Results of Interventional Treatment of Stress Positive Coronary Artery Disease

-

Upload

umar-adamu -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

2

Transcript of Results of Interventional Treatment of Stress Positive Coronary Artery Disease

opw

M

dtdshgmap

R2

A

0d

Results of Interventional Treatment of Stress Positive CoronaryArtery Disease

Umar Adamu, MDa, Daniela Knollmann, MDb, Wael Alrawashdeha, Bader Almutairia,Verena Deserno, MSca, Eduard Kleinhans, MDb, Wolfgang Schäfer, MDb, and

Rainer Hoffmann, MDa,*

The aim of this study was to define the impact of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)including stenting in patients with stress-positive stable coronary artery disease on long-term prognosis and symptoms. A group of 1,018 patients were identified from the angio-graphic and single-photon emission computed tomographic (SPECT) databases (techne-tium-99m sestamibi or tetrofosmin at rest and during stress) January 1, 2000, to December31, 2003, to have significant coronary artery disease (>50% diameter stenosis on quanti-tative coronary angiography) and positive SPECT findings. Two hundred sixty-six patientswere medically treated. Seven hundred fifty-two patients with positive SPECT findingswho underwent PCI were matched to 266 patients of similar age, gender, number andlocation of stenotic arteries, left ventricular function, and size of SPECT perfusion defectwho underwent medical treatment. Clinical events (death, nonfatal myocardial infarction,and revascularization) as well as clinical symptoms (angina or dyspnea, Canadian Car-diovascular Society class II to IV) were determined after a follow-up period of 6.4 � 1.2years. In 524 of the 532 patients (98%), clinical follow-up was obtained. There were nodifferences between the PCI and medical groups in the frequencies of death (13.5% vs10.9%) and myocardial infarction (5.3% vs 5.6%) during follow-up. PCI patients had morerevascularization procedures <1 year after choice of treatment modality (14.7% vs 6.0%,p <0.002). During the subsequent follow-up period (>1 year), the 2 groups did not differin the frequency of revascularization procedures. At the end of follow-up, patients in thePCI group complained less frequently of angina pectoris (38% vs 49%, p � 0.014). Inconclusion, in patients with stress-positive stable coronary artery disease, PCI includingstenting did not reduce mortality or rate of nonfatal myocardial infarction. The PCI groupcomplained less frequently of angina pectoris at long-term follow-up. © 2010 Elsevier Inc.

All rights reserved. (Am J Cardiol 2010;105:1535–1539)iitoTt

wcmf(vSivow

paait

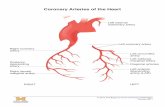

The aim of this matching study was to define the impactf percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stentlacement on long-term prognosis and symptoms in patientsith stable stress-positive coronary artery disease (CAD).

ethods

The angiographic and myocardial perfusion scintigraphicatabases of the University of Aachen were matched for theime period from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2003, toefine patients with nonacute significant CAD (diametertenosis �50% on quantitative coronary angiography) whoad positive stress single-photon emission computed tomo-raphic (SPECT) results and were subsequently treated withedical therapy or PCI including stent placement. The

ngiographic database included 20,384 patients during thiseriod, and the myocardial perfusion scintigraphic database

aMedical Clinic I and bDepartment of Nuclear Medicine, UniversityWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany. Manuscript received November 8,009; revised manuscript received and accepted January 5, 2010.

Dr. Adamu is supported by a grant from Deutscher Akademischerustausch Dienst, Bonn, Germany.

*Corresponding author: Tel: 49-2418088468; fax: 49-2418082303.

mE-mail address: [email protected] (R. Hoffmann).002-9149/10/$ – see front matter © 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.oi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.01.010

ncluded 4,903 patients. A total of 1,018 stable patients weredentified to have positive stress myocardial perfusion scin-igraphic findings and significant CAD on quantitative cor-nary angiography and were treated medically or by PCI.wo hundred sixty-six patients were treated using medical

herapy.These 266 patients were matched against 752 patients

ith positive SPECT findings and PCI as treatment. Patientharacteristics and angiographic and SPECT findings wereatched with the medical treatment group, considering the

ollowing parameters in sequential selection: gender, age�1 year), number and location of the stenotic vessel, leftentricular function (ejection fraction �5%), and size ofPECT perfusion defect. Patients with previous myocardial

nfarctions or coronary revascularization (�30 days), val-ular heart disease, left bundle branch block, or cardiomy-pathy were excluded from the analysis. Thus, 532 patientsere included in the final study group.Quantitative coronary angiography was performed in all

atients in whom coronary lesions were defined by visualnalysis. Analysis was performed using a computer-assistedutomated edge detection system (Philips Easy Vision; Phil-ps Medical Systems, Andover, Massachusetts). The inves-igator analyzing the angiograms was blinded to clinical and

yocardial perfusion scintigraphic data. The guiding cath-www.AJConline.org

ededda

MpTsrftetmiTf(tobue6z

asltdsas(wd2pomttswbwa

ntAwAtgpo

bgcocd

oDwmcpelmPhtdttccFldYt

Ctwc

TB

V

MAA

PPPN

DAHE

1536 The American Journal of Cardiology (www.AJConline.org)

ter was used as a scaling device. The minimal luminaliameter and the proximal and distal reference vessel diam-ters were determined to allow calculation of the percentageiameter stenosis. Significant coronary artery stenosis wasefined as �50% diameter stenosis on quantitative coronaryngiography.

Stress and rest studies were done in a 1-day (1 � 300Bq followed by 1 � 750 MBq) or a 2-day (2 � 450 MBq)

rotocol using technetium-99m tetrofosmin or sestamibi.hree hundred thirty-four patients were stressed by exercisetress and 198 patients by pharmacologic stress using dipy-idamole. In case of exercise stress, technetium-99m tetro-osmin or sestamibi was injected during maximal or symp-om-limited exercise, with the workload increased by 25 Wvery 2 minutes and at rest. In case of dipyridamole stress,echnetium-99m tetrofosmin or sestamibi was injected 3inutes after the completion of a 4-minute dipyridamole

nfusion (0.56 mg dipyridamole/kg body weight) and at rest.he SPECT protocol usually started with the stress portion,

ollowed by SPECT imaging at rest either the same day1-day protocol, n � 244) or a few days later (2-day pro-ocol, n � 288). Antianginal drugs were stopped on the dayf the stress test, and � blockers were discontinued 2 daysefore the test. Acquisition was done in a 64 � 64 matrixsing a Siemens MULTISPECT 3 triple-head gamma cam-ra (Siemens Gammasonics, Inc., Hoffman Estates, Illinois)0 minutes after tracer injection, with 60 views using aoom factor of 1.23.

SPECT images were evaluated by visual and quantitativenalysis. For visual analysis, myocardial technetium-99mestamibi uptake was visually assessed on the short-axis andong-axis slices obtained at rest and peak stress. For quan-itative analysis, using Quantitative Perfusion SPECT (Ce-ars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California), thetress and rest data sets of all patients were analyzed in fullyutomatic operation mode. The summed stress score (SSS),ummed rest score (SRS), and summed difference scoreSDS) values were calculated on the basis of comparisonith the corresponding gender-specific institutional normalatabase. The left ventricular myocardium was divided into0 segments1,2 and scored for the extent and severity oferfusion abnormalities in each segment during stress and restn a 5-point scale: 0 � normal, 1 � slight reduction, 2 �oderate reduction, 3 � severe reduction of radiotracer up-

ake, and 4 � no radiotracer uptake. The SSS and SRS arehe sums of scores in these 20 segments.1,3–5 In case theegmental rest score had a higher value than the stress score, itas assigned the stress score value. The sum of the differencesetween each of the 20 segments on the stress and rest imagesas defined as the SDS, also called the reversibility score. It is

n index of jeopardized myocardium.In case of medical treatment, � receptor blockers and

itrates were administered to obtain a symptom-free condi-ion. PCI was performed according to standard techniques.ll patients were treated using bare-metal stents, whichere standard devices at the time of the index procedure.nticoagulation during PCI was accomplished with unfrac-

ionated heparin per standard protocol. Patients receivedlycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors according to usualrotocol with abciximab or tirofiban at the discretion of the

perator. All patients were treated with aspirin 100 mg/day Mefore PCI and indefinitely afterward. Clopidogrel wasiven in a loading dose of 300 or 600 mg before PCI andontinued at 75 mg/day for 4 weeks after PCI. The successf PCI as seen on angiography was defined as normaloronary artery flow and �20% stenosis in the luminaliameter after coronary stent implantation.

Clinical follow-up information on patient survival wasbtained in all patients by dedicated research personnel.ata were obtained by telephone contact with the patients orith their immediate relatives and complemented by infor-ation obtained from the patients’ general physicians or

harts from recurrent hospital admissions. In case neitheratients nor relatives could be contacted and patients’ gen-ral physicians did not know about the patients’ outcomes,ocal population registries were contacted to obtain infor-ation about patients’ possible death or current locations.atients were followed for �4.5 years (mean 6.4 � 1.2) forard events, defined as death, nonfatal myocardial infarc-ion, and myocardial revascularization procedure. Myocar-ial infarction was verified by hospital documentation, andhe diagnosis was based on the accepted criteria of charac-eristic chest pain and electrocardiographic and enzymehanges. In addition, a composite of death, nonfatal myo-ardial infarction, bypass surgery, or PCI was evaluated.urthermore, using a standard medical questionnaire, the

evel of current limitations due to angina pectoris by Cana-ian Cardiovascular Society class and dyspnea by Nework Heart Association class were determined at the end of

he follow-up period.Values are expressed as mean � SD or as percentages.

ategorical variables were compared using the chi-squareest or Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test, and continuous variablesere compared using Student’s t test. Estimates of the

umulative event rate were calculated using the Kaplan-

able 1aseline clinical characteristics

ariable MedicalTreatment(n � 266)

PCI(n � 266)

p Value

en 202 (76%) 202 (76%) 1.000ge (years) 64.9 � 9.4 65.0 � 9.5 0.915ngina pectoris (Canadian

Cardiovascular Societyclass II or III)

226 (85%) 231 (87%) 0.621

revious myocardial infarction 141 (53%) 114 (43%) 0.026revious PCI 74 (28%) 80 (30%) 0.614revious coronary bypass 56 (21%) 61 (23%) 0.474umber of narrowed coronary

arteries1.96 � 0.81 1.91 � 0.76 0.212

1-vessel disease 95 (36%) 92 (35%) 0.2012-vessel disease 88 (33%) 106 (40%)3-vessel disease 83 (31%) 67 (25%)iabetes mellitus 59 (22%) 69 (26%) 0.199rterial hypertension* 218 (82%) 215 (81%) 0.723yperlipidemia† 178 (67%) 175 (66%) 0.655jection fraction (%) 57 � 4 57 � 5 0.475

Data are expressed as number (percentage) or as mean � SD.* Arterial pressure �160/90 mm Hg or medical treatment.† Serum cholesterol �240 mg/dl or medical treatment.

eier method, and the primary efficacy of PCI, compared to

otafhfdav�

R

(cPPvmi

Ttmci0t

T

girn

fmuadfitgacw(mC

TA

V

MRDL

TS

V

ISA

SSS

TF

V

DMR

R

A

D

C

Fl

1537Coronary Artery Disease/PCI in Stress-Positive SPECT

ptimal medical therapy, was assessed using log-rank sta-istics. The effect of PCI, as measured by the hazard rationd its associated 95% confidence interval, was estimatedor the cumulative event rate using the Cox proportional-azards model. Cox proportional-hazards analysis was per-ormed to identify univariate and multivariate predictors ofeath and events during follow-up. Included variables werege, gender, treatment modality, severity of CAD, the leftentricular ejection fraction, SSS, and SRS. A p value0.05 was considered statistically significant.

esults

A total of 532 patients were included in the analysisTable 1). In 524 of these patients (98%), clinical follow-upould be obtained. There were no differences between theCI and medical treatment groups in age, gender, history ofCI, coronary bypass grafting, number of diseased coronaryessels, cardiac risk factors, and ejection fraction. In theedical group, more patients had histories of myocardial

nfarctions.Results of quantitative coronary angiography are listed in

able 2. Although the reference diameter was similar be-ween the medical treatment group and the PCI group, theinimal luminal diameter was smaller in the PCI group

ompared to the medical treatment group. This resulted alson greater diameter stenosis in the PCI group. A mean of 1.1 �.3 vessels were treated using PCI in the interventionalreatment group.

Results of myocardial perfusion scintigraphy are listed in

able 2ngiographic baseline characteristics

ariable MedicalTreatment(n � 266)

PCI(n � 266)

p Value

inimal luminal diameter (mm) 0.67 � 0.53 0.37 � 0.20 �0.001eference diameter (mm) 2.87 � 0.96 2.69 � 0.82 0.183iameter stenosis (%) 78 � 15% 86 � 7% �0.001esion length (mm) 10.1 � 4.9 10.6 � 4.6 0.324

Data are expressed as mean � SD.

able 3tress and rest myocardial perfusion scintigraphy

ariable Medical Treatment(n � 266)

PCI(n � 266)

p Value

schemia 100% 100% 1.000car 62% 56% 0.132rea of ischemiaApex 18% 24% 0.083Anterior 31% 40% 0.027Septal 19% 22% 0.325Inferior 28% 24% 0.290Posterior 29% 33% 0.147Lateral 23% 17% 0.070ummed stress score 12.8 � 9.5 14.0 � 10.1 0.127ummed rest score 7.7 � 8.4 7.3 � 8.6 0.554ummed difference score 5.2 � 3.6 6.7 � 5.9 0.062

Data are expressed as percentage or as mean � SD.

able 3. The frequency of scar was similar between the 2 i

roups. There were some differences in the distribution ofschemic areas. The overall extent of perfusion deficits atest and with stress as defined by SSS, SRS, and SDS wasot different between the 2 treatment groups.

There were no differences in death and myocardial in-arction (Table 4) between the 2 treatment groups. Theortality rate was 2.0% per year for the total patient pop-

lation. Kaplan-Meier survival curves did not demonstrateny difference in survival between the 2 treatment groupsuring the complete follow-up period (Figure 1). Within therst year after choice of treatment modality, revasculariza-

ion procedures were performed more frequently in the PCIroup than in the medical treatment group. More than 1 yearfter the choice of treatment strategy, revascularization pro-edures were done at similar rate for the 2 groups. Thereas a higher rate of patients complaining of angina pectoris

Canadian Cardiovascular Society class II to IV) in theedical treatment group than in the PCI group (Table 4).onsidering the total study population, patients dying dur-

able 4ollow-up events

ariable MedicalTreatment(n � 266)

PCI(n � 266)

pValue

eath 29 (11%) 36 (14%) 0.431yocardial infarction 15 (6%) 14 (5%) 1.000ecurrent revascularization within 1

year16 (6%) 39 (15%) 0.002

ecurrent revascularization after 1year

48 (18%) 50 (19%) 0.914

ngina pectoris (Canadian CardiovascularSociety class II–IV) at follow-up

116 (49%) 87 (38%) 0.014

yspnea (New York Heart Associationclass II–IV) at follow-up

114 (48%) 111 (48%) 0.955

oncomitant medications at follow-upAngiotensin-converting enzyme

inhibitors141 (53%) 152 (57%) 0.407

Angiotensin II receptor blockers 27 (10%) 24 (9%) 0.774� blockers 207 (78%) 197 (74%) 0.334Nitrates 82 (31%) 59 (22%) 0.033Statins 146 (55%) 138 (52%) 0.895

igure 1. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with PCI (continuousine) and for patients with medical therapy (interrupted line).

ng follow-up had higher SSS compared to patients who

rh

((Swgbd

D

mpttmt

aoacppfmbogcmacfiSssltsui

brtrstA8d

hhocd

adsI(ePwCsfywAbrcpidltto

prtdhw

wcamsCtrsLpietueTddct

1538 The American Journal of Cardiology (www.AJConline.org)

emained alive (15.4 � 11.0 vs 12.6 � 9.7, p � 0.032) andigher SDS (7.2 � 6.4 vs 5.4 � 5.1, p � 0.005).

Cox proportional-hazards statistics indicated that ageper year; odds ratio 1.032, p � 0.016), the ejection fractionper percentage point; odds ratio 0.097, p � 0.023), andDS (per additional score; odds ratio 1.061, p � 0.012)ere significant predictors of death during follow-up. An-iographic results at baseline as well as choice of treatmenteing either PCI or medical therapy were not predictors ofeath during follow-up.

iscussion

This study demonstrates (1) a similarity in death andyocardial infarction rates after PCI for nonacute stress-

ositive CAD compared to medical therapy during long-erm follow-up, (2) a higher revascularization rate duringhe first year of follow-up in the PCI group compared to theedical therapy group, and (3) a high rate of anginal pain in

he medical treatment group at the end of long-term follow-up.There have been multiple studies of clinical outcomes

fter PCI compared with medical therapy.6–18 Improvedutcomes after PCI have been demonstrated in patients withcute coronary syndromes.6–9 A positive impact of PCI onlinical outcomes in patients with stable CAD is lessroved. In a meta-analysis of 11 trials including 2,950atients comparing PCI to conservative treatment, no dif-erences between the 2 treatment strategies with regard toortality, cardiac death, myocardial infarction, coronary

ypass grafting, and PCI during follow-up could be dem-nstrated.19 However, in several studies, only balloon an-ioplasty was performed. Thus, these studies do not reflecturrent standards in interventional therapy. Furthermore, inost of these studies, patients were included if they had

ngiographically proved significant coronary stenosis andlinical symptoms that were related to the angiographicndings. Definite demonstration of myocardial ischemia onPECT imaging has not been an inclusion criterion in mosttudies. The demonstration of ischemia-inducing coronarytenosis by noninvasive or invasive methods has been re-ated to impaired prognosis.1 Thus, a treatment modalityhat results in the deletion of an ischemia-inducing coronarytenosis should improve prognosis. The presented study isnique in that we considered only patients with ischemia-nducing coronary stenoses.

This study did not demonstrate a survival differenceetween the treatment groups. The higher revascularizationate in the PCI group during the first year after choice ofreatment modality should be explained by symptomaticestenosis as well as routine control angiography demon-trating significant restenosis, even in asymptomatic pa-ients, resulting in recurrent revascularization procedures.n increased rate of revascularization procedures from 6 tomonths after PCI has been reported in patients who un-

ergo routine control angiography.20–22

Patients in the medical treatment arm more frequentlyad anginal pain at the end of the follow-up period. Theigher rate of symptoms was also reflected by a higher ratef nitrate intake in the medical treatment arm. There areonflicting data on the impact of PCI on clinical symptoms

uring follow-up. Although a significantly higher rate ofngina-free patients in the PCI group is an accepted findinguring short-term follow-up, the impact of PCI on clinicalymptoms during long-term follow-up is much less defined.n the Swiss Interventional Study on Silent Ischemia Type IISWISSI II) randomized trial in patients with silent isch-mia, the maximal workload was significantly higher in theCI group, while the frequency of ST-segment depressionas significantly lower, even at 4-year follow-up.13 In thelinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggres-

ive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial, the rate of angina-ree patients was different at 1 and 3 years but not at 5ears.12 In this trial, optimal medical therapy was aimed for,ith aggressive therapy to lower low-density lipoprotein.ggressive medical therapy including lifestyle changes haseen shown to significantly improve physical fitness andeduce angina frequency.23 Thus, efforts to optimize medi-al therapy are likely to reduce the advantage of PCI onatient symptoms during follow-up. In our study, a signif-cant advantage of PCI on angina-free presentation could beemonstrated 6.4 � 1.2 years after the index procedure. Aess aggressive risk reduction as well as less intensive an-ianginal therapy, which reflect the common clinical prac-ice, are possible reasons for the ongoing advantage of PCIn clinical symptoms even at long-term follow-up.

Age, the ejection fraction, and SDS were found to beredictors of death during follow-up, while angiographicesults and treatment modality were not found to be predic-ive. This result agrees with the finding that patients whoied during follow-up were found to have significantlyigher initial SSS and SDS values compared with patientsho remained alive.This was not a randomized prospective study. Instead, it

as a retrospective matching analysis. Thus, no data onlinical symptoms during the complete follow-up period arevailable. There were no special efforts taken to optimizeedical therapy in any group. In particular, the frequency of

tatin therapy was not as high as in other studies, such asOURAGE. This relates also to cardiac risk factor reduc-

ion and lifestyle modulation by patients. However, this mayeflect the common clinical situation in which no specialupport with regard to lifestyle modulation is available.ifestyle modulations were not assessed in the study. Clo-idogrel was given for 4 weeks after PCI including themplantation of a bare-metal stent. This was adequate forlective PCI including implantation of a bare-metal stent athe time of intervention. Other antiplatelet therapy protocolssed today with drug-eluting stents may alter follow-upvent rates. Medication use was recorded only at follow-up.here is no information on adherence to current guidelinesuring the total follow-up period. In the current era ofrug-eluting stents, follow-up event rates may be differentompared with the exclusive use of bare-metal stents as inhe study.

1. Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Shaw LJ, Kiat H, Cohen I, Cabico JA,Friedman J, Diamond GA. Incremental prognostic value of myocardialperfusion single photon emission computed tomography for the pre-diction of cardiac death: differential stratification for risk of cardiacdeath and myocardial infarction. Circulation 1998;97:535–543.

2. Hida S, Chikamori T, Tanaka H, Igarashi Y, Hatano T, Usui Y, Miyagi

M, Yamashina A. Diagnostic value of left ventricular function afteradenosine triphosphate loading and at rest in the detection of multi-

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

1539Coronary Artery Disease/PCI in Stress-Positive SPECT

vessel coronary artery disease using myocardial perfusion imaging.J Nucl Cardiol 2009;16:20–27.

3. Bermann DS, Xingping K, Nishina H, Slomka PJ, Shaw LJ, HayesSW, Cohen I, Friedman JD, Gerlach J, Germano G. Diagnostic accu-racy of gated Tc-99m sestamibi stress myocardial perfusion SPECTwith combined supine and prone acquisitions to detect coronary arterydisease in obese and nonobese patients. J Nucl Cardiol 2006;13:191–201.

4. Sharir T, Xingping K, Germano G, Bax JJ, Shaw LJ, Gransar H, CohenI, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Berman DS. Prognostic value of poststressleft ventricular volume and ejection fraction by gated myocardialperfusion SPECT in women and men: gender-related differences innormal limits and outcomes. J Nucl Cardiol 2006;13:495–506.

5. Lima RS, De Lorenzo A, Soares AJ. Relation between postexerciseabnormal heart rate recovery and myocardial damage evidenced bygated single-photon emission computed tomography. Am J Cardiol2006;97:1452–1454.

6. Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intra-venous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quan-titative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet 2003;361:13–20.

7. Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, Demopoulos LA, Vicari R, Frey MJ,Lakkis N, Neumann FJ, Robertson DH, DeLucca PT, DiBattiste PM,Giboson CM, Braunwald E. Comparison of early invasive and con-servative strategies in patients with unstable coronary syndromestreated with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor tirofiban. N Engl J Med2001;344:1879–1887.

8. Fragmin and Fast Revascularisation During Instability in CoronaryArtery Disease Investigators. Invasive compared with non-invasivetreatment in unstable coronary artery disease: FRISC II prospectiverandomized multicenter study. Lancet 1999;354:708–715.

9. Mehta SR, Cannon CP, Fox KA, Wallentin L, Boden WE, Spacek R,Widimsky P, McCullough PA, Hunt D, Braunwald E, Yusuf S. Rou-tine vs selective invasive strategies in patients with acute coronarysyndromes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA2005;293:2908–2917.

0. Parisi AF, Folland ED, Hartigan P. A comparison of angioplasty withmedical therapy in the treatment of single-vessel coronary artery dis-ease. N Engl J Med 1992;326:10–16.

1. Bucher HC, Hengstler P, Schindler C, Guyatt GH. Percutaneous trans-luminal coronary angioplasty versus medical treatment for non-acutecoronary heart disease: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.BMJ 2000;321:73–77.

2. Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, Hartigan PM, Maron DJ, KostukWJ, Knudtson M, Dada M, Casperson P, Harris CL, Chaitman BR,Shaw L, Gosselin G, Nawaz S, Title LM, Gau G, Blaustein AS, BoothDS, Bates ER, Spertus JA, Berman DS, Mancini GBJ, Weintraub WS.Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary arterydisease. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1503–1516.

3. Erne P, Schoenenberger AW, Burckhardt D, Zuber M, Kiowski W,Buser PT, Dubach P, Resink TJ, Pfisterer M. Effects of percutaneouscoronary interventions in silent ischemia after myocardial infarction.The SWISSI II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007;297:1985–

1991.4. Coronary angioplasty versus medical therapy for angina: the SecondRandomised Intervention Treatment of Angina (RITA-2) trial. Lancet1997;350:461–468.

5. Zeymer U, Uebis R, Vogt A, Glunz HG, Vohringer HF, Harmjanz D,Neuhaus KL; ALKK-Study Group. Randomized comparison of per-cutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and medical therapy instable survivors of acute myocardial infarction with single vesseldisease: a study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende KardiologischeKrankenhausarzte. Circulation 2003;108:1324–1328.

6. Gibbons RJ, Abrams J, Chatterjee K, Daley J, Deedwania PC, DouglasJS, Ferguson TB Jr, Fihn SD, Fraker TD Jr, Gardin JM, O’Rourke RA,Pasternak PC, Williams SV. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for themanagement of patients with chronic stable angina—summary article:a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart As-sociation Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Man-agement of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina). J Am Coll Cardiol2003;41:159–168.

7. Smith SC Jr, Feldman TE, Hirshfeld JW Jr, Jacobs AK, Kern MJ, KingSB III, Morrison DA, O’Neil WW, Schaff HV, Whitlow PL, WilliamsDO, Antman EM, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V,Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL,Riegel B. ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneouscoronary intervention—summary article: a report of the AmericanCollege of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force onPractice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Updatethe 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention). Circu-lation 2006;113:156–175.

8. Henderson RA, Pocock SJ, Clayton TC, Knight R, Fox KA, Julian DG,Chamberlain DA. Seven-year outcome in the RITA-2 trial: coronaryangioplasty versus medical therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1161–1170.

9. Katritsis DG, Ioannidis JPA. Percutaneous coronary intervention ver-sus conservative therapy in nonacute coronary artery disease. A meta-analysis. Circulation 2005;111:2906–2912.

0. Serruys PW, de Jaeger P, Kiemeneij F, Macaya C, Rutsch W, Heyn-drickx G, Emanuelsson H, Marco J, Legrand V, Materne P, Belardi J,Sigwart U, Colombo A, Goy JJ, van den Heuvel P, Delcan J, MorelMA, for the Benestent Study Group. A comparison of balloon-expand-able-stent implantation with balloon angioplasty in patients with cor-onary heart disease. N Engl J Med 1994;331:489–495.

1. Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, Fajadet J, Ban Hayashi E, PerinM, Colombo A, Schuler G, Barragan P, Guagliumi G, Molnar F,Falotico R. A randomized comparison of sirolimus-eluting stent witha standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1173–1180.

2. Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, Fitzgerald PJ, Holmes DR,O’Shaughnessy C, Caputo RP, Kereiakes DJ, Williams DO, TeirsteinPS, Jaeger JL, Kuntz RE. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standardstents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N EnglJ Med 2003;349:1315–1323.

3. Hambrecht R, Walther C, Mobius-Winkler S, Gielen S, Linke A,Conradi K, Erbs S, Kluge R, Kendziorra K, Sabri O, Sick P, SchulerG. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty compared with exercise trainingin patients with stable coronary artery disease: a randomized trial.

Circulation 2004;109:1371–1378.