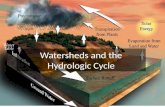

The Hydrologic Cycle .

-

date post

21-Dec-2015 -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

1

Transcript of The Hydrologic Cycle .

The Hydrologic Cyclehttp://nd.water.usgs.gov/ukraine/english/pictures/watercycle.html

Water as Property

• Water is unique. Why?– It is “a moving and cyclical resource”

• Water is a common pool resource– States generally claim ownership over water

• But, States have a trust responsibility to manage water resources to protect the public interest

• Water rights are usufructuary– Private persons obtain the right to use water– They don’t own it in the classic sense of property

Managing Water is Complicated • The amount of the resource is not fixed over time like other

resources– Unpredictable seasonal cycles and variations make the

availability of water at any given time uncertain

• But, water is essential to society

• We have plenty of water, but…– We don’t always have it where we need it– Some of it is contaminated or unusable– And our legal system does not always lead to the

efficient and fair distribution of water

• The global water crisis is a management crisis

Water and Geography

• Plentiful water in the East made it possible to radically transform the Eastern United States

• “Reclaiming” the West has been much harder (and much more expensive)– Despite hundreds of dams, some of an

almost unthinkable scale, much of the West remains a vast undeveloped landscape

Variability of Rainfall

• From rainforests to deserts

• Scarcity may occur even with abundant supplies if you cannot get water where it is needed

• Global rainfall– http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/fews

/ globe/anomalies.html

Water and Pollution

• 1.1 billion people lack access to an improved water supply

• 2.4 billion lack access to improved sanitation• In 2000, there were an estimated 2.2 million

deaths due to water-borne diseases• In the United States, we take clean water for

granted– But note that our water systems are susceptible to

terrorist attacks

Cadillac Desert• Water has made the development of the Western

United States possible

• But, water is available where it is needed in the West only because of elaborate reclamation projects– Projects capture spring snowmelt– The scale of mountain runoff during the spring is hard for

Easterners to imagine– Consider the political importance of water projects

• Still, it is a myth that the West is running out of water– In many states 95% or more of the water is going to

irrigate low value crops

The 100th MeridianImage courtesy of Geography at About.com

http://geography.about.com

Precipitation Map of the U.S.http://www.doi.gov/water2025/precip.html

Uses for Water

• Instream– Fish and wildlife; recreation; ecosystem

services (like water purification); navigation; hydropower; dilution

• Out of Stream– Irrigation; municipal water supply; industrial

uses

The Colorado River Basin

http://biology.usgs.gov/s+t/imagefiles/e063f01.htm

What Can the Great Lakes Basin Learn from the West?

• How is the Great Lakes Basin like the Colorado River?

• How is it different?

• Are the differences so great that the Colorado River system cannot offer relevant insights?

Water Institutions• From whom do people get water?

– Compare farmers with industrial users with small domestic users with city residents

• Note that quasi-governmental institutions play a significant role in many parts of the country– From drainage districts to irrigation districts to

water and power districts to sanitation districts– Ball v. James holds that these districts are

generally not subject to a one-person, one vote standard!

– Voting is often done by acreage.

The Nature of Water Supplies• People who use water either have their own

water “right” or they may rely on someone else’s water right

• Water “rights” are sometimes an incident of property ownership, and are sometimes granted by government agency through a permit

• Generally, no one pays for water. Water is free. Our water bill pays for the infrastructure needed to clean the water and bring the water into our home. The same is essentially true for farmers

Water Institutions• Where do people get there water?

– Urban and suburban residential users typically get their water from government or quasi-governmental agencies

• Municipalities, water districts

– Rural users often have private wells

– Farmers usually get their water from various types of water districts, including conservancy and irrigation districts

– Industrial users sometimes tap into municipal with small domestic users with city residents or sometimes have their own water supplies

Water Institutions

• Joint ditches (informal; contractual)

• Mutual ditch companies (typically non-profit corporations)

• Private companies (e.g., Ohio American)– http://www.oawc.com/awpr/ohaw/start/index.html

• Special purpose districts (quasi-governmental)– Irrigation districts and water conservancy districts

(like snowflakes—no two alike)

Special Purpose Water Districts

• Advantages—Preferred entities for federal contracts– Powers of eminent domain– General fee assessment powers (Tax power?)– Sanctioned by court order

• Special purpose districts are typically approved by order of a local district court

• Those who prefer not to be included can object on grounds that they will not benefit (but it can be tough to opt out)

• Fallbrook Irrigation District v. Bradley (Maria Bradley lost her land for refusal to pay assessment

Ball v. James, 451 U.S. 355• Salt River Project District

– Officials elected by voters who receive one vote for each acre of land they own in the district

– District includes more than one half the population of Arizona

– Persons who own less than one acre do not receive a vote

– District subsidizes water works with electricity sales– Is it a public utility?

• Can issue tax exempt bonds; • Property is not taxed; • Has eminent domain authority

– Is it subject to one person, one vote rule?• Would it matter whether the district has ad valorem (property)

taxing power. Why?

Irrigation Schematichttp://www.doi.gov/water2025/irrigation.html

Center-Pivot Sprinkler Patterns

http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/graphics/photos/k4904-20.htm

Center-Pivot Sprinklerhttp://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/WaterUse/Images/cp-spray3.jpg

Furrow Irrigationhttp://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/WaterUse/Images/furrow1.jpg

Earthen Ditchhttp://www.co.union.oh.us/soil-water-conservation/ditch_maintenance.htm

Parshall Flumehttp://wwwrcamnl.wr.usgs.gov/sws/fieldmethods/Images/instflum.jpg

Siphon Irrigationhttp://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/WaterUse/Questions/glossary.htm

Gated Pipehttp://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/WaterUse/Images/gated-pipe2.jpg

Valuing Water

• Consider the value of water to community at Put-in-Bay

Toledo Blade

August 25, 2004

Put-in-Bay's predicamentAN OUTBREAK of gastrointestinal illness that seems to

have South Bass Island and Put-in-Bay as a common link is in its second week without a definitive explanation or answer. Hopefully, the public can be reassured that an "A team" of investigators appears to be closing in. The number of people who say they became ill after visiting the popular resort island in Lake Erie off Port Clinton passed 750 on Monday, some of them from as far away as California, Florida, and Texas….

Externalities and the Cost of Water • Consider the vast costs that are imposed by externalities on

our water supplies

• The bill for making our water clean enough to drink is in the trillions of dollars

• But the majority of these costs are imposed by humans. Society accepts pollution from a wide range of sources -- farms, factories, wetland removal, development – and none pay for the costs they impose on water supplies– They don’t pay for the direct costs of treating the water to

remove the pollution– And they don’t pay the indirect costs associated with lower

value for the water resources as a recreational resource

• Why?

U.S. Dam Policy

• 5,500 large dams; 100,000 small dams

• 95% of all dams are private; but the largest are all public

• Why build dams? What are the benefits?– Hydropower– Irrigation (store water for when needed)– Flood control– Flat water recreation

Environmental Cost of Dams• Severe ecosystem disruption

– Seasonal flows disrupted– Flow itself disrupted– Temperature changes– Trap stream sediment

• Consider the Colorado River

– Adverse impacts on wildlife and riverine habitat

• Disruption of fish runs• Salmon in Pacific Northwest

Other Costs

• Promotes rent-seeking behavior– Dams are often built even when they

cannot possibly be justified on economic grounds

• Disrupts markets and interferes with “efficient” choices

• Decommissioning costs

Government Role

• The big dams are all subsidized by the government– Bureau of Reclamation– Army Corps of Engineers– Tennessee Valley Authority

• Consider the “public works” nature of many of the projects

• Why were subsidies necessary?

Bureau of Reclamation

• Reclamation Act of 1902

– Allowed interest free loans for water projects to be paid over ten years

– Available to farmers who owned no more than 160 acres and lived on the land (residency)

1939 Amendments • Extended pay back period on interest free loans to 50

years, which amounted to a 90% subsidy• Rollover policy allowed the Bureau to extend the 50 year

period to the time the last unit of a project was completed• The result has been that in some cases the pay back

period extends out for nearly 100 years• Specifically authorized shifting costs from irrigators to

electrical consumers• Broad authority for further subsidies (water service

contracts) which allow Bureau to share construction costs • 160 acre limit honored in the breach (By 1979, more

than 75% of water furnished from Bureau projects was going to farms exceeding 160 acre limit.)

Central Valley Project Example• Rollover policy: CVP first authorized as a federal

project in 1937. Repayment has been extended through 2030

• According to Natural Resources Defense Council study, subsidies for CVP amount to $300 million/year -- $183/acre . Highest subsidies going to Westlands which was fouling Kesterson Wildlife Refuge

• Subsidies for surplus crops. In 1980's 59% of CVP land was growing surplus crops.

1982 Reform Act• Abolished residency requirements• Extended acreage limit to 960 acres• Allowed leased lands, but "full cost" pricing

for tracts in excess of 960 acres• Farmers had to renegotiate under the new

law by 1987 or be subject to full cost pricing for all lands in excess of 160 acres.

• Peterson v. United States, 899 F.2d 799 (9th Cir. 1990): Court upheld the "hammer" clause in Reform Act. Court found that water users did not have a vested contract right to the water (beyond 160 acres) at the contract price.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers• Much more prominent in the East and Midwest,

but some presence in the West as well

• Projects not so much for irrigation, but rather for flood control, hydropower, and navigation

• As with the Bureau many Corps projects cannot be justified economically– Corps introduced “river basin accounting” whereby

the vast subsidies to one project could be hidden by lumping it together with other projects (like hydro) that make a lot of money

Colorado River: Grand Canyonhttp://www.nps.gov/grca/grandcanyon/maps/

Bureau of ReclamationPhoto: The Glen Canyon

Damhttp://www.usbr.gov/power/data/sites/glencany/glencnyn.jpg

Lake Powell (2003)The white area shows the high-water mark from 1980

Image courtesy of Nieka Apell and Ken Varnumhttp://varnum.org/utah/index.html

The Proposal to Drain Lake Powell

• Pros– Ecology– Fish– Waste– Silt– Risk of spillway failure

• Cons– Silt threat is overstated– Restoration will take centuries– Waste is overstated

Denver Post: July 5, 2004• “Plummeting water levels in Lake Powell have drastically

slashed electricity generation at the reservoir's Glen Canyon Dam, forcing power authorities to cut deliveries to utilities from the Front Range to Provo, Utah.”

• “Federal officials fear that $100 million worth of hydropower generated annually by Lake Powell could dry up completely by 2009 - if dam managers continue releasing water at pre-drought rates.”

• “The five-year drought has already drained Lake Powell to 43 percent of capacity ….That lost … "hydraulic head," has slashed the dam's generating capacity by some 30 percent….”

• Lake Powell was 95% full at the beginning of 2000!

Santa Fe New MexicanSeptember 10, 2004

• “$20 million plan for generating station in drought-stricken Lake Powell”– The article discusses a $20 million proposal to drill

new tunnels into the sandstone walls to divert water to the Navajo Generating Station for cooling water. The plant helps run the pumps needed to deliver Colorado River water to the Phoenix area

– Current tunnels may go dry if Lake Powell drops another 100’. If the drought continues the water may drop that much by 2006. This would also force closure of the hydro station.

Water Allocation Law

• Riparian systems have historically dominated the Eastern United States

• Prior appropriation systems have historically dominated the West

• Many Eastern states are moving toward permit systems that arguably have more in common with prior appropriation law than riparian law – And Western states now clearly recognize instream

uses as deserving of protection

Harris v. Brooks• Mashburn (Harris’ lessee) operates a boating

and fishing camp

• Brooks irrigates a rice crop

• Brooks’ use of water dropped lake levels to the point that Mashburn had to give up his business– Suppose that Brooks is required to give up farming to

provide water for Mashburn

• Who wins? Is this the best result? The most “efficient” result?

Classic Riparian Doctrine• Who is entitled to riparian water rights?

• What limits, if any, apply to the place of use? – “On-tract" limitation, but most states allow off-tract use if no

objection by other riparians, or if no harm, or if reasonable – Rights must be used in watershed of origin

• How much water can a riparian use?– Natural flow theory evolved to reasonable use/correlative rights

theory– More recently, some states follow Restatement (2d) of Torts test– Rights do not depend on extent of riparian frontage, but that may

affect what is deemed reasonable

• For what purposes?– Absolute right to use water for domestic purposes

The Nature of Riparian Rights

• Right to make reasonable use of water (correlative with all other riparians)

• Right to use surface for recreation, fishing, boating– In most jurisdictions extends to surface of entire

water body, not just frontage or wedge

• Right to wharf out – Requires federal permit on “navigable waters”

• Surface rights and wharfing rights apply across the United States regardless of water allocation doctrine

Restatement of Torts § 850

• Liability Rule: Riparian is liable for unreasonable uses that cause harm

• No cause of action unless harm occurs

Restatement of Torts § 850A(A balancing test)

• (a) reasonableness of use;

• (b) suitability to watercourse;

• (c) economic value;

• (d) social value of use;

• (e) extent and amount of harm;

• (f) practicality of avoiding harm by adjusting uses or methods;

• (g) practicality of avoiding harm by adjusting quantities used;

• (h) protection of existing uses;

• (i) justice of requiring person causing harm to bear cost. (Coase would say these are reciprocal harms.)

What’s wrong with the riparian doctrine?

• It lacks certainty. How so?

• It imposes artificial limits on place of use. How so?

• It is inefficient. Consider how conflicts are resolved in riparian jurisdictions.

• Should the entire doctrine be scrapped?– What are the alternatives?

Q & D 4: What lands qualify as riparian?

• “Source of title”: Only those tracts of land that have also included riparian lands qualify for water rights

• “Unity of Title”: All tracts of land that are presently riparian qualify for riparian rights

• Note however, that riparian rights can be severed by an express conveyance of such rights. – The grantee stands in the shoes of the riparian

grantor.

Botton v. State (note 7)• State owns a small tract of land with a

boat launch and access for fishing on Phantom Lake – a 63 acre lake that is non-navigable for title purposes

• Riparian owners complain that allowing public access is an unreasonable exercise of the State’s riparian rights

• Is the State like any other riparian for purposes of the law? If not, why not?

Protecting Streams in Riparian States

• Note that, in theory, only riparians can protect natural stream flows and water levels in riparian states– They can assert reasonable rights to fish, recreate

etc.– They can claim that uses that harm the public

interest are not reasonable– The State, as trustee, might also be in a position to

make such public interest claims

• States can also exert political pressure on users to protect stream flows

Eastern Permit Systems

• Misleading to call them “regulated riparian” systems– The fundamental principal that water rights attach to

riparian land is generally rejected– In its place, water users are required to obtain a permit– While temporal priority is not determinative, it is often a

consideration in whether to grant or renew a permit– Permits are often limited to a term of years

• Note that the Charter Annex proposal would largely move the Great Lakes States toward this type of system

Permit Systems• Approximately 19 Eastern/Midwestern states have some kind

of permit system but they vary greatly

• The chief advantage is that they allow the State to make a judgment about adverse impacts BEFORE the use goes forward– Under the riparian systems once a use has commenced,

and reliance on that use has developed, it becomes very hard to force changes

• Moreover, it can only be done in court

• Ohio Revised Code §§ 1501 (permits); 1521 (registration)– http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/water/orclaw/ORC_all_main.htm– http://www.dnr.state.oh.us/water/orclaw/waterwithdraw_law_main.htm

Franco-Am. Charolaise, Ltd. RB v. Okla. W• City wants to increase appropriation for municipal purposes;

riparians claim that the City's use interferes with their reasonable riparian uses.

• Legislature passed law in 1963 abolishing unused riparian rights– Under this law, pre-existing riparian rights had to be

“perfected” under statutory mechanism

• Court finds that the legislation effected a taking in violation of State constitution– Is an unused riparian right a vested property right?– Consider the nature of water rights – Dissent suggests riparian rights are subject to limits and

even forfeiture. Majority misperceives the “denominator”

Compare: In Re: Waters of Long Valley Creek

• Stream adjudication process (California)– Ramelli claimed unused riparian rights.

• Court found that uncertainty of unused riparian rights creates problems for state water management.

• Court acknowledged that State cannot constitutionally extinguish unused riparian rights

• Nonetheless, the Court allows the State to subordinate unused riparian rights to other uses – This effectively extinguishes them. Why?

Prior Appropriation

• Dominant system in the Western U.S. • Basic principles:

– Water occurring in natural condition is held by the state, in trust for the people

• Excludes diffuse surface water; unconnected groundwater• Private users can acquire a vested right to use water for a

particular purposes

– Water rights limited to beneficial uses– Priority of appropriation gives the better right

• “first in time, first in right”• Usually determined by date of permit application (compare

Colorado)• Senior rights must be fully satisfied before juniors receive

water (No sharing in times of shortage)

– Riparian rights to “wharf out” and use water for recreational purposes remain

Historical Context• Mineral rights in Western mining camps were

acquired by the first person to possess and maintain the claim– Water was needed to process minerals– Because limited supplies were available in many

parts of the West, water was allocated in the same way as minerals

• When the farmers began settling the West, they realized that the system devised by the miners was far better suited to their interests than the riparian system – They received secure and often very generous rights

at the expense of future settlers

Legal Rules and Issues• “Beneficial use” is “the basis, the measure, and the

limit of the water right.” – May be relevant to type of use and quantity of water– Water quantity relates to waste (“duty” of water)– Rights are vested but amount of water may be in flux

• While priority typically determined from date of application, paper rights are not enough

• Change of use or place of use allowed only if “no injury” to all existing appropriators

• Water rights may be lost through non-use– Abandonment– Forfeiture

• Problems relating to instream flows• Application of the public interest standard

Other Related Issues

• Hybrid systems– Along 100th meridian and on West coast

• Tributary groundwater– Interconnected with surface water– Conjunctive management and use

• Federal reserved water rights– Implied rights associated with reserved lands

• Pueblo rights and prescriptive rights are rare (and thus not especially important)

Visualizing the System

• Typically applies in areas with mountains which store winter snow and release large quantities of water in Spring

• Seniors tend to be downstream; juniors upstream. – makes it easier for juniors to steal senior

water!

• return flows• water quality issues

Typical Permit Process• Water rights are issued by the State as follows:

– Prospective water user files an application– Application is approved by State water official (water

permit)– Water is used for the approved purpose (the applicant

proves up on her right by demonstrating actual use for the approved purpose)

– Water right is granted

• Colorado is somewhat unique in having water rights issued by courts. In all other PA states, water rights are issued by a state water official or agency

Prior Appropriation• Suppose only 20 cfs available• Suppose 90% of water lost

between Jones and Williams• Suppose Compute, Inc employs

more• Does it matter that stream is

dewatered?• Does it matter that user is not

riparian?• Can Computer, Inc. buy Jones’

right?• Can you acquire a water right

that may be available only in wet years?

• Can you hold water without using it?

Storage (Reservoir) Rights• Water from reservoirs raises unique issues

– Storage rights are generally for a volume of water– Reservoirs are usually subject to the one-filling rule– Must take water when told (generally in the early

Spring) or it is credited against account– Carry-over storage counts toward current allocation.

• Generally, the initial diversion from the stream is the one that must satisfy the priority requirement

• Secondary users of reservoir water generally fall outside the PA system

Prior Appropriation Criticized• It may not make sense to fully protect an inefficient

senior user at the expense of a more efficient junior user– Sufficient certainty could be maintained by protecting

the senior’s right only to the point of maximizing efficient

• Does the prior appropriation doctrine have sufficient flexibility to adapt itself to changing values and needs?– Is the doctrine too cumbersome to efficiently

accommodate water transfers?

• Despite theory of state ownership, instream flows and values were historically ignored – Changing today, but instream protections almost

always suffer from late priorities

Beneficial Use

• “The basis, the measure, and the limit” of a water right– Professor Neuman notes that concept is

rarely used to demand true conservation

– But conceivably, it could be used to demand much more efficient water uses

– IID example

Imperial Irrigation District

• AREA SERVED– Gross acreage 1,061,637 – Irrigated area 462,202– Average Agricultural use per year 5.6 AF/acre

(varies per crop and soil type)– Water delivered thru

All-American Canal 3.0 MAF/yr.– http://www.iid.com/water/works.html

NOTE: Ninety-eight percent of the water IID transports is used for agriculture. The remaining two percent is then delivered to nine Imperial Valley cities, treated to safe drinking water standards, and distributed to residential water customers

Imperial Irrigation District

• Map– http://www.waterrights.ca.gov/IID/IIDHearingData/L

ocalPublish/IID_minority_121801.pdf

• Salton Sea was formed between 1905 and 1907 when poorly constructed irrigation canals burst and Salton Basin received almost the entire flow of the Colorado River for more than a year. The Sea has continued to exist as a result of runoff from IID irrigation

IID Case• John Elmore (a farmer) owned land near Salton Sea

– Threatened with inundation by rising sea levels

• Water Resources Board requires IID to develop a conservation plan – No doubt that the intrusion on IID’s water rights was

“substantial”– But it did not necessarily interfere with vested rights– Water rights are limited to reasonable uses– Using water for beneficial purposes may nonetheless

be unreasonable– “Everything is in the process of changing or becoming

in water law”

Typical Permit Process• Water rights are issued by the State as follows:

1. Prospective water user files an application2. Application is approved by State water official (water

permit)3. Water is used for the approved purpose. (The

applicant proves up on her right by demonstrating actual use for the approved purpose)

4. Water right is granted

• Colorado is somewhat unique in having water rights issued by courts. In all other PA states, water rights are issued by a state water official or agency

The Public Interest• Increasingly important in allocating water rights

– But application of public interest standard is uneven at best

• In granting permits to divert water, how should the States consider the public interest?

• Balancing/opportunity cost approach in California Code (page 761) is becoming more common– Alaska code takes a similar approach

• Burden of proof is generally on the applicant

• The public interest arises in both initial applications and water transfers– But see Sleeper case (N.M) and Dep’t of Ecology case (Wash.)

Instream Flows• Many instream flows remain available to

protect because – Large downstream users demand that water

remain in the stream to their headgate– Many prized streams are in higher elevation

lands, closer to the headwaters on public lands and above irrigation areas

• Early problems with States that required a “diversion”

Preserving Instream Flows in PA States• Use the public interest standard, where available, to deny

applications that would interfere with stream flows.

• Deny new applications on streams that would interfere with minimum flow levels

• Issue appropriations to State Game and Fish agencies or private parties for an instream use– This last option is the most common although only a few

states allow private parties to holds instream flows rights (See Thompson article)

• Efforts to reallocate existing rights to instream flows are controversial and they have not proved very successful.

• NOTE 3: Preserving stream flows in riparian states is easier in theory than in practice.

The Public Trust Doctrine

• Illinois Central RR. v. Illinois (p. 105)– State legislature authorized the sale of the bed of a

significant portion of Chicago Harbor (in Lake Michigan) to the railroad.

– Several years later the State repealed the legislation authorizing the sale.

– The Railroad sued, alleging that their rights had vested.

– The U.S. Supreme Court held that title to the bed of a navigable lake was held in trust for all the people and that the railroad grant was therefore revocable

– The State holds trust property as trustee– Is the notion of the state as trustee for water

resources applicable in riparian states?

Federal Water

Projects in California

http://www.water.ca.gov/maps/federal.cfm

State Water Projects

in California

http://www.water.ca.gov/maps/state.cfm

Local Water Projects

in California

http://www.water.ca.gov/maps/local.cfm

Mono Lakehttp://www.parks.ca.gov/lat_long_map/default.asp?lvl_id=151&type=2

National Audubon Society v. Superior Court of Alpine County

• Court tries to reconcile the public trust doctrine with the prior appropriation doctrine

• Is there a conflict? How does the court reconcile the two doctrines?

• How does the public trust doctrine affect California water rights?– Does it apply to riparian rights in California?

Q & D: Mono Lake Decision• Could parties have used “beneficial use” or

“public interest” doctrines to limit LA’s water rights?

• Note that the aqueduct was subject to a right-of-way issued by the federal government. Does that offer any possibilities?

• Suppose the Mono Lake brine shrimp had been designated an endangered species?

• Once LA’s rights were readjusted, does LA then have a vested right to what remains?

Q & D: Mono Lake• Can a State renounce its public trust in

managing the State’s water resources?– Consider that the State gives water rights to the first

applicant without charge– Does it matter whether the State claims ownership of

the water?

• What’s the difference between public trust and public interest?– Consider that public interest protections may affect a

wide range of values impacted by water resource use– The public trust arises from the public’s ownership of

the water itself

Groundwater• Why is groundwater important?

– A much more significant resource than surface water

– If you consider only fresh water resources, essentially removing ocean water, ground-water accounts for 2/3 of the fresh water resources of the world

– If you further remove glaciers and ice caps and consider only ACTIVE groundwater regimes, groundwater makes up 95% of all of the remaining freshwater

– 3.5% comes from surface water and 1.5% from soil moisture

Confined vs. Unconfined Aquifers

• Confined aquifers produce artesian wells– Potentiometric surface: pressure surface.

• The level at which the water will rise in a well drilled into a confined aquifer.

• Unconfined or water table aquifers– Water in a well in an unconfined aquifer will

rise to the level of water table.– Unsaturated zone (vadose/zone of aeration)– Tension-saturated zone - capillary fringe.

Groundwater Concepts and Terms• “Cone of depression”

– The inverted cone that forms around the pressure surface of an artesian well, or in the aquifer for a water table well.

• Groundwater is generally measured in gallons per minute (1 gpm = .00224 cfs; 446 gpm = 1cfs)

• Porosity (amount of space in voids) – Storativity depends on porosity.

• Permeability (ability to transmit water) – Transmissivity depends on permeability.

The Perils of Groundwater Pumping• Groundwater use is increasing at a much faster pace than

surface water– 2/3 for agriculture– 11% for mining

• Groundwater “mining” more common– Can cause subsidence and loss of storage

• Problems – Mineral development breaches aquifers– Bottled water industry focuses on headwaters– Irrigation needed to satisfy the market

(McDonald’s French fries)

Groundwater Diagrams

• http://www.arc.losrios.edu/~borougt/GroundwaterDiagrams.htm

Cone of Depressionhttp://www.dnr.state.wi.us/org/water/dwg/OpCert/HTML/chapter3/wells4c.htm

Saltwater Intrusion

http://geopubs.wr.usgs.gov/fact-sheet/fs030-02/

Groundwater Doctrines

RULE

PRINCIPLE

PLACE OF USE LIMITS

Absolute Ownership/English Rule

Rule of capture

No limits

American Reasonable Use

Rule of capture

On tract limits; reasonable use limits (can use off-tract if no adverse impacts on others)

Restatement § 858

Shared use; liable to others for unreasonable harm caused by extractions in excess of reasonable share

no limits on place of useOhio adopted this rule in Cline v. American Aggregates,

Prior Appropriation

Priority

no limits on place of use; beneficial use/ maximization of resource

Correlative Rights

Shared use

On-tract limits unless other on-tract rights met; rights shared w/ other landowners

Sample Aquifer5000 acre feet of water in storage; 500 AF annual recharge

Francis Farmer owns 320 acres; farms the land; withdraws 1000 AF/year, half goes back as recharge; first in time; 400 foot deep well

Randy Rancher owns 160 acres; withdraws 500 AF/year for dude ranch and aquatic park on site; 100% consumptive system; 1000 foot deep well

Prince Power Company owns 160 acres; exports 500 AF/year to power plant off-site; 100% consumptive use; 1000 foot deep well

Hubbard v. Dep’t of Ecology• Hubbard had groundwater permits

– Conditioned upon requirement that they would have to stop pumping when water levels fell below minimum flows

– But the impact from the Hubbard’s pumping was minimal (0.004% of river’s flow during low flow – 4 gallons of every 100,000 gallons)

– Should Washington treat the groundwater permits as part of the surface water system?

• Note that Colorado has a similarly strict rule– If the amount withdrawn will deplete the flow by 0.1%

within 100 years then it is “tributary groundwater.”

Conjunctive Management of Groundwater• Term used to describe joint management of interconnected

surface and groundwater systems

• The result in Hubbard allows surface water laws to trump groundwater laws– This does not always lead to an efficient result– Consider Templeton v. Pecos Valley (NM)

• Consider Alamosa-La Jara Water Users v. Gould(Colorado, 1983)– Groundwater aquifers contained 2 billion acre feet– Surface and groundwater was interconnected– Junior well users interfered with senior surface users but

plenty of water for everyone if everyone used groundwater– Court required seniors to shift to groundwater to maximize

use of water

Q & D: Groundwater• Consider how the State of Washington might better address the

Hubbard’s situation

• Consider the cumulative impact of small domestic users• 15 million private wells• If they average 25 gpm that’s 375 million gallons/minute

• Problems of safe yield– Usually defined to mean the amount of water you can remove

without mining the aquifer– Should States limit withdrawals to the “safe yield”?– What if the aquifer has limited annual recharge?– Colorado has a “3-mile test”

• When a new groundwater application is filed they ask whether the aquifer within a 3 mile radius of the well would be depleted by more than 40% after 25 years of operating the well

Water Federalism• State is the primary authority on water resource

management– Do States “own” the water? At a minimum, States

have regulatory power over water • A long tradition of federal acquiescence in State

control– Arguably States are not owners in a proprietary

sense– Rather they serve as a trustee for a public resource

• Consider Irwin v. Phillips– California Supreme Court adjudicates water rights

as between two trespassers on the public lands

Federal Statutes• Mining Law of 1866 recognized appropriative water rights of

miners as against later patentees

• Desert Lands Act of 1877 – The Supreme Court suggests that the DLA severed the

water from the public domain and made their allocation subject to State law

• Reclamation Act of 1902– Requires Secretary of the Interior to follow State law in

carrying out the Act– Construed to mean that Secretary must seek State

permits for federal water projects

• Was there any remaining role for the federal government?

Federal Authority Over Water

• Despite its acquiescence to State authority, the federal government continues to play an important role in water resource management– Commerce power and regulation of navigation

gave rise to Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899• Corps of Engineers issues permits for obstructions to

navigation on navigable waters

– Could Western States nonetheless impose prior appropriation on federal lands throughout the West?

• United States v. Rio Grande Dam suggests not

Federal Reserved Water Rights:The Winters Doctrine

• Winters v. United States– Milk River runs along northern boundary of the Fort

Belknap Indian Reservation• What was the purpose of the reservation of lands

for the tribes?– “The power of the government to reserve waters and

exempt them from appropriation under the state laws is not denied, and could not be.”

– Why weren’t these reserved rights repealed by the Act admitting Montana into the Union?

• Extreme to believe that Congress would have repealed the reservation one year after reserved

– How much water was reserved for the Indians?

Q & D: Indian Reserved Rights

• What is the source of the government’s power to reserve water?

• Under equal footing doctrine, Consider that a reservation is NOT a grant from the Indians

• Quantification of Indian Reserved Rights– PIA standard for agricultural rights– Instream flows for fishing rights– PIA standard reserves a lot of water

• some judges seem inclined to change it• 4-4 vote in In Re: Adjudication of the Big Horn

Quantification: McCarran Amendment

• What if a State wants to know how much water Indian Tribes hold?

• McCarran Amendment is a limited waiver of sovereign immunity– Authorizes adjudication of federal water rights (Indian

and non-Indian), but only in general stream adjudications– But need not be an entire river system

• The Supreme Court has generally held that federal courts should defer to State courts in hearing these disputes.

Cappaert v. United States

• President Truman designated the Devil’s Hole National Monument in 1952 to protect an underground desert and a unique fish species – the desert pupfish

• Cappaert petitioners own a large ranch where they grow crops and graze cattle– They operate large groundwater wells that are drawing

down the aquifer and causing level of the pool to decline– Water rights were acquired after 1952

• The Proclamation reserved sufficient water to carry out the purposes of the reservation – but no more

• Does the doctrine differ for non-Indian rights?

United States v. New Mexico• Gila National Forest

– U.S. claims reserved waters for instream flows for aesthetic, recreational and fish preservation purposes

• Organic Administration Act of 1897 established forests for only two purposes –– to secure “favorable conditions of water flows,” and – “to furnish a continuous supply of timber”– NOTE: Dissent suggests there are really three purposes

• MUSYA of 1960 expanded purposes for which forests were established to include outdoor recreation, range, timber, watershed, and wildlife and fish purposes.– Court holds that water not reserved for the “secondary”

purposes set out in MUSYA. Is this true?– Was MUSYA properly before the Court? Is its holding dictum?

Reserved Rights in National Forests• In New Mexico, the Court reasons that “in the

case of the Rio Mimbres, a river [that] is fully appropriated, federal reserved water rights will frequently require a gallon for gallon reduction in the amount of water available for water needy state and private appropriators.” – In the case of the Gila Forest, at least, this is

almost certainly not true. Why?

– What was the basis for the dissent?

• Developments in fluvial geomorphology suggest that instream flows may be needed to secure favorable water flows

Reserved Rights in Riparian States

• What rules should apply?

• Consider the Great Lakes– Numerous American tribes; over 100 First

Nations– Do they all have rights? If so, how can

they be quantified?

National Forests and Grasslandshttp://roadless.fs.fed.us/maps/usmap2.shtml

Other Reserved Lands• National Parks, National Monuments, National Recreation and

Conservation Areas

• National Wildlife Refuges

• Wilderness Areas– Potlatch decision was reversed on rehearing

• Wild and Scenic Rivers

• BLM Public Lands (unreserved lands)

• Military reservations

Reserved Rights by Legislation

• More and more, Congress (and the President) specifically indicates whether water rights are reserved – Wilderness legislation– Wild and Scenic Rivers legislation– National monuments

• Often, legislation is held back because no resolution on water rights

Reserved Rights by Settlement

• Federal government settled with Montana for several Parks, Refuges, Wilderness Areas, etc.

• Can States settle with Tribes? Is the federal government an indispensable party?

Reserved Rights

• Does the federal government have an affirmative obligation to assert such rights?– Public trust?

• Can the federal government be bound by state administrative proceedings?

• Are federal rights unfairly treated in state court system?

Problem Exercise: Wilderness Water Rights

• Does the Wilderness Act create reserved water rights?– See 16 U.S.C. §§1131(c); 1133(a); 1133(d)(4);

1133(d)(5)– Central Idaho Wilderness Act

• Consider the way in which the Idaho Supreme Court decided the case and then reversed itself– NOTE: The federal government has not appealed

the Idaho Supreme Court’s second decision

Intersecting Federal Laws

• Clean Water Act– Section 401 (State certification)– Section 402 program (NPDES)– Section 404 program (wetlands)

• Endangered Species Act– Section 7 consultation– Section 9 takings

Clean Water Act, § 401State Certification of Federal Permits

• For any applicant for a federal permit or license that may result in a discharge into the navigable waters of the United States –– State must certify compliance with effluent

limits and ambient water quality standards

• This effectively gives States some measure of control over numerous federal projects, including dams, roads, mineral leases or licenses, timber sales, and perhaps even grazing permits

Clean Water Act, § 402• National pollution discharge elimination system

(NPDES)

• A federal permit program for discharges into navigable waters from a “point source”– State programs allow States to issue permits

• Different, technology-based standards established for pre-existing sources and new sources

• EPA has established emission standards for categories or classes of facilities

How does water quality impact water quantity?

• The solution to pollution is (sometimes) dilution

• Consider the Chicago Diversion– Estimated to reduce the levels of Lakes

Michigan and Huron by 6 cm (2 billion gallons per day)

– Changes the flow of the Chicago River so that it flows out of Lake Michigan rather than into Lake Michigan

– Flushing flows used to treat sewage water

Clean Water Act, § 404• Permits required for discharges of dredged and

fill material into navigable waters– Permits issued by the U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers– Normal farming, silviculture, ranching activities such

as plowing, seeding cultivation, minor drainage, harvesting, and upland soil conservation practices are exempt

• Navigable waters have historically included wetlands– Provide important ecosystem services, including

water filtering and purification, groundwater recharge, flood protection, wildlife habitat

How do Wetlands Regulation and Water Rights Laws Intersect?

• Many wetlands were historically drained for farmland– The Great Black Swamp

• On the other hand, flood irrigation practices sometimes create wetlands, at least temporarily

• Groundwater use can lower water tables and drain wetlands

SWANCC v. U.S. Army Corps

• An old, abandoned sand and gravel pit had evolved into a forested area with seasonal and permanent ponds

• Corps claimed jurisdiction under migratory bird rule

• Court confirms Riverside Bayview Homes holding that §404 covers wetlands adjacent to navigable waters

• Majority rejects migratory bird rule– Why?

The Scope of §404 after SWANCC

• Could Congress adopt the migratory bird rule as an amendment to the CWA?

• Note Stevens dissent in SWANCC– Legislative history indicates that Congress intended that

federal jurisdiction under the CWA be given its “broadest possible constitutional interpretation.”

• Post-SWANCC decisions suggest that the Courts are giving SWANCC its “broadest possible” meaning

• Do SWANCC and New Mexico (both written by Rehnquist) suggest a similar philosophical approach?

“No Net Loss” of Wetlands• Half of all native wetlands in the United States have been

destroyed

• These wetlands provide important “ecosystem services”– Water filtration– Flood control– Wildlife habitat

• The economic losses because these services have been compromised is enormous. The replacement value of these services is equally high.

• How does “no net loss” work?– What problems arise at the individual project level?

Compensatory Mitigation and Wetlands Banking

• Shift from on-site to off-site mitigation

• Support for wetland mitigation banks– Restored or created wetlands can be banked

for future credit toward wetland destruction

• Should compensation be based upon wetland functions rather than acreage?– How do you measure wetlands functions?– Why is the banking system working so poorly?

The Meaning of “Navigability”• Navigability for purposes of title to the bed

• “Navigable in fact” test -- The Daniel Ball • Capable of being used in its ordinary condition as a

highway for commerce (need not be interstate commerce)

• Navigability for purposes of the navigation servitude• Includes tributaries of navigable waterways but not

waterways rendered navigable by improvements

• Navigability for commerce clause purposes• Like title test except reasonable improvements can be

made

• Navigability for public rights of access• State test depends on local law (A “pleasure boat” test?)

• Navigability for purposes of environmental regulation• Broadest possible constitutional interpretation?

The Navigation Servitude

• The government owes no compensation for the value of land associated with a “navigable” waterway– No compensation for loss of access

– No compensation for loss of flow

– No compensation for value as a port site

The Endangered Species Act1. Provides for listing species as “threatened” or

endangered”

2. Requires conservation of listed species (through affirmative federal agency action and a “recovery plan”)

3. Requires consultation and prohibits jeopardy to a listed species, or “adverse modification” of designated “critical habitat” by federal agency actions

– Where an agency finds jeopardy it must set forth “reasonable prudent alternatives” (RPAs) that would not cause jeopardy

4. Prohibits the taking of a listed species of wildlife (not plants) without a permit

Consider the Case Studies• Edwards Aquifer

– 8 unique aquatic species listed

• Middle Rio Grande– The silvery minnow

• Colorado River Basin– Four fish species and the southwestern willow flycatcher

• California/Bay Delta– Five fish species

• Pacific Northwest– Numerous species of salmon, steelhead, chum and bull

trout

Silvery Minnow

http://ifw2es.fws.gov/Documents/R2ES/FINAL_CH_Designation_Rio_Grande_Silvery_Minnow.pdf

68 Fed Reg. 8134 (2003)

•

California/Bay Delta

• Delta smelt, winter run Chinook salmon and three other species threatened by the operation of the federal Central Valley Project (CVP) and the State Water Project (SWP)

Pacific Northwest

• Salmon runs of the Columbia River and its tributaries– Each run supports a unique species– While the Northwest has a lot of water,

dams have blocked salmon migration, and pollution from urban runoff, farming and logging threatens stream quality

Tulare Lake Basin WSD v. U.S.• What is the nature of the water rights at issue in this case?

• The FWS set forth “reasonable and prudent alternatives” that limited the amount of water available to the Districts

• Consider the “takings” analysis– Was this a physical appropriation of water?

• Why does it matter?

• Does the contract limit the title?– Are you persuaded by the Court’s effort to distinguish

O’Neill?

• How does the public trust doctrine fit into the Court’s analysis? Could California impose limits to avoid the taking?

Q & D: Pages 846-848

• How does this analysis look under the Penn Central test?

• Should a taking be found in the situation where there is a “hybrid” drought – one caused by natural and regulatory conditions?

Interstate Allocation of Water

1. Judicial allocation– Equitable apportionment

2. Allocation by interstate compact

3. Congressional allocation

Which do you think is the preferable method? Why?

Equitable Apportionment• Kansas v. Colorado (1907)

– Court established the doctrine but refused to apportion the Arkansas River because Kansas failed to show serious harm

• Colorado v. Wyoming (1922)– Court apportioned Laramie River suggesting that it would essentially

follow priorities (since both Colorado and Wyoming used the PA system), but it actually protected certain out of priority uses in Colorado

• New Jersey v. New York (1931)– Court apportioned Delaware River with mass allocations and minimum

stream flows

• Nebraska v. Wyoming (1945)– Court apportioned North Platte River but refused to adhere to strict

priorities

• Colorado v. New Mexico– Reasonable conservation measures required but marginal New Mexico

irrigation district only need use economically feasible practices

Interstate Compacts

• Compact Clause: Art. 1, Sec. 10. cl. 3:– “No State shall, without the consent of Congress, …

enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State….”

• Advantages– Avoids dormant commerce clause problems– Promotes efforts to find common ground among States – As federal law a compact trumps inconsistent state law

• Cuyler v. Adams, 449 U.S. 433 (1981)

• Disadvantages– States are often reluctant to concede authority to a

Commission that they may not be able to control

Pecos River Compact

• Texas v. New Mexico– Headwaters are in New Mexico

– Texas upset that New Mexico is taking too much water

• Pecos River Compact– States agreed to provide water equivalent to that available

under “1947 condition.”

– Flows rarely met the 1947 baseline levels

• New Mexico claims that standard was mistaken

• Texas complained that it was not receiving water required by the Inflow-Outflow Manual

– Compact Commission consists of only two voting members – one from Texas and one from New Mexico

» The result was that disputes could never be resolved

Compacts• Politically difficult to structure dispute resolution

mechanism with two States– Neither State wants to give up control– The result may be gridlock

• Where compact or other apportionment of water applies, individuals within the States are bound by water limits– Hinderlider v. La Plata & Cherry Creek Ditch Co.

• Compacts rarely address groundwater– Should they nonetheless be construed to encompass

groundwater?– Draft Great Lakes Compact addresses both ground

and surface water

Delaware River Basin Compact• Good model for Great Lakes States but politically

difficult to achieve

• Includes Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania– Each State has one voting member and the federal

representative is a voting member

• Commission has broad powers to manage virtually all aspects of river management– Water quality; water allocation; hydro power generation;

recreational use; flood control; watershed protection– Operates under a comprehensive plan; actions not

approved unless consistent with plan

Federal-State Compacts

• Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin Compact (Florida, Georgia, Alabama and U.S.)

• Alabama-Coosa-Tallaposa River Basin Compact (Georgia, Alabama, and U.S.)

• These compacts provide for water allocation, as well as water quality protection and biodiversity conservation

Congressional Apportionment

• Advantages– Perhaps the most efficient way to allocate water– No dormant commerce clause issues– Direct protection of federal rights– Breaks impasse that may develop among States

• Disadvantages– Can be perceived as heavy-handed

• But in recent years Congress has been very protective of State’s rights

• Example of Water Quality Control Act Amendments of 1986 – Gives every Great Lakes state veto over out of basin diversions

– Interferes with State control over water

The Law of the River• Historical Flows

– 1896-1922: 16.9 MAF 1896-1990: 15.0 MAF

• 1922 Colorado River Compact – Upper basin must deliver 75 MAF to lower basin over ten years

(but they can’t withhold water not needed for municipal or agricultural uses). Arizona refused to ratify.

• Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928– Authorized Boulder (Hoover) Dam and the All-American Canal– Pre-approved lower basin compact allocation; Gila flows to AZ

• Mexican Treaty (1944)– 1.5 MAF (Under the Colorado River Compact, this amount is

supplied first from any surplus, and then by equal amounts from the upper and lower basins. Article III(c).

The Law of the River II• 1948 Upper Basin Compact

– Arizona: 50,000 AF; Colorado: 51.75%; New Mexico: 11.25%; Utah: 23.00%; Wyoming: 14.00%

• Colorado River Storage Project Act of 1956– Glen Canyon Dam (No Echo Park Dam)– Blue Mesa on Gunnison; Navajo on San Juan; Flaming Gorge on

Green; Central Utah Project

• 1965 Arizona v. California decision– Tributaries to Arizona; Congressional apportionment of river

pursuant to contracts with the Secretary of the Interior • Arizona 2.8 MAF; California 4.4 MAF; Nevada 0.3 MAF

• Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968– Central AZ Project approved; Grand Canyon dams rejected; 5

upper basin dams approved; coal fired power plant approved; ban on even studying water diversions from Pacific Northwest

Colorado River Issues

• Intra-basin transfers and water marketing– Promoted by the Interior Department with apparent

power to make allocation decisions under Arizona v. California decision

• In 2001, Nevada agreed to pay Arizona $170M to bank 1.2 MAF

• Mexican Treaty issues– Quality and quantity/Colorado River Delta

• Environmental problems– Endangered species– Salton Sea– Colorado River Delta

Q & D: Colorado River• Upper Basin is currently using only 4 MAF of its 7.5

MAF. – Can they sell their excess to a lower basin State? – To a private company or municipality in the lower basin? – To a private company in the Upper Basin that uses the

River to deliver to a customer in the lower basin?– Why do you think this has not yet been a big issue?

• If there had been no compact, how do you think the Court would have allocated the River?

• Should the Court simply recognize priorities across state boundaries?– What practical problems would arise?

Missouri River Basinhttp://infolink.cr.usgs.gov/Maps/basin-tribes.gif

Missouri River• Heavily developed at taxpayer expense

– Numerous dams provide irrigation, flood control, navigation improvements, and electric power generation

• No congressional apportionment as such, but heavy federal role effectively keeps river under federal control

• 27 Indian tribes in the Basin create significant uncertainty about the amount of non-Indian water available over the long term.

International Water Law• 214 multinational water basins

– 40% of the world’s population– 13 River basins are shared by five or more countries

• To what extent can interstate allocation principles be translated to the international arena?

• Harmon Doctrine of absolute sovereignty– To what extent will this hinder or help compromise?

• The Trail Smelter case– “No state has the right to use or permit the use of its

territory is such as a manner as to cause injury in or tow another territory … when the case is of serious consequence….”

– Principle 21, Stockholm Declaration; Principle 2: Rio

Helsinki Rules on the Use of Waters in International Rivers

• “Each basin State is entitled, within its territory, to a reasonable and equitable share in the beneficial uses of an international drainage basin.” (1966)

• Not adopted but influential in addressing conflicts

Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses

• General provision for equitable and reasonable utilization and participation– Based on enumerated factors

• Obligation not to cause significant harm, and to mitigate harm that has been caused – Trail Smelter concept

• Exchange of water data

• Joint protection of the ecology

• Only 12 (downstream?) countries have signed the convention. It requires 35 to take effect

Rio Grande River Basin

http://mrgbi.fws.gov/ Resources/Dams/

Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909• Applies to all boundary waters between U.S. and Canada

• Navigation in all navigable boundary waters to remain “free and open”

• Establishes the International Joint Commission (IJC)– Six commissioners – 3 from each country– Authority to review and approve uses, obstructions, and

diversions “affecting the natural level or flow of boundary waters on the other side of the line.” Art. III.

• Decisions by majority vote– Examines questions and issues reports on referrals from

either government

• Domestic uses preferred over navigation, which are preferred over power and irrigation– Each party reserves exclusive rights to divert water

Nile River Basinhttp://encarta.msn.com/media_461519267_761558310_-1_1/Nile_River.html

Problems• Water scarcity

– Annual renewable freshwater is less than 1000 cubic meters/year = 11,772 cubic feet/year = 32.25 cubic feet per day = 241 gallons per day

• Water quality

• Too much agriculture– 80% of water goes to agriculture

• Egypt – the biggest user and the most dependent on the Nile – is the farthest downstream

• 1959 bilateral treaty between Sudan and Egypt tries to allocate the entire River to these two countries