Korea Herald 20151111[1]

-

Upload

robert-cheek -

Category

Documents

-

view

96 -

download

1

Transcript of Korea Herald 20151111[1]

![Page 1: Korea Herald 20151111[1]](https://reader034.fdocuments.us/reader034/viewer/2022052418/58790bd31a28ab6f658b5d91/html5/thumbnails/1.jpg)

OPINION 15WEDNESDAY NOVEMBER 11, 2015

Koreans are inquisitive by nature. A foreigner who visited Korea in 1892 wrote, “Koreans are curious and like to meddle in other people’s business.” Even today, the Korean people seem to enjoy gossiping and prying into each other’s affairs. An upside of this innate curiosity is the community spirit that enables us to share many things together in a group-oriented society. The downside is that it is offensive and rude to others, especially to foreigners.

Thankfully, young Koreans do not seem to have inherited this unde-sirable legacy from the older gen-eration. In English, a meddlesome person is sometimes referred to as a nosy parker, or busybody. You ask people to stop poking their nose into your business when they are being overly inquisitive. Korean also has a colorful term for the more inquisi-tive members of our society: “People with a wide ojirap.” Ojirap is the Korean term for the lapels of one’s outer garments. Young Koreans use the slang “ojirapper”’ a portmanteau of “ojirap” and “rapper” (a rapper of

gossip, if you will) to describe these busybodies.

Ojirappers are a dime a dozen in Korean society. For example, on national holidays such as Chuseok or Lunar New Year’s Day, your relatives will gather at your house and bombard you with personal and embarrassing questions: “Why don’t you get married?” “Did you get a job yet?” “How much money do you make?” and so on. On reading advice columns like “Annie’s Mailbox,” I discovered that even America has its share of people with a proclivity for meddling. The ojirapper might be a universal malady, after all.

The right answer to these incon-siderate questions would be: “That’s none of your business,” yet you can-not dare say this to your seniors in Korean society. You just have to en-dure the embarrassing questions in silence. It is only natural that young people hate to be home on national holidays and want to go vacationing overseas instead.

The list of offensive questions is endless. Once I witnessed an uncle

embarrass his nephew by remark-ing, “How come you have such a dark complexion?” There is nothing you can do about your complexion, so no one has the right to pass such rude remarks. However, in Korea, it is not unusual to find people remarking on your skin tone fre-quently. Many Koreans do not seem to realize that it is a taboo to refer to another person’s color.

I happen to know a 5-year old girl who is cute enough, but not as pretty as her mother. Her mother once confided in me that she hated waiting at bus stops or taxi stands. I was saddened and embarrassed on learning the reason. Whenever they were waiting for a bus or taxi, people would almost always point at the daughter and ask, “Is she your daughter? She does not take after you.” The mother should have retort-ed, “What’s that to you?” Instead, she would just reply feebly, “Yes, she is.” Of course, the little girl knows the import of the words. In fact, she is so hurt by these inconsiderate remarks that whenever people look at her

and her mother, she calls out “Mom!” in an attempt to prevent them from asking the dreaded question.

When you tell people you have a baby girl, someone is likely to butt in and say, “You should have a boy, too.” On learning that you have only one child, they will tell you right away, “You should have another.” When someone gains weight, people will make fun of the person, call-ing them a fatso and telling them to stop stuffing themselves. If a slim person eats just a little at a restaurant, people will say rather sympathetically, “Come on. You are so skinny. You need more flesh on your bones.” Why do they not mind their own business? Why do they in-solently refer to other’s physical ap-pearances? These kibitzers need to undergo therapy so they can learn to stop poking their nose where it does not belong.

Another thing Koreans should know is that their greetings might sound unpleasant as well. When a Korean sees his friend, he will say to him or her, “You don’t look good.

Are you sick?” To the Korean people, such greetings mean, “I care about you.” As a global citizen, however, you cannot say such things to oth-ers, especially to foreigners. It is an extremely clumsy way of greeting a person. Instead, you should say, “You look great. What’s new?”

When a political issue is at stake, all Koreans stick their nose in it, and the whole nation is caught in an uproar. Why not let the politicians deal with it? But then, politicians, too, bring the issue to the street, inviting the public to butt in. That is why we say that everybody is a politician in Korea. When everybody, so a Korean saying goes, dips their oars in, the boat finds itself on top of the mountain.

Dear ojirappers, please mind your own business!

Kim Seong-kon is a professor emeritus of English at Seoul Nation-al University and the president of the Literature Translation Institute of Korea. — Ed.

The human race is entering an era of exponential technological growth unmatched by anything before in its history. The rate of technological evolution is now accelerating by the nanosecond. Most of the advances to date have been focused on the augmentation of the mind, or information analy-sis and processing. Advancements in these areas continue to move forward rapidly, and humanity now faces a scenario in which our technologies are breaking out of their boxes, migrating from the cyber world to the physical world. The CyberPhysical Era has begun and with it the robotic Internet of things (RIoT) economy.

The technological changes now coming online with robotics and artificial intelligence will disrupt far more businesses than did the first information revolution, which was dominated by personal com-puters, the Internet, and mobile devices. The emergence of this new age will bring great oppor-tunity to those who successfully navigate the swelling tides of the new blue ocean. But with great opportunity also comes great risk -both economic and existential.

The knowledge accumulated by the emergent Internet of Things — or the less commonly used, al-beit more accurate term Internet of everything — is then utilized by the technological ecosystem to evolve. The proliferation of learn-ing machines and the expansion of their intelligence now moves at speeds that for many observers, appears as surreal as science fic-tion.

In the book “Race Against the Machine” by MIT professors Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, a chessboard is used as an example to describe the evolution of tech-nology, specifically robotics and AI,

an idea which they borrowed from Ray Kurzweil. In the story, the inventor of chess shows his new game to his emperor. The emperor is so impressed by the game that he grants the inventor the right to select his own reward. The inven-tor asks for a quantity of rice to be calculated as follows: One grain of rice is put on the first square of the board, two on the second, four on the third, and so on, with each square doubling the number of grains as the previous. The em-peror agrees, thinking the reward too small. Much to his chagrin, he later sees that the doubling results in incredibly large numbers. The inventor ends up with 18 quin-tillion grains of rice, an amount which makes Mount Everest look like a molehill. The point of the story is that in an age of exponen-tial technological growth, things only get really interesting in the second half of the chessboard. We are now on the second half of the board. And things are getting very interesting, indeed.

Businesses of all types have been impacted by the moves already taken on the first half of the chess-board during the IT revolution that started in the 1980s. One example is what happened to photography with the advent of digital photog-raphy, which brought about the demise of some companies and emergence of others. This scenario is now happening in AI and robot-ics. Intelligent, easy-to-use ma-

chines dedicated to the service of humans are being developed and are becoming accessible to the ma-jority of consumers in terms of cost. These robot systems will spell the end of many jobs and businesses, but create new jobs and businesses for those positioned for the change. For employment, however, the net result will be negative, and mass unemployment will become an is-sue with which governments must contend.

The key difference between the intelligence revolution and the in-formation revolution, however, is the rise of cyberphysical systems. The technology now improves itself and learns from mistakes. The digital genie is now out of the cyber bottle, whether as a classical humanoid robot, an autonomous car, a nanobot implant or a robotic chef system.

In the Cyberphysical Era we will see AI and robotics (AI-enhanced robots, or AI bots) permeate the physical world. The AI bots in the RIoT system will be components of a “hive mind,” and use onboard processors as well as the cloud to learn from each other, not unlike a real-time Wikipedia for AI bots, thus magnifying their efficiency and growing its knowledge base. This year, IBM and Softbank gave birth to the first generation of AIbots by fusing Watson AI and Pepper, the service robot. While at the University of Cambridge, scientists have created a “mother robot” that builds smaller robots, and selects the fittest for survival, and rearranges the rest.

Two keys are required for busi-nesses to prosper in the RIoT economy. The first is technological capability, which Korean compa-nies possess in abundance. The second is diverse staff with inter-national networks and experience

in building cross-border partner-ships in emerging technology busi-nesses such as service robotics. The second key is used in places like Silicon Valley and Berlin to create future businesses. In Korea, however, companies must work harder to build this ecosystem to attract such talent. This involves much more than simply rezoning or calling an area a “Silicon Val-ley of …” Indeed, it is neither the name nor the geographic location that makes a Silicon Valley, but the interplay of diverse ideas that creates future businesses.

The path to failure, unfortunate-ly, is far easier to travel. Investing in companies with little to offer in terms of new solutions to old problems is one. One example in-volves large investments made into a company building a social robot that was popular on a crowdfund-ing website. Although the robot has enjoyed a substantial funding rela-tive to its potential, it does little more than what tablets and phones already do. But this is par for the course in most service robotics.

Businesses can avoid such pit-falls by working with profession-als that know the business and understand how these emergent technologies can be used for lofty yet realistic outcomes. This is the way to most efficiently allocate re-sources in RIoT-related companies that have the greatest potential to disrupt existing business models or create entirely new business models.

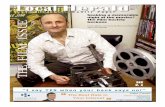

Robert (Robb the Robot Guy) Cheek is a research analyst and editorial head at HMC Investment Securities, the investment banking arm of the Hyundai Motor Group. He can be reached at [email protected]. — Ed.

Ojirappers, mind your own business

KIM SEONG-KON

On reading advice columns like “Annie’s Mailbox,” I discovered that even America has its share of people with a proclivity for meddling. The ojirapper might be a universal malady, after all.

The views expressed in the contributed and syndicated articles on Pages 14 and 15 do not necessarily reflect those of The Korea Herald or its editorial staff. — Ed.

Articles and letters intended for publication on the opinion page should be sent by email to [email protected] and contain the writer’s full name, phone number, occupation and address. Articles are subject to editing and are expected to observe our word count limit. Submissions to “A Reader’s View” and “Letters to the Editor” must not exceed 500 words. — Ed.

To our contributors

Thinking outside the box: AI bots and robotic IoT

100 years later, Einstein’s theory stands strongBy Paul HalpernThe Philadelphia Inquirer

It is not often that a centenarian is just as spry and vital as the day she was born, but that’s the case with the general theory of relativity.

This month we are celebrating exactly 100 years since the meeting in which Albert Einstein announced the completion of his masterful theory of how gravity works. His grand theory relating the geometry of space and time to the matter and energy within it represents an ex-traordinary triumph of the human imagination.

Before Einstein, there was Isaac Newton, who had offered a simpler, but much less satisfying theory of gravity.

Contrary to popular myth, Newton did not discover gravity. From earli-est times, no one could mistake the fact that things fall down if released from a certain height. Rather, New-ton demonstrated that gravity is a universal force with certain predict-able properties. This force could act over immense distances, linking, for instance, the Sun and the Earth as if an invisible string tied them together.

Although Newton’s theory was very successful, it contained a logi-cal flaw: the idea that gravity could be transmitted instantly. If the Sun suddenly disappeared, his theory predicted that Earth would im-mediately sense its absence, as if a thread were cut, and start traveling in a straight line through space.

Yet Einstein had showed in his special theory of relativity (the predecessor to the general theory), space has a speed limit. No signal in empty space can travel faster than the speed of light. The Sun’s light takes eight minutes to reach Earth. Therefore, Earth could not possibly respond to the Sun’s disappearance in less than that time period — cer-tainly not instantly.

Einstein’s general relativity beau-tifully recasts gravitation as a local, rather than long-distance, phenome-non. The equations he announced in November 1915 show precisely how it is the fabric of space and time — known in tandem as spacetime — that conveys gravity.

Much like a turbulent wild river with eddies and currents that change the course of boats, spacetime’s bumps and ripples compel planets and stars to alter their paths. In the case of Earth, a gravitational well compels Earth to travel in an ellipti-cal orbit rather than in a straight line. The cause of that indentation in spacetime is the mass of the Sun. Or, as often expressed by the late gravi-tational physicist John Wheeler (who came to know Einstein well), space tells matter how to move and mat-

ter, in turn, tells space how to curve.How Einstein’s theory was tested

offers an important lesson in the value of international cooperation.

Einstein predicted that the paths of light rays would be diverted by the presence of massive objects. He estimated the angle by which star-light would bend in the vicinity of the Sun and pointed out that this distortion could be measured during a solar eclipse.

To accomplish this task, Einstein found a friend in British astrono-mer Arthur Eddington, who organ-ized expeditions to West Africa and South America, in spring 1919, where a solar eclipse could readily be seen. The remarkable thing about the collaboration between Einstein and Eddington was that it took place shortly after World War I, when their two native countries (Germany and the United Kingdom) had been enemies. Both thinkers were paci-fists and hated nationalism, which made such cooperation easier.

During the summer of 1919, the eclipse results were analyzed and compared to predictions based on Newtonian physics. Although the data was sparse, the results fell much closer to Einstein’s forecast than one based on Newton’s theory of gravitation. Thus it came to pass that in November 1919 the British Royal Academy announced that Ein-stein’s theory was triumphant.

The confirmation of general rela-tivity generated startling headlines around the world. The firmament of the heavens was no longer stable and secure, rather it was an ever-changing canvas. Nothing in science was stable. In fact, 10 years later, results by American astronomer Edwin Hubble showed that the universe itself was expanding — an-other prediction of general relativity.

For various reasons, including its lack of correspondence with quan-tum mechanics, the other major the-ory developed in the early 20th cen-tury, physicists have tried to modify general relativity. Nevertheless, despite a century of effort, Einstein’s masterpiece still stands strong.

Let’s offer a toast to the beauty of the venerable equations describing the cosmos, and wish them well for decades to come — unless, that is, a quantum version comes along.

Paul Halpern is a University of the Sciences physics professor and the author of “Einstein’s Dice and Schrodinger’s Cat: How Two Great Minds Battled Quantum Random-ness to Create a Unified Theory of Physics.” He wrote this for The Philadelphia Inquirer. — Ed.

(Tribune Content Agency)

ROBERT CHEEK