New Angel/Angle in Architectural Research

-

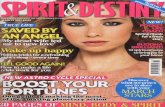

Upload

tom-cheetham -

Category

Documents

-

view

105 -

download

1

description

Transcript of New Angel/Angle in Architectural Research

A New Angel/Angle in Architectural Research: The Ideas of Demonstration

MARCO FRASCARI, University ofPennsylvania

Based on a research agenda monopolized by a theory of concept embodied in normative prescriptions, present "official" researches in architecture are an outcome of the search for an anthological knowledge, a gathering of data that contributes to make buildings safe and durable but lacking the human quality of imagination. Seeing the imaginal dimension as the core of the profession, I present an alternative research in architecture based on a theory of image in this paper. This theory, which stresses the role of demonstration in architec- tural production, is based on the merging of symbolic and instrumental images. The aim suggested for future architectural research is to produce information, new "angelic standards," regarding the nature of architectural demonstrations. The images necessary for these demonstrations are in an amazing thesaurus, a meandered storehouse of monstrous, non-normative technological images that are played in architectural projects, but not properly declared.

"by a commodius vicus ofrecirculation. "'

Vico's Angular View

IN CONSOLIDATION OF HIS OWN THEORY OF IMAGE CONSTRUCTION,

Giambattista Vico, a Neapolitan philosopher of the first half of the

eighteenth century, established a contrast between intelligible univer- sals (universali intellegibili) and imaginative universals (universali fantastici) in determining the aim of a new "scientific" research.2 By questioning of the aridity of the "rationality" of Cartesian thinking he

promoted a "mental glossary of images," a thesaurus of intelligible universals embodied in meaningful theoretical images.3 Considering human institutions as the only possible source of human knowledge, the Neapolitan philosopher developed a new science, the science of

imagination. The search for intelligible universals is described by Vico as the product of a rational, but soporific mind (the French: esprit), whereas the search for imaginative universals is seen as an outcome of a productive poetic mind (the Italian: ingegno).

This does not guarantee against a production of trivial designs. Trivial architecture can be only appropriated touristically. As Walter

Benjamin suggested in his discussion of the role of a work of art in the

age of mechanical reproduction, architecture is appropriated in a two- fold manner: by touch (use) and by vision (perception). On the one hand, there is the strictly visual appropriation of architecture, done by tourists in attentive concentration, standing in front of famous build-

ings. This is trivial appropriation, mostly based on the banality of a criticism that rests on intelligible universals. On the other hand, there are those who appropriate architecture in a tactile fashion, by habit and often in a state of distraction. Benjamin argues that the distracted manner of appropriation is the most suggestive for architectural per- ception, since habits "determine to a large extent even optical recep- tion" that can even acquire "canonical value."4

The aim of this paper is to suggest a possible critical approach to architectural research that is a product of imaginative universals. This research agenda is founded on a theory of image. The theory of image construction, which proposes an understanding of architecture as a system of a representational knowledge, emerges from a techno- logical understanding of images. In common language, technology and its derivative words (technical, technique) have lost the original meaning embodied in the Greek word techne, and they are under- stood only as instrumental in nature. The essence of techne is by no means technological.5 Techne belongs to the notion of poiesis, which reveals or discloses aletheia, the truth, and goes hand in hand with epistime or scientia. A technological image is a reproduction in the mind of a sensation produced by a perception emerging from a criti- cal system, which does not separate instrumental from symbolic rep- resentations.6 This is a critical procedure that deals with an imaginative research based on "recollective universals which generate philosophical understanding from the image, not from a rational category."7 Buildings that result from the application of this proce- dure are safe and durable artifacts. The qualities of these buildings are given in their own ontological dimensions, i.e., they are non-trivial buildings.

In connection with his theory of image construction, Vico also advocates the establishing of a "mental vocabulary of images."8 The title I selected for this paper contains in itself a verbal image that be- longs to this Viconian mental vocabulary. This image intends to make clear the agenda of architectural research I am proposing: a research that aims to produce imaginative, rather than normative, data. The selected image results from a chiasma of the instrumental representa- tion "angle" with the symbolic representation "angel."9 The two terms-ang[e]le and angel[e] -share a possible common etymologi- cal root. Suggesting the procedure for finding guidance in the stars, this chiasmatic idiom evolved from the language used by the early Mediterranean sailors. The imagining of angels, guiding essences, was a way of finding the angles necessary to determine the direction for reaching land safely. In architecture this traditional chiasma of angels and angles is recorded-in an oblique way-by Vitruvius. In his ex- planation of the planning of the angles of cities, Vitruvius cites as an example the Tower of Winds in Athens.I? This Hellenistic edifice in- corporates both representations of the winds as figures of angels and as the angles of the direction.1 Such an etymological explanation be- longs to the realm of necessary fables, which are associations of imagi- native class concepts (Vico's generifantastic) by which it is possible to produce significant artifacts; they are the verbal translation of the event taking place in the mundus imaginalis (imaginal world), a realm of angelic beings or images that provides symbolic grounding for our

I1 Frascari

Tower of the Winds, Athens, reconstruction. (Author.)

physical reality. Lying between the intelligible and the realm of sen- sible things, the mundus imaginalis has been presented to us by the

great French Islamic scholar Henry Corbin (1903-1978). Corbin

uses the adjective "imaginal" to distinguish productive imagination from the "imaginary," the fictitious and unreal vision.

Angels are not things but are like the thing itself. Massimo Cacciari has pointed out that "only the angel free from demonic des-

tiny poses the problem of representation.'2 Angels have the consistency

of the thing, since symbolic primacy. From this angelic

point of view, it is then possible to state:

In architecture each angle is an angel.

The fruitful power of the angelic image is demonstrated by the

linguistic growth of the designation of the angular image contained in the world "temple," which presents us with the "doubt" of the angel of time.

The basic word temeyos (tempus), templum signified nothing other than bisection, intersection: according to the terminology of later carpenters two crossing rafters or beams still constituted a templumr; thence the signification of the space thus divided was a natural development; in tempus the quarter of the heavens

L __ -- SX ... __.2 _

Tower of the Winds, Athens, reconstruction. (Author.)

physical reality. Lying between the intelligible and the realm of sen-

sible things, the east) passed imaginalis has been presenteday (e.g., to us by themorn-

ing) and thenc scholar Henry Corbin (1903-1978). Corbin

uses the adjective "imaginal" to distinguish productive imagination from the "imaginary," the fictitious and unreal vision.

Angels are not things but are like the thing itself. Massimo Cacciari has pointed out that "only the angel free from demonic des- tiny poses the problem of representation.]2 Angels have the consistency of the thing, since they have the symbolic primacy. From this angelic point of view, it is then possible to state:

In architecture each angle is an angel.

The fruitful power of the angelic image is demonstrated by the linguistic growth of the designation of the angular image contained in the world "temple," which presents us with the "doubt" of the angel of time.

The basic word temeyos (tempus), templum signified nothing other than bisection, intersection: according to the terminology of later carpenters two crossing rafters or beams still constituted a templum; thence the signification of the space thus divided was a natural development; in tempus the quarter of the heavens (e.g., the east) passed into the time of the day (e.g., the morn- ing) and thence into time in general.'3

Linguistic tracings are verbal expression of groups of imagina- tive class concepts (Vico's generifantasticl) that are the technological measures for the production of significant artifacts. These technologi- cal measures are based on images that result from a symbolic constru-

ing of a construction. In other words, the technological measure, or technometry, of the technological image of the angel/angle is the symbolic representation that originates in the instrumental represen- tation of the use of angles for determining directions.'4 An instance of the fruitful power of angles in setting human meaning was singled out by Vico in discussing "ingenuity" in his analysis of the ancient wis- dom of the Italians.'5

Ingenuity is the power of connecting separate and diverse ele- ments. In Latin it is described as acutum (acute) or obtusum (obtuse), terms which belong to geometry, because when it is acute it penetrates [things] more quickly and links different ele- ments more closely, analogous to the connection of two lines at a point with less than a right angle [between them], whereas when it is obtuse it approaches things more slowly and leaves different elements more remote from their foundation, analo-

gous to the connection of two lines at a point with more than a

right angle [between them].16

This angular interpretation of intellectual procedures is a genu- ine generative procedure that recognizes the power of ingenious im-

ages in the production of human thought. A thought begins in

genuflecting, the bending of the knees, an angle that is fundamental for human generation. In primitive society the mothers deliver babies by gently kneeling and gentile fathers in a similar fashion recognize their genuine offspring by accepting them on their knees, the recog- nized place of their generative power.'7 In an ingenious but ingenuous manner the same concept has been developed by Carlo Scarpa in a se-

quence of drawings for the design of a decoration for the chapel of the Brion Cemetery, in San Vito d'Altivole. A kneeling angel has been

designed for the north corner (It: angolo) of the building. In the present status of architectural production, envisioning

negates construction, especially in the understanding of the transla- tion that occurs between drawing and building. The past interpreta- tion of this translation was that an architectural drawing is a graphic projection of a deceased, or existing, or future building. The present condition of the phenomenon is that the building is a translation in built form of"pre-posterus" drawings. In the past the symbolic and the instrumental representation were unified in the building; draw-

ings were solely instrumental representations-their translation was also a transmutation through construction. In the present reality, however, the union of the symbolic and instrumental representation in the building depends on their presence and union in the drawing.

November 1990 JAE 44/1 1 2

' ? .I " ! - ..: '-- A

?*'* .. ...!' ^ 't^ -^.. -: .. - - -,., : 7::'* I

Carlo Scarpa, Study for the kneeling angel on the north corner (It: angolo) of the chapel within the Brion Cemetery, in San Vito D'Altivole Treviso. (Courtesy Scarpa archives.)

The transmutation should take place in the drawings; angles should

transfigure themselves into angels. My proposal is that a productive approach to critical research in

architecture is possible only if the complexity of the technological im-

age is preserved. This is possible only through a radical change in our

understanding of the role of drawings in architecture. Drawings must become technographies. These are graphic representations analo-

gously related to the built world through a corporeal dimension and

embodying in themselves the Janus-like presence of technology in ar- chitecture, where the techne of logos cannot be separated from the logos of techne. As specific acts of demonstration, these technographies are based on an architectural encyclopedia, which is a thesaurus of tech-

nological images. An understanding of the present "doubt" of representation in

architecture can be gained by analyzing the idea of "future" inserted into the notion of architectural project. By architectural project I mean a productive construing that must evolve from mere profes- sional service toward becoming a critical tool for the shaping of hu- man inhabiting. This productive approach is achievable only if the

complexity of the angelic image is preserved and this is possible only through a radical change of our understanding of the role of drawings in architecture. Drawings must be conceived within an angelic gaze as

buildings are built within the same acute gaze. Drawings are graphic rep- resentations analogously related to the built world through corporeal di-

mensions and embodying in themselves the chiasma of construing and constructing. Drawings are specific acts of demonstration belonging to an architectural encyclopedia, which is a thesaurus ofangelic images. How- ever, as Sartre had pointed out, "it is one thing... to apprehend di- rectly an image as an image, and another thing to shape ideas regarding the nature of images in general."'8 In architectural research the use of intelligible universals has produced catalogues, or building codes, or dictionaries, whereas the use of imaginative universals has produced treatises, or discourses, or encyclopedias.'9

Dictionaries and catalogues are assemblages of definitions of ar- chitectural parts, elements, and artifacts, based on a model of defini- tion structured by genera, species, and differentiae, generally known as the Porphyrian tree. This procedure generates univocal meaning and attempts to restrict any interpretative processes. Treatises and en- cyclopedias are presentations of the parts of architecture through a system that can be equated to a net, and works like a Roget's Thesau- rus.20 A Rogets is a practical book and is not concerned with the idea of classifying (i.e., with a set of orderly listed definitions), but rather, as the title page states, it is "Arranged so as to Facilitate the Expression of Ideas and Assist... in Composition." The purpose is to generate an understanding of the complexity of meanings through interlocked clusters of words and terms. It is a difficult book to use; the foreword to an alphabetized version states that "a frustrated writer seeking help in Roget's finds himself wandering in a [labyrinth] where each turn of thought promises to produce the desired synonym."21

The Maze of the Image

Now to be coherent with the angelic principles underlying this paper let me generate an architectural image to explain the difference be- tween dictionary and thesaurus and to bring back to our architectural understanding the notion that "the thing itself and the name ... form a symbol."22 A dictionary is structured as a maze, whereas a thesaurus is organized like a meander. On the one hand, mazes-a Manneristic invention-display choices between paths and sometimes paths are dead-ends. The only possible path within a maze can be easily repre- sented by the graphic notation called a "tree." In a maze Ariadne's thread is necessary, or else life is spent in repeating the same moves. No monsters are necessary in this labyrinth. A maze is in itself the Minotaur. In other words, the Minotaur is the architectural researcher's trial-and-error process. On the other hand, a meander is a labyrinth that works as a net. In a net every point is connected with every other point. These connections are not designed but they are designable.23 Furthermore, meanders are full of monsters. These Minotaurs-monsters conceived by inconceivable unions-demon-

1 3 Frascari

strate the possibility of union between different kind of realities. They are not abnormalities but rather extraordinary phenomena that indi- cate the way for architecture, a way by which designs and drawings are not separate entities but symbols. "Monster" is a derivation of the Latin verb monstrare, to show or to point out, which in itself derives from the verb moneo, to make to think. In other words, these mon- sters show how to bring together a constructing with a construing, through a demonstration, rather than through a preposterous pre- scription, i.e., design and construction drawings based on merely graphic conventions.

The names listed in the dictionaries are the omona, "pure names which mortals laid down believing them to be true."24 In ver- bal utterances, omona are used as graphic conventions, as templates and graphic standards are used in design utterances. As an instrumen- tal presence in architectural projects, a template "is nothing other than the representation of the entity in the doxa of mortals."25 From a critical point of view, names (omona) and templates belong to the realm of opinion to which the truly real thing escapes. Names and templates "are in no case stable. Nothing prevents the things that are now called round from being called straight and the straight round."26 The outcome of this instability is that "the representation by means of the name does not give the thing itself but the doxa around the thing."27 A public relation statement made by Arquitectonica, a fashionable architectural firm in Miami, is an affirmation of the power of an architectural doxa. Drawn within the Cartesian look of isometric drawings, Arquitectonica designs are pro- duced in a contrived style generated by the use of Russian Constructivist templates mixed with the templates of successful speculative developers. These designs are objectlike buildings that can be located anywhere at any time, although a carefully crafted utter- ance of public relation affirms that

Arquitectonica's approach to design is both modern and con- textual. The designs seek conceptual clarity and freedom of the limitation of style. Architecture is conceived to capture the in- tangible spirit of place and time by recognizing place and time as two equally important elements of context.28

This is a clear case where the steps in an architectural project are solely a matter of translation; drawings are translated into built forms, then buildings are translated into verbal forms: as an old Ital- ian saying states, traduttori traditori (traitors, these translators).

In the postmodern status of architectural production the visible construing negates construction. Although I do not agree with these postmodern means of production, I must admit that they are the symptomatic results of an aporia about the nature of drawings, espe- cially in the understanding of the transmutation that occurs between

drawing and building. The classical interpretation of this transmuta- tion is that an architectural drawing is a graphic projection of a past, or existing, or future building. After the architecture of the First Moderns,29 building became the representation of the drawings that preceded it.30 In the classical tradition, symbolic and instrumental representations were unified in the building, whereas the drawings were seen as merely instrumental representations. In the present real- ity, however, their union in the building depends on their presence and union in the drawings.

The nature of this traditional interpretation can be easily pre- sented as making reference to the myths of the origin of drawing and construction of the Temple. For the construction of the Temple on Mount Sinai, Jehovah, the divine architect, shows Moses, the mortal builder, the designs of the future sanctuary that he has to build for him and warns him:

and look thou make them after their patterns which was shew thee in the mount.31

The myth of the origin of drawing, as it was handed down to posterity by Pliny the Elder, tells us the story of Diboutades tracing the shadow of her departing lovers on a wall. From the point of view of these traditional interpretations, drawings are not more than jigs and templates; they are an intermediary step of a design projection. Within this traditional interpretation the criticisms of the dominance of drawings developed by Leon Battista Alberti and Adolf Loos are understandable, since the drawings they are criticizing are objects in themselves, and do not work as templates or jigs.

In the new interpretation of the role of drawings, drawings are not objects in themselves, but they become demonstrations of archi- tecture. They are the documents out of which the builders, the build- ing management, and all of the other trades related to the making of buildings derive their understanding for the making of the templates and jigs necessary for the construction. These demonstrations are monsters within the labyrinth of the building trade. They are the multilayered structure of the meaning of an angelic image.

Drawings must demonstrate the angelic image. Displayed as whole, the palimpsest of the angelic image is the matrix of the repre- sentational theories of the constructed world. This palimpsest is an act of projection, a casting forward becoming a point of projection itself. The origin of drawings as angelic demonstration of construction is embodied in Vitruvius's description of the concept of arrangement:

arrangement is the fit assemblage of details and arising from this assemblage, the elegant construction (operis) of the work and its ornament (figurae) along with a certain quality.32

Vitruvius listed three kinds of arrangement, that, he pointed

November 1990 JAE 44/1 1 4

out, are called ideai by the Greeks. The first idea is ichnography, which depends on a competent use of compass and ruler; the second is orthography, which is the vertical presentation of a future building; the third is scenography, which is the presentation of the front and the side with all the lines resting in the center of a circle. The three kinds of idea are born from the considering (cogitatio) of all the parts and are found (inventio reperta) through a techne. Thus, the making of ar- chitectural drawings is based on cognitive representations or known objectivity. A circular procedure is involved here: the understanding of the part is achieved through the consideration of considering the whole and the understanding of the whole is achieved through the consideration of the parts.

The first angelic image required by any architectural project is

ichnography, and it is ontologically the demonstration of a future edifice plan with lines, ropes, and boards on the grounds of the se- lected site. In his commentary on the first Italian translation of Vitruvius's treatise, Cesare Cesariano, discussing the laying out of a plan, talks about the walking of the compass (ilpazzezare del circino).33 For Cesariano, the drawing of the plan is a graphic demon- stration analogous to the demonstration of the future construction given by the architect to the builder when he is pacing through the site pointing out the features of the building. An instance of this de- monstrative pacing is the architect stepping into the mud to demon- strate to the builder the corners (It: angoli) of the building, the location of the "keystones" for the construction, that is, the "corner- stones" (It: pietre d'angolo).34 Orthography is the demonstration of how the vertical raising of the building is done. The ontological dem- onstration of it is embodied in the structure of the scaffolding. An

understanding of the procedure of this demonstration can be gained by looking to the brick facade of many medieval constructions that are marked by many holes. The holes are the signs that allow us to re- construct how the scaffolding interacted with the edifice during its construction, by a mirror experience, an acute reflection. Scenogra- phy is the most difficult item to explain, because of the misleading notion generated by an homophononous term that means "stage de- sign." As a result, it has mostly been interpreted as perspective. In his commentary Daniele Barbaro, the most intellectually powerful among the patrons of Palladio, calls this third kind of arrangement profilo, a cut feature showing the building during its construction.35

From this third idea, called scenography (sciografia), from which great utility is derived, because through the description in the profile we understand the thickness of walls, the projec- tions of every element (membro), and in this the architect is like a physician who demonstrates all the interior and exterior parts of works.36

A profile is the demonstration of the stereotomy of the building parts, an anatomical representation of building elements. Through projections, stereotomy gives the correct angles of the faces of the stones to be assembled for the construction of the edifice. As Kenneth Frampton has pointed out, stereotomy, a Gothic demonstration de- vised to avoid the labor generated by the several presentings of the stone required for cutting it properly, is the beginning of the idea of "project."37

Architectural Demonstrations

A building that does not weather well is not perfect. A drawing that does not weather well is not perfect. A technography is a palimpsest generated by a weathering of three relationships in graphic demon- stration. Having analyzed the ontological dimensions of drawings in the previous parts, I ask the rhetorical question: what should architect's drawings demonstrate? The answer: the technological im- age. This image should be read as a palimpsest displaying three over- lapping relationships: (1) between a real architectural artifact and a reflected or projected image of it; (2) between a real artifact and the instrumental image in the mind of someone involved in a building trade related with its construction; and (3) between the instrumental image devised by.the architect and the symbolic image that rests in the collective memory of a culture. This technological image displayed as a whole is the matrix of the representational theories of the making of the constructed world. This palimpsest is a technography, an act of

projection: a casting forward becoming a point of projection itself.38 This palimpsest is Joyce's Geomater, where the projection is the pro- jector, the measuring is the matrix of the generative power of imagi- nation.39

The first relationship composing the triad of a technography is the direct project, which by analogy can be called the orthography of the project. This is based on the art of the measuring and surveying of edifices and building details. This is the translation of the built world in a world of drawings. It is not what has been labeled an "architec- ture of precedent"; it is rather the recognition of projects as projectors. Architectural surveys are the projections of projects. From this point of view, architectural research is a scientific search within the art of in- vention. This is the necessary preparation for setting a thesaurus of ar- chitecture.

The second relationship composing a technography is a project of negotiation. This is the projection taking place during the transla- tion of architecture from a drawing to the built world, in such a way that the building is a correct and congruent representation of the project that precedes it. It is the transformation of the reality of a

1 5 Frascari

drawing in the reality of construction, the construing of future or past construction within a technological reality.

The third relationship within the palimpsest of technography is the one between instrumental representation and symbolic represen- tation. Existing in the built work as a corporeal relationship between measures and dimensions, the measure of the immeasurable is a ma-

nipulation of images of the customary. This is perfection that is trans- lated into drawings that are then manipulated in designs. Perfection conceals its presence in the inconspicuousness of the customary. A

perfect building refuses to praise itself and put shame on the other

buildings for being inadequate. A perfect building is not for the atten- tive concentration of the tourist gaze but to be understood and appre- ciated in a habitual manner. For this reason perfect buildings are

always discreet, and one must look at least twice, if not more, before

perfect architecture can be recognized. This architecture is mastered by habits, i.e., living and graphic habits. The graphic results are then translated in buildings.

Through these two transformations, then, the instrumental and symbolic representations consubstantiate in a building. The com-

pleted technography becomes a chiasmatic monster, a demonstration of a future building grounded in past perceptions. Technographies are

enigmas that can be solved only by construction. Hannes B6hringer states that "perfection creates itself," consequently the only proper way to create a perfect building is to begin the design by copying a

perfect building.40 Mimesis is the process for achieving perfect archi- tecture. This process does not imitate, but copies. It copies the proce- dure of production rather than the product. A building must adapt to its world by combining the whole with the part-its details are like the perfect monads. The art of architecture thus consists in rescuing the ideal of perfection from the past and in locating it as a discreet

presence in the present, making perfection present in the art of living well, which is our manner of making ourselves at home in this world.

A sequence of drawings and a collection of aphorisms by Massimo Scolari, an architect who paints and teaches drawing and

survey at the IUAV in Venice, can help further our understanding of the nature of technography in the light of the aporie of architectural

drawings, and the idea of the enigma solved in the construction. These drawings were done for the construction of one of the twenty facades designed by fashionable architects and constituting the acme of the architectural section of the 1980 Venice Biennale, which sanc- tioned the official presence of postmodernity in architecture. The drawing that generated the facade is entitled A Door for a Sea Town, though in truth it is more than a drawing; it is an oil painting. The

painting shows a gate inserted in a rock barrier that separates the sea from a lagoon. The reference to Venice is clear. The gate is repre- sented as masonry construction with impossible cantilevers. The

Massimo Scolari, A gate for a Sea[seel-City. (Courtesy of Massimo

Scolari.)

November 1990 JAE 44/1 1 8

a ?

p:N rY

-

Massimo Scolari, Facade for the Biennale, the Presence of the Past, Corderie dell'Arsenale, Venice. (Courtesy of Massimo Scolari.)

painting is based on a multiple stations perspective, and the gate is demonstrated through the use of an inverted central perspective whereby the front of the figure represented is smaller than the back of it.

Two sets of orthogonal drawings-one rendered and one mea- sured-translate the gate in the reality of its site, a bay in the colon- nade of the Corderie of the Arsenale in Venice, where the Biennale exhibition took place. The translation, however, does not follow the construction rules of an inverted perspective, but rather surveys the

drawing, construing it, since it is in itself a congruent orthogonal rep- resentation of the gate. A new imagining of the gate results from a ne-

gotiation and therefore solves the problem stated by Scolari in one of his aphorisms.

The imagining is always more perfect than construction since the latter imitates the former, there is not an imitation without some omissions.41

I

Iii

i

I1

Massimo Scolari, Drawings for the Facade for the Biennale, the Presence of the Past, Corderie dell'Arsenale, Venice. (Courtesy of Massimo Scolari.)

To conclude this proposal for the use of imaginative universals rather than intelligible universals in the setting an agenda for architec- tural research, it is necessary to recall that it is essential that the objects about architecture should not be given to public knowledge in a rigid, finished state, in their naked "as suchness." Rather, they should be presented as demonstrations in such a way that each angle should be dressed up as an angel. The information regarding the architectural demonstration should be preserved in a thesaurus, a meandered store- house of monstrous non-normative technological images-images that are played in the world of construction, but not necessarily explained.42

Notes

1. James Joyce, Finnegans Wake (Viking Press, New York, 1939), p. 3.

2. Vico presented his proposal for research in a work entitled La Scienza Nuova; the third version was published posthumously in 1744. The rhetorical question for any reader of The New Science is: what is the subject of this science? Giambattista Vico, The New Sci-

1 7 Frascari

F'

i .* :B?? ."' 1 i

'I r i!li .X"'h :i 1 .C C? I ???-*

s II H .r

:::, Li r*

I

.....,::,,~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~...... ...........~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~i.H.

... . ... ... ..: :

i!??~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~. .....

............ ....:":: :ii~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~iii8i:i:: ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ . .......

... ... .. ... .. .............. ... ... . . .... ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~isinis:i:

?;::~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~?? ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ .....

...... ... ... ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~~:lnr ????????:?:;:L;;.

ence (Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1968); see also Leon Pompa, Vico, Selected Writings (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1982).

3. Vico, I, 9; #473-482. 4. Walter Benjamin, "The Work of Art in the Age of Me-

chanical Reproduction," Illuminations (Harcourt, New York, 1969), p. 240.

5. When a translator of a Greek text encounters the word techne, it is almost automatically translated with the Latinate word "art," following a process of simplification begun by the Romans with their wholesale, uncontrolled borrowing of Greek culture, and the consequent need of finding equivalent Latin words for Greek terms. Techne is a strange word. It has always been difficult to define its se- mantic realm, and it becomes more complicated when it is coupled with the word logos. The changes in meaning, at various times and in different places, of the work "technology" are thus quite astonishing. The most surprising occurred during the Enlightenment, when the components of the word were reversed. Dividing "technology" into its original components of techne and logos, one can set up a mirror re- lationship between the techne of logos and the logos of techne. At the time of the Enlightenment, the rhetorical techne of logos was replaced by the scientific logos of techne. In architecture, however, this replace- ment did not take place, since technology existed with both forms in chiasmatic presence in the constructed world. Translating this chias- matic presence into a language proper to architecture, we might say that there is no construction without a construing, and no construing without a construction. This is exemplified in the process of the mak- ing of architectural details. A triglyph is the embodiment in stone of a wood technology, which already was the embodiment of a bone tech- nology; see George Hersey, The Lost Meaning of ClassicalArchitecture (MIT Press, Cambridge, 1988). This detailing process is the result of two components. One is predominantly manual and operative, and is based on the logos of the techne (a constructive procedure). The other is mental and reflective, and is based on the techne of the logos (rhetorical procedure). The use of these binomials returns architecture to its original nature as a discipline with a system of knowledge that can then be transferred into the instrumental knowledge necessary to practice construction. The decoration of a Doric temple is a constru- ing in stone of the elements of a wooden building, whereas the con- struing of a cosmological order is constructed in a Renaissance villa. Non-trivial buildings are always devised within this chiasmatic nature. They are thinking machines in which the wood, stone, concrete, metal, mortar, and glass are unified by design into a stereographic multiplicity. See note 14.

6. The binomial of symbolic and instrumental representation

is discussed by Dalibor Vesely, "Architecture and the Conflict of Rep- resentation," ArchitecturalAssociation Files 8 (an. 1985):21-38.

7. Philippe Verene, Vico s Science oflmagination (Cornell Uni- versity Press, Ithaca, 1981), p. 56.

8. Vico, I, 9; #473-482. 9. The proposal presented here should not be construed within

current trends toward obscure mythical approaches, but rather it is conceived within a constructionalist orientation. See Nelson Goodman, Ways of World Making (Hackett, Indianapolis, 1978), p. 1.

10. [Marcus Pollio] Vitruvius, De Architectura, translated by F. Granger (Heinemann, London, 1931), Book: I, vi, 4.

11. This etymology, as any other Viconian etymology, se non e vera, e ben trovata; for a further discussion of the importance of this imaginative dimension of etymology, see the discussion of folk ety- mologies in Ananda Coomaraswamy, "Nirukta=Hermeneia," Meta- physics, ed. R. Lipsey (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1977).

12. Massimo Cacciari, "The Problem of Representation," Recoding Metaphysics, ed. G. Borradori (Northwestern University Press, Evanston, 1988), p. 155, This article is a translation of the first chapter of Massimo Cacciari, L Angelo Necessario (Adelphi, Milan, 1986).

13. G. Usener, quoted by Ernst Cassirer, The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1955), p. 107.

14. Technometry is a word borrowed from the technological language of William Ames, Technography (University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1963); see also my interpretation of the concept: Marco Frascari "Technometry and the Work of Carlo Scarpa and Mario Ridolfi," presented at the ACSA National Conference on Technology, Washington, Dec. 2-3, 1986.

15. Ingenuity translates Vico's ingenium, which is sometimes translated as inventiveness, wit, or genius; in this I am following Pompa's translation (p. 69). See also the discussion developed by Ernesto Grassi on the concept: "Critical Philosophy or Topical Thinking," Gianbattista Vico: An International Symposium, and "The Primacy of Common Sense and Imagination," Social Research 43, 3 (Autumn 1976).

16. Gianbattista Vico, "On the Ancient Wisdom," in Pompa, p. 70.

17. For a discussion of the importance of knees in human un- derstanding, see R.B. Onians The Origin of European Thought (Cam- bridge University Press, Cambridge, 1951), pp. 174-186.

18. Jean-Paul Sartre, The Psychology of Imagination (Washing- ton Square Press, New York, 1968), p. 118.

19. Nota bene. Many treatises are pseudo-treatises. They are

November 1990 JAE 44/1 1 8

nothing other than disguised catalogues. In the same manner, many encyclopedias are nothing other than disguised dictionaries.

20. Here, I mean the traditional version of a thesaurus, not the

contemporary alphabetized versions. 21. Charlton Laird, Foreword to Webster's New World Thesau-

rus (Colins World, n.p., 1971), p. vi. In the citation, I substitute the

original term maze with the word labyrinth, since in this paper, the term maze takes on a very specific meaning.

22. Cacciari, pp. 158-159. 23. This discussion of catalogue and thesaurus, maze and me-

ander is partially derived from Umberto Eco, Semiotics and the Phi-

losophy of Language (Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1984), pp. 80-81. The word meander with this meaning is a "monster" de- vised by Eco himself.

24. Parmenides frag. 8.39, quoted by Cacciari. 25. Cacciari, p. 157. 26. Plato Seventh Letter 343a-b, quoted by Cacciari. 27. Ciacciari, p. 158. 28. From the pamphlet distributed by South Carolina AIA

Chapter for the keynote speakers of 1989 annual meeting; "Speakers," Aquatecture, Spring Convention 1989, leaflet.

29. The reference here is to Joseph Rykwert, The First Modems (MIT Press, Cambridge, 1982).

30. My perception of this "doubt" began with the reading of

Philippe Boudon, "Structure and Signs," Architectural Design Profiles: Viollet-Le-Duc (1980):90-94. Originating his thought through a semiotic analysis of Viollet-Le-Duc's Dictionary, Boudon stated that "the edifice is the representation of the project which preceded it"(p. 91). The fulcrum of Boudon's argument is Viollet-Le-Duc's bold statement that the "execution is the stamp of... conception." In other words, a drawing is a pre-post-erous piece of architecture. The

perception of this aporia can be strengthened by the reading of a short

piece written by Antonio Gramsci, Quaderi dal Carcere. In his writ-

ing, the Italian Marxist philosopher suggests that the work of art of the architect is in the project, not in the building, as the real work of art of the writer is in the manuscript, not in the printed book. A clear

sign of this inverted relationship between drawings and building is that many preservation designs are done, first, on the existing working drawings rather than on the survey of the building.

31. Exodus 25:9, 40. 32. Vitruvius, Book I, ii, 2. 33. Circinus is the Latin name of the nephew of Daedalus, who

was killed by his uncle when the young apprentice gave away the se- cret of the compass, the articulated joint devised by Daedalus to make the dedalions, his wonderful walking statues. Pollione Lucius

Vitruvius, De Architectura Commentato e Affigurato da Cesare Cesariano (Gottardo dal Ponte, Como, 1521).

34. For a discussion of the keystone and cornerstone identity, see Rene Guenon, "La Pietra Angolare," Simboli della Scienza Sacra

(Adelphi, Milan, 1975), pp. 238-250. 35. In the present architectural usage a "profile" is a sectional

elevation of a building. 36. Marcus Vitruvius, I Dieci Libri dell'Architettura di

M. Vitruvio, tradutti e commentati da Monsig. Daniele Barbaro (Marcolini, Venice, 1584), p. 30.

37. Kenneth Frampton, "The Anthropology of Construction," Casabella, 251-252, (an. 1986): 7-9.

38. With the term technography, I am reviving, in anglicized form, tecnografia, a term devised by Lodoli to define a correct use of

representation in the practice of architectural technology. Carlo Lodoli, "Outlines," in Marco Frascari, "Function and Representation in Architecture," Design Methods 19, 1. Technography can be ex-

plained within Ames's technometric framework. Technography, like

calligraphy, belongs to the group of the less dignified, but eminently productive faculties, that are not in themselves unworthy if they are

practiced with natural talent rather than being done "artificially." Ames, Technography, thesis 132. Technography is consequently con- cerned with measuring well (bene metiend) an art that becomes con- crete in another art, namely, doing the work of nature well (ars bene naturandi), a special art that does not enter into any other art-the

counterpart of it is the art of living well (bene viviendi). In bene naturandi the idea is that one produces through an imitation of the act, an analogical procedure, rather than through an imitation of the

object and the art of bene metiendi is the procedure that relates the different parts of a human "physical" work. Ames, Technography, thesis 163.

39. In Joyce's thi(n)[c]k imaginal brew, matrix, mater (mother) and "meter" are unified through their Sanskrit root ma, matr, mean-

ing to measure, See Robert Griffin, "Vico, Joyce and the Matrix of Worldly Apearance," Rivista di Letterature moderne e comparate, XL, 2, n.s. (Apr.-June 1987):5-17.

40. Hannes Bohringer, "Plus Quam Perfectum," Daidalos 31 (Mar. 1989):55.

41. Massimo Scolari, "Considerazioni e aforismi sul disegno," Rassegna9 (1982):85.

42. This updated version of the essay is once more dedicated to the memory of Matteo, a new angel.

1 9 Frascari