The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery › 638b › 13086f8828c... · Fig. 3. (A) Clinical photograph...

Transcript of The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery › 638b › 13086f8828c... · Fig. 3. (A) Clinical photograph...

lable at ScienceDirect

The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery 54 (2015) 821–825

Contents lists avai

The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery

journal homepage: www.j fas .org

Use of Ilizarov External Fixation Without Soft Tissue Releaseto Correct Severe, Rigid Equinus Deformity

Bi O Jeong, MD, PhD, Tae Yong Kim, MD, Wook Jae Song, MDDepartment of Orthopaedic Surgery, Kyung Hee University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

a r t i c l e i n f o

Level of Clinical Evidence: 4

Keywords:ankle deformitygaitgradual correctionIlizarov external fixatortalustibia

Financial Disclosure: None reported.Conflict of Interest: None reported.Address correspondence to: Bi O Jeong, MD, Ph

Surgery, Kyung Hee University College of Medicine,Seoul 130-702, Korea.

E-mail address: [email protected] (B.O. Jeong).

1067-2516/$ - see front matter � 2015 by the Americhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2014.12.039

a b s t r a c t

The purpose of the present retrospective study was to report the correction of severe, rigid equinus de-formities using an Ilizarov external fixator alone, without adjunctive open procedures. Ten feet in 10 patientswith rigid equinus deformities were enrolled and underwent gradual correction using an Ilizarov externalfixator alone, without additional open procedures. The range of ankle joint motion was measured preopera-tively and at the last follow-up visit. The radiographic outcome was assessed using the lateral tibiotalar angleon ankle radiographs taken preoperatively, immediately after removal of the Ilizarov fixator, and at the lastfollow-up visit. The mean duration of external fixator treatment was 40.1 � 13.5 days. The preoperative meanankle range of motion was �55.5� � 22.2� of dorsiflexion and 63.0� � 20.8� of plantarflexion. At the lastfollow-up visit, the mean dorsiflexion had increased to �2.5� � 6.8� and the mean plantarflexion haddecreased to 30.5� � 12.6�. The mean lateral tibiotalar angle was 152.9� � 19.7� preoperatively, 103.9� � 9.4�

immediately after removal of the Ilizarov external fixator, and 113.9� � 11.6� at the last follow-up visit.Immediately after fixator removal, all the patients had clinical correction of their deformity to a plantigradefoot using the Ilizarov external fixator alone, with a mean correction of 49.0� � 17.4�. Some recurrence wasnoted at the last follow-up examination, with a final mean correction of 39.0� � 18.0�. The present study hasdemonstrated successful correction of severe, rigid equinus deformity with the use of an Ilizarov externalfixator without the need for adjunctive soft tissue procedures. This method can be effective for patients with ahigh risk of complications after open procedures owing to their poor soft tissue envelope.

� 2015 by the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. All rights reserved.

Equinus deformity is associated with congenital disorders, trauma,burns, neuromuscular disease, and limb lengthening (1–3). A rigidequinus deformity will result in a tip-toe gait, making ambulationdifficult. Conservative treatment, such as stretching exercises, dy-namic splinting, and serial casting, can be attempted for mild equinusdeformities (4). If conservative treatment does not result in adequateheel weightbearing or a compensated toe gait, surgical options shouldbe considered (5–7). The surgical options for correction of equinusdeformities include soft tissue release, tendon transfer, osteotomy orwedge resection, and hindfoot fusion (4,8–18). These procedures aretechnically challenging and the risk of complications is high, inparticular, in the setting of associated infection or poor soft tissueenvelope (8,12).

In such cases, an Ilizarov external fixator with the concept ofdistraction histogenesis has been used as a less-invasive attempt to

D, Department of Orthopaedic1 Hoegi-dong, Dongdaemun-gu,

an College of Foot and Ankle Surgeon

correct equinus deformities (19–23). Most of the existing studies havereported the use of an Ilizarov external fixator combined with openprocedures such as soft tissue release (11,24–27). Experience withcorrection of equinus deformities using an Ilizarov external fixatoralone without adjunctive soft tissue procedures is limited.

Thus, we hypothesized that the ankle range of motion wouldsignificantly improve both clinically and radiographically using anIlizarov external fixator alone in cases of severe rigid equinus defor-mity. Our primary aim was to evaluate the extent of correctionpossible using an Ilizarov external fixator alone, without adjunctivesoft tissue procedures, in patients with a rigid equinus deformity andto investigate the extent to which equinus deformities recur aftercorrection.

Patients and Methods

Our institutional review board approved the present study, and all patients pro-vided informed consent. Ten feet in 10 patients with an equinus deformity wereenrolled from March 2000 to October 2012 and underwent placement of an Ilizarovexternal fixator alone for gradual correction. Of the 10 patients, 8 weremale (80%) and 2were female (20%), and the mean age at correction was 28 (range 15 to 55) years.

All patients were ambulatory preoperatively, with varying severity of limp due tothe tip-toe gait. The etiology of equinus deformities was spastic type cerebral palsy in 2

s. All rights reserved.

B.O. Jeong et al. / The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery 54 (2015) 821–825822

(20%), congenital neuromuscular disease (hereditary spastic paraplegia) in 1 (10%),chronic osteomyelitis after an open tibia fracture in 3 (30%), pyogenic Achilles tendinitisin 1 (10%), peroneal nerve palsy in 1 (10%), limb lengthening in 1 (10%), and tumorexcision on the calf in 1 patient (10%). None of the patients showed improved ankledorsiflexion, even after flexion of the knee joints. No patient had previously undergonesurgical treatment of the equinus deformity. The mean duration of the equinusdeformity was 7.4 (range 1 to 21) years. A mean of 3.5 (range 0 to 11) operations hadbeen performed for the treatment of the causes of the equinus deformities but none forcorrection of the equinus deformity itself. The skin condition was poor in almost allpatients because most of the previous surgeries had been performed on the ankle oraround the foot.

The mean follow-up period from the removal of the Ilizarov external fixator was1 year, 3 months (range 12 months to 2 years, 2 months). The clinical results wereevaluated using the range of ankle joint motion. The heel weightbearing ambulationwas measured preoperatively and at the last follow-up examination. The radiographicoutcomes were measured using the lateral tibiotalar angle (lateral angle between thelong axis of the tibia and the long axis of the talus) on weightbearing lateral ankleradiographs taken preoperatively, immediately after removal of the Ilizarov externalfixator, and at the last follow-up visit. In addition, the Wilcoxon signed rank test wasused to identify whether significant ankle dorsiflexion and plantarflexion improve-ments had occurred postoperatively. A p value of � .05 was considered statisticallysignificant. All statistical analyses were performed by a statistician using the SPSSstatistical software, version 13.0 (SPSS Inc, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Surgical Technique

The procedure was performed with the patient under general or spinal anesthesia.With the patient in the supine position and the leg under tourniquet control, a pillowwas placed under the hip to rotate the ankle internally. Two rings were mounted to thetibia using 2 tensioned wires. The tibial rings were considered as the base fordistraction. The calcaneus was fixed with a wire and a half ring. A wire was passedthrough the midshaft of the first and fifth metatarsals. An additional wire was addedjust proximal to the metatarsal wires. The 2 wires used on the metatarsal bones werefixed to the straight plates connected to the half ring of the calcaneus, and anotherforefoot half ring was connected to the distal part of the straight plate to which themetatarsal bone wires were fixed. The calcaneal half ring was connected to the tibialring using 3 rods: 1 posterior and 2 on each side (medial and lateral). From the anterioraspect, the forefoot half ring was connected to the tibial ring, again using 1 rod placed inthe central hole of the half ring. One plane hinge was placed on the medial and lateralrods to pivot on the talus center. We used uniplane hinges in most patients (Fig. 1).

Gradual correction was started 1 week after application of the Ilizarov externalfixator. Initially, correctionwas performed 4 times daily to the maximal extent that wasnot painful to the patient. When the patients began to feel pain, correction was

Fig. 1. (A and B) Clinical photographs of

advanced at a rate of 3 to 4mm daily, or 1�. If the pain intensified, correctionwas brieflysuspended until the pain had subsided. After receiving training on pin site dressing, thepatients performed the dressing changes themselves on a daily basis. A radiographicexaminationwas performed every 2 weeks to check for anterior translation of the talus.Clinically, correction with the Ilizarov fixator continued until �5� of ankle dorsiflexionhad been achieved. After correction of the deformity, the Ilizarov external fixator wasmaintained for a period equal to that required to achieve correction. When pin siteinfection was observed, the Ilizarov external fixator was removed earlier and replacedwith a short leg cast or a brace for the remaining treatment period. At completion of thefixation period, full weightbearing ambulation was gradually attempted for severalweeks with the brace in place. The patients used an ankle foot orthosis after completionof the correction.

Results

The mean duration required for correction of equinus deformityusing the Ilizarov external fixator was 40.1 (range 28 to 58) days. Themean duration of maintaining the corrected ankle with the Ilizarovexternal fixator or cast after completion of the correction was 37.5(range 28 to 59) days. The preoperative mean ankle range of motiondemonstrated rigid equinus deformity, with �55.5� (range �80�

to �15�) in dorsiflexion and 63� (range 15� to 90�) in plantarflexion.These had significantly changed at the last follow-up visit to �2.5�

(range �20� to 5�) in dorsiflexion (p ¼ .003) and 30.5� (range 0� to40�) in plantarflexion (p ¼ .003; Fig. 2). The overall mean ankle rangeof motion showed statistically significant improvement from 7.5�

(range 0� to 30�) preoperatively to 28� (range 5� to 40�) post-operatively (p ¼ .011). At the last follow-up visit, ankle dorsiflexionwas 5� in 1 patient (10%), 0� in 6 patients (60%), �5� in 2 patients(20%), and �20� in 1 patient (10%). All the patients, except for thepatient with �20� of dorsiflexion, were able to achieve adequatecorrection to allow heel walking during gait (Fig. 3). All patients wereambulatory without assistance at the final follow-up visit.

The mean lateral tibiotalar angle on the weightbearing radio-graphs of the anklewas 152.9� (range 114� to 170�) preoperatively andhad improved to 103.9� (range 89� to 120�) after removal of the Ili-zarov fixator. The mean radiographic correction was 49� (range 14� to72�). Some recurrence was seen at the final follow-up visit, with a

an applied Ilizarov external fixator.

Fig. 2. (A) Clinical photograph of a 23-year-old male with a rigid equinus deformity from congenital neuromuscular disease (hereditary spastic paraplegia). (B) Clinical photograph ofgradual correctionwith an Ilizarov external fixator. (C) Clinical photograph at the last follow-up visit showing that the angle of dorsiflexion had improved from �65�to 0� . Radiographs (D)of the same patient preoperatively, (E) during gradual correction, (F) after correction, and (G) at the last follow-up visit. The mean lateral tibiotalar angle had improved from 170� to 110� .

B.O. Jeong et al. / The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery 54 (2015) 821–825 823

mean lateral tibiotalar angle of 113.9� (range 100� to 135�) and meanradiographic correction of 39� (range 6� to 66�; Table).

No neurovascular complications were observed. Also, no hammertoe deformities were present. One patient (10%) demonstrated ante-rior translation of the ankle joint 3 days after correction, for which

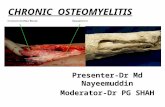

Fig. 3. (A) Clinical photograph of a 41-year-old male with a rigid equinus deformity from chrtreatment of the causes of the equinus deformity. The skin condition of the ankle, foot, ancorrection using an Ilizarov external fixator. (D) Clinical photograph at the last follow-up visitunable to walk on his heels but was ambulatory without brace assistance.

reduction was performed with the patient under local anesthesia.Mild superficial pin site infection was observed in 3 patients (30%),and these were successfully treated with oral antibiotics. No radio-graphic finding of the progression of postoperative arthritis was notedfor any of the patients.

onic osteomyelitis after an open tibial fracture. Six operations had been performed for thed surrounding area was poor. (B) Clinical photograph and (C) radiograph during gradualshowing that the angle of dorsiflexion had improved from �65� to �20� . The patient was

TableClinical data for all patients

Patient No. Age (y) Preoperative AnkleDorsiflexion (�)

Preoperative AnklePlantarflexion (�)

Radiographic Correction (�) CorrectionLoss (�)

Last Follow-Up Visit

Immediately After IlizarovRemoval

At LastFollow-Up Visit

AnkleDorsiflexion (�)

AnklePlantarflexion (�)

1 49 �30 60 33 22 11 0 302 18 �60 60 59 41 18 0 403 55 �65 70 64 49 15 0 404 24 �80 80 72 66 6 0 405 18 �75 75 53 49 4 �5 406 20 �30 45 34 22 12 �5 307 23 �65 70 60 52 8 0 358 15 �15 15 14 6 8 5 09 41 �65 65 48 33 15 �20 3010 19 �70 90 53 50 3 0 20Mean � SD 28.2 � 14.5 �55.5 � 22.2 63.0 � 20.8 49.0 � 17.4 39.0 � 18.0 10.0 � 5.0 �2.5 � 6.8 30.5 � 12.6

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

B.O. Jeong et al. / The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery 54 (2015) 821–825824

Discussion

Equinus deformity interfereswith a normal gait owing to excessiveplantarflexion of the ankle, which limits the ability to achieve aneutral position. Surgical correction is performed to allow a planti-grade foot for improved gait (11). Although open soft tissue releasehas been the standard treatment of equinus deformities, skin andwound complications can easily develop in the course of the correc-tion (8,12). The present study reports the successful use of Ilizarovexternal fixation without an adjunctive soft tissue procedure to cor-rect severe, rigid equinus deformity in a group of 10 patients with softtissue compromise.

One of the main risks of open surgical procedures to correctequinus deformities is soft tissue complications. David et al (8) re-ported infection and wound complication rates as high as 27% withacute surgical correction. Moreover, neurovascular complications canoccur, specifically in the posterior tibial artery and tibial nerve. Toprevent such complications, Lamm et al (28) recommended tarsaltunnel release for a correction angle >10�.

Ilizarov external fixator is an appealing alternative to opencorrection, because it can reduce the risk of skin problems or neuro-vascular complications by allowing for gradual correction rather thanacute correction. Inmost previous studies on the treatment of equinusdeformities, an Ilizarov external fixator was applied in combinationwith various open procedures. Therefore, it has been difficult to assesshowmuch correction can be achievedwith an Ilizarov external fixatoralone (11,24–27). To our knowledge, only 4 studies have been pub-lished on this subject. Hosny (29) reported good results with theirbloodless technique using only an Ilizarov fixator. Hosny (29) did notreport the ankle range of motion or the radiographic correction angle,making it difficult to precisely analyze the extent of correction. Melvinand Dahners (30) reported correction of equinus contracture �35�

with a dynamic technique using an Ilizarov fixator in pediatricpatients. Carmichael et al (1) also reported a correction of about 41�

with an Ilizarov fixator; however, these results also applied only topediatric patients. A study by Tsuchiya et al (31) was the only studythat used a method similar to that in our study, using an Ilizarovexternal fixator alone in adult patients. They reported an equinusdeformity correction of 36.1� (31).

Our results support the use of Ilizarov external fixation alone,without adjunctive soft tissueprocedures, in adult patientswith severeequinus deformities. We were able to obtain a mean correction of49.0� �17.4�, with amaximumobserved correction of 72�, 12.9� largerthan the mean correction of 36.1� reported in the only previous seriesof adult patients (31). The high level of correction might have resultedbecause our patients had very severe deformities. We did observesome recurrence after removal of the Ilizarov externalfixatorat the last

follow-up visit, with a mean loss of 10.0� � 5.0�, for a final meancorrection of 39.0� � 18.0�. Carmichael et al (1) also reported that arelapse after correction with an Ilizarov external fixator was commonin pediatric patients with burn contracture. Biedermann et al (32) alsodescribed a relatively high recurrence rate and found correction withan Ilizarov external fixator meaningful as an alternative technique butnot as afinal treatment technique. In our series, clinical correctionwiththe Ilizarov fixator continued �5� of ankle dorsiflexion; however, aslight recurrencewas found at the last follow-up visit inmost patients.Ankle dorsiflexionwas 5� in 1 patient (10%), 0� in 6 patients (60%),�5�

in 2 patients (20%), and�20� in 1 patient (10%). All the patients, exceptfor thepatientwith�20� of dorsiflexion,were able toachieve adequatecorrection to allow heel walking during gait (Fig. 3). The 1 patientwithsevere recurrence hadundergone 6 surgical procedures, including skingrafting and sural flaps around the foot and ankle for the treatment ofan open tibial fracture and subsequent osteomyelitis. Gradual correc-tion using an Ilizarov external fixator was performed for 50 days until5� of ankle dorsiflexionhadbeen achieved. The Ilizarovexternalfixatorwasmaintained foranother14days, anda short leg castwas applied forthe next 28 days for additional fixation. However, the equinus defor-mity recurred gradually during the follow-up period, demonstrating�20� of ankle dorsiflexion at the last follow-up visit. To avoid suchpostcorrection recurrences, we have continued to recommend the useof an ankle foot orthosis even after completion of the correction. Theankle footorthosis helpedprevent recurrence of theequinusdeformityinmost patients, but itwas not veryeffective for the 1patient, inwhomheel walking was impossible because of the severe recurrence. Therelatively severe recurrence in 1 patient was attributable to the verysevere equinus deformity and poor soft tissue envelope observedpreoperatively. Additional surgical treatment was also consideredwhen necessary; however, no additional surgery was performed forrecurrence in the present study, because the patient with �20� ofdorsiflexion was satisfied with the correction angle.

Although recurrence of equinus deformities, determined by theradiographic measure using the lateral tibial angle, had developedat the last follow-up visit, we obtained satisfactory clinical results.Specifically, the range of motion examination showed a meancorrection of ankle dorsiflexion of 53.0� � 21.4� at the last follow-upvisit. This was 14� greater than themean radiologic correction angle of39.0� � 18.0�. This suggests a possible measurement error betweenthe clinical measure of the ankle range of motion and the radiologicmeasurement. However, our clinical observationwas that some of thedifference resulted from additional correction in the midfoot jointthat was not reflected on the ankle radiographs. Clinically, weobserved significant improvement in ankle dorsiflexion and heelcontact on ambulation. The results of our study support the use of theIlizarov external fixator alone, without adjunctive soft tissue

B.O. Jeong et al. / The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery 54 (2015) 821–825 825

procedures, in particular, to reduce the complication risks in patientswith skin and soft tissue problems.

In our series, no severe skin or soft tissue complications wereobserved, except for mild pin site infections in 3 patients (30%).Although we did not perform tarsal tunnel release in correcting de-formities by a mean of 49.0� � 17.4�, no neurovascular complicationsoccurred. This might have been because most of the patients in ourstudy had an equinus deformity without severe varus. However, itwas more likely the result of the gradual correction made possibleusing the Ilizarov external fixator. Our study reported fewer pin siteinfections than other studies. The patients were trained to performpin site dressings before undertaking the daily dressing changes.

In the present study, we used an Ilizarov external fixator to correctthe equinus deformities in all 10 patients. The Ilizarov external fixator,which achieves correction through a manual adjustment program, isdistinguished from the Taylor spatial frame (Smiths & Nephew,Andover, MA), which relies on a computer-based program (24). TheTaylor spatial frame is able to correct complicated deformities moreprecisely and predictably than any other external fixator system.Compared with the Ilizarov external fixator, it requires a shorterlearning curve and does not need the application of multiple hinges tocorrect multiplanar deformities (25). However, the Ilizarov externalfixator is a powerful and efficient method of correction and more costeffective than the Taylor spatial frame (11). We achieved successfuloutcomes with the Ilizarov external fixator using the uniplane hingesystem, because all the patients in our study had simple equinusdeformities that were not associated with varus deformities. Bothsystems can provide correction in a gradual and controlled mannerover several weeks. The results of our study indicate that the conceptof gradual correction of equinus deformities is important and that thetype of an external fixation system to be applied depends on thecondition of the patient and surgeon preference.

The limitations of the present study included the retrospectivedesign, small sample size, and short follow-up period. In addition, theetiology and duration of equinus deformity and the period requiredfor correction varied among the patients. Despite this variability, weobtained satisfactory correction without severe complications andhave confirmed the efficacy of equinus deformity treatment with anIlizarov external fixator.

In conclusion, we obtained a mean correction angle of49.0� � 17.4� without severe complications and with statisticallysignificant improvement in the ankle range of motion in patients withan equinus deformity using the Ilizarov external fixator alone withoutopen procedures such as soft tissue release or osteotomy. This methodis particularly useful for patients who have a poor soft tissue envelopeand are at a high risk of complications from open procedures. Theseresults also support the use of gradual correction with an Ilizarovexternal fixator before open procedures to minimize the extent ofprocedures required to obtain an adequate plantigrade position.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nelson F. SooHoo, MD, for his review of theirreport.

References

1. Carmichael KD, Maxwell SC, Calhoun JH. Recurrence rates of burn contractureankle equinus and other foot deformities in children treated with Ilizarov fixation.J Pediatr Orthop 25:523–528, 2005.

2. Hahn SB, Park HJ, Park HW, Kang HJ, Cho JH. Treatment of severe equinusdeformity associated with extensive scarring of the leg. Clin Orthop Relat Res393:250–257, 2001.

3. Hsu K, Kuo K, Hsu R. Correction of foot deformity by the Ilizarov method in apatient with Segawa disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res 314:199–202, 1995.

4. Botte MJ, Bruffey JD, Copp SN, Colwell CW. Surgical reconstruction of acquiredspastic foot and ankle deformity. Foot Ankle Clin 5:381–416, 2000.

5. Banks HH, Green WT. The correction of equinus deformity in cerebral palsy. J BoneJoint Surg Am 40:1359–1379, 1958.

6. Graham HK, Fixsen JA. Lengthening of the calcaneal tendon in spastic hemiplegiaby the White slide technique: a long-term review. J Bone Joint Surg Br 70:472–475,1988.

7. Hillstrom HJ, Perlberg G, Siegler S, Sanner WH, Hice GA, Downey M,Stienstra J, Acello A, Neary MT, Kugler F. Objective identification of ankleequinus deformity and resulting contracture. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc81:519–524, 1991.

8. David A, Lewandrowski KU, Josten C, Ekkernkamp A, Clasbrummel B, Muhr G.Surgical correction of talipes equinovarus following foot and leg compartmentsyndrome. Foot Ankle Int 17:334–339, 1996.

9. De La Huerta F. Correction of neglected club foot by the Ilizarov method. ClinOrthop 301:89–93, 1994.

10. Haritidis JH, Kirkos JM, Provellegios SM, Zachos AD. Long term results oftriple arthrodesis: 42 cases followed for 25 years. Foot Ankle Int 15:548–551,1994.

11. Kocao�glu M, Eralp L, Atalar AC, Bilen FE. Correction of complex foot deformitiesusing the lIizarov external fixator. J Foot Ankle Surg 41:30–39, 2002.

12. Mirzayan M, Early SD, Matthys GA, Thordarson DB. Single stage talectomy andtibiocalcaneal arthrodesis as a salvage of severe, rigid equinovarus deformity. FootAnkle Int 22:209–213, 2001.

13. Philbin T. Rigid equinovarus deformity corrected with a multiplanar external fix-ator. Foot Ankle Spec 1:247–249, 2008.

14. Redfern JC, Thordarson DB. Achilles lengthening/posterior tibial tenotomy withimmediate weightbearing for patients with significant comorbidities. Foot AnkleInt 29:325–328, 2008.

15. Sammarco GJ, Taylor R. Cavovarus foot treated with a combined calcaneus meta-tarsal osteotomies. Foot Ankle Int 22:19–30, 2001.

16. Wukich DK, Dial D. Equinovarus deformity correction with the Taylor spatialframe. Oper Tech Orthop 16:18–22, 2006.

17. Yamamoto H, Okumura S, Morita S, Obata K, Furuya K. Surgical correction of footdeformities after stroke. Clin Orthop 282:213–218, 1992.

18. Younger SE, Hansen ST Jr. Adult cavovarus foot. J Am Acad Orthop Surg13:302–315, 2005.

19. Calhoun JH, Evans EB, Herndon DN. Techniques for the management of burncontracture with the Ilizarov fixator. Clin Orthop 280:117–124, 1991.

20. Grant AD, Atar D, LehmanWB. The Ilizarov technique in correction of complex footdeformities. Clin Orthop 280:94–103, 1992.

21. Huang S-C. Soft tissue contracture of the knee or ankle treated by Ilizarov tech-nique: high recurrence rate in 26 patients followed for 3–6 years. Acta OrthopScand 67:443–449, 1996.

22. Oganesyan OV, Istomina IS, Kuzmin VI. Treatment of equinocavovarus deformity inadults with the use of a hinged distraction apparatus. J Bone Joint Surg Am78:546–556, 1996.

23. Oganesyan OV, Istomina IS. Talipes equinocavovarus deformities corrected withthe aid of hinged distraction apparatus. Clin Orthop 266:42–50, 1991.

24. Cuttica DJ, Decarbo WT, Philbin TM. Correction of rigid equinovarus deformityusing a multiplanar external fixator. Foot Ankle Int 32:S533–539, 2011.

25. Eidelman M, Katzman A. Treatment of arthrogrypotic foot deformities with theTaylor spatial frame. J Pediatr Orthop 31:429–434, 2011.

26. Lee DY, Choi IH, Yoo WJ, Lee SJ, Cho TJ. Application of the Ilizarov technique to thecorrection of neurologic equinocavovarus foot deformity. Clin Orthop Relat Res469:860–867, 2011.

27. Shu H, Ma B, Kan S, Wang H, Shao H, Watson JT. Treatment of posttraumaticequinus deformity and concomitant soft tissue defects of the heel. J Trauma71:1699–1704, 2011.

28. Lamm BM, Paley D, Testani M, Herzenberg JE. Tarsal tunnel decompression in leglengthening and deformity correction of the foot and ankle. J Foot ankle Surg46:201–206, 2007.

29. Hosny GA. Correction of foot deformities by the Ilizarov method withoutcorrective osteotomies or soft tissue release. J Pediatr Orthop B 11:121–128,2002.

30. Melvin JS, Dahners LE. A technique for correction of equinus contracture using awire fixator and elastic tension. J Orthop Trauma 20:138–142, 2006.

31. Tsuchiya H, Sakurakichi K, Uehara K, Yamashiro T, Tomita K. Gradual closedcorrection of equinus contracture using the Ilizarov apparatus. J Orthop Sci8:802–806, 2003.

32. Biedermann R, Kaufmann G, Lair J, Bach C, Wachter R, Donnan L. High recurrenceafter calf lengthening with the Ilizarov apparatus for treatment of spastic equinusfoot deformity. J Pediatr Orthop B 16:125–128, 2007.