Man in the White Cadillac

-

Upload

robert-johnstone -

Category

Documents

-

view

225 -

download

4

Transcript of Man in the White Cadillac

Fortnight Publications Ltd.

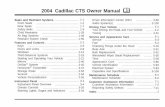

Man in the White CadillacAuthor(s): Robert JohnstoneSource: Fortnight, No. 302 (Jan., 1992), pp. 36-37Published by: Fortnight Publications Ltd.Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25553257 .

Accessed: 25/06/2014 05:39

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Fortnight Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Fortnight.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 25 Jun 2014 05:39:38 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Van Morrison's 'roots' are fairly adventitious

Before it was put out of action for up to a year by an IRA bomb, Belfast's most attractive nightspot, the Grand Opera House, last month

hosted a series of Van Morrison concerts. The run had to be extended to accommodate demand. Below?ROBERT JOHNSTONE takes a wry look at the Morrison phenomenon. Panel?NIGEL GUY reviews the

Opera House gigs and is impressed by a new sound at Mandela Hall.

Man in the white Cadillac

I DON'T WANT TO sound paranoid, but sometimes I

get the feeling that everywhere I go Van Morrison has

been there before me. It all started a year or two ago when I noticed a huge American car?a stretched

limo?parked at the end of our street in Chelsea. It was

only after visiting Belfast for Christmas that I worked

out who it belonged to. For, walking down Botanic

Avenue after a last-minute burst of present-buying, I

found the same big white Cadillac following me.

Who, in Belfast on Christmas Eve, would drive

around in such a car? Elementary, my dear Watson. Van

Morrison, then as last month, was giving a series of

concerts in town. So it must have been him behind those

black windows back in London too: maybe he was there

to buy some American retro fashion in Rancho De

Luxe, or maybe he was having a rug rethink in Smile.

Such speculations might irritate the more doctri

naire Vanfans, and on the face of it they do seem

unlikely. George Michael and his ilk need fear little

from the Belfast Cowboy in the personal grooming

department. What matters is the work?an artist can

have no time for the frivolities of the music business.

A South Bank Show documentary about Irish popu lar music confirmed the suspicion that Van had studied

at the Edward Heath Charm School. Most of the inter

viewees were relaxed with the camera, eloquent about

the traditional roots of their music, its 'Irishness'. But

the film-makers had decided Van needed someone to

draw him out, so they got 'Sir' Bob Geldof to ask him

questions. Nothing doing. He was "searching". What

more was there to say? It would be too simple to point out that he was the

only Northern Prod on the programme. The other, commer

cial artistes seemed unusual in their articulacy. Most pop stars are remarkably incoherent, considering they deal with

words every day, and despite their willingness to babble at

the nearest camera. Let's be thankful, then, when we find

one for whom a television interview ranks with dental

extractions as a way of passing the time.

What about Morrison's attitude to his 'roots', as on

Irish Heartbeat? Why does it so annoy the devotees of

'authentic' traditional culture? (Admittedly, there is some

thing gloriously weird about the collaboration with the

Chieftains, summed up forme in the sight of Van Morrison

and Derek Bell getting on down on guitar and tiompan.) One objection might be that you can't say much about

your cultural background by stringing together the sort of

songs music publishers call 'traditional' but which they have standardised, some banal folk-rock essays, and the

odd parallel-text Gaelic song. To perform these in a trans

atlantic-Belfast voice backed by a highly commercial,

though musically literate, 'folk' band adds insult to injury. The committed traditional musician might insist that to

understand and draw from the tradition it is necessary to

immerse oneself in it and become fluent in its idioms. Most

obviously, it is a non-commercial art, and you can't make

money out of it without changing its nature. To perform the

'real' music in an inauthentic way is as damaging as to take

seriously the inauthentic, stage-Irish music.

Morrison's approach is powerful but superficial. Yet

Irish traditional music, and Irish culture's sense of itself, seem vigorous enough to bear a little give and take. The im

purities may be accurate reflections of some of the contra

dictory strands in mass culture. Considering where he is

Demanding

performer

IT WAS A TYPICALLY contrary week in the life of Van Morrison. A

group of fans unveiled

a plaque to him, which

he promptly disowned, at the same time as a

scheduled three nights at the Opera House turned into five.

Van has now

assembled yet another

band around him. Out

have gone Georgie Fame and his col

leagues; in have come

a group of young but

extravagantly talented,

jazz-oriented musicians.

The drummer and

keyboard player would

have stood out in most

bands, but it was the

two female members of

the group who took the starring roles. Teena

Lyle on percussion and

vibes and Kate St John on saxophones and cor

anglais were never less

than excellent, at times

inspired. The potential of this line-up?if it stays

together for a couple of

years?is enormous.

Though the set was over two hours long, it

was no greatest hits

package, with a lot of

material both old and new with which I wasn't

familiar (and thankfully no Glotid). One of the songs I did know and love, a particularly fine

version of Cleaning Windows, stood out, while there can't be

many Morrison audi ences over the years that haven't heard him

belt out Twisting the Night Away, which he did for an encore.

For me, one of the

most impressive

aspects of the evening was being able to see

him operate at close

quarters for the first time. Even from the

stalls, though, I still

couldn't work out where

that unique voice

comes from, but I was

able to detect a smile on several occasions. (I do think he actually enjoys making music,

you know.) The only complaint I

had of this excellent evening?speaking as

a major jazz sceptic was that Van kept his group under too tight a

36 JANUARY FORTNIGHT

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 25 Jun 2014 05:39:38 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rein at times. Some of the solos really should have

been allowed to live out

their natural life, instead of being curtailed when there was a lot of worthwhile exploration still to be done.

The restrained atmos

phere of the Opera House and the crystal-clear sound

made for an evening almost of quiet reflection when compared to Curve in the Mandela Hall the same week. But if the

volume was at times

excruciating, the best new

group of 1991 on record didn't disappoint, live.

Their beautiful lead singer, Toni Halliday, has a

dodgy pop past, which shows through when she

smiles and says 'thanks' at the end of each song?

distinctly un-indie behav iour. But these smiles come

at the end of songs dealing with anger, pain, disgust and contempt: 'You could be my father for all the love

that you showed' is one of

my favourite lines, but a

fairly typical one.

Allied to this potent vocal mix of sweetness and

anger is the music. Now, a

lot of groups in the past few years have mixed up

searing, distorted guitar noises with a dance back beat?but nobody has

done it quite like Curve in their brightest moments in the Mandela. The rough

edges were so smoothed

away that the music

seemed to bend into the sexiest sound I've heard in

years. At times I was

convinced I was listening to a totally new kind of music.

In the disparate con

temporary music scene it's

impossible to hail anyone as the future of rock 'n' roll. But Curve are one of the few acts giving me hope that the old dog still has a few years life left in it yet.

v.^- - v . v ^t v^B - - Q.

coming from?rhythm and blues?it might be kinder to welcome Morrison's interest in things nearer home.

His simultaneous translation of lyrics in Irish could

be seen as expressing well-intentioned aspiration rather

than presumptuousness. His approach to traditional

music may be naive and ingenuous, but the principal virtues of rock are naivete and ingenuousness. We

cringe to see footage of Mick Jagger trying to sing for

Muddy Waters, yet the Stones' early homages to black

music remain fresh and, in a convoluted way, valid.

Despite his awareness of jazz, which can be oblique and intellectual, Morrison favours a more upfront ap

proach to music, one which tends to trust rather than

become impatient with the unassuming honesties of

inarticulacy. His songs aim at a speaking-in-tongues, the moment when language becomes music and

inarticulacy is transcended. In Irish traditional music

there is prodigious subtlety and intelligence, however

concealed. There is subtlety and intelligence in Morri

son's approach, but no slyness. His method is inspira tion or inebriation, rather than calculation and the clash

of virtuosity with elaborate form.

For someone so apparently straightforward he can

be baffling. Is there an underdeveloped sense of the

ridiculous? What are we to make of someone who

collaborates with Paul Durcan, Georgie Fame and Cliff Richardl Morrison has a syncretic streak, seeking to

combine rather than refine. His world includes Belfast

streetlife, the romance of popular ballad, Celtic Twi

lightery, the extremism of black American forms, Eng lish mysticism. He scores country music forthe uilleann

pipes, backs 'traditional' musicians with rock drums.

His lyrics quote from and allude to other songs and

poems, and he not infrequently imitates, in simple minded onomatopoeia, sounds to which his lyrics refer.

Some might find a similar magpie approach to the

religious allusions. 'The old rugged cross' lies along side Avalon on his 1989 album, Enlightenment. This exemplifies a number of contradictions in Morrison's

work. As always, it veers between convergent and

divergent ways of thought, between the closed and

systematic, and the wispy. What would Ian Paisley sound like if he'd graduated from UCLA instead of Bob Jones University?

Another odd incident from that Christmas seems emblematic. Returning by taxi in the wee hours from a

convivial evening with the author of The Pocket Guide to Irish Traditional Music?an evening during which

we disagreed about Van Morrison?what should draw

up alongside us at traffic lights but the same white

Cadillac? That huge car, shining in wet darkness in

front of Divis Flats, seemed bizarre, almost egregious. Unlike most rock stars, Morrison is highly musical.

He is an inventive orchestrator and has a voice that can, in its fashion, enhance almost any material. In nearly

thirty years of recording he has written some memora

ble songs. My favourites are the earliest, bluesiest

Them hits: Gloria is as celebratory as its title. Later

songs like Wild Night, And It Stoned Me, and Cleaning Windows are nostalgic paeans to Belfast adolescence as

atmospheric as anything I know.

Nevertheless, the lyrics are better heard across a

crowded room than read closely from the thoughtfully

provided word-sheets. One suspects Van does take

himself rather seriously. Often he aims for a psalm-like

monotony rather than a catchy tune. Too many tracks

rely on one cadence endlessly repeated, with variations

and elaborations by his flexible, throaty voice. Too

often his excellent collaborators are left to play around

a single interval.

He takes wild risks with his voice, bending notes and

embellishing phrases up to and beyond the limits of

taste and proportion. Even on something as incongru ous as My Lagan Love?an art song masquerading as

'traditional'?performed with a freakish soul intensity, Morrison can make the hairs stand up on the back of

one's neck. All the rest, including what is being sung about, may be nonsense or so attenuated as to be

subliminal. But, often enough, that seems less impor tant than the wonderful noise.

A WIND OF CHANGE?

JAN ASHDOWN reports on opportunities for a new broom to sweep through the Arts Council of Northern Ireland

ON DECEMBER 5th, the Arts Council of Northern Ireland announced the appointment of Colin Radford, professor of French at Queen's University, as the new chair for its board; while Lord Belstead, the Northern Ireland

Office minister responsible for the arts, announced a comprehensive review of the arrangements for arts funding, which will pay particular attention to the role, composition and operation of the Arts Council. These announce ments come hard on the heels of the appointment of a new Arts Council director, Brian Ferran, after much

controversy earlier in the year (Fortnight 296). The review, to be completed by May, will be undertaken by Clive Priestley CB. Mr Priestley is described as

a management consultant with widely varied experience, including the financial scrutiny of the Royal Opera House and the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1984. He will be assisted by two assessors, Dr Maurice Hayes and Mr Bryan Johnston.

Simultaneously, the Arts Council itself, in line with strategy initiatives being pursued by the Arts Council of Great Britain (with such partners as the British Film Institute and the regional arts boards), will prepare a parallel strategy document, which will amount to a total re-examination of the institution. Suddenly the building that to some resembles Gormenghast is to be energised by appraisal from not one, but two sources.

The reassessment will encompass:

the Arts Council's relationship with government (policy determination and implementation), with clients and with other comparable bodies;

control of the Grand Opera House and the Arts Council Gallery in Belfast; and the Arts Council's internal structures, even its constitution.

This is welcome news, since the potential outcome of both processes is the emergence of structures and approaches more appropriate for the 1990s. Genuine appraisal takes courage: for some, the possibility of change is more a

threat than a desirable stimulus. A bigger threat, however?and one evinced more widely in Northern Ireland? is the refusal to meet new circumstances and needs with new thinking.

FORTNIGHT JANUARY 37

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 25 Jun 2014 05:39:38 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions