Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer Search

Transcript of Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer Search

This article was downloaded by: [73.152.126.154] On: 21 December 2017, At: 18:46Publisher: Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS)INFORMS is located in Maryland, USA

Management Science

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://pubsonline.informs.org

Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous ConsumerSearchJuncai Jiang, Nanda Kumar, Brian T. Ratchford

To cite this article:Juncai Jiang, Nanda Kumar, Brian T. Ratchford (2017) Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer Search.Management Science 63(10):3489-3513. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2513

Full terms and conditions of use: http://pubsonline.informs.org/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used only for the purposes of research, teaching, and/or private study. Commercial useor systematic downloading (by robots or other automatic processes) is prohibited without explicit Publisherapproval, unless otherwise noted. For more information, contact [email protected].

The Publisher does not warrant or guarantee the article’s accuracy, completeness, merchantability, fitnessfor a particular purpose, or non-infringement. Descriptions of, or references to, products or publications, orinclusion of an advertisement in this article, neither constitutes nor implies a guarantee, endorsement, orsupport of claims made of that product, publication, or service.

Copyright © 2016, INFORMS

Please scroll down for article—it is on subsequent pages

INFORMS is the largest professional society in the world for professionals in the fields of operations research, managementscience, and analytics.For more information on INFORMS, its publications, membership, or meetings visit http://www.informs.org

MANAGEMENT SCIENCEVol. 63, No. 10, October 2017, pp. 3489–3513

http://pubsonline.informs.org/journal/mnsc/ ISSN 0025-1909 (print), ISSN 1526-5501 (online)

Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer SearchJuncai Jiang,a Nanda Kumar,b Brian T. Ratchfordb

aVirginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia 24061; bUniversity of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, Texas 75080Contact: [email protected] (JJ); [email protected] (NK); [email protected] (BTR)

Received: April 10, 2014Revised: April 12, 2015; November 8, 2015Accepted: December 29, 2015Published Online in Articles in Advance:August 26, 2016

https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2513

Copyright: © 2016 INFORMS

Abstract. Price-matching guarantees (PMGs) are offered in a wide array of product cat-egories in retail markets. PMGs offer consumers the assurance that, should they find alower price elsewhere within a specified period after purchase the retailer will match thatprice and refund the price difference. The goal of this study is to explain the followingstylized facts: (1) many retailers that operate both online and offline implement PMGoffline but not online; (2) the practices of PMG vary considerably across retail categories;and (3) some retailers launch specialized websites that automatically check competitors’prices for consumers after purchase. To this end, we build a sequential search modelthat endogenizes consumers’ pre- and postpurchase search decisions. We find that PMGexpands retail demand but intensifies price competition on two dimensions. PMG drivesretailers to offer deeper promotions because it increases the overall extent of consumersearch, which we call the primary competition-intensifying effect. We also find a new sec-ondary competition-intensifying effect, which results from endogenous consumer search.As deeper promotions incentivize consumers to continue price search, retailers are forcedto lower the “regular” price to deter consumers from searching. The strength of the sec-ondary competition-intensifying effect increases with the ratio of product valuation tosearch cost, which explains the variation in PMG practices online versus offline and acrossretail categories. We show that an asymmetric equilibrium exists such that one retaileroffers PMG while the other does not. In this equilibrium, the PMG retailer may benefitfrom launching a price check website to facilitate consumers’ postpurchase search.

History: Accepted by J. Miguel Villas-Boas, marketing.

Keywords: price-matching guarantees • sequential consumer search • reservation price rule • mixed pricing strategy • price-beating guarantees

1. IntroductionPrice-matching guarantees (PMGs) offer consumersthe assurance that, if they find a lower price elsewherewithin a grace period after purchase, the retailer willmatch that price. For example, Walmart promotes itsChristmas Price Guarantee by advertising that “Finda lower advertised price on a gift after you’ve boughtit? No problem. We’ll give you the price differenceon any identical, available product in a local com-petitor’s store” (Russell 2011). PMGs are pervasivein a wide array of product categories ranging fromdurable goods to supermarket perishables and fromtravel agent services to financial services. In marketswith widespread adoption of PMGs, consumers maypossess imperfect price information even at the timeof purchase. Buying with a PMG gives consumers anoption to benefit fromprice search after purchase in thehope of finding a lower price and exercising PMG. Inan effort to explore the competitive implications of thisoption, we develop a model in which some consumershave high search costs at the time of purchase, but cansearchwhen search costs are lower at some future date,if they take advantage of a PMG. Our model offers anexplanation for the stylized facts presented below.

First, retailers like Walmart, Target, Cabela’s, HomeDepot, and Kohl’s offer PMGs in their physical storesbut not on their websites. An astute reader mayargue that this could result from differences in thecompetitive structure of the online and offline en-vironment. Small, low-cost online retailers may beable to afford to charge substantially lower pricesfor select products, which erodes the profitabilityof offering PMGs online. In contrast, offline retail-ers are more predictable and have similar cost struc-tures to one another. However, online retailers candefine the “qualified” competitors in their price-matching policies to exclude competition from theselow-cost online retailers. For example, Office Depot’sonline store only matches the prices of “Staples.com,OfficeMax.com, BestBuy.com, Reliable.com, Quill.com,Sears.com, Target.com, KMart.com, Costco.com, orSamsClub.com.”1 Thus, it appears that differences incompetitive structure cannot fully explain retailers’decisions to offer PMG offline but not online. Ourstudy sheds light on factors that may explain thisphenomenon.

Second, there is ample evidence that PMG prac-tices vary considerably across retail categories. We col-lected a sample of 150 online retailers from the Top 500

3489

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017

, at 1

8:46

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Jiang, Kumar, and Ratchford: Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer Search3490 Management Science, 2017, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 3489–3513, ©2016 INFORMS

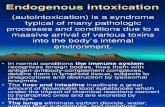

Table 1. PMG Practices Across Categories

No. of PMG No. of total % of PMGCategory retailers retailers retailers

Office supplies 5 5 100Hardware/Home 3 6 50

improvementAutomobile/Accessories 1 3 33Specialty/Nonapparel 2 6 33Health/Beauty 3 10 30Housewares/Home 2 7 29

furnishingsMass merchant 4 19 21Sporting goods 1 5 20Computer/Electronics 3 17 12Apparel/Accessories 4 38 11Othersa 0 34 0Total 28 150 19

aOthers include books/music/videos, flowers/gifts, toys/hob-bies, food/drug, and jewelry.

List® by Internet Retailer in 2010. Internet Retailer clas-sifies retailers into 15 exclusive categories. In Table 1we report the fraction of retailers in each categorythat offer PMGs.2 In the office supplies category, allfive online retailers—Staples, Office Depot, OfficeMax,Vistaprint, Shoplet—offer PMGs. However, none of theretailers in the jewelry category offers PMG. In thecomputer/electronics category, ABT, Ritz, and Crutch-field offer PMGs while others do not. Prior researchargues that the variation in PMG practices across cat-egories can be explained by the difference in the sizeof consumer segments with different search behaviors(Chen et al. 2001). However, this explanation seems lessplausible in the online setting where consumer seg-ments may not vary much across product categories.In this study we develop a theory that can explain themarket phenomenon in Table 1 even when the sizesof different consumer segments are the same acrosscategories.Third, Asda, Walmart’s operation and the second

largest supermarket chain in the United Kingdom, sup-plements its PMG with a price check website (http://www.asdapriceguarantee.co.uk/) along with a mobileapp that facilitates consumers’ postpurchase search.This website works as follows. After grocery shopping,consumers enter the receipt details on the price checkwebsite. This website then automatically checks theprices of purchased groceries from competing retailersincluding Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Morrisons, andWaitrose.If Asda’s price of comparable groceries is not 10% lowerrelative to the competitors’ prices, consumers receivethe price difference in the form of a voucher that canbe used in the future shopping trips. It was reportedthat 800,000 consumers used this price check websitein the first two months of 2011 (Asda 2011). Note thatthis type of price check website is useful only after

purchase and can greatly facilitate consumers’ post-purchase search. However, it is not clear why Asdawould invest in such a website. Conventional wisdommight suggest that this type ofwebsitemay induce con-sumers to search more actively after purchase, therebyintensifying price competition. As a result, Asda couldsuffer significant losses by hosting such website. Ourpaper provides a rationale for why it may be profitablefor Asda to do so.

Motivated by these stylized facts, we seek to answerthe following questions facing retail managers: (1) In agiven product category, under what market conditionsshould retailers offer PMGs? For example, are we morelikely to observe PMGs in markets with high searchcosts (e.g., offline) or low search costs (e.g., online)?(2) Why is it that all retailers in some product cate-gories offer PMGs but few or none offer PMGs in othercategories? For example, are we more likely to observePMGs in categories with high or low product valuation(e.g., jewelry versus electronics versus office goods)?(3) Do retailers have the incentive to invest in technolo-gies to facilitate consumers’ postpurchase search? If so,under what market conditions is it profitable for retail-ers to do so?

1.1. Overview of Model Setup and Major ResultsTo address these issues, we consider a symmetric duo-poly in which retailers decide whether or not to offerPMG. Conditional on this decision, retailers simul-taneously set prices. Consumers who are heteroge-neous in their pre- and postpurchase search costs thensearch sequentially for price information. We apply the“Pandora’s rule” in Weitzman (1979) to construct con-sumers’ optimal search rule, which in turn determinesboth their equilibrium shopping decisions and retail-ers’ equilibrium pricing and price-matching strategies.

We examine amodel inwhich consumers exhibit oneof three search and purchase behaviors. We label thesethree consumer segments as shoppers, nonshoppers, andrefundees. Shoppers are consumers who have low pre-purchase search cost. They obtain price informationbefore purchase and directly purchase from the low-price retailer independent of the retailers’ decision tooffer PMG. Nonshoppers are consumers with high pre-and postpurchase search costs. In equilibrium, theseconsumers do not search and therefore purchase fromthe retailer with the lower expected price. Refundeeshave high prepurchase search costs but low postpur-chase search costs. As explained later, it is realistic toexpect that search costs may vary over time and thatconsumers may have lower postpurchase search costs.For example, consumers may have a high waiting costif an appliance breaks down unexpectedly. They mayhave to purchase without searching extensively. At alater time (within the grace period), they may havetime to search and could benefit from PMG. The shop-ping behavior of refundees depends on whether or

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017

, at 1

8:46

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Jiang, Kumar, and Ratchford: Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer SearchManagement Science, 2017, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 3489–3513, ©2016 INFORMS 3491

not retailers offer PMG. In the absence of PMG, refun-dees act like nonshoppers. In the presence of PMG,refundees skip prepurchase search, patronize the PMGretailer(s), conduct postpurchase search, and ask fora price match if they find a lower price. We find thatPMG has a demand-expansion effect: PMG attractsthe refundee segment at the expense of some shop-pers and nonshoppers, but the net effect of PMG onretail demand is positive. Furthermore, the demand-expansion effect increases with the size of refundees.With competition for these three consumer segments,

retailers’ pricing will be in mixed strategies; that is,each retailer charges a range of prices with varyingprobabilities. We show that PMG intensifies price com-petition on two dimensions. On the one hand, PMGprovides refundees with the opportunity to searchafter purchase and obtain a lower price if available.Consequently, both retailers are compelled to offerdeeper promotions (retailers charge high prices withsmaller probability and low prices with greater prob-ability) because PMG increases the overall extent ofconsumer search. We call this the primary competition-intensifying effect. Because consumer search is endoge-nous in our model, the primary competition-inten-sifying effect alters consumers’ search and purchasebehaviors such that deeper promotions provide con-sumers greater incentives to search elsewhere for alower price. To counter this growing incentive of con-sumer search, both retailers may be forced to lowertheir “regular” price (the commonupper bound of bothretailers’ price distributions is lowered). We label thisthe secondary competition-intensifying effect. While theprimary competition-intensifying effect increases withthe size of shoppers, the strength of the secondarycompetition-intensifying effect increases with the ratioof product valuation to search cost.Retailers’ equilibrium price-matching strategies de-

pend on the relative importance of the demand-expan-sion effect and the (primary and secondary) compe-tition-intensifying effects. When the size of shoppersis large, PMG is not offered in equilibrium since it isunprofitable to induce even more search by offeringPMG. Conversely, when the size of refundees is large,the demand-expansion effect is strong, and both retail-ers offering PMG is an equilibrium. Finally, when thesizes of shoppers and refundees are both small, theequilibrium outcome depends on the ratio of prod-uct valuation to search cost. When the ratio of prod-uct valuation to search cost is high, the secondarycompetition-intensifying effect is strong, and furtherintensifying competition by offering PMG is not prof-itable. When the ratio of product valuation to searchcost is low, both retailers offering PMG is an equilib-rium. When the ratio of product valuation to searchcost is intermediate, there exists an asymmetric equi-librium in which one retailer offers PMG while the

other does not. In the asymmetric equilibrium, thePMG retailer always charges an average price, which isweakly greater than that of the non-PMG retailer.

Finally, we relax our assumption of price matchingand expand the strategy space to allow the use of price-beating guarantees (PBGs). Through PBGs, retailerspromise to beat any competitor’s lower price by a cer-tain percentage, which we call the refund depth. Wefind that our results are still robust in the PBG case.We show that both average retail prices and retail prof-its are decreasing in the refund depth. The parameterspace under which PBG is profitable shrinks as therefund depth increases. In addition, PBGs are less prof-itable than PMGs. This finding is consistent with Hviidand Shaffer (1994) and Corts (1995) who also show thatPBGs are less preferable to PMGs.

How can we relate our findings to observed marketpractices? First, we are able to explain why some retail-ers who operate both online and offline implementPMG offline but not online. As noted above, the sec-ondary competition-intensifying effect strengthens asthe ratio of product valuation to search cost increases.Since the online search cost is lower than offline searchcost, for the same product the ratio of product val-uation to search costs is greater in online marketsthan offlinemarkets. Under these conditions ourmodelwould predict that the secondary competition-intensi-fying effect in the online environment is stronger thanin the offline environment, thus explaining why retail-ers that operate both online and offline only offer PMGsoffline but not online.Note that our explanation holds evenwhen the competitive structure in online and offline marketsis the same.Second, our findings offer an explanation for the

considerable variation in PMG practices across retailcategories as is shown in Table 1. This is because prod-uct valuations differ across retail categories. For exam-ple, the product valuation of office supplies is low sothe secondary competition-intensifying effect faced byretailers in this category is relatively weak, and there-fore PMG is profitable. In comparison, jewelry hasvery high product valuation. Our model predicts thatin such categories, the secondary competition-intensi-fying effect is strong, rendering it unprofitable to offerPMG. In the electronics category, however, product val-uation is moderately high; in such markets, it is onlyprofitable for some, but not all, retailers to offer PMGs.Thus, an asymmetric equilibrium emerges in suchmar-kets.Note that our explanation for these differences in PMGpractices holds, even if the mix of customers is the sameacross the product categories.To shed light on the seemingly counterintuitive appli-

cation of the price check website by Asda, we firstnote that such price check website essentially trans-forms some nonshoppers into refundees by increasing

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017

, at 1

8:46

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Jiang, Kumar, and Ratchford: Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer Search3492 Management Science, 2017, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 3489–3513, ©2016 INFORMS

the proportion of consumers who have low postpur-chase search cost. We find that the PMG retailer maybenefit from price check technology in the asymmetricequilibrium.On theonehand, this technology increasesthe overall extent of consumer search and thus magni-fies the (primary and secondary) competition-intensi-fying effect of PMG. On the other hand, the demand-expansion effect of PMG also becomes stronger as thesize of refundees increases. When the size of refundeesis relatively small, we show that the latter effect domi-nates the former and that the PMG retailer is better offwith the price check technology.

1.2. Literature ReviewOur paper builds on several streams of research. Thereis a long tradition inmarketing and economics of exam-ining the competitive implications of PMG. However,there is no consensus on whether PMG is anti- orprocompetitive. Early researchers argue that PMG canfacilitate tacit collusion among competing retailers andis therefore anticompetitive (see, e.g., Hay 1982, Salop1986, Logan and Lutter 1989, Baye and Kovenock 1994,Chen 1995, Zhang 1995). When retailers are committedto match lower prices charged by competitors in themarket, no one has the incentive to undercut the rivals.Hviid and Shaffer (1999) and Coughlan and Shaffer(2009) highlight the sensitivity of these findings to cer-tain assumptions made in earlier research. Hviid andShaffer (1999) find that an infinitesimally small has-sle cost could attenuate the ability of PMG to mitigateprice competition. Coughlan and Shaffer (2009) exam-ine situations in which retailers carry multiple prod-ucts and have limited shelf space. They show thatwhenboth asymmetric product substitutability and shelf-space availability are considered, retail price underPMG may even fall below the competitive level. Jainand Srivastava (2000) and Moorthy and Winter (2006)propose that PMG can serve as a credible signal of lowprices in a market where consumers have incompleteprice information and never conduct price search.3By identifying a segment of refundees that takes ad-

vantage of costless postpurchase search under PMG,our study is closely related to another strand of lit-erature that proposes PMG as a price discriminationtool. The idea is that, when consumers are heteroge-neous, PMG can be used to price discriminate one con-sumer type over the others. Janssen and Parakhonyak(2013) and Yankelevich and Vaughan (2016) both inves-tigate the price discrimination role of PMG withinthe endogenous search framework. In Janssen andParakhonyak (2013), some consumers with high searchcost do not search in equilibrium but are able to pas-sively receive a price quote after purchase. In addition,consumers do not know whether retailers offer PMGat the time of purchase; thus, PMG does not affect con-sumers’ search and purchase decisions. Consequently,

PMG increases consumers’ option value of purchaseand knowing this, all retailers charge a higher price.Yankelevich and Vaughan (2016) assume that someshoppers patronize PMG retailers only and will invokePMG if a lower price exists. As a result, PMG increasesretail prices. In contrast to their findings that PMGis anticompetitive, we show that PMG is procompeti-tive as it provides refundees the opportunity to searchafter purchase. The overall extent of consumer searchincreases; hence, the retail price is lowered. We alsofind that endogenous consumer search could lead to asecondary effect on retail competition that affects theretailers’ regular price, which has been ignored in thisstream of work.

Png and Hirshleifer (1987), Corts (1997), Chen et al.(2001), and Hviid and Shaffer (2012) assume that someconsumers are exogenously endowed with the abilityto take advantage of PMG while others cannot. Pngand Hirshleifer (1987) find that PMG induces retail-ers to charge higher prices and is always profitablefor retailers. Corts (1997) shows that PMG may leadto higher or lower prices but it is still profitable forretailers to offer PMG. Chen et al. (2001) show thatboth price and profit can go up or down when retail-ers institute PMG depending on market parameters.Hviid and Shaffer (2012) investigate the case wheresmall local stores set prices at the local level while largechain stores set prices at the national level independentof local market conditions. They delineate the marketconditions under which it is optimal for the local storesto offer PMG, price-beating guarantee (PBG), and noprice guarantee.

Empirical evidence on the competitive effects of PMGis somewhat limited. Hess and Gerstner (1991) andArbatskaya et al. (2004, 2006) provide empirical evi-dence that is consistent with the anticompetitive roleof PMG. The latter two studies examine price quotesobtained from U.S. newspaper advertisements in late1996. In their study of guarantees across a variety ofproducts, Arbatskaya et al. (2004) document that about37% of guarantees could be classified as price-beatingguarantees (PBGs) rather than PMGs, although PMGsare still the mainstream. PMGs are found to be morelikely than PBGs to apply to selling rather than adver-tised prices and to have less restrictive terms for ful-fillment. Based on these findings, the authors concludethat PMGs are more likely to facilitate collusion. Usingdata on tire advertisements from the same period,Arbatskaya et al. (2006) find that PMGs tend to be asso-ciated with higher prices than competitors that do notoffer them. They take this as evidence that is consistentwith the anticompetitive role of PMG, but they alsonote that fostering price discrimination is an alterna-tive explanation for this result.

While evidence in the above studies tends to favorthe collusion story, Moorthy and Winter (2006) and

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017

, at 1

8:46

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Jiang, Kumar, and Ratchford: Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer SearchManagement Science, 2017, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 3489–3513, ©2016 INFORMS 3493

Moorthy and Zhang (2006) find that PMG is usuallynot adopted by all retailers in a market and tends tobe adopted by retailers with low costs or low quality,which they take as inconsistent with PMG being anti-competitive. They argue that this and other evidenceis most consistent with PMG as a signal of low prices.In a case study of British supermarket prices, Manez(2006) finds evidence that the low-price retailer initi-ated PMG, which is consistent with using PMG to sig-nal low prices. In an experimental market study, Yuanand Krishna (2011) find that subjects who were desig-nated to be sellers tended to offer PMG when they hadthe option to do so, and they varied prices in a wayconsistent with using mixed strategies for price dis-crimination. Buyers also searched more when PMGswere available. These results were taken as evidencein favor of the use of PMG as a price discriminationdevice. Thus, different studies have found evidence forand against explanations of PMG as a device for col-lusion, signaling, and price discrimination. However,the above empirical evidence covers only a limitedselection of markets, and some of it may be obsoletebecause data were collected prior to the widespreaduse of Internet. Moreover, none of the studies dis-cussed in this paragraph have explicitly examined theuse of PMG as an option to take advantage of post-purchase search.There is a behavioral literature that examines con-

sumers’ postpurchase search behavior in the presenceof PMG. Kukar-Kinney et al. (2007) suggest that thereexists a group of “less price-conscious” consumerswhopurchase from a PMG retailer to avoid costly prepur-chase search because prepurchase search cost is highcompared with the gain from search. Dutta and Biswas(2005) investigate the moderating role of value con-sciousness in the relationship between PMG and con-sumers’ postpurchase search intentions. They find thatconsumers who have “high value consciousness” areprone to conduct postpurchase search, as the bene-fit from postpurchase search exceeds its cost. Theirfindings support our assumption of the existence ofrefundees, i.e., consumers who have high prepurchasesearch costs but low postpurchase search costs. Limand Ho (2008) provide an experimental analysis inwhich respondents are explicitly asked to reveal thelikelihood of postpurchase search. They find that con-sumers are generally more likely to search after pur-chase when faced with a PMG retailer. The centraltheme of these papers is to identify the type of con-sumers who will search after purchase in the pres-ence of PMG. In addition, Dutta et al. (2011) evaluatethe ability of PMG to reduce consumer regret when alower price is discovered after purchase. Kukar-Kinneyand Grewal (2006) study how retail factors, such asretail environment and store reputation, affect con-sumers’ postpurchase search intentions and willing-ness to invoke PMG. Finally, McWilliams and Gerstner

(2006) show theoretically that PMG can be used toimprove customer retention by reducing the dissatis-faction of customers who found a lower price afterpurchase.We build on this literature by explicitly mod-eling consumers’ postpurchase behavior and examin-ing the effect that postpurchase search behavior has onstores’ optimal pricing and price-matching strategies.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.Section 2 presents the model description including keyassumptions and the game structure. We present theanalysis in Section 3. In Section 4 we extend the base-line model to the case of price-beating guarantees andconclude in Section 5.

2. ModelConsider a market with two ex ante identical retailersindexed by i (i � A,B). They sell a homogeneous prod-uct to the end consumers. Consumers have a productvaluation of v, which is the maximum they are will-ing to pay for one unit of the product. Without anyloss of generality, we assume that retailers have iden-tical marginal costs, which are normalized to zero. Weassume that consumers search sequentially for priceinformation with perfect recall. To assure full partic-ipation, we assume that consumers obtain the firstprice quote for free. Sequential price search, perfectrecall, and the first price quote for free are commonassumptions in the consumer search literature (e.g.,Morgan and Manning 1985, Stahl 1989, Moorthy et al.1997, Kuksov 2004). The measure of consumers is nor-malized to one without loss of generality. Consumersdemand at most one unit of the product.

To allow for heterogeneity in search costs before andafter purchase, we assume that some consumers havea prepurchase search cost of 0 after the initial freesearch, while others have a positive prepurchase searchcost of c > 0. Consumers who have purchased from aPMG retailer may continue to search after purchasefor a better deal within the grace period. We assumethat the postpurchase search cost is 0 for some con-sumers and c for others. Discrete heterogeneity in pre-and postpurchase search costs yields four exhaustiveand mutually exclusive segments of consumers: con-sumers who have zero pre- and postpurchase searchcosts; consumers who have zero prepurchase searchcost but a postpurchase search cost of c; consumer whohave a prepurchase search cost of c but zero postpur-chase search cost; and consumers who have pre- andpostpurchase search costs of c.

A key assumption of this paper is the existence ofconsumers with high prepurchase search cost but lowpostpurchase search cost. It is not hard to envisioncases in which this holds true. First, prepurchase pricesearch is usually accompanied with product-relatedinformation search and thus can be more cognitivelychallenging for consumers than postpurchase pricesearch. If the retailer offers a PMG, consumersmay buy

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017

, at 1

8:46

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Jiang, Kumar, and Ratchford: Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer Search3494 Management Science, 2017, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 3489–3513, ©2016 INFORMS

Figure 1. Timeline of Decisions in the Game

Stage 1: Price-matching strategies PMA = 0, 1

S = ⟨0, 0⟩ S = ⟨1, 0⟩ S = ⟨0, 1⟩ S = ⟨1, 1⟩

Fi⟨0,0⟩(p) Fi

⟨1,0⟩(p) Fi⟨0,1⟩(p) Fi

⟨1,1⟩(p)

Stage 3: Consumer search andpurchase strategies

Prepurchase searchPurchasePostpurchase searchRefund

Prepurchase searchPurchasePostpurchase searchRefund

Prepurchase searchPurchasePostpurchase searchRefund

PMB = 0, 1

Retailer A Retailer B

Stage 2: Mixed pricing strategies

Prepurchase searchPurchasePostpurchase searchRefund

the item and wait until time costs are lower to checkother prices. Second, consumers under time pressureor making an unplanned purchase may value timebefore purchase more than after purchase. For exam-ple, if an appliance such as a TV, refrigerator, or airconditioner breaks down, the cost of doing without theitemwhile a complete search is conducted may be veryhigh. Knowing that the retailer has a PMG policy, theconsumer may buy the itemwithout searching and useit while waiting for a more opportune time to checkprices at other stores. A grace period to exercise thePMG allows the consumer to wait until search costs arelow. As noted in our literature review, several studiessupport the existence of this consumer segment.The game unfolds in three stages, as shown in Fig-

ure 1. In the first stage, retailers simultaneously choosetheir price-matching strategies, which then becomecommon knowledge to all agents in subsequent stagesof the game. Let PMi

� 1 or 0 be an indicator of whetherretailer i (i � A,B) offers PMG or not, respectively. Weuse S � 〈PMA ,PMB〉 to index the subgame in whichthe price-matching strategies of retailer A and B arePMA and PMB , respectively. There are four possiblesubgames: 〈0, 0〉, 〈1, 0〉, 〈0, 1〉, and 〈1, 1〉. The fixed costof implementing PMG is assumed to be zero with-out loss of generality. We further assume that PMG islegally binding and enforceable. In the second stage,both retailers simultaneously set prices conditional ontheir first-stage price-matching strategies. Given thediscrete consumer segments, particularly the existence

of consumers with zero prepurchase search costs, weanticipate the pricing equilibrium to be inmixed strate-gies. We denote retailer i’s price distribution in sub-game S as F i

S(p). In the third stage, consumers whohave perfect knowledge of their own search cost struc-ture make decisions on prepurchase search, purchase,postpurchase search, and refund redemption en masse.The equilibrium concept we employ is subgame per-fect Nash equilibrium. For reference, a summary ofthe model notations is presented in Table A.1 of theappendix.

3. AnalysisIn this section we proceed in the following manner.Since consumers’ search behavior will have a signifi-cant bearing on retailers’ pricing decisions, we estab-lish consumers’ optimal search rule in Section 3.1. InSection 3.2, we characterize retailers’ pricing strategieswhile taking consumers’ optimal search behavior intoaccount and taking retailers’ first-stage decisions asgiven. Finally, we characterize retailers’ price-matchingstrategies in Section 3.3.

3.1. Optimal Consumer Search RuleConsumers will engage in search as long as the ex-pected benefit from search is greater than their searchcost. Given a priori lowest price quote z at hand, con-sumer surplus from sampling an additional retailerthat charges a price of p is

CS(p; z)� max{z − p , 0}. (1)

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017

, at 1

8:46

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Jiang, Kumar, and Ratchford: Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer SearchManagement Science, 2017, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 3489–3513, ©2016 INFORMS 3495

Then the marginal benefit of sampling once from re-tailer i’s price distribution F i(p) mixing over the inter-val [l , u] is the expected consumer surplus of search

ECS(z; F i(p))�∫ u

lCS(p; z) dF i(p). (2)

For consumers with search cost c, there exists a uniquez such that the marginal benefit of search is equal tosearch cost. We define this unique price threshold asretailer i’s reservation price r i :

r i� arg

z

{ECS(z; F i(p)) − c � 0

}. (3)

The economic meaning of r i is the price at which con-sumers with search cost c are indifferent to samplingretailer i or not. It is easy to see that r i is an increasingfunction of c.

Following Weitzman (1979), we can summarize theoptimal search strategy for consumers with searchcost c as follows. When they base their search strategyon retailers’ pricing strategies only, consumers withsearch cost c will sample the retailer with the lowerreservation price first, followed by the retailer with thehigher reservation price. They stop at the first retailerthat charges a price below mini�A,B r i or else pick theretailer with the lower price after both retailers aresampled. In Lemma 6, we show that the retailer withthe lower reservation price also has a lower averageprice. This means that consumers with search cost cfirst sample the retailer with the lower average pricein the hope of getting a good deal and completing thecostly search process as early as possible. Otherwise, ifthe price is not low enough, they will continue pricesearch with the second retailer. If both retailers havethe same reservation price, consumers are indifferentand will search randomly.For consumers with zero (pre- or postpurchase)

search cost, the marginal benefit of search is weaklygreater than their search cost. Thus, the optimal searchrule for consumers with zero search cost is to obtainprice information from both retailers before stopping.4Given the optimal search rule, we can proceed to char-acterize the equilibrium pricing strategies.

3.2. Equilibrium Price DistributionsWe first characterize the equilibrium upper bound ofretailers’ mixed pricing strategies in each subgame inLemma 1.

Lemma 1. Let r iS be the reservation price of retailer i in sub-

game S. Both retailers’ price distributions share a commonupper bound uS � min{v ,mini�A,B r i

S}.

Proof. See the appendix.

Table 2. Notation of Consumer Segments

Postpurchase search cost

Consumer segment 0 c

Prepurchase 0 Shoppers (α)search cost c Refundees (β) Nonshoppers (γ)

Lemma 1 states that the upper bound of both retail-ers’ price distributions is the minimum of the prod-uct valuation and the minimum reservation prices ofboth retailers. Prices above the product valuation v aredominated since there will be zero demand. Any priceabovemini�A,B r i will encourage consumers to continueto search elsewhere and is therefore weakly dominatedby mini�A,B r i . A key implication of Lemma 1 is that,in equilibrium, consumers with pre- or postpurchase searchcost c do not conduct actual search except for the first freequote based on the optimal search rule. For ease of expo-sition, we call a fraction of α consumers with zeroprepurchase search cost “shoppers,” a fraction of βconsumers with positive prepurchase search cost butzero postpurchase search cost “refundees,” and a frac-tion of γ consumers with both pre- and postpurchasesearch cost of c “nonshoppers.” In our model, α + β +γ � 1; see Table 2. We characterize the equilibriumsearch and purchase behavior of each consumer seg-ment in Proposition 1.

Proposition 1. Given assumptions on consumers’ pre- andpostpurchase search costs, the optimal consumer search andpurchase behavior for each consumer segment in equilibriumis as follows:

(i) Nonshoppers do not search, purchase from the retailerwith the (weakly) lower reservation price, and pay the pricecharged by the retailer.

(ii) In the absence of PMG, refundees act like nonshop-pers. In the presence of PMG, refundees purchase from aPMG retailer. After purchase, they take advantage of costlesspostpurchase search and ask for a refund if a lower price isfound.

(iii) Shoppers search both retailers before purchase andpurchase directly from the retailer that charges the lowerprice.

Proof. See the appendix.

Since they have no price information, nonshoppersdirectly purchase from the retailer with the lower reser-vation price. If both retailers have the same reservationprice, nonshoppers pick retailers randomly. The shop-ping behavior of refundees depends upon the presenceor absence of PMG retailers. In the absence of PMG,refundees, like nonshoppers, cannot obtain any benefitfrom postpurchase search and will purchase from theretailer with the lower reservation price. In the pres-ence of PMG, refundees will purchase from the PMGretailer(s) to take advantage of costless postpurchase

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017

, at 1

8:46

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Jiang, Kumar, and Ratchford: Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer Search3496 Management Science, 2017, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 3489–3513, ©2016 INFORMS

search and ask for a refund if a lower price is discov-ered after purchase. This highlights an important dis-tinction between nonshoppers and refundees. That is,nonshoppers’ search strategy hinges on retailers’ pric-ing strategies only while refundees’ shopping behav-ior is dependent on both pricing and price-matchingstrategies of retailers.Because it can entice refundees to purchase, PMG

has a direct demand effect on retailers that offer it.PMG retailers are positioned to cater to the needsof refundees who prefer to avoid costly prepurchasesearch and postpone search until after purchase. Inthe Asda example in the introduction, the 800,000 con-sumers who visited Asda’s price check website in thefirst two months of 2011 to compare prices after pur-chase fit the definition of refundees in our model.

Shoppers collect price information from both retail-ers before purchase and are guaranteed to pay the low-est market price. One might wonder why shoppers donot invoke PMG at the time of purchase instead, inwhich case they also pay the lowest market price. Thereason is as follows: Suppose that a shopper commitsto purchase from a PMG retailer and decides to invokePMG if the competing retailer charges a lower price.The shopper would now act like a “loyal” consumer,thus enabling the PMG retailer to charge a higherprice. Due to the strategic complementarity of prices,the competing retailer will do the same. Although thisshopper still pays the lowest market price, the low-est market price itself will be higher relative to thecase when the shopper commits to directly purchasefrom the retailer with the lower price. Thus, shoppersare strictly worse off if they commit to purchase from thePMG retailer and invoke PMG.Because of the need to serve all three consumer seg-

ments, retailers’ pricingwill be inmixed strategies; thatis, each retailer charges a range of prices with vary-ing probabilities. Because of symmetry, it is sufficientfor us to consider the following three subgames in thepricing stage: 〈0, 0〉, 〈1, 1〉, and 〈1, 0〉.3.2.1. Neither Retailer Offers PMG. Consider the sub-game 〈0, 0〉 in which neither retailer offers PMG. Inthis subgame, like nonshoppers, refundees who can-not take advantage of costless postpurchase search ran-domly pick one retailer. Therefore, each retailer attractshalf of the refundees and nonshoppers who pay theobserved price. Shoppers visit the retailer with a lowerprice. When it charges a price of pA, retailer A canattract all shoppers if retailer B charges a price greaterthan pA, which occurs with probability 1 − FB

〈0, 0〉(pA).Thus, the expected profit of retailer A when it chargesa price of pA is given by

EΠA〈0, 0〉(pA)�

{α[1− FB

〈0, 0〉(pA)]+β+ γ

2

}pA . (4)

The equilibrium price distribution is reported inLemma 2.

Lemma 2. When neither retailer offers PMG, the equilib-rium price distribution for retailer i is given by

F i〈0, 0〉(p) � 1−

β+ γ

2α

(u〈0, 0〉

p− 1

),

for p ∈ [l〈0, 0〉 , u〈0, 0〉], (5)

where u〈0, 0〉 � min{r i〈0, 0〉 , v} and l〈0, 0〉 � ((β + γ)/2/(α +

(β+γ)/2))u〈0, 0〉 is the lower bound of the price distribution.Here, r i

〈0, 0〉 is the reservation price of retailer i and is definedin the appendix. The profit of retailer i is given by

Πi〈0, 0〉 �

β+ γ

2 u〈0, 0〉 . (6)

Proof. See the appendix.3.2.2. Both Retailers Offer PMGs. Next we focus onthe subgame 〈1, 1〉 in which both retailers implementPMGs. The effective price refundees pay is the mini-mum price of both retailers. Moreover, they are indif-ferent with purchasing from either retailer. Therefore,retailer A can attract all shoppers with probability 1−FB〈1, 1〉(pA)when it charges a price pA, together with half

of refundees and nonshoppers. The expected profit ofretailer A when it charges a price pA is given by

EΠA〈1, 1〉(pA) �

{α[1− FB

〈1, 1〉(pA)]+γ

2

}pA

+β

2E[

minpB∈ΣB

〈1, 1〉

{pA , pB}], (7)

in which pB is the price charged by retailer B chosenfrom the strategy set ΣB

〈1, 1〉 . E[minpB∈ΣB〈1, 1〉{pA , pB}] is the

expected effective price refundees pay and can be fur-ther expanded as [1− FB

〈1, 1〉(pA)]pA + ∫ pA

l〈1, 1〉pB dFB

〈1, 1〉(pB).If pB ≥ pA, which occurs with probability 1− FB

〈1, 1〉(pA),refundees pay pA. Otherwise, if pB < pA the effectiveprice for refundees will be pB . In this case, the effec-tiveprice refundeespayonaverage is ∫ pA

l〈1, 1〉pB dFB

〈1, 1〉(pB).The equilibrium pricing strategies are summarized inLemma 3.Lemma 3. When both retailers offer PMG, the equilibriumprice distribution for retailer i is given by

F i〈1, 1〉(p) � 1−

γ/2α+ β/2

[(u〈1, 1〉

p

) (α+β/2)/α− 1

],

for p ∈ [l〈1, 1〉 , u〈1, 1〉], (8)

where u〈1, 1〉 � min{r i〈1, 1〉 , v} and l〈1, 1〉 � (γ/2/(α +

(β+ γ)/2))α/(α+β/2)u〈1, 1〉 is the lower bound of the price dis-tribution. Here, r i

〈1, 1〉 is the reservation price of retailer i andis defined in the appendix. The profit of retailer i is given by

Πi〈1, 1〉 �

(α+

β+ γ

2

)·(

γ/2α+ (β+ γ)/2

)α/(α+β/2)u〈1, 1〉 . (9)

Proof. See the appendix.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017

, at 1

8:46

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Jiang, Kumar, and Ratchford: Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer SearchManagement Science, 2017, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 3489–3513, ©2016 INFORMS 3497

3.2.3. When Only Retailer A Offers PMG. Finally, weturn to the asymmetric subgame 〈1, 0〉 in which re-tailer A offers PMGwhile retailer B does not. Retailer Asells to all shoppers with probability 1− FB

〈1, 0〉(pA), andall refundees with certainty, while retailer B sells toall shoppers with probability 1− FA

〈1, 0〉(pB), and attractsno refundees. Since nonshoppers purchase from theretailer with lowest reservation price, their purchasedecisions are endogenous to retailers’ pricing strate-gies. We denote µ (1 ≥ µ ≥ 0) as the shopping strat-egy of nonshoppers; that is, µ represents the proba-bility that nonshoppers will patronize retailer A. Inthe aggregate, µ can be reinterpreted as the propor-tion of nonshoppers purchasing from retailer A and1−µ is the fraction of nonshoppers who purchase fromretailer B. Thus, the expected profit of retailer A whenit charges a price of pA is given by

EΠA〈1, 0〉(pA) �

{α[1− FB

〈1, 0〉(pA)]+ µγ}

pA

+ βE[

minpB∈ΣB

〈1, 0〉

{pA , pB}], (10)

in which pB is the price charged by retailer B cho-sen from its strategy set ΣB

〈1, 0〉 . The expected profit ofretailer B when it charges a price pB is given by

EΠB〈1, 0〉(pB)�

{α[1− FA

〈1, 0〉(pB)]+ (1− µ)γ}

pB . (11)

We report the equilibrium pricing strategies in theasymmetric subgame in Lemma 4.

Lemma 4. When only retailer A offers PMG, there exists aunique µ∗ such that 0.5 > µ∗ > 0 when the size of refundeesis small (β < β̄) and µ∗ � 0 when the size of refundees is large(β ≥ β̄). Given µ∗, the equilibrium pricing strategies for bothretailers are given by

FA〈1, 0〉(p)�1−

(1−µ∗)γα

(u〈1, 0〉

p−1

),

for p ∈ [l〈1, 0〉 ,u〈1, 0〉];

FB〈1, 0〉(p)�

1 at p � u〈1, 0〉 ,

α+ β+µ∗γ

α+ β

[1−

(l〈1, 0〉

p

) (α+β)/α],

for p ∈ [l〈1, 0〉 ,u〈1, 0〉),

(12)

where u〈1, 0〉 � min{rB〈1, 0〉 , v} and l〈1, 0〉 � ((1− µ∗)γ/(α +

(1− µ∗)γ))u〈1, 0〉 is the lower bound of both retailers’ pricedistributions. Here, r i

〈1, 0〉 is the reservation price of retailer iand is defined in the appendix. The profits of retailer A andB are given by

ΠA〈1, 0〉 �

(α+ β+ µ∗γ)(1− µ∗)γα+ (1− µ∗)γ u〈1, 0〉 and

ΠB〈1, 0〉 � (1− µ∗)γu〈1, 0〉 .

(13)

Proof. See the appendix.

The first sentence of Lemma 4 characterizes non-shoppers’ equilibrium shopping behavior. Note thatnonshoppers do not search and thus will strategicallychoose the retailer with the lower reservation price(and average price). Recognizing that retailer A has agreater incentive to charge a high price after obtain-ing all refundees by offering PMG, nonshoppers aretherefore less prone to purchase from retailer A than B.This means that retailer A gets less than one half ofthe nonshoppers, 0.5 > µ∗ ≥ 0. We find that, when thesize of refundees is relatively small (β ≤ β̄), nonshop-pers adopt a mixed shopping strategy (0.5 > µ∗ > 0)such that the marginal nonshopper is indifferent toboth retailers since their reservation prices (and aver-age prices) are equal in equilibrium, rA

〈1, 0〉 � rB〈1, 0〉 . When

the size of refundees is relatively large (β > β̄), non-shoppers follow a pure strategy; that is, they will pur-chase from retailer B with probability one (µ∗ � 0).Although all nonshoppers buy from retailer B in thiscase, retailer B’s reservation price (and the averageprice) is still lower than that of retailer A, that isrA〈1, 0〉 > rB

〈1, 0〉 . This result is consistent with the findingof Arbatskaya et al. (2006) that PMG retailers tend tocharge prices weakly higher than non-PMG retailers.

The second part of Lemma 4 characterizes the equi-librium pricing strategies of both retailers. The equi-librium price distributions in Equation (12) implythat retailer B will have a mass point at the upperbound u〈1, 0〉 . In line with Narasimhan (1988), the upperbound is customarily interpreted as the “regular” or“nonpromoted” price, and any price below the regularprice is considered a “promotion.” This result meansthat retailer A always runs a promotionwhile retailer Bcharges the regular price with positive probability (hasa point mass at the regular price). The intuition for thisfinding is that, although retailer B loses all refundees toretailer A, it attracts more nonshoppers than retailer A(µ∗ < 0.5). Hence, retailer B has a greater incentive tocharge the regular price to appropriate surplus fromnonshoppers than retailer A. At the same time, afterlosing all refundees to retailer A, shoppers becomestrategically more important for retailer B. When wecompare the price distributions of both retailers, wefind that retailer B offers deep discounts more fre-quently to become more appealing to shoppers.

Next we summarize the difference in the clientelemix of retailers in the asymmetric case when onlyretailer A offers PMG. The customer base of retailer Acomprises all shoppers with lower probability, allrefundees, and a smaller proportion of nonshoppers.In contrast, retailer B serves all shoppers with higherprobability and a larger fraction of nonshoppers. How-ever, it is not a priori obvious which retailer has alarger expected demand. The following propositioncompares the retail demand of both retailers in theasymmetric subgame.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017

, at 1

8:46

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Jiang, Kumar, and Ratchford: Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer Search3498 Management Science, 2017, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 3489–3513, ©2016 INFORMS

Proposition 2. When only retailer A offers PMG, retailer Ahas a larger expected demand than retailer B.

Proof. See the appendix.

Even though retailer A is less attractive to shoppersand nonshoppers, it sets prices such that the store loy-alty of refundees offsets the reduced demand from theother two consumer segments. This is consistent withthe experimental finding that PMG encourages morein-store visits and increases purchase intentions (Sri-vastava and Lurie 2001). A corollary of Proposition 2is that ΠA

〈1, 0〉 > ΠB〈1, 0〉 since retailer A has both a larger

expected demand and an average price weakly greaterthan retailer B.More generally, Proposition 2 implies that PMG has

a demand-expansion effect. To see this, note that in sub-games 〈0, 0〉 and 〈1, 1〉, both retailers split all three con-sumer segments evenly and hence have an expecteddemand of one half. In subgame 〈1, 0〉 retailer A’sexpected demand is greater than one half whileretailer B’s expected demand is less than one half.Thus, retailer A’s demand increases when it unilat-erally offers PMG. Similarly, retailer B’s demand alsoincreases by offering PMG when retailer A is already aPMG retailer. Moreover, the demand-expansion effectof PMG increases with the size of refundees β.

3.3. Stage 1: Price-Matching StrategiesIn Section 3.3, we address the issue of whether andunder what conditions retailers can benefit from offer-ing PMG in a competitive environment. That is, giventhe structure of three subgames developed in the pre-ceding subsections, we derive market conditions underwhich neither, one, or both retailers offering PMG is anequilibrium.Because consumer search is endogenous in our

model, the reservation price plays a central role in de-termining the equilibrium outcome. Moreover, com-paring reservation prices across subgames providesimportant insights into the impact of PMG on pricecompetition. In Table 3 we report reservation pricesacross three subgames obtained from Lemmas 2–4. Itcan be easily seen from Table 3 that reservation prices

Table 3. Equilibrium Reservation Prices Across Subgames

Subgame Reservation prices

〈0, 0〉 r i〈0, 0〉 �

2αc2α+ (β+ γ) ln((β+ γ)/(2α+ β+ γ))

〈1, 0〉 rA〈1, 0〉 �

αcα+ (1− µ∗)γ ln((1− µ∗)γ/(α+ (1− µ∗)γ)) ,

rB〈1, 0〉 �

β(α+ β)[α+ γ(1− µ∗)]cα(α+ β+ µ∗γ){β− γ(1− µ∗)[1− (γ(1− µ∗)/(α+ γ(1− µ∗)))β/α]}

〈1, 1〉 r i〈1, 1〉 �

βc(β+ γ) − (2α+ β+ γ)β/(2α+β)γ(2α)/(2α+β)

can be represented as a product of search cost c and afunction of consumer segment sizes (α and β given theconstraint that γ � 1− α − β). First we establish resultsabout the ordering of reservation prices in three sub-games in Lemma 5.

Lemma 5. When the size of refundees is not too large (β < ¯̄βwhere ¯̄β > β̄ as defined in the appendix), the following rela-tionship holds: r i

〈1, 1〉 < rB〈1, 0〉 ≤ rA

〈1, 0〉 < r i〈0, 0〉 .

Proof. See the appendix.

We assume that β < ¯̄β in the remainder of the paper.This assumption simplifies our exposition of the resultswithout changing the qualitative results. In the proof ofLemma 5 in the appendix, we discuss the market equi-librium when β ≥ ¯̄β. The implications of Lemma 5 willbe discussed after we lay out the following ancillaryresult that links the reservation price r i

S to the averageprice p̄ i

S and the regular price uS.

Lemma 6. Let p̄ iS be the average price of retailer i (i � A,B)

in subgame S. Then the following relationship holds:

p̄ iS � uS

(1− c

r iS

)or 1−

p̄ iS

uS�

cr i

S

. (14)

Proof. See the appendix.

Lemmas 5 and 6 allow us to make three remarksabout retail prices. First, note that both retailersshare the same regular price uS in any subgame.Lemma 6 says that within a subgame the retailer witha lower reservation price also charges a lower aver-age price. Since rA

〈1, 0〉 ≥ rB〈1, 0〉 in the asymmetric sub-

game 〈1, 0〉, Equation (14) implies that p̄A〈1, 0〉 ≥ p̄B

〈1, 0〉 ,i.e., retailer A charges an average price weakly higherthan that charged by retailer B in subgame 〈1, 0〉. Sec-ond, given r i

〈1, 1〉 < r i〈0, 0〉 from Lemma 5, the average

price in subgame 〈1, 1〉 is lower than that in subgame〈0, 0〉, p̄ i

〈1, 1〉 < p̄ i〈0, 0〉 . A corollary of this result is that

Πi〈1, 1〉 <Π

i〈0, 0〉 because retailers have the same expected

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017

, at 1

8:46

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Jiang, Kumar, and Ratchford: Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer SearchManagement Science, 2017, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 3489–3513, ©2016 INFORMS 3499

demand of one half in subgames 〈0, 0〉 and 〈1, 1〉. Thus,if 〈1, 1〉 is the unique equilibrium, it is a prisoner’sdilemma. Third, we can interpret 1− p̄ i

S/uS in Lemma 6as retailer i’s average promotion depth (in percentageterms) in subgame S. Lemma 6 implies that there isa negative relationship between a retailer’s reserva-tion price and the average promotion depth it offers.Since r i

〈1, 1〉 < r i〈1, 0〉 < r i

〈0, 0〉 , we can conclude that retailersoffer deeper promotions on average when more retail-ers offer PMG in the market.Next we examine the effect of PMG on retail compe-

tition. Consider the unilateral deviation by retailer Afromsubgame 〈0,0〉 to 〈1,0〉.Note thatLemma5 impliesrA〈1,0〉 < r i

〈0,0〉 . Retailer A’s PMG provides refundees withthe opportunity to continue search after purchase. Theoverall extent of consumer search increases. As dis-cussed above, retailers facing better informed consu-mers offer deeper promotions in subgame 〈1,0〉 thanin 〈0,0〉. Put differently, the average promotion depthincreases as retailer A offers PMG, 1− p̄ i

〈1,0〉/u〈1,0〉 > 1−p̄ i〈0,0〉/u〈0,0〉 . We call this the primary competition-intensi-

fying effect. Recall that u〈0,0〉 �min{v , r i〈0,0〉} and u〈1,0〉 �

min{v , rB〈1,0〉}. Then rB

〈1,0〉< r i〈0,0〉 implies that u〈1,0〉≤u〈0,0〉 .

Since a deeper promotion provides consumers withsearch cost c greater incentives to search, both retail-ers may be compelled to shift the “regular” price (i.e.,theupperboundof their pricedistributions)downward(u〈1,0〉 ≤ u〈0,0〉) to keep these consumers from searchingelsewhere.We call this the secondary competition-intensi-fying effect. This effect is a direct outcomeof endogenousconsumer search, where the regular price is endoge-nously determined. Inmodelswhere search behavior isexogenously assumed, this effect does not arise becausethe regular price is the product valuation v across allsubgames. Similarly, when the size of refundees is nottoo large (β < ¯̄β), we have r i

〈1,1〉 < r i〈1,0〉 . The incentive of

both retailers to charge a higher price is diminished asretailer B deviates from subgame 〈1,0〉 to 〈1,1〉. Thismeans that retailerB’s PMGalsohas aprimary andpos-sibly a secondary competition-intensifying effect whenretailer A already offers PMG. The above discussion ofhow PMG affects retail competition is summarized inProposition 3.

Proposition 3. PMG intensifies price competition on twodimensions. PMG has a primary competition-intensifyingeffect because it induces retailers to offer deeper promotions.There is potentially a secondary competition-intensifyingeffect of PMG because retailers may be forced to lower theregular price itself.

Proof. See the appendix.

So far we have identified three effects of PMG: de-mand-expansion effect, primary competition-intensi-fying effect, and secondary competition-intensifying

Table 4. Equilibrium Demand at the Regular Price AcrossSubgames

Subgame Demand at the regular price

〈0, 0〉 d i〈0, 0〉 �

β+ γ

2

〈1, 0〉 dA〈1, 0〉 �

(α+ β+ µ∗γ)(1− µ∗)γα+ (1− µ∗)γ , dB

〈1, 0〉 � (1− µ∗)γ

〈1, 1〉 d i〈1, 1〉 �

(α+

β+ γ

2

) (γ/2

α+ (β+ γ)/2

)α/(α+β/2)

effect. Among them, the secondary competition-inten-sifying effect is new to the literature. To better under-stand how it affects retail profits, we write Πi

S, theprofit of retailer i in subgame S, as Πi

S � uSd iS. Recall

that uS is the regular price in subgame S and is givenby uS � min{v ,mini�A,B r i

S}. d iS can be interpreted as

the expected demand of retailer i when it charges theregular price uS. In Table 4 we summarize d i

S acrosssubgames as shown in the profit Equations (6), (9),and (13). It is easy to see from Table 4 that d i

S is a func-tion of consumer segment sizes only.

Let∆Πi �ΠiS′−Πi

S be retailer i’s incremental profit byoffering PMG, where S and S′ are subgames before andafter its PMG, respectively. Retailer i finds it profitableto offer PMG only if ∆Πi > 0. Substituting Πi

S � uSd iS

into ∆Πi , we obtain Equation (15) by first subtractingand then adding uSd i

S′ :

∆Πi� (uS′ − uS)d i

S′︸¨̈ ¨̈ ¨̈ ¨̈ ¨︷︷¨̈ ¨̈ ¨̈ ¨̈ ¨︸Secondary competition-

intensifying effect

+

Demand-expansioneffect net of primary

competition-intensifying︷¨̈ ¨̈ ¨̈ ¨̈︸︸¨̈ ¨̈ ¨̈ ¨̈︷(d i

S′ − d iS)uS . (15)

Since the regular price after offering PMG is nohigher than that before offering PMG, uS′ ≤ uS, thefirst term in Equation (15), (uS′ − uS)d i

S′ , is nonpositive(it can be zero if uS � uS′ � v). This term representsthe secondary competition-intensifying effect of PMGon retail profits. In the extant literature that does notendogenize consumer search, the regular price is usu-ally held constant at the product valuation v. As aresult, (uS′ − uS)d i

S′ is equal to zero and the secondarycompetition-intensifying effect does not exist. This fail-ure to account for the secondary competition-intensi-fying effect could lead to the overestimation of the prof-itability of PMG. Given that uS � min{v ,mini�A,B r i

S}and uS′ � min{v ,mini�A,B r i

S′}, we find that uS′ − uSdecreases (becomes more negative) as the ratio ofproduct valuation to search cost v/c increases. Thisimplies that the secondary competition-intensifyingeffect weakly increases with v/c.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017

, at 1

8:46

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Jiang, Kumar, and Ratchford: Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer Search3500 Management Science, 2017, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 3489–3513, ©2016 INFORMS

The second term in Equation (15), (d iS′ − d i

S)uS, re-presents the demand-expansion effect net of theprimary competition-intensifying effect. The relativestrength of demand-expansion effect and the primarycompetition-intensifying effect depends on d i

S′ − d iS.

When d iS′ > d i

S, the demand-expansion effect is greaterthan the primary competition-intensifying effect. Oth-erwise, when d i

S′ < d iS, the demand-expansion effect

is weaker than the primary competition-intensifyingeffect. Following the discussion above, we now inves-tigate the retailers’ incentive for deviations to institutePMG and the conditions under which different equi-libria arise.

Proposition 4. Adoption of PMG is beneficial if and onlyif (1) d i

S′ > d iS and (2) v/c < h i(α, β), where h i(α, β) �

rBS′d

iS′/(cd i

S) is a function of consumer segment sizes only.5

Proof. See the appendix.

Proposition 4 delineates the necessary and sufficientconditions for PMG to be profitable. The first necessarycondition d i

S′ > d iS indicates that the demand-expansion

effect outweighs the primary competition-intensifyingeffect. Otherwise, retailers cannot benefit from adopt-ing PMG regardless of the secondary competition-intensifying effect. The second necessary conditionsays that the ratio of product valuation to search costmust be sufficiently low (i.e., v/c < h i). Here, h i isthe critical value of v/c at which ∆Πi � 0. In addi-tion, we have ∆Πi > 0 when v/c < h i and ∆Πi < 0when v/c > h i . Recall that the secondary competition-intensifying effect increases with the ratio of productvaluation to search cost v/c. Hence, we can take h i

as a measure of the demand-expansion effect net ofthe primary competition-intensifying effect. The sec-ond necessary condition v/c < h i means that thesecondary competition-intensifying effect is weakerthan the demand-expansion effect net of the primarycompetition-intensifying effect. These two conditionstogether are sufficient to guarantee a profitable devia-tion by retailers to offer PMG.

Proposition 5. The equilibrium price-matching strategiesare given by(i) When dA

〈1, 0〉 > d i〈0, 0〉 and d i

〈1, 1〉 > dB〈1, 0〉 , 〈1, 1〉 is the

equilibrium if v/c < mini h i; 〈1, 0〉 is the equilibrium ifhA > v/c > hB; both 〈1, 1〉 and 〈0, 0〉 are equilibria if hB >v/c > hA; 〈0, 0〉 is the equilibrium if v/c >maxi h i .(ii) When dA

〈1, 0〉 < d i〈0, 0〉 and d i

〈1, 1〉 > dB〈1, 0〉 , both 〈0, 0〉 and

〈1, 1〉 are equilibria if v/c < hB; 〈0, 0〉 is the equilibrium ifv/c > hB .(iii) When dA

〈1, 0〉 < d i〈0, 0〉 and d i

〈1, 1〉 < dB〈1, 0〉 , 〈0, 0〉 is the

equilibrium.

Proof. See the appendix.

This proposition summarizes the retailers’ equilib-rium price-matching strategies while highlighting the

Figure 2. Three Regions of Consumer Segment Sizes

The size of shoppers (�)

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0

The

siz

e of

ref

unde

es (�

)

hA < hB

hA > hB

III

II

I

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

role that the ratio of product valuation to search cost v/cplays in driving the results. As v/c grows larger,we see fewer retailers adopting PMG in equilibrium.This could explain why many retailers that operateboth online and offline implement PMG offline butnot online. Since Internet lowers consumer search cost(Ratchford 2009), online retailers have higher v/c thanoffline retailers. As a result, the secondary competition-intensifying effect in the online setting is stronger thanthat in the offline setting. Therefore, holding all elseequal, a retailer is less likely to offer PMG online thanoffline. In Proposition 5 we also identify three regionsthat differ in how v/c affects the equilibrium outcome:(I) dA

〈1, 0〉 > d i〈0, 0〉 and d i

〈1, 1〉 > dB〈1, 0〉 ; (II) dA

〈1, 0〉 < d i〈0, 0〉 and

d i〈1, 1〉 > dB

〈1, 0〉 ; and (III) dA〈1, 0〉 < d i

〈0, 0〉 and d i〈1, 1〉 < dB

〈1, 0〉 .6

These three regions are illustrated in Figure 2, whichis plotted on a two-dimensional plane with α and βas axes.

Consider region (I) in which the size of shoppers issmall (dA

〈1, 0〉 > d i〈0, 0〉 and d i

〈1, 1〉 > dB〈1, 0〉). When there are

few shoppers in the market, the primary competition-intensifying effect of PMG is weak and is dominatedby the demand-expansion effect. Thus, retailers’ equi-libriumprice-matching strategies in this region dependon the strength of the secondary competition-intensi-fying effect, which is determined by the ratio of prod-uct valuation to search cost v/c. In particular, whenv/c is small enough (v/c <mini h i), the secondarycompetition-intensifying effect is soweak that it is dom-inated by the demand-expansion effect net of the pri-mary competition-intensifying effect. In this case, bothretailers in equilibrium pursue the PMG strategy. Con-versely, when the secondary competition-intensifyingeffect is sufficiently strong (i.e., v/c is large enoughor equivalently, v/c >maxi h i), it is dominant for bothretailers to give up the PMG strategy. For intermedi-ate v/c, there are two possibilities depending on the

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017

, at 1

8:46

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Jiang, Kumar, and Ratchford: Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer SearchManagement Science, 2017, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 3489–3513, ©2016 INFORMS 3501

relative magnitude of hA and hB . In Figure 2, the dot-ted line in region (I) denotes the line in the α− β spacewhere hA � hB .We have hA > hB (hA < hB) below (above)the dotted line.Interestingly, when hA > v/c > hB (with an implied

condition of hA > hB), there exists an asymmetricequilibrium in which two ex ante symmetric retailersendogenously differentiate in their choices of PMG;that is, one retailer adopts PMG while the other doesnot. The asymmetric equilibrium reflects a trade-offbetween the secondary competition-intensifying effectand the demand-expansion effect net of the primarycompetition-intensifying effect. Because the secondarycompetition-intensifying effect for the first PMG in themarket is still weak, a retailer benefits from adoptingPMG only if the competitor does not. However, if aretailer offers PMG when its competitor is already aPMG retailer, the secondary competition-intensifyingeffect it faces will be inevitably too strong. As a result,symmetric retailers adopt asymmetric price-matchingstrategies in equilibrium. This is illustrated in the mid-dle section of Figure 3(a). Finally, when hB > v/c > hA,the secondary competition-intensifying effect is suchthat no retailers can benefit from unilaterally deviatingto offer PMG but will do so if the competitor alreadypursued the PMG strategy. Thus, as shown in the mid-dle section of Figure 3(b), both 〈1, 1〉 and 〈0, 0〉 are pos-sible equilibria in this situation.To sum up, region (I) highlights the value of endo-

genizing consumer search and considering the sec-ondary competition-intensifying effect. If consumersearch were not modeled endogenously, the upperbound in all subgames would be product valuation v,

Figure 3. The Equilibrium Price-Matching Strategies in Region (I)

Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩

Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩ Π⟨ ⟩

⟨ ⟩ ⟨ ⟩ ⟨ ⟩

⟨ ⟩ ⟨ ⟩ ⟨ ⟩ ⟨ ⟩

and the secondary competition-intensifying effect isessentially assumed away. The profitability of offeringPMG is overestimated, and the equilibrium predictionwould be 〈1, 1〉 regardless of the ratio of product valua-tion to search cost. We demonstrate that, as the ratio ofproduct valuation to search cost increases, the equilib-rium price-matching strategies shift from 〈1, 1〉 to 〈1, 0〉and to 〈0, 0〉 in markets where the size of the shop-pers and refundees are both small (i.e., dA

〈1, 0〉 > d i〈0, 0〉 ,

d i〈1, 1〉 > dB

〈1, 0〉 and hA > hB). This offers an explanation ofthe variation in PMG practices across retail categoriesin Table 1; that is, we see all, some, and no retailersoffering PMG in some categories. The higher the prod-uct valuation in a retail category, the greater the sec-ondary competition-intensifying effect retailers in thecategory face, and the less likely they are to offer PMG.

Part (ii) of Proposition 5 deals with region (II) inwhich dA

〈1, 0〉 < d i〈0, 0〉 and d i

〈1, 1〉 > dB〈1, 0〉 . This occurs when

the size of shoppers is intermediate orwhen the sizes ofshoppers and refundees are both large. In this region,the demand-expansion effect is dominated by the pri-mary competition-intensifying effect for the first PMGretailer in themarket (i.e., dA

〈1, 0〉 < d i〈0, 0〉). Thus,no retailer

has an incentive to switch to the PMG strategy whenits competitor is a non-PMG retailer. However, sinced i〈1, 1〉 > dB

〈1, 0〉 , the demand-expansion effect a retailerfaces by offering PMG is stronger than the primarycompetition-intensifying effect when the competitor isalready a PMG retailer. As a result, a retailer is bet-ter (worse) off by offering PMG when its competitoralready does so when v/c < hB (v/c > hB). Thus, both〈0, 0〉 and 〈1, 1〉 are possible equilibriawhen the ratio ofproduct valuation to search cost is low (i.e., v/c < hB)

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017

, at 1

8:46

. Fo

r pe

rson

al u

se o

nly,

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved.

Jiang, Kumar, and Ratchford: Price-Matching Guarantees with Endogenous Consumer Search3502 Management Science, 2017, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 3489–3513, ©2016 INFORMS

and 〈0, 0〉 is the unique equilibrium when the ratio ofproduct valuation to search cost is high (i.e., v/c > hB).Lastly, region (III) arises when the size of shop-

pers is large while the size of refundees is small(dA〈1,0〉 < d i

〈0,0〉 and d i〈1,1〉 < dB

〈1,0〉). When the size of shop-pers is large, the primary competition-intensifyingeffect is strong. Since the size of refundees is small,the demand-expansion effect is weak. In this region,the primary competition-intensifying effect domin-ates the demand-expansion effect and neither retailerhas the incentive to offer PMG in equilibrium. The sec-ondary competition-intensifying effect has no impacton the equilibrium outcome in this region.As a robustness check, we also characterize the equi-

librium outcome in extreme cases when each of thethree consumer segments is set to zero. When the sizeof shoppers is zero, retailers haven no incentive to com-pete on prices and thus charge the product valuationv in equilibrium. Since refundees still weakly prefer topurchase from a PMG retailer if there is any, both retail-ers offering PMG is a weakly dominant Nash equilib-rium. When the size of refundees is zero, our modelreduces to Stahl (1989). It is easy to see that both retail-ers are indifferent to offering PMG or not in a marketwithout refundees. Finally, we consider the case whenthe size of nonshoppers is zero. In subgame 〈0, 0〉, bothretailers follow a mixed pricing strategy and obtainpositive profit because refundees behave like nonshop-pers. In subgames 〈1, 0〉 and 〈1, 1〉, fierce competitionfor shoppers will drive the retail price and retail profitdown to zero. Thus, it is a weakly dominant strategyfor retailers not to offer PMG. The above discussion issummarized in Corollary 1.7

Corollary 1. When the size of shoppers is zero, both retailersfind offering PMG aweakly dominant strategy; when the sizeof refundees is zero, retailers are indifferent to offering PMGor not; and when the size of nonshoppers is zero, not offeringPMG is a weakly dominant strategy for both retailers.

One question left unaddressed is whether retailerscan benefit from launching price check websites thatfacilitate consumers’ postpurchase search. We positthat such price check websites essentially transformsome nonshoppers into refundees by increasing theproportion of consumers who have low postpurchasesearch cost. In Result 1, we lay out the conditions underwhich retailers have the incentive to do so.

Result 1. In the asymmetric equilibrium, the profit ofthe PMG retailer first increases and then decreaseswith the size of refundees while holding the size ofshoppers constant.

Our numerical analysis indicates that there existsan inverted-U relationship between the PMG retailer’sprofit and the size of refundees while holding the size

of shoppers constant. Thus, when the size of refundeesis still small, retailers may benefit from providingprice check websites to facilitate consumers’ postpur-chase search in the asymmetric equilibrium. On theone hand, the price check website increases the overallextent of consumer search and thus magnifies the pri-mary and secondary competition-intensifying effectsof PMG. On the other hand, the demand-expansioneffect of PMG also becomes stronger as the size ofrefundees increases. We show that, when the size ofrefundees is small, the latter dominates the former andthe PMG retailer is better off with the price check tech-nology in the asymmetric equilibrium. At the sametime, technology that facilitates consumers’ postpur-chase search works to the detriment of the non-PMGretailer in the asymmetric equilibrium because it notonly intensifies price competition but also lowers thenon-PMG retailer’s demand. In addition, retailers inequilibrium 〈1, 1〉 do not find it profitable to offer theprice check technology because it intensifies price com-petition without any contribution to the demand (bothretailers still evenly split the market).

4. Price-Beating GuaranteesIn this section we discuss how our model can be ex-tended to the case of price-beating guarantees (PBGs).Following the previous literature (e.g., Hviid andShaffer 2012, Corts 1997), we consider PBGs throughwhich retailers beat competitors’ prices by a percentageρ (ρ > 0) of the price difference. Here ρ can be inter-preted as the refund depth. In the special case whenρ � 0, our PBG model reduces to the PMG case.In solving this game, we use backward induction

as in Section 3. In stage 3, consumers’ equilibriumshopping behavior characterized in Proposition 1 stillholds in the case of PBG.8 In stage 2, while subgame〈0, 0〉 remains unaffected, PBG influences the equilib-rium pricing strategies in subgames 〈1, 1〉 and 〈1, 0〉by shifting the effective price refundees pay. Giventhat retailer A is a PBG retailer, let us consider theprofit of retailer A when it charges a price of pA.The effective price refundees pay when they purchasefrom retailer A is pA − maxpB∈ΣB

S{(1 + ρ)(pA − pB), 0}

where pB is the price charged by retailer B chosenfrom the strategy set ΣB

S . If retailer A charges a lowerprice than B, then refundees still pay pA. Otherwise, ifretailer A is undercut by retailer B, refundees pay pA

less the refund, which is (1 + ρ)(pA − pB). Then wecan write down both retailers’ profit functions in sub-games 〈1, 1〉 and 〈1, 0〉 and solve for the equilibriumoutcomes accordingly (see the proof of Lemma 7 in theappendix for details). This part of the result is reportedin Lemma 7.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

info

rms.

org

by [

73.1

52.1

26.1

54]

on 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2017