newsletter4

-

Upload

alida-favaretto -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

2

description

Transcript of newsletter4

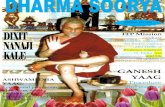

newsletternewsletternewsletternewsletterN°4 – September 2010P.IN.O.K.I.O.Pupils for INnOvation as a Key to Intercultural and social inclusiOn

Foreword byPier Francesco Bernacchi,

Fondazione NazionaleCarlo Collodi p. 2

Tales for social inclusion and integration

The expertise of the International Yehudi

Menuhin Foundation p. 4

The SEED, Stories, Drawings and Digital Storytelling p. 9

© IY

MF

2008

Pho

to P

atrie

s W

iche

rs

FOREWORD

Dear P.IN.O.K.I.O. partners and friends,

I would like to take this opportunity to express my deep appreciation to the University of Madeira for hosting the

second P.IN.O.K.I.O. partners meeting, as well as to all project partners for their commitment and successful

cooperation.

The Madeira meeting focused: on the results presentation for the fi rst project phase; on the discussion and

approval of the training framework and experimentation; on the introduction and approval of a project scientifi c

glossary; on the approval of the educational programme, along with the discussion and defi nition of the evaluation

tools (which were introduced by the external project evaluator), and the presentation of the strategic dissemination

and exploitation plan.

The P.IN.O.K.I.O. project has grown and continues to grow with more partner fi gures. It aims to expand and

create clustering activities in the sphere of research. During the second partner meeting the request from the project

coordinator of the pSkill LLP project to use the M.I.T. software “Scratch” as possible tool for the Creativity Labs

was accepted. There is also a cooperation underway on the use of 2.0 Web with the European project Links-up.

With regards to project activities, we are now entering the experimentation phase! That is why I would like to wish

all the involved schools all the best for their activities, which are about to start on September!

More information about the P.IN.O.K.I.O. project can be found at www.pinokioproject.eu

newsletterN°1 – FEBRUARY 2010P.IN.O.K.I.O.Pupils for INnOvation as a Key to Intercultural and social inclusiOn

Pier Francesco Bernacchi Co-ordinator of P.IN.O.K.I.O. project

Secretary General of the Fondazione Nazionale Carlo Collodi

www.pinocchio.it

2

ONCE UPON A TIME…Yehudi Menuhin, one of the greatest violinists and human-ists of the 20th century, created the International Yehudi Menuhin Foundation in Brussels in 1991 as an interna-tional non profi t making association set up by royal decree. His vision was to give life to long term projects, with the aim of giving a voice to the voiceless through artistic expressions under all their forms. The International Foundation is at the centre and coordinates a network of associations which act as the national operators of its programmes, such as for example MUS-E®.The task the International Yehudi Menuhin Foundation un-dertakes is to remind the political, cultural and educational institutions of the central place of art and creativity in all the processes of personal and societal development. Find-ing its sources in the humanistic work of Yehudi Menuhin, it initiates artistic projects that give a voice to the cultures present in Europe.

This endeavour is realised in several fi elds of action, sup-ported by different programmes:

• art at school: the MUS-E® programme introduces art in primary schools to develop children’s creative powers and release their creative potential, thus preventing vio-lence and racism through fostering harmony and a sense of aesthetics from the earliest age. Implemented in 11 countries, MUS-E® now involves around 55,000 children from 550 primary schools, thanks to the support from the European Union and many national and regional gov-ernmental authorities and private partners. Around 950 artists take part in the programme. Lord Menuhin’s wish was that all children could sing and dance at school every morning. http://www.menuhin-foundation.com/compo-nent/option,com_google_maps/Itemid,120/

• art and intercultural dialogue: The Assembly of Cul-tures in Europe (ACE) gives a voice to non-represented cultural groups by creating a platform through which these groups can express themselves at a European level.Over thirty groups have joined this project in Europe, in-cluding the Roma, Armenians, Laps, Csangos, Pomacks, etc. but also emerging minorities. Today new partner-ships are established with cultural experts, minority ad-vocacy groups, artists, diverse associations or institutions in their fi eld of action (education, social, environment) which combine their activities and generate a thorough refl ection in the platform created around the Assembly

of Cultures. Lord Menuhin’s wish was that all cultural groups could have real access to European authorities and that European institutions could give all cultural groups the practical opportunity of expressing themselves.http://www.menuhin-foundation.com/arts-and-intercultur-al-dialogue

• art on stage: thematic multicultural concerts unite the voices of several cultures through music, singing or dance. Alongside Stéphane Grappelli, Ravi Shankar, Mar-cel Marceau or Miriam Makeba, to mention but a few, Yehudi Menuhin used to introduce us on stage to the soul of a range of cultures through their musical expressions. He knew how to fi nd the words of the heart, creating a magical space that united us all. It is this spirit that the International Foundation strives to perpetuate today by organising an annual concert or artistic event illustrat-ing intercultural dialogue on stage. http://www.menuhin-foundation.com/events/

TALES, ARTS, CULTURESFor many years, the International Yehudi Menuhin Founda-tion has used tales as a medium of encounter between cul-tures of the world (”Nomadic Tales”, “Children from Here, Tales from Afar”, “Little, Little and the Seven Worlds”).

Tales combine the art of relating and performing arts. They are intercultural in essence because of the encounters and confrontations they contain, and are also multicultural be-cause of the different versions of the same storyline pro-posed.

newsletterN°1 – FEBRUARY 2010P.IN.O.K.I.O.Pupils for INnOvation as a Key to Intercultural and social inclusiOn

3

We were keen to convey this approach, which builds up a common store of knowledge and culminates in “iyouwe SHARE THE WORLD”: creating our own stories and tales and exchanging them with those from various cultures in various places in the world, to illustrate the idea that our visions of the world answer each other and bring us closer to one another.

In addition to its day to day activities, the Foundation also carries out specifi c European projects, several of which fo-cusing on the practise of storytelling as a tool of intercul-tural dialogue.

The Foundation relies on its 18 year old strengthened prac-tice in the fi eld of art at school in Europe as well as on the national and local members of its network; and is based on the multicultural expertise of artists in all fi elds of expres-sions, it deploys all the elements and partners during the different phases of the project, thus incrementing their overall effect through a communication plan, the dissemi-nation of good practices and tools; highlighting the diversity of cultures and proposes intercultural leads specifi c to Eu-rope, redeploying national and local specifi cities in a Euro-pean coherence.

EUROPEAN PROJECTS AND INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE

EUROPEAN PROJECTIYOUWE SHARE THE WORLD TOGETHER, LET’S SHARE THE WORLD THROUGH OUR TALES AND STORIES.

The International Yehudi Menuhin Foundation submitted an original project within the framework of the call for proposals launched by the European Commission for the European Year of Intercultural Dialogue 2008. The purpose of this call for proposals was to select seven emblematic projects in Europe, all illustrating the theme of intercultural dialogue.Our project, entitled “iyouwe SHARE THE WORLD”, was among the seven projects approved by the experts of the Culture and Education DG.

This project was based on established practices and relay centres in the fi eld of arts at school in Europe: we asked several of our MUS-E associations to be co-organisers of the project and seven of them agreed. We were also privileged to be able to rely on the expertise of a number of partners, recognised for their competence in various areas: La Maison du Conte in Brussels, the Roma Education Fund in Budapest and the IRFAM Institute in Liège (Research, Training and Action Institute on Migrations), a partner that carried out assessments of the whole project throughout the year. To ensure the successful implementation of the project and its quality, the Foundation called upon the services of a pool of experts in charge of the various aspects and phases of the project: we were delighted to have Hamadi with us again, with his knowledge and storyteller’s sensitivity, to guarantee the quality of the work based on the tales; Patries Wichers, who had already developed with us an expertise in collecting artistic practices at an international level within the MUS-E network and who was in charge of interactivity among the artists involved; Andor Timar, an audiovisual expert for the Foundation, who had already gathered experience in our other European projects based on tales; and fi nally, Julie Godfroid, coached by Dina Sensi who developed evaluation tools for us in the past for the entire MUS-E programme and had therefore acquired a comprehensive knowledge of the subject.

Please refer to the website for full detailshttp://www.iyouwesharetheworld.eu

newsletterN°1 – FEBRUARY 2010P.IN.O.K.I.O.Pupils for INnOvation as a Key to Intercultural and social inclusiOn

4

CONCEPT

“iyouwe SHARE THE WORLD” proposed an interactive work to children from several primary schools in Europe (Hungary, France, Belgium, United Kingdom, Portugal, Germany and Italy) with storytelling artists, visual artists, dancers and/or musicians, in order to recapture a common imaginary world and share it artistically as widely as pos-sible. The unifying theme of the tales was the Cosmogony of the World. This fi rst stage was followed by a sharing of experiences, which took place in Hungary in the form of artists’ residential sessions.

OBJECTIVES

METHOD

• Each MUS-E association chose an artist to participate in the MUS-E programme locally, but originating from an-other country/culture. These artists worked on the theme “how was the world born?” with their class

• Every class created a story/a tale. The artists were in con-stant communication among themselves about the sto-ries and artistic practices

• Once the stories created, the artists told the children the stories from their culture/country/region and the chil-dren did likewise

• Every class transmitted its story to a class from another country, who then gave an artistic format to the tale / story they received (fi lm, theatre, dance...).

• Pooling of artistic content during a residential seminar

14 classes of 25 children, so 350 children in all and their family circle (situated in less privileged parts of France,

Hungary, Germany, Scotland, Italy, Francophone and Flem-ish speaking Belgium, Portugal) were reached through this project. 2 artists per country making it 14 artists from vari-ous origins and cultures, the management, the teachers and the children of the schools participating in the MUS-E programme of the International Menuhin Foundation in Europe all benefi ted from the innovative tools and good practices unveiled by this initiative.

newsletterN°1 – FEBRUARY 2010P.IN.O.K.I.O.Pupils for INnOvation as a Key to Intercultural and social inclusiOn

Discovery To allow the children of the primary schools in Europe to discover common archetypes to all the cul-tures by an artistic approach based on tales from the world and to show them the interdependence of the cultural references and their artistic expression

Increased awareness

To make the primary schools of Europe more aware of intercultural dialogue by broadcasting this experience

Sharing To reinforce the exchanges between artists of various cultures while collecting and disseminating the good artistic practices of the project, to create a new string for diversity

Interculturality To develop an experience within the network while producing and evaluating valuable innovative tools in the schools in Europe and carry out a research on interculturality in Europe with other net-works or projects working in this direction

Intercultural dialogue

To associate world-renowned musicians to act as ambassadors to reinforce the message of intercul-tural dialogue during the concert « SHARE THE WORLD » and make it known at an European level

5

PARTNERS

Associaçao Menuhin Portugal; MUS-E Italia (Italy); MUS-E Hungary (Hungary); MUS-E Belgium (Belgium); East Renfrewshire Council Educ. Departm. (Scotland); Association Courant d’Art (France); Yehudi Menuhin Stiftung Deutschland (Germany); La Maison du Conte de BXL (Belgium); IRFAM (IRFAM = Institut de Recherche, Formation et Action sur les Migrations); Roma Education Fund, Hungary

Credit Suisse Luxembourg ; Deutsche Post World Net ; Merifi n Capital ; Time Warner, MicrosoftRégion Bruxelles-Capitale

Hilton Brussels and Hilton Brussels City, Tradas, Permanent Representation to EU of the Czech Republic, Toyota Motor Europe

EUROPEAN PROJECT “CHILDREN FROM HERE, TALES FROM AFAR”

“ENFANTS D’ICI, CONTES D’AILLEURS” PROJECT, WITHIN THE FRAMEWORK OF THE EU’S “CULTURE 2000” PROGRAMME

The “Enfants d’ici, contes d’ailleurs” project, set within the framework of the EU’s “Culture 2000” Programme, comes under the “Artistic and Literary Creation” area for eligibility concerning projects aiming to link “cultural transmission, artistic creation and social integration”. The project’s objec-tives were the following:

• launching a collection of tales for children submitted by authors from four minority culture groups living in Eu-rope: Armenians, Berbers, Roma and Kurds;

• helping primary school children discover the riches of these unrecognised cultures and involving them in the project by asking them to create illustrations for the tales published;

• showing that art helps overcome the obstacles caused by differences in languages and cultural backgrounds;

• educating children in diversity issues and showing that men and women of different origins experience universal notions such as travel, love, birth, hatred, separation or death in both different and similar ways;

• widely disseminating the good practices experienced in this project thanks to the development of written mate-rial and the presentation of videos on the Web.

This project resulted in memorable achievements such as publishing a series of minority cultures tales in several lan-guages, exchanges and residential seminars with children from various countries studying in multicultural schools as well as multicultural musical creations.

Beyond the tangible results and their dissemination, the project answered some important questions for our practice of cultural diversity:

WHY TACKLE DIVERSITY BY USING TALES?

One of the important aspects of education in cultural di-versity is to show not only differences but also similarities between the cultures concerned.

All the peoples in the world ask themselves the same basic questions concerning life, death, love, birth, marriage, time and space organisation, the place of adults, the elderly and children, etc., although they have given different responses in the course of time and according to the regions of the world.

A tale always has these two layers: it tells a marvellous story (taking place in a particular region, a particular country with its own customs, festivals, dress and climate), while addressing major universal topics (archetypes).

newsletterN°1 – FEBRUARY 2010P.IN.O.K.I.O.Pupils for INnOvation as a Key to Intercultural and social inclusiOn

6

Consider for example the tale of Cinderella, throughout the world about 345 different versions of this story exist. They all tell the story of a kind-hearted, unfortunate girl who ends up fi nding love and becoming rich. But the vari-ants are especially interesting, as they enlighten us on the traditions of other cultures. In the Iraqi version, for exam-ple, the king’s ball is replaced by the henna festival, during which the mother of the prince selects her son’s future wife (NUTI, 2002).

The choice of tales is therefore particularly important. In the “Enfants d’ici, contes d’ailleurs” project, some fi fteen tales were submitted by storytellers. Some are traditional tales, such as the Armenian and Kurdish tales, while others (the Roma and Berber tales) were created specifi cally for the series of books.

The very wide range of topics addressed includes love, travel, the joy of living, the cycle of the seasons, the origins of peo-ples and the genius for creation. They feature men, women, children, animals, fabulous characters, etc. They also teach us about the nomadic life of the Roma, the aridity of the Af-rican desert, the harsh climate of the Armenian mountains, the Persian origins of Kurdistan, and so on.

For those teachers who are sensitive to the magic of tales, one single little story can prove to be much richer than ten school manuals put together, as it will always contain a high number of potentially educational projects, combining pleasure, emotions, listening, values, knowledge, research, writing, analysis and creation.

WHY TACKLE THE DISCOVERY OF CULTURES THROUGH MUSIC?

A Persian poet once said “music is a houri in the paradise of gods, who fell in love with an earthling. The nymph came down on earth to confess her love. Furious, the gods asked a fi erce wind to chase after her. The wind caught her and scattered her in the air, strewing her to the four corners of the world. She did not die, but has lived on to this day in people’s ears.”

Starting to discover cultures via music, via their music, means striving for this houri to be reincarnated in her body and gathering scattered human beings via their most inti-mate part: their heart.Music above all relies on sound and hearing. When we lis-ten to a piece of music, we are immersed in a sound bath that encompasses us and instantly reaches our emotions without going through the medium of our intellect. Con-tact is thus instant and powerful. We are touched in our most intimate, most genuine place, where there is no room for masks or lies. By touching our heart, music reaches our innermost truth. This deep-seated truth is the prerequisite for communication.

Although contact through music is immediate, it also has a timeless quality, since the emotions it generates bring up past memories, crystallized in these emotions. A tune, for example, can suddenly produce intense feelings: nostalgia, sadness, love, suffering, etc. These emotions are common to the whole of mankind and unite us throughout our journey on earth.

While touching us in an immediate and global way, music also induces in us a state of receptiveness and the opening of our consciousness. The idea that music can have an ac-tion on mind and body is nothing new: for centuries, moth-ers have sung lullabies to their children to get them to sleep; for centuries, seamen and farmers have sung songs to buck themselves up at work. For centuries, from Asia to Latin America via the Middle East and Africa, music has been used to reach unusual states of consciousness. The idea that music can enlarge consciousness goes back to its occult origins and the legend of Orpheus, who used it to “charm” living beings.

newsletterN°1 – FEBRUARY 2010P.IN.O.K.I.O.Pupils for INnOvation as a Key to Intercultural and social inclusiOn

7

Music not only opens up consciousness, but may also re-inforce a certain type of “solidarity”. In Antiquity, it was considered that the fact of producing certain note combina-tions and harmonies generated a resonance with the other elements in the world that had the same natural frequency. This resonance made it possible to reinforce at will the pow-er of one’s “single note”. The music schools of Antiquity believed that music connected everything and linked the individual up with the cosmos, developing his physical and mental powers and enlarging his fi eld of consciousness. Mi-crocosm and macrocosm were thus interconnected thanks to music.

We now know that all the elements in the universe are in a vibratory state. Matter itself is made of a certain type of vibratory waves and there is a similarity between the fre-quency of a music note, a colour, the bonds in a chemical

molecule and the vibrations of electrons within an atom. Each vibrates at its own frequency, defi ned by a certain ratio.

Trying to discover a culture through its music therefore means trying to meet it at its most genuine: in its soul and its emotional memory. It means giving it a voice through rhythm and sounds and joining it to dance the dance of life together. It means discovering the “single note” of each culture in order together to create a symphony for the whole universe.

A poet once said “music is the echo of Adam’s fi rst kiss on the lips of Eve”. Since then, this echo has not ceased making pleasure ricochet on fi ngers that play and ears that listen. Glory be to all the great musicians who taught men to see with their ears and listen with their hearts

WHY BRING CHILDREN TO EXPRESS THEMSELVES ARTISTICALLY ON THE BASIS OF TALES AND MUSIC?

This project is primarily set within the MUS-E® philosophy, whose educational principles are learning through experi-ence, pleasure, play, collective success, movement, feelings, a sharing of responsibilities, etc. (Collectif MUS-E®, 2002, p.14).

It was therefore natural to allow the children to be creative on the basis of the emotions generated by the stories told and the melodies that went with them. Several modes of ar-tistic expression were called upon: dance, drama and music; however, the most important one was drawing and painting for illustrations.

Apart from the artistic objectives of the project, which were important in themselves, this participation in the dissemi-nation process had an educational meaning and enabled children to be involved right to the end, within the frame-work of a social action defending the values linked to the fi ght against discrimination and to the valorisation of di-versity.

Naturally, this type of project will not always benefi t from the opportunity of a series of books, but other educational and artistic actions are possible, such as organising an exhi-bition, creating a play, producing a document for families, writing an article in the press, etc.

The most important point was to get children to participate throughout the whole process of creation and solidarity.

PARTNERS, CO-ORGANISERS, ASSOCIATE EXPERTS AND SPONSORS

The Melina programme (Greece), Publishers Editions de Vecchi (France, Spain and Italy), The City of Altea (Spain), MUS-E® Belgium, La Fundacion Yehudi Menuhin Spain, MUS-E Hungary, MUS-E Italia, MUS-E Portugal, L’Institut Kurde (France), Union Romani (Spain), The Armenian Institute (London), Volubilis c/o Le Centre pour l’égalité des chances et la lutte contre le racisme (Centre for equal opportunities and the fi ght against racism) (Belgium), EDEN Academia (Spain), SSM “Le Méridien” (Mental Health Centre) (Belgium), AOL-Time Warner (USA), Merloni (Italy)

newsletterN°1 – FEBRUARY 2010P.IN.O.K.I.O.Pupils for INnOvation as a Key to Intercultural and social inclusiOn

8

STORIES, DRAWINGS AND DIGITAL STORYTELLINGTelling a story, communicating a message, sharing a dream, expressing a fear, collaborating to build up something new: all this is at the basis of the method developed by seed dur-ing the past years and further developed in the PINOKIO project. In 2007 seed met a special education school in Ticino, Swit-zerland: the Istituto Sant’Angelo di Loverciano. The school is attended by children with different disabilities. Children with disabilities often experience diffi culties in communi-cation with adults and peers, both as language diffi culties and as inability to focus on one’s feelings and thoughts, and consequently to express them properly and integrate with other children and in the society. Removing such barriers is one of the main goals of special education, and a key step towards integration. Talking with the school management, seed proposed a project where stories, drawings and digital media were brought together to make a difference for those children, and for their teachers.The following paragraphs present the structure of the project realized by seed in collaboration with the Istituto Sant’Angelo di Loverciano, at the basis of the method then sharpened and refi ned by seed. This text is adapted from the paper “Stories, Drawings and Digital Storytelling: a Voice for Children with Special Edu-cation Needs” by Luca Botturi, Chiara Bramani and Sara Corbino, presented at the Workshop on Interactive Story-telling for Children, in the 9th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children held in Barcelona, Spain, from 9th to 12th June 2010.

BACKGROUND

Children with disabilities of any kind, physical or psycho-logical, often experience diffi culties in communication both with adults and peers. Diffi culties can take the form of language issues, inability to effectively control non-verbal communication, or even hurdles in focusing on one’s feel-ings and thoughts, and therefore to express them properly to others. The impact on affective development can gener-ate anger and frustration, and fi nally hinder learning and development, generating a negative looping effect. Identify-

ing and removing such barriers is therefore one of the main goals of special education throughout all grades, and a key step towards the effective integration of children with spe-cial needs.This case report presents a project where storytelling, draw-ing and digital media were brought together to make a dif-ference in the communicative development of children in special education programs. The project features high inter-disciplinarity, integrating writing skills, fi gurative arts, and technologies, and involved stakeholders at multiple levels, namely school managers, teachers, families and, of course, children.

DIGITAL STORYTELLING AND COMMUNICATION

The project was funded by a local private foundation, Fon-dazione Margherita of Lugano, from fall 2008 to spring 2009 and involved 10 special education teachers and about 40 children with special needs between 5 and 16.

Project idea

The basic idea behind the project is that communication starts from the desire of expressing experience, that is, to share with others the personal encounter with reality. In its basic form, sharing experiences takes the form of stories, as their narrative structure corresponds to our perception of our own life, as it fl ows in everyday life. For this same rea-son, stories are indeed a basic form of teaching; moreover, stories are easy to understand and generate a high level of engagement. But the magic of stories has two sides: one for hearers, and one for storytellers. Stories are not only an effective way to understand content, but also a powerful way of expressing oneself. Learning to tell stories is an opportunity to enhance personal communication competencies. In particular, expression through stories is important for the development of imagination. Much more than the abil-ity to entertain fancy thoughts, imagination is the core abil-ity to imagine reality, to virtually try out actions, and to gen-erate visions to guide experience. Imagination is therefore necessary for thinking about the future and for imagining new possibilities, even for daring to think “out of the box”. Mastering storytelling means two different sets of skills: (a) understanding narrative structures, and (b) being able to give them a shape, verbally or visually and with the aid of different media.The pilot project presented in this paper had the ambitious goal of exploiting digital media for enabling children with

newsletterN°1 – FEBRUARY 2010P.IN.O.K.I.O.Pupils for INnOvation as a Key to Intercultural and social inclusiOn

9

special needs to become storytellers, and through that un-leash their communicative power and achieve new relation-ships with peers and adults.

The role of technologies

The main goal of the project was the valorization of the expressive potential of each participant, the enhancement of their relational skills and the reinforcement of self-confi dence. Instrumental to this was the enhancement of computer, team-working and project-working skills. Digital technologies left the fl oor to communication, and acquired the important role of catalyst and enabler of complex learn-ing, in a playful and highly social environment. Consequently, the focus of this project was not on digital technologies, but technologies served as instruments with a double purpose: (a) motivating children, who are attracted by them; and (b) expanding children’s expressive palette. An important tenet was the decision to use only open source technologies designed for standard education – so not programs for children with special needs. This was done in order to favor integration and to provide opportunities for the development of real-world professional skills. After an extensive review of available applications, the project used the following free/open software tools, installed on Windows machines:

1. Audacity, an open source audio editing tool;2. ArtWeaver, a free image editing tool;3. Windows Moviemaker, a native but free Windows applica-

tion for basic video editing.

Project design

Project activities were designed along three main topic areas:1. Storytelling (creative writing);2. Hand drawing (illustration);3. Digital media, i.e., using the three applications men-

tioned above, in particular digitizing voice (the story), music, and drawings, in order to generate short movies.

The key approach of the project was teacher training: at the organizational level, the project aimed to generating new knowledge and practices within the school, and not only to conduct a nice but not sustainable experience.The project was developed in 4 phases: (a) a 28-hour teacher training program (b) a fi rst classroom work based on telling stories (c) an activity of collaborative storytelling, (d) a con-tinuous evaluation effort that followed all project phases.

Teacher training (phase a)During the fi rst phase teachers and educators were trained on basic skills in storytelling, drawing and ICT, and were helped to develop a self-refl ective attitude about the value of such skills for their daily teaching practice. Basically, teachers were led through the same process of dig-ital storytelling that they were to implement with children later on. Additionally, they were asked to refl ect on the ac-tivities, and to improve their design. For example, teachers and educators were asked to refl ect upon different aspects and patterns of stories, then moving on to the creation of their own stories. In parallel, they were trained on draw-ing skills, focusing on the special techniques that can help when teaching children with special needs. Finally, teachers and educators were trained on the use of software for edit-ing images and audio to be used to package the fi nal product with children.

Figure 1 – a moment from the teacher training

Listening to stories (phase b)While phase a aimed at developing new skills for teach-ers, during the second phase children started to be actively involved in the project. Teachers and educators read some stories in class, and children were progressively pushed to take a more active role, expressing their preferences on top-ics and aspects of the stories.During this phase teachers and students chose a common guiding topic for all the stories: namely, the journey. Meetings with teachers and educators and a psychologist expert in special education were organized during phase b in order to coordinate the activities, indicate a common di-rection and focus on the idea of establishing specifi c educa-tional improvement goals for each children involved in the project and moving toward reaching them.

newsletterN°1 – FEBRUARY 2010P.IN.O.K.I.O.Pupils for INnOvation as a Key to Intercultural and social inclusiOn

10

Telling stories (phase c)The third phase put children in motion, and had them collaborate in creating stories of their “virtual journeys”. Children were divided into mixed-class groups, accord-ing to competencies and interests. Each group focused on a specifi c journey, such as “travel to the South” focusing on animals of the savannah, “travel to North” focusing on Northern area destinations or “travel on a hot air balloon” concentrating on maps and air view. One additional group decided to work on the soundtrack to accompany all stories. Cross-class collaboration, which was unusual in the com-mon practice of the school, was perceived as a great added value of the project. Under this respect, technologies provid-ed an opportunity to “think out of the box” and somehow reinvent also interpersonal relationship between teachers and educators.

Figure 2 - snapshot of one of the digital story videos devel-oped during the project

Figure 3 – another snapshot of one of the digital story vid-eos developed during the project

Children, according to their abilities and a learning plan, developed, wrote, illustrated, narrated and animated stories. The groups, each coordinated by one or two adults, worked in parallel, with moments of “sharing stories”, and keeping an eye on mutual aid – for example, the “hot air balloon” group provided graphic backgrounds for the other groups. The output of the project was surprising: a DVD with over 20 minutes of animated digital stories was presented to the people participating fi nal school year event, along with a live performance explaining the project. The soundtrack, re-corded in a professional studio, was also released as a CD. But such output are only a signal of the much deeper out-comes of the project, which are discussed below.

Phase dDuring all phases, continuing evaluation was conducted to monitor results and evaluate the effi cacy of the approach. The evaluation of the project included three layers:

1. Formative evaluation, i.e., evaluating the actual learn-ing achievements of teachers (for teacher training) and children. Formative evaluation was conducted through a post-training survey with teachers after phase a, and through qualitative data collection by a psychologist, expert in special education, who constantly monitored teachers and educators, participating in class activities and in meetings.

2. Confi rmative evaluation, i.e., for improving the project design, and for identifying an adequate follow-up in the same school. Confi rmative evaluation was conducted through interviews with all participating teachers and the director of the school.

3. Summative evaluation, i.e., for assessing and understand-ing project outcomes at an organizational level, also from the perspective of the organizational change process started and its management. Summative evaluation was conducted through a debriefi ng with the school director at the end of the project.

PROJECT OUTCOMES

Training and project evaluation

Teacher training received very high evaluations both in terms of formative and confi rmative evaluation. In particu-lar, all the three topic areas (storytelling, illustration, digital technologies) were assessed as relevant, and all teachers in-dicated a strong perception of high learning and high trans-ferability to class activities. Indeed, the new skills acquired

newsletterN°1 – FEBRUARY 2010P.IN.O.K.I.O.Pupils for INnOvation as a Key to Intercultural and social inclusiOn

11

by teachers were proofed during the activities carried out in the rest of the project. The project as a whole also was evalu-ated as very satisfactory from the teachers, and highly im-pactful as well. This was clearly expressed in the fi nal inter-views, testifi ed also by the excitement of children. But while explicit assessment refl ected the satisfaction for reaching the end of the project, the evaluation went beyond, trying to assess learning outcomes for children and teachers, and contributions to organizational change.

Learning outcomes

Measuring learning outcomes is a challenge, as deep learn-ing does not always result in explicit and immediate be-havioral change. On the other hand, superfi cial learning sometimes is very visible, but does not last in the long term. The evaluation carried out in this pilot project consisted in teacher assessment of the progress made by children on (a) expressive skills (b) social abilities including group work, and (c) project working skills. The assessment was carried out right at the end of the project, so that the evaluation suffers of the limitations mentioned above. Nevertheless, the outcomes reported clearly indicate that the method de-veloped in this pilot project has a good potential.Teachers reported that children participating in the project engaged much more than expected, activating previously untapped resources. Reasons indicated for this included the novelty of the proposal, the charm of technologies, but also the possibility to express feelings and values in a different way. Children clearly perceived that stories were for others, for a real audience: their parents, their friends, people out-side the school. This apparently little thing, represented a huge stimulus for these children, used to live within a spe-cial education school, rarely relating to the world. This was particularly evident for the groups that recorded the soundtrack in a professional recording studio. Some children who barely opened their mouth during rehearsals, when confronted with a real microphone, instead of being frozen by shyness, just sung as good as they could. The op-portunity of doing something about which to be proud was the defi nitive push for self-confi dence and learning.This un-tapping dynamic was guided by teachers, who en-joyed the opportunity of individualizing learning paths that the project provided. Supported by the project staff, teachers were able to identify individual learning goals, and to inte-grate them into an interdisciplinary project that provided opportunities for everyone. All different tasks were then in-tegrated into the fi nal product, which was everyone’s prod-uct. This feature of individualization with a common fi nal output, was highly appreciated and served as a reference model for future activities.

Teachers also appreciated the update in their teaching skills, not only from a technical and technological point of view, but also in terms of instructional design (individualized learning paths, fi nding a common output as instructional focus, etc.). These newly acquired skills were observed by the director, and confi rmed by the planning of learning projects for the next school year.Finally, the project provided an opportunity for teachers to work together, and to learn to do so beyond class schedules and routines. While teachers feared the more complex or-ganization required, they soon came to recognize this as one of the best outcomes of the project: the extra effort required for coordination was compensated by the discovery of rich peer interactions, and of the combination of more and less challenged children on common tasks.

Organizational transformation

Learning to work together was the most visible project out-come related to organizational change. Teachers started the project as class leaders, and ended it as a team.While the project started as a small pilot, the activity pro-posed were soon recognized as an important place where teachers could refl ect on their role and practice. From this perspective, educational technologies have been the oppor-tunity and the challenge for unraveling old ideas and for starting a process of re-thinking at an organizational level, strongly supported from the direction. The outcomes of the project are stronger peer relationships and richer professional interactions, that result in the devel-opment of educational projects, in more interaction across classes, and in a more positive attitude towards change and innovation.

CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOKS

The pilot project presented in this project weaved storytell-ing, fi gurative arts and digital media into a learning experi-ence to enhance the communicative skills of children with special needs. The project leveraged on teacher training and its evaluation indicated a good potential, which led to high quality tangible output, positive learning outcomes and ini-tial organizational change.The positive achievements of the project led to the extension of teachers training over the following school year, and to the development of new project ideas in the school. Other schools also asked for a new implementation of the project. In particular a primary school and an association caring for children with serious disabilities in Lugano decided to get involved in a project based on seed’s method with the goal of integration of the disabled children.

newsletterN°1 – FEBRUARY 2010P.IN.O.K.I.O.Pupils for INnOvation as a Key to Intercultural and social inclusiOn

12

www.pinokioproject.eu

Lifelong Learning Programme

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication refl ects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.