KHARTOUM PRO-POOR.pdf

-

Upload

aymenhashim -

Category

Documents

-

view

36 -

download

2

Transcript of KHARTOUM PRO-POOR.pdf

-

United Nations Human Settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

KHARTOUM PRO-POOR:

FROM POlicy Design TO PilOT iMPleMenTATiOn PROjecTs

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

2

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), 2010

International Guidelines on Decentralization and Access to Basic Services for all

All rights reserved

UNITED NATIONS HUMAN SETTLEMENT PROGRAMME

P.O.BOX 30030, GPO, Nairobi, 00100, Kenya.

Tel.: +254 (20) 762 3120

Fax: +254 (20) 762 4266/4267/4264/3477/4060

E-mail: [email protected]

www.unhabitat.org

DISCLAIMER

The designation employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of this publication do not necessarily relect the view of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), the Governing council of UN- HABITAT or its Member States. Excerpts may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated.

ISBN Number:

Primary authors: Fernando Murillo, Mathias Spaliviero and Abdel Rahman Mustafa.

Photographs: Fernando Murillo and Abdel Rahman Mustafa

Sketches: Fernando Murillo

Editor: Julia Helena Tabbita

Layout: Florence Kuria

Sponsors: European Commission (EC) - Cooperazione Italiana

Printing:

For further information regarding this publication please contact:

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 3

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

TAble Of cOnTenTs

1. sUMMARy 7

2. inTRODUcTiOn 8

2.1 BAcKgROUnD 8

2.2 HisTORicAl ReFeRences 14

2.3 PROjecT OBjecTiVes 17

2.4 MeTHODOlOgy 17

2.4.1 setting up the project 17

2.4.2 stakeholders 18

2.4.3 Recruitment of staff 18

3. AcHieVeMenTs 19

3.1 TRAining AnD cAPAciTy BUilDing 19

3.1.1 Training in stabilized soil block (ssB) production and construction 19

3.1.2 Training in alternative low cost sanitary system for urban poor 21

3.1.3 Training in lood-resistant housing and land tenure legal access 22

3.1.4 Training in model housing and multistory building design and construction 23

3.1.5 Training in participatory design and planning 25

3.1.6 Training in strategic planning 25

3.1.7 Training in data entry and geographic information system (gis) 29

3.1.8 Action plan for capacity building (cB) 30

3.2 PilOT PROjecTs 31

3.2.1 Brief description 34

3.2.2 Major components of the pilot projects 38

3.2.3 Mansura 40

3.2.4 Mayo-Mandela 41

3.2.5 Rasheed 41

3.3 FORMUlATiOn OF sTRATegic PlAns FOR VillAges AnD TOWns 44

3.3.1 selection of villages and towns 44

3.3.2 lodging villages 45

3.3.3 Rural-urban linkages 46

4. DiFFicUlTies FAceD AnD cOnTingency PlAns 49

5. lessOns leARnT 50

6. THe WAy FORWARD: KHARTOUM WiTHOUT slUMs 57

7. FinAl ReMARKs 62

Annex: RUsPs QUesTiOnnAiRe 67

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

4

lisT OF TABles

Table i. comparison between strategic and traditional planning

Table ii. Brief description of the three pilot projects

Table iii. Major components of pilot projects

lisT OF FigURes

Figure 1. Map of Khartoum state showing villages and the metropolis

Figure 2. From informal settlement to low density neighbourhoods

Figure 3. Village landscape

Figure 4. Poverty map

Figure 5. land prices map

Figure 6. RUsPs session

Figure 7. ssB production in Mansura

Figure 8. ssB making machines in jebel Awlia

Figure 9. Popular neighbourhood in Omdurman

Figure 10. Un-Habitat approach in Khartoum

Figure 11. entrance of Khartoum University

Figure 12. View of Mahdi tomb

Figure 13. Khartoum historical maps

Figure 14. Map and view of Dar Al salam projects

Figure 15. Khartoum aerial view

Figure 16. Training in ssB

Figure 17. experimental construction in stabilized soil block (ssB) by the Training and Research institute (TRi)

Figure 18. ssB hand pressing machines

Figure 19. Testing and dry mixing soil

Figure 20. Training in innovative construction techniques.

Figure 21. cluster for ssB production and construction in Mansura

Figure 22. Use of forbidden digging machines that contaminate the groundwater.

Figure 23. Training in alternative sanitation technology

Figure 24. Map of areas liable to looding in Khartoum and lood scene in Mayo

Figure 25. Flooding resistance strategies incorporated in model housing design

Figure 26. A family living in temporary conditions before self-building a model house

Figure 27. image of the model house built by the family presented in igure 26.

Figure 28. ground loor, irst and second loor plan and perspective of a proposed design for multistory low income housing.

Figure 29. Major components of strategic planning proposed for Khartoum structural Plan (KsP)

Figure 30. Prioritization exercise in a community consultation meeting

Figure 31. Participation of women in a consultative meeting

Figure 32. strategic planning methodology for small cities and villages

Figure 33. example of digitalized map of jewel Awlia

Figure 34. land use map and location of social services in jebel Awlia.

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 5

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

Figure 35. gis map showing looding-prone areas

Figure 36. Discussion and agreement between communities and government representatives

Figure 37. Mansura

Figure 38. Mayo-Mandela

Figure 39. Rasheed in jebel Awlia

Figure 40. location of pilot projects

Figure 41. Mansura urban pattern and layout plan

Figure 42. Urban pattern of Mayo-Mandela camp

Figure 43. Rasheed in jebel Awlia.

Figure 44. self-help construction in jebel Awlia

Figure 45. Womens centre in Mansura, before the implementation of the project

Figure 46. Rebuilt womens centre in Mansura

Figure 47. Production of ssB in Mayo-Mandela

Figure 48. Model houses in el Rasheed.

Figure 49. interior of a model house

Figure 50. Typical village scene

Figure 51. scene in el Fateh

Figure 52. Map showing lodging villages

Figure 53. Fertile rural areas attractive for tourism

Figure 54. conceptual diagram of the applied methodology to assess rural-urban linkages

Figure 55. low income group participating in the initial steps of RUsPs

Figure 56. sketch representing technical discussion

Figure 57. sketch representing community participation

Figure 58. strategic location of Mansura, close to the urban fabric: Between land speculation and pro-poor policies

Figure 59. Public utilities carried out through community work

Figure 60. contrast between ssB construction and mud buildings

Figure 61. Agreeing on priority development projects for the city and villages

Figure 62. Discussion on urban trends at a local observatory

Figure 63. Tourism infrastructure near villages surrounding Khartoum.

Figure 64. Proposed institutional structure for Khartoum without slums programme

Figure 65. components of Khartoum without slums programme

Figure 66. Blueprint for implementing Khartoum without slums programme

Figure 67. Multistory buildings contribute to increasing density and diversity in popular neighbourhoods.

Figure 68. Mosque in Mayo-Mandela

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

6

CBO community based organization

GIS geographic information system

IDP internally displaced person

ILO International Labour Organization

KSP Khartoum Strategic Plan

KWS Khartoum without Slums

LED local economic development

MPPPU Ministry of Physical Planning and Public Utilities

MP&UD Ministry of Planning and Urban Development

NGO non-governmental organization

OJT on the job training

PDB pilot demonstration building

PDP pilot demonstration project

RUSPS Rapid Urban Study Proile for Sustainability

SDF Social Development Foundation

SSB stabilized soil block

TRI Training Research Institute

TOT training of trainers

UN United Nations

UNCHS United Nations Centre for Human Settlements

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UNEP United Nations Environmental Programme

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientiic and Cultural Organization

UN-HABITAT United Nations Human Settlements Programme

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

UNRISD United Nations Research Institute for Social Development

UNIDO United Nations Industrial Development Organization

WHO World Health Organization

AcROnYMs

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 7

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

This publication summarizes the projects carried out by UN-Habitat in Khartoum between 2008 and 2010. It is a follow up to the already published Urban Sector Studies and Capacity Building for Khartoum State. The work involves more than forty professionals from different disciplines working collaboratively with their governmental counterparts to assess the major problems faced by the poor. The slum upgrading exercise links pro-poor policies with pilot demonstration projects, including housing and public utilities construction. These activities were carried out by training individuals and developing capacity for governmental and non- governmental organizations (NGOs). It is estimated that 2450 individuals were directly beneitted by training, and 1800 people participated in different consultations carried out using the Rapid Urban Studies Proile (RUSPS) approach. In addition, 900 households got direct support to self-build their houses, beneiting poor populations and their host communities.

This publication shares lessons learnt with colleagues from different ields and organizations involved in rapid urbanization in Sudan. These lessons cover a broad range of topics and stages, from early ideas for IDP (internally displaced person) reintegration to community mobilization and neighbourhood regularization. The publication seeks to contribute to developing a way forward based on community consensus rather than imposition.

Over the last decade an extremely complex combination of real estate speculation, tribal misunderstandings, and political tension has pushed the government to systematic eviction of squatter settlements, causing serious incidents of violence and civil unrest. In recent times, the Ministry of Planning and Urban Development (MPUD) -formerly the Ministry of Physical Planning and Public Utilities (MPPPU)- as well as localities have tested many more participatory, strategic and pro-poor planning approaches, discussing with target populations alternatives for informal settlement upgrading, in the framework of an integrated plan including voluntary relocation. The development of comprehensive alternatives, including land, housing, basic urban services, livelihoods and local economic development has shaped new approaches which respond to speciic identiied categories of the poor, according

to the area where they reside. Such alternatives, discussed and prioritized by communities through RUSPS, are crucial to implementing the Guiding Principles for Relocation, an oficial agreement signed by the Wali (Governor of Khartoum) and Head of UN Agencies, which protects the rights of displaced populations. Dissemination of the Guiding Principles and alternatives for pro-poor urbanization and resettlement enhance popular and governmental understanding of the rights and possibilities of the poor to access land, housing and basic services.

In the creation of alternatives it is important to match approaches to realities. Passing from policy making to implementation of pilot projects means more lessons are learnt based on concrete results. The implementation of three pilot projects provides a valid sample of scenarios for intervention: Mansura, at the edge of the consolidated city; Mayo-Mandela camp, in the irst belt; and Rasheed, in Jebel Awlia locality, on the extreme outskirts. The introduction of an environmentally friendly technology such as stabilized soil block (SSB), affordable for low income households, serves to replace traditional ired bricks. With some training, SSB hand press machines have been shown to be effective in empowering low income communities. The pilot projects demonstrate promising results in terms of community ownership and governmental commitment. Strategic planning for villages and towns enhances rural-urban linkages, the key to tackle poverty in metropolitan Khartoum. Lessons learnt are summarized at the end, offering a way forward to further implementation of pro-poor policies, combining a regulatory framework, public works and self-help incentives. Khartoum without slums is a systematic slum upgrading programme proposed as the way forward.

1. sUMMARY

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

8

2. InTRODUcTIOn

2.1 BAcKgROUnD

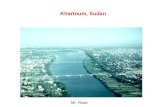

Khartoum state has the smallest area (22122 km2) but the highest population density in Sudan (13,1 inhabitants per km2), with more than 26% of the whole country population. Its three cities, Khartoum, Khartoum North and Omdurman, constitute a metropolis of more than 7,000,000 inhabitants with serious social and environmental problems.

Its hinterland, shaped by the river Nile, presents a wide range of villages and towns with very different livelihood opportunities (Figure 1). Massive migration of poor populations to Khartoum in recent decades, mostly because of war, drought and poverty, explains the mismatch between offer and demand of popular habitat and basic urban services.

figure 1. Map of Khartoum state showing villages and the metropolitan city

Peace followed by the spontaneous relocation of IDPs to their home areas has created the enormous planning challenge of making Khartoum a real multicultural capital. However, the low level of returnees, the arrival of new IDPs and an increase in poverty at the State level have complicated such plans, triggering further eviction and demolition campaigns.

Khartoum, emerging as a modern metropolis beneiting from the revenues of oil, also faces the challenge of building peace and providing decent habitat for all (Figure 2). Site and services has been the policy applied historically in Khartoum to provide accommodation for all inhabitants, subdividing and leasing land according to three basic categories or classes. Studies demonstrate that this policy in the context of Khartoum is already out of date, as more than half of the beneiciaries were unable to build their basic facilities, leaving enormous percentages of unoccupied land. This has led to the phenomenon of sprawl, settlements extending horizontally with low densities and without infrastructure, segregating the poor to the outskirts.

figure 2. from informal settlement to low density

neighbourhoods

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 9

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

Most rural villagers, living in survival economies, are potential migrants to metropolitan Khartoum, seeking better living conditions, social services (health, education, etc.) and income generation opportunities. The lack of affordable inancial mechanisms is one of the major reasons for the low ratio of construction, even among those poor owning land. The impact of building regulations and the high cost of building materials, partially as a result of the taxation system, also affect the possibilities of the poor to access decent housing.

Those villages close to the city have been formally incorporated into the urban areas. A speciic policy, which involved regularizing plots, easing conditions and freezing some stipulations, has encouraged villagers to remain and carry out agro-industrial activities. The philosophy is to empower villages as income generation areas and bring down the price of basic food and supplies in the metropolis. These are crucial components of the village development strategy and the Structure Plan of Khartoum State.

figure 3. Village landscape

In 2008, UN-Habitat carried out a comprehensive study which focused on the factors triggering the growth of the urban poor. Taking into account particularly their habitat conditions, different combinations of factors were identiied.

Different recommendations arose from this diagnosis, proposing speciic and systematic actions in the framework of pro-poor policies based on a poverty map (Figure 4). The Ministry of Physical Planning and Public Utilities (MPPPU), now designated as Ministry of Planning and Urban Development (MPUD), has adopted these pro-poor policies in its 2009-2010 Work Plan, incorporated in the framework of the Khartoum Strategic Plan

figure 4. Poverty map

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

10

The poverty map relects ive categories of urban poor located in different areas of Khartoum:

1. IDPs living in camps, typically located in remote areas and corresponding to 10% of the urban poor.

2. Squatters, located in the surrounding areas, and constantly relocated because of insecure land tenure. These make up 20% of the urban poor.

3. Villages, mainly located on the outskirts and out of the city, along the Nile. They are in process of being integrated to the urban structure, and house 20% of the urban poor.

4. Sites and services settlements, in different locations outside the consolidated city, corresponding to 25% of the urban poor.

5. Renting in the inner city under informal habitat conditions (overcrowding, etc.), corresponding to 25% of the urban poor.

The diagnosis also included a study on capacity building, identifying speciic institutional and human resource bottlenecks to the delivery of services. As capacity building is a key component in pro-poor policies, it has been specially addressed in their implementation.

At the same time, an assessment of land prices (Figure 5) was carried out in order to identify segregation trends, according to land prices. The assessment demonstrated that the urban

fabric close to the city centres of Khartoum, Omdurman and Khartoum North, has the highest land prices, over 100,000 Sudanese Dinar (1000 SDG), and constitutes less than 5% of the land area, whereas the lowest prices, 20.000 Sudanese Dinar (200 SDG) (more than 5 times less), constitute more than 50%. The assessment also revealed the correspondence between land prices and the location of the different categories of poor. Evidence showed that low land prices out of the urban fabric increase segregation to the periphery of the city.

figure 5. land prices map

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 11

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

With these critical insights, four community consultations and participatory planning exercises (Figure 6) were conducted in the form of a Rapid Urban Sector Proile for Sustainability (RUSPS). This is a methodology for project development based on consensus building used by UN-Habitat worldwide. It is promoted as a crucial tool for participatory planning, introduced in the MPUD and localities structures as part of the capacity building action plan. RUSPS was applied selectively to poor neighbourhoods representing the different categories of the urban poor. Bringing together community leaders and public oficials to agree on priorities for interventions has been a crucial achievement coming out of the pilot projects.

Once active participation and engagement of local residents were achieved, speciic actions to upgrade areas were identiied, taking into account agreed priorities. The introduction of appropriate technologies, such as stabilized soil block (SSB), and the supply of SSB hand pressing machines, cement and training, have been shown to be an effective way to mobilize communities in order to implement action plans (Figure 7).

figure 6. RUsPs session

figure 7. ssb production in Mansura

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

12

Progress in pro-poor policies and capacity building contributes to creating effective legal frameworks orientated to human rights. Pilot projects, targeted at villages and reception zones in the surroundings of Khartoum, included the construction of social services, shelter and livelihood facilities.

The application of innovative technologies that were affordable, appropriate and easy to learn by the poor, empowered community self- organization and encouraged sustainable development (Figure 8).

figure 8. ssb making machines in Jebel Awlia

The projects Enhancing the Capacity of Khartoum State to formulate and implement pro-poor urban policy funded by the EC, laid a foundation for launching the project Khartoum State Urban Planning and Development Programme, which is funded by the Italian Cooperation and focuses on implementing action plans and policies addressing urbanization challenges in towns and villages.

Both projects encourage participatory approaches to addressing problems related to rapid urbanization through the participation and mobilization of communities as an eficient and effective way to implement pro-poor policies. These include more lexible building regulations, promoting a shift from individual one single story to multistory housing, increasing densities. Higher densities make basic urban services for the poor more affordable (Figure 9).

Higher densities make basic urban services for the poor more afordable

figure 9. Popular neighbourhood in Omdurman

The approach applied by UN-Habitat in Khartoum (Figure 10), interlinks several components that have been tested through the application of a pro-poor policy framework, applied speciically through the pilot projects.

Comprehensive multidisciplinary studies allowed a diagnosis, identifying categories of poor and the speciic factors affecting them. Then, an action plan was designed in order to respond to speciic identiied problems and exploit opportunities.

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 13

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

figure 10. Un-Habitat approach in Khartoum

At this point, two results arose from the study. Pro-poor policies were designed according to the diagnosis, and capacity building plans were made taking into account speciic institutional limitations and bottlenecks to the implementation of pro-poor policies. At the same time, RUSPS carried out in selected cases, provided key information to design pilot projects, combining direct interventions and an amendment to regulatory legal frameworks.

These two approaches, applied both in a top-down and bottom-up way, provided consistency and reliability to the participatory planning process. RUSPS itself is already a key step in pilot project design, involving all stakeholders. The approach supposes that pilot projects must be linked to a global strategy to tackle informal settlements through an upgrading programme. This requires a consistent vision to combine national, state and local efforts systematically, to revert informality trends and prevent the formation of new slums, facilitating access to

land and services through different modalities.

Pilot projects are useful to check advantages and disadvantages of different alternatives. They promote rural-urban linkages, providing strategic infrastructures, such as reception centres for migrants, and regional transport to enhance the integration of villages and towns into regional dynamics. Cases of pilot projects on the urban edge, such as Rasheed in Jewel Awlia, illustrate a viable way forward to harmonize urban-rural exchange of production and services.

A strategy for slum upgrading adopting a human rights approach has been proposed to deal with squatters and informal settlements. A broad range of participating institutions anchor the process, empowering local capacities to develop Khartoum as a multicultural capital, rich in architectural and planning heritage (Figure 11).

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

14

figure 11. entrance of Khartoum University

2.2 HisTORicAl ReFeRence

Ibrahim Pasha, the ruler of Egypt, founded Khartoum in 1821. Its strategic location made the city grow up quickly as a regional trade centre. But an army loyal to the Mahdi (Figure 12) Muhammad Ahmad laid siege to Khartoum on 13th March 1884, ending in a massacre of the Anglo-Egyptian garrison. The heavily damaged city fell to the Mahdists on 26th January 1885. However, later on the Mahdi army was defeated and in 1899, Khartoum became the capital of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. The layout of Khartoum, based on a grid system and diagonal streets, was designed to converge in a way that would allow machine-guns to sweep the town.

figure 12. View of Mahdi tomb

Historically, Khartoums planning inheritance originated in British colonial times. It establishes a system of land use and subdivision based on three nationalities: English, Egyptian, and native. Housing for native Sudanese was strictly controlled in order to keep the minimum number of people needed for supporting economic activities, but explicitly avoiding the mass settlement of the native population. The settlement of public oficials was supported by providing land at nominal prices, on which houses could be built with permanent construction materials. This social hierarchy was supported by land allocation, creating three plot categories: irst, second and third class, with different plot sizes and lease periods, according to income level.

There was historically a fourth class category, reserved for economic migrants, known as native lodging areas. The colonial period Village Land Regulation (1948) allowed such fourth class plots to be upgraded to third or second class if the occupant was able to build a permanent structure. This law was later abolished, accepting only the minimum plot size of third class for legal registration (200 square metres), which prevented the poorest from accessing secure land tenure. Notoriously, this zoning mechanism has remained in force until today, controlling Khartoums development and constituting the basic structure for the whole socio-territorial planning system.

figure 13. Khartoum historical maps

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 15

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

The planning approach involves the control of land allocation, minimizing the occupation of agricultural land for urban uses. In addition, the plan seeks to keep most available land under governmental control. The key to such control has lain in only allowing land ownership for those minorities associated with the government bureaucracy, and the practice of permanent demolition and relocation of communities to regulate the growth of the three towns.

In 1908, Mc Lean implemented a master plan that deined an urban boundary to avoid urban sprawl, and remained unchanged for 40 years. The master plan exercise targeted a population of 100.000 inhabitants in a total area of 11, 5 km2, with a gross density of 87 persons per hectare. The urban plan consisted of a strong deinition of the urban boundary through a surrounding wall, in the current Khartoum city. This master plan marked the golden era of Sudans urbanism because it included the design of an urban pattern that matched the most modern landscape and architectural concepts of that time, shaping Khartoum into a civilized colonial centre. The pride of the citizens at that time would endure throughout the 20th century, serving as a reference model to compare with the future decline of the city.

In line with previous measures, the Land Regulation Act of 1925 sought the strict and effective use of land, preventing speculation.

On Sudans achieving independence in 1956, Khartoum became the capital of the new country. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Khartoum was the destination for hundreds of thousands of refugees leeing from conlicts in neighboring nations such as Chad, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Uganda. The Eritrean and Ethiopian refugees assimilated into society whereas some of the other refugees settled in large slums on the outskirts of the city. From the mid-1980s onwards, large numbers of South Sudanese and Darfuri, internally displaced by the violence of the Second Sudanese Civil War and Darfur conlict, have settled around Khartoum. In the framework of traditional replanning exercises, informal settlements were targeted by a violent demolition campaign. Integrated into the successive master plans, four mechanisms were historically applied

to manage the problem of squatter housing in Greater Khartoum:

eradication: 1. It was practiced from 1927 until the late 1970s. This only led to changing the location of squatter areas and increasing urban land speculation.

land price control:2. It consisted of deining prices for residential land, charging high fees for land exchange. That resulted in an unprecedented increase in land prices and speculation.

Rent control: 3. Several acts were issued in the 1970s to control rents. This discouraged developers and owners from producing housing for the market; consequently, demand and speculation increased.

The Green belt: 4. A huge green belt was developed south of Khartoum in the 1970s to stop the mushrooming of squatter settlements. However, it failed because the squatters built new settlements beyond it. Other bounding concepts, designed to circumscribe the urban area with huge agricultural projects, suffered a similar fate.

In 1991, the Village Regulation Administration, and in 2000, the Urban Development Administration, both introduced amendments to the policy towards squatters. The new package of policies included different solutions for different types of squatters.

The main policy concepts for dealing with squatter settlements in the 1990s can be summarized in three major groups:

I. Oficial cancellation of the 4th class areas: This measure upgraded 4th class areas to 3rd class. One of the more prominent examples was the relocation of Ishash Falata neighbourhood to Al Ingaz. With the same number of residential plots and population, the plot size was reduced (from 350-300 square metres to 100 square metres) and the total required area was decreased by 133 hectares (two-thirds). This increased the density from 167 persons per hectare to 455 persons per hectare (nearly 2.5 times).

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

16

II. Dar Al salaam concept: This is a simple sites and services approach, accompanied by the freezing of some building by-laws, especially those stipulating building standards. Basic services are provided such as potable water, levelling of the site, and protection from loods (Figure 14). The concept began by grouping several settlements around a serviced core, composed of 10,000 housing units. The idea was replicated in areas close to the urban fabrics of Khartoums three cities.

Omdurman hosts a population double the size of the Dar Al Salam project.

Here the concept has shown positive results and a shorter consolidation time (around 10 years) than was achieved in the former settlements. Afterwards, the experience was replicated around the localities until a total number of 339,667 families of the original squatters and IDPs were settled.

figure 14. Map and view of Dar Al salam projects

figure 15. Khartoum aerial view

III. Incorporation of villages within the urban fabric: Villages have been the main incubators for squatters over the last three decades. An active process of brokerage and speculation instigated the phenomenon.

Incorporation irst took place for villages within the urban fabric and then for remote villages. As tens of villages and their illegal extensions have encroached on the city boundary, their incorporation within the urban fabric has been a sine qua non. The incorporation of old villages in consolidated Khartoum has transformed it into a vibrant metropolis with higher densities (igure 15), promoting new possibilities for accessing better living conditions for the poor living on the outskirts.

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 17

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

2.3 PROjecT OBjecTiVes

The projects enhancing capacity of Khartoum state to formulate and implement pro-poor urban policy (2008-2010) and Khartoum state Urban Planning and Development Programme (2009-2011) support the broad objective of contributing to urban poverty reduction in Khartoum State as well as identifying speciic targets for development:

To guide the state and local authorities to achieve a shared vision of the settlements future by introducing Strategic plans for three towns and nine villages within Khartoum state.

To assist Khartoum State in developing priority actions identiied in the strategic plan into fully prepared technical assistance projects and "bankable" investment packages.

To strengthen local capacity for coordinated planning and management of urban development and growth.

To cumulatively attain the overarching development objective and achieve speciic objectives, the project has broadly undertaken the following tasks:

To prepare Strategic plans for three towns and nine villages and formulate a basis for a strategic approach which can be replicated in other locations

To formulate city and village priority development projects, promoting local economic development (LED) in the form of an investment action plan that targets strategic works and encourages potential development activities

To prepare training manuals for strategic and action planning

To demonstrate visible actions (self-help housing construction using SSB technology), exploring alternatives for rooing, sanitation and multistory buildings by means of pilot demonstration buildings (PDBs). Such PDBs are crucial to introduce more sustainable urban patterns, encouraging higher densities and a better distribution of facilities. These are keys to sustainable urbanization, based on assessment incorporated in the Khartoum Structural Plan (KSP)

To prepare local indicators of land use and basic urban services for the State

2.4 MeTHODOlOgy

2.4.1 SETTING UP THE PROJECT

The project carried out a broad consultation with different stakeholders involved in previous RUSPS exercises to agree on the way forward for implementation. The government, represented by different ministries, made a commitment to delivering priority services, monitoring and supervision, as guided by communities. RUSPS was adapted to MPUD legal framework, conducting training and capacity building activities within the daily routine of the MPUD and the communities.

UN-Habitat has coordinated all activities, creating a technical team to carry out strategic planning for villages and towns, providing training and identifying institutional gaps to focus on capacity building. Several implementing partners, like academic institutions, were identiied to carry out construction, signing agreements of cooperation (Figure 16).

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

18

2.4.2 STAKEHOLDERS

The Ministry of Planning and Urban Development together with the Ministry of Basic Infrastructure of Khartoum State are the main stakeholders in addition to Jebel Awlia and Omdurman localities, Jebel Awlia administrative units, the respective popular committees at community level, popular committees in Mayo-Mandela camp and Mansura area, and special community representatives, playing key roles in consultation and agreement on priorities.

On the construction/technological side, the Training and Research Institute (TRI) is the implementing partner of the model housing construction, including SSB (Figure 17), rooing and sanitation; and the Social Development Foundation (SDF) is responsible for partnering efforts and investing a revolving micro-credit fund.

2.4.3. RECRUITMENT OF STAFF

The following staff have been recruited:

National Urban PlannerGIS National Expert

figure 16. Training in ssb

Local Economic Development ExpertRUSPS National Experts (3)National Environment ExpertInternational Urban Planner ICT Database National Experts

National teams have been created and guided by means of different types of training, using the method of training of trainers (TOT) and on the job training (OJT), to develop their capabilities to apply new skills and develop their capacities. These teams were in charge of implementing strategic planning in 3 cities and 9 villages. In close coordination with the MPUD, villages and cities were selected and approached their respective local authorities. The recruitment of national staff, supported by villages and cities, and focus group discussion served to develop participatory strategic plans.

Newsletters and pamphlets were provided to implementing partners in order to create a consistent community awareness framework supporting the implementation of strategic planning exercises.

figure 17. experimental construction in stabilized soil block (ssb) by the Training and Research Institute (TRI)

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 19

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

3. AcHIeVeMenTs

The project achievements can be summarized in three major areas: Training, capacity building and pilot demonstration projects, each of which contributes to the development of participatory approaches guiding rapid urbanization in villages and towns.

he project achievements can be summarized in three major areas: Training, capacity building and pilot demonstration projects.

The objective of training and capacity building involves support to public oficials on strategic planning; and support to low income communities towards the introduction and use of affordable and sustainable technologies like SSB.

Implementation of pilot demonstration projects comprises different steps, from consultation to construction of public utilities, housing and deciding on community priorities. Every step brings together government and stakeholders at various levels to agree on action plans and share responsibilities for implementation.

3.1 TRAining AnD cAPAciTy BUilDing

Several approaches to training have been applied in the different project components. Firstly, training for the communities focused on production and construction with stabilized soil block (SSB) as a way to mobilize communities to self-build their own infrastructures, shelters and generate livelihood opportunities.

Secondly, training was provided for public oficials responsible for designing and implementing pro-poor policies, supporting them with technical tools to carry out their responsibilities.

These approaches included some components related to technological innovation, including the search for alternative low cost sanitation, multistory buildings encouraging higher densities, and participatory design-planning.

3.1.1. TRAINING IN STABILIZED SOIL BLOCK (SSB) PRODUCTION AND CONSTRUCTION

SSB is a technique for mixing 5% cement with soil and minimum water and using a hand press machine to produce high quality and low cost building materials (Figure 18). They are 30% cheaper than ired bricks and also save on timber. The training in SSB was undertaken to help the residents of Mayo and El Rasheed to up-grade their houses using woodless construction tech-nologies. Using these bricks to build a 4x4 metres room, 14 fewer trees would be consumed than would be the case with ired bricks. SSB has been chosen due to its cost-effectiveness and environ-mental advantages.

figure 18. ssb hand pressing machines

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

20

The SSB course involved training a total of 123 selected trainees in all aspects of SSB production. The main aspects of SSB production which were covered included (Figure 19):

Soil selection and identiicationSoil testingProduction proceduresSSB curing procedures Field tests on SSB to enhance quality assurance

figure 19. Testing and dry mixing soil for ssb

Training in construction included the use of appropriate equipment to ensure accurate work (igure 20).

Training of professional masons to produce and build with SSB, facilitates the introduction of the technology into the construction market. It is expected that low income groups familiarized with SSB will develop an affordable housing market, facilitating self-help construction.

Furthermore, providing skills in SSB is expected to create income generation sources for low income communities and vulnerable groups.

figure 20. Training in innovative construction techniques

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 21

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

Families were organized in clusters selected by communities to be eligible for training in construction, and received a hand press SSB machine and cement for self-building their model houses and public utilities.

The training also included using alternative construction for rooing and plastering. Figure 21 shows SSB production and construction in Mansura

figure 21. cluster for ssb production and construction in Mansura

3.1.2. TRAINING IN ALTERNATIVE LOW COST SANITARY SYSTEM FOR URBAN POOR

Sanitation services were established in Khartoum in 1953-54 with a total network of 146 kilometres and 13 pumping stations to serve 80,000 people. Since 1971 no major development has been implemented to meet population growth. The sanitation network covers less than 15% of Khartoum state. Recently, German and Turkish companies have completed two treatment stations in Soba, working on the activated treatment plant system. Their daily capacity is 40,000 m.

Although available technologies are affordable for those urban poor owning land, they have some disadvantages: the use of pit latrines and septic tanks in certain areas is unsafe for ground water, especially when forbidden drilling machinery is used (Figure 22).

figure 22. Use of forbidden digging machines that contaminate the ground water

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

22

While the lack of available funds hampers the extension of the sewer network, it is also the case that in one sense the poor may be disadvantaged by its extension, because of the direct costs of treatments and their effect on land prices. The most affected group is the squatters, who are densely concentrated in areas with scarce services where people drink contaminated groundwater.

The project introduces a pilot low cost sewage waste and water treatment system, serving a considerable number of the urban poor. The aim of this pilot project is demonstration, on the job training in the new technology, feedback, assessment, and ultimately scale up.

Research on alternative designs and technologies has been done considering different social, inancial and maintenance aspects, recommending technical speciications appropriate to the different low income groups being assisted.

In parallel, training for masons and specialists in construction has been conducted, guiding them on how to make slabs for pit latrines that use less material, particularly cement and iron, and that can be industrialized to be transported or produced in situ (Figure 23).

figure 23. Training in alternative sanitation technology

3.1.3. TRAINING IN FLOOD RESISTANT HOUSING AND LAND TENURE LEGAL ACCESS.

In the last decade and onwards, demolishing sub-standard settlements, including IDP camps, has received ample criticism. UN agencies and the Khartoum authorities reached a consensus about the need for reviewing relocation policies in the legal framework of the Guiding Principles for Relocation (GPR). Land titles were given to many urban poor including IDPs while most of their houses built of mud and plastic sheet were demolished or removed. As annual rains and loods destroy many mud houses (Figure 24), further humanitarian assistance has been required for the affected population.

figure 24. Map of areas liable to looding in Khartoum and lood scene in Mayo

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 23

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

The high cost of construction materials and lack of affordable inancial mechanisms make it dificult for poor families to afford the traditional self-building process. Consequently, the average length of time to build even a single room is four years.

The project aims at improving poor peoples access to decent habitat in a participatory manner. It involves the development of alternative housing schemes for land owners as well as explanations on procedures to access secure land tenure following legal registration, and provision of low cost sanitary systems. Self-help housing initiatives from poor families were supported by the project, creating neighbourhood clusters sharing SSB hand press machines, cement and construction tools managed by a trained CBO and local organizations.

In addition the project provided technical advice on house layout, introducing familiar expansion perspectives related to the construction of additional rooms.

Special consideration was given to lood resistance strategies (Figure 25), such as elevated loor and concrete foundations, in order to minimize and delay the damage produced by looding and the risk of collapse.

figure 25. flooding resistance strategies incorporated in model housing design

3.1.4. TRAINING IN MODEL HOUSING AND MULTISTORY BUILDING DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION

Alternatives for building a sample of model houses have been explored. Families living in temporary shelters (Figure 26) were identiied to build housing prototypes consisting of two rooms, a kitchen, latrine and a veranda (igure 27). A prototype of reinforced slabs and external staircases (Figure 28) for low income groups living in multistory buildings was also included.

figure 26. A family living in temporary conditions before self-building a model house

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

24

It is assumed that densiication of low income neighbourhoods will happen anyway. As it is not possible for the urban poor to expand their houses vertically, they do so horizontally; either occupying all the plot without leaving space for income generation activities or building badly ventilated and overcrowded rooms. Figure 26 and 27 show living conditions, before and after the upgrading of a house, from one made of temporary materials to one built of durable affordable materials (SSB).

Participatory design assists in inding tailor-made solutions to the speciic needs, preferences and inancial possibilities of the targeted groups.

figure 27. Image of the model house built by the family presented in igure 26

figure 28. Proposed design for multistory low income housing: Ground loor, irst and second loor plan and perspective of a multistory model house

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 25

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

3.1.5. TRAINING IN PARTICIPATORY PLANNING AND DESIGN

After applying RUSPS (Rapid Urban Sector Proile for Sustainability), the project provides mechanisms for the continuing involvement of the community in designing and planning to build their basic infrastructure and facilities.

This requires a systematic approach to participatory planning and design at the community level, coordinated with the rest of the metropolis.

Support for design and planning is required, including technical backstopping on construction of model houses, sanitation, etc.

3.1.6. TRAINING IN STRATEGIC PLANNING

Strategic planning is an innovation globally, but is particularly new in the context of Sudan. For decades urban and regional planning has followed a traditional system of subdividing land according to three categories: First, second and third class. As was explained earlier, this system was applied during colonial times to separate the inhabitants: First class corresponded to the English, second class to the Egyptians, and the third class to those local Sudanese who cooperated with the colonial power.

This system, still ongoing, links parcel size and location with income level and lease periods. Those inhabitants with higher incomes access bigger plots in more centralized areas for longer periods, while the poorest hardly access smaller plots for shorter periods on the periphery of the city.

Beyond the formal planning system which regulates land subdivision and uses, the informal system responds to the need of those out of the system. As opposed to traditional planning, strategic planning calls for the participation of multiple stakeholders in addition to the state. A comparison between traditional and strategic planning is presented in Table I.

TABle i: cOMPARisOn BeTWeen sTRATegic AnD TRADiTiOnAl PlAnning

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

26

Taking into consideration these characteristics of strategic planning, its application in the context of Khartoum requires a strategy to introduce its new concepts, delivering better services for the majority of the population. In other words, it is expected that it will develop capacity to design and implement pro-poor policies. Strategic planning components can be summarized in three major concepts: speciic goals, realistic timing and a pro-active attitude, leading to public participation and community mobilization (Figure 29). This approach, involving the participation and mobilization of the community, in support of strategic planning, has two key elements. Firstly, it enhances the application of more lexible building regulations, based on incentives, in order to reduce construction costs to levels that low-income groups can afford.

The development of the diagnosis and pro-poor policies has shown how a signiicant percentage of the poor are unable to self-build their houses and basic public services because of strict building regulations, which rather than encouraging them to improve their living conditions, restrict them as they establish requirements out of affordable standards.

figure 29. Major components of strategic planning components for Khartoum structural Plan (KsP)

The key to pro-poor policy was simply to make more lexible regulations related to building construction, land uses and subdivision, providing incentives to carry out public priorities.

However, lexible regulations are only a irst step in the right direction. It is also important to carry out strategic public works, like drainage in looding areas, and encourage public-private partnership for the beneit of the poor, such as developing new markets and alternative action plans involving several stakeholders.

This action needs to be supported by further transparency in the planning process, communicating properly and encouraging governmental accountability and community ownership. These changes can only be achieved by introducing effective monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, supported by information technology and data collection, analyzed to identify trends that will guide all stakeholders.

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 27

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

figure 30. Prioritization exercise in a community consultation meeting

he participation of minorities and ordinary people, giving them a voice and a vote, equal to that of powerful

stakeholders, is a crucial aspect to take into account in the context of Sudan.

The participatory exercise, keeping records of all opinions and promoting discussions on priorities, laid the foundation for social agreement and commitment to implementing action plans (Figure 30). Agreement on priorities establishes the starting point to demonstrate through concrete actions the advantage of participatory planning over traditional modalities. Agreement also provides the necessary basis to make action feasible, minimizing conlicts that can arise from conlicting interests.

The participation of minorities and ordinary people, giving them a voice and a vote, equal to that of powerful stakeholders, is a crucial aspect to take into account in the context of Sudan.

figure 31. Participation of women in a consultative meeting

Experience has shown that the presence of women and womens associations during consultative activities introduces a crucial dimension to interpreting urban problems. Micro-inance, health, education, youth problems and environment were some areas in which inputs from women were highly appreciated and had a strong inluence on inally agreed priorities (Figure 31).

A methodology of strategic planning for small and medium-sized cities and villages has been developed in consultation with different stakeholders (Figure 32)

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

28

figure 32: strategic planning methodology for small cities and villages

The methodology presented to formulate strategic planning for villages and small cities includes a model process of interaction among involved stakeholders. It starts with sectorial studies on four subjects: urban indicators, a shelter policy paper, a basic urban service (BUS) policy paper, and an economic policy paper. A consensus among technicians on the major causes underlying poverty and segregation is achieved. There is also systematic data collection and SWOT (strength, weakness, opportunity and threat) analysis, with results summarized in a position paper. This stage is very important because it deines clearly the reasons that underlie poverty and segregation, identifying factors which have shaped the different categories of the urban poor.

Recommendations from the position paper are critical to engage communities in discussion, not only in terms of problems, but also about priorities and possible action plans. The presentation of this paper to the different communities involved constitutes the step of consultation, obtaining feedback to develop the draft strategy that will work as the skeleton of the plan. This consultation can assume different forms: a special session or a series of activities culminating in a inal open discussion, depending

on the characteristics of the village or small city. The inal step consists of the oficial approval of the strategic plan, plus the action plan, showing concrete interventions to address priorities agreed locally. In the context of Sudan, a national conference has been proposed to disseminate lessons learnt and goals achieved, contrasting the results with those of other regions.

he inal step consists of the oicial approval of the strategic plan, plus the

action plan, showing concrete interventions to address priorities agreed locally

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 29

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

3.1.7. TRAINING IN DATA ENTRY AND GEOGRAPHY INFORMATION SYSTEM (GIS)

Twenty students from the University of Al Azhari have been trained in data collection and ive staff from the Ministry have been trained in data entry and processing. The stage of data collection was completed for Jebel Awlia (Figure 33) and Dar El Salaam towns, and the following villages: Feteeh El Agalean, Al Lydia, Gabbel Gay, Abu Deraes and Sheikh Hamid. This stage started by designing questionnaires for villages and towns (see annex) in consultation with the team members and stakeholders. Several meetings were held with local administrations and CBOs (popular committees) to engage them in the process of participatory data collection. Data collection for the rest of the villages and one town was started in the second half of March 2010.

he expected outcomes of these exercises are: strategic and action plans for 12 settlements, including priority

development projects, manuals for preparation of strategic and local economic

development plans, data collected and compiled from various available

national and international sources

figure 33. example of digitalized map of Jewel Awlia

The expected outcomes of these exercises are:

Strategic plans for 12 settlementsAn action plan including priority development projects

Manuals for preparation of strategic and local economic development plans;

Data collected and compiled from various available national and international sources (maps, tables, data and Google earth), converted into shape iles and digital data that can be handled and displayed on the computer program (Arc GIS) for the purpose of study and analysis.

Control points speciied on maps have been reviewed through site visits to make sure they are correct. Control points made up the database (according to topology speciications) to determine areas and dimensions (Figure 34). Spatial data has been extracted from Google Earth images, site visits and GPS.

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

30

figure 34. land use map and location of social services in Jebel Awlia.

The service facilities have been visualized on the map using GPS for accurate determination of coordinates. Thematic maps were then created with various layers of spatial and non-spatial data. Some of the layers have already been completed while others are still being processed. The database contains the following information (Figure 35)

Contour linesroad networklood zoneUrban communities which already exist (residential area)

industrial , agricultural and tourism sitesa layer for land use informationa layer for information on the distributions of various health centres, hospitals and clinics

Education facilities, etc.

figure 35. GIs map showing looding- prone areas

3.1.8. ACTION PLAN FOR CAPACITY BUILDING

As part of an action plan for capacity building, pilot projects have been designed in speciic locations, selected according to the results obtained in the RUSPS exercise. These pilot projects seek to demonstrate (in a speciic case) the application of all the recommendations on pro-poor policies and community actions, including self-help construction and different technological alternatives.

The idea behind the pilot projects is that different low income participating groups can easily identify alternative solutions to their habitat and livelihood problems. These pilots also offered a unique opportunity for the training and capacity building of public oficials, providing them with inputs on methodologies and approaches to carry out local economic development strategies.

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 31

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

he idea behind the pilot projects is that diferent low income

participating groups can easily identify alternative solutions to their habitat and livelihood problems

A manual for development of strategic planning exercises in the context of Sudan in general, and Khartoum in particular, has been prepared. This manual is used in the interactive workshops, giving to the participants the chance to consider their experiences and elaborate alternatives in order to move forward in local development plans.

The integration of the most vulnerable and disadvantaged groups is highlighted as the cornerstone of the plans, making use of traditional community mechanisms (Figure 36) of identiication and support, seeking to empower communities to ind self-help solutions to their different problems.

figure 36. Discussion and agreement between communities and government representatives

3.2. PILOT PROJECTS

The comprehensive upgrading of informal settlements by UN-Habitat has involved the development of pro-poor policies, training in capacity building for the Ministry of Planning and Urban Development (MPUD), and the implementation of RUSPS in selected informal settlement areas.

The purpose is to understand their socio-territorial dynamics so as to set up participatory mechanisms for development. Taking into account the outcomes of the sector studies carried out at State and local levels, speciic issues blocking the delivery of urban services for the poor have been identiied, relating to spatial planning, land management, social housing, basic urban services, environmental problems and weak local economic development.

Approaches to spatial planning and land management have been tested by the pilot projects, taking into account the spatial limits to the development of the social fabric, considering particularly their locations. Land management problems have been addressed through a follow-up land registration and titling process, ensuring that beneiciaries enjoy secure land tenure, preventing further evictions.

Land management problems have been addressed through a follow- up land registration and titling process, ensuring

that beneiciaries enjoy secure land tenure

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

32

In addition, self-help housing has been particularly considered through different approaches, taking into account their affordability for different social groups:

A. The supply of subsidies for the most vulnerable households.

B. A middle term solution called The three block approach which targets those households without permanent employment but with capacity to work. This allows them to pay the cost of the lease of the SSB making machines and cement by providing blocks for the construction of public utilities. Every third block they make, they can sell it in the market as an income generation source.

C. Credits provided in partnership with the Social Development Foundation (SDF), targeting those households able to pay back in cash instalments.

Three pilot projects have already been implemented. The irst case is Mansura (Figure 37), a neighbourhood close to the city centre with a high level of squatter activity. Here the MPUD is providing land titles. The second case, Mayo-Mandela (Figure 38), was an IDP camp which the MPPPU subdivided to provide land titles to eligible families, according to their arrival date. The third case, Al Rasheed in Jebel Awlia (Figure 39), on the periphery, houses families evicted from IDP camps and several squatter areas. Here land titles, water and some social services are provided, but there is no provision for building permanent houses.

figure 37. Mansura

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 33

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

Self-help housing has been particularly considered through diferent approaches, taking into account their afordability for diferent social groups

figure 38. Mayo-Mandela

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

34

figure 39. Rasheed in Jebel Awlia

3.2.1 BRIEF DESCRIPTION

RUSPS was applied in three locations (Al Bashir, Fitehap and Jebel Awlia), including a survey of slums that provided key socio-territorial data for developing an upgrade strategy.

Based on RUSPS exercises and monitoring the Guiding Principles for Relocation, SSB was introduced to support communities so they could afford basic services and self-build housing. The location of the different pilot projects is presented in Figure 40: Mansura, close to the city centre; Mayo-Mandela, on the edge of the city; and Jebel Awlia, on the extreme periphery.

figure 40. location of pilot projects

A summary of the different pilot projects is presented in table II.

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 35

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

lOcATIOn POPUlATIOnAReA

HIsTORIcAl bAcKGROUnD

eTHnIc cOMPOsITIOn

MAJOR PRObleMs

MInOR PRObleMs

Mansura

14,000 inh

1,3 sq km.

Agricultural land, originally.

Low topographical level subjected to recurrent looding.

Informal settlement of landless poor and IDPs in the 80s

In 1995 was a target for re-planning

In 2000, plots were granted to resident communities. Extension of water-electricity.

Residents from all parts of Sudan, mostly from Nuba mountains, Darfur and Kordofan.

Frequent looding.

Poverty associated with high unemployment rate.

Lack of skills to generate income in urban areas.

Limited services. Disconnection from major urban services network.

Extension of African road linking the area with the consolidated city.

Land value increase, encouraging commercial activities.

Mayo-Mandela50,000 inh1,9 ha.

1993/2 One of the designated IDPs camps accommodating people displaced because of drought.

In 2008 re-planning started and is still ongoing.

Congested with poor health and environment.

Residents from all parts of Sudan, but mostly from the 10 States of Southern Sudan

Recurrent demolition threat.

High cost of construction materials, making housing unaffordable.

Use of mud and consequent building collapse.

Poverty due to lack of skills to compete for urban jobs.

High transportation costs

Small market creating positive dynamics for income generation schemes and reduction in the price of basic goods

Proximity to Al Bashaier hospital, providing special coverage in health.

Main road constructed along Mayo (North South, East-West)

Rasheed, Jebel Awlia40,000 inh 3 ha.

Relocation area(2005).

Planned relocation of 8000 families from informal settlements, mainly from Soba Aradi (2009).

Part of Sundus agricultural scheme

Residents from all parts of Sudan with the signiicant and increasing mixture of ethnic groups.

Remote location.

Lack of livelihood opportunities.

Poor housing.

Expensive pit latrines.

Presence of mosquitoes because of proximity to the river

Access to agricultural scheme.

Availability of casual labour in agricultural scheme.

Renting land as income generating scheme.

TABle ii: BRieF DescRiPTiOn OF THe THRee PilOT PROjecTs

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

36

Table II presents a brief historical background to clarify how the combination of different factors has led to current problems and opportunities. According to their different location within the metropolitan structure, the three pilot projects have different advantages and disadvantages as regards integrating their residents into the network of opportunities provided by the city.

Mansura, a low-lying area, was originally used for agriculture, beneiting from recurrent looding. However, during the 80s, as a result of the massive migration of IDPs to Khartoum from all regions of Sudan, and particularly from the Nuba Mountains and Kordofan, the area was populated informally. This original pattern of informal settlement has turned the area into a marginal one.

The strategic location of Mansura, close to the urban framework (Figure 41), has attracted signiicant waves of IDPs and landless poor leading to rapid growth, congestion and overcrowding. There is, in addition, the risk of housing collapse as houses are made of mud, seriously damaged during looding periods. In 1995, Mansura was oficially declared a re-planning area, initiating a process of eviction and upgrading. In 2000, some plots were granted free of charge, and water and electricity services were provided, signiicantly improving living conditions in the area.

This process was a step forward, formalizing the urbanization process by integrating the area into the urban fabric, although it still faces looding problems. Poverty in this neighbourhood is mostly associated with unemployment and residents lack of skills to get jobs in urban areas. Despite these dificulties, the area is actually going through a revitalization process associated with the extension of the African highway that facilitates its link with the city centre.

The location of residential complexes for high income groups near the zone evidences an increasing real estate trend, with potential for land speculation that might drive the poor out of the area.

figure 41. Mansura urban pattern and layout plan

Mayo-Mandela was an oficial IDP camp in 1992-3 intended to accommodate displaced populations from all parts of Sudan, but particularly Southern Sudan. This has shaped the area as a well organized and delimited territory where the poor can stay temporarily, receiving social services such as education, health and food. However, as happens with camps, there are restrictions on building permanent constructions and the poor supply of urban services and infrastructure make the area particularly vulnerable. With the passing of time, Mayo-Mandela has become congested and unhealthy, and there has also been growing confrontation between different ethnic groups living in the area, and with the rest of the city.

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 37

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

In 2008, a re-planning exercise was launched, relocating some of the people (Figure 42), regularizing some areas and delivering plots to existing residents. A summary of its major problems points out the lack of housing facilities, which started to be solved after regularization, a process to provide access to secure land tenure for residents.

However, there is a major obstacle to establishing permanent constructions as available materials are unaffordable for the residents. Here too, the use of mud puts at risk the stability of construction, demanding its immediate replacement by permanent materials. This area also suffers poverty associated to the lack of income generation skills, and in contrast to Mansura, which is well connected, Mayo-Mandela suffers further segregation as a result of the lack of affordable and adequate public transport.

As regards opportunities available in the area, there is a market, facilitating access to cheap basic goods and the creation of employment and income generation sources. In addition, the presence of Al Bashaier hospital, serving a wide area, provides medical services for the population.

figure 42. Urban pattern of Mayo-Mandela camp

As is the case in Mansura, some ongoing public works, such as the road North-South and East-West, are creating new opportunities for the zones development.

Rasheed, in Jebel Awlia, is an example of a relocation area created in 2005. Its remoteness from Khartoums urban fabric was seen as a major obstacle to poor families, who had previously lived in the city. Relocating poor families to remote area has had very negative consequences in the past, as many relocation areas have failed to create minimum survival possibilities.

In 2009, in a context of confrontation and political crisis, 8000 families evicted from several informal settlements, mostly from Soba Aradi and part of Sundus, settled in Rasheed. The challenge of creating a vibrant multicultural and diverse community in Rasheed was also threatened because the building of pit latrines close to the river made people more exposed to mosquitoes and the spread of diseases.

Despite all these dificulties, the supply of some basic services, like opening a regular gridline of roads, the grant of third class plots, and the presence of a market and schools, have succeeded in maintaining the 8000 families in the area, attracting services like daily transport to Khartoum.

Moreover, the development of agricultural schemes provides some casual work, alleviating the crisis associated to the lack of other job skills. Some efforts to connect the area to Jebel Awlia have contributed to creating positive synergies for local economic development, linking the area to its region.

The territorial pattern (Figure 43) evidences a rapid process of urbanization expanding over agricultural land.

-

United nations Human settlements Programme

Regional Ofice for Africa and the Arab States

38

3.2.2. MAJOR COMPONENTS OF THE PILOT PROJECTS

The pilot cases were selected precisely because they represent a very typical scenario of problems and opportunities for the reintegration of the poor into the development process. Location plays a crucial role as it provides the necessary subsidized resources to encourage self-help work at individual and community basis. The key factor underlying the rationale of the pilots is identifying the most effective ways of guiding collective efforts towards the sustainable progress of the areas.

In the case of Mansura, regularization and re-urbanization have been enough to initiate a positive transformation. The main problem is that due to its advantageous location it is favorable to property speculation. There is pressure on real estate prices and this is driving the poor out of the neighbourhood. This demands a clear pro-poor policy, linking land, infrastructure, livelihoods, environment and an inter-ethnic understanding. In such a context the pilot exercise is particularly valuable allowing the validity of its approach to be tested under speciic circumstances.

Mayo-Mandela has an intermediate location, not too close, not too far from the city. However, its history as a former IDP camp, and the dramatic experience of recurrent eviction very much affects its prospects for positive transformation. The regularization of some plots has raised the communitys hopes that the neighbourhood will be formalized. The process of re-urbanization, providing some urban services, has already led to impressive progress compared to the previous scenario of isolation and poverty.

Rasheed is the most disadvantageous case, because of its remote location and the impossibility of linking urban to rural livelihood opportunities. However, the introduction of resources and training in construction (Figure 44) to carry out public and private construction, has had a positive impact, revitalizing the local economy and signiicantly improving living conditions.

In all three cases, the design of the pilot projects integrates some common approaches, linking governmental and community efforts and supporting a strategy for positive transformation. This latter involves empowering communities to become active partners in governmental pro-poor planning efforts. A summary of the major components of the pilot projects is presented in Table III.

figure 44: self-help construction in Jebel Awlia

-

FROM POLICY DESIGN TO PILOT IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS 39

KH

AR

TO

UM

PR

O P

OO

R

lOcATIOn OUTPUTs APPROAcHlOcAl

PARTneRsDOnORs ReMARKs

Mansura Self-help for rooing

Micro-credit TRI, Locality, Popular committee, the MP&UD and SDF

EC Housing support provided to selected families

Kindergarten, health centre and womens centre

Subsidy EC and Italian Development Cooperation

Complex for support of special neighbourhood needs, including a small clinic and a public garden, built with SSB

Recreational public garden

EC An open space for special activities targeting the youth

Sewage and drainage system

EC and Italian Cooperation

Introduction of an innovative system to channel storm water

Mayo-Mandela 200 self-help houses

Subsidy and micro-credits

TRI, Locality, Popular committee, the MP&UD and CBOs

Italian Cooperation

Roof and materials. UN-Habitat provides technical backstopping, plus SSB making machines

Two primary schools

Subsidy TRI, Locality, Popular committee, Privates and CBOs

Mayo Mandela Block 007 (in partnership with Italian Cooperation)

Mayo Dar El Naeem (UN Habitat in partnership with Italian Cooperation)

Rasheed Six model houses Subsidy TRI, Locality, Popular committee and the MP&UD

EC and Italian Cooperation

Showing different typologies

One multistory building

Subsidy Demonstrate advantage of growing vertically rather than horizontally

Sanitation system Subsidy Introducing a different design, which saves material and is easy to transport

500 pit latrines In kind EC plus the Italian Cooperation

Industrialization of pit latrine

400 houses Three block approach

Neighbour clusters producing SSB and housing, self-construction per household

Planting 1000 trees, greening the area

Subsidy Ministry ofAgriculture

EC and Ministry of Agriculture

Community mobilization for planting and irrigation.

TABle iii: MAjOR cOMPOnenTs OF THe PilOT PROjecTs

-

United nations Human settlements Programme