Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal...

-

Upload

malion-hoxhallari -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

0

Transcript of Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal...

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

1/16

Centre for Albanian Studies

Institute of Archaeology

PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS

OF ALBANIAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES

65th Anniversary of Albanian Archaeology

(21-22 November, Tirana 2013)

Botimet Albanologjike

Tiranë 2014

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

2/16

Copyright© 2014 by Centre for Albanian Studies and Institute of Archaeology.

All rights reserved. No parts of this volume may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the

Albanian Institute of Archaeology.

ISBN: 978-9928-141-28-6

Editorial board:

English translation and editing:

Nevila M

Art Design:

Gjergji I and Ana P

PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF ALBANIAN

ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES

65th Anniversary of Albanian Archaeology (21-22 November, Tirana 2013)

Professor Luan PËRZHITA (Director of Institute of Archaeology),

Professor Ilir G JIPAL(Head of Department of Prehistory),

Professor Gëzim HOXHA (Department of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages),

Associate Professor BelisaMUKA (Head of Department of Antiquity)

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

3/16

93

LITHICS AT ONE END OF THE

CIRCUM-ADRIATIC: CASE STUDIES FROM THE

SOUTHERNMOST ALBANIAN COASTAL LOWLAND

Rudenc RUKA, Ilir GJIPALI, Michael L. GALATY and Novruz BAJRAMAJ

Prehistoric research in Albania has producedconsiderable evidence for settlement in the hinterlands,but very little for settlement in the Adriatic lowlands,producing only a partial picture of Albanianprehistory1. For this reason, newly-discovered surfacefinds from west of Narta Lagoon, composed of

numerous lithics, are crucial to developing a morecomplete understanding of this particularly dynamic,coastal landscape.

The hill ridge2 from which the lithicswere collected is north of Vlora, situated in thesouthernmost part of the coastal area of Albania’swestern lowland3. It is comprised of a series of lowhills, oriented almost northwest-southeast, extending4.6 km, with a maximum height of 78 m a.s.l. Thehills are situated between the Narta syncline, which tothe west forms part of the Narta Lagoon, and the sea4.The ridge is an asymmetric anticline5, aligned alonga hidden fault line, and was most probably shaped bytectonic uplift. The western side of the ridge is markedby an abrupt slope that is being continuously abradedby the sea, while the eastern side presents a gradualslope that underlies recent low altitude Holocenemarsh deposits and Vjosa river alluvial deposits6. Thelow hills that comprise the ridge are made of sandyNeogene molasses of the Middle Miocene series ofthe Serravallian stage7. The ridge is fragmented bya series of depressions that toward the shore usually

form narrow sand beaches or sand banks between thesea and the lagoon.

This particular ridge was first noted for itsarchaeological remains by Panayiotis Aravandinos(Παναγιώτης Αραβαντινός ) in the mid 19th century,who described the presence of an acropolis in the bay

of Porto Nov near the coastal village of Palea Arta(nowadays Narta) in the area of Vlora. It was suggestedthat the acropolis was a remnant of ancient Arnisa8. Infact, later archaeological observations indicate that theacropolis is in fact situated on the southernmost hill ofPllaka, near its south-western cape, at Treport9. Theonly prehistoric artefacts noted by these pre-WWII visiting archaeologists were a couple of Mycenaeanpottery sherds of Late Helladic III date10. Systematicexcavations and studies undertaken at the site duringthe 70s and 80s identified Late Bronze Age-Early Iron Age activity, alongside evidence for settlement duringantique times through the 2nd century AD11. However,no reference was made at this point to the presence ofearlier prehistoric remains on the ridge.

The first two sites, named Putanja and Dalanii Vogël, are situated immediately north of Treport.They were first identified in 2009 by local amateurcollectors, who brought them to the attention ofarchaeologists, noting the considerable number oflithics there, and some pottery as well. Further non-systematic archaeological survey work in 2011-2012

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

4/16

94

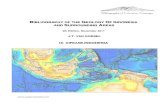

brought about the discovery of three more sites,Portonov I and II and Kepi i Dajlanit (Fig.1), along the

ridge toward its northern extremity.It is not clear at this point how many

lithics have been acquired over the years by theamateur collectors, but some of them have beenturned over to representatives from the Institute of Archaeology. Together with materials collected laterby archaeologists, there are ca. 1244 pieces availablefor study. Unfortunately, many of the finds were mixedbetween sites. Henceforth, the mixed materials fromthe entire ridge will be discussed together and, wherepossible, separately, with reference to each location.

Overall, 483 pieces without site-specificinformation were recovered from amateur collectors.We primarily acquired diagnostic pieces or those thatseemed to show some level of retouch or technologicalinformation. Approximately 70 pieces can be describedas flakes and debris of non-diagnostic value, while therest varies, and can be assigned to one or, sometimes,multiple periods. The oldest identified period is theMiddle Palaeolithic (Fig. 2, 3) and it is representedby: 1) Levallois cores (N=25) that are mostly onflakes detached from round pebbles, 2) Levalloispreparation flakes (N=18), 3) Levallois flakes (N=21)

that range from preferential flakes to blades and short,broad-based points, 4) tools on Levallois products

Fig. 1. Map of sites’ locations.

(N=24), such as side scrapers, double scrapers, dejete,Mousterian points, convergent scrapers with Quinaand semi-Quina retouch, 4) transverse scrapers (N=3),5) a Kombewa flake (N=1), 6) a denticulate (N=1), and7) discoidal cores (N=2). A number of tools (N=57),mostly side scrapers, double side scrapers, convergentscrapers, points, and retouched blades, could becategorised both in the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic.With regard to the latter, of certain Aurignacian date(Fig. 4) are: 1) carinated cores (N=11) with asymmetricworking faces that would have produced twistedmicroblades, 2) rejuvenation flakes (N=2), removedto maintain the lateral convexity of the working faceof carinated cores, 3) nosed, shouldered, and thickend scrapers (N=13) and 4) possibly a strangled blade(N=1).The Epigravettian (Fig. 5) is most probably represented

Fig. 2. Middle Palaeolithic Levallois cores from the generalhill ridge area.

Rudenc RUKA, Ilir GJIPALI, Michael L. GALATY and Novruz BAJRAMAJ

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

5/16

95

Fig. 3. Middle Palaeolithic tools (1. Convergent scraper; 2, 3,5. Dejete; 4. Transversal scraper) and Levallois products (6-10.

Levallois products) from the general hill ridge area.

by: 1) opposed platform laminar cores (N=2), 2)fragments of micro/Gravette points (N=2), and 3) anarched backed piece on a blade (N=1).

Nonetheless, a number of other pieces couldbe assigned to various post-Middle Palaeolithicperiods but with a higher probability that they areEpigravettian, Mesolithic, or from later periods (Fig.6): 1) laminar cores (N=27), 2) burins or burin spalls(N=12), 3) truncations (N=11), 4) oblique truncated orbacked pieces (N=5), 5) crested blades (N=3), 6) piècesesquillées or splintered pieces (N=3), 7) a microblade(N=1), and 8) end scrapers (N=10), of which onemight show signs of bitumen used as adhesive atthe proximal end. A number of lithics could be of

Fig. 4 Aurignacian cores (1-5 carinated cores) and tools(6-11. thick, shouldered and nosed end scrapers) fromthe general hill ridge area.

Neolithic, Eneolithic or even later age (Fig. 5), suchas: 1) tanged point fragments (N=2) with light retouchapplied by surface pressure flaking, 2) a bifacialpreform (N=1), and 3) a medial blade fragment (N=1)with silica shine. Putanja (19 23’52.6”E, 40 30’30”N) is the firstsite from south to north and is situated in a depressionthat is relatively large and flat between the hill of Pllakaand the next hill to the north. Despite a relatively lesssteep slope on the eastern side, it still presents thegeneral characteristics of an asymmetric anticline.The lithic concentration is more obvious at the highest

LITHICS AT ONE END OF THE CIRCUM-ADRIATIC: CASE STUDIES FROM THE SOUTHERNMOST ALBANIAN COASTAL LOWLAND

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

6/16

96

Fig. 5. Epigravettian cores (10-11. bidirectional cores)and tools (3.end scraper, 4-5 arched backed microliths,

5-6. probably double backed micro/Gravette points); Neolithic, Eneolithic or later age (1. end scraper, 2.

sickle element, 7, 9. tanged points’ fragments, 8. preform) from the general hill ridge area.

Fig. 6. Epigravettian, Mesolithic, or later periods (1-4.truncations, 5-11 burins and burin spalls, 12-14splintered pieces) from the general hill ridge area.

point toward the southern end of the depression andimmediately below on the sandy beach, as exposed bysea abrasion. The number of lithics collected at thesite amounts to ca. 330 pieces, of which 250 includegeneral debitage such as flakes, blades, chips, chunks,and debris of no particular diagnostic value. Overallthe lithic pieces seem to be well preserved, fresh, withrare edge damage or rounding, unless they had beenrolled by beach wave action. The raw materials camein the form of river cobbles of high quality flint. In thecollection, one can recognize at least three components(Fig. 7): the Middle Palaeolithic, Epigravettian, and

one of later Holocene age.

The Middle Palaeolithic component isrepresented by ca. 29 pieces: 1) Levallois flakes (N=20),2) side scrapers (N=3), 3) a Levallois preferential core(N=1), 4) Levallois recurrent centripetal cores (N=2),4) discoidal pseudo-Levallois points (N=2), and 5)discoidal cores (N=2). The Epigravettian componentprobably contains more than 30 pieces. Worth notingare:1) abruptly retouched pieces (N=11), such asbacked bladelets (N=2), a trapeze (N=1) that seems tohave been produced with the microburin technique, anarched backed blade (N=1), an obliquely bi-truncatedblade (N=1) resembling in outline an arched backedpiece, and an obliquely truncated distal blade fragment(N=1), 2) burins (N=4), 3) microblades (N=3), and 4)a microblade core (N=1). So far none of the tools on

Rudenc RUKA, Ilir GJIPALI, Michael L. GALATY and Novruz BAJRAMAJ

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

7/16

97

laminar pieces presents the regular parallel dorsalridges of the Mesolithic period and the presence ofthe burins during this period is not a common feature.Nevertheless, the presence of the geometric microlithsis a feature of both periods and the arched backedpieces can be assigned to both the Uluzzian and theEpigravettian. The third component is represented by onethin obsidian medial fragment with regular paralleldorsal ridges that indicate the use of indirect percussionor pressure flaking. The piece was analyzed with aportable x-ray fluorescence spectrometer (PXRF),which is a non-destructive technology that allows rapidcollection of statistically robust data. We used a BrukerIII-SD, with filter (12 mm Al, 1 mm Ti, 6 mm Cu),set to40 kV and 33 µA,to undertake trace-elementanalysis. The artefact had been cleaned and analysiswas undertaken on a flat surface for 300 seconds. Theresulting data were calibrated and transformed intoparts per million (PPM) measurements using shared

Fig. 7. Middle Palaeolithic (9-11, 13-15. Levallois flakes andtools) and Epigravettian (1. dihedral burin and end scraper,

2, 3, 5. micro blades, 4. backed bladelet, 6. 7. arched backed pieces, 12. dihedral burin dejete) from Putanja.

obsidian standards (Tab. 1). These measurements werecompared to known values for various Mediterranean

sources (e.g., the Italian and Greek sources), which areeasily discriminated using just a few trace elements,especially as ratios.

Putanja Concentration

MnKa1 419.608094

FeKa1 11,552.30

ZnKa1 49.42551234

GaKa1 20.78838198

ThLa1 41.03718035

RbKa1 292.2229199

SrKa1 12.29648485

Y Ka1 46.18339711

ZrKa1 175.5858774

NbKa1 35.80070655

RhKa1 0

Tab. 1: PPM concentrations for 11 trace elements in thePutanja obsidian artefact.

PXRF results indicate that the Putanja artefact

is not from Melos in Greece, rather it is from Lipari inItaly.12 The Putanja obsidian is too high in iron andrubidium to be from either of the Melian sources. It is,however, a perfect match for Lipari. The Lipari sourceswere not available and exploited by humans untilafter 6000 BC13, so the Putanja artefact cannot dateto the Mesolithic. According to Tykot14, the “zenith”of central Mediterranean obsidian distribution wasduring the Early and Middle Neolithic, tapering off inthe Late Neolithic. It is thus possible that the Putanjasite dates to the Neolithic. Lipari obsidian continuedin use through the Copper, Bronze, and Iron Ages, soa post-Neolithic date is also conceivable.

Another piece of obsidian from Lipari andof Mesolithic date has been identified based onmacroscopic observations from the site of Tsarlambasalong the Epirote coast in the area of Preveza15. Theuncertainty regarding the origin and, most probably,the age of this piece16, however, makes the Putanjaobsidian artefact the southernmost, securely-identifiedpiece of Lipari obsidian along the Adriatic-Ioniancoast. The other group of Lipari finds from the eastern

LITHICS AT ONE END OF THE CIRCUM-ADRIATIC: CASE STUDIES FROM THE SOUTHERNMOST ALBANIAN COASTAL LOWLAND

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

8/16

98

Adriatic is concentrated on the route connecting theislands of Palagruza, Susac, and Korcula to various

points along the middle Dalmatian coast17.Given thedistances between this area of the Dalmatian coastand the area of Vlora and of the latter to southernItaly, we can infer direct contact between Vlora andPuglia.

Dalani i Vogël (19 23’40.8”E, 40 30’52”N)represents the second site along the ridge toward thenorth. It is situated in a depression between two hills.The site was exposed both by the excavation duringthe communist period of a channel that connectsthe Narta lagoon with the sea and by sea abrasionon the western side of the depression. The lithics areconcentrated on the northern side of the depressionalong the channel, the beach, and in nearby areas.

Fig. 8. Middle Palaelithic (9. side scraper, 10, 15. Mousterian point, 11. Levallois point, 12. Levallois

preparation flake, 13-14. dejete), Aurignacian (3, twistedmicroblade, 7. microblade core), Epigravettian (1. end

scraper, burin on truncation, 4. microblade, 8, microbladecore), Middle Neolithic to Bronze Age (6. obsidian

bladelet/microblade core) from Dalani i Vogël.

The number of lithics collected at the site amounts to322 pieces. This particular location seems to provide

the most complex chronological sequence identified sofar along the ridge (Fig. 8).

This is partly demonstrated by the clear presenceof stratigraphic layers that contain finds of MiddlePalaeolithic, Mesolithic, and Early Neolithicsettlement, with impressed pottery (Fig. 9), and possiblyeven Bronze Age materials.

The Middle Palaeolithic is represented by 32 pieces:1) Levallois cores (N=11), mostly produced on pebbleflakes that are largely cortical on the lower face, 2) aKombewa flake (N=1), 3) Mousterian points (N=5),4) side scrapers (N=6), 5) a transverse scraper (N=1),6) Levallois and centripetal dorsal scar pattern flakes(N=8), and 7) a discoidal pseudo-Levallois point (N=1).The post Middle Palaeolithic materials are representedby a variety of cores, tools, and technological pieces thatcould be categorised variably from Upper Paleolithicto Bronze Age. However, a number of finds could bedefined more closely within two consecutive periods.

Fig. 9. Early Neolithic impressed pottery from Dalani i Vogël.

Rudenc RUKA, Ilir GJIPALI, Michael L. GALATY and Novruz BAJRAMAJ

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

9/16

99

Of 7 bladelet/microblade cores, two of them could becategorised in the Aurignacian due to the asymmetry

of their working surfaces, which would have producedmostly twisted microblades. A distal fragment of atwisted microblade and a rejuvenation flake withmicroblade dorsal scars detached to maintain thelateral working surface convexity could also dateto this period. The rest of the bladelet/microbladecores could fit well into Epigravettian and Mesolithicperiods. Despite the lack of clear bidirectional cores,two tools of Epigravettian type could be distinguished:a burin on a concave distal blade truncation and aretouched blade with a round and steeply retouchedend scraper. The Mesolithic period is represented byone diagnostic piece or segment discovered along thechannel. The direction of the abrupt retouch changesalong each half of the arch. The dorsal ridges areregular and parallel, indicating an indirect or pressureflaking technique for the production of the blank. Thelack of trapezes in the assemblage and the general useof segments during the early stages of the Mesolithicwould probably indicate a Souveterrian date. Apost 8200 BP phase of the Early Neolithic can besuggested by the presence of stray finds of impressedpottery. In terms of lithic finds, this period is probably

represented by only one diagnostic piece, an inverselyretouched distal blade fragment and burin on a convexend scraper. The regular and parallel ridges as wellas the thin trapeze section of the piece indicate sucha date. Of probable Middle Neolithic to Bronze Agedate is an obsidian bladelet/microblade core fragmentthat based on macroscopic observations seems to beof Melian origin.18 The movement of Melian obsidianalong maritime routes begins circa 10,900–10,800BC, as demonstrated by obsidian finds from Franchthicave in the Argolid19. The closest group of claimedfinds of Melian origin in northwestern Greece is fromthe Ionian islands of Lefkada, Kefalonia, Ithaka,and Zakynthos, which are dated to the differentchronological sub-periods of the Bronze Age and arethought to have been transported via sea routes20.Nevertheless, obsidian of the Greek Late Neolithic inthe same area has also been found21. Circa 51 pieceswith some technological information, core and corefragments, tool fragments, and end scrapers could beassigned to a number of different periods. The rest ofthe assemblage is comprised of 196 pieces of debitage,

including flakes, laminar products, chips, chunks, anddebris of no particular diagnostic value.

Porto Nov I (19 23’23.8”E, 40 31’06.5”N)presents the third site along the ridge towards thenorth. It is situated in a depression between the hills ofPorto Nov. Most of the finds were collected at the beachbelow the surface that is being continually abraded bythe sea as well as on the western flat surface of thenorth-south slope of the depression. The number oflithics collected at this site amounts to 60 pieces. Atleast three chronological phases can be distinguishedhere, the Middle Palaeolithic, Early Neolithic, andEneolithic-Bronze Age (Fig. 10).The Middle Palaeolithic is represented by 10 pieces: 1)Levallois preferential cores (N=2) produced on pebbleflakes which still retain considerable cortical surfaceson the lower faces, 2) a centripetal core (N=1) on apebble flake, 3) Levallois flakes (N=3), 4) a flake withcentripetal dorsal scar pattern (N=1), 5) a discoidal

Fig. 10. Middle Palaeolithic (7-8. Levallois cores, 1, 4.Levallois flakes), Early Neolithic (6. impressed pottery

fragment), and Eneolithic-Bronze Age (5. proximal blade fragment) from Porto Nov I.

LITHICS AT ONE END OF THE CIRCUM-ADRIATIC: CASE STUDIES FROM THE SOUTHERNMOST ALBANIAN COASTAL LOWLAND

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

10/16

100

core fragment (N=1), and 6) discoidal flakes (N=2).The Neolithic period is indicated by the presence of

one impressed pottery sherd that is generally datedafter the 8200 BP event22 and as many as seven lithics.In this chronological phase could be included twocores of which one is a blade/microblade on a narrowface and the other a bladelet and flake core, five bladesand blade fragments and one distal fragment of an endscraper on a large blade. It must be noted, though, thatsome of the pieces could also be categorised in earlieror later periods due to their imprecise chronologicalattributes but the presence of the pottery sherd suggestswith a high degree of probability the Neolithic period.The last phase is represented by only one piece whichcan be assigned to the Eneolithic-Bronze Age periods.It is a retouched proximal fragment of a large bladeproduced by pressure flaking, most probably withmode 5 or lever pressure23. The retouch is flat, long,and parallel to sub-parallel due to the application ofa pressure technique which generally occurs mostlyduring the Eneolithic and Bronze Age in Albania24.The rest of the assemblage contains a complex notchon a distal fragment, flakes, chunks and debris of noparticular diagnostic value.

Porto Nov II (19 23’15.8”E, 40 31’14.7”N)

represents the fourth site along the ridge towardsthe north. It is situated in a depression between thehills of Porto Nov. Most of the finds were collected atthe beach below the section that is being continuallyabraded by the sea as well as on the surface of thedepression toward the sea. A total of 23 pieces wascollected at the site, which are categorised into atleast three chronological phases. The oldest phaseor the Middle Palaeolithic is represented by at leastfour diagnostic pieces: a preferential Levallois coreproduced on a cortical flake, a proximal fragment of arelatively flat Levallois flake with faceted butt, a smallLevallois flake with centripetal dorsal scar patternand a possible discoidal flake. The later phases arepresented by 5 pieces: 1) a burin on a large and thicklaminar core tablet. On the ventral side there is oneKombewa-like detachment and the burin blow hasbeen produced distally on what seems like a naturalsurface, 2) an obliquely truncated flake that has beenproduced with a soft hammer on a faceted butt, 3) acore with two crossed working surfaces, one used forthe production of bladeletes and microblades and theother for flakes and microblades, 4) a unidirectional

blade and microblade core with one working surface,and 5) a pressure-flaked blade, probably made with a

copper-tipped tool, in mode 4 according Pelegrin25.These pieces seem to range in date from the UpperPalaeolithic to the Eneolithic-Bronze Age. The rest ofthe finds are mostly flakes and flake fragments of noparticular diagnostic value.

Kepi i Dalanit (19 22’47.8”E, 40 32’13”N) isthe fifth and the last identified site in the area, closeto the northern extremity of the ridge. The lithicconcentration is situated on a gradual hill slope onthe northern side of the depression. A total of 26lithics was collected at the site, which are categorisedchronologically to the Middle and Upper Palaeolithicand another, later phase of the Holocene (Neolithic-Bronze Age) (Fig. 11).

The Middle Palaeolithic is represented by 7 pieces:1) a Levallois preferential core (N=1), 2) Levalloispreferential flakes (N=5), and 3) a discoidal corefragment (N=1). The Upper Palaeolithic is representedby at least two pieces, a prismatic core and a backedpiece. The core is a unidirectional blade/let core ofhoney-brown flint, which has been exploited along itswhole perimeter. The core shows at least two stages

of use and during the second stage was probablyrecycled. During the first stage the core was used forthe production of blades, though not all along theperimeter of the platform due to the presence of alongitudinal cortical ridge. During the second stage,after the platform rejuvenation and crest preparation,the core was exploited along two opposing sidesfollowing the platform perimeter for the productionof bladelets. The platform was rejuvenated, mainlyby the detachment of two bidirectional partial coretablets on the sides of the original crest. The distal crestpreparation scars are superimposed on earlier bladedetachments that are also missing the bulb scars dueto platform rejuvenation. Most probably the remnantof the cortical ridge was used as a second natural crestfor the initiation of the core opposite to the crest. Thesecond piece is a blade with crossed backing. A thirdphase, most probably of Holocenic age (Neolithic-Bronze Age), is represented by a medial fragment of ablade with regular parallel ridges produced by eitherindirect percussion or pressure flaking. The bladewas retouched, patinated, and then bilaterally andabruptly retouched toward the distal end. The rest of

Rudenc RUKA, Ilir GJIPALI, Michael L. GALATY and Novruz BAJRAMAJ

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

11/16

101

Fig. 11. Middle Palaeolithic(10. Levallois core, 5-9Levallois flakes), UpperPalaeolithic (1. prismatic

core) from Kepi i Dajlanit, Neolithic-Bronze Age (4.medial blade fragment) fromKepi i Dajlanit.

the assemblage is comprised of 4 non-diagnostic tools,of which one has been recycled, and 12 flakes or flakefragments.

Generally speaking, the raw materials used atall locations derive from secondary geological sources,most probably from the aforementioned alluvialdeposits of the Vjosa River. Of particular note is thecommon use of large pebble flakes for the preparationof the Levallois cores during the Middle Palaeolithic.Furthermore, despite the significant presence of honey-brown flint in the assemblages, the high degree of rawmaterial variation indicates collection from alluvialdeposits. Unmodified river pebbles were noted at mostof the sites but it is not clear at this point whether riverdeposits were accessible during all periods. Conversely,the discovery of tabular flint intentionally broughtto the area points toward other sources. The closest

primary geological sources of flint would have been atleast some 10 km away around Kanina, as indicatedby the successful production of gun flints there duringthe mid 19th and early 20th century26. Even though noanalysis has been undertaken so far to identify theorigin of the tabular flint, its presence may indicatethat the landscape around the hill ridge changedthrough time and that in certain periods river depositswere not accessible. In fact, the ridge’s surroundingenvironment during prehistory would have passedthrough three major transformations that are mostlyrelated to relative change in seal level.

During the first phase, or the Late Pleistocene,the ridge would have been a dominant locationoverlooking a large plain that would have extendedmore than 20 km to the west27. We can assume that thearea would have been used as a seasonal hunting ground

LITHICS AT ONE END OF THE CIRCUM-ADRIATIC: CASE STUDIES FROM THE SOUTHERNMOST ALBANIAN COASTAL LOWLAND

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

12/16

102

when migratory animal herds used the plain for winterpasture. So far the surface collected lithic assemblages

in southwest Albania show a clear trend in the use ofriver valleys to access the highlands. Palaeolithic siteshave been mapped close to the Vjosa River valley inthe Fier and Mallakastra regions at Kryegjata A, B, C,D, Kraps, Rusinja, and Peshtan28, at Mogilat e Vasjarit,Luadhi, and Lajthi near Tepelena, at highland sitessuch as Fusha e Çajupit and Dërmaz29 in Gjirokastra,as wells as in the Pindos mountains30 in Greece. Whilethis idea had been suggested already by Runnels et al.31,it is only now given these more recent discoveries thatwe can demonstrate intense levels of human activity allalong the route of the Vjosa River. Given the currentstate of research, the Vjosa River valley presents thebest case of lithic survey work in Albania. Future workneeds to focus on a more tangible body of data derivedfrom systematic excavations in order to reconstructseasonality patterns. The ridge could be such a case,used to document the westernmost extremity of year-round, seasonal Late Pleistocene human activity.

During the second phase, the post Last GlacialMaximum, progressive sea-level rise would havebrought prehistoric communities into a much closercontact with the sea and its resources. Beginning in the

Early Neolithic the area would have served not just as awinter base for transhumance but also a location wherecultivation and fishing would have been possible. Ofcertain importance would have been its intermediateposition along trading routes that connected thewider Mediterranean world. This is indicated by thepresence of obsidian from both Lipari and, perhaps,Melos. In return, the locally available honey-brownflint could have been traded. A number of authorshave pointed to Bulgaria as the place of origin forhoney-brown flint32 both in Greece33 and Albania34.

Kourtessi-Philippakis, though, suggests a north-south exchange route due to the presence of honey

flint in Thrace and eastern and central Macedoniaand its absence from the Neolithic settlements ofwestern Macedonia35. Perlès, however, has indicatedthe possible presence of this type of raw materialin the Peloponnesus, originating from northwestGreece, and south Albania36. The significant quantityof this raw material at the hill ridge, its presence inarchaeological contexts in the Peloponnesus37 as wellas the aforementioned movement of obsidian alongthe Ionian coast raise the possibility that sites alongthe Albanian coast served as transshipment points forhoney flint and other products being moved south toGreece.

The third phase is characterised by rising sealevels, culminating in the Holocene TransgressionMaximum, and the possible transformation ofthe ridge into an island. This is indicated by thegeomorphological work undertaken in the vicinity,centred on the ancient city of Apollonia38. Accordingly,the ridge would have been reconnected to the land bya series of sandbars toward the end of the Iron Age.Recent work from the area of Lezha suggests a similarsituation for Rrenci Mountain and its reconnection

to the mainland39. During the Late Bronze Age-EarlyIron Age, the island’s Pllaka hilltop was occupied,with open access to the sea and maritime trade routes.Free access to the sea and sea trade is indicated bythe presence of possibly Late Helladic III40 potterysherds, and remained so until the construction ofthe first fortification wall in 520-490 BC41. Based onthe archaeological evidence and given similar geo-environmental settings, we could apply the samemodel of coastal evolution to the sites of Himara cave(Himara)42 and Bishti i Pallës (Durrës)43. At Himara

Tab. 2. Chronology of the sites.

Rudenc RUKA, Ilir GJIPALI, Michael L. GALATY and Novruz BAJRAMAJ

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

13/16

103

cave the lower stratigraphic layers may have beenremoved by the rising sea, until about1440 to1280 cal

BC. But at Bishti i Pallës, the probable island was usedduring the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age untilit was connected to the mainland when an Archaicsanctuary was built.

In this article we have provided a summary ofthe preliminary data collected thus far at this particularspot at the southernmost end of the Adriatic lowlands. At the same time, we have also constructed a generalchronological framework (Tab. 2) for prehistorichuman adaptation to coastal environmental changesin Albania. During the Late Pleistocene, the ridge andthe wider Narta region most probably acted as oneterminus of a hunter-gatherer seasonal round focusedon migratory animals that spanned the mountainstowards Greece. In later phases there was interactionwith the wider Mediterranean world in the form oftrade. This interaction flowed in at least two directions,toward southern Italy and Greece. This area mayhave attracted continuous activity as an intermediarybetween hinterland sites and overseas partners. Eventhough the resolution of the data still remains coarsegrained, future work should shed new light on thedetails of human adaptation to this dynamic coastal

environment.

NOTES

LITHICS AT ONE END OF THE CIRCUM-ADRIATIC: CASE STUDIES FROM THE SOUTHERNMOST ALBANIAN COASTAL LOWLAND

1 L and G 2009: 106.

2 Present-day maps do not assign a name to this

particular ridge, but it was called Cavalloni on late 17th century Venetian maps (Giusto Emilio Cartographe Gra-

veur Alberghetti, “Il Golfo della Valona : con una parte

delle Dipendenze di Canina, Ultime Conquiste fatte

nell’Albania da ... Girolamo Cornaro / Giusto Emilio Alberghetti” ([s.n.] (Venetia), 1690).). We avoid the use of

this place name due to the fact that it might be misleading,

as in the present time the place names Pusi i Kavalonës

and Pylli i Kavalonës are used immediately south of theridge in the flat area toward the city of Vlora.

3 K et al . 1991: 431–432.

4 Ibid .: 433.

5 Ibid .: 488–489.6 F et al . 2010: 120.

7 X et al . 2002.

8 ΑΡΑΒΑΝΤΙΝΟΎ ΠΑΡΓΕΊΟΥ 1857: 121–122.

9 P1904: 63; U 1927: 107;H 1967: 131–133.

10 H 1967: 133.11 B 1977-1978: 285–92; 1985: 313–20; 1986:258; 1988: 105–19; 1992: 129–47; 1993: 143–59; 1999

181–85.

12 We thank Ms. Danielle Riebe (University of Illi-

nois, Chicago) and Dr. Robert Tykot (University of SouthFlorida) for helping us make these determinations. We are

working on a longer article with Riebe and Tykot which

will address obsidian distribution in Albania generally

based on additional PXRF analyses of other artefacts.13 B 2013: 215.

14 T1996: 67.

15 W and Z 2003: 118, 131, 134.

16 Ibid.: 121.17 T 2004: 32.

18 We have not yet analyzed this piece using PXRF,

but hope to do so in the near future.

19 B 2006: 208.20 S-H 1999: 17, 25, 30, 34,

39, 45, 47, 96–97, 100, 121–122.

21 Ibid.: 7, 47.22 B and G 2009: 34.23 P 2012: 479, 488.

24 P and B 2008: Tab. II, 13; 2014:Tab. CXVIII; K-P 2002: 79; 2010: 175,

178.

25 P 2012: 286–290.26 Exposition Universelle de 1867 à Paris: Catalogue gé-

néral: Produits (bruts et ouvrés) des industries exractives (Groupe

V. - Classes 40 à 46.), vol. 5 (Paris: E. D, 1867), 234;

G 1914: 157–158.

27 F 2002: 5.28 R et al . 2004: 3–29; R et al . 2009:

151–82.

29 G, 2012: 154.

30 E et al . 2006: 422–424.

31 R et al. 2009: 176.

32 G 2008: 120–122; 2012: 15–49.33 K-P 2009: 309.

34 R et al . 2004: 13.

35 K-P 2009: 309.

36 P 2004: 158; 2012: 542.

37 P 2004:158; P and C

2010:4–5.38 F 2002: 19; 2007: 8; F et al. 2010127; S 2010: 774.

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

14/16

104

39 U 2012: 197–203.

40 H 1967: 133.

41 B 1992: 144.42 F et al. 2009: 22, 24.43 P 2013: 133–135.

A 1690

G. E. A, Cartographe Graveur.“Il Golfo della Valona : con una parte delle

Dipendenze di Canina, Ultime Conquiste fatte

nell’Albania da ... Girolamo Cornaro / Giusto

Emilio Alberghetti.” [s.n.] (Venetia), 1690.B1992

V. B, “Amfora transporti të zbuluara

në vendbanimin e Treportit,” Iliria XXII,

129–47.B 1977-78

V. B -Gërmime në Triport.” Iliria VII

VIII (1977-1978): 285–92.

B 1993V. B “Gjurmë të fortifikimeve në

vendbanimin në Treport.” Iliria XXIII, no. 1–2

(1993): 143–59.B 1988

V. B “Kupat antike në vendbanimin e

Triportit.” Iliria XVIII, no. 2 (1988): 105–19.

B 1999

V. B “Le Site Antique de Treport,Port Des Villes Des Amantins.” In L’Illyrie

Méridionale et l’Épire Dans l’Antiquité III: Actes Du IIIe Colloque Internationalde Chantilly (16-19

Octobre 1996), edited by Pierre Cabanes, III:181–

85. Paris: De Boccard, 1999.

B 1986

V. B “Triport.” Iliria XVI, no. 2 (1986):258.

B 1985

V. B “Vendbanimi ilir në Triport të

Vlorës.” Iliria XV, no. 2 (1985): 313–20.B, G 2009

J-F, B, J. G “The 8200 Cal BP

Abrupt Environmental Change and the

Neolithic Transition: A MediterraneanPerspective.” Quaternary International 200, no.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1–2 (May 1, 2009): 31–49. doi:10.1016/j.

quaint.2008.05.013.

B 2013C. B, The Making of the Middle

Sea: A History of the Mediterranean from the Beginning

to the Emergence of the Classical World . Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2013.B 2006.

C. B, “The Origins and Early

Development of Mediterranean Maritime

Activity.” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 19,no. 2 (2006).

E et al. 2006.

N. E, P. B, P. E, P.

K, and M. N, 2006. “PrehistoricExploitation of Grevena Highland Zones:

Hunters and Herders along the Pindus

Chain of Western Macedonia (Greece).”World Archaeology 38, no. 3 (2006): 415–35.doi:10.1080/00438240600813327.

Exposition Universelle de 1867 à Paris:Catalogue général: Produits (bruts et ouvrés) des industries

exractives (Groupe V. - Classes 40 à 46.). Vol. 5. Paris:E. Dentu, 1867.

F 2002

E. F “Dynamiques Paléo- Environnementales En Albanie À l’Holocène.”

In L’Albanie Dans l’Europe Préhistorique, Actes Du

Colloque Lorient, 8-10 Juin 2000 , edited by Gilles

Touchais and J. Renard, 3–42. Bulletin de

Correspondance Hellenique/Supplement42. École française d’Athènes, 2002.

F 2007

E. F “Site et Région d’Apollonia”In Apollonia d’Illyrie 1. Atlas Archéologique et

Historique , edited by Vangjel Dimo, Philippe

Lenhardt, and François Quantin, 1:3–13.

Collection De L’école Française De Rome 391. Athènes, Rome: École française d’Athènes;

École française de Rome, 2007.

F et al . 2010.

E. F, C. V, L. D, G. G, J. L. M, M. D, O. M,

M. H, and E. H 2010. “Shoreline

Reconstruction since the Middle Holocene in

the Vicinity of the Ancient City of Apollonia(Albania, Seman and Vjosa Deltas).” Quaternary

Rudenc RUKA, Ilir GJIPALI, Michael L. GALATY and Novruz BAJRAMAJ

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

15/16

105

LITHICS AT ONE END OF THE CIRCUM-ADRIATIC: CASE STUDIES FROM THE SOUTHERNMOST ALBANIAN COASTAL LOWLAND

International 216, no. 1–2 (April 1, 2010): 118–28.

doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2009.06.021.

F, B, G 2009 K. F, D. B, and I. G 2009.

“A Preliminary Investigation of Two Prehistoric

Cave Sites in Southern Albania.” Annual of the British School at Athens 104 (2009): 9–26.

G 1914,

F. G, Les pays d’Albanie et leur

histoire . Paris: P. Rosier, 1914.

G 2012I. G, Epoka e Gurit dhe Shqipëria .

Tiranë, Botart, 2012.

G 2012

M. G ‘Balkan Flint’ – Fiction And/ or Trajectory to Neolithization: Evidence from

Bulgaria.” Bulgarian E-Journal of Archaeology,

no. 1 (2012): 15–49.

G 2008M. G “Towards an Understanding

of Early Neolithic Populations: A Flint

Perspective from Bulgaria.” Documenta

Praehistorica 35 (2008): 111–29.H 1967

N. G. L. H, Epirus: The

Geography, the Ancient Remains, the Historyand the Topography of Epirus and Adjacent

Areas . Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967.

K-P 2006.

G. K-P, “Bronze Age Lithic

Production in Northern Greece. The Evidencefrom Settlements.” In Lithic Technology in Metal

Using Societies: Proceedings of a UISPP Workshop,Lisbon, September 2006 , edited by B VE, 169–82. Jutland Archaeological Society

Publications 67. Højbjerg: Jutland Archaeological

Society, 2010.

K-P 2002 G. K-P, 2002. “Les Industries

Lithiques Taillées Du Bronze Moyen et Récent

En Grèce Du Nord et En Albanie: L’exemple de

Sovjan.” In L’Albanie Dans l’Europe Prehistorique.

Actes Du Colloque de Lorient 8-10 Juin 2000 ,

edited by G T and J. R,

73–84. Bulletin de Correspondance Hellenique/

Supplement 42. École française d’Athènes, 2002.

K-P 2006-2009

G. K-P,“Lithics in the

Neolithic of Northern Greece: TerritorialPerspectives from an off-Obsidian Area.” Documenta Praehistorica 36 (2009): 305–12.

K et al . 1991.

F. K, G. G, M. K, N. M,

P. Q, S. S, T. Z, V. K, andV. T. Gjeografia fizike e Shqipërisë: (Në dy

vëllime). Vol. II. Tiranë: Akademia e Shkencave

e Republikës së Shqipërisë, Qendra e StudimeveGjeografike, 1991.

L, G 2009

L, O, and G, M. 2009.“Albanian

Coastal Settlement from Prehistory to theIron Age.”edited by S,105–11.

BAR International Series 2037.

Oxford: Archaeopress, 2009.

P, C 2010 W.P, J. C “Pylos Regional

Archaeological Project, Part VIII: Lithics and

Landscapes: A Messenian Perspective.” Hesperia

79, no. 1 (2010): 1–51.P 1904

C. P, Das Sandschak Berat in Albanien:

Mit 180 Abbildungen Und Einer GeographischenKarte . Vol. III. Wien: A H, 1904.

P 2012

J. P,“New Experimental Observations

for the Characterization of Pressure Blade

Production Techniques.” In The Emergence of

Pressure Blade Making , edited by P M.

D, 465–500. Springer US, 2012.

http://link.springer.copter/10.1007/978-1-

4614-2003-3_18.P 2012

C. P, “Le statut des échanges

au Néolithique.” Rubricatum: revista

del Museu de Gavà 0, no. 5 (2012): 539–46.P 2004

C. P, Les industries lithiques taillées deFranchthi (Argolide, Grèce): Du Néolithique

ancien au Néolithique final . Vol. III. Excavations At Franchthi Cave, Greece, 13. Bloomington:

Indiana University Press, 2004.

P, G, D, 2013I. P, I, G, and V. D, “Epidamne-

-

8/9/2019 Lithics at One End of the Circum-Adriatic_ Case Studies From the Southernmost Albanian Coastal Lowland

16/16

106

Dyrrhachion: The Chora.” In Recent Archaeological

Discoveries in Albania , edited by Ilir G, Luan

P, and Belisa M, 130–35. Tirana:Botimet Albanologjike, 2013.

P, B 2008F. P, A, B, Bronzi i hershëm në

Shqipëri . Prishtinë: Qendra e Studimeve

Albanologjike, Instituti i Arkeologjisë, Tiranë,

2008.P, B 2014

F. P, A, B, Studime për ehistorinëe Shqipërisë . Tiranë: In press, 2014.

R et al . 2009

C. R, M. K, M. G, . T,

S. S, J. D, L. B, S, M,

“Early Prehistoric Landscape and Landuse in theFier Region of Albania.” Journal of Mediterranean

Archaeology 22, no. 2 (October 22, 2009): 151–82.

doi:10.1558/jmea.v22i2.151.

R et al . 2004 C. R, M. K, M. G,

M. T, SH. S, J. D, L. B,

S, M, “The Palaeolithic and Mesolithic of

Albania: Survey and Excavation at the Site ofKryegjata B (Fier District).” Journal of Mediterranean

Archaeology 17, no. 1 (2004): 3–29.S 2010

Y. S “Albania.” In Encyclopedia of

the World’s Coastal Landforms , edited by Eric C.

F. B, I:773–74. Dordrecht; Heidelberg;

London; New York: Springer Netherlands, 2010.

S-H 1999 C. S-H, The Ionian Islands

in the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, 3000-800 BC .

Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1999.

T 2004R. T “Neolithic Exploitation and Trade

of Obsidian in the Central Mediterranean:New

Results and Implications for Cultural Interaction.”

In Acts of the XIVth UISPP Congress, University

of Liège, Belgium, 2–8 September 2001, Section

9: The Neolithic in the Near East and Europe ,

25–35. BAR International Series 1303. Oxford:

Archaeopress, 2004.T 1996

R. T “Obsidian Procurement and

Distribution in the Central and Western

Mediterranean.” Journal of Mediterranean

Archaeology 9, no. 1 (January 6, 1996): 39–82.doi:10.1558/jmea.v.39.

U 1927L. M U, Albania antica: Ricerche

archeologiche . Vol. I. Roma-Milano: S.E.A.I.,1927.

U 2012

L.U, Holocene Landscape Changes of the

Lezha Region : A Contribution to the laeogeographies of

Coastal Albania and the Geoarchaeology of Ancient Lissos .

Marburg, Lahn: Marburger Geographische

Gesellschaft, 2012.W, Z 2003

J. W, K. Z, Landscape

Archaeology in Southern Epirus, Greece . Vol. I.

Hesperia. Supplement 32. Athens: AmericanSchool of Classical Studies at Athens, 2003.

X et al. 2002

A. X, A. K, L. D, Z. X, S.

N, V. N, D. Y, “Harta Gjeologjikee Shqipërisë.” Tirana: Shërbimi gjeologjik

shqiptar, 2002.

ΑρΑβΑντινού ΠΑργειού, ΠΑνΑγιώτού.

Χρονογραφία Της Ηπείρου: Των Τε Ομόρων

Ελληνικών Και Ιλλυρικών Χωρών Διατρέχουσα

Κατά Σειράν Τα Εν Αυταίς Συμβάντα ΑπόΤου Σωτηρίου Έτους Μέχρι Του 1854. Vol. II.

Αθήναις: Σ. Κ. Βλαστού, 1857.

Rudenc RUKA, Ilir GJIPALI, Michael L. GALATY and Novruz BAJRAMAJ