Nurses’ conceptions of facilitative strategies of weaning patients from mechanical ventilation—A...

-

Upload

jeanette-eckerblad -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

3

Transcript of Nurses’ conceptions of facilitative strategies of weaning patients from mechanical ventilation—A...

Intensive and Critical Care Nursing (2009) 25, 225—232

avai lab le at www.sc iencedi rec t .com

journa l homepage: www.e lsev ier .com/ iccn

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Nurses’ conceptions of facilitative strategies ofweaning patients from mechanical ventilation—–Aphenomenographic study

Jeanette Eckerblada, Heléne Erikssona, Anita Kärnera,Ulla Edéll-Gustafssonb,∗

a Department of Social and Welfare Studies, Faculty of Health Sciences, Linköping University, Swedenb Department of Medical and Health Sciences, Nursing Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences,Linköping University, SE-581 85 Linköping , Sweden

Accepted 23 June 2009

KEYWORDSCommunication;Intensive care;Mechanical ventilatorweaning;Nursing

SummaryBackground: Mechanical ventilator withdrawal can amount up to 40% of total ventilator time.Being on a mechanical ventilator is associated with risk of anxiety, post-traumatic stress syn-drome, nosocomial pneumonia and premature mortality.Purpose: The purpose of the present study was to describe different conceptions of nurses’facilitating decision-making strategies regarding weaning patients from mechanical ventilationscared for in intensive care unit (ICU).Method: Semi-structured interviews were analysed within the phenomenographic framework.Twenty ICU nurses were interviewed.Findings: The findings revealed three main categories of nurses’ facilitating decision-makingstrategies: ‘‘The intuitive and interpretative strategy’’ featured nurses’ pre-understandings.‘‘The instrumental strategy’’ involved analysis and assessment of technological and physiolog-ical parameters. ‘‘The cooperative strategy’’ was characterised by interpersonal relationshipsin the work situation. Absence of a common strategy and lack of understanding of others’ strate-

gies were a source of frustration. The main goals were to end mechanical ventilator support,create a sense of security, and avoid further complications.Conclusion: Although these findings need to be confirmed by further studies we suggest thatnurses’ variable use of individual strategies more likely complicate an efficient and safe weaningprocess of the patients from me© 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights re∗ Corresponding author. Tel.: +46 13 227778.E-mail address: [email protected]

(U. Edéll-Gustafsson).

I

Dti

0964-3397/$ — see front matter © 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2009.06.008

chanical ventilation.served.

ntroduction

espite dramatic developments in mechanical ventilatorechnology and pharmacological treatment, the wean-ng process is still described as a stressful, frightening,

2

hCamv2i(omsfi(ptth2

o2taiWtifncfabLcb2

fersinoBOspbFiiiahfitowi

M

InanasdwiNwemyytsatdtp

I

T(tgsacqetitSdtvTtavopfgi

D

I

26

opeless, and frustrating period for patients (Burns andhochesy, 1995; Cook et al., 2001; Macintyre, 2007; Schound Egerod, 2008). The critical care nurse’s decision-aking strategy related to the process of mechanical

entilator weaning is probably of importance (Aitken,003; Taylor, 2006), as the risk of nosocomial pneumoniancreases 8-fold and the risk of premature mortality 12-foldMacintyre, 2001). Post-traumatic stress disorder symptomsccur in nearly 20% of critically ill patients who requireechanical ventilation (Girard et al., 2007). In addition,

tudies have shown that about 25% fail to recover suf-cient spontaneous respiration, despite improved healthBlackwood et al., 2004). Patients with severe weaningroblems may need a longer weaning period owing tohe duration and/or discontinuation of mechanical ven-ilator support, insufficient respiratory muscles, mentalealth and over-sedation (Macintyre, 2007; Girard et al.,008).

The next of kin are an important link for developmentf care in a nursing environment (Engström and Söderberg,007; Engström, 2008; Schou and Egerod, 2008). They givehe nurse an opportunity to get to know the patient as

person in his/her social context, which in turn resultsn a meaningful dimension of nursing (Kociszewski, 2004;illiams, 2005; Davies, 2007). Unsatisfactory communica-

ion is more likely to lead to increased stress and anxietyn the patient (Alasad and Ahmad, 2005). Davies (2007)ound that patients’ experience of a panic attack didot hinder the ventilator weaning process when nurses’ommunication with patients or the family was success-ul. By gaining knowledge about patients’ physiologicalnd psychological resources, nurses can create a balanceetween rest and work in the weaning process (Jenny andogan, 1994). To achieve progress in the weaning pro-ess, nurses working in intensive care units (ICU) muste aware of patients’ underlying emotional state (Davies,007).

Numerous studies have evaluated procedures for weaningrom mechanical ventilation (Blackwood et al., 2004; Girardt al., 2008; Crocker and Kinnear, 2008). These studies haveevealed contradictory results regarding the importance ofuch protocols. Use of a protocol may be unsatisfactoryf it creates barriers for example, disagreement betweenurses and physicians owing to their different conceptionsf the weaning process (Mårtensson and Fridlund, 2002;lackwood et al., 2004; Hansen and Severinsson, 2007).n the other hand, in order to achieve an efficient andafe weaning process, nurses have been conducting suchrocedures with the support of protocols. Protocols haveeen shown to help nurses act more freely (Mårtensson andridlund, 2002; Hansen and Severinsson, 2007). However, anmportant factor for promoting an efficient ventilator wean-ng process is probably more related to the staff availablen the ICU and management procedures rather than to actu-lly having a protocol (Brochard, 2008). No previous studiesave explored nurses’ conceptions and understandings byocusing on their decision-making strategies regarding wean-

ng ICU patients from mechanical ventilation. The aim ofhe present study was to describe different conceptionsf nurses’ facilitating decision-making strategies regardingeaning ICU patients from mechanical ventilation cared forn ICU.

auada

J. Eckerblad et al.

ethods

n this qualitative study, dialogical interviews and a phe-omenographic approach, based on Marton and Booth (1997)nd Sjöström and Dahlgren (2002), were chosen. Out of 74urses, 10 nurses at a general hospital ICU and 10 nurses atuniversity hospital ICU in the south-east of Sweden were

elected using convenience sampling. To grasp a variation ofifferent kinds of conceptions among nurses, two hospitalsith a similar patient basis were chosen. Written and verbal

nformation was given and informed consent was obtained.urses who had at least one year of clinical experience ofeaning patients from a mechanic ventilator in the ICU wereligible for inclusion. Nurses included in this study were twoen and 18 women, who had worked as an RN between three

rs and 37 yrs (Md 20.5 yrs) and in the ICU between 1.5rs and 33 yrs (Md 14 yrs). Altogether, 423 patients, with aotal of 45,717 h (Swedish association of Anastasia and Inten-ive care. SFAI, 2005) of respiratory insufficiency of differentetiologies, were treated in a mechanical ventilator at thewo hospitals, during the year of data collection. The meanuration of mechanic ventilator support was 108 h. None ofhe ICU wards included here had a standardised strategy orrotocol for weaning patients from a mechanical ventilator.

nterview

he interviews were conducted by two of the first authorsJ.E., H.E.) in an adjacent room at the two ICUs, respec-ively, at the end of the nurses’ working shift. An interviewuide (Sjöström and Dahlgren, 2002), developed for thistudy was used. The interviews began with a question suchs: ‘‘How many years have you been working as a criticalare registered nurse (CCRN)?’’ followed by supplementaryuestions about the phenomenon, such as: ‘‘Describe yourxperience as a nurse, of working with mechanical ventila-or weaning’’, ‘‘Describe your interaction with the patientn the weaning process’’, ‘‘Describe how you facilitatehe weaning process’’,‘‘What can obstruct the process?’’upplementary questions such as what, how and can youevelop this, were added in order to encourage the nurseso describe their experiences in more detail. The inter-iews varied in length between 15 and 45 min (Md 36 min).he interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verba-im after all interviews had been performed by the two firstuthors (J.E., H.E.). Before the main study began, an inter-iew guide was constructed by the authors and then testedn four CCRNs. In order to look at deeper dimensions of thehenomenon, the interview guide was reworked and twoollow-up questions were added. Thereafter the interviewuide was retested. The test interviews were not includedn the present study.

ata analysis

n order to describe the variation in the nurses’ experiences

nd knowledge of the phenomenon, the data was analysedsing a phenomenographic procedure according to Dahlgrennd Fallsberg (1991) seven steps, Familiarisation, Con-ensation, Comparison, Grouping, Articulating, Labellingnd Contrasting. During analysis, similar conceptions from

Facilitative strategies of weaning patients from mechanical ventilation 227

Table 1 The phenomenographic analysis seven steps according to Dahlgren and Fallsberg (1991).

(1) Familiarisation The interviews were transcribed verbatim. The what-aspect was identified as facilitatemechanical ventilator weaning and the how-aspect strategies nurses use.

(2) Condensation Prominent perceptions were selected with a focus on the how-aspect.(3) Comparison The essences of the selected statements were compared with each other. Similarities and

differences emerged. The external horizon appears in the form of four description categories.(4) Grouping The material was sorted after the main content. Revisions were made to delineate differences

between the description categories. This resulted in the description categories were reducedinto three.

(5) Articulating By highlighting the how-aspect in the various groups a deeper dimension started to emerge.An attempt was made to describe the essence of the answer who were similar.

(6) Labelling The description categories were named after the essence of the content and the quotationwas presented. Internal horizon in term of components made a clear variation within each

ere ncate

ttdits(fita(iPGc

T

Ttsmm

category. The components w(7) Contrasting Phenomena of every descript

different narratives were gathered and described by theauthors in an objective way (Dahlgren and Fallsberg, 1991)(Tables 1 and 2).

Ethical approval

The study followed the ethical guidelines given in the Dec-laration of Helsinki. The head of the two ICU units (Chefexecutive officer) approved of the study, and representa-tives of the trade union were informed. The nurses wereinformed that their participation was completely voluntaryand that they could terminate their participation at any timewithout any consequences. All the information and materialscollected in the study have been handled confidentially.

Pre-understanding

Three of the present authors are CCRNs (J.E, H.E, U. E.-G.)with solid clinical experience of working in an ICU and ofweaning patients from ventilators.

Credibility and validation of the study

The tape recordings of the interviews increased the credibil-ity of the transcription process. The data analysis followedDahlgren and Fallsberg’s seven steps. Two of the authors(J.E., H.E.) independently transcribed the interviews and

T

Tp

Table 2 Different conceptions of nurses’ facilitating decision-mventilation.

The intuitive and interpretative way of being The instrumen

Autonomy, accommodation, distraction Mechanical—tevaluation

• Instantaneous planning • Protocol-d• Intuitive acting • Medical k• Superior of the patient • Physical p• Physically and emotionally present • Emotiona

• Informati

amed along what was specific and symbolized the strategy.gory were valued and discussed with the supervisor.

hen analysed the transcriptions. Thereafter, they workedogether with comparisons of the material searching forifferences and similarities. Conceptions were dealt withn their own context. The conceptions were then decon-extualised, and thereafter a systematic comparison ofimilarities and differences could be made. A co-assessorA.K.) read the preliminary categories and questioned thendings of the first authors. Carefully describing a quali-ative method from design and data collection to analysisnd interpretation strengthens the study’s trustworthinessSjöström and Dahlgren, 2002). The descriptive categoriesn the findings are illustrated by quotations (Mays andope, 2000). Finally, phenomenographic researchers (U.E.-., A.K.) read the analyses to further specify the descriptiveategories.

he findings

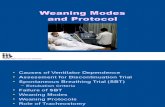

hree descriptive categories: the intuitive and interpreta-ive strategy, the instrumental strategy and the cooperativetrategy of the phenomenon nurses’ facilitating decision-aking strategies regarding weaning ICU patients fromechanical ventilation were found.

he intuitive and interpretative strategy

his descriptive category was built on three distinctive com-onents: autonomy, accommodation and distraction.

aking strategies for weaning ICU patients from mechanical

tal way of being The cooperative way of being

echnical, physiological Teamwork, relationships

riven planning • Nursing plannowledge • Internal relationsresence • Inter personal approachlly distanced • Dialogueon

2

A

Startcpvsacshtat

A

BepaopawppitwnplNcocwpthtc

D

NpciufilaNfipdt

T

Tta

M

ArtatdvptcpdwppItbaatt

28

utonomy

ome of the nurses expressed that autonomy is gainedhrough nursing experience, while others felt it to be

personal quality. Nurses considered physicians’ ordersedundant and sometimes directly obstructive to ventila-or weaning. Information regarding the patient was verballyommunicated between staff members. Ventilator weaningrotocols and nursing plans were a direct threat to efficiententilator weaning progression. The nurses implied that atrategy that worked well in the morning did not work atll in the afternoon as the patients’ physical condition oftenhanged during the day. Nurses had an outstanding under-tanding of the patient because they worked so close toim/her. By acting autonomously, nurses facilitated ventila-or weaning. Nurses read and appraised their patients’ needsnd capacity and simultaneously adjusted their strategieshereafter.

‘‘It feels like nurses who do a bit more on their ownauthority or whatever you call it, who don’t follow thephysician’s order word-for-word, their patients makefaster progress. You base the weaning process a bit moreon your feelings and watch the patient instead of justfollowing a schedule’’ (No. 2)

ccommodation

y adjusting their strategies to each patient at everyncounter, nurses could facilitate the ventilator weaningrocedure. Achieving successful weaning was a challenge,nd it felt like a personal defeat when complicationsccurred. Patience was of great importance in achievingrogress in the weaning process, and it was described asvery sensitive part of ICU nursing. Ventilator weaning

as facilitated through intuitive appraisal of the patient’shysiological and psychological parameters. Physiologicalarameters could sometimes be of assistance but werenferior when it came to adjusting the strategy. Throughhe clinical assessment based on clinical experiences ofeaning like facial expressions and bodily movements, theurses decided when the patients needed the ventilator sup-ort back. Nurses described that patients who had spent aong time on ventilator support often had low self-esteem.urses described that the patients expressed by non-verbalommunication their lack of capacity to start breathingn their own. By working with patient empowerment andhoosing an encouraging strategy, nurses could facilitateeaning even in such patients. In some cases the nursesrevented the patients’ desire to wean in purpose to facili-ate the weaning process. Such an accommodating strategyelped patients who desperately wanted to get off ven-ilator support but who did not know their own limited

apacity.‘‘Some patients can push themselves over the edge if I letthem decide how long they can breathe spontaneously,because they want to get rid of the mechanical ventilatoras quickly as possible. And you know, that only leads to abacklash.’’ (No. 11)

iWtamad

J. Eckerblad et al.

istraction

urses described distraction as a strategy to minimiseatients’ stress and anxiety in the ventilator weaning pro-ess. ICU nurses appraised if and when the patient should benformed of the weaning procedure. By analysing and eval-ating decline in patients’ body strength, observing theiracial expressions and by communicating, nurses got anmpression of patients’ current physiological and psycho-ogical state. Taking that into consideration, nurses coulddjust the level of distraction the individual patient needed.urses also reported that information may be a prerequisiteor successful ventilator weaning. The distraction used couldnvolve discussing a family picture, music, television or theatient receiving a visit from a family member. During suchistractions, nurses could reduce ventilator support withouthe patient’s knowledge.

‘‘For some patients, the situation gets very stressful ifyou tell them that you’re going to reduce the pressuresupport, that’s why you reduce the pressure first and thentell them. Of course it’s different from patient to patient,but you notice those things.’’ (No. 5)

he instrumental strategy

his descriptive category consisted of two sub-categories:he mechanical—technical strategy and the physiological ofppraisal strategy.

echanical—technical strategy

ccording to nurses using this strategy, education and expe-ience of the advanced technology used in the ICU leadso greater competence. Such knowledge enabled nurses tossess and evaluate several physiological parameters, andhis information is vital to facilitating the weaning proce-ure. The nurses stated that experience of the mechanicalentilator weaning technique was a prerequisite for aositive outcome. Feeling insecure about various medicalechniques is a great disadvantage in nursing care. In theseritical situations, it is the nurse’s competence that gives theatient security. The patient’s weaning outcome is depen-ent on physiological and psychological parameters. Theeaning procedure began with the nurses reducing theressure support and reducing the positive end expiratoryressure, as required by the patient’s physiological needs.n the end, it was quite easy to remove the ventilator and forhe patient to start breathing spontaneously. The transitionetween controlled ventilator mode, pressure support modend spontaneous breathing did not need to be as difficults it once was, before the advanced mechanical ventila-or was introduced. The nurses reported that the new, moreechnically developed mechanical ventilator that gives earlyndications of spontaneous breathing facilitates weaning.ith such modern equipment, the patient was unaware of

he need for ventilator support, which thus could be gradu-lly removed. The nurses felt that weaning a patient from aechanical ventilator was not a greater problem today than

ny other problem on the ICU, all thanks to the technologicalevelopments.

vent

T

Ieataprmw

tIapibptwr

R

TwCaaopwa

stRcp

Facilitative strategies of weaning patients from mechanical

‘‘It was different before, when you only had volume con-trolled breathing on the mechanical ventilator and theywere weaning for ten minutes per hour, it was very hardwork for the patient. Nowadays it’s not so much work,they can be weaned now and then, and you can bal-ance the support all the time, which makes things mucheasier’’. (No. 17)

Tracheotomy is used more frequently today, and there-fore patients no longer have to be sedated to the sameextent. A patient who is awake can follow instructions and isable to receive information. The nurses inform the patientof the plans and that everything is working.

‘‘I facilitate weaning by setting a time for the patient,so he understands it concerns a certain amount of time’’(No. 14)

Using a fenestrated inner cannula, which allows patientsto speak, was a strategy that increased patients’ will andmotivation in the weaning process. When they could heartheir own voice, patients regarded it as having part of theirpersonality back. It was a sign of recovery and increasedtheir motivation.

‘‘Many patients feel that they are on their way to recov-ery when they can talk and hear their own voice again -Yes finally’’. (No. 14)

Physiological of appraisal strategy

The nurses stated that ventilator weaning based on aphysician’s order started when the medical condition hadimproved and the need for support had declined. It wasimportant that the patient did not have a fever, was awakeand that infection parameters had declined.

Expected arterial acid—base indicators in relation tothe physiological parameters were modified based on thepatient’s basic condition and past illnesses. The strategy wasappraised using respiratory rate, PO2 and PCO2. The cur-rent strategy could be re-appraised if the arterial acid—basebalances deteriorate, and thereby weaning could be facili-tated.

‘‘If the patient has an arterial catheter, you can anal-yse the blood and you can see if the carbon dioxide isprogressing, then you can look at the saturation and therespiratory rate and how the patient looks. Then maybeyou have to interrupt the weaning for a while, but if thevalue is good you try for a little while longer’’. (No. 9)

The nurses described the lack of an evaluation tool as abarrier. Such a tool would allow them to confirm that theweaning process was proceeding as expected.

‘‘There is nothing established telling you do this and thenthat, so you just don’t know if you’re doing it right’’. (No.

3)The cooperative strategy

In this category, two sub-categories were found: teamworkand relationships.

ttccdrm

ilation 229

eamwork

n order to facilitate weaning from the ventilator, good coop-ration between several actors was required. The patientnd next of kin are part of the team. The nurses reportedhat a strong emphasis on information, communication andlong-term nursing plan are a prerequisite. The team mustursue the same goals and have common strategies. Aelapse occurs when the nursing plan must be revised, whichoves the process one or more steps backward. Relapsesere perceived as a source of frustration in the teamwork.

‘‘It’s important that the staff and patient work towardsthe same goal. It’s not necessary for many people to beinvolved, that can be messy and cause insecurity in thepatient.’’ (No. 7)

Cooperation problems between co-workers within theeam were described as a barrier to the weaning process.f the staffs showed uncertainty, this may create anxietynd insecurity in the patient, which obstructed the weaningrocess. A fully booked ICU was another barrier to follow-ng the nursing plan. Established goals may then have toe reviewed, and there was a risk for early extubation andremature transfer from the ICU ward. The nurses reportedhat early extubation and premature transfer from the ICUard can cause a patient’s condition to deteriorate, perhaps

esulting in a return to the ICU.

elationships

he continuity of nursing care in mechanical ventilatoreaning was a prerequisite for creating a good relationship.onfidence was something nurses respected and cherished,nd it took time to build. Weaning was facilitated whennurse could care for the same patient over a number

f weaning sessions, during which a relationship with theatient and next of kin could be established. Next of kinho were involved gave the patient a feeling of securitynd encouragement in the weaning process.

‘‘I give the patient information, make sure they aren’tsuffering from pain or feel uncomfortable in bed. ThenI explain what I’m doing and it’s important to tell themthat they can get the ventilator support back immediatelywhen they want it. Some patients are worried about theirown ability to breath, it’s vital then to tell them that - youjust do the best you can, and you’ll get the mechanicalventilator when you want.’’ (No. 10)

Strategies for the next day were planned in relation toleep, food, and mobility. On the contrary, other nurses sawhe downsides of nursing the same patient for a long period.ecurrent relapses that involved restarting the weaning pro-ess and slow recovery could have lead to frustration andowerlessness for the nurses in charge. Communication withhe patient and next of kin was of the greatest importance tohese nurses. A fenestrated inner cannula, a non-electronic

ommunication board and different signs could facilitateommunication with these patients. All information was alsoistributed to the other members of the team. The nurseseported that it was of great importance that patients wereotivated and had a desire to end ventilator support. Nurses

2

up

efTwt

C

Trwrwr

iSsptcn

npfttstwbs

D

TdiatianooooDdttth

omc2

T

TciotatdmnaatgatLtga(pepan(dpetvaspit

T

CgppppWbi

30

sing this strategy facilitated weaning by acknowledging theatient.

The nurses discussed their frustration over the gaps thatxisted regarding guidelines and goals. Weaning would beacilitated if guidelines and procedures were established.his was a greater problem during holidays and weekendshen additional physicians were involved and there was lit-

le continuity among the staff.

‘‘There is a problem with the organisation, no routinesfor weaning exist, everyone just follows his or her ownmind.’’ (No. 18)

ontrast

he present study revealed a wide variety of conceptionsegarding ICU nurses facilitating decision-making strategieshen weaning patients from mechanical ventilators. All

espondents indicated that the main objective of weaningas to free patients from ventilator support and avoiding

elapses.Creating security for the patient was identified as an

mportant component of successful ventilator weaning.ecurity was created in the intuitive and interpretativetrategy by the nurse being physically and emotionallyresent. In the relation to the physicians and the patientshe nurses considered themselves to be superior regardinglinical experiences in terms of understanding the patients’eeds and capacity.

In the instrumental strategy, security was provided byurses who were highly skilled at evaluating physiologicalarameters and managing medical techniques. The nurses’ocus was based on the physicians’ prescriptions and objec-ive medical technological facts about the patients ratherhan the patients’ subjective needs. In the cooperativetrategy, security was created through interpersonal rela-ionships. The ability to cooperate within the care team,ith the patient and next of kin was a prerequisite foruilding security in the weaning process. Nurses using thistrategy developed an interpersonal approach.

iscussion

he present study shows three different conceptions ofecision-making strategies nurses used to facilitate mechan-cal ventilator weaning. The strategies were the intuitivend interpretative approach, the instrumental approach andhe cooperative approach. Whether the nurses used predom-nantly one or a mixture of these strategies remains unclearnd may be answered in another study. These strategies haveot been previously reported in literature. The objectivef all nurses included in the study was to get the patientff the ventilator as soon as possible, to create a feelingf security and to prevent relapse, as described in previ-us studies (Macintyre, 2001, 2007; Girard et al., 2008).epending on their choice of strategy, the nurses described

ifferent conceptions of factors that obstructed and facili-ated the weaning process. In an attempt to draw attentiono the different decision-making strategies prevailing onhe ward, cooperation between nurses could be facilitated,opefully creating a balance in the weaning process. Previ-oirbt

J. Eckerblad et al.

us studies have described differences of opinion regardingechanical ventilator weaning between nurses and physi-

ians or between nurses and other professionals (Taylor,006; Hansen and Severinsson, 2007; Brochard, 2008).

he intuitive and interpretative strategy

he nurses read and intuitively interpreted patients’apacity instantaneously. Strategies were adapted to thendividual patient’s capacity, and the appraisal was basedn the nurses’ pre-understandings. The findings showed thathe physiological parameters and the technology were useds a support in their choice, but were not of crucial impor-ance. There was a risk of basing the decision on quantitativeata only (Wikström and Larsson, 2004). The nurses felt thatechanical ventilator weaning was a very sensitive part of

ursing, a finding also revealed in previous studies (Burnsnd Chochesy, 1995; Burns, 2003; Macintyre, 2007; Schound Egerod, 2008;). However, by knowing the patients well,he nurses were able to accommodate their nursing strate-ies. Reading and interpreting the patient’s body languagend facial expressions enable nurses to create a balance forhe patient, thereby preventing a relapse, which Jenny andogan (1994) also found. However, lack of time is a barrier tohese nurses. Being close to the patient is a precondition forood nursing, and that is how these nurses created securitynd were able to make the right decision. Jenny and Logan1994) revealed similar findings in their qualitative study;atients expressed the importance of nurses’ physical pres-nce and emotional support. Weaning protocols and nursinglans were considered as barriers to creating a balance andccommodating nursing care to patients’ needs instanta-eously. The findings correspond with the Blackwood et al.2004) study. The consequences might be that the nursesisregard the patient’s clinical changes. The nurses in theresent study who used an intuitive and interpretative strat-gy highly valued their clinical experience in contradictiono nurses who used the instrumentally strategy and highlyalued quantitative physiological parameters. The nurseslso considered physicians’ prescriptions superfluous andometimes incorrect: Nurses know the patient best. In theresent study, nurses reported that they only gave patientsnformation if they could manage it, and sometimes distrac-ion was necessary instead.

he instrumental strategy

ontrary to the intuitive and interpretative strategy, nursesreatly appreciated the technology and the physiologicalarameters. The fact that the nurses relied more on thehysicians’ orders and objective information about theatients rather than the patients’ subjective needs mightrove an emotional distance. Findings from Wiman andikblad (2003) study in an emergency ward showed similar

ehaviour and attitudes among nurses, who were labellednstrumental. Education in medical techniques, knowledge

f physiological parameters and experience of the wean-ng process are necessary to facilitate weaning and avoidelapse. Appraisal and choice of strategy were made on theasis of quantitative data obtained via technology. Throughhe knowledge and security of medical techniques, nurses

vent

uwt

A

TDd

R

A

A

B

B

B

B

C

C

D

D

E

E

EG

G

H

Facilitative strategies of weaning patients from mechanical

can create a safe nursing environment for the patient. Lackof competence in using these techniques makes the nursingunsafe. One barrier was a lack of quantitative evaluationprotocols and variations in the patient’s medical status.Hansen and Severinsson (2007) showed improvements innurses’ sense of security when they had a weaning pro-tocol to rely on. The nurses were more goal-oriented andwere able to act independently. Using a weaning guidelinereduced time for weaning from the mechanical ventilator(Macintyre, 2007). Concrete information was given to thepatient. Contrary to nurses in the other categories, those inthe cooperative category made all decisions and establishedgoals in dialogue with the patient.

The cooperative strategy

Creating a good nursing environment and good collaborationwithin the work team was essential. Similar to nurses in theintuitive and interpretative strategy, these nurses had to benear their patients to create a feeling of security.

It was important to create a relationship with thepatient and also his/her next of kin, which Travelbee (1971)described as the nursing internal dimension. In creatingsecurity, the nurse transforms his/her role and encountersthe patient and the next of kin human to human. Eriksson(2000) stated that a relationship between the patient andthe nurse is a precondition for excellent nursing. The fac-tors of continuity, confidence, participation and dialogueemerge from the present findings as fundamental in creat-ing a good relationship. Next of kin are of great importance,and through them the nursing staff can get to know thepatient as a person in a social context. This enables a mean-ingful dimension in nursing (Kociszewski, 2004; Williams,2005; Davies, 2007). Engström and Söderberg (2007) foundthat patients too, experienced the presence of their next ofkin as essential to managing their difficult disease. Patientsalso saw their next of kin as the people they could com-municate with and the people who best understood them(a.a). The nurses considered that one of the prerequisitesof recovery is motivation, and communication is one way toincrease motivation. A nursing plan based on teamwork wasessential to achieve excellent nursing. These nurses felt thatlack of engaged physicians and disharmony in the teamworkwere barriers. In accordance with this notion, Hansen andSeverinsson (2007) findings showed that nurses had to delaydecisions due to absent physicians.

Clinical implications

By making visible these different conceptions of nurses’facilitating decision-making strategies regarding mechani-cal ventilator weaning, we may be able to initiate a debateand reflection on the matter, hopefully leading to bettercooperation between professionals on ICU wards. Throughknowledge and understanding of the various strategies,nurses can further develop their nursing competence.

Conclusions

Although these findings need to be confirmed by furtherstudies we suggest that nurses’ variable use of individ-

J

K

ilation 231

al strategies more likely complicate an efficient and safeeaning process of the patients from mechanical ventila-

ion.

cknowledgements

his work was supported by grants from the Research andevelopment Unit at Vrinnevi Hospital in Norrkoping, Swe-en, no. FoU 5/04.

eferences

lasad J, Ahmad M. Communication with critically ill patients. Jour-nal of Advanced Nursing 2005;50:356—62.

itken LM. Critical care nurses’ use of decision-making strategies.Journal of Clinical Nursing 2003;12:476—83.

lackwood B, Wilsson-Barnett J, Trinder J. Protocolized weaningfrom mechanical ventilation: ICU physicians’ views. Issues andinnovations in nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing2004;48:26—34.

rochard L. Sedation in the intensive-care unit: god and bad? Lancet2008;371(9607):95—7.

urns SM, Chochesy JM. Weaning from long-term mechanical venti-lation. American Journal of Critical Care 1995;4:4—22.

urns SM. Implementation of an institutional program to improveclinical an financial outcomes of mechanically ventilatedpatients: one-year outcomes and lessens learned. Critical CareMedicine 2003;31:2752—63.

ook D, Meade M, Perry A. Qualitative studies on the patient’sexperience of weaning from mechanical ventilation. Chest2001;120:469—73.

rocker C, Kinnear W. Weaning from ventilation: does a carebundle approach work? Intensive and Critical Care Nursing2008;24:180—6.

ahlgren L, Fallsberg O. Phenomenography as a qualitativeapproach in social pharmacy research. Journal of Social andAdministrative Pharmacy 1991;8:150—6.

avies D. Reflection on practice. An intubated patient sufferingpanic attack. Nursing in Critical Care 2007;12:198—201.

ngström Å. A wish to be near. Experiences of close relatives withinintensive care from perspective of close relatives, formerly criti-cally ill people and critical care nurses. Sweden: Luleå Universityof Technology, Department of Health Science, Division of Nurs-ing; 2008, 05.

ngström Å, Söderberg S. Receiving power through confirmation.The meaning of close relatives for people who have been criti-cally ill. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2007;59:569—76.

riksson K. Vårdprocessen. 4th ed. Stockholm: Liber; 2000.irard T, Shintani A, Jackson J, Gordon S, Pun B, Hendersson

M, et al. Risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder symp-toms following critical illness requiring mechanical ventilation:a prospective cohort study. Critical care 2007;11:1—8.

irard T, Kress J, Fuchs B, Thomasson J, Scheickert W, TaicmanD, et al. Efficiency and safety of a paired sedation and ven-tilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patientsin intensive care (awakening and breathing controlled trial): arandomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;371:126—34.

ansen BS, Severinsson E. Intensive care nurses’ perceptions ofprotocol-directed weaning—–a qualitative study. Intensive andCritical Care Nursing 2007;23:196—205.

enny J, Logan J. Promoting ventilator independence: a groundedtheory perspective. Dimension of Critical Care Nursing1994;13:29—37.

ociszewski C. Spiritual care: a phenomenological study of criticalcare nurses’. Heart and Lung 2004;33:401—11.

2

M

M

M

M

M

S

S

S

T

T

W

W

32

acintyre N. Evidence—–based guidelines for weaning and discon-tinuing ventilatory support. Chest 2001;120:375—95.

acintyre N. Discontinuing mechanical ventilatory support. Chest2007;132:1049—56.

arton F, Booth S. Learning and awareness. Mahwah, NJ: LawrenceErlbaum Associates, Publishers; 1997.

ays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care—–assessingquality in qualitative research. British Medical Journal2000;320:50—2.

årtensson I-E, Fridlund B. Factors influencing the patient duringweaning from mechanical ventilation: a national survey. Inten-sive and Critical Care Nursing 2002;18:219—29.

chou L, Egerod I. A qualitative study into the lived experience

of post-CABG patients during mechanical ventilator weaning.Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 2008;24:171—9.wedish association of Anastasia and Intensive care. SFAI.http://www.sfai.se/dokument/verksamhetsberaettelse/verksamhetsberaettelser; 2005 [December 29].

W

J. Eckerblad et al.

jöström B, Dahlgren L-O. Applying phenomenography in nursingresearch. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2002;40:339—45.

aylor F. A comparative study examining the decision-making pro-cesses of medical and nursing staff in weaning patients frommechanical ventilation. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing2006;22:253—63.

ravelbee J. Interpersonal aspects of nursing. 2nd ed. Philadelphia:F.A. Davis Company; 1971.

ikström AC, Larsson SU. Technology—–an actor in ICU: a studyin workplace research tradition. Journal of Clinical Nursing2004;13:555—61.

illiams C. The identification of family members’ contribution topatients’ care in the intensive care unit: a naturalistic inquiry.

British Association of Critical Care Nurses. Nursing in CriticalCare 2005;10:6—14.iman E, Wikblad K. Caring and uncaring encounters in nurs-ing in an emergency department. Journal of Clinical Nursing2003;13:422—9.