Mandala Mapping

-

Upload

nabin-bajracharya -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

1

Transcript of Mandala Mapping

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

1/19

Journalo CulturalGeographySpring/Summ er 2006 23

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

2/19

7 Journal of Cultural Geographysigruficance ofmaps,then, seems to eparticularly in the fact that m apsare stirrogates of space. The usefulness of maps for transmittingconcepts Ues in their portrayal of spatial relatedness, which lies at thecnix of cartography and hum an apprehension. In short, anything thatcan be spatially conceived can be mapped (Robinson and Petchenik1976).Maps are a complex visual text (Bender et al. 2004, 1) thatportrays what the mapmaker wants the viewer to see. By enteringa m ap w e enter the world ofitscreator(s), triggering an interaction w ithour own embedded, culturally contested view. The challenge lies inreflecting upon our understanding of spatially symbolic relationshipsas we try to perceive and evaluate the mapmaker's vision. Theoutcome potentially transforms our perception of the arrangement ofthe seen and tjnseen world and yields a clearer understanding of theimportance of the mind as the seat of perception.

This research explores the spatial mapping function of visualrepresentations in a mandala: a sacred space conceived as acognitive graphic of an area that is seen as becoming real, isvirtually inhabited, and entered into by the observer who thennavigates through it on a mental pilgrimage. Exploration of geo-graphic concepts from the perspective of a Buddhist mandalapermits a fresh rethinking of core underlying assumptions andnew notions of space, place, portrayal, and contestation in bothcartography and religious geography. The latter geographic sub-discipline has shifted from a concern with the impact of religiouspractice on shaping the landscape, especially within Berkeleyancultural geography, to a late twentieth-century interest in the useof space in portrayals of beUef systems (Kong 1990). A particularinterest of contemporary research involves symbols that seek topreserve cultural representations, from graves to special mo unta insand pilgrimage routes (Kong 2001). The role of mandala creation inheightening awareness of Buddhist, and specifically Tibetan, issuesalso will be explored in relation to another recent geographicconcern with contested spaces. One of several groups of Tibetanrefugee monks from monasteries in India created the specificmandala example pictured in this research. Their purpose includespreserving a culture that is endangered in their homeland, butwhich ironically is preserved in the south Asian country where

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

3/19

Ma ndala as Saered Spatial Visualization 7Table 1.

Mandala Types and UsesMedia1) City plan

2) 3 dimensionalsculpture.model3) 2-3 dimensionalon surface (e.g..sand)4) Hanging thangka(painting, print.material)5) Verbalinstructions

OuterConcreteurban form

Art work

Art work

Art work

Nirmanakaya(materialdepiction);guru narrates.observeroutsideaspirant

InnerIdeal recreatedon earthInspirational,didacticInspirational,didacticlr\spirational.didacticSambogakaya(subtlerrepresentation);observer learninglessons inside.guru center guide

SecretMetaphysical mirror,bringing harmonythrough habitationUsed in empow ermentlesson; navigated byinstruction from guruUsed in empow ermentlesson; navigated byinstruction from guruUsed in empow ermentlesson; navigated byinstruction from guruDharmakaya (nondual.indivisible);Guru -observ er-deitymentally mergeentities in center

Source: Co mp iled by author.

visualization that falls into a different category from the currentlycontentious cartographic camps of positivists, realists, postmod-ernists, social theorists, and others. By directing visualization to theinterior spaces of the observer's mind, this device contributes a non-Western perspective on the two-dimensional mapping of physicalspace with its portrayal of metaphysical, multidimensional experi-ential space. In his introduction to an edited volume on imensionsof HumanGeography (1978), Butzer proposed multidimensionalcategorizations of space for geographic research, focusing on spaceas a container of resources, control, social identification, andsymbolicvalue.The mandala enlarges this framew ork by p roposingan instructive space wherein, in this example, the individual canleam how to transcend earthly constraints and ordinary perceptionsin order to realize his/her potential as a more enlightened being.

A mandala depicts and provides a way for humans to reachthe center of the cosmogram by becoming a mirror of the cosmos(Brauen 1997, 21). The observer engages with the mandala on threelevels of meaning generally classified as outer, inner, and secret

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

4/19

7 Journal of Cultural Geog raphywith the central object of bringing about the acquisition of theassociated virtues of wisdom, compassion and healing. To fullyappreciate the nature of the mandala's use as a map the mandalamust be understood as a physically existing entity (most commonly#3 and #4 in Table 1) that metaphorically represents a multidimen-sional space. This type of space can range from a tangible worldportrayed in the common road m ap to a space visualized as a three-dimensional imaginary, to a purely metaphysical mind-trainingexercise. The practitioner peels back the layers of the extemal-physical-tangible along a guided navigated journey through themandala toward realization of an internal harmonious integration.The mandala typically serves as a physical spatial metaphor thatcaptures and contains a metaphysical space. This mapped meta-physical space includes a directional orientation of axially-orientedlayers ranging from bottom to top and outer to central points.

The origin of the mandala has earthly roots in severalcontinents, Cretan labyrinths of the fifth century BCE, like theirIndian counterparts portraying cave mazes, included dead endsrather than a plotted path toward the center, where the Minotaurawaited its fate at the hands of Theseus (Zehnacker 2004), Mazemaps were also associated with the windit^g pilgrimage route fromEurope to Jerusalem, with the holy city placed in the map's centeras targeted destination. In the Hindu tradition from which Bud-dhism sprung, yantras consist of diagrammatic objects composedto aid in meditation, and tend to be smaller than mandalas. Yogiis the Sanskrit name for a meditator who particularly seeks to joinhis/her individual mind in union with that of ultimate reality,represented by the protective deity which occasionally resided(metaphysically) in the middle of the yantra, similar to themandala's function (Pott 1966). The American Museum of NaturalHistory labels yantras unearthed at ancient historical building sitesas devices used to attract Divine Energy of a Deity into a sacredspace (Meister 2003,258).

An archetypal yantra form features a large circle with thecircumference touching, or close to, a surrounding square, andseveral square boxes or triangles inside the circle. Similar to

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

5/19

Mandala as Sacred Spatial Visualization 71986). It is also seen in two-dimensional square platforms thatinclude motifs such as a central deity surrounded by geometricfigures, or an enclosure with a central T-shaped opening at thecardinal po ints, encircled by lotus blossom s Brauen 1997). Yantrasare visually projected in three-dimensional space as residences fora deityanother conceit employed in mandalas. Hindu mandalas,created to mark auspicious occasions such as birth and marriage,differ from Buddhist ones on doctrinal issues. The central valuesportrayed do not include distinctly Buddhist Mahayana virtuessuch as altruism {bodhicitta and compassion. Yantras celebratingsecular landmark events are produced and used by non-ordainedindividuals. Mandalas serve as a microcosmic configuration withmore detailed spiritual symbols {Pott 1966).

Venturing into visual portrayals of places not on the face ofthe earthof imaginative, internally-conjured realms that asserta greater validity than our concrete measurable perceptionsreclaims such spaces within the domain of geography and enlargesour geographic conceptual understanding of the function of visualportrayal of place {Harmon 2004). We sharpen our vision by seeingworlds other than those we are accustomed to viewing, and seek-ing to understand them as seen through the eyes of their creators.Travelers do this by going to other places on the earth, or viewingdepictions of such places. Mandalas are distinctive features ofreligious art throughout the Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist world,which extends from Central Asia through India to China, Korea,Japan, and Southeast Asia. As symbols they embody a uniqueconception of crucial aspects of their ancient parental culture. Thisexamination focuses principally on the Tibetan understanding,construction and use of mandalas, since it constitutes the mostwidely utilized contemporary form of traditional mandala aspreserved since their introduction into Tibet as Indian iconic formsin the eleventh century. The next section journeys into a typicalpalace mandala, delineating the main features of this archetypeas constructed by a contemporary group of traveling monks.The generalized interpretations in the next section are based oninterviews with various monksincluding several with theBuddhist equivalent of a doctoral degreewho have participated

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

6/19

7 Journal of Cultural Geog raphy

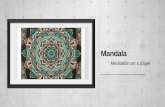

Fig.1.Completed Mandala. Photo courtesy of Drepung Loseling Instituteexperience. Figure 1 portrays a standard palace-type mandala,representing the dwelling place of the deity symbolized in thecenter (Leidy 2000). Although mandalas vary in details such as theentities portrayed in the center circle and the symbols in the areaimm ediately outside the outer square, this example contains severalexemplary and key components that occur in high symbolicfrequency Various numerical sets are used to echo and containother values that occur in the same number (three of this, four ofthat), although the underlying goal lies in attaining the realizationthat there are no separations, since all phenom ena exist in one

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

7/19

Mandala as Sacred Spatial Visualization 77veloping the attributes portrayed, for example, the three steps ofwisdom (sun symbol), bodhidtta (bliss of compassion, moonsymbol), and mind of renunciation (lotus symbol) by followingthe path indicated from outer rim to inner circle and learning thelessons contained within.Three concentric rings, representing the three pillars to the stateof enlightenment, form the border of the man dala example in Figure1. The outermost burn ing fire ring band represents the wisdom ofcomplete emptiness (seeing things as existing only in relation toeach other, not independently). The next ring, festooned with v jrsymbols of swords cutting the ropes of attachment binding be ings tothis worldly samsara state of suffering, forms the outer edge of, orfence around, a big tent overarching the complete interior of themandala. The innermost mandala is thus set off an d protected fromall outside elements. The next ring of multicolored adjacent objectsis composed of lotus petals, blossoming around and holding up thecentral objects above a triangular cone supporting the entirestructure. Its three-sided structure also represents the three doorsto liberation, the wisdom of emptiness in complete form, or thewomb from which manifestations arise such as the lotus blossoms.Four porticos, which should be envisioned as uprightstructures flanked by a pair of trees underneath a pair of stylizedclouds, provide decorative entryways to the four gates. Foursnakes (or nagas ,w ind ing caduceus-like u p four poles w ithineach quadrant, symbolically represent rainbow bridges betweenthe outer rims and the next layer of square wallsunitingrelatively earthly with heavenly realms (Wheatley 1971). Thenum erical utility of fou r evokes the Fou r M indfulnesses,Four No ble Truths, and four aggreg ates (body, sensation, mind ,object). The four gates in the m idd le of each walled framew orkrepresent the four cardinal directions. It is easy to visualize thepalace as three-dimensional, since the perspective of gatewaysshows height proportionally smaller from outside to inside, withthe central deity occupying the commanding heights. The fivecolors of the inner walls (white, gold, red, green and blue) aroundthe T-shaped entrances echo the five aggregates, or wisdomenergies, of the body. The elements depicted within the square

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

8/19

8 Journal of Cultural Geographyan em pow erm ent ceremony, which can last for several hours.The teaching lama presiding over the ceremony functions as anexperienced tour guide. He directs the step-by-step construction ofthe mandala elements in the mind of the participants, first rituallypurifying the space underneath the tent within which the ceremonyoccurs, and metaphorically becoming the central deity whosevirtues the participants aspire to acquire. The lama-teacher directsentry through the east gate, guides the ensuing circumambulationin clockwise fashion throug h the mand ala, and awaits the arrival ofthe practitioner-pilgrim in the center. Ideally, special insight isachieved by the voyager either during the progress of the journeyor upon arrival at the core.

The mandalaparticularly the central representation whichcan take the form of a deity, symbol, or letteris composed of allthe elements the observer/practitioner must develop in order toachieve the enlightened state of the central deity w ho is the focus ofthe mandala {in this example, the wisdom mind). Practitionersadvance by stages of gradually attained understanding. The man-dala acts as a visual aid so travelers have a sense of wh at place theyare entering and where they are within it. The observer's role liesin mentally putting him/herself in this place. In some advancedceremonies the participant is blindfolded, then directed to visualizethe various entities portrayed along the path within the mandala'spalace. Eventually the blindfold is removed, and the practitioner isintroduced to various deities visualized in different directions. Thefinal central deity is the one the practitioner aspires to become, sothe mandala exercise is an introduction to the initiate's hoped-forfuture dwelling place. When the lesson is understood, leading toinsight into one's own true nature as a union of corporeal bodyand incorporeal clear light, all illusions disappear and the goalof purification is achieved.

SPATIAL VISUALIZATION AS A GEOGRAPHIC EXERCISEModern geography has considerably enlarged upon thetraditional boundaries of what was considered mapping, andgeographic visualization constitutes a particularly dynamic, inter-active component of cartography {MacEachren 2003). Geographers

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

9/19

Mandala as Sacred Spatial Visualization 79through multidimensional, metaphysical space, further enlargesthe scope of geographic conceptions of spatial interaction.Locating a place in space is a way of saying where somethingis in relation to something else. Geographic approaches to spatialrepresentation are linked to core spatial concepts of location, region,distribution, spatial interaction and scale that constrain and shaperepresentations of observations. All are discrete physical entities.Cognitive spatial representations function as mental models ofgeographic environments portraying what people think they knowabout an environment, and aiding understanding of how thisimage influences their behavior (NRC 1997). Buddhist philosophyconsiders space, earth, water, fire and air as constituting thefundamental Five Elements of conventional (as distinguished fromabsolute) reality (Zajonc 2004). Materialist Newtonian cartogra-phers confine the realm of map-making to depictions of datasets.Neo-Kantian idealist (and Buddhist) depictions of spatial visuali-zation extend the role of maps to seeing the unseen (Dorling andFairbairn 1997, 102) in order to discover the unknown which isdepictable, explorable, and ultimately available for solving prob-lems and constructing new insights (Kraak 2003).Use of the outer-inner, top-dow n, God's eye view of earthcomplements the detached, scientific perspective implicitlyadopted for construction of many maps (Hallisey 2005), The three-dimensional computer-generated projection of a fly-through terrainuseful for training pilots, plotting military applications, aidingtopographic analysis, and video game entertainment, are alsosimilar to a practitioner's experience of mentally envisioned, guru-guided mandala navigation. The interactive nature of mandalanavigation, wherein the participant follows guided paths to en-counter the lessons depicted and embodied in the imaginary three-dimensional palace-mazes, correspond to the navigational prowessof human-map interactions through queried terrain in cartographicdepictions in a Geographic Information System (GIS) environmentof simulated space based on material landscapes.

More concrete represen tations, as outlined in Table 1, consist oftwo-dimensional mandalas drawn on temple walls and flat

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

10/19

80 Journal of Cultural Ceograph ysis is placed on the relations, in an abstract sense, am ong thethings sym bolized (Bryant 1993, 103), relying on the spatialabilities of the perceiver to interpret interrelationships betweenphenomena in several visual dimensions representing two or moredata dimensions. The cosmogram's purpose lies in restoringa harm onious balance and reconsecration [of] the earth and itsinhabitants (DLI 2004). Use of mandalas as healing devices,wherein the ill person enters the sacred precincts in order to berestored to their primal balance through the powers of the residentdeity(ies)can be found in some sense in such disparatecommunities as the Assyrians and Navajos as well as Tibetans(Allen 1998).Earthly as well as imagined residential communities con-structed along the lines of a sacred schematic have ancient rootsin Asia. Wheatley's classic The Pivot of the Four Quarters(1971)examined the micro-cosmological significance of the traditionalChinese city which was designed to approxim ate on earth the layoutof a deity's residence and surroundings. Components of thecosmologically appropriate abode shared by both the ideal Chinesecity and the mandala palace include cardinal orientation, cardinalaxiality, and a ... square perimeter delimited by a massive wall(Wheatley 1971,423). W heatley's work cites abu ndant examples oftemple cities throughout Asia (including South Asian India andSoutheast Asian Cambodia) that conscientiously sought to followa sacred cosm ograp hy (Wheatley 1971,436). The urban designer'sgoal lay in creating a peaceful harmonization of the human andideal spirit world by building a concrete version of the deities'dwelling. The central axis mundi a round pivot at the center,represented the earthly M t. Meru, dw elling place of the spirit w orld.

The earliest Tibetan monastery of Samye, and Lhasa's centralJokhang Temple, were constructed architecturally on the samecosmological principles, invoking design correspondence betweenthe two worlds of the concrete observed by the contemporary eyeand the ideal invoked mentally. The central plan involving fourmajor and eight minor continents revolves around Mt. Meru in themiddle, following the tantric Mahayana tradition of Tibet (Martin2005). The central area also contains a statue of Buddha and

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

11/19

Mandala as Sacred Spatial Visualization 81function of mandalas as mapping two and three-dimensionalrepresentations of exalted spaces in a spiritual world.

MANDALA AS COSMOGRAMThe cosmogrammatic mandala represents transitorily in-habited, constructed space. The earliest use of the term m anda lareferred to verses in the sacred Hindu Vedic scriptures (the Atharva-Veda, early in the first m illenn ium BC) tha t lirUceddepictions of dwelling places of holy beings, cosmograms, and thehum an body. In the sixth century AD the Vastupurusam andlasevoked a plan for cities and buildings similar to that of Wheatley's

archetypal Pivot of ourQ uarters with ritual altars as a possibleprecedent, utilizing the construction device of apportioning spaceas in a metaphysical temple (Meister 2003). Mandalas as sacredspaces could also apply to caves or other real world locationsbelieved to be inhabited by the holy. Circles were drawn as placesfor teachers to sit within and transmit their teachings. The precinctsof Bodhgaya's bodhi tree, under which the historic princeSiddhartha Gautama chose to meditate when he experienced hisenlightenment, was already considered one such special place. ByBuddha's time (563^83 BCE), mandalas were freed from actualplace fixity in order to depict ideal dwellings wherein mobilepractitioners and spirits could metaphysically cohabitate.

Mandala construction in the Buddhist system usually takesplace as part of a religious ceremony where associated spatialvisualization occurs. Only practitioners who receive permissionfrom their teachers as having attained the required basic under-standings are permitted to attend, so they can understand the im-parted insights on the three levels: outer meaning available to all,inner meaning for those with more learning, and secret meaningfor initiates only Public constructions of mandalas are seen asbestowing benefits upon observers, at whatever level they are ableto understand the process and message of the cosmogram. Thepurpose of ritual arts such as mandala construction is to invoke thedeity pictured in the center of the mandala. The observer, whoaspires to become like this sacred model, is guided through themandala labyrinth by a guru (a monk who is in the primary

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

12/19

82 Journal of Cultural Geograp hy

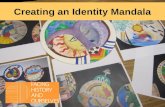

Fig. 2. Constructing Mandala. Photo by author.ground where prepared visitors can experience heightened aware-ness and take significant strides in their understanding of the worldoutside and their inner na ture (Bryant 1993; Zan gpo 2001).Mandalas are representations. The real mandala relates to aspectsof the mind, providing a metaphor to help transcend the per-spective of ordinarily perceived existence.The particularly Tibetan tantric mandala is often constructedon a raised platform such as a table (Fig.2 , representing the placewhere Siddhartha Gautama sat when he attained enlightenmentand became Buddha, the awakened on e, in a marked off, sacredprecinct at the base of a bodhi tree (Ten Grotenhuis 1999). Raisedwithin the Hindu tradition. Prince Siddhartha well understoodthe sacredness of special places that occur throughout India andconstitute pilgrimage sites through the present day (Bhardwaj1970). Both the piled sand mandala and the flat th ngk shouldbe mentally visualized as three-dimensional entities, fully realizedfrom the two-dimensional representations. The top-down view

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

13/19

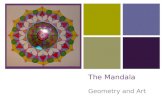

Mandala as Sacred Spatial Visualization 83The ensuing process of re-occupying the sacral space illustrates thecultural labor of ritual, in specific historical situations, involving thehard work of attention, memory, design, construction, and controlof place (Smith 1978, 88).Symbolic patterns traced with colored sand {dul-tson-kyil-khoror colored powders center circles ) constitute the most com monform of the mandala. Mandalas can be two-dimensional and con-structed of rice, flower, stone, jewels, or sand, or three-dimensionaland made from materials such as wood or metal. The type ofmaterial used in the construction relates only to issues of cost andconvenience, rather than symbolism. Borders setting off elementscan be either slightly raised areas of heaped material or fullyconstructed elevations. The graphics used in the central andsurrounding areas can be anthropomorphic representations ofdeities, sacred symbols, or special letters with sacred meaningassociated with the deity and its virtues such as the blue Akshobyhamanifestation of Buddha represented by the seed syllable for peacein Figure 2. The monks envision a transcendent place suitable foroccupation by deities as they draw the mandala, which also makesboth the space and the act continuously sacred. Dances and/orprayers employed before the construction begins and again near theend immediately prior to invoking the presence of the deityportrayed also act to dispel negative obstructions. At a specialpoint near the end of the mandala ceremony, both the deity it isdesigned for and the human observer are invited by the presidingguru-guide to mentally inhabit the constructed environment (Fig. 3).

CONCLUSION: ANALYTICAL INTERFACESOntological notions concerning the nature of reality inevitably (ifnot always consciously acknowledged) spill over into cartographicdepictions. Geographic approaches to cartography largely fall intotwo camps: the Newtoruan-Cartesian materialist approach whichasserts that mapping records the physical world, plotted mathemat-ically to scale, or the Neo-Kantian v iew that all reality is a projectionof the mind, and cartography is simply a recording of mentalperception (HallLsey2005).Although both w ould agree that maps are

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

14/19

8 Journal of Cultural Geograp hy

Fig, 3, Consecrating Mandala. Photo by David Hilbum.but depict an imaginal world-pattern ing directly affecting innerstructuring of physical and m ental senses through . . . a w orld-picturereflecting the brain's perception of its environm ent (Thurman 2000,143) that becomes imbued with a sacred presence. As the goal ofNewtonian cartography is to depict an accurate representation of theobservable material world, the mandala maker seeks to chart thenature of an ultimate world, utilizing a cosmogramm ar , , , ofcultural representations (Thurman 2000, 144).Geographers such as Harley (1989) assert the underlyingsubjective, cultural-centric and hierarchic nature of maps. Man-dalas,with their centrally-placed deity, certainly fit this category ofspatial visualization. Research insights of Mark (1999) and Lakoff

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

15/19

Mandala as Sacred Spatial Visualization 8mathematics or art. Regardless of cultural contexts, the functionand importance of objects have a similar order in terms of hierarchy,proximity, size, distance, direction and placement within referenceframes. Mark concluded that maps are inextricably connected tomental perceptions, which in this research corresponds to Buddhistdepictions within mandala representational schemes.Eor pioneer psychoanalyst Carl Jung the mandala served as anexam ple of creative expression reflecting a collective unconsciousladen with symbols of human experience that the mind drew uponto decipher understanding {Masquelier 2004). Jung created person-ally designed manda las to order his troubled psyche, enabling himto interpret the pattern of symbols generated. Such personalinterpretations, unrelated to larger belief systems, serve principallyto indicate the usefulness of mapping mental perceptions withina Mandalic organizational scheme (Tucci 1961). Cartographicdevices likewise attempt to draw on nonverbal, shared under-standings of symbolic meanings for the power of their shorthandrepresentations, sometimes assisted explicitly in a legend.

Sacred space is often an outcome of contestation (Kong 2001).Although mandala making by specially trained monks occurs aspart of traditional ritual practices in Buddhist temples, creatingmandalas in Western public venues inserts a space for cultural re-creation, a key point in the Sino-Tibetan contestation over thephysical space of Tibet. Mandalas are produced in secular spaces(e.g., museum s or schools) in the West by monks dispossessed fromtheir Himalayan homeland as a consequence of China's 1959invasion of Tibet, the source location of Tantric Buddhism. China'ssubsequent occupation and annexation of this territory, andsuppression of Buddhist practices, led to the movement for pre-servation of Tibetan cultural elements in monasteries establishedby immigrants throughout India, an overwhelmingly Hindu andMoslem nation that was the birthplace of Buddhism. The territorialand cultural dispute is projected by building mandalas as aneducation and blessing for their beholders, and to place Tibet backon the mental map of global consciousness. This type of sacredspace is indeed entangled in new geographies of religion as politicsand poetics in modernity, of social, economic and pohtical

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

16/19

86 Journal of Cultural Geog raphySpatial visualization plays a powerful part in the cartographicconstruction of a mandala. The representational devices of tieredsquares within a circular dome, topped by a deity-dwelling inner

sanctum, which the observer reaches by navigating the innercourtyards and corridors, clearly serve as mapped meanings thatconvey culture-laden messages. Patterned relationships play outwithin a physical as well as metaphysical spatial format. Theemancipatory nature of this sacred map lies in the premise that thetraveler can become enlightened, attaining the insights of the guruand the deity whose virtues are portrayed, by learning the lessonsconveyed along the way. As a primary meditation device, themandala serves as a map for three-dimensional buildings, two-dimensional art hangings and sand paintings, and interior mentalvisions. It is a patterning of space that imposes structured order toconvey cultural meanings, partially inherited from Hindu and Jainpredecessors in the Indian Buddhist hearth.

Mandalas function as moral and mental maps, expanding theparticipan t s vision of interior space and add ing a new dimensionto non-Buddhist notions of cartographic imagery as well as culturalgeography. Geographers and visionaries in other disciplines utilizespatial visualization and map metaphors as communication mediafor their imaginings of reality, as well as for analysis of relationshippatterns. Whether the ultimate nature of reality consists of bits ofinformation rather than energy (Sui 2004), or underlying and on-going consciousness that shapes and is shaped by other forces inthe Buddhist worldview, mapmakers construct bridges for theexpression of such varied ideas. The purpose of the forgoing dis-cussion lies in continuing to open up notions of space, fluidity,powers of depiction, and an expansive commonality in the humanendeavor to communicate complex insights about the nature ofreality within multidimensional spatial representations.

ACKNOWLEIXMENTSSpecial thanks to individuals experienced in mandala creation

associated with Drepung Loseling Institute, who gave their time toshare insights from years of study and practice. Any mistakes in

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

17/19

Ma ndala as Sacred Spatial Visualization 87Bender, S., I. Berry, B. Possidente, and R. Wilkinson. 2004. The World

According to the Nezoest and M ost Exact Observations: Ma pping Art +Science.N ew York: Skid m ore College.

Bhardwaj , S. M. 1970, Hindu Places of Pilgrimage in India: A Study inCultural Ceography. Ph.D. diss . . Universi ty of Minnesota.Brauen, M. 1997. The Mandala: Sacred Circle in Tibetan Buddhism. Boston:

Shambhala Publications, Inc.Bryan t, B. 1993.The Wheel of Time Sand Mandala: Visual Scripture ofTibetan

Buddhism. New York: Harper Coll ins Publisher .Butzer, K, 1978. Cultural Perspectives on Geographical Space. In

Dimensions of Human Geography, edited by K. Butzer, 1-14. Chicago:Universi ty of Chicago, Department of Geography Research Paper#186.

Dorling, D., and D. Eairburn. 1997. Mapping: Ways of Representing theWorld.Lond on: Ad dison W esley Lo ngm an Limited.

Drepung Loseling Institute. 2004. Magical Arts of Tibet. Brochure.Eliade, M. 1986. Symbolism, theSacred and the Arts. New York: Crossroad.Hallisey, E. 2005. Ca rtog raph ic V isualization: An A ssessme nt and Epis-

temological Review. TheProfessional Geographer 57(3): 350-364,Harley, J . 1989, Deconstructing the Map, artographica 26(2): 1-20.Harmon, K. 2004.You Are Here:PersonalGeographiesand Other Maps of theImagination. New York: Princeton Architectural Press,Kong, L, 1990. Geography and Religion: Trends and Prospects .Progress in

Human Geography14: 354-371,. 2001. M ap pin g 'N ew ' Ge ograp hies of Religion: Polit ics and

Poetics in Modernity. Progress in Human Geography25: 211-233.Kraak, M. J. 2003. Geovisualization I l lustrated. Journal of Photogrammetry

Remote Sensing 57:390-399. akoff G. 1987, Wotnen,Fire,and Dangerous Tilings: What ategories Revealabout theMind. Chicago: Universi ty of Chicago Press .Leidy, D. 2000. Place and Process: Mandala Imagery in the Buddhist

Art of Asia. In Mandala: The Architecture of Enlightenment, edited byD, Leidy and R, Thurman, 17-^9, New York: Asia Society Galleriesand Tibet House.

MacEachren, A., B. Buttenfield, J. Campbell, D, DiBiase, and M,Monmonier. 1992, Visualization. In Geograp hy's Inner Wo rlds: Perva-sive Themes in Contemporary American Geography, edited by R. Abler,M. Marcuse, and J , Olson, 99-137. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

18/19

88 Journal of Cultural Geograp hyM asquelier, Y. 2004. Th e M an da la, a Sym bol of the P syche in the Life andWork of C. G. Jung. In Tibetan Mandala: Art a nd Practice The Wheel o

Time, edited by S. Crossman and J. Barou, 71-76. Old Saybrook, CTActes Sud.Meister, M. W. 2003. Vas tupurusamanda las . In Mandalas and Yantras inthe Hindu Traditions,by G. B uh ne m an n, 25 1-70. Leiden: Brill.National Research Council. 1997. Rediscovering Geography: New Relevancfor Science and Society.W ashington, DC: Nat ional A cadem y Press.Pott, P. H. 1966.Yoga and Yantra: Their Interrelation and TheirSignificancefoIndia Archaeology.The H ague : M ar t inus NijhoffRobinson, A., and B. Petchenik. 1976. Tlw Nature of Maps: Essays towarUnderstandingM aps and Mapping.Chicag o: University of Ch icago P ress

Smith, J. Z. 1978. The Wobbling Pivot. InMap is Not Territory:Studies in thHistory of Religions, edited by J. Z. Smith, 88-103. Leiden: E. J. Brillp p . 88-103Sui, D. 2004. GIS, Ca rtograp hy, and the Third Cu lture : Ge ograp hicImaginat ions in the Computer Age. TheProfessional Geographer 56(162-72.Ten Grotenhuis, E. 1999. Japanese Mandalas: Representations of SacredGeography.Ho nolulu : U niversi ty of Haw ai ' i Press.Thurman, R. 2000.Mandala: The Architecture of Enlightenment. InMandala:The Architecture of Enlightenment, edited by D. Leidy and R. Thurman,126-147. New York: Asia Society Galleries and Tibet House.Tucci, G. (1949) 1961. The Theory and Practice of the Mandala: With SpeciaReference to the Modern Psychology of the Subcon scious. Translated byA.H. Brodrick. London: Rider and Company.Wheatley, P. 1971.The Pivot ofthe Four Quarters: A Preliminary Enquiry intthe Origins and haracterof the Chinese City. Chicago: Aldine .Wilford, J. N. 1982. T he Mapm akers: Vw Story of the Great Pioneers in artography fromAntiquity to theSpaceAge. New York: Random HousZajonc, A., ed. 2004. The New Physics and C osmograp hy: Dialogues with theDalai Lama.Oxford: Oxford Un iversity Press.Zangpo, N. 2001.SacredGround jamgon Kongrui on Pilgrimage and SacrGeography. Ithaca, NY: Sn ow Lion Pub lications .Zehnacker, M. 2004. Christian Variation: The Labyrinth. In TibetanMandala: Art and P ractice, The Wheel of Time, edited b y S. Cross m anand J. Barou, 77-82. Old Saybrook, CT: Actes Sud.

Susan M Walcott is Associate Professor of Geography in the

-

8/12/2019 Mandala Mapping

19/19