Persistent Neuropathy and Hyperkeratosis from Distant Arsenic Exposure

-

Upload

jean-small -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of Persistent Neuropathy and Hyperkeratosis from Distant Arsenic Exposure

This article was downloaded by: [UNAM Ciudad Universitaria]On: 21 December 2014, At: 13:30Publisher: Taylor & FrancisInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of AgromedicinePublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wagr20

Persistent Neuropathy andHyperkeratosis from Distant ArsenicExposureBeth A. Baker MD, MPH a , Andrew R. Topliff MD b , Rita B. MessingPhD c , Deborah Durkin MS c & Jean Small Johnson PhD ca Occupational and Environmental Medicine , Regions MedicalCenter , St. Paul, MN, USAb Hennepin Regional Poison Center-Hennepin County MedicalCenter , Minneapolis, MN, USAc Minnesota Department of Health , Division of EnvironmentalHealth , St. Paul, MN, USAPublished online: 11 Oct 2008.

To cite this article: Beth A. Baker MD, MPH , Andrew R. Topliff MD , Rita B. Messing PhD , DeborahDurkin MS & Jean Small Johnson PhD (2005) Persistent Neuropathy and Hyperkeratosis from DistantArsenic Exposure, Journal of Agromedicine, 10:4, 43-54, DOI: 10.1300/J096v10n04_07

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J096v10n04_07

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UN

AM

Ciu

dad

Uni

vers

itari

a] a

t 13:

30 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2014

Persistent Neuropathy and Hyperkeratosisfrom Distant Arsenic Exposure

Beth A. Baker, MD, MPHAndrew R. Topliff, MDRita B. Messing, PhDDeborah Durkin, MS

Jean Small Johnson, PhD

ABSTRACT. The purpose of this case series is to assess long-term sequelae of arsenic exposure ina cohort acutely exposed to arsenic in drinking water from a well dug into a landfill containing ar-senical pesticides. Ten of the 13 individuals (or next of kin) in the initial study agreed to participatein the follow-up study. Next of kin provided questionnaire data and released medical informationon the three individuals who had died. The remaining seven cohort members were assessed by aninterview, questionnaire, detailed physical examination and sensory nerve testing. Available med-ical records were obtained and reviewed. Sensory testing was performed using an automatedelectrodiagnostic sensory Nerve Conduction Threshold (sNCT®) evaluation. Sensory complaintsand electrodiagnostic findings consistent with polyneuropathy were found in a minority (3/7) ofsubjects 28 years after an acute toxic arsenic exposure. Two of the seven patients examined (1 of 3with neuropathic findings) also had hyperkeratotic lesions consistent with arsenic toxicity and oneof the patients had hyperpigmentation on their lower extremities possibly consistent with arsenictoxicity. [Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH.E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2005 byThe Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.]

KEYWORDS. Arsenic, neuropathy, polyneuropathy, hyperkeratosis

INTRODUCTION

Arsenic exposure may cause a variety ofhealth effects such as peripheral neuropathies,skin disorders and multiple other health ef-fects,1-12 yet the long-term sequelae of arsenicexposure in drinking water have been poorly

described in the United States. Elevated levelsof arsenic are found in drinking water in manyparts of the world such as Bangladesh, India,China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Pakistan, Nepal,Iran, Taiwan, Japan, Argentina, New Zealand,Mexico, Chile and the United States.10,11,13

Nine million people in Bangladesh and West

Beth A. Baker is Residency Director, Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Regions Medical Center, St.Paul, MN.

Andrew R. Topliff is Associate Medical Director, Hennepin Regional Poison Center-Hennepin County MedicalCenter, Minneapolis, MN.

Rita B. Messing, Deborah Durkin, and Jean Small Johnson are affiliated with the Minnesota Department ofHealth, Division of Environmental Health, St. Paul, MN.

Address correspondence to: Beth A. Baker, MD, MPH, Residency Director, Occupational and Environmental Medi-cine, Regions Medical Center, 640 Jackson Street, St. Paul, MN 55101 (E-mail: [email protected]).

Journal of Agromedicine, Vol. 10(4) 2005Available online at http://www.haworthpress.com/web/JA

© 2005 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.doi:10.1300/J096v10n04_07 43

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UN

AM

Ciu

dad

Uni

vers

itari

a] a

t 13:

30 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2014

Bengal, India, are at risk to develop signs of ar-senic toxicity.12,14,16 The largest arsenic watercontamination event occurred in Bangladeshand West Bengal, India, after thousands of tubewells dug in the 1970s were found to containhigh levels of arsenic.10-17 The main source ofarsenic in the Bengal delta plain is arsenic con-taining alluvial sediments that are deposited bythe Ganges, Brahmaputra, Meghna, and otherrivers.12

The most common source of elevated ar-senic in drinking water is natural geologicalsources, but contamination may also be due toindustrial sources such as mine tailings, smelt-ing, and pesticides.2,12 Arsenic is found in theearth’s crust primarily as inorganic arsenic andis a contaminant of a variety of metal ores.2,18,19

Elevated drinking water arsenic is a major con-cern in the United States. The U.S. Environ-mental Protection Agency (EPA) has loweredits permissible level of drinking water arsenicfrom 50 ppb to 10 ppb, the World Health Orga-nization standard.8,9,12,20 Arsenic is used insemiconductor production (gallium arsenide),and pigment and glass manufacturing. Arsenicis extracted during smelting of copper, gold,leadandzinc.19 Many arsenic-containingpesti-cides and ant poisons have been discontinuedor restricted in the United States, but these pes-ticides are used in other parts of the world.Arsenic exposure occurs in the United Statesthrough contact with arsenic-containing pesti-cides still in use, stored old arsenical pesticidesand ant poisons, drinking water, exposure to ar-senic-treated wood and industrial processes.12

Arsenic may also be used as a wood preserva-tive (copper chromated arsenate) and in animalfeed.12 Most of the arsenic in the environmentis inorganic arsenic. Seafood or shellfish maycontain organic arsenic that is considerednon-toxic.2,12,14,19

Arsenic is readily absorbed by gastrointes-tinal tract and inhalation and poorly absorbedthrough dermal routes.2,12,18,19 Arsenic im-pairs cellular respiration by inhibiting morethan 200 enzymes throughout the body includingsulfhydryl group containing enzymes in high-energy compounds.12,19,21,22 Acute arsenic poi-soning causes primarily gastrointestinal symp-toms such as abdominal pain, nausea andvomiting and diarrhea.1,2,11,12,23 Patients mayalso develop shock, elevated liver function

tests, hepatomegaly, respiratory symptoms,acute tubular necrosis, delirium seizures,coma and death.2,11,12 Arsenic was one of theearliest identified carcinogens. Arsenic ex-posure has been linked to increased rates ofskin and lung cancer and in some studies tohepatic angiosarcomas, liver, bladder, and kidneycancers.2,11,12,13,19

Long term sequelae of arsenic poisoninginclude peripheral neuropathy, cancers, andskin changes.2,12,13,19,21,24 Neurological prob-lems caused by arsenic toxicity include pe-ripheral neuropathies, fatigue, central nervoussystem depression, tremulousness, ataxia andincoordination.2-6 Arsenic-induced peripheralneuropathy is a symmetric demyelinating pe-ripheral neuropathy involving the larger diam-eter neurons and results in abnormal electro-diagnostic findings.1-4,6,8,23,25 Sensory findingsusually predominate but muscle weakness mayalso be seen.2-7,10-12,26-28 Arsenic-induced neu-ropathy has persisted in some individuals upto nine years after exposure.1-3,5-8,11,25-28 Im-provement in the neuropathy may occur in themonths following exposure but recovery isoften incomplete.2,6,23,27,28 Many prior studiesof arsenic neuropathy involved patients withchronic exposure and it is difficult to quantifywhen the exposure ceased in some of thesestudies and also how long the neuropathy per-sisted after the exposure ceased.10 Mukherjeeet al. found peripheral neuropathy was themost common neurological complication(37.3-86.8% of patients) in subjects withchronic arsenic positioning in West Bengal,India.10 Arsenic-induced skin changes mayinclude hyperpigmentation,hypopigmentation,hyperkeratosis,Bowen’s disease, squamouscellcancers, basal cell cancers, or Blackfoot’s dis-ease (a form of arsenic-induced peripheral vas-cular disease resulting in gangrene).2,11,13,14,19,

21,29 Arsenical skin lesions were present in 24%to 61% of villagers drinking arsenic containingwater in Bangladesh and West BengalIndia.15,17,30

This study represents a unique opportunityto evaluate the long-term effects 28 years afteran acute arsenic exposure in a well-definedcohort. This case series describes the long-termsequelae of arsenic exposure in a cohort 28years later. Thirteen individuals were exposedto large amounts of arsenic by drinking con-

44 JOURNAL OF AGROMEDICINE

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UN

AM

Ciu

dad

Uni

vers

itari

a] a

t 13:

30 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2014

taminated well water in Perham, Minnesotafrom May to July in 1978 as described byFeinglass in the New England Journal of Medi-cine.1 This location became one of the firstSuperfund sites in Minnesota. At that time, acompany well had been inadvertently drilledthrough soil that contained arsenic-laced grass-hopper bait. The water contained 11,800 to21,000 parts per billion of arsenic (permissiblelevel at that time was 50 parts per billion).Eleven of 13 exposed employees initially com-plainedof symptoms.Nineof13complainedofgastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea,vomiting, abdominal pain or diarrhea. Two ofthe three treated employees had elevated urinearsenic levels (although the exact urine levelsare not provided in the Feinglass paper) andthese two were treated with British Anti-Lewisite (BAL).1 Anecdotal reports of subse-quent neurological problems in these individu-als have appeared in a subsequent 1996Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA)report.31

METHODS

Hennepin County Medical Center Institu-tional Review Board approval was obtainedand attempts were made to contact the thirteencohort members from the original study byFeinglass.1 A list of the original 13 individualswas obtained from the Minnesota Departmentof Health. Individuals were traced using publicMinnesota Department of Health records,phone listings and by personal contact with oneof the thirteen individuals. These individuals ortheir families were contacted by letter and in-vited to participate in a phone interview. Writ-ten informed consent was obtained for all par-ticipants and prior medical records were thenreviewed. A phone interview was performed toobtain demographic data, symptoms at time ofinitial exposure, and past medical history.

Each patient or next of kin was asked duringthe phone interview whether the cohort mem-ber had specific comorbid medical conditionssuch as diabetes or prior exposures to otherneurotoxins such as alcohol, heavy metals, pes-ticides, medications. Patients or next of kinwere asked to list job titles, occupations andusual job duties since 1972 to assess the origi-

nal cohort’s subsequent occupational expo-sure. Patientsor nextof kinwere asked if cohortmembers worked in industries with arsenic ex-posure, lead exposures, mines, quarries, found-ries, metal fabrication, or tanning factories.Patients or next of kin were asked if cohortmembers were exposed to any of the followingpotentially neurotoxic chemicals or com-pounds: wood preservatives, herbicides, lead,arsenic, mercury, thallium, solvents, and n-hexane. Patients or next of kin were also askedif the original cohort had diabetes and whetherthey used insulin or had developed complica-tions from the diabetes. Patients or next of kinwere also asked if they had any of the follow-ing neurologic conditions: Lyme disease,carpal tunnel syndrome, pinched nerve inthe neck, pinched nerve in the back, Bell’spalsy, neuropathy, Guillain Barre Syndrome,monoclonal gammopathy, chronic inflamma-tory demyelinating neuropathy, Chariot MarieTooth Syndrome, vitamin B12 deficiency, fo-late deficiency or other neurologic diseases.Patients or next of kin were also asked if theyhad been exposed to a list of potentiallyneurotoxic medication. Alcohol consumptionwas quantified by average number of drinks perday and length of alcohol consumption. Homevisits were conducted to obtain additional medi-cal information and perform a detailed physicalexamination including a comprehensive neuro-logical exam assessing cranial nerves, cerebel-lar function, motor strength and reflex testing.

Formal EMG/Nerve Conduction Velocitytesting was considered too invasive and poten-tially painful to be performed in the home. How-ever sensory testing was performed and includedsharp versus dull discrimination, proprioception,vibratory sense, and two-point discrimination.Theelectrodiagnostic sensoryNerveConductionThreshold (sNCT®) test was used as a surrogatemeasure of objective peripheral sensory nervefunction. The automated neuroselective sNCTevaluation was used to obtain painless CurrentPerceptionThreshold(CPT)measuresofsensoryfunction from the peripheral nerve to the centralnervous system.32,33

An automated double blind forced choicetesting procedure determined CPT measures towithin ±20 µAmperes (p < .006) for 3 frequen-cies of stimulation (2000 Hz, 250 Hz and 5 Hz).

Reviews, Case Histories 45

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UN

AM

Ciu

dad

Uni

vers

itari

a] a

t 13:

30 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2014

CPT measures were done at standardized cuta-neous test sites bilaterally at the distal phalangeof the ring finger (median, ulnar nerves,C7/C8), distal phalange of the great toe (super-ficial peroneal, deep peroneal nerves, L4/L5),and skin just in front of the ear (trigeminalnerve) were determined. CPT measures wereevaluated based on previously described para-metric analysis that determined if the CPT val-ues were abnormal based on comparison withthe established normative database.32-35

The sNCT/CPT has been used in prior stud-ies to assess peripheral neuropathies secondarytometabolicconditions,36-38 toxicexposures,39-43

and other diseases.44,45 Prior studies assessingperipheral neuropathies have shown the sNCThas a sensitivity of 23-94% (sensitivity wasgreater than 54% in 5/6 studies) and a specific-ity of 88-100%.46-50 Sensitivity of sNCT/CPTimproved if multiple sites were tested and thisstudy used three sites: ring finger, great toe andface.51 Sensitivity was 54-94% and specificitywas 95-100% in prior studies of diabetic pa-tients which is the most common type of pe-ripheral neuropathy studied.48,49,51,52 Biophys-ical considerations and indirect evidence suggestthat the 2000 Hz stimulus measures primarilylarge myelinated fiber activation, the 250 Hzstimulus measures small myelinated fiber acti-vation and the 5 Hz stimulus measures smallunmyelinated fiber activation.32-35,51

RESULTS

Ten of the original 13 individuals or theirnext of kin from Feinglass’ original cohortwere located.1 Seven of the initial cohort andthree of the families of deceased members ofthe cohort agreed to participate in the study.Three of the 10 individuals were deceased sonext of kin was contacted to obtain consent andrelease for medical records. These next of kinagreed to provide proxy information on the de-ceased individual which was then collected bya phone interview. Seven of the cohort who hadsNCT/CPT testing were between the ages of 42and 48; one individual was 63. Results of thephone interviews, home visit, and physical ex-amination and sNCT/CPT tests are summarizedin Table 1.

Three of seven patients tested with thesNCT/CPT testing had abnormal myelinatedfiber function at one or more sites tested consis-tent with arsenic-induced polyneuropathy (pa-tients 1, 6, 7). Patient 1 had elevated urine ar-senic initially according to Feinglass and hewas treated with British Anti Leuwisite (BAL)although his actual urine arsenic level is notcited in the paper.1 Patient 7 had hair arsenic of800 u/100 g and no hair or urine arsenic resultsare given for Patient 6 in Feinglass’s originalpaper.1 See Table 2 for a summary of the origi-nal cohort arsenic levels and symptoms at thetime of Feinglass’s original study. The threepatients with abnormal SNCT/CPT results hadsensory symptoms at the time of this follow-upstudy. However, only one of these three sub-jects had findings of a sensory abnormality onphysical exam (Patient 1). Two of the three em-ployees who were most symptomatic and had aperipheral neuropathy at the time of the initialstudy in 1973 were still living and participatedin the full study (Patient 1, 2). These employeeshad primarily gastrointestinal symptoms in1973, elevated urine arsenic levels and weretreated with British Anti Leuwisite (BAL) (seeTable 2).

Each patient or next of kin was asked duringthe phone interview whether the cohort mem-ber had specific comorbid medical conditionssuch as diabetes or prior exposures to otherneurotoxins such as alcohol, heavy metals, pes-ticides, medications. None of the cohort hadwork related or non-work related arsenic expo-sure since 1972 (see Table 1). Two of the Pa-tients (Patients 1 and 9) mentioned a history ofdiabetes.Patient10wasdeceasedandhadahis-tory of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Pa-tients 3 and 7 had a history of seizures. Noneof the cohort used a water supply that had higharsenic or that had been tested for arsenic after1973 according to their self-report. None of thecohort used natural medicines or homeopathicmedications that may contain arsenic such asFowlers Solution, Asiatic Pill, Kasha YellowRoot Tea, or Kelp.

Patient 1, a 63-year-old male, was the mostseverely effected of employees in the initial1973 study and he had an elevated urine arseniclevel.1 He noted persistent numbness since theinitial exposure, more marked in his lowerextremity. He also complains of diffuse weak-

46 JOURNAL OF AGROMEDICINE

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UN

AM

Ciu

dad

Uni

vers

itari

a] a

t 13:

30 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2014

Reviews, Case Histories 47

TABLE 1. Summary of arsenic exposed individual results

Patient InitialSymptoms

InitialTesting andTreatment

CurrentComplaints

Past MedicalHistory andExposures

Physical Examination Neurometer®sNCT/CPTResults

Patient 1 Nausea &vomiting,numbness infeet,clumsiness inlegs

Serum tests,BAL1

NumbnessLE>UE2,weakness,Skin lesions

Diabetes since1990, +EMG3- ’72,’78,’79Alcohol

Absent sensation anddecreased strength inlegs, absent anklereflexes, hyperkeratoticlesions on calves, feet

Profoundsensory lossboth great toes,severe sensoryloss bilateralface

Patient 2 Flu likesymptoms,numbness inhands and feet,weakness

Hair and nail,BAL1

HTN4,numbness infeet

L4-5laminectomy,

Hyperpigmented lesionsboth legs, hyperkeratosison soles

Very mildsensory loss Rgreat toe

Patient 3 Vomiting,malaise,fatigue,weakness, flulike symptoms

Hair and nail,BAL

Deceased Seizures since1961,

Not done (deceased) Deceased

Patient 4 Nausea andvomiting

Hair and nail Edgy andnervous

S/P5

laminectomyAlopecia over occiput withhyperpigmented,hyperkeratotic lesion onscalp

Mild sensorydysfunctionbilateral face

Patient 5 Vomiting,stomachcramps

Hair and nail Numbness Rhand, R legweakness,trouble withbalance

HerbicideExposure

Normal Very mildsensory loss Lring finger

Patient 6 Vomiting Mild numbnesshands and feet

Fracture ofL4-5, Possiblelead exposures

Normal Very mildsensory lossboth great toes,Sensorydysfunction Lring finger, Rface

Patient 7 Vomiting Numbness bothhands

Closed headinjury, seizures,S/Pcraniotomy,Possible lead

Hyperpigmented lesionson calves, Visual field lossL eye

Very mild tomoderatesensory lossboth great toes,Sensorydysfunctionboth ring fingers,R face

Patient 8 Flu like,vomiting

Numbness R3-4th finger

Normal Severe sensoryloss R greattoe, mildsensory loss Rring finger

Patient 9 Vomiting Deceased IDDM6 Not done Deceased

Patient 10 None Deceased ALS7 Not done Deceased

1 BAL = British Anti-Leuwisite2 LU = Lower extremity, UE = Upper extremity3 EMG = Electromyelogram4 HTN = Hypertension5 S/P = Status Post6 IDDM = Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus7 ALS = Amylotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UN

AM

Ciu

dad

Uni

vers

itari

a] a

t 13:

30 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2014

ness. In 1972 he had gastrointestinal symptomsand had decreased sensation in his feet, in-creased clumsiness, tremulousness and weak-ness. He was treated with BAL with little im-provement in his neurological symptoms.Twenty-eight years later, his neurologicalsymptoms had improved slightly since the ex-posure. He has had positive formal EMGs forperipheral neuropathy in 1972, 1978 and 1979.He was diagnosed with diabetes in 1990 andstarted insulin in 1997. On physical examina-tion, he had the hyperpigmented and hyper-keratotic lesions on his calves, feet and solesand hyperpigmented areas on his anteriorcalves. He had absent proprioception, pinprickperception or vibration sense in his lower ex-tremities on physical examination. His motorstrength was significantly decreased in hislower extremities, as were his deep tendon re-flexes. On sNCT/CPT testing, this patient hadbilateral severe sensory changes in his trige-minal nerve and profound sensory loss in bothgreat toes.

Patient 2 is a 45-year-old male who in 1972had significant gastrointestinal symptoms,“pins and needles” sensation in his feet, andlater numbness in his hands and his feet andsome “unsteadiness.” He had elevated urine

arsenic initially and was treated with BAL1 andstill reports some persistent numbness primar-ily in his feet. He had a right-sided L4-5laminectomyfor sciatica and had been exposedto lead. Twenty-eight years later he notesnumbness over his feet. His physical exam wasnormal except for hyperkeratotic skin lesions.His sNCT/CPT testing was normal except forvery mild sensory loss in his R great toe thatwas not felt to be consistent with a diffuse pe-ripheral neuropathy. Patient 2 stated he drankone alcohol drink per day.

Patient 3 was born in 1931 and died in 1994.He was one of the three individuals with theworst symptoms following the initial exposurein 1972. Initially, he had significant gastroin-testinal effects, malaise, weakness and fatigueand was treated with BAL. Seven years afterthe exposure, he had a formal EMG that re-vealed mild sensory deficits in his right arm inthe ulnar nerve distribution but reportedly didnot show a peripheral neuropathy.

Patient 6, a 42-year-old male, also had initialflu-like symptoms and vomiting symptoms.No urine or hair arsenic results were given forpatient 6 in the initial Feinglass paper.1 He hada prior L4-L5 vertebral fracture and now com-plains of occasional left leg pain. His physical

48 JOURNAL OF AGROMEDICINE

TABLE 2. Arsenic levels and acute and subacute symptoms following initial exposure (adapted fromFeinglass, NEJM, 19731)

PatientNumber

Hair arseniclevel (µg/100 gm)or urine level

Estimated # cupswater consumed

Number of acuteSymptoms

Treatment Subacute orchronic symptoms

1 Urine level obtained 245 6 BAL GI symptoms,neuropathy,Mees lines

2 Urine level obtained 200 4 BAL Mees lines,neuropathy

3 1680 160 4 Neuropathy

4 660 85 3

5 140 85 3

6 60 3

7 800 50 2

8 210 50 2

9 35 0

10 <10 20 1

11 15 0

12 <10 15 2

13 37 10 1

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UN

AM

Ciu

dad

Uni

vers

itari

a] a

t 13:

30 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2014

exam was normal. He had prior lead exposureand does drink alcohol. His SNCT/CPT testingshowed a very mild sensory loss condition ingreat toes, left ring finger and his righttrigeminal nerve. Patient 6 mentioned that hedrank less than one drink a day and was ex-posed to lead for less than one year after 1972.He had worked in a foundry for three to fouryears and had some exposure to wood preser-vatives.

Patient 7 is a 48-year-old male who initiallyhad vomiting and GI symptoms and a hairarsenic level of 800 µg/100 gm.1 Twenty-eightyears later he had hyperpigmented lesions onhis calves and visual loss in his left eye. He hada closed head injury and a craniotomy in 1992and had a history of seizures. He notes occa-sional numbness in both hands. His sNCT/CPTtesting showed mild sensory loss in both greattoes, both ring fingers and the right trigeminalnerve. Patient 7 stated he rarely drank alcoholand drank approximately 12 beers in one yearand had been exposed to lead for six years.

DISCUSSION

In the initial cohort described by Feinglass,11 of 13 exposed employees initially com-plained of symptoms (see Table 2).1 Nine of 13complained of gastrointestinal symptoms suchas nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain or diar-rhea. This cohort had primarily gastrointestinalcomplaints which is consistent with the pub-lished literature description of acute arsenicpoisoning.1,2,6,11,12,16,22,23 Three of the 13 ex-posed individuals (patients 1, 2, and 3) had sub-acute or chronic symptoms several months af-ter the initial exposure.1 These three individualshad peripheral neuropathy at the time ofFeinglass’s study and appeared to have thehighest exposure dose as estimated by cups ofwater consumed (Table 2). In our follow-upstudy, patient one had persistent peripheralneuropathy and hyperkeratotic lesions on hissoles and legs consistent with arsenic poison-ing. Patient 2 also had hyperkeratotic lesionsbut no evidence of neuropathy by sNCT/CPTtesting. Two additional patients (patient 6, 7)had persistent numbness and sNCT/CPT ab-normalities that may be consistent with a pe-ripheral neuropathy. These two patients were

asymptomatic at the time of Feinglass’s fol-low-up several months after the exposure butthey had initial symptoms and one of the twohad elevated hair arsenic (800 µg/100 gm).

Long term sequelae of arsenic poisoning in-clude peripheral neuropathy, cancers, and skinchanges.2,11,12,13,19,21,24 None of the 10 patientsevaluated 28 years after exposure had devel-oped cancer types that have been associatedwith an arsenic exposure. This study did notinclude an external control group. Long-termneurologic effects were assessed by physicalexamination and sNCT/CPT testing. Severalconfounding factors which could not be con-trolled for in this study included; risk factors forneuropathy such as diabetes, ethanol consump-tion, and exposure to other toxins. This cohortdid not report any subsequent occupational orenvironmental exposure to arsenic after 1972on their questionnaires. Although we assumethat the cohort was only exposed to arsenic for ashort time in 1972, it is possible that they hadsubsequent arsenic exposure through drinkingwater or other sources. Two of the three partici-pants who were most severely affect in 1973(positive hair arsenic) had persistent hyper-keratotic change consistent with arsenic expo-sure (one also had persistent neuropathy) andother confounders such as diabetes, hypo-thyroidism, laminectomy, lead exposure, orethanol consumption would not cause thesecharacteristic hyperkeratotic changes. An ad-ditional factor that was not controlled for wasthe patient’s age. Loss of myelinated fiberfunction occurs with increasing age, whichmay compound any large fiber neurotoxic ef-fects.52,53 It is possible that the abnormalsNCT/CPT studies are due to subsequent occu-pational or residential toxic exposures or medi-cal conditions that occurred since the initial ex-posure. Patients6and7didnothavecharacteristichyperkeratotic skin lesions but both had periph-eral neuropathy by sNCT/CPT on follow-uptesting. Both patients 6 and 7 were exposed tolead and drank alcohol that may contribute totheirperipheralneuropathy.Patient2alsohadahistory of lead exposure but did not have a pe-ripheral neuropathy on follow-up testing.

Formal EMG/Nerve Conduction Velocitytesting was considered too invasive and poten-tially painful to be performed in the home.However sensory testing was performed and

Reviews, Case Histories 49

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UN

AM

Ciu

dad

Uni

vers

itari

a] a

t 13:

30 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2014

included sharp versus dull discrimination,proprioception, vibratory sense, and two-pointdiscrimination. The electrodiagnostic sensoryNerve Conduction Threshold (sNCT®) testwas used as a surrogate measure of objectiveperipheral sensory nerve function. The auto-mated neuroselective sNCT evaluation wasused to obtain painless Current PerceptionThreshold (CPT) measures of sensory functionfrom the peripheral nerve to the central nervoussystem.32,33 The results from each individual’ssNCT/CPT testing were compared to norma-tive data for subjects’ age 16 to 88.51 We hadhoped to compare the least symptomatic mem-bers of the initial cohort to those who had moresymptoms and persistent subacute or chronicfindings at the time of Feinglass’s initial study.Five of the initial exposed cohort were rela-tivelyasymptomaticat the timeof the initial ex-posure (one or fewer symptoms), had no sub-acute or chronic symptoms and had normal hairarsenic levels (see Table2). Unfortunatelyonlytwo of these five patients (patients 9, 10) wereavailable to be included in the follow up studyand both were deceased so no physical exami-nation findings or SNCT/CPT results wereavailable on these patients. These patients (pa-tients 9, 10) did not have persistent neurologicsymptoms or history of neuropathy accordingto their next of kin but no physical examinationor nerve conduction testing is available to ver-ify this proxy information.

Three of seven patients tested with theSNCT/CPT testing had changes consistentwith a peripheral neuropathy (patient 1, 6, and7). The patient who had the most severe symp-toms at the time of the original study in 1972had the most severe sensory loss on physicalexam and on neurosensory testing 28 years af-ter exposure. He had documented peripheralneuropathy by multiple prior EMG’s (1972,1978, 1979 and eventually developed diabetesin 1990. This severely affected patient also hadhyperkeratotic skin lesions over his lower ex-tremities and soles 28 years after the initial ex-posure which is consistent with his prior ar-senic exposure. It is possible that his diabetesmay contribute to his current peripheral neu-ropathy but he clearly had multiple positiveEMGs long before the diabetes developed andhis hyperkeratotic skin changes are also consis-tent with his distant arsenic exposure. In addi-

tion, many diabetic neuropathies show in-volvement of both large and small nerve fibersby sNCT/CPT testing with both hypoesthesiaand hyperesthesia on exam but patient 1 had nohyperesthesia and sNCT/CPT changes in-volved primarily large nerve fibers.48,49,51,52

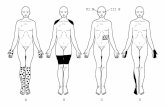

Patient 1 and patient 2, two of the three patientsmost severely affected at the time of the 1972study, had persistent hyperpigmented and/orhyperkeratotic lesions after exposure. Onlyone of the three most severely affected patientsin the initial cohort had evidence of persistentperipheral neuropathy but this patient had themost severe symptoms initially (one of thethree was deceased so no physical examinationor follow-up neurologic testing could be per-formed). Two of the three patients with persis-tent peripheral neuropathy changes 28 yearslater had primarily gastrointestinal symptomsat the time of exposure with minimal neurolog-ical symptoms. All three patients with persis-tent peripheral neuropathy had other possiblecauses of persistentneuropathy (diabetes, alco-hol use, or possible lead exposure). Two pa-tients had hyperkeratotic lesions on their lowerextremities (patients 1, 2) and one patient hadhyperpigmented lesions on his legs consistentwith possible arsenic exposure.

Although numerous studies describe signsand symptoms after acute arsenic exposure,few studies evaluate how long these symptomspersist once the exposure has stopped. In ourstudy, one of the three individuals (33%) whohad the most severe acute symptoms had signsof peripheralneuropathy28 years after an acuteexposure and also had characteristic hyper-keratotic skin lesions consistent with arsenicexposure. Two additional patients in our studyhad neurologic symptoms and sNCT/CPTfindings consistent with a peripheral neuropa-thy but both of these patients were reportedlyrelatively asymptomatic at the time of the ini-tial follow-up in Feinglass’s study. Chhuttaniet al. reviewed 41 patients with arsenical neu-ropathy and found characteristic skin changesin 65% of neuropathy patients.3 Only six of 41patients (14%) fully recovered over a period of40 days to five years, 58.5% showed a partialrecovery and 26.8% showed a marked to mod-erate recovery during follow-up period of 40days to five years.3 Franzblau and Lilis de-scribed one patient with persistent peripheral

50 JOURNAL OF AGROMEDICINE

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UN

AM

Ciu

dad

Uni

vers

itari

a] a

t 13:

30 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2014

neuropathy six months after exposure to wellwater containing elevated arsenic from minetailings in upstate New York.23 Lagerkvist andZetterland showed persistent peripheral neu-ropathy in seven workers with long-term ar-senic exposure five years after exposure.25

LeQuesne et al. found persistent neurologicsymptoms in three of four patients six to nine ofnine patientswith arsenic neuropathy noted on-going symptoms nine years after the initialexposure in a study by Oh et al.28

Peripheral neuropathies were the most com-mon neurological complicationaffecting37.7%to 86.8% of patients with arsenical skin lesionsandpositivebiomarkers in theWestBengal, In-dia study by Mukherjee et al.10 The Bangladeshand West Bengal, India cohort will serve to elu-cidate and describe the effects of chronic ar-senic drinking water contamination but it isunclear if these results are applicable to shortterm, acute arsenic exposure. In our study, twoof the most severely affect employees weretreated with BAL and did not feel that the BALimproved their neurologic symptoms. One ofthe two patients treated with BAL noted persis-tent numbness and peripheral neuropathy. Theother patient complained of persistent numb-ness in his feet but his sNCT/CPT results werenot felt to be consistent with a peripheral neu-ropathy. The primary treatment for arsenic tox-icity is removal of the patient from future sig-nificant arsenic exposure. Arsenic levels willfall within several weeks after the patient is re-moved from exposure. Urinary arsenic hasbeen regarded as the most reliable indicator ofrecent inorganic arsenic exposure and 60-75%of the dose is excreted through the urine withina few days.2,13,18,21 Complete elimination of in-organic arsenic may take 10 days after singledose or up to 70 days after repeated use.2,22

Chelation therapy is recommended only forthose patients with significant symptoms or ex-tremely high arsenic levels.2,21,29,30 Supportivecare is important for patients with acute andchronic toxicity. Patients can also receive che-lating agents that will reduce the level of ar-senic in the body. In the past, British Anti-Leuwisite (BAL) and Penicillamine were themainchelator.21 Chelation treatmentappears tobe more effective for acute symptoms than forchronic peripheral neuropathy. In the study byChhuttani et al., treatment with BAL did not

significantly increase the number who notedmoderate to full recovery from peripheralneuropathy, as 10/20 (50%) treated withBAL had moderate to full recovery and 8/20(40%) not treated with BAL had similar re-covery.3 Penicillamineappears relatively inef-fective for arsenic poisoning and is no longerrecommended.19 DMSA or 2, 3- dimercapto-succinic acid is an oral chelator which is a deriva-tive of BAL that appears to be more effectivethen BAL.21 DMPS (2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulfonate) is another oral chelator derivedfrom BAL and may be more effective thanDMSA.11,21,54 Mazunder et al. found treatmentwith DMPS resulted in significant improve-ment in arsenic related symptoms but DMSAtreatment was no better than placebo.11 Unfor-tunately chelation treatment appears relativelyineffective for peripheral neuropathy althougha case report suggested DMPS may result indramatic improvement.54 If water contamina-tion is suspected as the source of arsenic, thenthe water arsenic levels should be tested. If thedrinking water contains elevated levels of ar-senic then an alternative source of drinking wa-ter should be sought or a filtration system maybe considered.

There are several biomarkers available to as-sess arsenic exposure. Arsenic may be stored inhair and hair arsenic was obtained in eight indi-viduals in the initial Feinglass study to assessthis cohort for arsenic exposure.1 The two mostseverely affected employees in the initial co-hort who were treated with BAL had elevatedurine arsenic levels (although the exact urinelevels are not provided in the Feinglass paper)and these two were treated with British AntiLewisite (BAL) (see Table 2). One of the au-thors contacted Dr. Feinglass to see if the initialstudy documents or original data was availablelisting the urine concentrations or the exactacute symptoms that each subject experienced.Unfortunately the initial study documents werenot available 28 years later. Only three of thecohort showed signs of subacute or chronicsymptoms two months after the exposure andthe remaining 10 were asymptomatic (seeTable 2). The third patient who was symptom-atic two months after the initial exposure hadhair arsenicof 1680 µg/100g.1 Hair arsenic lev-els were measured in eight employees and lev-els and five had elevated hair arsenic levels (37

Reviews, Case Histories 51

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UN

AM

Ciu

dad

Uni

vers

itari

a] a

t 13:

30 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2014

to 1680 µg/100 gram).1 Normal hair arsenicvaries from lab to lab but is usually defined as <1 µg/gm.24

Urinary arsenic has been regarded as themost reliable indicator of recent inorganic ar-senic exposure and 60-75% of the dose isexcreted through the urine within a fewdays.13,18,21,54,55 Blood arsenic is clearedwithin hours and is of little value.2,18 Urinearsenic elimination has three phases: firstphase half-life is 2 days (65% of dose), sec-ond phase half-life is 10 days (30% of dose)and third phase half-life is 40 days (4% ofdose).55 Complete elimination of inorganicarsenic may take 10 days after single dose orup to 70 days after repeated use.2,22 Senguptaet al. found that 83% of hair samples, 93% ofnail samples and 95% of urine samples fromareas in Bangladesh with high drinking waterarsenic contained toxic levels of arsenic.16

Arsenic levels may also be assessed in hair ornails and may better reflect chronic arsenictoxicity. Hair levels however may reflectexternal contamination from water, sweat, orairborne arsenic and not internal contamina-tion or internal dose.21 Srivastava et al. foundarsenic hair concentrations did correlate withdrinking water arsenic in West Bengal, India;mean hair arsenic was 5.55 µg/gm (range2.57 µg/gm-8.85 µg/gm) in those drinkingarsenic containing drinking water versuscontrol hair arsenic level that ranged from0.09-0.2 µg/gm.56 Mandal et al. found a goodcorrelation between total hair arsenic con-centration and arsenic drinking water con-centration in West Bengal, India (R2 = 0.45, p= 0.288).18 In Feinglass’ initial study, the hairarsenic levels did appear to correlate with es-timated exposure dose (as defined by cups ofcontaminated water consumed).1 Hair growsat a rate of 0.2 to 0.5 mm/day and can serve asa measure of exposure during over precedingmonths.57 However, a recent study publishedin the Journal of the American Medical Asso-ciation (JAMA) questioned the reliabilityand utility of hair metal testing when per-formed at numerous laboratories.58 In con-trast to the JAMA study, Shamberger notedhair arsenic testing had good precision if theyavoiding washing the hair.59 Because of therisk of external contamination, the diagnosisof arsenic poisoning should not be based on

hair level alone and should include clinicalfeatures and/or urine levels.24

Currently, 24-hour urine arsenic levels arerecommended to work up an individual ex-posed to arsenic. Hair arsenic may be used (butmay be unreliable) for distant exposure.58,59 Itis suggested that 1 gm of hair be collected fromsites near the nape of the neck to minimize ex-ternal contamination.24 The date of arsenic in-gestion can sometimes be inferred from the lo-cation on the hair but this may be unreliable asarsenic uptake along the hair shaft may be in-consistent.59 Arsenic levels in hair representthe mean arsenic exposure over the past two tofive months (depending on speed of hairgrowth and length of hair).17 Nail arsenic levelsreflect arsenic exposure in the past 12 to 18months (depending on nail growth rate andlength of nail).17 No repeat urine, hair or nailsamples were collected doing this study be-cause of lack of additional funding. In addition,any arsenic values obtained 28 years after ex-posure would not reflect the arsenic exposurethat occurred 28 years previously.

In conclusion, the results of this study revealsensory complaints and electrodiagnostic find-ings consistent with axonal polyneuropathy ina minority of (3 of 7) exposed individuals andhyperkeratotic lesions in 2 of 7 exposed pa-tients (who were alive and available for a skinexamination) 28 years after toxic arsenicexposure.

REFERENCES

1. Feinglass EJ. Arsenic intoxication from well wa-ter in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1973 Apr 19;288(16):828-30.

2. Landrigan PJ. Arsenic–state of the art. Am J IndMed. 1981;2(1):5-14.

3. Chhuttani PN, Chawla LS, Sharma TD. Arsenicalneuropathy. Neurology. 1967 Mar;17:269-74.

4. Gerr F, Letz R, Ryan PB, Green RC. Neurologicaleffects of environmental exposure to arsenic in dust andsoil among humans. Neurotoxicology. 2000 Aug;21(4);475-87.

5. Blom S, Lagerkvist B, Linderholm H. Arsenic ex-posure to smelter workers. Clinical and neurophysiologicalstudies. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1985 Aug;11(4):265-9.

6. Heyman A, Pfeiffer JB Jr, Willett RW, TaylorHM. Peripheral neuropathy caused by arsenical intoxica-tion; a study of 41 cases with observations on the effects

52 JOURNAL OF AGROMEDICINE

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UN

AM

Ciu

dad

Uni

vers

itari

a] a

t 13:

30 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2014

of BAL (2,3 dimercapto-propanol). N Engl J Med. 1956Mar 1;254(9):401-9.

7. Feldman RG, Niles CA, Kelly-Hayes M, Sax DS,DixonWJ,ThompsonDJ,LandauE.Peripheral neuropa-thy in arsenic smelter workers. Neurology. 1979 Jul;29(7):939-44.

8. Le Quesne PM, McLeod JG. Peripheral neuropa-thy following a single exposure to arsenic. Clinical coursein four patients with electrophysiological and histologicalstudies. J Neurol Sci.1977 Jul;32(3):437-51.

9. Lewis DR, Southwick JW, Ouellet-Hellstrom R,Rench J, Calderon RL. Drinking water arsenic in Utah: Acohort mortality study. Environ Health Perspect. 1999May;107(5):359-65.

10. Mukherjee SC, Rahman MM, Chowdhury UK,Sengupta MK, Lodh D, Chanda CR, Saha KC, ChakrabortiD. Neuropathy in arsenic toxicity from groundwater ar-senic contamination in West Bengal, India. J Environ SciHealth A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng. 2003;A38(1):165-83.

11. Mazumder DN. Chronic Arsenic Toxicity: Clini-cal Features, Epidemiology, and Treatment: Experiencein West Bengal; J Environ Sci Health A Tox HazardSubst Environ Eng. 2003;A38(1):141-63.

12. Ratnaike RN. Acute and chronic arsenic toxicity.Postgrad Med J 2003 Jul;79(933):391-6. Review.

13.RahmanMM,SenguptaMR,AhamedS,ChowdhuryUK, Hossain MA, Das B, lodh D, Saha KC, Pati S, KaiesI, Barua AK, Chakraborti D. The magnitude of arseniccontamination in groundwater and its health effects to theinhabitants of the Jalangi–one of the 85 arsenic affectedblocks in West Bengal, India. Sci Total Environ. 2005Feb;338(3):189-200.

14. Mead MN. Arsenic: in search of an antidote to aglobal poison. Environ Health Perspect. 2005 Jun;113(6):A378-86.

15. Chowdhury UK, Biswas BK, Chowdhury TR,Samanta G, Mandal BK, Basu GC, Chanda CR, Lodh D,Saha KC, Mukherjee SK, Roy S, Kabir S, QuamruzzamanQ, Chakraborti D. Groundwater arsenic contamination inBangladesh and West Bengal, India. Environ HealthPerspect. 2000 May;108(5):393-7.

16.SenguptaMK,MukherjeeA,HossainMA,AhamedS, Rahman MM, Lodh D, Chowdhury UK, Biswas BK,Nayak B, Das B, Saha KC, Chakraborti D, MukherjeeSC, Chatterjee G, Pati S, Dutta RN, Quamruzzaman Q.Groundwater arsenic contamination in the Ganga-Padma-Meghna-Brahmaputra plain of India and Bangladesh.Arch Environ Health. 2003 Nov;58(11):701-2.

17.SamantaG,SharmaR,RoychowdhuryT,ChakrabortiD. Arsenic and other elements in hair, nails, and skin-scales of arsenic victims in West Bengal, India. Sci TotalEnviron. 2004 Jun 29;326(1-3):33-47.

18.MandalBK,OgraY,AnzaiK,SuzukiKT.Speciationof arsenic in biological samples. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol.2004 Aug 1;198(3):307-18.

19. Hall AH. Chronic arsenic poisoning.Toxicol Lett.2002 Mar 10;128(1-3):69-72. Review.

20. Annex 4, Chemical Summary Tables. In: Guide-lines for drinking-water quality. Vol 1, 3rd ed. WorldHealth Organization; 2004 [cited 2005 Sep 9]. Availablefrom: http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/dwq/en/gdwq3_ann4tab.pdf.

21. Graeme KA, Pollack CV Jr. Heavy metal toxicity,Part 1: arsenic and mercury. J Emerg Med. 1998 Jan-Feb;16(1):45-56. Review.

22. Winship KA. Toxicity of inorganic arsenic salts.Adverse Drug React Acute Poisoning Rev. 1984 Au-tumn;3(3):129-60. Review.

23. Franzblau A, Lilis R. Acute arsenic intoxicationfrom environmental arsenic exposure. Arch EnvironHealth. 1989 Nov-Dec;44(6):385-90.

24. Hindmarsh JT. Caveats in hair analysis in chronicarsenic poisoning. Clin Biochem. 2002 Feb;35(1):1-11.Review.

25. Lagerkvist BJ, Zetterlund B. Assessment of expo-sure to arsenic among smelter workers: a five year fol-low-up. Am J Ind Med. 1994 Apr;25(4):477-88.

26. Hindmarsh JT, MeLetchie OR, Hefferman LPM,Hayne OA, Ellenberger HA, McCurdy RF, Thiebaux HJ.Electromyographic abnormalities in chronic environ-mental arsenicalism. J Anal Toxicol.1977;1:270-6.

27. Murphy MJ, Lyon LW, Taylor JW. Subacute ar-senic neuropathy; clinical and electrophysiological ob-servations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1981 Oct;44(10):896-900.

28. Oh, SJ. Electrophysiological profile in arsenicneuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991 Dec;54(12)1103-5.

29.FordMD.Arsenic.In:GoldfrankL,editor.Goldfrank’sToxicologicEmergencies.7thed.NewYork:McGraw-Hill;2002. p. 1183-1200.

30. Saha KC. Diagnosis of arsenicosis. J Environ SciHealth A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng. 2003 Jan;A38(1):255-72. Review.

31. Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA).Perham Arsenic Site Remedy. St. Paul (MN): MinnesotaPollution Control Agency; 1996.

32. Dotson RM. Clinical neurophysiology laboratorytests to assess the nociceptive system in humans. J ClinNeurophysiol. 1997 Jan;14(1):32-45. Review.

33. Katims JJ. Electrodiagnostic functional sensoryevaluation of the patient with pain: A review of theneuroselective current perception threshold (CPT) andpain tolerance threshold (PTT). Pain Digest. 1998;8(5):219-230.

34. Ro LS, Chen ST, Tang LM, Hsu WC, Chang HS,Huang CC. Current perception threshold testing in Fabry’sdisease. Muscle Nerve. 1999 Nov;22(11):1531-7.

35. Katims JJ, Long DM, Ng LK. Transcutaneousnervestimulation (TNS). Frequencyandwaveform spec-ificity in humans. Appl Neurophysiol. 1986;49(1-2):86-91.

36. Katims JJ, Naviasky EH, Rendell MS, Ng LK,BleeckerML.Constant current sinewave transcutaneousnerve stimulation for the evaluation of peripheral neu-ropathy.ArchPhysMedRehabil.1987Apr;68(4):210-3.

Reviews, Case Histories 53

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UN

AM

Ciu

dad

Uni

vers

itari

a] a

t 13:

30 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2014

37. Lengyel C, Torok T, Varkonyi T, Kempler P,Rudas L. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart rate variabilityin insulin-dependent diabetics with polyneuropathy. Lan-cet. 1998 May 9;351(9113);1436-7.

38. Cheng WY, Jiang YD, Chuang LM, Huang CN,Heng LT, Wu HP, Tai TY, Lin BJ. Quantitative sensorytesting and risk factors of diabetic sensory neuropathy. JNeurol. 1999 May;246(5):394-8.

39.BleeckerML,Lindgren KN,Tiburzi MJ,Ford DP.Curvilinear relationship between blood lead level and re-action time. J Occup Environ Med. 1997 May;39(5):426-31.

40.BleeckerML,Ford DP,Tiburzi MJ,Lindgren KN.The relationship between peripheral nerve function andmarkers of lead dose. Neurology. 1998 April;50(4),(4Suppl);A53.

41. Shields M, Beckmann SL, Cassidy-Brinn G. Im-provement in Perception of Transcutaneous Nerve Stim-ulation Following Detoxification in Firefighters Exposedto PCBs, PCDDs and PCDFs. Clinical Ecology 1989;6(2);47-50.

42. New P. Neuroselective current perception thresh-old quantitative sensory test: a reevaluation. Neurology.1997 Nov;49(5);1482.

43. Husin LS, Uttaman A, Hirsham HJ, Hussain IH,Jamil MR. The effect of pesticide on the activity of serumcholinesterase and current perception threshold on thepaddy farmers in Muda agricultural development area,MADA, Kedah, Malaysia. Med J Malaysia; 1999 Sep;54(3);320-4.

44. Palliyath S, Preyan S: The role of Current Percep-tion Threshold (CPT) in Evaluating Peripheral Neuropa-thy. Accepted for presentation at the XVIth World Congressof Neurology, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1997.

45. Berger JS, Brannagan TH, Latov N. Neuropathywith anti-myelin-associated glycoprotein antibodies;quantitative sensory testing and response to intravenousimmunoglobulin; 44th annual Meeting of the AmericanAssociation of Electrodiagnostic Medicine 71, 1997.

46. Katims JJ, Naviasky EH, Ng LK, Rendell M,Bleecker ML. New screening device for assessment ofperipheral neuropathy. J Occup Med. 1986 Dec;28(12);1219-21.

47. Katims JJ, Rouvelas P, Sadler BT, Weseley SA.Current perception threshold: Reproducibility and com-parison with nerve conduction in evaluation of carpaltunnel syndrome. ASAIO Trans. 1989 Jul-Sep;35(3):280-4.

48. Barkai L, Kempler P, Vamosi I, Lukacs K, MartonA, Keresztes K. Peripheral sensory nerve dysfunction inchildren and adolescents with type I diabetes mellitus.Diabet Med.1998 Mar;15(3):228-33.

49. Umezawa S, Kananori A, Yajima Y, Aoki C. Cur-rent perception threshold in evaluating diabetic neuropa-thy. Journal of the Japanese Diabetes Society. 1997;8(1):711-19.

50. Kurozawa Y, Nasu Y. Current perception thresh-olds in vibration-induced neuropathy. Arch Environ Health.2001 May-Jun;56(3):254-6.

51. SNCT/CPT testing® CPT/C Operating Manual.Neurotron, Inc. Baltimore (MD); 1999.

52. Katims JJ, Naviasky EH, Ng LK, Rendell M,Bleecker ML. New screening device for assessment ofperipheral neuropathy. J Occup Med. 1986 Dec; 28(12);1219-21.

53. Takekuma K, Ando F, Niino N, Shimokata H. Ageand gender differences in skin sensory threshold assessedby current perception in community-dwelling Japanese.J Epidemiol. 2000 Apr;10(1 Suppl):S33-S38.

54. Wax PM, Thornton CA. Recovery from severe ar-senic-induced peripheral neuropathy with 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulphonic acid. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2000;38(7):777-80.

55. Kurttio P, Komulainen H, Hakala E, Kahelin H,Pekkanen J. Urinary excretion of arsenic species after ex-posure to arsenic present in drinking water. Arch EnvironContam Toxicol. 1998 Apr;34(3):297-305.

56. Srivastava AK, Hasan SK, Srivastava RC.Arsenicism in India: dermal lesions and hair levels. ArchEnviorn Health. 2001 Nov-Dec;56(6):562.

57. Takagi Y, Matsuda S, Imai S, Ohmori Y, MasudaT, Vinson JA, Mehra MC, Puri BK, Kaniewski A. TraceElements in human hair: an international comparison.BullEnviron ContamToxicol 1986Jun;36(6):793-800.

58. Seidel S, Kreutzer R, Smith D, McNeel S, GillissD. Assessment of commercial laboratories performinghairmineral analysis. JAMA.2001Jan3;285(1):67-72.

59. Shamberger RJ. Validity of hair mineral testing.Biol Trace Elem Res. 2002 Summer;87(1-3):1-28.

RECEIVED: 10/11/2004REVISED: 04/04/2005

ACCEPTED: 09/20/2005

54 JOURNAL OF AGROMEDICINE

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

UN

AM

Ciu

dad

Uni

vers

itari

a] a

t 13:

30 2

1 D

ecem

ber

2014