JP Morgan_EUzone Painful Path to Eurobonds_Jan-1-2012

-

Upload

hansparisi -

Category

Documents

-

view

67 -

download

0

Transcript of JP Morgan_EUzone Painful Path to Eurobonds_Jan-1-2012

www.morganmarkets.com

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonEconomic ResearchFebruary 1, 2012

The Euro area’s painful path toEurobonds• This week the Euro area agreed on the details of the new fiscal com-

pact, which attempts to put the region on a path to a low debt equi-librium. The objective of the debt rule is to reduce sovereign debt to60% of GDP. Balanced budget rules embedded in primary legisla-tion are intended to keep sovereign debt at a low level once the newequilibrium has been reached.

• The decision to move to a low debt equilibrium reflects a recogni-tion that sovereign debt in the Euro area contains credit risk. Historysuggests that investor appetite for sovereign debt with credit risk islower than it is for sovereign debt with currency risk. If credit risk isretained, sovereign debt needs to be reduced significantly, to a levelat which it can be sustainably financed in private capital markets.

• In order to reach 60% of GDP, sovereign debt in the Euro areaneeds to decline by around €3 trillion (30% of GDP). Although thisdegree of deleveraging looks huge, it is probably achievable for theregion on average, if spread over a long enough period of time. Thekey problem is not the average adjustment, but rather its distributionacross the region. Germany already has a fiscal position that wouldmeet the new debt rule. For France and the periphery, the requiredfiscal adjustments to meet the debt rule are very large.

• Fiscal austerity in France and the periphery will weigh heavily onnominal growth, with an extended period of weak real growth andvery low inflation. With credit risk in sovereign debt, averaging bor-rowing costs are likely to remain high, which makes the fiscal jour-ney even harder. Unemployment rates across the periphery will con-tinue to move up. In Spain, for example, overall unemployment willlikely exceed 30%, with youth unemployment approaching 60%.

• At some point the region will decide that taking credit risk out of sov-ereign debt via a move to Eurobonds is preferable. By pooling thecreditworthiness of countries in the region, Eurobonds limit theamount of sovereign deleveraging that is needed.

• Fiscal policy at the national level would still need to be controlled ina world of Eurobonds. Broadly speaking, there are two options.

• One option is to socialize existing debt and allow future debt to beissued that still contains sovereign credit risk. Fiscal policy would bemanaged by some combination of rules and market pressure. US statefinance from 1790 can be viewed as an example of this approach.

• The other option is to socialize both existing debt and new debt,with future access to credit controlled by a central debt managementagency. Australian state finance from 1927 can be viewed as an ex-ample of this approach. A centralized debt management agencycould also be viewed as a mechanism to generate fiscal transfersacross the region, with allocations of credit across countries adjustedfor cyclical and structural divergences.

David Mackie(44-20) [email protected]

Malcolm Barr(44-20) [email protected]

Nicola Mai(44-20) [email protected]

2

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Barr (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchThe Euro area’s painful path to EurobondsFebruary 1, 2012

Contents page

Introduction and overview 2

The low debt equilibrium of US states 3

Equilibria for sovereign debt with credit risk 4

The Euro area is currently aiming for a low debt

equilibrium 5

Will the journey to a low debt equilibrium

succeed? 7

The stability of Euro area debt dynamics 10

A change in direction to Eurobonds 12

The Australian model of centralized access

to credit 13

Also a shift toward fiscal transfers? 14

How could all this work for the Euro area? 15

References 15

Introduction and overviewThe Euro area crisis is complex. Sovereigns and banks both face funding issues, andperipheral economies face growth and competitiveness problems. This week’s EUsummit reached an agreement on a new fiscal compact to deal with the budgetaryaspect of the crisis. The new fiscal compact aims to put the region on a path to a lowdebt equilibrium, reflecting the fact that sovereign debt in the region includes creditrisk. This note focuses on the magnitude of the fiscal journey ahead and the likeli-hood that the fiscal compact will achieve its objectives. The note does not deal withthe other problems that the region faces: overleverage in banks (also related to a rec-ognition of credit risk), and intra regional private sector imbalances and competitive-ness problems.

In the sovereign space, recent developments have reinforced two features of theoriginal architecture of EMU which were forgotten during the monetary union’sfirst decade: the introduction of PSI indicates a reluctance to engage in permanentbail outs, while the ECB’s stance indicates its commitment to no monetary financ-ing of fiscal deficits. These features—which were part of the original 1992Maastricht treaty—indicate that sovereign debt in the Euro area includes credit risk.Historic experience suggests that investor appetite for sovereign debt with creditrisk is much lower than it is for sovereign debt with currency risk.

If this diagnosis is correct, then the region needs to get to one of two destinationsfor the monetary union to be sustainable in the medium term: either a situationwhere debt levels are low enough to enable sovereign debt with credit risk to befinanced in private capital markets; or a situation where credit risk has been re-moved by a move to joint and severally guaranteed Eurobonds.

At the moment, the region is attempting to move toward the first of these destina-tions: a low debt equilibrium. The new fiscal compact includes a debt rule whichaims to reduce debt to GDP ratios to 60% over time. This is probably a level wheresovereign debt with credit risk could be sustained in private capital markets. Thenew fiscal compact also includes a commitment to embed balanced budget rules inprimary legislation in order to keep debt levels down once the low debt equilibriumhas been reached. The objective of low debt levels, alongside the idea of local au-tonomy constrained through constitutional mandates, looks similar to the situationfor US states.

Reducing debt to GDP ratios to 60% would take a long time, and the journey wouldbe very painful—economically, politically, and socially. Importantly, the painwould not be evenly distributed across the region: for some countries, the requiredfiscal adjustment to meet the debt rule is modest, while for others the required fiscaladjustment is likely to be intolerable. Moreover, a prolonged period of sovereigndeleveraging will run alongside a prolonged period of bank deleveraging, whichwill add an additional headwind to growth. Meanwhile, during the transition to amuch lower level of sovereign debt, significant amounts of official financing,whether from the EFSF/ESM, the IMF or the ECB, are likely to be needed. Thismeans that there will be a significant substitution of official liabilities for marketdebt in a number of countries in the periphery. Reversing this socialization of sover-eign liabilities will be very difficult.

3

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Mai (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchGlobal IssuesFebruary 1, 2012

In our view, the region will decide to change direction at some point, for at leastthree reasons. First, a recognition that Eurobonds are a better destination for theregion than a low debt equilibrium. Second, a recognition that centralized control ofthe access to credit will be more successful in constraining national fiscal policy ina world of Eurobonds than fiscal rules. And third, a recognition that fiscal transfersare the quid pro quo for the loss of fiscal sovereignty at the national level, and thatthese can be generated through a centralized debt management agency.

Although we believe that this change in direction will take place—toward Euro-bonds with centralized control of the access to credit and some fiscal transfers—it isunlikely to occur quickly. The crisis is forcing through fiscal and structural reformsthat should have taken place years ago. With Germany and the Netherlands now theonly large AAA sovereigns left, they will have increased leverage to force throughthe reforms that they believe are necessary before accepting a move to Eurobonds.Our central view is that only when it is apparent that the current approach is gener-ating a painful, lost decade for the region—with significant political and socialstress—will the change in direction occur. The precise timing is unclear, however,and could well be affected by political changes across the region as well as eco-nomic developments. If the socialists win the upcoming election in France, theywill almost certainly put pressure on Germany and the Netherlands for a quickerchange in direction than would otherwise happen.

The low debt equilibrium of US statesIn the US fiscal union, states are in a low debt equilibrium. State and local taxes andspending are around half the level of federal taxes and spending, indicating a signifi-cant degree of fiscal decentralization. But, it is clear that US states face a hard budgetconstraint. Over the past decade, federal level debt has doubled, from 33% of GDP to67% of GDP, while state and local debt has remained broadly stable at around 13% ofGDP (excluding the impact of data revisions in 2004 which permanently lifted thelevel of state and local debt by around 6% of GDP). The stability of state and localdebt is not due to an elaborate degree of coordination between the federal governmentand the states. Instead, it is due to the existence of binding budget rules at the statelevel which limit the ability of states to run deficits and issue debt.

0

20

40

60

80

100

70 75 80 85 90 95 00 05 10

% of GDP

Sovereign debt: Euro area governments and US states

Euro area governments

US states

The US state and local government data were revised up by an average of $840bn from 2004 onwards,reflecting new data on municipal securities and loans.

4

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Barr (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchThe Euro area’s painful path to EurobondsFebruary 1, 2012

Theses balanced budget rules initially came out of the 1840s fiscal crisis when thefederal government refused to bail out states which had built up local debts andwere looking for a federal bailout. As a consequence of the lack of federal support,eight states and one territory defaulted on their debt. In order to reassure investorsin an environment where credit risk clearly existed in the sovereign debt at the statelevel, states began to develop balanced budget rules as a commitment device tolimit excessive borrowing. This trend continued as new states entered the Union,and after the 1870s defaults by southern states.

All US states, except Vermont, have balanced budget rules for their general fund(i.e., state finances excluding capital expenditure, pensions, and social insurance).But the specific form of the rules differs across states in a number of respects: theycan be embedded either in primary legislation (state constitutions) or in secondarylegislation (acts of the state legislature); and they may apply to the ex ante pro-jected budget deficit or to the ex post realized budget deficit, with differing require-ments on how unanticipated deficits in the former are corrected. All of the rules areoverseen by the respective state supreme courts. Many states also face constraintson issuing long-term debt for capital projects.

Academic research suggests not only that these rules matter but also that the spe-cific form of the rules matters. Looking at the experience of US states, Bohn andInman conclude that rules based on “an audited, end-of-the-year fiscal balance aresignificantly more effective than constraints requiring only a beginning-of-the-yearbalance;” that “those states whose supreme court justices are directly elected by thecitizens have ‘stronger’ constraints (i.e., lead to larger average surpluses) than thosestates whose supreme court justices are direct political appointments of the gover-nor or legislature;” and that “there is tentative evidence that constraints grounded inthe state’s constitution are more effective than constraints based upon statutory pro-

Equilibria for sovereign debt with credit riskUS states are one example of a low debt equilibrium for sovereign debt with creditrisk. At the moment, US states have debt outstanding worth around 20% of GDP,and the average of the past three decades has been 15% of GDP (both of these fig-ures include the impact of data revisions in 2004 which permanently lifted the levelof state and local debt by around 6% of GDP). The level of US state debt is wellbelow what the Euro area debt rule would deliver.

EM foreign currency debt is another example of sovereign debt with credit risk. Aca-demic work suggests that the appetite for such debt is much lower than it is for DMdomestic currency debt which does not have credit risk. The IMF has analyzed thisissue at length. One piece of IMF analysis suggests that there is a 50% probabilityof an EM debt crisis if the level of debt exceeds 80% of GDP in the previous year(“Cross-Country Experience with Restructuring of Sovereign Debt and RestoringDebt Sustainability”, IMF, August 2006). More recent analysis puts the maximumsustainable debt range for EM countries at between 60% and 80% of GDP (“Mod-ernizing the Framework for Fiscal Policy and Public Debt Sustainability Analysis,”IMF, August 2011). EM experience suggests that if credit risk in the Euro area is re-tained, the debt rule would likely deliver a level of debt that would be sustainable inprivate capital markets.

5

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Mai (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchGlobal IssuesFebruary 1, 2012

visions.” (See H. Bohn and R. Inman, “Balanced Budget Rules and Public Deficits:Evidence from the US States,” NBER WP 5533, April 1996).

Clearly, these state level fiscal rules are important, but it has to be recognized thatthe efficacy of the balanced budget rules is reinforced by three other features of theUS system: first, there is a credible no bailout threat from the federal government,given the refusal of the federal government to bail out states over history; second,the sanctions in the US states for violating the fiscal rules are political rather thanfinancial; and third, there is a well established system of fiscal transfers to mitigatethe economic costs of fiscal constraints at the local level.

It is important to stress that the US has a very elaborate system of fiscal transfers,which redistributes income from wealthy to poor individuals and from wealthy topoor states.Some of this comes from the progressive federal income tax system, andsome comes from the distribution of federal expenditure (income for retirees, grants,procurement and wages for federal employees).

The Euro area is currently aiming for a low debt equilibriumAt the moment, the Euro area is trying to move toward a low debt equilibrium, in-spired by the US model of state level finances. This is evidenced by two features ofthe new fiscal compact initially revealed in December 2011. First, the debt rulewhich aims to reduce sovereign debt to GDP ratios down to 60%. And second, theintention to embed balanced budget rules in primary legislation in order to keepdebt at a low level. In such a low debt equilibrium, sovereigns would be comfort-ably funded in private capital markets and there would be no need for joint and sev-eral liability Eurobonds.

In order to reach a low debt equilibrium, where sovereign debt with credit risk can befinanced in private capital markets, actual debt levels in the Euro area need to falldramatically. And indeed, the Euro area is trying to achieve this. As well as rules onfiscal deficits, the region has also adopted a rule on debt. This states that countrieswith debt in excess of 60% of GDP need to put in place a fiscal stance which will re-

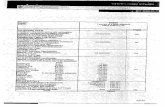

Adjustments to meet Euro area debt rule

% of GDP for deficit and debt

Debt at peak Primary position 2011

r = g r > g by 200bp r = g r > g by 200bp

Germany 83.2 1.3 1.2 2.9 -0.1 1.6

France 94.1 -2.8 1.7 3.6 4.5 6.4

Italy 125.7 0.5 3.3 5.8 2.8 5.3

Spain 84.5 -6.1 1.2 2.9 7.3 9.0

Netherlands 66.0 -2.4 0.3 1.6 2.7 4.0

Belgium 102.0 -0.4 2.1 4.1 2.5 4.5

Austria 73.7 -0.8 0.7 2.2 1.5 3.0

Greece 175.7 -3.0 5.8 9.3 8.8 12.3

Finland 53.5 0.1 0.0 1.1 -0.1 1.0

Portugal 128.8 -3.0 3.4 6.0 6.4 9.0

Ireland 131.0 -6.0 3.6 6.2 9.6 12.2

The debt rule states that any government with a debt-to-GDP ratio in excess of 60% needs to make an annual adjustment equal to 1/20th of the gap. "r“ is the average borrowing rate on debt, "g" is

nominal GDP growth. The Greek number exclude PSI. The Portuguese primary deficit in 2011 excludes one offs.

Primary position to meet debt rule Journey from 2011

6

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Barr (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchThe Euro area’s painful path to EurobondsFebruary 1, 2012

duce the gap between the actual level of debt and the 60% threshold by 1/20th ayear. The precise primary surplus that is needed to achieve this depends on the initiallevel of debt and the relationship between nominal growth and borrowing costs. Pri-mary surpluses would need to be maintained while debt is declining, but the magni-tude of the required primary surplus would gradually fall over time.

Meanwhile, the US experience with balanced budget rules at the state level looks tohave inspired the German approach to governance in the Euro area. The Germangovernment approached the December 2011 summit with one key objective: to em-bed balanced budget rules, which had a greater degree of automaticity regarding theimposition of sanctions, and which were overseen in their operation by the Euro-pean Court of Justice, into the primary legislation of the European Union (the trea-ties) and the nation states (the national constitutions).

It is important to stress that the substance of the fiscal rules discussed at the Decem-ber summit, and the manner in which the greater automaticity of sanctions would beachieved, had already been agreed in the governance reforms that had been final-ized in prior months. So what was the big deal about where these rules are locatedin legislative terms? In our view, the German perspective on the importance of pri-mary legislation, as opposed to secondary legislation or intergovernmental agree-ments, and the role of the European Court of Justice, can be understood by lookingat the literature on how state-level fiscal rules work in the US.

In the event, the German government only partially met its objectives at the summit.It was agreed that balanced budget rules, with an automatic correction mechanism,will be embedded into national legal systems at constitutional or equivalent levels.However, the role of the European Court of Justice was limited to the verification ofthe transposition of these rules at the national level, rather than being involved inthe ongoing monitoring of their observance. And, it was agreed that the fiscal com-pact—which also covers the use of reverse qualified majority voting in the excessivedeficit procedure, the commitment to reduce debt by 1/20th of the gap between theactual level and the 60% threshold per annum, and the reporting of ex ante debt issu-ance plans—will be contained in an inter-governmental agreement rather than in anew treaty at the EU level.

Borrowing costs and nominal growth in 2011

10 year bond yield 2011,

%

Average borrowing cost

2011, %

Nominal GDP growth

2011, %oya

Germany 2.65 3.0 3.9

France 3.31 3.3 3.2

Italy 5.29 4.2 1.7

Spain 5.45 3.7 2.2

Netherlands 2.96 3.1 2.8

Belgium 4.23 3.5 4.5

Austria 3.32 3.9 5.1

Greece 18.47 4.5 -4.1

Finland 3.00 2.4 6.0

Portugal 10.22 4.5 -0.5

Ireland 9.74 3.8 0.1

7

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Mai (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchGlobal IssuesFebruary 1, 2012

Will the journey to a low debt equilibrium succeed?In the event, we do not think that the Euro area’s journey to a low debt equilibriumwill be successful, for two key reasons. First, reducing debt to the extent that isneeded will be very painful—economically, politically, and socially, especially forthe periphery. The debt overhang in some countries is just too large. It is hard to seehow the region will survive a prolonged period of intense austerity around the pe-riphery, particularly coming so soon after the deep recession of 2008-09. And sec-ond, we do not think that the attempt to mimic the operation of US balanced budgetrules at the state level will be successful. US states are in a low debt equilibriumdue to a number of reinforcing features of the system in addition to the nature of therules themselves; notably, a credible no bailout threat, the nature of the sanctions,and the system of fiscal transfers.

For the region as a whole, meeting the debt rule would involve reducing the level ofsovereign debt by around €3 trillion (30% of GDP). This looks like a huge amountof deleveraging, but it is easier to achieve than might appear at first blush given thatthe debt rule allows this deleveraging to take place over a 20-year horizon. If theaverage borrowing cost is equal to nominal growth, then the region would need togenerate a primary surplus of 1.5% of GDP. This is only a move of around 3%-ptsrelative to last year’s primary position. This would represent a significant fiscaltightening, but something that could be achieved if spread over a few years. Theoverall growth environment is likely to be worse than this shift to fiscal austeritymight suggest, however, for a number of reasons: first, fiscal consolidation wouldweigh on both real growth and price inflation, which would make the debt dynam-ics more challenging; second, with credit risk remaining in sovereign debt, a riskpremium would remain in borrowing costs; third, alongside sovereign deleveraging,we anticipate that banks in the Euro area will also delever by around €1.5 trillion(15 % of GDP) which would add an additional headwind to growth; fourth, struc-tural reform is likely to weigh on growth before it delivers benefits; and fifth, thisdeleveraging is taking place against a backdrop of deteriorating demographics,which will both depress real growth potential and lift age-related public spending.Even so, if achieving a low debt equilibrium were simply an issue of the area-widesituation, it would be achievable.

Euro area 2011-12 recession in a broader context

GDP decline %

peak to trough

Duration of

contraction

quarters

Extent of weakness

% GDP t-2 to t+8

Unemployment

rate peak %

Mid-70s 2.5 2 7.1 4.0

Early 80s 0.5 3 1.4 9.9

Early 90s 1.9 4 1.1 10.8

2008-09 5.5 5 -3.2 10.2

Current forecast 0.7 4 0.3 11.0

The first column shows the % decline in the level of GDP from the peak to the trough. The second column

shows the number of consecutive quarters of GDP contraction. The third column shows the % change in the

level of GDP from two quarters before the start of the recession to eight quarters after the start of the recession.

The fourth column shows the cyclical peak in unemployment.

8

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Barr (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchThe Euro area’s painful path to EurobondsFebruary 1, 2012

However, the problem of reaching a low debt equilibrium relates to the distributionof the adjustment across the region, rather than to the average adjustment for theregion as a whole. If borrowing costs are equal to nominal growth, then Germanyalready has a fiscal stance that meets the debt rule. Even if borrowing costs exceednominal growth, the required fiscal consolidation in Germany is modest. And then, itsimply needs to sustain this primary surplus to reduce debt gradually over time. Fin-land also already has a fiscal position that meets the debt rule, and the required fis-cal adjustment in Austria is modest.

Elsewhere in the core, the task is somewhat more challenging. If borrowing costs areequal to nominal growth, France needs a primary surplus of 1.7% of GDP to meet thedebt rule. If borrowing costs exceed nominal growth by 200bp, it needs a primarysurplus of 3.6% of GDP. These compare with last year’s primary deficit of 2.8% ofGDP. Thus, in order to meet the debt rule, France needs to tighten fiscal policy sig-nificantly and sustain a sizeable primary surplus for the indefinite future. It is worthnoting that in the three decades through to 2008, France ran an average primary defi-cit of 0.7%, and the largest primary surplus it ever achieved was 1.2% of GDP, whichwas sustained for only two years.

The fiscal adjustments that are needed to meet the debt rule across the periphery arelarge. For peripheral sovereigns that continue to finance themselves in private capi-tal markets—say Italy, Spain, and Belgium—borrowing costs are likely to exceednominal growth. If this gap is 200bp, then the fiscal journeys are huge. Italy wouldneed to move its primary position from last year’s surplus of 0.5% of GDP to a sur-plus of 5.8%; Spain would need to move its primary position from last year’s defi-cit of 6.1% of GDP to a primary surplus of 2.9%; and Belgium would need to moveits primary position from last year’s deficit of 0.4% of GDP to a surplus of 4.1%.These primary surpluses would then need to be sustained for the foreseeable future.

For those peripheral sovereigns who are in a liquidity hospital, where borrowingrates are subsidized, the fiscal journeys are still huge. Policymakers have alreadydecided that the Greek journey is impossible, hence the PSI. Even if borrowing costsare subsidized to ensure that they align with nominal growth, Ireland will only meetthe debt rule if it moves its primary position from last year’s deficit of 6% of GDP to

5

10

15

20

25

91 96 01 06 11

%

Spain

Germany

Unemployment in Germany and Spain

9

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Mai (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchGlobal IssuesFebruary 1, 2012

a primary surplus of 3.6%, and Portugal will only meet the debt rule if it moves itsprimary position from last year’s deficit of 3% of GDP (excluding one offs) to a sur-plus of 3.4% of GDP. And, of course, for those sovereigns in the liquidity hospital,there is an ongoing substitution of official loans for market debt and repaying thoseofficial loans would require large primary surpluses to be run for the indefinite fu-ture.

Given how sensitive debt dynamics are to shortfalls in nominal growth and slippagein primary positions, it is far from clear that debt dynamics around the periphery willbe stable. Given the uncertainty about the magnitude of fiscal multipliers, the impactof bank deleveraging and underlying growth potential, and the lack of a locally setmonetary stance and exchange rate, it is certainly possible that the adjustment pathfor some of the peripheral countries is dynamically unstable, as indeed it has turnedout to be for Greece. If this is the case, then it will not be possible for some of thecountries in the periphery to meet the debt rule.

The attempt to move to a low debt equilibrium will have important consequencesfor area-wide macro performance. Even though our central macro view for the Euroarea this year is for a relatively mild contraction, in terms of the peak to trough de-cline in the level of GDP, in a broader sense we have entered a protracted period ofeconomic weakness. In our current forecast, the peak to trough move in the level ofGDP in the region as a whole is less than in the deep recessions of the mid-70s andearly 90s. But, if we look at the evolution of the level of GDP from just before the re-cession starts to two years after it starts, the current environment is expected to besignificantly weaker than in those earlier periods. This sense of a protracted periodof weakness will also be evident in the evolution of unemployment. With the currentrecession coming so quickly after the deep downturn in 2008-09, the area-wide unem-ployment rate is set to rise to a new post war high of 11%, and will likely remainclose to or above that level for an extended period.

But, even more important than the area-wide macro performance will be the distribu-tion across the region. In the peripheral countries, sovereign, bank, and householddeleveraging will weigh heavily on macro performance, both in absolute terms andrelative to the core. The mild regional recession that we anticipate for this year in the

0

10

20

30

40

50

83 88 93 98 03 08 13

%

Spanish unemployment rate

Total

Youth

10

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Barr (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchThe Euro area’s painful path to EurobondsFebruary 1, 2012

The stability of Euro area debt dynamicsDebt dynamics are very sensitive to macro and fiscal performance. Our central sce-nario for France sees the sovereign bringing its primary position from a deficit ofaround 3% of GDP currently to a surplus of 1% in 2015. Growth is weak in the nearterm but accelerates to a trend-like pace (assumed to be 1.6% in real terms and 3.6%in nominal terms) in the medium term. Under this scenario, debt-to-GDP peaks at94% in 2014 and declines gradually thereafter. Our central scenario for Italy assumesthat the sovereign lifts its primary position from a surplus of less than 1% of GDPcurrently to 5% in 2014. We estimate that the front-loaded fiscal effort pushes Italyinto recession during 2012 and part of 2013, and that growth then accelerates, ap-proaching a weak trend-like pace in the medium term (0.8% in real terms and 2.8% innominal terms). Under this central scenario, debt-to-GDP peaks at 126% in 2013 anddeclines gradually thereafter. These central scenarios are vulnerable to shocks. Toillustrate this, we create alternative scenarios in which the primary balance is 1% ofGDP lower than in the central outcome permanently, and where nominal growth is1%-pt oya lower on average over the next decade. As the charts below show, theseshocks are enough to derail the achievement of sustainability.

75

80

85

90

95

100

105

110

09 11 13 15 17 19 21

% (shock is 1% permanent miss on the prim. bal. and 1%-pt slow er nominal grow th)

French government debt to GDP

Baseline

Shock

110

115

120

125

130

135

140

09 11 13 15 17 19 21

% (shock is 1% permanent miss on the prim. bal. and 1%-pt slower nominal growth)

Italian government debt to GDP

Baseline

Shock

11

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Mai (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchGlobal IssuesFebruary 1, 2012

Euro area is very unevenly distributed, with only one quarter of contraction in Ger-many and deep contractions in Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece. Given the magni-tude of the deleveraging that is needed across the periphery, contractions in the realeconomy are likely to persist into next year and possibly beyond. One way of illus-trating the magnitude of the economic weakness around the periphery is to look atwhere we expect the level of GDP to be at the end of 2013—the end of our forecasthorizon—relative to the start of 2008, just prior to the beginning of the 2008-09 re-cession. For Germany, we expect the level of GDP at the end of 2013 to be almost 3%higher than at the start of 2008, while for France we expect it to be broadly un-changed. Meanwhile, in Spain we expect the level of GDP at the end of 2013 to bealmost 6% lower than at the start of 2008, while in Italy we expect it to be around 7%lower, in Portugal we expect it to be almost 9% lower, and in Greece we expect it tobe around 20% lower. In some of the peripheral countries, unemployment has al-ready reached depression-like levels, and it will move significantly higher. In Spain,for example, the overall unemployment rate is likely to reach 30%, with youth unem-ployment approaching 60%.

Achieving a low debt equilibrium is not just about reducing debt levels. It is alsoabout designing a governance framework that keeps debt down. Regardless of thefact that the Germans failed to fully achieve their governance objectives at the De-cember summit, we do not think it is possible for the Euro area to mimic the USstate-level system, for a number of reasons. First, Euro area policymakers arehighly conflicted about the role of debt restructuring: after the Greek PSI, it is un-clear how it will be applied elsewhere. Policymakers say that Greece is unique butthey will continue to include collective actions clauses in new debt contracts. Thiscontrasts with the clear and credible no federal bail out feature of the US system.Second, the Euro area is still trying to apply financial sanctions rather than recog-nizing the need for political sanctions. Financial sanctions are not very credible attimes of fiscal stress. Third, there has been no discussion at all of introducing fiscaltransfers as an offset to tighter constraints at the national level. Indeed, in recogni-tion of this, the fiscal rules in the Euro area will be set in terms of structural deficitsrather than actual deficits. On the one hand, this will allow some cyclical cushioning.But, on the other hand, it will open the system up to manipulation since the state ofthe business cycle is a matter of judgement.

75

80

85

90

95

100

105

08 09 10 11 12 13 14

Index 1Q08=100

Level of Real GDP

Germany

France

Greece

Portugal

Italy

Spain

12

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Barr (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchThe Euro area’s painful path to EurobondsFebruary 1, 2012

A change in direction to EurobondsThe magnitude of the economic, political, and social stress caused by the hugedeleveraging in the periphery, and the difficulty in designing effective rules, sug-gests that the region will not be able to complete the journey to a low debt equilib-rium. At some point policymakers will decide that a shift to Eurobonds is prefer-able. By removing credit risk from sovereign debt, a shift to Eurobonds would limitthe extent of the sovereign deleveraging that is needed. Essentially, without creditrisk it would be possible to finance a higher level of sovereign leverage in privatecapital markets. It is important to stress that a move to Eurobonds would require asignificant loss of fiscal sovereignty at the national level.

It is important to stress that a move to Eurobonds would not solve all of the region’sproblems. Joint and severally guaranteed sovereign debt does not reduce theamount of deleveraging that banks need to do. That is motivated by the need to re-duce excessive reliance on wholesale funding, in an environment of more explicitprivate sector bail-ins. Nor does a move to Eurobonds remove the need for a correc-tion of intra regional imbalances. The peripheral economies that are still runninglarge current account deficits need to see lower demand and lower prices relative tothe core countries. Eurobonds don’t change this economic reality. Current accountimbalances in the region are currently being financed through the Target 2 system,where the Bundesbank has lent the peripheral central banks around €500 billion tocompensate for the outflow of private capital. The Target 2 imbalance could becomelarger and could persist for an extended period. This means that there is time for thereal adjustment to take place. The only thing that would mitigate the cost of that ad-justment in the periphery would be stronger demand growth and higher inflation inthe core.

There are many different ways that Eurobonds can be structured. We assume thatthey would involve joint and several liability for sovereign debt. One key issue iswhether this joint and several liability would apply to the existing stock of debtonly, and any future debt issuance by sovereigns would still contain sovereigncredit risk, or whether joint and several liability would apply to both the existingstock of debt and to any new debt that is issued.

If joint and several liability is only applied to the existing debt and governments arefree to issue new debt with credit risk, then sovereign borrowing will still need to becontrolled, by some combination of rules and market pressure. The US in 1790 couldbe viewed as an example of this approach: the federal government assumed the statedebts that had arisen in the war of independence, but states were still free to borrowon their own liability. In the US system, state borrowing was eventually controlledafter 1840 through balanced budget rules.

Options for Euro area fiscal governance

Yes No

Yes Australia after 1927

No US in 1790 Current path of Euro area

Socialization of

ongoing

issuance

Socialization of outstanding stock

13

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Mai (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchGlobal IssuesFebruary 1, 2012

But, as we have argued for US states, rules will only work if they are part of a cred-ible system that has several self reinforcing features. In particular, for rules and mar-kets to provide effective discipline, there needs to be a credible no bailout threatfrom the federal level. And political sanctions are likely to be far more effectivethan financial ones. Another problem with this approach is that governments mayfind it difficult to issue debt in a cyclical downturn or a financial crisis becausecredit risk increases at such times.

It might be better for the Euro area to follow the example of Australia, which in the 1927financial agreement set up joint and several liability for both existing state debt andnew state borrowing. Access to credit by the states was controlled by a centralizedloan council. In the Euro area, such an approach could also be used to develop a sys-tem of fiscal transfers. Allocations from a centralized debt management agency couldbe used to compensate for either cyclical or structural divergences.

The Australian model of centralized access to creditAn interesting example of a shift to joint and several liability for both existing debtand new debt is the Australian financial agreement of 1927. This involved a consti-tutional amendment which dramatically changed the financial relationship betweenthe commonwealth (the federal level of government) and the states, with the lattergiving up their sovereignty regarding access to credit.

This shift in the financial relationship across different levels of government did notarise from an acute fiscal crisis. Rather, it came from a more chronic problemcaused by the loss of state level tariff income when the commonwealth was created.Essentially, a single market was formed which meant that all intra regional customsand excise duties were eliminated and there was a uniform tariff between Australiaand the rest of the world, the revenue from which went to the commonwealth.

The commonwealth and state level governments spent a considerable period of timetrying to negotiate a solution to this problem, which culminated in the 1927 agree-ment. This agreement involved the commonwealth assuming liability for all exist-ing state debt (which amounted to around 88% of GDP), the creation of a sinkingfund to provide for the redemption of the debt, and the creation of a loan council tomanage new borrowing for both the commonwealth and the states. Importantly, thisconstitutional change was overwhelmingly supported in a referendum of the Aus-tralian people, which reflected a desire for a cooperative federalism in the new na-tion, a concern about high levels of public debt, and a desire for a reasonable de-gree of equality across states.

Thus, in addition to the transfer of existing state debt to the commonwealth, the1927 agreement involved states giving up independent control of their borrowing.The creation of the loan council was largely motivated by a desire to achieve lowerborrowing costs, but it was also clearly a way of managing overall fiscal policy.There was a recognition that significant levels of commonwealth and state borrow-ing could push up borrowing costs, and was open to criticism in London, the keyfinancial center at the time.

The loan council took over responsibility for the issuance and allocation of common-wealth and state level debt. The liability for new debt was taken by the commonwealth.The loan council would decide how much debt was to be issued overall and how the

14

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Barr (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchThe Euro area’s painful path to EurobondsFebruary 1, 2012

money would then be allocated across the commonwealth and the states. Essentially,the loan council sought to control the aggregate fiscal stance of the states, but did notseek to exercise any control over individual items of expenditure. It was run by repre-sentatives of the commonwealth and the states, with the former having a greater de-gree of power. The commonwealth representative had two votes and a casting vote,while the representatives of the six states each had one vote.

The operation of the financial agreement changed dramatically shortly after its in-ception, with the onset of the Great Depression (which increased the role of fiscalpolicy in demand management), the extension of loan council control to semi-gov-ernmental agencies and local authorities in the 1930s (to close an important loop-hole in the original agreement), and with the development of the uniform incometax in 1942 (which transferred the power to impose income tax from the states tothe commonwealth and thereby required an increase in transfers from the common-wealth to the states). Nevertheless, despite the significant modifications, the loancouncil provided an effective constraint on state level borrowing for several de-cades. Although the loan council still exists today and continues to monitor statefinances, it no longer controls access to credit by the states. States now issue debtunder their own name, with an expectation that financial markets will provide ap-propriate discipline.

Also a shift toward fiscal transfers?Intra regional macro divergences are likely to become much wider over the comingyears, from an already extreme position currently. This is likely to lead to intensepressure for fiscal transfers.

In general, fiscal transfers are thought to be helpful in a monetary and fiscal union,to compensate for the loss of fiscal and monetary autonomy at the local level andthe absence of an adjustment mechanism through the nominal exchange rate. In-deed, many argue that if the region moves to Eurobonds, then fiscal transfers arethe appropriate quid pro quo for the loss of fiscal sovereignty at the national level.Fiscal transfers across the region could seek to mitigate the impact of temporaryshocks, to allow the adjustment to structural shocks to be spread out over a longerperiod of time, or to reduce disparities in either income or the provision of publicservices. They could occur either through a common tax and welfare system, orthrough explicit grants.

At the moment, it is hard to see how a system of fiscal transfers will develop, giventhe small size of the central EU budget, the lack of a common tax and welfare sys-tem, and the political opposition in the core countries to grants. In fact, a lack offiscal solidarity is also evident at the national level as richer regions resent subsidiz-ing poorer regions (for example, the Catalonian government in Spain wants more fis-cal autonomy and a reduction in the amount it transfers to other Spanish regions).

Over time it will be possible to increase the size of the EU budget, which would raise thelevel of regional and structural grants, and in the medium term there may well be someharmonization and centralization of tax and welfare systems. But, such developments willlikely take a long time. In the near term, the easiest way to develop a mechanism for fiscaltransfers would be through a centralized debt management agency. A centralized debtmanagement agency in the Euro area could allocate credit across countries, with adjust-ments made on the basis of local cyclical and structural needs.

15

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Mai (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchGlobal IssuesFebruary 1, 2012

ReferencesR. S. Gilbert, The Australian Loan Council in federal fiscal adjustments, 1890-1965, Australian National University Press, 1973.

B. S. Grewal, “Australian Loan Council: Arrangements and Experience with Bail-outs,” Inter-American Development Bank, 2000.

H. Ergas, “Europe could also learn from Australia’s fiscal federalism,” Letters, Fi-nancial Times, December 28, 2011.

J. M. Poterba, “State Responses to Fiscal Crises: The Effects of Budgetary Institu-tions and Politics,” NBER, WP 4375, May 1993.

W. B. English, “Understanding the Costs of Sovereign Default: American StateDebts in the 1840s,” American Economic Review, March 1996.

M. Bordo, A. Markiewicz, and L. Jonung, “A Fiscal Union for the Euro: Some Les-sons from History,” NBER, WP 17380, September 2011.

How could all this work for the Euro area?The first decision an area-wide debt management agency would need to make isabout the aggregate fiscal stance for the region as a whole, and thus the aggregateamount of debt to be issued. This could be determined by the need to manage de-mand—along with the monetary stance set by the ECB—and the desire to maintaina sustainable overall level of sovereign debt. A first pass on the country allocationscould be on the basis of GDP or GDP per capita. Country allocations could then beadjusted for local cyclical or structural needs, as already occurs on the structuralside with the EU budget. Further adjustments to country allocations could be madeto ensure that fiscal reforms take place. For example, if a country needs to reducetax evasion or improve the efficiency of public services, its allocation of creditcould be reduced.

A centralized debt management agency could also be used to provide incentives forstructural change by adjusting borrowing costs. Although the Australian loan coun-cil set a common borrowing cost across the Australian states, there is no reasonwhy a centralized debt management agency has to do that. Borrowing costs couldreflect adherence to mutually agreed structural objectives, with lower costs easingthe burden of structural adjustment.

The Australian experience suggests that the system should not allow any wiggleroom, in order to reduce the likelihood that governments try to run a looser stancethan is appropriate. This means that the centralized debt management agencyshould cover all debt issuance, including treasury bills and bank borrowing, andshould take account of off-balance sheet transactions and contingent liabilities.

Developing a system of fiscal transfers is likely to be very challenging given the cur-rent degree of political integration in the region. It is worth noting that in the US,state level balanced budget rules were developed from the 1840s, but the currentsystem of fiscal transfers did not develop until the 20th century. We doubt that theEuro area will be able to wait as long.

16

JPMorgan Chase Bank, LondonDavid Mackie (44-20) [email protected] Barr (44-20) [email protected]

Economic ResearchThe Euro area’s painful path to EurobondsFebruary 1, 2012

Recent J.P. Morgan Global Issues

Global economic outlook 2012: let’s get cyclical, Bruce Kasman, David Hensley, Joe Lupton, Jan 2012

Japan well on its way to becoming a capital importer, Masaaki Kanno, January 2012

Nowhere to hide: EM decelerating alongside US and Euro area, Joseph Lupton, David Hensley, Luis

Oganes October 2011

Wagging the dog: powerful swings in EM inflation spill over to DM, J. Lupton, D. Hensley, July 2011

Global repercussions from the Japanese earthquake, Joseph Lupton, David Hensley, March 2011

A way out of the EMU fiscal crisis, Joseph Lupton, David Mackie, December 2010

Stuck in a low inflation rut, Joseph Lupton, David Hensley, October 2010

Government debt sustainability in the age of fiscal activism, Joseph Lupton, David Hensley, June 2010

Central bank exits and FX performance, Joseph Lupton, Gabriel De Kock, December 2009.

JGB challenge: exploding public debt amid falling domestic saving, Masaaki Kanno, Masamichi Adachi,

Reiko Tokukatsu, Hitomi Kimura, October 2009.

Manufacturing bounce to launch global recovery, David Hensley, Joseph Lupton, July 2009.

Slack attack: low utilization rates, disinflation, global policy response, Joseph Lupton, David Hensley,

May 2009.

Bouncing toward malaise: a roadmap for the coming US expansion, Bruce Kasman, Michael Feroli,

Robert Mellman, Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou, May 2009.

EM inflation: trouble beyond the headlines, David Hensley, Joseph Lupton, Luis Oganes, July, 2008.

Credit and growth: the case for the Euro area, David Mackie, Greg Fuzesi, Silvia Pepino, Nicola Mai, and

Malcolm Barr, June 2008.

Sovereign Wealth Funds: a bottom-up primer, David Fernandez and Bernhard Eschweiler, May 2008.

Profit margins to fall, Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou and Joseph Lupton, April 2008.

How will the crisis change markets? Jan Loeys and Margaret Cannella, April 2008.

The odd decouple, Joseph Lupton and David Hensley, December 2007.

So much depends upon a grand experiment, Bruce Kasman, Jan Loeys, David Hensley, Joseph Lupton

and Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou, July 2007.

Longevity: a market in the making, Jan Loeys, Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou, and Ruy Ribeiro, July 2007.

Analysts’ Compensation: The research analysts responsible for the preparation of this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including the quality and accuracy of research, client feedback,competitive factors and overall firm revenues. The firm’s overall revenues include revenues from its investment banking and fixed income business units. Principal Trading: JPMorgan and/or its affiliatesnormally make a market and trade as principal in fixed income securities discussed in this report. Legal Entities: J.P. Morgan is the global brand name for J.P. Morgan Securities LLC (JPMS) and its non-USaffiliates worldwide. J.P. Morgan Cazenove is a brand name for equity research produced by J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd.; J.P. Morgan Equities Limited; JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., Dubai Branch; and J.P. MorganBank International LLC. J.P.Morgan Securities Inc. is a member of NYSE and SIPC. JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. is a member of FDIC and is authorized and regulated in the UK by the Financial Services Authority.J.P. Morgan Futures Inc., is a member of the NFA. J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. (JPMSL) is a member of the London Stock Exchange and is authorized and regulated by the Financial Services Authority. J.P. MorganEquities Limited is a member of the Johannesburg Securities Exchange and is regulated by the FSB. J.P. Morgan Securities (Asia Pacific) Limited (CE number AAJ321) is regulated by the Hong Kong MonetaryAuthority. JPMorgan Chase Bank, Singapore branch is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. J.P. Morgan Securities Asia Private Limited is regulated by the MAS and the Financial Services Agencyin Japan. J.P. Morgan Australia Limited (ABN 52 002 888 011/AFS Licence No: 238188) is regulated by ASIC and J.P. Morgan Securities Australia Limited (JPMSAL) (ABN 61 003 245 234/AFS Licence No:238066) is a Market Participant with the ASX and regulated by ASIC.. J.P.Morgan Saudi Arabia Ltd. is authorized by the Capital Market Authority of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (CMA), licence number 35-07079. General: Information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but JPMorgan does not warrant its completeness or accuracy except with respect to disclosures relative to JPMS and/or itsaffiliates and the analyst’s involvement with the issuer. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgment at the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not indicative offuture results. The investments and strategies discussed may not be suitable for all investors; if you have any doubts you should consult your investment advisor. The investments discussed may fluctuate in priceor value. Changes in rates of exchange may have an adverse effect on the value of investments. This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. JPMorganand/or its affiliates and employees may act as placement agent, advisor or lender with respect to securities or issuers referenced in this report.. Clients should contact analysts at and execute transactions through aJPMorgan entity in their home jurisdiction unless governing law permits otherwise. This report should not be distributed to others or replicated in any form without prior consent of JPMorgan. U.K. and EuropeanEconomic Ar ea (EEA): Investment research issued by JPMSL has been prepared in accordance with JPMSL’s Policies for Managing Conflicts of Interest in Connection with Investment Research. This report hasbeen issued in the U.K. only to persons of a kind described in Article 19 (5), 38, 47 and 49 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2001 (all such persons being referred to as“relevant persons”). This document must not be acted on or relied on by persons who are not relevant. Any investment or investment activity to which this document relates is only available to relevant persons andwill be engaged in only with these persons. In other EEA countries, the report has been issued to persons regarded as professional investors (or equivalent) in their home jurisdiction. Australia: This material isissued and distributed by JPMSAL in Australia to “wholesale clients” only. JPMSAL does not issue or distribute this material to “retail clients.” The recipient of this material must not distribute it to any third partyor outside Australia without the prior written consent of JPMSAL. For the purposes of this paragraph the terms “wholesale client” and “retail client” have the meanings given to them in section 761G of theCorporations Act 2001. New Zealand: This material is issued and distributed by JPMSAL in New Zealand only to persons whose principal business is the investment of money or who, in the course of and for thepurposes of their business, habitually invest money. JPMSAL does not issue or distribute this material to members of “the public” as determined in accordance with section 3 of the Securities Act 1978. The recipientof this material must not distribute it to any third party or outside New Zealand without the prior written consent of JPMSAL. Canada: The information contained herein is not, and under no circumstances is tobe construed as, a prospectus, an advertisement, a public offering, an offer to sell securities described herein, or solicitation of an offer to buy securities described herein, in Canada or any province or territorythereof. Any offer or sale of the securities described herein in Canada will be made only under an exemption from the requirements to file a prospectus with the relevant Canadian securities regulators and only bya dealer properly registered under applicable securities laws or, alternatively, pursuant to an exemption from the dealer registration requirement in the relevant province or territory of Canada in which such offeror sale is made. The information contained herein is under no circumstances to be construed as investment advice in any province or territory of Canada and is not tailored to the needs of the recipient. To the extentthat the information contained herein references securities of an issuer incorporated, formed or created under the laws of Canada or a province or territory of Canada, any trades in such securities must be conductedthrough a dealer registered in Canada. No securities commission or similar regulatory authority in Canada has reviewed or in any way passed judgment upon these materials, the information contained herein or themerits of the securities described herein, and any representation to the contrary is an offense. Kor ea: This report may have been edited or contributed to from time to time by affiliates of J.P. Morgan Securities (FarEast) Ltd, Seoul branch. Revised January 6, 2012. Copyright 2012 JPMorgan Chase Co. All rights reserved. Additional information available upon request.