Lecture 8: Excitation-Contraction Coupling. Summary From Last Lecture.

Summary of the Last Lecture

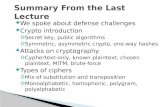

description

Transcript of Summary of the Last Lecture

Summary of the Last Lecture

• THREE PRODUCTS: INSURANCE, HOUSINGFINANCE, AND REMITTANCES

THREE PRODUCTS: INSURANCE, HOUSINGFINANCE, AND REMITTANCES

CEMEX Patrimonio Hoy (Equity Today) Program

• CEMEX’s housing microfinance product uses similar principles. CEMEX is one of the largest cement companies in the world but was faced with increasing competition in its home country of Mexico.

CEMEX Patrimonio Hoy (Equity Today) Program

• The century-old, global building-materials supplier wanted to increase sales of cement to poor and lower-income Mexicans who improve their houses incrementally over years.

CEMEX Patrimonio Hoy (Equity Today) Program

• Admitting it knew little about the needs of this market, CEMEX researched home-building practices in local communities, especially the rotating savings and credit associations called tandas.

CEMEX Patrimonio Hoy (Equity Today) Program

• The results were heartening: sales of cement increased, housing improvements increased, and brand recognition was strengthened. While initially designed as a gesture of social responsibility, CEMEX gradually realized that helping the poor could be achieved while making a profit.

CEMEX Patrimonio Hoy (Equity Today) Program

• This realization led to a greater rollout of Patrimonio Hoy, which has now helped 185,000 Mexican families build the equivalent of 95,000 ten-square-meter rooms.

ARGOZ’s Lease-Option Contracts

• This example also highlights a nonbank source. In the absence of bank involvement, private land developers sometimes put their own financing packages together for low-income buyers.

ARGOZ’s Lease-Option Contracts

• Developers like ARGOZ, El Salvador’s largest land developer, buy the land, put in roads and utility hookups, and build the homes. When target buyers can’t get loans, ARGOZ lends the money, too.

ARGOZ’s Lease-Option Contracts

• ARGOZ offers 10-year lease-options contracts for land purchases at rates similar to commercial bank rates for housing. Buyers legally own the land only after the final loan payment.

ARGOZ’s Lease-Option Contracts

• ARGOZ does not require a down payment, and insurance is provided. After a family purchases a plot, the company continues to supply financing for construction or emergencies. ARGOZ is a highly profitable company, and low-end housing is one of its solidly profitable lines of business.

Alternative vs. Bank Financing

• Although it is somewhat ironic that CEMEX and ARGOZ stepped in to provide financing when no financial institutions would do so, we admit that banks may have good reasons for avoiding the low-income housing market.

Alternative vs. Bank Financing

• Construction-industry players have hooks that banks lack. CEMEX and ARGOZ enjoy built-in risk control because the buyers rely on them for their access to housing, while banks need some other way to get a legal hold—such as a mortgage.

Alternative vs. Bank Financing

• Players like CEMEX and ARGOZ are now well-positioned to capture the enormous informal-sector housing finance market, an example of the kind of disruptive entry that can force all players to reset the terms of an industry.

Alternative vs. Bank Financing

• Until now, banks have conceded the low-income housing market to others, but perhaps with creativity they could make a stronger bid.

Alternative vs. Bank Financing

• “If we changed our attitudes, unlearned our perceptions, and opened ourselves to learning how our customers lived and worked, we could build a whole new business model and carve out a market where it was thought there was no business for us,”

Alternative vs. Bank Financing

• says CEMEX’s Hector Ureta. Despite the apparent obstacles, perhaps it is time banks took his words to heart.

Alternative vs. Bank Financing

• We turn now to another product in which both financial and nonfinancial players compete for the low-income market. In this case, banks have recently become more energetic in their attempts to capture market share.

Remittances

• Poverty and opportunity have always motivated people to migrate from place to place. And, having found better livelihoods, many send money home.

Remittances

• In 2006, the International Fund for Agricultural Development estimated that close to $300 billion in remittances were sent to developing countries by 150 million migrants worldwide.

Remittances

• The World Bank believes that up to one-third of remittances may flow through informal channels. And these numbers are growing rapidly from year to year.

Remittances

• Needless to say, many financial-sector players seek to be the top choice of customers to facilitate these transfers.

Remittances

• Person-to-person remittance transfers are thought to be the second largest source of external capital to developing countries, after direct foreign investment.

Remittances

• As flows from the North to the South, remittances exceed official development assistance. In several countries they are greater than 10 percent of gross domestic product, and in a few extreme cases, such as El Salvador and Honduras, transfers approach and surpass 20 percent of GDP.

Remittances

• The upper tier of remittance senders often uses banks. The well-off send money from one bank account to another. As we move down the income pyramid, senders increasingly use money-transfer companies and informal mechanisms.

Remittances

• Although people often feel comfortable with informal senders who bring them news of the family back home, they might be surprised to learn that these are the most expensive and least secure ways to send money. A very sizable portion of the value sent informally is lost to fees, frauds, and mishaps.

Remittances

• The market opportunity related to remittances differs from that of insurance and housing because it is already a full-blown competitive arena. For insurance and housing, there is an opportunity to provide an entirely new service that clients cannot now obtain.

Remittances

• In contrast, the market for remittances is already hotly contested, and few transfers are prevented because senders can’t find a way to move the money.

Remittances

• The opportunity in remittances is to woo customers from one channel to another by offering cheaper, faster, and more convenient service. For banks, the opportunity includes attracting a new customer segment using remittances as an entry product.

Remittances

• In this contest, money-transfer organizations (MTOs) have a strongly dominant position. The clear market leader, Western Union, is in fact one of the most successful examples of private-sector engagement with inclusive finance we know.

Remittances

• Western Union earned approximately $1 billion in profits in 2006; a large part of this was due to its BOP remittance-sending customers.

Remittances

• Other top players include Eurogiro and MoneyGram. In addition, there are numerous smaller players, often specialized in a single remittance channel.

Remittances

• Money-transfer companies have made it a point to get close to customers, both physically and psychologically. They have made agents out of the proprietors of every corner grocery store in every immigrant neighborhood.

Remittances

• The shops that handle MTO transactions give immigrants a taste of home—a chance to converse with someone from the home country, to buy favorite foods, and to find out about local, immigrant community events.

Remittances

• Delgado Travel, a rapidly growing MTO, initially specialized in connecting people with their countries as a travel agency, and now does so also through phone cards and money transfers.

Remittances

• Delgado Travel and others like it offer a lifeline to home. No wonder many customers prefer it to the anonymity of most bank branches. But the amounts of money involved in remittances are simply too large for Delgado Travel’s managers to relax if they wish to maintain their market position.

New Entries

• Commercial banks have begun to make bids for the remittance market, and at the same time MTOs are becoming more regional. Previously sleepy remittance corridors have been invaded by competitors, causing prices to fall dramatically over the past decade.

New Entries

• Banks have not yet made significant inroads, but the trend is sharply upward. The Inter-American Dialogue notes that the percentage of Mexican immigrants using banks to transfer remittances from the United States rose from 2 to 6 percent between 2004 and 2006. It’s still a low percentage, but one that tripled in only two years.

New Entries

• One of the main questions concerning banks is the relationship between remittance sending and bank accounts. The MTOs work on a cash-to-cash basis, which allows people with no bank accounts to send and receive money.

New Entries

• The banks want these clients to open bank accounts and transfer funds from account to account, keeping the funds in the financial system as long as possible.

• They also hope to turn remittance customers into profitable long-term banking customers through cross-selling.

New Entries

• But the preference for cash among those sending remittances is persistent. Between the United States and Latin America, 70 to 80 percent of crossborder remittances were sent through money transfer intermediaries on a cashto- cash basis.

New Entries

• Even for immigrants with bank accounts, only 5 to 19 percent use their banks for sending money. Convenience factors, such as brand recognition, hours, locations, and speed of transfer, carry more weight.

New Entries

• Government policy makers also encourage remittances to move through banks, in the interests of “banking the unbanked,” but this admirable goal is made more difficult by the simultaneous emphasis on “know your customer,” fueled by fears of terrorism and illegal activity.

New Entries

• Undocumented workers avoid banks because of strict identification requirements. The U.S. Patriot Act actually made it easier for immigrants to open bank accounts by allowing identification issued by foreign consulates, but many immigrants still feel that it’s risky to give too much personal information to a bank.

New Entries

• A similar challenge occurs at the receiving end, where relatives back home may be unfamiliar with or distrustful of banks. With long histories of poor treatment behind them, customers may see banks as institutions for the rich. In Mexico only 33 percent of remittance recipients have bank accounts; in Central America only 22 percent.

New Entries

• Partnerships are especially critical in remittances: they link the sending and receiving institutions. Citibank has been active in establishing partnerships with recipient-side institutions, starting with Banco Solidario in Ecuador as a test case, and moving on to BRAC, in Bangladesh, among others.

New Entries

• Both these microfinance institutions have many branch outlets throughout their countries, making them attractive distributors of remittances. In the massive corridor between the United States and Mexico, Citibank customers can easily make account-to-account transfers with Banamex, Citi’s Mexican arm.

New Technology

• In the next Lecture

Summary

• Alternative vs. Bank Financing• Remittances