The Amerindians and Inuit of Québec€¦ · The Inuit The Inuit are of different race and culture...

Transcript of The Amerindians and Inuit of Québec€¦ · The Inuit The Inuit are of different race and culture...

The Amerindians and Inuit of QuébecThe Amerindians and Inuit of Québec

Eleven Contemporary NationsEleven Contemporary Nations

Publication: Secrétariat aux affaires autochtonesGraphics: Indiana Marketing

This brochure is also available in French under the titleLes Amérindiens et les Inuits du Québec, Onze nations contemporaines

Legal deposit - Bibliothèque nationale du Québec, 2001 National Library of Canada, 2001

ISBN: 2-550-38481-4© Gouvernement du Québec, 2001

INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

A PROFILE OF TODAY’S ABORIGINAL PEOPLE . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

Québec’s role . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

The Secrétariat aux affaires autochtones . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

Who are aboriginal people? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

Status Indians . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

Non-status Indians . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

The Inuit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

The signatories of the agreements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Population . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Where do aboriginal people live? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

COMMUNITY LIFE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

Health and social services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

Hunting, fishing and trapping . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13

The legal system . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13

Public security . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

ABORIGINAL CULTURE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15

Language . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15

Artistic expression . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15

Communications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

ECONOMY AND EMPLOYMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17

POLITICAL ORGANIZATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .19

ABORIGINAL CLAIMS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

Comprehensive land claims . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

Specific claims . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

Self-government . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

Other claims . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

MAJOR MILESTONES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23

Significant steps . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .29

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

This booklet examines the current conditionof Québec’s aboriginal people, the progressmade in their relations with other Quebecersand the initiatives taken by the Québec gov-ernment regarding aboriginal affairs. It pro-vides important information on and raisesawareness of aboriginal issues.

The booklet begins with an overview of theQuébec government’s role in aboriginalaffairs. It then provides general informationon the demography, social conditions, culture,economy, and political structure of Québec’saboriginal people. The booklet concludes witha description of the stages that have markedrelations between the government and abo-riginal people over the last 40 years.

Of course, this document does not claim toprovide a complete picture of the current con-dition of the Amerindians and the Inuit, or toexamine all the differences between the vari-ous aboriginal nations. More modestly, thisbooklet hopes to provide some perspective onthe present-day realities of Québec’s aborigi-nal people.

3

INTRODUCTION

Who are Québec’s aboriginal people? Wheredo they live and how many are there? Whatsets them apart culturally, economically andsocially? What is their political life based on?What are the roles of the Canadian andQuébec governments in aboriginal affairs?These questions have to be answered toobtain a realistic picture of aboriginal people.

“Aboriginal” is a generic term used to refer tothe original nations of a country. In Québec,Amerindians, people of Amerindian ancestry,and Inuit are all considered to be aboriginalpeople.

It is important to distinguish Quebecers whowere born here, but whose ancestors(European or otherwise) immigrated begin-ning in the 17th century, from the descen-dants of the first nations to arrive in Americaseveral thousand years earlier.

Québec’s roleIt was not so long ago that programs forAmerindians were administered entirely bythe federal Department of Indian andNorthern Affairs. However, band councilsgradually began to take over responsibility forall sectors of activity in their community.Nonetheless, the ties formed between thefederal government and Québec’sAmerindians remain significant. Under the

Indian Act, the federal government has pri-mary responsibility for Amerindians.

The Québec government has had a role toplay among the Inuit of Québec in particularand with the entire Cree and Naskapi nationssince the signing of the James Bay andNorthern Québec Agreement in 1975 and theNortheastern Québec Agreement in 1978. Italso works increasingly with all the aboriginalnations in various sectors of activity.

This role has intensified since the announce-ment, in the fall of 1998, of the government’sguidelines for aboriginal affairs. These guide-lines are given in a paper entitled PartnershipDevelopment Achievements and cover theeleven aboriginal nations in Québec. TheQuébec government intends to meet the chal-lenges of improving relations between aborig-inal people and Quebecers as a whole, reach-ing development agreements, improving self-government and financial self-sufficiency ofaboriginal communities, as well as their socialand economic conditions. Since these guide-lines were released in 1998, Québec and abo-

riginal people have reached a large number ofagreements.

Québec continues to deal with aboriginalpeople according to the 15 principles adoptedby the government in 1983 and the resolutionpassed by the National Assembly in 1985, rec-ognizing aboriginal rights.

The Secrétariat aux affaires autochtones

The mission of the Secrétariat aux affairesautochtones, which is part of the ministère duConseil exécutif, is to promote harmoniousrelations with aboriginal people and fostertheir development.

While the federal government has centralizedits dealings with aboriginal people in theDepartment of Indian and Northern AffairsCanada, Québec has taken a differentapproach. Each Québec government depart-ment and organization exercises its authorityin regard to aboriginal people in the same wayit does in regard to the rest of the population.Most have an aboriginal affairs coordinator.

5

A PROFILE OF TODAY’SABORIGINAL PEOPLE

However, the Secrétariat aux affairesautochtones coordinates government activi-ties as a whole.

The Act to amend the Act respecting theministère du Conseil exécutif, which becameeffective in January 2000, broadened themandate of the Minister for Native Affairs,who is responsible for the Secrétariat. The lat-ter, working with government departmentsand organizations concerned, also conductscomprehensive negotiations with aboriginalpeoples. In addition, it implements all theagreements between the Québec governmentand aboriginal peoples.

Lastly, the Secrétariat supplies appropriateinformation to aboriginal people and toQuebecers in general.

Who are aboriginal people?According to the Indian Act, “an Indian is aperson who is registered as an Indian in theIndian Register of the Department of Indianand Northern Affairs (DINA) or who is entitledto be”. This definition is the basis for distin-guishing between status Indians, non-statusIndians and Inuit.

Status Indians

A person is recognized as a status Indian if hisor her name is listed in DINA’s Indian Register.The everyday life of status Indians is affectedby factors related to their status. Although theIndian Act confers certain rights, it also impos-es obligations that can be constraining. Agroup of status Indians for whom land hasbeen reserved and whose funds are held bythe Crown forms an Indian band.

Income earned by Indians on the reserve isgenerally tax-exempt, and goods purchasedon the reserve are non-taxable. However, asproperty on the reserve is non-seizable, exceptby another aboriginal person, it cannot beused as security for a loan. This situation canpresent significant problems, for instance,when it is necessary to borrow money tofinance a business.

Income earned by status Indians outside ofthe reserve is usually subject to the same taxesas that of other Quebecers. Status Indiansmust also pay the same taxes as otherQuebecers on all goods purchased outside ofthe reserve that are not delivered to thereserve. However, they are exempt from pay-ing municipal property taxes and school taxeson trapping camps located on beaverreserves.

Non-status Indians

For various reasons, even though they haveAmerindian ancestry, non-status Indians arenot listed in the Indian Register. In most cases,they are the descendants of women who losttheir status as Indians because they marriednon-Indians. In Québec, non-status Indiansare not referred to as Métis.

Since 1985, when Bill C-31 was passed, theIndian Act enables an Indian woman to recov-er her status if she lost it by marrying a non-Indian. This amendment allows her children toobtain their status as Indians as well.

The Inuit

The Inuit are of different race and culture thanthe Amerindians. They are not subject to theIndian Act. The Inuit are subject to the sametax system as other Quebecers, and they donot have any special exemptions.

6

The signatories of the agreements

After the signing of the James Bay andNorthern Québec Agreement with the Creesand the Inuit in 1975, and the NortheasternQuébec Agreement with the Naskapis in1978, the Canadian government passed theCree-Naskapi (of Québec) Act. For these twonations, this Act replaces the Indian Act,giving them a different legal framework. TheInuit, however, chose to be governed byQuébec, rather than be subject to a federalstatute.

Population

The total population of the 10 Amerindiannations and the Inuit nation was approximate-ly 77 850 in 2000, which represents 1% ofthe total population of Québec.

A few demographic features:

- The population of the nations ranges fromabout 700 in the case of the Malecitenation to over 15 500 in the case of theMohawk nation.

- The population of aboriginal communitiesvaries considerably from 150 to over 9 000inhabitants.

- 25% of the communities have a populationof less than 500 and 55% have fewer than1 000 inhabitants.

- 50% of the aboriginal people in Québec- and 39 of the 55 communities - live inthree regions: Nord-du-Québec, Abitibi-Témiscamingue and Côte-Nord.

- 81% of the Abenakis, 58% of the Hurons-Wendat and almost all the Malecites live offreserve.

- The Inuit population lives almost exclusivelyin 14 northern villages while 66% ofAmerindians live on reserves.

- Inuit communities are generally small, withpopulations between 150 and 1 625.

- 50% of status Indians are under 30 years ofage, compared with 39.5% for Canadiansas a whole. Among status Indians, 8% areover 65 years of age, compared to 12.5%for Canada’s population as a whole.

- Among the Inuit, 66.5% are under 30 and3.4% are older than 65.

- The aboriginal population grew by close to9 000 people as a result of changes madeto the Indian Act in 1985.

- 10% of Canada’s Amerindian populationresides in Québec, 23% in Ontario and16% in British Columbia.

7

8

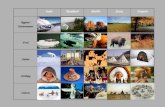

ABORIGINAL POPULATION IN QUÉBEC

Nation Communities Residents Non- Totalresidents

ABENAKIS Odanak 308 1 466 1 774Wôlinak 64 147 211

372 1 613 1 985

ALGONQUINS Hunter’s Point 12 225 237Kebaowek 234 390 624Kitcisakik 298 47 345Kitigan Zibi 1 436 1 001 2 437Lac-Rapide 447 129 576 Lac-Simon 1 104 233 1 337Pikogan 527 243 770 Timiskaming 536 975 1 511Winneway 335 299 634

4 929 3 542 8 471

ATTIKAMEKS Manawan 1 685 246 1 931Obedjiwan 1 755 295 2 050 Wemotaci 1 052 295 1 347

4 492 836 5 328

CREES Chisasibi 3 250 49 3 299Eastmain 564 14 578Mistissini 2 687 189 2 876Nemiscau 566 33 599 Oujé-Bougoumou 569 86 655Waskaganish 1 704 340 2 044Waswanipi 1 210 346 1 556Wemindji 1 098 78 1 176Whapmagoostui 740 7 747

12 388 1 142 13 530

HURONS-WENDAT Wendake 1 220 1 661 2 881

INNU(MONTAGNAIS) Betsiamites 2 521 626 3 147

Essipit 182 200 382 La Romaine 861 52 913Mashteuiatsh 1 960 2 595 4 555Matimekosh–Lac-John 700 71 771Mingan 449 14 463Natashquan 759 60 819Pakuashipi 257 2 259Uashat-Maliotenam 2 600 583 3 183

10 289 4 203 14 492

MALECITES Cacouna and Whitworth 2 681 683

MICMACS Gaspé 0 474 474Gesgapegiag 508 598 1 106Listuguj 1 911 1 115 3 026

2 419 2 187 4 606

Nation Communities Residents Non- Totalresidents

MOHAWKS Akwesasne(Québec section only) 4 658 69 4 727 Kahnawake 7 140 1 748 8 888Kanesatake 1 321 622 1 943

13 119 2 439 15 558

NASKAPIS Kawawachikamach 734 53 787

STATUS INDIANSNOT ASSOCIATED WITH A NATION 1 118 119

TOTAL – AMERINDIANPOPULATION 49 965 18 475 68 440

INUIT Akulivik 470 4 474Aupaluk 152 1 153Chisasibi (Inuit part) 96 13 109Inukjuak 1 187 60 1 247Ivujivik 273 6 279Kangiqsualujjuaq 686 11 697Kangiqsujuaq 513 24 537Kangirsuk 427 27 454Kuujjuaq 1 516 109 1 625Kuujjuarapik 478 88 566Puvirnituq 1 252 69 1 321Quaqtaq 307 19 326 Salluit 971 64 1 035Tasiujaq 221 0 221Umiujaq 328 25 353

TOTAL – INUITPOPULATION 8 877 520 9 397

GRAND TOTAL 58 842 18 995 77 837

Sources: Indian Register, Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, December 31,2000 and Registers of Cree, Inuit and Naskapi Beneficiaries under the James Bayand Northern Québec Agreement and the Northeastern Québec Agreement, min-istère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec, April 5, 2001.

9

Where do aboriginal people live?The Amerindians of Québec live on reserves,settlements or lands governed by the agree-ments. However, they do not all live in com-munities, even if they are registered as mem-bers of a band. In Québec, almost 50 000Amerindians live on reserves, settlements orlands governed by the agreements, whereasalmost 18 500 live elsewhere. Most of the9 400 Inuit live in northern villages along theshores of Hudson Bay and Strait, and UngavaBay.

Reserves are tracts of lands that have been setaside for the use and benefit of Amerindians;settlements are lands inhabited by Indianbands, but never officially designated for theiruse. The federal government administers theterritories constituted by the reserves; howev-er, Inuit lands are subject to a distinct landregime entirely under Québec jurisdiction.

The northern agreements grant the Crees,Inuit and Naskapis specific rights over vast ter-ritories classified by category in order to facili-tate their administration and to establish userrights. Category I lands are designated exclu-sively for aboriginal use; categories II and IIIare public lands, on which aboriginal peopleenjoy certain rights.

In Québec, reserve lands cover a total area of14 786.5 km2. Category I lands under theagreements represent 95% of this area, andreserves and settlements, a mere 5%, eventhough they are home to 70% of aboriginalpeople living on reserved land.

NATION

Not governed by the agreements

Abenakis

Algonquins

Attikameks

Hurons-Wendat

Innu (Montagnais)

Malecites

Micmacs

Mohawks

Sub-total

AREA (km2)

6.8

208.0

49.8

1.1

295.1

1.7

41.4

142.5

746.4

THE AREA OF THE LANDS RESERVED FOR ABORIGINAL PEOPLE

Governed by the agreements

Crees

Inuit

Naskapis

Sub-total

GRAND TOTAL

5 551.7

8 162.1

326.3

14 040.1

14 786.5

Source: Ministère des Ressources naturelles, Localization of the aboriginal nations in Québec, Land Transactions,1998.* Decimals have been rounded to one place for the purposes of this publication.

The arrival of the Europeans on this continentunleashed a social upheaval among aboriginalpeople. Since 1940, the value systems and tra-ditional ways of life of Amerindians and Inuithave undergone rapid and far-reachingchanges.

Barely 60 years ago, the Inuit and a largenumber of Amerindians led nomadic lives. TheInuit roamed from one camp to another, livingin igloos and makeshift shelters while theyhunted fish and game to ensure their liveli-hood. The Amerindians would congregate atcertain specific places in the summer and dis-perse in groups of two or three families overhundreds of kilometres of forest as soon as fallcame. Their contacts with the other inhabi-tants of Québec were few and far between.

Nowadays, most aboriginal people spend theentire year in villages that have basic infra-structures and offer community services in theeducation and health and social services sec-tors.

Health and social servicesThe health of aboriginal people in Québec hasimproved noticeably in recent decades,although there are still disparities with the restof the people of Québec. Increased lifeexpectancy and lowered rates of infectiousdiseases and infant mortality are indications ofbetter physical health, but such problems asdiabetes, infectious diseases, injuries andmental distress continue to cause concern.

Of the social ills encountered among aborigi-nal people, alcohol and drug abuse, familyviolence and crime constitute major chal-lenges for many communities.

Aboriginal people are covered by the samelegislation governing health and social ser-vices as other Quebecers. The universalhospital and medical insurance plans are thebasis of health care both for them and fornon-aboriginal Quebecers.

In addition, the federal government offerspreventive services either directly or throughthe band council to all native communities,except those belonging to nations that havesigned agreements. The latter, that is, theCrees, the Inuit and the Naskapis, receive therange of services offered by the Québec gov-ernment through the aboriginal institutionscreated under the agreements. The Creeshave a regional health and social servicesboard that provides services through theChisasibi hospital and dispensaries in eachcommunity, which offer much the same ser-vices as Québec’s CLSCs (local communityservice centres). The Inuit have a regionalboard responsible for organizing the servicesoffered by two hospitals, one for the HudsonBay region and another for the Ungava Bayregion, again supported by community dis-pensaries in each Inuit village.

Finally, it should be emphasized that healthservices not insured under the Québec plans,such as dental care, optometry and prosthe-ses, are provided free of charge by the feder-al government to status Indians not governedby the agreements. The Québec governmentprovides most of these services free of chargeto the Inuit, the Crees and the Naskapis.

Under a 1984 special agreement with theQuébec government, the Mohawk people ofKahnawake have complete authority over the

administration and operation of the Katerihospital. The operating costs are paid byQuébec.

Most social services are provided by aboriginalorganizations, working in conjunction withthe Québec network for certain services relat-ed to the application of the Youth ProtectionAct and the Young Offenders Act. The nationsgoverned by the agreements have their ownchild and youth protection centres and reha-bilitation facilities for young people withadjustment problems. A few aboriginal com-munities prefer to go through Québec institu-tions to obtain the entire range of social ser-vices on their territory. In this case, the institu-tions hire native personnel in order to adapttheir services to aboriginal culture and com-munities.

Some aboriginal organizations play a domi-nant role in improving the social conditions ofaboriginal people. The Québec NativeWomen’s Association (QNWA) is very active inpromoting non-violence. The QNWA, whosehead office is in Montréal, carries out suchactivities as information campaigns, sympo-siums and community initiatives.

11

COMMUNITY LIFE

The Assembly of First Nations of Québec andLabrador (AFNQL), the Québec governmentand the federal government cooperated insetting up the First Nations of Québec andLabrador Health and Social ServicesCommission. In 1997, this body conducted awide-ranging medical survey of aboriginalpeople in Québec. The survey was funded byHealth Canada and was part of a Canada-wide initiative leading to report that wastabled in January 1999. The report containsinformation on many aspects of the physicaland mental health of aboriginal people inQuébec, and their way of life.

EducationThe education of aboriginal children inQuébec comes under the jurisdiction of thefederal government, in keeping with theIndian Act, with the exception of Cree, Inuitand Naskapi children, whose nations havesigned special agreements with the Québecand federal governments.

Aboriginal children at the primary level usual-ly attend their community school. Most ofthese schools also offer schooling at the sec-ondary level. Where this is not available, thechildren are enrolled in schools in the Québecsystem.

Although a number of school programs areadapted to aboriginal culture and language,Québec’s educational program is generallyapplied in aboriginal schools. Once run by theDepartment of Indian and Northern Affairs,these schools are now administered by bandcouncils and funded by the federal govern-ment.

The movement by aboriginal peoples to takecharge of education began in 1972, whenthe National Indian Brotherhood (Canada)published a statement of principle entitled

Indian Control of Indian Education. Amongother things, this declaration called for anoverhaul of the type of instruction affordedAmerindians and the introduction of a systemof education that better reflected aboriginalneeds and philosophies. The Brotherhoodasked that band councils be partially or total-ly responsible for the teaching given on thereserves, the long-term objective being com-plete autonomy, along the lines of a provincialschool board.

Accordingly, in 1978, the first communitydecided to take over education in its schools.This initiative, supported by the Departmentof Indian and Northern Affairs, promptedother communities to follow suit. Today, allcommunities but one are entirely responsiblefor teaching and administration in theirschools, and for making the necessary agree-ments with school boards.

At the post-secondary level, aboriginal stu-dents attend schools in the Québec network,and the costs of their education are paid by

Québec. The CEGEPs of Sept-Îles, Joliette,Chicoutimi, Outaouais, Baie-Comeau, John-Abbott and Marie-Victorin, as well as the uni-versities of Québec in Chicoutimi and inRouyn-Noranda and Concordia and McGilluniversities, in Montréal, have set up struc-tures and programs to accommodate theneeds of aboriginal people.

Although they are eligible for the Québecloans and scholarships program, aboriginalstudents at the college or university level oftenapply for individual financial assistance fromthe federal government to pay for tuition,transportation and accommodation.

In accordance with the James Bay andNorthern Québec Agreement, school boardshave been set up for the Crees and the Inuit.The Cree School Board and the Kativik SchoolBoard are responsible for, among other things,primary and secondary education as well ascontinuing education. They can also reachagreements concerning college and universityeducation.

12

As regards the Naskapi people, theNortheastern Québec Agreement provided forthe creation of an education committeeattached to an existing school board toadminister the school at Kawawachikamach.The Naskapis chose the Central QuébecSchool Board, which has its head office inQuébec City. Primary and secondary educa-tion is provided at the Naskapi school.

Funding for education in Cree, Inuit andNaskapi villages is shared by the federal andprovincial governments, in accordance withthe two agreements.

Enormous progress has been made in the levelof schooling of young aboriginal people overthe past three decades. However, the gap isstill too wide between the number of aborigi-nal people and the number of otherQuebecers attending secondary schools, col-leges and universities, for instance.

Hunting, fishing and trappingQuébec’s aboriginal nations do most of theirhunting, fishing and trapping on public landsin Québec. These activities are usually gov-erned by agreements, acts and policies underthe responsibility of the federal and provincialgovernments.

Hunting of migratory birds and fishing comeunder federal jurisdiction. Ottawa has, amongother things, adopted the AboriginalCommunal Fishing Licences Regulations andan interim policy on the application of theCanada Wildlife Act respecting off-seasonhunting and egg-gathering by aboriginal peo-ple. These measures enable the latter to carryon their traditional hunting and fishing activi-ties.

The Québec government established severalbeaver reserves beginning in 1928. Today,these reserves total 1 250 000 km2, of which

over 375 000 km2 are located outside thelands governed by the James Bay andNorthern Québec Agreement. On these terri-tories, with the exception of the Saguenayreserve, aboriginal people have exclusiverights for hunting and trapping fur-bearing

animals. Furthermore, aboriginal persons whotrap on beaver reserves and hold a licenceissued free of charge by the Minister responsi-ble for Wildlife and Parks can hunt and fish forsubsistence purposes throughout the year.

The James Bay and Northern QuébecAgreement, the Northeastern QuébecAgreement and the legislation to which theygive rise allow the Crees, the Inuit and theNaskapis to hunt, fish and trap under a differ-ent regime than the one governing the rest ofQuébec. Moreover, assistance programs havebeen set up to promote the preservation anddevelopment of their hunting and trappingactivities.

Hunting, fishing and trapping constitute aprime element in the negotiations being car-ried on with several aboriginal communitiesbecause these activities are closely linked tocultural survival and development, economic

expansion and cooperation in the manage-ment of wildlife resources.

The legal systemThe Québec court network serves all the abo-riginal communities. Generally speaking, thecomposition, jurisdiction and operation of thecourts are the same everywhere in Québec.

However, two regions are served by itinerantcourts that travel to isolated aboriginal com-munities. One serves the Crees and the Inuit;the other serves the Naskapis and the Innu inthe Schefferville and Basse-Côte-Nord regions.Hearings, when necessary, are translated intothe vernacular. Civil, criminal and penal cases,as well as those under the jurisdiction of theYouth Division, are heard.

There are currently four courthouses in abo-riginal communities, in Chisasibi, Kuujjua-rapik, Puvirnituk and Kuujjuaq. In the lattercommunity, a Québec public prosecutor, alegal aid lawyer and a clerk are available on apermanent basis to serve the people of thecommunity and neighbouring villages.

13

Because of the interest taken by aboriginalcommunities in playing a more active role insocial control at the community level, the min-istère de la Justice has participated, in recentyears, in studying and developing mechanismsto assist aboriginal communities to graduallytake on more responsibilities regarding theadministration of justice. It wants to extendpartnerships with various aboriginal commu-nities interested in playing an active and com-plementary role in this field.

The proposed mechanisms make use of mod-els for the appointment of aboriginal justicesof the peace or the implementation ofapproaches fostering public participation inconflict resolution. In the latter case, commit-tees could be formed of citizens responsible,in particular, for advising judges or justices ofthe peace, regarding sentencing, proposingmeasures for young or adult offenders tocompensate the victim or community as partof a duly authorized program, or mediating incertain disputes.

Lastly, since 1979, the Native Para-judicialServices of Québec has been administered bya non-profit corporation whose board ofdirectors includes representatives from all abo-riginal communities. The organization has 18paralegal advisers and is active in both urbanand isolated communities. The chief role ofthe advisers is to inform aboriginal people ofhow the legal system works and help accusedaboriginal people to understand the natureand consequences of the accusations, thedecisions of the court, and their rights andresponsibilities under various statutes. Theyalso work to make participants in the criminaljustice system aware of the social and culturalsituation of aboriginal people. Lastly, they pro-vide liaison between stakeholders andaccused aboriginal people in the various stepsof the legal process.

Public securityAboriginal communities are empowered toregulate a number of areas affecting publicsecurity, such as fire protection and highwaytraffic. The rapid growth of the aboriginalpopulation has led to a demand for more pub-lic security services in the communities.Consequently, prevention and a communityapproach are matters of on-going concern.

Policing in aboriginal communities must besensitive to the diversity of the communitiesand nations. Thus, for a number of yearsalready, the Québec ministère de la Sécuritépublique and the Department of the SolicitorGeneral of Canada have each administered aprogram designed to set up police services inaboriginal communities.

Fifty aboriginal communities in Québec pro-vide police services and most of them haveconcluded agreements to that effect. Whilethey administer these services themselves, theSûreté du Québec or other organizations mustat times provide police officers with supportand back-up.

Québec is the only government in Canada tohave amended its Police Act to allow for thecreation of aboriginal police forces, givingAboriginal police officers the same status asany other peace officer in Québec. To date,eleven communities have such police forces,namely Kitigan Zibi, Pikogan, Wendake,Betsiamites, Essipit, Mashteuiatsh, Uashat-Maliotenam, Listuguj, Akwesasne, Kahna-wake and Kanesatake. In the other communi-ties, special aboriginal constables appointedand sworn in under the Police Act providepolice services. Aboriginal police officers aretrained at the École nationale de police duQuébec.

Aboriginal police officers in Québec do nothave an easy job. They must often deal withthe effects of a high unemployment rate inaboriginal communities, a high school drop-out rate, and problems stemming from alco-hol and drug abuse. Family violence and sui-cide are also matters of constant concern.

In spite of such difficulties, in 1999-2000,Québec had the lowest aboriginal incarcera-tion rate in Canada, i.e. 1.3%, whereas abo-riginal people make up 1% of Québec’s pop-ulation. Over the same period, the number ofaboriginal offenders admitted to detentioncentres declined significantly, while correc-tional measures in open custody rose (sus-pended sentence, probation, communitywork, etc.).

14

Québec’s 11 aboriginal nations all have a vari-ety of culturally distinct features. In this sense,we must speak, not of one, but of severalaboriginal cultures. Aboriginal people are nowreclaiming their ancestral cultures after hav-ing, in some cases, strayed from them.

Cultural expressions are imbued with tradi-tional values that are still present, to varyingdegrees, in aboriginal nations. The naturalenvironment, central to the spirituality andphilosophy of traditional cultures, is compre-hensively dealt with. Accordingly, nature isseen as Mother Earth while humans are butone component, like wildlife, plant life, etc.

Until quite recently, the improvement of socialand economic conditions was at the centre ofaboriginal demands in negotiations with gov-ernments. In recent years, cultural develop-ment has also become a priority.

There has been a return to aboriginal spiritu-ality and traditional modes of thinking as away of restructuring social and cultural pat-terns. Many aboriginal people are now con-vinced of the need to return to their culturalroots and values to ensure their survival anddevelopment as a distinct people.

The cultural heritage of Amerindians and Inuitis a blend of oral tradition, legend, folk medi-cine, songs and places reminiscent of ances-tral deeds, sacred rites, and customs handeddown by successive generations. In thisrespect, the elders embody a truly living her-itage.

A much less well-known tradition, but onewhich has nevertheless been kept alive byaboriginal people, concerns the manufactureof utilitarian objects like moccasins, mittens,snowshoes, rifle sheaths, crooked knives, ice-picks and wooden shovels.

LanguageAmerindians and Inuit frequently expressthemselves in their own language, anywhereand in any circumstance. Of Québec’s 11 abo-riginal nations, eight have preserved theirmother tongue. On the other hand, the pro-portion of people who are still able to speakthat language depends on the community.One of the factors influencing the fate of abo-riginal languages seems to be the remotenessof the community from large urban centres.Whereas the mother tongue is spoken byalmost everyone in isolated communities, it isrestricted to the elders in communities closerto such centres; in some cases, it has disap-peared altogether.

The movement among aboriginal peoples topromote their cultural identity has given theirlanguages a new lease on life. Several aborig-inal nations have created structured culturalorganizations with mandates to preserve andpromote their language.

Artistic expressionThe artistic world of aboriginal people is burst-ing with energy. This is clear from the scopeand quality of native achievements in thefields of sculpture, art, music, theatre and cin-ema.

Many aboriginal artists have earned an inter-national reputation and perform in Québec aswell as elsewhere in North America andEurope.

15

ABORIGINAL CULTURE

The arts and crafts industry, in which manywomen work, has undergone considerablechange in recent years. It has become a thriv-ing economic activity, complementing olderartistic products like Inuit soapstone sculp-tures, which are now sold all over the world.

Some aboriginal nations have set up their owncultural institution, such as the Inuit AvataqCultural Institute and the Institut culturel etéducatif montagnais (ICEM).

A number of aboriginal communities, such asMashteuiatsh, Listuguj, Odanak, Wendake,Puvirnituq and Uashat-Maliotenam, boasttheir own museum.

CommunicationsOral tradition has always been the preferredvehicle of aboriginal culture. This doubtlessexplains why aboriginal people have opted forradio over print media and television.

Almost all aboriginal groups have their owncommunity radio station. For over 20 years,Québec’s ministère de la Culture et desCommunications has fostered the develop-ment of these stations, in particular through aspecial support program. By broadcasting inthe community’s indigenous language, com-munity radio stations contribute significantlyto the survival of aboriginal languages.

There are three aboriginal communicationnetworks in Québec: the Société de commu-nication atikamekw-montagnaise (SOCAM),the Inuit Radio and Television corporation,Taqramiut Nipingat, and the James Bay CreeCommunications Society.

There are a number of aboriginal print publi-cations in Québec. The largest are the InuitMakivik Magazine and four newspapers,namely the Innu Innuvelle, The Nation among

the Crees, and the Mohawk Eastern Door andIndian Time. Two magazines about aboriginalpeople are also published in Québec.Recherches amérindiennes au Québec is pub-lished in Montréal by a group of anthropolo-gists, while Rencontre is produced by theSecrétariat aux affaires autochtones. Lastly,the periodical Études Inuit/Inuit Studies is pub-lished twice a year by the Inuksiutiit KatimajiitAssociation, in collaboration with UniversitéLaval’s Groupe d’études inuit et circumpolaires(GÉTIC).

In addition, many aboriginal organizationshave websites promoting culture, the econo-my, tourism as well as more political issues.

16

Several factors and constraints influence theeconomic development of Québec’s aboriginalcommunities. The majority of these communi-ties are small and far from market centres;almost 30% are not linked to the highwaysystem. In addition, since nearly 70% of theAmerindians on reserves do not hold second-ary school diplomas, their access to vocation-al training is limited. Lack of skilled labour anddifficulties obtaining financing are also factorsthat make it difficult to create stable well-pay-ing jobs.

It should be pointed out that the communitiesclosest to major urban centres have success-fully developed their manufacturing and com-mercial sectors. For example, the WendakeHuron-Wendat community, the KahnawakeMohawk community, and the Mashteuiatsh,Essipit and Uashat-Maliotenam Innu commu-nities have spawned many businesses.Aboriginal people are emerging increasinglyas leading economic partners in their regionsand in Québec as a whole.

The First People’s Business Association, for-med in 1994, consists of aboriginal and non-aboriginal business people. Its mission is topromote and develop entrepreneurshipamong aboriginal people. Despite significanteffort, aboriginal people are generally disad-vantaged economically in comparison withthe rest of Québec. The employment rate issubstantially lower among aboriginal peoplethan in the population as a whole, althoughthe rate among Quebecers living in the sameoutlying regions is also lower than the provin-

cial average. Similarly, the average wage ofAmerindians living on reserves is little morethan half of what other Quebecers earn.

However, through the agreements, the Crees,Inuit and Naskapis have received substantialfinancial compensation, which has served toboost economic development. They have thusbecome solidly established in such sectors asair transport, construction, forestry and outfit-ting. Ready examples of their enterprise areAir Creebec, Cree Construction, Air Inuit andthe Tuktu outfitting operation.

Furthermore, growth in aboriginal tourism hasbeen remarkable in recent years. Many com-munities now boast lodging infrastructuresand activities that showcase their way of lifeand culture.

Traditional activities like hunting, fishing andtrapping are still carried on by many aboriginalpeople, sometimes to supplement a family’sincome but less and less as a major economicactivity. They are part of a lifestyle but are no

longer the sole basis of the economy andemployment. There are many reasons for this,in particular the decline of the fur market, thegrowth of the aboriginal population andbroadening interests among the young.Nonetheless, one area related to wildlife man-agement, namely the outfitting sector, is cur-rently thriving in several communities andboosting local job creation.

Under the agreements, the Cree, the Inuit andthe Naskapi nations benefit from a specialprogram set up to provide support for tradi-tional hunting, fishing and trapping activities.

17

ECONOMY AND EMPLOYMENT

Until quite recently, notions like political partyand level of government were absent fromtraditional Amerindian and Inuit politicalorganization. Decisions were made by thecommunity. Today, local authority belongs tothe band council in Amerindian communitiesand to the municipal corporation among theInuit.

The Indian Act allows communities either toelect band council members by universal suf-frage or to choose them according toAmerindian custom. Band councils, which aremade up of the chief and his councillors, playa political and administrative role. They cancreate committees and organizations to over-see the various aspects of community life. Theband council is the key community represen-tative in dealings with government. Its powersare broader than those of municipal councilsin Québec. It is responsible for the delivery ofall community services, including education,health, etc.

The northern village councils in Inuit commu-nities are composed of a mayor and council-lors elected by universal suffrage every twoyears. The northern village municipalityassumes responsibilities normally delegated tomunicipalities, such as the administration ofmunicipal services and public services; theycan also regulate in these areas.

Some nations have set up organizations todefend and promote their interests. Some ofthe major aboriginal organizations in Québecare the Conseil de la nation atikamekw, the

Innu Conseil tribal Mamuitun and MamitInnuat, Makivik Corporation among the Inuit,the Grand Council of the Crees (Québec), theAlgonquin Anishnabeg Nation Tribal Counciland the Algonquin Nation Programs andServices Secretariat , the Abenaki Grand con-seil de la nation Waban-Aki, the Conseil de lanation huronne-wendat, the Conseil de lanation malécite de Viger and the MicmacMi’gmawei Mawiomi Secretariat.

At the pan-Canadian level, the Assembly ofFirst Nations, which represents severalnations, has branches in every province. TheAssembly of First Nations of Québec andLabrador is the Québec branch.

19

POLITICAL ORGANIZATION

While we often hear about the claims madeby aboriginal peoples, are we truly aware ofthe nature of and reasons behind theseclaims? Although they touch on variouspoints, they almost always seek to achievethree goals: greater autonomy, more land andthe preservation of aboriginal identity and cul-ture.

The federal policy on aboriginal claims distin-guishes between comprehensive land claimsand specific claims. There are also other claimsthat do not enter into either of these cate-gories, as will be seen further on.

Comprehensive land claimsTreaties were signed between the BritishCrown and the Amerindians of Canada longbefore Confederation. After the CanadianConfederation in 1867, the federal govern-ment continued this policy. It signed a seriesof treaties with aboriginal peoples in severalprovinces. These treaties dealt with land, edu-cation, pensions, hunting, etc.

As of 1920, jurisprudence recognized the exis-tence of property rights for aboriginal people.In 1973, in the Calder case, the SupremeCourt of Canada confirmed the existence ofthese rights. However, the courts did notdefine them.

The federal policy on aboriginal land claimswas adopted in 1973. According to this poli-cy, comprehensive land claims are those based

on traditional use and occupancy of the land.They generally concern a group of aboriginalbands or communities in a given region, andinvolve demands for the recognition of gener-al rights, such as property rights, hunting,fishing and trapping rights, and other eco-nomic and social benefits. It is a question ofreplacing undefined property rights with pre-cise rights defined in agreements.

Acting in part on the Constitution Act, 1982,which recognizes and confirms the existingancestral or treaty rights of Canada’s aborigi-nal peoples, the federal government adopteda revised policy on comprehensive land claimsin 1986.

Since land and resources fall within provincialjurisdiction, the provinces were called upon toparticipate in negotiations. In Québec, onlythe Crees and the Inuit, in 1975, and theNaskapis, in 1978, signed agreements fol-low-ing negotiations on their comprehensive landclaims. For a number of years now, theAttikameks and the Innu have been negotiat-ing a similar claim. In 2000, a major step wastaken in the negotiations with the Innu of the

Conseil tribal Mamuitun. The three partiesagreed on a common approach that is nowused as the basis for negotiation.

Specific claimsThe federal policy defines specific claims asthose dealing with the administration ofreserve land and other property of Indianbands, and with observance of treaties. Theseclaims are generally negotiated with the fed-eral government, since the provinces are rarelyconcerned.

Self-governmentSelf-government is at the heart of the discus-sions between aboriginal peoples and govern-ments. It was the main subject of four consti-tutional conferences of Canadian first minis-ters and aboriginal leaders held in Ottawabetween 1983 and 1987. During these con-ferences, the aboriginal peoples failed to havethe principle of an inherent right of self-gov-ernment written into the CanadianConstitution.

21

ABORIGINAL CLAIMS

Québec took a position in support of any con-stitutional amendment recognizing the rightof self-government of aboriginal peoples, pro-vided the necessary agreements were negoti-ated with the governments concerned.

In May 1991, the Commission on the Politicaland Constitutional Future of Québec (theBélanger-Campeau Commission) received 10briefs from aboriginal groups. They alldemanded recognition of their right of self-determination, their ancestral and territorialrights, and their right to autonomy in themanagement of their affairs. The Commissionstressed that Quebecers in general are eagerto find grounds for agreement that would besatisfactory to both aboriginal people and thegeneral public.

A few years later, in August 1995, the federalgovernment adopted a policy to implementthe inherent right of aboriginal peoples toself-government.

The Inuit formed the Nunavik ConstitutionalCommittee in 1989 and submitted to theQuébec government a project for regionalgovernment that was the subject of negotia-tions with the governments of Québec andCanada. In 1999, the three parties signed apolitical accord for the creation of the NunavikCommission. The Commission was set up inNovember 1999 to make recommendationson a form of government for Nunavik. It con-cluded its work in March and released itsreport in April 2001. The signatory parties tothe political accord will eventually undertakenegotiations based, in whole or in part, on therecommendations found in the Commission’sreport.

The Micmacs of Gespeg have also initiatednegotiations on self-government with thegovernments of Québec and Canada. Thethree parties signed a framework agreementin May 1999.

Other claimsMany other concerns have led to claims byaboriginal peoples, some of which involveeconomic, cultural and community develop-ment. Others involve health and social ser-vices, justice, energy, etc.

22

Québec’s relations with the aboriginal peoplesare relatively recent and have moved forwardsignificantly only since the 1960s. This is inlarge part owing to the Constitution Act,1867 and the Indian Act, which made theCanadian government responsible for theIndians and the lands reserved for them.

Gradually, the federal government createdservices in education, health, social services,housing and so on. Prior to 1950, Indianaffairs were successively the responsibility of anumber of departments. In 1953, theDepartment of Northern Affairs and NationalResources was given responsibility for Indianaffairs. In 1966, the Canadian governmentcreated the Department of Indian Affairs andNorthern Development.

For one hundred years, relations between theQuébec government and the aboriginal peo-ples were sporadic. Nevertheless, in 1925,Québec adopted a law enabling it to consti-tute a bank of public lands for the future useof the Amerindians. Three years later, in 1928,the Québec government created beaverreserves, territories where the Amerindianswere given exclusive trapping rights.

Significant stepsMany organizations and events have seen thelight of day over the last 40 years, principally:

1963 – The Direction générale du Nouveau-Québec

By creating the Direction générale duNouveau-Québec within the Department ofNatural Resources, the Québec governmentrenewed relations with the aboriginal peoplesliving on its territory. It began offering servicesto the Inuit and to a few Cree communities.Québec’s first efforts were centred on educa-tion, and it immediately declared its intentionto respect Inuit language and culture.

1969 - Brief submitted by the Québec IndianAssociation

This brief, submitted to the Québec govern-ment, dealt with the territorial rights ofIndians.

1969 – The Government of Canada’s White Paperon Indian policy

In this White Paper, the federal governmentannounced its intention to abolish the IndianAct and proposed that provincial governmentsassume the same responsibilities towardIndians as they assume toward other citizens.These proposals were widely rejected byAmerindians and the federal government didnot act on the White Paper, but the questionof the role of the provinces vis-à-vis aboriginalpeoples had been brought into sharp focus.

1969 - Right to vote in Québec

Amerindians obtained the right to vote inprovincial elections. They had obtained theright to vote in federal elections in 1960.

1970 - La Commission de négociations desaffaires indiennes

As a result of the discussions on the federalWhite Paper, the Québec government set upthe Commission de négociations des affairesindiennes (CNAI). The mandate of thisCommission demonstrates a desire to estab-lish close ties with the aboriginal peoples. Inits report, the Commission raised the problemof territorial integrity in relations betweenQuébec and aboriginal people.

1971 - Dorion Commission

In the course of its mandate, the Commissiond’étude sur l’intégrité du territoire du Québec(Dorion Commission) submitted a report onthe territorial aspects of the Indian questionand concluded that Indians have rights toparts of Québec’s territory. The Commissionthus confirmed that the territorial issue is atthe heart of relations between aboriginal peo-ples and the government, and advocated anew framework for establishing relations, rec-ommending that the Québec government begiven jurisdiction over the Amerindians andInuit on its territory.

1973 - Policy on land claims

The Canadian government adopted the firstpolicy on comprehensive land claims by abo-riginal peoples.

1973 - Calder and Malouf decisions

Two decisions, one by the Supreme Court ofCanada (Calder) and the other by the SuperiorCourt of Québec (Malouf), mark a turningpoint in the relations between Québec andaboriginal people. The first confirmed theexistence of territorial rights for the aboriginalpeoples of Canada. The second recognizedthe rights of the Crees and the Inuit on theterritories Canada ceded to Québec under

23

MAJOR MILESTONES

the Québec Boundaries Extension Act of 1898and 1912. The Malouf decision called for thesuspension of work on the massive James Bayhydroelectric projects.

Following the Malouf decision, lengthy, inten-sive negotiations were begun, giving rise, in1975, to the signing of the James Bay andNorthern Québec Agreement with the Creesand Inuit.

1975 – The James Bay and Northern QuébecAgreement

This Agreement, the first modern large-scaleagreement negotiated in Québec and inCanada, laid the foundations for the social,economic and administrative organization ofa large part of the aboriginal population ofQuébec. It covers all aspects of the life of theCrees and the Inuit, who obtained 10 400 km2

of land in the form of real estate. Québec also

recognized their exclusive hunting, fishing andtrapping rights on Category II lands and theirpriority rights on all the land covered by theAgreement. The aboriginal signatoriesreceived $225 million in compensation fromthe federal and provincial governments forthe exchange of rights. The Bureau de coordi-nation de l’Entente was created, in particularto draft the legislation required to implementthe Agreement.

1978 – The Northeastern Québec Agreement

This Agreement with Québec’s Naskapi nationis largely based on the James Bay andNorthern Québec Agreement. The Naskapireceived full ownership of 285 km2 of landand exclusive or priority rights to hunt, fishand trap on about 4 150 km2. The govern-ments paid $9 million in compensation for theexchange of rights.

1978 – Creation of the Secrétariat des activitésgouvernementales en milieu amérindien et inuit(SAGMAI)

A structure was set up to handle the entireaboriginal issue in Québec. SAGMAI replacedthe Direction générale du Nouveau-Québecand the Bureau de coordination de l’Entente.SAGMAI, a coordinating agency within theConseil exécutif, reporting directly to thePrime Minister, was responsible for drawingup government policy on aboriginal affairs. Italso coordinated the activities of governmentagencies and departments that offer directservices to aboriginal people. This decentral-ized approach is an important factor inQuébec’s relations with aboriginal people.

1978 – First summit meeting in Québec City

The first official meeting between the Québecgovernment and the 40 band chiefs, alongwith 85 other aboriginal representatives, washeld in Québec City from December 13 to 15,1978.

1982 – The Constitution Act, 1982

The Constitution Act, 1982 wrote the recog-nition and confirmation of the existing rights,whether ancestral or deriving from treaties, ofthe aboriginal peoples (Indians, Inuit, Métis)into the Canadian Constitution. This is a majorchange in Canada’s legal system.

1982 - Statement of principles

On November 30, 1982, the Québec NativePeople’s Coalition presented a set of principlesto the government.

1983 - Adoption of the 15 principles

On February 9, 1983, the Québec governmentadopted 15 principles recognizing the aborig-inal nations and the need to establish harmo-nious relations with them. These principles areas follows:

1) Québec recognizes that the aboriginalpeoples of Québec constitute distinctnations, entitled to their own culture,language, traditions and customs, aswell as having the right to determine,by themselves, the development oftheir own identity.

2) It also recognizes the right of aboriginalnations, within the framework ofQuébec legislation, to own and to con-trol the lands that are attributed tothem.

3) These rights are to be exercised bythem as part of the Québec communityand hence could not imply rights ofsovereignty that could affect the territo-

24

rial integrity of Québec.

4) The aboriginal nations may exercise, onthe lands agreed upon between themand the government, hunting, fishingand trapping rights, the right to harvestfruit and game and to barter betweenthemselves. Insofar as possible, theirtraditional occupations and needs areto be taken into account in designatingthese lands. The ways in which theserights may be exercised are to bedefined in specific agreements conclud-ed with each people.

5) The aboriginal nations have the right totake part in the economic developmentof Québec. The government is also will-ing to recognize that they have theright to exploit to their own advantage,within the framework of existing legis-lation, the renewable and unrenewableresources of the lands allocated tothem.

6) The aboriginal nations have the right,within the framework of existing legis-lation, to govern themselves on thelands allocated to them.

7) The aboriginal nations have the right tohave and control, within the frameworkof agreements between them and thegovernment, such institutions as maycorrespond to their needs in matters ofculture, education, language, healthand social services as well as economicdevelopment.

8) The aboriginal nations are entitled with-in the framework of laws of generalapplication and of agreements betweenthem and the government, to benefitfrom public funds to encourage thepursuit of objectives they esteem to befundamental.

9) The rights recognized by Québec to theaboriginal peoples are also recognizedto women and men alike.

10) From Québec’s point of view, the pro-tection of existing rights also includesthe rights arising from agreementsbetween aboriginal peoples andQuébec concluded within the frame-work of land claims settlement.Moreover, the James Bay and Nor-thern Québec Agreement and theNortheastern Québec Agreement are tobe considered treaties with full effect.

11) Québec is willing to consider that exist-ing rights arising out of the RoyalProclamation of October 7, 1763, con-cerning aboriginal nations be explicitlyrecognized within the framework ofQuébec legislation.

12) Québec is willing to consider, case bycase, the recognition of treaties signedoutside Canada or before Confede-ration, aboriginal title, as well as therights of aboriginal nations that wouldresult therefrom.

13) The aboriginal nations of Québec, dueto circumstances that are peculiar tothem, may enjoy tax exemptions inaccordance with terms agreed uponbetween them and the government.

14) Were the Government to legislate onmatters related to the fundamentalrights of the aboriginal nations as rec-ognized by Québec, it pledges to con-sult them through mechanisms to bedetermined between them and theGovernment.

15) Once established, such mechanismscould be institutionalized so as to guar-antee the participation of the aboriginalnations in discussions pertaining totheir fundamental rights.

1983 - Parliamentary committee on aboriginalrights

For three days, 17 aboriginal groups present-ed briefs to the committee. It was the firsttime the aboriginal peoples had been invitedto address the National Assembly of Québec.

25

1983 to 1987 - Constitutional conferences

Between 1983 and 1987, four constitutionalconferences brought together the first minis-ters of Canada and representatives of the abo-riginal peoples in order to spell out the aboriginal rights to be written into theCanadian Constitution. These conferenceswere a failure.

1985 - Resolution of the National Assembly

On March 20, 1985, the National Assembly ofQuébec adopted a motion recognizing theaboriginal nations and their rights in order tomake official and publicize the major princi-ples to be respected by the government in itsrelations with the aboriginal peoples. TheNational Assembly encouraged the govern-ment to conclude agreements with the abo-riginal peoples in the following areas: self-government, culture, language, traditions,possession of and control over land, hunting,fishing, trapping, participation in the manage-ment of wildlife resources and participation ineconomic development. The resolution readsas follows:

The National Assembly:

Recognizes the existence of the Abenaki,Algonquin, Attikamek, Cree, Huron, Micmac,Mohawk, Montagnais, Naskapi and Inuitnations in Québec;

Recognizes existing aboriginal rights andthose set forth in the James Bay and NorthernQuébec Agreement and the NortheasternQuébec Agreement;

Considers these agreements and all futureagreements and accords of the same natureto have the same value as treaties;

Subscribes to the process whereby theGovernment has committed itself with theaboriginal peoples to better identifying anddefining their rights—a process which restsupon historical legitimacy and the importancefor Québec society to establish harmoniousrelations with the native peoples, based onmutual trust and a respect for rights;

Urges the Government to pursue negotiationswith the aboriginal nations based on, but notlimited to, the fifteen principles it approved onFebruary 9, 1983, subsequent to proposalssubmitted to it on November 30, 1982, and toconclude with willing nations, or any of theirconstituent communities, agreements guaran-teeing them the exercise of:

a) the right to self-government withinQuébec;

b) the right to their own language, cultureand traditions;

c) the right to own and control land;

d) the right to hunt, fish, trap, harvest andparticipate in wildlife management;

e) the right to participate in, and benefitfrom, the economic development ofQuébec so as to develop as distinctnations having their own identity andexercising their rights within Québec;

Declares that the rights of aboriginal peoplesapply equally to men and women;

Affirms its will to protect, in its fundamentallaws, the rights included in the agreementsconcluded with the aboriginal nations ofQuébec; and

Agrees that a permanent parliamentary forumbe established to enable the aboriginal peo-ples to express their rights, needs and aspira-tions.

26

1987 - The Secrétariat aux affaires autochtones

SAGMAI became the Secrétariat aux affairesautochtones (SAA) with a mandate enlargedbeyond its initial role with respect to the abo-riginal peoples and government departmentsand agencies to include negotiations with theaboriginal peoples and the implementation ofthe agreements. It was also required to pro-vide information to the general public and notonly to the aboriginal peoples of Québec.

1989 – Recognition of the Malecite nation

On May 30, 1989, the National Assembly rec-ognized the Malecites as the eleventh aborig-inal nation in Québec.

1990 – The Sparrow case

The Supreme Court of Canada handed downa decision recognizing that subsistence fishingis an aboriginal right protected by theConstitution.

1990 – The Sioui case

In this decision, the Supreme Court of Canadarecognized that a document signed in 1760constitutes a treaty within the meaning of theIndian Act. This document, which concernsonly the Huron-Wendat nation, does not pre-cisely define the rights recognized or the terri-tory to which the treaty applies.

1990 – The Oka crisis

A conflict breaks out between the Mohawkcommunity of Kanesatake and the municipal-ity of Oka concerning land that the municipal-ity wants to develop that is claimed by theMohawks. The situation degenerates into acrisis fuelled by prejudice on both sides, withdisastrous consequences on relations betweenaboriginal people and the population ofQuébec.

1996 – Report of the Royal Commission onAboriginal Peoples

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoplestabled a voluminous report on the situation ofaboriginal people in Canada. One of its con-clusions is that a fundamental change is need-ed in relations between aboriginal and non-aboriginal people.

1996 - The Adams and Côté decisions

The Supreme Court of Canada decided thatthe Mohawks of the Akwesasne reserve hadan ancestral right to fish for food in Lake St.Francis and that the Algonquins of Kitigan Zibihad the same right in the Bras Coupé-DésertZEC (controlled harvesting zone).

1997 – The Delgamuukw decision

In the Delgamuukw case, the Supreme Courtof Canada defined aboriginal title for the firsttime since the Constitution Act, 1982 waspassed. It also confirmed ancestral right spe-cific to aboriginal title.

1998 – Government guidelines on aboriginalaffairs

In a paper entitled Partnership DevelopmentAchievement, the Québec governmentreleased its guidelines regarding aboriginalaffairs. The guidelines provide, among otherthings, for the creation of an aboriginal devel-opment fund, the reaching of agreements andthe formation, in cooperation with aboriginalpeople, of a permanent political forum for dis-cussion.

1999 – The Marshall case

In the Marshall case, the Supreme Court ofCanada ruled that the Micmacs and the otheraboriginal groups of Nova Scotia mentionedin the 1760 and 1761 treaties could fish year-round without a licence to obtain essentialgoods. However, the decision does not reco-gnize a right to trade generally to earn finan-cial gains and stipulates that this right is sub-ject to regulation.

27

1999 – The Nunavik Commission

Representatives of Nunavik and of the gov-ernments of Québec and Canada signed apolitical accord for the creation of the NunavikCommission. The Commission’s chief task is tomake recommendations on a form of region-al government for Nunavik.

2000 – The Common Approach

The Conseil tribal Mamuitun and the govern-ments of Québec and Canada agree on acommon approach to be used as a frameworkfor negotiating the comprehensive land claimsettlement of the Innu communities ofBetsiamites, Essipit and Mashteuiatsh. Thecommunity of Natashquan joined the negoti-ations in 2001.

2001 – The report of the Nunavik Commission

The Nunavik Commission released its reportentitled Let us share, Mapping the RoadToward a Government for Nunavik, at MakivikCorporation’s annual meeting, April 5, 2001,in Kuujjuarapik.

2001 – Tricentennial of the Great Peace ofMontréal

The Government of Québec was associated,as a major partner, in the celebrations com-memorating one of the most important diplo-matic events in the history of relationsbetween the aboriginal peoples and NewFrance: the signature of the Great Peace ofMontréal in 1701.

2001 – Agreement in principle with the Crees

On October 23, 2001, the Grand Council ofthe Crees and the Québec government signedan agreement in principle for better political,economic and social relations between theCrees and Québec. In particular, the agree-ment covers economic development of theCrees, forestry, and the Eastmain and Ruperthydro-electricity projects.

28

This overview does not exhaust the aboriginalquestion. If it throws a little more light on thecomplex situation of the Amerindians andInuit of Québec, a major objective will havebeen reached.

While it must be admitted that the gapbetween aboriginal people and otherQuebecers is still wide, the fact remains thatsignificant bases for a rapprochement havebeen laid over the past few years. This is illus-trated by a number of examples: joint man-agement of the Grande-Cascapédia river bythe Micmacs of Gesgapegiag and non-aborig-inal people, sawmills operated by theAttikameks of Obedjiwan and DonohueCorporation, and by the Crees of Waswanipiand Domtar Inc. Farther north, two miningcompanies have set up a business partnershipwith the Inuit and the Crees to develop theKattinik (Raglan) and Troïlus mine sites.

Lastly, with the adoption of the governmentguidelines on aboriginal affairs, major issueshave been determined, particularly at thesocial and economic levels. In three years, thenew government approach has led to the sig-nature of ten framework agreements and dec-larations of understanding and mutualrespect, about fifty agreement renewals in thefields of public security, wildlife, justice,health, culture and education, and sometwenty specific agreements on economic andcommunity development with 43 aboriginalcommunities.

29

CONCLUSION

Photos

Page couverture

An Inuit girl.© Tourisme Québec, Heiko Wittenborn

An Amerindian at the Aboriginal Interband Gamesin Mashteuiatsh.SAA, Gilles Chaumel

Young people of Kangiqsualujjuaq at the foot of aninukshuk.© Tourisme Québec, Heiko Wittenborn

An Algonquin from Kitcisakik.SAA, Louise Séguin

Véronique Mark, an Innu from Pakuashipi, on theBasse-Côte-Nord.Guy de Sénailhac

Délima Niquay, an Attikamek, and her daughter. SAA, Gilles Chaumel

Page 1

A Cree from Oujé-Bougoumou.Harry Bosum

Page 3

A Cree from Oujé-Bougoumou.Harry Bosum

A Cree from Oujé-Bougoumou.SAA, Louise Séguin

The Papinachois resort, near the Innu village ofBetsiamites.

Page 5

An Amerindian woman participating in the festivi-ties of the Great Peace of Montréal 1701-2001. Pierre-Sarto Blanchard

The Secrétariat aux affaires autochtones takes partin regional fairs with aboriginal people, for ins-tance at Baie-Comeau, with Innu artist Jean-LucHervieux.SAA, Lucie Dumas

Page 6

Cree children at a childhood centre.MFE, Louis L’Écuyer

Page 7

Some of the members of the Algonquin Thuskyfamily: top row, Véronique, her mother Blanche,her sister Lucie and her niece Jennifer Wabamoose;middle row, her niece Juliette Chief and her daugh-ter Rachel; bottom row, Philippe Nottaway, hernephew, with his girlfriend Marguerite Ratt.SAA, Gilles Chaumel

An Inuit from Nunavik. © Tourisme Québec, Heiko Wittenborn

Page 11

An Attikamek from Obedjiwan.SAA, Gilles Chaumel

Algonquins from Kitigan Zibi.SAA, Louise Séguin

Page 12

Young Algonquins from Timiskaming listen to theteachings of Julie Mowatt and Anna Mowatt, anelder.SAA, Louise Séguin

Page 13

The Crown Prosecutor, Éric Morin, SergeantRenaud Ringuette, responsible for the Sûreté duQuébec station in Schefferville, Moïse and TommyVollant, respectively chief constable and constableof Matimekosh–Lac-John at a hearing of theItinerant Court in Schefferville.

Page 15

A young Inuit from Inukjuak.Gilles H. Picard

The Innu singer Florent Vollant.SAA, Ann Picard

Page 16

A view of Kuujjuaq. Joseph-Marc Laforest

An Attikamek host of the Manawan communityradio station.SAA, Gilles Chaumel

Page 17

An Algonquin from Lac-Simon.Alex Cheezo

The Attikamek Wemogaz service station in Wemo-taci.SAA, Daniel Larocque

Page 19

Evelyn O’Bomsawin, an Abenaki woman fromOdanak and former president of the Québec Na-tive Women’s AssociationSAA, Gilles Chaumel

The Betsiamites band council.SAA, Ann Picard

Chief Allison Metallic and the members of theListuguj Mi’gmaq First Nation Council at the sign-ing of a framework agreement with the Ministerfor Native Affairs, Guy Chevrette, in June 2001.SAA, Ann Picard

Page 21

An Inuit from Puvirnituq.Marc-Adélard Tremblay

Press conference announcing the CommonApproach, July 6, 2000: Michèle Rouleau, presen-ter, Guy Chevrette, Minister for Native Affairs,chiefs René Simon from Betsiamites, Clifford Moarfrom Mashteuiatsh and Denis Ross from Essipit,and Pierre Pettigrew, federal Minister ofInternational Trade.SAA, Ann Picard

31

Page 22

The Nunavik Commission held extensive publicconsultations in the 14 northern villages, includingTasiujaq.Marc-Adélard Tremblay

The Commission exchanged views with secondarystudents in each community visited.Makivik Corporation, Stephen Hendrie

Page 23

An Algonquin woman from Lac-Simon.Alex Cheezo

Page 24

The LG-2 spillway.Hydro-Québec

Page 25

The parliamentary committee on aboriginal rightsin November 1983.SAA, Marc Lajoie

Page 26

Cree workers at the Nabakatuk sawmill in Was-wanipi.Serge Gosselin

Page 27

Cree Grand Chief Ted Moses and Prime MinisterBernard Landry at the signing of the agreement inprinciple on October 23, 2001.Clément Allard

Page 28

Young Algonquins from Lac-Simon at the parade ofthe First Peace Ambassadors of the Great Peace ofMontréal, June 21, 2001.Corporation des fêtes de la Grande Paix de Montréal1701-2001, René Fortin

Page 29

A young girl from Lac-Rapide.SAA, Gilles Chaumel

The Tree of Peace, formed of sculptures created bystudents from Montréal for the exhibition LivingWords: Aboriginal Diplomats of the 18th Century,presented by the McCord Museum of CanadianHistory in the summer of 2001.McCord Museum of Canadian History, Montréal, MarilynAitken

Forty totem poles for peace were installed at theentrance to the Montréal Botanical Garden duringthe summer of 2001.SAA, Ann Picard

32