Revision Del Origen de Las Villas FLANNERY

-

Upload

luis-flores-blanco -

Category

Documents

-

view

224 -

download

2

Transcript of Revision Del Origen de Las Villas FLANNERY

http://www.jstor.org

The Origins of the Village Revisited: From Nuclear to Extended HouseholdsAuthor(s): Kent V. FlannerySource: American Antiquity, Vol. 67, No. 3, (Jul., 2002), pp. 417-433Published by: Society for American ArchaeologyStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1593820Accessed: 25/05/2008 16:12

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sam.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the

scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that

promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

ARTICLES

THE ORIGINS OF THE VILLAGE REVISITED: FROM NUCLEAR TO EXTENDED HOUSEHOLDS

Kent V. Flannery

In Mesoamerica and the Near East, the emergence of the village seems to have involved two stages. In the first stage, individ- uals were distributed through a series of small circular-to-oval structures, accompanied by communal or "shared" storage fea- tures. In the second stage, nuclear families occupied substantial rectangular houses with private storage rooms. Over the last 30 years a wealth of data from the Near East, Egypt, the Trans-Caucasus, India, Africa, and the Southwest U.S. have enriched our understanding of this phenomenon. And in Mesoamerica and the Near East, evidence suggests that nuclear family house- holds eventually gave way to a third stage, one featuring extendedfamily households whose greater laborforce made possible extensive multifaceted economies.

En Mesoamerica y el Cercano Oriente, la evolucion de las primeras aldeas parece haber pasado por dos etapas. En la primera etapa, los miembros del grupo ocupaban una serie de pequenos abrigos circulares u ovalados, y mantenian dep6sitos comunales

para el uso de todos. En la segunda etapa, familias nucleares vivian en casas rectangulares con cuartos de dep6sito privados. Durante los ultimos 30 anios, datos del Cercano Oriente, Egipto, India, Africa, el Suroeste de los E.E.U.U. y la region Trans- Caucdsica han amplificado el conocimiento de tales cambios residenciales. Ademds, en Mesoamerica y el Cercano Oriente, se ha notado una tercera etapa: casas para familias nucleares fueron reemplazadas por residencias mds grandes, en las cuales una

familia extendida de 15-20 personas proporciono mano de obra para una economia compleja.

In 1972, Ucko, Tringham, and Dimbleby (1972) published a seminar volume heavy with settle- ment pattern and urbanization studies. Having

worked on early villages in Mesoamerica and the Near East, I contributed a paper comparing and con- trasting them (Flannery 1972). I have now been asked

by American Antiquity to revisit, in the light of new data, some of the issues raised by that paper. In the course of so doing I will discuss a later stage of vil-

lage organization, one which followed the period I covered in 1972.

At the time of the original seminar, I believed that in the early villages of Mesoamerica and the Near East I could recognize two types of societies, each documented in the ethnographic literature: The first type lived in encampments or compounds of circu- lar huts. Many of those huts seemed too small to house an entire family, and virtually all of the soci-

ety's storage units were out in the open, as if their contents were to be shared. Such societies seemed analogous to peoples in the ethnographic present whose encamped group is essentially a large

extended family, often patrilocal and polygamous. In cases where a man has only one wife, the marital pair may live together in a relatively large hut; when a man has multiple wives, each has her own relatively small hut. Widows, widowers, and unmarried young men may also have their own huts, and there can be a large hut for entertaining visitors. The group's infor- mal headman may have larger-than-average storage facilities, so that he can feed needy members of the settlement. Examples of this settlement type can be found in Archaic Mesoamerica and in the Natufian and Prepottery Neolithic A (PPNA) cultures of the Near East (Flannery 1972:30-38).

The second type of society lived in true villages of rectangular houses, each large enough for a nuclear family. In Mesoamerica the houses were of wattle- and-daub and had storage pits adjacent to them; in the Near East the houses had walls of mud, mud brick, or drylaid stone masonry and were divided into rooms, some of which served for storage. Archaeo- logical examples include Early Formative Mesoamerican sites and Prepottery Neolithic B vil-

Kent V. Flannery * Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1079

American Antiquity, 67(3), 2002, pp. 417-433

CopyrightO 2002 by the Society for American Archaeology

417

AMERICAN ANTIQUITY

lages of the Near East. Such villages might have spe- cial structures that could be shrines, temples, or men's houses, but their food was not stored in such a way as to suggest communal sharing (Flannery 1972:3846).

In both Mesoamerica and the Near East, villages of rectangular, nuclear family houses tended to

replace settlements of small, circular huts over time. I suggested in 1972 that the village of nuclear fam- ilies had certain advantages that might have led to this transition. Among other things, there is more incentive for intensification of production when each family can "privatize" its storage (including any sur- plus), rather than having to share with neighbors.

At the time, I fully expected that someone work- ing on Natufian or Prepottery Neolithic sites would eventually test my model for the first settlement type by doing the following: (1) excavating each circular hut in such a way as to keep its inventory separate; (2) using measures of association to search for men's and women's tool kits; (3) searching for relationships between tool kits and hut size, presence/absence of hearths, presence/absence of mortars, etc.; and (4) using multidimensional scaling to determine which hut inventories were most alike and which most dif- ferent, tying the results not only to hut size but also to the location of huts relative to each other. My sus- picion was that larger huts would have both men's and women's tool kits; some small huts with hearths would have only women's tool kits; some small huts without hearths would have only men's tool kits; and some adjacent huts might share artifact style prefer- ences. Stratum II of Nahal Oren seemed to cry out for such an analysis, since the preliminary report on Huts 9 and 10 showed suggestive differences (Fig- ure 1).

To be sure, I did not expect that every item in such a hut would be lying exactly where it was last used; we are all familiar with discard and postoccupational disturbance. What I expected we might get is the pat- tern we see when we piece-plot tools on numerous floors in Mexican caves and early villages: positive and negative associations that show up too often to be accidental. Despite the ravages of site formation processes, we cannot simply assume that no patterns will be left to detect.

While we still do not have such an analysis for Nahal Oren, many Near Eastern archaeologists have recently published Natufian or Prepottery Neolithic residential plans and artifact scatters, and wrestled

with the relationship between house type and social organization (see, for example, Byrd 1994; Rollef- son 1997; and many of the authors in Bar-Yosef and Valla 1991 and Kuijt 2000). While not everyone agrees on what the evidence means, a useful dialogue is growing.

What I Would Do Differently Today A lot has happened since the early 1970s, allowing me to reflect on what I would do differently were I to write the article today. I will list only a few pos- sible changes.

1. In seeking ethnographic analogies for settlements composed of circular huts, I drew heavily on the compounds of central African horticulturalists and herders. Today I would rely much more heavily on the circular hut camps of hunters and gatherers, who

provide better analogies for the Natufians and Late Archaic Mesoamericans. Today we have plans from many more hunter-gatherer camps than we did in 1972 (see, for example, Binford 1983; O'Connell 1987; Yellen 1977). Ironically, in the same volume as my original paper, Woodbur (1972) presented the plan of a Hadza camp that would have suited my pur- pose well, had I seen it before I began writing. Let us look at it now.

Site: A dry-season camp made by Hadza hunter- gatherers Location: Near Ugulu hill, Tanzania Date: October 1959 Observer: J. Woodbur (1972) Background: In 1959, roughly 400 Hadza occupied 2,500 km2 of bush to the east of Lake Eyasi in north- ern Tanzania. Territorial rules were sufficiently flex- ible so that any Hadza could live, hunt, or gather wherever he/she wanted; camps usually moved every few weeks, and could range in size from a single per- son to almost 100 people. The average camp, while not a fixed unit, might hold 18 adults (Woodbur 1972:193).

The Hadza settlement system provides consider- able information for archaeological model building. The Hadza studied by Woodburn like to live in rock- shelters or in the open, but avoid deep-chambered caves because they contain insect pests. During rainy periods they tend to return over and over again to the same rockshelters, but in the case of open-air camps they prefer to choose a fresh site, because pests are

418 [Vol. 67, No. 3, 2002

THE ORIGINS OF THE VILLAGE REVISITED

35

30 Structure 10

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

25

20

15

10

5

0

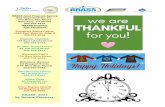

Axes, adzes, and picks Sickle blades and knives Arrowheads Borers Awls

6. Burins 7. Scrapers 8. Denticulated tools 9. Notched tools 10. Retouched flakes 11. Retouched blades

12. Bladelets and microliths 13. Planes 14. Stone tools 15. Basalt pestles 16. Obsidian blades

Figure 1. Top: Prepottery Neolithic huts from Level II of Nahal Oren, Israel. The dashed lines indicate terraces on the talus slope below the cave. Bottom: Histograms comparing tool percentages in the assemblages from a large hut (Hut 9) and a small hut (Hut 10) at Nahal Oren. (Redrawn from Stekelis and Yizraely 1963: Figures 3 and 5.)

35

Structure 9 30

25

20

15

10

5

1.

2. 3. 4. 5.

Flannery] 419

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

AMERICAN ANTIQUITY

attracted to their previous refuse. Favored camping areas are often identified with a landmark (such as a

prominent hill), which is given a toponym. For exam-

ple, within a one-mile diameter surrounding the favored landmark known as Ugulu hill, Woodbur

says that one could find traces of at least 20 camps from previous years. Archaeologists working on

hunter-gatherers often find ancient versions of such favored landmarks; the Mt. Carmel range in Israel (Garrod and Bate 1937) and the Mitla "Fortress," a

chert-bearing mesa in Mexico's Oaxaca Valley (Flan- nery and Marcus 1983:300), were the focal points of repeated encampments.

Figure 2 shows a Hadza dry-season camp mapped by Woodbum. The camp, roughly 28 m in diameter, had 17 shelters. The shelters were simple, circular, above-ground huts consisting of a framework of branches covered with grass and "put up by the women in an hour or two" (Woodbur 1972:194). The place chosen for the camp was, as customary, several miles from the nearest human neighbors and

away from the paths taken by game. While topogra- phy and prevailing wind were taken into account, the

layout of the huts was also determined by social fac- tors that would not likely be obvious to an archae- ologist. For example, Hadza custom dictates that the hut of a married couple be placed so that the wife's mother lives "neither too close nor too far away" (Woodbum 1972:197). Overall, "the arrangement of huts within a camp is ideally patterned in accordance with the social relations existing between at least some of the individual members of the camp" (1972:204).

The camp shown in Figure 2 reinforces several

points I made in 1972. Some huts were designed to house only one person, such as a widow/widower or an unmarried adult; others might hold two parents and a child. (Because Woodburn does not give the sizes of individual huts, my artist made them all the same size.) Thus some huts probably included only a man's tool kit, others a woman's tool kit, still oth- ers both kits. If we knew more about stylistic pref- erences, we might even be able to suggest which huts were occupied by a mother and daughter from the same family. For example, Huts b, c, and d housed married daughters of the woman in Hut a; those daughters had arranged their huts so as to leave their mother "neither too close nor too far away." Assum- ing these daughters had learned various crafts from their mother, the women's artifacts in Huts a, b, c,

qC

?0 O QoC)Om 'oo6~

kC '

Gg

Qa

Q0d

e

The woman in Hut j has a son in Hut k and daughters in Huts f, h, and i.

The man and woman in Hut a have daughters in Huts b, c, and d.

The man in Hut q has a son in Hut f; the woman in Hut q has a daughter in Hut o.

The man in Hut e has a daughter in Hut n.

Figure 2. Plan of a 1959 Hadza camp near Ugulu, Tanzania. The social relationships of some of the huts' occupants are given (redrawn from Woodbum 1972: Figure 1).

and d might show stylistic similarities. The same could be suggested for the woman in Hut j and her daughters in Huts f, h, and i.

2. The fact that Hadza huts are "put up by the women in an hour or two" supports an important observa- tion by my colleague Raymond Kelly, who is cur- rently engaged in a reanalysis of hunter-gatherer societies (see Kelly 2000). In Kelly's ethnographic sample, just as in an earlier cross-cultural study by Murdock and Wilson (1972), impermanent above- ground huts tend to be made by women; this is inter-

esting, since it suggests that women are the ones making the critical decisions about residence size, shape, and location. Once huts become more labor- intensive, however (as in the case of digging subter- ranean foundations and lining them with drylaid stone masonry), housebuilding becomes increasingly the work of men. And men are even more likely to be the builders of rectangular houses with mud or mud brick walls (Raymond Kelly, personal com- munication 2001; Murdock and Wilson 1972).

3. In my 1972 paper I mentioned associations between circular houses and impermanent settle- ment and between rectangular houses and permanent settlement (Robbins 1966; Whiting andAyres 1968).

420 [Vol. 67, No. 3, 2002

THE ORIGINS OF THE VILLAGE REVISITED

Unfortunately, this led some readers to believe that the geometric shape of the residence was the crucial variable. In fact, my main distinction was between (1) societies where small huts are occupied by indi- viduals and storage is shared and (2) societies where larger houses are occupied by whole nuclear fami- lies, and storage is private.

A major improvement, therefore, would be to incorporate more discussion of risk and privatiza- tion ofstorage. Only a decade after my paper, Wiess- ner (1982)-drawing on a completely different

ethnographic sample-proposed a dichotomy that complemented mine. She contrasted hunter-gatherer societies in which risk is assumed at the level of the group with those in which risk is assumed at the level of the family.

In the first type of society, widespread pooling and sharing of food ensures that risk and reward are accepted by the group as a whole. Food storage is out in the open and shared by all occupants of the settlement, as appears to have been the case with the Natufian and PPNA sites I discussed (Flannery 1972:31). There is little incentive to intensify pro- duction in such societies, since whatever is produced must be shared. Wiessner (1982:174) points out that when such a group settles, they have two basic options. One is to build a large structure to house the entire group, such as the communal winter houses of the Ammassilik Inuit, or the long houses of some Upper Paleolithic mammoth hunters (Soffer 1985). Alternatively, they can distribute the members of the group through a series of smaller huts, which is what the Hadza do; I suspect that this is what the occu- pants of Nahal Oren did. Such huts are often circu- lar, contain no storage facilities, and vary in size depending on whether they are built for a marital pair, an unmarried son, a widow, or one of the wives of a polygamous headman.

The second type of society accepts risk and reward at the level of the individual nuclear family. As Wiess- ner (1982:173) puts it, such societies have a more "closed" site plan, "one which has either widely spaced household units or closed-in eating and stor- age areas, in order to avoid the jealousy and conflict which might arise from one household visibly hav- ing more than another." Each nuclear family has its own house and, most importantly, its own private storage. Here exists more incentive to intensify pro- duction, since any resulting surplus does not have to be shared; each family decides how much or how lit-

tle to produce. I suspect that this is what we see at most Prepottery Neolithic B (PPNB) villages, in the upper levels at Beidha and Tell Mureybit, and at Jarmo and Ali Kosh (Flannery 1972:40-43).

In other words, some time between Late Natufian and PPNB in the Near East, villages of rectangular, nuclear family houses with private storage rooms replaced encampments of irregularly sized circular huts with shared or "group" storage. Why did this change take place? I suspect that Prepottery Neolithic societies grew so fast, and settlements became so large, that not every family considered itself closely enough related to its neighbors to be willing to share the risks and rewards of production. Privatization of storage-which can even include the closing off of outdoor work space with a mud wall (Flannery 1972: Figure 5)-is a way of freeing one's family from hav- ing to share with less-productive neighbors. And for the rest of the Neolithic period, families who were willing to work harder and store the products pri- vately began to outdistance their neighbors eco- nomically.

4. Colleagues working in Egypt and the Southwest U.S. have pointed out to me that it is not necessary to abandon circular residences in order to privatize storage: you simply have to make the circular houses larger and bring the storage inside. Predynastic Egyp- tians continued to live in circular, semisubterranean houses long after their neighbors in the Levant had adopted rectangular residences. The Predynastic houses were variable in size, with many being large enough to accommodate a family; others appear to have been used for storage (see for example Brun- ton and Caton-Thompson 1928).

Wills (1992) makes a similar point in his contrast between Shabik'eschee village (Chaco region) and the SU site (Mogollon region). Shabik'eschee had circular pithouses that seem too small for entire fam- ilies (average floor area, 17.8 m2) and have no inter- nal storage pits. At the SU site, while many pithouses were still curvilinear, they averaged 40 m2 and could be as large as 80 m2. These larger pithouses, which could accommodate a nuclear family, had storage pits inside the house that were presumably private. These storage pits provided an average of 2.8 m3 storage capacity per house, which Wills (1992:165) converts to 253 kg of maize-enough, he reckons, for a fam- ily of five for three months.

Wills suspects that increasing dependence on agri-

Flannery] 421

AMERICAN ANTIQUITY

culture is somehow involved in the shift to privatized storage, and he raises a number of intriguing possi- bilities. He cites Plog's (1990) suggestion that while agriculture can raise the productivity of an economy, it often does so at the cost of increasing variance around the mean output. He further draws on Win- terhalder's (1990) conclusion that farmers are better off restricting their sharing to closely related indi- viduals because-since farmers have production cycles lasting months or years-it is hard to moni- tor people who "cheat" by not contributing as much as they receive. To this I would add a point made ear- lier in this paper: as villages grow, not all families are closely enough related by blood or marriage to be willing to share with neighbors.

Finally, Wills (1992:169) argues that reduced

sharing, more restricted land tenure, and growing pri- vatization of storage greatly increased the economic options of early farmers. If this is so, we might expect to see in the archaeological record a lot more varia- tion in house size, house shape, storage facilities, rit- ual buildings, burial patterns, and other features. (I should add here that archaeologists working on ancient states, like Sumer or the Inca, find even greater variety in storage strategies than I discuss here. Most of those strategies, however, were not options for foragers or Neolithic farmers.)

5. Kohler (1993:280), also drawing on Southwest U.S. data, warns against a simple equation between (1) foraging societies and communal storage/pro- duction and (2) agriculturalists and household stor- age/production. Citing evidence from stable-carbon

isotopes and coprolite analyses, he argues that dif- ferences in agriculture alone cannot explain the dif- ferences in architecture between the Chaco and Mogollon settlements. (In a later section of this paper, I examine differences between Zapotec and Mixe set- tlements in Mexico, which also reflect cultural vari- ables beyond the commitment to maize agriculture. It appears that, far back in time, human agents made strategic decisions among alternatives for reasons which are not always apparent archaeologically.)

Just as Wiessner (1982) calls attention to varia- tion among hunter-gatherers in the level at which risk is shared, Kohler (1993:280) points to variation in the kinds of foods foraging people are willing to share. For example, among the Ache, Machiguenga, and Yanomamo, things that come in "big packages" (like major game and fish) are shared, while things

that come in "small packages" (like plants gathered by women) are not. Thus, if horticulture emerged in Southwest economies as an extension of women's gathering activity, "its products may not be so widely shared among households, particularly if production variance was low" (1993:280). The implication is that it is not enough to know whether a commitment to agriculture has been made; we must also know whether a product was considered men's or women's work.

6. According to Kohler (1993:281), "the first settle- ments in the Southwest that clearly correspond to Flannery's rectangular-house type appeared in the northern Southwest aboutA.D. 760." Storage by this time was "clearly associated with the household" (1993:281) and circular pit structures were evolving into ritual buildings, often shared by 2-3 households who now lived in rectangular surface structures. (In a later section of this paper we will see a circular building type which may have played a similar role in the early Near East.)

The transition from circular to rectangular houses in the Southwest U.S. has been described for the Anasazi of the Four Comers region by Gross (1992). The Tres Bobos subphase (A.D. 600-700) had rela- tively shallow circular pithouses with antechambers, accompanied by round-to-oval freestanding surface rooms of brush and mud. During the Sagehill sub- phase, pithouses became deeper and were more nearly square; surface structures also became more nearly square, and had a more substantial super- structure. By the time of the Dos Casas subphase (A.D. 760-850), pit structures had become square and had vents rather than antechambers. Single dwelling sites had given way to multiple dwelling units of rectangular rooms. Surface rooms formed contiguous blocks, with larger rectangular rooms in front and smaller rectangular rooms behind them. By now it was clear that the back row of rooms were substantial storage structures with post-supported roofs and stone slab-reinforced walls, while pit- structure function had changed from residential to ritual.

Based on these Southwestern data, were I to rewrite my 1972 paper, I would reinforce the point that architectural changes depended on many vari- ables-some economic, some social-and that in some regions, storage rooms might be better built than the houses they accompanied.

422 [Vol. 67, No. 3, 2002

THE ORIGINS OF THE VILLAGE REVISITED

7. We have already mentioned the fact that circular huts lasted longer in Egypt than in the Near East. Fur- ther evidence that replacement by rectangular houses could take place at any time period comes from the Trans-Caucasus region of Azerbaijan and the Geor- gian Republic. There Sagona (1993) reports that sixth-millennium B.C. Neolithic settlements like Shulaveris Gora had circular-hut compounds of sun- dried mud brick (and some wattle-and-daub), partly subterranean. Houses were small (5-7 m2) and had even smaller storage cells (1.25-2.0 m2) attached to them, either directly or by a wattle-and-daub fence. These communities resembled the encampments of the Hadza or Natufians, in that many huts were too small to have housed a family.

By the early Bronze Age (early fifth- to middle fourth-millennium B.C.), sites like Kvatskhelebi had standardized, rectangular two-room houses with rounded comers. These houses were of wattle-and- daub over a framework of posts; while the main room was clearly residential, the second room may have been an attached rectangular porch. The floor space of these houses was 25-40 m2, adequate for a nuclear

family. Each house had a beaten clay floor, a central circular hearth, and a bench set against the back wall.

This transition from circular huts to nuclear fam-

ily houses took place relatively late in the Trans- Caucasus. Sagona (1993) attributes the more

ephemeral-looking Neolithic compounds to the fact that transhumant herding mitigated against perma- nent settlements. By the Bronze Age, there were per- manent settlements of nuclear-family households at lower elevations, while the higher elevations still had

less-permanent settlements for the summer pastur- ing of animals. We should thus bear in mind that the relative importance of herding in a mixed farming- herding economy can be another variable influenc-

ing house design and settlement type.

8. Several colleagues have pointed out that the shift in risk acceptance from group to family was not irre- versible; changing economic conditions could revive both earlier house types and patterns of risk accep- tance. I will mention only one well-documented case.

On the Deccan Plateau of western India, farmers of the Early Jorwe phase (1400-1000 B.C.) lived in large, rectangular houses with wattle-and-daub walls over a low mud foundation (Dhavalikar 1988). Houses had 15-35 m2 of floor space, with the larger ones divided into two rooms by partition walls. This

is considered a period of relative prosperity, with cereal agriculture and herding supported by adequate rainfall.

In the Late Jorwe phase, however, it is believed that a drop in rainfall at 1000-700 B.C. led to a "decline in agriculture" and "resulting poverty" (Dhavalikar 1988:20). As Late Jorwe peoples turned to a semi-nomadic herding economy, the large houses of the previous period gave way to small circular huts, which tended to occur in clusters of 3-4 or more. The huts were of perishable material, though post- molds were found along the edges of the floor. Larger huts seem to have been for humans, while smaller ones were for domestic animals. Most significantly, the hearths and storage bins were located where they could be shared by whole clusters of huts (Dhava- likar 1988:13). Dhavalikar attributes the changes of Late Jorwe to deteriorating economic conditions, which is reasonable in this case; elsewhere in the world, of course, there could be alternative reasons for a shift to semi-nomadic herding.

9. Finally, were I to rewrite the paper today, I would be able to draw on a much wider range of formulae for calculating population from floor space. In my original paper I chose to use Naroll's (1962) straight- forward measure of 10 m2 of roofed space per per- son, while mentioning Cook and Heizer's (1968) suggested improvement (2 m2 per person up to six

persons, thereafter 10 m2per person). Now LeBlanc (1971) has offered his own improvement to Naroll's approach, and Watson (1979) and Kramer (1979) have derived formulae from the ethnoarchaeology of the Near East. For that same part of the world, Henry Wright now recommends the figure of 1.2 persons per room, which emerges from Gremliza's (1962) study of present-day Iranian villages (Henry Wright, personal communication, 1998). While each of these authors' approaches is different, none of them doubts the existence of a relationship between population and floor space. I suspect that while more sophisticated measures work well in the regions from which they were derived, it is probably all right to use a simple method when working in a less-stud- ied area.

Taking the Next Step: From Nuclear to Extended Households

Having considered a number of improvements to my 1972 paper, let me now examine the next step in the

Flannery] 423

AMERICAN ANTIQUITY

0 1 2m I I I

Figure 3. Prototypic nuclear family house from Operation IX, Level 2, at Matarrah, Iraq (redrawn from Braidwood et al. 1952:Figure 3).

evolution of some villages-the emergence of the extended household.

For the period 6500-5500 B.C. (uncalibrated) in the Near East, the house shown in Figure 3 would be

prototypical. It could easily accommodate a family of five and had larger rooms for sleeping or for enter- taining visitors, plus at least one smaller room for pri- vate storage. Indeed, in many parts of the world, nuclear households like this one continued for thou- sands of years to be the basic units of which villages were composed. However, in some regions- includ- ing both the Near East and Mesoamerica-they were

gradually replaced by households that could have held 15-20 people, or even more. Some of those larger households had multiple hearths, multiple kitchens, multiple sets of features and storage facilities. It appears that as some offspring reached adulthood and married, they remained attached to the parental house- hold rather than moving away to form their own. I will devote the rest of this paper to that next stage of vil- lage development, the replacement of nuclear house- holds by extended family households.

One can think of several reasons why extended households might emerge. The most obvious is eco- nomic: in some subsistence systems, the nuclear fam- ily is simply not a viable economic unit. In many parts of the Near East, married sons remain attached to the household of their father because the combination of two tasks-cereal agriculture and the grazing of herd animals-requires a division of labor beyond

the capacity of a nuclear family. By 5500 B.C. many Near Eastern villages not only grew wheat, barley, lentils, and peas for food, but also raised flax for linen and had added cattle and pigs to the herding of sheep and goats. A family of 15-20 simply had more man- power to perform all the disparate tasks in such an economy, which could include some kind of craft production as well. Between 5500 and 5000 B.C., some parts of the Near East developed households that were not only large, but had stereotyped ground plans and a trimodal room-size distribution.

Extended households also emerged in Formative Mesoamerica, but there we cannot argue that it was encouraged by a mixed farming-herding economy. Rather, it appears that genuine strategic differences in land clearance and agricultural landholding devel- oped, even between neighboring cultures in broadly similar environments. Some groups chose to accept risk at the level of the individual family or farm- stead; others chose to buffer risk by collaborating in

larger social groups. In a classic study, geographer Oscar Schmieder

(1930) contrasted the agricultural strategies of the Zapotec and Mixe peoples of Oaxaca, Mexico. Among the Mixe, he noted, each family cleared the land it needed for cultivation and built its house beside its fields. The settlement pattern became one of isolated farmsteads, where each family "was con- fronted by all the tasks of everyday life" and "the distance from neighbor to neighbor was often great" (Schmieder 1930:77). In contrast, Zapotec families collaborated in clearing land by means of large work

groups, then distributed the land among the families who participated. Because the big work gangs moved from place to place, a family who participated could wind up owning parcels of land scattered through several environments. This process not only spread risk among many families, it also minimized the chances that a local environmental disaster would damage all of a family's plantings. As Schmieder points out, it also promoted the growth of large, per- manent villages; since there was no point in moving one's house to fields that were scattered over so large an area, families continued to live within the larger cooperating group. In these larger and more compact villages, "a differentiation of activities became pos- sible. Crafts, art, and science developed and were maintained by the mass of the population which nev- ertheless remained agricultural" (Schmieder 1930:76).

424 [Vol. 67, No. 3, 2002

THE ORIGINS OF THE VILLAGE REVISITED

Another variable leading to extended households in Mesoamerica was elite status. Elite families of the Middle Formative (850-500 B.C., uncalibrated) tended to have bigger houses, more outbuildings, and more storage facilities, which were often built of adobe rather than wattle-and-daub (Marcus and Flannery 1996:131-138). Having more members allowed a chiefly extended family to produce more food and more craft goods.

In his analysis of Moala, an island in Fiji, Sahlins (1962) discovered many of the same principles seen among the Zapotec by Schmieder. In the village of Keteira, forest clearing was done by large work gangs and had led to a "traditional pattern of dispersed land use" by extended families. Indeed, independent nuclear family existence could be "hazardous," depending as it did on the productive ability of only one adult of each sex. Inequalities in subsistence pro- duction among nuclear households could be "miti- gated through extended family pooling of labor and goods" (Sahlins 1962:123). As among the Zapotec, extended families could mobilize a large labor force when needed, or could "release some men for work in distant gardens without hardship for those remain- ing in the village" (1962:124).

The pressure to maintain large extended families was even greater if one were a chief in Moala, since the chief's household was expected to produce reserves of food for external distribution. Thus,

A large extended family embracing effective gardeners jealous of their social prerogatives maintains a chief's strength; it enables him to produce, to accumulate, and to distribute as a chief should. Thus the chiefly family of Naroi, paramount on the island, with six nuclear con- stituents is twice the size and more of other houses of the village [Sahlins 1962:125].

In the next section of this paper, we will look at three archaeological examples of early extended households, one from the Near East and two from Mesoamerica. The first example is particularly infor- mative, because it shows us five consecutive stages in the transition from nuclear to extended families.

Name: Tell Hassuna (Levels Ic-V) Location: In the arable Y created by two seasonal wadis whichjoin a tributary of the Tigris, 30 km south of Mosul, Iraq. Hassuna lies on the border between the cultivated Assyrian plain and the arid grazing lands of the al-Jazireh.

Probable date: 5500-5100 B.C. (uncalibrated) Excavators: Lloyd and Safar (1945) Description: The extent of the Level Ic village is hard to estimate, but may have been 1.0-1.5 ha. The site later grew into a rectangle 200 by 150 m (3.0 ha) in extent. Levels Ic-V reflect a fully sedentary village of mud-brick houses, with the kind of mixed econ- omy one would expect at the "edge area" between alluvium and grazing land.

Storagefacilities: Useful information is provided by circular storage bins at Hassuna, of which more than 30 were found. The excavators describe these as unfired storage jars (.6-1.5 m in diameter, with a mean of about 1.0 m) whose thick walls were made from straw-tempered clay. Outside, they were heav- ily coated with bitumen (natural asphalt); in some cases they were also given a coat of gypsum plaster on the interior. They had been constructed above ground, but instead of being fired they were lowered into a pit until their mouths were level with the floor, then fixed in place with fill. Decayed chaff and car- bonized grain inside the bins suggest their use as grain silos, with broken bowls used as dippers to remove grain when needed.

Using the formula for the volume of a sphere, one can estimate the capacity of these storage bins to have ranged between .11 and 1.77 m3, with a mean of .52 m3. The largest number recovered in any level was six, with an estimated total capacity of 3,120 liters. If we assume that a typical nuclear family consisted of 5 persons (2 of them children), this quantity of grain could have satisfied the annual cereal require- ments for half a dozen nuclear families. The storage bins therefore provide a second line of evidence for extended households, independent of the architec- tural plan.

Architectural stratigraphy: Few sites document the emergence of the extended household as clearly as Hassuna. The earliest buildings at the site (Lev- els Ib and Ic) were apparent nuclear family houses of 3-5 rooms. Although each house might share a courtyard with one or two others, each seemed to be a small, self-contained unit. By Level III, however, there were irregular complexes of 15-20 rooms flanking 2-3 sides of an open court. Often one part of the complex looks more "planned" than the rest, as if it were an original nucleus to which later rooms were added by accretion. What may be implied is that as families grew, they did not fission when they reached 5-6 members, their offspring moving away

Flannery] 425

AMERICAN ANTIQUITY

N=76 x=6.7 s.d.=6.1

Trimodal at 2, 10, & 15 (T = -5.08)

1234567 iI I1

2 3 2ci

" "93c3 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 >30

[] Courtyard W?] Possible courtyard

Figure 4. Sizes of all measurable rooms and courts in Levels Ic-V at Hassuna, Iraq, rounded to the nearest square meter. Note the trimodality at 2 m2, 10 m2, and 15 m2.

to construct a new house. Instead, new rooms were

gradually added (according to no set plan) until the house could accommodate a dozen, or even 15-20, persons. Within this complex, the presence of sev- eral storage rooms and several kitchens in different

parts of the building suggests that meals were being prepared for several subgroups (nuclear families?). Finally, in Levels IV and V, we see residential com-

plexes of 15-20 rooms whose layout appears more

planned. Rather than allowing the compounds to

grow haphazardly, the architects now knew in advance that they needed to house more than a nuclear family. Not only was the layout more regu- lar, it involved a trimodal distribution of room sizes that is statistically significant; a Student's T test shows that the chance of the trimodality being ran- dom is less than .001, based on a sample of 76 rooms. The three main room types are (a) squarish rooms with an average of 2 m2 of floor space, likely for stor- age; (b) elongated rooms with an average of 10 m2 of floor space, probably for sleeping or working; and (c) rooms averaging 15 m2 or larger, most of them

probably courts (Figure 4). Level Ic (Figure 5). In an exposure of just under

500 m2, Lloyd and Safar (1945) found parts of three nuclear family houses. Flanking an open courtyard with storage bins of the type described above, the houses were equipped with ovens and heavy stone mortars. The northernmost house had roughly 25 m2

of bounded space divided into 5-6 rectangular units, the largest of which might have been an interior court. Level Ic also produced the partial plan of a cir- cular building whose function could not be deter- mined. Similar buildings, called by the Greek term tholoi, occur at other sites of the same period. While excavators differ in their interpretation of tholoi, most consider them ritual buildings associated with groups of related households.1

Level II (Figure 6). This level produced a com-

plex of 18-20 rooms arranged around two sides of an open area. Here Lloyd and Safar clearly felt that they were dealing with two previously separate dwelling units that had coalesced over time. The southern sector seems to preserve the plan of a nuclear household with an open court, a large room for sleeping or receiving visitors (10 m2), a pair of

elongated rooms (3.5-5 m2) with an oven, and a pair of squarish rooms (34 m2), at least one of which was for storage. The northern part of the complex resembles a house that had formerly consisted of four large rooms (10-16 m2) surrounded by much smaller ones (1-5 m2), at least some of which were for storage.

Level III (Figure 7). A 500 m2 exposure of this level produced the partial plans of two mud-brick houses separated by a narrow alley. The house to the west had more than 80 m2 of bounded space, and looked like a former nuclear family house that had

Totals for

levels / IC-V

Size (m 2)

D Room

426 [Vol. 67, No. 3, 2002

THE ORIGINS OF THE VILLAGE REVISITED

Oven

5m 5 m './...t Figure 5. Plan of nuclear family houses around an open court in Level Ic at Hassuna (redrawn from Lloyd and Safar 1945:Figure 28).

Mortar Mortar T

court area with jars, flint chipping debris, etc.

Figure 6. Irregular extended household from Level I at Hassuna (redrawn from Lloyd and Safar 1945:Figure 29).

grown haphazardly to extended family size. One

doorway, perhaps the primary entrance, had a paved threshold with a stone socket on which the door had

pivoted. Once again, the basic components of the house were large, elongated rooms (12-15 m2) accompanied by smaller, usually squarish rooms (1.5-6 m2). Large storage bins were set in the floors of rooms and courtyards; most would have had vol- umes of .5 m3 or more, and the total capacity of the six shown in or near the western house would have been greater than 3,120 liters.

Level IV (Figure 8). Level IV yielded an extended family household that appeared to have been planned rather than growing by accretion. It occupied three sides of a 15 m2 courtyard, with the eastern sector providing the most symmetrical plan. Lloyd and Safar (1945:274) described that unit of five rooms and a corridor as similar to the houses of present-day villages in the area; a slightly larger cen- tral room (4.5 m2) with an oven was flanked on the south by paired elongated rooms (each 3.5 m2), and on the north by paired squarish rooms (each 1.5 m2). The latter (presumably storage rooms) were filled with restorable pottery. Attached to the eastern unit were less-uniform rooms, one of which may have been a walled, outdoor work area with three mortars and an oven. There were at least three hearths and four ovens spaced around the household, suggesting the presence of several kitchens. This building must have had more than 80 m2 under roof, and if all the surrounding courtyards were associated with it, there were over 120 m2 of bounded space. This is enough space to give us an estimate of 8-12 persons using Naroll's method, and there are enough rooms to give us 18 persons using Wright's method. Based on the placement of ovens and hearths, I suspect that we are dealing with an extended household of perhaps three related nuclear families, each of which ground its own grain and cooked its own gruel or bread, but also shared storage and work space with coresidents.

Level V (Figure 9). This level yielded a house that appears to have been planned from the outset to accommodate an extended family. More than 140 m2 of bounded space give us an estimate of 14-15 per- sons by Naroll's method, and there are enough rooms to provide an estimate of 20 persons by Wright's method. In Level V, the trimodal room-size distrib- ution is particularly clear; there are big, elongated rooms (10 m2), courts (>15 m2), and small, squarish cubicles (2-4 m2). Lloyd and Safar saw the critical

Flannery] 427

AMERICAN ANTIQUITY

Storage J i bins 5m

Figure 7. Irregular extended household from Level III at Hassuna (redrawn from Lloyd and Safar 1945:Figure 30).

5m Oven

0 Figure 8. Extended household with a more planned appear- Figure 9. Extended household with a more planned appear- ance from Level IV at Hassuna (redrawn from Lloyd and ance from Level V at Hassuna (redrawn from Lloyd and Safar 1945:Figure 31). Safar 1945:Figure 32).

5 m 5m

428 [Vol. 67, No. 3, 2002

THE ORIGINS OF THE VILLAGE REVISITED

division in this household as the long, unbroken east- west wall that bisects it. South of that wall lay a series of elongated rooms, the largest of which had two storage bins and was considered by the excava- tors to be a court.

Village Density. The stratigraphic sequence at Hassuna suggests that pressure to create extended households preceded any formalization of the ground plan. The creation of such residences also has impli- cations for increasing village population density. Assuming that Lloyd and Safar's 500-m2 exposure is representative of the entire site, we can estimate the density of the Level Ic village as somewhere between 90 and 200 persons per hectare. With the

haphazard growth of extended households like those of Level III, estimates range from 200 persons (Naroll's method) to 250 persons (Wright's method) per ha. With the planned extended households of Level V, our estimates reach 280 persons (Naroll) to 400 persons (Wright) per ha. Whether or not one

accepts the actual estimates-calculated with diffi-

culty from fragmentary ground plans-it is clear that planned, extended family households can produce much higher densities.

By 5000 B.C. (uncalibrated), the village of Choga Mami in eastern Iraq had even more standardized and symmetrical residences of up to 12 rooms, neatly arranged in four rows of three (Oates 1969).

Extended Households in Mesoamerica

Most houses in early Mesoamerican villages were of wattle-and-daub, making them harder to find and

analyze than Near Eastern houses. After 850 B.C. (uncalibrated), however, elite families began increas- ingly to build adobe houses, often over a foundation of field stones. From that point on the growth of extended households becomes easier to document, as we see in the following examples from Puebla and Oaxaca, Mexico.

Name: Llano Perdido Location: Near Dominguillo in the southern Caniada de Cuicatlan, Oaxaca. The elevation is about 700 m, and the setting is arid tropical thorn forest. Date: Perdido phase, 600-200 B.C. (uncalibrated) Excavators: Spencer and Redmond (1997:Chapter 7) Description: Llano Perdido covers 2.25 ha and is considered a secondary center, part of a chiefdom whose primary center was Site Cs 19. The commu-

nity was organized into four large residential com- pounds, each measuring 30-40 m on a side and sep- arated from other compounds by about 25 m of open space. Within each compound there seems to have been a series of modular units, usually consisting of 4-5 small buildings surrounding a common patio. The excavators suspect that each patio group was occupied by an extended household of 10-15 peo- ple and that each compound consisted of 6-9 such households, united by shared descent. The largest res- idence in each compound is believed to have held a "lineage head" who was the highest-ranking mem- ber of the compound.

Llano Perdido is a shallow site that was aban- doned after having been burned in a raid, leaving wooden posts carbonized and the stone foundations of adobe houses intact. The compound in Area A/B was extensively excavated, revealing 18 structures arranged around three patios (Spencer and Redmond 1997:Fig. 7.2). The Southwest Patio group seems to have included the lineage head's residence (House 7) and his well-stocked tomb. It also produced a cer- emonial platform (Structure 6) and three units (Houses 8, 9, 10) that could plausibly be interpreted as chiefly storehouses.

The South Patio Group. I have chosen the South Patio Group to illustrate (Figure 10). Its occupants were presumably less highly ranked than the lineage head's family, but their residence illustrates the stan- dard module including a patio, three houses, and a likely ritual structure on a platform. The patio itself measured 48 m2 and contained a number of post- molds from probable ramadas or shaded work areas. Features 36 and 37 were large metates for outdoor grinding.

House 1 measured 15.4 m2 and had been built of adobes over a stone foundation. A single step led from the patio to the house, and postmolds nearby suggested that the entrance may have been shaded by an awning or thatched-roof extension. There was a hearth in the southwest corer of the house, accom- panied by sherds of comales or tortilla griddles.

House 2 measured 13 m2, and its walls were also of adobe over stone foundations. It contained domes- tic refuse and had been divided into two rooms of unequal size, apparently separated by a wattle-and- daub wall.

House 40, also of adobe over stone, had a step like that of House 1 and a similar pattern of exterior postmolds suggesting an awning or roof extension.

Flannery] 429

AMERICAN ANTIQUITY

5m

Figure 10. Stone wall foundations of the South Patio Group, part of the Area A/B residential compound at Llano Perdido near Dominguillo, Oaxaca. During the Perdido phase (600-200 B.C.), such patio groups were the modules from which larger residential compounds were assembled (redrawn from Spencer and Redmond 1997:Figure 7.2).

At some point a wattle-and-daub annex, called House 35, had been added to House 40; it contained ash from a cooking brazier (Feature 18) and a small "curb" of stone slabs framing some kind of work area (Feature 20).

Structure 16, a raised platform made from 6-7 courses of stones, sat directly across the patio from House 1. Some 80 cm high, it featured a stairway of perhaps 3-4 steps and had likely been topped with a ritual structure of some kind.

Economic Factors. Analyses of the flow of trade goods at Llano Perdido suggest that lineage heads were the conduits through which items like obsid- ian and marine shell reached the lower-ranked fam- ilies in their compound (Spencer 1982). Such families were not simply engaged in subsistence agri- culture, such as the growing of maize; botanical remains suggest that they were also engaged in the growing of tropical orchard crops for export to tem- perate regions like Tehuacan and the Valley of Oax- aca. Examples include the fruits of the black zapote (Diospyros digyna) and the nuts of the coyol palm (Acrocomia mexicana) (Spencer and Redmond 1997:600). Two labor-intensive activities at La Coy- otera-irrigation of tree crops for export and the con- version of marine shell into prestige goods-may

have provided additional incentives for the growth of large extended families.

Name: Tetimpa Location: 15 km west of Cholula, Puebla, on the lower slope of the Popocatepetl volcano at an ele- vation of ca. 2,350 m. Probable date: Late Tetimpa phase, 50 B.C.-A.D. 100 (uncalibrated) Excavators: Plunket and Uruniuela (1998) Description: During the Late Tetimpa phase, many square kilometers of the slopes below Popocatepetl were occupied by maize fields and communities of modular households. The pattern of both houses and fields is remarkably well preserved below the vol- canic ash from an eruption dating to the first century A.D.

In order to prevent erosion of fine sandy soil on the sloping terrain during heavy summer rains, farm- ers at Tetimpa mounded earth around their plants, creating "sequences of linear ridges that look very similar to the furrows of modern plowed fields" (Plunket and Uruiiuela 1998:289). Households were spaced 6-86 m apart and were often bordered by their furrowed fields (Figure 11). The standard occupa- tional module consisted of a low platform on which a central patio was flanked by 2-3 houses, set at right angles to one another. When families at Tetimpa needed more space, they added another entire mod- ular unit nearby.

In addition to maintaining a consistent astro- nomical orientation, Tetimpa households had a bimodal room-size distribution. Larger central houses, facing the entrance to the module, ranged from 16-17.5 m2; houses to either side of them ranged from 7.5 -9.5 m2. Individual houses were of wattle-and-daub over low stone platforms, with a simple staircase ascending from the central patio. In cases where there was no third house on a modular platform, its place was taken by a group of storage jars or a series of above-ground, mud-and-wicker storage bins, known as cuexcomates in the language of the later Aztec. The wattle of both walls and stor- age bins had been burned in situ by hot volcanic ash, providing exceptional architectural detail.

In the sector of Tetimpa known as Cruz Verde, the excavators found an extended household com- posed of at least two functionally complementary modules. Operation 12 of the household seemed to include the principal residential rooms, while Oper-

430 [Vol. 67, No. 3, 2002

THE ORIGINS OF THE VILLAGE REVISITED

Furrowed Agricultural Fields

..........................

2m

N -

Unit 2

Unit 3 (Kitchen with

/ broken pots)

Figure 11. Simplified plan of Operation 10 in the Cruz Verde section of Tetimpa, Puebla. This modular group is part of an extended household which also included Operation 12 (redrawn from Plunket and Uruiiuela 1998:Figure 10).

ation 10 (less than 10 m away) had the appearance of a kitchen and storage area. I have chosen to fea- ture Operation 10 (Figure 11) because it illustrates the placement of storage bins, the density of pots in the kitchen, and the proximity of the furrowed corn- fields to the residence. Operation 10 had an atypi- cally high number of pots and storage bins for its size; it makes sense only as part of an extended house- hold, which included Operation 12 (Plunket and Urufuela 1998:298).

Tetimpa reinforces a number of principles seen in other extended-family communities: (1) its house- holds could grow by accretion, like those of Hassuna II-III; yet (2) when the villagers did add more space, it was according to a modular plan like the Patio Groups of Llano Perdido; and (3) within each

Tetimpa module there were rooms of relatively stan- dard sizes, like those of Hassuna IV-V. Tetimpa thus combines the flexibility of "growth on demand" with the formality of a stereotypic module.

Conclusions and Future Developments Over the last three decades it has become clear that sedentary life in many parts of the ancient world began with settlements of circular huts like those of the preceramic Near East. Although the timing was different from region to region, many of those early

settlements were eventually replaced by villages of

rectangular, nuclear family houses. It now appears, however, that the reasons for this

replacement of one settlement type by another are too varied for a single model to explain. Included are (1) shifts in risk acceptance between the group and the nuclear family, (2) increases or decreases in

dependence on agriculture, (3) privatization of stor-

age, and possibly even (4) shifts between polyga- mous and monogamous marriage. It also appears that each of these shifts was reversible when condi- tions changed. Perhaps most intriguing is the possi- bility that two basic residential strategies may have

provided enough flexibility to adjust to a much larger set of variables.

In this paper we have also looked at a subsequent stage in village development, the growth of houses designed to hold extended families. Again, the rea- sons for this settlement change may be varied. Included are (1) the need for larger households to take on the many tasks of a mixed farming/herding economy; (2) the greater labor needs of intensive irri- gation farmers; (3) a response to the dispersed field systems that result from communal land clearance, followed by division of fields among the partici- pants; and (4) the increased size of elite households who seek to support and direct the work of craft spe-

Flannery] 431

.................?

................

................'

................

................

................

................

..........

..........

..........

.. . . .

AMERICAN ANTIQUITY

cialists. Once again, a single, basic settlement type- the village of extended households-seems to have been flexible enough to respond to a diverse set of variables.

In many parts of the ancient world, there was to be yet another stage in community development: economic specialization, not just at the level of the extended family, but at the level of the residential ward. Archaeological sites on the coast of Peru even- tually came to have barrios of farmers, fishermen, weavers, potters, and metalworkers. Classic Mesoamerican cities like Teotihuacan had large apartment compounds where specialized potters, or figurine makers, or obsidian workers, or mask assem- blers lived and worked together. In Mesopotamia, specialists in fine pottery began to paint their prod- ucts with identifying "potter's marks." Early cities near the Euphrates are believed to have had wards of farmers, herders, and fishermen. Unfortunately, there is no space to investigate that later stage of res- idential strategy here. It deserves an essay all its own-perhaps on the thirtieth anniversary of this article?

Acknowledgments. I thank editor Timothy Kohler, without whose request this article would never have been written. The advice of Raymond Kelly and four anonymous reviewers

greatly improved the manuscript. Charles Spencer and Elsa Redmond gave me a tour of Llano Perdido, and Patricia Plunket and Gabriela Urufiuela guided me around Tetimpa. Antonio Sagona called my attention to the architectural transi- tion in the Trans-Caucasus, Carla Sinopoli called my attention to the Deccan sequence, and Tim Kohler provided me with no end of data from the American Southwest. All illustrations are the work of John Klausmeyer.

References Cited Bar-Yosef, 0., and E R. Valla (editors)

1991 The Natufian Culture in the Levant. International Mono- graphs in Prehistory, Archaeological Series No. 1. Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Binford, L. R. 1983 Working atArchaeology. Academic Press, New York.

Braidwood, R. J., L. Braidwood, J. G. Smith, and C. Leslie 1952 Matarrah: A Southern Variant of the Hassunan Assem-

blage, Excavated in 1948. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 11:1-75.

Brunton, G., and G. Caton-Thompson 1928 The Badarian Civilisation and Prehistoric Remains

near Badari. Quaritch, London. Byrd, B. F

1994 Public and Private, Domestic and Corporate: The Emer- gence of the Southwest Asian Village. American Antiquity 59:639-666.

Cook, S. F, and R. F Heizer 1968 Relationships among Houses, Settlement Areas, and

Population in Aboriginal California. In Settlement Archae-

ology, edited by K. C. Chang, pp. 79-116. National Press Books, Palo Alto, California.

Dhavalikar, M. K. 1988 The First Farmers of the Deccan. Ravish Publishers,

Pune, India. Flannery, K. V.

1972 The Origins of the Village as a Settlement Type in Mesoamerica and the Near East: A Comparative Study. In Man, Settlement and Urbanism, edited by P. J. Ucko, R. Tringham, and G. W. Dimbleby, pp. 23-53. Duckworth, London.

Flannery, K. V., and J. Marcus 1983 Urban Mitla and Its Rural Hinterland. In The Cloud Peo-

ple: Divergent Evolution of the Zapotec and Mixtec Civi- lizations, edited by K. V. Flannery and J. Marcus, pp. 295-300. Academic Press, New York.

Garrod, D. A. E., and D. M. Bate 1937 The Stone Age of Mount Carmel, Vol. 1. Clarendon

Press, Oxford. Gremliza, F. G. L.

1962 Ecology and Endemic Diseases in the Dez Irrigation Pilot Area: A Report to the Khuzestan Water and Power Authority and Plan Organization of Iran. Development Resource Corporation, New York.

Gross, G. T. 1992 Subsistence Change and Architecture: Anasazi Store-

rooms in the Dolores Region, Colorado. In Research in Eco- nomic Anthropology, Supplement No. 6, pp. 241-265. JAI Press, Stamford, Connecticut.

Kelly, R. C. 2000 Warless Societies and the Origin of War. University of

Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. Kohler, T. A.

1993 News from the Northern American Southwest: Prehis- tory on the Edge of Chaos. Journal of Archaeological Research 1:267-321.

Kramer, C. 1979 An Archaeological View of a Contemporary Kurdish

Village: Domestic Architecture, Household Size, and Wealth. In Ethnoarchaeology: Implications of Ethnography for Archaeology, edited by C. Kramer, pp. 139-163. Columbia University Press, New York.

Kuijt, I. (editor) 2000 Life in Neolithic Farming Communities: Social Orga-

nization, Identity, and Differentiation. Kluwer Academic/Plenum, New York.

LeBlanc, S. 1971 An Addition to Naroll's Suggested FloorArea and Set-

tlement Population Relationship. American Antiquity 36:210-212.

Lloyd, S., and F Safar 1945 Tell Hassuna. Journal of Near Eastern Studies

4:255-289. Marcus, J., and K. V. Flannery

1996 Zapotec Civilization: How Urban Society Evolved in Mexico's Oaxaca Valley. Thames and Hudson, London and New York.

Merpert, N. Y, and R. M. Munchaev 1993 Yarim Tepe I. In The Early Stages of the Evolution of

Mesopotamian Civilization, edited by N. Yoffee and J. J. Clark, pp. 73-114. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Murdock, G. P., and S. Wilson 1972 Settlement Patterns and Community Organization:

Cross-cultural Codes. Ethnology 11:254-295. Naroll, R.

1962 FloorArea and Settlement Population. AmericanAntiq-

432 [Vol. 67, No. 3, 2002

THE ORIGINS OF THE VILLAGE REVISITED

uity 27:587-589. Oates, J.

1969 Choga Mami 1967-68: A Preliminary Report. Iraq 31:115-152.

O'Connell, J. F 1987 Alyawara Site Structure and its Archaeological Impli-

cations. American Antiquity 52:74-108. Plog, S.

1990 Agriculture, Sedentism, and Environment in the Evo- lution of Political Systems. In The Evolution of Political Sys- tems: Sociopolitics in Small-Scale Sedentary Societies, edited by S. Upham, pp. 177-202. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Plunket, P., and G. Uruiuela 1998 Preclassic Household Patterns Preserved underVolcanic

Ash at Tetimpa, Puebla, Mexico. Latin American Antiquity 9:287-309.

Robbins, M. C. 1966 House Types and Settlement Patterns: An Application

of Ethnology to Archaeological Interpretation. Minnesota Archaeologist 28:3-26.

Rollefson, G. 1997 Changes in Architecture and Social Organization at

Neolithic 'Ain Ghazal. In Prehistory of Jordan II, edited by H. Gebel, Z. Kafafi, and G. Rollefson, pp. 287-307. Ex Ori- ente, Berlin.

Sagona, A. G. 1993 Settlement and Society in Late Prehistoric Trans-Cau-

casus. In Between the Rivers and Over the Mountains, edited by M. Frangipane, H. Hauptmann, M. Liverani, P. Matthiae, and M. Mellink, pp. 453-474. Universita di Roma "La Sapienza," Rome.

Sahlins, M. D. 1962 Moala: Culture and Nature on a Fijian Island. The Uni-

versity of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. Schmieder, O.

1930 The Settlements oftheTzapotec andMije Indians, State of Oaxaca, Mexico. University of California Publications in Geography IV. Berkeley.

Soffer, O. 1985 The Upper Paleolithic of the Central Russian Plain.

Academic Press, New York. Spencer, C. S.

1982 The Cuicatldn Cahada and Monte Albdn: A Study of Primary State Formation. Academic Press, New York.

Spencer, C. S., and E. M. Redmond 1997 Archaeology of the Canada de Cuicatldn, Oaxaca.

Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Nat- ural History, No. 80. New York.

Stekelis, M., and T. Yizraely 1963 Excavations at Nahal Oren: Preliminary Report. Israel

Exploration Journal 13:1-12.

Ucko, P. J., R. Tringham, and G. W. Dimbleby (editors) 1972 Man, Settlement and Urbanism. Duckworth, London.

Watson, P. J. 1979 Archaeological Ethnography in Western Iran. Viking

Fund Publications in Anthropology No. 57. University of Ari- zona Press, Tucson.

Whiting, J. W. M., and B. Ayres 1968 Inferences from the Shape of Dwellings. In Settlement

Archaeology, edited by K. C. Chang, pp. 117-133. National Press Books, Palo Alto.

Wiessner, P. 1982 Beyond Willow Smoke and Dogs' Tails: A Comment

on Binford's Analysis of Hunter-gatherer Settlement Sys- tems. American Antiquity 47:171-178.

Wills, W. H. 1992 Plant Cultivation and the Evolution of Risk-prone

Economies in the Prehistoric American Southwest. In Tran- sitions to Agriculture in Prehistory, edited by A. B. Gebauer andT. D. Price, pp. 153-176. Monographs inWorldArchae- ology No. 4. Prehistory Press, Madison, Wisconsin.

Winterhalder, B. 1990 Open Field, Common Pot: Harvest Variability and Risk

Avoidance in Agricultural and Foraging Societies. In Risk and Uncertainty in Tribal and Peasant Economies, edited by E. Cashdan, pp. 67-88. Westview Press, Boulder, Col- orado.

Woodbur, J. C. 1972 Ecology, Nomadic Movement and the Composition of

the Local Group among Hunters and Gatherers: An East African Example and Its Implications. In Man, Settlement and Urbanism, edited by P. J. Ucko, R. Tringham, and G. W. Dimbleby, pp. 193-206. Duckworth, London.

Yellen, J. E. 1977 ArchaeologicalApproaches to the Present: Modelsfor

Reconstructing the Past. Academic Press, New York.

Notes 1. At Yarim Tepe I in northern Iraq, Merpert and

Munchaev (1993) found several tholoi in levels of the Hassunan period. In their opinion, these circular structures "cannot be classed as dwellings either by their size, form, or contents" (Merpert and Munchaev 1993:95); they consider them to be "connected with burial practices" (1993:95). It is

possible that northern Mesopotamia represents a second

region where, as in the Southwest U.S., some round struc- tures became associated with ritual after rectangular houses

developed.

Received October 17, 2001; Revised February 15, 2002; Accepted February 19, 2002.

Flannery] 433

![Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964) Flannery O’Connor ENGL 2030 Experience of Literature: Fiction [Lavery]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/551b6983550346a10a8b457c/flannery-oconnor-1925-1964-flannery-oconnor-engl-2030-experience-of-literature-fiction-lavery.jpg)