The Level Of Uric Acid In Preeclampsia Women in Wad-Medeni ...

Transcript of The Level Of Uric Acid In Preeclampsia Women in Wad-Medeni ...

1

Measurement of Serum Uric Acid, Calcium and Phosphorus in

Preeclamptic Pregnant Women attending Wad Medani Obstetrics and

Gynecology Teaching Hospital, Gezira State, Sudan (2016)

By

Abuagla Albasheer Alshareef

(B.Sc in Clinical Chemistry, University of Omdurman Ahlia 1993)

A Dissertation

Submitted to university of Gezira inPartial Fulfillment of the

Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Science in

Clinical Chemistry

Department of Clinical Chemistry

Faculty of medical laboratory sciences

University of Gezira

2017

Measurement of Serum Uric Acid, Calcium and Phosphorus in

Preeclamptic Pregnant Women attending Wad Medani Obstetrics and

Gynecology Teaching Hospital, Gezira State, Sudan (2016)

Abuagla Albasheer Alshareef

2

Supervision committee:

Name Position Signature

Dr. Shams Eldein Mohammed Main supervisor ……………………..

U. Abubakr Hassan Atta

Almawla

Co-supervisor ……………………..

Date: 12/1/2017

3

Measurement of Serum Uric Acid, Calcium and Phosphorus in

Preeclamptic Pregnant Women attending Wad Medani Obstetrics and

Gynecology Teaching Hospital, Gezira State, Sudan (2016)

Abuagla Albasheer Alshareef

Examination committee:

Name Position Signature

Dr. Shams Eldein Mohammed Ahmed Chairman ………………

Dr. Osama Abdelrahman Ahmed External examiner ………………….

Dr. Manal Ali Ahmed Babiker Internal examiner ………………....

Date: 12 /1/2017

4

Declaration

I authorized that my dissertation “Evaluation of uric acid, calcium and phosphorus in

preeclampsia pregnant women attending Wad Medani Maternity Teaching Hospital”

submitted by me, under the supervision of Dr. Shams Eldein Mohammed and U. Abubakr

Hassan Atta Almawla for the partial fulfillment for the award of Master degree in Medical

Laboratory Sciences in Clinical Chemistry. University of Gezira Faculty of Medical

Laboratory Sciences Department of Clinical Chemistry; Wad-Medani, Sudan and this is

original and it was not submitted in part or in full, in any printed or electronic means, and

is not being considered elsewhere for publication.

Name and Signature of Candidate:

Abuagla Albasheer Alshareef…………………………….

Date:12 /1 /2017

5

Dedication

First and final thanks to Allah

To my family; Thanks for believing me, for allowing me to further studies.

To my parents;

Thanks for unconditional support with my studies. I’m honored to have you as my parents.

To my wifes;

Thank you for allowing me a chance to prove and improve myself all my walks of life.

I love you.

To my friends and all people support me.

And of course, all my colleagues in master program Batch (1)

If I forgot anyone, please don’t ever doubt my dedication and love for ALL.

6

Acknowledgements

I extend my sincere thanks and gratitude to Allah for helping me in all my life.

Also thanks to to my supervisors Dr. Shams Eldein Mohamed Ahmed and U. Abubakr

Hassan Atta Almawla whom follow and support me in all stages of this dissertation.

Special thanks and appreciation to all peoples who helped me in completing this

dissertation and provided me with information and Also, thanks to my friends Kheir

Alseid, Mubark Alshafea, Mohammed Yousif and Alfadil Omer whom help me and

encourage me alot.

Special thanks to nursing staff in Wad Medani Gynecology Teaching Hospital whom help

me in the collection of the samples.

Finally I never forgot all, whom help me and support me in my study research and not

mentioned here.

Thanks to all participants whom approved to participate in this study.

7

Measurement of Serum Uric Acid, Calcium and Phosphorus in

Preeclamptic Pregnant Women attending Wad Medani Obstetrics and

Gynecology Teaching Hospital, Gezira State, Sudan (2016)

Abuagla Albasheer Alshareef

Abstract

Preeclampsia is a multi-system disorder that can affect every maternal organ

predominantly the cardio-vascular system, kidneys, brain and liver. Preeclampsia is

characterized by development of high blood pressure and proteinuria. It affects 5-8% of all

pregnancies and is a major contributor to maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. This

study was aimed to estimate serum uric acid, calcium and phosphorus in preeclamptic

pregnant women. A total of 100 volunteer pregnant women were participated for this

study. Fifty (50%) of them were preeclamptic pregnant women as cases study and 50

(50%) were healthy pregnant women as control group. Their ages ranged from 18 year to

42 year old. All cases had proteinuria (16% with ++ and 84% +++). 18% at second

trimester while 82% at third trimester. 4% with history of preeclampsia, 2% had family

history of preeclampsia while 94% attacked at first pregnancy. 18% were obese and 2%

with comorbidity. The samples tested for Uric acid, Calcium and Phosphorus by using

Biosystem A25 automation system. Data analysed by using (SPSS) computer program

version 18. In this study we compared the means of Uric acid, Calcium and Phosphorus

between cases and controls. The results showed highly significant difference in Uric acid

level (p. value 0.000), while there were no significant difference between cases and

controls in Calcium (p. value 0.050) and phosphorus (p. value 0.060). The study

recommended that estimation of uric acid for preeclamptic pregnant women must be done

routinely.

8

الكالسيوم والفسفور وسط الحوامل المصابات بالتسمم الحملي قياس تركيز مصل حامض البوليك،

(2016اللواتي يترددن على مستشفى النساء والتوليد التعليمي ودمدني، ولاية الجزيرة، السودان )

أبوعاقلة البشير الشريف

ملخص الدراسة

لكلى والدماغ. تتميز بالإرتفاع في التسمم الحملي هي إضطرابات تؤثر على عدة أنظمة في جسم الأم مثل القلب، الكبد، ا

% من الحوامل وتعتبر سبب أساسي في وفيات الأجنة والأمهات. هدفت 8-5ضغط الدم والبروتين البولي والتي تصيب

هذه الدراسة الى قياس حامض البوليك، الكالسيوم والفسفور في الحوامل المصابات بالتسمم الحملي اللواتي يترددن

. تطوعت لهذه الدراسة2016والتوليد التعليمي بودمدني في الفترة ما بين أبريل وحتى يونيو على مستشفى النساء

%( كانوا حوامل في حالة التسمم 50من الحالات ) 50منهن مصابات بالتسمم الحملي كحالات. 50امرأة حامل. 100

عام. جميع 42-18أعمارهن بين %( حوامل أصحاء أخذن كعينات ضابطة.تتراوح50من الحالات ) 50الحملي بينما

% 18% +++ (، 86% كان تقدير البروتين في البول ++ بينما 16حالات التسمم الحملي لديهن بروتين في البول )

% لديهن تاريخ 2% لديهن تاريخ مرضي بالتسمم الحملي، 4% في فترة الحمل الثالثة. 82في فترة الحمل الثانية بينما

% لديهن أمراض متزامنة. تم قياس 2% يعانين من السمنة و18% في الحمل الأول. 94ينما أسري بالتسمم الحملي ب

وتم تحليل البيانات بواسطة برنامج الحزم 25حمض البوليك، الكالسيوم والفسفور بإستخدام جهاز البيوسيستم إي

الكالسيوم والفسفور بين الحالات (. تم مقارنة متوسطات حمض البوليك،18الإحصائية للعلوم الإجتماعية )إصدار رقم

( بينما 0.000والعينات الضابطة وأظهرت النتائج وجود فرق معنوي في تركيز حمض البوليك )القيمة المعنوية

( وتركيزالفسفور 0.050لاتوجد فروقات معنوية بين الحالات والعينات الضابطة في تركيز الكالسيوم )القيمة المعنوية

(. أوصت الدراسة بإجراء إختبار حمض البوليكللحوامل المصابات بالتسمم الحملي كتحليل 0.060)القيمة المعنوية

روتيني.

.

9

Table of contents

Title Page

Declaration i

Dedication ii

Acknowledgment iii

Abstract English iv

Abstract Arabic v

Table of content vi

List of table vii

List of figure viii

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

Introduction 1

1.2 Justification 3

1.3 Objectives 4

1.3.1 General Objective 4

1.3.2 Specific Objectives 4

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATRE REVIEW

2.1 Hypertension 5

2.1.1 Preeclampsia 6

2.1.1.1 Eclampsia 7

2.1.1.2 Criteria for preeclampsia 8

2.1.3 Chronic hypertension 8

2.1.5 Gestational hypertension 9

2.1.6 Risk factors 9

2.1.7 Hyperuricemia 12

2.1.8 Proteinuria 12

2.2 Bio chemical tests 13

2.2.1Criteria for the diagnosis of preeclampsia 14

2.2.2 Screening for Proteinuria 14

10

2.2.3 Quantifying Protein Excretion 15

CHAPTER THREE: MATERIAL AND METHODS

3.0 Type of the study 17

3.1 Study area 17

3.2 Study population and samples collection 17

3.2.1 Inclusion Criteria 17

3.2.2Exclusion criteria 17

3.3Methods 17

3.4 Uric acid, calcium and phosphorus investigation: 17

3.5 Ethical consideration 18

3.6 Data analysis 18

CHAPTER FOUR: RESULT and DISCUSSION

4.1 Results: 19

4.2 Discussion 23

CHAPTER FIVE:CONCLUSION AND

RECOMMENDATIONS

5.1 Conclusion 25

5.2 Recommendations 25

Reference 26

11

List of tables Title Page

4.1 Comparison of means of uric acid among cases and controls 20

4.2 Comparison of means of calcium among cases and controls 21

4.3 Comparison of means of phosphorus among cases and controls 22

13

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION Pre-eclampsia, is one of the most common complications of pregnancy, it affects

approximately 10% of births (Robillandet al., 2003). It is a leading cause of maternal and

perinatal mortality worldwide (Duley, 2009). Although, the exact etiology of pre-

eclampsia is not yet known, many risk factors have been demonstrated such as low

education, primiparity, family history of hypertension, obesity, younger and advanced

maternal age, and ethnicity (Conde and Belizán, 2000; Leeet al.,2000; Roberts et al.,2003;

Sibaiand Kupferminc,2005; Adeyinkaet al.,2010). Therefore, if women at risk of pre-

eclampsia are identified on the basis of epidemiological and clinical risk factors, the

awareness can be raised, this will facilitate to make earlier diagnoses and predict which

patients are more likely to develop pre-eclampsia and can help to monitor patients as

well.Recently, it has been shown that placenta previa is associated with low frequencies of

pre-eclampsia and low maternal blood pressure (Kiondoet al.,2012). However, there are

few published studies – with inconsistent findings – on the association between placenta

previa and pre-eclampsia. While some studies reported the protective effects, other studies

did not show any associations, slightly increase in the incidence and significantly elevated

incidence pre-eclampsia in placenta previa (Little and Friedman, 1964; Brenneret al.,1978;

Newtonet al.,1984; Ananthet al.,1997; Hasegawaet al.,2011).The current study was

conducted at Medani Maternity Hospital in Central Sudan to investigate the potential risk

factors for pre-eclampsia including placenta previa. The data obtained is very useful for

the health planners, health providers, and augments the previous research on pre-

eclampsia in Sudan (Bakheitet al., 2009, 2010; Elhassanet al.,2009; Adamet

al.,2011).Hypertensive disorders are one of the most important causes of perinatal and

maternal mortality and morbidity in both developing and developed countries. Pre-

eclampsia is a multisystem disorder that complicates about 3–8% pregnancies. The

incidence is high in developing countries due to hypoproteinemia, malnutrition and poor

obstetric facilities. Overall, 10–15% of maternal deaths are directly associated with pre-

eclampsia and eclampsia. (Carty et al.,2010) The risk of pre-eclampsia is two to five times

more in women with maternal history of this disorder. Depending on ethnicity, the

incidence of pre-eclampsia ranges from 3% to 7% in healthy nulliparas (Sibaiet al.,2005)

14

and 1% to 3% in multiparas(Uzanet al.,2011).Pre-eclampsia is a complex, pregnancy-

specific hypertensive syndrome of reduced organ perfusion related to vasospasm and

activation of the coagulation cascade affecting multiple systems. The nervous system is

commonly affected and is a cause of significant morbidity and death in these women (Am

J Obstetric Gynecol, 2000). The major risk to the fetus results from decreased placental

perfusion leading to decreased blood supply of oxygen and nutrients necessary for fetal

growth and wellbeing. Due to lack of facilities, the patient in a rural setting usually

presents late.Hyperuricemia is a common finding in preeclamptic pregnancies evident

from early pregnancy. (Powers et al.,2006) Despite the fact that elevated uric acid often

pre-dates the onset of clinical manifestations of preeclampsia, hyperuricemia is usually

considered secondary to altered kidney function. Increased serum uric acid is associated

with hypertension, renal disease and adverse cardiovascular events in the non-pregnant

population and with adverse fetal outcomes in hypertensive pregnancies. (Johnsonet

al.,2003).During pregnancy, elevated plasma uric acid levels are associated with an

increased risk of adverse fetal and maternal outcomes in women with preeclampsia or

benign gestational hypertension(T. Lee-Ann Hawkinset al.,2012).

15

1.2 Justification: There is an extremely high maternal mortality in Sudan with pre-eclampsia/eclampsia

accounting for 4.2% of the obstetric complications and 18.1% of maternal deaths

(Leibermanet al., 1991; Ali and Adam, 2011; Ali et al., 2012).

Severe preeclampsia can result in pulmonary edema cerebral hemorrhage, hepatic failure,

renal failure, seizures (eclampsia), disseminated intravascular coagulation (primarily with

abruption), and maternal death. Fetal/neonatal consequences include preterm

birth,stillbirth, growth restriction, and admission to a neonatal intensive care unit.

The ability to predict preeclampsia is currently of limited benefit because neither the

development of the disorder nor its progression from mild to severe disease can be

prevented in most patients, and there is no cure except delivery. Nevertheless, the accurate

identification of women at risk, early diagnosis, and prompt and appropriate management

(eg, antenatal corticosteroids for fetal lung maturation, treatment of severe hypertension,

early delivery) may improve maternal outcome, and possibly prenatal outcome, as well. A

good test for predicting women who will develop preeclampsia should be simple, rapid,

noninvasive, inexpensive, easy to perform, and should not expose the patient to discomfort

or risk. Ideally, it should provide an opportunity for intervention to prevent development

of the disease, or at least result in better maternal and/or fetal outcomes.

Currently, there are no clinically available tests that perform well in distinguishing women

who will develop preeclampsia from those who will not. In addition to developing novel

approaches to prediction of preeclampsia, future studies should distinguish the ability of

screening tests to predict mild versus severe preeclampsia and early versus term

preeclampsia.

16

1.3 Objectives:

1.3.1 General Objective:

To determine the levelsof uric acid, phosphorus and calcium in preeclampsia pregnant

women attendingto Wad Medani Maternity Teaching Hospital.

1.3.2 Specific Objectives:

1. To measure the levels of serum uric acid,calcium and phosphorous in

preeclampsia pregnant women.

2. To measure the concentration of serum uric acid, calcium and phosphorus in

healthy pregnant women.

3. To compare between the above investigated levels ofpreeclampsia pregnant

women and normal healthy pregnant women.

17

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATRE REVIEW 2.1 Hypertension:

Correct measurement and interpretation of the blood pressure (BP) is essential in the

diagnosis and management of hypertension. Proper BP machine calibration, training of

personnel, positioning of patient, and selection of cuff size are all essential.The following

recommendations have been made to achieve maximum accuracy in this process

(Pickering et al.,2005,Beeverset al.,2001). However, studies suggest that most physicians

do not follow one or more of these recommendations, leading to potential errors in

diagnosis and management(Brienet al.,2003).There are four major hypertension related to

pregnancy (Phyllis et al.,2011), this includes: Preeclampsia/Eclampsia, Chronic

hypertension, Preeclampsia superimposed upon chronic hypertension, and Gestational

hypertension.

2.1.1 Preeclampsia

Preeclampsia refers to a syndrome characterized by the new onset of hypertension and

proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation in a previously normotensive(Phyllis et

al.,2011).Women with preeclampsia gradually develop high blood pressure (hypertension)

and excess protein in the urine (proteinuria).Signs of preeclampsia can appear anytime

during the last half of pregnancy (after 20 weeks of pregnancy) or in the first few days

postpartum, and typically resolve within a few days after delivery (Vanessa et al.,2010).

Preeclampsia is sometimes called by other names, including toxemia, pregnancy-induced

hypertension, and preeclamptic toxemia. It is mild in most cases. One severe form of

preeclampsia is called HELLP syndrome (H = hemolysis, EL = elevated liver enzymes,

LP = low platelets). A woman is said to have eclampsia if she has one or more seizures

and has no other conditions that could have caused the seizure(Vanessa et al.,2010). The

diagnostic criteria was; Systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or Diastolic blood pressure

≥90 mmHg and Proteinuria of 0.3 grams or greater in a 24-hour urine specimen. It is

classified as mild or severe. The classification of severe preeclampsia serves to emphasize

the more ominous features of the syndrome; patients with severe disease have one or more

of the findings below (Cunningham and Lindheimer, 1992; National Institute of Health,

2000).

18

2.1.1.1 Eclampsia:

Eclampsiarefers to the occurrence of one or more generalized convulsions and/or coma in

the setting of preeclampsia and in the absence of other neurologic conditions

(ACOG,1996). The clinical manifestations can appear anytime from the second trimester

to the puerperium. In the past, eclampsia was thought to be the end result of

preeclampsiahowever, it is now clear that seizures should be considered merely one of

several clinical manifestations of severe preeclampsia rather than a separate disease.

Despite advances in detection and management, preeclampsia/eclampsia remains a

common cause of maternal death (CDC, 2014).The degree of maternal hypertension, the

amount of proteinuria, and the presence/absence of laboratory abnormalities in

preeclampsia are highly variable (ranging from mild to severe), as is the gestational age at

onset (Sibai,2008). The manifestations of preeclampsia can develop at <34 weeks (early

onset), at ≥34 weeks (late onset), during labor, or postpartum. Early and late onset

preeclampsia may have different path-physiologies as early onset disease is usually

associated with fetal growth restriction and evidence of ischemic lesions on placental

examination, whereas late onset disease is not (Moldenhauer et.al, 2003). Maternal

hemodynamics also may be different (Valensise et al.,2008).

2.1.1.2Criteria for preeclampsia:

The criteria for preeclampsia where a new onset ofproteinuric hypertension and includes

at least one of the following:

Symptoms of central nervous system dysfunction:

Blurred vision, scotomata, altered mental status, severe headache (i.e., incapacitating, "the

worst headache I've ever had") or headache that persists and progresses despite analgesic

therapy.

Symptoms of liver capsule distention:

Right upper quadrant or epigastria pain

Nausea, vomiting

Hepatocellular injury:

Serum transaminase concentration at least twice normal

Severe blood pressure elevation:

19

Thesystolic blood pressure ≥160 mm Hg or diastolic ≥110 mm Hg on two occasions at

least six hours apart

Thrombocytopenia:

Plateletscount less than 100,000 platelets per cubic millimeter.

Proteinuria:

5 or more grams in 24 hours

Oliguria <500 ml in 24 hours

Severe fetal growth restriction

Pulmonary edema or cyanosis

Cerebrovascular accident

2.1.4 Preeclampsia superimposed upon chronic hypertension:

Superimposed preeclampsia is diagnosed when a woman with preexisting hypertension

develops new onset proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation. Women with both preexisting

hypertension and proteinuria are considered preeclamptic if there is an exacerbation of

blood pressure to the severe range (systolic ≥160 mmHg or diastolic ≥110 mmHg) in the

last half of pregnancy, especially if accompanied by symptoms or increased liver

enzymes or thrombocytopenia. Signs/symptoms suggestive of preeclampsia superimposed

upon preexisting hypertension are listed below.

Signs suggestive of preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension

New onset proteinuria.

Hypertension and proteinuria beginning prior to 20 weeks of gestation.

A sudden increase in blood pressure.

Thrombocytopenia.

Elevated aminotransferases.

2.1.6 Risk factors:

Table of factors associated with an increased risk of developing preeclampsia (Phylliset

al.,2011)

Nulliparity

Preeclampsia in a previous pregnancy

Age >40 years or <18 years

20

Family history of preeclampsia

Chronic hypertension

Chronic renal disease

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome or inherited thrombophilia

Vascular or connective tissue disease

Diabetes mellitus (presentational and gestational)

Multifetal gestation

High body mass index

Male partner whose mother or previous partner had preeclampsia

Hydropsfetalis

Unexplained fetal growth restriction

Woman herself was small for gestational age

Fetal growth restriction, abruptioplacenta, or fetal demise in a previous pregnancy

Prolonged interpregnancy interval.

The magnitude of risk depends upon the specific condition and its severity (Barton and

Sibai, 2008). Past obstetrical history of preeclampsia is a strong risk factor for

preeclampsia in a future pregnancy. A systematic review of controlled studies reported

that the relative risk of preeclampsia in women with a history of the disorder compared to

women with no such history was 7.19 (95% CI 5.85-8.83) (Duckitt and Harrington, 2005).

Women with early, severe preeclampsia (approximately 2 percent of cases in nulliparas)

are at greatest risk of recurrence, rates of 25 to 65 percent have been reported (Sibai and

Gonzalez, 1986; Gaugleret al.,2008).In women who had mild preeclampsia during the first

pregnancy, the incidence of preeclampsia in a second pregnancy is 5 to 7 percent,

compared to less than 1 percent in women who had a normotensive first pregnancy i.e.

does not apply to abortions (Campbell et al.,1985).First pregnancy (Nulliparity) increases

the risk for developing preeclampsia (2.91, 95% CI 1.28-6.61) (Duckitt and Harrington,

2005). It is unclear why the primigravid state is such an important predisposing factor.A

family history of preeclampsia in a first degree relative is associated with an increase in

risk (RR 2.90, 95% CI 1.70-4.93) (Duckitt and Harrington, 2005), suggesting a heritable

mechanism in some cases (Dawsonet al.,2002). The father of the baby may contribute to

21

the increased risk, as the paternal contribution to fetal genes may have a role in defective

placental and subsequent preeclampsia. Presentational diabetes also increases risk of

preeclampsia (RR 3.56, 95% CI 2.54-4.99) (Duckitt and Harrington, 2005), an effect that

is probably related to a variety of factors such as underlying renal or vascular disease, high

plasma insulin levels/insulin resistance, and abnormal lipid metabolism (Dekker and Sibai,

1998).Multiple gestation increases the risk of preeclampsia; for twin pregnancies the

relative risk is 2.93, 95% 2.04-4.21 (Duckitt and Harrington, 2005). The risk rises with the

number of fetuses. Obesity has been consistently reported to increase the risk of

preeclampsia. Preexisting hypertension, renal disease, and collagen vascular disease are

well-described risk factors. The Antiphospholipid syndrome has been associated with

multiple pregnancy complications including preeclampsia, fetal loss, and maternal

thrombosis (Stella et al.,2006). There is conflicting evidence regarding an association

between hereditary thrombophilia and preeclampsia, but the weight of evidence suggests

no association. Advanced maternal age is an independent risk factor for preeclampsia

(maternal age ≥40 1.96, 95% CI 1.34-2.87 for multifarious women) (Duckitt and

Harrington, 2005). Older women tend to have additional risk factors, such as diabetes

mellitus and chronic hypertension. Whether adolescents are at higher risk of preeclampsia

is more controversial (Saftlas et.al, 1990); a systematic review did not find an association

(Duckitt and Harrington, 2005).A prolonged interval between pregnancies appears to

increase the risk of developing preeclampsia. Limited recent exposure to paternal antigens

appears to be a risk factor based on the increased risk of preeclampsia in nulliparous

women and women who change partners between pregnancies, have long interpregnancy

intervals, use barrier contraception, and conceive via intracytoplasmic sperm injection

(Duckitt and Harrington, 2005; Tubbergenet al.,1999; Wang et al.,2002).The role of other

risk factors is unclear. A systematic review of controlled studies found a consistent, small

but statistically significant, association between urinary tract infection during pregnancy

and development of preeclampsia (pooled odds ratio 1.57; 95% CI 1.45-1.70) (Condeet

al.,2008). This finding may have been related to the increased prevalence of underlying

renal disease in women with urinary tract infections. The study also found an association

between periodontal disease and preeclampsia (pooled odds ratio 1.76; 95% CI 1.43-2.18),

but no association between preeclampsia and other common infections (Chlamydia,

22

cytomegalovirus, HIV, herpes, malaria, Mycoplasma hominess, bacterial vaginosis,

Helicobacter pylori). These relationships require further investigation before drawing any

conclusions about causality.Of note, women who smoke cigarettes have a lower risk of

preeclampsia than nonsmokers.

Hyperuricemia is a common finding in preeclamptic pregnancies. The elevation of uric

acidin preeclamptic women often precedes hypertension and proteinuria (Cunningham and

Lindheimer, 1992), the clinical manifestations used to diagnose the disorder. There are

several potential origins for uric acidin preeclampsia; abnormal renal function, increased

tissue breakdown, acidosis andincreased activity of the enzyme xanthine

oxidase/dehydrogenase (Helewaet al.,1997).However, despitehyperuricemia antedating

other clinical findings of preeclampsia, it has historically beenascribed to impaired renal

function. Outside of pregnancy, hyperuricemia is considered arisk factor for hypertension,

cardiovascular and renal disease (Helewa et al.,1997).This evidence, as well asthe

observation that severity of preeclampsia increases with increasing uric acid,

questionswhether uric acid may play a role in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. While

thisconcept is largely unstudied, we expand upon ideas forwarded by Kang (National

Institute of Health, 2000) to share in thehypothesis that an elevated concentration of uric

acid in preeclamptic women is not simply amarker of disease severity but rather

contributes directly to the pathogenesis of the disorder.We hypothesize that uric acid acts

adversely upon both the placenta and maternalvasculature.

2.1.8 Proteinuria:

In non-pregnant individuals, abnormal total protein excretion is typically defined as

greater than 150 mg daily. In normal pregnancy, urinary protein excretion increases

substantially, due to a combination of increased glomerular filtration rate and increased

permeability of the glomerular basement membrane (Cunningham et al.,1992). Hence,

total protein excretion is considered abnormal in pregnant women when it exceeds 300

mg/24 hours (Sibai et al.,2008).Proteinuria is one of the cardinal features of preeclampsia

which is a common and potentially severe complication of pregnancy. However, two

important points should be noted. First, the severity of proteinuria is not indicative of the

severity of preeclampsia and should not be used to guide management (Sibai,2008).

Second, although part of the formal diagnostic criteria of preeclampsia, proteinuria may be

23

absent. Studies have shown that 10 percent of women with clinical and/or histological

manifestations of preeclampsia have no proteinuria and 20 percent of women with do not

have significant proteinuria prior to their seizure (Moldenhauer et al.,2003).Although less

prevalent, primary renal disease and renal disease secondary to systemic disorders, such as

diabetes or essential hypertension, are also usually characterized by proteinuria and may

first present in pregnancy. To further complicate this picture, 20 to 25 percent of women

with chronic hypertension and diabetes develop superimposed preeclampsia (Barton et

al.,2001).It is important for clinicians caring for pregnant women to understand how to

identify proteinuria, and how to determine whether preeclampsia or renal disease (or both)

is the cause. The evaluation of proteinuria in nonpregnant individuals and measurement of

protein excretion are discussed in detail separately. In addition to hypertension, proteinuria

(i.e., ≥0.3 g protein in a 24-hour urine specimen or persistent 1+ (30 mg/dl) on dipstick)

must be present to make a diagnosis of preeclampsia. Urinary protein excretion increases

gradually, may be a late finding, and is of variable magnitude in preeclampsia. Proteinuria

is due, in part, to impaired integrity of the glomerular barrier and altered tubular handling

of filtered proteins (hypo filtration) leading to increased protein excretion (Sibai et.al,

m1986). Both size and charge selectivity of the glomerular barrier is affected (CDC,

2014).

2.2.2 Screening for proteinuria:

Routine antepartum care for detection of preeclampsia, includes dipstick protein testing of

a random voided urine sample at each prenatal visit.

Standard urine dipstick testing is commonly performed on a fresh, clean voided,

midstream urine specimen obtained before pelvic examination to minimize the chance of

contamination from vaginal secretions. The urinary dipstick for protein is a semi-

quantitative colorimetric test that primarily detects albumin. Results range from negative

to 4+, corresponding to the following estimates of protein excretion:

Negative

Trace - between 15 and 30 mg/dL

1+ - between 30 and 100 mg/dL

2+ - between 100 and 300 mg/dL

3+ - between 300 and 1000 mg/dL

24

4+ - >1000 mg/dL

A positive reaction (+1) for protein develops at the threshold concentration of 30 mg/dL,

which roughly corresponds to a 24-hour urinary protein excretion of 300 mg/day,

depending on urine volume.

False positive tests may occur in the presence of gross (macroscopic) blood in the urine,

semen, very alkaline urine (pH >7), quaternary ammonium compounds, detergents and

disinfectants, drugs, radio-contrast agents, and high specific gravity (>1.030). Positive

tests for protein due to blood in the urine seldom exceed 1+ by dipstick. ( NKF& NIDDK

2003)

False negatives may occur with low specific gravity (<1.010), high salt concentration,

highly acidic urine, or with nonalbumin proteinuria. Despite these limitations, routine

urinary dipstick testing remains the mainstay of proteinuria screening in obstetric practice.

(NKF & NDDK 2003)

2.2 Bio chemical tests:

The diagnosis of preeclampsia is largely based upon the characteristic clinical features

described above developing after 20 weeks of gestation in a woman who was previously

normotensive (Sibai, 2003). Preeclampsia is usually diagnosed ante-partum or intra-

partum, but may first present clinically in the postpartum period (Matthyset al., 2004).

The elevated blood pressure should be documented on two occasions at least six

hours, but no more than seven days, apart .

Screening urine for proteinuria is an integral part of ante-partum care strategy to

detect preeclampsia.

Testing is commonly performed by dipping a paper test strip into a fresh clean voided

midstream urine specimen. The specimen should be obtained before pelvic examination to

minimize the chance of contamination from vaginal secretions. Women with proteinuria

on dipstick should undergo quantitative measurement of protein excretion as urinary

protein dipstick values do not correlate well with 24-hour urinary protein excretion values.

Protein/creatinine ratios have not been found to accurately reflect 24-hour urine excretion

in pregnant women.

25

2.2.3 Quantifying protein excretion:

Urinary protein can be measured as either albumin or total protein. Non-pregnant women

normally excrete less than 30 mg of albumin [Waugh JJ, et al 2004] and less than 150 mg

of total protein daily. In normal pregnancy, total protein excretion increases to 150 to 250

mg daily, and is even higher in twin pregnancies (Vibertiet al.,1992).

The two approaches to a definitive quantitative measurement of protein excretion are:

24-hour collection — The traditional method requires a 24-hour urine collection to

directly determine the daily total protein or albumin excretion. The 24-hour collection is

begun at the usual time the patient awakens. At that time, the first void is discarded and

the exact time noted. Subsequently, all urine voids are collected with the last void timed to

finish the collection at exactly the same time the next morning. The time of the final urine

specimen should vary by no more than 5 or 10 minutes from the time of starting the

collection the previous morning. An inexpensive basin urinal that fits into the toilet bowl

facilitates collection. The bottle(s) may be kept at normal room temperature for a day or

two, but should be kept cool or refrigerated for longer periods of time. No preservatives

are needed.(National kidney foundation (NKF) and the National institute of diabetes and

digestive and kidney diseases (NIDDK, 2003)

Although generally considered the "gold standard" for diagnosis of proteinuria in both

preeclampsia and renal disease, the 24-hour urine protein excretion in pregnant women is

frequently inaccurate due to undercollection or overcollection (Smith NA, et al, 2010).

Thus, when interpreting the results of a 24-hour urine collection, it is critical to assess the

adequacy of collection by quantifying the 24-hour urine creatinine excretion, which is

based on muscle mass. The 24-hour urine creatinine excretion should be between 15 and

20 mg/kg body weight, calculated using pre-pregnancy weight. Values substantially above

or below this estimate suggest over- and undercollection, respectively, and should call into

question the accuracy of the 24-hour urine protein result. (Ramos et al.,1999)

Urine protein to creatinine ratio — The spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (PC

ratio) has become the preferred method for the quantification of proteinuria in the non-

pregnant population due to high accuracy, reproducibility, and convenience when

compared to timed urine collection (Côtéet al.,2008).

26

The majority of studies evaluating the urine PC ratio in pregnant women were performed

in women with suspected preeclampsia. In these studies, the PC ratio was highly

correlated with the 24-hour urine protein measurement (Eknoyanet al.,2003), as it is in

non-pregnant adults. Routine bladder catheterization for measurement of urine PC ratio is

not necessary; mid-stream clean-catch samples are accurate in pregnant women (Neithardt

ABet al., 2002).

27

CHAPTER THREE

MATERIAL AND METHODS 3.0 Type of the study:

Hospital-based, cross-sectional study.

3.1 Study area:

This study was conducted in Sudan, Gezira state middle of Sudan, Wad Medani in Wad

Medani Maternity Teaching Hospital from known preeclampticpregnant women and

healthy pregnant women whom were on routine checkup.

3.2 Study population and samplescollection:

Fifty preeclamptic pregnant women participated as study group and 50 healthy volunteer

pregnant women participated as a control group. 5mL of venous blood was collected from

each participant in plain container. Serum was separated immediately and stored in

refrigerator at 4°C for two to three days and then analyzed by BioSystems S.A.25

chemistry analyzer.

3.2.1 Inclusion Criteria:

Patients previously identified as preeclamptic pregnant women.

3.2.2Exclusion criteria:

Pregnant women with previous history of chronic kidney disease, liver disease, diabetic

pregnant women and thyroid disorder.

3.3Methods:

A hospital-based, cross-sectional study wasconducted on preeclampsia pregnant women

and health pregnant women whom clinically diagnosed definitely by obstetrician then

undergo for questionnaire for fill to asses basic demography, history of hypertension, and

biochemical test for serum uric acid, calcium and phosphorous level.The test panel

comprises 100 of whom 50 preeclamptic and another 50 normal pregnant women, their

sample were collected and measured using different clinical BioSystems S.A. 25

chemistry analyzers. The study was based on a design to developed similar sample testing

principle.

3.4Uric acid, calcium and phosphorus investigation:

28

Spectrophotometric quantitativedetermination of serum uric acid, calcium and

phosphorous in study subjects using BiosystemS.A.25 chemistry analyzer with

BioSystems reagent.

Serum uric acid was measured by enzymatic color test using Uricase and Peroxidase

enzyme. Intensity of the color is proportional to concentration of uric acid in specific

sample. And Calcium in the sample reacts with arsenazo III forming a colored complex.

likewise inorganic phosphorus in the sample reacts with molybdate in acid medium

forming a phosphomolybdate complex that measured by spectrophotometry

3.5 Ethical consideration:

The proposal was got ethical clearance from the Ministry of Healthresearch ethical

committee. Informed signed consent was collected from all volunteers who participated in

the study, after the purpose, nature and risks of participating in the study were fully

explained to them verbally and in writing. Anonymity was maintained by using a form,

which bear no name and was linked with the sample by stud number. The results of the

participants waskept confidential.

3.6Data analysis:

The results obtained were enter into Microsoft Excel 2007 and were analyzed using

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 18.

29

CHAPTER FOUR

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Results:

50% pregnant women with preeclampsia their each various from 18-42 years old.

18% on second trimester, 82% at third trimester.

4% of them have recurrent preeclampsia.

94% attacked by preeclampsia for the first time.

2% had a family history of preeclampsia.

14%of them on first pregnancy and 86% multiparous pregnancy.

18% from total preeclamptic pregnant women was obese and 82% with normal BMI.

\

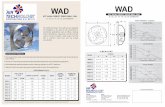

Figure (4.1): The proteinuria in preeclampticpregnant women

16.0%

84.0%

++

+++

30

Table (4.1):Comparison of meansof uric acid among cases and controls.

Cases N Mean Std. Deviation P value

Uric acid Preeclampsia pregnant

women 50 5.8 1.75

0.000 Healthy pregnant

women 50 4.1 1.18

31

Table (4.2):Comparison of means of calcium among cases and controls.

Cases N Mean Std. Deviation P value

Ca Preeclampsia pregnant

women 50 8.8 0.63

0.050 Healthy pregnant

women 50 9.0 0.55

32

Table (4.3):Comparison of means of phosphorus among cases and controls.

Cases N Mean Std. Deviation P value

Phosphorus Preeclampsia pregnant

women 50 3.3 0.69

0.061 Healthy pregnant

women 50 3.6 0.67

33

4.2 Discussion:

Pre-eclampsia, is one of the most common complications of pregnancy, it is a leading

cause of maternal and prenatal mortality worldwide.

This hospital-based, cross-sectional study conducted in Wad-Medani maternity hospital.

The majority of the cases (82%) were in the third trimester and 18% in the last period of

second trimester.

Early and late onset preeclampsia may have different path-physiologies as early onset

disease is usually associated with fetal growth restriction and evidence of ischemic lesions

on placental examination, whereas late onset disease is not (Moldenhauer et.al, 2003). In

this study, 16% had ++ of proteinuria and 84% had +++in preeclamptic pregnant

women.Hence, total protein excretion is considered abnormal in pregnant women when it

exceeds 300 mg/24 hours (Sibai et al., 2008). Proteinuria is one of the cardinal features of

preeclampsia which is a common and potentially severe complication of pregnancy.

However, two important points should be noted. First, the severity of proteinuria is not

indicative of the severity of preeclampsia and should not be used to guide management

(Sibai et al., 2008).

In this study comparison means of uric acid, calcium and phosphorus between cases and

controls showed highly significant difference in uric acid level (p. value 0.000). The

elevation of uric acid in preeclamptic women often precedes hypertension and proteinuria

(Cunningham and Lindheimer, 1992), the clinical manifestations used to diagnose the

disorder. There are several potential origins for uric acid in preeclampsia; abnormal renal

function, increased tissue breakdown, acidosis and increased activity of the enzyme

xanthine oxidase/dehydrogenase (Helewaet al., 1997). However, despite hyperuricemia

antedating other clinical findings of preeclampsia, it has historically been ascribed to

impaired renal function. Outside of pregnancy, hyperuricemia is considered a risk factor

for hypertension, cardiovascular and renal disease (Helewa et al., 1997). This evidence, as

well as the observation that severity of preeclampsia increases with increasing uric acid,

questions whether uric acid may play a role in the pathophysiology of

preeclampsia.Hyperuricemia is a common finding in preeclamptic pregnancies.

In the current study, the means of serum calcium and phosphorus in preeclamptic pregnant

women is some little lower than the healthy pregnant women p. value (0.05),

34

(0.06)respectively. The total serum calcium level specifically free ionze fraction is bound

to the albumin, so increased albuminuria decreased this fraction of calcium. Increase the

osteoblastic activity of fetus lead to increase consumption of calcium and phosphorus.

Study done by AbdElkarimet.al, 2014 in fifty preeclamptic pregnant women in

Omdurman maternity hospital. He concluded that serum phosphorus was significantly

decreased in preeclamptic pregnant women.

Study done by Areej, 2015 in fifteen preeclamptic pregnant women in Departement of

Obstetrics and Gynecology in Baghdad Teachin Hospital. She conclude that the serum

calcium is significantly decreased in preeclamptic pregnant women.

35

CHAPTER FIVE

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

5.1 Conclusion:

1. Preeclamptic pregnant women had significant higher uric acid levels than

normal pregnant women.

2. Preeclamptic pregnant women had insignificant lower levels of calcium and

phosphorus.

5.2 Recommendations:

o The pregnant women must be followed routinely for uric acid level, proteinuria

and hypertension.

o More studies on large sample size are recommended to support the findings of this

study.

36

Reference:

AbdElkarimA.Abdrabo, Fadwa Y. Al Madani and Gad Allah Modawe (2014).Serum

Lead and Phosphorus Levels in Sudanese Pregnant Women with Preeclampsia.Br J

Med Health Res. 2(4): 21-25.

ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics (2002). ACOG practice bulletin.

Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia.ObstetGynecol99:159.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (1996).Hypertension in

Pregnancy.ACOG.Technical Bulletin #219.American College of obstetricians and

Gynecologists, Washington, DC.

Areej A. Zabbon (2015). Blood lead and calcium level in pregnant women suffering from

severe preeclampsia in Baghdad, Iraq.Journal of Genetic and Environmental

Resources Conservation 3(1): 30-34.

Barton JR and Sibai BM (2008).Prediction and prevention of recurrent

preeclampsia.ObstetGynecol112:359.

Barton JR, O'brien JM, Bergauer NK et al., (2001). Mild gestational hypertension remote

from term: progression and outcome. Am J ObstetGynecol; 184:979.

Barton JR, O'brien JM, Bergauer NK, et al (2001). Mild gestational hypertension remote

from term: progression and outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

Campbell DM, MacGillivray I and Carr-Hill R (1985).Pre-eclampsia in second

pregnancy.Br J ObstetGynaecol92:131.

Carty DM, Delles C and Dominiczak AF (2010).Preeclampsia and future maternal health.J

Hypertension.

Conde-Agudelo A, Villar J and Lindheimer M (2008). Maternal infection and risk of

preeclampsia: systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J ObstetGynecol198:7.

Côté AM, Firoz T and Mattman A et al., (2008). The 24-hour urine collection: gold

standard or historical practice? Am J Obstet Gynecol.

Cunningham FG and Lindheimer MD (1992).Hypertension in pregnancy.N Engl J Med.

Cunningham FG and Lindheimer MD(1992).Hypertension in pregnancy.N Engle J Med 1;

326:927.

Dawson LM, Parfrey PS, Hefferton D et al., (2002). Familial risk of preeclampsia in

Newfoundland: a population-based study. J Am SocNephrol 13:1901.

37

Dekker GA and Sibai BM (1998). Etiology and pathogenesis of preeclampsia: current

concepts. Am J ObstetGynecol179:1359.

Duckitt K and Harrington D (2005). Risk factors for pre-eclampsia at antenatal booking:

systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ330:565.

Eknoyan G, Hostetter T and Bakris GL et al., (2003).Proteinuria and other markers of

chronic kidney disease: a position statement of the national kidney foundation (NKF)

and the national institute of diabetes and digestive and kidney diseases (NIDDK). Am

J Kidney Dis.

Gaugler-Senden IP, Berends AL, de Groot C and Steegers EA (2008). Severe, very early

onset preeclampsia: subsequent pregnancies and future parental cardiovascular health.

Eur J ObstetGynecolReprodBiol140:171.

Helewa ME, Burrows RF and Smith J et al., (1997). Report of the Canadian Hypertension

Society Consensus Conference: 1. Definitions, evaluation and classification of

hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. CMAJ 157:715.

Klonoff-Cohen HS, Savitz DA, Cefalo RC and McCann MF(1989).An epidemiologic

study of contraception and preeclampsia.JAMA262:3143.

Lain KY and Roberts JM (2002).Contemporary concepts of the pathogenesis and

management of preeclampsia.JAMA287:3183.

Matthys LA, Coppage KH andLambers DS et al., (2004). Delayed postpartum

preeclampsia: an experience of 151 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

Moldenhauer JS, Stanek J and Warshak C et al., (2003). The frequency and severity of

placental findings in women with preeclampsia are gestational age dependent. Am J

ObstetGynecol189:1173.

Moldenhauer JS, Stanek J and Warshak C, et al., (2003). The frequency and severity of

placental findings in women with preeclampsia are gestational age dependent.Am J

Obstet Gynecol.

Neithardt AB, Dooley SL and Borensztajn J (2002).Prediction of 24-hour protein excretion

in pregnancy with a single voided urine protein-to-creatinine ratio.Am J Obstet

Gynecol.

38

Nilsson E, SalonenRos H, Cnattingius S and Lichtenstein P (2004). The importance of

genetic and environmental effects for pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension: a

family study. BJOG111:200.

Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on

High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy (2000).Am J Obstet Gynecol.

Robert M, Sepandj F, Liston RM and Dooley KC (1997). Random protein-creatinine ratio

for the quantitation of proteinuria in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol.

Roberts JM, Pearsons G, Cutler J, Lindheimer M (2003). Summary of the NHLBI

Working Group on research on hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension.

Roberts M, Lindheimer MD and Davison JM (1996).Altered glomerular permselectivity to

neutral dextrans and heteroporous membrane modeling in human pregnancy.Am J

Physiol.

Robilland PY, Hulsey TC, Dekker GA andChaouat G (2003). Preeclampsia and human

reproduction: an essay of long-term reflection. J ReprodImmunol.

Ros HS, Cnattingius S and Lipworth L (1998).Comparison of risk factors for preeclampsia

and gestational hypertension in a population-based cohort study.Am J Epidemiol147.

Saftlas AF, Olson DR and Franks AL et al., (1990).Epidemiology of preeclampsia and

eclampsia in the United States, 1979-1986.Am J ObstetGynecol 163:460.

Saudan P, Brown MA, Buddle ML and Jones M (1998). Does gestational hypertension

become pre-eclampsia? Br J ObstetGynaecol105:1177.

Sibai B, Dekker G and Kupferminc M (2005). Preeclampsia. Lancet.

Sibai BM (2003).Diagnosis and management of gestational hypertension and

preeclampsia.Obstet Gynecol.

Sibai BM (2004). Magnesium sulfate prophylaxis in preeclampsia: Lessons learned from

recent trials. Am J ObstetGynecol190:1520.

Sibai BM (2008).Maternal and uteroplacental hemodynamics for the classification and

prediction of preeclampsia.Hypertension 52:805.

Sibai BM (2008).Maternal and uteroplacental hemodynamics for the classification and

prediction of preeclampsia.Hypertension.

39

Sibai BM, el-Nazer A and Gonzalez-Ruiz A (1986). Severe preeclampsia-eclampsia in

young primigravid women: subsequent pregnancy outcome and remote prognosis. Am

J ObstetGynecol155:1011.

Sibai BM, Gordon T and Thom E et al., (1995). Risk factors for preeclampsia in healthy

nulliparous women: a prospective multicenter study. The National Institute of Child

Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units.Am J

ObstetGynecol172:642.

Sibai BM, Mercer B and Sarinoglu C (1991). Severe preeclampsia in the second trimester:

recurrence risk and long-term prognosis. Am J ObstetGynecol165:1408.

Skjaerven R, Wilcox AJ and Lie RT (2002).The interval between pregnancies and the risk

of preeclampsia.N Engl J Med346:33.

Smith NA, Lyons JG and McElrath TF (2010).Protein:creatinine ratio in uncomplicated

twin pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

Stella CL, How HY and Sibai BM (2006). Thrombophilia and adverse maternal-perinatal

outcome: controversies in screening and management. Am J Perinatol23:499.

Tubbergen P, LachmeijerAM, Althuisius SM et al., (1999). Change in paternity: a risk

factor for preeclampsia in multiparous women? J ReprodImmunol45:81.

Uzan J, Carbonnel M, Piconne O, Asmar R and Ayoubi JM (2011).Pre-eclampsia:

Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Vasc Health Risk Manag.

Valensise H, Vasapollo B, Gagliardi G and Novelli GP (2008). Early and late preeclampsia:

two different maternal hemodynamic states in the latent phase of the disease.

Hypertension52:873.

Van Rijn BB, Hoeks LB and Bots ML et al., (2006).Outcomes of subsequent pregnancy

after first pregnancy with early-onset preeclampsia.Am J ObstetGynecol195:723.

Viberti GC, Jarrett RJ and Keen H (1982).Microalbuminuria as prediction of nephropathy

in diabetics.Lancet.

Wang JX, KnottnerusAM, Schuit G et al., (2002). Surgically obtained sperm, and risk of

gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia. Lancet359:673.

Waugh JJ, Clark TJ and Divakaran TG et al., (2004).Accuracy of urinalysis dipstick

techniques in predicting significant proteinuria in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol.