TCA Reading Material 3 - 2013 (1)

Transcript of TCA Reading Material 3 - 2013 (1)

-

7/30/2019 TCA Reading Material 3 - 2013 (1)

1/8

CICLO DE LICENCIATURA EN INGLS

TALLER DE COMPETENCIAS ACADMICAS

-----------------------------------------------------UNL Licenciatura en Ingls

TCA Reading Material 31

Writing in the disciplines: Research evidence for specificity

These notes are an adaptation of:

Hyland K., 2009, Writing in the disciplines: Research evidence for specificity, TaiwanInternational ESP Journal, Vol. 1: 1, 5-22, 2009

and

Hyland K., 2000, Disciplinary Discourses: Social Interactions in Academic Writing,Singapore: Pearson Education Asia.

Introduction

Academic writing, much like any other kind of writing, is only effective when writers use

conventions that other members of their community find familiar and convincing. Essentially

the process of writing involves creating a text that we assume the reader will recognise and

expect, and the process of reading involves drawing on assumptions about what the writer is

trying to do. It is this writer-reader coordination which enables the co-construction of

coherence from a text. Scholars and students alike must therefore attempt to use

conventions that other members of their discipline, whether journal editors and reviewers or

subject specialist teachers and examiners, will recognise and accept. Because of this

discourse analysis has become a central tool for identifying the specific language features of

target groups.

Discourse analytic studies show considerable variation in academic language use across a

range of dimensions. Halliday (1989), for example, found greater nominalization,

impersonalisation and lexical density in written compared with spoken texts.Also, Swales

made clear in 1990 that we need to see community and genre together to offer a framework

of how meanings are socially constructed by forces outside the individual. Research on

language variation across the disciplines is rapidly becoming one of the dominant paradigms

in EAP (e.g. Hyland, 2004; Flottum et al., 2006; Hyland & Bondi, 2006).

Specificity represents a key way in which we understand and practice English for Academic

and Specific Purposes. Specificity here refers to a fairly uncontroversial idea: that we

communicate as members of social groups and that different groups use language to

conduct their business, define their boundaries, and manage their interactions in particular

ways.

Disciplinary specificityThe idea of discipline has become important in EAP as we have become more sensitive to

the ways genres are written and responded to by individuals acting as members of social

groups. Essentially, we can see disciplines as language using communities and the term

helps us join writers, texts and readers together. Communities provide the context within

which we learn to communicate and to interpret each others talk, gradually acquiring the

specialized discourse competencies to participate as group members. So we can see

-

7/30/2019 TCA Reading Material 3 - 2013 (1)

2/8

CICLO DE LICENCIATURA EN INGLS

TALLER DE COMPETENCIAS ACADMICAS

-----------------------------------------------------UNL Licenciatura en Ingls

TCA Reading Material 32

disciplines as particular ways of doing things - particularly of using language to engage withothers in certain recognised and familiar ways.

Academic texts are about persuasion and this involves making choices to argue in ways

which fit the communitys assumptions, methods, and knowledge. This is how Wells (1992:

290) sees matters:

Each subject discipline constitutes a way of making sense of human experience

that has evolved over generations and each is dependent on its own particular

practices: its instrumental procedures, its criteria for judging relevance and

validity, and its conventions of acceptable forms of argument. In a word each has

developed its own modes of discourse. To work in a discipline, then, we need to

be able to engage in these practices and, in particular, in its discourses.

So disciplines structure the work we do within wider frameworks of beliefs and provide the

conventions and expectations that make texts meaningful. We can see this if we picture the

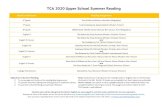

disciplines as spread along a line (See Figure 1), with the sciences at one end and the

humanities at the other.

SCIENCES SOCIAL SCIENCES HUMANITIES

Empirical and objective Explicitly interpretive

Linear and cumulative growth of knowledge Dispersed knowledge

Experimental methods Discursive argument

Quantitative methods Qualitative methods

More concentrated readership More varied readership

Highly structured genres More fluid discourses

Figure 1 Continuum of academic knowledge (after Coffin et al., 2003)

In the sciences new knowledge is accepted by experimental proof. Science writing reinforces

this by highlighting a gap in knowledge, presenting a hypothesis related to this gap, and

then reporting experimental findings to support this in a standard Introduction-Methods-

Results-Discussion format. The humanities such as literature, history and philosophy, on the

other hand, largely rely on case studies and narratives while claims are accepted on strength

of argument. The social sciences fall between these extremes. Disciplines such as Sociology,

Economics and Applied Linguistics have partly adopted methods of the sciences, but in

applying these to human data they have to give far more attention to explicit interpretation

than those fields. In other words, academic discourse helps to give identity to a discipline.

Metadiscourse can be realized through a range of linguistic devices fromexclamation marks to whole clauses and sentences.

Textual metadiscourse is used to organize propositional information in ways that the reader

will find coherent and convincing.

-

7/30/2019 TCA Reading Material 3 - 2013 (1)

3/8

CICLO DE LICENCIATURA EN INGLS

TALLER DE COMPETENCIAS ACADMICAS

-----------------------------------------------------UNL Licenciatura en Ingls

TCA Reading Material 33

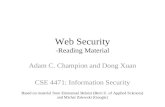

Category Function ExamplesLogical connectives: mainly conjunctionsand adverbial phrases that help readersto interpret pragmatic connectionsbetween ideas by signaling additive,resultive, and contrastive relations in thewriters thinking.

Express semanticrelation between mainclauses

in addition / but / thus/ and

Frame markers signal text boundaries orelements of text structure

Explicitly refer todiscourse acts or textstages

finally / to repeat /here we try tosequence: first, then,a, b, 1, 2to label text stages: toconclude, in sumto announce discoursegoals: I argue here, mypurpose is

Evidentials are the reporting of an ideafrom another source (introduction toquotes, paraphrases, summaries,etc), toestablish an authorial command of theliterature. Editorials distinguish who isresponsible for a position.

Refer to sourceinformation from othertexts

According to X (1990) /Y (1999) states

Endophoric markers are expressionswhich refer to other parts of the text toaid the recovery of the writers meaning.

Refer to information inother parts of the text

noted above / see Fig./ in section 2 / seebelow

Code glosses supply additionalinformation, by explaining or expandingwhat has been said.

Help readers grasp thewriters intended

meaning.

namely / e.g. / such as/ i.e. / in other words /this is called

Interpersonal metadiscourse allows writers to express a perspective towards theirpropositions and their readers.

Hedges Withhold writers fullcommitment tostatements

might / perhaps /possible / about

Boosters Emphasize force orwriters certainty in

message

in fact / definitely / Its clear

Attitude markers indicate the writersaffective attitude to textual information,expressing surprise, importance,obligation, agreement.

Express writers attitudeto propositional content

unfortunately / Iagree / X claims

Relational markers are devices whichexplicitly address readers to focus theirattention or include them as discourseparticipants.

Explicitly refer to orbuild relationship withreader

frankly / note that /you can seeSecond personpronouns,imperatives, questionforms

Person markers refer to the degree of

explicit author presence in a text

Explicit reference to

author(s)

I / we / my / mine /

our

Logical connectives: An important aspect of academic writing is to transitioneffectively between sentences, ideas, and paragraphs. By becoming familiar with differentways that you can transition between ideas and using these in your writing, you will producemore reader-friendly compositions.

According to the APA Manual, here are some of the most common transition words withexamples of some in use:

time links: then, next, after, while, since

-

7/30/2019 TCA Reading Material 3 - 2013 (1)

4/8

CICLO DE LICENCIATURA EN INGLS

TALLER DE COMPETENCIAS ACADMICAS

-----------------------------------------------------UNL Licenciatura en Ingls

TCA Reading Material 34

After discussing the impact of testing on multilingual students, I am going to argue that newtesting standards need to be developed.

cause-effect links: there, consequently, as a result

Consequently, by giving the students practice in becoming critical readers, we are at thesame time helping them towards becoming more self-reliant writers, who are both self-critical and who have the skills to self-edit and revise their writing (Rollinson, 2005:. 29).

addition links: in addition, moreover, furthermore, similarly

In addition to soliciting feedback from peers and teachers of both ENG 1311 and ESOL

1311, the survey was piloted on one class, revised, piloted again on two classes, and revisedagain (Ruecker, 2010: 8).

contrast links: but, conversely, nevertheless, however, although

John Schilb's deconstructive critical program is constructionist insofar as it foregrounds therole of language in the shaping of history and historical understanding. However, Schilb'scriticism of traditionalist historiography is not fully constructionist (at least not yet)(Crowley, 1994: 11). Citation practicesOne of the most striking differences in disciplinary uses of language is in citation practices.

The inclusion of references to the work of other authors is obviously central to academic

persuasion. This is because it not only helps establish a persuasive framework for the

acceptance of arguments by showing how a text depends on previous work in a discipline,

but also as it displays the writers credibility and status as an insider. It helps align him or

her with a particular community or orientation and confirms that this is someone who is

aware of, and is knowledgeable about, the topics, approaches, and issues which currently

interest and inform the field.

Basically, the differences reflect the extent writers can assume a shared context with

readers. In Kuhns(1962) normal science model, natural scientists produce public knowledge

through cumulative growth. Problems tend to emerge on the back of earlier problems as

results throw up further questions to be followed up with further research so writers do not

need to report research with extensive referencing. The people who read those papers are

often working on the same problems and are familiar with the earlier work. They have a

good idea about the procedures used, whether they have been properly applied, and what

results mean. In the humanities and social sciences, on the other hand, the literature is

more dispersed and the readership more heterogeneous, so writers cannot presuppose a

shared context but have to build one far more through citation.

Reporting verbsThere are also major differences in the ways writers report others work, with results

suggesting that writers in different fields draw on very different sets of reporting verbs to

refer to their literature (Hyland, 1999). Among the higher frequency verbs, almost all

instances of say and 80% of think occurred in philosophy and 70% of use in electronics. It

-

7/30/2019 TCA Reading Material 3 - 2013 (1)

5/8

CICLO DE LICENCIATURA EN INGLS

TALLER DE COMPETENCIAS ACADMICAS

-----------------------------------------------------UNL Licenciatura en Ingls

TCA Reading Material 35

turns out, in fact, that engineers show, philosophers argue, biologists find and linguistssuggest. The most common forms across the disciplines are shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Most frequent reporting verbs.

Soft Disciplines

Philosophy say, suggest, argue, claimSociology argue, suggest, describe, discussApplied Ling. suggest, argue, show, explainMarketing suggest, argue, demonstrate,

propose

Hard Disciplines

Biology describe, find, report, showElec. Eng. show, propose, report, describeMech. Eng. show, report, describe, discussPhysics develop, report, study

These preferences seem to reflect broad disciplinary purposes. So, the soft fields largely use

verbs which refer to writing activities, like discuss, hypothesize, suggest, argue. These

involve the expression of arguments and allow writers to discursively explore issues while

carrying a more evaluative element in reporting others work

Engineers and scientists, in contrast, prefer verbs which point to the research itself like

observe, discover, show, analyse, and calculate, which represent real world actions. This

emphasis on real-world activities helps scientists represent knowledge as proceeding from

impersonal lab activities rather than from the interpretations of researchers.

Overall, the most common forms used were suggest, argue, find, show, describe, propose,

and report. For instance, in referencing research from another source without quoting you

could use expressions like the following:

Smith and Daniels (2003) suggested that multilingual students bring a number ofcompetencies to the classroom that are often unrecognized by their teachers.

Zhu (2001) reported that peer review between L1 and L2 learners improved asstudents were trained in the process.

Note that APA style asks authors to use the past tense when citing previous research while

MLA style asks authors to use the present tense. When you read academic writing in your

field, note the type of citation style used and also the ways authors reference previous work

in their writing.

Reference

Hyland, K. (2004). Disciplinary discourses: Social interactions in academic writing. Ann

Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

HedgesHedges and boosters are communicative strategies for increasing or reducing the force of

statements. Boosters (e.g. clearly, obviously, of course) allow writers to express their

certainty in what they say to mark involvement and solidarity with their audience, stressing

shared information, group membership and direct engagement with readers.

-

7/30/2019 TCA Reading Material 3 - 2013 (1)

6/8

CICLO DE LICENCIATURA EN INGLS

TALLER DE COMPETENCIAS ACADMICAS

-----------------------------------------------------UNL Licenciatura en Ingls

TCA Reading Material 36

Devices like possible, might, likely, perhaps and so on, collectively known as hedges, alsodiverge across fields. These function to withhold complete commitment to a proposition,

implying that a claim is based on plausible reasoning rather than certain knowledge. They

indicate the degree of confidence the writer thinks it might be wise to give a claim while

opening a discursive space for readers to dispute interpretations. (Hyland, 1996).

Hedges and boosters draw attention to the fact that statements dont just communicate

ideas, they also indicate the writers attitude to them and to readers.

Because they represent the writers direct involvement in a text, something that scientists

generally try to avoid, they are twice as common in humanities and social science papers

than in hard sciences, probably because arguments have to be expressed more cautiously.

Scientists tend to be concerned with generalisations rather than individuals, so greater

weight is put on the methods, procedures and equipment used rather than the argument.

Modals, then, are one way of helping to reinforce a view of science as an impersonal,

inductive enterprise while allowing scientists to see themselves as discovering truth rather

than constructing it.

Hedges Boosters

wouldmaysuggestindicateaboutassumepossible (possibly)could mightseem

show (that)find (that)determinewillit is clear / clearlythe fact thatdemonstrate (that)confirmknow / known thatparticularly

Self- mentionSelf-mention is another important feature which varies across disciplines. This concerns how

far writers want to intrude into their texts through use of I or we, or to use impersonal

forms. Presenting a discoursal self is central to the writing process, and we cannot avoid

projecting an impression of ourselves and how we stand in relation to our arguments,

discipline, and readers.

In the hard sciences, researchers are generally seeking to downplay their personal role in

the research to highlight the phenomena under study, the replicability of research activities,

and the generality of the findings. Scientists, then, try to distance themselves from

interpretations in ways that are familiar to most EAP teachers. They accomplish this by

either using the passive voice, dummy it subjects, or by attributing agency to inanimate

things. By subordinating their voice to that of nature, scientists rely on the persuasive force

of lab procedures rather than the force of their writing.

In contrast, in the humanities and social sciences, the first person allows writers to strongly

identify with a particular argument and to gain credit for an individual perspective.

Most of the work done in academic writing requires using third person. That means that

pronouns indicating the 1st and 2nd person should not be overused. However, as an

-

7/30/2019 TCA Reading Material 3 - 2013 (1)

7/8

CICLO DE LICENCIATURA EN INGLS

TALLER DE COMPETENCIAS ACADMICAS

-----------------------------------------------------UNL Licenciatura en Ingls

TCA Reading Material 37

academic writer, there are contexts where 1st and 2nd person is appropriate and can beused as an effective rhetorical strategy.

According to the APA Manual, personal pronouns should be used when referring to steps in

an experiment in order to create a false appearance of objectivity. For instance the Manual

gives the following example:

Correct: We reviewed the literature

Incorrect: The authors reviewed the literature.

Similarly, the editorial I or we is sometimes used by authors in academic publications.However, the APA Manual notes that we should refer just to the authors and not to other

researchers in the field.

Note that too much usage of 1st or 2nd person pronouns in academic writing makes the

writing appear too subjective and unprofessional and thus is generally seen negatively.

Directives

Another feature which supports the idea of disciplinary specificity is directives. These are

devices which instruct the reader to perform an action or to see things in a way determined

by the writer (Hyland, 2002). They are largely expressed through imperatives (e.g. consider,

note, imagine) and obligation modals (such as must, should, and ought). Overall, they direct

readers to three main kinds of activity: textual, physical and cognitive acts.

Textual acts direct readers to another part of the text or to another text (e.g. see Smith

1999, refer to table 2)

Physical acts direct readers how to carry out some action in the real-world (e.g. open the

valve, heat the mixture).

Cognitive acts instruct readers how to interpret an argument, explicitly positioning readers

by encouraging them to note, concede or consider some argument or claim in the text.

Generally, explicit engagement, where writers address readers directly in a text (Hyland,

2001a) is a feature of the soft disciplines, where writers are less able to rely on the

explanatory value of accepted procedures. Most directives in the soft fields are textual,

directing readers to a reference or table rather than telling them how they should interpret

an argument. So examples like these are common in the social sciences:

Argument in the hard knowledge fields, in contrast, is formulated in a highly standardised

code. Succinctness is valued by both editors and scientists, and directives allow writers to

cut directly to the heart of key issues in the text. Because of this we find a high proportion

of cognitive directives here which explicitly position readers by leading them through an

argument or emphasising what they should attend to:

(11) What has to be recognized is that these issues (Mechanical Eng)

Consider the case where a very versatile milling machine of type M5... (Electrical Eng)

-

7/30/2019 TCA Reading Material 3 - 2013 (1)

8/8

CICLO DE LICENCIATURA EN INGLS

TALLER DE COMPETENCIAS ACADMICAS

-----------------------------------------------------UNL Licenciatura en Ingls

TCA Reading Material 38

ReferencesBiber, D. (2006). University language: A corpus-based study of spoken and written

registers. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Coffin, C., Curry, M., Goodman, S., Hewings, A., Lillis, T., & Swann, J. (2003). Teaching

academic writing: A toolkit for higher education. London: Routledge.

Flottum, K., Dahl, T. and Kinn, T. (eds). (2006) Academic voices - Across languages and

disciplines. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Gimenez, J. (2009). Beyond the academic essay: Discipline-specific writing in nursing and

midwifery. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 7 (3), 151-164.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1989). Spoken and written language. Oxford: OUP.

Hinkel, E. ( 2002). Second language writers texts. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hyland, K. (1996). Writing without conviction? Hedging in scientific research articles. Applied

Linguistics, 17 (4), 433-454.

Hyland, K. (1999). Academic attribution: Citation and the construction of disciplinary

knowledge. Applied Linguistics, 20 (3), 341-267.

Hyland, K. (2001a). Bringing in the reader: Addressee features in academic articles. Written

Communication, 18 (4), 549-574.

Hyland, K. (2001b). Humble servants of the discipline? Self-mention in research articles.

English for Specific Purposes, 20(3), 207-226.

Hyland, K. (2002). Directives: Power and engagement in academic writing. Applied

Linguistics. 23, 215-239.

Hyland, K. (2004). Disciplinary discourses. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Hyland, K. (2005). Metadiscourse. London: Continuum.

Hyland, K. (2008). As can be seen: Lexical bundles and disciplinary variation. English for

Specific Purposes, 27 (1), 4-21.

Hyland, K. (2009). Academic discourse. London: Continuum.Hyland, K. & Bondi, M. (Eds.) (2006). Academic discourse across disciplines. Frankfort: Peter

Lang.

Hyland, K. & Tse, P. (2007). Is there an academic vocabulary? TESOL Quarterly, 41 (2),

235-254.

Kuhn, T. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Kuo, C-H. (1999). The use of personal pronouns: Role relationships in scientific journal

articles. English for Specific Purposes, 18 (2), 121-138.

Swales, J. (2004). Research genres. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wells, G. (1992). The centrality of talk in education. In K. Norman (ed.), Thinking voices:

The work of the national oracy project. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Ken Hyland, Centre for Applied English Studies, University of Hong Kong

TIESPJ, Vol. 1: 1, 2009