 1955 after completing a tour of duty asFirst Sergeant, Headquarters and Service Company, 3d Ma-rines, 3d Marine Division. He died in 1972. Two years af-terward, the Marine Corps paid tribute to hisaccomplishments by redesignating the Montford PointCamp as Camp Gilbert H. Johnson.

Edgar R. Huff enlisted in the Marine Corps in June 1942and underwent training at the new Montford Point Camp."1 wanted to be a Marine," he said years later, "because Ihad always heard that the Marine Corps was the toughestoutfit going, and I felt I was the toughest going, so I want-ed to be a member of the best organization:' His toughnessand physical strength had served him well while a cranerigger for the Republic Steel Company in Alabama City,near his home town of Gadsden, Alabama.

Huff reported for duty at a time when the MontfordPoint operation desperately needed forceful and intelligentAfrican-Americans, with or without previous military ex-perience, to take over from the white noncommissionedofficers of the Special Enlisted Staff. Since he possessed thevery qualities that the Marine Corps was seeking, he at-tended a drill instructor's course, served briefly as an as-sistant to two white drill instructors, took over a platoonof his own, and soon assumed responsibility for all the DIsat Montford Point He made platoon sergeant in Septem-ber 1943, gunnery sergeant in November of that year, andin June 1944 became first sergeant of a malaria controldetachment at Montford Point. He went overseas sixmonths later as the first sergeant of the 5th DepotCompany—the second wartime unit with thatdesignation — served on Saipan, saw combat on Okinawa,and took part in the occupation of North China.

Discharged from the Marine Corps when the war end-ed, he spent a few months as a civilian and then reenlist-ed. He saw service in the Korean War and the Vietnam War.During his second tour of duty in Vietnam, he was Ser-geant Major, III Marine Amphibious Force, the principalMarine Corps command in Southeast Asia. He retired in1972 while Sergeant Major, Marine Corps Air Station, NewRiver, North Carolina, and died in May 1994.

Edgar R. Huff

Ghazlo, instructor in unarmed combat,

yates first class, corporals, and ser-geants became assistant drillinstructors at the Montford Pointboot camp, replaced the white drillinstructors, or joined the defense bat-talion when it began taking shape.The rapid expansion of the noncom-missioned ranks thrust many of thenewly promoted black Marines intosink-or-swim assignments in whichthey not only kept their heads abovewater but made rapid progressagainst the current.

A few of the black volunteers be-sides Gilbert Johnson had previousmilitary experience; others had spe-cial ability or the potential for leader-ship. John T. Pridgen, for instance,had served in the 10th Cavalry be-fore the war, and George A. Jacksonhad been an officer in the peacetimeArmy reserve. At a time when fewwhites and fewer blacks held degrees,the Montford Point Marines includedseveral college graduates, amongthem Charles F. Anderson andCharles W. Simmons. The talents ofArvin L. "Tony" Ghazlo proved asvaluable as they were rare, for as acivilian he had given lessons in jujit-su. With the help of another black

disarms his assistant, PFC Ernest Jones.

Marine, Ernest "Judo" Jones, Ghazlotaught unarmed combat at MontfordPoint. Men like these replaced mem-bers of the Special Enlisted Staff inthe training process, a transition allbut completed by the end of April1943, and became noncommissionedofficers in the 51st Defense Battalionand the other units formed from thetide of draftees.

Thanks to the use of the SelectiveService System as the normal sourceof recruits, the nature of the programat Montford Point was changing. Asingle defense battalion could not ab-sorb the influx of blacks into the Ma-rine Corps. Consequently, Secretaryof the Navy Knox authorized a Ma-rine Corps Messman Branch and thefirst of 63 combat support com-panies — either depot or ammunitionunits—as well as a second defensebattalion, the 52d. An expansion ofthe Montford Point Camp began, asthe Marine Corps prepared to houseanother thousand blacks there. TheHeadquarters and Service Company,Montford Point Camp, came into ex-istence on 11 March 1943, and at thesame time, the 51st Defense Battal-ion (Composite) provided the

10

nucleus for the Headquarters Com-pany, Recruit Depot Battalion.Colonel Woods retained command ofthe camp, entrusting the defense bat-talion to Lieutenant Colonel W. Ba-yard Onley, a graduate of the NavalAcademy whose most recent assign-ment had been Regimental ExecutiveOfficer, 23d Marines. LieutenantColonel Holdahl continued to exer-cise control over boot training ascommander of the new recruit bat-talion. On 1 April, Captain Albert0. Madden, a veteran of World WarI who, as a civilian, had operatedrestaurants in Albany, New York,took command of the new MessmanBranch Battalion; on the 13th, whenthe Messman Branch became theStewards' Branch, the name of Mad-den's battalion changed to reflect theredesignation. The growth of theMontford Point operation requiredadditional housekeeping support,much of it obtained from the riflecompany of the 51st Defense Battal-ion, after a modified table of organi-zation disbanded the infantry unit inthe summer of 1943.

The proliferation of African-American units and the expansion ofactivity at Montford Point interferedwith the organization and training ofthe 51st Defense Battalion (Compo-site) by making demands on the poolof black noncommissioned officersthat Woods, Holdahl, and theshrinking Special Enlisted Staff hadassembled. The first, and for a timethe only, Marine Corps combat unitto be manned by blacks found itselfin competition with another defensebattalion, the new combat supportoutfits (depot and ammunition com-panies), the Stewards' Branch, and,as before, the recruit training func-tion. So thinly spread was theAfrican-American enlisted leadershipthat the same individuals might servein a succession of units. "Hashmark"Johnson, a DI in boot camp, ended

National Archives Photo 127-N-5334During a demonstration while training at Montford Point, Cpl Arvin L. "Tony"

The Stewards' Branch

In organizing the Stewards' Branch. the Marine Corps followed the ex-ample of the Navy, which had begun before World War I to segregatethe enlisted force by channeling blacks away from combat or technical

specialties and making them stewards or mess attendants. Once Captain Mad-den's formal courses began producing enough graduates, the Stewards' Branchprovided cooks and attendants for officers' messes in large-unit headquart-ers. Combat experience would prove that duty in the Stewards' Branch couldbe as dangerous as any other assignment open to blacks. On Saipan, for ex-ample, two members of the branch suffered wounds when the enemy shelledthe headquarters of the 2d Marine Division. On Okinawa, where stewardsroutinely volunteered as stretcher bearers, Steward 2d Class Warren N.McGrew, Jr., was killed and seven others sustained wounds, one of them,Steward's Assistant 1st Class Joe N. Bryant, being wounded twice.

The Stewards' Branch did not include the cooks and bakers in black units.Segregation required that African-Americans take over these specialties, be-ginning at the Montford Point Camp. In January 1943, Jerome D. Alcorn, OttoCherry and Robert T. Davis became the first to cross the divide between as-sistant cook (at the time the equivalent of a corporal) and field cook (sergeant).

up with the 52d Defense Battalion.Similarly, Edgar Huff, also a DI,moved on to other assignments, in-cluding first sergeant of one of thecombat service support companies.

The 51st had attained only half itsauthorized strength on 21 April,when a new commanding officer,Lieutenant Colonel Floyd A.Stephenson, took over from Lieu-tenant Colonel Onley. Stephenson, incommand of a defense battalion atPearl Harbor when the Japanese at-tacked, later declared that he "had nobrief for the Negro program in theMarine Corps;' since he hailed fromTexas, "where matters relating toNegroes are normally given theclosest critical scrutiny;' a euphemis-tic description of Jim Crow. He was,in short, the product of a segregatedsociety, but despite his background,he tackled his new assignment withenthusiasm and skill. African-Americans, he soon discovered,could learn to perform all the dutiesrequired in a defense battalion.

By the end of 1942, the nature ofthe defense battalion had begunchanging. Already the Marine Corpshad stricken light tanks from the ta-ble of organization and equipment,and, as close combat became increas-

ingly less likely, the rifle companyand the pack howitzers followed thearmor into oblivion. Emphasis shift-ed from repulsing amphibious land-ings to defending against Japanese airstrikes and hit-and-run raids by war-ships. In June 1943, the qualifier"Composite" disappeared from thedesignation of the 51st Defense Bat-talion, the 155mm battery became agroup, and the machine gun unitevolved into the Special WeaponsGroup, with 20mm and 40mmweapons, as well as machine guns.A month later, the 155mm Group be-came the Seacoast Artillery Group,and the 90mm outfit, with its search-lights, the Antiaircraft ArtilleryGroup. No further changes tookplace before the battalion wentoverseas.

As this evolution in organizationand weaponry began, Stephenson setto work building a segregated battal-ion with the African-American Ma-rines available to him. They hadundergone classification testing atMontford Point and been groupedaccording to their scores. Normallymen in Category IV would at best at-tain the rank of corporal, whereasthose in Categories III through Igenerally had the aptitude for higher

11

rank, though no black could aspire toofficer training. Since classificationscores tended to be fallible, Stephen-son and his officers had to rely oninstruction, observation, and evalu-ation as they tried to create a cadreof black noncommissioned officers innine months or less.

Each group within the battalion —at the time 155mm artillery, 90mmantiaircraft artillery, and specialweapons—maintained standing ex-amination boards, which includedthe group commander. The officersand noncommissioned officersrecommended candidates for promo-tion, who then appeared before thegroup's examining board. The firsttest in this series, for promotion toprivate first class, was a written ex-amination usually administered dur-ing or shortly after boot camp, butthe others, given during unit train-ing, consisted of 25 to 30 questionsanswered orally. The names of thosewho survived the screening went tothe battalion commander whomatched candidates with openings."Many qualified men waited frommonth to month:' Stephenson re-called, although in six or eight in-stances over perhaps nine months "anespecially meritorious, mature manwas advanced two grades on succes-sive days to place especially talentedleaders in positions of responsibili-ty" Just as "Hashmark" Johnson andEdgar Huff had advanced rapidlywithin the recruit training operation,Obie Hall became a platoon sergeantwithin six months of joining the bat-talion.

The tempo of training picked upthroughout the summer and fall of1943, as African-American noncom-missioned officers replaced moreof the white enlisted men who hadtaught them to handle weapons andlead men in combat. On 20 August,the 51st Defense Battalion sufferedits first fatality. During a disembar-kation exercise, while the Marines ofthe 155mm Artillery Group scram-bled down a net draped over a

The Stewards' Branch

I n organizing the Stewadd Branch, the Marine Corps followed the ex- ample of the Navy, which had begun befom World War I to segregate the enlisted force by channeling blacks away from combat or technical

specialties and malsing them stmads or mess attendants. Ona Captain Mad- den's formal cou18e8 began producing enough graduates, the Stewadd Branch provided amks and attendants for officed messes in largeunit headquart- ers. Combat experienoe would prove that duty in the Skwards' Branch could be as dangerous as any other assignment open to blacks. On Saipan, for ex- ample, two members of the branch suffered wounds when the enemy shelled the headquartem of the M Marine Division. On O b w a , where stewards routinely volunteered as stretcher bearem, Steward 2d Class Warren N. McGrew, Jr., was killed and seven others sustained wounds, one of theq, Steward's Adstant lst Class Joe N. Bryant, being wounded twioe. The Stewards' Branch did not include the cooks and bakers in black units.

Segregation required that African-Americans take over these specialties, be- ginning at & Montford Point Camp. In January 1943, Jmme D. Alcom, Otto Cherry, and Robert T. Davis became the first to goss the divide between as- sistant oook (at the time the equivalent of a corporal) and field mok (seqeant).

up with the 52d Defense Battalion. Similarly, Edgar Huff, also a DI, moved on to other assignments, in- cluding first sergeant of one of the combat service support companies.

The 51st had attained only half its authorized strength on 21 April, when a new commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Floyd A. Stephenson, took over from Lieu- tenant Colonel Onley Stephenson, in. command of a defense battalion at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese at- tacked, later declared that he "had no brief for the Negro program in the Marine Corps," since he hailed from Texas, "where matters relating to Negroes are normally given the closest critical scrutiny," a euphemis- tic description of Jim Crow. He was, in short, the product of a segregated society, but despite his background, he tackled his new assignment with enthusiasm and skill. African- Americans, he soon discovered, could learn to perform all the duties required in a defense battalion.

By the end of 1942, the nature of the defense battalion had begun changing. Already the Marine Corps had stricken light tanks from the ta- ble of organization and equipment, and, as close combat became increas-

ingly less likely, the rifle company and the pack howitzers followed the armor into oblivion. Emphasis shift- ed from repulsing amphibious land- ings to defending against Japanese air strikes and hit-and-run raids by war- ships. In June 1943, the qualifier "Composite" disappeared from the designation of the 51st Defense Bat- talion, the 155mm battery became a group, and the machine gun unit evolved into the Special Weapons Group, with 20mm and 40mm weapons, as well as machine guns. A month later, the 155mm Group be- came the Seacoast Artillery Group, and the 90mm outfit, with its search- lights, the Antiaircraft Artillery Group. No further changes took place before the battalion went overseas.

As this evolution in organization and weaponry began, Stephenson set to work building a segregated battal- ion with the African-American Ma- rines available to him. They had undergone classification testing at Montford Point and been grouped according to their scores. Normally men in Category IV would at best at- tain the rank of corporal, whereas those in Categories I11 through I generally had the aptitude for higher

rank, though no black could aspire to officer training. Since classification scores tended to be fallible, Stephen- son and his officers had to rely on instruction, observation, and evalu- ation as they tried to create a cadre of black noncommissioned officers in nine months or less.

Each group within the battalion- at the time 155mm artillery, 90mm antiaircraft artillery, and special weapons -maintained standing ex- amination boards, which included the group commander. The officers and noncommissioned officers recommended candidates for promo- tion, who then appeared before the group's examining board. The first test in this series, for promotion to private first class, was a written ex- amination usually administered dur- ing or shortly after boot camp, but the others, given during unit train- ing, consisted of 25 to 30 questions answered orally. The names of those who survived the screening went to the battalion commander who matched candidates with openings. "Many qualified men waited from month to month," Stephenson re- called, although in six or eight in- stances over perhaps nine months "an especially meritorious, mature man was advanced two grades on succes- sive days to place especially talented leaders in positions of responsibili- ty." Just as "Hashmark Johnson and Edgar Huff had advanced rapidly within the recruit training operation, Obie Hall became a platoon sergeant within six months of joining the bat- talion.

The tempo of training picked up throughout the summer and fall of 1943, as African-American noncom- missioned officers replaced more of the white enlisted men who had taught them to handle weapons and lead men in combat. On 20 August, the 51st Defense Battalion suffered its first fatality. During a disembar- kation exercise, while the Marines of the 155mm Artillery Group scram- bled down a net draped over a

wooden structure representing theside of a transport, Corporal GilbertFraser, Jr., slipped, fell into a land-ing craft in the water below, andsuffered injuries that claimed his life.In memory of the 30-year-old gradu-ate of Virginia Union College, theroad leading from Montford PointCamp to the artillery range becameFraser Road.

Although the men of the 51st De-fense Battalion had to assume theresponsibilities of squad leaders andplatoon sergeants even as theylearned to care for and fire the bat-talion's weapons, the black Marinesmet this challenge, as they demon-strated in November 1943. Duringfiring exercises — while Secretaryof the Navy Knox, General Holcomb,and Colonel Johnson of the SelectiveService System watched — an Afri-can-American crew opened fire witha 90mm gun at a sleeve target beingtowed overhead and hit it within just60 seconds. Lieutenant ColonelStephenson, listening for the Com-

mandant's reaction, heard him say "1think they're ready now" Few othercrews in the 51st could match thisperformance, and a number of themclearly needed further training, assome of their officers warned at thetime. The four days of firing at theend of November could not berepeated, however, for the unitwould depart sooner than original-ly planned on the first leg of a jour-ney to the Pacific.

Where in the Pacific area wouldthat journey end? Marine MajorGeneral Charles F. B. Price, in com-mand of American forces in Samoa,had already warned against sendingthe African-Americans there. Hebased his opinion on his interpreta-tion of the science of genetics. Thelight-skinned Polynesians, whom heconsidered "primitively romantic" bynature, had mingled freely withwhites to produce "a very high classhalf caste;' and liaisons with Chinesehad resulted in "a very desirable type"of offspring. The arrival of a battal-

12

ion of black Marines, however,would "infuse enough Negro bloodinto the population to make the is-land predominately Negro" andproduce what Price considered "avery undesirable citizen:' Better, thegeneral suggested, to send the 51stDefense Battalion to a region popu-lated by Melanesians, where the"higher type of intelligence" amongthe African-Americans would notonly "cause no racial strain" but also"actually raise the level of physicaland mental standards" among theblack islanders. After the general for-warded his recommendation to Ma-rine Corps headquarters, though notnecessarily because of his reasoning,two black depot companies that ar-rived in Samoa during October 1943were promptly sent elsewhere.

Whatever its ultimate destination,the 51st Defense Battalion started offto war early in January 1944, and bythe 19th, most of the unit—less 400men transferred to the newly or-ganized 52d Defense Battalion — and

Photo courtesy of Edgar R. Huff

The creation of a cadre of African-American noncommissioned Corps needed. Some especially meritorious mature men wereofficers brought rapid promotion to those who had the abili- advanced two grades on successive days to place talented lead-ties, as Edgar Huff, shown here as a first sergeant, the Marine ers in positions of responsibility in field organizations.

the bulk of its gear were moving byrail toward San Diego. On that day,while Stephenson supervised theloading of the last of the 175 freightcars assigned to move the unit'sequipment, a few of the black Ma-rines waiting to board a troop trainbegan celebrating their imminentdeparture by downing a few beerstoo many at the Montford Pointsnack bar, which lived up to the nick-name of "slop chute;' universally ap-plied to such facilities. The militarypolice, all of them white, cut off thesupply of beer by closing the placeand forcing the blacks to leave. Onceoutside, the men of the battalionmilled about and began throwingrocks and shattering the windows ofthe snack bar. Again the militarypolice intervened, one of them firingshots into the air to disperse, the un-ruly crowd. Some of the black Ma-rines fled into the nearby theater,which the military police promptlyshut down. At this point, someonefired 15 or 20 shots into the air fromthe vicinity of a footbridge linking

the Montford Point Camp withCamp Knox, the old CCC facility,where those members of the 51st stillin the area had their quarters. A straybullet wounded a drill instructor,

Corporal Rolland W. Curtiss, whowas leading his platoon on a nightmarch. Despite the injury and amomentary panic among his recruits,the corporal brought his men safely

National Archives Photo 127-N-9007

A fall during an exercise comparable to this killed Cpl Gilbert Fraser, Jr., the first fatality suffered by the Montford Point Marines.

A 90mm gun crew practices loading at Montford Point in preparatation for itsdeployment overseas to the Pacific and eventual combat operations in the war.

13

of its men, by Colonel Curtis W.LeGette. The new commanding of-ficer, a native of South Carolina anda Marine since 1910, had fought inFrance during World War I and beenwounded at Blanc Mont in October1918. His most recent assignmentwas as commanding officer of the 7thDefense Battalion in the Ellice Is-lands. Not only was LeGette replac-ing a popular commander, he got offto a bad start. In his first speech tothe assembled battalion, he made themistake of invoking the phrase "youpeople"— frequently used by officerswhen addressing their white units —but in this instance his choice of "you"instead of "we" convinced some of theAfrican-Americans that their newcommanding officer considered themoutsiders rather than real Marines.

back to their barracks.Although one rifle assigned to the

battalion showed signs of firing andanother appeared to have beencleaned with hair oil, perhaps to dis-guise recent use, neither could belinked to a specific Marine. Recordsproved to be in disarray, with serialnumbers copied incorrectly and in-dividuals in possession of weaponsother than the ones they were sup-posed to have. The breakdown of ac-countability impeded a hurriedinvestigation by Stephenson and fourof his officers and prevented themfrom determining who had fired theshots.

The mix-up in weapons resultedfrom the confusion of the move and

the inexperience of recently promot-ed junior noncommissioned officers,who failed to ride herd on their men.Colonel Woods witnessed the resultsof this failure when he inspected thevacated quarters and found "a filthyand unsanitary area:' Indeed, one ofthe noncoms later admitted to sim-ply assuming that "someone is goingto pick it up," much as parents wouldmake sure that nothing of value re-mained behind when a family movedto a new house.

The failure in discipline that at-tended the departure of the 51stDefense Battalion from MontfordPoint led to the replacement of Lieu-tenant Colonel Stephenson, who hadbuilt the unit and earned the respect

14

Because they were replacing the7th Defense Battalion, LeGette'sformer command, already estab-lished in the Ellice group, the blackMarines turned in all the heavyequipment they had brought withthem from Montford Point andboarded the merchantman SSMeteor, which sailed from San Die-go on 11 February 1944. Less than amonth had elapsed since the last trainleft North Carolina on the first legof the journey to war. While Meteorsteamed toward the Ellice Islands, the51st Defense Battalion divided intotwo components. Detachment A, ledby Lieutenant Colonel Gould P.Groves, the executive officer, wouldgarrison Nanomea Island, while therest of the battalion, under ColonelLeGette, manned the defenses ofFunafuti and nearby Nukufetau. By27 February, the 51st completed therelief of the 7th Defense Battalion,taking over the white unit's weaponsand equipment. One of the African-American Marines, upon first ex-periencing the isolation that sur-rounded him, suggested that thedeparting whites "were never so glad

National Archives Photo 127-N-9507A gun crew of the 51st Defense Battalion trains for overseas deployment.