Making Your Own Luck – “Planned Happenstance” June Kay Career Development Consultant.

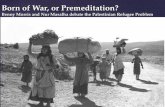

Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and...

-

Upload

german-fernandez-vavrik -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and...

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

1/21

Human Studies t6: 435-454, 1993. 1993 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

Premeditation and happenstance: The social construc-tion of intention, action and knowledge

LENA JAYYUSIDepartment of ommunication Studies, Cedar Crest Co llege, A llentown, PA 18104

Introduction

Two major topics which have enlivened the human sciences in recent yearshave been: the problem of action attribution on the one hand, and the natureof 'mind' and the relationship between psychological constructs and theirsocial contexts on the other. Throughout both concems, the focus on thepragm atics of language use has become central.

The problem of action attribution (or ascription) has been of particularconcem to sociologists and philosophers. One of the most recalcitrant issuesin this domain has been the issue of action individuation. Austin (1973) haselegantly shown that what a person has done can be given a number ofdifferent descriptions, each bringing in 'more or less' of the consequencesof the action into the description itself. The pivotal question here has been:are the descriptions to be treated as just so many different descriptions ofthe 'one' action performed by the actor, or can the actor be said to have

performed as many different actions as there are descriptions. To use theexample given by Austin: When a person pulls the trigger, firing the gun,shooting a donkey and killing it, are these four different actions or simplyfour descriptions of his one action? From the perspective of relativelyrecent developments in sociology, namely ethnomethodology, for which thestudy of social action has been the primary analytical focus, this philosophi-cal debate has been fundamentally miscast. The issue of what actions areattributed to whom, how actions are to be described and what features ofthem are significant for their description, assessment or ascription is settledby members (or left unresolved) in the actual contexts of ongoing socialinteraction. All these matters are grounded in the network of conventions

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

2/21

436

constructs and social contexts, has been an abiding concem for psychology,philosophy, and of late, for sociology as well. In philosophy, LudwigWittgenstein (1968), and later philosophers working within his tradition(see, for example, Malcolm, 1968; Hunter, 1973; and Hacker 1986) haverelocated the problems of subjectivity and cognition from the domain of aprivate, individual's world, filled with putatively private mental acts andessentially inaccessible 'subjective states' to a public world of conventionand intersubjective criteria for the avowal, attribution and ratification/defeatof mental and psychological predicates. Psychological phenomena have, inthis way, been transformed into social phenomena, and it has become clearthat their understanding has to be grounded in the systematic analysis of the

practial contexts of ascription and avowal. Such a program has notably beenformulated and developed in the work of Jeff Coulter (1973, 1979, 1983,1989). There has recently also been a growing 'social constructionist'approach within the ranks of social psychologists (see, for example,Gergen, 1985; and Harre, 1986), albeit most ofthe work remains couchedin theoretic rather than analytic terms.

This paper will attempt to look at a class of cases where both of theseconcems are conjoint features of practical contexts of attribution and

accounting. If the ascription of mental predications (knowledge; belief;intention) are matters of practical assessment and constmction in-situ, and ifthe ascription of actions and the use of action descriptions are also mattersof assessment in-situ, then in what ways are the two kinds of practicesbound up? I propose to explore features of the logic of action descriptionand attribution in contexts where 'knowledge' and 'intention' are them-selves matters to be assessed and ascribed, and to reveal the reflexive logicsof action/intention/knowledge attributions. In the process I will hope toshow how the philosophical problem of action individuation find itsresolution in the analysis of m emb ers' in-situ practices of action descriptionand action attribution, and that the different kinds o/action description andaction attribution, and the different sorts of narrative trajectories they makepossible, can provide for the accomplishm ent of systematically differentinteractional tasks. In other words, they have a different logic-in-use, adifferent socio-logic. It is this socio-logic that is the focus of this paper.

Let me then start with one of the ways that the problem of action attributionhas been cast in the philosophical literature: namely the issue of actionindividuation. Philosophers have generally given two answers to this

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

3/21

43 7

the same action, each description incorporating more or less of the conse-quences of the action. Without discussing the philosophical arguments indetail, I suggest that Austin's formulation comes closest to treating the

problem of action as a problem of communicative practice (very much inkeeping with the thrust of Austin's work in general). Yet, one would wantto go further than him and say that those four different descriptions of theone action are four different kinds of description, something that can tumout to be of practical import for members in the oiganization of variousaccounts of their own and others' actions, and in the conduct of social life.Austin (1973: 106-107) wrote, and I quote:

There is no restriction to the minimum physical act at all. That we canimport an indefinitely long stretch of what might also be called the'consequences' of our act into the act itself is, or should be, a fundamen-tal commonplace of the theory of our language about all 'action' ingeneral. Thus if asked 'what did he do?', we may reply either 'He shotthe donkey' or 'He fired a gun' or 'He pulled the trigger' or 'He movedhis trigger finger', and all may be correct.

Indeed yes, they might all be formally correct. But they are not interchan-geably meaningful, relevant or appropriate in any practical context. To

answer 'He moved his trigger finger' when asked 'what did he do?' mightbe appropriate where a routine circus trick resulted in some injury, butabsurd where a man is being led into the defendant's stand in court forindictment on a murder charge. A response such as "He shot his partner" isthe kind of description we might expect to get in such a context. And if,instead, we were to be given the answer: "He fired his gun at his partner"we could legitimately assume that the man was up for indictment not on amurder charge but on attempted murder charges. In other words, thesedescriptions are intelligible in different kinds of practical contexts ofaccounting, description or ascription, and they are used to accomplishdifferent accounting and interactional tasks. If we look at them systemati-cally, we can see that this is because they m ake available different featuresof the context of the presumed action. Let us compare Austin's examplewith a range of similar ones:

Examples I-V

A B C D E

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

4/21

438

II .

III.

IV .

V.

Pressedthe button

Pressed hisfinger overthe syringe

Put thelighted matchto theexplosives

He put hisfinger intothe hole

fired amissile

emptied thecontents ofthe syringeinto herbloodstream

ignited theexplosives

plugged thehole in thedyke (withhis finger)

hit theplane

injected herwith thepoison

blew thehouse up

kept thedyke frombreaking

blew a holein thefuselage

poisonedher

blew themup

kept thewater fromfloodingthe valley

downedthe plane

killedher

killedthem

savedtbetown

If we look at the initial item in each example we can see that the descriptiongiven is one that renders the mechanism of the action, and is in terms of it.It does not, however, make the consequences or outcome of the actiondescribed available, yet it holds within it, embedded in the specific descrip-tion, a set of possible trajectories that can logically unfold from the action-as-described, and from which a further action description can be intelligiblymade or selected, one that articulates within it yet more of the conse-quences. It points prospectively to an unfolding course of events that maybe said to be logically or practically endogenous to the action-as-described.

At the other end the final item provides an 'outcome' but no mechanismby which that outcome was accomplished. (Except for example II 'downed

the plane' where the range of possible mechanisms is delimited.) It is anitem that points retrospectively to a trajectory of acts and events that mayhave led up to this 'outcome'. But how the donkey was killed, the planedowned, the town saved is not given us in this description. If we look at thewhole range of items in each example it will become evident that no singleitem renders entirely transparent both mechanism by which the action-as-described came about or was performed, and the ultimate outcome of thataction-as-described that can be treated as logically or pragmaticallyendogenous to it in a given context. Of course, no category, no descriptioncan render transparent all contextual features, in itself. This is commonplace However the point more specifically is that:

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

5/21

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

6/21

44

pistol' and 'fired' are two items that hearably and conventionally gotogether in tandem, as a first action and relevant next. But, as an agent-centered, temporally organized scenic description 'he pointed a pistol' atthe proprietor and 'fired' is a description that can accept the insertion ofanother course of actions and/or events within it, where the sequel, orrelevant next to the first item ('pointed'), is held in temporary abeyance. Inthis case we have, inserted between the first item ('he pointed a pistol...')and the sequel ('just fired'), the narrative sequence: "the women pleadedwith Stewart to 'take the money' and offered him the register. He, however,'didn't step back, he didn't step forward, he didn't change expression.'" Itis made clear that the women's pleas had no uptake whatever. Given the

women's pleas, and their object, any next action by the agent can getconstituted in terms of a morally-implicative response or uptake. Here, nouptake whatsoever by the man pointing the pistol becomes accountable as aspecific sort of response. This response is rendered in terms of an 'absence''he didn't step back, he didn't step forward, he didn't change expression.'Note here that this is thus scenically rendered over the course of threeitems, maintaining the sense of temporality by putting off the expectablenext item, the sequel that is itself productive of the relevant ultimateoutcome (the death of the proprietor). And like the 'just fired' that im-mediately follows them, these items are agent-centered. This way oforganizing the account, and this co-selection of items and action descrip-tions, can constitute for them, and for their agent, a specific moral profile.Both in terms of its content and its organization, this account projects theagent's actions as having been deliberate and unemotional - in other wordscold-blooded.

In fact, this particular account is given as part of a chapter (Arens, 1969:27-73) concemed with discussing the diagnosis of mental disorder bypsychiatrists in criminal trials. The deliberate, unemotional character of theagents' actions, provided for by the description, constitutes the outcome ahaving been fully intended, and the agent as having been cognizant of hisactions. Paradoxically, however, it is precisely this that provides possiblegrounds for the ascription of 'mental disorder' (whereby the agent is insome way deemed not properly cognizant of his action and its outcome)Given the other particulars made available within this account: namely thathe victim is a stranger to the agent, and that the women were prepared to

give Stewart the cash register before he shot the man, accountably rationagrounds for the action may be seen to be absent, and the deliberate shooting

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

7/21

441

particular kinds of action descriptions can bring this off.Let us explore some further ways that action descriptions can accomplish

different practical tasks. Consider the following

Data segment 2. (Arens, 1969: 208)

The Defense: How did you make out in the Military Service?The Witness: Well, I didn't make out too good.The Defense: What happened to you?The Witness: I become to having headaches in the service and they put me in

the hospital and I stayed there and they discharged me from thehospital.

The Defense: Do you remember what kind of a ward you were in when youwent to that Army hospital?

The Witness: It was a mental ward.The Defense: What did you do upon your discharge Mr.... (Rivers)?The Witness: Well, I came out of the service and I was walking down - about a

week after I was out of the service, I was walking down the streetand a fellow shot out of the door at another fellow and hit mebehind the leg and I went to Casualty Hospital and I lost my legafter that.

The Defense: How did you happen to lose your leg?The Witness: Well, gangrene set in my leg and they had to take it off.

I wish to focus briefly on the description of the shooting incident. Hereagain, we have a temporally unfolding scenic description, one in which twocourses of action intersect. The use of 'shot out at,' like 'fired at,' does notexplicitly render the outcome conventionally embedded in that action, butprovides for its relevance programmatically. The intended target of theshooting is given here as having been 'another fellow.' Thus, the selectionof this kind of action description, one that is 'outcome indeterminate,'permits the rendering (and the reading) of the actual outcome as havingbeen unintended. And the scenic way in which this is done exhibits theintersection of the two activity trajectories, and the outcome thereof, ashaving been totally by chance. The witness could, of course, have providedfor the accidental nature of his injury by saying: "I was walking down thestreet and a fellow shot me behind the leg by accident." But without ascenic description that could answer the potential question 'how,' rather

than simply the question 'what happened,' the possibility of the injuredman's having been in some way directly implicated in the 'accident' mayi At t it i th t t ll h h t f th t

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

8/21

44

distinct 'moral' character to both event and recipient. The injured man, thewitness, can here be seen as totally a 'victim,' and this account thus meshes

in with the story of misfortune that is being collaboratively unfolded andproduced by Witness and Defense over the course of the sequence fromwhich this interchange comes (Arens, 1969: 202-212).

Thus, in both data segments we have looked at, the selection of actiondescriptions is co-fitted with the selection of other details to produce ascenic as-though-witnessed account of 'what happened' and one thatconstitutes for the described actions and events, and the persons involvedan identifiable moral character. And further, this moral character, madeavailable through the specific organization of temporal and scenic par-ticulars, is one which tums on, and is given in, the depiction of an action ashaving been deliberate, and the outcome as coldly intended (what we mightotherwise describe as pre-meditated) in the first example, and of theoutcome as being a matter of happenstance, that is to say, completely bychance rather than intended, in the second example. In fact, 'inten tion ,''deliberation,' 'chance,' 'happenstance,' 'mishap' etc. seem to be criticalparameters for the moral constitution, assessment and description of actionsand events, and feature pervasively and significantly in the conduct of

social life, even if they do not explicitly surface as an issue in each andevery practical setting. Any action can, in principle, be made subject to suchconsiderations in-situ, and can thus be articulated into a second order moralaction description. For instance, such an ordinary act as 'turning on theligh t' can be constituted as 'harassm ent,' 'escalating a quarrel,' or simply'doing something mean' given the appropriate context.

To help focus more closely on this issue let us tum to the work of GilbertRyle. In the Concept of Mind (1973), Ryle distinguishes a class of verbs

which he calls 'achievement' verbs or 'find' verbs (he also variously callsthem 'success' verbs or 'got it' verbs). These he contrasts with what hecalls 'hunt' or 'try' verbs or 'task' verbs (the particular term he uses at anyone po int depends on the analytic point he is trying to m ake). He writes:

One big difference between the logical force of a task verb and that ofthe corresponding achievement verb is that in applying an achievementverb we are asserting that some state of affairs obtains over and abovethat which consists in the performance, if any, of the subservient taskactivity. For a mnner to win, not only must he mn but also his rivalsmust be at the tape later than he; for a doctor to effect a cure, his patientmust both be treated and well again; for the searcher to find the thimble,

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

9/21

443

consequence of this general point that it is always significant, though not,of course, always true, to ascribe a success partly or wholly to luck. Aclock may be repaired by a random jolt and the treasure may be un-earthed by the first spade-thrust.

Ryle goes on to say:

When a person is described as having fought and won, or as havingjourneyed and arrived, he is not being said to have done two things, butto have done one thing with a certain upshot. ... Achievements andfailures are not ... acts, exertions, operations or performances, but withreservations for purely lucky achievements, the fact that certain acts,operations, exertions, or performances have had certain results,(pp.143-144)

If we tum back to our set of examples, I-V, we can pick out a number ofdescriptions which "indicate the fact that certain acts have had certainresults," results that obtain over and above that 'subservient task activity' asRyle puts it: 'killed,' 'downed,' 'saved,' 'poisened,' 'blew up.' I prefer tocall these 'outcome' verbs. The notion of 'achievement' here being used byRyle logically presumes that the result had been sought and intended. Thus

it makes sense in this context to locate 'serendipity' (i.e., purely luckyachievement) as a qualifier, one which, were it to be applied, would besignificant and indeed may undercut the claim to success or achievement,even the claim of an agent to have endeavored towards that end. Butoutcomes are not always sought or intended; at least they are not alwaystreated as matters to be sought - for example: 'killed ,' 'ruined ,' 'destroyed'are bound up conventionally with negative moral judgments, and arepractically productive of negative consequences for the agent, so much sothat the disavowability of 'intention' to achieve these outcomes, or even ofthe endeavor to do so, may be.preferred. A t any rate Ry le's aside on 'purelylucky achievements' ultimately stops short - the issue of intention, luck,chance, deliberation is of programmatic relevance in the organization ofaccounting practices: it is programmatically relevant for the way that'outc om es' and thus actions and their agents, as well as their recipients, canget morally constituted. It is programmatically significant whether an'ou tcom e' can be found to have been endogenous to the course of action-as-project, or exogenous to it. In set I-V consider example 1. Each of the

different kinds of descriptions there can make relevant a somewhat differentset of questions or narrative trajectories: If he moved his trigger finger, was

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

10/21

444

him? And furthermore, did he know that his man was in fact Mr. X, or hadhe killed him believing it was Mr. Y? The point to note here is that all these

questions, and the kinds of accounts that can be spun around them, tum onthe issue of intention and outcome. What outcome was intended in anyaction-as-described, what outcome eventuated, and whether a namedoutcome had actually been intended as such, are all matters which may beroutinely displayed or hearably avoided, presumed or raised in the organiza-tion of an account's particulars, and whichever way that the accountarticulates such a matter may yet leave it open to contest. It is these mattersthat provide for the upgrading or downgrading of ascriptions of respon-sibility, for dramatic discourse on themes of fate and fortune, for complaintsabout professionalism, carelessness and so on. Each of these kinds ofdescriptions can be articulated into a different kind of narrative and interac-tional task.

Furthermore, whether the agent can be constituted as having intended toshoot Mr. X when he pulled the trigger depends on whether we canpresume or ascribe knowledge to him that the gun was loaded. And w hetherhis firing at Mr. X and killing him can be rearticulated as an act of murderor self-defense might depend on whether he believed that Mr. X was

pointing a real weapon at him or knew that it was simply a toy gun. Someyears ago in the Boston area there was a report of a woman who had shother husband dead in the dark of the night thinking he was an intruder, notrealizing that he had, on impulse, decided to throw out the garbage. Anaccount of the husband's demise as a mishap, in other words as an outcomethat had not been intended, would presuppose attributing to her the beliefthat the man she confronted in her home in the dark was a stranger. But ifone were to find grounds for attributing knowledge of the victim's identity

to her, then it would be possible to locate, in that, further grounds forconstruing the outcome as having been fully intended by her, in other wordsfor attributing to her the intention of shooting her husband, and for recastingher action as 'murder.' The point here is that attributions of knowledge andintention are finely intermeshed together in practical settings, and they areboth finely intermeshed with the sorts of action attributions we make andthe tasks that are accomplished by them. For a more detailed look at one ofthe ways that this can work let us now consider the following data segment:

Data segment 3

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

11/21

31323334

353637383 94

P:

S:P:S:P:S:P:S:

445

(White male accused of killing a black male)P - Police Officer, S - Suspect

Well then did you know that you were shooting at ... ordid you shoot at him just because he was colored, period?He's a nigger.And that's why you shot him and er.That's why I shot him.Did you intend to kill him ... or?Yes. . .yer.Do you think I'd fire at somebody if I didn't intend tokill them?

The context of this exchange is known in comm on to the two p articipants; itis the death-by-shooting of a black male, an event to be constituted as anoutcome of some prior action by an agent, in this case the white suspect. InP's question on line 31 he uses the action description "shooting at..." The'shooting at' is of course known by them to have resulted in its an-ticipatable outcome, namely that G was actually shot and killed. P asks Swhether he knew that he was shooting at G or shot at him because of his

race. Either alternative leaves one thing in place: that the shooting at thevictim was not an accidental firing. To describe the 'shooting at' as anaction performed-in-the-knowledge of the victim's identity, or as onelocated in some specifiable reason is hearably to close out the possibility ofmishap. Both logically presuppose that the agent fired at his victim inten-tionally. But refiexively, it is precisely in asking such a question, set up asan alternative between these two choices, that the police officer is hearablypresuming intention and attributing it retrospectively to the suspect. In otherwords, it might not be an issue for the police officer in-situ whether therehad been an accidental firing of the gun - eye witness accounts, hisknowledge of the suspect's prior record, any other number of features couldhave that matter settled for him. But it is in the way the question is con-structed that he is hearably presuming intention, and constituting it as anon-contestable matter, or at least as not a matter to be concerned with. Thechoice given the recipient of the question is between answering to one orthe other, each of which presumes an intentional shooting of a man (thevictim). P's turn, in other words, seems to prefer an answer which supports

and upholds the presumption of intentionality. Thus, the presumption ofintentionality can be said to be 'over-determined' here, since the defeat ofth t ti ld i t i l t th ti (

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

12/21

446

('shooting at'), which already hearably presumes that the action-as-described was an intentional one - that the gun did not fire accidentally, and

that the agent was not simply firing in the air, or trying to do target practiceat some object in the street, etc. Thus, within the attribution environmentprovided in each of the two questions, there is a co-selection of items thatuphold each other's sense such that we have a seamless attribution ofintentionality.

In line 33, S. indicates that race was the reason for his action, thusaccepting and ratifying P's presumption. A transformation of race as areason for shooting at G, to a reason for 'shooting him' is now effected byP. in line 34 - he uses an 'outcome' verb which is performance-related,displaying the mechanism by which the outcome was accomplished, themechanism already given in the performance description used in line 31 , anoutcome-indeterminate description. 'Shooting at' is transformed into'shoo ting.' It is a smooth transformation. And it accomplishes an u pgradingof intentional attribution or presumption. On proposing a reason for why Sshot G, the hearable presumption or attribution being made to S is that of anintention to achieve that outcome. S assents, again ratifying the presump-tion. A further transformation is not made - rather the next step is explicitly

made. 'Kill' is a genuine 'outcome' verb - one that points to a priortrajectory of action that led to it but does not deliver it, and does notnecessarily render whether the outcome had been intended or not. Giventhat indeed there is a man who has been killed, and that the suspect has notdisavowed the presumption that he had intended to shoot (that is to hit) him,can strongly implicate the possibility that he had also intended to kill him,but cannot settle it. P therefore asks 5: "Did you intend to kill him ... or?"(line 36) and 5 answers in the affirmative (line 37). Intention with regardsto 'outcome' here surfaces explicitly as an issue, and 5 then goes on toavow it openly and locate it at the same locus at which this interchangebegan - the point where he shot at, or fired at, the victim (lines 39-40).Thus, in this exchange, we have a gradual widening of the intenfional netthat can thus morally constitute the action-leading-to-that-named-outcomeas a particular kind of action, and upgrade the responsibility attributable tothe agent.

I want now to tum to the last segment of data which I will consider.

Data segment 4

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

13/21

44 7

the plane with a heat-seeking missile and contend that the Soviets must have knownwhat they were shooting at. (italics added)

On 3 September 1983, U.S. newspapers and broadcasts were full of thestory of KAL Flight 007, shot down by Soviet fighter planes over the islandof Sakhalin in the Soviet Union. One of the most striking features of thecoverage of that 'story,' in general terms, was the way that 'what hap-pened,' although not actually known in its particulars, nor directly'witnessed,' was treated and presented as 'known,' as clear and self-evident, not a 'mystery' in any sense. And yet, despite this over-all charac-ter of the news coverage of, and accounting for, the 'event,' an inspection

of the details of the news narratives and their features reveals an organiza-tion of particulars that orients visibly to the fact that the 'full story' was notdefinitively KNOWN. And this organization of particulars was such that itwould prospectively 'undercut' any possible 'disqualifying' items and fill inthe 'ga ps ' so as to point to and uphold the 'story-as-ktiown.'

In other words, there seemed to be (on the face of it) a 'paradox' at workhere. On the hand, although the 'story' was not properly ktiown in all itsdetail, indeed not even in that detail which could have been 'account-

transforming,' the story was presented as known-in-general. On the otherhand, although the story-in-general was presented, and indeed on occasionformulated explicitly as being 'known,' it was clear from the organizationof the account's particulars, and the issues being oriented to, and attendedto , that the 'story' was being addressed as in some ways 'not known.' Thisis a story that is known-in-general but unknown-in-its-particulars, and it issignificant that not all stories have this character. Data segment 4, comesfrom one such account and runs under the headline: Prez to reveal Actionon National T.V.

To begin with, we can gather that a Korean airliner, carrying 269 peopleaboard, is missing. But we are also given a location for the 'onset' of thatmissing status: restricted skies near Soviet military installations. Thus an'event' is provided and given its spatio-temporal boundaries: a civilianairliner 'was lost,' in the words of the report, at a particular time and place.The agent however, if there be one, has not been made available yet. 'Lo st'is an outcome descriptor (whether used as verb or adjective), and does notprovide 'career' or trajectory particulars. Here it is given a passive construc-

tion. Thus here we have the use of an 'outcome' descriptor that does notmake available whether there was any 'culpable' moral agency involved in

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

14/21

448

stupid, reckless) it is so strongly hearable as providing for an unintendedoutcome that, for all practical purposes, it is not heard as an action attribu-tion, and the question of 'intention' to lose is not routinely intelligible.Where there is a doubt raised as to the intentions of the agent, that ishearable as doubting whether the agent actually lost the object at all, or infact, 'hid it,' 'gave it away,' 'threw it away' etc. To cast the outcome 'lost'in the passive then, as this report does, in other words with the agentdeleted, preserves (paradoxically) the possibility of assigning an activity toan agent by which this visible outcome intendedly came about.

A plane fiying at a great height and distance away is not directly acces-sible to our perceptions and apprehension. The setting is not directlywitnessable, as would an event happening down the street, although it hasits own 'witnessable indices' - blips on a radar screen. Given that com-munication has suddenly ceased with this plane, and its life indices havesuddenly vanished, this first description (The Korean airliner ... was lost...etc.) seems to be truest to our 'first knowledge,' a 'tangible knowledge' soto speak. This first description is one that has not yet provided us with any'transparency,' any real access to the event, only a located outcome whichpoints to there having been an event of some kind. However, the outcome

with its presumed antecedent 'event' is given a specific setting: "restrictedskies near Soviet military installations." Such a scene-setting sets up anenvironment of categories that can be generative of possible accounts of theevent for which we now have a visible outcome - and generative of'candidate reasons' as well as a 'candidate trajectory.' Here we have anoutcome with great moral significance (the presumed loss of lives) whichroutinely makes relevant the search for agency and the issue of agency isaddressed in the next line: "U.S. officials say a Soviet pilot shot down theplane." In this construction, the fact that 'what happened' is not concretelyknown is oriented to - the solution given to the problem of the missingplane takes the form of a claim attributable to locatable persons: "U.S.officials say ..." This preserves the force of the prior description "was lost"but provides a candidate solution to the problem or puzzle.

The content of the claim: "A Soviet pilot shot down the plane" can bethought of, and treated as, an attribution conjuncture - it involves theattribution of an action, directed towards some recipient, to an agent. And Iwould like to suggest here in passing that one needs to treat action descrip-tions and action attributions as just such attribution con junctures - it is easyto see that a description such as "the father shot his little boy " is different in

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

15/21

449

as a description to be potentially rearticulated as 'infanticide,' the secondmore easily as 'm isha p.' Now one thing about this conjuncture ( . . . a Sovietpilot shot down the plane) is that it is hearable in an intentional mode -namely that the plane's downing was an outcome endogneous to the pilot'scourse-of-action-as-project. There are probably a lot of convergent reasonswhy this is so, among which one might briefly mention: the active voicewhich conventionally (although not in formal logical terms) constitutes an'outcome' as an action-intendedly-with-that-outcome; the filling of thequalifier slot post action attribution with the provision of an instrument bywhich the action/outcome was accomplished, our routine substantive andcategorial knowledge of the world that might make it difficult to see a

shooting down of a plane as accidental, the categories used to 'set thescen e' for the event, etc.

Yet the point to remember here is that the 'event' of which this claimspeaks, the event which led to the plane's disappearance, is not given as'known' in this account - it had not been ratified as a 'shooting down.' Itcould, therefore, turn out to have been an accidental collision, or routinemilitary maneuvers in which the plane got accidentally mixed up. Thus, theclaim being made is hearably to an 'even t': that the plane was shot down by

a Soviet pilot, and to an action: that the Soviet pilot deliberately shot downthe plane - he had intended to shoot it down and succeeded in doing so. Butof course, either of these two hearable claims could still be defeated, orquestioned. Because the attribution is presented at this point as a claim:"U.S. officials say..." one of the questions that might remain is whetherthere indeed was such an event with those named mechanics and thatoutcome. Or, if one accepts this, one questions that may still remainpractically open is whether the pilot had deliberately shot the plane down.

But the matter does not end here. There is yet a further possible issue thatmay be raised, another potential indeterminacy that may surface - it has todo with whether the identification of the 'recipient' or 'object' of the actionby the reporter and/or reader is identical with its identification by the agentin the performance of his action-as-described. In our data 'the plane' refersto KAL flight 007 with 269 passengers aboard - a civilian airliner. Theattribution "a Soviet pilot shot down the plane" is, in this context, indeter-minate as to whether it is being made in an opaque or transparent context(see Quine, 1960; Jayyusi, 1984: ch. 6): does the reporter mean to say that

the Soviet pilot knew that he was shooting down a civilian airliner Anddid the pilot in fact know that? Or did he perhaps think it was a spy plane,

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

16/21

45

least three significant matters to be ratified and accepted or defeated: thereis first the issue of whether some other occurrence was in fact behind theplane's disappearance. Then, if it is accepted or passed that the plane hadindeed been shot down by a Soviet pilot, there could be the matter ofwhether that had been intentional or not; had the pilot simply been trying towarn the plane to force it to land, etc. And then there is the question as towhether it was this plane, the civilian airliner, that the pilot had intended toshoot down.

The difference between the last two questions (both of which pertain tothe issue of intentionality in practical actions: the first to its ascribability,the second to its scope) can be highlighted by the different uses the con-

cepts of 'accident' and 'mistake' could have here. To adapt one of Austin's(1970: 185) examples on shooting a neigh bour's donkey: Suppose apoliceman was doing target practice in a country field, and someone runsinto the line of fire and gets shot. The policeman can then say: it was an'accident.' He had not had any intention of shooting anyone. On the otherhand, if he had been pursuing a suspect in the road, and thinking he had himcovered at last, aimed at and shot him, only to find out that it was someoneelse, then he would be said to have shot that man 'by mistake.' He had hadthe full intention of shooting a man, but not this one. The terms of moralreprobation and assessment that could be made relevant in each case wouldbe significantly different. Moreover, the applicability of the notion of'mistak e' here presupposes that the notion of 'accid ent' does NOT apply.

In other words there is an order and an orderliness to the possibility oforienting to, raising or settling issues around these different pivots ofcontestability or kinds of potential indeterminacy - we can see that, both inthis data, as well as in the police interrogation discussed earlier (Datasegment 3). They cannot both, or all, be made meaningfully operative atonce. In our present example, the three matters that we have noted as beingpotentially open to contest, particularly given the guarded character of theclaim, have a certain order in relationship to each other - the order of issueor contest must needs move logically in a particular way. How such anorder is made to work in the management of prospective 'hearings,'problems and questions, and what sort of accounting task it can be put to, isevident in the last line of this news report which reads: 'and contend thatthe Soviets must have known what they were shooting at.' Here we have it:

the assertion, following the guarded claim, that the 'Soviets must haveknown what they were shooting at' deftly accomplishes a number of things

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

17/21

451

making this the pivot of contestability, the account now presupposes and inthe same breath projects that the outcome was brought about intentionally:that there was a deliberate shooting down - no accident. The attribution ofintention is both indexed and accomplished at the same time. It is made inmaking the attribution of knowledge to the agent. And now, we come backfull circle to the point initially made about this 'story': that it is treated inthe account as a story that is known-in-general, but unknown-in-its-par-ticulars. Indeed we can here see the working of a 'social construction ofknowledge' in-situ. In the same breath that the intentional attribution isindexed and accomplished, the 'event' as a whole, as constructed in theattribution conjuncture is presupposed as 'given', and as having occurred-

as-described. The attribution conjuncture is now given and hearable as areal-world description, an 'actuality account' despite the guarded characterof the account. It is in this way that the account visibly orients to the hiddenseams within it (precisely the points at which alternative or oppositionalaccounts and items can be inserted, and round which queries and challengescan be generated), and manages them, elaborating itself as a seamlessaccount. Thus, the construction of the event as 'known,' despite possiblecontests and indeterminacies, is possible through the economically andfinely located and organized use of a 'laminated attribution order.'

Conclusion

Ih av e attempted to show that the philosophical problem of action individua-tion finds its resolution in the analysis of members' in-situ practices ofaction description and action attribution, and that the different kinds ofdescription that may be given of any one presumed action make availabledifferent features of that action, and thus are loci for the production ofdifferent sorts of narrative trajectories. They can thus provide for theaccomplishment of systematically different kinds of interactional tasks. Forthe present purposes I have distinguished two kinds of constructions thatcan be provided of 'actions': those that are 'outcome' descriptions (andinvolve the use of outcome verbs) and are indeterminate as to prior trajec-tory or intention; and 'outcome-indeterminate' performance descriptionsthat nevertheless can point to a prospective trajectory of possible outcomes

but do not deliver them. These two kinds of description have a differentlogic-in-use, a different socio-logic, and it is this socio-logic that I have

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

18/21

45

ascription, invocation or inference of intention will presuppose or impli-cate a particular action description. Put another way, particular actionattdbutions or descriptions logically provide for, or presuppose (are

logically tied to), specific kinds of attribution of intention and knowledge. Indeed, the grammar of action accounts is a logical grammarof intention, knowledge and outcome . What action attribution ordescription is given or used in any particular context then, depends on andprojects a particular composite or conjuncture of these three actionparamaters. It is in this sense that one can talk of a socio-logic of action or,looked at in another way, a socio-logic of knowledge-in-context, one that issimultaneously conceptual, normative and practical.

eferen es

Arens, R. (1969). Make mad the guilty. Spdngfield, IL: Chades C. ThomasPublisher.

Austin, J.L. (1970). A plea for excuses. In Philosophical Papers. Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press.

Austin, J.L. (1973). How to do things with words. New York: Oxford University

Press.Coulter, J. (1973). Approaches to insanity: A philosophical and sociological study.London: Martin Robertson.

Coulter, J. (1979). The social construction of mind. London: Macmillan.Coulter, J. (1983). Rethinking cognitive theory. London: Macmillan; New York: St.

Martin's Press.Coulter, J. (1989). M ind in action. Oxford: Polity Press.Gergen, K. (1985). The social constructionist movement in modern psychology.

American Psychologist 40: 266-275.Goldman, Alvin I. (1971). The individuation of action. Journal of P hilosophy 68:

761-774.Hacker, P.M.S. (1986). Insight and illusion: Themes in the philosophy of Wit-tgenstein. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harre, R. (1986). Social sources of mental content and order. In J. Margolis, P.Manicas, R. Harre and P. Secord (Eds.), P sychology: D esigning the discipline.Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Jayyusi, L. (1984). Categorization and the moral order. Henley, UK: Routledgeand Kegan Paul.

Malcolm, Norman (1968). Knowledge of other minds. In G. Pitcher (Ed.),Wittgenstein: The philosophical investigations. London: M acmillan.

Quine, W.V. (1960). Word and object. New York: Wiley.Ryle, G. (1973). The concept of mind. Harmondsworth: Penguin University Books.

( ) h l h l b

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

19/21

Appendix

Examples I-V

453

B D

III.

IV .

V.

Moved histrigger finger

Pressedthe button

Pressed hisfinger overthe syringe

Put thelighted matchto theexplosives

He put hisfinger intothe hole

pulled thetrigger

fired amissile

emptied thecontents ofthe syringeinto herbloodstream

ignited theexplosives

plugged thehole in thedyke (withhis finger)

fired thegun

hit theplane

injected herwith thepoison

blew thehouse up

kept thedyke frombreaking

shotM r. X

blew a holein thefuselage

poisonedher

blew themup

kept thewater fromfloodingthe valley

killedM r. X

downedthe plane

killedher

killedthem

savedthetown

Data segment 1. (From R. Arens 1969: 64)

Yet another example is provided by tfie fifth trial of Willie Lee Stewart on a chargeof murder. Stewart had entered a grocery story about closing time. After ordering asoda and a bag of potato chips which he ate in the store, he pointed a pistol at theproprietor who was standing behind the counter with his wife and daughter. The

women pleaded with Stewart to "take the money" and offered him the register. He,however, "didn't step back, he didn't step forward, he didn't change expression, hejust fired" Only then did he open the register "and emptied it very calmly walked

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

20/21

-

8/13/2019 Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge.

21/21

![download Jayyusi, L. (1993). Premeditation and Happenstance- The Social Construction of Intention, Action and Knowledge. [Article]. Human Studies, 16 (4), 435-454.](https://fdocuments.us/public/t1/desktop/images/details/download-thumbnail.png)