Albus H4 2017 - ces.edu.pl · Title: Albus_H4_2017.cdr Author: Piyo Created Date: 20170420132541Z

New Purls, Ralph TITLE - ERIC · 2014. 2. 3. · ED 134 114. AUTHOR. TITLE. INSTITUTION SPONS...

Transcript of New Purls, Ralph TITLE - ERIC · 2014. 2. 3. · ED 134 114. AUTHOR. TITLE. INSTITUTION SPONS...

ED 134 114

AUTHORTITLE

INSTITUTION

SPONS AGENCY

PUB DATEGRANTNOTEAVAILABLE FROM

J *

° 15-t4104.4DOCUBBI RESUME

H4 008 596

Purls, Ralph A.; Glenny, Lyman A.Stat Budgeting for Higher Education: InformationSystms and Technical Analyses.California Univ., Berkeley. Center for Research andDevelopment in Higher Education. .

Depaitment of Health, Education, and Welfare,WashIngton, D.C.; Ford Foundation, New York, N.Y.76730-01552; NE-G-00-3-0210246p.'s--Centei for Research and Development in igherEducailon, University of CalifOrnia, Be4kêiey,CalifOrnia

EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$12.71 Plus Postage.DESCRIPTORS *Budgeiing; *Data Analysis; *Educational Finance;

EducatiLonal Planning; Higher Education; InformationSystemp; Program Planning; *State Agenci s;*Stateyide Planning

IDENTIFIERS California; Colorado; Connecticut; Flori a; Hawaii;IllinOis; Kansas; Michigan; Mississippi; Nebraska;New YOrk; Pennsylvania; Tennessee; Texas Virginia;Washirigton; Wisconsin

ABSTRACTIThe eitent to which state agencies are implementing

information systems and analytical methods for budget re

i

iew areexamined. Focus is on '17 states: Califormia.-Colorador-Cn necticut-e-Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, Michigan, Mississippi Nebraska,New York, Pennsylvania', Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Wash ngton, andWisconsin. Trends in baget information to state agencie and thebases for current concerns are reviewed. Higher educatio budgetinformation categories are defined and a typology of inf rmation usesis presented. An overview is given of the trends in info mation andanalysis activities typifying each of the state budget a encies, andthe principal styles of budget review used in the states are alsodescribed. The informational content of state budget doc ments is,delineated, followed by a discussion of the technical an politicalconsequences of using information and analysis systems. he reportconcludes with a discussion of several major considerati ns to beweighed in setting up state-level information and analysis systems.(1BH)

***********************************************************************Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished* materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort ** to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal ** reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality ** of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available ** via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not* responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions ** supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original. *

***********************************************************************

RALPH A. PURVES

LYMAN A. GLENNY.

CENTER FOR RESEARCH A\ N'_-) L)EVELOPMENT N HIGHER EDUCATIONUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA BERKELEY

c'ENTEn Fon n"sEncli ANn DI.:V1-1.onN11.1\"1

UNIVElts1T1' 01. CALIF(MNIA.

e Center for lksearch and De \ elopment in I ligher Edo-Th

catok, i,.,...,,,., in research designed to assist.individuals and organi-zations responsible for Anwrican higher education to improve thequality. efficiency, and availability of education beyond the high school.In the pursuit .of these objectives. the (enter conducts studies which:I ) use the theories and methodologies of the behavioral sciences; 2)seek to discover and to disseininate new perspectives on educationalissues and new solutions to cthicational problems::: seek to add sub-

...,,4stantially to the descriptive and analytical literatT on colleges anduniversities; :il contribute to the systeinatic knowledge of several of thehehavioral s(inces, notably psychology, sociolog4 economics, and

,political science; and 5) provide models of research 'and developmentactivities for colleges and universities planning tuid pursiiing their own

..-priTrams in institutional research.

el

suprord . . L. 47E-f.;-00-3-0210lie21.7,1:, Eda3ation, an4 ;,17,fare, and Urant'

fr7m under:42ng suchjcocruncnt eponorz,kip aro .:nc 3ura:x.-.1. ac'press freely

judg:rr:,?nt Zt :.he Points of14, ropresent th

0.1 .izotit:Ato ,:-,f,Elitc,a-tion ortl2e

State Bucketing for Higher Education:

lacmination Systems andTechnical Analyses

RALPH A. PURVES

LYMAN A. GLENNY

CENTER FOR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENVIN HIGHER EDUCATIONUNIVERSITY Of CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, 1976

.I.rnder_tlw general. title State Budgeting for Higher Education theCenter is issuing nine publications, each with its own subtitle'andauthors. The volumes report three separate but interrelated proj-ects carried on from July 1973 to August 1976, funded as follows:one on state fiscal stringency by the Fund for the Improvementof Postsecondary Education (FIPSE), another on state generalrevenue trends by the Lilly Endowment and the American Coun-cil on Education, and the third on selected aspects of state budg-etary theorY and practice by a joint grant from the National In-stitute for Education and the Ford Foundation. The principalinvestigator for all the projects was.Lyman A. Glenny; the princi-pal author or authors of each volume carried the inajor respon-sibility for it. To varying degrees, all members of the researchteam contributed to most of the volumes, and their contributionsare mentioned in the acknowledgments. This report is the fifth tobe issued in the series.

LIBRARY oF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Purves, Ralph A 1937-

Information systems and technical analyses.

(State budgeting for higher education)Bibliography: p.Includes index.1. Education--United States--Finance.

'2. System analysis. I. Glenny, Lyman A., jo'.nt

.author. I/. Title. III. Series.

L82825.1387 379'.1214'0973 76-51452

Acknowledgments

We are especially grateful for the financial supportprovided jointly by the National Institute of Educationand The Ford Foundation. This cooperative venture ofpublic and private funding agencies has provided a veryhospitable environment for research.

An exceptionally high degree of cooperation andassistance was provided by state and instit'utional officials,often at considerable time and expense and, in many in-stances, during particularly busy periods. Needless tosay, the study was entirely dependent on such help and weare especially grateful for their generous contributions.Answering questionnaires, providing documents, arranginginterviews, and responding to letters and telephone in-quiries are not the most rewarding.activities for some ofthe busiest officials in state government. Yet all weremost helpful.

The representatives of the national organizationswho comprised our National Advisory Panel and the indi-viduals who comprised the Technical Advisory Panel madesignificant contributions to this report through theircritical comments and useful suggestions in response toproject plans and report drafts.. . Their assistance broad-ened our perspectives and provided many useful insights.We are most appreciative. The members of both panels

-dre-listed below.

NATIONAL ADVISORY PANEL

American Association of Community and Junior CollegesDr. Edmund J. Gleazer, Jr., Executive Director

American Association of State Colleges and UniversitiesDr. Allan W. Ostar, Executive Director

American Council on EducationDr. Lyle .H. Lanier, Director, Office of Administrative

Affairs

Education Commission of the StatesDr. Richard'M. Millard, Director, Higher Education

Services

National Association of State Budget OfficersMr. Edwin W. Beach, Past President

National Association of State Universiti,i-and Land-Grant Colleges

Dr. Ralph K. Huitt, Executive Director

National Center for Higher Education ManagementSystems

Dr. Paul Wing, Senior Staff Associate

State Higher Education Executive Officers AssociationDr. Warren G. Hill, Past President

TECHNICAL ADVrSORY-PANEL

Dr. Frederick E. BalderstonChairman, Center for Research in Management ScienceUniversity of California, Berkeley

Mr. Edwin W. BeachChief, Budget DivisionCalifornia State Department of Finance

Mr. Harry E. BrakebillExecutive Vide .ChancellorCalifornia State University and Colleges

iv

Dr. Allan M. CartterGraduate School of EducationUniversity of California, Los Angeles

Mr. Loren M. FurtadoAssistant Vice President--Budgeting and Planning,

and Director of 'be BudgetUniversity of California

Dr. Eugene C. LeeDirector, Institute of Governmental StudiesUniversity of California, Berkeley

Mr. John C. Mundt, Executive DirectorWashington State Board for Community College 'Education

Dr. Morgan Odell, Executive SecretaryAssociation of Independent California Colleges

and Universities

Dr. Aaron B. WildavskyDean, Graduate School of Public PolicyUniversity of California, Berkeley

Dr. Paul E. ZinnerProfessor of Political ScienceUniversity of California, Davis

In addition, we gratefully acknowledge the helpfulcriticism and comment of Frank Bowen, Anthony Morgan,Mel Orwig, and Frank Schmidtlein, who reviewed drafts

may not necessarily agree with the final form theircomments have taken, but they have immeasurably assistedus An_avoiding errors of fact and interpretation. _Weespecially thank Janet Ruyle for guiding the reportthrough production, Harriet Renaud fOr editing the finaldraft, and Mildred Bowman and Margaret Elliott for pre-paring several versions of the manuscript, includingthe final one. .

Preface

From.July 1973'-'to August 1976 three studies of statebudgeting and financing of higher education were conductedby the Center for:Research and Development in Higher Educa-tion at the University of California, Berkeley.

The present study began in July 1973 when the Centerundertook a three-year, 50-state study of the processesused bY state agencies to formulate the budgets of collegesand universities. Seventeen states were studied in-

tensively.*

Financial support was furnished jointly by the eNational Institute of Education (60%) and The Ford Founda

:ftion (40%). The study was endorsed by the following organ-.

American Association of Conmunity and Junior

CollegesAmerican Association of State Colleges and

Universities

* The 17 states were: California, 'Colorado,

"Connecticut, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, Michigan,iMississippi, Nebraska, New York, Pennsylvania, Tennessee,Texas, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin.

American Council on EducationEducation Commission of the StatesNational Association of State Budget OfficersNational Association of State Universities

and Land-Grant CollegesNational Center for Higher Educatim Management

SystemsState Higher Education Executive Officers

Its twofold.purpose is to advance budgetary theory and togive state and institutional budget.professionals a broaderunderstanding of: 1) the interrelationships, roles,functions, and objectives of the several state agenciesin the budgetary process; 2) the congruence or incongruenceof such objectives among the several agencies; and 3) thepractices and procedures that build confidence in thefairness of the budgetary process.

Reports based on the study describe and analyze theorganizational st7uctures and staffing of state-levelagencies and the progress of institutional budget requeststhrough these agencies from the time that prebudget sub-mission instructions are first issued by a state agencyuntil appropriations are enacted. The primary emphasis ison the budget review and analysis process and the proceduresused by the state agencies; the study concentrates on theadministrative interfaces among the several state agenciesthat review and analyze budgets and between these agenciesand the institutions, or systems of institutions, ofhigher education.-

Latensive-interviews-r-doeument-review-i-and-questionnairesjn the 17 states selected formed the basis for anarrative and tabular description and comparison issued

1975.. Less detailed data were collected from 50 states-by questionnaire only; these are examined and presentedin a second.descriptive report.

The other volumes resulting from the three-yearstudy are analytic in nature. This volume focuses on thedevelopment and use of information systems and analytictechniques; Others concentrate on the creation and useof budgetary formulas, the cooperation, redundancy, and

vii

duplication of effort among the beveral state agenciesthat review budgets, and the dilemmas involve& in thedesign of budget processes, along with a step-by-step&nalysis of budget progress througb the labyrinth ofstate agencies and processes.

The second study, sponsored by the Fund for theImprovement of Postsecondary Education (PIPSE), examineshow state colleges and universities respond when statesmake substantial reductions in their appropriations.This one-year study encompasses experience with fincalstringency in about a dozen states, primarily in tne fivestates presented in the case studies. The latter havebeen brought up-to-date as of late spring 1976.

The third study, sponsored by the Lilly Endowmentand the American Council on Education, analyzes the trendsin state general revenue appropriations for higher educa-tion from 1968 to 1975. Refining earlier work at theCenter, the study compares trends among the states forthe several types of institutions in both appropriatedand constant dollars, comparing dollar increases withenrollment trends in each case and also comparing dollarsappropriated for higher eddcation with those for elementaryand secondary education.

Each volume resulting from the three studies drawson significant findings of the other studies yet standsalone as a complete book. However, awareness of the fullpanoply of social, political, and economic variables thatwe found in state budgeting for higher education can begained by-review-of-wkl-the volumes. We-earnestW-hope_the readers learn as much from our resealch as we did inconducting it. 4 complete list of the volumes is foundon the back cover of this book.

viii

Acknowledgments

Preface

1 Introduction

Contents

2 Budgetary and Financial Information:Taxonomies, Uses, and Systems/

Page

vi

1

3 Information and Analysis Developmentin State Agencies: An Overview 30

4 Styles of Higher EducatiOn Budget Review 44

/5 The Context of Formal/Budget Documents 83

e

6 Payoffs from Anaiiisis_and Information Bystems 127

/7 Znformation and/Analysis Systems:

Considerations fcr Design 162. .

Raerences

General/Bibliography

Appendix 1-1. NACUBO Current Funds ExpendituresAccounts, 1968

198

207

209

Page

Appendix A-2. NACUBO Current Funds ExpendituresAccounts, 1974 212

Appendix B. HEGIS Taxonomy of InstructionalPrograms in Higher Education 216

Appendix C-1. Number of Four-Year Public Insti-tutions with Budgets Reviewedby Techniques Discussed 228

Appendix C-2. Number of Two-Year Public Insti-tutions with Budget ReviewsSimilar to Four-Year Institu-tions 229

Appendix D. An Interpretation of a Non-ZeroSum Game: The Prisoner's Dilemma 230

TABLES

1 State Higher Education Agency (SHEA)Responsibilities, 1974-1975

2 Number of Four-Year Campuses without MedicalPrograms Reviewed, by Inclusion in Multi-campus Systems, Focus of Review, and Level ofInforamtional Detail Provided

3 Budget Data Submitted to Executive andLegislative Agencies

4 State Agencies that Prepare Formal BudgetDocuments

EXHIBITS

Page

42

89

92

109

1 Organization of the Program ClassificationStructure 18

2 State of Connecticut Objects of ExpenditureClassification

3 Three Formula Methods for Developing BudgetEstimates of Instructional Costs

4 U.S. Bureau of the Budget PPB Timetable

5 Formal Education Program Structure inthe State of Hawaii

6 Measures of Effectiveness and Units of Measurein the State of Hawaii

7 Summary Decision (SD) Itc, , University ofWisconsin System

8 Examples of Unit Decision Items, Universityof Wisconsin, Madison Campus

9 Proiram Measures Required in PennsylvaniaBudget Submissions, Fiscal Year 1974-1975

10 Overlap of Budgeting Phases

11 Contradictory Elements in Organization andEvaluation

xi

14

50

56

63

66

67

76

78

102

137

184

11.

Introduction

In all, public colleges and universities in theUnited States currently receive approximately 40 percentof their operating income from state tax appropriations.This figure rises to 60 percent when income from noneduca-tional activities and services such as auxiliary enter-prises is subtracted (Carnegie Commission, 1973). Withthe advent of comprehensive executive budgets in moststates, virtually all institutions now request these fundsby means of a formal request procedure routed through theexecutive budget office. Requests from higher education'institutions are considered along with requests from otherstate services and are ultimately the basis for a legis-lative appropriation, signed by the governor. There isconsiderable variation among states, but on the averageabout one-seventh of all expenditures from state generalfunds is appropriated for the operating expenditures ofpublic higher education (Glenny & Kidder, 1973).

The entire scope of the state higher education budget'process from request to appropriation is considered in an-other study in this series (Schmidtlein & Glenny, in pre-paration), which will report on specific details andvariations in the procedures in use in 17 states. Basedon the same 17-state data, the present report is focusedprimarily on the informational and analytical aspects ofbudget requests to the state and the technical proceduresused by state budget agencies to review these submissions.Particular attention is given to the application of methodswhich objectify and rationalize the budget process, suchas program budget submissions, new information reporting

structures and systems, and various microeconomicanalytical techniques that have been developed forbudget preparation and review.

A considerable volume of literature prescribingthe implementation of budgetary reform has followedthe experience with Programming-Planning-Budgeting(PPB) in the federal government. As yet, relativelylittle empirically based research has been reportedon the implementation of reforms to alter and improvethe technical aspects of the state higher educationbudgeting process. For many years budgetary formulassubsumed a great deal of the information and analysisused in higher education. Miller (1964) reported onthe use of "formulas and cost analyses" in state budg-eting for higher education, and Gross (1973) recentlysurveyed the states to determine the extent to whichformulas are used. Identification of the techniquesof budget development and state-level review withformulas has emphasized the inflexibility of formulas

,

whose application has often tended both to lock infunding inequities as well as preserve levels ofsupport. Under current conditions, budget requestsgenerated by formulas cannot always be funded byavailable revenues; furthermore, institutions havedifficulty adjusting to lower enrollments when funding !

is mechanically tied to enrollments by formulas. Thus,

the greater flexibility and disCretion needed in theuse of resources when funds are limited require amore sophisticated technical review of operationsand issues. Consequently, the term formula is usedin this report in a fairly restricted sense, althoughthe subject matter does coincide generally with whatMiller (1964) has treated in his discussion of thetechnical features of formulas. The report in thisseries on formulas (Meisinger, 1976) treats theorganizational and political uses of budgetaryformulas, but does not describe the technical useof quantitative information and its use in supportof budgets, aspects with which we shall be concerned.

16

2

FOCUS OF THE STUDY

A major portion of this report is descriptive, inorder to provide an up-to-date review of the extent towhich state agencies are implementing information systemsand analytical methods for budget review. This is impor-tant for at least two reasons: A descriptive overviewcan lead to more realistic expectations of what stateagencies can achieve in implementation, and it can iden-tify more clearly the options in budget informationgathering and review that state agencies have open tothem. In aadition to describing what each of the 17states does, we have developed analytical categories ofinformation and its use to show both commonalities anddifferences from state to state.

We have.also attempted to evaluate budgetary infor-mation and review systems by considering some of theimplications and consequences 'cd their _use. That analysiscan improve public decisionmaking is taken as an articleof faith, but current use of analysis in the process mustbe understood before changes in its use can have a bene-ficial effect. One university president interviewedexpressed the belief that the outcome of the budgetprocess in his state had relatively little to do witthtechnical budget review procedures. The procedures, hefelt, were only a way of'rationalizing a decision madeon the basis of political realities. At the same time,it was clear to us that the capacity of interest-grouppolitics for adequately resolving all budgetary alloca-tion decisions is overtaxed by the number and complexityof the decisions that must be made.

The methodology for this study has not involvedthe testing of hypotheses nor the application of rigor-ous analytical techniques. Our objective has been todetermine actual state practice rather than to developbudgetary theory. Budget documents and materials fromeach of the 17 states were reviewed to see the kind ofinformation that was submitted and the manner in whichit was displayed. In addition, site visits were madeto each of the states, and to determine the methods ofreview, all state-level officials in executive, legis-

3

17

lative, or higher education agencies involved in theformal examination of higher education operating budgets

were interviewed. Unless one can actually work in anagency for an extended period, "use" of a system or atechnique is difficult to ascertain. On the other hand,

by_being able to talk with budget process participantsat all levels of the state bureaucracy, the outsider maygain an awareness of features of the process that areobscured from the participants. The description in thisreport is intended to describe actual use, not planned orhypothetical use, although plans are important in suggest-

ing future development. If anything, this report may erron the side of implying too great a level of implementationof standardized information collection and rational quan-titative budget analysis, but the trend in this direction

is clear. Current dissatisfaction with the way publicagencies or institutions are serving public needs canrarely be attributed to the use of too much analysis in

the decision process.

PLAN OF THE REPORT

The remainder of this chapter reviews trends inbudget information to state agencies and the bases forcurrent concerns. In Chapter 2, higher education budgetinformation categories are defined and a typology of inT-formation uses is presented, and the sense in whichmanagement information systems are to be understood in

this report is explained. Chapter 3 presents an over-

view of the trends in information and analysis activitiestypifying each of the state budget agencies. Chapter 4

begins the major description of technical budget reviewby describing the principal styles of budget review usedin the states. Chapter 5 delineates the informationalcontent of state budget documents, and is followdd inChapter 6 by a discussion of the technical and politicalconsequences of using information and analysis systems.The report concludes with a discussion of several major

considerations to be weighed in setting up state-levelinformation and analysis systems.

19:

4

TRENDS IN INFORMATION SUBMISSION

The-submission of information to state budget reviewagencies in support of operating budgets prior to legis-lative review is certainly not a new practice, althoughit is one that has increased dramatically over the lastfew years. Discussions of state budgeting for highereducation, even.for the postwar period, are sparse, butsources such as the Council of State Governments (1952),Glenny (1959), Miller (1964), and Moos and Rourke (1959)have suggested that recent requirements for additionalbudget information were initiated long ago, although per-haps only in more isolated instances. For example, theCouncil of State Governments reported for 1948 that outof 162 governing boards reporting, 140 boards (governing327 institutions in 43 states) submitted their budgetrequests to a central budget authority for revision beforethese requests were consolidated and submitted to thelegislature. Only three boards submitted requests direct-ly to the legislature.

What actually may have changed, more than the sub-stance of what is being reported and the way it is re-viewed, is the changed attitude of the general publicand its elected officials, which now see higher educationas an integral part of the state governmental structure.Public institutions have always faced the problem of howto present budgetary demands to state agencies. Currentcriteria for an effective submission or a justified re-quest may relate more to changes in the environmentalcontext in which higher education operates than to itsintrinsic operations.

Although higher education budget submissions tostate agencies have a long history, changes in variousfeatures of these submissions point up some significanttrends:

Quantity. There has been an increase in theamount of data required of budget submissions asstate agencies have sought information on insti-tutional operations in greater detail.

195

Comparability. Attempts at making data morecomparable through the application of uniformdefinitions have peen intensified.

New categories. Information has been requestedin new types of aggregations and categories--quitefrequently in multiple data structures.

New items. Information has been requested onnew items such as educational outputs, targetgroups, and educational unit costs.

Systems. Attempts to build systems for collect-ing and reporting information, particularly throughthe application of computers, have become common.

THE BASES FOR INFORMATION CONCERNS

Seasoned budget practitioners tend to be unimpressedby the promises made, or the expectations held out for manysuggestions for budgetary reform, including changes ininformation submission. ,Thus, one sees. few states in-which these reforms are championed with the same enthusi-asm that they are in some management consultant circlesor graduate professional schools. Yet, state and insti-tutional officials continue to seek new methods for makingbudgetary choices (with new information requirements) inall public agencies, with perhaps greatest intensity inhigher education. Among the many reasons for thisconcern are seven general factors.

1. There is the general concern over establishingmanagement control in a public agency to foster efficiencyand constraint in the use of public funds. Niskanen

(1972) answered the question "Why new methods?" with thegeneral observation that "Governments do not serve us well."He argued more specifically that the budget process isincoherent, that decisions on the parts are inconsistentwith decisions on the total. "Our political processessuggest an increasing demand for individual programs,but opinion polls indicate a substantial and increasingpopular concern about total federal spending" (p. 156).

6

20..

Further, as important as any temporal factor, accord-ing to Niskanen, is the unique factor inherent in

governmental budgeting which is absent in budgeting forcorporate firms: Governments do not face the conditionsthat make the economic calculus and the balance sheetrelevant to a business firm. Governments are nonprofitmonopolies "whose objectives do not provide consistentlystrong incentives to use the economic calculus" (p. 156),and as a consequence, various budgetary procedures arecommonly seen as a substitute for incentives that areformed in a competitive market.

2. The notion'that a minimal level of statewidecoordination is necessary has taken root in virtually allstates, although the individual states differ with respectto the kinds of higher education decisions they considerto be properly within the domain of state responsibility.In budgetary matters, public institutions have clearlyhad to involve state government officials in the processthrough which they receive appropriations from state taxfunds. A well-established method for achieving coordi-nation, which usually stops short of according actualdecisionmaking authority, is creation of a state-levelagency with the responsibility for knowing what thestate's colleges and universities are doing so that theactivities of one can be related to the activities ofthe others. An important resource in fulfilling thisfunction is a formal information gathering and report-ing system.

3. The belief exists i- oome quarters that admin-istration and management in higher education institutionsare somehow not on a par with, say, the management ofcorporate enterprises of similar size. There is there-fore an interest in strengthening formal procedures,especially in the areas of budgeting and fiscal control,which are the core of management responsibility in theprivate sector. A state legislator reflected this viewwhen he noted that many of his legislative colleagueswho had managed private businesses were astonished bycollege administrators' inability to provide informationthat the legislators themselves had considered essentialin their own businesses. This fueled the move in his

7

2 :I

state, as it.had in others, to require that certain in-stitutional information be provided to state budgetaryagencies as.a way of ensuring that the institutions them-selves had the information.

Even when state officials are not greatly concernedabout the capabilities of institutional administrators

. . .

and their systems of management, they may still expressg wish for more detailed information on institutionsbecause they have substantially less control over collegesand universities than they do over other state serviceagencies. One state director of administration indicated,"I would feel more comfortable if we knew more about theuniversity in detail, even though decisions wouldn't bebased on this detail."

4. In the higher education budget process, at leastthree state-level agencies may be striving to carve outa legitimate role. Introduction of reforms into thebudget process is often either the initial step in shift-ing influence or a direct response to it. Because thestate higher education agency is a new participant inthe budget process in some states, it has a relationshipto establish with both the legislature and the governor'sbudget office. At the same time, many legislatures areseeking an expanded role in state policy along the linessuggested by the Citizens Conference on State Legislatures(1971). Policy involvement requires access to informa-tion, and therefore the attempt to take on new or ex-panded functions by these state agencies quite oftenbegins with a proposal for more systematized informationdistribution. Reforms or innovations of the budgetprocess are rarely neutral with respect to power andinfluence relationships that exist between state agencies,and reforms are rarely accepted wholeheartedly by allagencies involved.

5. In some, but by no means all states, recentlyhired budget staff or their ditectors have been.instilled,through academic training or experience in other organi-zations, with the zeal for activism and reform thatcharacterizes the core of ahy established profession.Professions are built around the practice and applica-

228

ly

tion of a codified bOdy of knowledge, and in budgeting,this body of knowledge or discipline stems largely fromeconomics--accounting, public finance, or operationsresearch, and political science. The major tenet of thisprofessional core has been that scientific thinking should

.

be applied to the solution of social problems, and it there-fore tends to emphasize systematic, rational, and quanti-tative approaches to budgeting. An interest in programbudgeting is likely to come from this quarter.

Berdahl (1971), in his treatment of state governmentand higher education relations, has linked informationsystem development in the states with attempts to intro-duce program budgeting for higher education. While theimplementation of program budgeting depends on the avail-ability of systematized information in special categories,so does virtually every other kind of budget reform. Wefound strong and continued interest in developing state-wide information systems even though attempts to implement .

formal program budgeting systems have waned considerably.

6. Although much of the discussion surroundingefforts to improve the management of higher education isexpressed in terms of improving efficiency, there are anubber of indications that the real concern is about thelevel and kind of higher education being provided. Publicpreferences for higher education appear to.be changing,as has been indicated in the recent decrease in age-specific participation rates. The kinds of educationbeing provided are also changing in response to changinglabor market conditions. But because the public doesnot pay for public higher education services in individualunits, the pressure of this changing demand is felt onthe budgetary process. Demand for information is atactic, or ploy, in the bargaining that determines the"price" state government will pay for an entire bundleof higher education services over the course of a yearor a biennium. Having to provide information on somerelatively simple indicators of funding level or perform-ance can serve to weaken the budgetary arguments ofthose institutions which are funded richly according tothese indicators, without making it necessary to increasefunding for institutions which are funded poorly. Those

2 39

who are getting less have the weight of history goingagainst them,,for their existence is evidence that theymanaged to survive the previous year.

Even where the demand for higher education does notappear to be falling in a particular state, the budgetConatraints-of recent years-may make it essential thatstate budgets be pared, and higher education is both amajor expenditure item and vulnerable on political grounds.It is also a highly discretionary item, being funded byalmost all states from the general fund.rather than fromvarious earmarked funds. Except for the community collegesin some states, public higher education is rarely funded'through statutory formulas, as elementary and secondaryeducation or public assistance often are.

Even without any strong connection with the demandfor higher education, new budget techniques are oftentried selectively in higher education. (Apparently scmestates have singled o'jt higher education as an exceptionfrom program budgeti'lg, but x:one of the states examinedin detail for this Litudy had done so.) Howard (1973)has suggested that new budgat techniques be attemptedfirst in gx agency under one head which has limitedduplicaticA and .overlap with other agencies. Highereducation may present special problems when program budg-eting is attempted because of the complexity of its out-puts, but for organizational reasons, higher educationmay be an ad7antageous agency in which to begin.

Recently, the concept of accountability hasbeen invoked repeatedly to justify the increasing penetra-tion of state agencies into the management of higher edu-cation institutions. Elected officials are, of course,ultimately accountable to the electorate and may be votedout of office. But other state executives--departmentdirectors, for example--are not elected and thereforemust be accountable to the electorate and its represent-atives in some other sense.

Accountability has been used in a number of sensesas a characteristic of the web of relationships whosesum total is the governance process of higher dducation

10

1,4

institutions. Accountability appears to have at leasttwo ii4terpretations, both of whiCh lave far-reachingimplications for centralized inforMation reporting andbudgetary review procedures. The first is that account-ability is an extension of the fiduciary responsibilitythat administrators have to assure that budgeted fundsare not spent illegally or improperly. This means thathigher education administrators are accountable to stateofficials for the specific performance of their institu-tions. Because an institution supported by state resourcesis presumed to have a schedule of services to perform,institutional administrators are accountable in the sensethat a postaudit would be possible, at least in theory,which would check performance against specific objectives.This notion of accountability has obvious implicationsfor budget submission and the provision of informationbecause these educational outputs (services) must beidentified, quantified, and linked to budgetary require-ments

The second interpretation focuses attention on deci-sions and choices made by state officials rather than onperformance. Accountability in this sense literally callson administrators to account for their decisions or, inparticular, their budgetary choices, by providing anappropriate supporting rationale that demonstrates theymade considared choices on the basis of adequate andappropriate information and analysis. This is analogousto the management audit function in administration whichtries to ensure that accounting systems are adequate toprevent fraud and mismanagement. To provide decisionaccountability, methods of decision are scrutinized fortheir adequacy in supporting "good" decisions. Budgetary !

requests, then, must be documented with information toshow that decisions have not been reached arbitrarily.

From these seven general factors which seem to liebehind efforts to improve the substance of budget requeststo state agencies, one should not infer that all theinitiative lies at the state level and that institutionsare merely passive respondents to the information demandsof state agencies. More than ten years ago Miller (1964)commented that two problems that act as catalysts for the .

11

2 5

development of budgetary formulas and cost analyses arethe problem of.securing an equitable distribution of fundsamong institutions, and the proclem of providing sufficientlyobjective justifications to satisfy state budget officesand legislatures. He noted some expressions of surpriseat the slowness with which objective devices have beendeveloped and adopted for higher education budgeting, andsuggested.that this was indicative of substantial legis-lative trust and good will toward colleges and universities.At present, *t appears that the reserve of good will towhich he referred is becoming exhausted (more so in somestates than in others, of course), and that the incentivefor providing sufficiently objective justifications tosatisfy state-level agencies is operative once again.The institutions, like the state agencies, have a clearinterest in developing budget information formats andsubstance which will win the approval of their statereviewers.

2 3

12

2.Budgetary and Financial Information:

Taxonomies, Uses, and Systems

Although the states differ markedly in the detailsof their budgetary procedures, the broader issues involvedin the submission of higher education data to supportrequests for state appropriations are remarkably similar.These issues commonly pertain to:

41, The kind of data to be provided

The format or organizing structure withinwhich the data are collected or displayed

The uses of the data in the budget process tosatisfy various budgetary functions

The development of systematic procedures forgathering and reporting data

Each of these topics is the subject of a lengthier dis-cussion in subsequent chapters. However, in order todefine the substance of these issues and the terms usedto describe them in this report, this chapter is devotedto a brief discussion of the concepts and theory whichwill be applied in the subsequent description and analysis.

KINDS OF DATA AND SYSTEMS FOR ORGANIZING THEM

Data are simply recorded facts or observations whichbecome information when they are related to a decisionin a particular context. Budgetary data are principally

2'7

expenditures of some sort, but they may also includemeasures of institutional activity related to students.,facilities, instruction, research, administration, andeducational outcomes expressed in various dimensions. In

addition to the distinguishing subject matter to whichdata pertain, there are three important characteristicsthat distinguish the data used in the budget process fromdata used in other organizational and management activi-ties: the extent to which data are combined or aggregated;the origin of the data as either observation, estimation,or projection; and the perspective used in combining thedata.

Data which describe a single event or transaction,rather than a sum of many similar events over an extendedperiod of time, are not very useful during the early stagesof the budgeting process because of the emphasis on theplanning function during this stage. Attention is directedto aggregates of expenditures and activity levels becauseit is usually unnecessary, if nut impossible, to specifytransactional details in advance. Because the focus ison a future period, the data in budget requests are largelyestimates and projections rather than what might be called"hard" data, that is, actual observations from the histor-

-i.Cal past.

Systems for organizing data primarily arise from twoperspectives: an operational perspective which relatesdata to the day-to-day operations and activities of in-stitutions and a programmatic perspective which relatesdata to the objectives and goals of an institution. Inpractice, operational data systems are structured in termsof the items or objects for which budgetary expendituresare made, or the functional and support activities whichinstitutions are engaged in. Programmatic data structures,in theory, differentiate the purposes of governmentalactivity into distinguishable programs which may or maynot parallel organizational lines, depending on thestructure of bureaus, agencies, and institutions. In

practice, however, a programmatic structure is difficult.. to distinguish Irom functional or activity classifica-tions, because an agency's goals and missions are mosteasily stated in terms of its activities, which also

214

serve to distinguish the agency along organizational lines.Data structures for each of these expenditure perspectivescould be unique to a state's procedures, but in the interestof achieving comparability they are usually applied accord-ing to standardized conventions, with various modifications.

Object of expenditure categories refer, of course, tothe specific items which a budget will purchase. Followingis the object of expenditure classification used in federalbudgeting (U.S. Bureau of the Budget, 1960).

PERSONAL SERVICES AND BENEFITSPersonnel compensationPersonnel benefits

.Benefits for former personnel

CONTRACTUAL SERVICES AND SUPPLIES,Travel and transportation of personsTransportation of thingsRent, communications, and utilitiesPrinting and reproductionOther servicesSupplies and materials

ACQUISITION OF CAPITAL ASSETSEquipmentLands and structuresInvestments and loans

GRANTS AND FIXED CHARGESGrants, subsidies, and contributionsInsurance claims and indemnitiesInterest and dividendsRefunds

Most states employing such a classification use a morecondensed version which only shows Personal Services,Contractual Services, Supplies and Expenses, and CapitalExpenditures. The principal merit of this kind of class-ification, at least in its more detailed version, is thatit merges directly with the budget execution phase of cen-tral budget office activity. Because budgets are spent on

15

2 9

objects in individual transactions, budgetary planning inthis same mode can be linked directly with the allotmentand control of funds during budget execution. The set ofcategories in use is clearly applicable to all kinds ofagencies.

The standard classification of institutional functionsand activities is that devised by the National Associationof College and University Business Officers (NACUBO), thebasis of the accounting structure that virtually all in-stitutions use for their financial reporting. The detailsfor the current funds expenditure accounts are shown inAppendix A-1. Its major expenditure categories, whichare the aggregates used in functional budgeting are:

EDUCATIONAL AND GENERAL EXPENSEInstruction and Departmental ResearchOrganized Activities Related to Education

DepartmentsSponsored ResearchOther Separately Budgeted ResearchOther Sponsored ProgramsExtension and Public ServiceLibrariesStudent ServicesOperation and Maintenance of Physical

PlantGeneral AdministrationStaff BenefitsGeneral Institutional Expense

STUDENT AID

AUXILIARY ENTERPRISES

The source for this structure of accounts is the NationalAssactation, of College and University Business Officers(1968), 2nd edition. It should be noted that the 3rdedition of this volume (1974) is now available and pro-vides a new set of functional classifications which aresomewhat revised from those shown above. At the time ofour field investigations, this new set of accounts was

rInOXY

16 ,

not yet in use at the state level, and therefore "func-tional" in this report should be associated with theaccoun1s from the 1968 edition. Institutions will grad-ually shift to the new structure, and it may be assumedthat state-level classifications will change as a result.Although some changes in assignment of activities tovarious functions have been made in the new structure,the major changes involve new aggregations of major func-tions and slightly altered names. These are changes whichshould be accomplished at the institutional level withvery little delay. Appendix A-2 contains a descriptionof the most recent NACUBO current funds expenditureaccounts.

The standard programmatic structure is that developedby the National Center for Higher Education ManagementSystems (NCHEMS) in the Program Classification Structure(Gulko, 1972). Exhibit 1 displays the version that appearedin the 1st edition of the Program Classification Structure.This structure was intended as the basis for developing aformal program planning and budgeting system for highereducation. However, inspection of the individual programs-reveals that they are not very different from the func-tional categories of the NACUBO classification. As notedearlier, a longstanding technical difficulty in the appli-cation of program budgeting has been the specification ofa program structure that can be linked unambiguously withan existing system of bureaus or institutions. In March1974, a Joint Accounting Group, consisting of represent-atives of NACUBO, the American Institute of CertifiedPublic Accountants, and NCHEMS designed a set of expend-iture subcategories and "cross-over" conventions whichmakes it possible to relate expenditures reported accord-ing to the NACUBO chart of accounts developed in the1974 edition of College and University Business Adminis-tration to Gulko's (1972) Program Classification Struc%ure.A comparison of these two account structures can be foundin Collier (1975).

For all intents and purposes, any conceptual dis-tinction between the two systems is removed when data tobe formatted according to the Program ClassificationStructure is derived from an operational rathern than a

3117

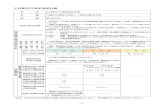

Exhibit 1

ORGANIZATION OF THE PROGRAM CLASSIFICATION STRUCTURE

CAMPUS

1.0

INSTRUCTION

2.0

ORGANIZEDRESEARCH

3.0

PUBLICSERVICE

4.0

ACADEMICSUPpORT

5.0

STUDENTSERVICE

INSTITUTIONALSUPPORT

7.0

INDEPENDENTOPERATIONS

1.1 GeneralAcademic

2.1 Institutes& Research

3.1 CommunityEducation

4.1 Libraries4.2 Museums &

5.1 Social &Cultural

6.1 ExecutiveManagement

7.1 InstitutionalOperations

Instruction Centers 3.2 Community Galleries Development 6.2 Fiscal 7.2 Outside1.2 Occupational 2.2 Individual Service 4.3 Audio- 5.2 Supplementary Operations Agencies

& Vocational Of Project 3.3 Cooperative Visual Educational 6.3 GeneralInstruction Research Extension Services Services Administrative

1.3 Special . Service 4.4 Computing 5.3 Counseling ServicesSession Support & Career 6.4 LogisticalInstruction 4.5 Ancillary Guidance Services

1.4 Extension Support 5.4 Financial 6.5 Physical PlantInstruction 4.6 Academic Aid Operations(for credit) Administration 5.5 Student 6.6 Faculty &

& Personnel Support Staff ServicesDevelopment 6.7 Community

4.7 Course & RelationsCurriculumDevelopment

Reprinted from Gulko, W. W. Program Classification Structure (Technical Report 27). Boulder, Colo:

National Center for Higher Education Management Systems at WICHE, 1972, p. 19.

programmatic set of accounts. The major practical conse-quence of using functions rather than programs is that

.

use of the functional set of accounts results.in a largernumber of budget categories and slightly different aggre-gations of the major subcategories. For the budget year1974-75, both sets of accounts were being used by variousstates. In 17 states we found no use of a programmaticaccount structure based on higher education goals andobjectives. Although conceptually one can envision thatsuch an account structure might be designed (see Dyer,1970),. in practice it is expedient, if not essential, tobase "program" expenditures on operational data. Inhigher education, as with many social services, a program-._

matic structure for budgeting is difficult to establishbecause the recorded operations of the institution, itsbasic operational transactions (enrolling a student,hiring a faculty.member), do not explicitly involvemeasuring attainment of its stated goals and objectives(student development, expanding knowledge). Nonetheless,in many instances, the use of programmatic classificationsin budgeting is indicative of a subtle shift towarda moresubstantive review of agency activities and intentions.

Contained within the Program Classification Structureis another standard structure, that of the various disci-plines issued in the National Center for EducationalStatistics (NCES) Taxomony of Instructional Programs(Huff & Chandler, 1970). This structure, like the Pro-gram Classification Structure, does not usually coincideexactly with the organizational arrangement of instruc-tional departments in a college or university. However,the extens.we use of this structure in the data gatheringactivities of NCES makes it a logical choice as an in-

r. program structure for use in budgeting. Itis known as the Higher Education General InformationSurvey (HEGIS) Taxonomy and is shown in Appendix B. TheHEGIS taxonomy and codes are used widely in budgetingat the two-digit and four-digit levels.

The broad uses to which budgetary data may be putin planning, decisionmaking, or controlling are obviouslynot equally served by the various means of data organiza-tion. Consequently, budget submissions often include

19

3 3

data in more than one format. It may be particularly use-ful in some instances to mix display formats by further

disaggregating data already classified by program orfunction into object of expenditure categories. It is

also possible to preserve the underlying higher education

organizational structure by displaying organizationalunit data in terms of objects, functions, and.programs,or by some mix of these, and then recombining them at the

state level.

USES OF DATA IN THE BUDGETARY PROCESS

Use implies purposes and objectives, and therefore

use of data in the budgetary process must be interpreted

with reference to the functions or the purposes of budg-

eting. The budgetary process moves through a cycle of

phases which may be described as "preparation and sub-

mission," "approval," "exedution," and "audit" (Lee &

Johnson, 1973). Each of these phases serves particular

functions. In the context of state budgeting for highereducation, the first two of these phases were described as"institutional budget preparation and submission," "agency

, review and analysis," and "legislative review and appropria-

tion" (Glenny, Bowen, Meisinger, Morgan, Purves, & Schmidt-lein, 1975, pp. 27-31). This study of information andanalysis systems, like the broader study reported on in theother volumes'in this series, is concerned primarily with

agency review and analysis and legislative review and

appropriation. Legislative approval of the budget and the

use of the governor's veto are procedural features of the

process which bave interesting variations among the states,

but do not directly involve the use of information andanalysis and thus are outside the scope of this report.

Analysis and the use of quantitative justificationshave their primary.application during budget preparation,

but information submission continues during execution of

the budget and is also a primary concern in connection

with the process of postaudit. We examined the process

of institutional budget preparation and submissionselectively because it precedes the process of state

agency review, but execution and postaudit were not

20

generally considered. The portioh of the budget processon which we concentrated attention--budget preparation andsubmission--is the one most suited for relating plannedexpenditures to the pel.acy objectives of state officials.and higher education,administrators. In the everyday workof budget agencies, the entire range of budget cycle ac-tivities is often carried on simultaneously because pro-cesses overlap for past, current, and future budget cycles.As a consequence, there are many opportunities for inter-action between budgetary functions and the use of dataduring different phases of the process. Thus, use ofdata during the agency review and analysis phase cannotbe completely decoupled from the control function ofbudgeting, which is more directly associated with budgetexecution.

Current discussions of budgetary functions areheavily influenced by the functions derived by Schick(1966) from a functional classification Of managementplanning and control systems described by Anthony (1965).From this perspective the budgetary process is simply aparticular planning and control process. Anthony definedthree categories of managerial process as: strategicplanning--the process of deciding on objectives of theorganization, changes in those objectives, the resourcesused to attain those objectives, and the policies thatare to govern the acquisition, use, and disposition ofthose resources; management controlthe process by whichmanagers assure that resources are obtained and usedeffectil,ely and efficiently in the accomplishment of theorganization's objectives; and operational control--theprocess of assuring that specific tasks are carried outeffectively and efficiently. Management control isdistinguished from operational control by requiring some-what greater judgment and by being concerned with thedirection of people rather than the accomplishment ofspecific tasks. Although Schick's (1966) own discussiontended to support treatment of these processes as separateprocesses, he emphasized that:

Operationally, these processes often areindivisible, but for analytic purposes theyare distinguished here. . . . Planning is

21

3 5

linked most closely to budget preparation,but it would be a mistake to disregard themanagement and control elements in budgetpreparation or the possibilities for planningduring other phases of the budget year. The

management process is spread over the entirebudget cycle; ideally it is the link betweengoals made and activities undertaken. . . .

Control is predominant during the executionand audit stages, although the form of budgetestimates and appropriations often is deter-mined by control considerations. (p. 244)

-Schick's treatment has also stimulated a conceptualiza-

tion of the budgetary process as the analog of a zero-sum

game in which increased emphasis on planning and manage-

ment lead to decreased emphasis on control and vice versa.

However, as the discussion of public budgeting has been

elaborated by further studies of governmental budgeting,

most o6servers have come to regard shifts in emphasis

on the various phases of the budget process as responses

to changing budgetary environments and policy contexts

rather than phased shifts from control to management and

planning. Thus, with the reservation noted above concern-

ing the interaction of functions among phases, the pre-

paration and review phase is predominaritly one that

emphasizes planning, although the degree of emphasis on

planning varies among states and within a state itself

as revenue conditions and policy ooncerns change.

Our impressions are that state managerial control

systems function largely within higher education systems

or institutions. Operattonal control, where.it exists,

is clearly at a lower level within the institution. How-

ever, state-level managerial and operational control

systems do exist in the form of position control, re-

strictions on the transfer of funds between budget

classifications, and other procedures designed to achieve

compliance with central policy at the operating level.

Although these systems are outside the budget preparation

and review process, they are often important in setting

the basis for subsequent controls.

Schick's classification neither explicitly treatedthe overtly political or organizational functions of thebudgetary process nor recognized the distinctions betweeninternal budgeting within an agency and budgeting involvingthe overhead control organizations which are participantsin the state budgeting process for higher education(Simon, Smithburg, & Thompson, 1970). As overhead controlagencies, state budget agencies are involved in managementmost frequently through monitoring the activities of lineorganizations. Often excluded from direct responsibilityfor higher education management decisions by subtle andnot so subtle differences in authority stemming fromconstitutional status or tradition, budget agenciesnevertheless influence management decisions throughtheir ability to impose budget sanctions.

During state agency review, the explicit use of in-fbrmation appears to fall into four activities,.describedbelow.

1. Checking. Involves the detection of error inbudget requests, and ranges from detecting and removingarithMetic errors to the more substantive checking in-volved in eliminating unintended consequences of proposedexpenditures--such as a legal conflict, or a conflictwith federal or local expenditure programs.

2. Costing. Not merely calculation, costing isthe attempt to estimate the justifiable fiscal needs ofa proposed program or organizational unit in light ofhistorical accounting costs. Usually, the basis for thiscalculation is the preceding year's budgetary requirements,but inflation, changes:In.adtivity levels, the existenceof joint products, or the fact that there has been noprevious expenditure for a comparable item may necessitatethe application of judgmental estimates and cost-alloca-tion conventions.

3. Evaluation. Ultimately requires, as the wordimplies, setting a value on the program in question inrelation to other expenditure programs. It usually beginswith procedures for examining programs in comparison toother programs in terms of their costs, or with respect

to the technology of the program, as in a considerationof the use of inputs for the program. Evaluation mayalso include an examination of earlier program impactand performance. .Formal evaluation procedures are fre-quently grounded in economic theory and cost-benefitanalysis. Values are measured by market prices wherethese are available, or are estimated by means of avariety of techniques (see Chase, 1967). The cost concept'employed is that cost is the value of resources when em-ployed in their mos.t valued alternative use. Clearly

this may be very different than historical cost. For

example, under the concept of historical cost, facultycosts would be estimated from what faculty salaries have_

been historically. In a cost-benefit analysis, however,faculty costs might be estimated from the faculty salariesof the highest paying comparable institutions, or thesalaries of comparable professionals in industry orgovernment.

Final valuation of programs tends to be implicitrather than explicit, and often comes as a result ofbargaining--as in the determination of a price for atransaction in the market place. The price an individualis willing to pay for a service depends on his personalvalues, although if the provider is to stay in business,the price agreed on must cover the cost of providing theservice. In state-budgeting, it is a widely establishedprinciple that the price paid by the state,for the pro-

. vision of public;higher education services be determinedby the accounting cost of that service. This, however,

tends to suppress what are really questions of societalvalues, especially when the provision of a new socialservice or the suspension of a continuing service isbeing considered. In the interest of consensus, bindingbudgetary procedures, such as formulas that combine cost-ing and pricing in a single operation, are often used toblur the distinction between costing and pricing (evalu-ation).

4. Bargaining. The final adjustment of recommend-ations and appropriations at the margin in which commonground in the preferences of participants is sought, after

Which the result is adjusted to reflect the realities of

33-24

political influence and authority. In l'argaining, infor-mation is used as a resource in trying to persuade, orto gain a competitive advantage over other budget process,participants.

From a broader and more behavioral perspective,Burkhead (1956) described governmental budgetary functionsas "expertise," "communications," and "responsibility"functions. The purpose of the expertise function is toassess economic., sociological,'administrative;-and tech-nological considerations that can be infOrmed by facts.It consists of measuring and comparing a broad range ofcharacteristics of current governmental efforts., the-consequences of such effort's, and their alternatives.The communications function involves gathering the viewsand preferences of interested and affected groups, andthe responsibility function employs means and procedures I

for appraising the political acceptability of alternativeproposals and establishing patterns of responsibility for.,making budgetary choices. In effect, the budget processmust establish ground rules as to who will have access tobudgetary decisions and who will take the responsibility.BurkheAd argued that a legislative budget system is nottruly a budget,system at all because responsibilitypatterns are so often ill-defined. Budgetary functions,however, cannot be compartmentalized; all functions aremerged in the final budgetary decisions.

Burkhead's conceptualization of the functions ofgovernmental budgeting encompasses far more than the useof information and analysis systems. Indeed, because itrecognizes the political and the legitimating functionsof the budgetary process, it covers more than the pro-cesses of planning, management, and control. This reportwill shed more light on the technical use of information,that is, on the use of information which satisfies the"expertise" function in budgeting. These technical uses,however, must be considered within the context of thewider functions of the budget process because, as sug-gested in Chapter 1, new methods of budgetary choicesare not being considered solely or even principallybecause of technical inadequacies in the present process.Deficiencies in responsibility and Communications

3 9

functions are currently considered to be a problem in thearea of accountability.

INFORMATION AND ANALYSIS SYSTEMS

Administrative procedures are increasingly referredto as management systems, for in many instances thesepractices not only involve comprehensive and centralizeddirection and management, but sometimes also automated.data processing equipment and computer systems. Thisreport deals with the information reporting and analyticalprocedures used in state agency review's of higher educa-,tion-,budgetsand-thus,-by-extension-,-,with:-the-information_,,___,_

and analysis systems that state agencies are developingfor meeting their specific budgetary responsibilities.

During the course of this study, we sensed that budgetprocess participants had a fundamentally ambiguous attitudetoward information and analysis systems. On the one hand,virtually every state agency and higher education institu-tion spoke of the need for developing comparable sourcesof information across a bl,..ad spectrum of higher educationnd socioeconomic phenomena; on the other-hand, very fewagencies or institutions have developed these sources intoa widely recognizable, acceptable management informationsystem (MIS). A large part of this uncertainty over theuse of management information systems in the state highereducation budget process results from an inability of those'who would implement these systems (as well as those whowould save us from them) to precisely define what theymean.by a higher education management information systemat the state level.. Some consider MISs to be anotherchapter in the ma,a.-.7-!.Lent philosophy which sired PPB(Planning-Programming-Budgeting), MBO (Management byObjectives), and PERT (Program Evaluation and ReviewTechnique). Many who use the term emphasize the use ofautomated data processing equipment and computers. Othersuse it to.mean little more than an extension of what "good"managers, planners, and analysts "have always done" intrying to gather more reliable and more comparable datato aid managerial decisionmaking. From a somewhatnarrower perspective, according to Weiss (1970), manage-

ment information systems may be patterned after fourbroad models which are, however, not mutually exclusive:

A combination of functional internal and ex-ternal information gathering networks which serve theinfcrmation needs of the organization.

A part of the management process which assistsin fulfilling the decisionmaking function of management,primarily in the areas of planning and control.

A managerial reporting system in which informa-tion is routinely reported on a preset schedule for cen-tral storage, from which it can be withdrawn by varioususers.

An information processing system consisting ofhardware, software, and human beings.

From the description of information and analysisprocedures discussed in the following chapters, aisess-ments can be made of how extensively MISs have been imple-mented. It is important, however, in making these esti...mates, to have in mind what seem to us to be some definitefeatures of MISs, the primary one being that they are in-tended for management and should be regarded as part ofthe management system. The elements of information systems(other than MISs) can be specified by listing informationtAsks comprised in a general automated system.

Data collection: Observing and recordingevents and transactions.

Data conversion: Changing data containedin an original document into a more suitableform for processing or storage.

Data transmission: The process of movingdata from one location to another byphysical or electrical means.

Data,represontations Representing data ina machine-readable form so as to facilitateprocessing.

27

41

Data organization: Arranging data in theform of files, records, so that they can beprocessed and retrieved efficiently andeconomically.

Data storage: Storage of data on appropriatemedia so that they will be easily accessibleto the central processor.

Data manipulation: Selecting, sorting,merging, and/or editing data so as tofacilitate further processing.

Data calculation: Performing various arith-metic and logical operations on data so,asto produce desired information outputs.

Information retrieval and display: Retrievinginformation, or processed data, from infor-mation storage, and making it available inthe proper format and medium at the righttime to interested users. (Dippel & House,1969, pp. 5-6).

In planning and budgeting information systems which givegreat attention to specific Aggregations of data, however,the functions of organization, manipulation, and calcula-tion must include such extensive filtering of data thatnot all data are passed on. These systems may also in-clude various aggregation routines involving crosswalkprocedures between data structures. But because thisprocess merely defines, collects, and transmits data, inour view it is not an MIS. Authentic management infor-mation systems are directed toward the accomplishment ofspecific tasks or the support of specific decisions orkinds of decisions. These are systems that are obviouslyconstrained, therefore; by the responsibilities andfunctions which are assigned to officials and agencies.

Another'important consideration is that MISs arenot comprehensive, nor are they the total integration ofall organizational subsystems. In any complex organiza-tion, whether public or private, the range of organize-

4 228

tional functions is simply too great for any single MISdesigner to have command of the information needs ofadministrators or managers for the full range of decisionsto be made. Resorting to the use of a sufficiently largestaff of diverse functional experts presents severe coor-dination problems, and as Dearden (1972) pointed out,"If any of.the MIS people are competent to tell the func-tional experts what [they need], they should be in the

.

functional area" (p. 96). In short, comprehensive manage-ment information systems are a mirage because no complexorganization has or would tolerate an all-powerful, all-knowing central management. Real-world management infor-mation systems are limited in scope, and provide particulardecisionmaking points within an organization with limitedsets of homogeneous information.

Further, an MIS is not merely computer-based activity.In the state budgeting process, an MIS may not even re-

. quire the application of computers and automated dataprocessing systems. As larger amounts of data are reported,some use of automated data processing may facilitate datahandling and analysis. The development and review ofhigher education budgets, however, do not generally re-quire quick retrieval of data, and thus on-line systemsdo not have a high priority. Some states have implementedautomated budget data systems which tabulate state agencyactions and recommendations on budget totals, but thesesystems are used as record-keeping devices and not fordata submission.

Systematic efforts to gather and report informationconstitute a notable development for the state-level admin-istration of higher education. But the most importantachievements in automated management information systemsin higher education are most likely to be at the institu-tional and operating levels--in admissions, purchasing,libraries, and other business operations. With respect tobudgeting, the most significant developments regardinginformation will lie, with few exceptions, not in theimplementation of automated data-processing technology,but in attempts to refine and use the information pro-vided by improved information gathering and reportingprocedures.

4 329

3.Information and Analysis Development-

in State Agencies: An Overview

Most state budget review agencies examined in thecourse of this study indicated that they had certain in-formation deficiencies. Most identified the difficultyof getting adequate information for conducting a satis-factory review of institutional budget submissions as asignificant problem, but few considered this the mostcritical issue they faced in recent budget cycles. Otherconcerns, primarily the highly constrained resources ofmost state governments, have extremely high saliency atthis particular time, and in addition, most state agencieshave limited capacities to devote to information gather-ing and analysis.

The information gathered by state agencies,except perhaps for state higher education agencies,

appears to be specifically addressed to the activitiesand functions they perform. Because agencies usuallycannot afford the luxury of maintaining a comprehensiveinformation system and the associated automated dataprocessing resources, such activities as budget develop-ment and review rely on a virtually independent informa7tion gathering and distribution network. The end resultis that budget requests and the entire process of revieware largely self-contained. Budget request documentsand supporting information form a single package. Somenew information may be injected from time to time duringthe course of hearings and negotiations, but for themost part the information base for analysis and reviewis set in the call for budgets, sdbsequent instructions,and the submitted requests. Information for use during

30

4 4

budget execution may require separate submissions of in-formation, but it remains essentially isolated from thebudget development process. The use of automated systemsfor submission of information is extremely limited,although it is becoming quite common for the reviewprocess-within individual state agencies to involvemachine-readable records and automated data processingin recording the changes and recommendations over thecourse of that agency's budget review.

-Significant exceptions to these generalizations-will--be pointed out during the course of the report. Thegeneralizations made above must also be qualified becausethey were formulated from evidence gathered at one par-ticular point in timethe year 1974 and the review ofthe fiscal 1974-1975 budget then in progress. At thepresent time, these same agencies are working on their1976-1977 budgets, ind in most instances two additionalbudget cycles have passed since our review. There also areindications that many states recently have become sub-stantially more involved in statewide inforniation collec-tion and quantitative analysis of institutional budgetrequests. _

Generalizations about administrative activities inthe 50 states will almost always be wrong because of thesubtle distinctions that slip through anything but a de-tailed analysis and description, and yet they may also beright because at .least one state will be doing the exactopposite of another. Furthermore, in approaching overalltrends in information use in terms of'the practices ofspecific types of agencies, there is always the possi-bility that any description will fall short of completeaccuracy because the roles of executive, legislative,and higher education agencies vary so widely from stateto state. It is also impossible to divorce informationand analysis of budgets entirely from agency activitiesin other aspects of budgetmaking. The use of specialstudy commissions and task forces, and the developmentof new categories for appropriations in the budget bill,are clearly substitutes for reforms in the handling ofinformation because often these procedures produce thesame results that can be achieved through the routine

,

31

4

gathering of more information and the application of newforis of analysis. However, some consideration of theoverall norms of activity in regard to information arein order as a basis for considering more specificactivities.

Accompanying the vast differences between statehigher education governance structures and proceduresare very different general attitudes toward informationcollection and disclosure at the state level, which pro--duce-very different information-environments. In somestates, for example, salaries of public officials, in-cluding those of university presidents, are fairly wide-spread knowledge and may be the subject of regular publicattention in relation to either general or specific fiscalissues; in other states, such disclosures are not generallymade. In one state, salaries of public university ;presidents

and legislative staff directors were neither generalpublic knowledge nor made available to researchers forthis study.

Personnel systems are the source of other variationsin the kind of information available at the state level.In a few states (Texas and Virginia, for example),personnel records were maintained at the state level,and detailed information on individual faculty memberswere made available to state agencies, although thedata supplied seemed to play very little role, if any,in the budget formulation pro-ess. In other states,the mere suggestion of such a file at the state levelwould have been unthinkable. We mention these differencesnot to suggest approval or disapproval of one practiceover the other, but rather to illustrate the wide vari-ationstin what different states consider the properprovince of state agencies in maintaining and providingaccess to information files.

EXECUTIVE BUDGET AGENCIES

Although all state agencies may approve the formand substance of budget instructions, the executivebudget office is usually the issuing agency, and it

432