North Korea on Capitol Hill

-

Upload

federico-you -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

description

Transcript of North Korea on Capitol Hill

Lynne Rienner Publishers is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Asian Perspective.

http://www.jstor.org

NORTH KOREA ON CAPITOL HILL Author(s): Karin Lee and Adam Miles Source: Asian Perspective, Vol. 28, No. 4, Special Issue on Transforming U.S.-Korean Relations (

2004), pp. 185-207Published by: Lynne Rienner PublishersStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/42704483Accessed: 14-05-2015 11:20 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ASIAN PERSPECTIVE, Vol. 28, No. 4, 2004, pp. 185-207.

NORTH KOREA ON CAPITOL HILL

Karin Lee and Adam Miles

North Korea provides a case study of the inherent ten- sions between the executive and legislative branches in the determination of U.S. foreign policy. Congress put various obstacles in the path of the Clinton administration's engage- ment strategy toward North Korea , anticipating some of the policy changes undertaken by the George W. Bush adminis- tration in its fìrst term. Recent congressional efforts to inject the issue of human rights into the debate on U.S.-North Kore- an relations have the potential to backfire unless carefully implemented. Meanwhile , Congress has missed several opportunities to make a positive contribution to the ongoing nuclear crisis. This article will also look at the interest groups that have shaped congressional forays on North Korea and touch briefly on South Korean attempts to influence U.S. leg- islation on North Korea. Finally, it will discuss possible future struggles between the administration and Congress over North Korea and make recommendations for future policy initiatives.

Key words: U.S.-North Korean relations, U.S. foreign policy, Congress, North Korean Human Rights Act of 2004

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

186 Karin Lee and Adam Miles

Congress as a Shaper of U.S. Policy

Over the summer of 1994, Congress caught wind of the details of the security negotiations between the United States and North Korea, and many members didn't like it. They criti- cized the negotiations process. They called President Bill Clinton an appeaser. Some of the most vocal critics, such as Republican Senators John McCain (Arizona), Frank Murkowski (Alaska), and Robert J. Dole (Kansas), made legislative parries to express their distrust of the process. Most of these attempts failed. But in August 1994, several months before North Korea and the United States signed the Agreed Framework, the legislative opponents were victorious. An amendment that unanimously passed the Senate conditioned U.S. aid to North Korea on presidential certi- fication that North Korea had halted its nuclear weapons pro- gram and did not have any nuclear weapons.1

Although the naysayers scored a small legislative victory with the passage of the amendment, by the end of Clinton's sec- ond term in 2000, the U.S. government had provided a total of $671.2 million of humanitarian and energy assistance to North Korea.2 Although Congress was not able to stop Clinton's policy in its tracks, it did manage to erect substantial roadblocks. By routinely hammering the administration, Congress successfully prevented full implementation of the Agreed Framework. The resulting delays and hesitations helped to erode trust between the United States and North Korea.

By the time President George W. Bush took office, Congress had shifted its targets away from the narrow provisions of the Agreed Framework and toward a range of new issues such as North Korea's role in terrorism, drug trafficking, and counter- feiting, as well as humanitarian concerns such as food aid,

1. Dole Amendment No. 2273 to the bill H.R. 4426, as reported in the Con- gressional Record, July 14, 1994, p. S9044.

2. Mark Manyin and Ryun Jun, "U.S. Assistance to North Korea" (Wash- ington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service Report RL 31785, 2003), p. 1. The food aid figure is the amount pledged for that year, although partial shipments may not have taken place until the following year. The figure for KEDO (the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organiza- tion) is the amount appropriated by Congress specifically for KEDO; some additional funds for KEDO came from other sources.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

North Korea on Capitol Hill 187

human rights, and refugees.3 Congress, now with some in the administration on its side, again attempted to erect barriers against U.S. aid to North Korea, this time with human rights rather than nuclear proliferation as the criterion.

Over the last four years, the Bush administration's policy toward North Korea has shown a marked resemblance to the arguments and strategies developed by congressional oppo- nents to Clinton's engagement policy. Congress continues to shape U.S. policy by encouraging the administration to widen its focus beyond the nuclear issue. Although Congress has occa- sionally taken a harder line than the administration toward North Korea, some members have also criticized the president's uncompromising stance. Over the next four years, Congress will play a critical role in determining how the United States will resolve the nuclear crisis and balance security with human rights considerations.

The 1994 Nuclear Crisis

The outlines of the Bush administration's policy can be traced back to 1994 and congressional concerns about North Korea's refusal to comply fully with International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspections. The 1994 Foreign Relations Autho- rization Act illustrated the depth of this concern.4 The legislation

3. Meanwhile, the POW/MIA issue, which was salient enough in 1992 to prompt the first visit to North Korea by a U.S. senator, is no longer a hot topic, now that remains are slowly being returned. George Gedda, "U.S. Lawmaker to Visit North Korea," Associated Press, December 18, 1992.

4. P.L. 103-236 (All public laws referred to in this essay can be found at the Library of Congress website, thomas.loc.gov.). When Congress directs an agency to carry out a new program it first passes an "authorization bill" that establishes the legal basis for the program. Congress appropri- ates funding for activities that have already been authorized through appropriation bills. See Allen Schick, The Federal Budget: Politics, Policy and Process (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institute, 1995). For a basic overview of the appropriations process, see Robert Keith, "A Brief Intro- duction to the Federal Budget Process," Congressional Research Service Report 96-912 GOV, November 13, 1996.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

188 Karin Lee and Adam Miles

outlined eighteen non-binding policy directives that included an emphasis on regional responsibility, the crucial role of China, and the potential use of sanctions as a punitive measure. These three recommendations, while largely ignored by the Clinton administration, would all later find an echo in Bush administra- tion policy.

For example, the 1994 legislation recommended involving all regional countries, including China, explaining that "[t]he prob- lem posed by North Korea's nuclear program is not a bilateral problem between the United States and North Korea, but a prob- lem in which virtually the entire global community is united against North Korea."® Continuation of China's Most-Favored- Nation status was made contingent in part on its cooperation with "international efforts to obtain North Korea's full, uncondi- tional compliance with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty."6 However, if international coordination proved to be impossible, "the President should employ all unilateral means of leverage over North Korea, including, but not limited to, the prohibition of any transaction involving the commercial sale of any good or technology to North Korea."7 And if North Korea refused to cooperate with the IAEA, the law called for the president to "seek international consensus to isolate North Korea, including the imposition of sanctions." 8

Congressional input was felt more directly in the implemen- tation of the Agreed Framework, particularly U.S. provisions of heavy fuel oil to North Korea. Presidential budget requests were insufficient to meet costs, forcing the president to scrounge money from sources beyond the funds specifically appropriated.9 By the time the Agreed Framework collapsed in 2002, the Clinton and Bush administrations had spent almost $90 million more on the KEDO than Congress had earmarked for the program.10 (See

5. P.L. 103-236, Sec. 529 (11). 6. P.L. 103-236, Sec. 513(5). 7. P.L. 103-236, Sec. 529 (12). 8. P.L. 103-236, Sec. 529 (10). 9. The reasons for the difference between budget requests for KEDO and

actual funds needed would be an interesting area for additional research. For instance, it remains unclear whether the discrepancy can be explained by rising oil prices alone or presidential caution in revealing the true costs of implementing the agreement.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

North Korea on Capitol Hill 189

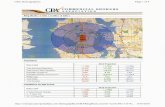

Table 1. Executive Expenditures on KEDO vs. Congressional Appropriations FY1996-FY2002

Congressional Total U.S. Total Appropriations Expenditures Expenditures Above

for KEDO for KEDO Appropriation FY1996 $22,000,000 $22,000,000 $0 FY1997 $25,000,000 $25,000,000 $0 FY1998 $40,000,000 $50,000,000 $10,000,000 FY1999 $35,000,000 $65,100,000 $30,100,000 FY2000 $35,000,000 $64,400,000 $29,400,000 FY2001 $55,000,000 $75,000,000 $20,000,000 FY2002 $95,000,000 $95,000,000 $0

FY1996-2002 $307,000,000 $396,500,000 $89,500,000 NOTE: The Agreed Framework was signed in October 1994, after the appropria-

tions process for the fiscal year 1995 had passed. The Clinton administration informed Congress that approximately $5.5 million would be necessary in FY1995 to supply North Korea with the first shipment of heavy oil mandat- ed by the agreement. This payment, along with $4 million for administra- tive expenses, was made by reprogramming FY1995 Department of Defense funds. (The actual payment was made to KEDO in October 1995, the first month of FY1996.) In subsequent years, the administration further angered Congress by reprogramming funds to make payments to KEDO in excess of the amount actually appropriated by Congress.

Table 1.) Wrangling between the executive and legislative branches

over KEDO funding began immediately. The fiscal year (FY) 1995 Foreign Operations Appropriations bill did not include an appropriation for KEDO, which did not yet exist at the time the bill was signed. Since the first heavy fuel oil delivery was due on January 21, 1995, funding was found by reprogramming U.S. Etepartment of Defense funds, which angered several members of Congress and triggered what would become an annual bat- tle.11 In 1996, Clinton began using an all-purpose presidential

10. KEDO was officially established in March 1995. For a comprehensive overview of the funding for the Agreed Framework FY 96-2005, visit www.fcnl.org.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

190 Karin Lee and Adam Miles

waiver, known as the 614(a) authority, to secure funds for KEDO, only aggravating Congress further. Through additional prohi- bitions and requests for reports on a wider range of topics, Con- gress continued to show its lack of support for the Agreed Framework. In addition, the presidential certification process became increasingly complex, narrowing the negotiating space for the executive branch in dealing with North Korea. Criteria raised in the certification process during the Clinton administra- tion, such as uranium enrichment, became more salient during the Bush administration.13

11. Ralph Cossa, "The U.S.-DPRK Agreed Framework: Is it Still Viable? Is it Enough?" (Honolulu: CSIS, 1999), p. 24, retrieved from www.cscap. nuctrans.org/Nuc_Trans/locations/korea/opusdprk.pdf.

12. The appropriations bills contained both appropriations for KEDO and provisions barring direct and indirect funding for North Korea, an apparent contradiction not all that rare in appropriation bills. The Clin- ton administration may have interpreted the prohibitions to mean that use of the 614(a) waiver was necessary to access appropriated funds. The 614(a) waiver is included in the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, Part III, Chapter 1, under (614) Special Authorities: "The President may authorize the furnishing of assistance under this Act without regard to any provision of this Act, the Arms Export Control Act, any law relating to receipts and credits accruing to the United States, and any Act autho- rizing or appropriating funds for use under this Act, in furtherance of any of the purposes of this Act, when the President determines, and so notifies in writing the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations of the Senate, that to do so is important to the security interests of the United States . . . Before exercising the authority granted in this subsection, the President shall consult with, and shall provide a written policy justification to, the Com- mittee on Foreign Affairs 889 and the Committee on Appropriations of the House of Representatives and the Committee on Foreign Relations and the Committee on Appropriations of the Senate." The waiver is nor- mally used for unexpected events, when funds have not been explicitly appropriated during the normal budgeting process.

13. For example, in the FY1999 Foreign Operations bill, the Secretary of Defense is required to submit a report on "the degree to which KEDO's mission and the Agreed Framework continue to promote important United States national security interests, contribute to delaying North Korean indigenous development of nuclear weapons-related technology, and positively impact the level of tension on the Korean Peninsula." (P.L. 105-277 Sec. 582 (g)). The FY 1999 bill also expresses concern about North Korean missile development. The FY 2001 Foreign Operations

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

North Korea on Capitol Hill 1 91

In 1998, House Republicans responded to a succession of bad news - a North Korean submarine discovered on South Korea's coast in June, August press leaks suggesting that North Korea had built a nuclear facility at Kumchang-ri, and the subsequent North Korean launch of a Taepodong missile over Japan - by cracking down on the Agreed Framework. "I have said from the

beginning that KEDO is an irresponsible policy that we never should have entered into in the first place," Rep. Sonny Callahan (Republican of Alabama) said. "But the administration chose to do it, and we have funded it for the last 4 or 5 years, but it is time to take a serious look at KEDO, especially in light of the fact they are now shooting missiles over Japan and indications are that

they have missiles that very possibly could reach Alaska."14 It was not surprising, then, that when Clinton asked in 1998

for $35 million to pay KEDO obligations, the House responded with zero funds.15 Furthermore, the House bill explicitly prevent- ed the president from using the 614 waiver to drum up more assistance to KEDO from other sources. The Senate version required the president to certify that North Korea was not selling ballistic missiles to terrorist nations before KEEK) funds would be released.16 After the Clinton administration threatened to veto the legislation, a final compromise made in the conference com- mittee met the president's $35 million budget request.17 Howev- er, the legislation retained a "Special Authorities Amendment" that seemed to restrict the executive branch from using the 614 waiver to authorize more than the $35 million already appropri- ated. In addition, the Conference Committee Report warned the

president that the 614 waiver could be repealed if abused.18 Nev-

bill demands that the President verify that "there is no credible evidence North Korea is seeking to develop or acquire the capability to enrich uranium." (P.L 106-429 Sec. 572(b)(5)).

14. Congressional Record, September 17, 1998. 15. HR 4569, 105th Congress. 16. HR 4569, Sec.702 and Sec. 578, 105th Congress and S 2334, Funding for

Department of State, 105th Congress. 17. P.L. 105-277 Sec. 592. On the veto threat see Howard Diamond, frame-

work Funds Endangered by North Korean Missile Test, Digging" Arms Control Today, vol. 28, No. 6 (August/September 1998), online at www. armscontrol.org/act/1998_08-09/nk2as98.asp. Retrieved November 19, 2004.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

192 Karin Lee and Adam Miles

ertheless, the president immediately used the waiver again to spend a total of $65.1 million on KEDO - $30.1 million more than Congress had appropriated (See Table l.).19

Congressional attempts to obstruct the implementation of the Agreed Framework and Clinton's persistence in honoring the agreement frayed the relationship between the executive and leg- islative branches, making it very difficult for the administration to meet its minimal commitments to North Korea much less move forward on the outstanding issues such as lifting economic sanctions. As a result, the atmosphere of mistrust between the two countries deepened. That the two countries possessed very different political systems - emphasized by the U.S. president's inability to compel congressional support - only contributed to the misunderstandings.

Congress Widens Its Attack

Congress and the president waged battle over more than sim- ply the provisions of the Agreed Framework. In 1998, for instance, Congress implicitly criticized the president's policy by demanding that he appoint a "North Korea Policy Coordinator."20 Clinton satisfied the demand by naming his former secretary of defense, William Perry, to the position. The following year, House Speaker J. Dennis Hastert (Republican of Illinois) formed the North Korea Advisory Group (NKAG) comprised entirely of House Republi- cans and chaired by Benjamin Gilman (Republican of New York).21

18. The Conference Report explains that: "The conferees remind the Administration that the section 614 waiver authority is an exceptional provision of law provided to the Administration to enable the President, after prior consultation with the Congress, to waive certain provisions of law because of unexpected contingencies The conferees note that in 1974 this section of the law was nearly repealed" at the request of Sen. Symington, who said that "Congress has given Presidents entirely too much power to use its foreign aid funds.'" Conference Report 105- 825, online at thomas.loc in html format.

19. Apparently, the State Department interpreted the new provision to mean that the president could use $35 million more than appropriated. Congressional Research Service, personal communication, Fall 2004.

20. PL 105-277, Sec. 582(e), signed into law October 21, 1998.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

North Korea on Capitol Hill 193

The Advisory Group, which met for the first time on September 8, 1999, was charged with answering the question, "Does North Korea pose a greater threat to U.S. interests today than it did five years ago?" Not surprisingly, the group answered "yes." It based its conclusion on the assessment that U.S. policy was not address- ing the North Korean military threat, that food aid was insuffi- ciently monitored and was sustaining the regime, and that the U.S. government wasn't addressing a range of other related issues such as drug trafficking, terrorism, counterfeiting, and human rights.22

The food aid issue was a red flag for NKAG, which used the issue of monitoring to focus their attack on food aid 23 Concerns about monitoring food assistance had existed from the start. By DPRK request, for instance, the World Food Program (WFP) could not hire fluent Korean speakers, leaving the WFP staff dependent on DPRK-supplied translators. Nor did North Korea provide a list of all the institutions receiving aid. WFP staff also had to give advance notice of monitoring visits.

In 1999, in response to a request from Rep. Gilman, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) issued a report stating that since the WFP "cannot be sure that that the food is being shipped,

21. "Policy Chairman Cox to Represent House Leadership on North Korea Advisory Group Panel Starts Work; Will Examine Clinton-Gore Effort to Buy North Korea's Good Will," The House Policy Committee Press Release, September 2, 1999; online at www.policy.house.gov/subcom- mittees/107/html/news_release.cfm.744.html. The Advisory Group included the following representatives: Doug Bereuter, Sonny Callahan, Christopher Cox, Tille K. Folwer, Benjamin Gilman, Porter J. Goss, Joe Knollenberg, Floyd Spence, and Curt Weldon.

22. Letter from Rep. Benjamin Gilman to J. Dennis Hastert, October 29, 1999, included in the "North Korea Advisory Group: Report to the Speaker," online at www.fas.org/nuke/guide/dprk/nkag-report.htm.

23. Since 1997 North Korea had become one of the world's largest recipients of U.S. and other food aid, and food aid was meeting at least one-fourth of the country's food needs until 2002. In most years, the United States was the largest international donor to the WFP appeal. Between FY 1995 and FY 2004, the United States contributed a total of 2,053,694 metric tons of food aid, at an estimated cost of $676.3 million dollars. For food aid through FY 2003, see Manyin and Jun, p. 8; FY 2004 numbers come from a personal communication with the State Department. The final 50,000 metric tons pledged for FY 2004 is scheduled to be shipped in February 2005.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

194 Karin Lee and Adam Miles

stored, or vised as planned. . . [it] cannot be sure it is accurately reporting where U.S. government-donated food aid is being dis- tributed in North Korea."24 If monitoring remained "unsatisfacto- ry," the GAO recommended that the secretary of state should consider changes in U.S. policy on food aid to North Korea.

Some members of Congress criticized the report. Rep. Tony Hall (Democrat of Ohio), for instance, complained that the report's "negative bias" did not incorporate the experience of aid workers in North Korea, made monitoring demands on North Korea that were out of sync with requirements in other countries, discounted eyewitness accounts of improvements, and claimed diversion of food aid without proving it.25 "If we refuse to help people who live under brutal regimes, even when we can hide behind the excuse that we can't absolutely guarantee they are getting food," he said, "we are betraying President Reagan's poli- cy that a hungry child knows no politics."

The issue of food aid monitoring did not gain sufficient trac- tion during the Clinton years to interfere substantially with poli- cy. In part, this was due to the U.S. Agency for International Development-funded consortium of private voluntary organiza- tions that lasted from August 1997 to May 2000.26 In addition to implementing the administration's food aid policy, these groups continued to educate members of Congress about the importance

24. "Report to the Chairman, Committee on International Relations, "Foreign Assistance: North Korea Restricts Food Aid Monitoring," GAO NSIAD- 00-35, October 1999, p. 4, online at www.gao.gov/archive/2000/ ns00035.pdf on November 1, 2004. The General Accounting Office was renamed in July 2004; it is now called the Government Accountability Office. (Its acronym remains GAO.) The GAO, known as the "congres- sional watch dog" for its analysis of federal spending, generates reports in response to requests from members of Congress. It is considered to be independent and nonpartisan.

25. Hall came to the forefront of the humanitarian community s attention in 1993 when he fasted for twenty-two days in response to the elimina- tion of the House Select Committee on Hunger. Hall's well-known activism on hunger issues inspired him to visit North Korea six times. He used each trip as an opportunity to encourage assistance to North Korea.

26. L. Gordon Flake, "The Experience of U.S. NGOs in North Korea," in Flake and Scott Snyder, eds., Paved with Good Intentions: The NGO Experience in North Korea (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2003), pp. 29-31.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

North Korea on Capitol Hill 195

of maintaining humanitarian assistance to North Korea.27 As time went on, several NGOs withdrew because of monitoring con- straints.28 Some of these, such as Medecins Sans Frontières (Doc- tors Without Borders), testified in front of Congress in favor of suspending aid until monitoring conditions improved.29 However, in January 2002 enough NGOs were still actively distributing food in North Korea and advocating in Washington to discour- age legislation that would have conditioned food aid to North Korea. While the Senate's version of FY 2003 Foreign Opera- tions appropriations called for "full verification of the use food assistance" in North Korea, this language did not make it into the final bill. Nevertheless, as a result of pressure from interest groups eager to reverse Clinton's politics of engagement, moni- toring of food aid again returned as a congressional issue with the introduction of The North Korean Freedom Act in 2003.31

27. The food crisis also created an opening for Korean Americans to raise funds to provide food assistance to North Korea. Before the mid-1990s, many Korean Americans might have been hesitant to advocate for the North Korean people for fear of being labeled "pro-Pyongyang/' and the resulting political estrangement from the mainstream Korean American community. The June 2000 summit between Kim Jong II and Kim Dae Jung also sparked a new interest in North Korea among younger Korean Americans.

28. Flake, "The Experience of U.S. NGOs," p. 31. 29. "North Korea: Humanitarian and Human Rights Concerns," Subcom-

mittee on East Asia and the Pacific, House Committee on International Relations, 107th Congress, May 2, 2002.

30. The groups argued that other methods of pressuring North Korea would be more successful, and would leave fewer North Koreans at risk. Personal communication, January 2002.

31. "U.S. Representative Benjamin Gilman (R-NY) Holds Hearing on Policy toward North Korea," House International Relations Committee, Octo- ber 27, 1999, p. 8. At first, Hall's arguments prevailed, and the State Department was unresponsive to pressures to make food aid contin- gent on improvements in monitoring. However, in June 2002, the U.S. State Department announced that it would tie increases in food aid to improvements in monitoring. Since that time, food aid has steadily dropped, both because of reduced need and because of the persistence of monitoring issues.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

196 Karin Lee and Adam Miles

Refugees and Human Rights

After George W. Bush took office in 2000, the congressional focus on security began to diminish, and its attack on the engagement policy with North Korea began to coalesce around two key issues: refugees and human rights. Early in the Bush presidency, an idea began to circulate in Washington that North Korea could be forced to collapse by encouraging a mass exodus of refugees. Norbert Vollertsen, a German doctor who had worked for eighteen months in North Korea, was one of the first to articulate this approach. In congressional testimony on June 21, 2002, Vollertsen explained that he was inspired by the exam- ple of the "several dozen [East German] refugees in the West German embassy in Prague" who precipitated the reunification of Germany. He continued,

And then we had the idea, "Oh, let's repeat history. Why not go to the West German embassy in Beijing with some North Korean refugees and enter this embassy and start what finally will lead to the collapse of North Korea and reunification?" . . . We are hoping for a mass escape, like in former East Germany and in Prague, and we hope to repeat history, what will finally lead to the collapse of North Korea, and I think this is the only solution, also for China and for all the people there.32

Soon groups such as the Hudson Institute, a conservative think tank, began to support this approach. Eventually, even Republi- can moderate Sen. Richard Lugar (Illinois) lent credence to this line of reasoning.33

32. Norbert Vollertsen, "Examining the Plight of Refugees: The Case of North Korea," oral testimony before the Immigration Subcommittee, Senate Judiciary Committee, 107th Congress, June 21, 2002.

33. In a Washington Post op-ed, Lugar stated "In the meantime, we should authorize the resettlement of some North Korean refugees in this coun- try, and press our allies to do the same. If this sparks a greater flow of North Koreans from their gulag-like country, some would argue, that could help keep pressure on North Korea or even hasten the fall of the Pyongyang regime, much as the flight of East Germans in 1989 helped undermine the Communist system there. International steps to help North Korean refugees would also be an unmistakable signal to Pyongyang that the world community will not turn a blind eye to the

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

North Korea on Capitol Hill 197

Meanwhile, in October 2002, the U.S. Committee for North Korean Human Rights (HRNK) was established in order to pro- mote the idea that "the United States should make human rights a major component of its relations with North Korea, equal with the demand that North Korea stop developing nuclear weapons."34 At a hearing in June 2003, HRNK's executive director, Debra Liang-Fenton, called for legislation "to help the North Korean people."35 That summer, twenty-one organizations joined togeth- er to form the North Korea Freedom Coalition (NKFC) in order to "oppose any financial assistance by the United States unless there is confirmed, measurable progress on human rights for the North Korean people, and to guarantee the U.S. is in no way responsible for subsidizing or enabling the North Korean government to fur- ther oppress its people."3" Together, the two groups successfully placed North Korean human rights on the Congressional agenda through meetings with staff and members of Congress, briefings, conferences, testimony at hearings, and articles in the South Kore- an and U.S. media. But most significantly, NKFC successfully solicited grassroots support, particularly in the evangelical and Korean American church communities. By March 2004, they had managed to collect over 8,000 signatures in favor of legislation on human rights.

The original version of the legislation promoted by the NKFC, the North Korea Freedom Act of 2003 ,37 provides an impor- tant glimpse into its tactics as well as the emerging consensus in Congress.38 At first glance this bill seems primarily humanitarian

regime's systematic human rights violations and its unconscionable neglect of its people's basic needs. Regardless, we should offer resettle- ment options to North Koreans because it's the right thing to do." Richard Lugar, "A Korean Catastrophe," Washington Post, July 21, 2003.

34. HRNK website, www.hrnk.org; retrieved September 1, 2004. 35. Debra Liang-Fenton, written testimony tor Lite Inside North Korea,

hearing before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, June 5, 2003, 108th Congress, p. 5, online at foreign.senate.gov/testimony/2003/ FentonTestimony030605.pdf.

36. NKFC website, www.nkfreedom.org/about.html. 37. S 1903 and HR 3573. 38. Although some of the ideas promoted by HRNK appear in the Freedom

Act, HRNK is barred from actively lobbying for or against specific legislation.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

198 Karin Lee and Adam Miles

in nature, especially its authorization of nearly $5.5 billion for various humanitarian purposes. Such provisions provided the basis for support of the bill within some sectors of the Korean American community. In fact, however, the bill tried to address all aspects of U.S. relations with North Korea, including the drug trade and weapons of mass destruction. It also sought to pressure the South Korean and Chinese governments to change their policies toward North Korea. The provision of the bill like- ly to have had the greatest impact on security issues, Sec. 403(b), barred all non-humanitarian assistance to North Korea until the country demonstrated substantial progress in human rights issues such as prison reform. Sec. 403(b) might have prevented the United States from offering any incentives to North Korea in negotiations over the current nuclear crisis. Meanwhile, the bill's attempt to include human rights in any discussions with North Korea also potentially jeopardized ongoing attempts to resolve the nuclear crisis.

But blocking negotiations was perhaps not the primary goal. According to Michael Horowitz, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, one of the refugee provisions in the bill was designed to stimulate a "critical mass of refugees" into leaving the country. Such an exodus, he said, would result in an "East European [or] Soviet Union [type of] implosion" of the regime.39 Given the explicit links made by Horowitz, it is not surprising that some members of Congress and their staff saw the bill as a thinly veiled call for regime change. Humanitarian aid groups warned in a letter to Senate Judiciary and Foreign Relations Committee members that the humanitarian provisions in the bill might be counterproductive. It soon became clear that the Free- dom Act would not get much support, especially from the leader- ship of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which endorsed a more practical philosophy.

In an attempt to make the bill less political and more humanitarian, Rep. Jim Leach (Republican of Iowa) revised the North Korean Freedom Act to create the North Korean Human

39. Michael Horowitz, "Corruption in North Korea's Economy," Senate Foreign Relations Committee Hearing, 108th Congress, July 31, 2003, online at foreign.senate.gov/testimony/2003/HorowitzTestimony 030731.pdf.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

North Korea on Capitol Hill 1 99

Rights Act of 2004 (NKHRA).40 Rep. Leach's office consulted with the NKFC as well as groups maintaining shelters in China and those providing food aid to North Korea. The South Korean embassy expressed concerns. In Seoul, National Assembly mem- bers weighed in on both sides of the argument. Twenty-seven ruling Uri Party members sent a letter to the U.S. embassy in Korea against the bill; thirty-three members of the opposition Grand National Party signed a statement in support of the bill.41

The end result was a leaner, cleaner piece of legislation focused almost exclusively on human rights and refugees. Many of the provisions most dangerous to refugees that were included in the Freedom Act were eliminated, as was the relentless and impolitic criticism of China and South Korea. At the urging of Sen. Joseph Biden (Democrat of Delaware) and others, the Sen- ate amended the restriction on non-humanitarian assistance, converting it from a binding prohibition to a non-binding "Sense of Congress" provision. This was done to preserve the authority of the president to negotiate a nuclear deal with North Korea that might include energy aid, other non-humanitarian assistance, or a threat reduction program patterned after the Nunn-Lugar measures used to help reduce nuclear arsenals elsewhere in the world.42

Perhaps most importantly, Rep. Leach differentiated between the regime-change agenda of the Freedom Act and the humani- tarian agenda of the NKHRA. As explained in the House com- mittee report, the NKHRA

is motivated by a genuine desire for improvements in human rights, refugee protection, and humanitarian transparency. It is not a pretext for a hidden strategy to provoke regime collapse or to seek collateral advantage in ongoing strategic negotiations. While the legislation highlights numerous egregious abuses, the Com- mittee remains willing to recognize progress in the future, and hopes for such an opportunity. Indeed, credible and substantial improvements in the human rights practices and openness of the

40. HR 4011. 41. "U.S. Senators Scramble to 'Hot-line' North Korean Human Rights

Act," Chosuti libo, September 10, 2004, online at english.chosun.com/ w21data/html/news/200409/200409100033.html.

42. Sec. 403(b) in the Freedom Act, Sec. 202 (c) in the Human Rights Act.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

200 Karin Lee and Adam Miles

Government of North Korea would help to build substantial good- will with the United States.43

President Bush signed the NKHRA into law on October 18, 2004. Despite the welcome revisions achieved by Rep. Leach, Sen. Lugar, Sen. Biden and others, concerns remain that the bill could have a harmful impact on North Koreans and on regional security. The South Korean government in particular expressed strong reservations about the new law. It has also provided an additional rationale for anti-American demonstrations in Seoul. South Korean Unification Minister Chung Dong-young indirectly criticized the law in statements favoring the ROK's "quiet diplo- macy" approach. He warned, "Human rights problems in com- munist countries have never been solved by way of applying pressure."44 Lee Boo-young, chairman of the Uri Party, stated his concern that the law would have a negative impact and result in North Korea backtracking on its recent attempts to open up to the outside world.45

Implementation of the North Korea Human Rights Act will determine whether it helps or harms North Koreans.46 Misinfor- mation about the law has spread, and apparently many North Koreans now believe that they will have easy access to the United States. Some mistakenly think that the $20 million authorized annually in the bill (and not yet appropriated) will be handed out in lump-sum payments, similar to the amounts meted out to

43. House Committee Report on the Human Rights Act (Report 108-478), p. 12

44. Seo Dong-shin, Minister Doubts Pressure Tactics on Human Rights m North Korea," Korea Times, October 19, 2004, online at times.hankooki. com/lpage/200410/kt2004101916424510220.htm.

45. Park Doo-sik, "Uri Party Wary Over U.S. Human Rights Act.?" Chosuti Ubo (Seoul), September 30, 2004, online at english.chosun.com/w21data/ html/news/200409/200409300045.html. Retrieved November 10, 2004. The opposition Grand National Party, on the other hand, is considering introducing its own North Korean human rights act, as are Japanese lawmakers.

46. An earlier version of the following comments on implementation appeared in Karin Lee, "The North Korean Human Rights Act and Other Congressional Agendas," Policy Forum On-Line, 04-39 A, The Nautilus Institute, October 7, 2004, ordine at www.nautilus.org/fora/ security/0439A_Lee.html.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

North Korea on Capitol Hill 201

defectors by the South Korean government - only bigger since the United States is a richer country.47 Although the refugee advocacy community focused primarily on China during the drafting of the legislation, the first test case has taken place in Russia. In October 2004, a North Korean man fled a North Korean dormi- tory in Vladivostok and entered the American consulate seeking protection as a refugee.48 His fate has not yet been determined. This first test case will more likely proceed successfully if the processing takes place outside the limelight.

Congress can do several things to make sure the bill is effec- tive, and not a humanitarian disaster. First, the U.S. government must avoid the kind of high-visibility approach to refugee protec- tion that has backfired in the past. Norbert Vollertsen announced in November 2004 that there are 130 North Korean refugees in the South Korean embassy in Beijing, promising "more will come." Expecting to receive U.S. funds, Korean-American groups are traveling to the region in greater numbers, visiting shelters so that they can assess the situation "with their own eyes." Such highly visible activities run the risk of exposing and thereby destroying the underground railroad that brings thousands of North Koreans to the South each year. Any funding appropriated as a result of the bill must take such risks into consideration.

In addition, careful attention must be a paid to the appoint- ment of the special envoy for North Korean human rights. Such an envoy should create a separate track to discuss human rights directly with North Korea, outside of the security dialogue, and should coordinate with similar international efforts on the issue. However, if the special envoy uses the position as a soapbox to constantly criticize North Korea from afar, little progress will be made.

47. Next year and in each of the three years following, Congress will decide how much to appropriate for these activities in the following fiscal year, from zero up to the total amount authorized in the bill. Twenty million dollars a year is authorized for aiding North Korean refugees outside of North Korea for FY 2005-2008, and $2 million annually is authorized for the other two categories.

48. James Brooke, "U.S. Asylum Law Faces its First Test," New York Times, November 8, 2004, p. 11.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

202 Karin Lee and Adam Miles

Next Up for Congress

Although members of Congress have very different approaches to resolving the current crisis with North Korea, the general trajectory of legislative policy has been toward a harder line. Congress put obstacles in the way of the Clinton adminis- tration's implementation of the Agreed Framework. It sought to condition food aid and pushed to include a range of non-securi- ty issues in U.S.-North Korean negotiations. And it has pushed hard on an issue- human rights - that threatens to upend nego- tiations altogether.

This harder line may receive an ever more receptive audience in President Bush's second term in office. Already the administra- tion's two most visible advocates for engagement with North Korea - Secretary of State Colin Powell and Deputy Secretary Richard L. Armitage - have handed in their resignations. Con- doleezza Rice's replacement in the National Security Council, Stephen J. Hadley, has already established himself as a hardliner on North Korea.

As noted above, policy pushed by Congress during the Clinton administration became both practice and law during the first George W. Bush term. With the last vestige of resistance in the administration removed, congressional efforts to push a harder line may well shift into high gear. This could mean main- taining North Korea's position in the "axis of evil" through a continued emphasis on North Korean human rights abuses. Congress might also pay increasing attention to North Korea's criminal exports such as drug trafficking and counterfeiting.50 In

49. During May 2002 preparations for the first high-level talks with North Korea, Hadley surprised Armitage by going for the hard-line option when Armitage was pushing for a more moderate option. The resulting compromise set the tone for an increasingly hawkish approach. Glenn Kessler, "For New National Security Advisor, a Mixed Record," Washing- ton Post, November 17, 2004.

50. There were two hearings on this topic in 2003: "Corruption in North Korea's Economy," Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, 108th Con- gress, July 31, 2003, and "Drugs, Counterfeiting, and Weapons Prolifer- ation: The North Korean Connection," Senate Committee on Govern- mental Affairs, Subcommittee on Financial Management, the Budget, and International Security, 108th Congress, May 20, 2003. The May 2003

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

North Korea on Capitol Hill 203

2004, Sen. Jon Kyi (Republican of Arizona) introduced a mea- sure requiring an annual report from the president describing North Korea's role in trafficking illegal narcotics that was not enacted.51 A similar provision is likely to be introduced and easily passed in the next Congress. In addition, congressional pressure for U.N. sanctions on North Korea is likely. Congress may also pass resolutions that link foreign investment in North Korea to worker's conditions, in the same way that the Sullivan Princi- ples were used toward South Africa during the apartheid era. Congress could also attempt to use human rights criteria to deny funds for a new "agreed framework" with North Korea, no matter how advantageous the terms for the United States.

While Congress has spent the last two years refining its approach to North Korean human rights, it needs to take several steps to ensure that its actions have the desired effect of helping rather than hurting North Koreans. Congress must also not abandon the core issue in the current U.S.-North Korean dispute, namely security. Nuclear war, after all, would be a gross human rights violation. The two issues must both be addressed, though preferably on parallel tracks.

In order to achieve its stated human rights objectives, Con- gress must take measures to promote the mutual trust and confi- dence that are the key to advancing U.S. human rights goals in North Korea. In other words, Congress must embed human rights in a larger framework of engagement. In contrast to the current U.S. approach, the European Union offered diplomatic recogni- tion to North Korea with human rights as part of the package. There was a breakthrough in such dialogue during British foreign office minister Bill Rammell's visit to Pyongyang in September 2004. The British raised four cases of concern. After close ques- tioning regarding findings in a report by human rights expert David Hawk,52 Vice-Foreign Minister Choe Su Hon agreed to dis-

hearing made a dramatic impact when two of the witnesses - North Korean defectors - entered the hearing room wearing hoods and testi- fied from behind a screen.

51. S. 925, Sec 815, 108th Congress. (This issue was also raised in FY 1999 and FY 2000 Foreign Operations Senate bills.)

52. David Hawk, The Hidden Gulag: Exposing North Korea s Prison Camps. Prisoners' Testimonies and Satellite Photographs (Washington, D.C.: The U.S. Committee on North Korean Human Rights: 2003), online at www.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

204 Karin Lee and Adam Miles

cuss individual human rights cases.53 Choe also gave "prelimi- nary approval" for a return visit by UK human rights expert Jon Benjamin, who accompanied Rammell on his trip. In addition, Choe agreed to meet again with Rammell to discuss "internation- al scrutiny of North Korea's human rights record." However, Choe insisted that visits from international human rights experts are contingent on "more trust and confidence."54

In fact, trust and confidence are necessary ingredients for advancing any of the U.S. agendas in North Korea. In the current diplomatic vacuum, U.S. efforts to spur improvements of North Korean human rights can only be attempted through outside pressure. But pressure is only one of many tools, and it is often ineffective, particularly when used alone. Change depends on increasing, not decreasing, contacts and information flow, through inviting North Koreans to interact with rest of the world. Not only does the U.S. government want North Korea to understand U.S. expectations, the U.S. government also needs to understand North Korean perspectives. In order for a human rights dialogue to be effective, Congress should learn more about what is happening on the ground in North Korea. It should orga- nize staff delegations to visit Pyongyang. It should encourage exchanges on a wide range of issues so that conversations can run along many lines and with many people. Diplomatic recog- nition would accelerate such exchange. Tom Malinowski, the Washington Advocacy Director of Human Rights Watch, recom- mends the normalization of relations as an early step, not a late one.55

Nor should a human rights dialogue become a barrier to the security dialogue. "I actually don't favor linkage on security issues," David Hawk has stated. "I think if security issues can be isolated, then you should trade security for security. I think that the U.S. should establish diplomatic relations with North Korea

hrnk.org/hiddengulag/ tochtml. 53. Anne Penketh, North Korea Set to Allow Return for British Civil Rights

Scrutineer," The Independent, September 14, 2004, online at news.indepen- dent.co.uk/world/asia/story .jsp?story =561414.

54. Ibid. 55. Tom Malinowski, "The North Korean Nuclear Calculus: Beyond the Six

Power Talks," oral testimony before the Committee on Foreign Rela- tions, United States Senate, 108th Congress, March 2, 2004.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

North Korea on Capitol Hill 205

irrespective of all other considerations because that will enable the U.S. to have more conversations with North Korea and the North Korean people about human rights."56

In pursuing the second track, Congress should pressure the administration to honor its claim that an agreement can be bro- kered to end North Korea's nuclear weapons program. Moreover, Congress needs to demonstrate that it is willing to pay the price. So far, it has failed to do so. In June 2004, Rep. Lynn Woolsey (Democrat of California) offered an amendment to the Department of Defense Appropriations Act of 2005 that would have increased Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) funding (commonly known as Nunn-Lugar funds) by $15 million. Woolsey suggested that "the extra $15 million for CTR could be used to engage Iran and North Korea. It would take the first steps toward working to demolish their nuclear weapons and infrastructure."57 However, Rep. Murtha (Democrat of Pennsylvania), ranking minority mem- ber of the House Defense Appropriations subcommittee, deemed the amendment unnecessary, and it was withdrawn from consid- eration. No similar initiatives have been offered.

Congress has failed to prioritize the abolition of North Korea's nuclear program and must correct this omission as soon as possi- ble. Although an agreement is not imminent, the preparations, financial and otherwise, should be made now. Congress needs to authorize funding for the dismantlement of North Korea's nuclear weapons program, contingent on a verifiable agreement to do so. Such a move would be greatly reassuring to all U.S. partners in the Six-Party Talks, especially South Korea, which has been frustrated with the dominance of the human rights agenda in Congress and its potentially chilling effect on negotiations with North Korea.

Congress must ask the administration to prepare for imple- mentation of a dismantlement program. As former Assistant Sec- retary of Defense Ashton Carter has suggested, a single U.S. offi- cial is needed to oversee a dismantlement program. "Over the his- tory of the Nunn-Lugar program, its projects have been imple-

56. Cited in Paul Liem, "KA Students: Balanced Discussion on NK Human Rights," Minjok-Tongshin English Edition, online at www.minjok.com/ english/index.php3?catagory=engl&code=25690.

57. Rep. Lynn Woolsey, Congressional Record, June 22, 2004, pp. H4703- H4704.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

206 Karin Lee and Adam Miles

merited by Defense, State, Energy and Commerce," he pointed out in a Senate hearing. "These departments have developed expertise in these types of projects, and it would be imprudent not to exploit it for the North Korea program. But we cannot con- front North Korea with the same bureaucratic chaos with which the states of the former Soviet Union still contend."58

Congress should certainly be commended for raising human rights concerns about North Korea, as well as concerns about the conditions of North Korean workers. However, Congress must recover from its amnesia to recall the security agenda that domi- nated its concerns during the first term of the Clinton administra- tion. Congress can and must play a constructive role both in solv- ing the current nuclear crisis and addressing all the issues that fall under the more general category of human security.

58. Ashton Carter, "A Report on Latest Round of Six-Way Talks Regarding Nuclear Weapons in North Korea: 'Implementing a Denuclearization Agreement With North Korea/" written testimony before the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, 108th Congress, July 15, 2004, online at foreign.senate.gov/testimony/2004/CarterTestimony 040715.pdf.

Principal References

Cossa, Ralph. "The U.S.-DPRK Agreed Framework: Is it Still Viable? Is it Enough?" Honolulu: CSIS, 1999.

Hawk, David. The Hidden Gulag: Exposing North Korea s Prison Camps. Prisoners' Testimonies and Satellite Photographs. Washington, D.C.: The U.S. Committee on North Korean Human Rights: 2003.

Lee, Karin. "The North Korean Human Rights Act and other Congressional Agendas," Policy Forum On-Line, 04-39 A, The Nautilus Institute, October 7, 2004. Online at www. nautilus.org/fora/ security/ 0439A_Lee.html.

Lugar, Richard. "A Korean Catastrophe," Washington Post, July 21, 2003.

Malinowski, Tom. The North Korean Nuclear Calculus: Beyond the Six Power Talks," Oral Testimony before the Commit- tee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, 108th Con-

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

North Korea on Capitol Hill 207

gress, March 2, 2004. Manyin, Mark and Ryun Jun. "U.S. Assistance to North Korea."

Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service Report RL 31785, 2003.

"Report to the Chairman, Committee on International Relations: Foreign Assistance: North Korea Restricts Food Aid Moni- toring," GAO NSIAD-00-35, October 1999.

This content downloaded from 181.95.89.249 on Thu, 14 May 2015 11:20:28 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions