Stories Told at Breakup, Moose Factory 1983

Transcript of Stories Told at Breakup, Moose Factory 1983

Stories Told at Breakup, Moose Factory 1983

NICHOLAS N. SMITH

Ogdensburg, N. Y.

Since material concerning spring breakup at Moose Factory is lacking,

Dick Preston encouraged m e to present m y experiences there in 1983. In

the evening of 17 April 1983, the Rev. Jim Collins met m e at the Moosonee

train station and drove across the Moose River on the ice road, marked by

spruce trees, to Moose Factory Island as it was getting dark. The tempera

ture was -12°C. The Moose River, a major waterway flowing north into

James Bay, is tidal at Moose Factory, the early headquarters for the

Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), about 20 k m south of James Bay.

Traditionally, Cree hunters have returned to Moose Factory for

breakup, a unique spectacle. Everyone watches as huge ice cakes, many

weighing several tons, push their way north breaking through the river' s icy

epidermis with such force that the grinding, splashing, thrashing turbulence

is very audible to the watchers on shore, who compare the thunderous

sound to a freight train. Breakup is a holiday celebrated in both Cree and

HBC traditions.

Moose Factory, although a small island, is composed of several fenced

communities: the hospital, school, government, HBC, and Metis. The Cree

thought that they, too, should imitate the others and were beginning to erect

a barrier, although I wondered why it was necessary. The only place where

everyone seemed to be on common ground was the at unfenced Anglican

Church.

Breakup, like N e w Year's, is an event celebrated by all Moose Factory

residents. It is the time when snowmobiles are exchanged for canoes.

Some anxious hunters readied their canoes with goose-camp supplies and

transported them on sleds pulled by snowmobiles to high ground on the

mainland, where they were sheltered by a barrier of trees from the huge ice

cakes propelled by the powerful uncontrolled forces of river currents and

ocean tides. The large reservoir behind the new Otter Rapids dam remains frozen

several weeks longer than the powerful current formerly permitted the

Moose River to remain dormant. N o w breakup arrives a week or two later.

Old inhabitants were concerned that the large volume of water retained in

302 NICHOLAS N. SMITH

Figure 1. Ice piled up around St. Thomas Anglican Church, Moose Fac

tory, after breakup. Bishop Walton lantern slide collection, McMaster University, courtesy Richard Preston.

STORIES TOLD AT BREAKUP 303

the Otter Rapids reservoir would cause severe flooding when released. The

speed at which breakup progresses along the Moose River might differ

according to one's perspective — it is not a steady pace. Ice jams often

form, stalling the progress for a few hours or days. Contemporary Indians

65 k m up the Moosonee railway track advise by telephone those at Moose

Factory when breakup has reached them. Moose Factory residents then

plan for its arrival about two days later. While this might seem like a slow

pace, one suddenly caught out on the ice unaware of the wild action of

breakup a kilometer or two upstream would have quite a different opinion.

In former days Indians camped by the frozen river, watching and

waiting for the signs that the ice would soon break — signs not only from

the ice but from the migrating birds and changes in the flora. Those

camped on the bank hoped that breakup would occur during daylight hours.

The Moose River is tidal at Moose Factory. There are two layers of ice in

the river: a lower level formed on the brackish tidal water that moves up

and down with the tide, and a top level of ice which creates a substantial

crust on the fresh river water flowing to the sea. Water can be expected to

flood over the banks bringing huge, heavy ice cakes with it. Formerly the

HBC fired a cannon as a warning that breakup was about to arrive, but this

practice terminated about 1935.

Those who usually tented close to the water moved their tents to higher

ground and hoped they had anticipated the high water mark correctly. The

island seldom became completely inundated (McLeod 1978:18-19). The

flooding problem was solved at St. Thomas Church, located on the

waterfront, by drilling several large holes in the floor with removable

stoppers that are extracted before anticipated flooding to drain the water

from the church.

Social evening activities, notably whist, the favorite game of HBC

personnel, was popular for those awaiting breakup. The best card players

were well known; humorous fitting prizes were awarded such as a mouse

trap to a hunter of repute. The older people reminisced with stories

recalling not only past breakups, but other unique events. I was invited to

one such party. A n older person recalled a past breakup: word had come that breakup

was imminent. The people assembled at vantage points from which it

could be observed. Suddenly a man was seen way out on the ice trying to

reach the village. People shouted to the man to go back, but he could not

304 NICHOLAS N. SMITH

Figure 2. Ice at Moose Factory after breakup. Bishop Walton lantern slide collection, McMaster University, courtesy Richard Preston.

hear them over the turmoil of the crunching, breaking ice. No one dared

to attempt to help him — they just watched helplessly as breakup bore

down on him. Suddenly, as they watched, the unidentified man disap

peared in a flash as the ice opened up and then closed; he was never seen

again. The watchers shuddered, not wanting to believe the awful scene that

they had just witnessed, uncertain of the victim's identity.

A younger person provided a similar tale. Several years ago the

assembled watchers saw a man walking across the ice. He seemed to be

unaware that the breakup was coming faster than he could cross the ice.

The observers saw the man, but were afraid to go out on the ice to help

him. One man had the presence of mind to call the helicopter to go to

rescue him. The helicopter person asked who was going to pay for the

helicopter — they had to know before they started the flight. The Indian

replied that it was an emergency, they had to act fast, a man's life was at

stake, they would worry about the cost later. The helicopter arrived

moments before breakup. The man on the ice figured it was hopeless and

had given up until he saw the rope lowered from the helicopter. He

STORIES TOLD AT BREAKUP 305

grabbed the rope and was pulled up, saved!

Another popular theme of the dangers of winter travel on the frozen

Moose River concerned a hunter who was traveling on the ice highway

when he suddenly, without warning, fell through the ice. The river current

quickly carried the hunter downstream away from the hole. The victim was

in a dark cave between the two layers of ice, the lower level that moves

with the tide and the upper level above the normal high tide line strong

enough to support people, skidoos, and vehicles. W h e n the tide is low, the

river flows between the two levels. W h e n the lower level of ice rises on the

incoming tide, for a short time it is possible for the downed man to try to

break though a weak place in the upper crust, as he can brace and push

against the lower level of ice in his effort to force his way through a soft

spot in the upper crust. If he is not lucky enough to find an escape hole, he

will either be crushed to death between the two layers of ice or be

drowned.1

In northern Quebec, Fort Chimo (recently renamed Kuujjuaq) has

similar ice and tide conditions. There the Inuit look for breaks in the ice

that permit them to enter the ice caves to search for mussels. They find that

the ice caves are warmer than the surface. The search for the ocean

delicacies sometimes ends in disaster. Tides are strong, like those at

Moose Factory. It is considered unsafe for a single person to go into the

ice caves for one person must watch and warn of a changing tide while the

other harvests the mussels. The changing tides catching one by surprise

could cause a disaster (Dwyer 1997:27). There may be other northern

people living where ice caves form who harvest desirable seafood growing

in them, but if those at Moose Factory use underwater caverns as a source

of food, it was not mentioned to me.

The next story illustrates that life could be very hard, demanding

survival skills and capabilities from even young children. Charlton Island,

in James Bay about 100 k m from Moose Factory, is large enough to

provide much of the food needs for one family. Marguerite Moor's mother

was an invalid. They were the only family living on the island. When she

was 12 or 13 her father died. Her younger brother, Erlan Mack, who was

nine years old, I think, dug a grave in the frozen ground, buried his father,

and made a cross for the grave. Then he packed all their belongings, put

' Dick Preston confirmed the story about a man going through the ice at breakup. He thought, but could not confirm, that it was Sidney Archibald.

306 NICHOLAS N. SMITH

his mother on the sled, and took the family over the ice of James Bay to

Rupert's House, 80 k m away. These sad stories teach much about Moose Factory Indian life in win

ter. Children were taught to respect the unpredictable river conditions.

One does not need to have much imagination to shudder about the plight

of a poor fellow who has fallen into a dark cavern desperately searching for

a glimmer of light, the key to an opening through which he can extricate

himself before the incoming tide reaches its height. Although none of the

stories mention carrying a pole about 4 m long in case one does break

though the ice, stories like these encourage one to use this safety device, a

contemporary practice, when traveling on the ice. The pole will provide

support so that one can pull himself up on the surface. The last story is an

example of a nine-year-old boy who lacked formal education but was able

to take over in an emergency, performing all the tasks expected of a mature

self-sufficient adult. Although Cree youth appear to be less mature than

comparable children of our life style, I have seen several instances when

Cree youth, reacting to some form of body language, quickly responded to

an emergency situation by performing as adults. I doubt that our more

sophisticated children would respond to such crises so well. Instruction

might not be formal, but it is obvious that Cree youth have been trained to

observe adult behavior and to imitate it successfully when a crisis demands

their help. Some Mistassini Cree have told m e that life is so hard they want

their children to enjoy their childhood as long as possible.

The following humorous story was told by an older w o m a n who

probably heard it from her grandmother. The Indians were invited to a tea

at the factor's house. They were curious to see the factor's house, but felt

quite insecure about proper etiquette. W h e n the factor's wife took a cup of

tea and cake, they all took a cup of tea and cake; when she sipped, all the

Indians sipped; when she nibbled, all the Indians nibbled. One of the

Indians realized what was happening and got to laughing so hard that she

spilt her tea on the factor's rug!

The factor was considered a superior person with a much different life

style than the Cree. It would be unusual for a Cree w o m a n to have direct

contact with the factor or his wife. The trading and buying was usually

done by the men. For the Cree the word rug represents an entirely different

lifestyle from their own, making it a rather fearsome episode.

Willie Chilton was born at Moose Factory and had lived there all his

STORIES TOLD AT BREAKUP 307

more than 70 years. H e provided some background from "the good old

days". Willie started working for the HBC when he was 15, joining a crew

exchanging supplies for furs at inland posts such as Mistassini:

There were 75 portages in the first 100 miles. The longest portage was three miles. If you couldn't carry 200 pounds, you got no pay. Our food was flour, tea, and salt pork. There was no need for a tent when you were traveling. W e slept on grass and spruce boughs on the ground. If you couldn't do it, you could learn to do it.

Willie's story may sound to us as an example of a hard, even an

abusive lifestyle. However, for the young men of his day, who knew the

hardships of bush life, it was a way offering security — there was no

problem finding young men glad to do the work under those conditions.

Willie had difficulty accepting the contemporary youth situation at Moose

Factory. School graduates made little attempt to find work. Some went

west in quest of the "idealistic Indian life", learning drumming; when they

returned to Moose Factory they drummed all night, keeping Willie awake,

and then they slept all day avoiding work. This was not traditional Cree

behavior as Willie knew it. Although Willie had a successful record of a

life of hard work at Moose Factory, I discovered at the whist party that he

could not read, write or do simple arithmetic.

Willie's wife once went to southern Ontario to see some friends who

showed her that part of the province. They stopped at a motel in London,

Ontario. The registrar said identification was needed — a driver's license

would do. She replied that she didn't have a driver's license, but offered

her hunting license; it was not accepted. Driver's licenses are not required

in Moose Factory. Y o u can drive around the island in the summer, and in

winter you can drive as far as Moosonee, but if you want to go further and

take your car with you, the vehicle must be put on the Polar Bear Express

at Moosonee and will require license plates. Mrs. Chilton's version of the

story did not hint that she was aware that her right to rent a motel room was

abused. Fred Moor had traveled on both James Bay and Hudson Bay and the

major rivers flowing into them; in 1983 Fred had the reputation of know

ing the river channels better than anyone else. Each summer he was hired

by the local tugboat company, owner of the tugs Nelson River and

Churchill River. Fred noted that at Fort George one of the former main

channels n o w can hardly be navigated by a canoe, and that the mud flats

are gradually growing. The wind blows sand and silt from west to east; the

308 NICHOLAS N. SMITH

flats have become more solid and support trees where trees never grew

before.2

Another successful Cree was Jack Wynd. He had moved to Moosonee

and then Cochrane. It was said that he owned commercial property in both

places and was a multimillionaire. He retired at 57 and recently returned

to Moose Factory where he grew up. Both he and Moose Factory had

changed considerably. He found it difficult to settle into the laid-back

Moose Factory lifestyle of the retired, finding it rather boring. He wanted

to return to work.

In 1983 life in the north was not easy for the non-Indian community.

There were many adjustments for non-Indians that some found it difficult

to make. There were stories that the Albany factor was "bushed" and

needed to get away. He planned to skidoo the 125 km to Moose Factory —

he had to get away. He traveled for some time and then realized that he

was lost. He was not prepared for a long journey, having taken few

matches and little food or water. He soon finished all his food and water

and used all his matches. He found a beaver house and stopped by it,

hoping to get warm from heat escaping from the lodge and perhaps to kill

a beaver for food. He heard the beavers inside, but it seemed that they

knew when he was asleep and only came out then. When he didn't turn up

at the time expected, land and air search parties were notified to look for

him. They found no trace of him and finally gave up the search. A few

days later the pilot of an unscheduled plane, off course, spotted a bit of

orange on the ground. He landed on a nearby lake and found the factor

alive, but very weak. A little longer and he would have been dead.

The narrator added that if a person gets really cold, it can effect him —

he can go crazy. When your feet get cold, the cold will travel up through

your body. Exhaustion will set in and then you will get dizzy spells.

Many Indians love to tell stories about whites who ignore the basics of

survival that Indians learn from infancy. Indians also enjoy berating neigh

boring bands. When the conversation turned to wild meat, such as wildcat,

porcupine and woodchuck, a woman added that she knew a Mistassini man

who cooked skunks and liked them.

The story of Canon Redfern Loutitt illustrates a life subjected to great

changes and the difficulties of adjustment. Redfern's father was a respec-

2 Sometimes hunters put willow branches in the ground as markers and they take root and grow.

STORIES TOLD AT BREAKUP 309

ted leader who worked for the HBC in furs and as a translator. His school

experience consisted of a six-week course taught by a priest one summer.

Like many of the Indians who worked for the Company, he copied some of

their ways. H e had upgraded his home from a tent to a house. He was a

devout Christian and wanted one of his children to become a priest. When

Redfern was nine years old, the bishop made his regular annual visit to

Moose Factory. W h e n the bishop arrived, Redfern's father presented the

subject to him; the outcome was that when the bishop was preparing to

leave, the boy was put in the bishop's canoe. The reluctant Redfern had to

be tied in, with blankets placed around him to keep him warm. The family

could hear the boy still crying after the canoe was out of sight. His

introduction to the white man's culture had begun.

Redfern attended Chapleau residential school, and was graduated from

Chapleau high school.3 H e then went to college in Toronto to study for the

ministry, living with a clergyman who would not have him in his home, but

in a lean-to constructed on the back of his house. At college he was the

track star of his day; the spectators cheered him on and newspapers

highlighted his feats. At Christmas vacation his friends left for the

holidays; he remained in Toronto. After attending church all the happy

families left ignoring the lonely young man w h o m they had cheered at the

track not long before. H e spent the day walking the streets of his neighbor

hood seeing many high-spirited, happy people going in and out of

decorated homes, all completely ignored the lonely man so far from home.

In 1941 Redfern was ordained at St. John's Church, Chapleau. He

returned to Moose Factory as an Anglican priest to work among his Cree

people. His younger sister did not know him and he did not know her.

They still don't really know each other as brother and sister. The lonely

Toronto years lacked experience in family relations. He looked forward to

coming home. His training was entirely different from that given his peers;

he was no longer considered one of them. Although the factor now invited

Redfern into his house, this honor was not bestowed on Redfern's wife,

Agnes, a local Moose Factory girl — Cree women were not permitted in

the factor's store or residence. She was hired by the HBC to cut, split, and

carry wood to the door where she was met by a servant of the Company

3 A brief synopsis of Loutitt's Chapleau years shows that the oral stories told about Redfern were essentially correct except that an unnamed missionary rather than the bishop, took him to the Chapleau residential school (Corston 1997:6).

310 NICHOLAS N. SMITH

who took the firewood inside. O n very cold days she was permitted to

come just inside the door and lean with her back to it.

Redfern's years in Toronto transformed him into one of those from the

other world, a person who, although born at Moose Factory of Cree parents,

was not completely accepted as a Cree on his return to his hometown. In

1983 he was officially retired, but there have been few Sundays that it has

been not necessary for him to attend to priestly duties. H e remains a

faithful shepherd to the Cree who love him as their priest.

The millionaire and the priest had become successful in another

culture, but forgot or lacked the training needed for survival as hunters and

trappers, so on their return to Moose Factory were not accepted as "real

Cree". In the 1970s Mistassini Cree who practiced the non-traditional

Indian occupations were given houses on the "white side" near the priest's

and HBC employees' residences.

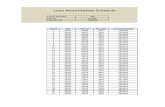

The exact moment of breakup at Moose Factory is recorded when a

white and red striped post set in an assigned spot on the ice is knocked

down by the advancing ice and water. Old timers with many years of

experience with Moose Factory breakups attempt to use their knowledge

of nature to predict the exact time the striped poled will be knocked down.

All are invited to predict the time of the downing of the pole and win a

substantial amount of money. The breakup holiday atmosphere at Moose

Factory brings together many of the loose Cree community. It is an

opportunity to meet numerous friends who one normally sees infrequently.

I'm sure the stories told — stories revealing a people with a great

knowledge of their surroundings and the adjustment from a beaver

economy in the 20th century — were not just to entertain me, but were a regular part of the breakup festivities.

REFERENCES

Corston, Tom. 1997. St. John's, Chapleau, hosts homecoming. The Northland 54(l):6-7'. Dwyer, Augusta. 1997. Mussel bound: when the tide goes out, residents of a northern

Quebec village tunnel through the sea ice for a hidden feast. Canadian Geographic 117(6):26—30.

McLeod, Herbert F. 1978. Memories of fur trading days in Moose Factory and vicinity. Kapuskasing: Marc Plouffe.