Malthouse final

-

Upload

assignment-help -

Category

Engineering

-

view

59 -

download

3

Transcript of Malthouse final

CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT STRATEGY: MORE IMPORTANT NOW

THAN EVER BEFORE

By Edward C Malthouse

Customer relationship management (CRM) is a systematic process for managing

interactions with potential, current and former customers.1 CRM is most appropriate for

situations when the organization has a database of information about individual customers. Big

data sources such as records of social media interactions and mobile data imply that

organizations will have an increasing amount of information about individual customers in the

future. Firms will also be able to purchase an increasing variety of such information from third-

party data providers.

The purpose of CRM is for the organization to use information it knows about individual

customers to increase their profitability. It does this by improving the relevance of its

interactions with customers. When messages are personalized or the customers are allowed to

customize their interactions with the organization, customers can become more satisfied and

loyal, which, in turn, increases their value to the firm.

While scholars and practitioners have not agreed on all of the details of a single CRM

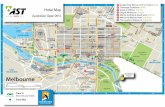

process, this chapter will be organized around the process depicted in Figure 1. The outer circle

of Figure 1 involves four primary steps and is consistent with other CRM processes. In the

sections that follow we will discuss each of the steps in the process. CRM usually begins by

segmenting, understanding and valuing customers. Next, one attempts to identify strategies for

increasing customer value, which is used to inform the allocation of marketing resources.

Contact points are created, and the outcomes are measured.

Before discussing the CRM steps we discuss how they are related to traditional

advertising and branding, which are indicated in the “Brand” and “Contact” circles. Figure 1

integrates CRM with advertising. The CRM process will become increasingly important to

advertisers as advertising becomes more data driven.

We close with a discussion of the future of CRM in advertising. What is new is that more

customer interactions are taking place in digital environments, which has several important

implications. More interactions can be recorded, which means that marketers will have additional

and better information for making decisions such as segmenting, understanding and valuing

customers, executing marketing programs and measuring results. Advertising will become more

data driven, and the CRM approach will play a larger role in advertising.

Figure 1: A Process for Customer Relationship Management

Inner Circles: The Relationship Between CRM and the Brand

We first discuss the inner circles of Figure 1—contacts and the brand—and their

relationship to the outer CRM process. These inner circles are not usually thought of as part of

CRM, but they should be considered by anyone implementing CRM. Interactions with the brand

will be called contact points, or sometimes just contacts. They include all customer encounters

with a brand. Many contact points are initiated by the organization, such as advertising or direct

marketing, but some are not, such as when customers call tech support or use the product.

Sometimes other customers and even non-customers create contact points, such as when

someone creates a video and posts it to YouTube, writes a restaurant review on Yelp or Google

Reviews, or tweets about a movie. Interactions between customers are indicated in Figure 1 by

the two-way arrows between customers in the center. This will be discussed further in the last

section of the chapter.

A difficult problem is maintaining the consistency of all the various contact points. A

solution to this problem is to have a brand concept. By a brand, we mean the idea that the

organization wants consumers to have about it. It is an idea that is articulated first by the

organization. The brand idea explains why a product or service is of value to its customers.

Advertising is often used to communicate this value in its contact points.

Conflicting contact points that do not support the brand may confuse consumers and be

counter-productive. The contact points generated by CRM systems should not be in conflict with

those from more traditional advertising channels. Those creating contact points for CRM systems

must understand what the brand is intended to accomplish and not do anything to undermine it.

The focus of this chapter is not on branding, but it is important to recognize that it plays a critical

role in CRM by providing the idea that should be communicated in contact points. Sometimes

organizations give a marketing department responsibility for the brand, but other contacts are

managed by other departments that do not coordinate their activities with marketing or other

departments.2

Understand, Segment and Value Customers

Having a relevant and meaningful brand concept is important, but it is often not enough

to be successful. Brands are usually targeted at a specific market segment, and customers within

the market segment are potentially heterogeneous in many ways. Some will be established, loyal

customers, others will be new and learning about the brand, and others will have discontinued

their relationship with the organization entirely. Different customers within the same segment

may still have different wants and needs, and therefore seek different relationships with the

brand. Managing thousands or millions of customers and prospects is a daunting task. Thus, we

try to identify groups of customers with similar behaviors and/or needs and wants. The

honeycomb pattern in the center of the diagram is meant to represent the different customer

segments.

These groups are called subsegments or customer segments because they are groups

within the targeted market segment. The brand is targeted at the market segment and a single

overarching brand concept is relevant to all sub-segments.3 The interactions with sub-segments,

however, will be personalized and customized so that they are more relevant and so that an

appropriate amount of marketing resources are invested. An organization's customers will have

different wants, needs, preferences and behaviors. For example, some airline customers fly often

and others don't. Some supermarket customers buy organics while others have different

preferences. Because of this heterogeneity, a firm should not offer the same contact points with

all customers. Offering coupons (a marketing contact point) for chips and soda to a customer

who buys only health food would not be relevant to the customer and would likely be ineffective,

wasting marketing resources. Those flying 100,000 miles a year have different needs than those

who fly once every other year, and all contact points—from emails and direct mails to security

checkpoints—should be tailored to meet the needs of different customers and be justified

financially.

As another example, consider a cable TV company that also provides Internet and phone

service. Different customers will subscribe to different services. Some will be “triple play”

customers who use all three, while others will be “cord cutters” who only purchase Internet

service. Of those who subscribe to cable TV, some will only purchase basic channels, while

others will pay for premium channels such as HBO. Some will also use pay-per-view services. It

is desirable to sell customers additional services, but sending an offer for basic cable to someone

who is already a triple-pay customer would be a waste of marketing resources and an annoyance

to the customer.

Bases for Customer Subsegmentation

Perhaps the most difficult and important step in developing a subsegmentation is

selecting the attributes that will be used to define the subsegments. There are seemingly

unlimited attributes that can be measured on customers—which should be used? The way people

are grouped depends on the attributes used to define the subsegments. As an extreme example,

people will be grouped one way if height is used to define subsegments, and a completely

different way if eye color is used. Selecting the attributes is a subjective task.

The ultimate question when selecting attributes is whether the resulting segments are

actionable: do they facilitate contact points that are uniquely relevant to a group of customers so

that their value can be increased? What is actionable depends on the context. For example, it is

difficult to think of any contact points that would be uniquely relevant to airline customers who

have blue eyes versus brown eyes, and therefore eye color is not a good segmentation variable

for airline customers. On the other hand, eye color could be useful for a company that makes

cosmetics. We discuss below different variables that can be used to segment customers.

It is important to note that a marketing/brand manager should be involved in this step.

The manager cannot leave it to the data miner to do this step; if the manager does, the result is

often a subsegmentation system that is not actionable and that is never used. The manager

usually has important knowledge about what can be done from a marketing perspective and

about what types of customers exist. The brand manager and data miner should always have a

discussion about what can be done differently from a marketing perspective. What are the

marketing objectives? What classes of tactics can be considered? For example, is it only

possible to change the way that the product is described in the offer? Or is it also possible to

create versions of the product itself, for example, by creating different configurations of

features?

RFM: Recency, Frequency and Monetary Value

Three of the most important variables are known as RFM. Recency (R) is the length of

time since the customer purchased most recently. This variable is often the best indicator of

whether a customer has become inactive. When customers have not purchased for more than,

say, 6 months, the organization may want to send out special contact points to reactivate the

customer. In many industries, the probability of a future purchase decreases geometrically with

recency.4 For example, a customer who has been inactive for R=1 year is half as likely to

purchase again as one who has only been inactive for 6 months. Likewise a customer who has

been inactive for 2 years is half as likely as one who has been inactive for 1 year.

Frequency (F) is the number of previous purchases a customer has made. It is a simple

measure of behavioral loyalty. One-time customers will often require different contact points

than multi-time customers. The likelihood of getting future purchases usually increases with

frequency. show that the effect of frequency on the probability of a future purchase follows a

learning curve.5

Monetary value (M) is the total revenue that a customer has generated in the past. The

ratio of monetary value over frequency gives the average order size (AOS) in the past. AOS will

be the best predictor of future order sizes. Customers who have placed smaller orders in the past

tend to place smaller orders in the future.

RFM is often used to produce subsegmentations. For example, consider the simple grid in

Figure 2. Each cell is a segment. Customers with F=1 and R < 6 months are new customers, who

may require special contact points to introduce them to the brand. Customer who have bought

more than 2 times and have R < 6 tend to be the best customers. Customers who have been

lapsed for more than 2 years are probably no longer customers and will be difficult to reactivate,

but among these customers, those with more previous purchases will be easier to reactivate and

should usually be the highest priority. This segmentation could be expanded further by crossing

it with average order size, for example, customers who place small orders versus large orders,

giving a total of 4 × 3× 2 = 24 cells.

Recency Frequency=1 Frequency=2 Frequency>2

< 6 months

6-12 months

12-24 months

> 24 months

Figure 2: An RFM segmentation

RFM is often computed by product category. For example, a drug store may be interested

in knowing which of its customers buy cosmetics. A simple way to identify these customers is to

compute RFM for cosmetics only, i.e., number of purchases with cosmetics in them, total

amount spent on cosmetics, etc.

A fourth variable that is often important is time on file, which is the length of time since

the first purchase of the customer. This tells whether the customer has long tenure, or was newly

acquired. Dividing frequency by time on file gives the purchase rate, which can be useful in

many situations. For example, a computer manufacturer such as Dell may want to segment their

customers by how often they purchase a new computer. Someone who upgrades every 5 years

will require different contact points than a customer who upgrades every year.

Demographics and Firmographics

Demographic variables are often used to segment customers because they are widely

available from third-party data providers such as Experian and Acxiom, but they tend to be

weaker predictors of subsequent purchases than RFM—demographics add little when good

purchase history (RFM) data are available. Demographics are especially useful for prospective

customers because no purchase history is available for someone who has not purchased yet. The

most commonly available demographics tend to be age, income, gender, marital status, and the

presence of children. There are many commercial segmentation systems that are based on

demographics such as Claritas’ Prizm, Equifax’s Cohorts and Acxiom’s Personicx systems. In

B2B situations it is possible to purchase firmographics, such as the number of employees that a

firm employs and the industry it is in (SIC code).

Motivations and Experiences

Experiences are the thoughts and beliefs that customers have about the role a product or

service plays in their lives.6 For example, Malthouse et al. (2015) study the motivations for

attending an industrial trade show and find three experiences.7 The first is a purchase experience,

where people attend the show to meet with vendors and see products so that they can make a

purchase. The second experience is educational, where they attend to learn about industry trends.

Those seeking an education experience attend keynote speeches, pre-conference seminars and

other sessions during the conference. The third experience is social / networking, where

attendees seek to make new contacts and enjoy the dining and entertainment available in the

conference city. Those seeking the social experience, for example, attend the happy hour events.

It is possible to identify segments based on the experiences, and use the segments to improve the

design of the conference.

Experiential-based segmentations can be very powerful, but a problem is that they

usually require surveys, and therefore segment membership is known for only those who

complete a survey. This limits the ability to do direct targeting with contact points.

Share of Wallet

Share of wallet (SOW) is the fraction of a customer’s purchases within some category

made with the focal firm. For example, if a customer always flies United Airlines, then United

has 100% SOW. A customer who flies half the time with United and half the time with another

carrier has 50% SOW with United. SOW is a desirable segmentation variable because it implies

different actions.8 If a firm has 100% SOW, the focal firm will only be able to sell more if it can

increase category consumption, e.g., get the customer to fly more flights. It is usually easier to

increase consumption from customers who have SOW less than 100%, because this requires

getting the customer to switch purchases from a competitor rather than consume more.

It is usually difficult to know SOW for individual customers, since any given firm will

usually not have purchase data from competitors. Market research surveys can ask about

purchases with all firms in a category,9 but then SOW is only known for those who complete the

survey. Another approach is to infer SOW from other data. We give several examples. First, a

supermarket with a loyalty program should ask the number of household members and their ages

at the time of enrollment in the program. With this information, the supermarket can estimate the

number of calories required by the household during a week, and compare it with the number of

calories purchased at the supermarket. If a household of two adults requires 5000 calories per

day, and the household is only purchasing 1000 calories per day, the supermarket can infer that

the household is purchasing “calories” from somewhere else and that it has an opportunity to

expand its share.

As a second example, suppose that a cable TV company has a customer who watches

many hours of TV and also has Internet service, but then “cuts the cord” by dropping cable

service and keeping the Internet service. If the customer subsequently increases data usage the

company can infer that the customer has switched to streaming, e.g., from Netflix or Hulu.

Alternatively, if the customer does not increase the amount of data, the cable company might

infer that the customer has switched to another source for TV, such as satellite. The actions taken

by the cable company for the two will be different.

Promotional Response

Another useful segmentation variable is how customers respond to various types of

promotions. For example, some customers frequently use coupons while others never use them.

Some customers are responsive to price discounts while others are not. It is a waste of time and

resources to send coupons to customers who are not responsive to this type of incentive.

Valuing Customers

Two ways of valuing customers are to consider the historical and the future value.

Historical metrics look backward in time while the future value of a customer requires a

statistical model to project the future cash flows. This section gives a short introduction to both.

The simplest historical metric is monetary value (which is the M in RFM). Customer

profitability is the difference between the revenues earned from and the costs associated with the

customer relationship during a specified period,”10 and is more complicated to compute because

it can be difficult to determine which costs should be deducted. Both measures are historical

because they look back in time. They represent “water over the dam” and they are only relevant

to future decision making to the extent that they predict the future profitability of the customer.

As was mentioned in the previous section, RFM is often among the best predictors of future

purchases, and is therefore commonly used to segment customers.

The most important future-oriented measure is customer lifetime value (CLV), which is

the discounted sum of future cash flows attributed to the relationship with a customer (Pfeifer, et

al. 2005). In simple terms, CLV estimates the “profit” that an organization will derive from a

customer in the future. It is an important concept because one of the main goals of for-profit

organizations is to maximize CLV. There are different models for estimating CLV depending on

the situation.11 We will discuss only the simple retention model (SRM) in this chapter to convey

the gist of how they are used in developing CRM strategies.

The Simple Retention Model for Lifetime Value

The SRM is used when there is a contract and the customer must signal the end of the

relationship. Prototypical examples are cell phones, Netflix, and cable TV. These are often called

gone for good situations because when customers stop paying they are assumed to be gone

forever. The alternative situation, which will not be covered here, is always a share, where

customer inactivity in a given period does not mean the customer is gone for good. For example,

retailers, airlines, hotels and not-for-profit organizations are examples of always a share.

The SRM assumes that customers enroll and generate net cash flows m at the beginning

of each period until they cancel. For example, a cell phone customer may generate net profit of

m=$50 each month. The SRM assumes that the probability a customer is retained in any month is

r, called the retention rate. Note that the SRM assumes a single retention rate for all customers

and periods, which may be unrealistic when contracts are involved, e.g., the retention rate may

be higher for customers during the first two years of a cell phone contract when they must pay a

penalty to leave than after two years, when there is no penalty. Likewise some customers may be

more intrinsically loyal than others. Despite the simplicity of these assumptions, the SRM is very

useful. Finally, assume that the period discount rate is d. Under these assumptions, the SRM

formula for lifetime value is as follows:

CLV=m(1+d )1+d−r

Continuing the cell phone example, if customers generate cash flows of m=$50 each

month, have a retention rate of r=.95, and a discount rate of d=1%, then CLV =

$50(1.01)/(1.01-.95) = $842. This informs how much can be spent to acquire a customer. It

would be foolish to spend $1000 to acquire this customer. Note that it would be smart to spend,

say $200, to acquire this customer even though the customer only generated $50 profit at the

time of enrollment. These calculations can also inform whether the cell phone company can give

the handset away for free.

The CLV formula has some important properties. It is plotted in the left panel below for

various retention rates, assuming m=$100 and d=1%. The curve is very steep for high retention

rates, but flat for low retention rates. CLV roughly doubles when the retention rate changes from

90% to 95%, and doubles again when the retention rate increases to 98%, and doubles again for

r=.995. Retaining customers longer pays large dividends when the retention rate is fairly high,

but increasing retention rates when it is low (say r=.5) has little effect on CLV. We can also

show that the expected number of payments is 1/(1 – r), so 10 payments are expected for r=.9, 20

for r=.95, and 100 for r=.99.

The right panel shows the CLV formula for different values of m, holding r=.98 and

d=1% fixed. The function increases linearly. For lower retention rates CLV is more sensitive to

changes in m, while for high retention rates it is more sensitive to changes in r. Cross selling and

upselling affect m, while other tactics affect r.

Figure 3: How CLV is affected by retention rates (left) and period cash flows (right)

Strategies for Increasing CLV

The second step is to set customer objectives and spending levels. CLV is especially

useful in this step. After identifying subsegments of customers, the next step in the process of

managing relationships is to specify objectives for each customer segment, which informs the

creation of contact points in the next step. The objectives should generally be to increase, or

at least maintain, CLV. We first consider existing customers, and later discuss acquiring new

ones and reactivating lapsed ones.

Another component of this second step is setting spending levels. The incremental

change in CLV informs how much money can be spent on a tactic. A marketing contact point

that costs $20 to increase a customer's CLV by $10 is not a good contact point. A contact costing

$20 that increases CLV by $100 is a good one.

Many writers on this subject simplistically advocate “investing more resources in your

best customers.” This bromide suggests that customer investments should be based on the

absolute value of a customer rather than the potential change in CLV due to an intervention.

Under this strategy, a firm should invest a $20 contact in a high-value customer with a CLV of

$1000 before investing the $20 contact in a customer with CLV = $100, but what if the $20

contact doubles the CLV of the low-value customer while having no effect on the high-value

customer? Of course, if not giving the $20 contact to the high-CLV customer causes the

customer to defect, changing CLV to 0, then the difference (increment) in CLV is great and the

high-CLV customer should get the contact. Incremental CLV should determine spending

levels, not absolute levels of CLV.

Increasing the Value of Existing Customers

There are three main ways to increase the CLV of existing customers: (1) retain them

longer, (2) increase customers' revenues, and (3) decrease the costs of serving them, marketing to

them, or both. Each is discussed in the subsections below.

Increasing Retention Rates

Different objectives will be applicable for different customer segments. In many

businesses the most effective way to increase CLV is to increase the retention rate. The previous

section showed how small increases in the retention rate can have a profound impact on CLV.

For example, consider a mobile phone provider who acquires customers and receives monthly

payments from customers until they cancel. We will show that increasing the monthly retention

rate from 94% to 97.5% will double CLV. Increasing it further to 99.25% doubles it again!

Thus, focusing on retaining existing customers longer can be a rewarding strategy. If the

objective is to increase retention rates, then the firm will try to understand what leads customers

to churn and develop contact points to avoid it. Of course, the cost of such contact points should

not exceed their incremental effect on CLV.

Increasing Revenues

The second way of increasing CLV for existing customers is to increase their revenues,

which is usually done by focusing on one of four approaches. Increasing revenues will affect m

in the SRM formula for CLV. The first is to increase the organization's share of wallet by getting

customers to purchase more with the focal firm instead of a competitor. Suppose, for example,

that a customer of an airline is spending about $5000 per year on airline tickets, but is splitting

the purchases equally across two carriers. One carrier can increase this customer's CLV by

shifting share. Airline loyalty programs offer strong incentives for travelers to concentrate their

purchases with one carrier with “points pressure.” Fliers want to reach the next tier of the

program so that they will receive special perks such as priority boarding and shorter security

queues. A customer who splits her miles with the two carriers might not fly enough to receive

perks from either airline, but if she consolidates her flights with one airline, she will clear the

“bar.” Mutual funds charge lower loads for customers who have invested more than some

amount, for example, a 5% rate for those who invest less than $100,000 and a 4% rate for those

above $100,000. This is another contact point used to achieve the objective of increasing share of

wallet.

A similar strategy is to cross-sell other products or services. A cell phone provider may

acquire a customer with a basic plan having a small number of minutes and no additional

services such as text messaging or Internet data. The provider might attempt to cross-sell

additional services, which would increase monthly revenues and CLV. Likewise, an online

retailer such as Amazon might attempt to cross-sell a book buyer other products in categories

such as music, toys or electronic devices. A cable TV provider could cross-sell Internet service

to its cable customers.

Revenues and CLV can also be increased by getting customers to buy higher-margin

products. This is often called up-selling. For example, if we can assume that margins are

constant across products then a wine store that can up-sell a customer from a $10 bottle of wine

to a $15 bottle will increase revenues. In many categories margins are smaller for the cheapest

products than for the intermediate and high-end versions, making the incentive for a firm to up-

sell even stronger. A cable TV provider could up-sell customer who have a slow Internet speed

to a package with higher speed and a larger data allowance.

The fourth approach to increasing revenues is to get customers to buy more often. For

example, if a computer company can get its loyal customers to buy a new laptop every two years

rather than every three years, CLV will increase. The same is true for many other electronic

devices and durables such as automobiles.

A fifth approach is to increase SOW. For example, airline loyalty programs are designed

to do increase SOW. Consider a customer who flies, say, 30,000 miles a year. If the customer is

loyal to one airline the customer will receive higher “status” in the loyalty program and extra

perks. If the customer splits the miles across carriers, she will not receive status or perks from

any carrier. Likewise mutual funds often have lower fees for customers who have more than

some threshold amount invested with the fund. A customer who splits investments across

different fund companies will not receive the price break. The price breaks and airline loyalty

programs are examples of contact points designed to increase SOW.

Reducing Costs

Organizations can also increase CLV by making customers less costly to serve. A famous

example from the United States is bank teller fees. Banks realized that they had a substantial

segment of customers who were not very profitable because they would visit the bank often and

make small withdrawals or deposits with tellers. Tellers are expensive because banks must pay

for their salaries and benefits, and because they must maintain branch locations. It would be

more cost effective to have customers in this subsegment using ATMs. Many banks announced

that they would charge low-profit customers—not all customers—a service fee for visiting the

teller, which would increase their CLV by making them less costly to serve. In a similar vein,

airlines and hotels commonly charge customers a fee to book a reservation over the phone, but

do not charge a service fee for using their website. The fee is a contact point designed to increase

CLV by reducing the cost of serving the customer.

An example of reducing the cost of serving the customer is when the Netflix movie

service announced a lower subscription price for people who will only download movies and not

use their mail service. Part of the reason is that it is expensive to “pick, pack, and ship” a DVD to

a customer, as well as pay for the return shipping, return the DVD to inventory, and account for

lost or damaged DVDs. Netflix does not realize any of these marginal service costs when a

customer streams a movie over the Internet. Another way to reduce the costs of serving a

customer is to get customers to consolidate orders. For example, a grocery delivery service

incurs a substantial cost to deliver an order. Customers who place larger, less-frequent orders are

therefore more profitable than customers who order the same items in small, frequent orders.

Finally, organizations can increase CLV by reducing marketing costs. A common way of

achieving this goal is to provide incentives for customer to sign up for longer contracts. For

example, magazines and other media organizations will try to sell a two-year subscription instead

of a one-year subscription because they will not have to spend marketing resources to keep the

subscription until the end of the second year. Likewise mobile phone providers want to sell

initial contracts that include substantial penalties for canceling within the first two years or so.

Having customers commit to longer contracts should also lower the discount rate because

positive future cash flows are more certain. A smaller discount rate also increases CLV in the

SRM formula.

Other Ways to increase value

Existing customers can also create value to an organization through referrals and word of

mouth. Cell phone providers routinely offer family plans as a way of generating referrals.

Similarly, product reviews written by customers can influence others. Referrals and reviews are

both examples of customer engagement value.12

Increasing the value of prospective or former customers

Our discussion has focused on existing customers, but the same logic of setting objectives

to increase CLV also applies to prospective and former customers. The obvious objective for a

prospective customer is to get the customer to buy for the first time, but this goal is often too

ambitious to achieve in a single step, and organizations might have greater success by breaking it

up into smaller sub-goals. For example, perhaps the first step in getting a customer to purchase is

to obtain the customer's permission to be marketed to. This would trigger a series of contacts

designed to educate the prospect about the organization's product and its value to the consumer.

The next step could be to get the prospect to visit the website for a virtual product experience.

There could be additional subgoals before trying to close the initial sale. Each of these subgoals

corresponds to a subsegment, and prospective customers migrate between subsegments over time

as the sub-goals are achieved.

A similar process applies to lapsed customers. The organization must understand why the

customer stopped purchasing before it can develop relevant contact points to bring the customer

back. A firm could use marketing research to develop a segmentation of lapsed customers based

on the reason why the customer has discontinued the service. In the case of contractual services,

this could lead to asking a question during the exit interview that classifies the canceling

customer into the subsegment, which would then determine which marketing contacts, if any, the

customer will receive in the future.

Creating and monitoring contact points

The third step of the integrated marketing process for increasing CLV in Figure 1 is to

create and manage contact points with customers. Contact points include those initiated by the

organization such as traditional advertising, sales promotion, and direct marketing, plus

responses to consumer-initiated contacts from websites and interactive media along with

participation in consumer-to-consumer and third-party dialogues. In addition, these interactions

also include points of contact that are not traditionally found under the “marketing function,”

such as customer service, technical support, retail distribution, websites, and the like.

We will not discuss the creation of such contact points, since this can be found elsewhere.

We will only discuss reactive contact points, which are not covered elsewhere in this book. A

key point is that the amount of money that can be spent on such tactics is informed by the change

that they will have on a customer's CLV. These decisions should not be made based on what

was spent last year, some percentage of sales, or any related heuristic.

Reactive marketing

For decades marketing was dominated by outbound, proactive, communications.

Companies generated brand messages and delivered them through a variety of media channels

such as TV, print, and direct mail. As new digital media emerged, marketers developed new

outbound advertising forms such as banner ads, pop-up ads, mobile poster ads, and email.

Outbound, proactive advertising will continue to exist, but big data sets that record the thoughts

and actions of customers in detail enables new forms of reactive marketing, where the firm can

listen to customer cues and respond appropriately.

A trigger event as “something that happens during a customer’s lifecycle that a company

can detect and portends the future behavior of the customer.”13 For example, when a credit card

customer stops using a card it could indicate that the customer has switched loyalty to another

card. When a customer of an Internet service provider (ISP) increases the amount of video

streaming and data usage it could indicate that the customer is cutting the cord, which suggests

an opportunity for the ISP. Companies can also respond to individuals complaining about the

service or product of a company, a phenomenon known as Webcare.14

Measuring the Effects of Advertising and Showing ROI

Measuring the effects of adverting efforts and their ROI is one of the most important

tasks that advertisers face. In the past, marketing and advertising have been viewed as an

expense by the financial officers of many firms, but there is a shift towards viewing them as an

investment in customers with a quantifiable financial return. Consequently, managers are

increasingly being required to show a return on marketing activities. At the same time, the

quality of data and the ability to measure the outcomes is improving. This section will discuss

good ways of measuring and proving such outcomes.

Use Controlled Tests with Matching/Blocking

The best way to measure the effect of some marketing effort is usually to use some sort

of controlled test. The idea is to give some customers—the treatment group—the new marketing

contact point (e.g., a new message or offer) and give others—the control group—the existing

marketing. We want the treatment and control groups to be identical in all ways except that one

gets the treatment (the new contact point) and the other does not. In this way we can isolate the

effects of the new contact point and get a true reading of its effectiveness. If the groups are not

identical then the results from the test are questionable. For example, suppose that those assigned

to the treatment group were better customers to begin with than those in the control group. Then

any observed difference in sales between the two groups could be due to the fact that those

receiving the new contact point were better to begin with, rather than the new contact point being

more effective. This is called a selection bias, which is said to confound the effects of the new

marketing. In this example customer quality is called a confounding variable because it is related

to both the treatment (better customers received the treatment) and to the outcome (sales).

The problem of designing a good test is even more complicated because not all customers

are the same. Some customers are better than others. Marketers call this heterogeneity. There are

several ways to address heterogeneity. The first approach is to randomly assign customers to the

treatment and control groups. While randomization is a good basic strategy, one problem with it

is that the treatment and control groups may not be equivalent because of bad luck. An example

will make this clear. Suppose that customers vary in purchase levels, with some great customers

and some weaker customers. If we randomly assign customers to treatment and control groups,

there is some chance that too many great customers will be assigned to one group and too many

weaker ones to the other. This is just like flipping a coin 10 times—we will probably not get

exactly 5 heads and 5 tails. When the groups are not equal we have the same problem that was

described earlier, where the effects of the treatment confound customer quality. Just as the

percentage of heads will get closer to 50% as we flip the coin more times, the chances of having

a disproportionate fraction of great customers in one of the two groups will decrease as the

sample size increases, but larger samples are more expensive.

A second way to address heterogeneity is called blocking. The idea is to form groups

(blocks) using the confounding variables. Continuing the example, suppose that we could

identify great, OK and weaker customers before we run the test, for example by looking at their

previous purchase history. We want to avoid having a disproportionate number of great

customers getting the treatment, and so we could randomly assign half of the great customers to

receive the new marketing and the other half to the control group. Likewise, we would randomly

assign half the OK customers to treatment and the other half to control, and do the same for

weaker customers. In doing so we will have insured that customer quality cannot confound the

treatment. We also reduce the cost of our test because we remove differences in customer quality

from the test. This process is summarized by those who design experiments with saying, “block

what you can, randomize what you can’t.”15 In other words, we want to block on confounding

variables that we can control, and then randomly assign customers within each block to treatment

and control.

The Problem with Historical Controls

The procedure discussed above involves having two groups of customers, with the

treatment group getting the new marketing and the control group getting the “business-as-usual”

existing marketing. Managers will often object to withholding the new marketing from the

control group. “If the new marketing really works better, then why would I want to lose money

by not giving it to all customers?” They will often suggest comparing sales under the new

marketing programs with sales under the old programs from a previous period. In other words,

monitor sales with the old marketing during the pre-period, implement the new programs, then

monitor sales on the same customers during the post-period. The difference in sales between the

post- and pre-periods is supposed to give the effect of the new marketing.

There are many potential problems with this approach, usually due to “something else”

happening between the pre- and post-periods. Suppose, for example, that the main competitor

was running a price promotion during the pre period, and changed the regular price during the

post period. When the competitor is charging a lower price, our sales probably go down, and

when the competitor’s price increases, our sales go up. Notice that the competitor’s price is a

confound because the change in sales between the two periods is affected by it rather than only

our new marketing program. Likewise, changes to the competitor’s marketing, the way products

are displayed in stores, etc. could also be confounds. In addition to competitive effects, store

sales can also be highly seasonal (e.g., the sale of steak sauce spikes around the 4th of July and in

summer) or affected by other external factors such as weather (e.g., beer sales go up when it is

hot outside and hot chocolate sells better in winter).

Sometimes we can adjust for these confounding variables with sophisticated time series

and regression models, but such models must make assumptions that may not be true. A failsafe

way of measuring effectiveness is to use the controlled-tests described above.

Measure Incremental Spend

The last question we will address is what to measure. It is always important to have the

right basis of comparison and quantify how the new marketing improves over the status quo. For

example, suppose we send out a promotion that drives people into physical stores. What is the

proper way to quantify the effects of such a promotion? Monitoring the sales of those who

received the promotion is not enough because some of them would have made purchases

anyway, e.g., due to their previous habits of shopping with you, exposure to mass advertising,

word of mouth, etc. A better way to isolate the effect of the promotion is to compare the sales to

those receiving it to the sales of a control group. It is the difference in sales (or percentage

increase) between the groups that gives the true effect of the promotion. If this difference is less

than the cost of the promotion, then the ROI is negative and the promotion is not effective.

Consider short- and long-term effects

Suppose that a clothing retailer sends out an offer that results in a sale for $50. Is the

value of the contact $50 (less the cost of goods sold, shipping, etc.)? The answer is no because

the $50 is only the short-term effect of the contact point.16 The sale also has a long-term benefit

that must be accounted for when deciding whether or not to make a contact point. In addition to

the $50 in revenue, the retailer received something else: the customer has become more loyal. To

see why, suppose that the customer was a one-time buyer who had been inactive for a full year.

After the order the customer has a frequency of two and is zero-months lapsed. As discussed in

the section on RFM, the probability of a future purchase increases for more recent customers or

as frequency increases. Thus, the customer will be more responsive to future contacts because of

the increased loyalty. The change in CLV is the log-term value of the contact and should be

considered when allocating resources.

What is Next?

Proliferation of Digital Environments and Big Data

Many aspects of the customer experience across many categories are increasingly

occurring in digital environments, where customer behaviors can be monitored and recorded in

detail. Such digital environments create “big data” sets. For example, social media environments

capture the interest of consumers and what they say and do with brands. Search engines record

search terms and clicks. Cookie files can link search and purchase actions across sessions and

websites. Mobile phones and wearables can capture the geographic locations of customers, their

mobile Internet activities, and perhaps other things such as heart rate. Weblogs record which

products or services are browsed, placed in shopping carts, and ultimately purchased or

abandoned. The Internet of things (IoT) refers to devices that are connected to each other via the

Internet. Many devices are equipped with sensors and monitoring devices that record produce

usage, and sometimes report back to the manufacturer. There are many examples, such as

automobiles, tractors, refrigerators, washing machines, and even vacuum cleaners. The

consumption of digital media products such as streamed movies can be monitored in great detail.

The rise of digital environments implies that more information will be available to CRM

systems. In addition to knowing RFM and some spotty demographics, organizations will

potentially have access to the sources mentioned above, and in the future data from other digital

environments that are sure to emerge. This means that organizations will have even better

information for targeting contacts at customer who are interested in the product or service,

creating personalized versions of contacts, and understanding customers in new ways. All of

these data sources provide the opportunity to detect trigger events. At the same time,

organizations will have to pay more attention to privacy and data security. There is a fine line

between impressing a customer with a highly personalized offer, and giving customers the

creepy sense that their privacy has been violated.

The Jigsaw Puzzle Problem

A common situation, which creates opportunities for both academic researchers and

advertisers, is what we will call the jigsaw puzzle problem: different data sets (puzzle pieces) are

being gathered by different parties, and each piece by itself has limited value. When the different

pieces can be brought together there is great potential value.

For example, Facebook and other social media sites record what its members say and do

on their site, giving a rich profile of what individuals value and who they are. Companies that

sell products or services directly to consumers have a detailed transaction history. In order to

measure the effectiveness of, for example, a Facebook ad, it would be ideal to join the Facebook

data with the transaction history. Social network sites as well as companies that sell goods or

services will be able to create new business by bringing these different data pieces together in

unique ways.

As a second example, consider a washing machine connected to the Internet and a retailer

such as Amazon that sells washing detergent. The washing machine manufacturer has

information about the number of loads per week a consumer does, but this information has

limited value to the manufacturer. Amazon knows which brand of detergent consumers use and

how much they buy. Bringing these two pieces of information together would have great value,

because Amazon could infer when an individual customer will be low on detergent (a trigger

event), which would prompt a contact point reminding the customer to replenish the supply.

Alternatively, we see how Amazon is attempting to bypass the jigsaw puzzle problem with its

new “Dash” button, which can be attached to a washing machine and connected to the

consumer’s wireless network. When the consumer presses, for example, the Tide Dash button,

the consumer will be sent a container of Tide.

As discussed above, having additional information on individual customers can improve

the personalization of advertisements and the targeting, where the advertiser decides whether or

not to invest resources in exposing a customer to an ad. By bringing together data sets,

personalization and targeting can be improved, enabling greater advertising efficiency.

A corollary is that there will be opportunities to create new products and revenue streams

from data. For example, organizations with customer lists have, for decades, rented them to other

organizations as a source of revenue. Any organization that gathers data should consider which

other organizations, possibly in completely different industries, might derive value from their

data. Likewise, academic researchers should be looking for ways to bring different data sources

together to address old and new questions in marketing.

Social CRM and Engagement

Traditional CRM implies that the organization is managing relationships with its

customers, and suggests that the organization has a substantial degree of control over the

relationship. The rise of social networking platforms and sites such as YouTube and Yelp mean

that the customer is no longer limited to a passive role in relationships with an organization. This

was indicated in Figure 1 by the arrows between customers in the center. Consumers now have

more information for making informed purchase decisions. They are no longer geographically

constrained and can purchase from companies around the globe. Searls (2013) even suggests that

instead of CRM, organizations should focus on understanding vendor relationship management

(VRM), where consumers are managing their relationships with vendors rather than the other

way around.17 Social CRM is “the integration of customer-facing activities, including processes,

systems and technologies with emergent social media applications to engage customers in

collaborative conversations and enhance consumer relationships.”18

Social media and customer empowerment have several implications for CRM. First, the

organization has a broader array of contact points available. In addition to traditional, outbound

communication such as TV ads, organizations can also create contact points that actively engage

consumers. We see many examples of these contact points, such as how Victorinox launched a

global storytelling platform where consumers write memorable stories about how its Swiss Army

knives played a crucial role in their lives. Customers are writing stories about the product, or

posting pictures or videos, which are seen by other customers.

Second, social media is a two-edged sword. Customers can create content that conveys

positive messages about a brand such as Victorinox, but they can also create negative messages

and distribute them to the world. There are many examples, with perhaps the most famous being

United Breaks Guitars. This leads to a potential problem with the exclusive focus on CLV

advocated earlier. CLV measures the value of the relationship to the firm, but not to the

customer. For the relationship to work, both sides must derive value. When customers are not

deriving value, or worse negative value, they can broadcast their dissatisfaction to a large

audience and damage the brand.19 This implies a dual optimization task: while the firm should, of

course, maximize CLV, it should simultaneously maximize the value customers receive from the

brand.

Conclusion

The CRM process prescribes that an organization should begin by identifying different

segments of customers, understanding their needs, and valuing them. Next it should decide on

strategies for increasing the CLV of customers in each segment and then create contact points.

The last step is to measure the outcomes from the contact points to determine whether the

contacts work and whether the customer has migrated to a different segment. This process is

repeated.

CRM is ideally suited for, and has long been practiced by, firms that maintain data on,

and directly target advertising at, individual customers. Some longtime users of CRM include

catalog companies, financial services, and travel (e.g., hotels and airlines). The fact that customer

interactions are increasingly taking place in digital environments (e.g., websites, mobile, social

media) where customer interactions can be recorded means that an increasing number of

companies will have access to customer-level data and therefore have a need for CRM thinking.

The New Advertising will require incorporating data into making advertising decisions,

executing programs and measuring their effectiveness. The CRM provides a systematic process

for using data effectively.

When John Deighton changed the name of the Journal of Direct Marketing to the Journal

of Interactive Marketing he gave the following justification: “the label direct marketing has

become too restrictive to do justice to the ideas that it has spawned. In a very real sense, direct

marketing has become too important and pervasive to be called direct marketing, since in the

information age, every marketer has the potential (and perhaps the responsibility!) to be a

database marketer.”20 Advertisers likewise have the responsibility to expand the scope of their

field to include data, customer segmentation, lifetime value and measurement, or risk becoming

irrelevant in the new digital marketplace.

Select Bibliography

Larivière, Bart, Herm Joosten, Edward C. Malthouse, Marcel van Birgelen, Pelin Aksoy, Werner

H. Kunz, and Ming-Hui Huang. "Value fusion: the blending of consumer and firm value

in the distinct context of mobile technologies and social media." Journal of Service

Management 24, no. 3 (2013): 268-293.

Malthouse, Edward C. Segmentation and lifetime value models using SAS. SAS Institute, 2013.

Malthouse, Edward C., Michael Haenlein, Bernd Skiera, Egbert Wege, and Michael Zhang.

"Managing customer relationships in the social media era: introducing the social CRM

house." Journal of Interactive Marketing 27, no. 4 (2013): 270-280.

Malthouse, Edward C., and Bobby J. Calder. "Relationship branding and CRM." Alice Tybout

and Tim Calkins. Kellogg on Branding. Wiley (2005): 150-168.

Author Biography

Edward C. Malthouse is the Theodore R and Annie Laurie Sills Professor of Integrated

Marketing Communications and Industrial Engineering at Northwestern University and the

Research Director for the Spiegel Center for Digital and Database Marketing. He was the co-

editor of the Journal of Interactive Marketing between 2005-2011. He earned his PhD in 1995 in

computational statistics from Northwestern University. His research interests center on

engagement, new media, customer lifetime value models, and predictive analytics.

1 Werner Reinartz, Manfred Krafft, and Wayne D. Hoyer, “The customer relationship management process: Its measurement and impact on performance,” Journal of marketing research 41, no. 3 (2004): 293-305.2 For further discussion of the relationship between the brand and CRM see Edward C. Malthouse, and Bobby J. Calder, “Relationship branding and CRM,” Alice Tybout and Tim Calkins. Kellogg on Branding. Wiley (2005): 150-168.3 Bobby J. Calder and Edward C. Malthouse, “Managing media and advertising change with integrated marketing,” Journal of Advertising Research 45, no. 04 (2005): 356-361.4 Edward C. Malthouse, and Kalyan Raman, “The geometric law of annual halving,” Journal of Interactive Marketing 27, no. 1 (2013): 28-35.5 Malthouse and Raman (2013).6 Bobby J. Calder, Edward C. Malthouse, and Ute Schaedel, “An experimental study of the relationship between online engagement and advertising effectiveness,” Journal of Interactive Marketing 23, no. 4 (2009): 321-331.7 Edward C. Malthouse, Srinath Gopalakrishna, Justin Lawrence, “Measuring and Managing the Customer Experience at Business Trade Shows: An Empirical Study,” MSI conference on engagement, Paris, 2015.8 Edward C. Malthouse, and Paul Wang, “Database segmentation using share of customer,” Journal of Database Marketing 6 (1999): 239-252.9 Timothy L Keiningham, Bruce Cooil, Edward C. Malthouse, Lerzan Aksoy, Arne De Keyser, and Bart Larivière, “Perceptions are Relative: An Examination of the Relationship between Relative Satisfaction Metrics and Share of Wallet,” Journal of Service Management (2014).10 Phillip E. Pfeifer, Mark E. Haskins, and Robert M. Conroy, “Customer lifetime value, customer profitability, and the treatment of acquisition spending,” Journal of Managerial Issues (2005): 11-25.11 For a survey of some useful CLV models and instructions on implementing them in statistical software see Edward C. Malthouse Segmentation and lifetime value models using SAS. SAS Institute, 2013.12 V. Kumar, Lerzan Aksoy, Bas Donkers, Rajkumar Venkatesan, Thorsten Wiesel and Sebastian Tillmanns, Journal of Service Research 13 (2010): 297-310.DOI: 10.1177/10946705103756.13 Edward C. Malthouse, “Mining for trigger events with survival analysis,” Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 15, no. 3 (2007): 383-402.14 Guda Van Noort and Lotte M. Willemsen, “Online damage control: The effects of proactive versus reactive webcare interventions in consumer-generated and brand-generated platforms,” Journal of Interactive Marketing 26, no. 3 (2012): 131-140.15 Dunlop, Dorothy D., and Ajit C. Tamhane. Statistics and data analysis: from elementary to intermediate. Prentice Hall, 2000, page 97.16 Edward C. Malthouse, “Accounting for the long-term effects of a marketing contact,” Expert Systems with Applications 37, no. 7 (2010): 4935-4940.17 Doc Searls, The intention economy: when customers take charge. Harvard Business Press, 2013.18 Kevin J. Trainor, James Mick Andzulis, Adam Rapp, and Raj Agnihotri, “Social media technology usage and customer relationship performance: A capabilities-based examination of social CRM,” Journal of Business Research 67, no. 6 (2014): 1201-1208.19 For discussion of how social media will affect CRM and how both customers and the organization must realize value see Edward C. Malthouse, Michael Haenlein, Bernd Skiera, Egbert Wege, and Michael Zhang, “Managing customer relationships in the social media era: introducing the social CRM house,” Journal of Interactive Marketing 27, no. 4 (2013): 270-280. Also see Larivière, Bart, Herm Joosten, Edward C. Malthouse, Marcel van Birgelen, Pelin Aksoy, Werner H. Kunz, and Ming-Hui Huang, “Value fusion: the blending of consumer and firm value in the distinct context of mobile technologies and social media,” Journal of Service Management 24, no. 3 (2013): 268-293.

20 Page 2, Deighton, John and Rashi Glazer. "From the Editors." Journal of Interactive Marketing 12, no. 1 (1998): 2-4.