Sound Objects

description

Transcript of Sound Objects

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

Los Angeles

Sound Objects: Speculative Perspectives

A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree

Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology

By

Mandy Suzanne Wong

2012

© Copyright by

Mandy Suzanne Wong

2012

ii

The dissertation of Mandy Suzanne Wong is approved.

__________________________________ Joanna Demers

__________________________________ Nina Eidsheim

__________________________________ Mitchell Morris

__________________________________ Roger Savage __________________________________ Robert Fink, Committee Chair

University of California, Los Angeles

2012

iii

This work is dedicated to Joanna Demers, my dear friend and mentor, who saw this

project through from the beginning all the way to the bittersweet end.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Sound Objects: Introduction as Glossary 1 Chapter 1. Sound Objects in Music 19 Chapter 2. Sound Object as Metaphor: Reification and Ideology 59 Chapter 3. Convergences: Sound Objects, Aesthetic Autonomy, Musical Works 97 Chapter 4. Sound Object Analysis 122 Chapter 5. Subjectivity, Discourse, and Truth in Sound Object Analysis 145 Chapter 6. Listening, Dialogue, and Embodiment in EDM: A Case Study in Sound Object Analysis 165 Chapter 7. Object, Sound, Materialism 185 Bibliography 211

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My tremendous thanks to the entire faculty of the UCLA Musicology Department,

as to its tireless Student Affairs Officer, Barbara Van Nostrand, for welcoming me into

your midst at an incredibly late stage in my graduate student career. By going out on a

limb on my behalf, you enabled my thinking to develop in ways I never would have

imagined possible.

I am especially grateful to Bob Fink, not just for lending his invaluable expertise

and support to this project, but also for encouraging me to let my thoughts take me where

they would, to make mistakes and try to work through them, and to probe the most

awkward conclusions to their darkest depths. The intellectual value – and, for me, the

sheer joy – of working with an advisor who shares my deep regard for experimental

music cannot be overstated. Bob also deserves tremendous thanks for rising to (and well

above) the occasion when his position as Chair summoned more energy than we could

ever have imagined.

I’d also like to thank Mitchell Morris for our quarter-long battle with Adorno, as

with other philosophical and psychoanalytic ideas. And the dissertation could not have

been what it is without the input of Roger Savage, whose unique philosophical

perspective shaped my earliest work on sound, and who was the first to ask me this vital

question: Who says sound objects aren’t real?

I’d like to extend special thanks to Nina Eidsheim, who raised the possibility of

sound object analysis, served unendingly as my sounding board, and permitted me to

watch as her own unique, ground-breaking ideas on the materiality of music began to

vi

take shape. Your friendship and guidance pulled me through the most difficult twists and

turns that my academic life has taken.

This dissertation would not have been possible without Joanna Demers, who first

introduced me to Schaefferian thought, to philosophy in general, and to the notion that

musicology doesn’t have to be what it is. Your work, your insight, and most of all your

friendship continues to give me so much hope.

Finally I’d like to thank my family: Mom, Dad, Mark, and Heather, who enable

me to keep after this wild dream I have, of a life spent in play with ideas.

This dissertation was supported by a number of fellowships, including a UCLA-

Mellon Fellowship of Distinction and a UCLA Dissertation Year Fellowship, which

made it possible for me to work through the tangle of questions engendered by a mere

two words.

vii

VITA

May 24, 1979 Born, Bermuda 2001 B.A., Music Wellesley College Wellesley, Massachusetts 2003 M.M., Piano Performance New England Conservatory of Music Boston, Massachusetts 2005 Graduate Diploma, Piano Performance New England Conservatory of Music Boston, Massachusetts 2008 M.A. Qualification, Music History and Literature University of Southern California Los Angeles, California 2009 Teaching Assistant University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, California

PUBLICATIONS AND PRESENTATIONS Eidsheim, Nina and Mandy Suzanne Wong (forthcoming 2012). Corporeal Archaeology:

Embodied Memory and Improvisation in Corregidora and Contemporary Music. In Sounding the Body: Improvisation, Representation, and Subjectivity, ed. by Gillian Siddall and Ellen Waterman, Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

___________________ (2011). Frances Dyson’s Sounding New Media. Organised Sound

16(3): 284-286. Wong, Mandy Suzanne (forthcoming 2012). Sound Art. Oxford Bibliographies Online,

New York: Oxford University Press. ___________________ (forthcoming 2012). Sound Art, Sound Sculpture, Sound

Installation, Christian Marclay, Yann Novak, Steve Roden, Mem1, Charlemagne Palestine, Max Neuhaus, Henry Gwiazda, Matmos, Phill Niblock, and Trimpin. In The New Grove Dictionary of American Music, New York: Oxford University Press.

viii

___________________ (forthcoming 2012). Hegel’s Being-Fluid in Corregidora, Blues Song, and (Post)Black Aesthetics. Evental Aesthetics, 1(1).

___________________ (forthcoming 2012). Listening to EDM: Sound Object Analysis

and Vital Materialism. Volume! The French Journal of Popular Music Studies. ___________________ (forthcoming 2012). Sound Objects in Musical Discourse. Paper

to be presented at the meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association, Providence, Rhode Island.

___________________ (2011). Hume and the Problems of Automobile Aesthetics. Paper

presented at the meeting of the American Society for Aesthetics, Tampa, Florida. ___________________ (2010). Hegel’s Ontology of Musical Sound. Paper presented at

the meeting of the American Society for Aesthetics, Victoria, British Columbia. ___________________ (2010). Sound Object Analysis. Paper presented at Beyond the

Centres: A Conference on Avant-garde Music and Aesthetics, Thessaloniki, Greece.

___________________ (2009). Action, Composition – Morton Feldman and Physicality.

Paper presented at the meeting of the College Music Society, Pacific Chapter, Northridge, California.

___________________ (2009). An Argument for Reduced Listening as a Function of

Memory. Paper presented at the Musicology Graduate Student Conference, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

___________________ (2009). Sonic Materialism. Paper presented at the Hawaii

International Conference for the Arts and Humanities, Honolulu, Hawaii.

ix

ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION

Sound Objects: Speculative Perspectives

by

Mandy Suzanne Wong

Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology

University of California, Los Angeles, 2012

Professor Robert Fink, Chair

The terminology that listeners, composers, performers, and scholars use to

describe music and sound affects their functions and ontologies. Terminology alone can

transform music and sound from experiences to things, from encounters to commodities,

from interaction to domination. In other words, terminology influences the qualities and

forms of our attitudes and responses toward music. My dissertation is concerned with one

instance of influential terminology: the term “sound object,” a cornerstone of electronic-

music discourse. Conceptualizing “sound objects” as the atomistic “elements” of music

implies that music possesses a tactile, embodied way of being. Sound objects therefore

elicit inquiries from several perspectives. I consider sound objects from nominalistic,

ontological, epistemological, music-analytical, and historical points of view, all of which

differ considerably from one another.

x

The “sound object” first appeared in the 1950s as Pierre Schaeffer’s

conceptualization of music’s “raw element,” which he believed listeners could learn to

hear. Post-Schaeffer, the sound object acquired several definitions and exists today in a

variety of contexts. A sound object may be a sampled or recontextualized sound, as the

author Chris Cutler describes. Alternately, as in the electronic music of Curtis Roads, a

sound object is simply a sonic unit, comprising anything from a noise to a melodic

segment. The sound object is also a musical genre for ringtone composers such as

Antoine Schmitt. Elsewhere, it is a sonic evocation of physical gesture, as in Rolf Inge

Godøy’s research on motor-mimetic music cognition.

My objectives are to assess the term “sound object’s” potential as an increasingly

prevalent aesthetic category, and to theorize and critique the sound object as a

materialistic manner of description too often taken at face value. To be sure, the “sound-

as-thing” may serve as a basic analytical category that may foreground the importance of

subjective listening to analysis. But the tactility implied by the word “object” may

misrepresent sonic and musical experiences as tangible and stable, despite their actual

temporality. That said, the word “object” may elicit reflections on music’s relationships

to embodiment, and critique habitual assumptions concerning musical experience and

music’s ability to communicate truth.

1

Sound Objects:

Introduction as Glossary

Public Sound Object:

A sound file on a public server accessible via Internet to home-computer users.

The goal is musical performance globally networked. Users draw from the library of

sound objects (shown in the cylindrical canister above), and join fellow users around the

world in inserting the objects into the collaborative musical improvisation already going

on in cyberspace.1

Experimedia | Sound Objects:

Recording label and online distribution company for experimental music,

established in Kent, Ohio in 2000. A sound object is also any musical selection available

at Experimedia.

Flash Sound Object:

A segment of computer code that tells a computer to access an archived, digitized

sound in the multimedia software Flash. According to an instructional site, “[a] sound

object is not the actual sound used in the Flash file; it is simply a reference to the sound

resources [available on the computer]...Think of it as a translator between a sound’s

1 Alvaro Barbosa, "Public Sound Objects: A Shared Environment for Networked Music Practice on the Web," Organised Sound 10, no. 3 (2005).

2

properties – such as volume, balance, or duration – and the actual sound in the

[computer’s digital] library.”2

Untitled Sound Objects:

Kinetic sound sculptures by Pe Lang and Zimoun (2008): hundreds of tiny motors

hung from white walls.3

Unidentified Sound Object:

Discovered in 2002 by film theorist Barbara Flueckiger in several Hollywood

films, usually from sci-fi and horror genres.

[A] chief characteristic of the USO is that it has been severed from any

connection to a source. In the case of the USO the source is neither visible

on screen, nor may it be inferred from the context. In addition, spectators

are denied any recognition cues, so that in general the level of ambiguity is

not reduced...The USO can be understood as an open, undetermined sign

whose vagueness triggers both vulnerability and tense curiosity...The

ambiguous sound object poses a question...4

2 Instructional site for programming Flash. http://www.peachpit.com/articles/article.aspx?p=463006. Accessed 29 November, 2010.

3 http://www.pelang.ch/works.html

4 Barbara Flueckiger, "The Unidentified Sound Object" (paper presented at the ASF Conference, Paris, 2002), 1-4.

3

Like many other theorists, Flueckiger credits Pierre Schaeffer with coining the

term sound object. Schaeffer was a composer, a theorist, and the inventor of musique

concrète. Thus, the term sound object first came about in music, rising with the dawn of

electronic music. Since then, the term has found its way into countless other contexts.

Musical Sound Objects:

Pierre Schaeffer, 1950s: A sound object is a sound “in itself,” the essence of

sound and the universal foundation of all auditory experiences. One arrives at the sound

object by means of a technique that Schaeffer called reduced listening: a mode of hearing

in which one ignores the origins and potential meanings of a sound. For Schaeffer, then, a

sound object is an aestheticized sound to which only its intrinsic qualities are relevant. At

the same time, it is the “raw element” of music, which Schaeffer believed listeners could

learn to hear.5

After Schaeffer’s death in 1995, composers and analysts of electronic music took

up his terminology, in many cases altering its definition. Today, sound object has

multiple definitions, and is used in a variety of musical-discursive contexts.

Chris Cutler, electroacoustic composer and musicologist, 2000: A sampled or

recontextualized sound is a “found (or stolen) object,” hence a sound object.6 The same

reasoning applies in Alvaro Barbosa’s Public Sound Objects, described above.

5 Pierre Schaeffer, Solfège De L'objet Sonore, trans. Livia Bellagamba (Paris: Institut National de l'Audiovisuel, 1998), 65.

6 Chris Cutler, "Plunderphonics," in Music, Electronic Media and Culture, ed. Simon Emmerson (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2000), 97.

4

Rolf Inge Godøy, researcher of motor-mimetic music cognition, 2003: A gestural-

sonorous object is a sonic evocation of physical gesture.7

Curtis Roads, microsound composer and theorist, 2004: A sound object is an

“elementary unit of composition” meant to replace the musical note: anything from a

noise to a melodic segment, but with a specific duration (“from about 100ms to several

seconds”).8

Antoine Schmitt, ringtone composer, 2004: A sound object is a composition for

mobile phone, and the name of Schmitt’s recording label dedicated to the ringtone genre:

Sonic()bject.

Sound Object – A Term in Electronic-Music Discourse

Though it is doubtlessly telling that the term sound object has grown from a

musical term to an interdisciplinary phenomenon, permeating a variety of enterprises

from film scholarship to computer programming, sound objects in music are the focus of

this dissertation. Music’s mode of being depends to a significant extent on what we call it

– on the terminology that listeners, composers, performers, and scholars use to describe

it. With its undeniable influence on our attitudes towards phenomena in general,

terminology alone may transform music and sound from experiences to things – from 7 Rolf Inge Godøy, "Gestural-Sonorous Objects: Embodied Extensions of Schaeffer's Conceptual Apparatus," Organised Sound 11, no. 2 (2006), ———, "Music Theory by Sonic Objects," in Polychrome Portraits: Pierre Schaeffer, ed. Évelyne Gayou and translated by François Couture (Paris: Institut National de l'Audiovisuel, 2009), ———, "Images of Sonic Objects," Organised Sound 15, no. 1 (2010), ———, "Gestural Affordances of Musical Sound," in Musical Gestures: Sound, Movement, and Meaning, ed. Rolf Inge Godøy and Marc Leman (New York: Routledge, 2010).

8 Curtis Roads, Microsound (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004), 16-17.

5

encounters to commodities, from interactions to forms of domination. The present inquiry

concerns the influence of one term, sound object, on electronic-music discourse.

My objectives are to assess the sound object’s potential as an increasingly

prevalent aesthetic category, and to theorize the sound object as a materialistic manner of

description too often taken at face value. To be sure, the sound-as-object may serve as a

basic analytical category that, unlike the musical note, may address electronic music on

its own terms and account for the importance of subjective listening to analysis. But the

fixity implied by the word object may misrepresent sonic and musical experiences as

inert and passive, despite their actual temporality and activity.

That said, the word object may elicit reflections on music’s relationships to

embodiment and truth. Moreover, terms like sound object, sound wave, musical note,

musical work, and their underlying premises, may shed light on the ideologies and

epistemologies specific to the cultural eras in which the terms arose. In the following

chapters, I speculate on how and why sound object arose where and when it did, in the

evening of the twentieth century but at the dawn of electronic music, and suggest how the

sound object may have stemmed from existing philosophical preoccupations. I

demonstrate that, as a catalyst of change in prevailing conceptions leading to new

creative and analytical perspectives, the term sound object summons philosophical

questions to the forefront of a musicological inquiry, and illuminates new avenues of

critique for traditional Western musicological and aesthetic presuppositions.

The most basic premise of this endeavor – the notion that terminology for sound

affects how it is treated and how it is understood as functioning artistically and

6

discursively, i.e. in several kinds of actual, practical experience – amounts to the

suggestion that naming and experiencing are two diverse ways of approaching what we

may call “experience.” Philosophically, this suggestion highlights a difference between

nominalism on one side, and phenomenology and hermeneutics on the other.9 The power

of nominalism, or even simply of naming, is a primary issue at stake and under inquiry

here. Where suggestions may arise (for instance in Pierre Schaeffer’s work) of

nominalism masquerading as ontology, I attempt to evaluate such implications. Although,

due to the nature of speculation, this project may seem at times to be itself a claim for a

nominalistic ontology, this claim is precisely what is under investigation.

Speculative Perspectives

A word on the title of my project. As we’ll see, a sound object is itself a

perspective on sound. In its multitudinous definitions, the term sound object connotes an

array of listening standpoints: myriad points of view from which to hear and characterize

sound. Additionally, because it is multiplicity itself, because it stands for polymorphous

aural outlooks, the term sound object invites consideration from numerous theoretical

perspectives. In other words, because a sound object is a sound-as-heard, a relationship

between a listening subject and a sonic phenomenon, it references several other

relationships which (I believe, as did Pierre Schaeffer) no single academic discipline is

9 It is possible to theorize this gap as the chasm between philosophical traditions: analytic and continental. However, I hesitate to qualify it as such in this project, because recent work suggests that this chasm may not be as wide as it has thus far appears, if it even exists at all. The issue of its breadth or existence are far beyond the scope of this inquiry. But the reader may refer to: Dascal, Marcelo (2001). “How Rational Can a Polemic Across the Analytic -Continental 'Divide' Be?” International Journal of Philosophical Studies 9 (3):313 – 339. See also Simons, Peter (2001). “Whose Fault? The Origins and Evitability of the Analytic-Continental Rift.” International Journal of Philosophical Studies 9 (3):295 – 311.

7

equipped to address on its own. Therefore I try to listen as a music historian, a music

theorist, and a philosopher, and to integrate these perspectives in a flexible,

interdisciplinary outlook. I attempt to move fluidly between various philosophical points

of view, some of them drawn from opposing philosophical traditions.

Altogether, my multifarious perspective is speculative. Based primarily in

thought, speculation embraces paradox. Speculative thought begins with the

equivocalness latent in seemingly innocuous words. This stipulation comes from GWF

Hegel, whose Science of Logic theorizes and proceeds according to speculative

principles. As Hegel says (albeit without any awareness of linguistics, which had yet to

become a veritable science) it is a joy to find

words [that] even possess the further peculiarity of having not only

different but opposite meanings so that one cannot fail to recognize a

speculative spirit of the language in them: it can delight a thinker to come

across such words and to find the union of opposites naïvely shown in the

dictionary as one word with opposite meanings...10

The term sound object affords just this unique opportunity. On the one hand, the

term is a metaphor, describing electronic composers’ treatment of sounds as though they

were material objects. Microsound composer Curtis Roads uses sound objects to

conceptualize short sounds that he “stitches together” into longer sounds via granular-

10 Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Science of Logic, trans. A.V. Miller (Amherst, New York: Humanity Books, 1969), 32.

8

synthesis techniques.11 Drew Daniel of Matmos, a duo which creates electronic dance

music using “everyday” sound sources (water droplets, coughs, glassware, and more) also

describes his compositions as constructions built from sound objects. He enjoys working

with sound as “a material thing with some stability...in its own space.” For him, “a

composer is someone who puts things together.”12 Since much electronic music does not

require “live” performers, the sound object perhaps evinces an underlying desire for

corporeality where none is readily apparent. Perhaps electronic composers’ mobilization

of the term sound object suggests an appeal to a metaphor based in the familiar, the

material, for help in conceptualizing near-indescribable experiences.

There are instances in which sound objects may be actual, non-metaphorical

entities. Nina Eidsheim’s work investigates the tactility of sound, music’s consequent

appeal to all the physical senses, and the ramifications of music’s ability to act upon our

bodies. Adding an epistemological component to Eidsheim’s argument, I inquire as to

how sounds may acquire the characteristics and capabilities of material bodies, and how

listeners and artists come to expect them to do so (Chapters 6 and 7).

The allure and precariousness of the term sound object stem not only from its

contradictory definitions but also from its invocation of terms that quotidian parlance

“naïvely” takes for granted: terms like sound, object, music, listening. Speculative

examination of sound objects reveals these other, “basic” terms to be self-contradictory

as well – or at least to be subject to contradictory expectations in musical, philosophical,

11 Roads, Microsound, 87.

12 Personal communication with Drew Daniel, April 2010.

9

and quotidian discourses. Moreover, although the term sound object facilitates analytical

descriptions of certain sonic phenomena and creative processes, the term runs the risk of

oversimplifying the multifaceted relationships between listeners, music, and sounds into

subject-object relationships. We are driven to re-inquire as to what our most basic

relationships with sounds and music really are.

Other Perspectives

Since the aim of this project is to reflect on how the term sound object is used in

musical discourse, I often rely on the exact words of composers and authors who have

used the term, and of philosophers who have investigated related issues. Having arisen

with Schaeffer’s phonograph-based musique concrète, the term sound object pertains

primarily to the creation and audition of electronic music. To date, references to sound

objects are more prevalent in composerly reflections than in scholarly analyses. Few

extant writings confront the sound object with analytical rigor. Schaeffer and Roads are

among the few authors to even attempt formal definitions of the term. For Schaeffer, a

sound object is the result of reduced listening, in which one consciously ignores any

associations implied by a given sound. He cites as inspiration Edmund Husserl’s

phenomenological reduction, which brackets the sensible world out of consideration with

the hope of seeing beyond it to the essence of things. For Roads, the sound object has

similar metaphysical aspirations. Roads’ sound object is a musical, structural unit of very

short duration, made of smaller but still materialistic “sound particles.” Roads follows

Edgard Varèse and Iannis Xenakis, who at the dawn of the nuclear age forged a

10

metaphoric connection between discrete sounds and atomic particles. Microsound

composers like Roads later took this connection to a logical extreme in their search for

the irreducible unit of sound. Microsound is an electronic genre typically confined to

short, quiet sounds, sonic clicks and pops. As Mitchell Whitelaw observes, “A click is, in

a sense, the tiniest sound imaginable – so why not call it a sound particle, a sonic

atom?”13 This metaphor shapes not only microsound’s aesthetic, but also its approach to

composition as a kind of “molecular synthesis” of sound objects from sound particles.

Whitelaw is among the few musicologists to openly question whether objectified

sound might just be an illusion, thereby hinting at the contradictions posed by the term

sound object. Whitelaw observes that “through the intermediary of sound, digital data is

figured [in microsound] as exactly the thing that it is not: matter.”14 Thus the sound-

object metaphor becomes a “distraction from what is most interesting” about microsound:

the interactions of “data systems with sound, embodied experience and culture.”15

Carolyn Abbate and Patricia Carpenter join in Whitelaw’s objection to the

disembodiment, the independence from human acts and bodies, implied by such notions

as sonic and musical “objects.”16 Brian Kane, Simon Emmerson, and Luke Windsor offer

similar criticisms of Schaefferian theory: reduced listening and sound objects suggest an

13 Mitchell Whitelaw, "Sound Particles and Microsonic Materialism," Contemporary Music Review 22, no. 4 (2003): 37.

14 Ibid.: 93.

15 Ibid.: 99.

16 Carolyn Abbate, "Debussy's Phantom Sounds," Cambridge Opera Journal 10, no. 1 (1998), Patricia Carpenter, "The Musical Object," Current Musicology, no. 5 (1967).

11

impossible immunity to our historical and cultural surroundings.17 In addition, Joanna

Demers’ work on intellectual property warns that to objectify sound is also to commodify

it.18 As Amy Wlodarski suggests, the practice of sampling runs the risk of reifying and

commodifying entire socio-historical eras and their participants, and of “suturing” them

into contemporary contexts without enough thought to the implications of such

transcontextual moves.19

Yet theories of listening are more likely to include discussions of sound objects

than music histories or analyses, probably because, as Schaeffer claims, sound objects

may come to light only when we listen in certain ways. To my knowledge, my work and

Godøy’s offer the only applications of sound objects to listening as it pertains to music

analysis.20 Emmerson’s monographs and collections, along with essays by Ambrose

Field, Simon Waters, Luke Windsor, and Eric Clarke critique the assumption, basic to the

existence of sound objects, that it is possible to listen in a variety of modes which may or

17 Brian Kane, "L'objet Sonore Maintenant: Pierre Schaeffer, Sound Objects and the Phenomenological Reduction," Organised Sound 12, no. 1 (2007), Simon Emmerson, Living Electronic Music (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), Luke Windsor, "Through and around the Acousmatic: The Interpretation of Electroacoustic Sounds," in Music, Electronic Media and Culture ed. Simon Emmerson (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2000).

18 Joanna Demers, Steal This Music (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2006).

19 Amy Lynn Wlodarski, "The Testimonial Aesthetics of Different Trains," Journal of the Americal Musicological Society 63, no. 1 (2010).

20 Rolf Inge Godøy, "Motor-Mimetic Music Cognition," Leonardo 36, no. 4 (2003), Godøy, "Gestural-Sonorous Objects: Embodied Extensions of Schaeffer's Conceptual Apparatus.", ———, "Music Theory by Sonic Objects.", ———, "Images of Sonic Objects.", ———, "Gestural Affordances of Musical Sound.", Rolf Inge Godøy and Marc Leman, eds., Musical Gestures: Sound, Movement, and Meaning (New York: Routledge,2010).

12

may not ascribe meaning to sounds.21 Meanwhile, Demers’ theory of aesthetic listening

implements precisely the kind of listening that Emmerson decries: aesthetic listening

permits intermittent attention in a variety of ways, only some of which may yield sound

objects.22 We may situate Demers and Emmerson alongside critiques of other modes of

listening, for instance critical thought by Rose Rosengard Subotnik, Roger Savage,

Andrew Dell’Antonio and others on the merits of “structural listening,” which attends

primarily to form as opposed to style, gesture, or sound.23

“Ancestors” of the term sound object – pervasive heuristic categories such as

musical work – have received a great deal of philosophical attention. Efforts to negotiate

the controversies of the work-concept in the history of Western music include those of

Lydia Goehr, Roman Ingarden, Stephen Davies, Julian Dodd and others.24 But

philosophical investigations of sound object itself are scant. Casey O’Callaghan discusses 21 Simon Emmerson, ed. Music, Electronic Media, and Culture (Aldershot: Ashgate,2000), ———, "Living Presence," in Living Electronic Music (Hampshire, England: Ashgate, 2007), Simon Emmerson and Denis Smalley, "Electro-Acoustic Music.", Ambrose Field, "Simulation and Reality: The New Sonic Objects," in Music, Electronic Media and Culture, ed. Simon Emmerson (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2000), Simon Waters, "Beyond the Acousmatic: Hybrid Tendencies in Electroacoustic Music," in Music, Electronic Media and Culture, ed. Simon Emmerson (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2000), Windsor, "Through and around the Acousmatic: The Interpretation of Electroacoustic Sounds.", Eric F. Clarke, Ways of Listening: An Ecological Approach to the Perception of Musical Meaning (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

22 Joanna Demers, Listening through the Noise: The Aesthetics of Experimental Electronic Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

23 Rose Rosengard Subotnik, Deconstructive Variations: Music and Reason in Western Society (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), Andrew Dell'Antonio, ed. Beyond Structural Listening?: Postmodern Modes of Hearing (Berkeley: University of California Press,2004), Roger W. H. Savage, Hermeneutics and Music Criticism (New York: Routledge, 2010).

24 Lydia Goehr, The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), Roman Ingarden, The Work of Music and the Problem of Its Identity, ed. Jean G. Harrell, trans. Adam Czerniawski (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1986), Julian Dodd, Works of Music: An Essay in Ontology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

13

“auditory objects,” but in the context of hearing in general, not specifically in music.25

Demers enlists the sound object in Listening Through the Noise, her comprehensive

aesthetics of electronic music.26 Kane offers a brilliant critique of Schaefferian theory

through the lenses of Roger Scruton, Stanley Cavell, and Ludwig Wittgenstein.27

Schaeffer himself took inspiration from Husserl’s phenomenology, which warrants

comparison with other phenomenological theories of listening and perception by Don

Ihde, Jean-Luc Nancy, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty.28 But none of these inquiries theorize

sound objects as such. There does exist an ample body of philosophical work on sound

alone, as on objects and materialism. Recent contributions to the philosophy of sound

include theories by O’Callaghan and Robert Pasnau.29 And the past few years have seen

new thinking about objects, including the emergence of “new materialist” philosophies

which rethink the Cartesian-Newtonian standard notion of matter as inert and passive,

arguing instead that it is alive, self-generating, and possessed of agency. Jane Bennett,

25 Casey O'Callaghan, "Object Perception: Vision and Audition," Philosophy Compass 3, no. 4 (2008).

26 Demers, Listening through the Noise: The Aesthetics of Experimental Electronic Music.

27 Brian Kane, "The Music of Skepticism: Intentionality, Materiality, Forms of Life," (PhD Diss.: University of California, Berkeley, 2006), Kane, "L'objet Sonore Maintenant: Pierre Schaeffer, Sound Objects and the Phenomenological Reduction."

28 Pierre Schaeffer, Traité Des Objets Musicaux (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1966), Edmund Husserl, Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy, trans. F. Kersten, 2 vols. (Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1983), Don Ihde, Listening and Voice (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007), Jean-Luc Nancy, Listening, trans. Charlotte Mandell (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (London: Routledge, 2002).

29 Casey O'Callaghan, Sounds: A Philosophical Theory (Oxford University Press, 2007), Robert Pasnau, "What Is Sound?," The Philosophical Quarterly 49, no. 196 (1999), Ihde, Listening and Voice, Roger Scruton, The Aesthetics of Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

14

Diana Coole, Samantha Frost, Graham Harman, and Timothy Morton are among those

who have recast objects and objects in this radical way.30

Overview of Chapters

Sound objects raise many provocative questions, but rather than address them all,

I undertake in-depth exploration of just a few issues that may interest philosophers and

musicologists. Collectively, the various definitions of the term sound object may also

offer a potentially valuable vocabulary for the analysis of several musical genres to which

traditional aesthetic categories cannot entirely do justice. This includes all kinds of

electronic music, from experimental electroacoustic to electronic dance music, as well as

sound art and non-electronic experimental music. In the following chapters, where

relevant, I discuss examples from various genres of electronic music and sound art. I do

not address the presence of materialism in discourses surrounding non-electronic music,

although I have done so elsewhere.31 My choice here is grounded largely in my personal

aesthetic preferences, as well as in the happenstances that: the term sound object was

coined as part of Pierre Schaeffer’s attempt to theorize electronic music; and the term is

employed today, almost exclusively, by electronic musicians.

30 Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), Diana Coole and Samantha Frost, eds., New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics (Durham: Duke University Press,2010), Graham Harman, Tool-Being: Heidegger and the Metaphysics of Objects (Chicago: Open Court, 2002), Timothy Morton, "Materialism Expanded and Remixed" (paper presented at the New Materialisms Conference, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, 2010).

31 Mandy-Suzanne Wong, "Action, Composition - Morton Feldman and Physicality" (paper presented at the College Music Society, Pacific Chapter Meeting, 2009).

15

Now, speculation continually begins, and begins again, as it considers what could

be, and thus uncovers various angles of thought. Each angle offers wholly different

possibilities for what could be, and itself reveals new angles. From each new angle or

perspective, speculation begins anew. Each of my chapters is therefore a beginning.

Chapter 1, “Sound Objects in Music,” examines the various types of sound object

found in electronic-music discourse, and the qualifying terms used to differentiate them

throughout the dissertation. I compare Schaeffer’s reducible sound object, a non-

referential sound divested of communicative responsibilities, to Roads’ structural sound

object, a tiny musical unit; Cutler’s transcontextual sound object, the “found” or sampled

sound; Godøy’s gestural sound object, the musical invocation of gesture; and the sound

object genre favored by ringtone composers. Although Post-Schaefferian composers and

theorists tend to discard his initial definition of sound object, they are almost unanimous

in crediting Schaeffer with the coinage of the term. Altogether, then, the contingent of

sound objects available to electronic-music discourse possesses a Deleuzian rhizomatic

structure, with Schaeffer at the root.

Although Schaeffer did not conceive the sound object as a metaphor, its

application today may be primarily metaphorical. In Chapter 2, “Sound Object as

Metaphor: Reification and Ideology,” I speculate on how the sound object may have

acquired its metaphoricity. I analyze its entailments, drawing on seminal theories of

metaphor by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson. I argue that one (but not the only)

powerful entailment of the term sound object is that sounds are conceived and treated just

as other objects are – objects such as commodities, tangible and visible things. Such

16

reification makes sounds easier to conceptualize and to work with – to master – but does

not necessarily provide an accurate account of sound. Drawing on the well-known

critique of reification by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, I suggest that ideologies

of domination enable the term sound object to persist in musical discourse, despite its

technical inaccuracies. I investigate how the work of sound sculptor Bill Fontana

unwittingly endorses these ideologies by embracing materialistic metaphors for sound.

Sound object is a relatively young term, dating from the late 1940s. However,

Chapter 2 hints that older philosophical preoccupations may be at work in it. Chapter 3,

“Convergences: Sound Objects, Aesthetic Autonomy, Musical Works,” identifies

foundations for certain aspects of sound-object theories in post-Kantian philosophies of

aesthetic autonomy (“art for art’s sake”), and “pure perception,” a notion in which

perception ignores aspects of experience in the hope of alighting upon essentialities. Also

in this chapter, I speculate on how certain preexisting terms in musical discourse may

have provided inspiration for the term sound object, in particular the term musical work.

Drawing on philosophies of the work by Goehr, Ingarden, Michael Morris, and others, I

attempt to demonstrate how sound objects exacerbate the impulses and problems that

attend upon the musical work.

Chapter 4, “Sound Object Analysis,” takes an entirely different road, investigating

the term sound object’s ability to serve as a primary category in musical analysis. I define

sound object analysis as, basically, sound object taxonomy: identifying and describing

various kinds of sound object that may be heard in pieces of music. As I approach a few

examples from this perspective – pieces by Alvin Lucier and the electroacoustic duo

17

Mem1 – I consider sound objects’ varied and flexible relationships with listening. We

could say, in fact, that since the various kinds of sound objects are sonic phenomena

heard in singular ways, a sound object is an occurrence of a singular act of listening upon

a given sound. As an analytical technique, sound object analysis has several advantages,

the greatest of which is that it is grounded in sound and listening. In active, fluid

interactions with sound, listening subjectivities participate in determining what they hear.

Sound object analysis thus serves as a telling contrast to traditional methods, founded in

predetermined categories such as pitch classes and tonal forms.

However, a consequence of subjectivity’s predominance in sound object analysis

is that it can never determine sounds’ characteristics with absolute certainty, therefore

cannot pinpoint whether or not sound objects are ever actually present. Where I hear a

certain kind of sound object in a piece of music, another listener may hear a melody or

something else. In sum, sound object analyses are relativistic. Chapter 5, “Subjectivity,

Discourse, and Truth in Sound Object Analysis” therefore attempts to address the

implications of the fact that sound object analysis can never say anything for certain

about music, listening, or sound. Sound object analysis offers no foundation for

agreements about music, and cannot even pinpoint the object of discussion (“a” particular

sound object or piece of music) with any manner of certainty. I therefore question the

potential of sound object analysis to function as a kind of discourse.

Nevertheless, I also propose that although sound object analysis cannot provide

ontological certainties about music, it can lead us to a truth of music. If, following Gianni

Vattimo and others, we understand “truth” to mean change and that which produces

18

change, as all genuine phenomena do, then sound objects can be and indicate truths by

functioning as fluid listening perspectives.

Chapter 6, “Listening, Dialogue, and Embodiment in EDM: A Case Study in

Sound Object Analysis,” further explores the interactions between listener and sound in

sound object analysis, via Yasushi Miura’s electronic dance music (EDM). An extended

case study that links sound-object theories to Jane Bennett’s philosophy of vital

materialism, this chapter poses a response to a pressing question in EDM-studies: is mere

listening a viable response to EDM? Without dancing, can listeners respond to electronic

dance music in a way that does justice to the music? By attempting to demonstrate that

the listening acts involved in sound object analysis are embodied interactions between

embodied entities, I propose that listening is comparable to dancing as a bodily response

to EDM. The aim of this chapter is to demonstrate how sound object analysis can

participate in a current musicological debate.

As my discussion draws to a close, I find that it has wrought more questions than

answers. Chapter 7, “Sounds, Objects, Materialisms,” begins anew with a fundamental

question: If a sound can be an object, what does this imply about the ontologies of sounds

and of objects? In contrast to Chapter 2, my final chapter argues that sound objects need

not be metaphorical: that they may be actual entities. Drawing on Casey O’Callaghan’s

recent philosophy of sound, and on theories of matter by René Descartes, Isaac Newton,

Diana Coole, and Jane Bennett, I speculate on how sounds might just be embodied,

material things, with the ability not only to be acted upon by musicians and listeners, but

also to act on us.

19

Chapter 1.

Sound Objects in Music

Rhizome

The Introduction as Glossary displays sound objects as objects in a collection:

things exist alongside one another. In the glossary, the relationships of terms to one

another remain obscure, unsaid. So this chapter begins again, in the aftermath of glossary

and introduction, with an attempt to theorize those relationships.

In A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari propose the rhizome as a

perspectival approach to multiplicities. The opposite of a rhizome is a tree, or root-based

structure: a single root becomes two roots, two roots become four, and so on until the tree

is grounded. Up above, the same structure repeats: one trunk gives two branches, each of

which gives another two. An analogy for teleological generation, the tree structure is that

of the family tree or genealogy. The rhizome, on the other hand, is contingent, not

teleological, and eschews binaries. To see a rhizomatic structure in the relationships

between things is to observe a wealth of different connections between them, not just the

inevitable “one-becomes-two” relationship between parents and children that recurs in

genealogies.

A rhizome ceaselessly establishes connections between semiotic chains,

organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences,

and social struggles. A semiotic chain is like a tuber agglomerating very

diverse acts, not only linguistic, but also perceptive, mimetic, gestural, and

20

cognitive: there is no language in itself, nor are there any linguistic

universals, only a throng of dialects, patois, slangs, and specialized

languages. There is no ideal speaker-listener, any more than there is a

homogeneous linguistic community.32

A rhizome yet possesses a principal root, but its authority as “founding father,” which it

would possess in the tree structure, is aborted. This is not to deny the root’s existence as

one of the rhizome’s constituents, all of which are not necessities but possibilities. In the

rhizome:

the principal root has aborted, or its tip has been destroyed; an immediate,

indefinite multiplicity of secondary roots grafts onto it and undergoes a

flourishing development. This time, natural reality is what aborts the

principal root, but the root’s unity subsists, as past or yet to come, as

possible.33

Sound objects in musical discourse collectively form a rhizome, with Pierre

Schaeffer as the aborted but subsistent root (and, as the glossary reveals, with tendrils

reaching far beyond music).34 It would be inaccurate and misleading to suggest that the

32 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 7.

33 Ibid., 5.

34 I must underscore that the rhizome to which I am referring is that which is theorized by Deleuze and Guattari, but which botanists would find horrifyingly inaccurate. I would like to thank Mitchell Morris for pointing this out to me. I do think, however, that Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizomatic structure can serve usefully as an image; it has been helpful to me in my attempts to think the contingent web of relationships and non-relationships that exist between various definitions of the term “sound object.” Bearing in mind that my project as a whole is an exercise in skepticism concerning the general efficacy of metaphors, figures, “images,” and even names, I do believe that such structures are useful to processes of

21

term sound object’s definition developed over the years in teleological fashion, or that

gradual changes in its usage followed sensibly on one another. In fact, when composers,

theorists, etc. adopt the term sound object, they define it to suit their objectives with little

or no regard for how the term is used in other contexts. There is one exception. Schaeffer

is credited almost unanimously by those who think in terms of sound objects. Yet no one

who appropriates Schaeffer’s terminology retains his definition. Were it to have a family

tree, the sound object would have a genealogy consisting entirely of cousins,

simultaneous and distant, who shared little more than a name. The rhizome is therefore a

stronger analogy for sound objects’ relationships.

The remainder of this chapter suggests how each musical-discursive treatment of

the term sound object may participate in a rhizomatic web of connection that includes all

the others. Along the way, I describe the various musical-discursive uses of the term

sound object in more detail than a glossary can provide. I emphasize: suggestion and

description, not explanation. As in Deleuze and Guattari:

we will not look for anything to understand in it [the sound object]. We

will ask what it functions with, in connection with what other things it

does or does not transmit intensities, in which other multiplicities its own

are inserted and metamorphosed, and with what bodies without organs it

makes its own converge.35

conceptualization (as I will argue in Chapter 2) and that Deleuze and Guattari formulate a worthy conceptual structure in the rhizome. 35 Ibid., 4.

22

Convergences

When the denizens of a rhizomatic structure come together, they do not form

unities. Instead they assemble at points of convergence, so that these points themselves

consist of the multiplicities of bodies and phenomena that congregate. Deleuze and

Guattari would emphasize the assembling and the multiple rather than the point.

Nonetheless, some common tendency or theme draws the multiple to assemble. In

musical sound objects, there are a few such themes: details and propensities that summon

the term sound object’s divergent manifestations to convergences.

First, sound object consistently implicates a phenomenon with definite borders,

analogous to the surfaces and skins that maintain the shapes of tangible objects. As a

result, sound objects may be dragged and dropped (or torn and sutured) to and from

various contexts, or contemplated in isolation from contexts, like single cells.

Second, all sound objects result from specific listening acts. One identifies and

distinguishes sound objects by attending to sound in ways that apply the aforementioned

boundaries and pinpoint the particular characteristics implied by one or several of the

term sound object’s definitions. Hence in all sound object theories, listening experience is

paramount: to define, categorize, and thenceforth theorize sound objects means to

experience sound. To clarify this point via contrast: where musical note falsely implies

that music is only notated text, written down and thus un-sonic, and where musical notes

are unable to account for the timbral, corporeal, and signifying aspects of sonic

experience, sound objects foreground music’s sonic mode of being, and only exist when

23

they are experienced. Those who work with sound objects do so with the intention of

thinking beyond musical notes.

Third, as I have mentioned, musicians and analysts who utilize the term sound

object are usually aware that it began with Schaeffer. Their uses of the term respond, with

affirmation or contestation, to his complex theories of sound objects and listening. Some

such responses are unconscious. Some adopt the term simpliciter and bestow a new

definition. Others, however, employ qualifying phrases to underscore the distinction

between Schaeffer’s notion of the sound object and their own. In what follows I qualify

all sound objects, so as to permit their comparison. I identify them according to how

listeners may experience them. I also rely heavily on the words of the artists and theorists

in question, so that I may be sure of properly representing their intentions.

Finally, the term sound object tends to refer to electronically generated sound,

even though its definitions may apply equally well to non-electronic sounds. The

definitions themselves tend to result from the conscious converging of individual creative

proclivities, informed by socio-historically predominant modes of thought, with

technology.

Thus: the diverse manifestations of the term sound object in musical discourse

converge with Schaeffer and his work; with listening experiences and attempts to explain

them; with tangible objects via common attributes; with electronic technology; and with

the notions, bodies, and circumstances that in turn converge with these phenomena from

the outside. The following chapters hopefully enact these convergences with greater

24

clarity. For now, let us look with more discerning eyes at the various definitions of sound

objects in music.

Reducible Sound Objects: Schaeffer

Music history remembers Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) as the inventor of

musique concrète: music made from recorded sounds. For him the word concrete denoted

where and how he acquired these sounds: by confronting “concrete,” quotidian life with

sound-recording equipment, venturing to street corners, train stations, concert halls, toy

closets, and kitchens with his microphone, phonographic disc engraver or, after 1955,

tape recorder. Concrete also describes his method of musical composition, which he

understood as “hands-on” experimentation, in contrast to the techniques of serial and

traditional composers. Schaeffer could not hold with these other techniques because they

relied on musical notes. To him, musical notes were both abstract (they are not sounds

but dots and circles) and limited (translatable only into the prescribed sounds of

traditional musical instruments). Contrarily he conceived his own music-making as the

“direct” manipulation of sound, the “material” of music captured on disc and tape, which

aimed at the listening perception – whereas only the eye can immediately access musical

notes.36 Granted, any notion that recorded sounds are unmediated is misguided, since

discs and tapes are themselves media. The point is that Schaeffer sought to emphasize,

first, that music and the study of music – of sounds configured into art – could not rely on

silent, notated schema as their foundations; second, that every sound is as musical as the 36 Schaeffer, Traité Des Objets Musicaux, 132.

25

next, regardless of its origin, and that music may therefore include any sound imaginable.

His first concrète pieces were the Noise Studies of 1948, which include his famous

Railroad Study, made from recorded train sounds. To commend his radical suppositions,

Schaeffer proposed that all music possesses a foundational, audible essence common to

every sonic experience.37 He called this elementary phenomenon a sound object.

For Schaeffer, a sound object is what we hear when we listen in a “reduced”

manner, in which we ignore all implications of sources or meanings that a sound may

make, and “reduce” our experience to that of the sound itself. I will refer to sounds heard

in this manner as reducible sound objects. Schaeffer wrote, “a sound object in the strict

sense of the word…[is a product of] 'reduced hearing' (écoute réduite) [which] enables us

to grasp the object for what it is...”38 Because he recognized that in “habitual experience,”

visible and tangible objects present as “given” (données) – readily there in front of us,

obvious – he chose the term object to connote the “given” basis of aural experience. He

believed that only reduced listening could lead us to an encounter with such an essential

object. In typical experience, we hear not the sound object but “structures” of meaning

that we impose on what we hear.39 In contrast, as Schaefferian disciple Michel Chion

explains:

37 Schaeffer scholars do in fact use this term, essence, to describe what he was after. See for instance Kane, "L'objet Sonore Maintenant: Pierre Schaeffer, Sound Objects and the Phenomenological Reduction." Emphasis added.

38 Schaeffer, Solfège De L'objet Sonore, 53. Emphasis added.

39 “Limiter ainsi l’investigation musical serait oublier que “les objets sont faits pour servier” et le paradoxe fundamental de leur employ: que, dès qu’ils sont groupés en structures, ils se font oublier en tant qu’objets, pour n’apporter, chacun, qu’une value à l’ensemble. C’est d’ailleurs une pensée naïve qui s’exprime ainsi en langage ordinaire: les objets, dans notre expérience habituelle, nous semblent “donnés”. En réalité, nous

26

The name sound object refers to every sound phenomenon and event

perceived as a whole, a coherent entity, and heard by means of reduced

listening, which targets it for itself, independently of its origin or its

meaning...It is a sound unit perceived in its material, its particular texture,

its own qualities and perceptual dimensions. On the other hand, it is a

perception of a totality which remains identical through different

hearings...40

Reduced listening is an acquired skill.

Sound still remains to be deciphered, hence the idea of an introduction to

the sound object to train the ear to listen in a new way: this requires that

the conventional listening habits imparted by education first be

unlearned...If one wants to get at the raw sound material [of music], one

must be far more brutal…this naturally means giving up meaning, no

longer turning to the context for help and finding criteria for identifying

sound which go against the habits of instinctive analysis.41

This “deciphering” of sound, meant to yield sound objects, is not a decoding of linguistic

signs. For Schaeffer, music is not a language, in which words point to things that are not

words. As he heard it, “music is, of course, listened to for its own sake and not as the

ne percevons pas les objets mais les structures qui nous permettent de les identifier. Ces structures ells-mêmes ne nous surprennent pas dans un expérience originale de l’écoute. Nous n’avons pas cessé d’entenre des sons depuis que notre sens de l’ouis s’est éveillé…” ———, Traité Des Objets Musicaux, 33.

40 Michel Chion, Guide to Sound Objects, trans. John Dack (http://modisti.com/news/?p=14239, 2009.), 32.

41 Schaeffer, Solfège De L'objet Sonore, 11, 67.

27

vehicle of any explicit message”: music should communicate nothing but the absolutely

sonic beauty of sound.42 Thus to “decipher” sound means, for Pierre Schaeffer, to

examine its intrinsic, essential qualities as though it were a curious shard placed under a

microscope.

Schaeffer modeled the technique of reduced listening on Edmund Husserl’s

phenomenological reduction or epoché.43 “For years, we had often done phenomenology

without knowing it,” he wrote, in his 1966 Treatise on Musical Objects.44 On the

following page, he elucidated that it was Husserlian phenomenology which he and his

colleagues had pursued, quoting extensively from Husserl’s Logical Investigations and

Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and Pure Philosophy. Brian Kane provides a

thorough analysis of Schaeffer’s relationship with Husserl, which the boundaries of my

inquiry impel me to describe more briefly.45

Husserl sought a foundation for the philosophical science of logic which, as we

will see, became a metaphysical quest for the essence of all things. He theorized a mode

of reflective thought in which one would abstain from any judgment of the kind we’d

normally take for granted, for instance the assumption that there is a physical world.

Since, following Descartes, Husserl believed that we cannot be certain about those kinds

42 Ibid., 65.

43 “Pendant des années, nous avons souvent fait ainsi de la phénoménologie sans le savoir...” ———, Traité Des Objets Musicaux, 262-63. See also 30, 132.

44 Ibid., 262.

45 Kane, "L'objet Sonore Maintenant: Pierre Schaeffer, Sound Objects and the Phenomenological Reduction."

28

of judgments, to locate facts of which we can be certain we must ignore, put aside, or

bracket out those contingent judgments in what amounts to a series of reflective

reductions. Schaeffer thought the same:

It is a readily admitted fact that different people hear differently and that

the same person does not always hear in the same way. We must therefore

stress emphatically that an object [that is, a sound object] is something

real, in other words that something in it endures through these changes and

enables different listeners (or the same listener several times) to bring out

as many aspects of it as there have been ways of focusing the ear, at the

various levels of “attention” or “intention” of listening.46

The first “level of attention” that listeners must attain, as the first step in our

approach to the sound object – to that enduring, common “something real” at the basis of

every auditory experience – is what Schaeffer named the acousmatic. According to his

Treatise, acousmatic listening “forbids us” from inferring any relationship between what

we hear and anything “visible, touchable, measurable.”47 In effect, acousmatic listening

abstains from associating sound with any instrumental sources. Kane, from whom a

book-length study on the acousmatic situation is forthcoming, provides a lucid

description.

46 Schaeffer, Solfège De L'objet Sonore, 59.

47 “[L]a situation acousmatique, d’une façon générale, nous interdit symboliquement tout rapport avec ce qui est visible, touchable, mesurable.” ———, Traité Des Objets Musicaux, 93.

29

The acousmatic experience reduces sounds to the field of hearing alone.

This reduction is really a matter of emphasis; by shifting attention away

from the physical object that causes my auditory perception, back towards

the content of this perception, the goal is to become aware of precisely

what it is in my perception that is given with certainty, or “adequately.”

This reduction is intended to direct attention back to hearing itself...48

Once we have achieved the acousmatic reduction, a further reduction in the form

of reduced listening enables us to hear the “sound itself,” which Schaeffer named “sound

object.” In other words, reduced listening is a double reduction: it encapsulates the dual

abstention from associating sound with instrumental sources (generating the acousmatic

situation) and with any other kind of meaning.49 Reduced listening prevents sound from

serving as a signifier of anything other than itself.

A key point here: it is listening experiences that bring reducible sound objects to

light, not visual and thoughtful analyses of silent, notated scores. Thus Schaefferian

theory remains true to its roots in phenomenology which, says Husserl, is “a new kind of

descriptive method...and an a priori science derived from it...[based on] a clarification of

what is peculiar to experience, and especially to the pure experience of the psychical...”50

Just as reduced listening attempts to reach the essence common to all listening 48 Kane, "L'objet Sonore Maintenant: Pierre Schaeffer, Sound Objects and the Phenomenological Reduction," 17.

49 See Schaeffer, Traité Des Objets Musicaux, 270-72.

50 Edmund Husserl, "Transcendental Phenomenology and the Way through the Science of Phenomenological Psychology," in The Essential Husserl, ed. Donn Welton (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999), 322-23. Emphasis added.

30

experiences, Husserlian phenomenology uses a particular kind of “psychical” experience

– the phenomenological reduction in reflective thought – to try to get to:

the psychical experience as such, in which these things [experiences] are

known as such. Only reflection reveals this to us. Through reflection,

instead of grasping simply the matter straight-out – the values, goals, and

instrumentalities – we grasp the corresponding subjective experiences in

which we become “conscious” of them, in which (in the broadest sense)

they “appear.”51

Focused on experience, phenomenology provides Schaeffer with an alternative

method of studying music – alternative, that is, to musicology and acoustics, which he

believed incapable of fully addressing musical experience. As he saw it, musicology aims

first at schema made of abstract, notated symbols, which a fixed set of instruments may

or may not concretize in sound. Sound and listening, the actual constituents of musical

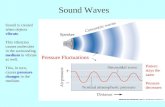

experience, are secondary. Similarly, though acoustics can diagram sound waves and

generalize sound’s behavior through the laws of physics, Schaeffer points out that those

diagrams and laws cannot precisely describe the listening experience, since our memories

and predilections influence what we hear.52 For him, music is a physical experience that

encapsulates both natural and cultural experiences. In turn, only experience – physical,

naturally and culturally conditioned listening – can convey what music is. Hence, he

51 Ibid., 323. Emphasis original.

52 See Schaeffer, Traité Des Objets Musicaux, 22.

31

writes, “If music is a unique bridge between nature and culture, let us avoid the double

stumbling block of aestheticism and scientism, and trust in our hearing...”53

The centrality of experience to Schaeffer’s method may have motivated his choice

of the term object (objet sonore) to describe his results. Philosophers speak of phenomena

that are or may be experienced as objects of experience (Kant, for example, throughout

the Critique of Pure Reason). Tangible objects indeed constitute many of our

experiences, although they are not all there is. Things shape the spaces we inhabit and

navigate; they are the surfaces we walk upon, the morsels we devour, the instruments of

our trades. We interact with things bodily, sensuously, and intellectually. Things are and

are molded by nature and culture. It therefore makes sense that in his quest for a

foundation of musical and auditory experience, to which experience itself can attest,

Schaeffer sought an object.

Further, Schaeffer’s sense that sound possesses a physically perceptible essence,

as corporeal as a thing, may have stemmed from the way in which he himself “handled”

sound, which he believed to be tactile. I refer once more to his compositional method,

which he may have understood as a working-upon sound itself, captured inside tangible

discs and tapes. As Mark Katz explains, especially in the early days of recording

technology, phonograph records were not seen as media that stood between listeners and

sounds, but as the sounds themselves, “frozen.”54

53 ———, Solfège De L'objet Sonore, 15.

54 “[O]ne of the most remarkable characteristics of recorded sound [is] its tangibility. Taking the disc out of its paper sleeve, he held the frozen sound in his hands, felt the heft of the thick shellac, saw the play of light on the disc’s lined, black surface. He was holding a radically new type of musical object, one whose very

32

At times, though, Schaeffer acknowledged that “[t]he instants that we hear cannot

be assessed in terms of inches of tape.”55 He knew that:

A sound object is not a magnetic tape [L’objet sonore n’est pas la bande

magnétique]. Though it is materialized by magnetic tape, the object, that

which we are trying to define, is no longer on the tape. On the tape, there

is nothing but the magnetic trace of a signal...56

Again, Schaeffer maintained that listening experience, not tape, is the key to the sound

object. Yet, at the same time, he asserted that recordings are like photographs: they are a

kind of framing (cadrage) that yields access to fixed objects (fixation sur l’objet),

circumscribed or excerpted from the continuum of experience, which may then be studied

and compared.57 We could read this comparison of sound recording to the visual, tactile

art of photography as an attempt to foreground the visual and tactile aspects of sound

recordings. Note as well that both photos and recordings reveal perceptible “objects.”

Given Schaeffer’s assertion of this relationship, it is my supposition that he understood

the unearthing of sound objects as a tactile and visual process as well as an aural one.

physicality led to extraordinary changes in the way music could be experienced.” Mark Katz, Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2010), 12.

55 Schaeffer, Solfège De L'objet Sonore, 39.

56 “L’objet sonore n’est pas la bande magnétique. Quoique matérialisé par la bande magnétique, l’objet, tel que nous le définissons, n’est pas non plus sur la bande. Sur la bande, il n’y a que la trace magnétique d’un signal...” ———, Traité Des Objets Musicaux, 95. Emphasis original.

57 “[S]on enregistré...[est une type du] cadrage d’autre part, qui consiste à ‘découper,’ dans le champ auditif un secteur privilégié. On retrouve ice, bien sûr, les expériences déjà connues et comprises, depuis la photographie, dans le domaine visuel. On sait que si la photographie nous prive de la fluidité de lavision, elle nous apport, à l’intérieur d’un cadre (qui nous cache fort heureusement le reste), une fixation sur l’objet, sur un détail de l’objet...” Ibid., 80.

33

Indeed, in musique concrète, which relies on recorded sound, manipulating or even

hearing sound means handling tangible objects, engraving and inspecting discs and tapes.

It is my contention that Schaeffer therefore equated sounds with objects not just in his

theoretical deliberations but also in his compositional and experimental intuitions.

In fact, his experiments aimed to make sounds lend themselves to reduced

listening by manipulating the discs and tapes on which the sounds were stored. Looping

the discs, speeding up or slowing down their rate of play, splicing tapes together or

clipping them to remove attacks and decays, all helped to obscure sounds’ origins,

creating the acousmatic situation that facilitated reduced listening. Following Husserl,

Schaeffer believed that subjecting recordings to endless variation would reveal sound

objects that remained the same throughout and despite the variations. Hence for Schaeffer

himself, the reductions that produced sound objects were not only listening acts but also

bodily movements that relied on tactile manipulations of tangible things. Perhaps, then,

the term sound object resulted from his belief that tinkering with tangible things would

yield more tangible things. In other words, what Schaeffer hoped to discover, by

dissecting discs and tapes in the manner of a laboratory scientist, were more elementary

sound objects.

Certainly Schaeffer harbored a scientific outlook on his work, the purpose of

which was “to re-create the materials and the circumstances of an authentic ‘musical

experience,’” just as physicists and biologists recreate and isolate natural situations in the

lab for the purpose of study.58 Trained as a radio engineer, he also maintained the attitude

58 ———, Solfège De L'objet Sonore, 11.

34

of a handyman or “tradesman.” He says, “Homo faber is a born meddler, a manipulator,

and sometimes a tinkerer. Wherever he finds himself, he will look around and Heaven

help whatever he lays his hands on.”59 And of his own composition studio, Schaeffer

writes, “on one side the studio, on the other the workshop.”60 This is simply more

evidence that he was aware of composition as a tactile experience, and thence of the

tangible qualities of manipulated sound. This awareness may help us to understand why

he conceived sounds as objects that may be uncovered by corporeal experiences based in

the sense of touch, as well as by aural experiences. (I will unpack the relationship

between sound objects and tangibility in Chapters 2 and 6.)

It is worth reiterating that even though reduced listening is a subjective experience

(only I can instigate the necessary reductions in my own mind, and only I can confirm

their success), Schaeffer was convinced that this experience would ultimately reveal

sound objects to be objective phenomena. In other words, for Schaeffer, sound objects

exist independently of any human mind. Hence the term sound object is not a metaphor

but refers to something real, possessed of “objective reality.”61 Schaeffer’s experiments

therefore sought “some rule which would provisionally hold true for any sound string and

enable us to extract from it that raw element which we have called the sound object...”62

What he means by “sound string” is not clear, but he does suggest that the “raw element,”

59 Ibid., 53.

60 Ibid.

61 Ibid., 59.

62 Ibid., 65.

35

which he believed to be the essence of music, is again akin to a corporeal object: a “brick

of sensation” from which complex sounds and compositions may be constructed.63

Schaeffer’s search for a “raw element” is a metaphysical as well as

phenomenological investigation. In a way, it is a quasi-Aristotelian search for a “first

cause” or origin, of music – a sonic cause, rather than a notated or conceptual one. Like

great metaphysicians from Thales to Hegel, Schaeffer seeks foundations, essences.

Husserl also conceived his work as phenomenological psychology that was

simultaneously transcendental ontology. This is because the “phenomenological

reduction (to the pure ‘phenomenon,’ the purely psychical)” involves the “methodical and

rigorously consistent epoché” of every naive assumption about the physical world as well

as the “seizing and describing of the multiple ‘appearances’ [of things as they appear to

us when we are conscious of them] as appearances of their objective units.”64 In other

words, that which appears to us in consciousness is “objective” for Husserl, just as the

products of reduced listening are objective for Schaeffer. And this is how both Husserl

and Schaeffer generate ontology from psychology: the appearances that

phenomenological reductions (psychical operations) yield can be taken as eidetic,

therefore objective and universal, units of being. In addition, the same reductive method

we use to find the basis of our psychical processes can be applied to the world in general,

to locate the essence of all things. Says Husserl:

63 ———, Traité Des Objets Musicaux, 60-61.

64 Husserl, "Transcendental Phenomenology and the Way through the Science of Phenomenological Psychology," 325.

36

Phenomenology as the science of all conceivable transcendental

phenomena and especially the synthetic total structures in which alone

they are concretely possible – those of the transcendental single subjects

bound to communities of subjects [–] is eo ipso the a priori science of all

conceivable beings...[that is, of] the full concretion of being in general

which derives its sense of being and its validity from the correlative

intentional constitution. This also comprises the being of transcendental

subjectivity itself, whose nature it is to be constituted transcendentally in

and for itself. Accordingly, a phenomenology properly carried through is

the truly universal ontology...65

For both Husserl and Schaeffer, investigating a psychical process – in Schaeffer’s case, a

mode of selective listening – unlocked the methodological tool that would set them on the

path to ontology: the science that promised to discover the essence of being.

To summarize, then: the first sound object – the doubly reducible sound object, a

sound heard in isolation from meanings and source-associations – has its roots in

Schaeffer’s faith that music cannot be abstracted from experience, and hence that

listening subjects take active roles in shaping what they hear. For Schaeffer the

phonographic tinkerer, the experience of music was tactile as well as aural. He believed

that, by means of phenomenological endeavors grounded in such experiences, listeners

and composers may unearth the stable, objective essence of music and sonic experience,

and so experience music’s ontology. Schaeffer named this essence a sound object in

65 Ibid., 333.

37

recognition of its audible and tactile facets, and of the surface-like boundaries that sounds

incur when reduced listening brackets out extra-sonic associations.

Schaeffer identified sub-types of reducible sound objects, classifying them “typo-

morphologically” according to their intrinsic, sonic features, i.e. the shapes of their sonic

envelopes.66 Thus he offered a unique vocabulary for the analysis of music in terms of its

actual, “concrete” sounds, posing a useful alternative to “abstract,” score-based analysis.

He enumerated impulsive sound objects, which are sounds of particularly short duration

with sharp attacks and quick decays (e.g. a click, a single staccato chord); iterative

sound objects made of repetitive attacks (e.g. a drum roll); and sustained sound objects,

continuous sounds with rare attacks and decays (e.g. drones).67 Note however that for

Schaeffer, all sound objects are of “medium duration,” neither too long nor too short for

the listener to memorize.68 Even sustained sound objects constitute continuous sounds

that nevertheless last only as long as this admittedly vague “medium” duration. In